Angry Education Workers

Towards a Revolutionary Union Movement

September 21st 2025

Characteristics of Revolutionary Unions

Heterodox Strategy and Tactics

Introduction

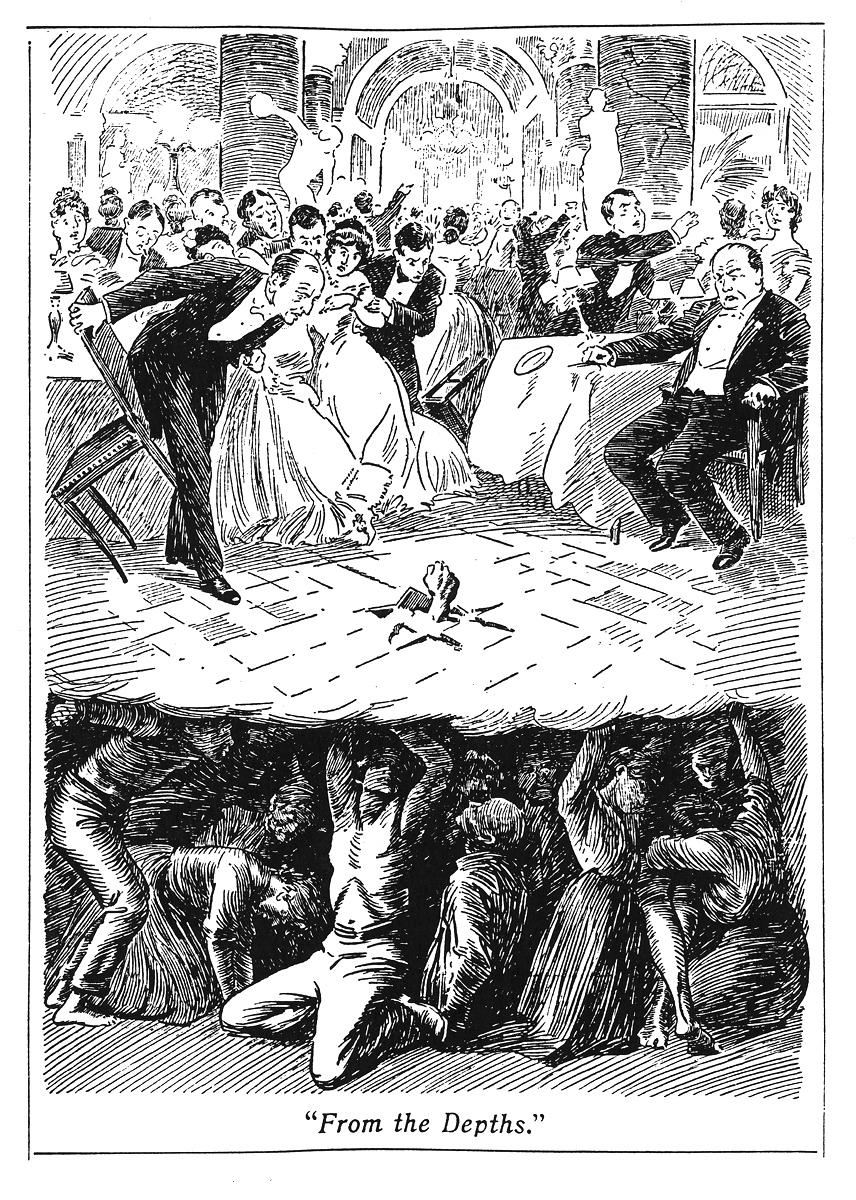

The working class today stands at a crossroads amid deepening, interlocking crises. With education workers leading the way, the labor movement is in the early stages of revitalization—the awakening of a sleeping giant. For all their admirable successes, though, the prominent trade unions themselves have historically played a key role in constructing divisions between themselves and the lower strata of the proletariat. The most obvious example of this is the US craft union movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries embodied by the American Federation of Labor (AFL), which excluded “unskilled” workers, segregated its Black members, tried to keep women out of the workforce, and lobbied for anti-immigrant legislation (while more than half of the members were themselves immigrants). Christian Frings with the German leftist newspaper analyse & kritik dives deeper into this history:

Parallel to the introduction of social insurance, the establishment and legal protection of trade unions developed as the representation exclusively of this part of the proletariat, the “wage laborers”, who can proudly point out that they live from “their own hands’ honest work”. In the early days of modern mass trade unions after the largely spontaneous Europe-wide strike wave between 1889 and 1891, they were referred to as “strike prevention associations” by more critical minds in the workers’ movement. This was because the monopoly granted to them by the state and capital on the form of struggle of the strike in conjunction with peacemaking collective agreements was intended to put an end to the wild goings-on of work stoppages, factory occupations, sabotage and riots on the streets. Although it took two world wars, fascism and the Cold War for this model to become effectively established in the Global North, it still works quite well today with the very moderate use of strikes.

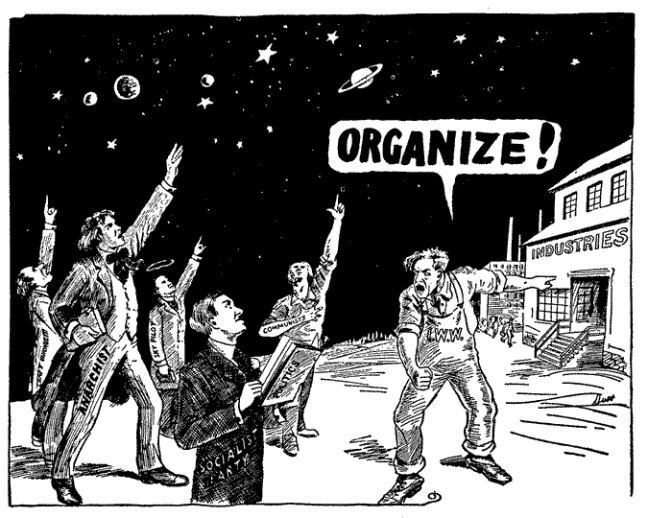

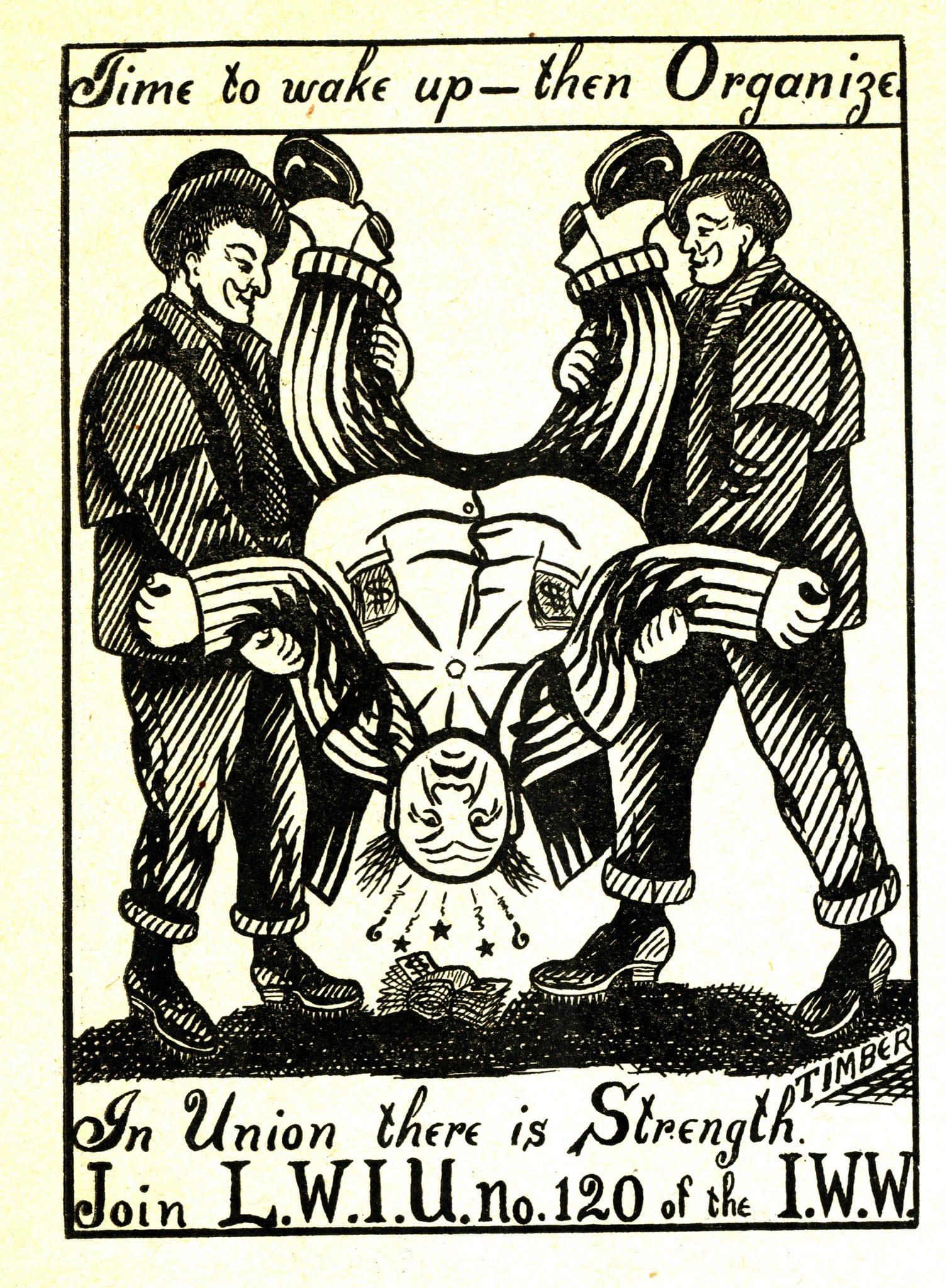

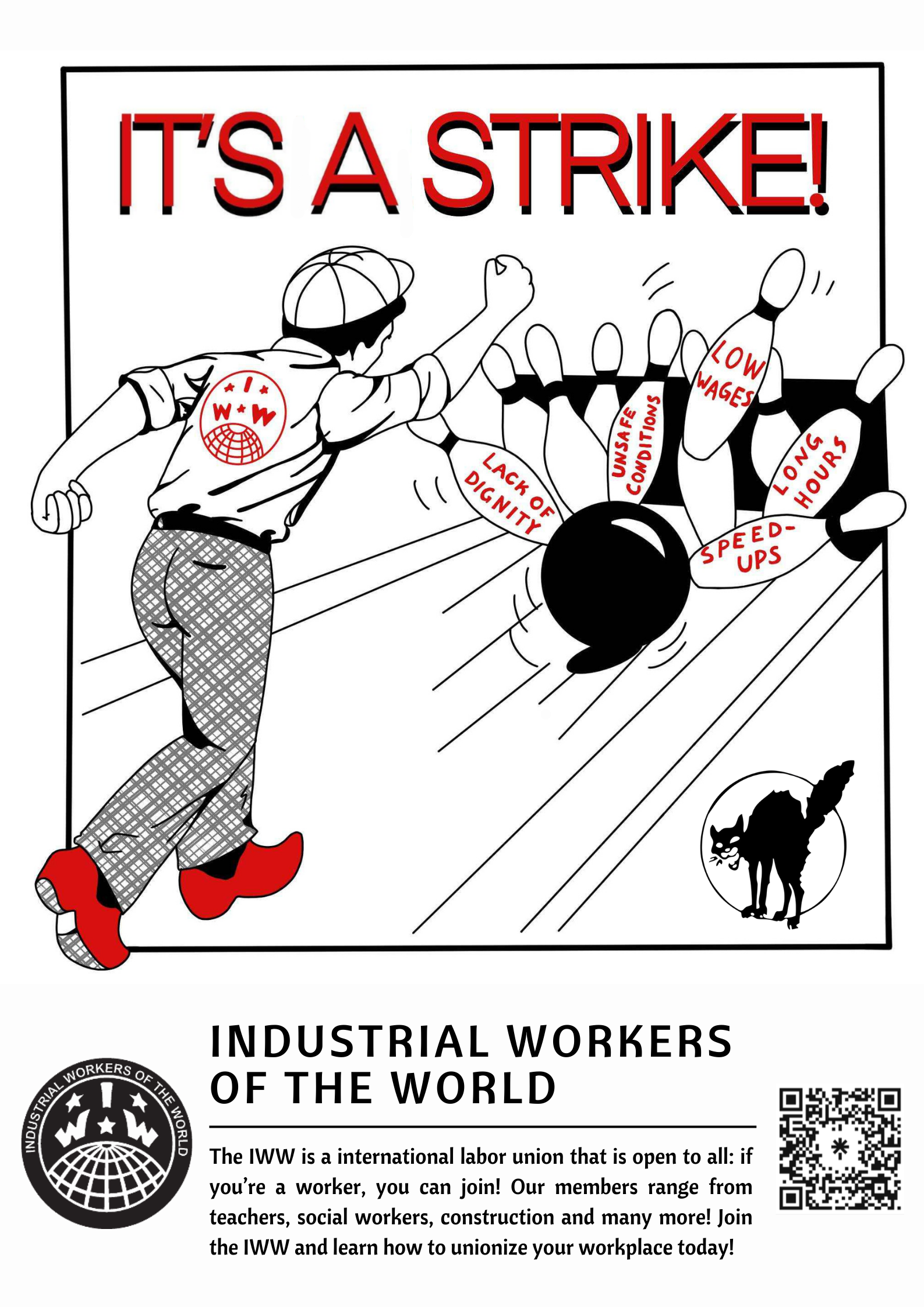

In the US, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) emerged in 1905 in opposition to these exclusionary unions and is often mentioned alongside the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) as a quintessential example of revolutionary unionism. But these unions were usually crushed to earth during WWII and the Cold War—the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), for example, was strong-armed into expelling communist led locals in 1941. The IWW, already hit hard in the First Red Scare, had membership in its organization criminalized during the Second Red Scare. In Spain, the CNT was outlawed during the tenure of the fascist regime of Francisco Franco.

