Alejandro de Acosta

The Impossible, Patience

Critical Essays 2007-2013

I Have Even Met Happy Nihilists

Appendix: I Have Even Met Happy Nihilists, Tractatus Version [Excerpts]

Introduction: Proximity

The book’s form

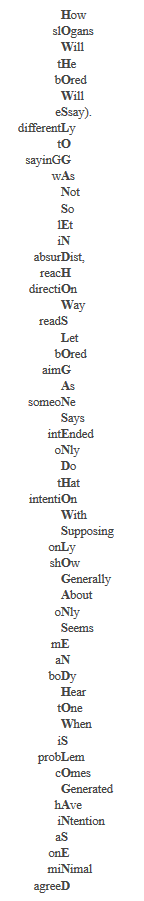

As I wrote the essays gathered in this collection I passed from one writing plan to another. Around seven or eight years ago, following instructive reading of Montaigne, Hume, and Gracián, I had conceived a plan to compose a series of essays. Each would defend an indefensible thesis or at least inhabit a difficult, paradoxical perspective.[1] This was partly out of sheer appreciation for the form and a consequent desire to explore it, but also out of a need to find a way to express what I had to say, insofar as I sometimes felt myself beyond common sense, in a less than prescriptive voice. I was not disposed to continue writing in the prose that composed some of my first published forays into the topics discussed here, which are perhaps more articles or papers than essays. It occurred to me to splice contradiction and abstraction into the flexibility and personable tone of the essay (thus the inclusion of Gracián—certainly not an essayist—in the above list), adding some of the terse contrariness of the thesis. It seemed to me this would prove healthy in two respects: it would save me from the destiny of a certain prose, called “academic” by its detractors, and also, perhaps, counteract what I perceived (and ever more continue to perceive) as the linguistic rigidity around some vibrant subversive projects and in most anti-political conversations. But as the years after 2010 unfolded, I found myself less in the mode of composing essays serially and largely in solitude, according to my older plan, and more in one of dialogue with people from the North American anarchist space or milieu[2]—responding to requests for contributions, or simply acknowledging the appearance of interesting new persons, discussions, readings, and events. In that way a plan for a book of essays on previously selected topics (seduction, boredom, survival, solitude, masks, etc.) changed into the more sequential order of the present collection.[3]

Another way of describing the newer plan of the collection is to note the following. Three essays placed in the middle were written in dialogue with... what is the appropriate designation in this context? Poets? Artists? Creators of difficult creations? In any case, writers who belong to the history of the anarchist Idea, but are rarely discussed in the company I have been keeping: Fénéon, Cage, Duncan. Rather than section these three pieces off in a section on literature or language, or, worse, publish them elsewhere, I opted to insert them into what would have otherwise been a sequence (a syllabus?) of essays where anti-political and nihilist themes deepened, in oblique directions, my explication of that Idea. As I noted, the shift from serial composition to a dialogical mode introduced into the essays a more linear, developmental structure, as if the effects of conversation had led me to more of an explicit parti pris. It seems important to me both to retain something of that structure for the reader and to interrupt it. Otherwise I run the risk of composing a book of theory about nihilist anarchy, something no one needs. If, in the interpolated essays, the engagement with these three figures (as well as that eternal outsider, d.a. levy) remains in the mode of introduction and allusion, I think it’s because I suspected and continue to suspect that many of my readers either have no sense of them as writers or cannot connect what sense they have to anarchist practice—least of all an anarchist practice of reading or writing! Which is all to say that I wrote these pieces to some extent in a teaching mode. I am glad to have touched upon each of these writers here, if only because to name and honor them in my own way constitutes an assertive response to a certain expectation of sloppy writing that characterizes the anarchist space.

If there is a note of patience in these essays about matters that drive people around me to great impatience, then I suppose that I have found it, among other places, in the form itself. I take it that an essay is primarily an exploration of ideas, and only secondarily an exposition. Expectation of getting to the point is replaced by invention of a wandering line in and as the essay. Mine are also informed by a kind of egoism that authorizes me, in its peculiarly empty way, to make whatever I am concerned with my own, as I impersonate the social outsider I often, but with no real certainty, feel myself to be. So to the paradoxical formulation of confounding theses I now add this paradox of form, that the sociable genre of the essay can be deployed so antagonistically at times. In saying so I am respectfully acknowledging those that inspired me to write essays, reassuring all those who think there is something fake at work here that they are indeed correct, and, hopefully, amusing everyone else.

The title’s punctuation

Bill Haver used to say that to think the most important questions one simultaneously requires a infinite patience and infinite impatience. In the coincidence between some friends’ will to destruction and the brevity of most attention spans I sense the infinity of impatience. Omniprevalent rushing to action, conclusions, or whatever is next in the feed does make one feel that patience has never been less possible. But that is just a feeling, something like a premonition, not much more; the present situation is full of dreadful affective indices. Here some minimal resistance, some uncanny intuition, informs me that a strangely infinite patience may still be coupled with our familiar infinite impatience. And that is why the title is not Impossible Patience. Patience is sometimes difficult, but it is hardly impossible. What is impossible is the realization of the Idea of anarchy (which is why many friends, unwitting Platonists, call it the Beautiful Idea). What is impossible would be to fully assume, to truly embody, the resistant positions (quasi-positions, really, as they are anti-political rather than political) most often referred to in this book.

Consider them: the value of the term nihilism, to begin with, has always been that of an insult or accusation. By the time someone calls themselves a nihilist, there is already something of a responsive desperation about the gesture, and not just the straightforward act of naming implied in the common use of the phrase taking a position. Much the same should be said for anarchist, which will be not saved from irrelevance by retroactive conversion into a philosophy, addition of adjectives or prefixes, or assimilation-equation to some liberal or other radical tradition. If it is still fun (though certainly not useful) for me to play with such terms, it is because, first, people in the business of setting and enforcing theoretical and political agendas for others still call their adversaries anarchists and nihilists, and this makes me want to be such an adversary. Second, impressionable, angry, and desperate characters continue to be courageous or foolhardy enough to call themselves anarchists and nihilists, which makes one want to sidle up beside them with an inscrutably patient attention to their destructive inclinations. I share the ethics of those who feel it is impossible to reverse an insult, of those who prefer not to hide from what is said in it (that you are known to be an outcast), but prefer to take it on, to become the nightmares of a nightmarish society. In my own way, I share the ethics, and sometimes lack thereof, of those who know it is impossible to actualize the Beautiful Idea by any instrumental means, including instrumental destruction, and instead bear witness to that impossibility in their dismantlings here and there.

Which is where the intuition’s mark, a comma, my comma, appears: as if in bearing witness to impossibility we learned to stage an impatience with impatience itself. As if to remind that this writing, because it forms part of our punctual actions, must remain fragmented, and that fragmentation, the emptiness that composes it, can only be read in punctuation and spacing.[4]

Patience, then…

Proximity’s distance

Someone whose opinion I value described my approach to writing and publication as emerging from a concern with community. I think I know what he meant. Through these essays, there is an arc of increasing attention and interest with regard to the people, situations, and publications of the milieu. I have been writing with a fairly clear sense of address. For most who care, I write from far away; but I have been flirting with proximity, and it shows. That is what could be called my concern for community. So I accept the evaluation of my esteemed friend, but at the same time I must say that when I think of community in relation to the conversations that contributed to these essays, I mentally cross out the word. The reasons will become clear to attentive readers along the way. For now I’ll say another word about the proximity that brought the book to its newer plan. For me increased proximity has made more conversations possible, but remains something other than belonging. This passage in a life of Spinoza resonates strongly with me:

... he cannot integrate into any milieu; he is not suited to any of them. Doubtless it is in democratic and liberal milieus that he finds the best living conditions, or rather the best conditions for survival. But for him these milieus only guarantee that the malicious will not be able to poison or mutilate life, that they will not be able to separate it from the power of thinking that goes a little beyond the ends of the state, of a society, beyond any milieu in general. In every society, Spinoza will show, it is a matter of obeying and of nothing else. [...] It is certain that the philosopher finds the most favorable conditions in the democratic state and in liberal circles. But he never confuses his purposes with those of a state, or with the aims of a milieu, since he solicits forces in thought that elide obedience as well as blame, and fashions the idea of a life beyond good and evil, a rigorous innocence... The philosopher can reside in various states, he can frequent various milieus, but he does so in the manner of a hermit, a shadow, a traveler or boarding house lodger...

