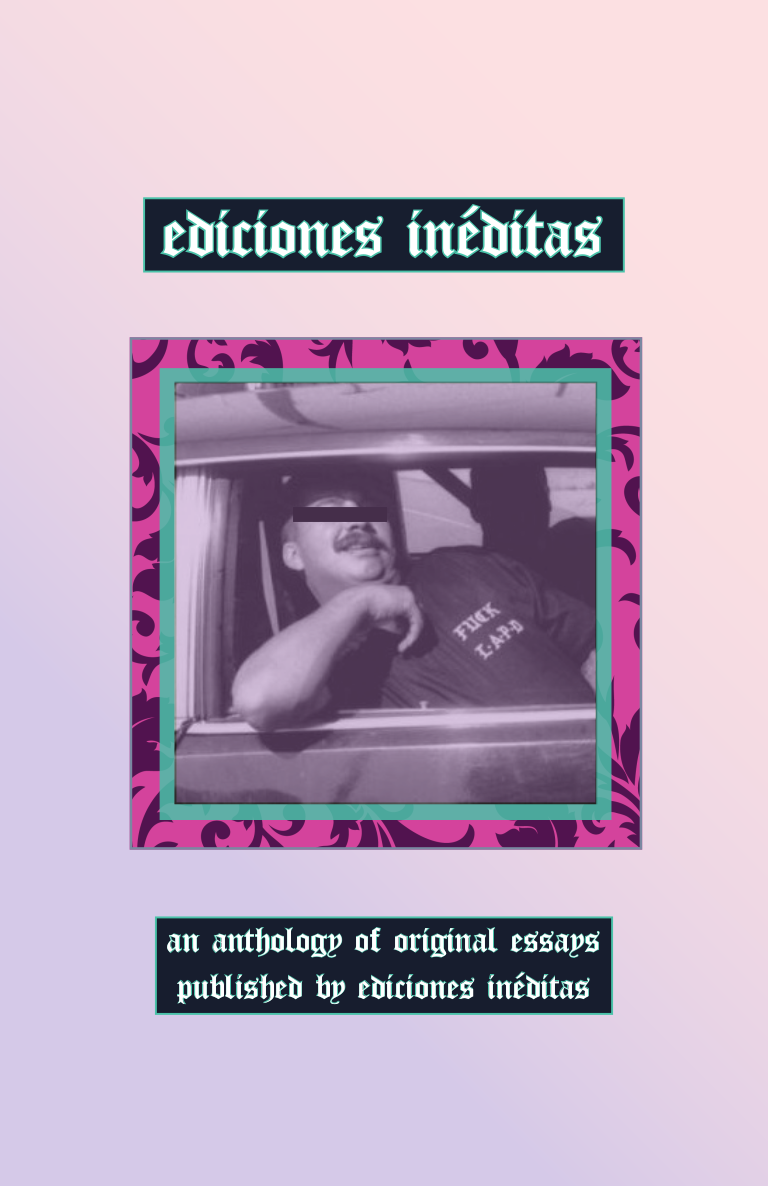

ediciones inéditas

Ediciones Inéditas Anthology

an anthology of original essays published by ediciones inéditas

Contra Aztlan: A Critique of Chicano Nationalism

Against All Nation-States, Against the Police

Contra el nacionalism, por el comunismo y anarquia!

The Broad: Class Hatred, Concentrated

On the Poverty of Chicanx Artists

An Experimental Thread on the Commune and Communism

Communization and Decolonization

An L.A. Radical Memory Rant Against Erasure

The Psycho-Geography of Gentrification in L.A.

But We Have To, So We Do It Real: Slow On Anti-Work, Mexican(-American)s and Work

Anti-Work / Anti-Capitalist: An Introduction

¿Pero Como Resisteremos Por Mientras? / How Can We Resist Right Now?

Note on the font used for the ediciones ineditas logo and cover: this font was recently popularized by White artist, Cali DeWitt when he used this font for merchandise for Kanye West. This was a fontfirst used by Chicanxs in the 80s, most notably on sweaters made to memorialize those recently deceased, often by gang or police violence. Using it here is an act of taking back what a White artist has appropriated for their own financial gain & furthering of their career off of Chicanx pain and cultural innovation.

A Note on Authorship

Unless otherwise stated, the author of the work is Noche.

Works translated by Ediciones Inéditas are not included in this compiliation.

Letter from an Ineditor

What was intended as a small translation project among a few friends grew into a thing whose reach somehow spilled across borders and languages. To translate international radical texts which often go unread by Anglophone readers due to a language barrier and which also often go untranslated since they break with classical anarchist & communist orthodoxy: the ultra-left with its impossible positions.

What this project proved is that there is indeed a deep interest in the ultra-left in 2019 and which the spreading wave of proletarian revolt will only deepen. We would often get messages expressing having not previously heard of ideas such as the abolition of work, a vision of anarchy & communism beyond worker self-management, the abolition of money, a critique of democracy, communization, a critique of art, etc.

I can only hope that this project helped people understand this world we live in and the way that some of us seek to radically transform it. I also hope that it served as a nexus point where people could link up and talk to each other across languages & borders: the kind of correspondence we need more and more of these days.

To my Black, indigenous and other comrades of color: write, act & be active in this world. Your thoughts & actions are more than ever needed to clarify and deepen our positions against this world. Let’s vibe.

Unfortunately the project outgrew its ineditors and we decided to fold instead of further burning out. But true to the ultra-left & insurrectionary anarchist projectuality, this does not spell the end of our activity. We continue on but in other capacities.

Most of the original essays written by me were written quickly, for better or worse, and often as a reaction to something happening in the world or in my life, hence their brevity. And as I wrote, and translated, I learned more about what I desire and what I reject. We learn by doing more so than through simple contemplation. I invite you to attempt to write out your own dreams & nightmares. You may find comrades who feel (or think) the same way as you and from that bonds can form which can break this world.

North of Yangna,

Noche of the so-called Los Angeles Eastside

Prole Wave

A recent wave of protest activity against climate change, and general environmental degradation, has been seen around the world. But curiously open revolt around the world has not centered around climate change itself, but rather around circulation struggles: the name for struggles that occur beyond the point of production; i.e. around the distribution or consumption of commodities. These struggles largely have revolved around the price of a commodity which is directly linked to climate change: petroleum.

In 2017 Mexico went through the gasolinazo: a rise in the price of gasoline (20%) due to then Mexican President Pena Nieto’s privatization of the Mexican oil industry bringing about removal of price controls. Riots, looting and blockades rocked the country. In 2018, the Gilets Jaunes movement rose up and rocked France (& its territories) with riots, looting and blockades. The spark: a rise in fuel prices due to French President Macron leveling carbon taxes, as part of a plan to stem climate change, put on the backs of rural proletarians that need cheap fuel to get to work or go about basic errands since there is little public transportation infrastructure in the French rural and semi-rural countryside. In Haiti, fuel shortages and price harks have also sparked open revolt, along with fighting a government which is openly-aligned with U.S. interests. More recently, Ecuador has been gripped by an insurrectionary, largely indigenous, wave that has also been set-off by a rise in fuel prices: the president, Lenin Moreno, had planned to cut fuel subsidies as part of an agreement with the International Monetary Fund austerity plan as part of a loan to deal to with Ecuador’s debt and fiscal deficit (the plan has been recalled, halting the revolt for now). In all cases, except Haiti, the price hikes have been addressed after governments & national economies were rocked by proletarian revolt.

Comin Situ

Replying to @Breakaway_chi

We are witnessing the advent of mass struggles against climate barbarism as imposed by fiscally desperate states on their proletarian and surplus

1:21 PM • 13 Oct 19 • Twitter Web App

Now, if the proletariat around the world seems to fervently want fuel, and at a low cost, what are we to make of the real need to address climate change? The problem, as we see it, is that liberal ecologically-minded individuals & groups typically conceptualize climate change in the abstract (think of all this talk of humans going extinct), whereas the proletariat reacts to climate change via its material manifestations. Why? Because they have no other choice. In some parts of the world proletarians are directly dealing with rising seas, but what does this reality mean to proletarians in Forth Worth, Texas? The same reason the proletariat does not produce communes or communism out of some ideal, but out of a real material need. (We’ll address the role / position of the radical later.)

