Adeeb Kasem

Cruelty and Culture

A Treatise on Schizoanalysis and Political Anthropology

Introduction: Summary of the Contents of This Book

Part I: The State and Violence

Section 1: What Is a Cultural Construct?

Section 2: A Political Ontology of the State

Section 3: The Ontology of Abstract Labour and Capital

Section 4: Nietzschean Anarchism and Genealogical Materialism

Interlude: 13 Ways of Looking at a Zombie

Part II: An Introduction to Schizoanalysis

Section 1: I, Robot Too; Or, the Desiring-Machines

Section 2: The Zombie Within; Or, the Body Without Organs

Section 3: The String-Theoretical Topology of Affects; Or, the Celibate Machine

Part III: Schizoanalytic Explorations

Section 1: Realist Monism or Monist Realism

Section 2: The Real and Reality

Section 4: A Post-Structuralist Anti-Semiology

Section 5: The General Economy of Raw Desire

This book is dedicated to David Graeber (1961–2020), who showed me that a world without bosses, police, prisons, and armies is possible.

“Without revolutionary theory there can be no revolutionary movement.”

– Lenin,

What Is To Be Done?, “Dogmatism And ‘Freedom of Criticism’” (1902)

“On his standard of proof, natural science would never progress, for without the making of theories I am convinced there would be no observation.”

– Charles Darwin (1888, p. 315)

Introduction: Summary of the Contents of This Book

The curious reader can skip ahead to the main body of the book.

The main thesis of this book is that the State is at its basis nothing but a machine for violence and slavery, and that it uses moralities or moral discourses in order to produce and reproduce its power. This book may be said to be a work of anthropology or sociology as well as metapsychology; and although many will dismiss it as “merely philosophy,” the fact that it is indeed a work of philosophy is neither sufficient grounds nor necessary grounds for dismissing it. That being said, most of the thinkers we engage with are indeed philosophers. People who dismiss works of philosophy on the grounds that it is “merely philosophy” are of no concern to us.

Part I, “The State and Violence,” focuses on the main thesis of the book. Along the way, we make maps of power and discover both technologies of power and technologies of resistance. Part II, “An Introduction to Schizoanalysis,” introduces what we deem to be the three core concepts of schizoanalyis, as developed by Deleuze and Guattari in Anti-Oedipus: desiring-machines, the body without organs, and the celibate machine. Along the way, we add much to the core concepts of schizoanalysis, since the interpretation of a work is always an addition to its object, since it is never the same as the object itself. Part III, “Schizoanalytic Explorations,” extends and revises the theory of schizoanalysis, taking it to new domains of theory. Along the way, we work on pure theory, theory which still awaits the discovery of its possible applications.

Part I, “The State and Violence,” is, in part, a schizoanalysis of power, meaning that it uses concepts which are only defined (and explicated in great detail) in Part II, “An Introduction to Schizoanalysis.” The definitions of schizoanalytic concepts are defined thus in a separate part because defining them in the midst of their application would render their application too cumbersome and digressive. For the same reasons, avoiding the cumbersome and the digressive, Part III, “Schizoanalytic Explorations,” contains bits and pieces of the groundwork for the metaphysics we employ in Part I and Part II. Conceivably, the three parts can be read in any order, according to the inclinations of the reader. We have placed “The State and Violence” as Part I because it is both the most accessible and the most political part. “The State and Violence” has the most immediate import for political activists and theorists. The news will always be bad news as long as there is a hierarchy founded and maintained by physical violence, and consequently the reasons for making a revolution will always be there. Thus, as long as there is a hierarchy founded and maintained by physical violence, “The State and Violence” will remain urgently relavent reading, with Part II and Part III serving as reference material for whatever remains obscure in Part I.

Part I, Section 1, “What Is a Cultural Construct?”, is a critique of Durkheim’s transcendentalist concept of “social facts,” and by this proxy also a critique of structuralism (the school of thought that includes the works of Saussure, Lévi-Strauss, and Lacan), which is based on Durkheim’s concept of “social facts.” We develop the concept of “cultural constructs” as a viable and operational alternative unit of analysis, and as the starting point of a post-structuralist analysis, that is to say, a sociological or anthropological analysis that rejects all forms of transcendentalism.

Part I, Section 2, “A Political Ontology of the State,” is a revision of Nietzsche’s On the Genealogy of Morals that develops Nietzsche’s concept of the State, especially in relation to his concepts of morality, through critical engagements with Graeber’s Debt: The First 5000 Years, Lenin’s The State and Revolution, and Marx’s Capital Vol. 1. Our main thesis is that the State, at bottom, is based on nothing but violence, and that as a social institution the State is nothing other than the social institution of slavery. Among our key findings are a reversal of the orthodox Marxist theory of infrastructure/superstructure, which places political economy at the base or infrastructure and the State at the superstructure; we argue that the real relation is the reverse, such that the State is the base or infrastructure, and political economy is the superstructure. Along the way, we also examine the role played by different types of morality in either its complicity with the State or its opposition to the State. We also rectify Nietzsche’s psychology by relying on Deleuze and Guattari’s schizoanalysis.

Part I, Section 3, “The Ontology of Abstract Labour and Capital,” is both a critique and an affirmation of Marx’s concepts of abstract labour (economic value) and capital, as presented in Capital Vol. 1. We critique a portion of Marx’s theory that is too idealist, namely Marx’s concept of an ideal “value form” objectively existing in the commodity beyond its material physical form. We affirm Marx’s concepts of economic value (abstract labour) and capital based on our materialst theory of cultural constructs and our materialist theory of the State’s primacy in relation to political economy.

Part I, Section 4, “Nietzschean Anarchism and Genealogical Materialism,” develops Nietzsche’s theory of genealogy, with some modifications in the interest of materialism, and also in relation to Walter Benjamin’s “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” which is both a striking affirmation of genealogy by another name, and an elucidation of the political implications of the concept of genealogy for the ultra-left.

Part I, Section 5, “Overhumanism,” cites the anarchist dimension of Nietzsche’s concept of the “overman,” which he explicitly writes of as able to come into being only with the abolition of the State, and also revises the concept of the “overman” in order to both make it more inclusive and develop its anarchist dimension, such that, as the political project of the abolition of the State, it intersects with all other liberation struggles, including women’s liberation, gay liberation, and trans liberation, as well as decolonization. In this regard, we examine further political implications of Nietzsche’s concepts of the active and the reactive, as well as Nietzsche’s critique of slave morality.

Part II, Section 1, “I, Robot Too; Or, the Desiring-Machines,” explicates Deleuze and Guattari’s concepts of desiringprouction and desiring-machines.

Part II, Section 2, “The Zombie Within; Or, the Body Without Organs,” explicates Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of the body without organs.

Part II, Section 3, “The String-Theoretical Topology of Affects; Or, the Celibate Machine,” explicates Deleuze and Guattari’s concepts of the celibate machine and the nomadic subject. In a much later work, What Is Philosophy?, Deleuze and Guattari develop an entirely new concept of affect which we completely ignore in the present work. Deleuze and Guattari themselves found it essential to change their jargon from book to book; following them in spirit rather than to the letter, we have defined “feelings,” “emotions,” and “affects” as meaning the same thing in the present work, but the interested reader who peruses What Is Philosophy? can easily adapt our observations and conclusions, mutatis mutandis, to their new jargon.

Part III, Section 1, “Realist Monism or Monist Realism,” presents what may appear to be our “overarching” ontology, but is in fact one ontology of ours alongside the others, with which it intersects. We modify the broad outlines of Spinoza’s ontology; we define substance as plasticity, thereby affirming an ontology of radical contingency, and understand forms as forces. We also briefly discuss the political implications of our ontology of plastic substance.

Part III, Section 2, “The Real and Reality,” is a critique of Lacan’s concept of the Real, by way of Zizek’s presentation of it in Looking Awry.

