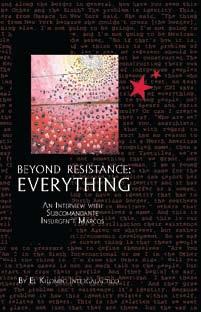

El Kilombo Intergaláctico

Beyond Resistance: Everything

An Interview with Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos

INTRODUCTION. ZAPATISMO: A BRIEF MANUAL ON HOW TO CHANGE THE WORLD TODAY

3. The Methodology of the Inverted Periscope

INTERVIEW With Subcomandante Marcos

1. THE OTHER CAMPAIGN: A DIAGNOSTIC

3. WHEN THERE IS NO REFERENT, CREATE!

5. THE MOVEMENT OF MOVEMENTS AND THE GENERATION OF ‘94

6. BEYOND RESISTANCE? EVERYTHING.

7. CONSTRUCTING COMMUNITY IN LIBERATED TERRITORY

9. ALL EMPIRES SEEM INVINCIBLE...

Appendix: SIXTH DECLARATION OF THE LACANDON JUNGLE

FOREWORD

This interview was created and conducted by El Kilombo Intergaláctico. We are a people of color collective made up of students, migrants, and other community members in Durham, North Carolina. Our project is to create a space to strengthen our collective political struggles while simultaneously connecting these struggles with the larger global anti-capitalist movement.

When we designed this interview in our community assembly, we wanted to bring out several thematic layers. We wanted to talk about issues unique to the US: a particular set of race relations and our own perspective on the battle between capital and color; the historic and contemporary predominance of migrant, displaced, and “in-flight” populations and the kind of communities created by a nation of “nationless” people; and the reality of being simultaneously part of the global poor in a capital-rich country and part of the great richness and resistance which exists “below” in the global movement for a different world. We wanted to talk about issues that bridge the North American continent: the real danger and simulated reality of the border, the migrant labor that now supports two economies, and the communities all over the continent that have never recognized nation-state boundaries as legitimate. And finally we wanted to situate our discussion in issues now fully and undeniably global: how to build effective anti-capitalist movements, construct new social relations, and create real alternatives for the organization of society in the context of a globalized capitalist economy.

We want to provide a brief explanation of the perspective and experience that frames our conversation with the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN). El Kilombo came together after the historic anti-war movement which preceded the US invasion of Iraq, and in the midst of a floundering and disoriented US Left and a disenfran-chised population. As students, migrants, and other members of the community we realized that we shared common problems—insecure working conditions, the expropriation of our land and resources, a paralyzing isolation in the maze of attending to bills, health, housing, education, debt, and documentation—as well as common enemies: a corporatized university system complicit with powerful agents of capital and corrupt politician-managers united in a shared goal of patent and profit control over the wealth of knowledge, labor, and life we provide in common.

We started by opening a social center, a space for encounter, where people could come together, not only to find things and services they need, but to meet each other and to talk about creating things they desire. We started English and Spanish language classes, Capoeira classes, computer classes, and homework help for kids. We designed a collectively-taught political seminar for ourselves and the community, and began mapping the problems and resources of our city. The participants in our programs, our neighbors, developed into a collective decision-making body, an assembly, which in turn decided what else was needed. Together we are all working on a health commission to set up free medical consultations, an organic garden to provide free food distribution, and a housing collective to lower costs and address security concerns in our neighborhood.

We were created, as a collective, in the “todo para todos” of the Zapatistas, in the “que se vayan todos” of the piqueteros in Argentina, in the dignity and self-respect of movements in the United States like the Black Panthers and the Young Lords, and in the courage and commitment of all of the quilombos—the indigenous, African, multi- and inter-racial peoples all over the world that built autonomous communities to break the relations of domination.

When the Sixth Declaration of the Lacandón Jungle came out, we sent a representative from our group to accompany the first journey of the Other Campaign, the visit of the Zapatista Sixth Commission to every state of the Mexican Republic. We did this in support of the Other Campaign, but also to create a bridge between our movements and as a learning experience for ourselves. As a member of our assembly said of the Zapatista movement, “They have nothing and they have given us everything.” Solidarity is insufficient. The only thing worthy of our dignity and of theirs is a movement here as fierce and formidable and transformative as what the Zapatistas have created there.

The Introduction that follows here, “Zapatismo: A Brief Manual on How to Change the World Today,” is a synthesis of our experience of Zapatismo over the last decade and what we believe to be its lessons and insights for a world in the throes of destruction and on the edge of powerful possibilities.

Our interview with Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos was held shortly after his return to Chiapas following the first full journey of the Other Campaign through Mexico. Finally, with the hopes of increasing circulation of the Sixth Declaration of the Lacandón Jungle, we have included it as an appendix, in its entirety.

From “El Hoyo,” Durham NC, our hole in the ground, below and to the left,

—El Kilombo Intergaláctico

November 2007

INTRODUCTION. ZAPATISMO: A BRIEF MANUAL ON HOW TO CHANGE THE WORLD TODAY

By El Kilombo Intergaláctico

The following lines are the product of intense collective discussions that took place within what is today El Kilombo Intergaláctico during much of 2003 and 2004. These discussions occurred during the advent of the Iraq War and our efforts (though ultimately ineffective) to stop it. During those months it became very clear to us that the Left in the United States was at a crossroads, and much of what we had participated in under the banner of “activism” no longer provided an adequate response to our current conditions.

In our efforts to forge a new path, we found that an old friend—the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional (Zapatista Army of National Liberation, EZLN)—was already taking enormous strides to move toward a politics adequate to our time, and that it was thus necessary to attempt an evaluation of Zapatismo that would in turn be adequate to the real ‘event’ of their appearance. That is, despite the fresh air that the Zapatista uprising had blown into the US political scene since 1994, we began to feel that even the inspiration of Zapatismo had been quickly contained through its insertion into a well-worn and untenable narrative: Zapatismo was another of many faceless and indifferent “third world” movements that demanded and deserved solidarity from leftists in the “global north.” From our position as an organization composed in large part by people of color in the United States, we viewed this focus on “solidarity” as the foreign policy equivalent of “white guilt,” quite distinct from any authentic impulse toward, or recognition of, the necessity for radical social change. The notion of “solidarity” that still pervades much of the Left in the U.S. has continually served an intensely conservative political agenda that dresses itself in the radical rhetoric of the latest rebellion in the “darker nations” while carefully maintaining political action at a distance from our own daily lives, thus producing a political subject (the solidarity provider) that more closely resembles a spectator or voyeur (to the suffering of others) than a participant or active agent, while simultaneously working to reduce the solidarity recipi-ent to a mere object (of our pity and mismatched socks). At both ends of this relationship, the process of solidarity ensures that subjects and political action never meet; in this way it serves to make change an a priori impossibility. In other words, this practice of solidarity urges us to participate in its perverse logic by accepting the narrative that power tells us about itself: that those who could make change don’t need it and that those who need change can’t make it. To the extent that human solidarity has a future, this logic and practice do not!

For us, Zapatismo was (and continues to be) unique exactly because it has provided us with the elements to shatter this tired schema. It has inspired in us the ability, and impressed upon us the necessity, of always viewing ourselves as dignified political subjects with desires, needs, and projects worthy of struggle. With the publication of The Sixth Declaration of the Lacandón Jungle in June of 2005, the Zapatistas have made it even clearer that we must move beyond appeals to this stunted form of solidarity, and they present us with a far more difficult challenge: that wherever in the world we may be located, we must become “companer@s” (neither followers nor leaders) in a truly global struggle to change the world. As a direct response to this call, this analysis is our attempt to read Zapatismo as providing us with the rough draft of a manual for contemporary political action that eventually must be written by us all.