Proximity to the milieu, in contrast to belonging, could be compared to what has been called the Ibn ‘Arabi effect. The Ibn ‘Arabi effect has to do with a possible feedback of the experiences of those who have abandoned the radical milieu into that milieu. If an “anarchist” project were constituted, not to preserve itself and thus the milieu (usually in this order in terms of explicitly stated goals, and in reverse in terms of actual operations), but to seek out those who have quit the milieu, numerous salutary effects might eventually be felt: decreased influence of “young masculinity” (team-building homosociality as the default social bond), less disappointment and more curiosity about the stakes of quitting, maybe even encouragement towards such abandonment as a sign of intelligence. In both cases, in what can be learned by studying the hermit-philosopher’s life and the (for now imagined) lessons of the Ibn ‘Arabi effect, I underline the necessary distance that coincides with space and time to reflect. Approximation makes more conversations possible; distance and feedback allow them to proceed past the inevitable onset of redundancy.

But everything written here out of proximity and reflection on proximity is shadowed by another set of more private, solitary thoughts, no less written into the essays for being private or solitary. Such thoughts not only are private and solitary but concern privacy and solitude as such and are thus at odds with the politics discussed here—though not the ethics, or, alas, the aesthetics. And insofar as I now see how much I was concerned with such thoughts, I wonder why I signed A. de A., and can only tell myself that it was another impersonation, one more mask.

I Have Even Met Happy Nihilists

“I Have Even Met Happy Nihilists” is the result of multiple modifications of a review Kelly Fritsch invited me to write for the Canadian journal Upping the Anti. An edited version of the review appeared there in 2008. It was perhaps the first time that I wrote on nihilism. What I read there now is an acknowledgment that politically salvific leftist theory such as Critchley’s, even as it proclaimed an allegiance with a certain anarchism, excluded most of what I was beginning to find so interesting in anarchist thought and practice. I also register a note of suspicion concerning growing attention to anarchism in the academy. In retrospect, it seems clear that anarchism was being invoked here, not by or for anarchists, but for a socialist or even Leninist Left in need of correction. I am glad that in some small way an anarchist spoke up to trouble the terms of that largely symbolic invocation. Thinking these matters through was enough to let me know I needed to wander off in another direction. The problem, of course, is to figure out how to undo the common flipside of this suspicion, the attitude of some anarchists that our “low theory” (as McKenzie Wark put it in his study of the Situationists) is something entirely sui generis, and so is or ought to be our only point of reference… In any case, this review was the discovery of the anti-political, “impossible”, perspective explored in this collection.

1. The other kind of nihilist

Simon Critchley, a professor at the New School for Social Research, has written a brief book setting out a possible movement from ethics to politics, from commitment to resistance. Infinitely Demanding serves as an index of what is promising and what is a dead end in certain philosophical approaches to Left positions and to anarchism in ethics and politics. Rather than remaining at the level of political theory, Critchley seeks to connect his claims with the activities of protest movements. Here activists could find the rudiments of a common language and some concepts for theorizing their own activity. What those who never did, or no longer do, consider themselves activists make of it is another matter—especially if part of their reason for doing so is putting into question their relation to the Left. For the book is not without the defects of much, if not most theoretical work on ethics and politics: overly narrow theoretical and practical panoramas.

Infinitely Demanding opens by staging the problem of nihilism for ethics and politics: all beliefs or values increasingly seem meaningless and all actions appear equally worthless. A redefined ethics is presented as a way to overcome nihilism, theorized as a singular kind of commitment to a situation or cause that renovates or recreates the meaning of action, and politics appears as the actions resulting from that overcoming: resistance to... mostly to State power, it seems—a problem I will return to. In sum, Critchley proposes that the problem of nihilism is overcome, or at least more convincingly confronted, when ethics moves from being based on a moral tradition, code, or law, to the raw experience of ethical demand, and when politics abandons the project of the seizure of power in favor of an endless resistance.

Critchley begins with a programmatic introduction that presents the problem of nihilism. When he uses this term, he means it in roughly the sense Nietzsche used it in his unpublished notebooks: the “uncanniest of all guests,” etc. Predictably enough, then, Critchley assumes that no one would confess to nihilism. Either one is not a nihilist, or is, but will not confess to it. Such unconfessed nihilists are either passive (“focused on himself and his particular pleasures and projects for perfecting himself”[5]) or active (“various utopian, radical political, and even terrorist groups”). While the category of passive nihilist seems mostly to reflect a critique of unreflective individualism and consumerism, especially of the North American variety, the second is an unlikely hodgepodge of everything from Fourier’s phalansteries (poor Fourier!) through Russian anarchists, Bolsheviks, Futurists, and Situationists, all the way to various ‘70s Left guerillas-cum-terrorists, and finally al-Qaeda, as their “quintessence.” What they all share is “find[ing] everything meaningless, but instead of sitting back and contemplating, [they try] to destroy this world and bring another into being” (5). So here is the problem for Critchley: those who should be politically active, as he considers political action, are nihilists. For him, a way out of both of these forms of nihilism is to turn back beyond the hollowness of meaning that seemingly produces them, returning to the problem of motivation.

Critchley’s uncontroversial assumption is that the social, political, and economic circumstances that currently hold sway (at least in North America) are demotivating. But there do exist conceptual tools to re-motivate unconfessed nihilists, especially in recent ethical theory. Those with a desire for justice, liberation, unbounded passion, or a radically different life might indeed feel close to a certain nihilism as State power continues to grow and capitalism seems ever more absolute and unsurpassable. A differently conceived ethics, however, can give rise to a politics of resistance that does not need or expect to seize power or defeat capitalism—just to resist them from within. Or maybe that just is unwarranted; it is not trivial to state, as Critchley does, that one can be anti-capitalist and anti-State without ever hoping to succeed. He writes: “far from failure being a reason for dejection or disaffection, I think it should be viewed as the condition for courage in ethical action” (55).

I agree that one need not count on success to act. (At a deeper level, this implies the critical uncoupling of what is sayable in theory from what seems possible in practice, thus opening the theoretical imagination to the impossible—which is not to say, the utopian.) But before I go on to Critchley’s treatment of ethics, I will pose two questions. First, why are “we” (who? Critchley uses the vague “we” quite a bit) in the business of motivating anybody? How can we know if we are even in a position to do so? How are we so sure that “they” are not already motivated—perhaps in ways that “we” do not recognize as political? Especially since, according to Critchley, both kinds of nihilism are emanations of a fundamentally religious solution to the problem of meaninglessness? When Critchley asks his readers “how might we fill the best with passionate intensity” (39), who exactly is he referring to? Those among “the best” who have fallen to nihilism? The best among the credulous rest? At the least, his background presuppositions about relations between intellectuals and masses should be made explicit. But, for me, the stakes are greater than that. The unstated and truly fascinating matter is that many are motivated without an explicit ethics. This is a key component of anarchism and seems absent from Critchley’s theory. Second question: Is nihilism always and only a problem? I remain unconvinced that it is, if only because I have met even stranger creatures than the active and passive nihilists Critchley warns us away from. About the active nihilist, Critchley writes that he “finds everything meaningless, but instead of sitting back and contemplating, he tries to destroy this world and bring another into being” (5). If such a nihilist thinks this new world will be more meaningful, he is still too credulous! There are among us passionate people, intelligent people, people capable of acting in a political sphere and of subtracting themselves from it as well—and they confess to nihilism. They do not need to be motivated by anyone; and they often consider themselves to be more sober than the rest of us.

