David S. D’Amato

GDP as Ideological Scam

2. Authoritarian GDPism has nothing to do with human freedom

3. Growth obsession, epistemic crisis, and counter-productive institutions

4. Instrumental inversion and the evacuation of value

1. Introduction

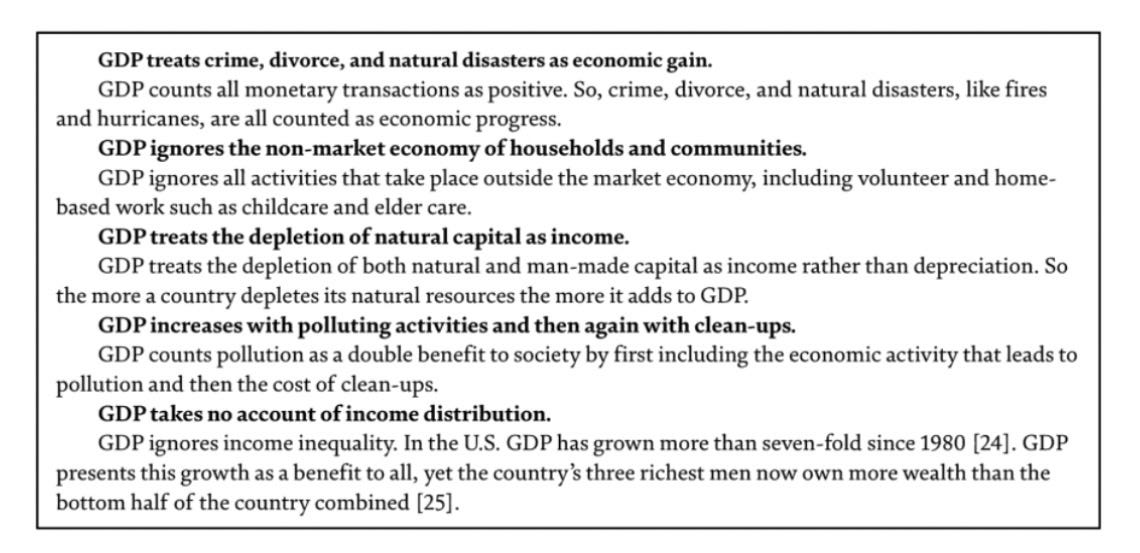

This table appears in Richard E. Rice’s paper Biodiversity Conservation, Economic Growth and Sustainable Development.

Several decades ago, economist Herman E. Daly and philosopher and theologian John B. Cobb, Jr. pointed out that in a “full world” with finite resources, economic growth can become uneconomic when the environmental and social costs outweigh the benefits. We are today deep into this dynamic. I think there are several questions we are duty-bound as rational people to ask at this stage in our adoption and use of GDP: What do we mean by growth fundamentally? What are we trying to grow and get more of? Do we want more war? Do we want more tech billionaires? Do we want more AI slop? Do we want more land theft from the Global South? Corporate consolidation? There is no point in going on, but as a species, we have the luxury now of asking some of these questions. Growth under capitalism has historical and empirical answers to every one of those questions. It does, for example, reward war and empire. It rewards many of our most destructive actions and types of behavior. The ruling class could change that, but the ruling class is in the business of war. If the lord under the land-based feudal system was both the warlord and the economic ruling class/beneficiary of exploitation, then our system effected a split between those functions: government is supposedly de-personalized in the state, and the beneficiaries of the system supposedly exist in a separate, strictly economic sector (I know - it is okay to laugh). We know, of course, that the economic ruling class remains dependent on the power of the state.

GDP is not only a measuring tool; it is also itself a political ideology and system, one that is shared around the world, though not universally accepted. It is a narrow and deeply ideological construct, not a neutral or objective measure or way of describing economic reality for real people; it carries hidden decisions and determinations about what is actually valuable and how we should think about that question. It contains subjective assessments about how we should spend our time and which global ways of life are valid and aligned with the official version of progress. GDP and similar measures do not represent something real or in any way consistent with legitimate scientific practice. They are artifacts of an ideological system designed to recognize and reward certain behaviors incentivized by the ruling class. Robert F. Kennedy (the superior original) was famously critical of GDP when he spoke at the University of Kansas in ‘68, observing that it measures everything “except that which makes life worthwhile”:

It counts the destruction of the redwood and the loss of our natural wonder in chaotic sprawl. It counts napalm and counts nuclear warheads and armored cars for the police to fight the riots in our cities. It counts Whitman’s rifle and Speck’s knife, and the television programs which glorify violence in order to sell toys to our children.

It is important for Americans to understand that GDP represents a specific ideological system and has nothing to do with liberal freedoms or any valid reason for defending the notion of a competitive, market-based economy. Even the arch-free market economist Ludwig von Mises consistently denied that there could be any single, objective measure of social welfare or national prosperity, claiming that attempts to create such a standard (e.g., GDP) are always inherently flawed. The attempt itself is the problem, putting the cart before the horse: judgments about the value of a given thing or service are always subjective, so those who believe that the goal is to max out value under a particular arbitrary standard are profoundly mistaken. Mises concluded correctly that “it is nonsensical to reckon national income or national wealth.” He writes:

Some economists believe that it is the task of economics to establish how in the whole of society the greatest possible satisfaction of all people or of the greatest number could be attained. They do not realize that there is no method which would allow us to measure the state of satisfaction attained by various individuals.

Market economists of all stripes have long insisted that economic valuation is subjective to the individual and their unaccountable tastes. Mises took this more seriously than most other liberal economists and rejected the idea of GDP out of hand, seeing the absurdity in allowing any group of people to determine what is valuable and what counts as economic progress or growth. Of course imperialists in Washington, in both parties, love GDP and the politics that goes with it hand in glove, but we should never pretend that it is what it pretends to be, an objective way to take the measure of the economy. Mises argues, “To prefer and to set aside and the choices and decisions in which they result are not acts of measurement. Action does not measure utility or value; it chooses between alternatives. There is no abstract problem of total utility or total value.” It is clear that Mises makes the fact of individual action primary in his thought, just as Frederic Bastiat, discussed below, had made choice and freedom primary. Where GDP ideology takes an arbitrary construct and treats it as the central reality, Bastiat and Mises wanted approaches to economics that start from the acting person.

I don’t think people who are interested in liberty, however conceived, should be spending any time defending GDP. No less a free-market liberal hero than Bastiat rejected GDP’s core premises, though he wrote in the middle of the nineteenth century, long before it was formally developed. Many liberal economists have also inveighed against the broken-window fallacy, the idea that it is possible to create new wealth by destroying things. But today they readily accept it themselves in their embrace of GDP, as it is conceived in the ruling class. GDP is structured to reward the very worst things human beings engage in, including the worst one of all: war. War and GDP are of a piece, and understanding their relationship is among the keys to an accurate model of our political and economic system. What Bastiat argued is that destruction, the shattering of a shop window, for example, does not actually create wealth, since the wealth bound up in the new window pane (and importantly all the work behind that) and the repair are being diverted from other potential uses. But GDP accounting asks us to accept exactly what Bastiat ridiculed and condemned in registering repair, reconstruction and similar efforts as real wealth creation, real growth, without addressing the destruction itself, without netting out the lost value of whatever was destroyed.

GDP encourages needless destruction and violence by making the mere churn of activity the thing of value, to stir up and measure, even if the activity is in manufacturing weapons for empire and genocide. In the case of the U.S., the major product seems to be dead bodies and refugees. Is this Blessed Growth? Within this framework, most of what economists class as “economic growth” today is some combination of war and mass murder, speculation and valuation bubbles, and professional services associated in one way or another with tending to the ever-growing and insatiable needs (legal, financial planning and investment, travel and leisure, etc.) of the extraordinarily rich. We are asked to worship growth. Fair enough. How much of the “growth” of the past 30, 40, 50 years is in what economists call the real sector? Americans are beginning to notice the more extreme contradictions of capitalism. They are starting to wonder how it could be that more Americans than ever are invested in the equities market while the so-called American dream dies. It is almost as if the death and speculation economy is fake, and global mega-companies are using the state to swindle us. Economic power is more consolidated by the day: the stocks of ten companies now make up about 40 percent of the S&P 500 index. Are we ready yet to talk about what we are measuring and why?