1. Why Fight

On January 1st of 1994, the very day that the North American Free Trade Agreement was to go into effect, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN), an army composed in its grand majority by members of Chiapas’ six largest indigenous groups, declared war on the Mexican army and its then commander-in-chief, Carlos Salinas de Gortari, who, according to the EZLN, was waging an undeclared genocidal war against the peoples of Mexico. In response, the EZLN proposed that fellow Mexicans join them in a struggle for land, housing, food, health, education, work, independence, democracy, justice and peace.[1] During a twelve day military offensive, Zapatista soldiers, many of them armed only with old rifles and wooden sticks, occupied seven municipalities in the state of Chiapas (Altamirano, Las Margaritas, San Cristóbal, Ocosingo, Chanal, Huixtan, and Oxchuc). Since these first days, there have been hundreds of pages written claiming that the EZLN is a movement for the rights of indigenous Mexicans, for the recuperation of rural lands, for constitutional reform, and for the end of NAFTA. We would like to insist that despite the fact that all of these claims are absolutely true, none of them are sufficient to understand the appearance and resonance of the EZLN. According to Subcomandante Marcos (the delegated spokesperson of the EZLN),[2] the Zapatistas wanted something far more naïve and straightforward than the innumerable goals that were attributed to them. In his own words, they wanted to “change the world.”[3] We believe that this must be our first and primary premise if we are to understand Zapatismo: that the EZLN is a movement to change the world, and that those who have been attracted to them, including those who might read these pages, sympathize with the EZLN because they too believe, like the Zapatistas, that, “another world” is both possible and necessary.[4]

2. A Truly Total War

In presenting this premise, the first and most obvious question that arises is, what is wrong with the world today that the EZLN and others might want to change it? According to the Zapatistas, our current global condition is characterized by the fact that today humanity suffers the consequences of the world’s first truly TOTAL war, what the EZLN has aptly named the Fourth World War.[5] The nature of this war is best understood by contrasting those World Wars that have preceded it. Taking for granted that the nature of the First and Second World Wars are well known (i.e. Allied Powers vs. Central Powers and Allied Powers vs. Axis Powers), we will turn to the immediately preceding world war—though it is rarely understood as such—the Third World War. The Third World War (or the Cold War) was characterized by the fact that nation-states faced down other nation-states (most typically the United States and its allies in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and its allies in the Warsaw Pact) for the control of discrete territories around the globe (most specifically Central Africa, Southeast Asia, and Central America). At the height of this conflict, the guerrilla style tactics adopted by each side made it appear, as General Nguyen Van Giap noted, that “the front today is everywhere.”[6] And yet, most anyone would agree that like the previous World Wars, the Third World War ended with the conquest of specific territories and the ultimate defeat of an externally identifiable enemy (the U.S.S.R.).

In contrast, what the EZLN has identified as the Fourth World War is a war between what the EZLN has termed the “Empire of Money”[7] and humanity. The main objectives of this war are: first, the capture of territory and labor for the expansion and construction of new markets; second, the extortion of profit; and third, the globalization of exploitation. Significantly then, for the first time, we are in the midst of a World War that is not fought between nations or even between a nation and an externally identifiable enemy. It is instead a war for the imposition of a logic and a practice, the logic and practice of capital, and therefore everything that is human and opposes capital is the enemy; we are all at all times potentially the enemy,[8] thus requiring an omniscient and omnipotent social policing. As the EZLN explains, this qualifies the Fourth World War as the first truly TOTAL war because, unlike even the Third World War, this is not a war on all fronts; it is the first world war with NO front.[9]

A. The Two Faces of War

The war with no front has two faces. The first is destruction. Any coherent logic and practice that allows for the organization of life outside of capital, anything that allows us to identify ourselves as existing independent of capital, must be destroyed or, what may be the same thing, reduced to the quantifiable exchangeability of the world market. Cultures, languages, histories, memories, ideas, and dreams all must undergo this process. In this regard, struggles for control over the production and subordination of racialized and gendered identities becomes a central battlefield. All the colors of the people of the earth face off with the insipid color of money. For the capitalist market, the ultimate goal is to make the entire world a desert of indifference populated only by equally indifferent and exchangeable consumers and producers. As a direct consequence, the “Empire of Money” has turned much of its attention to destroying the material basis for the existence of the nation-state, as it was through this institution that for the last century humanity was able to, even if only marginally, keep the forces of money at bay.

The second face is reorganization. Once the “Empire of Money” has sufficiently weakened the nation-state, it then reinvigorates this same institution for its own ends through the introduction of schemes intended to benefit the structure of the market itself, specifically the advent of privatization as government policy. This allows for the increasing intervention of the state with the end of minimizing its redistributive or social capacity and using it as a mechanism for the insistent imposition of the market. This imposition is so expansive that literally everything becomes a business opportunity, a site for speculation, or a marketable moment. What was previously a site for community strength (i.e. a mural) is today simply a wall for corporate advertisement; what was previously knowledge passed down to be shared socially is today the site for the latest pharmaceutical patent; what yesterday was free and abundant today is bottled and sold.

Without any social safety net and bombarded with images of an ever-present enemy, the logic of policing extends to that figure previously known as “the citizen” of the former nation-state. This figure is today reconstituted as an atomistic self-policing subject, “a competitor” who enters (i.e. misses) all encounters believing that “the other,” that which is not me, exists only to defeat me, or be defeated by me. A total war indeed. Today there is simply no quiet corner to rest and catch one’s breath.

B. Consequences

In the eyes of the EZLN, the Fourth World War has had three major society-wide consequences, each played out at varying sites.

First, States: the State in the Empire of Money, as mentioned above, is reorganized. It is now the “downsized” state where any semblance of collective welfare is eliminated and replaced with the logic of individual safety, with the most repressive apparatuses of the State, the police and the Army, unleashed to enforce this logic. This state is in no way smaller in the daily lives of its subjects; rather, it is guaranteed that the power of this institution (collective spend-ing) is directed purely toward new armaments and the increasing presence of the police in daily life.

Second, Armies: the Army in previous eras was assumed to exist for the protection of a national population from foreign invasion. Today, in the structural absence of such a threat, the army is redirected to respond with violence to manage (and yet never solve) a series of never-ending local conflicts (Atenco, Oaxaca, New Orleans) that potentially threaten the overall stability of international markets. In other words, as the EZLN points out, these armies can no longer be considered “national” in any meaningful sense; they are instead various precinct divisions of a global police force under the direction of the “Empire of Money.”

Third, Politics: the politics of the politicians (i.e. the actions of the legislative, executive, and judiciary branch-es) has been completely eliminated as a site for public deliberation, or for the construction of the previously existing nation-state. The politics of the politicians has been redirected and its new function is that of the implementation and administration of the local influence of transnational corporations. What was previously national politics has been replaced with what the EZLN refers to as “megapolitics”—the readjustment of local policy to global financial interests. Thus the sites that once actually mediated among local actors are now additionally charged with the mission of creating the image that such mediation continues to take place. It is best to be careful then and not believe that the politicians and their parties (be they right wing or “progressive”) are of no use; rather, it is important to note that today their very purpose is the outright simulation of social dialogue (that is, they are of no use TO US!).