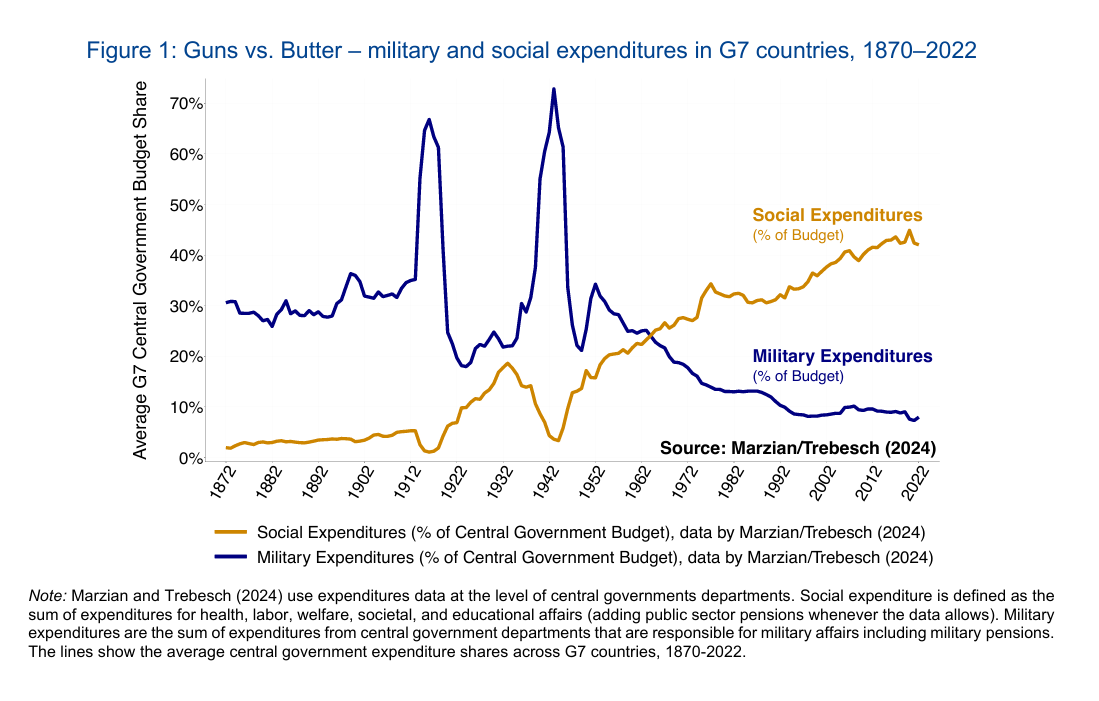

Simultaneously, the governments of the Global North contained proletarian resistance by investing in social welfare and encouraging the growth of trade unions with moderate and conservative strategies—often labeled as business unions. Some workers attempted to break out of their containers starting in the late 1960s—such as the League of Revolutionary Black Workers in the US, the workers’ councils in Italy, and the insurgent workers of May ‘68 in France. The ruling class unleashed savage repression and economic reforms that defeated these movements, scattering revolutionary workers. Moderate union leaders and staffers totally unprepared for the Neoliberal war of attrition that has destroyed most of the labor movement.

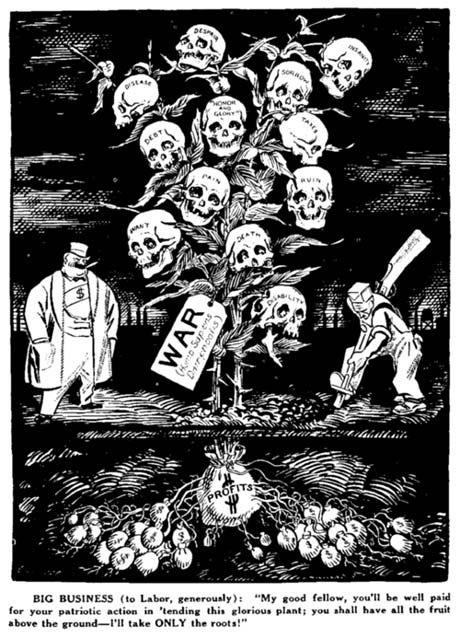

The remnants of the old labor movement are often conservative and complicit in atrocities committed by our military-industrial complex. A massive portion of the US labor movement was built during WWII at munitions factories. Throughout the entire Cold War, the AFL, and then AFL-CIO, collaborated with the CIA in the overthrow of democratically elected governments in Latin America and beyond. Unsurprisingly, these union leaders who were willing to sell the global working class down the river then turned around and did it to their own memberships. Even today, most union leaders in this country, with the exception of some like Shawn Fain, demonstrate little regard for the rank-and-file.

So far, the response to union conservativeness and weakness on the shop floor from the 1980s until today has been what Joe Burns, author of Class Struggle Unionism, calls “labor liberalism.” Unions such as the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) and workers' centers are prominent types of labor liberal organizations. They were a more progressive response to business unionism, but remain ultimately fixated on “choreographed” labor actions like one day strikes and staff heavy organizing that maintains the containment of proletarian struggle. Rather than a step forward, labor liberalism represented a failed compromise between business unionism and revolutionary unionism.

Both remain insufficient vehicles for the revolutionary sections of the proletariat. We need an explicitly revolutionary union movement that can take the offensive against capital, one that can rupture the political and legal structures that act to stifle proletarian resistance. Accomplishing this will take situating ourselves within an ecosystem of proletarian organization that broadly encompasses three categories: production, insurrection, and reformation. There are many useful models from the past we can draw from, but for all the continuities between now and the historical situations that birthed the revolutionary union movements of the past—such as the early IWW, CNT, or Swedish Workers' Central Organization (SAC)—there are just as many differences. Our task, as those of us who would call ourselves revolutionary unionists, is to articulate a concrete, specific vision of revolutionary union strategy that wins the support of large masses of the working class.

Our aim is to define some key guiding characteristics that a union must possess to be part of a revolutionary union movement. In addition, we will try to sketch a broad strategy that can transcend the pitfalls previous generations of revolutionary union movements have fallen into. At the front of our minds is what might be called the “syndicalist cycle.” This describes the tendency of revolutionary unions to get marginalized within the labor movement in times of labor peace between workers and capital, like the Postwar “Golden Age of Capitalism.” Revolutionary unions that ride the wave of reform in order to stay relevant then begin to degenerate into business and labor liberal union practices. The SAC and French General Confederation of Labor (CGT) are emblematic of this cycle. Somehow, we must overcome this dilemma and build a revolutionary union movement that can do both. In Guerilla Warfare, one of the three main lessons of the Cuban Revolution that Ernesto Che Guevara identifies is that “It is not necessary to wait until all conditions for making revolution exist; the insurrection can create them.” Whatever his individual flaws, perhaps this conclusion of his can guide us.

Hopefully, this can serve as the roughest of drafts for a blueprint to organize revolutionary unions—or transform existing reformist unions into revolutionary ones. This text is the result of conversations raised within the labor movement and various worker-centered communities, such as: union bodies of active organizers within the IWW, individual labor organizers in various mainstream unions, internet forums for union workers, radical political collectives, and social spaces for education workers. This text is also meant to address key questions posed by Class Struggle Unionism: “what type of workers’ movement would it take to blockade workplaces, violate injunctions, and engage in outlawed solidarity tactics? How can we pick some battles and move them beyond the existing system? Can this be done in existing unions or will it require new ones, or a combination of both?”

We think the answer is a revolutionary union movement. With this in mind, we posed three questions:

-

Do we need a revolutionary union movement? What would a revolutionary union movement look like? How can we build one?

-

How can we build unions that can effectively and democratically channel these already existing, escalating working class struggles towards revolutionary action? Action that the employing class can’t redirect towards other ends.

-

How can we articulate a concrete, specific vision of revolutionary union strategy that really captures the hearts and minds of masses of working people? What administrative capacity do we already have to accomplish this, and what capacity do we need to build? How do we sustainably mobilize our resources in this direction?

To the questions of whether or not we need a revolutionary union movement: the answer was overwhelmingly yes. Now, we offer up this text that weaves together our thoughts for critique, discussion, and circulation among worker-organizers in the IWW and beyond. We must emphasize that this text represents the beginning, not the end, of the conversation.

Dual Power

The goal of a revolutionary union movement is to help bring the proletariat to the moment of taking power over society and completing the transition out of capitalism. In other words, a situation of dual power. Originally coined by Lenin to describe the period between the February and October Revolutions when the moderate Provisional Government and Petrograd Soviet struggled for control of the state, it has informed every generation of revolutionaries since. A revolutionary union movement helps create a revolutionary counter-power to the capitalist class. One that ends with its final overthrow. We are the ones who will lead the expropriation of the means of production from the capitalists. Afterwards, the revolutionary union movement will become the organizational expression of workers’ self-management of production in all industries and workplaces. Democracy would finally extend into the economy, with all production serving society as a whole rather than a few at the top.

Our task during a moment of revolutionary rupture is the conquest of the means of production, globally. No other fundamental, revolutionary transformation of society is possible without this happening. The revolution will wither and eventually die. Worker control over production gives the people the leverage to force the authorities to obey us. During the Russian Revolution, the Provisional Government did “not possess any real power, and its directives are only carried out to the extent that it is permitted by the Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, which enjoys all the essential elements of power, since the troops, the railroads, the post, and the telegraph are all in its hands”. By controlling key sites of production and logistics, the soviets could flex political power enforced by the large number of soldiers who’d defected to the revolution.

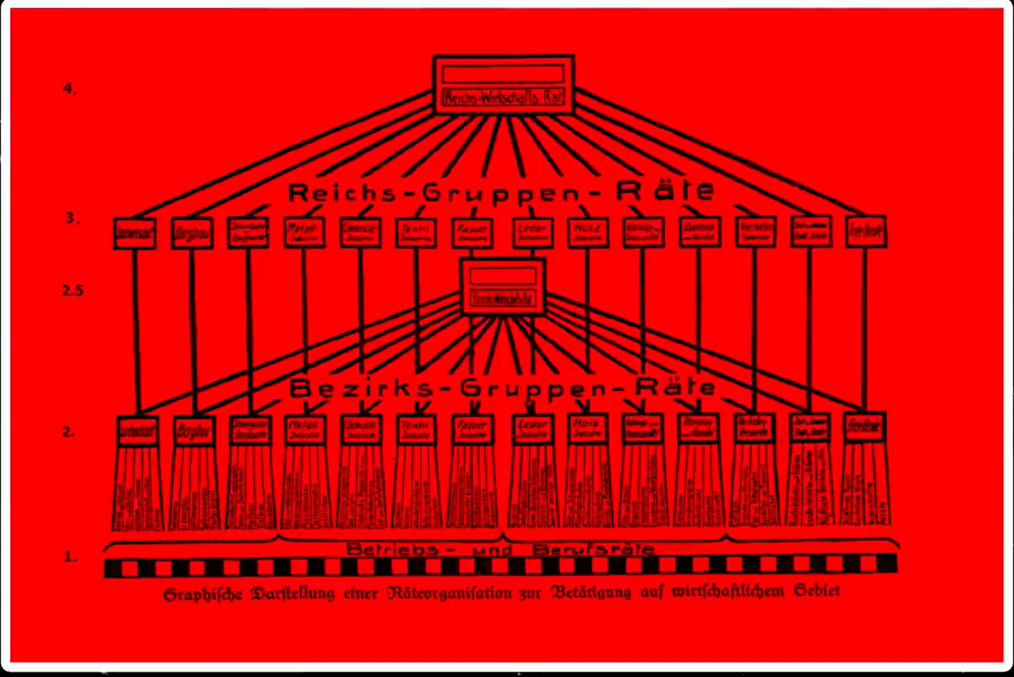

This brought the workers' council—an independent, directly democratic working class institution for economic and political decision-making born during the 1905 Russian Revolution—onto the world stage. Workers’ councils proliferated across the Russian Empire, Germany, and much of the rest of the world between 1917 and 1927. Workers’ councils also spawned numerous militias that could fight to defend revolutionary gains. Revolutionary unions must be able to lay the infrastructure for the rapid spread of workers’ councils and popular assemblies in a situation of dual power.

