Anarchist Federation

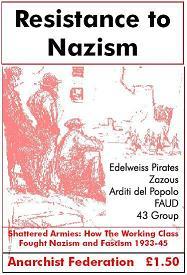

Resistance to Nazism

Shattered Armies: How The Working Class Fought Nazism and Fascism 1933–45

Young People and the Nazis: The Edelweiss Pirates

Anarchist Resistance to Nazism — The FAUD Underground in the Rhineland

Formation of the Fascist squads

The underground Italian anarchist press inside and outside fascist Italy

Voci officina (Voice of the factories)

Lotta anarchica (anarchist struggle)

Ai Lavatori d’Italia (To the Italian workers)

Fronte Unico dei Lavatori (United Workers Front)

L’Adunata dei Libertari: voci dei comunisti libertari (voice of the libertarian communists)

Introduction

In this pamphlet, we explore different forms of resistance to Nazism in the 1930s and 1940s. Firstly, the Edelweiss Pirates, thousands of young German people who combined a thirst for freedom with a passion for street-fighting and satirical subversion of the Nazi state. Secondly, the story of the FAUD, German anarcho-syndicalists who went underground in 1932 and undertook a long struggle against fascism while continuing to develop networks and ideas aimed at a free society through the general strike against oppression. Finally, the Zazus, French counter-culturalists and alternative lifestylers – in our terms – who did much more than simply celebrate their difference and party. They fought as well. These stories reveal the power of the organised working class and the danger to capitalism and authoritarianism posed by the innate and ever-present desire for freedom within every human being. They also reveal the extent of a resistance hidden within the shadows cast by the corpses of the remembered dead, the statues of victorious generals and glorious martyrs or distorted by the commercialisation of history.

The Second World War is remembered as a struggle between freedom and oppression and so it was. But in social terms it was also a struggle between two different forms of capitalism – authoritarian vs bourgeois – in which progressive forces in society were almost entirely destroyed. Of the 20 million people who died, many millions were communists, intellectuals, students, socialists and anarchists; virtually the entire movement of organised labour, its trade unions and left-wing parties and organisations were physically eliminated by hanging, shooting, starvation, disease and exile. This was a crushing blow and has haunted anarchism ever since. Don’t look for organisational reasons for why anarchism or libertarian communism have been marginal forces in the development of Europe since 1945. Look for the graves, seek out the places where its tens of thousands – and the millions of other progressive activists – went down fighting.

When we think about the resistance to Nazism, three or four images come to mind: the dour but romantic French maquis blowing up German troop trains, the beautiful SOE operative parachuting into Occupied Europe, the tragic heroism of the student pacifists pitting wits and bodies against the Gestapo and SS. Their struggles and suffering are portrayed as a patriotic response to physical occupation and ideological oppression, a thing that is forced upon them, an unnatural condition which ends with the liberation until all that is left are grainy photographs and the quiet voices of old people, remembering. There was the French resistance, the Warsaw uprising, Yugoslav partisans: native struggles in response to alien occupation, whose only ambition was liberation and the restoration of the nation-state. But there was more: blows struck, voices raised that once went unheard but that speak to us still. This pamphlet is about that other resistance, one involving hundreds of thousands of people, that began not in 1939 but many years earlier. A resistance not against occupation but against fascism and for freedom. A resistance that was international, rejecting the tired slogans of empire and fatherland, not a desperate struggle for survival against Hitler’s ten year Reich but a war begun on the barricades of 1848: against tyranny, exploitation and war and for freedom, brotherhood and peace. A resistance rooted in the organised working class and its understanding that fascism brings only exploitation, terror and war, that authoritarian and totalitarian governments of all kinds are good only for one class – the ruling class, the merchants, the generals and industrialists. These histories remind us of the almost limitless strength of the aware and self-organising working class, its capacity for struggle and sacrifice, it’s determination to hold on to its ideals in the face of brutal oppression. There is another history that we are writing even today.

Before Hitler could build the war machine he needed to acquire power for himself and lebensraum for the German people – to be built amongst the mass graves of the ethnically-cleansed east and south – he needed to defeat this powerful and dangerous resistance. Hitler’s first victims were not the Jews, the intellectuals, the Poles or Russians. The first victims of Nazism – deliberately so – were communists, trade unionists, anarchists, working class communities and activists. Hundreds of thousands of working class people, whole communities, trade union branches, workers’ societies and leagues were liquidated, their members arrested, imprisoned, exiled or driven underground, sent to forced labour and re-education camps and later, konzentrationslager: concentration camps.

It is difficult, now, to imagine the strength of that resistance. Hitler is often portrayed as a progressive campaigner who took to the air to criss-cross Germany, winning the hearts and minds of its people. It’s not well-known that this was a tactic forced on the Nazis because it was less dangerous than travelling by road or rail! Just months before the National Socialists seized power, Goebbels was chased out of Koln – his home town – ‘like a criminal’ by anarcho-syndicalist protests and mass action. All over Germany before 1933, vigorous and determined action, taken over the heads of social democratic and trade union leaders, gave the Nazis a very hard time.

Marches by Nazis were often surrounded and had to be protected by the police, their hit squads often ambushed and beaten up (or killed) by organised workers. The resistance took its strength from the experiences of workers and the lessons learned during the period of social upheaval and repression following WWI. Its resilience and dynamism was rooted in the desire for a socially-just, progressive and peaceful society, things that millions of people were prepared to struggle, fight and die for. Its weakness lay in the separate methods of organisation of anarchists, socialists and communists and competition between them for the loyalty of working people, rather than co-operation. And as with the period before WWI, nationalism, patriotism and sectional identities weakened the front for progress and justice. The Second World War was simply the final phase of a seventy-year struggle between authoritarian and bourgeois capitalism, a long struggle that decimated progressive forces in Europe and elsewhere, precluding the possibility of forming any other society in the ruins of the old except on democracy’s terms.

In the 1930s, the level of repression was so severe that only individualist activities were possible. In Germany, assassination plots – many against Hitler himself — and murders were attempted, pamphlets and posters printed and distributed, sabotage in the factories carried out. An underground network formed by the FAUD – German anarcho-syndicalists — managed to raise money for anarchists fighting fascism in Spain during 1936–39 and smuggled technicians across Europe to assist them. But without a mass base, anarchists and those they worked with were gradually hunted down, suppressed. Ernest Binder, a FAUD member wrote in 1946: “Since mass resistance was not feasible in 1933, the finest members of the movement had to squander their energy in a hopeless guerilla campaign. But if workers will draw from that painful experiment the lesson that only a truly united defence at the proper time is effective in the struggle against fascism, their sacrifices will not have been in vain.”

“Hopeless”? Maybe. Squandered? Never.

