Elisha Moon Williams

Feet On The Ground!

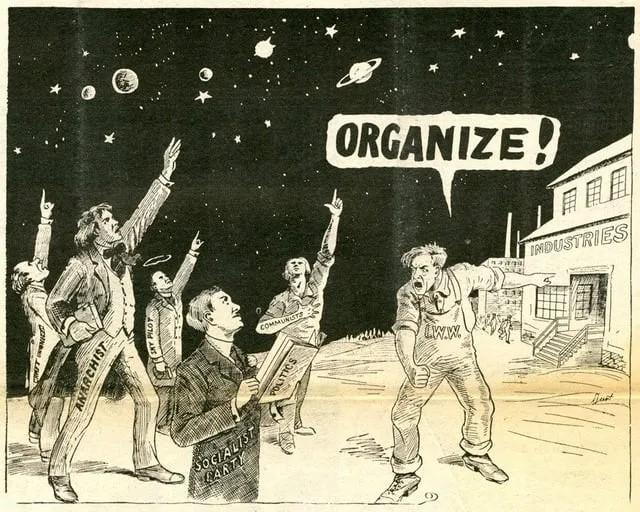

Anarchism and the Labor Struggle Today

When I first started my journey as an anarchist, I was incredibly privileged in both my environment and upbringing. I had grown up in a very upper-middle class suburb, neither knowing economic struggle nor of want when it came to my basic needs. I was, at that point in my life, a young 20 year old ‘man’ living with their parents as I started my doomed college career. That was when I got into the package industry.

Being a warehouse worker within the package industry was the most radicalizing job you could have given me. The sheer amount of naked disregard for safety and the well-being of myself and my co-workers only confirmed the anarchist inclinations that were forming from seeing police brutality against the George Floyd Uprisings. That Uprising was the first time that I, a white person living in the comfort of the suburbs, saw what the police really did to folks that didn’t look like me. However, it was on the warehouse floor that I truly understood what anarchists were talking about when it came to class struggle, white supremacy, and how the latter is used to suppress the former.

It was at that job that I read the anarchist books and zines that would become the cornerstone to how I saw the world and acted within it. It was at that job that I slowly realized my queer identity and adopted the name Elisha Moon Williams. It was at that job that I wrote down the rough outline that would become my first Anarchist Essay, Queers with Guns, in the small notebooks I carried around. Through this lens, I ended up attempting my first round of organization as an anarchist: collective labor struggle. Although I was unsuccessful in my attempt, it was an incredibly important part of my life. Without interacting with such a clear case of class struggle, I may not be the woman I am today.

This story demonstrates not only how important my involvement with class struggle was in my emergence as a queer anarchist, but also how impactful it was in gaining the skills necessary to organize projects later in life. For me, becoming an anarchist was not abstract and intellectual but instead related directly to the world around me and my actions within it. If more anarchists were active within the workplace, more people could have the same experience that I had when I was younger.

There has been an overall lack of focus within the broader anarchist community today on involvement in the labor struggle. There is often talk in online spaces of ‘joining a union,’ but very little in regards to actually organizing within your own workplace. Often times, this makes sense. Workplace organizing and collective worker action are both incredibly risky and not guaranteed to succeed. Not to mention this sort of organizing being directly connected to one’s livelihoods, and that even a successful campaign could contain the risk of organizing workers being illegally fired or reprimanded. In such an atomized and hyper-individualist society, it is more difficult to connect with your co-workers than ever before. These difficulties are real, and are not to be dismissed out of hand.

However, many of the more popular actions focused on by the current Anarchist movement are just as risky to one’s personal livelihoods, if not more so. The protesters’ peaceful actions to sabotage and prevent the building of ‘Cop City’ has given many of its participants RICO charges, including those that simply raised legal funds for their defense in court. Although some of the more extreme charges have been dropped at time of writing, the fundamental charges remain the same for many within that group. These charges give jail times that are comparable or even exceed that of murderers and sex criminals, permanently marking their records as felons if the charges stick. The police have often arrested and charged leaders of protests (both peaceful and not-so-peaceful) in order to break protests that ‘break curfew’ or even because they can.

