Anonymous

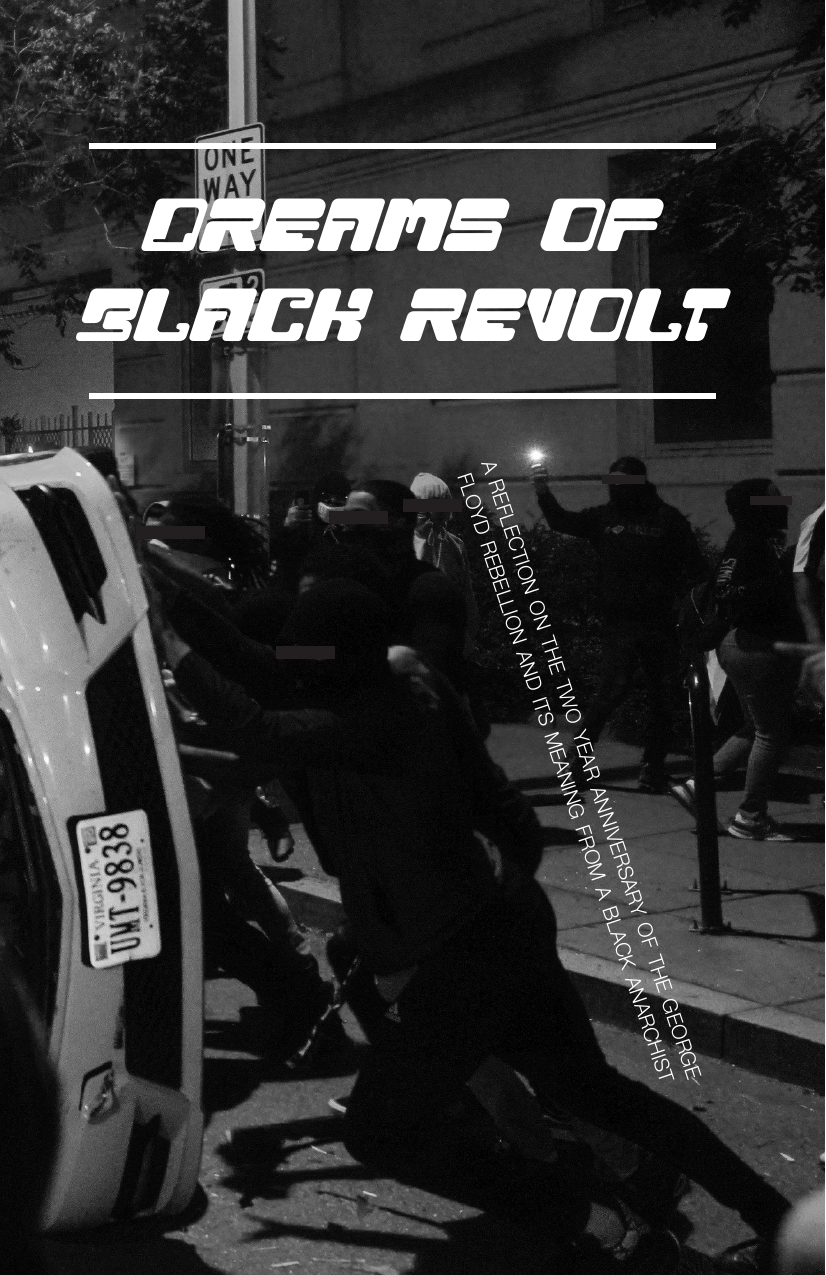

Dreams of Black Revolt

A reflection on the 2 year anniversary of the George Floyd Rebellion and its meaning from a Black Anarchist

Note: A lot of people seem to be writing about the rebellion. However, there aren’t enough black anarchist voices (or black revolutionaries in general) publicly reflecting on it. Our input matters the most right now in my opinion. Shoutout to the Anarkatas, Lorenzo, Saint from Haters, the comrades who wrote BAJ, and all my homies who I talk to about this stuff. I hope this gives yall a taste about what’s been on my mind the past two years. I’ve been involved in a variety of writing projects but this one is really just a mostly personal reflection on how I’ve been feeling. One day I’ll be back on twitter but I hope this one essay helps shape the discourse a bit more, haha. It isn’t meant to be a full critique of anything. It’s just a few ideas that been bouncing around in my head.