With the complete collapse of organised labour resistance to Nazism – its leaders in prison or exile, activists in concentration camps or underground, working class districts terrorised by SA and Gestapo raids and arrests, its funds and printing presses seized, its organisations and newspapers declared illegal – anarchist resistance too had to go underground and gradually lost coherence and the ability to act. This didn’t just occur in Germany. Italian anarchists continued to fight the fascist gangs throughout this period, forming their own partisan bands as social struggles became military but retaining a hard political analysis and edge, continuing their call for social revolution. The anarchist movement in France – because it was internationalist and anti-war – was suppressed in 1939–40 for resisting mobilisation, with activists arrested, imprisoned for refusing to be drafted or forced into hiding. After the occupation in 1939, Polish trade union organisations were proscribed but syndicalists gathered its militant remnants together in the Polish Syndicalist Union (the ZSP) and organised both propaganda and overt resistance. An illegal new-sheet, the Syndicalist, was published and the ZSP actively resisted in co-operation with the National Army (the AK) and People’s Army (AL); ZSP detachments took part in the Warsaw Uprising in 1944.

Resistance coalesced amongst affinity groups or upon the remains of pre-war political and industrial networks amongst organised workers. Anarchists who had direct experience of fascism, for instance in Germany and Italy, retained their internationalist and revolutionary goals and organised separately, though often co-operating with resistance groups. They published radical pamphlets and bulletins and continued to call for social revolution. One example is the Revolutionary Proletarian Group formed in France in 1941 by revolutionaries of many nationalities and which issued a manifesto in 1943 calling for an international republic of workers councils. It urged economic resistance, the disaffection of German soldiers and workers and resistance to forced labour drafts whilst forming clandestine factory committees and militias. Thousands of German soldiers did desert but at the cost of hundreds of lives: executed, starved, shot ‘while escaping’ or simply disappeared. At the same time, a secret congress of anarchists and libertarians was held under the noses of the Vichy authorities in Toulouse. It formed the International Revolutionary Syndicalist Federation and aimed to organise a mass general strike as soon as conditions permitted, while continuing guerilla resistance and economic sabotage.

Other anarchists were drawn into the struggles against Nazi occupation as an extension of their long fight against fascism or the hope of social progress with liberation. In 1940 there were 230,000 Spanish Republican exiles in France, of whom 40,000 – anarchists, socialists and communists – joined the maquis; perhaps as many as 30,000 died in the struggle. Spanish exile units fought in many battles during the war and anarchist battalions with names like “Durutti”, “Guernica” and “Guadalajara” on their vehicles took part in the liberation of Paris while 50 French towns, including Toulouse, were liberated by Spanish guerilla groups.

Yet, as the post-war settlement proved, democracy is simply a more benign form of capitalist authoritarianism. National liberation and anti-imperialist struggles – though ultimately victorious – simply further entrenched capitalist social relations within society. Some anarchists predicted this. The Friends of Durutti, a radical group during the Spanish Revolution, argued that anarchists and libertarians who had set aside revolutionary goals to help the bourgeois Spanish Republic fight fascism had gained nothing, suffering defeat, exile, death and the destruction of their popular workers collectives and the other organisations by which people were self-managing society in the midst of war. Even after victory, oppression continued: anarchists who had refused to be drafted in 1939 or who had carried out ‘illegal’ actions against state targets were arrested and convicted despite serving in the Resistance.

What this history tells us is the importance of fighting fascism wherever it rears its ugly head, of the need to put aside sectarian differences. An aware, progressive and mobilised working class is one of the most powerful forces in the world, strongest when it acts from its own sense of what is necessary, weakest when badly led. And because fascism is a facet of capitalism, it cannot be fought except upon the basis of the social relations capitalism creates. National liberation without social revolution merely postpones an inevitable struggle and continues an oppressive and deadening life without freedom.

Anarchist Federation, April 2006

Young People and the Nazis: The Edelweiss Pirates

And keep us locked in chains,

But we will smash the chains one day,

We’ll be free again

We’ve got fists and we can fight,

We’ve got knives and we’ll get them out

We want freedom, don’t we boys?

We’re the fighting Navajos!

Why were the Nazis able to control Germany so easily? Why was there so little active opposition to them? Why were the old parties of the SPD and KPD unable to offer any real resistance? How could a totalitarian regime so easily contain what had been the strongest working class in Europe?

We are taught that the Nazis duped the German population and that it took the armed might of the Allies to liberate Europe from their enslavement. This article aims to show how the Nazis were able to contain the working class and to tell some of the tales of resistance that really took place.

Dealing with the opposition

Acting with a ruthlessness that surprised their opponents, the Nazis banned their opponents, the Social Democrats and the Communists. For the working class this was far more serious than just the destruction of two state capitalist parties. It was accompanied by the annihilation of a whole area of social life around working class communities. Many of the most confident working class militants were arrested and sent to concentration camps.

The repression was carried out legally. The SA (the Brownshirts) now acted in collaboration with the police. Their brutal activities which once had been illegal but tolerated now became part of official state activity. In some circumstances this meant simple actions like beatings. In others, SA groups moved into and took over working class pubs and centres. The effect was to isolate, intimidate and render powerless the working class.

Many workers believed that the Nazis would not remain in power forever. They believed that the next election would see them swept from power and ‘their’ parties returned. Workers only needed to bind their time. When it became clear that this was not going to happen, the myth changed. The role for oppositionists became to keep the party structures intact until such time as the Nazis were defeated. There is no doubt that even the simple act of distributing Socialist (SPD) or Communist (KPD) propaganda took an incredible degree of heroism, for the consequences of being caught were quite clear to all – beatings, torture and death. It meant that families would be left without breadwinners, subjected to police surveillance and intimidation.

The result was often passivity and inaction. As early as 1935, workers were aware of the consequences that ‘subversive’ activity would have on their families. A blacksmith in 1943 expressed the problem simply: “My wife is still alive, that’s all. It’s only for her sake that I don’t shout it right in their faces…You know these blackguards can only do all this because each of us has a wife or mother at home that he’s got to think of…people have too many things to consider. After all, you’re not alone in this world. And these SS devils exploit the fact.”

Throughout the period of Nazi rule there was industrial unrest, there were strikes and acts of disobedience and even sabotage. All these, however, attracted the attention of the Gestapo. The Gestapo had the assistance of employers and stooges in the workforce. The least a striker could expect was arrest. As a consequence, those who were politically opposed to the Nazi state kept themselves away from industrial struggle. To be arrested would have led not only to personal sacrifice, but also could have compromised the political organisations to which he or she belonged. To reinforce the message to workers, he Gestapo set up special industrial concentration camps attached to major factories.

To put the intensity of Nazi repression into context, during the period 1933–45, at least 30,000 German people were executed for opposing the state. This does not include countless others who died as a result of beatings, of their treatment in camps, or as a result of the official policy of euthanasia for those deemed mentally ill. Thousands of children were declared morally or biologically defective because they fell below the below the Aryan ‘norm’ and were murdered by doctors. This fate also befell youngsters with mental and physical disabilities as well as many who listened to the wrong kind of music.

However, Nazi domination of the working class did not rely solely on repression. Nazi industrial policy aimed to fragment the class, to replace working class solidarity with Nazi comradeship and solidarity with the state.

