Bager Nûjiyan

The Seeker of Truth

who insisted on another world

A Socialist fighter: Sehid Bager Nujiyan

Internationalism and the question of revolutionary leadership

Part 1: Experiences and shortcomings of global liberation movements

Establishment of the nation state as a new model of domination

Crisis of the progressive, liberal and socialist forces of Europe

a) The experience of the international.

b) The experience of the Spanish Civil War and the Internationalist Brigades.

c) National Liberation and the 1968’s revolt.

d) The Advance of Neoliberalism and the Anti-Globalisation movement.

e) The Zapatista uprising and the turning point of the natural society.

The question of revolutionary leadership

Communal experience and attempts of alternative life are prevented

The cultural roots as well as the resistance should be broken

The core of socialism is hidden in the natural society

Power and truth: Analytics of power and nomadic thought as fragments of a philosophy of liberation

From the free mountains of Kurdistan to the southeast of Mexico

1988 — ∞

Introduction

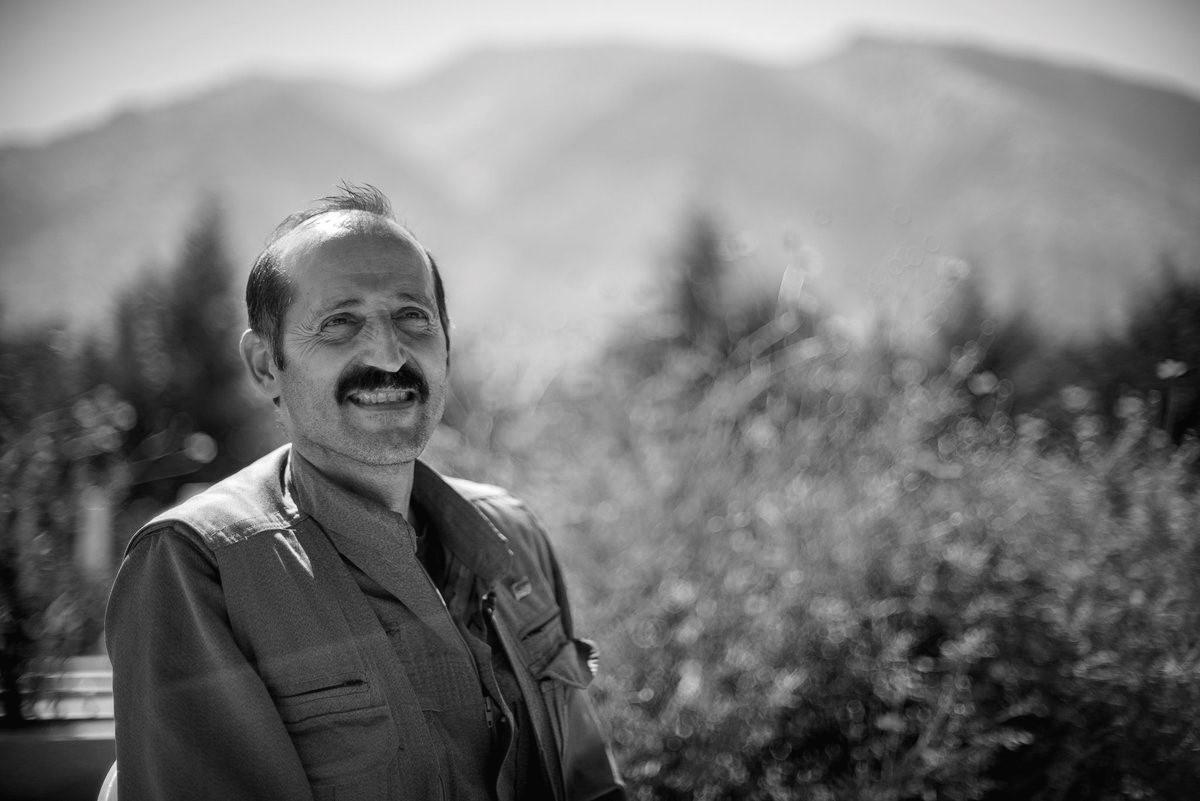

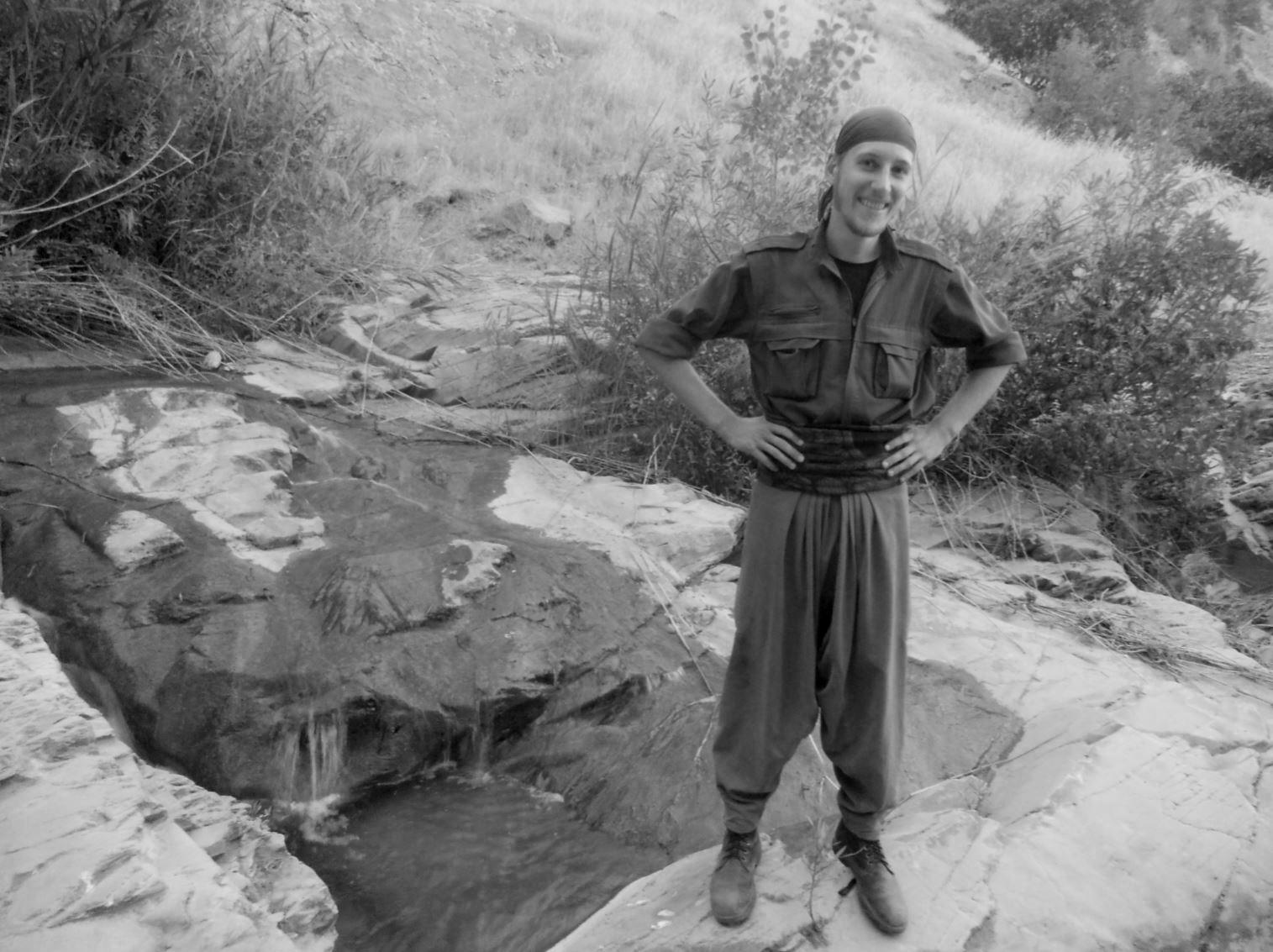

Our friend, internationalist revolutionary and guerrilla fighter Michael Panser, Bager Nujiyan (also Xefil vTyan) died and became immortal on December 14, 2018 in a Turkish air raid on the Medya defence areas in Southern Kurdistan.

