Dan Fischer

Stop Cop Planet, Save the Surreal World

March 5, 2023: Approaching a construction site for Cop City, officially known as the “Atlanta Public Safety Training Center,” roughly 300 masked forest defenders cut through the fencing and chanted with conviction, “We are unstoppable, another world is possible.” Throwing rocks and fireworks, they caused cops to retreat. The crowd burned down several construction vehicles and a trailer, undoing about a month’s worth of work and causing at least $150,000 in damages.[1]

March 8: Reversing their ancestors’ route on the Trail of Tears, an official Muscogee delegation returned to Atlanta’s Weelaunee Forest. They announced to the city’s authorities, “You must immediately vacate Muscogee homelands and cease violence and policing of Indigenous and Black people.”

It can feel surreal watching such inversions of the common-sense social reality where police chase protesters and settler elites evict natives.[2] Building on the communal and sometimes jubilant militancy of the Standing Rock and George Floyd uprisings, the Stop Cop City movement effectively declares: to hell with your thin blue line, your economy, your authorities. Such authorities include Atlanta’s Black mayor Andre Dickens and his Democratic administration, as well as the leaderships of the city’s historically Black colleges. Referencing his school’s funding of Cop City, a student denounced Morehouse’s complicity in “a system that does not serve Black people.”[3]

Among the crowds occupying city streets and among the Weelaunee Forest’s tents and treehouses, signs declare commitments to police abolition, decolonization, anti-fascism, radical ecology, and total liberation. “Stop the metaverse. Save the real world,” declares a banner hanging between two pines. The message went viral, ironically, and why not? What could be more worth defending than an urban forest? What could be more worth stopping than the metaverse, that comprehensive virtual reality concocted by profit-hungry, surveillance-friendly social media executives?

