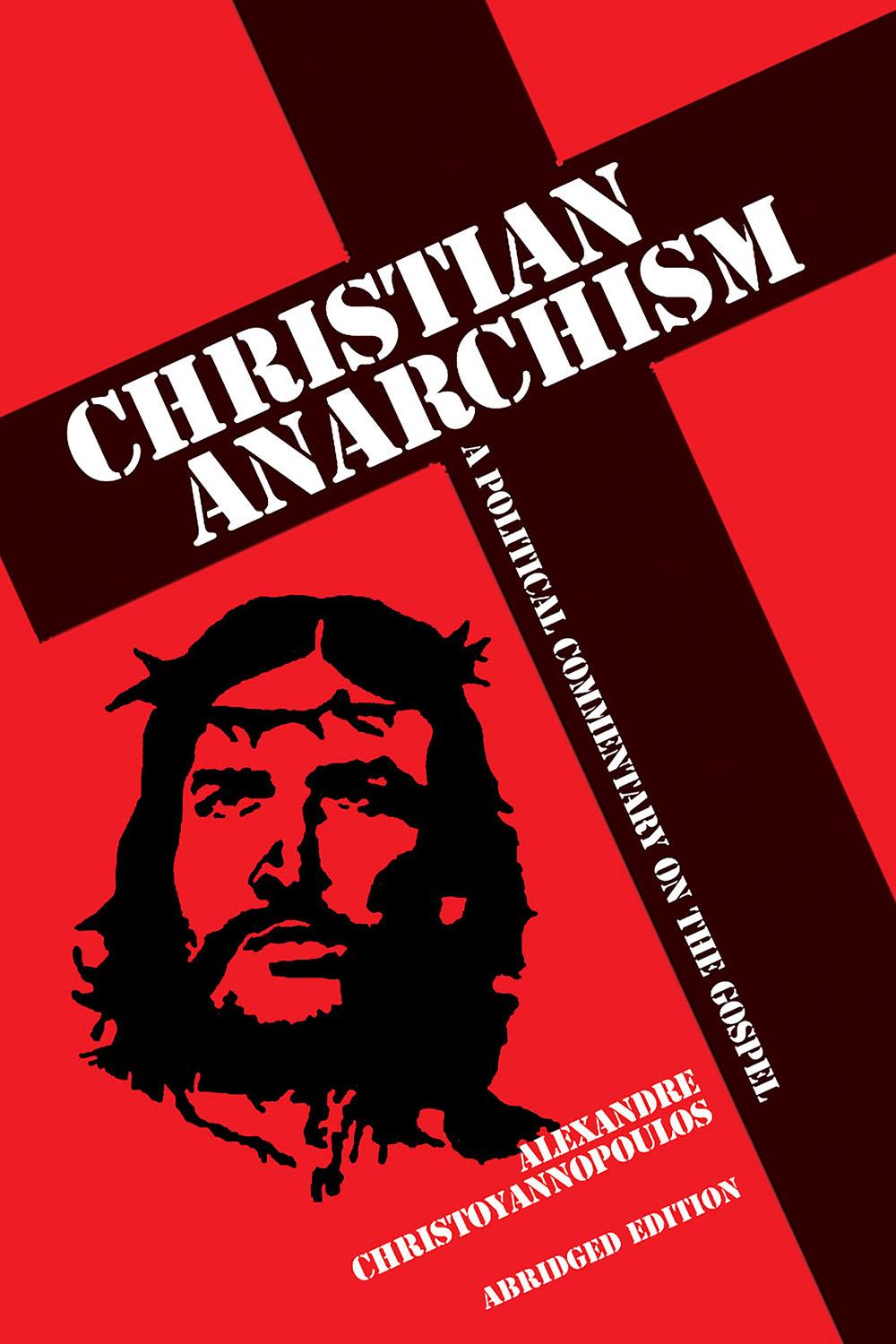

Alexandre Christoyannopoulos

Christian Anarchism

A Political Commentary on the Gospel

Introduction — Christian “Anarchism”?

Christian anarchist “thinkers”

Key writers in the Catholic Worker movement

Writers behind other Christian anarchist publications

Stephen Hancock (A Pinch of Salt)

Kenneth C. Hone (The Digger and Christian Anarchist)

Contributors to The Mormon Worker

Andy and Nekeisha Alexis-Baker (Jesus Radicals)

Bas Moreel (Religious Anarchism newsletters)

Kevin Craig (Vine and Fig Tree)

Strike the Root, Lew Rockwell and Libertarian Nation essayists

Part I — The Christian Anarchist Critique of the State

Chapter 1 — The Sermon on the Mount: A Manifesto for Christian Anarchism

1.1.1 — Jesus’ three illustrations

1.1.5 — Overcoming of the cycle of violence

1.1.6 — Anarchist implications

1.6 — Reflections on other passages in the Sermon

1.6.5 — Worry not about security

1.6.6 — Be the salt and the light

1.8 — A manifesto for Christian anarchism

Chapter 2 — The Anarchism Implied in Jesus’ Other Teachings and Example

2.1.2 — Other Old Testament passages

2.2 — Expectations of a political messiah

2.3 — Jesus’ third temptation in the wilderness

2.4 — Exorcisms and miracle healings

2.5 — Forgive seventy-seven times

2.11.2 — The defeat of the powers

2.11.3 — The crucified “messiah”

2.11.4 — The crux of Jesus’ political teaching

2.14 — Allegedly violent passages

2.15 — Jesus’ anarchist teaching and example

Chapter 3 — The State’s Wickedness and the Church’s Infidelity

3.1 — The history of Christendom

3.1.1 — Constantine’s temptation of the early church

3.1.2 — Christendom and beyond

3.2 — The modern state and economy

3.3 — Church doctrine in support of the state

3.3.1 — Reinterpretations of Jesus’ commandments in the Sermon on the Mount

3.3.2 — Reinterpretations of non-resistance

3.3.3 — Support for political authority

3.4.1 — Sanctimonious self-righteousness

3.4.2 — Obscure rituals and beliefs

3.4.3 — Institutional religion

3.5 — Awakening to true Christianity

Part II — The Christian Anarchist Response

Chapter 4 — Responding to the State

4.1 — Paul’s letter to Roman Christians, chapter 13

4.1.2 — The Christian anarchist exegesis: subversive subjection

4.1.3 — Similar passages in the New Testament

4.2.1 — Caesar’s things and God’s things

4.2.2 — The temple tax and fish episode

4.3 — Pondering the role of civil disobedience

4.3.1 — Against civil disobedience

4.3.2 — For (non-violent) civil disobedience

4.4 — Disregarding the organs of the state

4.4.1 — Holding office and voting

4.5 — On revolutionary methods

4.5.1 — No compromise with violence

Chapter 5 — Collective Witness as the True Church

5.1 — “A new society within the shell of the old”

5.1.1 — Repenting and joining the church

5.1.2 — An economy of care and sacrifice

5.1.3 — Subversive organisation

5.2.1 — Dealing with evil in the community

5.2.2 — Heroic sacrifices by church members

5.3.2 — The mysterious growth of a mustard seed

Chapter 6 — Examples of Christian Anarchist Witness

6.1.2 — The Middle Ages and the Reformation

6.2.1 — Garrison and his followers

6.2.2 — Ballou and the Hopedale community

6.2.3 — Tolstoy’s personal example

6.2.4 — Tolstoyism and Tolstoyan colonies

6.2.5 — Gandhi: a leader by example

6.2.6 — The Catholic Worker movement

6.2.7 — A Pinch of Salt and The Digger and Christian Anarchist

6.2.9 — Andrews’ community work

Conclusion — The Prophetic Role of Christian Anarchism

“Christian anarchists” and “Christian anarchism”

History’s mysterious unfolding

The temptation of normal political action

Relentless prophecy at the margins

Love, justice, and social ontology

Christian anarchists as prophets

Quotations

Christianity in its true sense puts an end to the State. It was so understood from its very beginning, and for that Christ was crucified.

— Leo Tolstoy

Where there is no love, put love and you will find love.

