Bowers & Lawler

Anarchism as a Methodological Foundation in Mathematics Education

A Portrait of Resistance

Anarchism and the Researcher: Conceptualizing Anarchist Methodology

Anarchism and Research: Tracing The Possibility Space of Anarchist Method

Collaborative action and design research

A large swath of research in mathematics education claims to serve an equity agenda. However, too often this research is conducted atheoretically, failing to disrupt the worldviews that produce injustice and oppression, for both the researcher and the reader. Responding to this commonplace divergence of intent and impact, we propose a methodological approach that anchors research and praxis in a sociopolitical foundation of anarchism. We seek cohesion of theory and practice by consciously demanding that values common to the equity agenda—cooperation, mutual aid, and freedom from hierarchy—provide explicit grounding for method and methodology.

Whenever we call something mathematics education research, we either reify existing lines along which something is included or excluded from the foam of mathematics education research, or we perturb them. We can blow additional air into bubbles that exist, we can reach in with our fingers and pop them, or we can blow—and hope—that a new bubble will emerge. The beauty of it all is that we cannot be sure what will happen. We can, however, be sure that things can change. Mathematics education research has not, and does not currently, have a fixed definition. Mathematics education research does not have a fixed, and proper, object of study. And it should not. (Dubbs, 2021, p. 165)

Mathematics education is not a monolith with a singular identity. Instead, mathematics education is an amorphous collection of bubbles—conversations are raised or dropped; motivations expressed, rescinded, or revised; new conversants join a conversation while others leave, or perhaps just daydream for a time… Mathematics education is froth and foam, and we may at any moment shatter or breath new life into its constituent transience (Dubbs, 2021). At the same time, mathematics education research is commonly atheoretical, a term we use here to reference the commonplace disconnect (or lack of conscious interrogation) between researcher worldview and researchermethods(Stinson, 2020; Walter & Andersen, 2013). Framed in Dubbs’ metaphor, researchers do not always know which bubbles they are growing, and which they are dissipating.

The purpose of this manuscript is thus twofold: To breathe new life into a bubble still not often explicitly explored in mathematics education (Bowers & Lawler, 2020), and to do so in a way that might give readers lost in the translucence an opportunity to notice and explore aspects of their own worldview that might previously have operated below the level of consciousness. Thus, in this text we explore the methodology—the combined worldview and method—of anarchist mathematics education. In so doing, we aim to contribute to the reflective awareness of ourselves and others regarding the bubble(s) that comprise anarchic methodology, as well as offer a counterpoint from which those of different perspectives might consciously notice aspects of their own worldview and its interrelationship or conflict with their methods (Wheatley, 2005).

Anarchism and the Researcher: Conceptualizing Anarchist Methodology

In the end, considerations of ontology, epistemology, ethics, values, subjective and ideological grounds, and so on—that is, the researcher’s worldview—should precede not follow theoretical and methodological considerations. Explicitly and critically interrogating one’s worldview should be the starting point of any research project. (Stinson, 2020, p. 13)

We also noted that students and scholars (often of European descent), on hearing us present our work, would ask how our methodology differed from theirs. In response, we asked them to articulate exactly which aspects of standard quantitative methodologies they wanted us to contrast Indigenous methodology with… What intrigued us about such questioning was not that our audience wanted to know how an Indigenous quantitative methodology differed from other methodologies, but that they wanted us to provide a coherent picture of our methodologies when they could not provide a coherent picture of theirs. (Walter & Andersen, 2013, p. 43)