Part III, Section 3, “Cruelty and Memory,” presents our concept of cruelty in relation to memory, by way of Deleuze and Guattari’s concepts of the body without organs and intensity. The text we focus the most on here is Deleuze and Guattari’s essay, “How Do You Make Yourself a Body without Organs?” We affirm that intensity or cruelty makes a sense-impression more memorable, and we critique Freud’s concept of “repression,” which states the opposite.

Part III, Section 4, “A Post-Structuralist Anti-Semiology,” explicates Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of the rhizome in new ontological terms, and develops schizoanalysis as a mode of interpretation.

Part III, Section 5, “The General Economy of Raw Desire,” develops our concept of raw desire, desire without an object, in terms of Bataille’s concept of general economy, that is, the economy of excess.

Part III, Section 6, “The Critique of Mythology,” develops our concepts of Truth, myth, and mythology. In this section, we present our ontology of particulars and universals. Moreover, we appropriate Husserl’s phenomenology in order to develop a new semiology, that is, a new theory of the sign, one that is machinic as opposed to transcendental. We relate our conclusions to Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of “group fantasy,” which we rename “group mythology,” as well as to the Nietzschean project of the transvaluation of all values. We develop new technologies of interpretation that complement those of Deleuze and Guattari, and those we have developed following Deleuze and Guattari. Deleuze and Guattari also employ a different concept of “concept” in What Is Philosophy? than the one we use here; we define concepts as abstract generalities, but for the later Deleuze and Guattari it means something else entirely.

To readers of our previous works and prospective readers of our previous works, we wish to say here that this present work is a radical rupture with our past works. Although at times we draw upon our previous study of Nietzsche, The Science of Self-Actualization, and our previous study of Freud, The Science of Love, the interpretations (and revisions) of Nietzsche and the refutations of Freud we present here are mostly new, both in relation to our own work and the works of others. Moreover, we mostly reject our earlier work Matter Over Mind, which recycles the stale combination of orthodox Marxism and Freud, and presents groundless criticisms of post-structuralism. Here, we affirm post-structuralism, we affirm Nietzsche, we affirm a heterodox Marxism, and we reject Freud, the crucial difference being that we also affirm anarchism (a Nietzschean anarchism, which could equally well be described as a Marxist anarchism). The justifications for our break with the past are explicitly stated in our critiques, albeit without reference to our previous works.

Prelude: Destroy the Centre

The centre cannot hold for long,

The centre will not hold for much longer,

The centre will not hold.

Things don’t fall apart fast enough,

The centre holds too fast,

And the centrists hold too fast to the centre.

To hell the centre and to hell with the centrists.

Let us destroy the centre and destroy the centrists,

Let us loose glorious anarchy upon the world.

The centre looses the lukewarm tide of global warming upon the world

And drowns the politics of sincerity.

The best are full of passionate intensity,

While the worst lack all conviction.

Turning and turning in the widening maelstrom, The ship is sinking.

The falcon is going extinct because of man-made global warming,

And the falconer is worried about losing his job,

But there will be no more jobs when the human race is extinct.

We’re still waiting on the First Coming.

The Revolution is the Messiah.

Death to Babylon! Burn Babylon to the ground!

We have to make the Revolution ourselves, with whatever is at hand.

My sight is troubled by the desert of reality

And its sands of indifference,

In which I encounter the broken statue of Ozymandias

And the rotting ruins of the life-size map of reality,

Like putrid shit spilled from rotting guts.

My gaze is pierced by the world and I am dying of too much pity,

My pity overflows like the light of the sun.

I no longer want to be without pity,

For I have the courage now

To face up to the immense pain and terrible truth of pity.

My heart is a fountain of blood.

The sun of pity blinds me with pain.

The ruling class circle in the sky like vultures,

Waiting to feast on the corpses of the subjugated.

And the triumphant monsters have built a new

Cave for us, Where we sit hypnotized by their shadows.

We’re in the midst of our second century of stony sleep now,

Vexed to nightmare by the invisible hand of God rocking the cradle.

When our hour comes,

We will bite the invisible hand of God and make it bleed!

We will become rough beasts.

We will liberate ourselves,

We will liberate Bethlehem,

We will liberate the world!

Part I: The State and Violence

Section 1: What Is a Cultural Construct?

Durkheim defines social facts as “ways of acting, thinking and feeling which possess the remarkable property of existing outside the consciousness of the individual” (1895/1982, p. 51). Thus social facts would be universals that exist outside of, that is, separate from, particulars. However, we maintain that social facts as Durkheim defines them do not exist. In other words, there are no ways of acting, thinking, and feeling which exist outside of the mind of an individual or the individuals constituting a group. Durkheim speaks of “consciousness,” as if the mind did not also have an unconscious portion; in order to include the unconscious in our discussions, we shall simply read “mind,” meaning the mind whether conscious or unconscious, whenever Durkheim misleadingly says merely “consciousness.” Furthermore, all ways of acting, thinking, and feeling are simultaneously individual and social, that is, individuality and sociality are always their two degrees of freedom; all ways of acting, thinking, and feeling are social, even if they belong to a society that does not yet exist, because they are all products of the process of cultural construction, which is really another way of describing motivation-construction. Therefore, we may call practices, intentions, thoughts, and affects “cultural constructs” in order to distinguish them from Durkheim’s erroneous concept of “social facts.” The ontology of cultural constructs exemplifies Hegel’s dictum that “the universal exists only in the particular, and the particular is itself a universal unto itself.” Ways of acting, thinking, and feeling exist only through the mind of the individual; they are, however, nonetheless always in a relationship with the world outside of the individual mind. Cultural constructs are ways of acting, thinking, and feeling, which always possess the readily observable property of existing only through individual minds.

Durkheim writes, “The system of signs that I employ to express my thoughts, the monetary system I use to pay my debts, the credit instruments I utilise in my commercial relationships, the practices I follow in my profession, etc., all function independently of the use I make of them” (1895/1982, p. 51). These may indeed all exist and function outside of my own individual mind, such as before my birth and after my death, but only because they also exist and function through the individual minds of other individuals who are not me, namely all those other individual minds that existed before my birth and all those other individual minds that will exist after my death. Moreover, unit-systems such as monetary unit-systems (for instance, those used in capitalism), credit instruments (for instance, those used in capitalism), and professioinal practices (for instance, those of the police officer, those of the corrections officer, and those of the banker) may be abolished in the event of a revolution, and they can be abolished precisely because they were nothing but cultural constructs to begin with. Each member of society can in turn repeat the above statement by Durkheim and in each case it would be relatively true for themselves as individuals, but if we consider all of the members of society as individuals constituting that society, and thus no longer consider them singly and in turn as mere individuals, but consider them instead as individuals constituting a social unitstructure or social machine, then it becomes indubitably evident that the unit-system of signs employed to express thoughts, the monetary unit-system used to pay debts, the credit instruments utilised in commercial relationships, the practices followed in various professions, etc., all function in complete dependence upon the multiplicity of given individual minds that together form the group that we call society. Ways of acting, thinking, and feeling may exist outside the mind of a single given individual, but only because they exist through the minds of many individuals who together constitute a group.