It has been a little over two years since my brother and I watched the livestream where the Black rebellion burned the 3rd precinct in Minneapolis. We had discussed going to Minneapolis in the days prior because we understood how important it was. Luckily, the rebellion came to our city next despite our incredulity. The gravity of the moment was clear to us, but fundamentally we was were still so unprepared for the moment. This lack of preparation brings me deep shame and regret. It’s been two years and I still feel that the moment for many of us was missed.

In all honesty, I didn’t believe widespread rebellion, let alone revolution in the United States was possible prior to 2020. I had resigned myself to the fact that the peripheries of the American Empire were the only places where revolution was possible, believing our only goal as revolutionaries here was to build to support oppressed people in the Third World. The Black revolution had been defeated in the 1970s. Our warriors were killed or locked away from our communities. The black neo-colonial class was ascendant. The white proletarian counter-revolutionary impulses were too strong to overcome. There was no future for the Black movement in the United States. And then, the rebellion of 2020 happened. This was a revelation for me. It shifted everything in terms of my belief in social transformation. Revolutionary moments should be revelations for us all. I fundamentally believe now that we have a chance to see revolution in our lifetime.

Over the past two years, I have realized that my commitment to struggle could not be contained to activism as a hobby. I have always tried to not be contained within anarchist or activist subcultures, socially. I feel these anarchist subcultural scenes are often toxic and strange (also white), so I do not spend time in them. Thus, many of my friends and lovers do not share my beliefs. Long time relationships were filled with tension leading to their end as a result of the rebellion and its fallout. Many people in my life did not grasp the importance of the uprising, and, to me, those are the moments that test who we are as human beings. We must allow these moments to change us and adjust who we are and how we exist in the world. We must not resist it and act as if the revolt was a blip in history. For many of us who have lived shorter lives, it was the closest thing to freedom, liberation, a revolution or anything along those lines that we have experienced. Even if you did not participate directly, those of us who seek liberation must grapple with the importance of the rebellion in our own lives and the broader world.

I have been a self described pro-Black activist since I was young before eventually calling myself an anarchist. I have always understood myself as linked to the Black liberation struggle. I read Malcolm, listened to Dead Prez, and watched the Baltimore Riots live in high school. I was inspired by the Black teenagers fighting back on their own terms against the police. I remember post-Trump, I saw some people in black bloc fuck up a car that tried to ram a Black Lives Matter march, and I decided those were the type of politics I wanted to have. However, I found myself brought into a bunch of socialist and communist milieus that doubted the viability of Black self-activity as the central force for revolution. I found myself lost in a dual-power infrastructure/base-building milieu who resigned me to the fact that we were not ready to fight back and we just all needed to build community gardens and worker’s cooperatives. I was really into learning about Cooperation Jackson, Black cooperative farming practices and Black histories of mutual aid. I think some mutual aid and cooperative economic projects are cool but most didn’t seem to be relevant to the rebellion at all when it happened. They seemed to be mostly passion projects of middle class people masquerading as “revolutionary”. While I think those things are well intentioned, they were largely disconnected from the fighting on the streets. I just think we gotta keep it real. Other articles like those written by the homies who wrote Black Armed Joy have explained the limitations of “mutual aid” a bit better than myself. Conversations with my Anarkata comrades have also shaped my opinions about care and militancy in meaningful important ways. I’m not against mutual aid, I just think we gotta explore the care and revolt dialectic a bit more but I can’t do it justice here.

I got caught up in the idea that I needed to follow or defer to a certain type of Black leadership if their ideas were not correct. I no longer believe that revolutionaries should reduce their own politics for the sake of deferring to people on the basis of identity when these politics are not revolutionary, despite how uncomfortable it may make us feel. I do feel that I had a sort of vanguardist attitude towards the Black masses with my emphasis on the need for revolutionary “infrastructure.” To be clear, I was never a self-identified authoritarian; I always considered my politics anarchist. Despite this, when the rebellion came, I initially lagged behind the masses in terms of ferocity, strategy, and power. I do not want that to happen again.