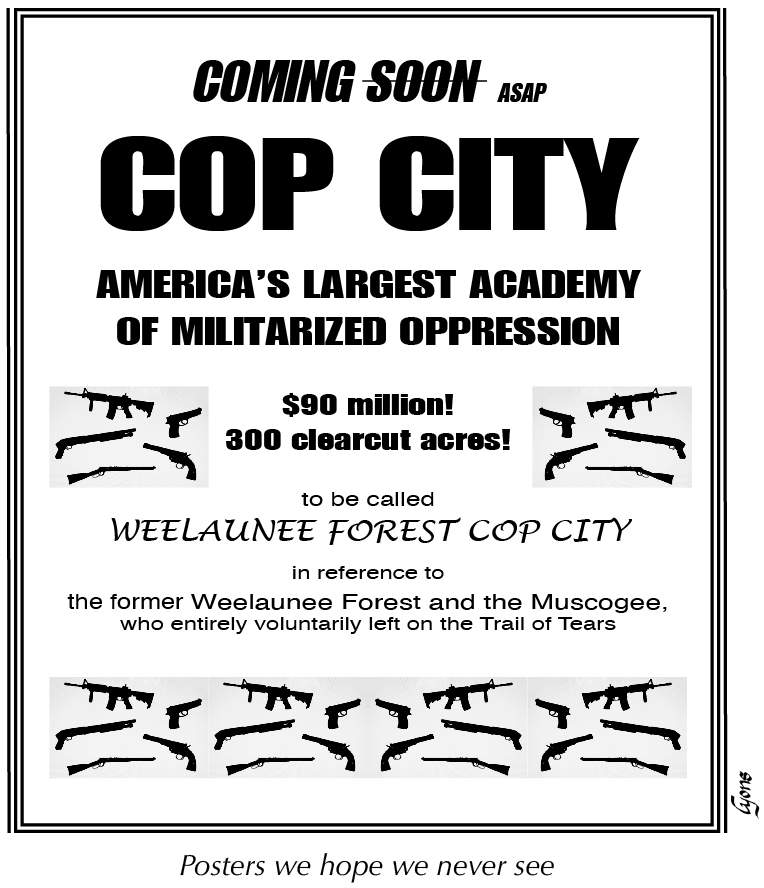

However, for those caught in the rhythms of capitalist time, centered around working or surviving among the unemployed “industrial reserve army,”[4] we often experience the “real world” as precisely the social reality responsible for threatening Atlanta’s forest. Hollywood Dystopia is Shadowbox Studios’ murky plan to destroy more of the forest, apparently for a massive soundstage complex. Cop City, a $90 million police compound, would be the country’s largest academy of militarized repression. It’s being built despite 70 percent of public comments in 2021 expressing opposition, despite the immediately adjacent neighborhoods across city borders not being given a say. Cop Planet is the world of transnational capital’s “mass social control, repression and warfare,”[5] where—for example—Georgia’s cops receive training from hypermilitarized Israeli police.[6] It’s the brutal reality where U.S. police kill people every single day, where Atlanta cops murdered Rayshard Brooks in 2020, and where Georgia troopers murdered Tortuguita, a Venezuelan gender-nonbinary anarchist, in the forest this January.

An anarchist newsletter reports that the slogan “Against Cop City and its World” can be heard to “echo throughout Atlanta and across Turtle Island.”[7] Attacks on Cop City’s contractors and financiers—such as Nationwide, Brasfield and Gorrie, Atlas, Bank of America, and Wells Fargo—have been accompanied by communiques that express opposition not only to Cop City but also to “the world that needs it.” Forest defenders insist their struggle is far more than merely a local campaign or protest movement, but a flashpoint for dismantling social authority more broadly, even globally. As more people join efforts to protect the forest, moderate elements deliver a watered-down message. Still, the commitments to decentralization and autonomy remain at the strategic core and thwart corporate or liberal attempts at co-optation. After the March 5th crowd sabotaged a month’s work of construction, the police complained, “This is not a protest. This wasn’t about a public safety training center. This was about anarchy.” Quite a few of the forest defenders would likely agree, actually.

Bringing together movements for radical ecology, decolonization, and police abolition, the Stop Cop City struggle connects these issues to powerful working-class striving for a world beyond alienation. No wonder the feds are so intent on spreading bogus “terrorism” charges. If humanity is going to reverse runaway global burning and ecological collapse, then we’ll need some help from the trees, the wild, the strange and dreamlike. Stop Cop Planet, save the surreal world!

Black Power, Land Back

As the Weelaunee Forest continues to self-rewild, volunteer researchers have been making sure that local history doesn’t get lost under the vibrant canopies. The region’s circular council houses built in 500 CE, able to hold hundreds of people, suggest that the Muscogees’ consensus-based decision-making councils are among the world’s oldest institutions of self-governance. Oral histories suggest that up until Europeans arrived, the region’s societies, including the Muscogees, were gender egalitarian.[8] After Indian Removal ended millennia of indigenous stewardship, the land became a slave plantation, and then a prison camp from roughly 1920 to the 1980s . Of the many inmates held at the “Old Atlanta Prison Farm,” one was Kwame Ture, then known as Stokely Carmichael. He’d popularized the slogan “Black Power” during his leadership in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. In 1967, police arrested Ture and two associates under a loitering law, for failing to obey an officer’s orders to “move on.”

In Atlanta, heirs to Ture’s Black Power philosophy explicitly emphasize ecology. For example, Community Movement Builders (CMB)’s main programs include defending the Weelaunee Forest and running the Welch Community Garden. CMB concludes its 10-point platform with “Sustainability”:

Due to the endless pursuit of growth and profit-seeking, capitalist development has destroyed the environment, created destructive climate change, and engineered global warming. These issues directly and disproportionately impact Black/Afrikan people globally, causing disruptions to our food sources and environmental conditions that destroy our communities. Therefore, we demand food sustainability systems and new community development practices that are not only safe but also enhance the quality of all life, the environment, and the planet.[9]

As community organizer Jackie Echols explained to Daily Show comedian Roy Wood Jr., the construction of Cop City in a predominantly Black neighborhood follows a pattern of disproportionate impacts known as environmental racism. “The folks that are affected are Black, and powerless,” she explained, “That’s the definition of environmental racism.”[10] In fact, decades of organizing and scholarship on environmental racism have long pointed to a potential merger of Black power and deep-green liberation. Still, it’s hard to think of an example where there’s been such a thorough and effective alliance between the Black Power movement, the Indigenous struggles for “Land Back,” and the predominantly white movement for a deep-green anarchism.