One of the top justifications for new wars of choice and massive levels of “defense” spending in the post-World War II years has been the economic stimuli they are said to bring, that is, because they increase GDP. This is neither incidental nor accidental, as GDP was concocted during WWII (so many of our worst ideas come out of WWII and the years immediately afterwards) mobilization as a way to measure industrial output, and war production was its original model of growth. I have previously argued that the centuries-old relationship between the modern state and capital is on its firmest foundation in war; understanding this dynamic is integral to developing a full picture of what is happening today, and GDP and its idea of growth are a key driving force. I see the much-discussed abundance ideology as making many of the mistakes that GDP represents generally. The abundance religion will always be on the wrong path without a compass because it puts a made-up ideological construct into the primary position, and thus makes something totally imaginary the foundation of the whole ideology. This is very much the role of ideology in the economic system, to reconcile us to what we see. If we’ve accepted that it is the highest GDP that gets the trophy, totally regardless of other factors like human life, then maybe it’s no wonder we are able to regard the mass murder of defenseless women and kids as a form of economic growth. We will always be lost as a society and culture if our ultimate objective is increasing growth as conceived by GDP; this is just the mindless destruction of a metastasizing cancer made into a political and economic ideology. Once you enshrine socially the abstraction that insists upon more no matter what, you have a perfect cover for war and empire without end. GDP and the abundance ideology jettison the values of freedom and equality from the notion of social progress, claiming that more stuff will suffice. I criticized this several years ago as “statistical utilitarianism,” and I see the GDP ideology as even more entrenched and pervasive today.

It is frankly hard for me to imagine how we could have a discussion on abundance today without addressing the problems with the main measure of abundance in public policy and academic circles. Appealing to economic growth is not neutral if the measure of growth is GDP. If we’re going to talk in these terms and assume more is better, we have to ask, again, more of what? More throughput and more massive-scale operations are not necessarily to be desired or pursued; we have to know what we are producing and why. Our ruling class and most of the literati agree with the substantive positions GDP entails, and they agree with its version of abundance. But that version is not abundance in itself, only a particular model of it that privileges sheer scale, higher and faster throughput, and ever-increasing consumption of commodities. It has never been clear to me why people who say they favor human freedom and flourishing would buy into such a toxic political ideology, one that makes mass incarceration and endless war valid means of growth and “production,” but doesn’t measure vital productive activity like managing a house and caring for children or the elderly. We are not talking about a strictly technical or objective measure. We have to ask seriously what message this is sending and what kind of values it represents. Ultimately, GDP conflates quantity of production, defined in an unhinged and authoritarian way, with quality of life. GDP serves the interests of the ruling class in that it tries to naturalize systems of violence and suffering and shapes policy discourse around bare growth rather than human well-being or other goals.

2. Authoritarian GDPism has nothing to do with human freedom

If you are struggling at this point to understand why GDP is so important to the substantive conversation about what we want our political-economy to look like, I think it is this: our ruling class has made GDP much less a technical standard than a strict prescriptive standard, under which liberty and the legitimacy of our institutions, etc., are now judged. This is a crucial philosophical distinction. Several years back, during a friendly exchange with a friend who today works at the Cato Institute, I asked whether he could conceive of a legitimately free market, under any definition he preferred, that did not culminate in growth as measured under the GDP ideology. His reply was blunt and reveals much about the way we think politically today: “Then what would be the point?” To him, and to many contemporary self-styled libertarian and liberal types, the justification for liberty is instrumental: freedom is important in that it produces more stuff, regardless of what the stuff is (and that’s important, as discussed last time).

GDP has thus colonized and corrupted libertarian rhetoric, displacing older, more principled objections to concentrated authority. I’m reminded of that revealing response often these days: to this professional thinker in Washington, DC, the only reason for a person who describes himself as a libertarian to prefer human liberty is because it leads to growth, defined specifically in terms of the GDP standard. This was offered to me by a senior leader at what is arguably the most important libertarian think tank. I believe, on the contrary, that serious libertarians and anarchists must forcefully interrogate a GDP ideology that designates a particular reification of economic growth as a normative goal, the normative goal, not only a descriptive metric. My friend’s response to my question points to important insights, both as to why the U.S. libertarian movement lost its way and ended up worse than irrelevant in the Trump era, and as to the location of the real disagreement between genuine libertarians and today’s mainstream liberals and libertarians.

Our embarrassed elites want to believe that rising GDP is necessarily associated with freedom, that growth and capital accumulation both result from and produce freedom. Though it remains appealing for obvious reasons, it is fundamentally not an accurate picture of what we’re seeing today. So many of our elite class’s deepest, most harmful misunderstandings about our political system stem directly from the dominance of GDP not as a unit of measurement, but as an all-consuming ideological lens. But by accepting GDP at face value, carrying on the pretense of its neutrality without interrogating its normative assumptions or the social project embedded in it, they are advancing an incoherent argument. Our intellectual and explainer class, because they have not understood the relationship between the state and capital, dramatically overstate the connection between liberal-democratic freedoms and growth/capital accumulation. This misunderstanding is at the core of elite political discourse in our country today. It appears to be the case that they are honestly completely ignorant as to how the social-economic mechanism functions. First we have to acknowledge that in historical and material terms, massive accumulations of wealth, and “growth” in the terms preferred by GDPists, was almost always achieved through conquest, theft, and slavery. I realize this is uncomfortable for the boot-licking variety of human produced by our current social system, but throughout history, if you had great wealth, you almost certainly stole it. I believe we ought to honestly acknowledge the role of violence in the accumulation of wealth, as it exists as a historical fact.

The rise of capitalism historically depended on era-defining structural violence like the large-scale dispossession of peasants in Europe, the use of a slave-labor economy for centuries in the colonies, genocidal slaughter of and theft from the indigenous peoples of the Americas, etc. These are familiar, well-documented episodes. I have always chosen to simply call that system “capitalism,” opposing it as a violation of clear and fundamental libertarian principles, as so many past libertarians did. Much of the confusion discussed here arises from attempts to apply a term like “capitalism” anachronistically to figures who would’ve neither identified with nor defended its present growth-obsessed, deeply authoritarian form. Even those nineteenth century liberals who defended or accepted certain economic features associated with capitalism (for example, the wages system) did not call their preferred liberal system capitalism. This complicates and problematizes the use of the term in conversations about abstract political theory: it is frequently the case in conversations with right-wing libertarians that they are using the word to describe a system that anti-capitalists could not possibly associate with historical capitalism. What is much more clearly defined in historical terms is that the first libertarians (here, as opposed to liberals) were always explicitly and committedly opposed to capitalism, as I’ve discussed elsewhere.

Still further confusion arises from our retrojection of terms like capitalism, the meaning of which had not solidified when many of the liberals now associated with right-wing libertarianism were active. And to that point, the meaning has not yet solidified even today. During the nineteenth century, there could be no such thing as a “right-libertarian,” which ridiculous, bastard idea became possible only after libertarians became sufficiently confused about what they were supposed to defend, as we see in the GDP and prosperity discourse. Libertarians now must appreciate that today’s pro-capitalism ideology is structurally very different from the principled philosophy of the nineteenth-century individualist anarchists, who really were market-first in the sense of defending genuinely free competition and exchange against state-backed monopolies. Historically speaking, libertarianism is a left-wing philosophy whose foundations are explicitly anti-capitalist and deeply motivated by the effort to show capitalism’s continuity with previous systems of authority, suffering, and exploitation. You will not find one libertarian of the nineteenth century who defended this hollowed-out and ethically bankrupt “defense” of liberty, under which freedom is only important instrumentally to churn out more crap, yet somehow this is the dominant framing of libertarianism today. The primary reason for this is simple: as it does everything else, capitalism co-opted and fundamentally changed the character of the libertarian philosophy from a principled defense of human freedom in the abstract to a cynical defense of a system defined historically and materially by race-based chattel slavery, massive-scale land theft, rafts of special privileges for chartered arms of the state (corporations), and untold other extreme violations of human dignity and freedom. Libertarians who see capitalism as consistent with their values are so hopelessly mired in distorting ideology that they can ignore the most salient facts of modern economic history.