— St. John of the Cross

Acknowledgements

This book is the product of six years of doctoral research undertaken at the University of Kent, in Canterbury, England. Since the defence of that thesis in September 2008, the taking on of various academic duties and responsibilities have prevented me from making major revisions to the text, and therefore from integrating into it the related material which I have come across or read since. Apart from adding a few references to such material and other minor modifications, the book is not significantly different from the original thesis.

The aim of the thesis was to produce a clear and accessible synthesis of all the Christian anarchist publications I managed to come across and study during my research, as well as a comprehensive set of references to these. The aim of the original, hardback version of this book was to present both that synthesis and its references to a wider audience. This abridged, paperback version presents almost exactly the same text, but without the original version’s detailed comments and references in the footnotes — the main aim being to thereby make the book more affordable. The footnotes of the current version therefore only contain the most important comments and reference details (such as for verbatim quotations). Those who wish to study the Christian anarchist literature and its context in more depth will find the full comments and references in the hardback version. As to the main text, the only changes to it are the current paragraph, the rectification of a few typos, and the addition of two bracketed comments where the text refers to extensive footnotes only present in the original. By implication, just as with the hardback version, given that the Introduction’s function is to set the context, locate the book in the wider literature, and introduce the Christian anarchist thinkers relied on for the rest of the book, readers less interested in such preliminaries can skip these and jump straight to Chapter 1.

I would not have been able to complete my PhD without the financial support of my parents. Their love, care and patience, along with that of my (then) partner Tânia Gonçalves, provided the ideal climate for my research to take root, grow and bear fruits. My gratitude to all three of them is immense.

My doctoral work was supervised mainly by Dr Stefan Rossbach. His comments on my work were always sympathetic and helpful, and even when he took issue with Christian anarchists, his feedback was always informed by a concern for me to improve my case and hence theirs. Those he supervises are envied by those he does not, and the Department of Politics and International Relations at Kent owes a lot to him for his dedication to research students as Director of Research. I am also grateful to Dr Peter Moore and Dr Joseph Milne, whose invitation to return to Kent and to sit in numerous modules in theology and religious studies was instrumental in setting the context for me to start my PhD. They also both acted as supervisors from time to time, and especially in Joseph’s case, as friend and collaborator too. My thanks also go to my examiners, Professor David McLellan and Dr Ruth Kinna.

My work benefited from the stimulating feedback and friendship of numerous research students in politics and in religious studies. They cannot all be listed here, but deserving special mention for their impact on my doctoral work are, in the religious studies crowd, Duane Williams, David Lewin, Todd Mei, Brian Edwards and Geoffrey Cornelius, and in the politics crowd, James Schillabeer (whose careful proofreading of my thesis was of tremendous help), George Sotiropoulos, and Charles Devellennes. Fanny Forest has also been of great support in helping me convert my thesis into this book.

I have also found help and inspiration among the academic networks I have joined and the conferences they organised. These include the Anarchist Studies Network and the broader Political Science Association it belongs to, the Society for the Study of Theology, the Religion and Politics standing group of the European Consortium of Political Research, and the Research on Anarchism and Anarchist Academics mailing lists. To those networks (among others), and more to the point to their members who have helped me articulate and improve my work, I owe another big “thank you.”

Finally, I wish to thank all those activists of love and justice whose passion and commitment are an inspiration to those who are ambassadors of the same objectives within academia. This includes many anarchists, many Christians, but also many others who dedicate time and effort to the improvement of the lives of others. To them, to all of the above and to all those reading these pages, I hope that this book can convey enthusiasm and stimulate thought in the way the Christian anarchist literature did to me over the years.

Introduction — Christian “Anarchism”?

Christianity and anarchism are rarely thought to belong together. Surely, the argument goes, Christianity has produced about as hierarchic a structure as can be, and anarchism not only rejects any hierarchy but is also often fervently secular and anti-clerical. Ciaron O’Reilly warns, however, that Christian anarchism “is not an attempt to synthesise two systems of thought” that are hopelessly incompatible, but rather “a realisation that the premise of anarchism is inherent in Christianity and the message of the Gospels.”[1] For Christian anarchists, Jesus’ teaching implies a critique of the state, and an honest and consistent application of Christianity would lead to a stateless society. From this perspective, it is actually the notion of a “Christian state” that, just like “hot ice,” is a contradiction in terms, an oxymoron.[2] Christian anarchism, therefore, is not about forcing together two very different systems of thought — it is about pursuing the radical political implications of Christianity to the fullest extent.

A generic “theory” of Christian anarchism, however, has yet to be enunciated. Several writers have adopted a Christian anarchist position, and some of these writers are aware of some of the others who have come to the same position, but a detailed and comprehensive synthesis of the main themes of Christian anarchist thought has yet to be produced.[3] That is, an overall theory of Christian anarchism has yet to be outlined. The central aim of this book is to do just that — metaphorically-speaking, to weave together the different threads presented by individual Christian anarchist thinkers, to arrange into a symphony the similar melodies played by each of these theorists. In other words, this book delineates Christian anarchism by bringing together the main insights of individual Christian anarchist thinkers.

But first, such a perspective must be located in the broader literature, both in political theology and in political thought — the first task of this Introduction. This makes it possible to then spell out in more detail the main aims of this book, its originality, and its chapter structure. The more substantial part of this opening chapter then introduces each of the thinkers who contribute to this generic outline of Christian anarchism.

Locating Christian anarchism

In order to clarify what is original about Christian anarchism, it is necessary to first contextualise it in the wider literature in both politics and theology.

In political theology

The modern, Western assumption that religion and politics are best kept separate has been coming under increasing strain lately, from a variety of angles. Recent scholarship, for example, has questioned the motives and the historical origins of the claim that religion should be kept out of politics in the first place. William T. Cavanaugh in particular argues that the very “creation of religion” as a set of private and therefore apolitical beliefs “is correlative to the rise” of the modern state, in other words that the modern liberal myth of their necessary separation was a far from innocent product of the state’s successful outmanoeuvring of the church for power and legitimacy in sixteenth and seventeenth century Europe.[4] Even the typical Christian rationalisation for this separation — the “distinction of planes” interpretation of the “render unto Caesar” passage — was absent “until at least the late medieval period,” contends Cavanaugh.[5] Hence whether secular or Christian, the rationale for the separation of religion and politics has been questioned.

Moreover, a growing body of scholars has made the case for the direct and indirect political implications of Jesus’ teaching to be fully recognised. John Howard Yoder’s Politics of Jesus, for instance, is an eminent example of such scholarship.[6] His book also helpfully provides a very comprehensive set of references to the many other studies that have similarly emphasised the political nature and context of Jesus’ teaching. Partly thanks to such work, “political theology” is an increasingly popular field of study in academic circles (despite the uneasiness caused by this term’s association with Carl Schmitt).[7] Nowadays, therefore, while it is possible to disagree on whether the political side of Jesus’ teaching was the most important, it is increasingly difficult to argue that there is no such political dimension to it.

Away from the theory, in practice, scholars have also noted that there has been something of a resurgence of religion in politics in the past decades, even — if not especially — in the hitherto allegedly secularised West, which has witnessed the increasing “collective mobilisation of Christians in large numbers across a wide range of issues.”[8] Yet perhaps the most famous example of recent political engagement by Christians has come not from the West but from the “theologies of liberation” of Latin America (and beyond), where churches have mobilised to resist oppressive regimes and more recently the perceived oppression inherent in global capitalism. These and other examples demonstrate that religion continues to inform politics, despite the confident predictions of certain Enlightenment thinkers.

For Christian anarchists, however, although encouraging and in the right direction, none of these trends go far enough. For them, the conventional Christian legitimisation of the state ought to be seriously reconsidered. Jacques Ellul, for example, argues that while one of the two “tendencies” in the New Testament does seem “favorable” to the state (based “mainly” on Romans 13), the other, “more extensive” tendency which is “hostile” to it (based on the Gospels and Revelation) should also be given due attention.[9] He finds it “strange” that “the official Church since Constantine has consistently based almost its entire ‘theology of the State’ on Romans 13 and the parallel texts in Peter’s epistles.”[10] Christian anarchists are also deeply sceptical of the view that the head of state somehow acts as God’s ambassador for its population, or that the state is otherwise divinely appointed — although of course, as one of them puts it, “Those who live off the loot would be very pleased for you to believe that.”[11] They note, for instance, that “it is the state and the powers behind it that” crucified Jesus,[12] and that perhaps the poor and those who are being persecuted by the state are better candidates to the title of God’s “ambassadors” on earth.[13]

A central aim of this book is to explore the detail of such Christian anarchist criticisms of the received Christian wisdom on the state, and to thereby contribute to the wider literature in political theology. More specifically, the Christian anarchist understanding of the political implications of Jesus’ teaching and example is explained in Chapters 1 and 2; their bitter criticism of both church and state for their collusion since Constantine in Chapter 3; and their interpretation of the “render unto Caesar” passage and of Romans 13 in Chapter 4. Both Chapters 4 and 5 also describe the sort of mobilisation which Christian anarchists expect from Christians today. Each of these Chapters, therefore, has a bearing on the contemporary theological debates on the theoretical and practical political implications of Christianity.