To start with, pay rises were forbidden. To strengthen competition, hourly rates were done away with. Piece rates became the norm. If workers wanted to earn more then they would have to produce more. Workers’ interests were to be represented by the German Workers’ Front (DAF), which they were forced to belong to and which of course represented solely the interests of the state and employers.

Unable to obtain pay rises with their employers it became common in a situation of full employment for workers to move from one factory to another in search of higher wages. On the one hand, this defeated the Nazi objectives of limiting pay; on the other hand it further weakened the bonds of solidarity between workers. Knowing that they could not rule solely through fear, the Nazis gave ‘welfare’ concessions to the working class. Family allowances were paid for the first time; organised holidays and outings were provided at low cost. For many workers this was their first opportunity to go away on holiday. Social activities were provided through Nazi organisations.

There is little evidence that the Nazis won over the working class ideologically, nonetheless, this combination of repression and amelioration served to confuse many who would otherwise have been outright opponents. The spectacles we have all seen of Nazi rallies, book burnings, parades and speeches are not evidence that workers were convinced of Nazi rule. It was clear to all what the consequence of not attending, of not carrying a placard or waving a flag would be. However, they must have increased the sense of isolation and powerlessness of those who would have liked to resist. As a result there was little open resistance from working class adults to the Nazis throughout their period in power.

Young People

If the Nazi policy towards adults was based on coercion, their policy towards young people was subtler. Put simply, the intention was to indoctrinate every young person, to make them a good national socialist citizen proudly upholding the ideals of the party. The means chosen to do this was the Hitler Youth (HJ).

By the end of 1933, all youth organisations outside the Hitler Youth had been banned – with the exception of those controlled by the Catholic Church that was busy cozying up to the Nazis at the time. Boys were to be organised into the Deutsches Jungvolk between the ages of 10 and 14 and the Hitler Youth proper from 14 to 18.

They quickly incorporated around 40% of boys. Girls were to be enrolled into the Bund Deutsche Madel (BDM), but the Nazis were much less interested in getting them to join. The objective was to get all boys into the HJ. When this failed to take place, laws were passed gradually making it compulsory by 1939. In the early days, being in the HJ was far from a chore. Boys got to take part in sports, go camping, hike, play competitive games – as well as being involved in drill and political indoctrination. Being in the HJ gave youngsters the chance to play one form of authority off against another. They could avoid schoolwork by claiming to be involved in HJ work. The HJ provided excuses when dealing with other authority figures – like parents and priests. On the other hand, they could also blame pressures from school in order to get out of more unpleasant Hitler Youth tasks! In some parts of the country the HJ provided the first opportunity to start a sports club, to get away from parents, to experience some independence.

As the 1930s went on, the function of the HJ and BDM changed. The objectives of the regime became more obviously military and aimed at conquest. The HJ was seen as a way recruiting and training young men into the armed forces. As war became more likely, the emphasis shifted away from leisure activities and into military training, State policy became of one of forcing all to be in the HJ. T made seemingly harmless activities, like getting together with your mates for an evening, criminal offences if they took place outside the HJ of BDM.

The HJ set up its own police squads to supervise young people. These Streifendienst patrols were made up of Hitler Youth members scarcely older than those they were meant to be policing.

By 1938, reports from Social Democrats in Germany to their leaders in exile were able to report that: “In the long run young people too are feeling increasingly irritated by the lack of freedom and the mindless drilling that is customary in the National Socialist organisations. It is therefore no wonder that symptoms of fatigue are becoming particularly apparent among their ranks…”

The outbreak of war brought the true nature of the HJ even more sharply into focus. Older HJ members were called up. More and more time was taken up with drill and political indoctrination. Bombing led to the destruction of many of the sporting facilities. The HJ became more and more obviously a means of oppression. As the demands for fresh recruits to the armed forces became more intense, the divisions within the HJ became more acute. The German education system at the time was sharply divided along class lines. Most working class children left school at the age of 14. A few went on to secondary or grammar schools along with the children of middle class and professional families. As older HJ members were called up, the middle class school students took the place of the leaders. The rank and file was increasingly made up of young workers hardly likely to take too well to being ordered about at HJ meetings!

It is not difficult to imagine the scene of a snotty doctor’s kid still in school trying to give orders to a bunch of young factory workers and having to use the threat of official punishment to get his own way. Dissatisfaction grew. Initially, the acute labour shortages of the early war years meant that the Nazis could not resort to the kind of Nazi terror tactics that they employed against other dissidents. As the war went on, many of these young people’s fathers died or were sent to the front. Many were bombed out of their own homes. The only future they could see for themselves was to wear a uniform and fight for a lost cause.

One teenager said in 1942: “Everything the HJ preaches is a fraud. I know this for certain, because everything I had to say in the HJ myself was a fraud.” By the end of the 1930s, thousands of young people were finding ways to avoid the clutches of the Hitler Youth. They were gathering together in their own gangs and starting to enjoy themselves again. This terrified the Nazis, particularly when the teenagers started to defend their own social spaces physically. What particularly frightened the Nazis was that these young people were the products of their own education system. They had no contact with the old SPD or KPD, knew nothing of Marxism or the old labour movement. They had been educated by the Nazis in Nazi schools, their free time had been regimented by the HJ listening to Nazi propaganda and taking part in officially approved activities and sports.

These gangs went under different names. Their favoured clothes varied from town to town, as did their badges. In Essen they were called the Farhtenstenze (Travelling Dudes), in Oberhausen and Dusseldorf the Kittelbach Pirates, in Cologne they were the Navajos. But all saw themselves as Edelweiss Pirates (named after an edelweiss flower badge many wore).

Gestapo files in Cologne contain the names of over 3,000 teenagers identified as Edelweiss Pirates. Clearly, there must have been many more and their numbers must have been even greater when taken over Germany as a whole. Initially, their activities were in themselves pretty harmless. They hung around in parks and on street corners, creating their own social space in the way teenagers do everywhere (usually to the annoyance of adults). At weekends they would take themselves off into the countryside on hikes and camping trips in a perverse way mirroring the activities initially provided by the HJ themselves.

Unlike the HJ trips, however, these expeditions comprised boys and girls together, so adding a different, more exciting and more normal dimension than provided by the HJ. Whereas the HJ had taken young people away for trips to isolate and indoctrinate them, the Edelweiss Pirates expeditions got them away from the Party and gave them the time and space to be themselves.

On their trips they would meet up with Pirates from other towns and cities. Some went as far as to travel the length and breadth of Germany doing wartime, when to travel without papers was an illegal action.

Daring to enjoy themselves on their own was a criminal act. They were supposed to be under Party control. Inevitably they came across HJ Streifendienst patrols. Instead of running, the Pirates often stood and fought. Reports sent to Gestapo officers suggest that as often as not the Edelweiss Pirates won these fights. “I therefore request that the police ensure that this riff-raff is dealt with once and for all. The HJ are taking their lives into their hands when they go out on the streets.”