Returning to the question of communism, we recall the words of Italian insurrectionary anarchist, Alfredo Maria Bonanno:

“We must counter the satisfaction of spectacular needs imposed by consumer society with the satisfaction of man’s natural needs seen in the light of that primary, essential need: the need for communism.

In this way the quantitative evaluation of needs is overturned. The need for communism transforms all other needs and their pressures on man. ”

Armed Joy (1977)

How then do we counter the spectacular needs imposed by this society? First we should clarify that proletarians largely do not need fossil fuels. This is an imposed false-need, just like employment (or some way to get money) is an imposed false-need. Do proletarians need consistent access to cheap gas if they live in a world where work has been abolished?

The rise of circulation struggles we noted above open up the possibility to demonstrate that the real need of the proletarians is not free, or cheap, access to x, y, z commodity, but rather a world where our lives are no longer dependent upon commodity-production itself. Abolition out of need, not mere ideals. In Chile a fare hike, on top of an already high cost-of-living for proles, has instigated a wholesale revolt against the State, its brutal State-of-Emergency & capitalism in general. High school students self-organized MASS fare evasions, which others quickly joined in, and it was only a matter of time until the whole country came to a halt. The struggle in Chile is also a circulation struggle, but here the commodity in question is the price of transportation. But as comrades in Chile have noted, part of their struggle is not only against the fact that free movement comes at a price, but that human life has further commodified on a class basis.

This is the link that Extinction Rebellion misses, and other idealist, class-agnostic environmental movements as well. That the climate crisis is a product of a certain set of coercive capitalist social relations and not just bad management on behalf of our so-called representatives in power. (We’ll get to more on Extinction Rebellion later on).

These circulation struggles are part of the beginning of a movement against not only against Capital but also climate change. How? As part of the course of circulation struggles giving way to open revolt, proletarians will begin to realize through struggle our problem is not merely the price (or lack) of fuel, but the fact that fossil fuel is a commodity that is only as crucial to us in a world that moves at the speed of Capital. All the cars on the roads with proles heading to jobs they hate; all the fossil fuels burned to generate electricity for content delivery networks bringing the latest non-news to smartphones and the jet fuel burning in the sky for global commerce...is only necessary for a world where Capital reigns.

The speed of human life was profoundly slower for much of what we can call human history. And a return to a much slower speed would not only be beneficial to arrest the causes leading to deepening climate change, but it would do wonders for our mental & physical health. Work is literally killing us and this world. Anti-work as de-growth, to use a hip new term.

Responding to climate change as some sort of global, abstract thing (i.e. human extinction) will likely not be the basis of the movement the abolish the present state of things: i.e. communism. You can see where that leads: groupuscules like Extinction Rebellion UK which openly work with the police and call the police on those who exceed their notions of protest / resistance. Whereas most racialized proletarians know that the police are always our fucking enemy and never an idle, protective force. Proletarians do not fight capitalism at a global, abstract level; they fight it at their local level, but with an understanding of its global nature.

Social democrats, and other State-agnostic Leftists, ponder State policy to get us out of climate catastrophe: the Green New Deal. We see that the State is inherently part of the climate catastrophe when the U.S. military is itself the greatest consumer of fossil fuels.

Recently, Extinction Rebellion staged actions around London to halt the London Underground, and specifically blocked a train at Canning Town (a working-class district of East London, England) by climbing atop it and faced angry commuters who dragged them down, pissed-off at the disruption. We recalled the freeway takeovers in the U.S. during the height of open proletarian Black Revolt (#BLM), between 2013 ~ 2015, against anti-Black policing (and this anti-Black world) and then we also saw angry commuters, but this anger was quite often racialized: lawmakers even passed legislation that would absolve angry commuters of killing protestors block their way (who were largely Black).[1] Angry white Americans wanted to mow down angry Black protestors and now had the blessing of the American Legal System.

Then the difference?

Some will say that proletarians aren’t at all responsible for environmental degradation. That it’s the fault of the capitalist class. Unfortunately this isn’t entirely so. The commuters in Canning Town did in fact need to go to work, so that they can get by as all proletarians are compelled to do, and it is this world of work that is a key component in environmental degradation.

But we should note instead that this degradation, that all workers are a part of, is also a part of the coercive relations which also degrade our very lives.

So then the difference?

During the Black Revolt of recent years it was Black proletarians, and their comrades, acting together & materially against this anti-Black capitalist world. With XR we have a largely liberal, and by all accounts fairly white & middle-class[2] movement whose direct actions still are meant to act at the level of Spectacle. As a comrade noted:

Extinction Rebellion is doomed to extinction because it has no tactical aptitude and is fighting on the spectacular terrain of the enemy by relying on the moral sensitivity of the spectator’s heart.

6:15 AM • 17 Oct 19 • Twitter Web App

We must go beyond spectacular moralism to find a way out of capitalism and the climate crisis it has wrought in the pursuit of infinite growth.

This is not to say that the success of an action is the number of proles who agree with it. Not all proles will welcome the measures necessary to bring about free communal lifeways. There will be open reactionaries we will need to defend against, but the actions of proletarians against capitalism, and NOT actions directly against proles, will be what will help us win the day.

For example: If XR had instead done what has occurred in Chile with mass fare evasion, their efforts would have built solidarity with their movement but instead they chose to attack those who benefit the least from this world. And now we see a broad movement against capitalism growing in Chile.

As we said a couple of days ago when images of Chilean proletarian looters were seen chucking flat-screen TVs into a bonfire and some people noted how ‘wasteful’ and ‘toxic’ these acts were.

ediciones ineditas

@edcns_ineditas

If yer more concerned abt the ‘wastefulness’ of destroying a S , or its toxicity, than the fact that a nation’s proletariat is waging offensive class war then we know yer not on our team. What’s rising is the horizon of communism & anarchy which is the ‘greenest’ shit possible.

2:37 PM ■ 10/20/19 ■ Twitter for Android

To the homies

The task at hand for radicals, as we see it, is not necessarily to raise climate consciousness (mass media already provides endless terrorizing click-bait on this issue) but to push the proletarian revolt emerging around the world to generalize so that the horizon of communism draws nearer and nearer. We will always be in the minority, but we understand that communist revolution (as we see it) is not the concerted actions of those self-identified as communists but the proletariat expressing its immanent capacity to abolish its condition as the proletariat which just means proles are the ones that are gonna get ourselves out of this mess by destroying this world that marks us as proles.

We can begin to strategize & actualize preparations for climate catastrophe where we live, and build networks of solidarity and mutual aid, but the climate will likely not kill off capitalism for us so we must understand we will still have to meet our global enemies on the streets, in the mountains, in the valleys and at the ports. This image made by Chilean comrades sum up what we feel is necessary.

ALGUN DIA LA SOLIDARY LES HARA TEMPLAR / SOMOS COMUNIDAD EN LUCHA / POR LA COMUNIZACION DE LA VIDA

tr. “One day our solidarity will make them tremble. / We are community in struggle. / For the communization of life.”

The Real Death Of Politics

Trump has been sworn in, the Left and Liberals have come out in droves to denounce a president whom Congressman & Civil Rights Leader, John Lewis, has declared illegitimate. Though the grounds for illegitimacy, as he states, are not necessarily based on Trump’s racist, sexist, isolationist, ultra-nationalist, anti-queer agenda but rather that he is the subject of a Russian conspiracy. (Though we have had presidents who have been slave-owners, rapists, leaders of genocide, fervently anti-queer and yet they were able to complete their terms.) Others more generally decry Trump as a Neo-Fascist set to bring 1939 onto American soil. The U.S. Radical Left clamors to revive itself and swell its numbers. Though this Radical Left has chosen, more and more so, to speak the language of politics rather than of revolt (or revolution). This Radical Left sometimes speaks of communism as a set of affairs to be installed, and to which proletarians must be won over to, rather than the means by which proletarians will free themselves.