In political thought

Aside from political theology, Christian anarchist thought also contributes to wider political thought, and in particular, obviously, to anarchist thought. Here is not the place to discuss the often misjudged association of the term “anarchism” with violent chaos and disorder. It should suffice to note that anarchism is a recognised school of political thought with a very broad range of (sometimes contradictory) voices reflecting on important political themes, such as those of freedom, power, economic justice, and the best methods to approach these. Violence, far from being universally supported among anarchists, is justified by some but also roundly rejected by many, and is thus a topic of passionate debate among anarchists to this day — a debate on which Christian anarchists have a particularly pointed contribution to make (as Chapter 1 to 3, in particular, make clear).

Christian anarchism has long been acknowledged as a peculiar variant of anarchism. For some anarchists, it is to be welcomed as another strand of the very diverse tradition that is the anarchist school of thought. For others, however, the association of Christianity and anarchism is not without potentially serious problems, for several reasons.

For a start, many classic anarchist thinkers were atheistic or at the very least agnostic, and there is certainly what Nicolas Walter describes as “a strong correlation between anarchism and atheism.”[14] Colin Ward furthermore explains that “The main varieties of anarchism are resolutely hostile to organised religion.”[15] Yet the same commentators also grant that anarchism need not necessarily be atheistic, that there even seems to be anarchist elements in Buddhism and Taoism, and of course that thinkers like Leo Tolstoy have famously made the case for a peculiarly Christian type of anarchism as well. Anarchist conclusions, therefore, do not necessarily depend on atheistic premises.

Ellul argues that anarchism’s “complaints against Christianity” usually “fall into two categories: the essentially historical and the metaphysical.”[16] The prime example of the former is the anarchist blaming of the church for colluding with the state to persecute and oppress the masses. Almost all anarchists are extremely critical of organised churches for this reason. As Chapter 3 shows, however, so are most Christian anarchists. A strong anticlericalism is therefore present in both secular and Christian anarchism, although both also note that a minority of revolutionary churches and rebellious sects also form part of the Christian legacy.

Related to this historical complaint is the one that “religions of all kind generate wars.”[17] True though this may be, the twentieth century demonstrates that secular ideologies are no less culpable of similar bloodshed. Nonetheless, Ellul accepts the accusation and comments that he has “never understood how the religion whose heart is that God is love and that we are to love our neighbours as ourselves can give rise to wars.”[18] (As Chapter 3 shows, Christian anarchists do actually have an explanation for this: they blame the deceptive manipulation of the Christian message by ruling elites.) Ellul also admits that Christianity “claims exclusive truth,” but he refuses to blame this for these wars, insisting instead that “faith cannot be forced” by war or coercion because it “has to come to birth as a free act,” otherwise “it has no meaning.”[19] Either way, the point here is that Christian anarchists like Ellul are just as critical as secular ones of the sort of Christianity that has waged wars, especially when under the pretence of converting non-Christians to the faith (see Chapters 3 and 5).

Another — this time “metaphysical” — complaint raised by anarchists against Christianity is often encapsulated by the Bakuninist motto: “no gods, no masters.”[20] Anarchism, it is claimed, necessarily implies the rejection of all masters, including therefore that greatest master of all: God. Here, Christian anarchists respond by questioning “simplistic representations of God” as an autocratic ruler.[21] Nekeisha Alexis-Baker recalls that in the Bible, “God is also identified as Creator, Liberator, Teacher, Healer, Guide, Provider, Protector and Love,” so that anarchists and Christians alike who are “making monarchical language the primary descriptor of God” in fact “misrepresent” his “full character.”[22] Ellul similarly argues that even in the Old Testament, “the first aspect of God is never that of the absolute Master,” and that human beings are always free to act or not according to his commandments (this is clarified further in Chapter 2).[23] Therefore, in response to this anarchist complaint, Christian anarchists contend that much is misunderstood about the nature of God if he is just seen as an autocratic ruler or as some sort of “Super Santa-Claus” or “Benevolent Despot,” as Hennacy puts it.[24]

Nonetheless, Christian anarchists’ anarchism does — perhaps somewhat paradoxically — derive from the authority they ascribe to God and to Jesus’ teaching in particular (this point is revisited several times in this book). It is precisely this acceptance of God’s authority that leads to their negation of all human authority. Yet most anarchists can also be said to derive their anarchism from the authority they ascribe to their understanding of freedom, for instance, or equality.[25] Whether secular or religious, therefore, the anarchist rejection of the state often follows from the priority attributed to something which is then interpreted as logically incompatible with the state. That Christian anarchists ascribe authority to God may be unusual for secular anarchists, but not that authority is ascribed (and anarchism derived therefrom) per se. Besides, as Dorothy Day reiterates in response to this anarchist complaint, the authority of God, unlike that of the state, is one which can be accepted or rejected of one’s own free will.[26] Nothing therefore precludes one from at the same time accepting the authority of God and rejecting human authority, from being both a Christian and an anarchist.

In any case, the fact remains that regardless of these various anarchist complaints about Christianity, an outline of Christian anarchism that encompasses all its main thinkers has never yet been articulated. By addressing this lacuna, this book not only clarifies the Christian anarchist contribution to political thought, but also thereby makes possible a better informed discussion on the place of religion in anarchist thought and thus in politics more generally.

While on this subject, it is worth noting in passing that there is something of a debate among Christian anarchists as to how to characterise their blending of Christianity and anarchism. Some prefer to speak of “parallels,” “overlap,” similar “general orientation” or “shared history” between Christianity and anarchism, thus seeing the two as in the end quite distinct yet also as potentially fruitful dialogue partners.[27] Others prefer to speak of Christian anarchism as the only logical political conclusion that can be derived from Christianity — one of them pointing out, for example, that he has “a problem with the term Christian anarchism [...] if it implies that there can be authentic forms of Christianity that aren’t anarchic.”[28] Hence while some prefer to speak of “Christianity and anarchism”[29] or of a “Christian+anarchist position,”[30] thus underlining their distinction, others are happy to speak of “Christianarchy”[31] or perhaps of a “Christian (anarchist)”[32] position, thus stressing the logical continuity from a Christian premise to anarchist conclusions.

No one is claiming, however, that anarchism and Christianity are the same or that they are interchangeable. They obviously each have their own heritage and tradition, and it is not unreasonable to want to make this clear while also promoting dialogue between the two. Anarchism is certainly not all there is to Christianity. The point which some describe as the overlap of the two separate traditions, however, seems to be precisely where others argue that Christianity logically leads to some form of anarchism. In other words, it is precisely where Christianity is taken to necessarily imply an anarchist critique of the state and the vision of a stateless society that these otherwise separate traditions, despite their separate beliefs and values, do share a common orientation. They are not the same, but it is where Christianity is understood to imply a form of anarchism that they share something that very much belongs to both. The aim of this book is to focus on this overlap, and therefore solely on the anarchist political implications of Christianity. That is, this book focuses on the view that Christianity implies a (peculiarly Christian) type of anarchism.

Outlining Christian anarchism

By outlining Christian anarchism, therefore, this book presents a unique contribution to both political theology and political thought. It is important, however, to be clear as to what this book covers and what it must ignore.