We have been reluctant to honestly acknowledge the role of conquest and slavery in creating historical civilizations’ towers of wealth, but it is strange that this should so embarrass us. As soon as we’re able to zoom out from our current (almost meaningless) political discourse, we remember the obvious truth. There are no pyramids in Giza absent an authoritarian social order willing to impose brutal slavery. This is only hard for us to see because of where we stand in history. But understand, too, that there is no system of corporate capitalism, no billionaires, without unwilling participants who own nothing and therefore have no choice but to work for the benefit of those with more power. Whatever you want to call today’s system, it is in continuity with the system that produced the pyramids in the Nile River valley more than 4,500 years ago. It is a system of violence and compulsion, perhaps connected globally by market mechanisms, but never fundamentally a system of voluntary trade. The U.S. government spends $1 trillion every year on weapons and war. The entire economic system globally depends on violence from top to bottom.

Think-tank libertarianism and liberalism make economic freedom a mere proxy for aggregate output and growth, so freedom becomes valuable only insofar as it maximizes capital accumulation and GDP. Freedom, then, is not valued as an independent moral principle or structural principle. Put another way, this is a libertarian philosophy that does not actually care about human liberty. It cares about capital and its growth and accumulation, even if that takes the primary position and subordinates the freedom of the individual person. This is clearly something very different from classical libertarianism, arguably close to its opposite. But it is the “libertarian†concept of almost all American “libertarians” today, under which if there is a conflict between freedom and capital’s unquestioned prerogative of growth, growth wins. This feels like another philosophy, perhaps utilitarian GDPism, rather than a real concern for human freedom and flourishing.

I see this fight as one of deep statist privilege with some market mechanisms versus markets without privilege. Under capitalism and GDPism, growth and, in the nineteenth century anarchist parlance, the “trinity of usury: rent, interest, and profit” take the elevated, primary position over freedom. Under a mutualist free-market system, freedom comes in first place, and property titles and wealth generally must be predicated on and consistent with valid libertarian means. In its simplest terms, the American mutualist or individualist anarchist tradition contends that property titles not grounded in actual occupancy and use and voluntary agreement are illegitimate, like state-granted seigniorial titles excluding others in order to produce rent streams for rulers. If legitimate property is based on genuine occupancy and true voluntary exchange, then state-created and -enforced monopolies (and, as did Tucker and his ilk, we can generalize this analysis beyond land tenure and related rights, to patents, banking monopolies, etc) are illegitimate grants of special status, something libertarians pretend to oppose.

To individualist anarchists like Heywood and Tucker, under every question was the broader one of whether freedom can ever be subordinated instrumentally without being wrecked in the process. They were examples of the kind of libertarian who believes means and ends must align, that you can’t get a broadly free society by building it on violations of individual sovereignty and liberty. Freedom and equality always move together in this philosophy. “Libertarians” in the District do not think this way: they think a society can be free and yet built upon the most violent violations of individual rights, as long as the end result is growth as defined by GDP. This is a thoroughly impossible sell for those of us who got into libertarianism because we like freedom, not because we wanted to defend a system of intensive and sustained intervention on behalf of an extremely small, idle group.

Many of you understand intuitively why it is that a system prioritizing accumulation and growth rather than the freedom and autonomy of the individual human being is so dangerous. You understand something our intelligentsia do not. The inversion of priorities effected by GDPism, its subordination of liberty (understood by Bastiat and Mises) to piles of stuff and pure churn, offers a convenient narrative for centralizing power and crushing the individual. If economic growth is paramount, which it is in the U.S., rulers can cynically justify curtailing basic civil liberties as necessary for economic progress. The focus on aggregates like GDP also obscures the fact that the political-economic system doesn’t dole out the benefits of growth to everyone. This means that even as inequality worsens, authoritarian rulers can claim legitimacy by pointing to abstract growth. But growth is not freedom. Pyramids and cathedrals do not represent freedom, but slavery. The sooner libertarians understand the difference, the sooner they can get back to the defense of freedom instead of falling over themselves to defend state-backed monopoly capital.

3. Growth obsession, epistemic crisis, and counter-productive institutions

An issue brief recently published by the Stimson Center describes the surreal situation we find ourselves in:

National security spending has grown nearly 50% since 2000, and the Pentagon budget alone will soon reach the trillion-dollar threshold. Still, lawmakers, Pentagon officials, and defense industry spokespeople alike routinely sound the alarm about what they perceive as insufficient national security spending.

It is impossible to separate this absurdity from the social construct of GDP. A sane society would not reward and encourage the needless buildup of the military apparatus and, by extension, violence. When I refer to this situation in terms like surreal and absurd, what I mean to say is that it reflects a deep and disturbing disconnect between the actual security needs of the country and our sick ideology of perpetual military buildup; what I mean to say is that this is not at all a rational response to legitimate threats, but is instead a structural feature of how the U.S. economic and political system is organized. Anarchist, Marxist, and so-called degrowth criticisms arguably converge on the claim that the prevailing GDP-growth model of political economy inherently and intentionally encourages war and imperialism under the expansionist and accumulation imperatives of capitalism. However clearly true it is, this kind of talk piques today’s GDPist libertarians because it offends their primary value, the eager defense of growth and capital’s power of increase. I refer above to so-called degrowth criticisms to call attention to the fact that many of the voices grouped together, often by their ideological adversaries, as part of the broader degrowth wave are not actually making an argument against growth. As we have seen, many historical liberals and libertarians were neither for nor against growth; they simply did not frame their defenses of freedom in terms of economic growth as conceived under the GDP framework (because they understood what freedom means). Any libertarian, as a libertarian, cannot recognize a model of economic progress or growth that legitimizes and sanctifies a permanent war machine. This should be simple and straightforward, but capitalism’s co-optation of the liberal vernacular of rights and markets is so complete today that we can’t imagine “free market” without the military-industrial complex.

I believe that what we’re talking about here is the contracting or atrophy of libertarian subjectivity, to where it is now a purely economistic, pro-GDP growth ideology equating freedom almost completely with corporate expansion and capital accumulation. At the end of the day, whether you like your libertarianism flavored right or left, freedom-as-GDP growth really is a far cry from the richer and more pluralistic visions of liberty we got from earlier libertarian and liberal thinkers. I don’t think we need to accept that individual sovereignty and freedom necessarily imply allegiance to GDP growth or corporate capitalism. There are strong decentralist, anti-monopolist, and anti-capitalist currents present within even liberal, pro-market thought. We need those discourses desperately today to counteract the apparently unstoppable march (nauseatingly called progress) of alienating massive-scale institutions.

To understand the mistake of accepting the GDPist ideology, one must understand a bit about the growth imperative built into capitalism itself. First, I see the inversion discussed in the last part, whereby real-world human freedom is subordinated to GDP growth, as representing our culture’s more general fetishization of capital. To the individualist anarchists, capitalism is really not defined by exchange. It is not, strictly speaking, a system defined by exchange. It is rather an expansionary system characterized by the imperatives of accumulation and never-ending growth. The never-ending is key here because this is a system defined by the fact that it can’t stabilize, always looking for new domains of potential profit and still more growth. Decentralists like Ivan Illich understood that this is not a rational way of life, and it could never be made consistent with the needs or the wellbeing of humans, try as we might to reconcile ourselves to it.

As even the World Economic Forum has pointed out, GDP’s inventor Simon Kuznets was adamant that his measure had nothing to do with wellbeing. Indeed, Kuznets questioned the wisdom and validity of a system that sees all production as exactly the same, and he wanted to subtract the value of things like weapons, financial speculation, and advertising. You may disagree with his priorities. The point is that GDP makes no distinction. From the perspective of global GDP, Kim Jong-un’s nuclear warheads do just as well as hospital beds or apple pie. It’s hard to imagine why any rational actor interested in human freedom or half-decent public policy would employ or give any credence to an ideology like this. It doesn’t make any sense unless the goal of the system is to create wars within the global margins for the benefit of a small ruling class. In that case, it makes perfect sense. The World Economic Forum piece also highlights the fact that GDP is designed to ignore the crisis tendencies of immense size, even as we see these tendencies develop in the financial and healthcare systems. It must be understood that permanent military empire is core and infrastructural to capitalist reproduction at the planetary scale, as is massive scale. Within a political-economic system like ours, the Pentagon budget is necessary to the management of capitalism’s contradictions, to the scaled absorption of surplus capital, and to sustaining accumulation when consumer demand flags or private investment slows.