The activities of the Edelweiss Pirates grew bolder as the war progressed. They engaged in pranks against the allies, fights against their enemies and moved on to small acts of sabotage. They were accused of being slackers at work and social parasites.

They began to help Jews, army deserters and prisoners of war. They painted anti- Nazi slogans on walls and some started to collect Allied propaganda leaflets and shove them through people’s letterboxes.

“There is a suspicion that it is these youths who have been inscribing the walls of the pedestrian subway on the Altebbergstrasse with the slogans ‘Down with Hitler’, ‘The OKW (Military High Command) is lying’, ‘Medals for Murder’, ‘Down with Nazi Brutality’ etc. However often these inscriptions are removed within a few days new ones appear on the walls again.” (1943 Dusseldorf-Grafenberg Nazi Party report to the Gestapo).

As time went on, a few grew bolder and even more heroic. They raided army camps to obtain arms and explosives, made attacks on Nazi figures other than the HJ and took part in partisan activities. The Head of the Cologne Gestapo was one victim of the Edelweiss Pirates.

The authorities reacted with their full armoury of repressive measures. These ranged from individual warnings, round-ups and temporary detention (followed by a head shaving), to weekend imprisonment, reform school, labour camp, youth concentration camp or criminal trial. Thousands were caught up in this hunt. For many, the end was death. The so-called leaders of the Cologne Edelweiss Pirates were publicly hanged in November 1944.

However, as long as the Nazis needed workers in armament factories and soldiers for their war, they could not resort to the physical extermination of thousands of young Germans. Moreover, it is fair to say that the state was confused as to what to do with these rebels. They came from German stock, the sort of people who should have been grateful for what the Nazis gave. Unwilling to execute thousands and unable to comprehend what was happening, the state was equally unable to contain them.

Wall of Silence

So why has so little been heard of the Edelweiss Pirates? When researching this article, it was extremely hard to find information about them. Most seemed to revolve around the research of the German historian Detlev Peukert, whose writings remain essential reading. Searches of the internet revealed only two articles. A number of explanations come to mind. The post-war Allied authorities wanted to reconstruct Germany into a modern, western, democratic state. To do this, they enforced strict labour laws including compulsory work. The Edelweiss Pirates had a strong anti-work ethos, so they came into conflict with the new authorities too. A report in 1949 spoke of the “widespread phenomenon of unwillingness to work that was becoming a habit of many young people.” The prosecution of so-called ‘young idlers’ was sometimes no less rigid under Allied occupation than it was under the Nazis. A court in 1947 sent one young woman to prison for five months for ‘refusal to work’. The young became enemies of the new order too.

The political opponents of the Nazis had been either forced into exile, murdered or hid their politics. Clandestine activity had centred on keeping party structures intact. They could not afford to acknowledge that physical resistance had been alive and well and based on young people’s street gangs! To the politicians of the CDU (Christian Democratic Union) and SPD, the Edelweiss Pirates were just as much riffraff as they were to the Nazis. The myth of the just war used by the allies relied heavily on the idea that all Germans had been at least silent during the Nazi period if not actively supporting the regime. To maintain this fiction the actions of ‘street hooligans’ in fighting the Nazis had to be forgotten.

Fifty-five years on, interest in the Edelweiss Pirates is beginning to resurface. More is being published on them and a film has been produced in Germany. We need to make sure that they are never forgotten again. As the producers of the film say: “the Edelweiss Pirates were no absolute heroes, but rather ordinary people doing extraordinary things.” It is precisely this that gives us hope for the future.

And smash the Hitler Youth in twain.

Our song is freedom, love and life,

We’re the Pirates of the Edelweiss.

The 43 Group

The 43 Group was formed by Jewish ex-servicemen and women as a direct action organization to combat the re-emergence of Britain’s fascists after WW2, firstly on the streets of London and later throughout the country. It’s history is told in a fascinating book (see below); a hidden history of working class resistance and a manual of modern-day direct action campaigning offering many useful insights into organizational methods.

After WW2, Jews were alarmed at the resurgence of Britain’s fascists, aided and abetted by the Labour Government’s complacency and often the connivance of the police, town halls, watch committees and local magistrates, who defended the Fascist’s right to free speech but cracked down hard on counter-protests (sound familiar?).

Fascist groups and parties re-formed, newspapers and “book clubs” flourished, candidates stood and hectored. After bitter and frustrating experiences directly confronting the fascists only to be met with police strong-arm tactics and court appearances, 43 Jewish ex-servicemen and women met to form a group aimed at destroying the growing fascist movement.

The group organized from the bottom up and by word-of-mouth with most recruitment on a personal basis. It formed local cells but with access to the resources of the whole organization, which grew quickly. Taxi drivers provided transport and a quick getaway, people with fighting skills organized in flying wedges to drive in and break up fascist street demos and meetings, others worked in intelligence and counterintelligence (some even joining fascist groups) and security (looking for moles, moving equipment). Contact was made with sympathetic policemen and journalists and local communities mobilized against fascist groups and activities. It was a tough job: fascism was still an international movement, thuggish Nazi prisoners-of-war had remained behind in Britain, it could call on the wealth of the lunatic fringes of the aristocracy and bourgeoisie for money and influence. But the constant pressure of the 43 Group and its supporters and allies, notably the Communist party, paid off. Fascist groups found they could not organize and were under constant surveillance and attack, meetings were constantly disrupted, local newspapers began to openly scorn the fascists and indignantly call on the government to act against them and the town halls, now aware of the depth of local feelings, began to deny them access to the school halls and meeting rooms that gave them an air of respectability. By the early 1950s, after years of struggle, the fascist menace was largely defeated – still present, they were not likely to pose a serious threat and did not again until the 1970s.

This is a little-known but largely positive history, marred only by the fact that the Jewish establishment, like many bourgeois liberals, attacked the 43 Group (which had, at its height, thousands of members and supporters) for being ‘thugs’, ‘heavies’ who delighted in violence – a sorry accusation leveled at Class War in the 1980s and 1990s and the Black Bloc even today. Any activity the middle classes cannot control frightens them to death. The book is a good read that repays careful study. The 43 Group, Morris Beckman, a Centerprise Publication ISBN: 0 903738 75 9

Anarchist Resistance to Nazism — The FAUD Underground in the Rhineland

The anarcho-syndicalist union the Freie Arbeiter Union (FAUD) had a strong presence in Duisberg in the Rhineland, with a membership in 1921 of around 5,000 members. Then this membership fell away and by the time Hitler rose to power there were just a few little groups. For example, the number of active militants in Duisberg-South was 25, and the Regional Labour Exchange for Rhineland counted 180 to 200 members. At its last national congress in Erfurt in March 1932, the FAUD decided that if the Nazis came to power its federal bureau in Berlin would be dissolved, that an underground bureau would be put in place in Erfurt, and that there should be an immediate general strike. This last decision was never put into practice, as the FAUD was decimated by massive arrests.