Black educators of the Weelaunee Coalition, which formed in January 2022, organize bike rides and celebrations in the forest, explicitly in solidarity with the tree-sitters and blockaders who broadly come from milieus connected to the Earth First! (EF!) tradition. These are the forest campers that Wood called “the Georgia Ewoks” and the authorities smear as “outside agitators.” A majority are white, about half are queer, and almost all of them are in their twenties and early thirties. As Atlanta locals and tree-hugging dropouts rave together all night in the forest, DJs blast varieties of rap, techno, punk, and noise pop.

While the biggest stars out of Atlanta’s rap scene haven’t spoken out about Cop City, smaller acts have vigorously supported the resistance and even played free shows in the forest. Their songs often contain radically green messages, such as when Raury raps about the state’s central role in destroying “this burning Earth”: “I got news for you man/ Your so-called constitution/ Will advocate the mass pollution.” There’s recognition, in other words, that the status-quo institutions, from legislatures to courts, are designed to serve the globally growing and hence unsustainable economy.[11] A policed planet is necessarily poisoned and plundered, an endangered Earth, a Gaia in the gallows.

Perhaps the most important musical events have been the stomp dance ceremonies run by returning Muscogee folks. Abundia Alvarado, an organizer with Atlanta’s queer, Indigenous and Latin group called Mariposas Rebeldes, explained:

I went to Oklahoma and reached out to a Mekko (leader) of one of the ceremonial grounds. I informed the Mekko of what was happening and opened an invitation for him and his grounds members to come. They agreed to visit Weelaunee and to perform a stomp dance exhibit there, so we quickly started to raise funds and hosted them during National Day of Mourning (so-called Thanksgiving) <verbatim>[</verbatim]2021] for an historic Stomp Dance. That dance was very well attended, the most well attended event of the Save Weelaunee movement to date. It was a beautiful night with clear and crisp skies, the Mekko gave a very powerful speech about Muscogee stewardship of the homelands and a blessing for the people fighting for the forest.[12]

Alvarado explains that the forest defenders have been in dialogue with Muscogee people, “discussing what Land Back and rematriation mean to them.” From such conversations, some Atlanta residents have sought to learn from and with Indigenous communities about how to practice “radical stewardship” and how to interact with the Earth as a “sacred web of abundance.” In a recent zine, the Weelaunee Web Collective has elaborated:

Radical stewardship is fundamentally a spiritual way of being. When we allow ourselves to fall deeper into the Sacred Web of Abundance [SWoA] around us, we see how each moment of connection with the earth is a ceremony: we harvest pecans and sing the glory of the pecan tree, we bury the dead bird on the side of the road and mourn a life taken too soon, we speak with the chanterelles growing along the river and ask how we might be nourished by their bodies, we see the cycles of life and death happen again and again around us in seasons and know that we too must live now and will someday die, our body weaving itself back to SWoA—but while we breathe into this world, each connection weaves us tighter into the interconnected world, into abundance.[13]

Such reconnection with the Earth involves a fundamental transformation of everyday life and a striving for freedom from alienated labor. In fact, one of Stop Cop City’s most important contributions has been to bring a refusal of work to the forefront of anti-policing struggles. To truly understand the role of the police, it’s helpful to turn to loitering, the crime that Ture was charged with back in 1967 before he’d go on to become Honorary Prime Minister of the Black Panther Party.

The rise of modern policing, in the fifteenth century, propelled the nascent capitalist system’s enclosure of common resources and thus the imposition of wage labor and other types of alienating work such as intensified housework, colonial exploitation and enslavement.[14] “The founding principle of police,” notes social theorist Mark Neocleous, “is the idea that every citizen-subject ought to work; or, more explicitly, that every citizen-subject ought to be put to work.” In this context, “the greatest ‘crime’ was thought to be idleness itself; ‘disorderly’ is more often than not a euphemism for ‘workless.’”[15] The modern police, in other words, serve a society arranged around the imposition of work.