As workers occupy their workplaces and begin to run them, a tension between socialization and nationalization will emerge. Using the state to take over and plan production to meet society’s needs seems like the quickest way to begin building a new economic system. But the experience of the proletariat during the Russian and German Revolutions should caution us against this. Writing in 1930, the Kollektivarbeit der Gruppe Internationaler Kommunisten (GIK) reflected on the legacy of the Russian Revolution in a text titled “The Workers Councils as Organisational Foundation of Communist Production”. The Bolsheviks, facing economic chaos and counter-revolution, used the coercive power of the state to wrest “the day to day management” of industries from the workers’ councils with the Decree on Workers' Control. This decision “embroiled” them “in contradictions with the masses of workers” that deformed the process of socialist construction. It led them down a pathway that departed from their own Marxist analytical foundation. Friedrich Engels made this clear in Anti-Dühring:

The modern state, whatever its form, is an essentially capitalist machine, the state of the capitalists, the ideal aggregate capitalist. The more productive forces it takes over into its possession, the more it becomes a real aggregate capitalist, the more citizens it exploits. The workers remain wage workers, proletarians. The capitalist relationship is not abolished, rather it is pushed to the limit...State ownership of the productive forces is not the solution of the conflict...This solution can only consist in actually recognising the social nature of the modern productive forces, and in therefore bringing the mode of production, appropriation and exchange into harmony with the social character of the means of production. This can only be brought about by society’s openly and straightforwardly taking possession of the productive forces, which have outgrown all guidance other than that of society itself.

Wage labor and commodity production continued under the USSR. Its product was somewhat more evenly distributed than in capitalist societies through the machinery of government. People did not have to worry about unemployment or homelessness, and had access to broad social benefits like free healthcare and education. But that does not change the fact that nationalization in the USSR failed to fundamentally change the relations of production. Worker autonomy is integral to socialism.

Lenin himself recognized—in both State and Revolution and “The Dual Power”—that the state machinery under capitalism cannot be copied and pasted to implement socialism. He looked to the example of the Paris Commune as a model. That “essence of the Paris Commune as a special type of state” meant that power was “based…on the direct initiative of the people from below, and not a law enacted by a centralised state power.” Dual power required “the replacement of the police and army, which are institutions divorced from the people and set against the people, by the direct arming of the whole people.” Workers and peasants would replace the basis of the “officialdom, the bureaucracy” with “the direct rule of the people themselves or at least placed under special control…subject to recall at the people’s first demand.”

This Lenin had seemingly vanished under the stresses of the Russian Civil War. His fixation on the state machinery led him to adopt practices that diminished the liberatory potential of the Russian Revolution, regardless of his personal intentions. We must also acknowledge the nearly impossible situation he and the Bolsheviks faced after the October Revolution. The failure of the German Revolution in 1918 and 1919 loomed large over the early Soviet Union. Cut off from the industrial heartland of Western and Central Europe, the Soviets had to go it alone. While the Russian Empire had some of the most advanced industrial enterprises concentrated in its cities, its place in the capitalist world system of the time relegated the vast majority of its population and territory to suffer under an underdeveloped, semi-feudal agrarian economy. Later revolutionary upsurge in the Global North—whether Anarchist, Marxist-Leninist, Maoist, Autonomist or whatever—also failed. Faced with a (mostly) united NATO bloc led by the US, survival was an immediate and overriding need. Building socialism in such circumstances is a nightmare. Of course it all failed. Our proletarian revolution can only be global, or it will not be.

History also shows us that nationalization can co-exist with capitalism fairly easily. Most capitalist countries have nationalized one or more of their industries over time, especially during the Postwar Period, when employers needed to make concessions to avoid revolution. In addition, nationalization retains the hierarchies of capitalist production, except that workers and management now report to an “aggregate capitalist” in the form of the state. Under Neoliberalism, the working class has witnessed how swiftly governments can privatize whole industries, such as the railroads in the UK, public education in the US, and state-owned mining companies in the Ukraine. In the USSR, the transition back to capitalism was as simple as selling off all the industries to mobsters and the former Communist Party officials who had once managed them. This disastrous privatization is the origin of Putin and Russia’s famous oligarchs. Nationalization, then, is not enough to dismantle the capitalist relations of production.

Nationalization is still preferable to private ownership. If the state represents an “aggregate capitalist,” it reduces the number of enemies we face in a revolutionary upheaval. A revolutionary union movement, then, could resolve the contradiction between socialization and nationalization by expropriating the public sector itself. Public sector workers would seize the socially beneficial elements of the state so it can be governed directly by workers and community members working together democratically. Meanwhile, the revolutionary unions would smother the violent and authoritarian parts of the state—such as the prison-industrial and military-industrial complexes.

The best tool the revolutionary unions have to invoke this state of dual power is the general strike. A general strike is when most, or all, workers in an industry or geographic location refuse to work until their demands are met. General strikes frequently feature insurrections against the police, workplace occupations, and the creation of directly democratic bodies run by and for workers. For example, the Seattle General Strike of 1919 resulted in the working class essentially running the city for the duration of the strike: “The strike was not a simple shutdown of the city. Instead, workers in different trades organized themselves to provide essential services, such as doing hospital laundry, getting milk to babies, collecting wet garbage, and many other things”. Striking workers and their communities understood their actions as preparation to self-manage the economy and society. Their idea of what the 1917 Russian Revolution stood for inspired them to try and spread what was still an international working class revolution in the wake of WWI.

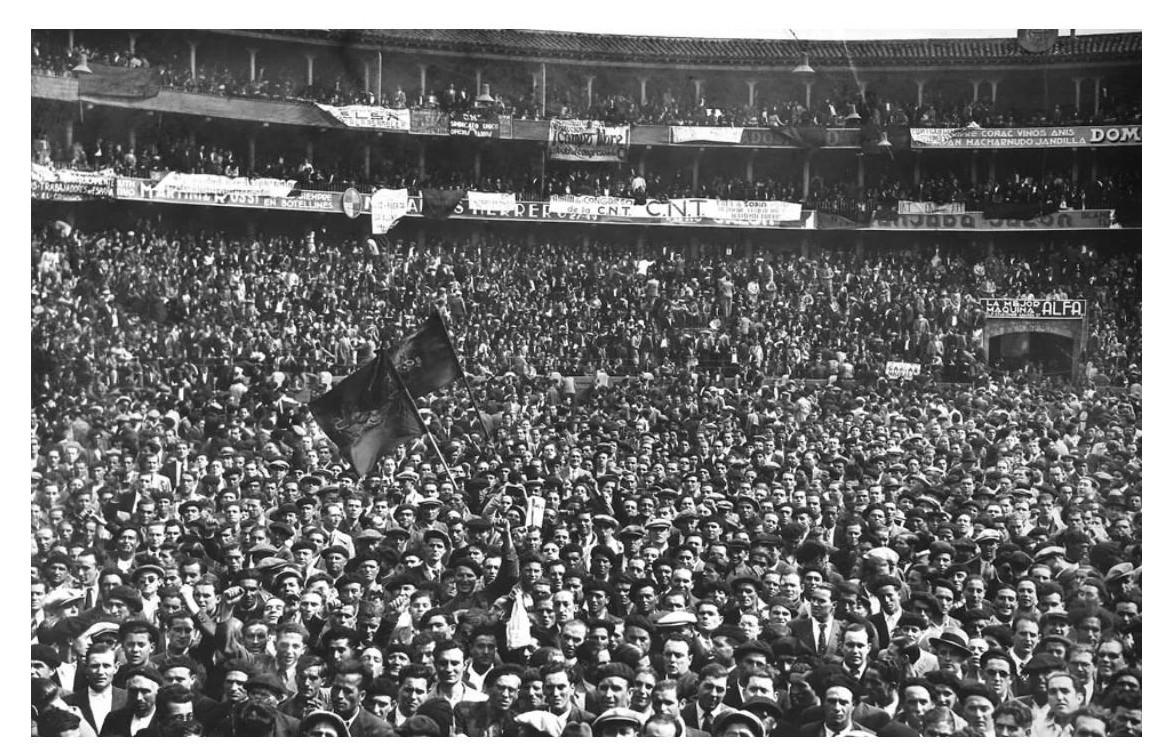

The Spanish Revolution, coinciding with the Spanish Civil War of 1936–9, represents perhaps the best example of a revolutionary union building dual power and leveraging it during a societal rupture. United with anarchist militants, the CNT, a revolutionary syndicalist Spanish union, through robust worker and peasant organizing spanning decades, defeated Francisco Franco’s fascist coup across much of Spain. Otherwise it’s unlikely the Spanish Republic would have lived at all. These same workers and peasants then, temporarily, built a new society based on confederal communist principles.

But much has changed since 1917–1923, 1936, or 1968. Our challenge today is to map out a strategy that leads to a situation of dual power. A large part of that work is building concrete, autonomous working class institutions. Many formations, both formal and informal, are already engaged in constructing them—labor unions, tenant unions, mutual aid groups, political collectives, and organizations trying to mix these currents like Black Rose Anarchist Federation. We encourage everyone interested in the revolutionary transformation of society to read the first edition of their program, released last year. It impressed seemingly every serious revolutionary organizer who encountered it.

With all that said, we are writing for those who have taken the path of revolutionary union organizing. Where does a revolutionary union fit in this ecosystem? What does a revolutionary union actually look and act like?

Characteristics of Revolutionary Unions

There are nine intersecting characteristics we have identified that set revolutionary unions apart from liberal or progressive unions. In addition, a few themes underlie each of the features of revolutionary unions, such as worker solidarity, militancy, the need for working class self-leadership, membership development through training and political education, and above all: courage. We must mean it when we proclaim that “the emancipation of the working class must be the work of the working class itself.”

Against Class Collaboration

Revolutionary unions reject collaboration with the employing class. Looking at the IWW constitution, this rejection of class collaboration is literally the first sentence of the preamble: “The working class and the employing class have nothing in common.” Seeking labor peace is futile. Conflict between employers and employees is fundamental to capitalism, there is no resolving it without overthrowing the system entirely. The much vaunted social democratic compromise between unions and bosses during the “Golden Years of Capitalism” lasted a maximum of barely 35 years. By 1981, the rich had decided the working class was too powerful and well-off, and that it was time to go on the offensive to change that. Our present situation is the result of more than 40 years of class war waged from above. Why would we collaborate with a class of people who rob us for as much as they can get away with?

To use a cliche, the abuse and exploitation are a feature, not a bug. Forget all the nonsense most economists spew, it’s nothing more than noise that obscures the reality of our situation as workers. A proper analysis of societal relations under capitalism reveals that at its core, the relationship between capital and labor is one of domination and subservience. Joe Burns concisely cuts to that core: “But what is wealth? It is not something you can hold in your hand. It is a social relationship—the ability to command others. It is power.”

Instead, we must remain steadfast and open about our objective, which is the overthrow of capitalism and the establishment of industrial democracy (AKA economic democracy). Industrial democracy is socially useful production by and for “associations of free and equal producers”. Our revolutionary unions “must challenge the very basis of this unequal system,” and build the organizational capacity to “take on capital on a grand scale”. We don’t want a fair day’s wage for a fair day’s work, we want wage labor abolished entirely. We know better than to expect those with power to give it up willingly, they will fight us at every turn. Therefore, we must think and act strategically.