In April or May 1933, doctor Gerhard Wartenburg, before being forced to leave Germany, had the locksmith Emil Zehner put in place as his replacement as FAUD secretary. He fled to Amsterdam, where he was welcomed, with other German refugees, by Albert de Jong, the Dutch anarcho-syndicalist. At the same time the secretariat of the International Workers Association (the anarcho-syndicalist international) was transferred to Holland in 1933, though the Nazis seized its archives and correspondence. In autumn 1933, Zehner was replaced by Ferdinand Goetze of Saxony, then by Richard Thiede of Leipzig. Goetze reappeared in western Germany in autumn 1934, already on the run from the Gestapo. In the meantime, a secret group of the FAUD was set up, with the support of the Dutch section of the IWA, the NSV. A secretariat of the FAUD in exile was set up in Holland. Up to the rise to power of the Nazis, the worker Franz Bungert was a leading member of the Duisberg FAUD. Without even the pretence of a trial, he was interned in the concentration camp of Boegermoor in 1933. After a year he was freed but was put under permanent surveillance. His successor was Julius Nolden, a metalworker then unemployed and treasurer of the Labour Exchange for the Rhineland. He was also arrested by the Gestapo, who suspected that his activity in a Society for the Right to Cremation(!) hid illegal relations with other members of the FAUD.

In June 1933, a little after he was released, he met Karolus Heber, who was part of the secret FAUD organisation in Erfurt. He had been part of the General Secretariat in Berlin, but after many arrests there had to move to Erfurt. They arranged a plan for the flight of endangered comrades to Holland and the setting up of a resistance organisation in the Rhineland and the Ruhr.

Nolden and his comrades set up a secret escape route to Amsterdam and distributed propaganda against the Nazi regime. Albert de Jong visited Germany and via the FAUD member Fritz Schroeder, met Nolden. De Jong arranged for the sending of propaganda over the border via the anarchist Hillebrandt. One pamphlet was disguised with the title Eat German Fruit And You Will Be In Good Health. It became so popular among the miners that they used to greet each other with: ”Have you eaten German fruit as well?” As for the escape route, the German-Dutch anarchist Derksen, who had a very good knowledge of the border zone, was able to get many refugees to safety. Many of those joined the anarchist columns in Spain.

After 1935, with the improvement of the economic situation in Germany, it was more and more difficult to maintain a secret organisation. Many members of the FAUD found jobs again after a long period of unemployment and were reluctant to engage in active resistance. The terror of the Gestapo did the rest. On top of this, no more propaganda was sent from Amsterdam.

The outbreak of the Spanish Revolution in 1936 breathed new life into German anarchism. Nolden multiplied his contacts in Duisberg, Düsseldorf and Cologne, organising meetings and launching appeals for financial aid to the Spanish anarchists. As a result of Nolden’s tireless activities, several large groups were set up. Nolden went everywhere by bike! At the same time Simon Wehren of Aachen used the network of FAUD labour exchanges to find volunteer technicians to go to Spain.

In December 1936, the Gestapo, thanks to an informer they had infiltrated, uncovered groups in Moenchengladbach, Duelken and Viersen. At the start of 1937, 50 anarcho- syndicalists of Duisberg, Düsseldorf and Cologne were arrested, including Nolden. A little later other arrests followed, bringing to 89 the number of FAUD members in Gestapo hands. The trial lasted a year on charges of “preparation of acts of high treason”[1]. There were 6 acquittals for lack of evidence, the others being condemned to prison sentences from several months to 6 years in January-February 1938. Nolden was sent to the Luettringhausen Penitentiary from which the Allies freed him on 19th April 1945. In Whitsun 1947 he was at Darmstadt with other survivors of the Duisberg group to found the Federation of Libertarian Socialists. In prison, several anarchists were murdered. Emil Mahnert, a turner of Duisberg, was thrown from a second floor window by a police torturer. The mason Wilhelm Schmitz died in prison on 29 January 1944 in obscure circumstances. Ernst Holtznagel was sent to Disciplinary Battalion 999, of sinister reputation, and murdered there. Michael Delissen of Moenchengladbach was beaten to death by the Gestapo in December 1936. Anton Rosinke of Düsseldorf was murdered in February 1937.

The anarcho-syndicalist Ernst Binder of Düsseldorf wrote in August 1946: “A massive resistance not having been possible in 1933, the best of those at the heart of the workers movement had to disperse their forces in a guerrilla war without hope. But if, from this painful experience, the workers movement, the workers will draw from this the lesson that only united defence at the right moment is effective in the struggle against fascism, those sacrifices will not have been in vain”.

The Zazous

In 1940, the Nazis had occupied France. The Vichy regime, in collaboration with the Nazis and fascist itself in policies and outlook, had an ultra conservative morality, and started to use a whole range of laws against a youth that was restless and disenchanted.

In Paris, young people started meeting in cafes, passing their time mocking the politics of the time. This spontaneous development was a sharp response to the deadening effect on society of the Nazi-Vichy rule. They met in cinemas, in the cellar clubs and at parties arranged at short notice. These young people, who called themselves Zazous, were to be found throughout France, but were most concentrated in Paris. The two most important meeting places of the Zazous were the terrace of the Pam Pam café on the Champs Elysees and the Boul’Mich ( the Boulevard Saint- Michel near the Sorbonne. The Zazous of the Champs Elysees came from a more middle class background and were older than the Zazous of the Latin Quarter. The Champs Elysees Zazous were easily recognisable on the terrace of the Pam Pam and took afternoon bike rides in the Bois de Boulogne. In the Latin Quarter, the Zazous met in the cellar clubs of Dupont-Latin or the Capoulade.

The male Zazous wore extra large jackets which hung down to their knees, and which were fitted out with many pockets and often several half-belts. The amount of material used was a direct comment on government decrees on the rationing of clothing material. Their trousers were narrow, gathered at the waist, and so were their ties, which were cotton or heavy wool. The shirt collars were high and kept in place by a horizontal pin. They liked thick-soled suede shoes, with white or brightly coloured socks. Their hairstyles were greased and long . In fact after the government decree of 1942 which authorised the collection of hair from barber-shops to be made into slippers they grew their hair longer! In a parody of Englishness they carried formal “Chamberlain” umbrellas, always neatly furled, and never opened in spite of rainy weather.

Syncopated

One fascist magazine commented on the male Zazou :” Here is the specimen of Ultra Swing 1941: hair hanging down to the neck, teased up into an untidy quiff, little moustache a la Clark Gable,….. shoes with too thick soles, syncopated walk”. Female Zazous wore their hair in curls falling down to their shoulders or in braids. Blonde was the favourite colour, and they wore bright red lipstick, as well as sunglasses, also favoured by some male Zazous. They wore jackets with extremely wide shoulders and short pleated skirts. Their stockings were striped or sometimes net, and they wore shoes with thick wooden soles.