Our hearts are full of pain, our heads are full of memories. Heval Bager was a friend who will remain in our memories especially with his insatiable and euphoric search for truth. His search and curiosity for revolutionary liberation movements has brought him to many places in the world. His greatest passion was to share his experiences and ideas with other people, to discuss them and find companions. In 2012 he travelled to Kurdistan for the first time, where his deep connection with the philosophy and revolutionary leadership of the PKK and Reber Apo began. He was driven by the idea of sharing his experiences and enthusiasm for the Kurdish liberation movement. He was convinced of the universal importance of the revolution in Mesopotamia for all freedom seekers, resistants and revolutionaries in the world. Therefore he managed to connect many people and movements with the liberation movement and to build bridges in a few years. In 2015 he himself returned to the revolutionary areas of Rojava to become part of the social change and also took his place in the defense of the Yezidi people in §engal. In 2017, however, it took him back to the liberated mountains of Zarathustra in search of wisdom, true friendship, struggle and free life in the PKK.

Also the internationalist community is undoubtedly the result of his efforts and at least one of many dreams that have come true. So many dreams have remained unrealised, but his search has become the search of many more. The seeds that Heval Bager has sown on his many journeys have begun to germinate and sprout everywhere. How we manage to appreciate the fruits and plant new seeds is now up to us who will with no doubt continue his struggle until victory. We owe it to him. It is difficult for us to do justice to our friend and comrade with words. Therefore we want to bring him up by sharing interviews and texts written by him with you in this brochure. We hope that they will make his life, his ideas, his dreams and his struggle comprehensible to more people and encourage the discussions he has always wanted so much. In this way we also want to contribute to ensuring that the revolutionary life of Micha, Xelil and, most recently, Bager Nujiyan will never be forgotten and will live on in our daily thoughts, speeches and actions.

The brochure is introduced with the text “A socialist fighter: §ehid Bager Nujiyan”, a Text written by the great philosopher and commader of Kurdistan’s mountains §ehid Qasim Engin. The text, “My name is Bager Nujiyan”, is the translation of a video interview he gave in 2017/18 during his participation in an academy in the mountains, in which he profoundly explains his process of becoming a revolutionary and joining the PKK. “Internationalism and the Question of Revolutionary Leadership — Realising a Heritage of Humanity” is a text that Heval Bager sent to us from the mountains last winter just before he fell. “Power and Truth: Power Analysis and Nomadic Thought as Fragments of a Philosophy of Liberation” was Michal Panser’s speech at the conference “Challenging Capitalist Modernity II: Dissecting Capitalist Modernity — Building Democratic Confederalism” in Hamburg from April 3 to 5, 2015. He wrote the letter “From the free mountains of Kurdistan to the southeast of Mexico: Towards a revolutionary culture of the global freedom struggle” shortly before his death in December 2018, in honor of the Zapatista Uprising. The final text of the brochure is the interview “Overcoming the Fear Reflexes”, which was conducted with him in the autumn of 2013 in the Qandil Mountains (at that time with the code name Demhat) on the way to basic education.

Heval Bager follows in the footsteps of other German revolutionaries such as Rosa Luxemburg, Willi Munzenberg, Hans Beimler, Ulrike Meinhof, Andrea Wolf, Uta Schneiderbanger, Ivana Hoffmann, Kevin Jochim, Gunter Hellsten and Jakob Riemer. In the life of Bager Nujiyan we see an example of internationalism and the search for truth, freedom and brotherhood of the peoples. We express our heartfelt sympathy to his family and all his friends. We transform our grief into anger, our anger into the responsibility to realize his dreams and efforts of another world, be it in Mesopotamia, Chiapas or East Germany. We remember all the fallen of the revolution who gave their lives for freedom. Their struggle is ours!

A Socialist fighter: Sehid Bager Nujiyan

Text written by Sehid Qasim Engm

The freedom movement is like a river. For years, exceptional fighters from all four corners of the earth have been flowing into this river. When the process of becoming society, also called sociality by scholars, becomes the ideological beacon of hope for humanity, Kurdistan becomes the home for a person from the other part of the world. A socialist from Kurdistan, as a revolutionary, also sees the other side of the world as one’ s home. As Che Guevara said in his time, “Above all, always be capable of feeling deeply any injustice committed against anyone, anywhere in the world. This is the most beautiful quality in a revolutionary”. These words grace the heart of every revolutionary. We know that Che Guevara was a personality with a spirit of uprising, against every injustice and the imperialist system that produces this injustice. This uprising is not only with words. It is also not a resistance that is without plan, aimless and frugal. Che’s uprising is taking responsibility for his inner voice and conscience. Che is dedicated to people. His devotion to people is dedicated to all humanity. Against occupation, exclusion, enslavement, oppression, and humiliation, he cultivates an infinite anger and wrath. He wants a just world. He is longing for a world in which human beings live like human beings, together and equal.

Our friend Bager listened to the voice of his heart and, in the spirit of good fellowship and friendship, followed the footsteps of Che and his socialist thinking. Our friend Bager took Abdullah Ocalan’s words, “Do not betray your childhood dreams”, as a basis for himself and followed his path in this sense. Isn’t the most beautiful description of the guerrillas the fact that they are children of nature? Or when one says that they are loyal fighters of their dreams and utopias? Could the description “those who have not betrayed their childhood dreams” be an even better one? Could it be that they are the ones who, in the spirit of the greatest utopias, set out into the free river of life and are inspired? By never bowing down, with their proud attitude, as the strongest weapon for the implementation of justice, they take their heart into their hands and rise up in resistance against death in the most difficult circumstances and conditions — aren’t the guerrillas, with their great faith and conviction for the creation of a free future, first and foremost, those who follow the dreams of Che? When we speak of Che, it is appropriate that our friend Bager Nujiyan comes immediately to mind.

I met Heval Bager in the spring of 2018. Before that, I had already heard of him. He wrote in a 15-page report, which he had addressed to the party, that he wanted to get to know the new paradigm from close up and learn about it, especially at the Central Party Academy. His proposal was considered to be a sensible one. His report was considered to be very thorough and profound. Overall, his report looked at socialist thinking, socialism and the new human being. The friends told us that he had shared extensive thoughts and deepening in his report. As I myself am also partly involved in the educational work, I also heard from Heval Bager in this context. Since I myself, coming from Kurdistan, grew up in Germany, I always have a special relation to the friends who came from Germany and also a special relationship and attention for the young people who came to the mountains of Kurdistan from other countries of the world.

We, as revolutionaries, see ourselves as part of the revolution worldwide. Therefore, our relationship and attention to internationalists of the world, coming to the mountains, has always been a special one. In this context, I always had a special relationship with the German friends, who came to the mountains, because we simply develop a relationship with each other in a natural way. Before I met the friend Bager, I had already been told a lot about him. However, in order to understand someone, to recognise someone, to form an opinion about someone, one has to get to know the person, to spend time together, to experience each other, to discuss — in short, and said in the Kurdish way, to live together. When one first saw Heval Bager, a calm personality, with strong ability to observe, to listen, to be a bit reserved when talking, but at the same time very enlightened, a person who knows where to say what, and in this respect, with a great awareness in life; in short, one saw a person with a personality and characteristics that are inherent to a revolutionary. When people discussed with Heval Bager and got to know him, they noticed that he had a profound knowledge and they recognized his belief in socialism. When we speak of socialism, we do not speak of socialism based on domination, state, and the dictatorship of the proletariat. The socialism we take as a basis is a socialism beyond the state, far from statehood and domination, and against any form of hierarchy and oppression. When we first met, we talked in German. The more I got to know him, however, I saw that the friend Bager could speak Kurdish better than many Kurds. His Kurdish was so beautiful and I noticed that he was teaching, reading and writing Kurdish at the Mazlum Dogan School as well as reading many incoming perspectives and explanations in fluent Kurdish in front of the whole school class. I was more or less aware that Europeans are well qualified to learn new languages. Even though I am not aware of the historical and sociological basis for this, I am aware of the fact that Europeans, and especially Germans, simply learn languages. But a person who is from a foreign place and teaches the fighters of this people in Kurdish was really of great interest and insightful for us. The moral evenings among the guerrillas are well-known. When we talk about moral evenings, we mean the following; every 15 days, each guerrilla unit organises a moral celebration in order to develop their own cultural skills. At these celebrations, some friends recount memories, some recite their own poems or the poems of well-known revolutionaries and socialists, some friends sing songs, some imitate the movements of other friends, and, if circumstances permit, there is also traditional dancing, theatre, or pantomime.