C. Insights

If this global situation is in fact a war—and the high level of social devastation as well as the number of dead and imprisoned seem to confirm this—then the parameters of this new war detailed by the EZLN force us to reassess the effectiveness of our customary strategies and tactics so as to determine if they are in fact adequate to our current situation. In this regard, the EZLN’s insights obligate us to reevaluate our conceptions of both oppression and politics.

First, the current situation forces us to reconceptualize how inequality functions. For much of the 20th century, progressive social movements had become accustomed to thinking of inequality as measured by exclusions and inclusions. For example, many oppressed minorities spent an immense amount of social energy struggling for their inclusion in national projects, or, similarly, countries on the ‘periphery’ of the world economy oriented much of their energy toward inclusion in projects for ‘international development.’ But today, the “Empire of Money” has made this play of insides and outsides increasingly irrelevant as a social indicator of inequality. As if in some perverse fulfill-ment of the desires of previous social movements, today we are all included in the nightmare of the global market. Or, as Subcomandante Marcos’ fictional sidekick Durito (a comical beetle) would have it, oppression today—and since at least 1989—is no longer maintained by the famous vertical walls that were meant to keep the masses of citizens inside safe from the innumerable enemies outside (or vice-versa).[10] That wall was torn down forever and has today been rebuilt horizontally across the entire face of the earth. This new wall cares little where in the (geographical) world you might be; it is instead there to keep the billions of exploited below the wall from the small handful of exploiters who built it. In short, this new wall is there to separate the “Empire of Money” from those who would threaten it—that is, from all of us. Given this situation, to demand “inclusion” is to desire to stand above the wall; to demand change is to desire a collective blow for this wall to crumble.

Second, we must reassess the grounds for potential political change. If we are to take the Zapatistas seriously and conclude that the politics of the politicians is a sphere that functions through the simulation of public opinion—through polls and the circulation of sound bites and images—to administer the interests of transnational capital, it would be near suicide to continue to do politics as a competition for influence within that sphere. No matter how well-intentioned or “progressive” a given party or platform may be, the proximity of politicians to the vertical structure and logic of the State today assures only their complete functionality to the larger system of inequalities. In addition, we must remind ourselves that these politicians are not there to simulate for just any power; they are there to simulate social peace for a global power that is today greater than the collective power of any particular state. Thus, any opposition that limits itself to the level of a single state, no matter how powerful, may be futile.

Yet, at the same time that these futilities surface, other strategies and tactics simultaneously emerge within this new situation, strategies that rise to the challenge of the contemporary impasse faced by our previous social visions. Consider for example the tremendous inspiration provided by the following lines written by Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos; what appears at first as poetic license should be read more carefully as the outline of a brilliant strategy for our times:

“The social ship is adrift, and the problem is not that we lack a captain. It so happens that the rudder itself has been stolen, and it is not going to turn up anywhere. There are those who are devoted to imagining that the rudder still exists and they fight for its possession. There are those who are seeking the rudder, certain that it must have been left somewhere. And there are those who make of an island, not a refuge for self-satisfaction but a ship for finding another island and another and another…”[11]

3. The Methodology of the Inverted Periscope

The Fourth World War continues unabated and the result has been a near total devastation of the earth and the misery of the grand majority of its inhabitants. Given this situation and the sense of despair it brings, it would be easy to lose a sense of purpose, to raise our hands in defeat and utter those words that have been drilled into us for the past thirty years: “there is in fact no alternative.” Despite the new contours of the Fourth World War and the sense of social dizziness that it has created, it is important for us to realize that this war shares one fundamental constant with all other wars in the modern era: it has been foisted upon us in order to maintain a division (an inequality) between those who rule and those who are ruled. Since the attempted conquest of the “New World” and the consequent establishment of the modern state-form, we have so internalized this division that it seems nearly impossible to imagine, let alone act on, any social organization without it. It is this very act of radical practice and imagination that the Zapatistas believe is necessary to fight back in the era of total war.

But how might this alternative take shape? In order to begin to address this question, the Zapatistas implore us to relieve ourselves of the positions of “observers” who insist on their own neutrality and distance; this position may be adequate for the microscope-wielding academic or the “precision-guided” T.V. audience of the latest bombings over Baghdad, but they are completely insufficient for those who are seeking change. The Zapatistas insist we throw away our microscopes and our televisions, and instead they demand that we equip our “ships” with an “inverted periscope.”[12]

According to what the Zapatistas have stated, one can never ascertain a belief in or vision of the future by looking at a situation from the position of “neutrality” provided for you by the existing relations of power. These methods will only allow you to see what already is, what the balance of the relations of forces are in your field of inquiry. In other words, such methods allow you to see that field only from the perspective of those who rule at any given moment. In contrast, if one learns to harness the power of the periscope not by honing in on what is happening “above” in the halls of the self-important, but by placing it deep below the earth, below even the very bottom of society, one finds that there are struggles and memories of struggles that allow us to identify not “what is” but more importantly “what will be.” By harnessing the transformative capacity of social movement, as well as the memories of past struggles that drive it, the Zapatistas are able to identify the future and act on it today. It is a paradoxical temporal insight that was perhaps best summarized by “El Clandestino” himself, Manu Chao, when he proclaimed that, “the future happened a long time ago!”[13]

Given this insight afforded by adopting the methodology of the inverted periscope, we are able to shatter the mirror of power,[14] to show that power does not belong to those who rule. Instead, we see that there are two completely different and opposed forms of power in any society: that which emerges from above and is exercised over people (Power with a capital “P”), and that which is born below and is able to act with and through people (power with a lower case “p”). One is set on maintaining that which is (Power), while the other is premised on transformation (power). These are not only not the same thing; they are (literally) worlds apart. According to the Zapatistas, once we have broken the mirror of Power by identifying an alternative source of social organization, we can then see it for what it is—a purely negative capacity to isolate us and make us believe that we are powerless. But once we have broken that mirror-spell, we can also see that power does not come from above, from those “in Power,” and therefore that it is possible to exercise power without taking it—that is, without simply changing places with those who rule. In this regard, it is important to quote in its entirety the famous Zapatista motto that has been circulated in abbreviated form among movements throughout the world: “What we seek, what we need and want is for all those people without a party or an organization to make agreements about what they don’t want and what they do want and organize themselves in order to achieve it (preferably through civil and peaceful means), not to take power, but to exercise it.”[15] Only now can we understand the full significance of this statement’s challenge.[16]

It is important to note how this insight sets the Zapatistas apart from much of the polemics that has dominated the Left, be it in “socialist” or “anarchist” camps, throughout the 20th century. Although each of these camps has within itself notable historical precedents that strongly resemble the insights of Zapatismo (the original Soviets of the Russian revolution and the anarchist collectives of the Spanish Civil War come most immediately to mind), we must be clear that on the level of theoretical frameworks and explicit aims, both of these traditions remain (perhaps despite themselves) entangled in the mirror of Power. That is, both are able to identify power only as that which comes from above (as Power), and define their varying positions accordingly. Socialists have thus most frequently defined their project as the organization of a social force that seeks to “take [P]ower.”[17] Anarchism, accepting the very same presupposition, can see itself acting in a purely negative fashion as that which searches to eliminate or disrupt Power—anarchist action as defenestration, throwing Power out the window.[18] Thus, for each, Power is a given and the only organizationally active agent. From this perspective, we can see that despite the fact that Zapatismo contains within itself elements of both of these traditions, it has been able to break with the mirror of Power. It reveals that Power is but one particular arrangement of social force, and that below that arrangement lies a second—that of power which is never a given but which must always be the project of daily construction.