In Praise of Loitering

Key to Stop Cop City’s anarchic praxis, there’s an effort to build and experience, as much as practicable, communal life beyond compulsory work. A forest defender going by Hummingbird has described the forest campsites as “an anti-workspace” where, without a manager in sight, “you do what you’re called to do and you try to figure out how to help others feel like they have the capacity to help in the ways [that] feel good to them.” Tortuguita used to say, “I’m in the IWW [Industrial Workers of the World]! I think that nobody should work!”[16]

This defiantly idle spirit can be seen in the following recommendations by the Fayer Collective of Jewish anarchists in Atlanta:

Quit your job. Cut holes in fences. Forgive everyone everything—except the agents of “progress,” who squeeze the world into a grid and don’t care who or what they crush. Befriend your neighbors: human, plant, and animal. Trade the mechanical time of clocks for the living time of the sun, the moon, the seasons. Sabotage all that sabotages your life. Block the roads. Destroy work, by flood or by fire. Steal everything that should be free, which is to say: everything. Don’t get caught. Learn what you desire and seize it, even if at first the pleasure frightens you. Breathe deeply, love frontally, attack anything that tries to deny you that power. Start now.[17]

Another forest defender describes quitting their job and sojourning to Atlanta. “It seems simple. Work is hell. The forest is beautiful. The goal of protecting what sustains us and destroying what destroys us is the most important thing.”[18]

Workers’ dislike of work isn’t anything new, and it’s often been a major theme in popular media. Atlanta-based Linqua Franqa mockingly raps, in character as a financial elite: “Blatantly bury you under the interest, wasting your life indentured, / 8 to 5 and then some, /Just to pad our pockets with the payments we invented, /Breaking your resistance isn’t an accident it’s exactly as it’s intended.”

Still, antiwork themes have been a taboo subject in many leftist spaces. Almost any U.S. union, nonprofit or political party is likely to demand a near-term expansion of full-time employment rather than a reduction. It’s true that at the rank-and-file level, there has often been some interest in the potential for economic degrowth to allow a much shorter workweek.[19] However, a glance at the words of the leaders and official organizational statements reveals that even environmentalist nonprofits have centered productivist demands for a growth-based Green New Deal and full-time job creation.

For antiwork strategies to become more self-sustaining and widespread, communities need to build the infrastructure to make quitting, striking, and grassroots reconstructing accessible to folks who aren’t, say, twenty-something, single, and childless. The good news is that, even at this stage in unfolding eco-disaster, we still live on a planet of abundance. There’s more than enough food grown to feed humanity, there’s sufficient solar and wind technologies to power a degrowing society, and there’d be plenty of land if people substituted beans for beef and so on. When imagining a post-capitalist future amidst natural abundance, the Weelaunee Web Collective points to Atlanta’s gift-economy festival organized by the Mariposas:

Capitalism has brainwashed us into believing in the myth of scarcity. But we already live in abundance. The Dandelion Fest demonstrated this. Dozens of people came together to share food, medicine, plants, and clothes, plus their talents on the open mic. It felt like many other queer outdoor markets in Atlanta—except you didn’t leave spending $50. Soon, people were asking us when we were going to put on the next festival—it had become a staple of Atlanta’s DIY scene.

Tortugutia’s union, the IWW, is one of the few that has taken antiwork ideas quite seriously. Members in the 1960s and 1970s turned to the surrealist tradition of work refusal exemplified by the Paris Surrealist Group’s 1925 declaration of “war on work” (guerre au travail).[20] Part of the surrealists’ appeal entailed their ability to untangle and challenge the work ethic, common sense, and mental conservatism generally.

Unshackling the Mind

Unlike Hollywood’s or the Metaverse’s “spectacular” or “hyperreal” mergers of reality and image, a surreal approach confronts the psychological bases of colonialism and oppression, from deep alienations and inferiority and superiority complexes, to internalized authoritarianisms and mechanistic cosmovisions. Martinique surrealist Suzanne Césaire emphasized that at the surrealist movement’s dawn, “the most urgent task was to free the mind from the shackles of absurd logic and so-called Western reason.”[21] The same mental shackles today exist as an undialectical logic of a common sense which tells us: Even as the climate changes, basic social structures must stay the same; even as the Earth burns, social relations must remain icy cold.