A revolutionary or guerrilla is not only a good fighter; since one’s struggle is for the creation of a new human being, it is first and foremost a cultural struggle. One is a fighter against every regression, exclusion, injustice, and inequality. Therefore, a fighter for being and becoming oneself. For this reason, every guerrilla should possess the precision and sensitivity of an artist. If one’s life is not artistic, then it is flawed and wrong, and it is incorrect as a guerrilla to use the wrong methods in life. As Che Guevara says, “The new man is only possible with the developed culture of the revolutionaries”. A developed culture is the love of freedom, and means a proud and dignified attitude against any form of oppression and humiliation! Perhaps you are now saying “why are you telling us this”; since in recent years, Heval Bager was always at the forefront and played a role, even before all others, both at the official celebrations and on special days and anniversaries held where friends participate with their tembur, guitar, drums, and their other instruments. Heval Bager sang revolutionary songs at the official celebrations, of course, in many languages and together with the other friends, and he shared dozens of songs one after the other with the others at the spontaneous moral evenings. Every friend watched with enthusiasm the internationalist revolutionary comrade who had come from another country. Especially, when he sang the song of Natalia, called “Commandante Che Guevara”, all the friends were clapping and singing along with all their hearts. Another song that Heval Bager always sang is the song “Se Jinen Azad — Three Free Women” by his friend Delila. This song was directly associated with Heval Bager in the school. Another song that everyone associated with him was a different song by Heval Delila called “Zilan”. At first I got to know the friend Bager in this way. Without a doubt, our getting to know each other didn’t stop there. The more people got to know him, the more his love and trust towards people became visible, as well as his connection with socialism, and without a doubt his deep love for the paradigm of Abdullah Ocalan. I hope it is not misunderstood when I say that the environment in which people grow up influences and shapes them.

Europe is the centre of capitalist modernity. It takes its centralism above all from the peculiarity that it does not leave a single person alone until they are integrated into the system. It is such a centralist attitude that looks down on other people around it. Up to the point that in the days when people from Africa were sold at markets, there was a discussion about whether they were people and whether their bodies felt pain or not! It is a modernity that is so convinced of itself that it was precisely very humanitarian people who put them in this position. Such forms of rapprochement ensured in the days that Christopher Columbus and his companions did the same thing against the indigenous Americans. At the same time, these undertakings, which deprived people of their humanity, are legitimised by biblical psalms. We can read about what happened in dozens of writings by popes and pastors. Thus, Europe is selfish and centralistic.

And this is exactly what it passes onto its society, or it is drilled into them. Its society and the individuals in it make them feel that they are very special people, thus making them supporters of its worldwide colonialism and silencing them. In short, European people look from above down onto people in Africa, Asia, and of course the Middle East. What I am talking about does not have its source in the good or the bad of human beings.

The system of capitalist modernity, through its educational system, does everything possible to put European people into this position. The deceased writer Immanuel Wallerstein did not say, without reason, “We are all a little bit children of capitalist modernity.” Although it is not their intention to exaggerate, to condescend others, to put themselves in a position of domination. All this is also visible in our units. However, I can say that I did not see even a little bit of selfishness and of egoism in the personality of Heval Bager. At school, he was perhaps the most communal of his friends, the one who shared the most, who interacted with everyone, who tried with all the strength at his disposal to find solutions to the worries of all; in other words, he was a societal role model from his own standpoint and was very modest with his attitude in life. If one looked at him in this way — if he had not had his red and blond colour — one would not have noticed that he was a German friend. Therefore, on his way to the mountains he had taken Che’s methods as a basis.

When Che said goodbye to his mother, it was not without reason that he had said: “Once again I feel beneath my heels the ribs of Rocinante. Once more, I’m on the road.” And when Che left Cuba and set out in the service of the revolution to a still unclear country in Africa, he said to Fidel, not without reason: “Other lands of the world are demanding my humble efforts.” A person who attempts to give their modest help in another country in the world must first become one with the revolutionaries on the ground and the society there in order to succeed in their efforts. The problem is not the backwardness or the progressiveness in these places; the problem is the injustice that happens there, to be able to feel it in a profound way, and thus, to find a little bit of a solution to their problems. This solution can undoubtedly be put into practice through modesty. The friend Bager, as much as he was enthusiastic about Che, he was also a good comrade of his. He was the kind of person who, in order to become a revolutionary, first travelled to the country of Che and then to many countries in Latin America. Besides German and English he also spoke Spanish. Language is ultimately the pivotal point of any exchange. To build a good relationship with people, you have to talk to them. To be able to speak, you have to know the language. Heval Bager recognised this truth early on and wherever he went, he learned and spoke the language in the best possible way.

A fundamental characteristic of a revolutionary is also to maintain contact and exchange wherever one goes. The great Turkish internationalist and comrade Kemal Pir said: “If I don’t see the faces of a hundred people every day, I cannot remain calm.” Looking into the faces of a hundred people means making connections. To become one with them in spirit. To feel one another from the bottom of the heart.

The comrade Bager, both through his exchange and through his unity in spirit, became a mature fighter of the mountains in a very short time. There is no doubt that one cannot always and everywhere meet such a comrade or meet such a friend whenever one wants to. Sometimes fate brings one into contact with such an angel-faced, tender, loving, sensitive, and considerate revolutionary, with great intellect, devoted in his efforts, and by his attitude a revolutionary. Our friend Bager was such a complete and chosen revolutionary and fighter. One is always on the lookout for such personalities and comrades and we long for them. He was the kind of friend that one patiently pushed the marbles of one‘s Tezbi chain onward until he said his words. He was the sort of person that one would walk for miles to see him, to look into his lively face, and when greeting him, embracing him deeply and extensively, and asking about his condition from the bottom of one’s heart and in deep connectedness. He was a personality that people do not forget. Although being revolutionary is something communal, such comrades are always with us in the depths of our hearts. If I am not mistaken, I had two lessons at the school where Heval Bager was staying, as well. One of them was on the history of Kurdistan. If we treat the history of Kurdistan as a lesson, we are of course not only considering the Kurds and Kurdistan. We are looking at the forces of democratic modernity, which take their place in the front against the authoritarian, violent, and state-based capitalist modernity. When we dealt with the slave-owning Roman Empire in this context, we especially evaluated the internal Christian movements that were in revolt against slave-owning Rome, as well as the movements from the North and the Germanic peoples who, in order not to become slaves, made their way to Rome, wave after wave, and took their revenge. Moreover, also the movements of the Teutons, the Alemanni, and undoubtedly also the Gauls, the Normans, and all those peoples who resisted against the slave rule of Rome. When we deal with them and evaluate them, we try in particular to understand their character. We try to understand and recognise the heritage of those who were not enslaved. From these analyses we try to draw the lessons that are necessary for us. Therefore, the deepening of the role of these movements is very important for us. On the one hand, we recognise the Germanic-Alemanni who do not surrender and do not bend, and on the other hand, the Germanic-Alemanni who are arbitrarily simple-minded, stubborn, narrow-minded, angry and know no one but themselves; we deal with these issues and discuss them. In these discussions, we accompanied our friend Bager into the depths of German history and asked him many questions.

What is very impressive is that no matter where in the world we live, if it is in a place where tribes have lived in a very pronounced way, then we resemble each other. Now, when Heval Bager stood up and explained a little bit about himself and a little about the Germanic tribes, the whole school was impressed by the fact that Germanic and Kurdish people, and therefore also Germanic and Arab people,

Germanic and Persian people, and other peoples with tribal traditions in other places of the world, resemble each other. If anything has changed, then especially in the last 200 years, that is, by nothing other than the age of the monster called the nation-state, racism, fundamentalism, sexism, and positivist ideologies which divide peoples and make them enemies to one another. The more we become aware of this, the more we embrace communal and natural life and develop more and more our utopia in the fight against racism and every other disease that the nation-state has spread.