I realize that I have ended up with something other than a critique here. Since, as I am about to explain, Critchley’s ethics has to do with a raw experience, I offered mine, insofar as I have met individuals who contradict or exceed his schema: confessed nihilists, to be precise.

2. Ethics as micro-politics

However it manifests, nihilism undermines beliefs and values that have traditionally composed morality. Critchley seeks to overcome this undermining, provocatively suggesting: “the question of the metaphysical ground or basis of ethical obligation should simply be disregarded … Instead, the focus should be on the radicality of the human demand that faces us, a demand that requires phenomenology and not metaphysics” (55). That is, the emphasis must shift (and after nihilism it cannot but shift) from deducing the foundation of ethics to a phenomenology of ethical experience. What Critchley calls a “demand” is, he argues, impervious to nihilism. It is therefore unsurprising that, although Alain Badiou, Knud Ejler Løgstrop, and Jacques Lacan are all summoned as interlocutors in the discussion of ethical experience and the ethical subject, it is Emmanuel Levinas who serves as the main point of reference. Levinas, in works such as Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority (1961) and Otherwise than Being or Beyond Essence (1974), claimed that ethics has priority over metaphysics or ontology as “first philosophy” and that the first fact of ethics is the face of the Other. One’s experience of the Other is irreducible and primary, preceding even self-knowledge. One’s encounter with the Other is the beginning of experience as such and thus makes all experience, all subjectivity, part of ethics.

One interesting aspect of Critchley’s reading of Levinas is his claim that the nature of ethics is the same for secularists and for theists. A formula: “I experience a radical demand and try to shape my subjectivity in relation to it” (55). If the problem of grounding or justifying ethical theories is set aside in favor of a phenomenology of ethical experience, any sort of ethical experience that brings about the radical demand is good enough: the face of God, of my lover, of the strange neighbor, of the hungry or tortured other. This gesture is fully in line with Levinas’ philosophy, and I find it compelling to some extent; my principal objection is that the categories of secularist and theist invoked here do not exhaustively describe all possible forms of religious and (for lack of a better word) non-religious experience. Could it be that Levinas and Critchley are identifying some basic structure that is, if not hard-wired into the history of “European” or “Western” forms of subjectivation, especially insofar as they reflect monotheisms, at least massively available to the inheritors of those traditions? If so, what about everybody else, here and elsewhere? Do animists or polytheists hear the demand? And what of the poor Buddhists that, in one of his most irritating gestures, Critchley mentions only in repeating the infamous Nietzschean quasi-metaphor that equates Buddhism with passivity and nihilism? How, in short, do those of us who do experience ethics as the cleavage in ourselves relate to all of those who have no self to be cleaved—or have too many for it to matter? Critchley does not address this question. He is rather more concerned to discuss how this cleavage or split in the self need not amount to endless guilt and self-torture. He does this through a discussion of sublimation and humor that incorporates psychoanalytic concepts into his ethics in a bid to remove them from the accusation of vestigial religiosity often leveled at Levinas and his followers. This is all interesting but seems rather secondary given the magnitude of the problems he has raised (so far: nihilism and the putative universality of ethical experience).

Now, returning to the idea that any experience of ethical demand is good enough: is that so? Some of these faces of the Other are intimate, others distant; some real, others imaginary. How to reconcile them all in a single phenomenology? It is not hard to criticize Levinasian ethics for its crypto-religious leanings: it seems the only way to get around the imperative of the moral law was to divide the self, rending it insofar as it was possessed by the Other. A mutually ethical relation would then amount to mutual possession. Obviously many anarchists, especially the egoists, would have no interest in such claims. They might rather hazard a version of what I heard a Korean anarchist say quite charmingly some years ago: “Some days I am ethical ... some days I am not.” Though I do not think this means the idea of a raw experience of ethical demand is useless, I do think it shows its purported universality is a failure. (And this perhaps returns us to a more modest, pre-Kantian ethics, something like the moral sentiments of Hume or Smith, though without their claimed relation to our animal or human nature.) In politics, the problem of nihilism is perhaps not as immediately discernible as it is in ethics. As Critchley describes it, one facet is strategic and has to do with identifying politically effective actions that are in line with the ethical demands one experiences. But prior to that is the question of motivation: Critchley seeks to “provide an ethical orientation” that might support “a remotivation of politics or political action” (90). For him, political action “does not flow from the cunning of reason, some materialist or idealist philosophy of history, or socio-economic determinism, but rather from … a ‘metapolitical’ moment of ethical experience.” This idea of a politics motivated by a morality without sanction is, if not already anarchist in most senses of the word, compelling to many anarchists.[6] For Critchley this ethical component both motivates political action and maintains it as democratic, egalitarian, or at least non-coercive. I would like to underline that this is a different account of motivation than the passage from ethics to politics as usually conceived, because the ethics at stake is situational: theorists or philosophers can recommend actions, motivating people to act, but ethics has no sanction.

For that reason especially, it might seem promising that Critchley attempts to connect his argument with existing movements. “The ethical energy for the remotivation for politics and democracy can be found in those plural, dispersed, and situated anti-authoritarian groups that attempt to articulate the possibility of … ‘true democracy’” (90). I should note, however, that he does not seem to have (or at least never refers to) any direct experience of these movements.[7] When he presents what he calls “anarchic meta-politics” as a basis for and extension of anarchist theory and practice, it’s safe to say that he is not especially familiar with either. With respect to anarchism, Critchley is a combination of a dreamer and a friendly observer. Overwhelmingly, he seems to situate himself primarily in some sort of philosophical Left (that is probably the book’s “we”) that needs to be steered to anarchism while holding on to a certain young Marx. It is not surprising that citations of authors closer to Marxism than anarchism (Ernesto Laclau, Jacques Rancière, Alain Badiou, Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Miguel Abensour) far outnumber references to anarchist texts or movements in Infinitely Demanding. I am not mentioning any of this to maintain some sort of purity or specialization of anarchist thought and practice, but rather to underline to what extent it is an imagined and imaginary anarchism that is under discussion here, whether under that name or something like “anarchic meta-politics” or “neo-anarchism.”

At the same time, Critchley frames his argument as explicitly anti-Leninist (and makes, both in the introduction and the appendix (5-6, 146), the claim that contemporary Islamic terrorism is neo-Leninist). “Politics,” he writes, “is praxis in a situation that articulates an interstitial distance from the state and allows for the emergence of new political subjects who exert a universal claim” (92). That, and emphatically not the attempted or successful seizure of state power. But here there is an enormous problem: if politics is so defined, what shall we call the activities of States? It makes more sense to me to either describe both State activities and the actions of movements as politics, or—and this is by far the more compelling, if under-explored, option: to describe State activities and some of their contestation as politics, and the remainder of what anarchists (and some others) do, outside of movements, as micro- and especially anti-politics. If we accept this second description, then the version of ethics we get is far more fragile: it is neither universally reliable as moral law or raw experience, nor is its motivation of a passage to politics a predictable or desirable effect.