This political economy of war and empire has given us and our human family around the world a crisis of social dislocation, ecological destruction, war, and famine. But this is the system of progress to the GDPists, and they are at the head of both major political parties in the U.S., with no dissent to speak of. The French government hoped to address some of the clear problems with using GDP as a benchmark of society’s health:

We see this epistemic crisis everywhere in contemporary society and culture; arguably, it is the reason for the apparently hopeless political situation in the United States. People may not be stupid, but they do not understand how to explain what they observe. They see their lives getting worse, more precarious, more surveilled, more meaningless, yet they’re assured that the economy is growing, the stock market is gaining, etc. This disjunction shows, perhaps more than anything else, the destructive lie at the heart of GDPism, an ideology that intentionally treats weapons of mass destruction the same as life-saving medicines. Now, if you believe this is an accident or coincidence, then please pass me what you’re having. I was not raised to be a mark and neither were you. People now believe their eyes, after watching GDP grow while wages stagnated, basic needs like housing became unaffordable, and economic power and wealth concentrated in fewer hands. GDPism is how you get our politics of hopeless alienation and violent conspiracy. People sense, quite correctly and justifiedly, that the official story is a lie, but they don’t have a clear understanding of what they’re observing.

Individualist anarchists understand what today’s GDPist libertarians don’t, that capitalism and its growth imperative are not really about markets or exchange, not fundamentally. They’re about expansion for its own sake, which seems like a form of collective irrationality or a social fixation that, again, cannot ever stabilize. Within this context of questioning a social system in permanent crisis and imbalance, I think the work of Ivan Illich remains useful and important. What we are talking about are social institutions and tools that no longer even pretend to serve people, that instead structure the conditions of our obedience and domination. Illich believed that when our institutions grow beyond certain critical thresholds, they stop serving human needs and transform into systems of domination and dependency. In our cultural acceptance of GDP, we can see Illich’s worry that our institutional systems are creating artificial needs that they then pretend to satisfy, ensuring helplessness in the people and institutions that want them that way. It is clear that our country’s major political and economic institutions long ago underwent this transformation, even as the American people have by and large struggled along good-naturedly against the criminal hypocrisy and malfeasance of the ruling class (in both the so-called public and private sectors).

Part of GDP’s function is to encode into public policy capitalism’s assumption of a permanent right of increase, any resistance to which must be regarded by society as a pathology. In 2025, perhaps no social position is treated as more anachronistic and pathological than a “small is beautiful,” appropriate-technology philosophy, even though it is filled with the ideas needed to remedy the crisis of toxic GDPist thinking. To put an even finer point on the overall social and ideological function of GDP: it turns capitalism’s counterproductive and destructive obsession with accumulation into an official government policy. Wearing its insanity right on its sleeve, it treats all growth as great, all kinds of output as equal (commodity and growth fetishism exploding all difference, even between weapons and basic needs or medical supplies), and all kinds of violent extraction as legitimate. GDP is, in many ways, monopoly capital’s perfect ideology.

The way that GDP measures and what it measures show its fidelity to capitalism’s core structural logic, in which value is in exchange, not need. We might have thought that this would be just the kind of ends-justify-the-means thinking that American libertarians say they hate, but for GDP they are comfortable making an exception. A more robust and critical libertarian approach would prioritize rules (around equal freedom, dialogue and mutual respect, non-domination as a value, etc.) rather than particular end results, keeping the freedom and agency of the human being in the primary position (instead of the abstraction of economic growth). Illich knew well what too many “liberals” and “libertarians” have forgotten today, that freedom is freedom, the capacity for non-dominated autonomous and independent living, not the ability to consume endlessly or to submit to authoritarian institutions. GDP has duped almost all of us into cheering on a profoundly destructive and alienating social and economic system. I’m with Illich in rejecting both capitalist and state-socialist social and industrial models, both being versions of the same growth-obsessed, institutionalizing ideology.

We can’t afford to see GDP as merely a flawed economic measure when it has grown to become an all-encompassing cultural and social script that alienates us from each other and from the conditions for a meaningful life. GDP orients us from childhood to see war and empire as necessary and productive and to accept our dependence on impersonal and authoritarian systems. It says: close your eyes and ears, and ignore your neighbors. Accept that perpetual destruction and dislocation are the price of progress, and do not listen to what you know is true, that the system is making us sick, fearful, and isolated. Our government and corporate institutions are both too big to fail and too big to truly serve; they are instead serving themselves, growing stronger and more powerful as we suffer. GDP misleads us about what it does. It isn’t taking measurement of the economy, but dictating the terms and priorities of value and progress in human life.

4. Instrumental inversion and the evacuation of value

I choose the term “conviviality” to designate the opposite of industrial productivity. I intend it to mean autonomous and creative intercourse among persons, and the intercourse of persons with their environment; and this in contrast with the conditioned response of persons to the demands made upon them by others, and by a man-made environment. I consider conviviality to be individual freedom realized in personal interdependence and, as such, an intrinsic ethical value. I believe that, in any society, as conviviality is reduced below a certain level, no amount of industrial productivity can effectively satisfy the needs it creates among society’s members. (emphasis added)

Ivan Illich

Whenever I criticize GDP, I am pressed as to what I’d replace it with, and many critics of GDP do indeed eagerly pitch their new and improved versions to equally clueless wonks and academics. Perhaps unsurprisingly, I’m not even a little bit interested in such a nasty project, and a central pillar of my criticism of GDP is that it tries to measure the economic health of a country with a single test, even if an aggregate one. I’d suggest instead that no power center, state, or other authoritarian apparatus steering from the putative top should dictate or endorse a single standard of how communities or individuals assess their own wellbeing or economic outcomes. Even a framework that replaces GDP with a range of better and more holistic factors would retain the basic flaw of GDP, at least one of its many, if the standards are endorsed and pushed by the state. For a serious libertarian, to impose any universal measurement system is fundamentally to centralize power around the priorities of that system and the groups of people it empowers. In real life, as opposed to the fanciful world of universities and think tanks, the centralization of power has led to the imposition of a worse-than-arbitrary standard of value on communities whose real needs must always be measured and addressed locally.

To my friends who insist I join the GDP cult, I admit it: I worry a lot about a social system that prescribes one value system and standard for everyone, everywhere, and that is what GDP has done for pretty much the entire planet and human species. This seems intentionally self-destructive. To impose a single dominant standard crowds out local autonomy and unique community needs, and preempts diverse expressions of wellbeing. GDPism’s harmful universalizing tendency thus turns highly context-dependent and contested questions about the meaning of value and human wellbeing and offers a pernicious ideology that pushes aside anyone whose values or way of life falls outside its sociopathic logic of more no matter what. Perhaps most insidiously, GDPism encourages us to look constantly for ways to substitute paid work for leisure. It does not value or incorporate leisure and human wellness at all. In its affective dimension, GDPism makes people feel guilty if they rest or are insufficiently productive, if they’re not generating a form of value that can be measured in a money transaction. Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph E. Stiglitz discusses this change of priorities:

Students seldom studied the assumptions that went into constructing the measure and what these assumptions meant for the reliability of any inferences they made. Instead the objective of economic analysis became to explain the movements of this artificial entity.