The capitalists act as a class, even if they’re divided along factional lines. So should we. Our role is to set off an ever-expanding struggle across the industries of capitalist society. For example, one of the early IWW’s affiliates was the Lumber Workers Industrial Union, which used direct action tactics to exercise “job control.” Across much of the Pacific Northwest of the US, IWW union halls effectively took control over the hiring of workers away from bosses—and shut out anti-union workers entirely. Once we take one thing from the employing class, we take another, and another, until we who have been nothing for millenia are everything once again. A modern equivalent would be an apparatus of “professional education” controlled by an industrial union administration of education workers in schools, daycares, libraries, museums, expositions, archives, galleries, and art facilities.

Through direct action we can construct an association of free and equal producers within the shell of the old society.

Prefigurative

The rich history of anarchist labor organizing produced the theory and practice of prefiguration. Prefiguration is based on the philosophical stance that means and ends cannot be separated: that the way you choose to achieve your goals will determine what you actually accomplish. Past revolutionaries often expressed this idea with the phrase “we are building the new world in the ruins of the old.” Revolutionary unions are aware of this and act accordingly. At every turn, revolutionary unionists should embody today the societal relations we aim for in the future, when capitalism is no more. When we act prefiguratively, we emphasize building the skeletal and nervous systems of a new, liberated, social body. Then, when the revolution comes, we are already prepared to seize the moment during a situation of dual power and achieve a true transformation of society.

Prefiguration is an excellent framework for understanding how social structures shape individual and collective actions—which helps take the focus off of an individual’s personal character and intentions. Revolutionary unions recognize that all individuals and groups are flawed, and take steps to develop egalitarian systems that facilitate working class self-leadership. Our institutions need to horizontally distribute power and decision-making as much as possible. Here, we can learn from Errico Malatesta, a militant of the international anarchist workers’ movement of the early 20th Century, and one of the first to articulate a theory of prefiguration. He advocated a “government by everybody” that is “no longer a government in the authoritarian, historical and practical sense of the word.”

Bickering contests dissecting the character and intentions of past revolutionaries and labor leaders are counterproductive. These sectarian debates distract us from the real work of building towards revolution. We can collectively deconstruct these debates by analyzing the concrete effects of decisions and structures instead. Commenting on the Bolsheviks in a 1919 letter, Malatesta wrote that they:

are merely marxists who have remained honest, conscientious marxists, unlike their teachers and models, the likes of Guesde, Plekhanov, Hyndman, Scheidemann, Noske, etc., [the prominent social democratic leaders of their era] whose fate you know. We respect their sincerity, we admire their energy, but, just as we have never seen eye to eye with them in theoretical matters, so we could not align ourselves with them when they make the transition from theory to practice.

Malatesta demonstrated the ability to engage in principled, nuanced, and respectful criticisms of the political tendencies he disagreed with.

If someone is a worker and willing to respect members of all backgrounds, they should be welcome. Forty percent of the teachers who walked out for the Red for Ed strikes of 2018 voted for Trump in the 2016 election. The revolutionary union movement encourages plurality of thought while engaging in collective education. Our present choices about how to handle disagreement and conflict—both internally and between organizations—will determine the type of society we replace capitalism with. We must use internal political education and persuasion to help workers begin to overcome the baggage we all carry under capitalism. “Beyond ‘Fuck You: An organizer’s approach to confronting hateful language at work” provides a model of what this looks like in one-on-one and small group settings. As we grow, we have to incorporate this model into all of our organizational infrastructure. Whatever our other disagreements about politics are, we must all commit to structuring our unions directly democratically.

Here we must raise a criticism of those who pursue democratic centralist lines of organization. Democratic centralism originates with the Bolsheviks, representing an attempt to fuse democratic deliberation with highly centralized authority. It’s true that “when leadership is not openly acknowledged, it operates unofficially and informally, so that the members have no effective way to hold it responsible”. Feminist organizers termed this phenomenon the “tyranny of structurelessness.” Informal cliques of power brokers are corrosive to democracy. While we agree with these critiques, and also understand the need for maximum unity among the workers, but democratic centralism fails to solve the problem. By centering a cadre of leaders that are supposed to be in unity with the working masses, organizational hierarchies can easily become entrenched. This practice, this means to an end, usually leads to deepening divisions between the rank-and-file and the leadership that reproduce capitalist social relations inside our organizations.

While proponents of democratic centralism acknowledge the tension between democracy and central authority, they stress the “crucial role of organizational leadership”. This makes them, in their own words, vulnerable to “commandism” and “the development of personality cults” whenever leadership fails to properly synthesize their own “theoretical and practical experience and mature political judgment” with the desires and needs of the membership, as well as those of the broader proletariat. Intentions matter little here, since embedding a hierarchy between leadership and membership will lead to the erosion of internal democracy, with the organization increasingly dominated by cliques distant from the experiences of regular working people. The history of most communist parties and trade unions should teach us that a democratic centralist line rarely remains democratic in any meaningful way. Democratic centralism, then, trends towards a “monolithic unity” of action that stifles the opinions of an electoral minority. Full consensus on contentious issues within a revolutionary union is impossible, so decisions by simple majority or supermajority will be necessary most of the time. The problem begins when “unity of action” binds the right of the minority to protest and to act in an autonomous manner.

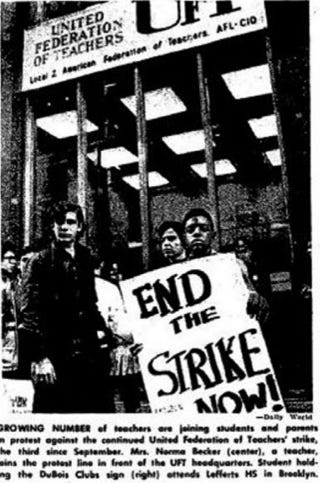

Prefiguration as an organizational philosophy, on the other hand, opens space for us to critique past social and revolutionary movements without picking apart specific individuals who many of our fellow workers might admire. Let’s examine two concrete examples from within the teacher union movement. New York City’s United Federation of Teachers (UFT) has been dominated by the Unity Caucus since the union’s formal organization in the 1960s. Its leadership constantly undermines any attempt at dissent or independent action by sections of the membership. When UFT Education Support Professionals (ESPs) formed the Fix Para Pay Slate and elected a dissident Chapter Leader, Migda Rodriguez, Unity leadership effectively made it impossible for her to do her job. Our revolutionary union movement must embrace open dissent. Especially after the official vote has been taken.

It is tempting to hide our internal disagreements to present a favorable view of the union to the public, but setting up a cadre of leaders that exists above the membership prefigures a hierarchical organization that reproduces capitalist social relations. Prefiguration helps us understand that this false unity is counterproductive. Only through a combination of public-facing and internal deliberation and dissent can we give birth to truly revolutionary unions. The contrasting approaches of the UFT and the Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) from 1968 to 1971 provides an illuminating example. In 1968, the UFT—under the ironclad leadership of Albert Shanker—launched the Ocean Hill-Brownsville Strike against an experiment in community control by Black neighborhoods over their local schools. Regarded by Black New Yorkers, most Black teachers, and leftist teacher unionists as a “hate strike”, the UFT won at the cost of the trust of the families and students they served.

In Chicago, the CTU made a similar mistake, also in 1968, by ignoring the demands of the significant Black minority of the union’s membership and the wider Black Community. Nearly half of Black teachers crossed the picket line. These members were maligned as traitors and scabs undermining the strike by expressing their discontent with the white majority establishment of the CTU. A revolutionary unionist perspective emphasizes how publicly registering their anger with the union laid the foundation for lasting change. Groups such as Concerned Parents, Operation Breadbasket, and the Black Teachers Caucus in the CTU reformed it and Chicago Public Schools. These Black led groups exercised a leverage in the CTU that Black people could not wield within the UFT. With concrete power inside the union and militant community confrontations with white school administrators, the police, and white teachers over racism, the CTU and Board of Education hired black teachers, added Black history and culture courses, and gradually certified Black substitute teachers. Leaders like Timuel Black and hundreds of Black teachers prevented a potentially fatal split within the CTU and raised the percentage of Black teachers and administrators to significant minorities or majorities by 1980. When the CTU struck again in 1971, Black teachers proved overwhelmingly supportive. It is no coincidence that the UFT is still dominated by an anemic, anti-democratic leadership while the CTU has become a model for unions everywhere.

A revolutionary union movement must be led directly by its membership. How can we cultivate this working class self-leadership on an organizational level?

Democratic and Inclusive

Democracy is the lifeblood of the workers’ movement. Without it, the movement dies, as we have seen with the history of the business unions since the mid-20th century. This is just starting to change with the triumph of democratic reform slates such as Caucuses of Rank-and-File Educators (COREs) in a growing number of teacher union locals, Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU), and Unite All Workers for Democracy (UAWD) in the UAW. So far, the results have been stunning and historic victories for the unions who have embraced increased internal democracy and an inclusive organizational culture. Unions who dig in their feet to stick to their conservative strategies continue to shed members and render themselves irrelevant. Revolutionary unions take it further and commit to direct democracy. We reject the slandering of our unions as outside “third parties” by employers, because we are the union!

Directly democratic union structures neutralize the ability of employers and the government to crush unions by singling out individuals within the union for retaliation. Even if they lock up the so-called “leaders” of an illegal strike, others will immediately step up to take their places. These democratic practices spread the burden of illegal strikes, workplace occupations, and sabotage across a greater number of people, both within the affected workplaces and the union as a whole.

Besides internal governance structures, a revolutionary union movement forges an inclusive, accepting organizational culture that seeks to center the needs of the most oppressed and marginalized parts of the proletariat. Revolutionary unions go out of their way to engage in outreach to these fellow workers. A concrete step in the right direction unions can make in the short term is investment in translation resources for migrant workers. Regular rotation of positions ensures that members of all backgrounds have access to leadership development. Key to successfully building an internal organizational culture is the efficient delegation of union tasks. We can’t expect everyone to devote hours of time every week or month to unpaid union work. Break tasks down into small enough parts that any member, especially newer ones, can complete them quickly and easily. Tasks should be categorized so that it’s clear to worker-organizers approximately how much time each type of task will take. That way, individuals can take on the exact number and kind of tasks that they can handle.

Democracy entails internal accountability systems that can process conflict equitably and in just ways that push aside punitive measures as much as possible. These practices must respect the due process of all stakeholders. There are more than enough unions dominated by cliques of self-serving officials. There are enough weirdo left-cults plagued by constant purges, scapegoating, and abusive leaders. The bosses’ control of the relations of production is the bedrock of capitalist exploitation and despotism. To attack our subjugation at its source, we must encode egalitarian principles and ironclad solidarity into the DNA of our fledgling revolutionary union movement at every stage of its development. Then, with every struggle we enter into with the employing class, we must continually transform production to be more egalitarian and free at every opportunity we get (or make) through direct action.

Militant

A revolutionary union movement must reject service models of labor organizing that position workers as the beneficiaries of certain exclusive perks. Not only does this make it easy to paint the labor movement as a special interest group separate from the rest of the working class, it does little to build real worker power. Collective direct action is the only way to demonstrate that the means of production are in our hands, and that without our labor nothing in society can function. Direct action is also an opportunity for shared learning that prepares us for the conquest of the relations of production during dual power and the transition out of capitalism. We come to understand that we are not helpless cogs in the machine, but the movers of the immense machines that we can paralyze, transform, or smash if we so choose. More, we hone our ability to cooperate and empower ourselves to take greater control over our own lives, filling us with the confidence to demand the dignity and fulfillment we deserve.

Our revolutionary unions must take bold initiative when other unions can’t or won’t. In the battles of the class war when we confront our employers head on, a revolutionary union movement is the vanguard formation. We take the fight to the bosses and their enforcers—giving and taking the hardest hits to open space for the entire proletariat to struggle autonomously for its own interests. In an increasingly repressive political and legal environment, we can look to our ancestors’ for guidance. The AngryWorkers political collective argues that the strikes preceding WWII “repeatedly opened up spaces for other ‘poor people’ and offered opportunities to fight for their interests even without their own productive power, to break out of the loneliness of courtrooms and the clutches of a paternalistic administration of poverty”.