Anarchists and (mathematics) education researchers generally share convergent interests regarding social (in)equality—that is to say, both groups share a concern over noticing inequality and making efforts to pursue social justice. “Anarchists are principally and generally motivated by the presence of social inequality and domination to take action” (Williams, 2012, p. 10), and educational researchers have now spent decades producing such a volume of research noticing/analyzing inequality that printing the aggregate work (even of only the subset written exclusively by abled white cis-hetero men) might well blot out the sun. However, when looking beneath the surface, differences quickly materialize. Of particular note for our purposes, anarchism has clear theoretical (and, dare I say, methodological) underpinning, while substantial work in mathematics education is functionally atheoretical (Stinson, 2020) in the sense defined previously (i.e. commonplace disconnect, or lack of conscious interrogation, between researcher worldview and researcher methods). This atheoretical quality is, from our perspective, deeply concerning—even extremely well-intentioned equity work can actively operate against the goals of social justice when the researcher’s worldview isn’t consciously and critically interrogated, as for example in the case of work that fetishizes gap-gazing (Gutiérrez, 2008) or any of the multitudinousworks that tacitly honor and reify the violently constrained imaginations of neoliberal Capitalism (Cabral & Baldino, 2019), cis-hetero patriarchy (Moore, 2020), and white supremacy (Martin, 2019). Positivist framing and its analogues have been discarded but not replaced (Walter & Andersen, 2013), leaving static—white noise (pun intended). Thus, we seek in this section to utilize the strengths of anarchism to outline a broad but firmly grounded methodological approach for (mathematics) education research, one which we offer to those still lost in the static.

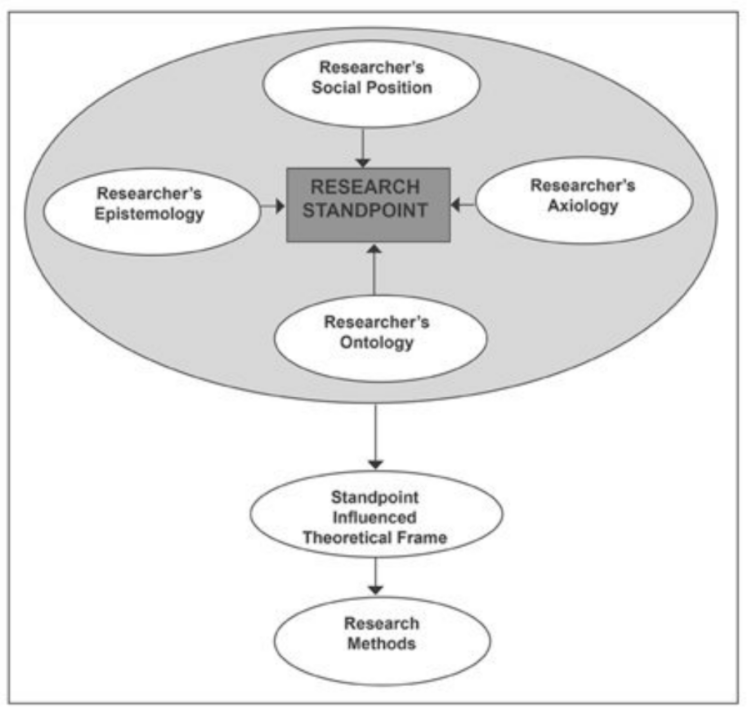

To frame this chiaroscuro sketch of anarchism as methodology, we will employ the framework of Walter and Andersen (2013), visually represented in Figure 1. Thus we begin with four key aspects of the researcher’s worldview, which we will explore in this order: axiology (philosophy of ethical and aesthetic value), ontology (philosophy of being), epistemology (philosophy of knowing), and social position. These four are deeply interrelated and can’t be meaningfully separated (in spite of our pragmatic choice for constructing this section), and we will surface a few of these connections as we go. Our decision to start with axiology rather than ontology might seem surprising, as the latter is suggested by the lingering positivist-shaped void many of us have experienced enculturation towards, but in truth the precedence of ethic is entailed in the selection of anarchism for our methodological framing (Bowers & Lawler, 2020)—anarchism is a methodology and lifestyle (Vellanki & Fendler, 2018) built upon a choice of ethical value. In short, anarchism is minimally built on the values of cooperation, mutual aid, and freedom from unjustified, coercive hierarchy (e.g. ablist cis-hetero patriarchal white-supremacist Capitalism).

Axiology

Axiology, the study of ethical and aesthetic value, deals with the intrinsic and extrinsic principles that shape our perception and practice. Axiology palpably shapes every aspect of research: our sense of how we do good while doing research, our sense of what questions are interesting or worthwhile. Adding complexity, these values exist not just in the researcher, but also separately and rarely identically in the products and practices of research itself (Walter & Andersen, 2013).