In the Daily Show segment, Wood incredulously asked the forest’s blockaders, “Y’all get massages? You do yoga, meditate, stretch and deal with your inner — like therapy.” This sort of collective self-care can be vital for those engaged in a high-stakes struggle. Being around trees can boost mental health as well, as can the time off the screen and engaged in face-to-face community building. The most important therapy may be the engagement in direct action itself, as a way of breaking the spell of the ordinary and supposedly inevitable. Césaire’s description of surrealist praxis, as “living, intensely, magnificently,” could describe the intense lifestyle of the forest defenders. This is the mindset that a Weelaunee blockader expressed:

This resistance is not only absolutely necessary, but it’s a lot of fun, and it frequently feels really good to resist something that is just so ontologically evil. No compromise in defense of Mother Earth, no compromise in defense of our lives, no compromise in defense of our freedom or autonomy.[22]

Césaire claimed that pursuit of the surreal “will aid in liberating people by illuminating the blind myths that have led them to this point.” These myths take root in a system of policing much broader than people dressed in blue. The word “policie” emerged in fifteenth-century France, and the interchangeability of “police” and “policy” reflected how today’s “hard cops” partner with the “soft cops” populating the welfare state’s bureaucracies. Even such supposedly noble professions as social workers and teachers exist at the forefront of soft policing, frequently involved in surveillance, standardization, regulation, reporting.[23] As the CMB’s platform explains, “Currently, our public school system serves as a propaganda machine for the capitalist, imperialist state and trains our children to be exploited worker-participants within these systems, rather than developing our youth into self-directed thinkers with autonomy over their future.”[24]

It’s heartening, therefore, to see some of Atlanta’s teachers refusing this prescribed role as soft cops and instead bringing kids into the forest to learn from the anarchists and abolitionists. Highlander School’s founder Rukia Rogers explains, “We went to a Muscogee stomp [dance ceremony]. We planted seeds, took tours with tree defenders—they showed how they got into the tree houses. Then we told the students there was a plan to destroy it.”

Terror and Dreams

Rogers reports being devastated to hear of the cops’ murder of Manuel Esteban Paez Terán, who went by Tortuguita (“Little Turtle”) in the forest: “I remember Manuel leaning into me in this wellness tent in the woods. I was in a bad place. They were the most beautiful soul. Totally chill.”[25]

Crackdowns had taken off in December, with police and SWAT teams raiding the forest to make arrests and distribute felony charges of domestic terrorism, with possible sentences of 35 years. By early May, forty-two people had been given these extreme and clearly unwarranted charges. In one case, the so-called terrorists’ offense was merely putting flyers in mailboxes in the neighborhood of a cop involved in killing Tortuguita on January 18.

That morning, Georgia State police raided the forest again and, in the span of eleven seconds, pierced Tortuguita with 57 bullets. Cops fired so heavily that they hit one of their own in the leg. “You fucked your own officer up,” an officer can be heard saying in the Atlanta police footage of the shooting’s aftermath. The police narrative, that Terán fired a gun at them first, is unlikely to be true. Tortuguita apparently possessed a gun but didn’t fetishize its use. They’d even recently told journalist David Peisner:

We get a lot of support from people who live here, and that’s important because we win through nonviolence. We’re not going to beat them at violence. But we can beat them in public opinion, in the courts even.[26]

Had Tortuguita fired, they’d have merely been acting in self-defense. The clear aggressors are the officers who invaded the cherished forest in order to attack and arrest a bunch of youths and dropouts camping in the woods.[27] All on stolen Muscogee land, no less. Historically, guns have provided vulnerable communities an important means of self-defense.[28]

However, guns’ presence in any struggle raises some quandaries. For one thing, civilians can be at least as prone to misusing guns as are cops. When police murdered Rayshard Brooks in 2020, neighbors took over the site and ran it as a cop-free zone for twenty-three days. Then on July 4, a demonstrator shot at a car and killed eight-year-old passenger Secoriea Turner. Yes, it should be acknowledged that, prior to Turner’s death, the presence of guns was key to keeping the cops away. At the same time, guns also kept away many potential participants, including many Black, brown, and white parents who didn’t want to expose their kids to danger.[29]

For that matter, even the use of fireworks and Molotov cocktails introduces issues deserving careful deliberation. However inspiring the March 5th sabotage may have been, could there have been some truth to fire officials’ warning that “flames could have spread into forest fires threatening the neighboring community”? In any case, it appeared that way to some potential sympathizers. Eco-anarchists might therefore wish to publicize, in their communiqués and report-backs, whatever fire-safety training and precautions they are employing. It’s worth stressing that decades of U.S. eco-anarchist arson haven’t physically harmed any humans or forests so far.[30]