The Zazous were big fans of chequered patterns, on jacket, skirt or brolly. They started appearing in the vegetarian restaurants and developed a passion for grated carrot salad! They usually drank fruit juice or beer with grenadine syrup, a cocktail that they seem to have invented.

The zazous were directly inspired by jazz and swing music. A healthy black jazz scene had sprung up in Montmartre in the inter-war years. Black Americans felt freer in Paris than they did back home, and the home-grown jazz scene was greatly reinforced by this emigration. Manouche Gypsy musicians like Django Reinhardt started playing swinging jazz music in the Paris clubs.

The Zazous probably got their name from a line in a song –Zah Zuh Zah by the black jazz musician Cab Calloway famous for his Minnie the Moocher. A French crooner poular with the Zazous, Johnny Hess, also had a song Je suis swing in early 1942, in which he sung the lines “Za zou, za zou, za zou, za zou ze”.

An associate of the Zazous, the anarchist singer-songwriter, jazz trumpeter, poet and novelist Boris Vian was also extremely fond of z words in his work! The long drape jacket was also copied from zootsuits worn by the likes of Calloway. “The zazous were very obviously detested by the Nazis, who on the other side of the Rhine, had since a long time decimated the German cultural avante garde, forbidden jazz and all visible signs of…..degenerations of Germanic culture…” Pierre Seel, who as a young zazou was deported to a German concentration camp because of his homosexuality.

When the yellow star was forced to be worn by Jews, those non-Jews who objected to this began to wear yellow stars with “Buddhist” “Goy” (Gentile) or “Victory”. Some Zazous took this up, with “Zazou” written below the star. When the French Jews were removed from the scene, the Vichy regime and their Nazi masters turned on the Zazous. Vichy had started “Youth Worksites” in July 1940 in an attempt to indoctrinate French youth. The same year, they set up a Ministry of Youth. They saw the Zazous as a rival and dangerous influence on youth. By 1942, Vichy high-ups realised that the national revival that they hoped would be carried out by young people under their guidance were seriously effected by widespread rejection of the patriotism, work ethic, selfdenial, asceticism and masculinity this called for. The Zazous were degenerate and dandified and so weren’t a lot of these scum obviously Jews?

The witch hunt begins

78 anti-Zazou articles were published in the press in 1942 ( as opposed to 9 in 1941 and 38 in 1943). The Vichy papers deplored the moral turpitude and decadence that was effecting French morality. Zazous were seen as work-shy, egotistical, and Judeo- Gaullist shirkers. Soon roundups began in bars and zazous were beaten on the street. They became Enemy Number One of the fascist youth organisation Jeunesse Populaire Francais. “Scalp the Zazous!” became their slogan. Squads of young JPF fascists armed with hairclippers attacked Zazous. Many were arrested and sent to the countryside to work on the harvest. acquiescence,

At this point the Zazous went underground, holing up in their dance halls and basement clubs. With the Liberation of Paris it appears some zazous joined in the armed combat to drive out the Nazis – certainly they had a few scores to settle. But the Zazous were suspected by the official Communist resistance of having a “couldn’t give a fuck” attitude to the war in general.

The Zazous were to be numbered in the hundreds rather than thousands and were generally between 17 and 20. There were Zazous from all classes but with apparently similar outlooks. Working class Zazous used theft of cloth and black market activities to get their outfits, sometimes stitching their own clothes. Some of the more bohemian Zazous in the Latin Quarter varied the outfit, with sheepskin jackets and multicoloured scarves. It was their general attitude of ironic and sarcastic comments on the Nazi/Vichy rulers, their dandyism and hedonism, their suspicion of the work ethic and their love of “decadent” jazz that distinguished them as one of the prototype youth movements that were to question the values of capitalist society .Though they did not suffer like their contemporaries in Germany, the working class Edelweiss Pirates, some of whom were hanged by the Nazis, nevertheless in a society of widespread complicity and acquiescence, their stand was courageous and trail-blazing.

The Arditi del Popolo

Introduction

By the end of World War I, the working class in Italy were in a state of revolutionary ferment. Not yet ready for the conquest of power themselves, workers and peasants by 1918 had won a variety of concessions from the state: an improvement of wages, the 8-hour day, and recognition of collective contracts.

By 1919 a new radicalism had descended upon the labour movement. In that year alone there were 1,663 strikes across the peninsula, while in August the newly-formed shop stewards’ movement in Turin (the forerunner of the workers’ councils) underlined the growth of a new vibrant militancy that drew its strength from the autonomous capacity of workers to organise themselves along libertarian lines and which had “the potential objective of preparing men, organizations and ideas, in a continuous prerevolutionary control operation, so that they are ready to replace employer authority in the enterprise and impose a new discipline on social life”[1].

In the countryside the peasantry opened up a second front against the state by occupying the land that had been promised them before the war. The Visochi decree of September 1919 merely validated the cooperatives that had already been set up while the ‘red leagues’ assisted the formation of strong unions of day labourers. 1919 also marked the initial signs of capital defending itself against the growing onslaught. A meeting of industrialists and landowners at Genoa in April sealed the first stages of the ‘holy alliance’ against the rise of labour power. From this meeting were drawn up plans for the formation, in the following year, of both the General Federation of Industry and the General Federation of Agriculture, which together worked out a precise strategy for the dismantling of the labour unions and the nascent councils. Alone, however, the industrialists and landowners could not undertake the struggle against the labour movement. The workers themselves had to be cowed into submission, had to have their spirit of revolt broken on the very streets they walked and the fields they sowed. For this, capital turned to the armed thuggery of fascism, and its biggest thug of all: Benito Mussolini.

Formation of the Fascist squads

Immediately following the end of the war, there was a veritable flowering of antilabour leagues: Mussolini’s Combat Fasci, the Anti-Bolshevik League, Fasci for Social Education, Umus, Italy Redeemed etc…At the same time, members of the Arditi, the war volunteer corps, on being demobilised organised themselves into an elite force of 20,000 shock troops and were immediately put to use by the anti-labour movement. This movement was mostly comprised of the middle or lower middle class. Ex-officers and NCOs, white collar workers, students and the self-employed all allied themselves to the fascist cause in the towns, while in the countryside the sons of tenant farmers, small land owners and estate managers were willing recruits in the war against the perceived Red Menace. The police and the army both actively encouraged the fascists, urging ex-officers to join and train the squads, lending them vehicles and weapons, even allowing criminals to enroll in them with the promise of benefits and immunity. Arms permits, refused to workers and peasants, were freely handed over to the fascist squadrons, while munitions from the state arsenals gave the Blackshirts an immense military advantage over their enemies. By November 1921 the various hit squads were welded together into a military organisation known as the Principi with a hierarchy of sections, cohorts, legions and a special uniform.

The Arditi del Popolo

To compensate for the shortcomings of the Socialist Party (PSI -Partito Socialista Italiana) and the main trade union, the CGL (see below), militants of various tendencies, anarcho-syndicalists, left socialists, communists and republicans formed, in June 1921, a people’s militia, the Arditi del Popolo (AdP), to take the fight to the fascists.