In Mexico, there are already some who are finding a fruitful ground for a rupture away from capitalism and politics. Though even there it is commonplace to point to the more radical elements of the response to the #Gasolinazo (state mandated rise in fuel prices) as part of a deep-state conspiracy to discredit more populist responses: marches, protests, list of grievances.

Here in the U.S. we had massive marches across the country, under the umbrella name “Women’s March” (on January 21st). A variety of critiques have been directed at it: its centering of white womanhood & its feminism, the trans* exclusionary images & slogans, its championing of non-violence and a generally pro-police sentiment. On Trump’s inauguration day, January 20th, we saw the black bloc emerge, with an attempt at demonstrating both a show of force but also to disrupt as much as possible the pomp & circumstance of the day. Though we all delighted in the punch-out of Richard Spencer, self-proclaimed leader of the “alt-right” movement, by someone dressed in black bloc we could say that the same critique could be made of both the “Women’s March” and of the black bloc: they both were a but response to a political moment. A political moment which bears deep consequences for this country and for the world, but a political moment all the same.

Largely, most of the large-scale revolt we have seen in the United States, and around the world, the last few years have not been a reaction against a political moment, but ferocious responses to domination both economic and direct. See:

-

the #Gasolinazo

-

Ferguson

-

Baltimore

-

Labor Reform in France

-

Education Reform in Mexico

An attempt to create revolt has always been the modus operandi of the Left and even of Left-Anarchists in a vanguardist way. Rather, we contend the task at hand is to foster and help further along revolt, but the Left can only see the world politically even when it has its historical-materialist glasses on.

The Democratic Party is essentially dead in the water. Many on the Radical Left are not deriding party politics, or parliamentary politics but rather are calling for a working-class party. To push for a political party at that moment when voter turn-out has been at its lowest in decades is not only politically unsound, it is tone-deaf.

“Granted, we don’t have a political party in the United States. We don’t have a labor party. And we’re a long way away from becoming a force that can enact policies to represent and empower the working class. But we’re building momentum and making demands.”

–Jacobin Magazine, “The Party We Need”

The Radical Left offers more of the same because their strategy and tactics are precisely centered on a field where workers, whether racialized, gendered, employed or not, have not been able to win in decades: politics.

We are still speaking of a new cycle of struggle in the worn-out language of the old. We can refine that language as best we can, but we have to recognise that it is nearly, if not completely exhausted.

–Endnotes, “Spontaneity, Mediation, Rupture”

This language is largely the language of politics which boils down the capacity for any substantive change in our lives into polls, charts, numbers and voting turn-outs.

If Not Politics, Then What?

One of the prevailing guiding principles for those of us of the insurrectionary kind is reproducibility:

“Concretely, reproducibility means that acts of sabotage are realised with means...that can be easily made and used, and that can be easily acquired by anyone. [...] Reproducibility also encourages the radicalisation of the individual or collective acts of attack, extending to the maximum the autonomy amongst individuals and collectives, generating, when one desires, an informal coordination in which, outside of the logic of dependency or acceptance, one could also come to share the knowledge of each comrade concerning sabotage.”

–Revista Negacion, “Reproducibility, propagation of attack against power and some related points”

Reproducibility means bringing extra masks to the looting street party, letting the people you trust know how easy it is to X or Y against the police, showing people how easy it is to be as-close-to-invisible online, disseminating simple ways to scam corporations to help you get-by. Reproducibility guides us in our attacks against the State & Capital, but attacks will not carry the day for the creation of communism. This is often the critique directed at insurrectionary anarchists: that we bear no image of what a future communal way of life may hold and how it would be formed. Though any substantive reading of intelligent insurrectionary anarchist literature would demonstrate otherwise, our fellow travelers in the communization current do bear the productive notion how we can act in the here and now by way of communist measures:

“A communist measure is a collective measure, undertaken in a specific situation with the ways and means which the communist measure selects for itself. The forms of collective decision making which result in communist measures vary according to the measures: some imply a large number of people, others very many fewer; some suppose the existence of means of coordination, others do not; some are the result of long collective discussions, of whatever sort (general assemblies, various sorts of collective, discussions in more or less diffuse groups) while others might be more spontaneous... What guarantees that the communist measure is not an authoritarian or hierarchical one is its content, and not the formal character of the decision which gave rise to it.”

–Leon de Mattis, “Communist Measures: thinking a Communist Horizon”

Here we have demonstrated the suspended step of communization which makes communism possible without the proletarian seizure of political power and which makes of communism not a state of affairs but rather a process which proletarians actively engage in from the very beginning of revolutionary activity. Though our comrades in the communization current claim that now is the historical moment when communization is possible, insurrectionary anarchists have contended that the time has always been right. A reading of the illuminating text, Dixie Be Damned: 300 Years of Insurrection in the American South, demonstrates that something akin to communization as the way towards a communal way of life is not hard-encoded into any particular historical moment, rather it is has long been the way that oppressed peoples have responded to the State actively trying to control them, their way of life and as the means to be able to flee slavery and colonization, while making communal and autonomous life possible. Ex-slaves and their comrades would routinely raid plantations so that they could live outside of slave society and would often not make any political demands of the State. Those involved in this raids (appropriation as a communist measure) would be as much interested in disrupting and destroying slave society as much as they wanted to be able to live outside of it.

What we need to be speaking of in this moment is not a zero-sum game of recruitment of the workers, or the surplus population, or whatever to our side. These days hardly anyone but Radical Left die-hards bask in proudly calling themselves workers. For most, work is a drudgery imposed which bears no possibility of bearing a positive program. We often see our work as that which is destroying our lives and the world we live in, rather than contributing to a positively-viewed development of the means of productions necessary to make communism possible (to hearken to old productivist notions of communism). We view our identities under capitalism as impositions which can prove to be sites of antagonism against this society. Though we reject identity-politics, we also understand that favoring a class-reductionist worker-identity to unite us is yet another form of identity-politics.

The Anti-Political Turn

This leads us to a final point. Though we found the Arab Spring inspiring, we would roundly say that its failure to move beyond its initial success was that it relied heavily on populist rhetoric around democracy, (political) freedom, transparency and anti-cronyism (The same critique could broadly be said of most of the Occupy Mov’t). Its attacks against the State and its forces were awe-inspiring but falling short of a rejection of the State in toto and of capitalism allowed a return to normality that we see there today. This is why we describe our position towards politics as anti-political.

There will always be push back against us by Liberals and the Left when we act in a way that views them as unnecessary. We will be called upon to explain our position and how it could be constructive or productive. Such debate is ultimately meaningless. Some of us have already been attacked by Liberals and the Left for expressing this very position. We would contend that our actions may at times require some explanation but those who see us riot, loot, fuck-shit-up and are inspired are often those who have the most to gain from the fall of this society. Those who have the most to lose will use whatever means necessary to stop us and we can understand why. Those of us who struggle to get by will not flinch when the ultra-rich get theirs.

This anti-political wave may take on different names according to its context: proletarian insurgency, les casseurs, the invisible party, los desmadrosos, thugs, etc. but they all point away from relying on the state to recognize us as citizens to negotiate with. The point of course is not to merely be ungovernable but to be able to initiate, with our revolting actions, the means to live free of the State, Capital, Patriarchy, Colonization and Work. If we merely react to what Trump’s presidency may or may not do, we then foreclose the wide breadth of actions we may take. If we foreclose our actions around anti-fascism, we would end up with a return to a normality which was already genocidal and miserable but which would not be called fascism.

Lastly we end with Leon de Mattis further clarifying what the nature of what couldbe communist measures:

Likely to be communist, then, are measures taken, here or there, in order to seize means which can be used to satisfy the immediate needs of a struggle. Likely to be communist also are measures which participate in the insurrection without reproducing the forms, the schemas of the enemy. Likely to be communist are measures which aim to avoid the reproduction within the struggle of the divisions within the proletariat which result from its current atomisation. Likely to be communist are measures which try to eliminate the dominations of gender and of race. Likely to be communist are measures which aim to co-ordinate without hierarchy. Likely to be communist are measures which tend to strip from themselves, one way or another, all ideology which could lead to the re-establishment of classes. Likely to be communist are measures which eradicate all tendencies towards the recreation of communities which treat each other like strangers or enemies.