We have considered the inversions of priorities effected by GDPism, whereby important normative values like individual autonomy, democracy, and general social harmony and wellbeing are systematically deprioritized and subordinated, often violently, to the interests of capital. Both before and after last November’s presidential election, Kamala Harris stressed that being a capitalist is core to her political identity. In a recent interview with Rachel Maddow, Harris said, “And here’s the thing: democracy sustains capitalism. Capitalism thrives in a democracy.” I don’t mean to pick on Harris at this stage in the game. What I want to discuss in invoking this statement on democracy’s role in sustaining capitalism is the bipartisan normalization of this toxic worldview. Everything in public, civic, political life is oriented around capital and its needs. You are here to serve capital and so am I. Institutions and ethical values are to be judged based on how they align with and serve the needs of capital. The real social problem to be addressed is this GDPist ideology that has poisoned our politics and culture: the belief in accumulation and growth for their own sake; the sad, resigned, unimaginative idea that capitalism cannot be improved upon and this is the end of history; the belief that government can be opaque, undemocratic, corrupt, and authoritarian and everything is fine as long as the economy and stock market are up. The unsettling fact is that the one major party that isn’t openly embracing white supremacy is a bought-and-paid-for tool of GDPist ideology and imperial capital. Many will also recognize the unintended irony of Harris’s remark: democracy (or the appearance of democracy) does of course sustain and insulate capitalism in converting domination into consent through the election ritual. GDPism always puts us back in an upside-down world: democracy is important instrumentally, because it creates a stable and sustaining environment for capitalism. How do we think this is a defensible politics? In any worthwhile construction of liberal-republican economic freedoms, a free and self-governing people should be free to own and exchange property, conduct legitimate business, etc. In this formulation, the marketplace is the instrument of freedom, with a free, democratic society as the end. The idea that democracy sustains capitalism flips the older, stronger liberal view on its head and subordinates the freedom and rights of the people to capital and its need to grow. Freedom becomes valuable only insofar as it protects capital’s arbitrary prerogatives and total dominance of society.

I see this societal violence at capital’s behest as existing on at least two different planes or registers, one literal and material, one symbolic and perhaps cultural. The material violence of growth-obsessed accumulation is salient in the historical record, in the expropriation of the land and labor these systems require. Increasing military spending and commitments, domestic police statism, and brutal austerity are all also structural aspects of GDPist ideologies. On the level of the symbolic, GDPism functions to effect what we might see as a radical monopoly of perception, unilaterally defining progress and thus withdrawing legitimacy from non-quantifiable embodiments of value or need satisfaction. Leisure and fellowship, community reciprocity and mutual aid, local gift and subsistence cultures, creative idleness, &c.; none of it is counted by GDPist death worship. Speaking of death worship, following economists like Seymour Melman, I believe that the U.S. economy underwent a profound structural change after World War II, through which it went from being a war economy during a period of crisis to a permanent war economy. Melman argued over a course of decades that the U.S. national security and defense apparatus became a quasi-planned economy within American corporate capitalism, guaranteeing massive contracts regardless of the health of the real sector, culminating in a form of state capitalism. Owing in no small part to the role of GDP, economics training and public policy today tend to elide Melman’s distinction between productive and parasitic economic activity, just as does the war economy itself. We learn to think in terms of aggregate values like GDP rather than directly assessing the fundamental quality or use-value of what the economy is spitting out:

The gross national product is composed of productive and parasitic growth. As usually measured and presented, GNP includes all of the money-valued output of goods and services—without differentiation in terms of major functional effect. To appreciate the nature and effects of a permanent war economy, a functional differentiation is essential. Productive growth means goods and services that either are part of the level of living or can be used for further production of whatever kind. Hence, they are by these tests economically useful. Parasitic growth includes goods and services that are not economically useful either for the level of living or for further production.

Both Melman and Ivan Illich discuss a withdrawal of decisions and decision-making power from civil society and democratic institutions. Illich believed that expertise had come to replace politics as a community-inclusive process. From this standpoint, maybe what is needed is a kind of re-politicization of the question of value determination, whereby the question of what defines value, wellbeing, and prosperity is returned to communities. Superficial reform without deep decentralization would produce only a subtler form of domination. Where once politics arguably had to confront and adjudicate values, a numerical index now just prescribes them (or, perhaps more accurately, makes them superfluous). The practical upshot is at least twofold, I think: first, ethical questions become calculable problems of calibration and optimization, and second, real dissent is recast as irrational obstruction to efficiency - efficient motion in the direction of more, of growth. This could help to explain why leisure and local solidarity are not merely neglected but pathologized under GDPism; they are epistemically invisible to the regime of administration that Adorno and Horkheimer discussed and Illich so eloquently opposed.

We have a pathological economic system, and GDPist thinking inevitably leads to speculative bubbles, the current AI boom being a textbook case. This is the financial instantiation of GDPism’s inversion, with an economy mistaking its own reflected image for genuine substance. And yet it is really the only imaginable result of a system such as GDPism, returning us to the discussion of the semiotic economy in Baudrillard’s work: the GDPist moral inversion, where elite accumulation replaces social wellbeing and democracy becomes the handmaid of capital’s power, is what Baudrillard would call a hyperreal morality. It is an ethical system that survives only as image, emptied of content but still mobilizing emotion and legitimacy. Freedom is reduced to choice between cheap, shitty commodities. Progress is equated with GDP growth, and irrational speculative frenzy counts as innovation. Thus GDPism begins to evacuate value itself. In Baudrillardian terms, we have perhaps arrived at the moment when “the economy†transforms completely into a simulation or symbol. GDP no longer describes production; it now is the reality of production. Financial markets, policy discussions, and the public culture and psychology come together to form a closed circuit, within which value can refer only to itself. Nowhere is this clearer than in the way GDP registers excitement about future growth as growth itself. Every speculative expenditure enters the accounting as investment, and the collective expectation of profit is treated as evidence of prosperity. Within such a system, we have no way of defining value, because we know it only as a pure abstraction: a number getting bigger, more velocity, more churn, more consumer spending. Observe what happens to the U.S. economy when consumers aren’t buying enough junk. The speculative mania around artificial intelligence is thus arguably GDPism in its purest form, the point at which the sign of growth consumes its referent and the economy generally, not totally unlike Narcissus, consumed by his own reflection. This is just to say that GDPist ideology brings about an ontological collapse of value. In classical political economy, value generally referred, however contentiously, to one of several options, either labor, utility, or scarcity. But, in the final analysis, GDPism dissolves all of those old referents. Its object of measurement and value is the circulation of money rather than the production of needed goods or service to the general social welfare. In a system under which every transaction counts equally toward sacred accumulation and growth, value becomes indistinguishable from simple motion.

Capitalism is not about the principled defense of freedom and fair competition. It is about the defense of capital’s power and its right of increase or expansion, and thus its power over us not only economically, but socially. This has clearly produced a culture that systematically undervalues wellness, creativity, and leisure in favor of endless, meaningless production, regardless of what is being produced.

5. Political kuzushi against "the apiary society"

In our discussion of GDP to this point, we have seen that it embeds and re-transmits deep descriptive errors, that it doesn’t attempt a distinction between qualitatively very different forms of output: pollution, nuclear weapons, and financial speculation are as valuable to GDPists as housing, food, or medicine. We have seen that this absurd and wildly self-destructive feature of our politics is ignored by both parties. GDP’s dramatic misrepresentation of social reality is tacitly accepted. But GDP is not just misrepresenting or misdescribing; it is actively shaping our policy preferences and decision-making because its flawed model is being treated as a direct proxy for positive social change and progress. I have long argued that the advent of GDP was a coup, not for human freedom and competitive free markets, but for further domination of the economy by the state and state-backed and -protected corporate friends. Instead of having an honest public discussion about this deeply corrupt state-capitalist system, Americans instead accept the clearly ridiculous, untenable position of the Republicans and Democrats at face value, with no scrutiny whatsoever. We accept that the only way to think and talk about a normatively free economy is in terms of an ideology that directly contradicts libertarian values. Understanding the socially destructive role that GDPism is playing in our political and our economic system is one of the skeleton keys that will help us reach a new stage of discourse and therefore a new development of freedom.

More than twenty years ago, the German sociologist Hartmut Rosa argued that “acceleration figures as the single most striking and important feature” of the development of contemporary Western society. Rosa said that this acceleration is overwhelming our ability to absorb or understand it socially, creating “a constant pressure to control, parameterise, and optimise every moment,” which leaves us in a state of overloaded “frenetic standstill.” Rosa was clearly far ahead of his time in this analysis. My own opinion is that we ought to be asking social, political, and economic questions very different from those we have asked already. For example, why is – how is it? – that we remain unwilling and unready to confront the macro-institutional core question, addressing the professionalized, bureaucratic, militarized system that GDP growth creates and legitimates? First, we must consider the dangerous falsity in the notion that “the economy†is somehow itself politically neutral or that the GDP measure does not carry its own political perspective. As we have seen in previous installments, GDP is deeply political, doing much more in policy terms than merely measuring. It is also instructing, assigning value and meaning, and shaping the most important areas of U.S. government policy both domestically and abroad. Since its introduction, GDP has become something like a moral alibi for our feckless and untrustworthy ruling class, operating through the spectacle of a fight between the Republican and Democratic parties. GDP made scale, hierarchy, and institutional dependence almost totally invisible to us in our political minds, collapsing everything into a single factor or scalar: output (again, regardless of what it is that’s being outputted).