In sum, according to the Zapatistas, through the construction of this second form of power it is possible to overcome the notion (and the practice which sustains it) that society is possible only through conquest, the idea that social organization necessitates the division between rulers and ruled. Through the empowerment of power, it is possible to organize a society of “mandar obedeciendo” (rule by obeying),[19] a society that would delegate particular functions while ensuring that those who are commissioned to enact them answer to the direct voice of the social body, and not vice-versa. In other words, our choices now exceed those previously present; we are not faced with the choice of a rule from above (we would call this Sovereignty), or no rule at all (the literal meaning of Anarchy). The Zapatistas force us to face the imminent reality that all can rule—democracy (as in “Democracy, Liberty, and Justice”).[20]

4. The Practice of Democracy

When democracy is wrenched from the clenched fist of idealism, and is instead understood as the cultiva-tion of habits and institutions necessary for a society to “mandar obedeciendo,” a whole new continent of revolutionary praxis opens before us. That is, having been able to identify the autonomous and antagonistic relation that “exercising power” (a conduct of power) has to “taking power” (a conduct of Power), the Zapatistas have been unique in their capacity to move beyond the street protest and rhetorical denunciation that have seemed to dominate much of the rest of the anti-globalization movement in recent years. In fact, it seems that in the same way that the Zapatistas were an inspiration for the recovery of the spirit of resistance that has characterized the movements of the past decade, their vision will continue to be a key inspiration as these same movements struggle with the necessity of moving “beyond resistance.”[21]

Below, we would like to outline the most notable and consistent practices that have allowed the Zapatistas to grow and become stronger while many of the movements that were born alongside them in this recent cycle of struggles have come and gone (while the pain and desires that gave rise to many of them remain intact). In enumer-ating a series of distinct Zapatista practices, we in no way intend to imply that any one of these practices is primary over any other, or that any of them in themselves is Zapatista democracy. To the contrary, as many others have noted, democracy is best understood through what physicists and systems theorists have called “reverse causality,” where cause and effect form a closed and retroactively nutrient circuit, making the question of a first or primary cause irrelevant. Instead, the practice of democracy in Zapatista territory tends to place its emphasis on the distinctions and discernments that allow for the composition or compilation of a number of habits, institutions, and results. In other words, Zapatista democracy is not any single habit, action, or institution (means), in which case it might be described as a verb; nor is it the result of any of these habits, actions, or institutions (ends), in which case it could be considered a noun. Rather, it is an ecology for the coupling of institutions, actions, and their results that allows for a continual feedback loop repeatedly opening and enriching both means and ends.[22] The practice of democracy in Zapatista territory is best understood as a noun-verb, a noun-verb that, despite its recent distance from the eye of the media, is far from exhausted. Among the most compelling components of this practice are:

1) Encounter.

The Zapatistas have used this practice in order to look beyond themselves and build an “archipelago of islands,” or a massive network of global resistance. According to the Zapatistas, the first such “encounter” that occurred was within the EZLN itself, and it took place between the guerrilla members of the Frente de Liberación Nacional (National Liberation Front) and the members of the indigenous communities of Chiapas. As the EZLN tells this history, it was here that the communities forced these guerrilla fighters to listen and dialogue, to, in effect, learn to encounter others even when the deafening noise of weapons and vanguardist ideals would have it otherwise. Thus, encounter is first and foremost an ethic, an ethic of opening oneself to others even, or perhaps especially, at the risk of losing oneself.

Although these lessons were painful for the guerrilla fighters of the EZLN and their community counterparts, they became deeply ingrained within the ethos of the EZLN, and they have led to the organization of encounters as a central practical activity between the EZLN and innumerable others. Even a rather incomplete selection of the encounters proposed and hosted by the Zapatistas in the last 13 years is overwhelming in its diversity and innovation. The First National Democratic Convention was held in August of 1994, the First Continental Encounter in April of 1996, and the First Intercontinental Encounter for Humanity and Against Neoliberalism, also known as the “Intergalactic,” in July of 1996, all attended by thousands of people flooding into Zapatista territory to meet not only the Zapatistas, but each other. Any surface investigation of these encounters will show that they were absolutely crucial to the formation of the alterglobalization movement and the subsequent events that were to take place in Seattle, Prague, and Genoa.

Then, in spectacular disregard for the containment the Mexican military claimed to have on Chiapas, the Zapatistas began to come out of their territory to create additional encounters with Mexican society: 1,111 civilian Zapatistas in September 1997 attended the founding of the National Indigenous Congress in Mexico City; 5,000 Zapatistas in March of 1999 hosted a national and international referendum on the EZLN’s demands; and in February of 2001, 24 Zapatista commanders took the issue of constitutional rights for indigenous people to Mexico City in “The March of the Color of the Earth.” Back in rebel territory, in July 2003, five “Caracoles” were inaugurated as bastions of Zapatista cultural resistance, portals from Zapatista territory to the world, and spaces of encounter for global resistance. With the release of the Sixth Declaration of the Lacandón Jungle in 2005, the Zapatistas proposed another series of encounters: the Other Campaign, which included the visit of an EZLN commission to every state of the Mexican Republic in 2006, and another Intergalactic. That Intergalactic is now pending, preceded by a series of “Encounters between Zapatista Peoples and Peoples of the World” in December 2006, July 2007, and December 2007, which has been specified as the first “Encounter Between Zapatista Women and Women of the World.” Yet, no matter how many encounters are actualized, the Zapatista ethic of encounter cannot be exhausted. Rather, as the Zapatistas insist on reminding us, any ethic of encounter worthy of the name must necessarily be based on the premise that “what is missing, is yet to come” ( falta lo que falta).

2) Assemble.

From the beginning of their movement, the Zapatistas’ bases of support have organized themselves into local assemblies. These assemblies are collective decision-making bodies that function not only to make consensus a reality but also to ensure the circulation and socialization of information that will make an informed decision possible. Regional groupings of community assemblies make up Zapatista Autonomous Municipalities, which in turn, and after years of silent and steady social construction, correspond to autonomous self-governing bodies called “Good Government Councils,” one in each of the five zones of Zapatista territory. The councils are made up of community members from each autonomous municipality who rotate in and out of the council positions, which are delegated by and accountable to the assemblies. The council term lengths vary by region but may range from a few weeks to a few months, with every position subject to immediate revocation by the assemblies if a delegate does not follow the community mandate. This system of assemblies and governing councils demonstrates that the only way to avoid the division of society into the oppressive dichotomy of rulers and ruled is to invent structures where all rule; everyone at some point governs, just as everyone after governing, returns to the cornfield or to the kitchen to continue the daily work of the community.[23]

3) Create.

Despite the near total hegemony that advertising and “art for art’s sake” has had on the notion of creativity, the Zapatistas remind us that creation is in no way related to the production of objects—be it for aesthetic enjoyment or otherwise. Creation does not (and must not) belong to an isolatable social sphere that stands above the collective, there to be mastered by the genius or the recluse. Rather, in the Zapatista model, creation is born of collective necessity; capitalism has imposed on us a life that is far from fulfilling, and in the face of this situation we have but one choice—to create our lives otherwise. To do so, we do not have to wait to “storm the winter palace” or for a new junta to declare “The Revolution.” We must gather the materials at hand today (including our periscopes, our “memories of tomorrow”), and build another world. What seems to come from this project is not “a thing” per se, but a process, a way of relating to all things (including each other). The “art” of Zapatismo has, as its producers and its product, a subjectivity capable of opening and relating to all types of others as subjects in their own right, leaving behind capital and its restriction of all relations to relations between objects.