As an articulation of ethics, anarchism is a mode of human organization with social self-determination, rooted in the experiencing of daily life. Anarchism, specifically social or communal anarchisms, holds a conceptual connection between freedoms of the individual and social equality, emphasizing cooperation, mutual aid, and rejection of hierarchy. “I am not myself free or human until or unless I recognize the freedom and humanity of all my fellow men” (Bakunin, in Suissa, 2010, p. 44). Anarchism values humanizing relationships that minimize if not eliminate coercive structures and interactions, taking seriously the hope for an equal and free society.

Bakunin (1971) argued that the human is only truly free when among equally free humans; “the freedom of each is therefore realizable in the equality of all” (p. 76). Concisely, to embrace any form of anarchism is to express profound skepticism toward skewed, coercive, and exploitative power relations, and to reject all forms of oppression, including those of class, race, gender identity, religion, etc. Anarchism is the absence of hierarchy, organized on core values of cooperation; mutual aid; and freedom from unjustified, coercive hierarchy (e.g. abled, cis-hetero patriarchal, white-supremacist Capitalism). These three principles, taken together, efficiently convey the foundation of anarchist worldview: We work together, we do so for the benefit of all, and we treat coercive hierarchies with extreme skepticism (we seek liberation, the antithesis of coercion). Note that anarchists do not reject all hierarchy per se; expertise, for example, can still be recognized, though with a different axiological flavor than is commonly seen in discourse-at-large. As Bakunin (1871) reflected:

Does it follow that I reject all authority? Far from me such a thought [SIC]. In the matter of boots, I refer to the authority of the bootmaker; concerning houses, canals, or railroads, I consult that of the architect or the engineer. For such or such special knowledge I apply to such or such a savant. But I allow neither the bootmaker nor the architect nor savant to impose his authority upon me. I listen to them freely and with all the respect merited by their intelligence, their character, their knowledge, reserving always my incontestable right of criticism and censure.

Ontology

Ontology, the philosophy of being, deals with how we perceive and operationalize a notion of reality. Far from concrete or immutable, our sense of what is real and how we respond to that reality can be fluid and even contradictory. Ontology establishes invisible boundaries around what is considered possible or meaningful, made visible in the ongoing clash between marginalized ontologies (e.g. indigenous, queered) and governing societal understandings (Walter & Andersen, 2013).

While the anarchic principles on which we build this methodological frame do not presuppose a particular ontology (or epistemology), they do foreground particular ontological (and epistemological) directions, substantively narrowing the array of ontologies (and epistemologies) we might consider reasonable. Phrased in the most concise possible terms, the ontological stance of an anarchist researcher is one of profound humility: that humans and nonhumans are complex, and that we are complex in ways that resist meaningful simplification (Smedslund, 2009; Weaver & Snaza, 2017). Efforts to simplify the human are, by definition, dehumanizing, and would thus conflict with our anarchic axiological foundation.

To efficiently convey a sense of the magnitude of this complexity within the confines of this manuscript, here we will surface four ontological characteristics of the human (note that the complexity amplifies when one extends beyond sole consideration of the human) and observe how they constrain one of the oft-touted goals of educational research—namely, the goal of surfacing absolute or general principles related to given measures based on the noticing of empirical regularity (Goddard & Wierzbicka, 1994; Smedslund, 2004; Wierzbicka, 1996). These principles have been associated with the ongoing disconnect between educational research and educational practice; they are principles that practitioners must take for granted, while research commonly tries to evade or methodologically exclude them (Smedslund, 2009; Weaver & Snaza, 2017).

Principle 1: Openness. The openness of the human means that, in principle, every single psychological/behavioral measure, and hence every composite measure, is open to an indefinite number of possible influences, depending on how the situation is varied and how the task is understood.

Principle 2: Irreversibility. People are intentional (e.g. trying to pursue good outcomes or avoid bad outcomes), and do not completely unlearn or forget. Thus, observed regularities are conditional upon stable perception of outcomes, rendering absolute or general principles impossible. A valid general principle would entail a limit to intentionality, since it could not be modified by changing outcomes.