As we connect everything, we see Che standing up in one part of the world and setting out on his way to Africa to bring about the revolution. The comrade Bager also comes from one part of the earth to another part of the world, to another country, in order to take part in the ranks of the revolution for the revolution and freedom of a people with the fighting spirit of his people. In this way we have discussed with our friend Bager in many lessons. He asked and the friends answered, the friends asked and he answered. Is being revolutionary not just about completing each other? If being revolutionary is completing each other, then the friend Bager gave the friends what he could give and the friends gave what needed to be given and to be enriched.

The more we saw the deepening that went on inside the friend, the further our discussions carried us to many places in the world. It soon became clear that the friend Bager had deliberately chosen and had come to the mountains of Kurdistan. In this way, I understood from him the great interest with which the paradigm of Abdullah Ocalan is being received, first in Europe, but also in many other places around the world. First since 1990 until today, he enumerates one by one the new quests that have developed in many places worldwide. Really, the more he tells, the broader my horizon and that of all the friends becomes. When one learns that one shares the same feelings and thoughts with comrades in another place in the world and lives in the same spirit, it expands the heart of each individual and broadens the horizon of each individual. Of course, there is research that we do and study, especially with many German friends that I have met, with whom I have discussed, with the many internationalists that I have met, I can clearly say that I have discussed Abdullah Ocalan’s paradigm most of all with Heval Bager. The educational journey was coming to an end. We have platforms before the end of education. Our platforms are the pivotal point for the awareness and change of each and every one of us. The criticism of friends for us and our selfcriticism for them — we understand life as worthy of criticism and we correct it. Platforms are our form of action for this. The most effective weapon of freedom fighters is criticism and self-criticism. The most fundamental goal of these platforms is to recognise for ourselves our characteristics that do not correspond to democratic modernity and to overcome them through criticism and self-criticism. The platform of Heval Bager took place as well. In the platform it became clear how much the friends appreciated and respected Heval Bager.

There is no doubt that a revolutionary oneself creates the respect that one is distinguished by. What formed the respect that was shown to him was his socialist and loyal personality. Perhaps it will strike you particularly, but I want to say it again. The reality that we freedom fighters defend in the highest way is that each one of us contributes to the revolutionary struggle with one’ s own way and colour. We want everyone to contribute with one’s own colour and culture. Whoever comes from the Arab society, with the colour of the Arabs, a Turk with the colour of the Turkish society, an Armenian with the colour of the Armenian society, a Suryoye participates with the colour of the Suryoye society. Or also Alevi, Yezidi, or another faith participates with the colours of their society.

Those who do not participate with their own colour in the struggle of the revolution cannot develop their full potential. Who instead imitates someone or some others cannot become conscious of oneself. Heval Bager had a mature and conscious attitude in his life, his approach, his language, his songs, and the relationships with his friends. In the platforms, his exemplary attitude became a real criticism for the friends who had not written their report in Kurdish. At the same time, he always reflected deeply on the reality of German society in his platforms, because every herb and every flower blossoms on its own roots. So, a German friend should not become a Kurd; to understand the Kurds, an empathic approach is undoubtedly necessary; accordingly, he has done so. Heval Bager was such a friend. He was so united with being guerilla and being revolutionary that his friends admired him. At the end of the educational unit, the music group Amara came to the celebrations of the Party’s Mazlum Dogan School.

Heval Bager sang dozens of songs in various languages with the group and inspired all his friends. As a friend who grew up in Germany, I asked him to sing the song “Roter Wedding”, which he did with great joy. After years, hearing the German revolutionary song “Roter Wedding” with the voice of Heval Bager brought me great joy and motivation. Almost all friends knew about the skill and abilities of Heval Bager. Among many talents, he played the guitar and violin beautifully. All students at the school saw and knew that he played the guitar.

The friend Bager not only played the guitar and violin, but he also beautifully sang songs to it. There was much discussion and a cultural committee was set up to create songs in many different languages. The basic aim was to write and sing songs in different languages about the great commanders and revolutionaries Erdal — Engin Sincer, Atakan — Suleyman Qoban, and Egid — Mahsum Korkmaz. For a whole winter, they wanted to create songs together with the music group Awazen Qiya to make these friends immortal like Che Guevara with his song. For this purpose, Heval Bager was also transferred to the cultural work for a certain time. When Heval Bager was in the cultural work, we also saw each other sometimes, but more than seeing each other we wrote to each other. Since he made very profound ideological evaluations, he sent me some texts to pass on. I had also suggested that he write texts about the paradigm. He also asked me for material and sources on German-Turkish and German-Kurdish relations to do research on it. I collected the material, requested it from archives, compiled it, and sent it to him.

At a time when we were full of expectation for the guerilla of Kurdistan and for the paradigm of democratic modernity, for its deepening, multiplication, and in this respect its new creation in cultural and artistic terms, planes of the fascist Turkish state attacked the Medya defence areas on 14th December 2018, and we received the sad news that he had fallen. It is appropriate to say that all friends who knew Heval Bager shattered. The words had dried up in their mouths! The severity of winters in Kurdistan is well known. In this month of heavy winter, the friends lifted the body of Heval Bager from the place where he had fallen and brought it to the cemetery of the fallen with an impressive memorial ceremony. When his body was buried in the cemetery, I was present. No friend was able to say a single word, but the tears in their eyes did not stop. Almost all the friends who buried him knew him themselves. The greatest anger of the friends was that a friend came from the other part of the world, reviving Che’s way and manner in order to fight for the revolution in Kurdistan and making his last journey among us. Fighters who join the revolution know that, once they take their steps in this struggle, revolution and being a revolutionary has its price.

Those who believe that another world is possible know without a doubt that this will not happen without sacrifices. Therefore, tens of thousands of beautiful souls have already dedicated themselves to the revolution in the freedom struggle of Kurdistan! The attitude of every revolutionary who has turned towards the mountains and towards the guerrilla is always hidden in these words of Che, in the feeling “Wherever death may surprise us, let it be welcome if our battle cry has reached even one receptive ear, if another hand reaches out to take up our arms, and other men come forward to join in our funeral dirge with the rattling of machine guns and with new cries of battle and victory.” As much as we are aware of this, our heart does not let go and does not accept that a friend from the other side of the earth came and fought shoulder to shoulder with us on our land for the revolution of Kurdistan, became the bridge of the revolution, was taken from us and had to leave. We never accept this. With the words of Emma Goldman, “Until the dreams are only a grape in the sunlight”, we, in the personality of Heval Bager, will continue our struggle at the highest level until we succeed to realise the dreams, utopias, and goals of all revolutionaries for freedom. Our words for life, our quest in life, and our benchmark in life always and at every step:

Hasta la Victoria Siempre!

An Sosyalizm to SosyaHZm! Either socialism or socialism!

“Jiyan an de azad be yan azad be!” “Life will either be free or be free!”

My name is Bager Nujiyan

My name is Bager Nujiyan, before that my name was Xefil Viyan. My family name is Michael Panser. I was born on 1st September 1988 in the city of Potsdam, in East Germany

My family are people with love for the country and for society, and at that time they were connected to the paradigm of real socialism. They are people of solidarity and they have an emotional connection. I believe that this is also a basis for my quest for the truth of the revolution. At the young age of about 14 years, I took an active role in the left and began my quest. The fact that I later got to know the PKK and the philosophy of Abdullah Ocalan is certainly also based on this phase. I participated in antifascist and leftist works in Germany. I gained a lot of experiences, but it became clear that these experiences were not enough on my quest. The setting of a liberal life, trapped in the constraints of the capitalist system, is very far away from the reality of the revolution. Thus, a departure from it and a further quest followed.

In 2011/2012, I got to know the first hevals, especially through the Youth and Women’s Movement. At first, getting to know each other did not involve practice, society or the reality in Kurdistan, but I first got to know the philosophy of Abdullah Ocalan. This is what my quest was: What are the weaknesses of the revolutionary quest we intended to carry out? With our theoretical and philosophical quest, we wanted to find and develop a liberation ideology. In the context of the European society, this was of course coupled with great difficulties. On this quest the way to Kurdistan opened up self-evidently. We got to know Abdullah Ocalan’s philosophy, we read and studied the translated books. In this time, we understood quite a few things: What we are looking for in Europe is what lies hidden — beyond Western civilisation and capitalist modernity — here in the Middle East, whose history got lost. Now these revolutionary achievements are developing anew here, offering new answers. At the same time when real socialism was collapsing in our midst, the way for a new revolutionary reality was paved in Kurdistan. On our quest we became aware of this. We made contacts and found our way to Kurdistan. We were beginning to understand one thing: The European problem is linked to the solution of capitalist modernity, the capitalist way of life. We must be aware that Germany is taking a leading role in the enforcement of the capitalist system of exploitation. We have also realised that no solution to this problem is possible without an internationalist perspective, a revolutionary perspective that overcomes closed borders.