Aims, limits, and originality

The boundaries of this book are defined by its focus on Christian anarchist thought: because it focuses on Christian anarchist thought, this book does not examine the countless millenarian sects and movements which could be classed as Christian anarchist, but concentrates on the theoretical case for the Christian rejection of the state; because it focuses on Christian anarchism, it does not discuss other forms of religious or secular anarchism; and because it focuses on Christian anarchism, this book is not concerned with Christian pacifism, with theologies of liberation that are favourable to the state, or with any of the many more examples of Christian radicalism or alternative movements that are not explicitly anarchist.

Nonetheless, because in its politicisation of Christianity and denunciation of oppression, Christian anarchism appears so similar to other theologies of liberation, key differences between the two are noted when doing so clarifies the originality of Christian anarchism (especially in Chapters 2 and 4, and in the Conclusion).[33] Christian pacifism also shares a lot with Christian anarchism (just like secular pacifism with anarchism), but their differences become obvious especially in Chapters 1 and 2. Crucial differences with secular anarchism are also noted where relevant, particularly in Chapter 4. Also, despite the explicit focus on thought, individual and communal examples of Christian anarchist practice are also listed in this book (in Chapter 6), but only because Christian anarchist thinkers themselves frequently refer to these movements as illustrations of their thought.

Many more overlaps and similarities can be found between Christian anarchist thought and many other themes, writers and traditions which sit just outside its boundaries. There are even many instances where Christian anarchist thought is not dissimilar in its exegesis to orthodox Christian theology. Very few such similarities are noted in this book, however, because without such tight focus on Christian anarchist thought, the path would be open for seemingly endless noting of, and referencing to, analogous lines of thinking outside Christian anarchist thought. Hence while the reader will most probably find parallels here or there between what is being said and this or that famous or less famous theory or perspective, these parallels are not drawn out in this book. The fleshing out of many such parallels and the potential dialogue between Christian anarchism and thinkers in other traditions must therefore remain subjects for future study.

The main aim of this book is to articulate a generic outline of Christian anarchism. To do so, it relies almost completely on the existing writings of individual Christian anarchist thinkers, quoting them extensively in the process. In a sense, therefore, the thought that this book conveys outline is not novel or original. Yet these different Christian anarchist voices have never been synthesised or combined before into a comprehensive and overarching outline of Christian anarchism. They are similar and complementary, but they have never yet been made to speak together as one. In a way, Christian anarchism as a school of thought is both assumed and proposed by this book. It is presented as if it already exists as a tradition, but doing so also thereby constitutes it as a tradition at the same time. The originality of this book lies in this presentation of Christian anarchism as a coherent perspective, in this weaving together of separate Christian anarchists into what thereby begins to resemble a school of thought.

In any school of thought, of course, there are also disagreements. Different thinkers come from different angles, and sometimes these differences can lead to major controversies. Such open rows have been largely absent in the Christian anarchist literature, presumably in large part because its thinkers have yet to consider themselves as part of such a varied school of thought, in dialogue with others within it. Still, there are certainly important variations and potentially serious tensions between Christian anarchists on some issues. To list but three examples: Tolstoy’s rationalistic approach to Christianity sits uncomfortably with Day’s faith in the Sacraments; Christian anarcho-capitalists’ take on private property is diametrically opposed to that of most other Christian anarchists (thus mirroring the comparable contrast in secular anarchism); and there also seem to be potentially serious disagreements between Vernard Eller’s emphasis on Romans 13 and the stance taken by many Christian anarchist activists. This book, however, concentrates on the similarities, on the general coherence of the main line of thought presented by all those thinkers when taken together. Their differences are noted in passing where appropriate, and in some cases (especially that of the last example), they are discussed in some detail. The emphasis, however, is on the general coherence. Exploring the tensions remains another task for further research.

While every effort has been made to include all the relevant literature into this generic outline of Christian anarchism, there is always room for more. This book intends to be as comprehensive as possible in its coverage of Christian anarchist thinkers and certainly in its thematic breakdown of Christian anarchism as a generic theoretical perspective, but it does not claim to be the final word on the topic. It is hoped that future scholarship can add more voices to this book, especially thinkers prior to the nineteenth century — and perhaps the best candidate for possible future inclusion is Gerrard Winstanley.[34] With the exception of Peter Chelčický (explained below), such pre-nineteenth century thinkers have been excluded here in part because the modern state had not risen to its full industrial power yet (and anarchism as an explicit position had not yet been articulated in response to it), but also mainly and simply because including these thinkers would have required several more years of research.[35] Nevertheless, although some of these thinkers would no doubt enrich the outline of Christian anarchism presented here, they would probably not radically upset the thematic breakdown of this book. To refer to a previous analogy, their distinct melodies would most probably fit the symphony rather than force a major rewrite of it.

Also ignored in this book are any criticisms which could be mounted against Christian anarchism in general or Christian anarchist exegesis in particular. Since a generic and comprehensive outline of Christian anarchism has never been produced before, this book focuses on doing just that — a task which on its own makes this a long enough manuscript. It is therefore necessarily one-sided: it takes the Christian anarchist perspective and makes a detailed case for it by collating the contributions of individual Christian anarchist thinkers. Some reflections on Christian anarchism are offered in the Conclusion, but most of the critical and reflective input has gone into drawing out the overall coherence of the many Christian anarchist voices, methodically weaving them together, and presenting Christian anarchism as a coherent perspective rather than critiquing it. To paraphrase Darrell J. Fasching, with this book, “I do not so much attempt to stand outside of [Christian anarchism] and judge it as to get inside it and clarify it.”[36] The aim has been to give a fair hearing to the numerous sets of arguments presented by Christian anarchism, to let Christian anarchists speak rather than to mount criticisms at every turn. Such criticisms must therefore remain yet another topic of further research, but such research will now be able to build upon the synthesising work of this book.

Therefore, this book can act as a first important step towards a better understanding of Christian anarchism in political theology and political thought. Moreover, it also opens up areas of potential dialogue for instance with other trends in anarchism, with pacifist thinking, with liberation theology, and in general with the growing literature on religion and politics. It provides a unique perspective to Christians pondering how their faith is to inform their politics. It might also be of interest to non-Christians who are curious about the political dimension of what continues to be one of the world’s most widespread religions. Obviously, it also makes available to Christian anarchist activists and similar Christian radicals a fairly comprehensive summary that weaves together many of the thinkers they might have read so far on the topic. Indeed, it will also be relevant to those who have studied other aspects of some of these thinkers, by clarifying that side of their thinking. This is especially the case for Tolstoy, whose Christian anarchism is rarely given serious academic attention. In synthesising Christian anarchism and presenting it as a tradition, therefore, this book is — I hope — potentially relevant to a wide range of (academic and lay) thinkers, Christians, and activists.

Technical issues

At this stage, a few technical points on the referencing, language and Biblical approach of this book are in order.

On referencing, given that one of the intentions behind this book is to present a source for references on Christian anarchism, extensive use of footnotes is made, either to point to the original Christian anarchist source where an assertion that is made in the text can be found or explained, or to provide more detail on a point when providing this detail in the text would be tangential to the main line of argument (however, as explained in the Acknowledgements, these very extensive footnotes have here been trimmed down to the bare minimum, so readers interested in such references and tangential discussion points will find these in the original, hardback version of this book).[37] Footnotes for quotations always point to original page numbers, except for internet pages for which the precise paragraph where the quote can be found is numbered.[38]

On language, no definitions of the words “state,” “government,” “power” or “authority” are presented in this book. This is mainly because Christian anarchists do not all refer to them in exactly the same way, and since extensive use of quotations is made throughout the book, any strict definition would regularly need to be qualified to reflect the slightly different meaning attributed by different Christian anarchists. A fairly clear sense of what is being criticised by Christian anarchists does nevertheless emerge in the first t hree Chapters anyway, and Chapter 3 does briefly revisit this question of the terminology employed by Christian anarchists.

The words “non-violence,” “non-resistance” and “pacifism” are also not defined in this book, again because individual Christian anarchists can sometimes have slightly different meanings in mind when using them. Nonetheless, a tension between the first two words, and specifically between the different understandings of Jesus’ teaching which their choice betrays, becomes evident by Chapter 4, where it is discussed in more detail.

Another key word for which a definition is avoided is the word “church,” because usually, what is being said in the text about the existing church refers not to one particular church or denomination but to almost all churches in Christianity, to the Christian church generically-speaking.[39] A clearer picture of what it is about the existing church that Christian anarchists dislike is drawn in Chapter 3, and Chapter 5 portrays the “true,” ideal church or community which they understand Jesus’ teaching to have implied.