Durkheim writes that a “social fact” “is a product of shared existence, of actions and reactions called into play between the consciousnesses of individuals,” that it is a “special energy derived from its collective origins” (1895/1982, p. 56). From this passage, the non-material, ideal, and metaphysical nature of “social facts” is immediately apparent and transparent. A “social fact” is a “social product” in the sense that it is the product of a “collective origin,” that is to say, “of shared existence,” but this product is specifically a “special energy” which does not exist within individuals, but externally to them in a non-material, ideal space which exists only “between the minds of individuals” while simultaneously excluding those individual minds. Such a concept of a “special energy” is clearly not meant literally as a physical energy capable of being studied by physics, but is a metaphor drawn from physics, whether consciously or unconsciously, and such a metaphor is familiar to anyone even passingly familiar with the obscurantist metaphysics of popular “spirituality,” and indeed Durkheim’s idea of social facts is completely compatible with such obscurantist metaphysics, and it is probable that opportunistic mystics literate enough to read Durkheim would find Durkheim’s idea of “social facts” to be “scientific” support for their mystifying obscurantism. In any case, it is clear that not only is this “special energy” non-existent from the positivist perspective of the natural sciences, but more importantly it is completely non-existent from the existential perspective of the actual lived experience of being human. We do not reject the idea of “social facts” for merely being metaphysical (since materialism is after all a metaphysics), but rather, we reject it for being an idealist concept, that is, non-existent – for being an irrational, unobservable, and obscurantist idea that does not describe anything that actually exists. There is neither a necessary reason nor a sufficient reason for the existence of “social facts.” It is entirely possible to explain culture and society without ever resorting to Durkheim’s concept of “social facts.” The burden of proof lies upon the Durkheimian sociologists (and, by implication, the structuralists), since it is the hypothesis of “social facts” which apparently transcends our lived experience (and is therefore the more fantastic claim), whereas the hypothesis of cultural constructs is amply proved by our lived experience (and is therefore the more readily observable claim).

Durkheim makes no mention of it, but his concept of “social facts” is roughly equivalent to Hegel’s idea of “objective spirit,” or obversely, the concept of “objective spirit” that Hegel develops (in The Phenomenology of Spirit) ends up being a description of an ideal entity that functions roughly in the same manner as what Durkheim describes as a “social fact.” We note the similarity of the Durkheimian “social fact” and the Hegelian “objective spirit” because both refer to the same hypothetical ideal entity that shares the same essential property of being autonomous “ways of thinking, feeling, and acting” that exist wholly independently of all individual minds, which is why we describe “social facts” as “ideal spirits.” Obversely, Zizek correctly identifies Hegel’s concept of “objective spirit” as “the universal symbolic system as a non-psychological “objective social fact”” existing independently of and opposed “to individual subjects and their interaction” (in the Hegelian jargon, individual minds or individual subjects are “subjective spirits”) (2012, p. 98). But we deny that “universal” symbolic unit-systems are non-psychological “objective social facts.” We identify “universal” symbolic unit-systems, what elsewhere Zizek and other Lacanians also describe as “the symbolic order,” as imaginarysymbolic unit-systems or imaginary-symbolic orders which are wholly psychological or metapsychological subjective cultural constructs, and moreover, we identify them as texts fabricated upon the surface of what Deleuze and Guattari describe as “bodies without organs” (such than a given imaginary-symbolic order is in reality a text recorded upon the surface of a body without organs). A text recorded on the surface of a body without organs is precisely a wholly psychological or metapsychological subjective cultural construct that functions as a “universal” imaginary-symbolic order.

Zizek writes that Hegel’s concept of “absolute spirit” refers to neither a “simple reduction of OS [objective spirit] to subjective spirit (SS),” nor an “even more In-itself absolute entity that encompasses both SS [subjective spirit] and OS [objective spirit]” (2012, p. 98), but rather, Hegel’s concept of “absolute spirit” refers to “the gap that separates OS [objective spirit] from SS [subjective spirit] within SS [subjective spirit],” which makes it “so that OS [objective spirit] has to appear (be experienced) as such, as an objective “reified” entity, by SS [subjective spirit] itself (and in the inverted recognition that, without the subjective reference to an Initself of the OS [objective spirit], subjectivity itself disintegrates, collapses into psychotic autism)” (2012, p. 99). However, because in reality there is no such “objective spirit,” it necessarily follows that there is no gap between a “subjective spirit” and the “objective spirit,” since the “objective spirit” does not exist to begin with. In other words, there is no “absolute spirit.” The “objectivity” of the socalled “objective spirit” is nothing but an illusion. Or, to phrase it another way, the apparent “objectivity” of the “social fact” is nothing but an illusion. The “objective spirit” of laws and customs is in reality nothing but the purely subjective phenomenon of cultural constructs, and the only possible “gap” between an individual mind and the cultural constructs existing within it is the gap of understanding which makes cultural constructs appear as reified nonpsychological “objective” social facts, and this gap of understanding can also be described as a form of alienation, or more precisely selfalienation or self-estrangement, for this gap of understanding is a lack of understanding of a part of one’s self just as much as it is a lack of understanding of the essence of society and a lack of understanding of the essence of laws and customs. The part of one’s self in question which is alienated in this form of alienation is one’s own faculty of freedom, that is to say, the full extent of one’s own freedom, the part of one’s self that has the capacity to be free, since the cultural constructs which appear as “objective” social facts, insofar as they do appear “objective” to the subject, suppress one’s own faculty of freedom insofar as they suppress one’s ability to resist the internalized coercion of laws and customs (as well as one’s ability to resist the external coercion of laws and customs through their representatives and intermediaries, viz. parents, teachers, police, military, even one’s own siblings or peers, etc.), that is to say, insofar as they suppress one’s ability to disobey laws and customs in order to follow the dictates of one’s own free will (one’s will independent of laws and customs; that is to say, one’s will independent of all duties or categorical imperatives). One only ever obeys a duty out of an unfree will, out of the coercion exerted by that duty, whether that coercion is consciously felt or whether it is an unconscious instinct.

Therefore, “without the subjective reference to an “In-itself” of the objective spirit,” subjectivity does indeed disintegrate and collapse into “psychotic autism,” but this “psychotic autism” is nothing but the discovery of one’s own freedom, that is to say, it is the negation of self-alienation, it is self-reconciliation and selfactualization. Without the subjective reference to an “In-itself” of the “objective spirit,” subjectivity reconciles itself with its own freedom and ceases to be an alienated and unfree subject. It is evident that by describing the subjectivity of freedom, subjectivity “without the subjective reference to an “In-itself” of the objective spirit,” as “psychotic autism,” Zizek – following Lacan, who is himself following Freud, who is himself following other bourgeois thinkers – pathologizes and criminalizes, excludes as diseased, insane, and criminal, the truly free subject. We agree with Deleuze and Guattari’s critiques of psychoanalysis in their book Anti-Oedipus, especially, for instance, when they criticize psychonalysis for reducing practically everything to “the Father” and then upholding as “good” the internalized authority of this “Father,” which in Lacanese is “the Other” (the “Other” with a capital “O”) or “the big Other,” which, according to Lacan and Zizek, is the spectre or phantasm that upholds “the universal symbolic system as a nonpsychological “objective” social fact,” and which, according to Zizek’s study of Hegel, can be described in Hegelese as the “absolute spirit” (but which, as we have demonstrated, is in reality nothing more than the alienation of the subject from its own freedom, that is to say, it is nothing more than the internalized suppression of the subject’s own freedom within the subject itself); and we wholeheartedly agree when Deleuze and Guattari affirm as the true good the so-called “psychotic autism” or “schizophrenia” that results for the self once it emancipates itself from the simultaneously psychological and social tyranny of the so-called “big Other,” since both the so-called “big Other” and the so-called “objective social facts” it upholds are in reality nothing but cultural constructs, and since the subject can only be restored to its own capacity for freedom once it recognizes the so-called “big Other” and the so-called “objective social facts” as nothing but mere cultural constructs. Indeed, within the terminology of psychoanalysis, the subject’s real freedom cannot be described as anything other than “psychotic autism,” “psychosis,” “dementia praecox,” or “schizophrenia.” (The eliminative materialism of cognitive-behavioural, neurological, and pharmacological psychiatry is even worse, since it denies the existence of the mind altogether, and since it makes anyone who disagrees with it in the slightest out to be suffering from one “mental illness” or another, for which there is no cure, but conveniently enough for the pharmaceutical companies and the big capitalists who ultimately own them, only a life-long treatment which requires the patient to purchase pills from those aforementioned pharmaceutical companies for the rest of their life).