In this way we slowly got to know the revolution in Kurdistan and I actually started to join the revolution seriously during this time. Since 2012 we deepened our thoughts further, we educated ourselves and tried to build a movement according to the values of the paradigm which was the content of our discussions. The experiences and weaknesses that showed themselves in this phase made one thing clear to us: that it does not work to participate just half-heartedly in the revolution. It was during this time that I made my decision. Being a true revolutionary must mean to think holistically. A revolutionary must be contemporary and must free oneself from the narrow-minded thinking of Eurocentrism and the perspectives offered by so-called modernity. Otherwise it is impossible to be successful. I gained this insight through ideological deepening and it meant that joining the Kurdistan Workers’ Party would make possible what I consider necessary: to build up the revolutionary strength. I realised that. It also became clear to me that a contemporary revolution cannot know borders. That would be impossible, revolution cannot work like that. The revolution in Europe begins with the revolution in Kurdistan. This connection definitely exists. Finally, the paradigm, which maintains its dominance in Europe in a close and crude way, imposes a liberal life on society and makes exploitation the absolute basis of its social order, is the very paradigm which today carries out the heavy attacks on Kurdistan. We understood that the first thing we had to do was gaining experience of revolutionary practice. In this way, I have devoted myself entirely to the revolution. Initially, I participated in internationalist practice, not only spreading Abdullah Ocalan’s thinking and the new paradigm in Europe, but especially learning to better understand capitalist modernity, which imposes itself as the last form of the male-dominant mentality of society. We did research on this, and we also developed a certain practice. Then I came to Kurdistan. At the centre of the revolution is the revolutionary change of consciousness. This is the basic task in the work area of the academies. That which you could not think before in society, because especially in the capitalist centre of Europe, thinking is divided and incoherent, and thus does not allow the emergence of a new consciousness. Thus, in the broad sense of a new paradigm, there is no quest. No new philosophy can emerge that takes life itself as its basis and wants to bring about a real socialism. We are talking about the defence of sociality, of love for society. The love for society is not possible in an exploited society.

It became clear to me that those who are on a revolutionary quest must go very far in their quest. They must consistently make their way to the substance. If we want to create a new realisation of socialist life, we must go where freedom is most widely realised. The mountains of Kurdistan are an extraordinary place. They offer the opportunity to experience oneself in practice. They make you realise what it means to be committed and to make an effort; and they make you understand the meaning of this effort anew. How deep are the traces that the system leaves in our way of thinking? All the problems and shortcomings in our consciousness that are created by the dominant way of thinking become clear in communal life as it is lived in the mountains. A communal living community, a revolutionary environment based on a common will to promote humanity and to free individual personalities from the constraints of the patterns of domination. This opportunity was really created here. The ruling system cannot simply attack this foundation that has been created. Of course, military attacks are taking place, but in the fight against the ideological and psychological consequences of the dominant way of thinking, we can create a new consciousness here through serious efforts and work.

That was the reason why I came here to the academy on my own request. In practice, I was able to develop my thinking. However, there was the necessity to go to this special place. After all, the academy creates an environment in which intensive and concrete work is carried out to raise awareness of one’s own dominant way of thinking and, at the same time, work is done towards its alternative. This is done in an environment that is characterised by communal life, communal work, exchange with one another; everything is there from shared values to mutual support. Real friendship is most clearly lived in academies. We analyse in a mutual manner very precisely which remains of the system of exploitation show up in the behaviour of a friend. It is not the case here that we have to separate the individual from the community, or that an individual has to adapt to the characteristics of the group. I can say from my time on the left that we were unable to resolve this contradiction. Finding the right balance between the individual person leading an inner struggle and their environment so that they strengthen and build each other up. It cannot be everything to recognise and protect a friend in the present form — because everyone in this society has been taught dominant ways of behaving. What does true friendship mean which we want to live and create here? We do not take a friend as what they have become and how they stand before me, but according to their goals and potential. It is our approach to develop each friend according to their strength. In this sense, we criticise each other and strive for methods of personality development. That is why I came to the academy and it is a very intense inner struggle. Through these efforts we create the foundation for this life. Because we are aware that the socialism that we want to create — that is, a new life, a life striving for freedom, an equal life that understands the value of the human being, that recognises the value of social achievements — is based on the potential of society itself and the wisdom and struggles that have been waged. If we want to build our dreams and utopias, where do we have to start? In our own personality.

Abdullah Ocalan stresses in particular the consequences of patriarchy. His analysis is transferable to the entire hegemonic civilisation by saying: If inner patriarchal masculinity is not overcome, socialism will always remain incomplete. A socialism that does not go into the substance, i.e. does not begin in the human being itself and does not create a new personality, free personalities, cannot bring about new achievements. In this way we evaluate the past socialism, the historical attempts that have taken place and their insufficiencies. There was a fighting society and a pioneering role developed, but the root of the problem was not grasped: What is a free human being? That is the fundamental question. What are the effects of domination in the human being? That is the fundamental problem. Since these issues have not been addressed, the system has repeated itself. There was no detachment from the dominant way of thinking. Although so many gave their lives in this struggle, great efforts were undertaken and so much blood and sweat were shed, these attempts may not have failed completely, but certainly did not achieve the desired results. We have to realise that. The life in the academy is the effort to free oneself. Revolution is not something that happens all at once. It is neither a single uprising nor a military victory. That is not possible. Revolution is a lasting condition that begins with a step, with a decision: the decision to participate in the revolution and to detach oneself from the ruling system; the realisation that the life we are forced to live in this system is wrong and that it is necessary to build up something new. Perhaps the revolution begins in every human being with an uprising, but in itself it is a lasting condition. If it does not become a process that is oriented along existing and future circumstances, then it is not a revolution. This is an uprising or a revolt, but not a revolution. This was often historically misunderstood and became an obstacle. We are building our foundation on this knowledge. Our future participation also depends on this and cannot be predicted. The path of the revolution cannot be designed and implemented according to a plan. History has shown that this is impossible. Therefore, the preparations we are making here are to build up a militant personality. What does it mean to be a militant personality? We must be prepared for everything; just as the current phase demands of us. Thus, we create holistic thinking, the method of understanding what the current situation is, the historical significance of the current situation, the dangers of the current situation in which we find ourselves and also its potentials. If we live this way and understand it that way, then it is not so important where we are going anyway — in which country we are active, in which part of Kurdistan or if we are going to another continent. In practice, of course, there are differences, but holism is decisive. To understand our ideas correctly, to develop our organisation further, the correct language, the correct form of communication and criticism — and in this sense to organise our lives correctly. If we carry out these things well and strive for good practice, appreciate the value of our efforts, and understand the efforts of our friends correctly, we can act accordingly. In particular, the importance of the effort and commitment of the martyrs who have given their lives in this struggle — if we understand all these points correctly, by creating the unity of thinking-feeling-acting, we can create militants who can carry out everything that will be necessary. That was indeed proven in the development of this revolution, wasn’t it?

A human being who is clear in their will and who really connects in their feelings and desires with the quest for freedom, the correct struggle to reveal the truth, can achieve anything! There are examples in our movement, and also in other revolutions before us there are tens of thousands of examples of revolutionaries, how they act, what efforts they make and how they participate. It is both our goal and our duty to take a stand for this and to act accordingly. I can say this much about that. A lot of success to you all!