While on language, it is worth confessing that the language of several of the quotations in this book is clearly male-centric, especially from authors who wrote prior to the feminist revolution. Although it is impossible to assert with certainty whether these authors meant their words to apply to both genders, it goes without saying that in quoting their words in this book, my intentions are for these to be interpreted as applying to all, in a gender-neutral way.

Another somewhat outdated form of vocabulary present in the book appears through the choice of the King James Version for all Bible quotations.[40] This is because the English translations of Tolstoy and Chelčický all opt for this version, as does Adin Ballou in his own writings, and the book contains many quotations from these authors which deliberately hint at Bible passages using the wording of the King James Version.

With regards to the Bible, this book pays no attention to the important debates in Biblical scholarship on the relative authenticity of different sections of it. The four Gospels are taken at face value, assumed to be valid accounts of the life and teaching of Jesus.[41] The aim here (in line with that of Christian anarchists) is to make the case for an anarchist understanding of the political implications of these Gospels as they stand, not to engage in debate over their reliability.

Not all Christian anarchists agree on the value of other parts of the New Testament, but this is noted where relevant. The Old Testament is mostly ignored, partly because the New Testament is traditionally understood to fulfil it, but mainly simply because Christian anarchists generally have very little to say about it.[42]

Some Christian anarchists take very different views on theological dogma derived from the Bible. Those differences that are relevant to Christian anarchism are noted, but those that are not are ignored.[43] Likewise, where the different hermeneutical methods adopted by Christian anarchists have a bearing on their political commentary of a passage, this is noted, but otherwise these differences are ignored.

It will become clear that most Christian anarchists approach the Bible with a modern mindset, interpreting its commandments as fairly literal propositions and frequently paying little attention — in their political exegesis at least — to any layers of meaning beyond the merely literal and political.[44] For reasons made clear in Chapter 3, in typically protestant (“sola scriptura”) fashion, they bypass traditional exegesis and rely only on scripture for their understanding of Jesus’ teaching.[45] This hermeneutic approach is of course questionable, but such questioning would take this book beyond its immediate remit. The limited aim of this book is to weave together the different interpretative threads of Christian anarchist thinkers, not to evaluate the soundness of their hermeneutic methods.[46]

The structure of this book

The main body of the book consists of six Chapters, split into two main Parts. Part I describes the Christian anarchist critique of the state, and Part II, the Christian anarchist response.

Chapters 1 and 2 focus on the Christian anarchist exegesis of key Bible passages, on the interpretation of these passages as implying a rejection of the state. Chapter 1 singles out the Sermon on the Mount because of the central importance accorded to it by Christian anarchists, and Chapter 2 turns to other Bible passages, mostly from the four Gospels but also from other books in both the Old and New Testaments. By contrast to these two exegetical Chapters, Chapter 3 focuses on the state and church in practice, outlining the Christian anarchist critique of both institutions for their perceived collusion in deceiving and oppressing the masses.

Part II then considers the Christian anarchist response to the state’s contemporary prominence. Chapter 4 discusses the direct Christian anarchist response to the state and the potential for some degree of civil disobedience, examining Romans 13 and the “render unto Caesar” passage in the process. Chapter 5 describes the other side of the response: the example to be set by the “true” church, by this alternative community witnessing to the truth of the Christian teaching. In a sense, whereas Chapter 4 outlines the negative response to the state, Chapter 5 outlines the positive response as the “true” church. Chapter 6 then lists the examples of individual and collective witness which are either praised or inspired directly by Christian anarchist thinkers — examples, therefore, of the Christian anarchist response.

In the Conclusion, some reflections are offered on the name and defining characteristic of Christian anarchism, on the Christian anarchist understanding of history, and on the original and perhaps “prophetic” role played by Christian anarchism in its unfolding.

Christian anarchist “thinkers”

There remains to introduce the main protagonists of Christian anarchist thought, the separate threads that this book weaves together into a generic outline of Christian anarchism. What qualifies this diverse range of thinkers as “Christian anarchists” is specified in each case below, but on a general note, each of these “Christian anarchists” (as they are often hereafter referred to) have something to contribute to the perspective that Christianity logically implies a form of anarchism, that anarchism logically follows from Christianity — the defining characteristic of Christian anarchism. These thinkers have either written openly about something they describe as Christian anarchism, are widely described by others as Christian anarchists, or have something to say which helps strengthen the case for Christian anarchism. What is of interest here is not their particular life or social context, or even how solid a commitment they might have made to Christian anarchism, but that at the level of ideas, they contribute to a generic outline of Christian anarchism. That their writings on this particular issue combine to produce a fairly coherent body of thought is both assumed and demonstrated by the remainder of this book.[47]

Leo Tolstoy

Russian aristocrat Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910) is of course one of the world’s most acclaimed authors of literature, but he is also by far the most frequently cited example of this peculiarly Christian form of anarchism that is the subject of this book. His Christian anarchism was an outcome of an intensive existential quest for the meaning of life, a quest which ended only once he converted to his idiosyncratic understanding of Christianity around 1879. There is much debate as to whether this conversion should be seen as a clear rupture in his thinking (as he himself certainly liked to portray it) or a natural continuation of his lifelong intellectual pursuits. As Stepun remarks, however, whether or not Tolstoy’s life and thought should be divided into two parts, his fame is certainly twofold: as an artist and as a “social prophet.”[48] It is only as a social prophet that his legacy is of direct relevance to this book.[49] Besides, it is clear that by the turn of the century, Tolstoy himself considered his views as a thinker to matter more than his artistic prowess: “Like a clown at a country fair grimacing in front of the ticket-booth in order to lure the public inside the tent where the real play is being performed,” Tolstoy comments, “so my imaginative work must serve to attract the attention of the public to my philosophic teaching.”[50]

Tolstoy’s understanding of Christianity was peculiar indeed, although it very much reflected the nineteenth century context in which he lived. For him, Jesus was simply the most rational human being ever to walk the planet, not some supernatural figure that actually flew back into the sky. As Chapter 3 explains in more detail, Tolstoy distrusted all such miraculous elements in both the Bible and the wider Christian tradition — he called them the “rotten apples” of Christianity.[51] What mattered in the Christian message, for him, was only the revolutionary but (for Tolstoy) eminently rational teaching and example of Jesus, which he saw as best summarised in the Sermon on the Mount. He brushed aside the tradition, and studied the Bible very closely — indeed even rewriting a harmonised version of the Gospel purged from supernatural distractions. For him, the essence of Christianity was to be found in the moral principles articulated by Jesus.

His rationalistic take on Christianity is rarely shared by other Christian anarchists, but it is not necessary to agree with his dislike of the supernatural to be able to follow his powerful arguments on Jesus’ teaching and example. It was the development of these arguments that led him to become such a bitter critic of church and state. That is, as Chapter 1 makes clear, Tolstoy’s Christian anarchism follows from his rationalistic interpretation of Jesus’ teaching, especially as summarised in the Sermon on the Mount. He wrote countless essays and books on the topic, but the most often cited one among anarchists is The Kingdom of God Is within You (although What I Believe is just as good and comprehensive).[52]

In the academic literature on anarchism, Tolstoy is usually credited with having made the most detailed case for Christian anarchism, if he is not even described as the only known example of Christian anarchism. He is also often recognised as one of the classic thinkers of the broad anarchist pantheon. Like several of these classic thinkers, however, Tolstoy himself avoided the word “anarchism” to describe his thought, because he associated the word with the violent revolutionaries which he strongly disagreed with. His understanding of anarchism as an intellectual position improved over time, however, and he eventually accepted this term to describe his position as long as it was understood that his anarchism was strictly non-violent and based on the Sermon on the Mount.

Among Christian anarchists, Tolstoy is also generally acknowledged as the best known Christian anarchist thinker. Several Christian anarchists refer to him or quote him, and many more seem to suggest that they are familiar with his writings even though they might choose not to engage with these in any detail. It may be that Tolstoy’s extreme rationalism had deterred several Christian anarchists from such a more thorough engagement with him. Again, however, one need not agree with Tolstoy on this to be able to follow his Christian anarchist line of reasoning. In any case, further investigation into Christian anarchism quickly reveals that there are actually quite a few other thinkers who have developed a similar position, and most of them approach Christianity in much less rigidly rationalistic a way than Tolstoy.