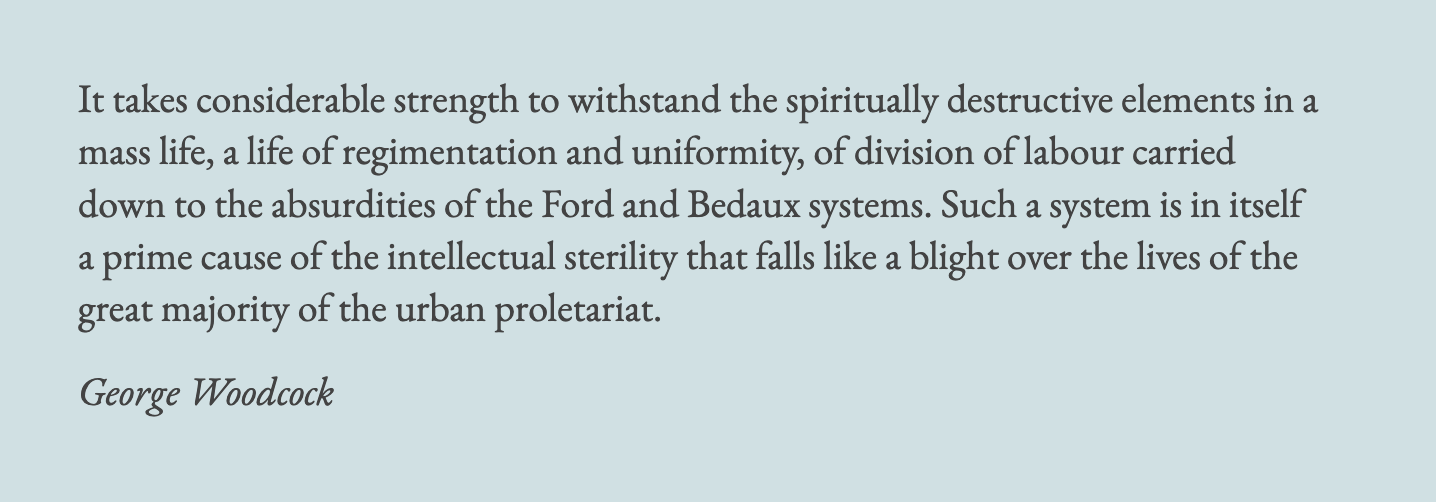

Because I was attracted to the concept of a free, competitive economy of voluntary and cooperative relationships, I wanted to know if we had ever had that kind of economy here in the United States. Or, perhaps, I wanted to know what this concept would mean in practice rather than in pure theory. Related to this endeavor is the fact that the libertarian and socialist movements did not arise in opposition to one another, as today’s confused language often suggests, but together, as twin aspects of a bottom-up movement for both liberty and equality. As the great Canadian intellectual George Woodcock noted, the decidedly “libertarian and anti-political character” of early socialisms like that of Robert Owen (one of my own major influences through the American libertarian Josiah Warren) was in large part grounded in the influence of William Godwin. He contends that the British labor movement owes its antiauthoritarian strain to Godwin more than any other. Godwin, too, was both a libertarian and an egalitarian, the politics we need today. Fast forwarding to Woodcock’s own day, I have long had an interest in “the semiliterary, pacifist, and lifestyle politics” that found a home in the anarchist milieu in the often-ignored years between the classical anarchists of the first generations and the anarchists of the New Left. Anarchists of the Woodcock and Colin Ward types perhaps represent this intermediate period, and their libertarian ideas are humanistic, non-dogmatic, and attentive to the real-world experiments of people helping themselves. We must take care in describing the contributions of someone like Colin Ward as “semiliterary,” as this is not a slight: it reflects a shift in the character of the anarchist movement and its main media and audiences. During this mid-century time period, the anarchists were more active in small papers and journals (of a non-scholarly format) private meetings and personal correspondence, and local experiments.

Of the many reasons I have returned so consistently to Woodcock is his clear and compelling formulation of anarchism; to an American in 2025, Woodcock’s politics could look like an odd mix, the libertarian’s arch-individualism with the syndicalism of a socialist radical. But what’s so interesting about Woodcock as a writer for readers today is his ability to show that his position, the anarchist one, is actually the consistent one. Woodcock wasn’t a libertarian in the way that term is often used in North America now; he saw contemporary right-wing libertarianism as a deep betrayal of libertarianism’s historical and ethical core (for example, with the supposed “Free Trade” philosophy of the nineteenth century he associated only the freedom to exploit). His discussion of the war is helpful to understanding how we got to our present configurations of political economy:

Similarly, small proprietors have either been liquidated by conscription or bombing or are subjected to a mass of regulations which limit their independence to such an extent that they are in effect minor distributive or productive bureaucrats who receive a guaranteed price instead of a salary and are preserved from extinction only insofar as they are willing to serve the state.

Today society in all countries assumes this totalitarian form, which negates the individual and deifies the aggregate. The difference between the so-called democracies and the open dictatorships is superficial and, for the most part, of degree.

Woodcock believed that World War II was “a war between two kinds of Fascism,” neither of which was capable of freeing the people of the world. To him, it was clear that “the typical form of modern society is the totalitarian state,” and that all totalitarian states offered “greater or lesser slavery.” In 2025, it is increasingly hard to ignore Woodcock’s clearly correct assessment of the situation. I believe that a time is soon to come when even Americans will be insusceptible to fooling and softer exercises of manipulative power. In its excesses, the political-economic system is revealing its character to the popular masses with increasing speed.

Woodcock remarked upon an important development within the petty bourgeois, whom he said were “in transition from being servants of individualist capitalism to being more or less direct agents of the total state.” Woodcock’s incisive observation “that under capitalism, the professional/bureaucrat bourgeoisie benefit far more from state intervention than workers” is at the core of what is missing from American political discourse today; always missing is the clear historical fact that the modern state has its true life and existence in the brutal imposition of bourgeois capitalism. Woodcock argues that “even that section of the petty bourgeoisie that continues in private business were becoming tantamount to government agents, an unofficial bureaucracy supporting the bureaucracy proper. I think Woodcock’s analysis points the way to a new way of talking about politics, where we finally acknowledge the obvious truth that the power of capital is ultimately state power.

To Woodcock, the rise of the bureaucracy as its own separate class was a natural outcome of industrial capitalism, attending “the gradual subjugation and robotisation of the industrial working class and the metamorphosis of individual capitalism into trust and finally state monopoly capitalism” (emphasis added). He argued that what was unfolding was the emergence of “the apiary society of totalitarianism,” a society where “a graded and rigid authoritarian hierarchy” replaces whatever had survived of liberal individual rights under capitalism. As an account of what happened economically in the rich West after the war, Woodcock’s is hard to improve on. He correctly damned the modern state as an institution of violence and class rule against the ahistorical idea that it was established for worthy reasons:

It has become an instrument for the protection of the interests of certain classes in the community against those of the remainder, and its forces are used for such objects as the protection of private property, the restriction of personal liberties that may be detrimental to the interests of the ruling class, the conducting of wars of conquest to obtain new markets and sources of raw materials, and the waging of imperialist wars against other state communities whose ruling classes are pursuing similar objectives.

He continues, “This state for which men are asked to die is a cruel abstraction of those who need a myth to enable them to maintain their rule over the majority of men.” But Woodcock blamed us, too. He stressed constantly that the current conditions could never have taken root if we as individuals did not tacitly agree to be dominated and suppressed. He said we had been duped into believing “that the dictates of authority represent [our] own desires.” I see Ivan Illich as defying today’s categories and resisting its totalitarianism in many of the same ways Woodcock did. For Illich, convivial tools are those that enhance one’s ability to act autonomously and creatively, in contrast to industrial technologies that are inherently centralizing and manipulative, overseen by distant experts.