Internationalism and the question of revolutionary leadership

Realising a heritage of humanity

Part 1: Experiences and shortcomings of global liberation movements

Resistance against any forms of oppression and exploitation and the search for freedom are social realities which no system of power has ever been able to eradicate. These social resistances and struggles for a life of dignity, freedom and equality re ect fundamental human values, such as conscience and morality, collective culture of remembering, social awareness and the art of political self-organization and leadership. All these struggles form a unity, a virtually unwritten history contrary to the history of centralistic-dominated civilization — a civilization based on state, class domination and the appropriation of social values. Since 5000 years this civilization has been in war with the nature, the free natural society and the heritage of a matriarchal culture. This civilization has always been forced to find the means in order to break the spirit of this social heritage of equality and freedom and to forestall the awareness of subjugated societies and their emancipation. In history, we encounter three major lines of social resistance: moral and social resistance in the tradition of struggling communities within (revolting slaves, free cities, rebellious peasants) or outside (indigenous, nomadic) centralized civilization; secondly, spiritual-idealistic and ethical resistance in the tradition of prophets, saints, philosophers, wise women, alchemists and resulting religious movements; thirdly, the tradition of Marxism-Leninism, which transforms the consciousness of social historical resistance into an organized-ideological form and political struggle.

Establishment of the nation state as a new model of domination

After a 300 year display of power, in the 19th century the system of Capitalist Modernity had reached its preliminary peak through Industrialism and Colonialism, subjugating the enslaved societies with extensive slavery, assimilation, and genocide. With the establishment of the nation state as a new model of domination, social consciousness was bound to the new system of domination through the logic of competition, a culture of war and chauvinism on the ideological basis of nationalism and thus diverted from social self-defense, awareness and resistance to exploitation and cultural alienation. Against this project of the centralized power civilization the socialist line of liberation struggle and resistance developed on the basis of the philosophical works of Marx and Engels. With the emergence of socialist movements in all industrialized countries, the idea of Internationalism became a strategic baseline of the liberation struggle. Against the chauvinistic logic of nationalism and hostility between peoples and the cold logic of global capital, the spirit of internationalism became the source of hope and utopias of the oppressed. This fight has been going on since then for 150 years with the proclamation “Proletarians of All Countries, Unite!”

Crisis of the progressive, liberal and socialist forces of Europe

In the 1990s and 2000s, when we began to follow the footsteps of this heritage of revolutionary tradition, Europe’s progressive, liberal and socialist forces were in deep crisis. After the collapse of Real Socialism, the system of Capitalist Modernity, above all the newly united German nation state, proclaimed its victory and the end of history. Against the German society ran a widespread operation to establish a neo-liberal regime of wage labour, bureaucracy and police state. At the same time, this was ideologically masked by fomented nationalism, therefore fascist gangs were on the rise. Thoughts and hopes, dedicated to revolution and socialism, met with massive counter-propaganda and defamation. The old national Liberation Movements of Europe in Ireland (Irish Republican Army) and in the Basque Country (Euskadi Ta Askatasuna) weren’t able to overcome their ideological deficiencies and were isolated from the system. The remnants of the urban Guerillas were forced into the underground or declared their self-dissolution. The heritage of the movements of 1968 had been largely assimilated by the system (such as feminist and ecological movements) or continued its marginalized existence (such as anarchist milieus and sectarian communist groups) in niches and subcultures. Heritage of revolutionary internationalism as a source of hope and certainty of victory

Without having utopias, resistance and struggle become impossible in the long run. We grew up in a social climate of ideological genocide — a genocide that was directed, above all, against the hope, the belief, and the spiritual-idealistic and moral resistance of society — in short, a genocide against the possibility of another life. During that time, joining the left-wing scene was often motivated by an attitude of rebelliousness, by emotional rejection of the social conditions and as a rebellion against the unscrupulousness and coldness of the system. Moral self-assertion and the resistance of the conscience naturally led into the ranks of the anti-fascist movement and to rejection of any national chauvinism. Anti-fascist self-defense against fascist gangs was the task. Despite the perceived immobility, the legacy of revolutionary Internationalism became a source of hope and certainty of victory for us. In a way, this universal line of social resistance was our secret leadership. Against a liberal system, a bureaucratic and police regime which tried to enforce deceptive normality, pacification and a life of alienation, spiritually we joined this internationalist line of struggle and assertion of socialist values. That secret leadership, still unconscious and without a clear expression, finally should lead us into the heart of the revolution in Kurdistan and brought us to the confrontation with the question of real revolutionary guidance. It is said that we’re able to understand our current situation only with regard to the history and the social struggles of any times. As we commit ourselves to the goal and struggle for a free society and universal human and socialist values, as we oppose a world of subjugation and exploitation, it must be clear to us that we can only be successful if we are linked to the experiences of all the previous revolutionary struggles. The system of Capitalist Modernity wants to establish its project of subjugation and exploitation on a global level. Therefore also the struggle for another world on the base of a life in freedom, equality and dignity must be fought on a global scale. The tradition of revolutionary Internationalism created a multitude of experience and values which continue their importance today and constitute important lessons for our fight and path. We can take these values of historical resistance with some examples to properly classify their basic understanding:

a) The experience of the international.

In the 19th century, huge worker’s movements emerged in the industrialised countries of Europe and North-America. At the beginning of the 20th century, the contradictions between the imperial powers led to the outbreak of the First World War. This became the opportunity for the system to massacre millions of workers on the battlefields and therefore anticipate a socialist revolution. The reformist social-democratic forces joined the line of war and national chauvinism and so threw themselves into the arms of the imperialist forces. Against the politics of war and collaboration, Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht defended in Germany a radical attitude of international solidarity and the alliance of all workers and oppressed peoples against the capitalist system. With the victory of the Russian Revolution under the leadership of the Bolsheviks and the organisation of the Communist International (ComIntern), for the first time a leadership organisation emerged which committed itself also to supporting socialist revolutions in other countries. The paradigm of Marxism-Leninism based on Hegelian philosophy was fouled by the idea of the nation-state in the form of the dictatorship of the proletariat continued its existence in Real Socialism. This idea of a society able to organise itself in the form of a state and thus move towards freedom is until today one of the biggest mistakes of Marxist tradition. The reference to the state as well as Stalin’s principle of “Socialism in one country” made the ComIntern quickly turn into a tool of power for the industrialised states who used this to enforce their diplomatic-political and military interests. Endless militants and revolutionaries committed to the idea of the International became victims of Stalin’s politics of power, which betrayed internationalist values and handed over hundreds of Communists to Nazi Germany.

b) The experience of the Spanish Civil War and the Internationalist Brigades.

In 1936, the societies of Spain started broad resistance against the fascist military coup. The workers, peasants and women’s response to the coup attempt was the social revolution based on anarchist self-organisation. A council system and self-defense forces emerged.

To an appeal of the antifascist government of the Socialist Party and the ComIntern, the answer of thousands of Communist and Socialists was to pour into the country to join the International Brigades.

The defeat of the antifascist forces can be exemplified in two points: First, instead of supporting the revolution as well as broad social mobilisation and organisation of self-defense through the militias, the socialist government insisted on s conservative and centralistic politic which propagated “first the defeat of the fascists, later the social revolution”. In this way, achievements of the revolution were eliminated, brought under government control and thus weakened the spirit of resistance of society.

Second, the attachment of the International Brigades to the socialist government and to the praxis of the ComIntern under the direction of Stalin ensured as a diplomatic weapon that Spain’s fate was sealed at the level of interstate power politics. The two-edged role of the International Brigades and the undermining of the antifascist forces through state power politics both internally and internationally turned Spain into a painful experience and a significant example of international liberation struggle.

c) National Liberation and the 1968’s revolt.

After the Second World War, in many countries of Latin America, Africa and Asia national liberation movements against colonial occupation emerged. In this phase of international liberation struggle important experiences in both theory and practise could be gained; also important victories were won in liberation wars against imperialist Hegemony and occupying armies. In the sixties and seventies, an internationalist spirit developed that gave self-confidence and spirit of resistance to societies under occupation and foreign domination. Awareness of the unity of all liberation struggles was also manifested in the alliance of progressive and socialist forces within the metropolis, which in solidarity and mutual support were related to anti-colonial liberation movements and, by supporting the Soviet Union, formed an anti-pole to the hegemony of the leading capitalist states. Mao’s guerrilla war strategy had brought the Chinese Revolution to victory. The nature of guerrilla warfare as a prolonged people’s war, their own form of organisation and tactics developed into the recipe for success of oppressed societies in the struggle for liberation against technologically superior occupation armies. In Cuba, the brothers Raul and Fidel Castro proved that the Guerilla concept is transferable. As the Guerilla gained its strength out of village communes and the communal base of society, also organised itself decentralised and above all, gave form to the desire for freedom and will of society for self-determination, in many countries the occupier armies could not withstand a long time.