Lost in some of the jargony debates, for example, between proponents of “composition” and “decomposition” and over “memetic resistance,” there has often been too little discussion of community. It’ll take popular communal structures of de-escalation, rehabilitation and reconciliation to confront the violence that’s committed by people in or out of uniform. As the abolitionist slogan goes, “Strong communities make police obsolete.” Atlanta-born reverend Martin Luther King, a one-time gun owner, also dreamt of beloved community overcoming “the unspeakable horrors of police brutality.” Already there are alternatives to 911, like Atlanta’s Policing Alternatives and Diversion Initiative which offers access to support, housing, and other resources.[31] What if the spread of liberated zones transformed Atlanta into a Cop-Free City where neighbors, armed or not, could keep each other safe?

The End of Their World as They Know It

When imagining strong community building, we could also look at CMB’s strategy of establishing “liberated zones” where residents “are in near-complete control over their political and socio-economic destinies because they control the institutions.”[32] In various ways, their approach reflects the IWW’s commitment to forming the “new society within the shell of the old” as well as the various communes and cooperatives affiliated with North America’s Symbiosis network. As such projects spread, they could offer food, shelter, and care to people who want to leave their jobs and explore communal and insurgent forms of living.

Perhaps teenage students will coordinate a School Strike to Defend the Forest. Maybe teachers and staff will join them, and parents, siblings, aunts, uncles, and neighbors as well, until we can speak of a mass strike. Driven by their dislike of work, workers might look forward to learning to survive collectively off the clock. Insofar as they’re willing to return, they may insist on self-management, shorter hours, and greener methods.

A calendar might be distributed where one could find multiple Dandelion Fest-type events every day. People could swap skills like how to refurbish an old computer, grow food veganically, or use a 3D printer. Community workshops might pop up where anyone can go and manufacture stuff out of recycled and foraged materials. The online Dual Power map run by Black Socialists in America could be almost overrun with projects on every single block. Community theater productions and indie film screenings might provide refreshing alternatives to the copaganda and dystopian futures envisioned by blockbuster studios like Shadowbox.

If Atlanta is sometimes called a “city in the forest,” that’s nothing compared to how it might look when church and mosque groups start planting trees in the middle of busy roads, and fill car tires with soil and seedlings. Freed for a time from capitalism’s rhythms of work and school, residents might explore and party in the Weelaunee Forest at all hours.

During the daytime, a council of Muscogee delegates might convene a network of study groups to produce a seven-generations plan for protecting and restoring the forest and the broader web of abundance. Various residents could look at how Indigenous and revolutionary societies have managed to confront violence without establishing a specialized police force.

In 2021, authorities predicted that Cop City would be built in the next two years. A couple years later, completion is nowhere in sight. Contractor Reeves-Young has dropped out. The movement has delayed Cop City so far, and each year they keep some trees standing is a year that the forest can continue to cool the air and sequester carbon, and can continue to provide space for recreation, ceremony, adventure, and reconnection. The people of Atlanta, and their supporters globally, are defending the Earth from the world of Cop City, Hollywood Dystopia, the Metaverse, the very world of alienating labor that requires police enforcement.

[1] An Atlanta-based forest defender, who goes by Saturn, explained by email that the damage likely cost well above this reported amount: “Considering an entire main construction trailer and machinery was completely destroyed, as well as the costs of repair all the damaged silt fencing, another local contact and I have decided that the APF would of course submit a conservative estimate of the damages cost partly due to how much info the spokesperson would have when commenting on the incident, as well as their strategic motivation for minimizing the costs of the damage done.”

[2] “An Historic Action in a Forest Outside Atlanta,” Unicorn Riot, March 18, 2023.

“Opposition Grows to Atlanta ‘Cop City’ as More Forest Defenders Charged with Domestic Terrorism,” Democracy Now!, March 9, 2023.

[3] Jessica Bryant, “AUCC and Morehouse College Students, Faculty Speak Out Against Atlanta’s ‘Cop City’,” Best Colleges, February 6, 2023.

[4] Marx used this term with reference to capitalists’ reliance on unemployed populations to bring down wages and discipline proletarians.