Nice Shit For Everybody

We hereby reject any form of self-imposed austerity. We posit that we want nice shit for everybody and that is not only feasible but desirable. We will not put forth graphs announcing how much work (or not) will require such a project but will state that such a project is part of our desire for communism. We hereby reject all forms of feigned punk slobbiness, neo-hippie shabby chic, or pajamas in the outdoors. We see the stores in the bourgeois parts of town (& the newly-gentrified ones too) and say that we want that shit and even more. Capitalism is that which stands in the way of us having the shit we want with its hoarding of commodities only to sell them to highest bidder. We’ve been told to live with less and less by not only Green Capital, but by the Church, by our liberal “friends” and even by fellow comrades. Fuck that shit. Nah: if we’re going to be putting our shit out on the line it’s definitely not going to be so that I can live simply.

Is this commodity-fetishism? Yes, of

the worst kind. Mainly, it’s the kind that does not want to maintain capitalist social relations, but one that seeks to destroy them. We’ve been living without and we want to remedy this situation. Do we also want to live with the deepest, most sensual set of social relations: yes. But why must we choose between the two? The destruction of capitalism, for communism, will leave us with so much time to cultivate ourselves, our tastes, our desires. Pre-capitalist peoples did not dress themselves in tunics of ash gray or shave their heads en masse. It is capitalism which has made our self-fashioning so impoverished; though glimmers of indulgent self-fashioning sometimes does grace the streets; sadly only to be homogenized, recuperated and sold back to an indiscriminate consumer. It is capitalism which has accustomed us to bland food & drink, or tricked us into paying top dollar at the co-op.

It is capitalism which has us moving our IKEA furniture from apartment to apartment. We imagine all the home furnishings to be plundered. Capitalism in its poverty of ideas, by way of colonialism, plunges itself into our indigenous cultures and sells us back what it took from us. We still remember that we used to build structures that still stand while cheap buildings kill so many now in disasters. We still remember that European colonialism spread its tentacles across the world because it was without and we lived in such wealth (after it had plundered its own).

“I want to shed myself of my first-world privilege and not live confined by how capitalism wants me to.” If only it were so simple. We’ve actually read this sentence (though its intent we’ve seen many, many times). This is pure reactionary thought. To run and do the opposite just because capitalism displays certain social features does not make one an anti-capitalist. It makes you a petit-bourgeois bohemian. We all want to not pay rent, or pay for food, or have to work so many hours of our lives but there is no outside of capitalism. Asceticism is not revolutionary. Even those nodes of “autonomy” scattered around the globe, like among the Zapatistas, or Marinaleda, Spain still have to contend with the fact that Capital has them surrounded. But we will not squat our way to a revolution. Squatting, dumpster-diving, train-hopping, stealing from work, work slowdowns are not acts of revolt but of resistance. Thus we understand that the nice shit will not come until capitalism is done with, because little acts of appropriation will not really get the goods as we see fit.

This is no mere provocation: it is part of our intent. Communism, for us, is not as we were taught in schools: the general immiseration of everyone, but as Marx so eloquently put forth in 1845, “the real movement that abolishes the present state of things.” The present state of things is poverty, hunger, work, racialized social death, gendered violence, the unmitigated murder of transgender people, the free movement of goods but not people and the general immiseration of everyday life.

Further, a critique of consumerism (& likewise Capital) that only asks us to consume less misses the trees for the forest. Capital would have us consume less only to appease our consumer guilt. Let us not be fooled, Capital necessitates eternal growth and this growth is done on terms that will destroy us regardless of how much (or little) we buy. Capital has made a sin of our desires because they inevitably know that it cannot satisfy them. To each according to their need, and to each according to their desire. We contend with capitalist logic and aim for the unreasonable because capitalist logic would have us cut ourselves from our ludic, indulgent dreams.

Contra Aztlan: A Critique of Chicano Nationalism

The cap above is an image making the rounds as a counterpoint to now-President Donald Trump and the hat that he’s made (in)famous. It serves as a visual reminder that a great deal of the U.S. territory was once Mexican national territory. A Chicanx act of detournement.[3] Though it’s an act of detournement which lacks a critical analysis of Mexican history. That such much of the Chicano movement’s nationalist fervor arises from Mexico’s territorial loss at the hands of U.S. racist aggression. This resulted with the Treaty of Guadalupe in 1848, which ‘ceded’ the territory now known as California and a large area roughly half of New Mexico, most of Arizona, Nevada, Utah and parts of Wyoming and Colorado to the USA.[4]

Last year, two artists undertook the task of surveying the northern border of Mexico as it was in 1821, marking it with obelisks that lie well within the current U.S. borders. Today we refer to this historical form of the Mexican republic as the First Mexican Empire; this empire extended well into the Central America, extending into the national territory of Costa Rica. If these artists were to survey the southern border of this Empire then we would begin to see the glaring oversight of this project. Yes, they claim to want to show the transient nature of borders but they inadvertently highlighted what the project of the Mexican republic is really about: the extraction of Capital to be found within its borders without the need of wars of aggression (colonialism); a project which prefers the class warfare of privatization of natural resources[5] held in common and the extraction of surplus value from its native, Black and mestizo populations. Once this State project held a territory which was once much more vast. The nostalgic picture of a peaceful homeland that Chicanxs often project onto Mexico begins to lose its luster. Yet from this nostalgia is born much of Chicano Nationalism.

¿Aztlan Libre?

It is the Chicano poet, Alurista, whom is largely credited with spreading the story of Aztlan as the mythic homeland of the Mexica. He also wrote what would become the leading document for Chicano nationalists: El Plan Espiritual de Aztlan. In it we find the first few fundamental errors in Chicano Nationalism:

“Nationalism as the key to organization transcends all religious, political, class and economic factions or boundaries. Nationalism is the common denominator that all members of La Raza can agree upon.”

Hic salta, hic Aztlan: a new nation to arise in what is currently the U.S. Southwest/ West as part of the assumed patrimony of all Chicanxs, by way of a supposed shared ethnic heritage.[6] As an anti-state communist I desire the overthrow of capitalism en su totalidad. How then could even Chicanx anti-state communists/ anarchists support a plan which would inevitably align us with a new national bourgeoisie? The contradictions are glaring and would result in no liberation of the actual people which would make up this “Chicanx nation” from either wage labor or general exploitation. Yet another revolution forestalled in the name of national sovereignty. Though there may be certain things which bind Chicanxs across these “factions” and “boundaries” which Alurista alludes to, it is these binds that dampen the communist project which understands that the notion of a Chicanx Nation is a false one. Fredy Perlman, in his incendiary essay The Continuing Appeal of Nationalism, wrote:

“[One] might be trying to apply a definition of a nation as an organized territory consisting of people who share a common language, religion and customs, or at least one of the three. Such a definition, clear, pat and static, is not a description of the phenomenon but an apology for it, a justification.”

This fabricated justification is used to allow the project of capitalist exploitation. Further, if we were to begin to analyze this homeland which Chicano Nationalists hope to reclaim we also run into the fundamental contradiction wherein this supposed homeland has already been continuously occupied for millenia by many different Native peoples. To mention a few: the Tongva-Gabrielino, the Chumash, the Yuman, the Comanche, the Apache, the Navajo and the Mohave.

Further, the Plan Espiritual de Aztlan states that Chicano Nationalists “declare independence of [their] mestizo nation.” Here creeps in the danger of a new form of oppression: yet another settler-colonial, mestizo nation once again makes an enclosure around Native peoples. Though the National Brown Berets, a Chicano Nationalist group, instead claims that.