Prior to the rebellion, I spent my time connecting with other Black anarchists and trying to develop an analysis around the Progressive Plantation and the lack of a Black liberation tendency within the anarchist movement. I felt myself drawn to abolitionism in the tradition of the Revolutionary Abolitionist Movement which learned from Nat Turner and the BLA or the Militant care of the Anarkatas who learned from Marsha P. Johnson and Kuwasi Balagoon. I read DuBois, Cedric Robinson and the Combahee River Collective. I watched documentaries about the Black Panther Party. All of these ideas shape this essay and I’m grateful for all of those revolutionary contributions as they shape my outlook in this moment.

I never understood my abolition rooted in reform. However, we did not live in a revolutionary era as I understood it. So, prior to the rebellion, I felt that there were many ways forwards for abolition whether it was “non-reformist” reforms or through the insurrectional attacks. If you had asked me prior to the rebellion if I supported “Defund,” I would have said yes. I did not see the actions in the rebellion as opposed to “non-reformist reforms,” but the rebellion revealed to me that they were. In reality, those reforms were not achieved. Defund became nothing. It was easily co-opted. #DefundThePolice was used to distract from the power of the insurrection.

The activists and organizers and academics (abolitionist industrial complex as I call them) co-opted the George Floyd rebellion. Every day, there is a new abolitionist book published which repeats the same tired lines about how cops don’t keep us safe and all that. Despite claiming to be revolutionaries, these academics do not defend the actions of the black rebels; instead they focus upon the actions of activists. Robin Kelley’s new intro to Black Marxism is a good reference for what I mean. He focuses upon the #DefundThePolice activists as the continuation of the Black Radical Tradition in his intro instead of the black rebels who fought police and engaged in looting. It is tiring. The Black proletariat stands alone. The audiences for these abolitionist books are the mostly non-Black petit bourgeois activist class who consumes them with vigor. Most of these books want us to “imagine a world beyond prisons or police” and to push for socialist democracy or whatever in the United States. While I’m not against imagining a new world, real solidarity means supporting the masses in their revolutionary action against the State. For years, the Left has mostly sat on the sidelines when the Black masses have decided to fight. In some cases, the Black Left has co-opted the Black struggle to build their activist clout, get book deals, and nonprofit money while the Black masses are killed and incarcerated for fighting in the rebellion. The reality is that as a revolutionary, I have more to learn from the Black youth who fought the police in my city or from prisoner who fought the COs in prison than I do from Black or non-Black leftists with PhDs. The reality is the real struggle against the police and racial capitalism emerges from the margins. The people with the least to lose are the ones most willing to fight. Unfortunately, most of the Black “abolitionists” and leftists do not care at all to build or interact with these young rebels. Despite this, The Dragon will be awakened, and that’s word to George Jackson. We all saw the precinct burn. Most Black academics and nonprofit types are incapable of comprehending what it meant. Most Black academics wrote it off or ignored it. The Black writers who guided my understanding in the moments right after the rebellion and engaged directly with the politics of the revolt were Marcus Sundjata Brown, Idris Robinson, the We Still Outside Collective, and Yannick Giovanni Marshall. I thank them for keeping my head on straight with their analysis.

It is the duty of Black anarchists and Black revolutionaries to build our own networks that train and prepare ourselves mentally for uprisings as it clear that the Black left (both the activist and academic forms) is uninterested in creating networks that could actually fight alongside the Black masses. I want to be clear that I do not believe Black anarchists should be doing a sort of Leftist soldier cosplay like we’ve seen with some of the black bloc anarchists, especially in Portland and elsewhere. I think that the specialization that some anarchists have engaged in is alienating, and it often doesn’t contribute anything tactically. Plus, I saw people in black bloc protect police stations, wave American flags, and act in roles for “descalation.” Black youth with t-shirts over their faces seemed more capable and willing to fighting than many of the seemingly geared-up or well-prepared militants (who were mostly white) in my view. It is a tricky position that Black anarchists find themselves in, as we should be training to be ready for an uprising, but we also shouldn’t engage in some strange anarchist military shit that parts of Left seem into.