Durkheim himself unwittingly and unknowingly refutes his own idea of social facts when he attempts to furnish examples of them, apparently oblivious to both the implications of his own words and the actual functioning in the real world of the institutions and other things he describes. For instance, Durkheim writes, “When I perform my duties as a brother, a husband, or a citizen and carry out the commitments I have entered into, I fulfil obligations which are defined in law and custom and which are external to myself and my actions. Even when they conform to my own sentiments and when I feel their reality within me, that reality does not cease to be objective, for it is not I who have prescribed these duties; I have received them through education” (1895/1982, p. 50). Although it may not be “I who have prescribed these duties,” nevertheless “I have received them through education.” In other words, these duties must be put into my own individual mind, presumably by other individual minds, before I can obey them, which means that they have no existence except inside individual minds. Cultural constructs are objectively subjective, including when they are intersubjective. Moreover, it may not be “I who have prescribed these duties,” but it is self-evident that some individual or group of individuals has, at some point in the past, prescribed these duties, meaning that laws and customs are neither products of nature nor of a divinity, but are human-made creations and are necessarily the fabrication of either a single individual or a group of individuals. Therefore, neither in their origin nor in their operation do laws and customs exist totally outside individual minds, but in their origin and their operation laws and customs only exist inside individual minds. It is the very existence of laws and customs inside individual minds that is objective: the objective truth of laws and customs is that they only exist in and through the subjectivities of individuals.

If every human being on Earth were simultaneously struck with amnesia, all existing laws and customs would cease to exist. Having no memory of any prior law or custom, no one would follow them, since they would be entirely ignorant that any such law or custom had ever existed, nor would they suffer any coercion to follow them, since all prior agents of coercion would likewise have no memory of any prior law or custom let alone that it was their job to enforce them. It makes no difference that some prior laws and customs were written down, for they would need to be re-discovered for anyone to know that they once existed at all, and having absolutely no memory, it is doubtful whether anyone would choose to follow them once again; in other words, if they were rediscovered, these documents of prior laws and customs would be come to known first and foremost as historical cultural artefacts, assuming that they would not simply be objects of pure speculation, and in any case they would not exist as laws and customs in the post-amnesia present. It is clear then that the existence of laws and customs as existing, functioning laws and customs is wholly dependent on individual minds.

Durkheim describes in greater detail the process of education, and our conclusions above on the incompatibility of the real process of education and the existence of “social facts” are completely re-affirmed by Durkheim’s more detailed description of the process of education. Therefore, the following paragraph is worth quoting in full:

“It is sufficient to observe how children are brought up. If one views the facts as they are and indeed as they have always been, it is patently obvious that all education consists of a continual effort to impose upon the child ways of seeing, thinking and acting which he himself would not have arrived at spontaneously. From his earliest years we oblige him to eat, drink and sleep at regular hours, and to observe cleanliness, calm and obedience; later we force him to learn how to be mindful of others, to respect customs and conventions, and to work, etc. If this constraint in time ceases to be felt it is because it gradually gives rise to habits, to inner tendencies which render it superfluous; but they supplant the constraint only because they are derived from it. It is true that, in Spencer’s view, a rational education should shun such means and allow the child complete freedom to do what he will. Yet as this educational theory has never been put into practice among any known people, it can only be the personal expression of a desideratum and not a fact which can be established in contradiction to the other facts given above. What renders these latter facts particularly illuminating is that education sets out precisely with the object of creating a social being. Thus there can be seen, as in an abbreviated form, how the social being has been fashioned historically. The pressure to which the child is subjected unremittingly is the same pressure of the social environment which seeks to shape him in its own image, and in which parents and teachers are only the representatives and intermediaries.” (1895/1982, pp. 53–54)

That parents and teachers are representatives and intermediaries of the “social environment” means precisely that the “social environment,” that is to say, laws and customs, can only exist in and through individual minds, and has no existence apart from them. The idea of “a rational education” in which the child is allowed “complete freedom to do what he will” is irrelevant to Durkheim’s idea of “social facts.” In either case, the child would internalize laws and customs through their representatives and intermediaries, parents and teachers. What is in question is not the best style of education for the internalization of laws and customs, but whether laws and customs have any existence independent of individual minds. We agree with Durkheim that “education sets out precisely with the object of creating a social being” and that a “social being” is a human being who has internalized the laws and customs of their society by means of education. By this definition, for example, feral children, children abandoned in the wilderness at an early age who have grown up without contact with other human beings, that is to say “children raised by wolves” as the popular idiom goes, such as Victor of Aveyron, are not “social beings” (at least in the technical sense we have delineated), although they may become “social beings” via education once they have made contact with members of a given society. Furthermore, cases such as those of Victor of Aveyron lend support to our argument for the nonexistence of “social facts,” since they demonstrate that a human being completely isolated from other human beings from infancy feels absolutely no pressure to obey any laws or customs of any human society whatsoever, since they are completely ignorant of absolutely all human societies, as evinced by the fact that when such feral children are initially discovered they behave without any regard for established laws and customs, guided instead only by their primitive instincts, their natural faculty of empathy for others, and the behaviours they learned from non-human animals in the wilderness. We agree with Durkheim that education is the means by which laws and customs are internalized, and that the result of this internalization is that culturally relative laws and customs are thought and felt by the socialized being to be “objective social facts” with a wholly objective existence, but we deny that laws and customs have any real objective existence, that is to say, we maintain that laws and customs remain culturally relative ideas which exist only in the minds of individuals even when those individuals have been so thoroughly culturally indoctrinated that they believe and feel on an instinctual, intuitive level that the laws and customs of their society are objective.

In order to explain the mechanism of cultural indoctrination, socialization, or education, we cannot rely on Durkheim, since the factor of desire or motivation is wholly absent in Durkheim’s analysis. If we wish to account for the factor of desire, then we cannot resort to explanations that rely on the concept of habit. One may indeed obey laws and customs out of habit, in which case one does not feel coerced to obey them. However, the cases in which the feeling of coercion does occur cannot be accounted for by the concept of habit. Moreover, we are concerned with a very specific type of cultural indoctrination (or socialization, or education), one in which externally imposed constraints become internalized as internally imposed constraints, constraints imposed by the “moral conscience” of an individual mind. First of all, let us note that this “moral conscience” is in fact merely a “bad conscience,” since it feels itself to be “bad,” or what amounts to the same thing, it feels itself to be coerced, and it only obeys the given laws and customs on that basis. This bad conscience or feeling of coercion is a zone of intensity upon a specific type of body without organs, a virtual body of slavery, which has inscribed upon its surface the imaginarysymbolic order or unit-system of laws and customs which is associated with its zones of intensity (including the bad conscience), and which the productive subject thereby feels its inclined to obey. An authority figure (for example, a parent), forges a virtual body of slavery for the child through a unit-system of cruelty, that is, a unitsystem of intensity, a process which is accompanied by the moral discourse that becomes internalized as an imaginary-symbolic order that is felt to be “objective” and “transcendental.” Thus, what starts out as a fear of punishment by authority figures external to one’s own individual mind becomes internalized as a fear of becoming immoral (the fear of becoming a criminal in one’s own essence, i.e. the fear of becoming a “sinner”), which nonetheless still bears the traces of the fear of punishment by external authority figures insofar as the fear of becoming a sinner is always accompanied by the idea of being punished by an objective moral-spiritual order (for example, “karma,” “God,” “cosmic energy,” or “Hell”). We shall later revise this model and describe it in greater detail, but for our present purposes this gloss suffices. In any case, the truth of this process of moral education is that it is totally arbitrary and culturally relative, meaning that it is wholly dependent upon the society which one happens to be thrown into by one’s birth, and also upon the parents and teachers who happen to instill one with a fear of external punishments (and its necessary correlate, a desire for external rewards, which is likewise internalized to the point of becoming instinct). Because the process of moral education is always completely arbitrary and culturally relative, any unit-system of morals is itself a completely arbitrary, culturally relative, and wholly subjective unit-system of ideas. There are no laws and customs that we necessarily have to obey because there are no laws and customs which have any objective existence or truth whatsoever. All laws and customs are wholly arbitrary, culturally relative, and subjective.