With this understanding, the Zapatistas have created a series of autonomous institutions which function throughout their territory. There are autonomous primary schools in all five zones, and now autonomous “high schools” in two of them, already with several generations of graduates. All five regions also have basic health clinics that integrate western medicine with traditional healing and focus both on learning new medical technologies and recovering the knowledge, use, and supply, of herb- and plant-based medicines. Some zones have their own ambulances and minor surgery centers, and all are developing specially trained health promoters in women’s and reproductive health. The health systems focus on illness prevention as well as social health and nutritional information and practice, so that people not only learn to take care of themselves but begin to build—with the understanding that heath (physical, emotional, and mental) is a collective characteristic—the kind of community well-being they seek. A juridical system based in the Good Government Councils of each zone functions as a body to resolve local problems, investigate crimes and complaints, and hear and decide on disputes. The decisions made in the Councils focus on restorative justice, and their manner of hearing and resolving disputes has been so popular and successful that non-Zapatista communities often bring their cases to the Councils rather than to the municipal or state courts.

Other autonomous projects include a variety of cooperative projects on community, municipal, and zone-wide levels. These include collective warehouses for coffee and other crops that allow farmers to evade the “sell-low, buy-high” pattern forced on small and subsistence-level producers; transportation collectives that coordinate movement between municipalities and zones to facilitate trade, meetings, and encounters between the communities in resistance; and women’s cooperatives which provide an entire institutional phenomenon in themselves. The women’s cooperatives range from chicken coops to garden collectives to artisanship groups to supply stores, all of which are managed collectively. These provide not only new income and possibilities for autonomous sustenance, but also a collective space for women, which has long been scarce due to the incredibly heavy workload required for individual household maintenance. One other noteworthy autonomous activity is the creation of Radio Insurgente, Zapatista radio which transmits in multiple indigenous languages throughout the state, breaking through the mass media mo-nopoly on information and the government tactic of isolation.

4) Rebel.

A confrontation with the Empire of Money is not a goal, nor is it a desire; it is a reality, and it is necessary to find the tools most powerful to defend one’s constructive projects against repression. As the Zapatistas quickly realized, traditional armaments were a very poor weapon in this new war. They have silenced their “fire” and have instead insisted that today, “our word is our weapon.” Their word(s): Encounter, Assemble, Create. The question remains whether these weapons—the practices of Encounter, Assembly, and Creation—are powerful enough to ensure the protection of the Zapatista communities and the continued empowerment of their vision. We hope that the following pages will provide you with an opportunity to decide for yourself.

INTERVIEW With Subcomandante Marcos

By El Kilombo Intergaláctico

1. THE OTHER CAMPAIGN: A DIAGNOSTIC

After having spent all of 2006 traveling by land to visit the 32 states of the Mexican Republic, the EZLN said that they have found much more pain than what they had expected. Since the Sixth Declaration was written, how have the EZ’s ideas changed, in terms of what Mexico is, suffers, and could be?

Well to start with, before writing the Sixth, we did a kind of x-ray or study of the country. Not by reading books, but, like the intellectuals say, through fieldwork. So we sent a group of compañeros and compañeras to various parts of the country to see what the situation was like. After 2001, when the indigenous law was betrayed [by the National Congress], the question left pending was, what now? At that point, after so many years of efforts to establish a conversation with the political class, which failed, we were deciding to change interlocutors, and we had to answer the question, now who? With whom are we going to speak? Which is what I was asking you before we started: “Who am I talking to?” So we sent out these compañeros and compañeras, and we gave them the collective name, “Elias Contreras,” in honor of a support-base compañero who died around that time. They brought us this type of radiog-raphy that told us something about the subject of land, something about the subject of young people, and something about women.

In broad strokes, this study coincided with our perception or intuition that the sectors that had worked most closely with us, or which had best understood our word as Zapatistas—indigenous peoples, women, and young people—continued to be near us and continued to maintain this synchrony, not as a result of the virtue of our discourse, but because of their own realities. That is, it is not the eloquence of our word that has earned their ear, bur rather the fact that they are seeing and living things similar to what we are; this is why we are speaking the same language.

We told ourselves we could construct a movement if we could construct a common terrain. The terrain that the EZLN inhabits is a clandestine political-military one, and we would need to construct another level, another terrain of encounter, another space, like you guys say, to meet each other. And this was what the Sixth proposed. The place where we would meet would have to be in their places, on their terrains—no longer just Zapatista initiatives in Zapatista territory, because this would imply once again the hegemony of the EZLN with respect to the tasks and priorities set and the paths and companions taken, which is what had marked the previous 10–12 years. So we said, if we make this common territory and common terrain, it has to be with them, where they are, and that means we will have to come out.

So we did this kind of diagnostic of suffering, of the criminalization of the young people, of this, how do I put it, this fraud of gender equality. By this I mean the assumption that the struggle over gender has advanced, because, within the political class or the wealthiest and most powerful business sector, women have been able to appear more visibly, which hides the fact that intrafamilial rape continues to be a problem, that aggression against women just because they are women continues in the streets, at work, in school, everywhere. And on the subject of indigenous peoples...Yes there had been much attention given to the indigenous Zapatistas of Chiapas, and secondarily to the National Indigenous Congress. But there are other indigenous peoples that were not even named, not recognized, as if they did not even exist. These are the things that were discovered, among other things, in the first journey of the first phase [of the Other Campaign].

We had thought, we must construct this terrain of encounter, but we must also ask ourselves, “What for?” Then the basic principles of the Sixth were established, and we decided we were against the political class, against the system, and we were going to identify the common enemy of our pain and the form in which we would find that enemy and fight it. We were given the image of a country with many pains but still marked by what the mass media presents us with: this great divide between the north of the country, which supposedly has a quality of life similar to that of the southern United States, and the Mexican south, which is said to have a quality of life closer to that of Central America. This is why it is presumed that the great movement of people to the Other Side [the United States] came principally from the states of the south and from Central America.

When we began the journey, the first part, it was confirmed that there is in effect a significant acceleration of the loss of lands and thus the expulsion of indigenous peoples and poor farmers to the cities and toward the north-ern border. Schools in general, from kindergarten to postgraduate studies, are undergoing an accelerated process of privatization, which leads to a lowering of the quality of teaching, the quality of education, and the quality of research, above all scientific research, which is converted into a kind of factory for large transnational corporations. This is what they said in one state, Veracruz, where they told us, we didn’t realize that scientists are participating in a huge war industry. We were buying the myth that we are doing objective or neutral science, even humanitarian science, and it turns out that it is one part of the knowledge that, in another part—in this case in large research centers paid for by private companies—is being converted into something harmful for humanity.

On the subject of women, with regard to politics from above within the political class, when the struggle of women is institutionalized—that is, when it is accepted that there are rights that must be recognized—here in Mexico appears this great generalization that there can be good laws but they are not implemented. But what we found was that in addition, there are bad laws that are also not implemented. The other thing that we found that was not detected by the first group [Elias Contreras] was the destruction of nature, now no longer because of the inattention or care-lessness of governmental authorities or of the population, but rather as a purposeful policy of destruction, which is the case in all the coastal zones, in the Yucatan Peninsula, in Veracruz, and on the Oaxacan coast. Up to the Federal District [Mexico City], the center of the republic, when we had traveled all of the south and southeast and the Yucatan peninsula, the diagnostic was close, but things were actually worse, because there was an element which had not been detected by the commission we had sent—the sensibilities and feelings of the people.