Even so, most of the Black left is just as opposed to the revolt of the Black masses as the Black liberals are. Most Black abolitionist or Black socialist groups just want to march around making “demands” about community control of the police, which has little appeal to the masses of Black people and therefore is not much better than the faux black bloc militants. I know Pan-Africanists who will call the police while quoting Kwame Ture in their facebook posts. The Black left has little to no presence in the Black community and instead they spend most of their time in academia or around their white or nonblack leftist “allies.” Worse than that, Black leftist groups like Black Alliance for Peace, Hood Communist and AAPRP promoted/gave platforms to cult leaders like Gazi and Black Hammer who abused and hurt black youth. (Go Read Redvoice’s articles The Devil Wears Dashikis on this if you want to know more about the type of cults that the Black left has unfortunately spent so much time supporting and boosting) For this reason, I am uninterested generally in black leftist politics as they exist in the United States.

However, the true Black radical politics I am invested in is the politics of the Black revolt that were on full display during the George Floyd Rebellion. The never-ceasing, constant ability of our people to fight back against our oppressors under any circumstance. As CLR James says, “The only place where Negroes did not revolt is in the pages of capitalist historians.”

Many Black liberals propagated the idea that our people are timid and helpless. The idea that Black people could not simply act on our own in violent and meaningly ways against our oppressors is the most evil and racist lie that has emerged in the past two years. It is unfortunate yet unsurprising that Black leaders now choose to relegate our people to the dustbins of histories instead blaming the revolt on cops or whites who lead our people into “danger.” The United States has always been dangerous for Black people but suddenly these Black liberals become concerned about safety when the Black masses fight the State. Through these lies of Black victimhood, we have been reduced back to electoral politics, the never-ending marches, and continual terror of this anti-Black world with no possibility of a future. I have no hope in the Black left, Black activists, or Black leaders anymore, but I do have hope in the exploited, oppressed and marginalized Black masses.

I come from a Black nationalist understanding of self help, so I do not think we can really rely on white radicals either for us to be trained and well equipped to fight. I think it’s sort of boring to critique the white left, though I understand the necessity of those criticisms. I just don’t really feel like that’s where my energy is focused anymore. There may be a few whites who have relationships with Black people but fundamentally most whites do not feel that they should be in struggle with Black people. They have their own reasons for revolt. Despite this, I saw poor white kids fight alongside poor Black kids against the police. I don’t have romantic notions about what that means, but I do think it is a development that Black revolutionaries in the United States must take into account. We can’t ignore it. However, we must build on our own and take from the white left when it seems necessary.

The only thing I remain committed to after years of struggle is the spontaneous self-organized revolt of the Black masses. The uprising in the streets or in the prison remains the most advanced form of struggle. I hope that one day workplace struggles will take on a similar rebellious character that comes into conflict with the State, but that has not happened. Until then, I have left my dreams of Black community-run farms, a post-capitalist economy, cooperative housing, and all of that behind. I return to the dreams I had when I was teenager: dreams of Black revolt. I dream of Black uprisings all over the country in every town and every city. Modern day Maroons in Milwaukee. A resurrected BLA in Brooklyn. The forms will vary. But it will be a constellation of organized Black resistance, coordinating alongside one another but never leading the masses. I hope that I have enough strength, skill, and courage to fight alongside the Black masses with even more ferocity than last time. I hope that I find comrades who are ready to fight alongside me, even and especially when it becomes dangerous.

The fascist counter-revolution is on the rise with the attacks on our trans siblings, bodily autonomy, and “Critical race theory” in schools. It feels harder and harder to keep the memory of our Black revolt alive. I talk to my brother about it sometimes. He seems like he is preparing for the next moment of revolt as well. I talk to my friends, comrades, and lovers about all of this. Sometimes that summer feels like it was a dream. I’m not spiritual, but during those few days in May, I felt ancestors laughing at the revenge that Black people were getting on our oppressors, our jailers, and our exploiters. I only wish for that moment again.