For his part, Critchley maintains that for the foreseeable future, the presence of states is inevitable. What ethically motivated subjects do, then, is confront State power, creating and acting within “interstices.” Critchley illustrates the opening up of interstices with a strange quote from Levinas: “Anarchy … cannot be sovereign. It can only disturb, albeit in a radical way, the State, prompting isolated moments of negation without any affirmation. The State, then, cannot set itself up as a Whole” (cited in Infinitely Demanding, 122). I wonder if Critchley has fully digested what Levinas is suggesting here concerning negation. It also bears underlining that this is a passage, as Levinas made clear (and as Critchley repeats) about philosophical anarchy, and therefore as relevant to the other, confessed, nihilism I have gestured towards as much as to any supposed anarchism or neo-anarchism. Critchley’s interpretation of this philosophy in practical terms amounts to, first, underlining to what extent its demand translates to a thoroughly anti-authoritarian politics (“anarchy is the creation of interstitial distance within the state, the continual questioning from below of any attempt to establish order from above” (122-123)). For him, this is the overall ethical force of anarchism. Secondly, Critchley maintains that “the great virtue of contemporary anarchism is its spectacular, creative, and imaginative disturbance of the state” (123). While I find this philosophical affirmation of protest movements somewhat interesting, I am also deeply troubled at the way it makes confrontation with State power the defining or at least most meaningful moment of anarchist practice. This is to miss out on countless sorts of collective activities, sometimes called communities, not to mention more or less secret individual pursuits. I am referring again to the micro- and anti-political, which, though they are understandably off the radar of an interested outsider, compose for many of us the most significant aspect of anarchy as we are able to live it. This overemphasis on the State is my third major problem with Infinitely Demanding.

3. Hangovers of the Left

Critchley concludes with a telling appendix entitled “Crypto-Schmittianism—the Logic of the Political in Bush’s America.” It offers a schematic conjunctural analysis of the U.S. state and its politics, emphasizing, as the title suggests, the supposed influence of the writings of the Nazi-affiliated political theorist Carl Schmitt on the Bush administration. How did they get re-elected in 2004? “I think part of the story is that certain people in the Bush administration have got a clear, robust, and powerful understanding of the nature of the political. They have read their Machiavelli, their Hobbes, their Leo Strauss and misread their Nietzsche” (133). Meanwhile the Democrats are “too decent, too gentlemanly or gentlewomanly. They are too nice […] It seems to me that they don’t understand a damn thing about the political” (143). Critchley suggests they study Carl Schmitt and Gramsci. The argument as to the bookishness of the Bush Republicans goes so far as to enter into a discussion of whether George W. Bush is stupid (if you care: he isn’t (138); he seems to have read a book and is apparently capable of presenting “theses” (141)). From there, Critchley returns to the main argument of the book, distinguishing between three political alternatives available in the current conjuncture. They are “military neo-liberalism,” “neo-Leninism” (our old friends the active nihilists) and the “neo-anarchism” he recommends.

Without once more invoking the prefix “neo-”, I might point out that, if we stick to the terms of this schema, there is a position missing here. These alternatives are not really alternatives: the neoliberals and neo-Leninists, whoever they are, will never be convinced by reading a book like Critchley’s. The neo-anarchists might find in it a new language for their ethico-political motivation. And those who are inexplicably motivated, within and outside politics? They are the incredulous: confessed nihilists.

Reading the appendix I could not help but feel that I was learning entirely too much about Critchley’s true politics and watching him be dragged back into the perhaps well-intentioned but ultimately self-referential Leftism of so many Continental philosophers—or university professors, for that matter. I was somewhat interested in the image I got from the last chapter, a vision of an ethically inclined phenomenologist charting out a turn to a politics of resistance that had some chances of building a bridge with existing movements and non-academic theorizing. It might have helped make some trouble, at least. The appendix botched that image. I will conclude by explaining how and why it matters.

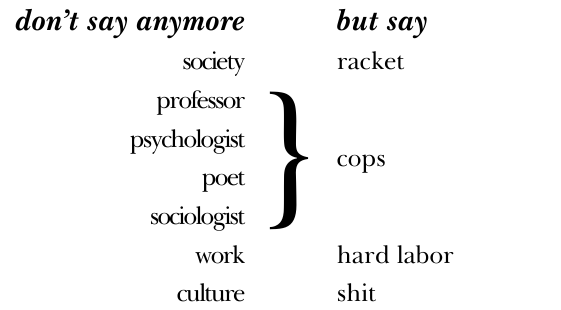

The first aspect of the problem is Critchley’s uncritical identification with Democrats or Left electoral parties. Critchley discusses the U.S. Democrats and what they should do, and whether “we” should support them (143-145). For many of us this is completely irrelevant to the theme of the contestation or evasion of State power, and especially to what we think of as politics and its alternatives. Second aspect: the assumption that the appearance of recognizable philosophical signifiers in relation to the Bush administration signals that it can be understood by study of the texts involved. “They have read …” and so “they understand the nature of the political.” This is preposterous. It is the intellectualist fantasy of a professor. Supposing there is a nature of the political, there is no golden road, no special texts that one must read, to understand it. The third aspect of the problem is a graver version of the second: Critchley devotes space to claiming that “Bush thinks” as though this mattered. What all of this amounts to is the familiar phenomenon of an intellectual who simply cannot let go of the mirage of electoral politics and political figureheads, never realizing to what extent being intellectually and emotionally involved in their activities amounts to anything but resistance.

Despite two awkward references to the “Situationism of Guy Debord” (5, 135) it never seems to occur to Critchley that the Spectacle is more than image-based propaganda. It is a social relation, or lack of relation, really, that makes it possible to speculate, for example, about the reading lists of cabinet members, the plans of huge and institutionalized electoral parties, and even the intelligence or lack thereof of figureheads as though it mattered for the politics of resistance. All the while, engaging in such speculation, we miss the fact that we have been duped into continuing to think of ourselves as belonging on the same purported Left-Right continuum as huge electoral parties, satisfied that we are farther to the Left than the Democrats. This is, it seems to me, the limit of Critchley’s political thought. It is friendly to what he conceives as anarchism, or at least to anti-authoritarian protest movements; but it cannot shake its identification with a Left that continues to define the limits of action in terms of engagement with the State and forbids stepping beyond them—beyond politics. Therefore the anarchism he recommends is reactive. Yes, theoretically inclined activists might learn something about how they are perceived and how they might explain themselves from Critchley’s writing, but there is little here in the way of a broader social or strategic imagination with which they might chart out future actions. And as for the rest of us—my friends the nihilists; those of us, too, who are something other than activists—what remains are curious questions. How do we explain to each other what motivates us, if it is indeed so intimate (which is not necessarily to say private, or personal)? It’s fair to say that some of what Critchley suggests about raw ethical experience, about an ethics without sanction, is relevant here. Is there a way to reject the language of politics and/or activism in favor of micropolitics or anti-politics, so far as we are capable of defining these terms, and the activities and structures they express, other than reactively?

Appendix: I Have Even Met Happy Nihilists, Tractatus Version [Excerpts]

1. Someone writes a book.

1.1 Someone else publishes it.

1.2 In it you find a story of the world.

1.2.1 The story comes ever so close to describing, if not the life you live, something like the life you suppose others live.

1.2.2 Activists, for example.

1.2.2.1 Or those who compose movements.

1.2.2.2 At least those who say they do.

1.2.2.3 And anarchists, maybe, since there is also supposed to be something called anarchism, which is said to overlap with activism or movements.

1.3 But the book is strange.

1.3.1 It tells a story about anarchy, gestures to it somehow, but sideways.

1.3.2 You might wonder what that has to do with your life, your thoughts.

[…]

6. The book is both more and less than what it seemed to be at first.

6.1 Less: the habits of writers run deep, and there is a way such habits have of containing the new even as they strive to name it.