While politically diverse, the AdP was a predominantly working class organisation. Workers were enlisted from factories, farms, railways, shipyards, building sites, ports and public transport. Some sections of the middle class also got involved in the form of students, office workers, and other professional types. Structurally, the AdP was run along military lines with battalions, companies and squads. Squads were comprised of 10 members and a group leader. 4 squads made up a company with a company commander, and 3 companies made up a battalion with its own battalion commander. Cycle squads were used to maintain links between the general command and the workforce at large. In spite of its structure, the AdP remained elastic enough to form a rapid reaction force in response to fascist threats. AdP behaviour was dictated by whatever political group held sway in a particular locale although most sections were allowed virtual autonomy over their actions.

These sections were quickly set up in all parts of the country, either as new creations or as part of already existing groups like the Communist Party of Italy (PCdI — Partito Comunista d’Italia), the paramilitary Arditi Rossi in Trieste, the Children of No-One (Figli di Nessuno) in Genova and Vercelli.or the Proletarian League (Lega Proletaria — linked to the PSI). Overall, at least 144 sections had been set up by the end of summer 1921 with a total of about 20,000 members. The largest sections were the 12 Lazio sections with about 3,300 members, followed by Tuscany, 18 sections, with a total of 3,000 members. Other regions were as follows:

| Umbria | 16 s | 2,000 members |

| Marche | 12 s | 1,000 |

| Lombardy | 17 s | 2,100 |

| Tre Venezie | 15 s | 2,200 |

| Emilia Romagna | 18 s | 1,400 |

| Liguria | 4 b | 1,100 |

| Piedmont | 8 b | 1,300 |

| Sicily | 7 s | 600 |

| Campania | 7 | 500 |

| Apulia | 6 | 500 |

| Sardinia | 2 | 150 |

| Abruzzo | 1 | 200 |

| Calabria | 1 | 200 |

(s-section, b-battalion)

The AdP very quickly built up its own cultural identity with individual sections proudly flaunting their own logos and images of war. While the AdP as a whole was easily recognisable by a skull surrounded by a laurel wreath with a dagger in its teeth, and the motto ‘A Noi’ (To Us), the Directorates logo was a dagger surrounded by an oak and laurel wreath. The ivetavecchia meanwhile didn’t leave much to the imagination when choosing their banner – an axe smashing the fasces symbol! Although they did not have, nor want, their own uniform, the average AdP member preferred to dress in black sweaters, dark-grey trousers, with a red flower in their buttonholes. Their songs were as direct and confrontational as they themselves were:

“Rintuzziamo la violenza/ del fascismo mercenario./ Tutti in armi!sul calvario/ dell’umana redenzion./ Questa eterna giovinezza/ si rinnova nella fede/ per un popolo che chiede/ uguaglianza e libertà.”

“We curb the violence/of the mercenary fascists/ Everyone armed on the cavalry/of human redemption/ This eternal youth/is renewed in the faith/ for the people who demand equality and freedom.”

The Fascist Offensive

The Italian anarchist, Errico Malatesta, commenting on the massive factory occupations in northern Italy in September 1920 which involved 600,000 workers, predicted “if we do not carry on to the end, we will pay with tears of blood for the fears we now instill in the bourgeoisie”. His words were to be prophetic as both the PSI and CGL, instead of expanding the struggle from the factories into the community, collaborated with the state to return the workers to their jobs. It was from this moment onwards that the state moved onto the offensive, and Mussolini’s ‘revolutionary action’ squads were supplied with enough arms to take to the streets.

Until the formation of the AdP, the fascists had things mostly their own way. Starting off with an attack on the town hall in Bologna, the fascist squads swept through the countryside like a scythe, undertaking ‘punitive expeditions’ against ‘red’ villages. Following their success there, they began attacking the cities. Labour unions, the offices of co-operatives and leftist papers were destroyed in Trieste, Modena, and Florence within the first few months of 1921. As Rossi writes, they had “an immense advantage over the labour movement in its facilities for transportation and concentration… The fascists are generally without ties…they can live anywhere…The workers, on the contrary, are bound to their homes…This system gives the enemy every advantage: that of the offensive over the defensive, and that of mobile warfare over a war of position [2].”

However by March 1921 there were growing signs of working class defence structures being put in place. In Livorno, when a working class district (Borgo dei Cappucini) came under attack by the fascists, the whole neighbourhood mobilised against them, routing them from the town. In April, when the fascists launched an assault on one of the union centres (Camero del Lavoro), the workers held strike action on the 14th and surrounded the fascist squad, only for the army to rush to the fascists’ defence. By July, the working class had created their own armed militia –the Arditi del Popolo.

Arditi del Popolo In Action

The AdP first saw action in Piombino on July 19th, when they attacked a fascist meeting place and rounded up the fascists inside. When the Royal Guard tried to intervene, they too were forced to surrender. The AdP held the streets for a few days before the sheer size of police numbers forced them to withdraw. In Sarzana, they went to the aid of the local population that had managed to capture one the fascists’ most important leaders, Renato Ticci. When a squad of 500 fascists attempted to rescue Ticci, the AdP was there to force the fascists into the countryside. 20 fascists (probably more) were killed and their squadron leader commented: “The squad, so long accustomed to defeating an enemy who nearly always ran away, or offered feeble resistance, could not and did not know how to defend themselves”.

Sell Out

However, just as the AdP was building up the momentum on the streets, they were betrayed by the PSI who were more interested in signing a pact of nonaggression with the fascists; this at a time when the fascists were at their most vulnerable. Socialist militants were forced by their leadership to withdraw from the AdP, while the CGL union ordered its members to leave the organisation.

One union leader, Matteotti, confirmed the sell out in the union paper Battaglia Sindicale: “Stay at home: do not respond to provocations. Even silence, even cowardice, are sometimes heroic.”

The communists went one step further by forming their own pure ‘class conscious’ squadrons thus decimating the movement further. According to Gramsci, ‘the tactic… corresponded to the need to prevent the party membership being controlled by a leadership that was not the party leadership.” Quite soon, only 50 sections of 6000 members remained, supported both by the Unione Sindicale Italiana (USI) and the Unione Anarchica Italiana (UAI). A number of these sections went into action again in September in Piombino when the fascists, who had burned down the offices of the PSI (the same organisation that had sold them out a month before), were intercepted by an anarchist patrol and forced to flee. Piombino was soon to become the nerve centre of the defence against fascism, defending itself against a further fascist onslaught in April 1922, before finally succumbing after 1 ½ days of fierce fighting when the fascists, aided by the Royal Guard, were able to capture the offices of the USI.

In July 1922, the reformist general strike to defend ‘civil liberties and the constitution’ marked the final disaster for the labour movement, as the work stoppages were not, and could not be, accompanied by aggressive direct action. The fascists simply ran public services with scabs and made themselves masters of the streets. With the strike’s collapse, the fascists mustered their forces to deal with the last remaining outposts of resistance, one of which, Livorno, succumbed to a force of 2000 squadristi.