Principle 3: Shared Meaning Systems. People are forever part and parcel to innumerable overlapping shared meaning systems—the cultures of family, friends, workplaces, countries, regions, religions, ethnicities, and so forth. Regularities surfaced in research commonly reproduce what we already know (explicitly or tacitly) by virtue of their contingency on shared meaning systems.

Principle 4: Uniqueness. Chance plays a prodigious role in all aspects of our lived experiences, both inward and outward (e.g. Bandura, 1982). Serendipity and misfortune shape people in surreptitious ways, imposing a rigid barrier betwixt the ways the human is and the possibility of developing absolute or general principles.

Epistemology

Epistemology, the philosophy of knowledge and knowing, is central to the work of researchers ostensibly (per our positivist-shaped void) tasked with knowledge production. Whereas traditional Western philosophy constructed epistemology as outside of or prior to culture, the true span of epistemic consideration is wider: considerations of the (oft unwritten) rules of what counts as knowledge, who can be considered knowledgeable, and what knowledges are valorized or marginalized are key to epistemic consideration (Walter & Andersen, 2013).

Feyerabend (2010) argued for and outlinesan anarchistic theory of knowledge (this was the subtitle of the first edition). Like us, Feyerabend’s motivations in writing that text were built upon an axiological foundation:

Anger at the wanton destruction of cultural achievements from which we all could have learned, at the conceited assurance with which some intellectuals interfere with the lives of people, and contempt for the treacly phrases they use to embellish their misdeeds. (p. 265)

The overarching thesis statement of Feyerabend’s text is simply stated at the outset:

Science is an essentially anarchic enterprise: theoretical anarchism is more humanitarian and more likely to encourage progress than its law-and-order alternatives… history generally, and the history of revolution in particular, is always richer in content, more varied, more many-sided, more lively and subtle than even the best historian and the best methodologist can imagine. (p. 1)

In essence, just as we describe the anarchist researcher as ontologically humble, Feyerabend describes an anarchist researcher as epistemologically humble. Indeed, we note that ontological humility almost demands epistemological humility, as we illustrated above in relating ontological principles to barriers to one of the commonly touted epistemic goals of hegemonic science.

To the anarchist researcher, anything goes; or rather, you are always more free than you realize you are. An anarchist researcher might use virtually any epistemic method to make sense of or shape the world, even methods that seem contrary to their perspective, as when anti-rationalist Feyerabend regularly made rationalist arguments to discomfit his rationalist opponents and friends (e.g. Lakatos). Viewing science (in our broad conceptualization) as a pedagogic project, one wherein we are forever learning with and from others, and imagining hegemonic science as institutionalized schooling, we find this reflection rooted in Freire and Rancière to be particularly meaningful:

The unschooled world is only feared by those who have been thoroughly schooled. The emancipated world has no enemies among the truant. None among children and none among artists. None among those who would take equality as a point of departure. (Bingham & Biesta, 2010, p. 157).

Social Position

Our social position comprises much of who we are socially, economically, culturally, and racially. Social position is not just about the individual or individual choices—class, culture, race, gender, sexuality, (dis)ability/neurodiver-

gence, and so forth deeply shape worldview, not least because so much is taken for granted. Social position is thus a verb rather than a noun. As researchers and as people, we do, live, and embody a social position (Walter & Andersen, 2013).

Obviously we can make no particular observations about the specific social positioning of you, dear reader. However, the anarchist researcher does adopt a particular relationship with social positioning. In short, the anarchist researcher takes social positioning seriously, and may use it as a guide for noticing blind spots or disproportionate emotional/physical labor demands. Additionally, anarchist positioning is worthy of note in-of-itself, for it necessarily runs deep (per our axiological foundation), contrary to the disparate professional positionings that others may tend to write off as “just part of the job.”