We are undeterred from going beyond wages and conditions to fight wider political battles through collective direct action, as well. From this point of view, a contract is a mere piece of paper. Bosses break the terms of labor contracts all the time. The right to strike is in our hands, no matter what the law or a contract says. Obviously, that doesn’t mean we should be reckless. People’s lives are on the line. But a revolutionary union that is afraid to break labor law is not a revolutionary union at all. We cannot prioritize our treasuries or liberal notions of respectability over direct action. When it comes to maintaining the class hierarchy, capitalists are always willing to set aside the law. Fascism, for example,represents the logical conclusion of capitalist dictatorship in the workplace and colonialism. Joe Burns argues that asserting the right to strike requires “a wholesale repudiation of existing labor law, a rejection of employer property rights, and a commitment to organize the key sectors of the economy through militant tactics”. It is the responsibility of a revolutionary union movement to discern these strategic needs and to democratically determine what direct actions to take.

Relying on the legal system to tip the balance of power in our favor is a dire mistake, even when it goes our way in the short term. A revealing case study is the outcome of the 1974 Hortonville Teachers' Strike, a labor struggle in a rural Wisconsin town. Taking place in the context of the backlash by the “Silent Majority” to the Civil Rights, Black Power, and anti-War Movements, the strike turned violent. Unemployed men formed vigilante squads to harass and attack strikers and their supporters. The striking teachers sought support from the state NEA affiliate, the Wisconsin Educational Association Council (WEAC), which called for a vote to approve a one day state-wide sympathy strike with the Hortonville teachers. When the vote failed badly, the WEAC turned to legislative action. They succeeded in getting a law passed that provided teachers’ unions with “compulsory interest arbitration” that improved their ability to secure contracts without striking. However, Eleni Schirmer, a researcher at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, argues that “this calculation…it failed to develop stronger forms of labour organising – workers’ power to…develop widespread solidarity with other workers and community members to transcend the narrow and economic interests of employers, be they businessmen or administrators”.

Today, labor law is even weaker than it was back then. And so far, all attempts to significantly reform labor law have failed. Using whatever advantages we have under existing labor law is fine, but pinning our hopes as a movement on changing the law would be the death of the labor movement. Strategies that rely on legal fixes are entirely at the mercy of who the president has appointed to sit on the National Labor Relations Board. A revolutionary union refuses to wait until the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act is passed to take action. We have no illusions about the law, which we know will always side with the bosses and against the workers.

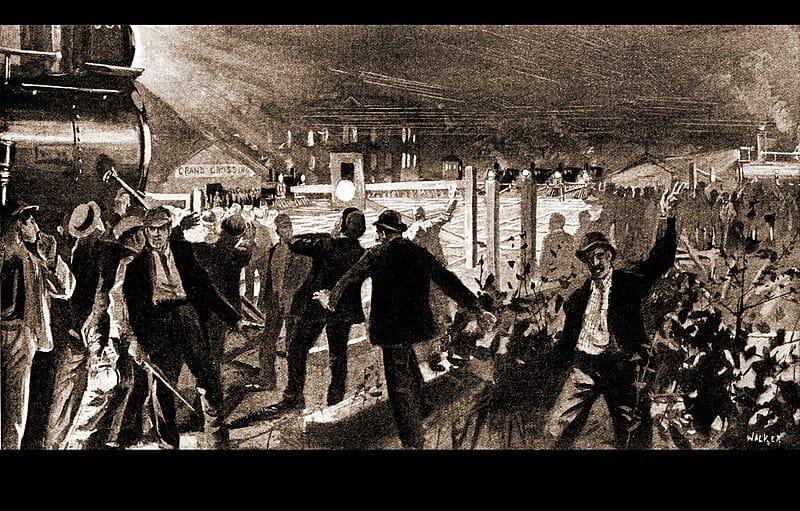

Whenever possible, revolutionary unions should even go beyond demanding changes from economic and political authorities. Instead, we enforce our needs through direct action at the point of production. The early IWW provides a concrete example of what this might look like in practice. In 1917, among the forests of the Pacific Northwest, the IWW’s Lumber Workers Industrial Union (LWIU) led a strike for the eight hour workday. Two months into the strike, the bosses continued to hold out and the US military was moving to repress it—lumber was essential for WWI production—so workers voted to “strike on the job”. James Rowan, an IWW lumberjack and “job strike” participant, describes this tactic at length in his book The IWW in the Lumber Industry:

When the strikers returned to the job, instead of doing a day’s work as formerly, they would “Hoosier up”, that is, work like green farmer boys who had never seen the woods before. Perhaps they would refuse to work more than eight hours, or perhaps stay on the job ten hours, for a few days, killing time. When they had a few days pay, they agreed among themselves to work eight hours and then quit. At four o’clock some one would blow the whistle on the donkey engine, or at some other pre-arranged signal, they would all quit work and go to camp. The usual result of this was that the whole crew would be discharged. In a few days the boss would get a new crew, and they would use the same tactics. Meantime the first crew was repeating the performance in some other camp. When a boss had a crew, he got practically no work out of them, and what little he did get, was done in a way that was the reverse of profitable. A foreman always thought he had the worst crew in the world, until he got the next. The job strikers achieved the height of inefficiency on the job, while retaining their usual efficiency in the cook house at meal times.

In most camps the job strike was varied at times by the intermittent strike, the men walking off the job without warning, and going to work in other camps. This added to the confusion of the bosses, as they never knew what to expect.

These tactics had never been used on such an extensive scale in the United States. The companies could not meet them. All over the Northwest the lumber industry was in a state of disorganization and chaos. There was no hope of breaking this kind of a strike by starvation; much against their will the companies were forced to run the commissary department of the strike.

Because of the previous “off the job” strike, the lumber companies had no reserves left to sell off, either. And the war economy meant that demand was extremely high. The Lumber Trust had no choice but to officially enact the eight hour work day across most of the region. In an era of endless war, the job strike is a tactic that should be in the arsenal of every revolutionary labor union.

Heterodox Strategy and Tactics

In the class war with the employing class, workers must be infinitely adaptable and flexible. Like water, we must be capable of flowing smoothly and evenly in one moment, then cascading in a torrent the next. Revolutionary unions are organized cores of revolutionary workers that provide a vehicle for all willing workers to use in their struggles for a better world. When a group of workers decides to go on the attack—or when they need to defend themselves from capitalist aggression—they can do so with the full weight of the union behind them. A revolutionary union does not back down in the face of intense class struggle. It escalates by widening the conflict, bringing in more and more workers continually, mimicking the continual cancerously expansive logic of capital, but flipping it against capital itself.

The modern IWW calls its organizing philosophy “solidarity unionism,” which is defined in the union’s Organizer Training 101 as direct, democratic, caring, and industrial. As an approach, it de-emphasizes the importance of signing formal collective bargaining agreements (CBAs) and pursuing legal remedies for union busting. Many IWW members advocate eschewing union contracts altogether and relying solely on informal workplace organizing committees. An immense swathe of the economy falls outside the purview of the NLRB, such as “public-sector employees…,agricultural and domestic workers, independent contractors, workers employed by a parent or spouse, employees of air and rail carriers covered by the Railway Labor Act,” and private religious school workers. At these workplaces, “pure” solidarity unionism is, in fact, the best approach, and one that no other union in the US can replicate. With no legal mechanism to enforce CBAs, it makes sense to rely entirely on informal workplace organizing committees supported by a wider union.

We think this is a dogmatic approach when applied too broadly. It adapts poorly to labor organizing in the rest of the economy. Pure solidarity unionism in these industries, after two decades of testing, has mostly produced ephemeral workplace organizing committees, with concrete, long-term impacts equally ephemeral.

Meanwhile, IWW branches that take a hybrid, heterodox approach to CBAs have a far higher rate of lasting campaigns. These branches help campaigns sign CBAs if the workers want to, but treat these contracts as mere scraps of paper that provide a baseline of institutional stability for the workers in the union, and nothing more. In Portland, Oregon, workers at the Burgerville chain organized with the IWW and achieved the first fast food union contract in US history. Despite containing a “no-strike clause,” workers have gone on strike over a dozen times in just the last two years. We should avoid no-strike clauses whenever we can, since they restrict our right to use our most powerful weapon, the strike. Ultimately, however, these agreements are pieces of paper that a revolutionary union should rip to shreds whenever they get in our way. Contract negotiations paired with direct action are a perfect time to assert our principles to transform the de facto, day-to-day enforcement of labor law. Chicago’s Mobile Rail union successfully convinced the NLRB to recognize the IWW’s general opposition to no-strike clauses as a fundamental principle of the union it could emphasize during negotiations.

Moving south, the San Francisco Bay Area General Membership Branch (GMB) of the IWW has the oldest continuous workplace organizing campaigns in the entire modern IWW—all of which have formal CBAs. In addition, the branch keeps racking up new victories with their heterodox approach to contracts. Just within the last year, the branch has organized three Peet’s Coffee and Tea locations, several bookshops, a recycling center, and an environmental non-profit. Most notably, the branch has an ongoing, wall-to-wall union campaign—the Caliber Workers Union—at a regional charter school network with multiple campuses and over 200 employees. They are currently helping the workers fight for their first union contract.

We could overcome the “syndicalist cycle” by incorporating common moderate union practices like contracts in small doses, while never compromising on our revolutionary vision for the future. This approach would inoculate us against abandoning our revolutionary principles. By engaging with these practices we must simultaneously act to transform them. Union contracts normally can only cover wages, benefits, and hours. Organized worker power can change this. Teacher unions in particular, but now also the Writers' Guild of America (WGA), are setting precedent for things like housing, AI, funding levels, and more to be struggled over even in formal negotiations. The cooperation of the Civil Rights Movement and the labor movement in the 20th Century taught us that the law is not set in stone, and that we can change legal precedent through our organized struggles.

Bargaining for the Common Good is an approach that unites the direct action of solidarity unionism with the wider political and economic struggles of our communities. Originally formulated by militants of the CTU during their landmark 2012 strike, the union has continued to escalate the pressure against the legal frameworks designed to contain them. The CTU is now inviting community members into contract bargaining sessions, bringing the wider working class directly into confrontation with the employing class in education. Revolutionary unions should pack contract negotiations with as many members and community members as can fit safely in the bargaining locations. Then, when we have won what we need, we spend the duration of the contract taking direct action to achieve greater shop floor control and improvements to working conditions. When it’s time to bargain the next contract, we fight to codify all of our de facto gains in the new CBA. Capital is endlessly adaptive to our resistance to its rule. We think that these heterodox approaches to contract negotiations and collective bargaining represent a more practically revolutionary stance than turning our backs on them entirely.

At the same time, we must become ungovernable. Burgeoning revolutionary unions intentionally import insurrection into the workplace. That means launching illegal and wildcat strikes. The beloved 2018 Red for Ed education strikes in West Virginia, Oklahoma, and Arizona (and beyond) were all illegal and nearly entirely against the will of their union bureaucracies within the AFT and NEA. It also involves unifying our industrial battles with the insurrections in the streets. After the failure of the Detroit Rebellion of 1968, Black auto workers decided to take the lessons of the uprising and bring them to the point of production in their own workplaces. This was the genesis of the LRBW. History provides no shortage of other inspirational examples.

In the deepest depths of the Great Depression in 1934, Chicago teachers rioted, looting banks and beating mounted police with textbooks. That same year, the Minneapolis Teamsters Strike saw “a major battle between strikers and police…in the central market area.” Knowing that the police would try to break their strike, the union placed 600 strikers in the nearby AFL headquarters. When the police arrived, these picketers “emerged and routed the police and deputies in hand-to-hand combat. Over thirty cops went to the hospital. No pickets were arrested.”

Teachers in Oaxaca, Mexico, took it several steps further in 2006 when police attempted to evict their annual strike camp—which occupied the city’s central plaza. After the teachers repelled the cops’ first assault, the city’s entire disproportionately indigenous working class mobilized and expelled them from Oaxaca entirely. For nearly a year, Oaxaca was governed by community and worker assemblies until federal Mexican troops retook the city. Even then, the movement survived and has continued to evolve. Ten years later, in Catalonia, revolutionary unions, including the modern CNT, called a general strike in response to police repression of Catalan separatist protests and electoral shenanigans by the central Spanish government. Reformist unions, surprisingly, followed their lead. Police forces were forced to retreat across much of the region. Revolutionary unions effectively tread a fine line by advocating against Catalonian nationalism while articulating working class rage against those who would try to crush the self-determination of their people. The “ability for the CNT and the other radical unions to take leadership of the situation was based on their very patient day-to-day organizing in workplaces and communities—as revolutionaries”.