If you recall, the journey changed as it went along. At the beginning, a lot of people came to present their complaint or request, thinking that the Sixth Commission was a channel for getting their demand to the government. But as the journey advanced, this began to disappear, and little by little the forum of denouncement turned into a forum of expression for forms of rebellion and resistance. And the people started getting to know each other. And we discovered a hurting country but also a very organized country—organized, but dispersed. Many of these rebellions we had not known of; that is why we make reference to the mass media, because it seems as though if one doesn’t appear in the media, one doesn’t exist. In this sense, the EZLN existed because it appeared in the media, and since now it doesn’t appear, then it must not exist anymore. If that happened to us, what was happening to the rest of the people that had never appeared in the mass media? The Other Campaign means to be the forum where one begins to say, “I am this, I am here.”

When Atenco occurred and we stopped in the Federal District, the record so far was more or less balanced [between pain and resistance], with the addition of this surplus, this extra learning, that we had discovered in these organized rebellions, which is not the same as just a rebellion. And the Other Campaign had the opportunity to generate a network between these rebellions. At this point the danger was the hegemonification of what had flourished precisely because of the fact of being so different. At that time, certain tendencies had already arisen within the Other Campaign that tried to create a single party, a single movement, a single organization, which in our view would have meant that these different rebellions would have to retreat or retire. [We saw that] they were not already in a single movement or party for a reason.

When we took off to the North, we left with the prophecy that we were going to go completely unnoticed, that the conditions were completely different. But what we discovered in our path, if you remember, was that the conditions are the same or worse than in the South. We had bet that the North shared with the South historic and cultural roots, and for this reason continued to be Mexico. But in the progress of the journey to the North of the Republic, we discovered that in addition to sharing similar living conditions, the North also shared with the South experiences of organized rebellion, though dispersed.

So after this year’s journey, on one hand we have a country in a more serious state of destruction than we had thought, more in a state of ruin, we say, but also much richer in terms of the organization of the people than what we had thought. In fact, in some parts we were already insisting that it was time to design an organizational form that didn’t erase the existence of the great plurality that characterized these organized rebellions. Unfortunately, this was understood then as if the Other Campaign is the place for whomever, even if they aren’t in agreement with the Other Campaign. We think that there does have to be a basic political definition, but that it has to respect, maintain, cultivate, and make grow its spaces of autonomy and rebellion. So, in broad strokes, we have these two results or these two axes: that of destruction, which is telling us that there is no longer any turning back, that this is the last call, as we say, and that if we take the slow road, little by little, we are not going to have anything left to save or rebuild; and on the other side, that of the rebellions that are clamoring for a national organized space, without losing their identities.

2. A SCRAMBLED GEOGRAPHY

How do the Zapatistas imagine the Mexican Nation in its deterritorialized reality, deterritorialized on one side by a globalized economy and a transnational division of labor, and on the other by indigenous peoples, Mexicans, Chicanos, all of whom were crossed by the border, instead of the other way around, and now find themselves on both sides of this line? What would a new nation and a new constitution look like in this context of scrambled geography?

What we try to teach people—and to practice—is modesty. We have to recognize that there are realities that we cannot imagine, just like there are worlds that we cannot imagine; and the fact that we can’t imagine them does not mean that they aren’t possible. This Mexico, so complex in its destruction, could be equally complex in its richness. But we can’t imagine it, because when we try to imagine it, we use referents that we already know. That is, if by the new constitution we are imagining a group of intellectuals that get together, write up some good, well-intentioned laws, decree them and have a party and set a date to celebrate, where the children sing the national anthem and salute the flag, well no! We are saying that to make a new constitution is to create this common bridge, a new agreement. You and I are going to come to an agreement on how we are going to relate to each other; and this agreement is going to be different from what we have ever known, because you and I are going to be different from what we have ever been, because of the place we occupy. Neither women nor indigenous peoples nor young people, to speak of the primordial sectors of the Other Campaign, are going to be the same in the new Mexico. Not their demands, not their forms of conceiving of themselves, and not their futures.

Talking to a compañera in the Other Campaign, I said to her, you can imagine, as a woman, a Mexico where the factories are the property of the workers, but you can’t imagine one where you can walk in the street dressed however you want without being harassed. You can’t imagine this, and here we can help, because we can imagine it. If we think another world is going to be possible, the fact that we can’t imagine it because of our education, our history, because of where each of us—we as indigenous peoples, others as migrants, others as academics, others as a cultural-artistic group, etc.—directs our gaze, does not mean that it isn’t possible to make. It seems impossible to think that one could construct a nation with that border there, with immigration, with the Minutemen, with Bush and all that, no? But the journey of the Other Campaign demonstrated that from one end to the other, organizations, rebellions, and movements are arising for whom this border doesn’t exist; that is, it doesn’t exist in real terms. In this sense, we can find cultural roots deeper in North Carolina than in Polanco in Mexico City, despite the fact that this line, this border, divides one country from the other.

So we say, how are we going to do this? By guaranteeing that the Other Campaign, or this great movement whatever it will be called, will always have a space for listening, and that this listening will always take into account what it hears. If it’s not one group, however good a group it is, the Zapatistas, or a group of really good intellectuals, if instead of this one group deciding what the path will be, we all decide, or we take the word of each and every person and start to construct something, that is where we will go. If you remember when we went through Jalisco, we went through a place where there was a mural, and it was a compañero of the Other who painted the mural. So when he was showing us the mural, I think it was in Ciudad Guzman, I asked him, “So, when you made this mural, did you imagine how it was going to look?”

“Yeah, I imagined it already finished,” he said.

“But even so, you started to make it and some things changed and the result is different but similar to what you imagined.”

“Yes.”

“Could you make a mural,” I asked him, “start a great drawing with many colors, without knowing the result?”

“No,” he said, “That would take a lot of imagination.”

That is the Other Campaign. We are starting to make the outline of something, though we don’t know how it will end up. Our honesty and our humility is to recognize that we don’t know. The only guarantee that we have that it’s going to be better is that we are choosing an ethics. And the ethics we are choosing is the ethics of the people, the people from below; we are choosing to give them their place. It’s not about seeing if in the future there are going to be better salaries, or better prices, or whatever. We don’t even know if there are going to be salaries. This is a recognition of the limits that we have, that our horizon is this world that we have. And what lies beyond, that is for others to determine.

This is what the Other Campaign is proposing. Those who try to explain us as a movement, an organization, or a political party, take as their referent what is already at hand. We say no. They say a federation of organizations, or a united front of organizations will have to form, some kind of single unit, or a national dialogue, or a popular assembly like in Oaxaca, or a National Democratic Convention like that of Lopez Obrador. No! The surest thing is that it will be none of these things, because each of these has the horizon of a specific problem—and the problem here isn’t defined still, other than that it is a system. None of these other movements or organizational forms take seriously that there is another reality in another place that is the same. If the first journey of the Other Campaign removed the barrier that separated the north from the south of Mexico, then the second phase, which we are going to launch starting in the north, we think will erase the [US-Mexico] border, in real terms, that it will be a bridge to the migrants, the Chicanos, to all of the realities that are on the other side. I’m not talking only about people of Mexican origins, also the original peoples of North America, to people of color, to immigrants from other parts of the world, for example from Asia, to the white low-income population, to all those there who are saying, “And us? What about us? Here in the belly of the beast, is solidarity the only thing left for us?” Saying that there, one can’t do anything because everything is about television, everything is about drugs, everything is just shit...We think that these people are going to start making their bridges, and that there is where we have to give some room to imagination.