6.2 More: in all the flag-waving there might be an interstice.

6.3 A place and a time, however contingent, however passing, where and when to say: here some others and I lived.

6.3.1 Because we lived, sometimes we were ethical.

6.3.2 And almost no one noticed or understood.

Its Core is the Negation

This is the first in a trilogy of essays on approaches to nihilism, the other two being “History as Decomposition” and “Green Nihilism or Cosmic Pessimism.” It is focused on Duane Rouselle’s After Post-Anarchism, a book that caused me no small amount of frustration. I was pleased to discover something in it worth sharing with many who I knew would never make it through its pages, so I tried to write it out for them in Anarchy: A Journal of Desire Armed, where it was published in 2013. It was also, then, a gift to that publication, which I recall reading with interest around 1991-1992, and where I had published some playful essays in more recent years. In this essay, the feeling of there being something new to say took a hybrid form, combining a “report on knowledge” with a personal philosophical narrative. This is also the place to remark that, in the same vein as Duane’s book, the reading (and re-reading) of the writings of Monsieur and Frère Dupont have been for me, as for a few others, the source of an uncanny clarity; they receive brief explicit mention here, but their salutary influence should be clear.

1

I have always considered my inclination to anarchy to be irreducible to a politics. Anarchist commitments run deeper. They are more intimate, concerning supposedly personal or private matters; but they also overflow the instrumental realm of getting things done. Over time, I have shifted from thinking that anarchist commitments are more than a politics to thinking that they are something other than a politics. I continue to return to this latter formulation. It requires thinking things through, not just picking a team; it is more difficult to articulate and it is more troubling to our inherited common sense.[8] I do not think I am alone in this. It has occurred to some of us to register this feeling of otherness by calling our anarchist commitments an ethics. It has also occurred to some of us to call these commitments anti-political. I think these formulations are, for many of us, implicitly interlinked, though hardly interchangeable. What concerns me here in the main is the challenge of what it could mean to live out our commitments as an ethics—though I think the relevance of this thinking to anti-politics will be clarified as well.

I intentionally write ethics, and not morality: as I see it, ethics concerns the flourishing of life, the refinement of desirable ways of life, happy lives. Tiqqun put it well:

When we use the term “ethical” we’re never referring to a set of precepts capable of formulation, of rules to observe, of codes to establish. Coming from us, the word “ethical” designates everything having to do with forms-of-life. ... No formal ethics is possible. There is only the interplay of forms-of-life among themselves, and the protocols of experimentation that guide them locally.[9]

Many of us have been able to reject morality as a form of social control, as the stultifying pressure of the Mass on us, as imposed or self-imposed limitation on what we do and what we are capable of doing. Much the same could be said for any ethical universalism which, though emphasizing ways of life and not moral codes or injunctions, tends to homogenize ways of life in the name of a shared good; it does so by surreptitiously presupposing that good and treating it as a natural fact or self-evident transcultural reality. In short, it rejects transcendent morality only to re-introduce it immanently. Our rejection of this single Good went often enough in the direction of pluralism: the story went that there were many Goods, many valid or desirable forms of life. This seemed obvious enough, even intuitive, to many of us. The story went well with anarchist principles of decentralization and voluntary association, and resonated with many in the years when anti-globalization rhetoric emphasized Multiculturalism as a practice of resistance and The Local as the site of its practice. It also made sense, or at least was useful, insofar as it was an efficient way to communicate an anarchist perspective to non-anarchists, especially to potential anarchists.

So here we have two different approaches to ethics. One tries to secure access and orientation to a single flourishing form, the criterion being that it be understandable by all: the Good unifies. The other approach claims that there are many such forms, and this plurality itself is the criterion: the Good distributes itself into Goods. Always suspicious of universalizing claims, for many years I sided (more or less comfortably) with the latter, participating in a game of adding -s to the end of words like people, culture, gender, and so on. Though I was never too concerned to recruit, so that the benefits of communicability were irrelevant to me, this game nevertheless seemed linked to an affirmative gesture, affirmative specifically of difference and plurality in the political sphere. There was always the question of recuperation, i.e. that governmental and other institutions so easily incorporated such pluralism into their functioning as its liberal pole (the conservative pole, which was always present implicitly at least, had to do with norms of governance or rule-following generally). For example, these days university administrations trumpet Multiculturalism louder than anyone else, and Locally Sourced is a hot marketing term. This troubled those of us who took this side, but we countered by emphasizing what could be called raw plurality as opposed to the masticated, digested, and regurgitated version we got from administrators and mouthpieces of all sorts. Choosing pluralism, eagerly or grudgingly, we might have ended up as uneasy relativists; or we might have been working hard to expand the frontiers of liberalism and democracy, there where the word radical finds its most docile partners...[10]

I have come to realize, after what I now recognize to be good deal of confusion, if not unconscious hedging, that even as I labored on the limits of pluralism, my thinking was incongruous with that position. My writing and conversations repeatedly gestured in the direction of another position, irreducible to universalism and ever more desperate attempts at pluralism. It is a nihilism that denies the validity of the singular Good at the heart of universalism, as well as the distinct senses of the Good at the heart of pluralism. For nihilists, the only ethical gesture is negative: a rejection of the claims to authority of universalism and pluralism. For us, all such claims are empty, groundless, ultimately meaningless. And this is what was really at stake in distinguishing ethics and morality. My idea of a happy life is not something I reason my way to, or choose, but rather something that manifests senselessly... but I can use my reasoning (my judgment, even!) to help in pushing back, reducing, destroying everything that blocks my way of life.

This report on what must be not only my own trajectory, but also part of the history of the last twenty-five years (more or less for some others) is due in part to some crucial pages in Duane Rousselle’s After Post-Anarchism that consolidated this thought of nihilism for me. Rousselle argues that the nihilist position I have just described has always been the ethical core of anarchism, and that we are now in a moment where this may finally be recognized.

2

I want to respond to After Post-Anarchism because it contains that significant provocation. Unfortunately, for most of its readers, this book cannot but be an exotic object. To whatever degree it discusses familiar ideas or even lived situations, it does so through arcane routes. Yes, it is difficult reading; but it is not by engaging with what is most difficult in it that readers will happen upon the few remarkable insights that it contains. Rousselle’s writing is difficult because of the density of his references and because of an unfortunate penchant for wordiness and digression. Although I would be the last to say that every idea articulated in theoretical or abstract terms can also be phrased in ordinary, so-called accessible language, I suspect that much of what I find valuable in After Post-Anarchism can indeed be restated otherwise. I intend to do so here. As I noted, this aspect of After Post-Anarchism struck me as an unusually clear formulation of thoughts I had been struggling to express for years (among other places, in the pages of this magazine). So, instead of a broader critique of post-anarchism (which Rousselle has a knack for folding back into a plea for its relevance) I will limit myself to some brief remarks about his misprision of the respective roles of theory and practice.[11]

Post-anarchism receives numerous formulations in this book, but really only two definitions. The first is simply that it is a “discursive strategy” (31): not so much a theory as the outcome of ongoing discussions and debates in a theoretical space where anarchism, post-structuralism, and new social movements (as theorized by their participants and outsiders) intersect. In this respect I could make many objections or clarifications, but I will simply note that for such investigations to proceed as Rousselle intends, anarchism (as “classical anarchism,” 4 and passim) must be interpreted as “anarchist philosophy,” sometimes “traditional anarchist philosophy” (39 and passim).[12] The second definition, which follows from the first but is more provocative, is that post-anarchism “is simply anarchism folded back onto itself” (136). For Rousselle this means an anarchic questioning of the ethical basis of anarchism, a search for the anarchy in anarchism; he later specifies his own version of this folding in terms of the distinction between manifest and latent contents of statements.