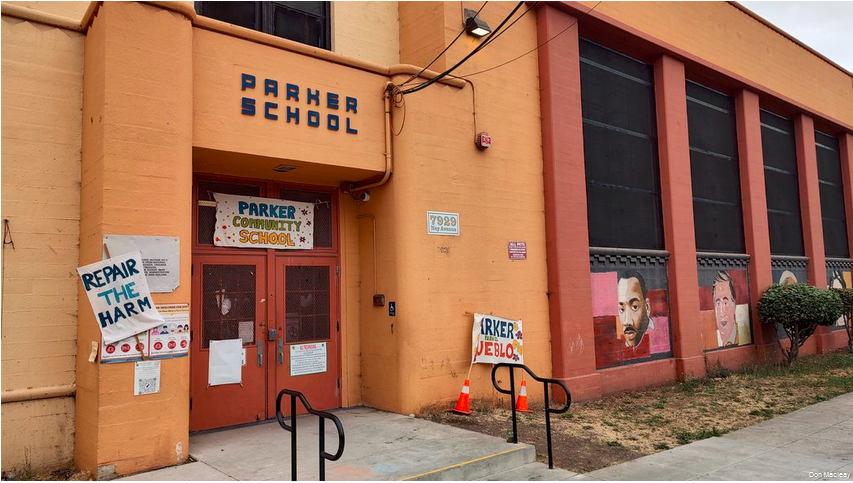

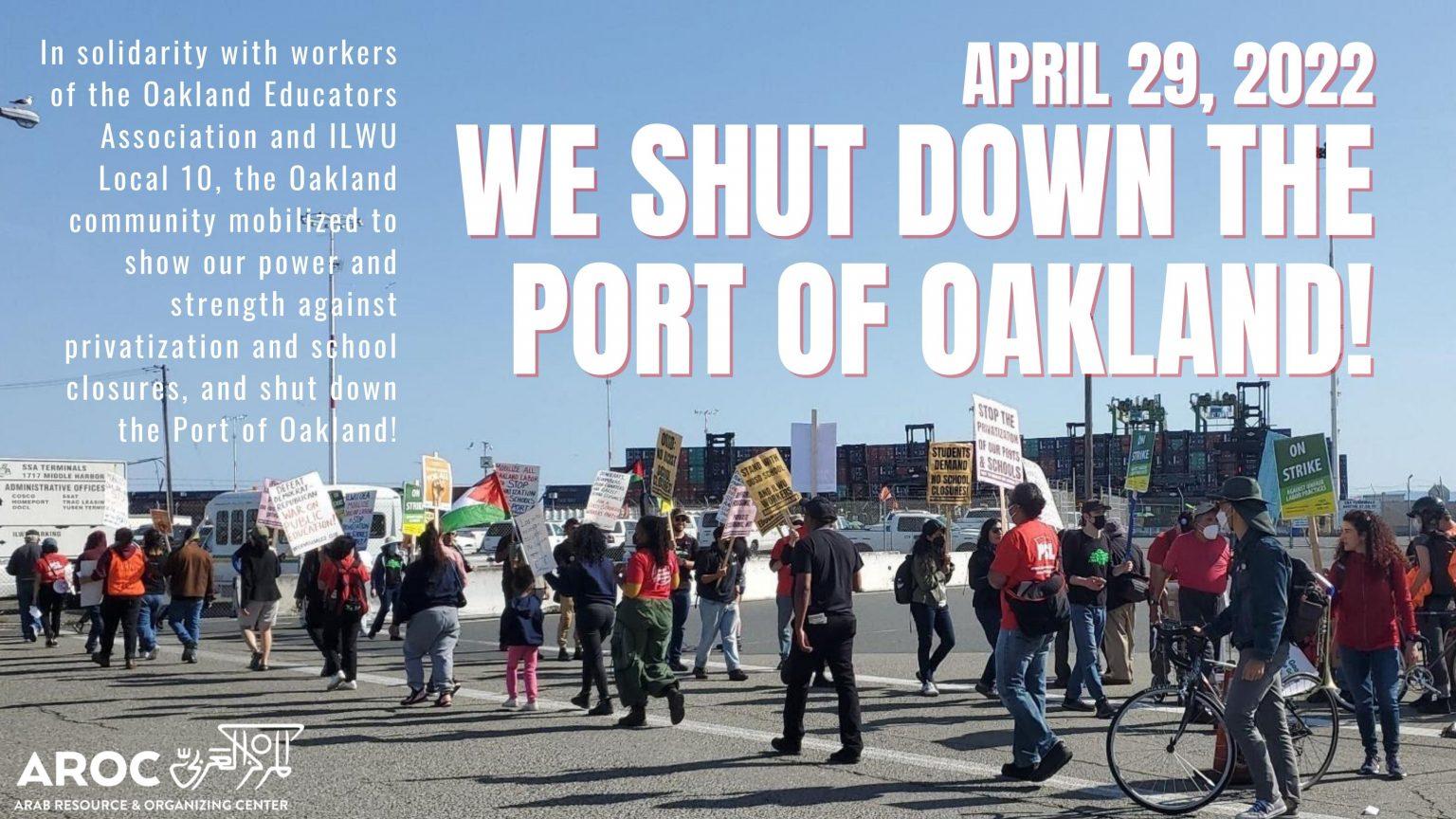

Closer to home, an informal coalition of school workers from the Oakland Education Association (OES) and the Oakland International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) joined forces to oppose gentrification and school privatization in their city. Their alliance culminated in the occuptaion of Parker Elementary School, which had just been closed in order to make way for the city to open even more charter schools. Reopened as a community school for the summer of 2022, the building became a hub for neighborhood organizing and truly democratic education. Until the city hired private security to forcefully evict teachers, dockworkers, and their children, that is.

The syndicalist union SI Cobas in Italy uses mobs of students and left-wing activists from outside the workplace to set up blockades of workplaces during strikes of small groups of migrant workers in logistics. This tactic enables precariously employed migrant workers leverage against their powerful employers until they’ve built majority support in the workplace. Combining such insurrectionary tactics with anti-imperialist organizing would represent a major strategic innovation and bring the abolition of the Military-Industrial Complex into view. Palestine Action is an anti-imperialist, anti-war group that targets multinational weapons manufacturers—specifically those used by the Israeli regime against the Palestinians, like Elbit Systems—for blockades, occupations, and sabotage. With the cooperation of revolutionary unions and organizations like Palestine Action comes the potential of the occupation of weapons factories and their transformation into sites for the production of socially useful goods. Even starting with just one or two conscientious workers could be enough of a foothold to spread the struggle through a whole plant. In Florence, Italy the ex-GKN Factory Collective helped conjure a vision of what this might look like when it occupied its workplace after the employer closed the facility. Since then, they have been fighting to transform the plant into a public hub for sustainable transportation.

Even though most of these struggles ultimately ended in failure, they represent the seeds of a future revolutionary union movement that can overcome the employers and the state. They prove that imposing insurrectionary tactics such as occupations, sabotage, and blockades onto our bosses work in our favor. Let them cry about it, as long as they concede to all of our demands. If they don’t, we’ll take that power from them and run them out of town.

By demolishing the legal framework of narrow trade unionism, we bring the fight to a broader confrontation with the economic and political powers who rule over us. Workers are already moving in this more militant, potentially revolutionary direction. Just looking at the education industry: illegal strikes, street protests, occupations of school workplaces, wall-to-wall unionism, bargaining for the common good, organizing the unorganized, borderline solidarity strikes, and political strikes all point some ways forward. Meanwhile, workers are clearly increasingly unsatisfied with the conservative bent of most mainstream unions. All revolutionary unions should encourage members employed in already unionized workplaces to build worker power independent of the leadership.

Internationalist

Nationalism is a poison that has no place among the working class, especially not its revolutionary sections. Today’s nation-states are arbitrary institutions constructed by the bourgeoisie as ideal forms for accumulating capital through imperialist exploitation of the majority of the world. Capitalism has always been a globalizing system. From its earliest days it has spread from Western Europe to the entire world through colonization. Its supply chains stretch many thousands of miles—crossing political borders and sweeping up billions of workers into vast corridors of production, distribution, and consumption. It relies on uneven development between imperial cores and peripheries. A revolutionary union movement organizes down these supply chains, refusing to fall for the trap of nationalism.

Social democracy, as popularized by politicians like Bernie Sanders and organizations such as Democratic Socialists of America, fails to address imperialism. This should come as no surprise, since social democracy at home relies on complicity with imperialist policies abroad. Capitalists and politicians contain working class resistance in the Global North through public welfare programs, class collaborationist business unions, and consumerism. All of these come at the expense of workers in the Global South. A social democratic United States would have to reproduce this imperialist dynamic to deliver on its promises. We are not just speculating here, look at the supposedly model social democratic societies: the Nordic countries. They fully participate in the looting of the Global South, just like all other capitalist nation-states. And that goes back centuries. The most social democratic nations can ever accomplish is a fairer distribution of society’s wealth within their own borders. New Deal America couldn’t even deliver these benefits to Black citizens or other marginalized groups. Prominent social democrats appear unable—or unwilling—to address this critique. Instead, they denounce anyone who dares point out their hypocrisy as “tankies”, a now meaningless term.

A revolutionary union movement must break with social democracy. That means rupture with the nation-state itself. We have far more in common with workers across the world from us, and nothing in common with the bosses in our own country. Patriotism and nationalism are essentially one and the same, despite all the liberal attempts to separate the two. Revolutionary unionists belong to a “nation of workers,” as the early IWW members referred to themselves as. How can we be patriotic for a nation whose very existence is based on robbing land from indigenous peoples through genocide so demented that it inspired the Nazis? The United States is indefensible. Our movement, then, recognizes no borders except the one between workers and bosses.