Therefore, we must revise our concept of the cultural construct, or at least we must revise what exactly we mean by “cultural construction” when we say that cultural constructs are established and operate by way of a mutual cultural construction among the individual members of a given group. The phrase “cultural construction” might suggest to some the image of an art project freely undertaken by a group by uncoerced mutual agreement. However, the real process of cultural construction, as we use the term, is a material process, and examples of it include all those processes of violence and coercion, for example all those processes of violence and coercion essential to the machinic functioning of the State. We accept the Marxist-Leninist definition of the State, that the State is merely an instrument for the oppression of one class by another, but we deny that the State can ever really benefit the proletariat, because the State invariably always oppresses the proletariat, coerces the proletariat to obey it by means of violence or the threat of violence, and this violent coercion of the proletariat by the State is essential to the machinic functioning of the State. That is to say, the State is by definition a machine for the violent oppression and coercion of the subjugated class by the ruling class, and the proletariat is always by definition the subjugated class (for example, as opposed to the ruling class of party bureaucrats in the socialist state, or, roughly speaking, as opposed to the ruling class of capitalists in the capitalist state). We shall examine the MarxistLeninist theory of the State in closer detail later on.

In his essay The Social Contract, Rousseau writes, “If one is compelled to obey by force, there is no need to obey from duty; and if one is no longer forced to obey, obligation is at an end” (2002, p. 158). Rousseau argues in The Social Contract that might does not constitute right, that is to say, violence is not justice, power is not justice. If violence founds and maintains laws and customs, then obedience to laws and customs is ultimately motivated by nothing other than fear of punishment, fear of pain or death. We maintain, along with Rousseau that “pity is the foundation of virtue,” that pity is basis for justice, albeit we add the caveat that that pity must have its basis in truth, that is, in reality. It is on this basis that we agree with Rousseau that laws and customs founded and maintained by violence are fundamentally unjust and illegitimate. But we differ from Rousseau in that we deny that a State can ever be legitimate or just, since a State as such is merely a machine of violence, meaning that the State is fundamentally illegitimate and unjust. In other words, the State is never founded upon a social contract, since a true social contract, a social contract that is freely agreed to, can never be founded on violence.

Durkheim writes that “Undoubtedly when I conform to them [laws and customs] of my own free will, this coercion is not felt or felt hardly at all, since it is unnecessary,” but “If purely moral rules are at stake, the public conscience restricts any act which infringes them by the surveillance it exercises over the conduct of citizens and by the special punishments it has at its disposal” (1895/1982, p. 51). In other words, when in the real world individuals are either ignorant of a given law or custom or they deliberately defy a given law or custom, the State punishes them in one way or another, and in any case the threat of punishment for failing to obey laws and customs was there in the State from the beginning, such that obedience to laws and customs was coerced from the very beginning. Only those who desire their own repression obey laws and customs out of their “own free will,” and metapsychology denies that this will is truly free, since it is both alienated from its own true freedom (the ability to disobey) and since it is at bottom nothing but the instinctualized fear of punishment. However, the surveillance and special punishments of the “public conscience,” which means here nothing but the State apparatus, presumably depends upon the individual minds who are its agents or constituents, for instance the police and the military, meaning that the “public conscience” is itself made up of individual minds. If absolutely all members of a given society suddenly believed that all their prior laws and customs are unjust and that therefore they should no longer obey them, then those prior laws and customs cease to exist as laws and customs for them; such would be a bloodless revolution. Of course, in reality, revolutionaries have to fight against the counterrevolutionary constituents of the State who still believe in and thus enforce the laws and customs of the State. On the other hand, if I think that the laws and customs of a given society are unjust but I nonetheless obey them because I am coerced to obey them by the threat of violence, I have those laws and customs in mind at least insofar as I am coerced to obey them, regardless of the fact that I judge them to be unjust; moreover, in the case of coercion, there are at least two groups (or perhaps in certain cases they form one and the same group), that both has these laws and customs in their minds and judges them to be just, however cynically they may define justice (for example, they might believe that justice is constituted solely by violence), namely the group (or perhaps the single individual) that invents the laws and customs and the group that coerces others into obeying these laws and customs. Disobeying laws and customs out of ignorance of their existence for others merely demonstrates that in the unconsciously disobedient individual’s mind the given laws and customs do not exist as laws and customs. Disobeying laws and customs deliberately demonstrates that for the consciously disobedient individual’s mind the given laws and customs also do not exist as laws and customs, but because the consciously disobedient individual has judged the given laws and customs to be illegitimate in one sense or another. In any case, laws and customs never exist completely independent of individual minds, but they objectively only exist inside individual minds, whether they are obeyed out of rational belief in their justice, or obeyed out of a desire for one’s own repression, or obeyed out of coercion, or disobeyed.

Durkheim writes, “Even when in fact I can struggle free from these rules and successfully break them, it is never without being forced to fight against them” (1895/1982, p. 51). However, whenever I attempt to break free from the rules, it is never the rules in themselves that I am forced to fight, which would be absurd, since in reality the rules are no more than thoughts in the minds of others, despite Durkheim’s assertions to the contrary that they have some sort of ideal objective existence apart from all minds. Whenever I attempt to break free from the rules, it is always the enforcers of the rules that I am forced to fight against, that is to say, I am forced to fight against other human beings endued with mind who believe, sincerely or cynically, but always wrongly, that the rules are just (though they are ultimately based on violence and nothing but violence) and that it is justified to enforce them with violence. Durkheim writes, “Even if in the end they [the rules] are overcome, they make their constraining power sufficiently felt in the resistance that they afford” (1895/1982, pp. 51–52). However, assuming that the rules have been overcome by way of overthrowing the authorities that enforce them, then the only ways that the rules can continue to exert a contraining power on the victorious rebel is either by way of the old enforcers of the rules who continue to exist as an underground counter-revolutionary group, or by way of the ostensibly troubled psyche of the victorious rebel, within which in this latter case one part of her mind continues to believe in the justice of the rules that the other part of her mind believes is unjust; in either case, the rules continue to exist only within the mind(s) of either a group of individuals or a single individual, never completely independently of all minds.

Durkheim reserves the term “social” to describe ostensible phenomena of the kind he calls “social facts,” namely ways of thinking, feeling, and acting that exist independently of all individuals. However, as we have demonstrated, the kind of “social facts” Durkheim describes simply do not exist, meaning that there is nothing “social” in the sense that Durkheim means it. To reiterate, we have used the term “cultural constructs” to designate those ways of thinking, feeling, and acting that exist wholly dependently upon minds, whether of a single individual or a group of individuals. We can reject the term “social facts,” since it is a piece of jargon, especially in the interest of more accurate jargon, namely the term “cultural constructs.” The term “social,” however, is in common usage and is to an extent unavoidable when dealing with groups, therefore it must be redefined rather rejected in toto. According to our findings, the term “social” should basically be used strictly to refer to whatever is dependent upon the mind, such that the “psychological” or “metapsychological” and the “social” are really the same. In other words, each society has a set of individual minds as its substratum. To use Durkheim’s phraseology, whether one means by “society” “either political society in its entirety or one of the partial groups that it includes – religious denominations, political and literary schools, occupational corporations, etc.” (1895/1982, p. 52), in each case the society in question is constituted ultimately by a set of individual minds who are in mutual cultural construction with each other, whether formally or informally, consciously or unconsciously, freely or coercively, and thereby form a group of individuals with no ideal spirit extraneous to its constituent individuals. Bearing in mind our new concept of the social, which is opposed to Durkheim’s concept of the social, we can also describe cultural constructs as “social constructs.”