“The amount of mixture of European blood on our people is a drop in the bucket compared to the hundreds of millions of Natives that inhabited this hemisphere. The majority of us are of Native/Indigenous ancestry and it is that blood that ties us to and cries out for land.”[7]

A strange play of blood belonging lays the groundwork for a presumed claim to Aztlan. Kim Tallbear, an antropologist at the University of Texas, Austin and a member of the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate of South Dakota, laments:

“There’s a great desire by many people in the US to feel like you belong to this land. I recently moved to Texas, and many of the white people I meet say: “I’ve got a Cherokee ancestor”...That worries us in a land where we already feel there’s very little understanding of the history of our tribes, our relationships with colonial power.”[8]

Chicanxs are the historical product of colonialism, racism, capitalism, slavery genocide and cultural erasure. Part of the struggle to liberate Chicanxs (and all people) would inevitably incorporate the reclaiming of lost ancient ways, but this cannot overtake the struggle of Native peoples who have managed to maintain a direct connection to their deep past & present. Indigeneity is more than just genetic heritage; it is a real cultural link. And a politics based on genetic heritage begins to look more and more eugenicist.[9] It is unclear how the Chicano Nationalist project would differ from the sovereignty that the American Colonialists merchants (“Founding Fathers”) sought to establish from the English Crown.

Against All Nation-States, Against the Police

The original 10-point Program of the Brown Berets includes the demand that “all officers in Mexican-American communities must live in the community and speak Spanish.”[10] Forty-seven year later in 2015, the LA Times reported that 45% of the LAPD force is Latino and yet relationships between the LAPD and the city it overlooks remain strained.[11] It could be said that at the time of the drafting of this program that this was a radical demand, but 61 years prior there is an anecdote that exemplifies that Mexican-Americans had already known another way was necessary.

“.scores of cholos jumped to their feet and started for the spot where the [LAPD]officer was supposed to be sitting. If he had been there nothing could have prevented a vicious assault and possible bloodshed”[12]

Now the context: Mexican-American LAPD Detective Felipe Talamantes, along with other Mexican-American LAPD Detectives, arrested three members of the P.L.M., a Mexican Anarchist-Communist organization, in Los Angeles under trumped up and false charges in 1907. At the time it was noted that it was highly possible that the LAPD detectives were working under direction of the Mexican Federal Government, then headed by dictator Porfirio Diaz. It was seen as a way to clamp down on Mexican radicals in the USA just prior to the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution in 1910.

Someone in the courtroom said that Det. Talamantes might have been in attendance at a hearing resulting in the scene described above with the jumping cholos. At the time there was already a very strained relationship between the LAPD and Mexicans in Los Angeles. Consequently, there was massive support by Mexicans, Mexican-Americans and white radicals for the three anarchists. Noting that on principal, all anarchists are against the institution of the police. Throughout their imprisonment they were able to raise a remarkable $1,950 in their defense: remarkable in light of the meager size of the contributions ranging from $0.10 to $3.00.[13] This anecdote is so telling since it mattered little to the those who supported the 3 arrested that the LAPD detectives were themselves also Mexican-American. These detectives were clearly understood to be complicit with the white-majority which controlled the conservative power structure which was local governance at the time.

To this day Chicano National Liberation group, Union del Barrio, advocates in Los Angeles what the Brown Berets advocated back in 1968: a Civilian Police Review Board. As the more radical elements of the Black Lives Matter movement call out for the wholesale abolition of the police, Chicano Nationalists, in their racialized myopia, fail to see and acknowledge the anti-Black origins of the police in the U.S.A.[14]

Fredy Perlman notes something curious about pro-nationalists and says:

“It is among people who have lost all their roots, who dream themselves supermarket managers and chiefs of police, that the national liberation front takes root; this is where the leader and general staff are formed. Nationalism continues to appeal to the depleted because other prospects appear bleaker.”[15]

But what is the prospect, however bleak, the anti-state communists offer?

Contra el nacionalism, por el comunismo y anarquia!

Chicano nationalists often talk about “the border jumping over them” to counter the racist narrative that Mexicans are somehow invaders of what is now the American SouthWest. They rail against borders that their parents, grandparents and others have to perilously cross, yet they evidently do not desire the abolition of borders but rather desire a re-drawing of them. Anti-state communists (& anarchists) desire the wholesale abolition of borders, nation-states, capitalism, patriarchy, colonialism and work. Though of course it is a difficult push forward these measures without speaking to the experience of identity, speaking through the lens of a purely national liberationist scope is to speak in half-measures.

Mao Zedong thought, a frequent source of much National Liberation ideology, here is critique by Perlman:

“Few of the world’s oppressed had possessed any of the attributes of a nation in the recent or distant past. The Thought had to be adapted to people whose ancestors had lived without national chairmen, armies or police, without capitalist production processes and therefore without the need for preliminary capital.

These revisions were accomplished by enriching the initial [Mao Zedong] Thought with borrowings from Mussolini, Hitler and the Zionist state of Israel. Mussolini’s theory of the fulfillment of the nation in the state was a central tenet. All groups of people, whether small or large, industrial or non-industrial, concentrated or dispersed, were seen as nations, not in terms of their past, but in terms of their aura, their potentiality, a potentiality embedded in their national liberation fronts. Hitler’s (and the Zionists’) treatment of the nation as a racial entity was another central tenet. The cadres were recruited from among people depleted of their ancestors’ kinships and customs, and consequently the liberators were not distinguishable from the oppressors in terms of language, beliefs, customs or weapons; the only welding material that held them to each other and to their mass base was the welding material that had held white servants to white bosses on the American frontier; the “racial bond” gave identities to those without identity, kinship to those who had no kin, community to those who had lost their community; it was the last bond of the culturally depleted.”[16]

The project of supplying Chicanxs with an alternative to National Liberation, or some other false appeal to Nationhood, is one that is more necessary than ever. As radical Chicanxs who desire to truly free this world (or perhaps destroy it), we should take it upon ourselves to create the rhetoric, the movements, the history which we want to see in the world. I look forward to helping find, create and elevate such work which would fulfill this project of total liberation, not just for Chicanxs, but for oppressed people everywhere.

The Broad: Class Hatred, Concentrated

by Asmodeus, a friend of the project

Eli Broad is a multibillionaire. He made his fortune constructing tract homes, which is to say by pumping hot air into the pre-2007 real estate bubble. Later he moved into life insurance as well. Some of that money ended up bailing out LA’s Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) around the time the housing market was going south — the museum had been hemorrhaging funds for years. It was a maneuver that some have described as closer to a hostile takeover than an act of philanthropy. Notably, Broad’s intervention was closely tied to the arrival of a new director — the gallerist Jeffrey Deitch — who fired the museum’s widely admired chief curator, Paul Schimmel, in 2012. Other wads of cash ended up at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) — where the donor had Renzo Piano build the quasi-autonomous Broad Contemporary Art Museum — as well as the Los Angeles Opera, which promptly used the funds to stage a full production of Wagner’s Ring Cycle. These actions, among others, won Broad a reputation in the art world as LA’s resident Maecenas-cum-Evil Emperor, with Deitch, perhaps, playing the role of a bumbling Darth Vader.

As of September 2015, the city has had a new museum downtown, known simply as The Broad to distinguish it from the edifice at LACMA. It is a clean slate: it exists to display the personal collection that Eli Broad and his wife Edythe have amassed over the previous five decades. The museum’s architecture is by the firm of Diller Scofidio + Renfro. They are perhaps most famous for the High Line that runs through New York’s blue-chip gallery district in West Chelsea. Having already designed what is arguably the world’s first vaporwave structure (the fog-enshrouded “Blur Building” that was their contribution to the Swiss National Expo in 2002), their work in LA further develops the play of circulation, sightlines, and cladding that has become the agency’s signature. The Broad’s initial aspect is unprepossessing, however: its exterior is a drab box with two of the bottom corners shaved off. On one side of the facade there is an “oculus” that stares unblinkingly at the Colburn School (a well-regarded music academy) across the street, as well as at the Colburn’s next-door neighbor, MOCA’s Grand Avenue flagship. On the opposite corner is Frank Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall, the completion of which in 2003 was widely taken as a sign of Downtown’s revitalization. (Eli Broad had a hand in that, too.) If one were to draw lines between The Broad and these other monuments, the resulting triangle would, very roughly, point in the direction of the Westin Bonaventure Hotel about half a mile away, where Fredric Jameson once discerned the hallmarks of postmodern space. New, pricey condos have been sprouting up nearby, some of them connected to the more desirable parts of Downtown by walkways that are literally raised above the plebeian street.