In France, broad networks emerged in support of the National Liberation Front (FLN) in Algeria. In connection to the liberation struggle, the work of the psychologist Frantz Fanon was particularly important. His work The Damned of the Earth is a manifesto of anti-colonial liberation. Above all, he devoted himself to investigating the psychological effects of colonial rule and worked towards strategies of liberation. Only by expressing one’s own identity and a collective consciousness of resistance can the psychology of slavery be overcome and liberation consistently achieved. From the experience of social education work in Brazil, Paolo Freire developed his concept of education as a practice of freedom. In particular, it is important to understand how the struggles and experiences of this time and epoch of the freedom struggle respond to each other, mutually reinforce each other and create an internationalist awareness of the unity of all these struggles. With the Vietnam War and the 1968’s youth revolt, this epoch of liberation struggle reached its peak. The unity of struggle in the metropolis (in the industrialised countries of Western Europe and North America) and countries under colonial occupation establishes a shared awareness of the possibility of global liberation. The Vietnamese people becoming an army and the development of the Urban Guerilla are important experiences and a deepening of the strategic militancy of the struggle. The struggles and attempts of 1968 were not only the search for an alternative to the capitalist system of domination, but also tried to find new ways besides the mistakes and defects of Real Socialism and the Soviet Union. From these attempts, only the PKK could assert itself, become a sustainable force and develop its own revolutionary leadership principle. The military victories of national liberation movements could not prevent the capture and incorporation by the capitalist system. Liberation movements arose in the nation-state model of the Modernity and could not provide a social alternative to the dominant mentality and organisation. The movements of the metropolis, such as the Black Panther Party, the Red Brigades, and the late generations of the RAF (Red Army Fraction), could be isolated in the absence of retreat areas and were at last undermined by the concerted attacks of secret intelligence counter-insurgency programs.

d) The Advance of Neoliberalism and the Anti-Globalisation movement.

In the 1980s, the leading states of Capitalist Modernity began to implement their concept of global neo-liberal rule, which aims to appropriate and integrate all areas of society into the order of finance Capitalism.

As a new global project of control, Green Belt politics and the creation of political Islam were promoted — in the 1980s as a containment of the Soviet Union — frozen in bureaucratism and conservatism-, and after its collapse as a project of global reorganization. With the creation of Gladio, secret NATO counterinsurgency programs were launched, especially in Germany, Italy and Turkey. In Latin America and elsewhere, counter-revolutions have been carried out through military campaigns, paramilitary warfare and with the help of agents. With few exceptions, such as the liberation movement in Kurdistan and the Colombian guerrillas, revolutionary forces worldwide got into a defensive position. In the metropolis, left-wing forces tried to think of alternatives and to process and overcome mistakes of earlier revolutionary attempts particularly through theoretical work and analysis.

The leading G8 states pushed ahead their project of global hegemony on summits, while a globalisation-critical movement formed with counter-summits (such as the World Social Forum of Porto Alegre) and summit protests. Despite all attempts, the Anti-Globalisation Movement couldn’t formulate a persistent alternative, couldn’t develop an effective system of self-defense or couldn’t overcome the own protest character. An important experience is the Peoples’ Global Action network and its model of organisation. A network of national and regional committees has been created on a global level to coordinate and agree on summit mobilisations and perspective discussions. This network brought together diverse movements from indigenous communities, Australian Aborigines and Indian Communists to European anarchists, Russian feminists and Canadian eco-activists. Because of their potential to form a new internationalist force, the movement and leading activists faced a massive assault and torture by police and intelligence agencies at the G8 summit protests in Genoa, Italy, which stifled the movement before it could take a clear form.

e) The Zapatista uprising and the turning point of the natural society.

As the Zapatista Army of the National Liberation (EZLN) went to uprising at New Year 1994 in southeastern Mexico, it immediately attracted the attention of the world public. The Zapatista uprising began on the same day, when between the US, Canada, and Mexico, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) came into effect. By this means, it got the symbolic power of a struggle for dignity and hope against both a system of total domination and neoliberal slavery and exploitation. The uprising, based on rural indigenous village communities, draws on a deep mythological tradition of natural sociability and 500 years of struggle against colonial subjugation, exploitation and genocide. It is particularly inspired by the struggle of Emiliano Zapata in the Mexican Revolution of 1910–1920, who represents as a role model and epitomizes the revolutionary leadership of the oppressed. The Zapatistas draw their strength from the combination of communal values and natural sociality with socialist philosophy, an organised structure of militants, guerrilla struggle and militia system as a self-defense concept. Against the Mexican neo-liberal and US-compliant government (the “bad government”), the movement has built its own system of democratic autonomy of councils, municipalities, women’s movement, education and health system as “good government”. The 1994 uprising was preceded by ten years of clandestine organization and preparation. From a thinking based on social reality and mythological traditions, self-governing principles had been developed. There are based on holistic inclusion and change, and expressed as principles such as “questioning progress” (as a method of uniting theory and practice) and “obeying commanding” (as a principle of leadership and responsibility). The struggle of the Zapatistas is based both on a deep culturindigenous heritage and a corresponding identity, as well as on broad national, regional and international alliances against the system of centralized and imperial civilization. “The Other Campaign” was launched as a national campaign to democratize Mexico. In particular, it is instructive how the Zapatistas consciously and creatively use media, visibility and clandestinity as a mechanism of self-defense, tool for alliances and inspiration of movements worldwide as a strategic weapon. Since 2013, the “Little School” project has been used to create internationalist Zapatista academies, while on the Internet, seminars on autonomy and revolutionary experience have been organised for allies. The Zapatist struggle therefore plays a strategic role for the Latin-American societies. The role and location of Mexico vis-a-vis the United States is comparable to Turkey’s role and position vis-a-vis the EU and its stability. Accordingly vehement, is the attempt of the system to stifle the fight of the Zapatistas by economic projects against the social basis of the movement and warfare of low intensity using Contras. Despite all attempts, the Zapatistas resist and represent today one of the most important and leading projects for building a Democratic Modernity.

Part 2: The continuity of the Internationalist Liberation Struggle and the question of revolutionary leadership

What we want to show is the continuity and richness of experiences of the internationalist liberation struggle. The tradition of revolutionary Internationalism represents in a sense the conscious line of historical social resistances and the actualisation of it. In practise, the struggle for freedom was always internationalist. Especially the rich tradition of resistance of Middle Eastern societies, from Zarathustra, Babek and the Churramites, to the attitude of Mahir Qayan and the revolution in Kurdistan, impressively demonstrate this millennium-old line of social struggle for freedom. The awareness of the values and achievements, the experiences and the unity of these international struggles forms the basis of a socialist consciousness and the project of a democratic modernity. The awareness of the values and achievements, the experiences and the unity of these international struggles forms the basis of a socialist consciousness and the project of a Democratic Modernity.

The question of revolutionary leadership, which can help a society to renew itself, has been the subject of discussion and controversy since the emergence of the socialist movement in all attempts and break-ups of the freedom struggle. A society that is linked to its cultural heritage, that has moral standards and political awareness, is able to lead itself, to organise both basic necessities and self-defense, and to sustainably enable social life. A society that does not have the power of self-leadership is always subject to subjugation, occupation, exploitation, alienation, assimilation and genocide. Systems of power of all times have always sought to alienate society from its self-guiding power and keep it unconscious in order to exploit it for its own purposes. The first and most vehement attack of the system of domination is aimed at the woman and her social role as natural leader, moral authority and organisational center. The woman embodies the oldest form of social leadership. In all resistances and movements of social renewal, the role of women was a leading one, and the success of these struggles was tied to the participation and strength of women. Just as the degree of freedom of a society is measured by the freedom of women, so every project of domination must first subjugate the woman in order to crush the social moral power of self-defense. The resistance of revolting slaves, of nomadic and indigenous societies, represents a from of cultural resistance with underlying values of earliest communal self-leading and the memory of a life in dignity. Religious resistance and the tradition of prophetic movements are based on the assertion of moral values and ethical conduct of life that questions the totality of domination. Both historical lines, the communal and the ideational-sentimental tradition of resistance, were not able to withstand the capture and assimilation by state centralist domination in the long run. Marxist philosophy and socialist movements sought to put the question of revolutionary leadership on a conscious political and organized foundation. For the first time, with the idea of the Communist Party as an organized initiative force and the dictatorship of the proletariat, the idea of revolutionary leadership was deliberately negotiated as a strategic issue.