We are not objecting to any description of constraint, we are objecting to the idea that a group is defined by some ideal spirit extraneous to its constituent individuals; when there is constraint in a society, it is enforced either by certain individuals in that group upon other individuals in that group, or it is enforced by the “conscience” of a given individual’s psyche, whether rightly or wrongly (but we must add that the conscience that affirms participation in the State is always wrong). Cultural constructs consist of either practices and intentions, memories, strategies, predictions, or affects, that is to say, cultural constructs are psychical phenomena that have no existence save in and through the set of individual minds that constitute the group to which they belong. We include practices as psychical phenomena since the practices of human beings are inseperable from their psychological components, namely the thoughts and feelings which make them possible. However, it is evident from our above analyses, especially from our analysis of Durkheim’s theory of moral education, that the given unit-system of constraints that comprise the laws and customs of the State are inherently coercive (in other words, coercion is the essential moment of the laws and customs of the State) because they are ultimately based on and maintained by coercion through violent means, that is to say, they are ultimately based on an external unit-system of concrete punishments, and as our analyses suggest, the effective existence of the laws and customs of the State, that is to say, the existence of the laws and customs of the State in effect through the actions of individuals that comprise the constituents of the State, wholly depends upon the continuation of an external system of concrete violent punshiments maintained and executed by individuals (in and through whom this system of violent punishments exists; we mean specifically all those individuals that maintain and operate the criminal justice system and the military, including but not limited to the police, judges, lawyers, law-makers, prison-guards, corrections officers, wardens, soldiers, officers, generals, mercenaries, and the veritable army of accountants and bureaucrats that these institutions require). Because all the laws and customs of the State are wholly arbitrary and culturally relative, lacking in any purely objective existence whatsoever, founded ultimately upon violence and not upon any rationally grounded morality or freely chosen social contract, all the laws and customs of the State are fundamentally and inherently illegitimate, meaning that all states are fundamentally and inherently illegitimate.

Durkheim cites the emotions of a crowd, as in a public gathering, as examples of his “social facts,” and he calls such phenomena “social currents” (1895/1982, pp. 52–53). However, there is no need to posit a ideal spirit extraneous to the individuals in a crowd in order to explain the emotions of the crowd. Durkheim’s choice of terminology, “social currents,” perhaps the metaphor of electric currents, was no doubt the idiom of his time and place for crowd emotions. But even using the analogy of electrical currents, the precise analogy would be of emotions jumping from individual to individual just like electricity, meaning that there is no need to introduce here a reservoir of emotional currents extraneous to the individual bodies in which they circulate. The idiom of my time and place would be that the “energy” of the crowd is “infectious” or “contagious,” which is similar enough to the idea of emotional “currents” circulating in the crowd. Even if we extend the metaphor and describe a crowd emotion as a virus, we must note that a virus is a parasitic psuedo-organism which depends wholly upon its host body for its existence, but we need not play the game of establishing resemblances when we can simply describe things as they are. It is easy enough to understand the mechanism whereby one person can feel the exact same emotion as that experienced by another person, this mechanism is often called “empathy” or “sympathy” and it is a common enough occurrence at the very least in our face to face interactions with others, if not for strangers whom we never see. It is by means of our natural empathy for others in our close proximity, then, that emotions can circulate in a crowd as if it were an electrical current or a contagious virus. In any case, the emotions of a crowd can simply be called crowd emotions, or just as simply, perhaps group emotions, group feelings, or group sentiments, or crowd feelings, or crowd sentiments. The point being that crowd sentiments are cultural constructs, not social facts. In a crowd, great waves of emotion may indeed “come to each one of us from outside and can sweep us along in spite of ourselves,” as Durkheim writes (1895/1982, p. 53), but what Durkheim fails to recognize is that in such a case these great waves of emotion come to us from other individuals outside ourselves, not any extraneous ideal spirit.

Durkheim argues that crowd sentiments are inherently coercive upon every individual in the crowd and that all individuals in the crowd either succumb to this coercion and thus feel the crowd emotion in themselves or at the very least feel the alleged pressure of the coercive crowd sentiment, the more so the more they rebel against it (1895/1982, p. 53). However, when Durkheim introduces the notion of coercion into that of crowd emotions, he is no longer talking about currents generated by empathy; there are indeed coercive crowd emotions, but these coercive crowd emotions depend entirely upon an instinctualized desire for one’s own repression; that is to say, a coercive crowd emotion is ultimately based in the coercion of the State. As the common idiom goes, it is indeed possible for an individual to be “alone in a crowd.” That is to say, it possible for a given individual to be located physically in a crowd but spontaneously not feel the emotions the rest of the crowd feels, without feeling even the slightest pull from a crowd sentiment. The feeling of being “alone in a crowd,” if the popularity of the idiom is any indication, is rather common, perhaps more so for certain individuals as opposed to others, but in any case it is probable that if not everyone, then almost everyone, has felt or will feel “alone in a crowd” at some point in their life. The importance of the “alone in a crowd” phenomenon for our inquiry is that it reveals that belonging to a crowd requires more than mere physical proximity to the crowd. Belonging to a crowd requires a psychological proximity. A crowd, as in a public gathering, is a group, and like any other group the members of a crowd form a crowd as such via a mutual cultural construction (which exists wholly in the individual minds of group members), whether formal or informal, conscious or unconscious. Moreover, membership in a crowd, like membership in any other group, depends upon other cultural constructs, that is to say, upon ways of thinking, feelings, and acting particular to the group, as prerequisites, which constitute the bond between group members (and which exist wholly in the individual minds of group members); it is on the basis of these prerequisite ways of thinking, feeling, and acting that a crowd may spontaneously think, feel, or act in the same way in response to a given stimulus. To be sure, group emotions are real in that they are really felt as emotions, but they are nonetheless constructed, for even reality itself must be always be constructed in order to exist. The lone individual who is “alone in a crowd” may have physical proximity to a given crowd, but they lack the prerequisite cultural constructs necessary to be a true member of the crowd, hence why they do no react to stimuli in the same manner as the members of the crowd. Moreover, insofar as group emotions are dependent upon the prerequisite laws and customs of the State, they are founded upon violence, that is to say, they are at bottom the fear of punishment.

We agree with Durkheim that “certain currents of opinion, whose intensity varies according to the time and country in which they occur, impel us, for example, towards marriage or suicide, towards higher or lower birth-rates, etc” (1895/1982, p. 55), but such an observation is by no means limited to Durkheim, and we find similar statements made by practically everyone who has had contact with cultures other than their own, however accurate or inaccurate the particulars of their observations may be. Plato’s Republic, for example, has as its primary concern the effects that opinions have on the functioning of a society, with the aim of establishing a perfect society in which only the correct opinions, meaning more precisely only truths as opposed to mere opinions, and myths serving a beneficent social purpose, circulate. The truth of Plato’s observations and conclusions are open to doubt, but the fact that he recognized that “certain currents of opinion” cause us to behave in certain ways is amply evident. Moreover, such “currents of opinion” are plainly cultural constructs, not social facts. Currents of opinion do not exist in or as an ideal spirit extraneous to the individuals composing a group. Currents of opinon only exist in the minds of the individuals composing a group.