If someone from the other side of the border and from this side of the border had the imagination to imagine him/herself as a rebel, then think how much more we could imagine a world that has nothing to do with this one—not the relations between men and women, not the relations between generations, not the relations between human beings and things or nature, nor between races, to put it one way, or between nations with different cultural roots. That is why we say that the Other Campaign, and I am referring not just to what was originated by the EZLN but to what has been born in the journey out of the participation of everyone, is going to be a great lesson for the world that one has to know how to read, and to read with humility. That is what we have not found in the intellectuals that have talked about the Other.

3. WHEN THERE IS NO REFERENT, CREATE!

In the United States, we have a concept of “people of color,” people that for economic reasons have been forced, or their ancestors have been forced, to live in the United States. But even though these people have been marginalized and discriminated against, they do not consider themselves ex-nationals—they are not simply ex-Mexicans, or ex-Colombians, or ex-Africans—but neither do they consider themselves (US) Americans. That is, while they may have deep memories of their lands, many haven’t seen those lands for 400 years; but neither do they identify with a national project in the United States. In our own personal experiences, we recognize a growing population of de-nationalized people that could never recognize the reconstruction of a nation as their project, because they have never belonged to a nation. Currently, we see in the marginalized communities of the United States and Europe that this subjectivity is growing, and we think that this subjectivity may have an important role to play in the construction of resistance against global capitalism/neoliberalism. In your experiences in the encounters with the Other Side and along the border in general, how have you seen this experience and its possible role in the construction of the Other and the Sixth?

The problem is identity. This, what you are saying, is exactly what an indigenous compañera from Oaxaca in New York said. She said, “The thing is that I’m here now.” And what’s more, she said it by video from New York because she couldn’t cross [the border], so she said, “I’m here now, and here I’m going to be something else. I’m not going to be gringo, I’m not going to be an indigenous Oaxacan because I’m not in Oaxaca though I have my roots there, and I’m not going to be Mexican. I’m going to be something else.” But she wasn’t comfortable with this, and she asked, “So if that’s how it is, that I’m not anything, do I have a place in the Other Campaign or not?” We think this is the problem of identity, when one says, “Who am I? ” And they skim the yellow pages thinking, let’s see, my referent should be here somewhere. Yet it doesn’t occur to them that this referent doesn’t exist, that it must be constructed. The problem is not if someone is African or North American or Mexican, but rather that one is constructing their own identity and that they define themselves: “I am this!” The basic element of the notion of indigenous peoples determined by the National Indigenous Congress (CNI) in the San Andres Accords, is that indigenous are those who self-proclaim themselves indigenous, who self-identify as indigenous. There’s no DNA test, no blood test, no test of cultural roots; to be indigenous it is enough to say so. And that’s how we recognize ourselves, the CNI says.

There is no referent in these realities, above all in marginalized sectors, which have been stripped of everything, or have been offered cultural options that don’t satisfy them—because this happens a lot to young people, no? Because one says, “If the option of rebellion is what the mass media offers, between Britney Spears and Paris Hilton, then I’ll make my own rebellion.” Or, “Is this the only way to be rebellious or unruly? Or can I create my own way?” And they start to construct an identity, and they form small collectives, and they say, “Who are we? We are...” whatever they call themselves. [And when someone asks] “But you guys, what are you, anarchists, communists, Zapatistas?” [They answer] “No, we’re such and such collective.”

We think that with regard to communities and collectives, this is going to arise. The world that we are going to construct has no reason to use former national identities or the construction of a nation as a referent. If some group in a North American city constructs its own identity and says, “I am whatever-they-call-it,” maybe not even a recognized name, then a community in Southeast Mexico can do the same thing, to say we’re not indigenous Tzeltales or Tzotziles, we’re indigenous Zapatistas. We constructed that identity. Now [that identity] is not something that we grant, nor something that we belong to. It is a new identity, though there may be elements of, I am a woman, I am a young person, I am indigenous, and I am a soldier, in the case of an insurgenta,[24] for example.

It’s the same for the indigenous woman in New York. Her husband hits her and she can’t even report it because the police can deport her instead of protecting her. She says, I have this reality and here I am going to construct my identity, and it has to do with the fact that I am indigenous, that I come from Oaxaca, with the reality that I suffer as a woman, that I am undocumented, that I work in a restaurant. And her children are going to have an identity that has to do with all this but is different still. In all of the groups that are on the North American border, the southern border with Mexico, there are some that say, “We’re Chicanos,” others that say, “We’re Mexicans,” others that say, “We’re not Mexicans or Chicanos or North Americans, we’re....” And they give themselves a name. And this is our identity, and these are our cultural forms, and we dress like this and we talk like this, and this is our music and our art. And they begin to construct their own civilization, and just like a civilization their existence doesn’t depend on history books with references to the Roman civilization or the Aztec or whatever, but rather that there is a relationship in a community, a self-identity, a cultural, artistic, economic development.

So we say that in this reality that you mention and explain, where you all live and work, the surest thing is that these people create their own identity, and that there’s no reason for us to pressure them to define themselves: “Are you Mexican or aren’t you?” There remains this problem of, “Am I in the Sixth International or am I in the Other Campaign?” Well, wherever you want to be! And they say, “Well the thing is, I’m from the Other Side.” Well yes but no, this doesn’t matter. We think what has to be done in these cases is not so much talk to the people, but listen to them. And with questions and everything, they start to draw their profile. And [they begin] to say, “Well, I don’t identify as Mexican. I don’t identify as African. I don’t identify as North American. I have these characteristics of all of them, but I also have these others, so I’m going to call myself...” And they give themselves a name, like the Chicanos gave themselves a name. The problem isn’t existence; it’s identity. Because they’re going to exist whether or not they are named. The problem is how this identity relates within itself, between those that identify as such, and how this identity relates to others. This is the relation that we want to construct, the new world, where these identities have a place, not just that they are there, but the way in which we relate to them.

4. ON ENCOUNTERS AND BRIDGES

Beyond the deterritorialization of the population or the reconstruction of the nation, the Zapatistas have said that now is the moment in which we need concrete forms of transnational organization and resistance. How do you imagine a possible intersection or possible seamlessness between the practical work of the Intergalactic and the entity of a future Mexican nation? For example, in forms of citizenship or labor regulations; one thing we have been thinking about is the free movement of people with a citizenship that applies to the same boundaries as the North Atlantic Free Trade Association. As part of the Other Campaign, what would the EZLN think with respect to these possibilities?