Developers’ dreams notwithstanding, this remains a weird and uncomfortable part of the city, nestled as it is between multiple freeways and the massive homeless encampment that is Skid Row. There are few other parts of Los Angeles where the contradictions of capitalist real estate, of which Broad is a Donald Trump-level protagonist, are so clearly on display. Thus the location is fitting. The building itself is encased in a sheath of corrugated off-white webbing that screens the interior from its surroundings. Most of the perforations in fact conceal windows that are oriented to the rising and falling of the California sun, with the result that the upstairs galleries, at least, can boast some of the world’s most luxuriant natural lighting. These subtleties are little apparent from the street, however. A friend points out that the museum looks like nothing so much as the raw material of menudo: tripe, that is. But whereas menudo is a venerable hangover cure, one suspects that The Broad will remain a headache for some time to come.

Visitors enter the museum through either of its lifted corners, where they find themselves in a gray, cavern-like space. (One of its chambers houses Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirrored Room, 2013 — the museum’s biggest crowd-pleaser, to judge from the lines.) Goofy sculptures by Robert Therrien and Urs Fischer establish a funhouse vibe. Both this area and the galleries are almost extravagantly well-staffed by headset-wearing attendants. Ascending either by escalator, stairs, or in a Willy Wonka-ish cylindrical elevator, one then arrives at the top floor, only to meet a funereal installation of Jefif Koons’ immense, polished metal Tulips (1995–2004), flanked by no less than nine word-paintings by Christopher Wool (Untitled, 1990). A grander imperial reception could hardly be imagined. In the same space there are equally imposing works by Julie Mehretu, El Anatsui, Mark Bradford, and Marlene Dumas, all of which combine a diffusely political charge with market-friendly scale and format: this is globalization as viewed from Sotheby’s. The art is about, and exemplifies, the workings of capital, the market, and the uneven distribution of violence in the global economy. It might even be read as “critical.” Could it be that The Broad is thinking about its own noxiousness? No, it seems: that feeling soon dissipates.

The problem is the collection in toto. There are no surprises here, although there are some very good pieces. There is not a single artwork on display that would give a hedge fund manager qualms. It is all investment-grade, and it is all nearly equally so. The paintings are big. The sculptures are shiny. That said, there are things worth seeking out. The museum’s top floor is by far its best, due both to the quality of the art and to the influence of the punctured ceiling that rains filtered sunlight into the galleries. There are no permanent walls on this level, but only movable barriers that demarcate the exhibition spaces. Half of the top floor is dedicated to art of the 1950s through ‘70s, with a particularly fine stock of American Pop; there is also a cluster of superb paintings and sculptures by Cy Twombly. The other side contains art from the following decades and almost up to the present day. Some galleries are monographic, while others are devoted to small groupings. One, for instance, throws together Damien Hirst with Andreas Gursky — practitioners who seem to have little in common other than a distinctively ‘90s brand of gigantism. Local heroes such as Chris Burden and Charles Ray are also in evidence, while another gallery boasts yet more works by Koons, who is something like the museum’s mascot. Indeed it is interesting that Koons is at the physical center of the inaugural installation, on the axis, in fact, along which the top floor splits cleanly in half. A roll call of postwar greatest hits lies on the one side, mostly ‘90s-vintage art on the other — meaning art that is often concerned with the politics of race, trauma, and gender. This may suggest that it is Koons who mediates from the one to the other, and thus, that there is no nexus other than the extreme of reification that he represents to link the mid-century to its end. Which would be a defensible if depressing art historical argument.

Things go downhill from here, figuratively as well as literally. Descending through the museum’s midsection, where its storage spaces are visible from two portholes cut out of the stairwell (like windows onto a big cat’s enclosure at a zoo), one returns to the first floor, where The Broad displays, or rather stockpiles, its contemporary holdings. There are large, bland pictures by the likes of Mark Grotjahn, as well as an installation of Ragnar Kjartansson’s The Visitors, an irrepressibly cutesy nine-channel video from 2012. The largest exhibition space of all — it is directly beneath Koons’ Tulips, if I am not mistaken — harbors a generous selection of manga-inflected works by Takashi Murakami; their cumulative effect is queasy-making. Karl Marx himself puts in an appearance in a fairly execrable piece by the Polish artist Goshka Macuga, which at least stands out for being slightly less warmed-over than everything around it: it is a photo-tapestry that plasters some of Miroslav Tichy’s voyeuristic snapshots of Czech women on top of a view of Marx’s grave. And that is about all that I remember, or care to. Even the John Currin paintings, typically good for a chuckle at least, look more lethargic (read: less perverse) than usual.

It is sometimes difficult to keep in mind that this abundance of very expensive art was assembled by only two people, so doggedly does it resist the detection of any guiding sensibility other than the sheer will to accumulate things upon which the market has left its stamp of approval. Such anomie may have social significance. This is how a class — a very small class — sees; this is how it dreams. And what banal dreams they are. For granting that insight, The Broad has some value. Yet there is a way in which discussing the details of the inaugural exhibition is entirely beside the point. The collection is a placeholder; one has the sense that it might as well be switched out for anything else of equal value, or painlessly liquidated should Eli Broad ever fall on hard times. Whatever their intrinsic merits, the works are significant, here, primarily as tokens of capital’s supremacy. This is true regardless of the fact that admission is free, and also of the fact that LA already has a multitude of institutions that bear the names of other tycoons (Getty, Hammer, Geffen...). The critique still has to be made anew, if only because the building is new, familiar as everything else about it may be. What this museum means has little to do with what it shows, and very much to do with the relations that it materializes simply by being what it is, where it is, and bearing the name that it does. The scandal is not that The Broad is bad, but that it exists.

Guy Debord said that spectacle is capital accumulated to the point that it becomes an image. Fair enough, except that it is too easy, when thinking or writing about spectacle, to forget what capital is. Capital is dead labor. It is the abstract form of a trillion instances of suffering. Contra Debord, it need not become visible at all, and in fact capital is perhaps most destructive where the social relation that it objectifies is most naturalized and unseen — in the everyday violence of class, race, and gender; in the omnipresence of money and commodities, which are violent forms in themselves because they distribute life and death according to an inhuman logic. Contemporary art is the obverse of this invisibility. This is why The Broad is a shrine to class hatred. As a sponge for surplus capital — its function as a hedge or investment — art absorbs human suffering; contemporary art is therefore class hatred in one of its most concentrated forms. Art takes upon itself the guilt of those who caused that suffering and who think that art will discharge it. But it does not.

About Hating Art

by Asmodeus, a friend of the project

Basically the art world exists to make money for a small number of people and to make a larger number of people feel like they’re cool. The first purpose is just capitalism. The second is an effect of capitalism, because only in a world as ridiculous as ours would standing around in mostly empty white rooms be considered a valid form of community. This probably sounds cynical, and in a way it is. But if you think about it, the fact that lots of people have nothing better to do with their “free” time than to stand around in mostly empty white rooms, rooms that make a huge amount of money for other people, is a good reason to destroy pretty much everything.

Hatred of art, in the best and truest sense, has always really been disappointment that art can’t keep its own promises. The German philosopher Theodor Adorno once said: “The bourgeois want art voluptuous and life ascetic; the reverse would be better.:” Hatred of art isn’t hatred of beauty. In fact it’s closer to the opposite. It’s hatred of capitalism for trying to make us accept the fact that we can only find beauty in art. Or in some other commodity, or some commodified experience. (On Instagram everyone lives in paradise.) Of course it’s also hatred of the people who buy and sell and talk about art, because they’re mostly rich assholes. Nothing mysterious about that. For academics, though, it’s a lot easier to come up with elaborate theories about iconoclasm than it is to admit that iconoclasm is usually quite easy to explain.