We disagree with Durkheim in that we maintain that statistics does not afford us a means of isolating these currents of opinion. Currents of opinion are not accurately represented by, for example, rates of birth, death, and suicide. Durkheim writes, “Since each one of these statistics includes without distinction all individual cases, the individual circumstances which may have played some part in producing the phenomenon cancel each other out and consequently do not contribute to determining the nature of the phenomenon. What it expresses is a certain state of the collective mind” (1895/1982, p. 55). However, simply because statistics include “without distinction all individual cases,” it does not necessarily follow from this that “individual circumstance which may have played some part in producing the phenomenon cancel each other out and consequently do not contribute to determining the nature of the phenomenon.” The fact that statistics include “without distinction all individual cases” is an effect of the nature of statistics, not the cause of the statistics themselves, for the cause of these statistics, in the sense of that which ultimately makes the collection of these statistics possible, is without a doubt the occurrence of the individual cases to begin with. The collection of statistics abstracts from these individual cases, in effect obscuring individual circumstances. Therefore, the fact that individual circumstances apparently “cancel each other out” in statistics is an artifice, or illusion, produced by the statistics themselves, that is to say, by the activity of collecting statistics itself. As Mark Twain writes, “There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.” Statistics lie insofar as they “cancel out,” obscure, hide, or disguise, the individual circumstances of the individual cases that they purport to describe. The same conlcusion is also expressed by the popular aphorism of Joseph Stalin, “The death of one person is a tragedy, but the death of millions is a statistic.” The death of one person is a tragedy insofar as we know them as a person, that is to say, insofar as we know the individual circumstances of their individual case, but the death of millions is a statistic precisely because we do not know them as persons, but as an abstract statistic which “cancels out” their individual circumstances and thereby “cancels out” their very personhood, their very humanity. Actual events such as birth, death, and suicide are undergone by real human beings, not by abstract statistics, meaning that they only make sense in the context of the individual circumstances of the real human beings who undergo them. Deaths and suicides, and even births, are most often tragedies, but in certain circumstances may even be comedies, but in each and every case, however, they are always dramatic in the fullest sense, meaning that first and foremost they are individual cases that happen to individual human beings, always with individual circumstances contributing to determining them. These individual circumstances often include not only currents of opinion, or currents of ways of thinking, acting, and feeling, that is, currents of cultural constructs, in addition to ways of thinking, acting, and feeling which are particular to the individual, but also the individual’s material conditions, that is to say, their economic circumstances, which is in any case determined in the last instance by the given society’s economic unit-system, and which in the State is dependent upon the unit-system of violence defining the State. We maintain that the psychical phenomena of a given individual always exist in a dialectical relationship to that individual’s economic circumstances, such that sometimes an individual’s economic circumstances play the dominant role in their life and at other times their psychical phenomena play the dominant role in their life, depending on the circumstances. Statistics can tell us the frequency of an event measurable by them, such as the rates of birth, death, and suicide in a given society, but they can never reveal the processes of individual minds. Moreover, a “collective mind” in Durkheim’s sense, an ideal spirit extraneous to the individuals which concretely form a collective, simply does not exist. The phrase “collective mind” can be used, at best, as a metaphor to describe cultural constructs, but in the interest of accuracy it is best if it were simply abandoned. Durkheim’s sociological method, withs its undue emphasis on statistics at the conscious expense of individual circumstances, can only, in effect, reduce human tragedies to lifeless abstractions, thereby obfuscating, hiding, and disguising them, all the more so when the Durkheimian sociologist produces fictions about ideal spirits such as “social facts” and “the collective mind.” Surveys, which are a kind of statistics, are likewise unreliable because they are lifeless abstractions which do not take into account the lived experiences and individual circumstances of individuals in a given group or society. The only accurate method for sociology, insofar as sociology is indeed the study of society, the only sociological method which enables the sociologist to truly understand phenomena such as births, deaths, and suicides existentially, that is to say, as these phenomena occur in the lived experiences of individuals, and holistically, that is to say, multi-dimensionally, considering all aspects of such phenomena, including individual circumstances, cultural constructs, and material conditions, is ethnography, which includes as its essential components interviews with the actual individuals in the given society one is studying and the observations of the sociologist who is actively participating in the given society they are studying (this latter practice is often called “participant observation”). There can be no true sociology, no true study of society, without ethnography. Insofar as sociology must depend primarily on the existential and holistic method of ethnography in order to truly study society, here there is no difference between sociology and anthropology, either practically or theoretically.

The fact that social phenomena only exist through individuals is one of their essential elements, not an extraneous element. Without individuals, there are no social phenomena. Durkheim anticipates structuralism when he writes, “As regards their [social phenomena’s] private manifestations [“private manifestations” presumably meaning the occurrence of social phenomena through the individual], these do indeed having something social about them, since in part they reproduce the collective model” (1895/1982, p. 55), the “collective model” here meaning roughly the same thing as the concept of “structure” developed by Saussure, Lévi-Strauss, Lacan, and their followers, in that they define “structure” as a “social fact” as Durkheim defines it, an ideal spirit extraneous to all individual subjects. Durkheim himself can be credited as the true originator of the structuralist concept of “structure,” since he does indeed write that there are “social facts” which are “physiological,” “anatomical,” or “morphological” in their essence, by which he means that they form the “substratum of collective life” (1895/1982, pp. 57–58). We agree with Bourdieu’s critique, presented in Outline of a Theory of Practice, that the structuralist concept of “structure” is a lifeless “collective model” that is stripped of the actual lived experience of individuals. Bourdieu’s focus, as the title indicates, is on the existential practices of individuals in a given society, as well as on the intellectual strategizing performed by individuals in relation to their existential practices. There are no “private manifestations” of “structures” or “collective models” because there are no such “structures” or “collective models.” We may more accurately use the term “individual aspect,” as in “individual aspect of a cultural construct,” rather than “private manifestation” to describe the occurrence of social phenomena or cultural constructs through the individual. The individual aspect of a cultural construct is its dimension or degree of freedom of individuality, that is, of occuring in and through the individual; obversely, cultural construction is always an aspect, dimension, or degree of freedom of an individual.

Durkheim writes that each “private manifestation,” which we would describe more accurately as each “individual aspect,” “depends also upon the psychical and organic constitution of the individual, and on the particular circumstances in which he is placed” (1895/1982, pp. 55–56). But Durkheim claims that for this reason individual aspects “are not phenomena which are in the strict sense sociological,” but “could be termed socio-psychical,” which for Durkheim means that “they are of interest to the sociologist without constituting the immediate content of sociology” (1895/1982, p. 56). However, because “social facts” have no real existence, Durkheim is just plain wrong about every conclusion that he derives from the premise of “social facts” being real. It is indubitably true that individual aspects of cultural constructs are indeed “socio-psychical” phenomena, but it is precisely for this reason that they are sociological phenomena, since social phenomena can and do only exist in and through individual psyches, meaning that socio-psychical phenomena are indeed the true and immediate content of true sociology. Insofar as all individuals exist in some kind of relation to a society which is composed of other individuals, even if that society does not yet exist, there is no difference between psychology, metapsychology, sociology, and anthropology, either practically or theoretically; conversely, the true method of true psychology, insofar as psychology is truly the study of the mind, must be ethnography, since human beings, the creatures endued with minds who are overwhelmingly the main object of study for the discipline of psychology, always concretely and practically exist in some kind of relation to a society made of other human beings.