Anarchists take social positioning seriously (though people who don’t have been known to attempt to co-opt the title). Per our axiological foundation, anarchists oppose unjustified, coercive hierarchies, including those of race, gender/sexuality, class, dis/ability, religion, nationality, and so forth. None of these hierarchies are individual monoliths—they silently embrace and dance a dance of violence, holding each other so close that their boundaries blur and disappear. Thus, anarchists are also deeply invested in intersectionality, variously in terms of: noticing and responding to the complex ways various intersections of identity shape lived experiences, accounting for constructed invisibility and cultural obfuscation of the multiply marginalized, and working to build solidarity across those of disparate backgrounds suffering at the hands of the same deathly waltz.

Furthermore, there are additional aspects of social positioning and hierarchy that are relevant to (mathematics) education researchers in particular. An anarchist researcher recognizes that they bear unique experience, knowledges, or tools that another might not have immediate access to, but will nonetheless express extreme skepticism of the many coercive and unjustified aspects of the hierarchy which places researchers epistemically above others as knowers and learners. Relatedly, an anarchist researcher is deeply skeptical of the epistemic and social hierarchy that perceives established scholars as superior to emerging scholars, as well as the epistemic and social hierarchy that perceives “teachers” as superior to “students.” An anarchist researcher further opposes hierarchies of discipline, such as the Romance of Mathematics (Lakoff & Núñez, 2000), the still commonplace mythology that contemporary disciplinary mathematics is epistemically superior to other disciplines or disciplinary perspectives.

As one final note that distinguishes this methodological approach from those typically constructed as existing at the center rather than the margins (work constructed on the margins, such as indigenous methodologies, is more likely to intentionally share this characteristic), anarchism as methodology is not limited to professional situations—it is a lifestyle. To borrow a metaphor from educational philosopher Lynn Fendler, imagine yourself as a chef, passionately dedicated to your craft. Can you dissociate the qualities of your ingredients from the qualities of the food they are used to create? By the same token, in our work as researchers, is it really possible to dissociate the qualities of the researcher from the qualities of the research they produce? To create the most delicious dish, we use ingredients that carry the qualities we wish to be present in that dish. To create the most ethical research, we must use ingredients that carry the axiological qualities we wish to be present in the research (Vellanki & Fendler, 2018).

Anarchism and Research: Tracing The Possibility Space of Anarchist Method

In [critically engaging with one’s worldview], the frantic search that novice (and even seasoned) researchers experience in selecting theoretical frameworks and methodological approaches more times than not becomes self-evident and trivial. (Stinson, 2020, p. 13)

Having sketched the outlines of the worldview(s) associated with anarchism above, in this section we use that foundation to infer elements of the possibility space of anarchist research method. This space is vast, even as it excludes swathes of normative research methods (for example, psychometrics in its normative context—that is, the context of the worldviews and purposes that commonly underlay it—fall in steep conflict with an anarchist worldview). Thus, our goal is to be illustrative rather than exhaustive. In particular, we draw attention to three categories of method that have proved meaningful in our own work: collaborative action and design research, discourse-shaping and radicalizing research, and work that stands as iconoclasm of the oppressor within.

Collaborative action and design research

Despite ill-informed representations perpetuated by the media and other sources, the most likely places you might find anarchists in your community are at your local community garden, baby pantry, workers union, or co-op (we, the authors, have participated in each of these). These are loci of cooperation and mutual aid, places where people have noticed their community has a need that they can help to fill. As researchers with specialized knowledge(s) that can be leveraged for the benefit of our communities, one notable analogue to these aforementioned spaces in research is collaborative action and design research. Action and design research represent

an orientation to knowledge creation that arises in a context of practice and requires researchers to work with practitioners [and other stakeholders]... its purpose is not primarily or solely to understand social arrangements, but also to effect desired change as a path to generating knowledge and empowering stakeholders. (Huang, 2010, p. 93)

Note that whereas more normative research might prioritize knowledge as a means towards change and empowerment, Huang instead describes pursuing desired change as a means to knowledge and empowerment. Along with relating to our axiological foundation, this also ties into the ontological and epistemological humility we referenced previously. In short, the goal of collaborative action and design research is to support communities, as for example through the collaborative development of “new theories, artifacts, and practices that can be generalized to other schools” (Barab, 2014, p. 151) or areas of praxis.