Jacques Ellul

Perhaps the most important of these other Christian anarchist thinkers is French scholar Jacques Ellul (1912–1994). Ellul is known today mostly for his critical work on technology and the technological society, of which the modern state is just another symptom. He wrote extensively, usually covering each given topic from both a theological and a sociological perspective, clearly distinguishing the two approaches.[53] Comparatively few of his writings, however, are targeted specifically at the state itself. The most directly relevant for this book is his Anarchy and Christianity, but several other books of his are also relied upon where appropriate.

Unlike Tolstoy, Ellul happily employed the word “anarchism” as a thoughtful political position to hold, and certainly demonstrated his familiarity with thinkers like Bakunin, Proudhon and Kropotkin. At times, he even suggests an awareness of Christian anarchist thinkers. He himself maintained that he did not believe a true anarchist society could ever come about, but he just as adamantly insisted that “the anarchist position [is] the only acceptable stance in the modern world.”[54] For him, even though “the realizing” of “an anarchist society” is “impossible,” the “anarchist fight,” the “struggle” for such a society is nonetheless “essential.”[55] This ambivalence is explained further below in the book.

What Ellul adds to Tolstoy is his anarchist exegesis of many more passages from the Bible, including the Old Testament. His work therefore complements Tolstoy’s narrower focus on the Sermon on the Mount. Besides, Ellul’s approach to Christianity was not as unusual as Tolstoy’s, being grounded instead in traditional Protestant (especially Calvinist) theology. His approach may therefore be more comfortable than Tolstoy’s for Christians who belong to that tradition. Ellul’s contribution to Christian anarchist thought is therefore an important one. His work is certainly praised by several other Christian anarchists.

Vernard Eller

One author who makes clear his appreciation of Ellul is American academic Vernard Eller (1927–2007), author of a book published around the same time as Ellul’s and titled Christian Anarchy. In that book, he repeatedly associates himself with the Christian anarchist position which he elaborates. His own Christian background is that of the Anabaptist/Brethren tradition — again therefore a position which some Christians might find more sensible than Tolstoy’s.

His contribution to Christian anarchism, however, is somewhat contentious. Because of the submissive response which he advocates to the state, those Christian anarchists who are inclined to more confrontational activism have been very critical of Eller’s views. Yet Eller’s input is valuable precisely for his exegesis of Romans 13 and the “render unto Caesar” passage, on which his advocacy of such submission (which he sees as subversive in a peculiar way, as explained in Chapter 4) is based. The disagreement between him and such activists on how to respond to the state touches on a topic important enough to constitute the main theme of Chapter 4, so it will not be resolved here. What should be noted here is only that Eller certainly considers himself as a Christian anarchist, and that his book has evidently been noticed by other Christian anarchists. His contribution is therefore very relevant to this book, and he cannot be excluded from the Christian anarchist school of thought even if some in that school find his presence disconcerting. If anything, such disagreements only make for potentially interesting debates within such schools.

Michael C. Elliott

Another important contribution to Christian anarchist thought comes from Michael C. Elliott’s Freedom, Justice and Christian Counter-Culture — a book for which “Christianarchy” was at some point contemplated as an alternative title.[56] In that book, Elliott provides an anarchist interpretation of a number of Biblical passages, reinforcing therefore the input of the Christian anarchist thinkers mentioned above. Indeed, that book acts as an excellent introduction to Christian anarchism.

By contrast to this book, however, Elliott’s book does not attempt to weave together the different lines of thinking articulated by Christian anarchist thinkers. It reads more as a call for Christians to embody this Christian “counter-culture,” introducing them to communist and anarchist thinking and drawing parallels with Jesus’ teaching and example as narrated in the Bible. Elliott himself seems to have studied a number of other Christian anarchist thinkers, but aside from the odd reference, they do not figure much in that book. Also, perhaps as a result of the absence of the word “anarchism” in the title, it seems not to have been noticed by many Christian anarchists to this day. Nevertheless, Elliott’s contribution to Christian anarchist thought is important, both as an introduction to the topic and through his reflections on several key passages in the Bible.

Dave Andrews

Australian thinker Dave Andrews (born 1951) did name one his books by the title which Elliott briefly considered: Christi-Anarchy. Like Elliott, he seems to be aware of many of the key Christian anarchist thinkers, though also like Elliott, he does not discuss them in any detail.

Andrews’ writings are more pragmatic than those penned by most Christian anarchist thinkers. He repeatedly encourages Christians to reflect on some of the most challenging political passages in the Gospels and, crucially, to act upon them in their own community, to put Jesus’ teaching to practice. His books and essays therefore blend reflections on Gospel passages with a considerable number of moving examples of community life and personal sacrifice which illustrate the politically revolutionary potential of Jesus’ teaching when taken literally. He also often refers to work which he has been involved with in his own community in Brisbane.

His input into Christian anarchist thought thus comes both from his reflections on various Bible passages and from the many moving examples which he uses to illustrate these. Given that his writings are very recent, he is not cited by the many Christian anarchists who lived and published on the topic long before him. His work does however clearly belong to the Christian anarchist school of thought.

Key writers in the Catholic Worker movement

The Catholic Worker movement, which is still mostly based in the United States, is by definition a movement rather than just a group of thinkers. As with most movements, however, it was founded by visionaries who committed their vision into writing, not least, of course, in the newspaper after which it is named and which is at the heart of the Catholic Worker community. First published in 1933 (and sold ever since at the price of one cent), this newspaper has multiplied into many local versions of the Catholic Worker, each published by local communities brought together by the ideas of its founders. Although the majority of the columns of these newspapers do not amount to systematic and scholarly publications on Christian anarchism, they do nonetheless sometimes touch on more theoretical issues and thus contribute to a generic outline of Christian anarchism. Moreover, as Chapter 6 explains, Catholic Worker communities provide moving illustrations of Christian anarchism put to practice.

That the paper is explicitly Catholic does not mean that its members are not sometimes very critical of the Catholic Church, or that they have all vowed to abide by the will of the Pope. Instead, it reflects the respect and awe of many Catholic Workers for many of the traditional Catholic mysteries, dogmas and rituals, and for the work of several of the Catholic Church’s famous theologians. Catholic Workers also point to the many examples of loving witness and community life which are also part of the Catholic legacy as a counter-side to its darker side, which they nevertheless openly acknowledge.

From the beginning, Catholic Workers happily described themselves as anarchists — although sometimes preferring the terms “personalist” or “libertarian” so as not to arouse misunderstanding and confusion. The Catholic Worker movement is certainly recognised as Christian anarchist by both secular and Christian anarchists.[57] Both its key writers and its many contributors to newspaper columns therefore contribute, each in their own way, to the generic outline of Christian anarchism presented by this book.

Dorothy Day

One of the two main founders of the movement is Dorothy Day (1897–1980), who by the time of her death had, according to Ellsberg, “achieved iconic status as the ‘radical conscience’ of the Catholic church in America.”[58] In her autobiography, she explains how she was always concerned about social injustice and quickly found herself frequenting socialist and anarchist circles, including the Industrial Workers of the World.[59] She studied anarchist thinkers such as Kropotkin, Ferrer, Godwin, Proudhon and Tolstoy — though her praise for the latter was usually confined to his fictional work, with its emphasis on peasant life and hard manual labour. Prayer was always important in Day’s life, and she eventually joined the Catholic Church, drawn not only by its liturgy but also by its late nineteenth century social teaching and by the exemplary life of some of its more radical saints (see Chapter 6).

Day saw no problem in combining her Catholicism with her anarchism. She was a keen activist and ended up behind bars several times. She wrote countless columns in the Catholic Worker, as well as an inspiring autobiography. Her direct contribution to Christian anarchist thought is perhaps not the most significant, but some of her reflections on social issues and Bible passages are certainly pertinent enough to Christian anarchism for some of her views to be weaved into this book. Along with the Catholic Worker movement, she is often cited by several other Christian anarchists.[60] She is also loved and venerated as a mother by most Catholic Workers, and indeed even being considered for possible canonisation by the Catholic Church.