Hatred of art, or at least this kind of it, has nothing to do with hatred of pleasure. Or even hatred of artworks, exactly. You can enjoy looking at art at the same time as you hate the art world and its institutions, in the same way you can shop at a store in the daytime and then loot it at night, if you get the chance. Communism means nice shit for everybody, as some other people have pointed out.[17] You can even make your own art if you want to. That’s fine. You can also be a revolutionary — better still. (Much better.) But don’t try to do your revolution through your art. That’s not how it works. If you feel the need to argue against this more or less self-evident point, there’s a good chance that you’re an art world asshole.

There are few things more depressing than the idea that art is the last zone of freedom in a capitalist world. If this were true, it would be yet another reason to destroy everything. (Don’t worry, we’re not running out of reasons.) But it’s not true, anyway. The art world is part of capitalism, just like everything else, which means that it’s built on a set of antagonisms. Class antagonisms, racial antagonisms, antagonisms around sexuality and gender. Of course this isn’t any secret. The problem with a lot of art world people, though — aside from the other, obvious problems — is that they want their participation in the art world to function as a complete package. In other words you can get your aesthetics, your ethics, and your politics in the same place, by doing the same stuff. Your art is your resistance, or your academic research is your resistance, or whatever. Conveniently enough, you can sell art, and you can also sell your labor as a radical academic. Maybe not for much, but somebody has to do it, right? Walk into any gallery these days and there’s a good chance the art will be “political.” You have to wonder exactly when the market is going to peak.

The package deal only works so well because the art world absorbs and mediates conflict in order to fuel its own reproduction. Where else would constant scandals over racist behavior turn out to be good for business, for example? An angel gets its wings every time some art world drone writes a think-piece about the latest racist shit in the latest biennial. Or rather, somebody or other gets to accumulate a little more (political, academic, aesthetic) cred. What this means, perversely enough, is that nearly everyone in the art world has a vested interest in yet more racist shit happening in the future. Otherwise there wouldn’t be anything to talk about.

Buying into the “complete package’ means that when you do your politics, you do it through and in the art world. You want to make the art world a better place, so that everybody gets a seat at the table. You make sure that museum collections, biennials, and gallery rosters have the right demographics (they never do and probably never will). You make sure that everybody knows that you do not like Donald Trump, nope, not one bit! Or else, your activism boils down to mobilizing art for some other political purpose, as a tool or a weapon. That’s usually even worse. (Did you hear about the Art Strike earlier this year? I’m guessing either you didn’t or you already forgot.)

Unless you’re extremely edgy, art activism doesn’t mean questioning whether there should be museums or biennials at all. The tendency to circle the wagons (the settler-colonialist metaphor isn’t totally accidental) has become much worse since Trump’s election, which had the effect of resurrecting a bunch of liberal-humanist cliches about the goodness of art that seemed like they’d been deconstructed out of existence decades ago. Whose team do you want to be on, after all: the nice, progressive, intelligent, well-dressed art people, or the right-wing philistines? The fact that the alternative is false, that other options exist, doesn’t make it less attractive. The art world is so used to being on the right side that it’s almost impossible for them to grasp that maybe it isn’t.

In LA, right now, we’ve had the pleasure of witnessing some of the art world’s contradictions unravel in real time. Militants in Boyle Heights and elsewhere have been very good at explaining what they’re doing and why, so I won’t even try to summarize the issues at stake. Instead, I recommend that you just read the statements from the involved groups, such as Defend Boyle Heights, Boyle Heights Alianza Anti Artwashing y Desplazamiento / Boyle Heights Alliance Against Artwashing and Displacement (BHAAAD], Union de Vecinos, the Los Angeles Tenants Union, and Ultra-Red. Some of the press coverage has been decent, too. (That being said, let me put in an extra special fuck you to LA Times reporter Ruben Vives for threatening to write a negative story if he wasn’t given an interview with a member of this coalition.)

In general terms, the conflict has to do with art’s complicity in the process that we call gentrification — a term that gets thrown around a bit carelessly, it’s true. Often, saying “gentrification is a way to avoid saying “capitalismClowning white hipsters is cool (also — they aren’t always white, or hip), but it shouldn’t distract from the fact that the bigger enemy is the real estate industry, not to mention employers who don’t pay workers enough to make rent. Some extremely violent forms of gentrification won’t necessarily look like the stereotypical “artists with fixies and cold brew moving into the hood narrative. What if we talked about new Chinese money pushing out poorer people of Asian descent in the San Gabriel Valley at the same time as we talk about Boyle Heights, for example? In economic terms the phenomenon might not be that different. There’s a danger of reinforcing existing forms of oppression and exploitation in the name of a preexisting community that supposedly overrides class divisions. That said, gentrification often does look like artists with fixies and cold brew moving into the hood, which is why these events east of the LA River have a meaning that goes far beyond the local context.

What is important about the struggle in Boyle Heights, and what makes it different from any other anti-gentrification conflict I know of, is that it’s developed into a direct confrontation between the “radical” art world and a local opposition that won’t back down, even when offered the chance for dialog. This is how you win. For example: a huge victory for the anti-gentrification campaign was the closure of the gallery PSSST in February of this year. Representatives of PSSST described their project as queer, feminist, politically engaged, and largely POC. All of which are perfectly good things in themselves, of course. A space for queer, feminist, politically engaged POC artists and their friends only becomes a problem when it contributes to a colonial, gentrifying dynamic. Which will inevitably happen as soon as well-connected art world people move into a historically working class neighborhood, regardless of their color or credentials.

This isn’t a matter of intentions or consciousness. No doubt PSSST thought they were doing good. It’s a matter of economics — in other words, stuff that happens whether you want it to or not, because there’s money to be made. Real estate developers don’t give a shit about your MFA in social practice art. PSSST never understood this. People in Boyle Heights did. PSSST was all about “dialog.” So is every gentrifier. Refusing dialog was the best (in fact the only) strategic decision the neighborhood’s defenders could have made. There’s no such thing as dialog when one side is pushing you out of your home. The fact that groups like Defend Boyle Heights have been so willing to engage with their enemies is the shocking thing, not their supposedly aggressive tactics. These tactics could be generalized. In fact in some places militant resistance to gentrification goes back decades, which is why cities like Berlin, for example, are so much more livable and fun than otherwise similar areas. Resistance won’t stop real estate from destroying livable communities — nothing except the end of capitalism will do that — but it can slow the process down and make life better for a lot of people.

The Boyle Heights conflict is racialized. Obviously. “Fuck White Art” is an excellent slogan. However, the adjective “White” is unnecessary, for reasons that I hope are clear by now. But then again, it is necessary, too, a bit in the way it’s necessary to say “Black Lives Matter’ instead of “All Lives Matter.” In effect, the slogan points out that the default setting for all art is “white art..’’This isn’t to say that there aren’t any non-white artists, or that their work is somehow marginal or inauthentic. Rather, it’s to point out that the art world as such, which really means the art industry, is fundamentally connected to capitalism, which is white supremacist even when there happen to be non-white people running things. Real estate works by fine-tuning the racial composition of neighborhoods so that it’s possible to sell property to more “desirable” (wealthier) buyers, who happen to be white people most of the time, coincidentally or not. Galleries, as well as fancy cafes, record stores, etc., are the smart bombs of gentrification. Land one in just the right place and you can take out the whole barrio. It was perfectly logical when another Boyle Heights gallery, Museum As Retail Space, called the cops on a picket line at one of their openings.

Of course smart gentrifiers prefer to avoid calling in (uniformed) pigs, if they can. Nothing works better than getting a few “diverse art spaces” to help out with your development scheme. That’s pretty much expected now. And it probably would have worked in the case of PSSST if nobody in Boyle Heights had tried those supposedly alienating tactics.

After these events it almost seems unnecessary to present a critique of the non-white artist as representative of something called “the community!’ (What community? Whose community? Is your landlord part of your community? How about your boss?) PSSST did a program focused on Latinx party crews in the 90s. It didn’t save them. It just pointed out how the phenomenon that some people have started calling gentefication — gentrification with a brown face — can be just as much bullshit as the idea that galleries “enrich” the neighborhood (as if Boyle Heights doesn’t have any culture of its own). Instead of trying to say something new about the topic I’ll just recommend this short text, which is already a classic:

The Poverty of Chicano Artists by El Chavo[18]

The one thing that has possibly changed since those words were written over 20 years ago is that the art scene, in its role as advance scout for capitalist development, has become much better at providing an apparent space for disagreement and even resistance — as long as nothing goes beyond empty talk.