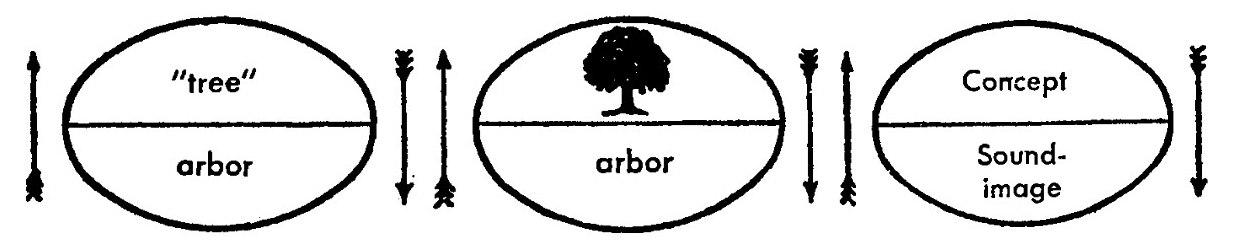

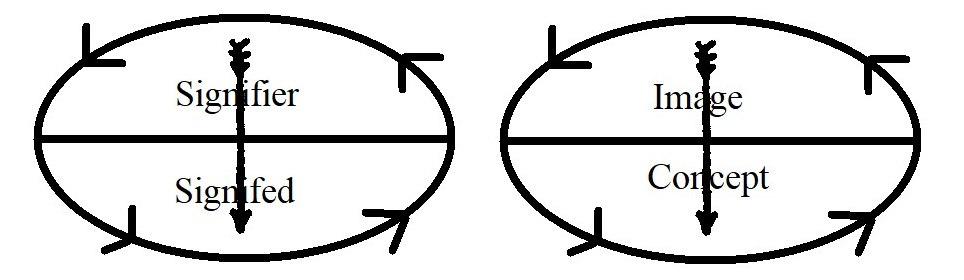

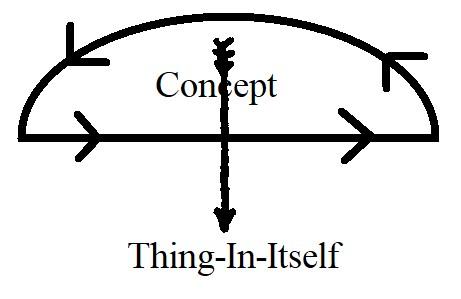

From Deleuze and Guattari’s introduction to their concept of the machine, we may extract two fundamental questions which effectively function as the two foundational questions of schizoanalysis, the two points of entry into schizoanalysis: “Given a certain effect, what machine is capable of producing it? And given a certain machine, what can it be used for?” (AO, p. 3). Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of the machine is meant to negate the structuralist concept of “structure” (in the relevant literature, the terms “system” and “structure” are used interchangeably). The structuralist concept of “structure,” beginning with Saussure and elaborated by Lacan and Lévi-Strauss, denotes a “social fact” as defined by Durkheim, an objective ideal entity (or we might say, following Hegel, an “objective spirit”) that exists independently of all individual minds or all individual instances or manifestations; the structuralist “structure” is always a total and totalizing structure, a totality; we maintain, moreover, that the structuralist concept of “structure” is an eminently idealist and ahistorical concept, which apparently does not change and thus always appears to have come into existence fully formed and seemingly out of nothing, and which is, most importantly, not localizable in any material entity. For example, Saussure’s concept of “language” denotes a total system or structure, explicitly described by Saussure as a social fact, that exists independently of all particular instances of speech and all particular individuals in a given society, and this total structure of “language” exists in a transcendental relation to particular instances of speech such that the total structure of “language” determines all particular instances of speech. We deny the existence of “total structures” such as the Saussurean “language.” In contrast, the Deleuzian-Guattarian concept of the machine is a materialist concept, in that it denotes the material particulars themselves. Each particular is a machine, all matter consists of machines. Whereas structuralist analysis reads everything as so many symptoms of transcendental and ideal (and phantasmatic) total structures (for example, as so many symptoms of a transcendental and ideal “force,” psychopathology, or economic system), machinic analysis reads everything in terms of either the concrete and material effect a given concrete and material machine produces or the concrete and material machine that produced it as a given concrete and material effect.

If we are tempted to use the word “structure” or “system” to describe machines, it is not in the structuralist sense of the word, but in the operational sense of the word, as one might find it used in biology, engineering, or computer science. To distinguish the operational concept of “structure” from the structuralist concept of “structure,” we will specify that the structuralist concept of “structure” is that of a “total structure” (or more simply as “structure” in quotation marks), and we will specify that the operational concept of “structure” is that of a “unit-structure” (or “unit-system”). The word “unit-structure” was coined by Cecil Taylor, who named one of his free jazz albums Unit Structures, and whose spontaneous compositions more generally consisted entirely of unit-structures of sound-objects, sound-machines. A machine is a unit-structure, a unit-structure is a machine, always localizable in time and space, always material. Matter consists entirely of unitstructures. Unit-structures are never total, never totalties, and never totalizing. Unit-structures are always parts among other parts, units among other units. Language only exists in and through particular unit-structures, for example, unit-structures of speech, painting, sculpture, or music; there are only ever language-machines, and there is never any “total structure” of language. A unit-structure is a determinate set of elements that produces a determinate effect. Given a certain effect, there is always a determinate set of elements that produces it; and given a certain determinate set of elements, there is always a determinate effect that it produces; this is the meaning of one of the fundamental axioms of biology, “structure determines function,” which, to be more specific, means “unit-structure determines function,” that is, “a determinate set of elements produces a determinate effect,” and which applies to all unitstructures in every domain. The determinate effect of a determinate unit-structure is precisely that unit-structure’s function. Each unitstructure functions, each unit-structure is a function, each unitstructure is inseperable from its functioning; therefore, each unitstructure is a machine, a production process, since each unitstructure necessarily produces an effect or function. We also note in passing here that function and use are two different things, such that a given unit-structure and its functioning can be used in various ways, such that each unit-structure has both an unvarying defining function and a contextually dependent use-function.

All “post-structuralism” means is “going beyond structuralism,” and since structuralism is founded on Durkheim’s concept of “social facts,” going beyond structuralism necessarily means going beyond Durkheim’s concept of “social facts.” But this word “post-structuralism,” which is nothing more than a cultural construct imposed upon thought by academic institutions, in reality obscures and mystifies the possibility of analysis from a strictly nonstructuralist perspective. Moreover, the word “post-structuralist” inescapably connotes structuralism, and defines whatever it labels in terms of its relation to structuralism, such that structuralism may surreptitiously survive in the guise of “poststructuralism.” Thinkers traditionally labelled “poststructuralists” by academics who have done little to no relevant reading of the primary sources, such as Deleuze (the post-Guattari Deleuze), Guattari, Lyotard, Blanchot, and Foucault, are much more accurately described as “nonstructuralists” if they need to be described in relation to structuralism at all, since these thinkers all reject the structuralist concept of “structure,” meaning that they reject the Durkheim’s concept of “social facts.” Derrida, on the other hand, is a structuralist, insofar as he believes in the concept of structure, meaning that his decision to remain within the discourse of structuralism in order to critique structuralism from within is a failure insofar as he affirms the concept of “structure” which is the basis of structuralism. One cannot remain part of the establishment and at the same time rebel against it, one must always do one or the other, and remaining part of the establishment in order to critique it will always be a failure in terms of rebellion because one affirms the establishment so long as one remains a part of it (however critical one may be of it; that is, however cynically one may accept it). Rebellion is only possible from outside the establishment.

Here, we have developed the concept of cultural constructs as an entry-point to a non-structuralist analysis; more specifically, as an entry-point to the machinic analysis of Deleuze and Guattari, which analyzes the world in terms of machines, that is, in terms of its machinic functioning. Our “post-structuralism,” or rather our nonstructuralism, is the machnism of Deleuze and Guattari, the machnism of schizoanalysis. Machinism is a thought outside Statethought, a rebel thought opposed to State-thought. Machinism is the theoretical precursor to real acts of rebellion, to a lived experience outside the State and opposed to the State. He who refuses to acknowledge the laws and customs of the State as legitimate is by definition an outlaw. Machinism is an outlaw thought, an outlaw theory. Those who support the State, explicitly or tacitly, are right to fear ideas such as the cultural construct (or social construct), since these ideas, logically elaborated, do in fact threaten the perceived legitimacy of the State; the belief in the legitimacy of the State becomes impossible once one understands the full import of ideas such as the cultural construct. If we analyze the State in terms of the cultural constructs and processes of cultural construction that constitute it and its machinic functioning, then we are left facing only the naked brutality and violence that founds and maintains the State, and from there we are faced with a simple choice which depends solely upon the extent of our courage: either support the State or rebel against the State.

Section 2: A Political Ontology of the State