He imagined a political-economy cognizant of limits, the limits of the human being, of power and scale, of the natural world. It’s a politics that reimagines human flourishing and reorients it around proportion and an awareness of those limits rather than around consumption and volume. Communities seem to thrive when they’re small enough for people to recognize each other “not just literally, but to really understand each other” and to fix what they’ve broken. I think we have to consider at this point that massive-scale institutional power, whether governmental, industrial, bureaucratic, technological, or otherwise, is not evidence of progress, but of imbalance and intensive violence to the idea of community and social harmony. Capitalism as we know it and have known it is fundamentally incompatible with human freedom and flourishing. If we wanted to, we could have a political economy that elevates workmanship and connection to one’s work over mere production, that favors convivial tools to mindless technology, that sees education as a process of mutual discovery as against authoritarian lock-up and lectures. Decision-making authority would be held locally with decisions remaining close to the people living with their consequences, and there would be no artificial social separation between freedom and shared responsibility for one’s community. If we took seriously even a fraction of our own pretty words about human welfare, we would measure progress and success very differently, perhaps by efficiency in meeting people’s needs rather than making an increasingly small ruling class obscenely rich. This is a way of seeing society or community as a comment on or measurement of the texture of everyday life. Success here is not about the volume or velocity of money exchanges. It simply cannot be and still be a place for human beings. What if we took time liberated from the less and less soft compulsion of “the economy” to hold inherent value, apart from whether it had been used “productively” under a test created by monopoly capital?

Any organizational system begins, in theory, as a project in the service of human needs. As such systems expand, though, they start to serve themselves and the people who hold power and influence within them, stretching their scope and creating new “needs” that require their oversight and intervention. In Illich’s thought, this is the process through which our institutions become counterproductive. GDP’s monocular focus on scale and output destroys the very domains where human freedom thrives: community, craft, sane proportions. When powerful, centralized institutions come to monopolize core social functions like education, health, and housing, they eventually degrade and displace the capacities they were supposed to support. Their power turns to self-serving and self-perpetuating, expanding its domain leaving people powerless and dependent. For Illich, “professional hegemony at the contemporary scale” was in fact a dramatic historical rupture, a contention “as little allowed for in Marxist critique as it was in liberal theory.” If the Marxists had recognized exploitation and alienation, Illich identified “a deeper alienation,” an alienation from the very possibility of independent thought or action. Cayley observes that during Illich’s lifetime, this kind of thinking about professionals and institutions was not taken particularly seriously on the Marxist left. They shared the capitalists’ gospel of growth and centralization and saw no value in the idea of deschooling or demedicalizing ourselves. The state socialists of the twentieth century became what they fought precisely because they believed that they could use the state instead of abolishing it.

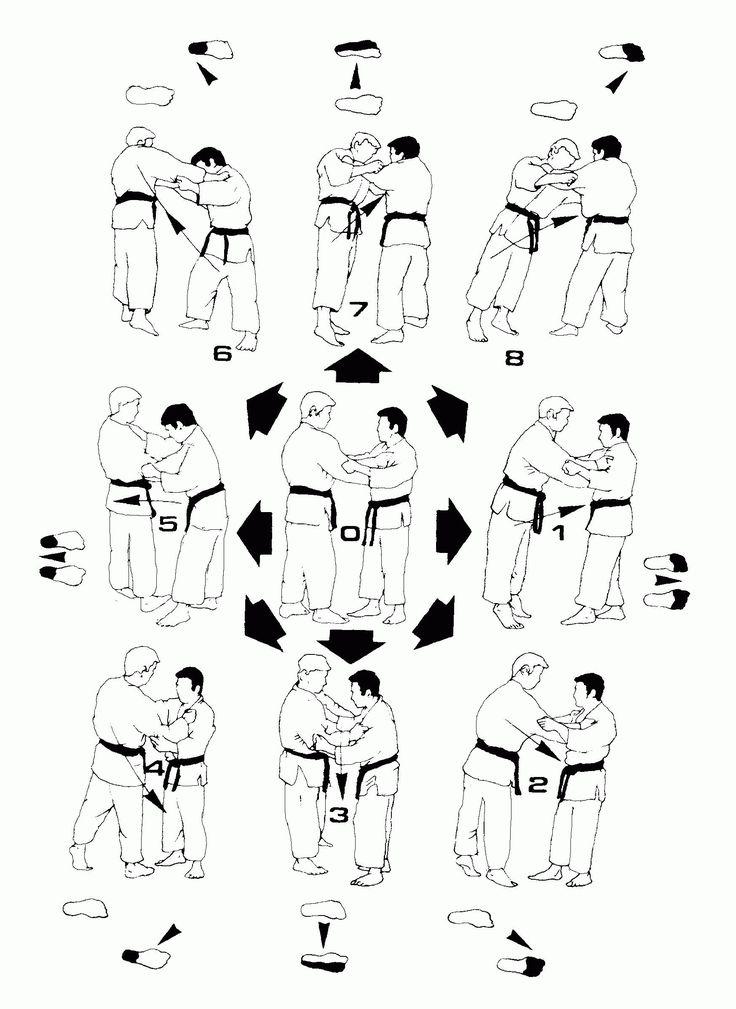

But how could it be abolished? Years ago, always matched with much larger opponents, I learned through the idea of kuzushi to make my opponent’s size and strength his liability, to lean into my advantages. Politically, we need to rediscover this idea rather than continuing with the current approach of accepting both ruling class ideologies and concrete practices. Rather than trying to confront the machine of state-capital directly, playing to its advantages, a kuzushi-informed approach seeks out the soft, weak supports for the structure. I always had to be less concerned with striking than with using the opportunity for leverage at just the right moment. In one explanation of kuzushi I heard, it was described as “a systematic thing that incrementally improves my chances.” I want to home in on those two elements, because they help to explain our task. We have to be systematic, in terms of mounting a consistent challenge within the margins, and we have to be incremental, in terms of continuing to ratchet up our leverage where we have a foothold. The tactical logic here is applicable in politics no less than hand-to-hand combat, where you’re not going to mirror your opponent and their strengths in size and centralized capacity, but to look for the areas where that scale and capacity produce brittleness or vulnerability. Practitioners of kuzushi will exploit those areas with small and well-timed counters or inputs that cause the opponent to throw himself. One can deploy the kuzushi approach in any conflict or negotiation, only by seeing where the opponent cannot stop his momentum from taking him, and sending him there with a thud. The weight transfer you need requires that you choose the moment when his commitment or momentum has locked him in. Those who have been in many such situations know: even though this moment of total commitment may be extremely short, it is a moment of total exposure and thus weakness. As is intuitive, if one wants to apply kuzushi, they have to stay low, and there are both literal and metaphysical registers here. Staying low is one of the most important aspects of the approach, and this is also true in its political analogy; in our political approach, we must remain low in the sense of non-hierarchical, horizontal, nimble, and unpredictable.

The continuing obsession with minutiae and discrete facts, with the doings and sayings of individual politicians, is exactly what we don’t need more of, but remain inundated with. We have always had all of the data we need to address the issues that we must confront today. We have more than enough facts to understand and judge this situation; what is needed is a way to understand and judge it, a theoretical framework that helps explain why tiny ruling classes continue to dominate—regardless of what we have called the various political-economies. What are the contents of the GDPist imagination? Contemporary people have to understand that value and meaning depend fundamentally on scale. This simple fact has been excluded from the political discourse, but it is extraordinarily important to understanding the observable failures of our current authoritarian capitalist social system. People understand the relationship between scale and cognizable meaning in other contexts. When you examine a large wall fresco from a few inches away, your eyes see only small details; stepping back shows a different picture.

Meaning is scale-dependent in that it partly determines which aspects of social reality are intelligible or salient from our standpoint at a given time. Smaller scales reveal details and aspects of individuality, but hide larger-scale patterns and contexts. But at the scales at which we operate socially and economically today, we are far above and outside of the forms of detail and meaning that are consistent with human freedom and flourishing. To me, this is about perception and epistemology. What any given thing means to a human being does always depend on the level at which we encounter it. We are not to proceed beyond this toxic and destructive style of authoritarian politics until we accept the importance of the human scale.

6. What even is progress?

The mid-century English anarchist Herbert Read suggested a very different way of thinking about progress: “What is our measure of progress? And again I answer that it is only to the degree that the slave is emancipated and the personality differentiated that we can speak of progress.” Read’s model, progress as differentiation, stands as a direct challenge to GDP’s idea of progress, which collapses all difference in its reduction of every social and economic question to “did the number increase?”