The way PSSST operated, the way places like 356 Mission still operate, is through a technique that you could name “The Conversation.” The ideology of The Conversation works by taking a conflict that’s pretty clear from the start and then insisting that there’s more to talk about. The Conversation is always “more productive1 when the people getting fucked over avoid actually doing anything about it. The Conversation feeds on panel discussions. Often, The Conversation takes its cue from somebody or some group of people who have the right credentials to represent The Community, or who happen to be “activists.” (They hate Trump! Don’t you hate Trump, too?) Usually these activists have a long record of doing lefty stuff. They never understand that the left is the enemy, too.

There is no purer expression of The Conversation than members of the Artists’ Political Action Network (a post-election group of lefty artists) crossing a picket line to hold a meeting at a Boyle Heights gallery, then sending a letter that reads: “In deciding to stage the event at 356 Mission, we hoped that, rather than ignoring or attempting to avoid the conflicts in the area, the choice of location would create an opportunity for engagement and dialogue.” Funny logic: it works for every invasion. I bet the Aztecs loved it when Cortes gave them such a great opportunity for engagement and dialogue.

Here’s a more abstract way to express what I’ve been saying:

There is no such thing as a public dialog and hence art does not contribute to it. There is rather an antagonism between those who would like to continue pretending that such a dialog exists and those who want to demolish that pretense — not in theory, but in practice. (Leonard Cohen understood this, or at least he came up with a good phrase: “ There is a war between the ones who say there is a war/And the ones who say there isn’t.”) The antagonism cuts across race, class, and gender, although it’s certainly weighted. Those who have nothing to lose but their chains, or their abjection, or their social death, obviously have greater clarity about it. But it might be that the edge of the antagonism runs not so much between those who are comfortable in their fiction versus those who have no such luxury, but rather between those who might, in however precarious a way, benefit exactly from the boundary’s mediation, and those who have no interest in anything of the sort: between those who might profit from abjection, exactly by claiming to represent it, and those from whom this profit is made.

This distinction becomes the stuff out of which careers are built. It turns out that the maintenance of aesthetic appearances (I’m thinking of the German word Schein, which also means “illusion”) is one of the more convenient ways of putting the abject into circulation. Convenient, but not necessarily final. Not decisive. Much less so, anyway, than other forms of Schein that are less recognizable as such — for example race, which is an abstraction infinitely more violent than either the zombie formalism everyone in the art world was talking about a few years ago, or zombie protest. Art attracts conflict in part because the stakes are so low, because the battles are so purely spectacular, even as art also serves an absolutely real function in preserving the status quo. Antagonisms play out in art when they can’t (yet) be resolved in the rest of the world. The shittiness of the present moment is how impossible it seems to advance from the front lines to the citadels. Art tends to function as a border guard, here, asking for papers that reduce every real conflict into a problem of checking off the right boxes, which these days are usually a set of commodified forms of identity. Can you sell your abjection? Yes. Of course. You can also sell your politics. Your “resistance.” At this exact moment it’s probably the smartest thing you can do.

The worst participants in recent art world debates, hollow as these debates have been, are those who presume to understand everything best. Which in practice often means confessing your perplexity, but doing so as a technique, a move on the chessboard, a way to strengthen your own authority (not by actually knowing anything, perhaps, but by at least asserting your right to weigh in — your right to join the dialog). When in fact it’s the bleeding suture between one world and its negation that art world bureaucrats always try to sew up. They have their mission. The rest of us need sharper scalpels.

On the Poverty of Chicanx Artists

by El Chavo, a friend of the project

If the artist is not the most hated member of the Chicanx community it is certain that a very healthy disgust towards the artist is felt by many in the barrio. In the artists attempt to express themselves, speak for La Raza, or to raise their consciousness, they come short of the mark. The inherent poverty of the art scene is its inability to understand and change society, its refusal to see itself as a market place for one more commodity. This is what we detest. From cholos to viejitas, to mocosos and their relatives, everyone hates the false notion of the artist as a representative of our needs or as a spokesperson for change.

All the novelty rappers, uninspired singers, hack writers, crayola painters, pretentious poets, and the hardly-funny cartoonists and comedians that make up the Chicano And Chicana Artist (CACA) cultural scene imagine themselves to be that which they are not: for some reason they believe that they are a challenge or an opposition to the dominant culture. The truth is that they are merely another aspect of the same society or as some would accurately call it, they are part of the spectacle of negation. When a person’s life lacks in meaning, pleasure, and they have no control over how to run their own lives, they look outside of themselves for salvation. The artist finds his calling in “self-expression”, creating art pieces in which she can live out a dull reflection of what has not been possible in real life. That’s not beautiful; it’s pathetic.

In a world that runs on a heavy dose of alienation the reverence for art serves only to strengthen that society. The emergence of the Chicano Art scene is a movement of the forgotten commodity back into the flow of the marketplace; the desire to belong within the world of separation; to be bought and sold like everyone else. The artist has no vision. She fails to see what is truly beautiful, just as they failed to see the poetry in the streets during the rioting in ‘92. Can their little doodles ever top the critique of daily life that the looters offered in their festive events? Of course not.

So what happens to La Raza once the artist sells his piece, gets her grant, or has that special gallery showing? Nothing. All the people that you aim to represent on your canvas or in your poems, we still have to exist in the same ghettoes, we still have to work in the same stupid jobs, or wait in the same welfare lines. We will never see you there. You will never mean anything to us.

We laugh at you and the society you reinforce.

Give it up.

You’re headed nowhere.

This House is a Fence

The wood-slate fence has jumped from being a simple signifier of “this house has been flipped” to becoming a part of the construction of the house itself. The above is a photo of an actual house in Boyle Heights being offered for rent at $2995 for 3 bedrooms.

Whereas previously the function of this fence was to shield its new, well-heeled owners from the insufficiently gentrified neighborhood, these wood-slates now are free to signify “flipped” no matter where they are placed on the home. The now defunct website, LAist quotes Dave Bantz an architecutral designer when they say “So, in that respect, the slat is a wordless billboard with the subtext, ‘this neighborhood has potential. But it’s still a place where you’re going to want a sense of protection from the street.’” Just as the pristine, white-walled cafes modeled after an Apple store (and filled with as many if not more Macbooks), that more and more riddle Los Angeles, once merely had recourse to its exorbitantly priced coffee to keep the the proletarian locals out, a new cafe in Boyle Heights is now a selling point for the flipped house pictured above.

Before gentrification in the L.A. East-side, fences served a much more utilitarian purpose: to keep stray dogs out of your yard or a way to keep solicitors at bay. Chainlink fences predominate but there are also the wrought iron fences for those homes with a bit more money. There was no real attempt to completely shield one’s home from view. One’s gaze could easily pass through either of these type of fences and see your neighbor on the porch or tending to their garden.

A walk through the heavily gentrified areas of the L.A. Eastside has houses distintinctly separated from each other with those wood-slate fences where you would not be able to see those who live inside, sometimes completely obscuring the house. All this speaking to the fears of the new arrivals who love the relatively low prices but do not love the neighborhood. One Boyle Heights affordable advocate caught heat two years ago for posting a photo of a home in Boyle Heights with a wood-slate fence. People found out where the house was and the owner was livid. He was “45-year-old, white ‘non-hipster’ who purchased the house last year in Boyle Heights because ‘it’s the one place in LA where I could (barely) afford to buy a home.’” Interestingly this home owner thinks that being a non-hipster means that he could not possibly be contributing to gentrification in Boyle Heights: something akin to how middle-class Latinxs returning to Boyle Heights think of their “development” of the neighborhood as a neutral/positive gente-fication and not gentrification. In wealthier areas of Los Angeles you see homes without fences and with uncurtained, unshuttered windows: the interior on display to any passerbys.