Discourse-shaping

Every publication, presentation, seminar, lesson, and conversation is necessarily a political act. Interaction either reifies or perturbs boundaries and beliefs, forever modifying the ideological and material translucence we occupy (Dubbs, 2021). Whenever we converse, the question is never “should I be political or not,” for we are necessarily political in manners either hidebound or progressive. Instead, the question is, “in what ways should I be political?” or “in what ways should I shape this discourse?” Conscious of this, the anarchist researcher seeks to shape discourse in ways that advance our ethical goals of cooperation, mutual aid, and freedom from unjustified, coercive hierarchy. We might, for example, publish critical works in typically acritical spaces (Bowers & Küchle, 2020) in an effort to normalize critical perspectives therein, thus paving the way for further change or revolution. Discourse shaping is always a component of the work of any researcher (consciously or not), but for the anarchist researcher it can also serve as a goal in-of-itself, whether that means mobilizing/radicalizing potential future researcher-activists or simply offering a moment of critical introspection to an audience not often engaged in such.

Iconoclasm of the oppressor within

White supremecy, cis-heterosexual male supremecy, abled/neurotypical supremecy, capital supremecy… each of these (and other) oppressive paradigms/hierarchies surround us and can act through us.

The true focus of revolutionary change is never merely the oppressive situations which we seek to escape, but that piece of the oppressor which is planted deep within each of us, and which knows only the oppressors’ tactics, the oppressors’ relationships (Lorde, 2007, p. 118)

The anarchist researcher has an ethical responsibility to always consider the ways oppressive systems may act through us, below the level of consciousness, notably (but not solely) along continua wherein our identity and/or positioning might place us among oppressors. For example, a white researcher might be aware that whiteness is acting through a system in which they participate, such as mathematics doctoral coursework. It is common for disproportionate burden to be placed on BI-POC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) to surface white supremacy (with analogues applicable to each other system of oppression), so the white researcher might dedicate careful time, energy, and attention to analysing and thinking through how whiteness is acting in those spaces, then share what they surface with other researchers subject to similar positional blindness (e.g. Bowers, 2019). With this sort of persistent, critical reflection, we seek to free ourselves from such hierarchies of domination—by sharing this work with others, we engage in yet another type of cooperation and mutual aid. While we emphasize the ways positional blindnesses and disproportionate systemic expectations might make this work more important along the lines of our oppressive identities/positionings, we do wish to mention that such supremacies are commonly internalized along the lines of our marginalized identities as well, as when internalized neurotypical supremacy or cis-heterosexual male supremacy rears its ugly head in the work, thought, or action of this neurodivergent (autistic, ADHD), genderqueer author.

Conclusion

Anarchism is present in a significant portion of modern equity and justice research in mathematics education (Bowers & Lawler, 2020). Explicit identification of and attention to anarchist methodology provides researcher and reader the opportunity to more explicitly identify the manner in which knowledge production operates in harmony (or conflict) with stated aims of a just an equitable society: cooperation; mutual aid; and freedom from unjustified, coercive hierarchy. Phrased differently, building methodology from the foundation of anarchism allows for a cohesion of theory and praxis that would be beneficial in any work, but which carries particular weight when one’s goals are emancipatory or anti-oppressive.

Critical theory is necessarily an inadequate force of change when not accompanied by critical praxis. The additional step of critical praxis has presented a hurdle to many, a fact at once shocking and wholly unsurprising—unsurprising, because critical and social justice work can’t be built on a foundation of oppression such as that symbolically and materially reified in the norms and methods of much mathematics education research, but shocking, because a new reality lies just out of sight over the horizon. We hope this glimpse of one such reality, one such critical praxis developed through a cohesion of theory and practice, might offer a glimpse over such a horizon. While throwing off the reigns of oppression might seem at times an insurmountable challenge, we look forward, in solidarity, to basking under the warmth of new suns.

Acknowledgements

Much of this text was developed as an early component of the first author’s dissertation (Bowers, 2021) and subsequently shared at the 11th international meeting of Mathematics Education and Society (Bowers & Lawler, 2021).Itwill receive expansion in future publication.

References

Bakunin, M. (1971). Bakunin on anarchy (S. Dolgoff, Ed. & Trans.). Vintage Books.