[5] William Robinson, The Global Police State (London: Pluto Press, 2020).

[6] Anna Simonton, “Inside GILEE, the US-Israel law enforcement training program seeking to redefine terrorism,” Mondoweiss, January 5, 2016.

[7] The slogan derives from “Against the Airport and its World,” used by France’s Zone à Défendre struggle. Night Owls, “Night Owls #4: Winter’s Embers,” It’s Going Down, April 11, 2023.

[8] Bruce Bower, “Indigenous Americans ruled democratically long before the U.S. did,” ScienceNews, September 6, 2022.

Kay Givens McGowan, “Weeping for the Lost Matriarchy” in Daughters of Mother Earth: the wisdom of Native American women edited by Barbara Alice Mann (Santa Barbara: Praeger Publishers, 2006), 53–55.

[9] Community Movement Builders, “Liberated Zones.”

[10] Wood jokingly replied, “That’s when trees call you the n-word, right?”

[11] Matthias Schmelzer, Andrea Vetter, Aaron Vansintjan, The Future is Degrowth: A Guide to a World beyond Capitalism (London: Verso, 2022).

[12] Abundia Alvarado and Dan Fischer, “Stopping Cop City and Reconnecting with Abundance,” New Politics, January 14, 2023.

[13] Weelaunee Web Collective, “Defending Abundance Everywhere: A Call to Every Community from the Weelaunee Forest,” Crimethinc, March 2, 2023.

[14] Mariame Kaba and Andrea J. Ritchie, No More Police: A Case for Abolition (New York: The New Press: 2022), 143–144.

[15] Mark Neocleous, “Theoretical Foundations of the ‘New Police Science,’” in The New Police Science, edited by Markus Dubber and Mariana Valverde (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006), 24. Policing of the “workless” can especially be seen in the criminalization of houseless people through street sweeps, tickets, citations, and arrests over behaviors like sleeping, loitering, seeking donations, and loitering. See National Coalition to End Homelessness, “Is Being Homeless a Crime?,” June 1, 2021.

[16] Leandro Herrera, “They gave their life to Stop Cop City,” Tempest, March 13, 2023.

[17] Fayer Collective, “Shmita Means Total Destroy,” Jewish Currents, January 30, 2023. By insisting that everything should be free, the Fayer Collective leans toward an anarcho-communist direction shared by many past Jewish anarchists including Emma Goldman. By contrast, the parecon approach, proposed in this issue by Robert Hahnel, maintains a role for work-based remuneration.

[18] Jack Crosbie, “The Battle for ‘Cop City’,” Rolling Stone, September 3, 2022.

[19] Schmelzer, Vetter, and Vansintjan, The Future is Degrowth, 232–237.

[20] Abigail Suzik, Surrealist sabotage and the war on work (Manchester University Press, 1998), 2, 15.

[21] Suzanne Césaire, “Surrealism and Us” (1943), in The Great Camouflage: Writings of Dissent (1941–1945), edited by Daniel Maximin, translated by Keith Walker (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 2012), 34–38.

[22] Unicorn Riot, “Defending the Atlanta Forest,” Unicorn Riot, October 9, 2022.

[23] Kaba and Ritchie, No More Police, 143–144. Neocleous, “Theoretical Foundations,” 35–36.

[24] Community Movement Builders, “Liberated Zones.”

[25] Charles Bethea, “Tots vs. Cop City,” New Yorker, January 30, 2023.

[26] David Peisner, “The Forest for the Trees,” Bitter Southerner, December 13, 2022.

[27] This was all well before the March 5 arsons and property damage. There had previously been much smaller acts of vandalism against machinery in the forest.

[28] See Setting Sights: Histories and Reflections on Community Armed Self-Defense, ed. scott crow (Oakland: PM Press, 2018).

[29] Anonymous, “At the Wendy’s: Armed Struggle at the End of the World,” Ill Will Publications, November 9, 2020.

[30] These fires have probably killed insects and rodents, but even this isn’t taken lightly. Eco-sabotage guides instruct great caution to avoid harm to animals.

[31] Kaba and Ritchie, No More Police, 149.

[32] Anarchists will hope that successfully liberated zones could also eliminate the “market system” and “state governing apparatus” that CMB thinks can be bent to serve communal needs in the short term.