His progress is focused on the qualitative, the free and unimpeded development of individuals’ personalities, the emancipation of the oppressed, the “richness and intensity of experience.” Talk about a contrast with the politics of today’s corporate uniparty, which insists that your very best bet is the rich experience of facing a laptop for 60 to 70 hours every week of your life. But I digress. The point is that Read’s idea of progress refuses to treat all growth as inherently good and desirable, to ignore questions of justice, equality, and social flourishing. If GDP’s version of progress values only the accumulation of things, whatever they are, Read was concerned with how a society can encourage plurality and foster the development of the thinking person. For Read, progress is reflected neither in material wealth nor military power, but in “the gradual establishment of a qualitative differentiation of the individuals,†the quality of its representative people. What else could it be? Read understood that it couldn’t possibly be the ability to dominate and oppress your enemies, or to accumulate piles of resources; it had to be about the individual reaching their highest potential, cultivating their capacities in mutually beneficial, cooperative relationships. He went even further: “The farther a society progresses, the more clearly the individual becomes the antithesis of the group.” Those words struck a chord with a much younger me, as few of you will be surprised to hear. Read continues: “The true superman is the man who holds himself aloof from the group.”

I see the problematique of GDP as its epistemological compression or flattening, whereby it takes a highly diverse complex of endless possible qualitative distinctions and gives us one value. What does that do to our social and ethical imagination and standards? Well, look around you. What I mean by this is in a very real way, GDPism has redefined what we “know†about our social reality by presupposing that everything is fungible and commensurable. This is both incredibly dull and a vicious attack in some larger metaphysical sense, in that it tries to arbitrarily impose this all-consuming and uniform standard over plural forms of value. It is jarring that anyone would accept this uncritically, but we’re hailed early into an ideology that makes it basically invisible.

The GDP ideology has completely colonized and warped our thought and vocabulary. Remarking on cuts to food stamp benefits last night, prominent cable news access-liberal Chris Hayes framed his complaint specifically in terms of economic growth, saying that food stamps should be protected because they are “classic stimulus,” adding almost embarrassedly afterward that millions of Americans rely on this support to meet their basic nutrition needs. I’m not picking on Chris Hayes here. It could’ve been anyone, and it is everyone. I don’t think he thought about it, which is the point. We all reflexively think in GDP’s terms, use its language, accept its deep hostility to clear thinking, etc. We don’t even know how to defend people not starving here in our country without pointing to the idols of GDP. There’s something pretty disturbing about that to my mind: the whole rationale for giving a human being food is some abstract macroeconomic point about how we actually need the stimulus right now. It is pitiful, and not least because these are our liberals in 2025, totally captured by the most antisocial and unhinged version of capitalist GDPism. When I say that there is one ideology within the ruling class, this is it. GDP above everything – ride or die for GDP. Consider, too, that at this point in time, it’s the liberals who are likely to be far more competent at imposing this brutal and exploitative system.

As we’ve discussed throughout this series, the form of measurement in GDPism isn’t actually neutral, informing how we think about what is happening and what is important. What is happening is that our ruling class has adopted a rotten, corporate-welfarist version of cancerous capitalism that won’t even throw a few promised scraps to the people they have mercilessly exploited for hundreds of years here in America. GDP inverts our values, making us see food as “economic stimulus” rather than, well, food for hungry families. Hayes’s worldview could hardly reflect corporate GDPism more clearly, and it provides us with a good example of what the GDPist ideology is actually there to do: if it seems like it’s there to give us genuine abundance, it is in fact there to upend a human being-centered system of values and ethics, so we can see even food stamps in terms of what they do for some totally abstract measure of “growth” that values weapons of mass destruction in the same way it values cattle and crops. Again, this is only the value system of a rapidly metastasizing cancer. It is GDPist ideology that makes otherwise reasonable people give sociopathic responses like this one, where baseline nutrition has to be treated like it’s valuable only at the abstract macro level.

If it can’t be registered by GDP’s cancer economy, it is treated by our value system as invisible and worthless. Thus the very kinds of social and economic projects we need at the local scale - mutual aid and trust networks, community gardening and farming, Really Really Free Markets, etc. - are treated as worse than marginal. The state and capital have created a system that does not allow you to exit or to generate value in a way they have not blessed and approved, even when doing so would increase your autonomy and welfare. If a group tries to become more genuinely interested in community life, more self-sufficient and less dependent on the GDPist “market,†more attuned to the needs of their neighbors, more free, the measurement system itself punishes this. Most of today’s libertarians don’t talk about this because they can’t see it, and they can’t see it because they share access-liberals’ GDP religion. The model structurally rewards dependence on a centralized state-corporate system and punishes efforts at genuine community engagement and autonomy. It is clearly not a freedom-motivated system, but then it readily admits that — it is a growth-at-all-costs system, and apparently even the partisans of freedom have made their peace with it.

If GDPism is not for freedom, then neither is it for genuine economic competition. There can be no question at this point that GDPism, in contrast to something like a free-market economy, has created and grown a system of centralized, state-connected oligopolies. GDP is a feature of state-managed cancer capitalism, not a spontaneous market freedom predicated on appropriate respect for the individual person. The consistent product of our GDP cult is corporate consolidation that actually undermines the conditions for competition and any kind of market freedom that would serve people, and not only powerful elites. Recent scholarship has confirmed this in empirical terms:

The scholars note, “The share of economic activities accounted for by the largest companies has increased persistently over the past century by all three measures [size by profits, size by sales, and size by assets].” The same group of scholars writes:

In the long-run data, we observe that concentration (measured using the share of assets, sales, or net income of top businesses) has increased persistently over the past century.For example, since the early 1930s, the asset share of the top 1 percent corporations has increased from 70 percent to 97 percent, and the share of the top 0.1 percent has increased from 47 percent to 88 percent.As the largest firms expand, the share of the medium sized firms shrink, while the smallest firms (e.g., the bottom half) always account for a minimal fraction of aggregate economic activities. (emphasis added)

The empirical contours of these phenomena are almost nauseating, pointing to a looming crisis (or many of them). Studies of economic concentration have consistently shown that the profit and profit-share gains of growth under the toxic GDP model also increasingly flow to firms and shareholders as against wages, their smaller competitors, or the broader community more generally. If you can look at the American economy in 2025, with its pervasive government involvement and favoritism and its grotesque concentration, and honestly see it as a legitimate embodiment of human freedom, you should not opine in public.

I wish we had libertarians like Benjamin R. Tucker today, as we desperately need popular commentary that discusses this state-capital system as what it is, an elaborate fraud run by a tiny ruling class straddling the fictional public and private divide. Tucker knew that corporate gigantism is a political creation rather than the natural result of voluntary exchange. Tucker argued that capitalism was not so different from the feudal social order of tribute to warrior-nobles.

As we’ve discussed, under the pre-modern economic system, the role of the dominator, held by the warlord, and that of the exploiter, the one stealing from the farming peasants, were united. The coercive and extractive means were in the hands of particular families/dynasties rather than in an organization like the modern-day state, which pretends to be republican (in the sense of a government that derives its power from the consent of the governed, maintains the rule of law, etc.). The peasant’s experience of paying tribute was not just their tax, coded political today; it was also their rent payment, the equivalent of their credit payment, and so on, coded economic today. In our moment, given the ideologies we’re interpellated into and the concepts we have to work with, we have the deeply mistaken idea that the political and the economic are separate spheres or jurisdictions. Tucker and other anarchists wanted to disrupt this confused thinking, drawing our attention to how capitalism’s change of management operates the system of tribute today.

The tribute system under the capitalists involves a second step, attending the split or mediation that defines the state-capital nexus: it is not that tribute to the economic ruling class has been abolished, far from it, but that it has been formalized and disguised in such a way that it appears to us as voluntary exchange or example of freedom. To Tucker, tribute to capital is a product of state backing for monopolists. These are the most important insights on political economy for our present moment, because they refuse the polite fictions of a government that still acts like the private tool of protection racketeers. The refusal of such fictions, the ideologies of GDP and authoritarianism, ought to be at the center of any serious libertarian project. That our libertarians do not see this is one of many reasons we found ourselves here.

Okay, rant over for a bit.

7. Bill Gates edition