Peter Maurin

The other main founder of the Catholic Worker movement is Frenchman Peter Maurin (1877–1949), who quickly became Day’s partner, lover and “master.”[61] Maurin saw himself as a thinker, expressing his thought in scores of short “easy essays” which he saw the Catholic Worker as an essential vehicle for. His intellectual influences ranged from Aquinas to Kropotkin, including Bloy, Berdyaev, Mounier and a number of papal encyclicals. Obituaries reporting his death appeared both in papers from the Industrial Workers of the World and in Osservatore Romano (the official Vatican paper) — a reflection of his status as both an important Catholic and a notable voice of the revolutionary Left.

Maurin advocated a revolution based on roundtable discussions, houses of hospitality and farming communes (as explained in more detail in Chapter 6). Like Day, he happily described himself as an anarchist, but preferred the term “personalist” because it tied him to a particular trend in Catholic thinking which he saw as the Catholic variant of anarchism. He is therefore recognised by other Christian anarchists as one of them, and as the other founder of perhaps the most famous modern Christian anarchist movement. As with many Catholic Workers, however, his input into the present outline of Christian anarchist thought is relatively minor, although some of his passing reflections are indeed quite pertinent at times.

Ammon Hennacy

The third main figure of the Catholic Worker movement is American campaigner Ammon Hennacy (1893–1970). Unlike Day and Maurin, however, his allegiance to the Catholic Church wavered, as demonstrated by the change of title of his book from The Autobiography of a Catholic Anarchist to The Book of Ammon. His Christian anarchism was always Tolstoyan at heart: he concurred with Tolstoy, in particular his focus on the Sermon on the Mount, his suspicious hermeneutics and his distrust of institutional churches. Hennacy later explained his temporary conversion to Catholicism as motivated mostly by his love and admiration for Day, and once he recanted from it, he resumed his fierce criticism of all churches. Despite this, he is widely regarded as an influential figure in the Catholic Worker movement, and certainly as an important Christian anarchist.

Hennacy was very much an activist, and (as Chapter 4 shows) has been credited with steering the Catholic Worker movement towards more confrontational forms of Christian anarchist activism. His main contribution to Christian anarchist thought comes from numerous passing comments and reflections which he spelt out in his lengthy autobiography. Like Andrews, he also offered a short definition of Christian anarchism — definition which he repeatedly and wholeheartedly identified with.[62] His book also demonstrates his knowledge of anarchist thinkers such as Berkman (whom he met in prison), Goldman, Malatesta, Kropotkin, Proudhon, Godwin, Bakunin, and — above all — Tolstoy. There is no doubt, therefore, that Hennacy belongs firmly to the Christian anarchist tradition.

Ciaron O’Reilly

An equally active but present-day Catholic Worker activist is Ciaron O’Reilly (born 1960), who has been engaged in various recent protests, acts of civil disobedience and trials in England, Ireland, and his native Australia. He often refers to fellow Catholic Workers in his writings, but also to some of the thinkers whose writings help support Christian anarchist thought and who are introduced further below (namely: Yoder, Wink and Myers). His work has been noticed and cited by other secular and Christian anarchists, and some of it is indeed also relevant to the present book.[63] Like other Catholic Workers, therefore, he figures in this book partly thanks to some of his reflections on Christian anarchism, and partly for his example in putting these reflection to practice, as described in Chapter 6.

Writers behind other Christian anarchist publications

Apart from the Catholic Worker and its contributors, several other regular Christian anarchist publications have provided useful input into this book.

Stephen Hancock (A Pinch of Salt)

One such publication was A Pinch of Salt, fourteen issues of which were published in England in the late 1980s. 800 to 1000 copies of the paper were usually printed and then mailed out and distributed across the island and beyond. Admired by British Christian anarchists, it has very recently been revived under new editorship (see Chapter 6).[64]

The original paper was started by a group of people, but Stephen Hancock quickly became its main editor. Aside from humorous and thoughtful reflections from Hancock, the paper reprinted a variety of articles, letters from readers and other contributions sent to it on a number of topics dear to Christian anarchism (again, see Chapter 6 for more detail).

The paper proudly portrayed itself as an anarchist journal and included references to a range of secular anarchists such as Malatesta, Proudhon, Bakunin, Kropotkin, Guérin and Ward. It also often reported on liberation theology and (especially) on the Ploughshares movement, and it frequently referred to the writings of other Christian anarchists, including Chelčický, Tolstoy, Ellul, Eller and all the Catholic Workers introduced above, several of the supportive thinkers introduced below (namely: Ballou, Yoder, Wink), and many of the pre-modern examples of forerunners of Christian anarchism listed in Chapter 6.

In other words, the paper clearly embedded itself in the Christian anarchist tradition. Its columns varied widely in style, but several of these have certainly provided useful contributions or corroborations to the present outline of Christian anarchism.

Kenneth C. Hone (The Digger and Christian Anarchist)

Around the same time in Canada, Kenneth C. Hone was publishing a Christian anarchist paper eventually called The Digger and Christian Anarchist. It ran to a total of 36 issues, but the paper’s style was less rigorous, less colourful and less humorous than Pinch — which is perhaps why it usually printed only around 150 copies. The editors of the two papers corresponded, met and sometimes reprinted one another’s articles, but compared to Pinch, The Digger’s articles tend to read as somewhat undigested and casual at times. Whereas Pinch brought together and reprinted contributions from a substantial number of people, The Digger was more of a personal journal for Hone’s reflections. Nevertheless, just like Pinch, it frequently referred to anarchist thinkers. From the Christian anarchist literature, The Digger included references to Chelčický, Tolstoy, Berdyaev, Catholic Workers, as well as to some of the pre-modern examples described in Chapter 6 — Winstanley in particular. Like Pinch, therefore, it clearly rooted itself in the Christian anarchist tradition, and like Pinch, some of its columns have provided sometimes helpful input into this book.

Contributors to The Mormon Worker

Very recently, a newspaper which openly purports to provide a Mormon version of the Catholic Worker has been launched. Although The Mormon Worker is too young to be cited by other Christian anarchists, its columns praise several of the thinkers introduced here and thereby explicitly locate the paper in the Christian anarchist tradition. Some of the articles which appear in the issues published to date are very well written, and are therefore cited where relevant in this book.

Andy and Nekeisha Alexis-Baker (Jesus Radicals)

A vibrant, mostly American Christian anarchist online community has gathered under the auspices of the Jesus Radicals website, the prime movers behind which seem to be Andy and Nekeisha Alexis-Baker. A section of the website contains short essays by its members, some of which have been useful for this book. The website also hosts a discussion forum and includes videos and links to other texts and websites. Jesus Radicals cells have already organised several annual conferences in the United States, the United Kingdom and in the South Pacific. Christian anarchist thinkers cited at these conferences (recordings for which are usually made available through the website) or in the Jesus Radicals essays, or otherwise recommended as further reading on their website, include the main Catholic Workers introduced above, Ellul (who the Jesus Radicals seem to hold in particularly high regard), Tolstoy, Eller, Andrews, Cavanaugh and Yoder (the last two are introduced below). Hence the Jesus Radicals provide a series of online and offline fora for the discussion of Christian anarchist ideas, and some of their online publications are certainly meticulous and original enough to have been weaved into this book.

Bas Moreel (Religious Anarchism newsletters)

A final regular publication worth mentioning here is the Religious Anarchism newsletter published online by Dutchman Bas Moreel, three issues of which so far have discussed Christian anarchism. Moreel started these newsletters in reaction to what he saw as the poor treatment of religion in anarchist and atheist papers. The newsletters themselves are usually quite basic, concerned mostly with giving a taster to the uninformed reader of the religious anarchism chosen for the given newsletter. Still, some of them have been helpful in the present outline of Christian anarchism.

William Lloyd Garrison

All the thinkers and publications mentioned so far are undeniably rooted in the Christian anarchist tradition. Several other thinkers, however, have also published material that has been described as Christian anarchist, even if for some reason or other their identification with the Christian anarchist tradition is not always straightforward or unproblematic.