This isn’t defined yet. In reality, the majority of people in the Sixth are also in the Other, looking for their place. The moment will arrive when they will say, this is my place. But it is also evident that someone who has their historic horizon in Europe will think of different things from someone with their historic horizon in Australia, or Guatemala, or Belize, or Bolivia, Ecuador, or whatever part of the world, Russia. They are going to construct their identity and perspective, their own historic horizon. The new world for a European in the Spanish state means one thing. For the Russian it means another. For a North American it means another. For the indigenous something else, and it varies like that. But what doesn’t exist is what you mentioned before we started, the space to meet each other, to come into contact, to get to know each other. What guarantees us that the reality that the European woman constructs has a relation with that reality lived by a North American who doesn’t know what she is, or with that lived by a woman in the mountains of the Mexican Southeast, if there’s no space for this? Or if only space is solidarity on the border with charity. That is, I remember that you exist when they’re killing you, when you’re dying. In what moment are we going to construct a relationship of respect? This is what we are trying to do in the Other. Yes, we ask to be supported, but we can also give support, even within our poverties and limitations. That is why we sent corn and other goods out to others. We’re not just here to receive; we are an organization, and we can also give.

In this space, the European from the Spanish state, from the Basque state let’s say, to make it an even more conflictive place, is going to contribute her idea with the woman in New York who is a migrant but is not Mexican and is not American even though she has her papers, with the woman who is part of the Good Government Council in a Zapatista community, with the Seri woman on the coast of Sonora. Each person is going to start to say, “For me, my world is this way,” and they’re going to start constructing it and the other is going to learn. Not just to have the ideas, like Moy (Lieutenant Colonel Moises) explained, who said that when people talk to each other they begin to get ideas, and to understand each other’s ideas. Not just this but also to create paths, coming and going, to meet each other.

What is the basic proposition of a dialogue? A common place to speak and listen? No. No, because this is only possible if there is already a stable bridge of communication, a common language. No, the basic proposition of a dialogue is to recognize the existence of the other, to respect them, to say, s/he is other, and I am going to relate to the other, discarding beforehand, not even thinking that s/he has to be like me, or that I will make him/her my way. Like we always say, “The thing is he wants to do it his way,” and that’s where things get screwed up and cause fights and so on. Rather, it must be, this one is different, this other, as I am different. If the problem is no longer who commands, or who makes everyone else do whatever, then we can go on to something else. Because even when there is similarity in the language, or understanding, there’s no common path because there is no respect, even if we’re speaking the same language.

So the basic point that the Other Campaign and the Sixth International try to resolve is this: What place will each person have? And each person will decide that for themselves. The most likely, within the Sixth, is that people say, “We are other,” and they do an Other thing, and this is what it is about, that everyone goes about generating movement. But in this trajectory they are getting to know each other and in the process creating bridges. And the same thing will happen as what happened in the Other Campaign, where the path of the Sixth Commission was the pretext so that others got to know each other, and began to construct bridges and to relate to each other. These relationships are maintained and will continue whether or not the Other exists. The Other could disappear or fail or change names, but this bridge that the Náhuatl of Jalisco made with the Comca’ac and with the Seris of Sonora, that doesn’t have anything to do with us anymore. We were the pretext for them to meet, so they could arrange for our visit. But now they’ve met each other. They’ve heard each other: “Things are really messed up here.” “Here too, we should get together.”

When the Meeting in Defense of Water and Mother Earth took place in Mezcala, in the edge of the Chapala Lagoon in Jalisco near Guadalajara, the Yaquis came. This is a group that generally would very rarely meet with others, not just with mestizos, but also other indigenous groups, because they are a tribe that has grown from battling other tribes. All of the tribes of the North are warriors, because they were attacked by the Apaches and the Comanches, the Mexicaneros, by everyone. But they began to meet, now not dependent upon what the Other Campaign says or if the Sixth Commission convokes them. The problem is not going to be how the Sixth International relates to what comes out of the Other Campaign, but rather, what is the place that we are going to construct all together? And it probably won’t have anything to do with what we see now. If the Other Campaign that you see now—a transnational movement already, because already it is more than a national entity—is different from what you saw in September of 2005 here in this very place in La Garrucha [where the early meetings and plenaries of the Sixth Declaration were held in the fall of 2005], if it changed that much in one year—it changed protagonists, it changed its objective, it changed its voice, it changed its horizon, it changed its pace, it changed its company, now we are all others, we became ourselves, who we are now, along the way—then just think, the same thing could happen in the rest of the world and the rest of the country.

5. THE MOVEMENT OF MOVEMENTS AND THE GENERATION OF ‘94

There is something that today we call “Generation ‘94”: young people in the majority but also people of all ages, who had their political education in Chiapas or via Zapatista discourse and practice communicated through informational networks. These people, or this network, have made, politically, something like a Zapatista diaspora, which has had a profound and reciprocal effect with other movements and spaces: the alter-global movement, the World Social Forum and the regional forums, for example, in a Left that is young, global, and committed to making an “other politics,” in organizing itself without doing the politics of politicians. The impact from our perspective has been deep and strong. What has been the effect in Zapatista territory of these interchanges and of the birth of what could be called a diasporic Zapatismo?

First of all, it may be what is least seen but it is also what is most felt here inside. Almost since the very beginning, the presence of all these groups removed from our struggle the horizon of fundamentalism. An organization that is 99.9999% indigenous has always the temptation of becoming a race movement, especially in the Mexican Southeast, where the mestizo has cultivated hate and resentment in the indigenous for centuries. So in the moment when a fundamentally indigenous organization comes into the light of day, and with great strength—and I’m not referring to the media impact in other countries, but rather how we saw ourselves here, we saw that we are many and we are organized and we can do all of this—its immediate horizon is to become a race movement, that is, a fundamentalism, convert-ing the Zapatista movement into a movement against another race (indigenous against mestizos, or between races, the Tzeltales against the Tzotziles, Tzotziles against... and so on). So this shared interchange, this give and take with what you all call “Generation ‘94,” immediately opens for us a new horizon and takes us out of this fundamentalist risk. Now, we never suggested that! I mean that it is a risk that I for one saw, that the moment was going to arrive when they say, take out the light-skinned ones because they’re light-skinned... and of course there are historical arguments which back up [the idea] that from there comes the pain.

So the appearance of these people and this form of relating to people of other colors and other cultures opens the world to us without our moving. We become able to see the rest of the world and other cultures like no one else has been able to, I think, without moving from our communities, because of these people who came from other places. This “talk to me,” this “show yourself to me,” to us as indigenous, was unknown. We would have said, “Who is going to want to listen to us and who is going to want to look at us?” And it turns out that all over the world there is this generation like you say that wanted to see us and listen to us. So we began to listen and to speak and to show ourselves and to see others. We began to see the rest of the world through a whole bunch of windows that were these young people that came to us all this time. And whether we wanted it to or not, this had a beneficial effect on us, because, without losing our indigenous essence, because we are on our own court, in our territory, we can see everyone else without losing our identity. This opens our horizon and changes us; it makes us understand, in an almost natural pedagogical process, sui generis, that the world goes far beyond our noses, however big our noses may be. And that this world is much bigger, richer, better and worthwhile.

So there is the impact that this interchange produces on the outside, which is what you have pointed out in the question. But what it produces inside is, first, it eliminates from us the possibility of fundamentalism. If not, you would have here a war like in the Balkans, first between mestizos, then between groups, between indigenous peoples, between Tzeltales and Tzotziles, later between communities and between valleys, and so on, because that is how history has gone. The survival of the EZLN has to do with the fact that we didn’t fall into this, and we still haven’t. All this has to do with the fact that these other people came to us, that we were able to see out, and these other worlds made our hearts big. And a big heart is not capable of stinginess. To be stingy, to be petty, to be egotistical, you must have a very small heart, and the Zapatista indigenous communities don’t. And this is why, because of this contact, they have been able to construct.