Conclusion

So what lessons can we today learn from the arditi del popolo? First of all, we need to learn the benefits of organisation. Like the AdP, we need to form local anti-fascist groups, operating autonomously in their own areas, but gelled together in a national network. These groups should not refrain from applying militant direct action tactics against the likes of the BNP; the only language the fascists understand. We need to avoid the path of reformism, advocated by the recruiting agents of reformist parties like the SWP and destroy, once and for all, the nationalist myth that scapegoats our ethnic communities and which allows governments across Europe to hoodwink large sections of the working class into the belief the root of their socio-economic woes lies elsewhere. To do this, we need to tie the fascists’ agenda to that of the state which supports it, and get across the message that fascism will only ever be destroyed once the state itself is smashed. Only a society run along the principles of anarchocommunism can ever hope to achieve this.

Thanks to Nestor McNab, for his help with translation of parts of this article.

The underground Italian anarchist press inside and outside fascist Italy

Resistance and propaganda to fascism did not begin in 1939, 1936 or 1939. Nor did it consist simply of slogans hastily painted on walls in the dead of night. A powerful anarchist underground press operated in Italy throughout the period of fascist dictatorship and occupation pressing the case for liberation through social revolution. To gauge the extent of the resistance to fascism and Nazi occupation in Italy, here is a review of the libertarian underground press at the time

Voci officina (Voice of the factories)

Underground paper put out by workers of the Turin factory councils, among them the anarchists Michele Guasco and Dante Armanetti. 8 or 9 issues in the first year of fascist terror.

Iconoclasta!

Anarchist review open to all tendencies. Produced monthly in Paris in 1924–5, when together with the Italian section of Rivista Internazionale Poliglotta (International Polygot Review) it ceased publication to produce La Tempra

La Tempra

International anarchist review. Monthly from Paris from 1925–6 (lack of information on his publication in following years)

Lotta anarchica (anarchist struggle)

Published in Paris for distribution in Italy. Subtitled: For armed insurrection against fascism. The editions specifically for Italy were produced in small format, three column

width on thin paper, with 3 to 4 pages that could be included in a letter. Regular publication up till end of March 1931.

Ai Lavatori d’Italia (To the Italian workers)

Milan , October 1943. Small format, 4 pages. The programme of the revolutionary syndicalists of the Unione Sindacale Italiana. For a @socialist republic of syndicates@. Edited by Aldibrando Giovanetti.

Fronte Unico dei Lavatori (United Workers Front)

First of all in pamphlet form, then a paper. 12 pages. Published in the Romagna with the support of the anarchists of Liguria, Tuscany, and Romagna after a meeting in Florence.

L’Adunata dei Libertari: voci dei comunisti libertari (voice of the libertarian communists)

Milan. Underground publication of first 3 numbers., first one appearing 18th June 1944. Small format with 3 columns, 2 pages. Editor was Pietro Bruzzi, arrested, tortured and shot by the Nazis at Legnano.

Il Comunista libertario.

Milan. Paper of the Federazione Comunista Libertaria Italiana. First appeared December 1944. Small format with 3 columns, 4 pages. In March 1945 its second issue appeared, and continued regularly until the end of April 1945, with the final fall of fascism

L’Azione Libertaria

Milan. 5 issues appeared from August to September 1944 in the same format as above papers, and indeed most of the underground press.

Rivoluzione

Paper of the Liga dei Consigli Rivoluzionari (League of Revolutionary Councils) From December 1944 included the programme of the Liga. Composed of communists, anarchists and sympathizers. Second issue appeared in February 1945.

Era Nuova

“Voice of the libertarian communists”. Turin. First issue appeared in October 1944, 2 columns, small format, 4 pages. 2nd issue in November ’44 and third in March ’45.

L’Adunata dei Refrattari.

New York. At the end of ’44 the New York Italian anarchist paper published several supplements aimed at Italy. Thin paper, small format, 2 columns, 8 pages. It was distributed above all by soldiers in the American Armed Forces, despite the American authorities heavily punishing anyone involved in its dissemination. Issue 1 in December ’44 and Issue 3 in March ’45.

Umanita Nova.

Anarchist paper. Genoa. Published just a little before insurrection against the fascist authorities and in preparation for it, 22 April ’45. Small format, 3 columns, 4 pages. Continued numbering from when it was a daily paper published in Milan and Rome and edited by Malatesta in 1920–1922.

Umanita Nova

Anarchist paper. Florence. Appeared 24th September ’44, without the authorization of the Allied authorities. The printer Lato Latini was arrested and condemned to 1 year in prison. In February ’45, after a suspension of several months, restarted on a monthly basis with Umanita Nova; Fiorentina (Florentine)as subtitle and with announcement that the Federzione Anarchica Italiana was being formed. Prematurely as it happens, as the FAI was now constituted until the Carrara conference in September 1945

Auf Ruf: Offizere, Unteroffizere und Mannschaften der Deutschen Wehrmacht. Appeal in German put out by Milanese anarchists to the German armed forces in March 1945

Pamphlets of Risveglio-Reveil.

Published somewh ere in Switzerland. After the suppression of this Swiss paper, small pamphlets of 16 pages on a monthly basis (half in Italian, half in French) appeared from September 1940. Changed title several times, but continued with a surprising regularity up until the end of December 1946 with no.147

La Rivoluzione Libertaria.

Organ of the libertarian groups of southern Italy. Bari. It was the first official anarchist paper since the fascist takeover. Initially it appeared on 30th June ’44 without Allied authorization, and was distributed secretly until 16th November ’44 when it was legalized.

L’Idea Proletaria

Milan. 2,000 copies printed. Edited by Mario Perelli with a vague , gradualist line. Came out from Autumn ’43, with a short life.

Sempre Avanti!

Anarchist paper secretly printed and distributed in Genoa.

Il Seme Libertario

Single issue paper of the Federazione Comunista Libertaria of Livorno. Appearing semi-clandestinely, because of persistent censorship of Allied authorities in summer 1945, with false indication of its address (Rome)

Aurora

Libertarian communist (Ravenna). Paper of the Romagna anarchists,; its first 2 issues appeared clandestinely.

Il Partigiano

Political weekly of the partisans of liberty. Rome. Anti-authoritarian political line , edited by Carlo Andreoni, libertarian Marxist militant of the Unione “Spartaco”. Underground publication from ’43, continued up until ’45, probably tolerated by the Allied authorities because not directly anarchist, but suspended for 4 issues in march ’45, for “having published forbidden notices of the Allied military censorship”.

La Montagna

Libera voce clandestine. Rome. Paper of “a group of partisans of the North” taking the place of Il Partigiano during its forced suspension. On its list of @friends and neighbours@ was Umanita Nova.

[1] Williams L. Proletarian Order 1975

[1] Williams L. Proletarian Order 1975

[2] Rossi, A. The Birth of Fascism 1938