One such writer is William Lloyd Garrison (1805–1879), one of the most famous champions of the abolition of slavery in the United States. What makes him slightly problematic is that his full commitment to Christian anarchism only lasted for a few years, when he drifted away from his otherwise fairly tight focus on slavery and towards a more general critique of all government. He later recanted from such anarchism, indeed whipping up support for the Civil War and campaigning for specific Presidential candidates. Garrison was always an agitator, concerned more often with agitating as such rather than with intellectual consistency. Nonetheless, he drafted, during his Christian anarchist phase, one of the most passionate summaries of Christian anarchism, a declaration which Tolstoy later reprinted in The Kingdom of God Is within You.[65] For that declaration and for his brief Christian anarchist phase, he is included in this book — but outside from that period, he was certainly no Christian anarchist.

Hugh O. Pentecost

American pastor Hugh O. Pentecost (1848–1907) is similar to Garrison in promoting Christian anarchism only for a few years. Unlike Garrison, however, he explicitly used the word “anarchism,” and was at pains to separate the term and its advocates from popular misconceptions about it. Where Garrison preached through his newspaper columns, Pentecost preached through sermons to his congregation (he had studied to become a Baptist priest but went on to set up his own congregation). Like Garrison, however, he later renounced and even dismissed his Christian anarchist phase, and found work as a District Attorney. He does not seem to have been noticed by any other Christian anarchist, but some of the sermons which he preached during his anarchist phase are cited in this book when relevant to Christian anarchism.

Nicolas Berdyaev

Russian philosopher Nicolas Berdyaev (1874–1948) is sometimes quoted as a Christian anarchist. He rejected this association, however, and deliberately distanced himself from Tolstoy’s thought, which he was familiar with. Yet his critique of (especially Marxist) socialism and his references to Christian theology do resonate with Christian anarchism. His writings are much more abstract than other Christian anarchists’, relying more on Christian dogma than Biblical passages and criticising what he saw as dangerous monist and collectivist philosophies. His The Realm of the Spirit and the Realm of Caesar condemns socialism for such monism and advocates a Proudhonian type of world federalism. He may have had reservations about his association with anarchism, but his Christian philosophy does openly criticise statist tendencies. Besides, he did accept that the kingdom of God which he longed for could “only be envisaged in terms of anarchism.”[66] Therefore, although he was uneasy with the term and quite abstract in his thinking, some of his writings do resonate strongly with and indeed enhance the Christian anarchist position, and where this is so, this is noted and incorporated into this book.

William T. Cavanaugh

William T. Cavanaugh is a contemporary Catholic American theologian belonging to the school of thought known as Radical Orthodoxy. He is critical of the state’s violent and jealous expropriation of power and authority from the church and speaks of the eucharistic church as an alternative to the state. He argues that the Eucharist is “a key practice for Christian anarchism” in the necessary challenging, by Christians, of the “false order of the state.”[67] He rarely refers to other Christian anarchists in his writings, but his work is recommended by the Jesus Radicals. Cross-referencing between Cavanaugh and other Christian anarchists is therefore minimal, but his ongoing work on the questionable origins of the secular state and on how Christians ought to respond to the state’s assumed omnipotence is relevant to a generic outline of Christian anarchism, hence his inclusion here.

Jonathan Bartley

In Britain, Christian campaigner Jonathan Bartley (born 1971) recently published a book whose subtitle is The Church as a Movement for Anarchy.[68] The book, however, is less concerned with Christian anarchist thought than with encouraging Christian churches to dissociate themselves from the state and embrace more bottom-up methods and structures of campaigning and organisation. Bartley does mention Tolstoy, Ellul, Eller, Wink, Yoder and Myers, and he looks forward to a stateless society, but he offers little detailed theoretical thinking (in the sense of making the case that Christianity logically implies anarchism) of his own. His book thus acts more as a popular and pragmatic introduction to Christian anarchism than a systematic discussion of Christian anarchist thought.

Aside from that book, Bartley is Co-Director of Ekklesia, a Christian think-thank that carries forward some of what he advocates in his book and brings together several commentators who share that perspective. Bartley also does a lot of work with the media, appearing regularly on television and on the radio.

One can therefore argue over the extent to which the work that Bartley has been involved in should be considered theoretical, but his book and some of the articles produced by Ekklesia are nonetheless weaved into this book when doing so proves helpful in outlining Christian anarchism.

Christian anarcho-capitalists

On the internet, one also finds several usually fairly short pages and essays making the case for a free-market type of Christian anarchism. As with its secular equivalent, Christian anarcho-capitalism seems to be largely an American phenomenon, intellectual credit is often given to Murray Rothbard, and the crucial difference with other anarchists is the issue of private property. This book does not seek to resolve this disagreement over property. Instead, it incorporates the persuasive arguments made by Christian anarcho-capitalists on a variety of issues, and notes, where relevant, the points at which Christian anarcho-capitalists take views which conflict with those of other Christian anarchists.

James Redford

Perhaps the most systematic defence of Christian anarcho-capitalism is James Redford’s “Jesus Is an Anarchist.” Parts of that essay, however, could be improved by more balanced and more meticulous argumentation. Some passages are well argued and useful, but other passages are unconvincing and poorly justified. Tellingly perhaps, the case for private property is rather weak and evasive. Nevertheless, Redford’s essay is cited and debated among (Christian and secular) anarcho-capitalists on the internet. Moreover, since some of its sections are thorough and convincing enough and certainly resonate with the thinking of other Christian anarchists, Redford’s essay has been included in this book.

Kevin Craig (Vine and Fig Tree)

The case for Christian anarcho-capitalism is also made by Kevin Craig in a number of interlinked internet pages, which are usually anonymous and officially published by “Vine and Fig Tree.” Craig describes himself as belonging to both the radical Left (illustrated, he argues, by his stay in a Catholic Worker community for ten years) and the radical Right (for his anarcho-capitalism, that is). His web pages vary in style and rigour, but several of them make interesting arguments and cite plenty of Bible passages that strengthen the case for Christian anarchism. Very often, however, their focus is specific to the United States and its public. Moreover, some of the assertions expressed in these pages are simplistic and deliberately inflammatory. Classed under “socialism,” for instance, which Craig clearly abhors, are “Stalinist Industrialism” and “Washington bureaucrats” alike.[69] In other words, Craig’s pages are a mixed bag of thoughtful reflections and rather crude rants. Therefore, only what they contain which is of relevance to a generic outline of Christian anarchism has been included here.

Strike the Root, Lew Rockwell and Libertarian Nation essayists

The Strike the Root, Lew Rockwell and Libertarian Nation Foundation websites all describe themselves as against the state and for the free market. All three supply banks of short essays by a number of authors (who sometimes refer to one another’s essays) on anarcho-capitalism, some of which take the Christian perspective. Several of these essays are very well written and discuss key Bible passages or theoretical arguments for Christian anarchism, and have therefore provided valuable contributions to this book.

George Tarleton

The last author for whom the title “Christian anarchist” seems applicable is Great Briton George Tarleton, because he published a book titled Birth of a Christian Anarchist. That title, however, can be deceptive: although the book briefly mentions Proudhon and Bakunin and claims, in passing, that Jesus was an anarchist, it is not an exposition of Christian anarchism. No scholarly argument is presented for why Christianity would imply anarchism, no mention is made of any Christian anarchist, and in the end, one is left with the feeling that the word “anarchism” was chosen mainly to describe Tarleton’s eccentric and perhaps indeed somewhat anarchic practice of Christianity.[70] It certainly contains very little of direct value to Christian anarchist thought. The aim of this book being to weave together a generic outline of Christian anarchism, references to Tarleton are minimal.

Supportive thinkers

On top of the Christian anarchist thinkers introduced thus far, the case for Christian anarchism sometimes finds support in arguments put forward by a number of thinkers who do not themselves reach the anarchist conclusions that these arguments could lead them to.

Peter Chelčický

Starting with the oldest, the one thinker prior to the nineteenth century whose thought has been weaved into this book is Czech reformer Peter Chelčický (c.1390-c.1460). As he preceded by several centuries both the rise to power of the state (as explained in Chapter 3) and the very adoption of the term “anarchism” as a thoughtful political position, he could not really fully develop his argument towards the explicitly anarchist conclusions reached by later Christian anarchists. Nonetheless, he is included here for a number of reasons.