Bakunin, M. (1871). What is authority? Found at https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/bakunin/works/various/authrty.htm

Bandura, A. (1982). The psychology of chance encounters and life paths. American Psychologist, 37, 747–755.

Barab, S. (2014). Design-based research: A methodological toolkit for engineering change. In R. K. Sawyer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (pp. 151–169). Cambridge University Press.

Bingham, C. & Biesta, G. J. J. (2010). Jacques Rancière: Education, truth, emancipation. Continuum International Publishing Group.

Bowers, D. M. (2019). Critical analysis of whiteness in a mathematics education proseminar syllabus. In J. Subramanian (Ed.), Proceedings of the 10th international Mathematics Education and Society Conference (pp. 284–293). Hyderabad, India.

Bowers, D. M. (2021). Anarchist mathematics education: Ethic, motivation, and praxis (Publication # 18446) [Doctoral dissertation, Michigan State University]. Proquest.

Bowers, D. M. & Küchle, V. A. B. (2020). Mathematical proof and genre theory. The Mathematical Intelligencer, 42(2), 48–55.

Bowers, D. M., & Lawler, B. R. (2021). Anarchism as a methodological foundation in mathematics education: A portrait of resistance. In D. Kollosche (Ed.), Exploring new ways to connect: Proceedings of the Eleventh International Mathematics Education and Society Conference (Vol. 1, pp. 321–330). Tredition. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5393560.

Bowers, D. M. & Lawler, B. R. (2020). Reconciling tensions in equity discourse through an anti-hierarchical (anarchist) theory of action. Proceedings of the 42nd annual meeting of the North American Chapter of the International Group for Psychology in Mathematics Education (pp. 518–524). Mazatlán, Mexico.

Cabral, T. C. B., & Baldino, R. R. (2019) The social turn and its big enemy: A leap forward. Philosophy of Mathematics Education Journal, 35.

Dubbs, C. H. (2021). Mathematics education atlas: Mapping the field of mathematics education research. Crave Press.

Feyerabend, P. (2010). Against method (4th edition). Verso.

Goddard, C., & Wierzbicka, A. (Eds.). (1994). Semantics and lexical universals. John Benjamins.

Gutiérrez, R. (2008). A “gap-gazing” fetish in mathematics education? Problematizing research on the achievement gap. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 39(4), 357–364.

Huang, H. B. (2010). What is good action research?: Why the resurgent interest? Action Research, 8(1), 93–109

Lakoff, G. & Núñez, R. E. (2000). Where mathematics comes from: How the embodied mind brings mathematics into being. Basic Books.

Lorde, A. (2007). Sister outsider: Essays and speeches. Crossing Press.

Martin, D. B. (2019). Equity, inclusion, and antiblackness in mathematics education. Race Ethnicity and Education, 22(4), 459–478.

Moore, A. S. (2020). Queer identity and theory intersections in mathematics education: A theoretical literature review. Mathematics Education Research Journal, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13394-020-00354-7

Smedslund, J. (2004). Dialogues about a new psychology. Taos Institute.

Smedslund, J. (2009). The mismatch between current research methods and the nature of psychological phenomena: What researchers must learn from practitioners. Theory & Psychology, 19(6), 778–794.

Stinson, D. (2020). Scholars before researchers: Philosophical considerations in the preparation of mathematics education researchers. Philosophy of Mathematics Education Journal, 36.

Suissa, J. (2010). Anarchism and education: A philosophical perspective. PM Press.

Vellanki, V. & Fendler, L. (2018). Methodology as lifestyle choice [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rfy_y1E8EoY&

Walter, M. & Andersen, C. (2013). Indigenous statistics: A quantitative research methodology. Taylor & Francis Group.

Weaver, J. A., & Snaza, N. (2017). Against methodocentrism in educational research. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 49(11), 1055–1065.

Wheatley, M. J. (2005). Finding our way: Leadership for an uncertain time. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Wierzbicka, A. (1996). Semantics: Primes and universals. Oxford University Press.

Williams, D. (2012). From top to bottom, a thoroughly stratified world: An anarchist view of methodology and domination. Race, Gender, & Class, 19(3), 9–34.