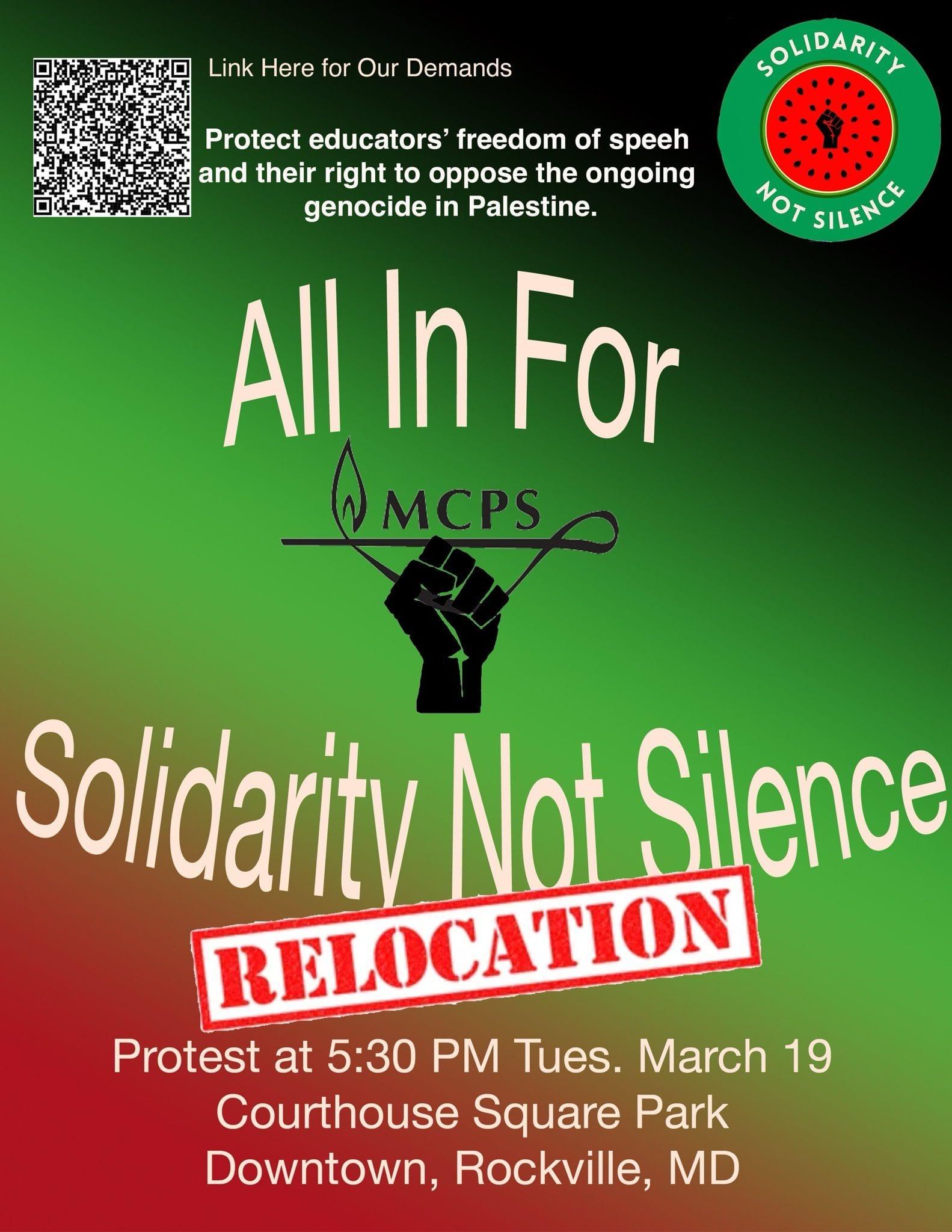

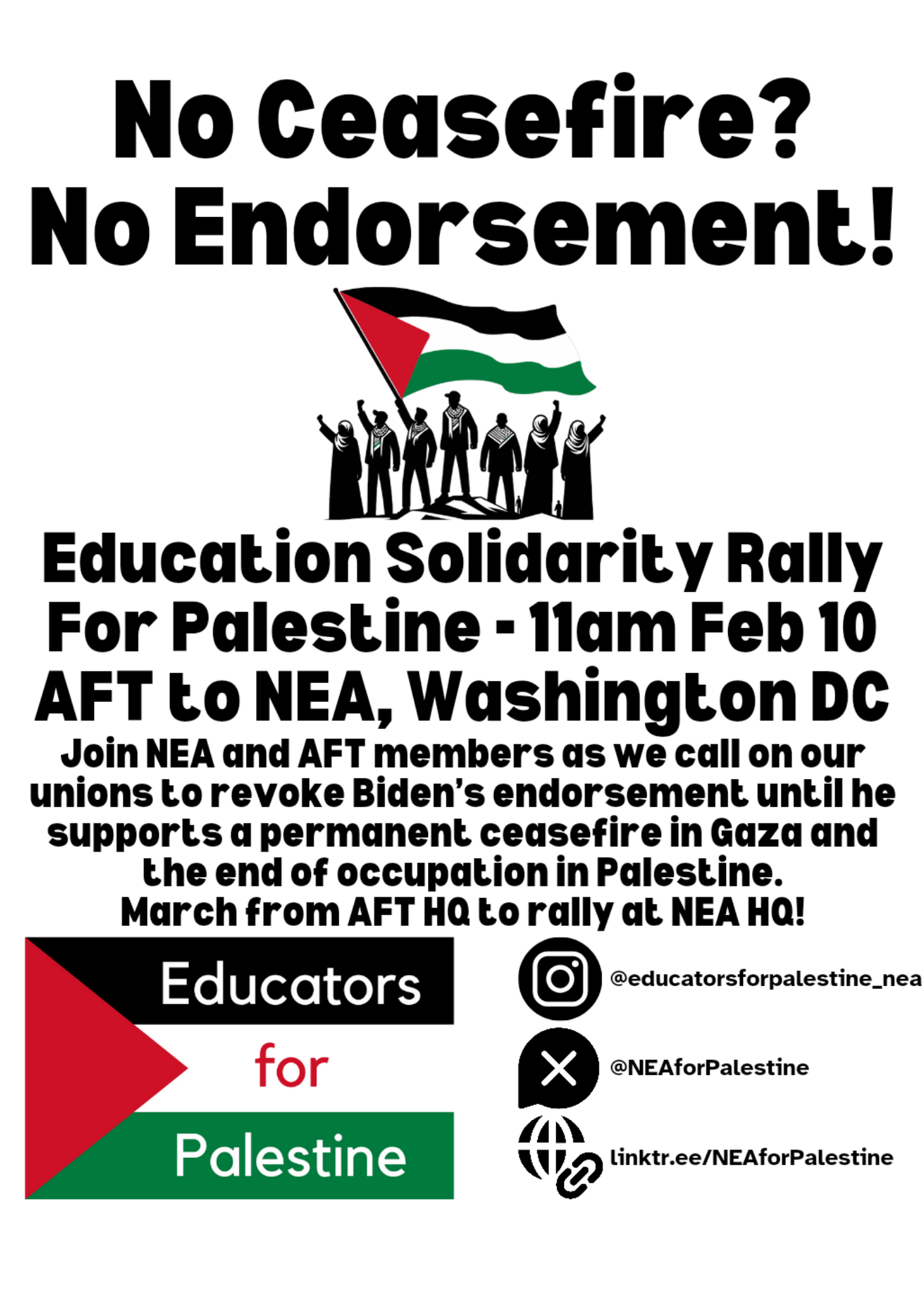

Rather than seeing ourselves as the citizens of separate nations, workers should understand themselves to belong to an international working class community. It’s way past time to coordinate with—and learn from—our fellow workers in the Global South. Bangladeshi students, the Neighborhood Resistance Committees in Sudan, Bolivian mine workers and peasants, and of course Palestinian workers all point the way forward for our movement. We have to actively cultivate deep relationships of solidarity with workers involved in these movements and others. For nearly a year now, militants within the labor movement have been struggling against Israeli apartheid and genocide in Palestine. While not receiving much publicity for it, IWW locals have been on the ground consistently, organizing with Palestine Solidarity movements in the United States, Canada, and Europe. For example, IWW DMV EWOC helped coordinate the Solidarity, not Silence! campaign, alongside rank-and-file teacher unionists, students, and other local activist groups such as Jewish Voice for Peace and Maryland2Palestine.

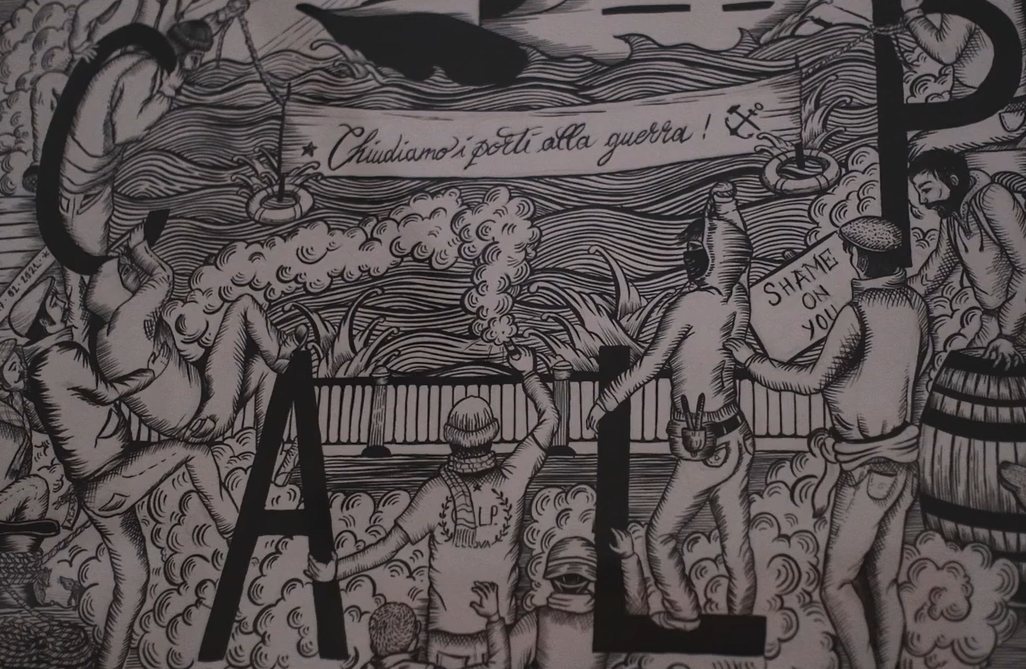

Similarly, there are quite a few revolutionary unions outside the United States that we need to learn from and coordinate with. All of us are building with few resources, no institutional support, and amidst escalating repression. We should work to strengthen international coordination between our unions through bodies such as the International Confederation of Labor (ICL) and the International Workers Association (IWA). When beneficial to us, we should also cooperate with the mainstream, moderate union movements around the world. Our goal is to spread the revolutionary union struggle along international supply chains, by whatever means necessary. In Italy, the migrant militants of Si Cobas and Genoa’s Autonomous Dockworkers' Collective (CALP) give us a glimpse of what this might look like in practice. CALP is organizing transnational strikes of dockworkers against militarism, and has already been instrumental in getting all weapons shipments to active warzones banned in the city of Genoa. Si Cobas, positioned at a critical juncture in international supply chains, could expand these struggles into the logistics sector.

All of this obligates us to reject all war except the class war. Every government, every boss is our enemy, especially “our” government and “our” bosses. Whenever they trick us into supporting yet another imperialist war (because somehow it’s different this time) against our proletarian siblings, we are fighting ourselves. Our revolutionary union movement has to take a strong, principled stance against every—and yes, we mean every—war the politicians try to sell to us, followed by concrete strategy and tactics on how to obstruct the war effort at the point of production. That includes direct action to aid indigenous peoples in achieving decolonization of Turtle Island, so-called North America.

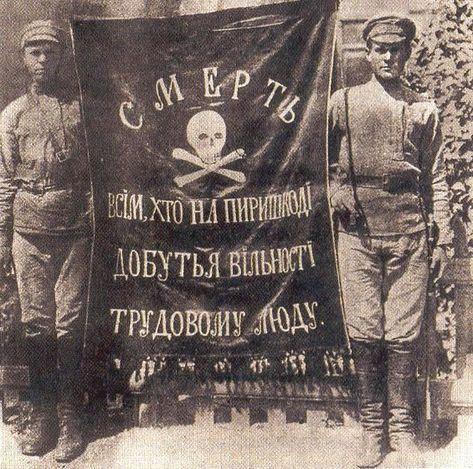

Antifascist

The rapid rise fascism over the last twenty years poses one of the most serious dangers the working class must confront as we reorganize to overthrow capitalism. For those of us working in education dealing with the menace of school shootings and facing mob attacks just for teaching the truth, that should be relatively obvious. There has already been one coup attempt: January 6, 2021. ‘Civil war’ seems to be back on many people’s lips these days, now that another election year has forced us out of our usual historical amnesia. Most whisper it with dread, while others recklessly seek to invoke such a catastrophic event, one that will open a Pandora’s Box of violence no one can slam shut. Our situation is dire. It is nothing short of an emergency. There has been—and will continue to be—an increase in violent physical attacks on sections of the working class.

We have a right to self-defense. Our lives, and the lives of our loved ones, are on the line. The ruling class response to the Occupy Movement, the Ferguson Uprising, George Floyd Uprising, the Palestine Solidarity Movement, and a multitude of others around the world should leave us with no illusions. Police brutality was a major instigator of the Catalonia General Strike of 2017, with the outpouring of the workers and their supporters onto the streets effectively halting all police operations across the entire region. Cops aren't workers, they are the enemies of the workers, they are the lapdogs of the employing class and should be treated as such. A more local example comes from the Vermont AFL-CIO, which socialist workers in the UNITED! Slate democratically transformed into a state-wide workers’ council during the late 2010s. In 2020 the Vermont AFL-CIO approved a resolution authorizing a general strike across the state in the case of Trump stealing the election, as well as calling on other AFL-CIO affiliates to do the same.

The CNT-FAI served as a hub for several million Spanish workers and peasants to turn a fascist coup into a social revolution across much of the nation—especially in Catalonia, Andalusia, and Aragon. Countless workplaces and estates were taken over and run by the people themselves, leading to significant increases in production even amidst the Spanish Civil War. Militias used the revolutionary union movement to organize themselves and defend the new world they were building behind the lines.

Unfortunately, the Spanish Republic was internationally isolated—with only the USSR providing aid and weapons—while the fascists received substantial military and economic aid from Nazi Germany and Mussolini’s Italy. At the same time, the Spanish Republic and USSR were not exactly friendly to the aims of the mostly anarchist-influenced revolutionaries. Using its aid as leverage, the USSR could manipulate the Spanish Republic, largely taking over its security services and opening up a civil war within the civil war between the Spanish Communist Party and the anarchists. These so-called communists busted up rural communes and urban collective factories, collapsing the economy of the remaining Spanish Republic so badly that many had to be reconstituted just to keep production going. Spain’s Republican government also demonstrated hostility to the CNT-FAI and its supporters. They refused to provide the revolutionaries with any of the weapons they urgently needed, and exploited Soviet communist offensives against the CNT-FAI to co-opt its militias. This history emphasizes the need for a revolutionary union movement to be radically independent.