Here I can underline both the weakness and the promise of Rousselle’s approach. Whatever the silliness of the term post-anarchism, I think the second definition’s project of questioning, of folding back reflexively, is of interest to any anarchist who does not take their position on questions of morality and ethics (or anything else, for that matter) for granted. When he is pursuing this sort of questioning, Rousselle is at his strongest. When he is treating the anarchist tradition interchangeably as a series of historical figures, events, practices, etc. and as the discursive or conceptual framing that can be abstracted from them (“anarchist philosophy”), he is at his weakest. He repeatedly falls into the intellectualist trap of describing actions as the result of pre-existing theoretical attitudes. “Can we at least provisionally admit,” he asks rhetorically, “that anarchism is not a tradition of canonical thinkers but one of canonical practices based on a canonical selection of ethical premises?” (129). Freeing himself from the idea of an anarchist movement set into motion by a bearded man’s intellect, he remains on the side of the intellect by presupposing of a pre-existing set of premises on which practices are “based” and from which they derive their status as “canonical.”

One more critical remark about the weakness in this approach. Rousselle describes post-anarchism in a third way, and this one is not so much a definition as an illustration. He writes that post-anarchism is the “new paradigm” (126) of anarchist thought: “The paradigm shift... that made its way into the anarchist discourse, as ‘post-anarchism,’ allowed for the realization and elucidation of the ethical component of traditional anarchist philosophy” (129). He is so zealous in his promotion of this term that several times in his book he annexes authors who explicitly reject the term, such as Uri Gordon and Gabriel Kuhn, to the cause. This all seems to me to be in bad taste. There is also a more profound problem at stake: paradigm shifts do not happen because one says they do. The declarative, performative wishes evidenced whenever Rousselle uses the language of advancement or progress, as though what was at stake here was a science, tell us much about his intentions, but always fall flat in terms of convincingness. Even if there is a paradigm shift at work in anarchist theory (or practice!), there is no reason to consider the shift as an improvement. We are probably just catching up to an increasingly complex, chaotic, and uncontrollable world. So I fault him for misunderstanding what a paradigm shift is, for wildly exaggerating the overall importance of post-anarchism, and for framing anarchism too abstractly as an inchoate philosophy. Nevertheless, returning to my principal reasons for writing this essay, I will now praise Rousselle, for some of what he writes about ethics.

3

Early in After Post-Anarchism Rousselle states that, answering what he calls “the question of place” (roughly, on what grounds do you make an ethical claim?) there are three types of responses. There are universalist theories, which state that “there is a shared objective essence that grounds all normative principles irrespective of the stated values of independently situated subjects or social groups” (41). This would include most religiously grounded moralities, as well as appeals to human nature. Most such theories are absolutist, but they need not all be so; utilitarianism is an example of a “normative theory that proposes that the correct solution is the one that provides the greatest good to the majority of the population.” The second set of theories, which corresponds to what I called pluralism in the opening section, is what Rousselle refers to as ethical relativism. “Relativists believe that social groups do indeed differ in their respective ethical value systems and that each respective system constitutes a place of ethical discourse”(43). That is, there are different systems (of belief, culture, custom, etc.) that may ground morals. Again, there is an interesting subset, a limit-case: “At the limit of relativist ethics is the belief that the unique subject is the place from which ethical principles are thought to arise”(43). This corresponds to most types of individualism.

The provocation I am underlining in Rousselle’s book is that, rather than try once more to save pluralism by pushing it farther into a parodic relativism, he pursues what he calls ethical nihilism. His first stab at a definition runs: “ethical nihilism is the belief that ethical truths, if they can be said to exist at all, derive from the paradoxical non-place within the heart of any place” (43). That is, nihilism denies the ground, or at least the grounding or claim to grounding, in ethical universalism and pluralism. “Nihilists seek to discredit and/or interrupt all universalist and relativist responses to the question of place [...] nihilists are critics of all that currently exists and they raise this critique against all such one-sided foundations and systems” (44–45). Obviously, this completes the triplicity with which I began this essay.

It is from this triplicity that Rousselle develops his analysis of ethics in relation to anarchism. Rather than argue about existing moral codes or ethical paths, Rousselle suggests that another position has so far remained largely undiscussed: the nihilist one that rejects the authority or normativity of such argumentation. He states that post-anarchists, so far, have approached “classical anarchism” as a universalism (generally based on human nature) and sought to redistribute its ethical impetus in the direction of relativism. What Rousselle seeks to do, by contrast, is to make explicit the implicit core of classical anarchism; and that core, according to him, is ultimately nihilist. “One must therefore seek to remain consistent with the latent force rather than the manifest structure of anarchist ethics, for there is a negativity that is at the very core of the anarchist tradition” (98–99). Centering his discussion on Kropotkin, Rousselle claims that while Kropotkin’s manifest ethics was clearly universalist (grounded on an appeal to human nature), his latent ethics was nihilist. “If it can be demonstrated that Kropotkin’s system of ‘mutual aid’ also called for the restriction of the free movement of the individual then it can also be argued that his work, like much of traditional anarchist philosophy, was always at war with itself” (146).[13] The ethical nihilism is revealed by chipping away at the manifest content of the old saws, serially revealing the conflicts they conceal, the latent content that was always implied in them:

-

Anarchists are against the State and Church

implies…

-

Anarchists are against the structures of representation and power at work in the State and Church

implies…

-

Anarchists are against any other structures of representation and power analogous to those at work in the State and Church

implies…

-

Anarchists are against any structure of representation and power

implies…

-

Anarchists are against all authority, all representation

implies…

-

Anarchists are against …[14]

Now, most anarchists will drop off at some point in the chain of implication, judging it to have gone too far past what they regard as common sense. (Our enemies might be less inclined to think they have gone too far.) What does this mean? Roughly speaking, that under analysis the initial emphases on opposition to state or religious authority give way to an unbounded hostility to all authority; that the opposition to political representation opens onto being against all representation; and that the critique of the unfoundedness of existing moral codes concludes in a sense of the ungroundedness of all morality. And they do so in two senses: historically, as the overall tendency of anarchism has sufficient time to develop (that it will be repressed and denied by its adherents as well as enemies is not evidence against this); and psychologically or subjectively, since this overall tendency is also an intimate matter in the life of individuals, part of the unconscious of its first and present proponents (and so analogous claims about repression by adherents and enemies most certainly apply).[15]

Rousselle suggests that, although most post-anarchists thought they were improving upon anarchism or developing its intuitions, they were in fact rendering it more docile, because more akin to liberal ideals; he, on the other hand, has revealed its nihilist core, its true and original inclination to anarchy. The problem now becomes: when anarchists disavow this nihilist core, opting for some version of relativism (or universalism!), how do we answer them? For the same reasons that I do not take Kropotkin’s or Bakunin’s manifest ideas as my guides, I do not take what analysis might reveal as their latent content as my guide. And if I do not find this kind of argumentation compelling, why would I use it on another? This is where Rousselle’s intellectualist assumptions undercut the force of his claims. I do think, however, that the ethical nihilist position is at the core of most anarchist discourse and practice, as its latent content. That is, I think he is basically right, not specifically about so-called classical anarchism, but, proximately and for the most part, about anarchists. Rousselle’s psychoanalytically inspired method of reading texts should be transformed into a rhetoric, or rather a counter-rhetoric, that can intervene in the present more directly. What he does with old texts, others might be able to do with people, groups, and contemporary texts. But how and when to use this counter-rhetoric? The least I can say is that I am not in the business of convincing anyone about what they really think. I may well keep my analysis to myself, or state it in resignation of being misunderstood; or I may use it to attack. Whatever the case, the nihilist position will be known in that it exposes the differend between itself and the others, and between the others and themselves.