Another objection that may be made is that organizing your workplace is too difficult these days. Some may argue that the workplace has changed more drastically than the old syndicalists of America and Europe could have ever dreamed of. It is true that the workplace and what a job even means has fundamentally shifted as the nature of the market itself has grown and shifted over the years. There’s an entire gig economy like Uber and Instacart where workers within the same company brand have no idea who their co-workers are, if the term ‘co-worker’ even applies at all. Many of the common workplaces that remain have also been engineered by the bosses to reduce or eliminate workplace camaraderie which could get in the way of their bottom line by daring to exercise their fundamental labor rights, let alone the right to collective bargaining.

The package industry, an example within my experience, is designed to have many of its entry-level workers that do most of the heavy-lifting (literally) burned out and encouraged to either work up the ladder of management or quit. Most of the workers choose to quit, leaving the warehouse a constantly changing meat-grinder of manual laborers, disproportionately people of color, to do the dirty work without ever having to risk them advocating for themselves. Even if giving workers basic amenities that help them stay in the industry long enough to become more competent at the job would give them better long-term profits, it doesn’t matter. All that matters is the short-term value that they are able to avoid losing by treating their workers as disposable machines. Many of the people that stay are those that move higher up the company ladder, separating them from the newer workers and lessening their chance at coming together in solidarity.

These difficulties put in place by the owning class are things that we as anarchists must overcome if we wish to ever grow beyond a small niche of idle intellectuals within the United States and Europe. There is a great opportunity being missed by the Anarchist movement from putting labor struggles on the back-burner. Although many workplaces have changed quite significantly since the hey-day of the labor anarchists, many of the same fundamental truths remain the same:

We have no control over when, where, or how we work. We are only employed for the profit of those that own for a living and often at our own expense. We work under threat of starvation and homelessness. We live under a dictatorship of the owning class every single day, and the workplace is an overt representation of that. It is up to us to agitate for both autonomy and dignity in the one life we know we have.

If there was much more emphasis on organizing our workplaces, many within the Anarchist movement would be able to learn the valuable skills that are needed for us to organize other aspects of our lives. The skill of effectively talking to people outside of our own experience is crucial, something that labor organizing forces you to learn incredibly quickly. Meeting people where they are at is one of the key things that anarchists need to understand in order to build any social organization.

We cannot let top-down, reformist organizations be the only active forces agitating workplace organizing in the United States. In my own home city of Saint Louis, the most active labor movement is the growing amount of unionized Starbucks stores. The biggest group of people involved in its animation weren’t anarchists, but instead the local chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America. The main thing such organizations do is take the radical and active rank-and-file workers that agitate for change and better working conditions and place their aggression, ingenuity and energy into forming the exact same kinds of unions that are responsible for their own decline within American society. Unions that are intensely hierarchical, while being used as pressure-valves for the workers’ frustration and anguish without ever challenging the fundamental relationship between worker and owner. Unfortunately, Starbucks Workers’ United seems to have become that exact sort of union. Within my own experience, its upper management only approved performative one-day ‘Unfair Labor Practice Strikes,’ that ultimately never truly threatened the company of Starbucks’ profits. The union itself and how strike funds are doled out are purely run by the national organization and decided by its Board of Directors at the end of the day. Although the national union finally has the Starbucks Corporation at the bargaining table, such a goal could have easily been reached sooner if more firm economic pressure was placed upon the coffee giant. We need to be fighting for something greater than that, as anarchists. We need to advocate for the workers to represent themselves in organizations made by and for themselves and their own interests.

If we truly wish to connect with other working class folks, then we must be actively involved in agitating against some of the most authoritarian systems in their daily lives. Otherwise, they will remain trapped in the merry-go-round of trying to reform a society fundamentally based on violence and domination. The systems that dominate all of us will only continue to perpetuate themselves. We as anarchists must make the active decision to focus on labor struggles in our own neighborhoods. The future of our communities depend on it.