The question of revolutionary leadership

The fundamental problem of all revolutionary movements and the question of their persistent success revolve around the revolutionary leadership — none of the previous movements was immune to being handed over to the system because the question of revolutionary leadership remained unanswered. The principle of revolutionary leadership is the goal as well as the fighting strategy of a social revolutionary movement, it decides on the form of organization, political guidelines and tactics of struggle. Although the goal of a free, moral, value-oriented, and communalist society is clearly formulated in anarchist philosophy, anarchist movements in practice had problems of sustaining organizational unity, long-term strategy, and self-defense, and transforming their struggles into persistent social renewal. The defeat of the Spanish Revolution as a result of state intervention and appropriation points in this direction. The problem of defense and persistent revolutionary leadership is also reflected in the experience of the revolt of 68: The leading figures of the movements, in Turkey in person of Mahir Qayan, Ibrahim Kaypakkaya and Deniz Gezmi§, in Germany in person of Rudi Dutschke, were eliminated by provocation and assassinations, which meant for the movements the loss of their initiatives. The fragmented character of both the German and the Turkish left is the result of the loss of one’s own revolutionary leadership. In the tradition of Marxism-Leninism, the question of revolutionary leadership was tied to the appropriation of the central power and the taking over of the state. Objectively, adopting the state form of organisation always meant imprisoning society in static forms and alienating it from its own power of awareness and moral self-correction — centralised domination, whether in the form of the bourgeois nation state or the dictatorship of the proletariat, means for the society always to be forced into passivity and a legally organisational framework. As a result to the reference to the state, Real Socialism transformed social revolutions and societies from Russia till Vietnam and Nicaragua, that were in a condition of anti-imperial liberation struggles into bureaucratic apparatuses that narrowed and blocked society’s search for articulation and freedom. A memorable and negative example in this respect is the experience of the Prague Spring, which was as a cultural and communal movement crushed by the Red Army in 1968. Another problem of Marxist philosophy is the notion of the goal of a socialist society: historical progress follows the idea of a linear movement that necessarily leads from capitalism to socialism.

The Marxist historical understanding was not able to overcome the philosophy of Hegel and therefore not in the position to define correctly the field of tension between the centralised-domination modernity and the line of the historical society, that always acted as a anti-pole in contradiction and spirit of resistance against the civilised modernity. In a sense, the misfortune of Marxist philosophy is that at the time of Marx and Engels’ work in anthropology and archeology, knowledge and the state of research on natural societies and the Neolithic as sources of human society and culture were not yet as advanced. From this void of historical knowledge, shortcomings followed in the understanding of society, especially regarding the original character of society as a communalist community, which is well able of self-leadership on the basis of moral collective memory and political confederal organization without state superstructure. Especially regarding the position of the woman as original central source of power for society, regarding the understanding of social freedom and equality, the Marxist paradigm was therefore open for misunderstandings. The struggle for social liberation and awareness lies in a sense in the negotiation for the right method of leadership, in the question of the right way to live. Both in the collective, but also in the personal perspective towards the way of life. A socialist method of leadership has to be stronger than the guidance of the system that just aims to assimilate and to pacify the society. A socialist leadership has therefore the responsibility to convey the correct understanding of the social reality as well as a persistent and importance giving method of understanding the truth. Above all, a revolutionary leadership method must be a way of life that conveys principles and standards of daily life to militants and revolutionaries. Regarding this point, almost all classic left-wing movements (with the exception of a few natural leaders) were subject to the system’s command and attraction in the long run. It is important to realize that a form of lifestyle that is unable to develop a proper understanding of struggle, society, socialism, and truth can not solve the problem of an alienated and dominated society.

A lifestyle that remains in a purely oppositional attitude and can not implement its own paradigm of socialist collectivity in life will objectively prolong the dominated and alienated situation and contribute to the support of the system. Many classical left-wing currents and movements, such as feminist and ecological movements, the academic left, and above all the state-socialist version of modernity, took the position, despite revolutionary intentions, to rejuvenate the system of capitalist modernity, since it did not take a profound and holistic approach to oppose an alternative to the system’s leadership. In this way, Real Socialism was condemned to prolong the crisis of the system of Capitalist Modernity by a 150 years.

Communal experience and attempts of alternative life are prevented

Since the offensive of the system of Capitalist Modernity to assert and expand its own hegemony, and the transition to finance capitalism in the early seventies, it developed the the form of leadership called Bio-power. This method no longer relies, as before, primarily on the exploitation of social surplus value by industrial production, but aims to transform all social spheres of life into sources of capital accumulation. From the influence on the social desire over education, health and art up to interpersonal relations, the life itself becomes a commodity and is subjected to the logic of the capital. The leadership of Bio-power is most evident perceptible as financial commander of the ubiquity of the money, which organizes the social reciprocity even into friendships and family relationships. In this way, an individualistic and selfish, anti-communal lifestyle is imposed on society. The system creates a totalitarian culture of material values that transforms every social value and meaning of communal life into something dead, purely material and overlays this with the lack of culture of limitless consumption. With this method, the truth (as a category of thinking, of the perception of reality) is stifled within the limits of the purely material, the measurable and the positivist scientific. Life loses all uniqueness, is ripped of every secret, without search, and becomes the pure administration of the everyday and banal. The emptiness that this kind of enforced life had left in our lives since the Nineties awakened dissatisfaction with the existing and set us on the move. We looked for answers and ways of how the right struggle for liberation could be led, how to live a proper life. We were aware of the disgusting nature of the system, but the intangibility of the domination of Liberalism and its ideological hegemony prevented us from thinking of real alternatives. The nature of liberal living, forced careerism, opportunism and individualism prevent communal experience and condemn all attempts of an alternative life to be pushed into isolation and marginalization. We searched for ways out by exploring historical internationalist struggles, revolutionary theory, and forms of life and culture outside the European metropolis. It is said that in the shadow of fortresses and cathedrals, and under police control of the system’s henchmen, free thinking is difficult, and so we left our old world. Any search for freedom, any attempt at deep understanding leads back to the source, and so our search led us to Mesopotamia, the site of the first great revolution of humanity, the source of culture, the revolution of language, thought and settlement.

We learned that in the mountains, plains and cities of Kurdistan, the tradition of revolutionary internationalism continued, and here the struggle for a socialist society was linked to the resistance of the old, natural society, in which the power of the woman and the culture of the mother goddess still acting. Above all, in the struggle of the PKK and in the person of Abdullah Ocalan, we encountered a deep revolutionary leadership that far exceeded the limits of classical leftist movements and embodied the possibility of true revolutionary life.

The cultural roots as well as the resistance should be broken

Of course, the emergence of revolutionary leadership in the form of the Kurdish movement can not be separated from the current shape of the Capitalist Modernity’s project of domination. Nor is it a coincidence that the search for a way out of Europe’s social crisis leads to Mesopotamia (the historical heartland of the Neolithic revolution between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers). The emergence of the revolutionary leadership in Kurdistan is an answer to the same attack of the system. The offensive of Capitalist Modernity against the Middle East represents the latest and most recent wave of attack of the system, after having asserted its leadership over the societies of Europe and North America over the past 400 years. The system of Capitalist Modernity is always forced to foster the accumulation of capital and to bring new sources to the system. After the colonial era and the colonial subjugation of three continents since the 16th century and industrialism in the 19th century, only the societies and areas of the Middle East that are not fully integrated into the system of regimes of production and creation of value have remained in the age of financial capitalism. The biggest obstacle to the system’s ability to gain a foothold in the region is its deeply rooted social culture, dating back to the Neolithic period and its ideational-sentimental culture. The leading forces of modernity (especially the leading NATO states USA, Britain, Germany and France and supranational institutions) are well aware that the Kurdish societies are to the fullest extent root and source of the old non-state, value-oriented culture. For 200 years (beginning with the Napoleonic maneuver in Egypt and the establishment of de facto control over the politics of the Ottoman Empire), a comprehensive strategically-led war of varying intensity is taking place against the societies of the region, which aims to cut off the cultural roots of