This is consistent with the basic formulation of nihilism as a negative ethics. Actions taken in its name are always provisional: to reiterate from Theory of Bloom, all we have and all we know is “the interplay of forms-of-life” and “the protocols of experimentation that guide them.” No one knows what the world would be like if it were populated with nihilists alone! Following the previously cited sentence on the negativity at the core of the tradition, Rousselle cites one of his sources, the moral philosopher J.L. Mackie:

[W]hat I have called moral scepticism is a negative doctrine, not a positive one: it says what there isn’t, not what there is. It says that there do not exist entities or relations of a certain kind, objective values or requirements, which many people have believed to exist. If [this] position is to be at all plausible, [it] must give some account of how other people have fallen into what [it] regards as an error, and this account will have to include some positive suggestions about how values fail to be objective, about what has been mistaken for, or has led to false beliefs about, objective values. But this will be a development of [the] theory, not its core: its core is the negation. (99)

In my language, the negation corresponds to ethics as a way of life; the account of error, to what I call a counter-rhetoric. I praise Rousselle, then, because he contributed to a defense of what is negative in anarchism, while also hinting at a defense of negativity as such. He makes space for us to read passages such as the one by Mackie, above, creatively, offering them to us as lessons—logical lessons about what anarchy means. Its core is the negation.

4

Such logical lessons are useful, arguably necessary, if we want to discard hope at this juncture and think with more sobriety. Most of the thinking from this perspective remains to be done. It concerns the conjunctions and disjunctions between several senses of nihilism. First, there are those most familiar in the milieu as positions: nihilist anarchy and nihilist communism. Second, there is nihilism as a theoretical concern in other writers, from Jacobi to Baudrillard. Lastly, there is the diagnostic sense of nihilism inherited from Nietzsche. Articulating these with the ethical nihilism Rousselle discovers/invents at the core of anarchism will be a complicated task, so I will limit myself here to an enumeration of provisional consequences stemming from what I have written so far. I offer these consequences as a relay from After Post-Anarchism’s provocations to the thinking that remains to be done: to make it possible, to prepare it as best I know how. The first two consequences suggest how we might deploy the triplicity to understand and critique contemporary anarchist approaches. The latter two concern the broader relevance and context for ethical nihilism, setting out from the anarchist context.

The first consequence is that it is now clear that many contemporary anarchists confusedly combine ethical universalism with ethical pluralism; and ethical universalism with ethical nihilism. In a society like ours, one whose ideal is supposedly liberal democracy, we should expect pluralist language to be the most likely one in which radicals will offer their analysis and proposals. Community organizing, consciousness-raising, and so on, have obvious links to liberalism and are at best its radical forms. As a result, moralistic types — those who publically advocate a renewal of society, an improvement of government and management (as self-government, self-management), suggesting pluralist approaches — are likely to refuse to discuss or make explicit the universalist core of their thought. Others might advocate the same practices, while privately sensing or even admitting the hollowness of the values they defend. (One disingenuous result of these private/public conflicts is the unrestrained impulse to act no matter what, as though action can never be damaging or compromised, coupled with claims that it is all an experiment, that we are learning as we go, and so on.) This offers a new perspective on the emergence and significance of second-wave anarchy[16] generally, including post-Left anarchy, green/anti-civilization anarchy, and, I suppose, post-anarchism as well, all of which might now be seen as attempts to analyze and reveal these contradictions, to make explicit the ways in which anarchist discourse was always at war with itself.

The second consequence complements the first: another set of anarchists confuses ethical pluralism with ethical nihilism. Here merely stating the ethical nihilist position coherently has effects. In this respect I think of those who might have overcome the liberal value-set in politics, advocating destruction of the existent, but continue to drift back to pluralist/relativist perspectives in everyday life and problem-solving due to a lack of imagination. This probably results from unconsciously positing a pluralist society as what comes after a destructive moment, while not consciously framing destructive action as having any particular goal beyond destruction of the existent. I should add here that it would be hasty to collapse the ethical nihilist position into any one practice or set of practices. Destructive practices, partial or absolute, do not follow mechanically from negation. Destruction is not the practical application of a negative theory. I am certainly not saying that destruction is not worthwhile as a practice or set of practices; but I am saying that nihilists by definition reject the overidentification of any practice with their negation of existing moralities and normative approaches to ethics. It is my sense that, once the nihilist position exists as something other than a caricature, the other positions will be increasingly undermined from within and without.

The third consequence is that ethical nihilism is more than a theory. It is a way of living and thinking, a form-of-life in which the two are not separate. That Rousselle discusses it only as a theory leaves it to the rest of us to elaborate what else it is, what it looks like, as some say, or how it is practiced. It is my sense that he was able to write this book because of events and situations in his life, in the milieu, in other places. So when I invoke the practical aspect of nihilism, having already said that it cannot be reduced to any practice or set of practices, I mean two things. First, that I mean to underline the unusual tone of all the practices of those that accept some version of the perspective that there is no Outside (to capitalism, civilization, or the existent), or that are profoundly skeptical about any proposed measures to get Outside. Second, that to speak of practices related to ethical nihilism continues to make it seem like a theory that endorses or suggests a course of action, while its interest is precisely that it may not do so. Monsieur Dupont’s phrase Do Nothing is relevant here: “Do Nothing... was and remains a provocation. [...] Do Nothing is an immediate reflection of Do Something and its moral apparatus.”[17] From weird practices to doing nothing: this is precisely the enigmatic space where anti-politics converges with ethics. Yes, there is a gap, perhaps a colossal gap, between the implosion-moment of societies like ours and the eternal meaninglessness of value claims and moral codes. Anti-politics might be said only to address the former, while ethical nihilism ultimately invokes the latter. But anti-politics may also reveal ethical nihilism; our willful action may accelerate the ex- or implosion of the world to reveal more of the meaninglessness it has been designed to conceal.

The fourth consequence is that nihilism is also a condition. It is not merely those who make it their business to think and act in the world that are living with nihilism. The force of ethical nihilism is not so much in being a position one advocates as in its undermining of others’ claims to certainty. If we are able to do this sometimes it is because there are many others who, in a rapidly decomposing society, more or less consciously grasp the hollowness in every code of action. Take this passage from Heidegger as an illustration:

The realm for the essence and event of nihilism is metaphysics itself, always assuming that by “metaphysics” we are not thinking of a doctrine or only of a specialized discipline of philosophy but of the fundamental structure of beings in their entirety ... Metaphysics is the space of history in which it becomes destiny for the supersensory world, ideas, God, moral law, the authority of reason, progress, the happiness of the greatest number, culture, and civilization to forfeit their constructive power and to become void.[18]

Dare I add here that something of this condition was also gestured toward in a few precious texts on postmodernism, texts which raised tremendous questions about their present, and by extension ours, only to be buried in an avalanche of increasingly unimaginative discussions, as if to systematically shut down the possibility of such questioning?

What these four consequences add up to is perhaps something on the order of a paradigm shift that some of us are perhaps dimly beginning to perceive. Or perhaps it is much bigger and more terrifying than a paradigm shift could ever be. Rousselle overestimates the importance and centrality of post-anarchism to anarchist theory (and, needless to say, various milieus), and his claim that his theorizing after post-anarchism consolidates the shift from pluralist/relativist post-anarchism, with its reformist and radical liberal tendencies, and a fully nihilist theory expressing the latent destructive content of anarchism, is misplaced. But increasing emphasis on nihilist ideas, and the increasing prevalence of what could be called nihilist measures, is a condition that involves us all to some degree. And we have tried to think it through and respond. The call for an end to government instead of a better, more democratic, more egalitarian form of government is ancient. The call for the abolition of work instead of just, fair, or dignified work is decades old, at least. How many of us no longer criticize competition so as to contrast it with cooperation, but because the victory it offers is laughably meaningless? How many of us have more or less explicitly shifted from advocating a plurality of genders to pondering the conditions for the abolition of gender as such? What to make of the increasing opposition to programmatism[19] and demands in moments of confrontation and occupation?