Returning to recent events, the UK’s National Union of Rail, Maritime, and Transport Workers (RMT), while not a revolutionary union, took an antifascist stand against fascist pogroms that we should learn from. As fascist dupes attacked immigrants and anyone they labeled as Muslim, the RMT leadership sent a message to all its locals: “We are therefore asking Branches where possible to be in contact with their local mosques, refugee centres and solidarity groups to offer our union’s solidarity and support on the ground at a time when they face severe threats and intimidation.” The RMT is already one of the UK’s most militant, progressive, and democratic trade unions. We should take this approach a step further, thoroughly rooting ourselves within our communities. That means building a visible and powerful presence on the shop floors of the workplaces wherever we are.

Within the IWW, there have been several effective interventions in the struggle against fascism domestically. One of the only other unions in the UK to respond with strength to the pogroms was the UK IWW. Every local branch across the nation called its members into the streets against the fascist threat. There is also the General Defence Committee (GDC). A long existing but dormant committee, antifascist IWW labor organizers such as those from the Pan-African Caucus of the Twin Cities Branch took it up as a tool to wage worker centered struggle against the fascist forces unleashed in the wake of Trump’s 2016 election victory. Through its efforts, the IWW gained a new relevancy with working people it hadn’t possessed in many decades. Another example from the IWW was the 2020 University of Santa Cruz Wildcat Strike. While the UC system is organized with the UAW, IWW militants were highly influential at UCSC and UC Davis. When their employer loosed police on the strikers, it provoked a backlash that popularized the “cops off campus” demand—unifying workplace and antifascist struggles.

Anti-fascism is core to a revolutionary union’s philosophy. An injury to one is an injury to all! While our unions are anti-sectarian and welcome workers of most political affiliations, we demand all members affirm and accept the identity of all of their fellow workers. The working class encompasses people of all faiths, ages, ethnicities, genders, body types, and a million more variations. Nazis, or any type of fascists, are not welcome. Abusers are not welcome.

Revolutionary unions concretely support radical community organizing projects such as Stop Cop City—a movement whose strategic and tactical innovations are a model for all of us. Policing is a fundamentally fascist institution, a type of power that always demands more. And since policing was invented to defeat proletarian resistance—both enslaved and free—we have no choice but to combat and defeat them by any means necessary. Members of revolutionary unions must be on the ground at movement rallies, blockades, and occupations. Organizationally, our unions can simultaneously organize secondary strikes and boycotts against any company involved in the construction of any cop city. Stop Cop City is just one example, the exact same logic can be applied to indigenous-led Land Back movements, anti-war struggles, and every other radical social struggle. At every turn, we can find opportunities to connect these struggles to those in our workplaces.

The IWW already has an effort underway to accomplish this connection through its Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee (IWOC). It is currently the union’s most revolutionary project of its modern history. Organized by and for prisoners, IWOC has launched multiple prison strikes, including the largest prison strike in US history in 2016. Working in coalition with groups like the Free Alabama Movement (FAM), over 24,000 incarcerated workers across 24 states went on strike to end prison slavery.

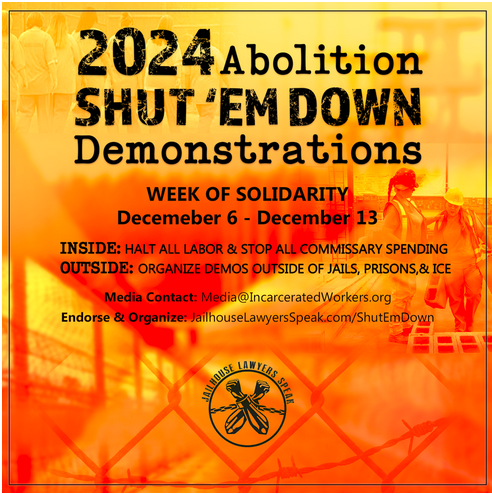

IWOC is unambiguous about connecting the struggles of the imprisoned with those of the entire working class. This year, IWOC has thrown its weight behind supporting the organization of Jailhouse Lawyers Speak’s 2024 SHUT ‘EM DOWN Demonstrations. We encourage all readers to find a way to participate in relevant local actions during the Week of Solidarity from December 6–13. A revolutionary union movement must organize in the prisons. Prisoners are our fellow workers, caught up in capitalism’s most brutal, inhumane workplaces. There is no excuse for writing off their fight for liberation as unrelated or tangential to workplace union organizing. Slavery built the modern capitalist system, and prisons represent the continuation of that enslavement to the present day. They are fascist institutions rooted in genocidal colonialism.

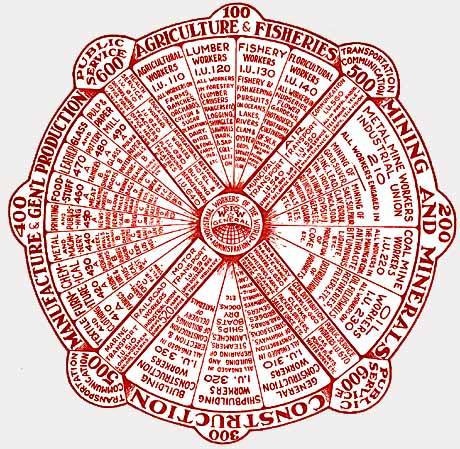

Industrial(?)

This section of “Towards a Revolutionary Union Movement” has been met with skepticism and criticism by some who argue that industrial union strategy is not necessary to be a revolutionary union. One fellow worker argued that requiring revolutionary unions to adopt an industrial organizing model could cut off possibilities for alternative forms of solidarity and organization between workers. For example, a union organizing model that incorporated all public service workers—such as teachers, bus drivers, postal workers, hospital workers, and sanitation workers—might be overlooked when organizing strictly by industry. Advocates of industrial unionism could point to the IWW’s groupings of closely related industries into departments, including Department 600 for public service workers, as a solution. Some fellow workers compared industrial organizing to sectoral bargaining—which is not necessarily revolutionary. Other fellow workers disagree with the comparison entirely. It is also possible that the necessity for a revolutionary union to organize industrially is confined geographically to North America, or even just the US.

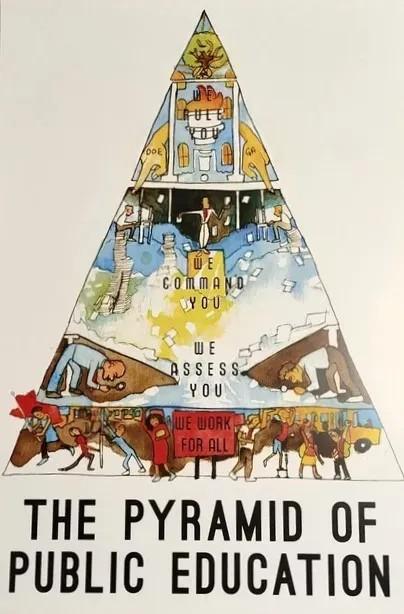

Business unions have all demonstrated their insufficiency in achieving or maintaining even modest social democratic goals such as universal healthcare. That’s because they lack any coherent strategy outside of winning contracts and electing Democrats (unless you’re even more of a clown, like Sean O’Brien). Besides their class collaborationist nature, this lack of strategy can be explained by their organizing strategies. The main choices for business unions consist of: craft unionism, general unionism, and a hybrid of the previous two. Revolutionary unions organize industrially.

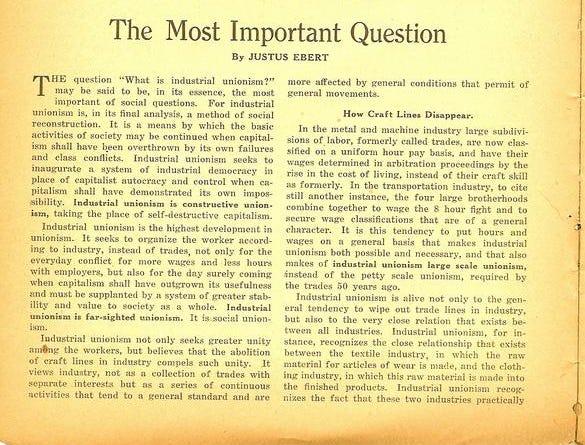

For a full, yet concise, explanation of what industrial unionism is, please see Justus Ebert’s 1919 pamphlet “The Most Important Question”. Over 100 years later, it still holds up, and is currently being adapted for modern use by the IWW. The article “Industrial Unions and the IWW Explained” by Liss Waters Hyde and Jaime Caro is an excellent explanation geared towards the modern IWW. A short definition is that industrial unionism is an organizing model that unites workers by the type of industry they work in, rather than their specific job role. Generally, industries are distinguished by the products or services they generate, or how those goods are distributed throughout society. According to this thinking, all workers in the same workplace should be in the same union local, regardless of occupation, education level, or any other ultimately arbitrary division. Further, all workers in similar workplaces across the same geographic area should be included, too.

Industrial unionism carries the potential to go on a class offensive against capital itself. A core principle of this organizing philosophy is that all industries are fundamentally tied together in the whole of social production and reproduction. The logical conclusion is that our solidarity with all other workers is the key to our victory, while disunity is the mechanism of our defeat. Look at our shared working class history of the last few hundred years. It is a history filled with betrayal, prejudice, and abuse: men betraying women during the Witch Hunts, white supremacy and Western imperialism, violence directed against one another and our communities. Ebert describes industrial unionism as “a method of social reconstruction. It is a means by which the basic activities of society may be continued when capitalism shall have been overthrown by its own failures and class conflicts.”

Industry-wide strategy is a necessity for proletarian victory on the terrain of production. Existing labor law attempts to confine working class resistance to specific workplaces as much as possible. Capital, meanwhile, has no restraints; especially under Neoliberalism. Not even international borders can stop the flow of trillions of dollars of capital, all of which is simply stolen labor.

Industrial unionism contributes to the prefiguration of a future democratized economy. It doesn’t matter if we’ve organized the whole economy when a situation of dual power emerges, what matters is that we already know how to horizontally organize our workplaces. We can then work to extend these new societal relations to everyone through persuasion and education. Those of us who work in education will have a special role to play in this process. Only through organizing industrially can the workers create a truly independent pole of power during a revolutionary transition, and by doing so prefigure a wider transformation in social relations that resolves the tension between worker’s control and wider societal needs.

Accomplishing this requires honing in on strategic industries first. That does not mean abandoning small or marginal workplaces, of course. Most of the business unions turn down requests for external organizing support from small workplaces because it’s not “worth it” for them from an economic perspective. We don’t want to emulate that. On top of that, at every stage of capitalism, including this one, smaller firms make up the majority of economic activity. That said, large workplaces and employers represent important objectives for a revolutionary workers’ movement to conquer. Taking the example of education, school districts in the US are usually some of the biggest employers in a city, county, or even state. Hospital facilities, too. And that’s not to speak of the massive warehouses and logistics networks spanning the world. Revolutionary unions must target their organizing by industry, embedding salts and gathering recruits in as many of the different types of workplaces in the industry as possible. If possible, this organization should be spread internationally.

Rooted in Communities and Social Movements

Throughout the 20th Century, the employing class and the state were able to exploit divides between labor unions and other social movements to defeat both. Revolutionary unionism seeks to repair these deep wounds and to root itself among our communities and social movements outside the workplace. Joe Burns provides an excellent way of understanding the importance of rooting ourselves like this: “Whereas class struggle unionists see themselves as fighting for all members of the working class, business unionists narrowly represent their members even when they are at odds with the broader working-class interests.”

Bargaining for the Common Good represented a fundamental step forward for our movement when first developed by teacher unionists in the CTU) Teachers’ unions have long linked their workplace struggles with the wider working class struggles for housing, racial justice, women’s rights, LGBTQ+ liberation, and more. Just because these movements are often not explicitly radical or revolutionary does not mean our unions should distance ourselves from them. Quite the opposite. It is our responsibility as revolutionary workers to agitate, educate, and organize the entire working class. That means providing an example that can demonstrate the necessity of revolution, as well as the integrity of our organizations. Otherwise, community social justice movements and revolutionary labor unions will advance separately into our respective pitfalls. We need an ecosystem of organization.