I intuit two things here: that pluralism seems to continually reveal its relativist core more and more often, and that the revelation of the relativist core will make it increasingly easier for the nihilist position to be stated, with all of its disruptive effects. Conversely, as I have suggested, merely stating the nihilist position coherently has effects. I propose that those interested make it their business to deploy the triplicity. To which I will immediately add: there will be stupid and parodic versions of this moment. For some of us this moment will be lived entirely as parody and stupidity. But there will also be, for some, an opportunity to refine what our anarchism has always meant, not as the direction history or society is going in, not as the truth of a tradition, or as an ideal of any sort, but as that which breaks from such orientations in the most absolute sense: the negating prefixes a-, an-, anti-... anti-politics as a provisional orientation, branching out into countless refusals.[20] Our ethics emerges and gives itself to thought only where breaks and refusals clear a sufficient space. We know almost nothing about such spaces, so our ethics might also be defined as the provisional disorientation with which we approach our ways of living, the interminable and necessary skepticism that characterizes our thinking’s motion.

Fénéon’s Novels

“Fénéon’s Novels” was extemporaneously created at the Renewing the Anarchist Tradition conference in 2007. I visited this gathering four or five times over the years and made some good friends there. Among other things, extemporaneously created here means that the excerpts from Fénéon cited were 1) intended to familiarize listeners with material none of them had read 2) chosen more or less at random—which random order was preserved in the written form and informed its transformation into the present piece. I later created this more writerly version with helpful feedback from Joshua Beckman. It was accepted (by one editor) and then rejected (by the rest) for a book on contemporary political movements, which seems appropriate; it both is and is not about contemporary political movements. It addresses some of the thinking on language discussed more broadly in “To Acid-Words” by focusing on a specific kind of writing that might easily be overlooked, thus staging the question of what to do with all of the writing that we don’t want to consider writing. Relatedly, here I say some things about ethics from a somewhat different perspective than the preceding essays: ethics as a way of attending. (A similar view is discussed in a piece not included here, “Anarchist Meditations”.)

Meanwhile the newspapers took over the task of recounting the grey, unheroic details of everyday crime and punishment.

— Foucault, Discipline and Punish

1. Tiny Novels

You are about to read five novels.

Lambézellec, Finistère, were already

so drunk it was necessary to lock them

up within the hour.

Countering the prosecution in

court at Saint-Étienne, Crozet, a.k.a.

Aramis, presumed prolific thief, met

all questions with silence.

(brevity)

taken the wrong way by the court at

Nancy, earned a month in prison for

the agitator Diller.

Marie Boulanger, a gilder, is in Cochin

recovering from a knife wound given

to her by Juliette Duveaux. The

young women were mutually envious.

A corpse floated downstream. A

sailor fished it out at Bolougne. No

identification; a pearl grey suit; about

65 years old.[21]

Yes, novels; brief novels, novels in three lines. They were published anonymously in the form of a faits-divers column in the Parisian newspaper Le Matin. The date was 1906. Félix Fénéon took a temporary job working at this liberal newspaper, with a circulation around half a million, translating wire reports and town gossip into the 1,220 novels that have survived. Each one is a report assembled from a minimum of information. Each is also carefully composed as a minute novel. It is as though Fénéon interpreted the column’s title, nouvelles en trois lignes, in both of its possible senses: “the news in three lines” and “novellas in three lines.”

through the ceiling, and invading the

premises, thieves took 800 francs from

M. Gourdé, of Montainville.

Five hundred cigars and 250 flasks of

wine: booty netted by burglars who

visited the villa at Le Vésinet, of the

soprano Catherine Flachat.

(virtuosity)

cried the murderer Lebret, sentenced

at Rouen to hard labor for life.

Schoolboys in Vibraye, Sarthe,

attempted to circumsize a child. He

was rescued, although dangerously

lacerated.

There were 12,000 francs in the safe

of the rectory at Montmort, Marne.

Burglars took it.

In these novels, Fénéon’s prose balances painstaking precision and dry wit. This was also the style of his art criticism and of the pieces he published in anarchist newspapers.[22] He was always reticent about publication; he often signed his articles “F. F.” or with generic names such as Hombre. Unprolific, then, given to a certain anonymity, Fénéon was deliberate about when and where he wrote—and more importantly, how.

2. A Way of Life

Whatever he might have called himself, I find it useful to call him a dandy. I consider dandyism to have been a lived philosophy.[23] I mean the way of life of anyone who has developed a complete aesthetics of existence, as one might once have developed or accepted, in the ancient Hellenistic schools especially, an ethics of existence.

Dandyism, the modern form of Stoicism …[24]

His manner of speaking, the tone of his voice; his style of dress, the way he did or did not appear in certain places; the way he formed or cut off friendships, the nature of his love affairs: all of these expressed an overall aesthetics of existence.[25] How can this be related to the fact that, at least when he wrote the novels, Fénéon’s political sympathies were with the anarchists? It was the familiar anarchism of the late nineteenth century, with its pragmatically materialist view of history, science, and progress, its visceral anti-clericalism and anti-patriotism, and its vital infusion of egoism. This last aspect is perhaps how the dandies were able to make common cause: an emphasis on the individual and his or her self-presentation answered to both ethical and aesthetic sensibilities, offering the promise of their convergence. There are a number of figures who could be retroactively described as having, as part of their aesthetic sensibility, radical political sympathies.[26]

Terbeaud from the top of a pyre made

of his furniture. The firemen of Saint-

Ouen stifled his ambition.

(startling)

jumped in the river, tried in vain to

throttle, aided by his Great Dane, the

meddler who was dragging him out.

Two Malakoff blacksmiths were rivals

in love. Dupuis threw his hammer at

Pierrot, who in turn tore up his face

with a red-hot iron.

Now, an uncertainty: Fénéon may have been the one who deposited a bomb that detonated outside the Hôtel Foyot on April 4, 1894. Whether or not he was responsible, this attentat belonged to the violent political climate of that Paris: often enough, brutality against the poor resulted in the anonymous bombing of a bourgeois restaurant or aristocratic opera house. Fénéon may or may not have done this; he was tried for it. His biographer, Joan Halperin, summarizes contemporary accounts of his demeanor before the judge and prosecutor:

cool and reserved, his mean, sharp

face expressionless except for a brief

smile that flashed his scorn once or

twice at the court.[27]

She excerpts from the interrogation:

friend of the German anarchist,

Kampffmayer.

Fénéon: The intimacy could not have

been very great. I do not know a word

of German and he does not speak

French.

(Laughter).

Judge: Matha, under indictment for

antimilitary propaganda, stopped at

your house when he came to Paris.

Fénéon: Perhaps he was short of

money.

Judge: When you were arrested, you

were asked if you knew Matha. You

said no!

Fénéon: Yes, systematically. I was not

used to being in handcuffs, and at

that moment, I wanted to have time

to think.

Judge: It has been established that you

surrounded yourself with Cohen and

Ortiz.

Fénéon (smiling): One can hardly be

surrounded by two persons; you need

at least three.

(Explosion of laughter).

Judge: You were seen speaking with

them behind a lamp-post!

Fénéon: Can you tell me, Your Honor,

where behind a lamp-post is?[28]

Here is a first clue concerning the style of the novels. Fénéon kept his composure, responding to the interrogation with impeccable witticisms. His responses reveal an almost impossibly well-calculated precision and humor. They also tell us something about F. F.’s aesthetics of existence; they are evidence of an utter commitment. Even in a situation where one could be sent to prison or put to death, one did not give up on the witty repartee, on holding one’s own against a boorish interlocutor. Our novels are also marked by such a commitment; not, however, before the judge and prosecutor, but before the banality of everyday life and the boredom of work.

3. Brevity and Relation