Jon Burke

Successful indigenous Christian anarchism in Taiwan

Part one

Introduction

Is anarchism a practical socio-economic system? How would a modern anarchist society function? Can such a society succeed inside a capitalist state? If you’ve ever considered these questions, you may be interested in this article, which is the first of two describing the 18 year history and success of Smangus, an indigenous Christian anarchist community in Taiwan.

This article will cover these topics.

-

Reliable sources of information on Smangus.

-

The history of Christianity in Taiwan.

-

The origin of modern Smangus.

-

Smangus’ adoption of Christian anarchism.

Reliable sources on Smangus

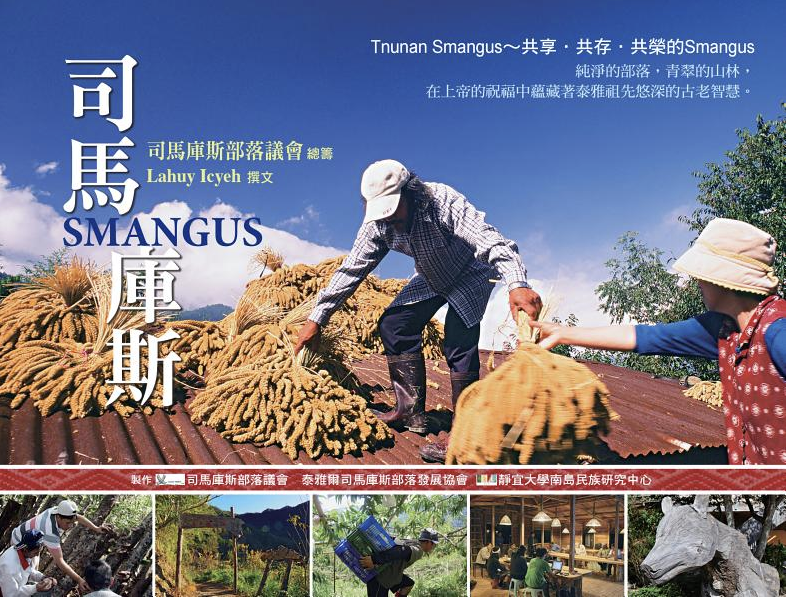

This video is based very largely on the book entitled “Smangus”, written by Lahuy Icyeh, director of the Education and Culture Department of Smangus’ Tribal Council. This is the best primary source for the history and development of Smangus. However, the book’s bilingual text, written in Atayal and Chinese, will be unreadable for many people.

Various academic journal articles, mostly published in Taiwan, provide a scholarly treatment of Smangus from a range of perspectives, such as environmental sustainability, indigenous culture studies, and intentional communities. These resources are reasonably accessible and reliably well researched, but typically have a very narrow focus. The most common and readily available sources of information on Smangus, in both English and Chinese, are travel guides and eco-tourism commentaries. Most of these repeat the same information, which has usually originated from the Taiwan government, or from personal visits by journalists and travelers. However this information is at least typically accurate, even if it isn’t very detailed. See the notes this article for a list of recommended information sources.

History of Christianity in Taiwan

In order to understand the anarchism of Smangus, we must understand its Christianity. Smangus is an anarchist community, because it is a Christian community. Its anarchism was derived from its Christian ethic. Of course, since Smangus is an indigenous community, it was not originally Christian. Consequently, understanding Smangus as an anarchist community requires an understanding of how and why it became Christian, and to do that we need to start with the history of Christianity in Taiwan.

In 1624 the Dutch East India Company established a military outpost, Fort Provintia, in the south of Taiwan. Although some attempts were made to colonize the island, including military oppression of the indigenous people, and the establishment of a rudimentary government administration, trading posts, and an education system, the Dutch military presence was too small and weak to hold more than a third of Taiwan’s territory. The Dutch fought with an even smaller Spanish outpost in the north of Taiwan, which the Spanish abandoned in 1642. The Dutch were almost completely unsuccessful in their attempts to preach Christianity in Taiwan.

Shzr Ee Tan, lecturer of the University of London, notes that by 1650 the Dutch had, recorded only 5,900 conversions to Christianity, many of which were of indigenous people.

By 1650, the Dutch recorded that 5,900 persons had been baptised (Huang 1996: 425), including many aborigines.[1]

After just under 40 years of a precarious existence, the Dutch presence in Taiwan was forced out by Guó Xìng Yé 國姓爺, also known as Koxinga, a warlord from China who invaded Taiwan in 1661 as part of the Ming Dynasty’s imperialist expansion. Christianity was suppressed harshly under his rule; professor Ann Heylen of National Taiwan Normal University writes “Koxinga treated the Dutch missionaries, schoolmasters and their native converts with peculiar severity”.[2]

In time Taiwan was invaded again by the armies of China’s imperialist Qing Dynasty, and Christianity remained suppressed.[3] A small wave of English, Canadian, and Spanish Christian missionaries arrived in the nineteenth century, but made little progress despite some conversions. From 1895 to 1945, Taiwan was colonized brutally by the Japanese, who also ensured Christianity was suppressed.[4]

As a result, by the mid-twentieth century Christianity had made virtually no progress in Taiwan over the last 300 years, and had almost no impact on the local culture. However, this situation changed significantly after 1945. Ironically the most influential wave of Christian missionaries did not come from the West; they arrived as Han Chinese Christians from China. In 1945, General Chiang Kai Shek (蔣中正), of the nationalist Guomingdang (中國國民黨), party lost control of China to the communists and invaded Taiwan, which he established as a base of operations with the aim of one day returning to re-take China. Shzr Ee Tan says that“During this decade there was a surge in evangelical activity”, explaining that European missionaries also started arriving again. Tan further writes “After the 1950s, entire aboriginal villages took up the faith following the strategic conversions of village leaders”.[5]

Of all the various indigenous tribes in Taiwan, it was the Atayal people who accepted it most enthusiastically, and even today around 90% of Atayal are at least nominally Christian. This establishes the background to the origin of Smangus, a modern Atayal Christian anarchist community. The Atayal people, called Tayal in their own dialects, and Taiya in Chinese, are divided roughly into the plains dwelling tribes and the mountain dwelling tribes. Those in the mountains have typically survived by hunting game, and harvesting small crops of millet, sweet potatoes, and mushrooms.

Although Christianity was a religious import, it has been adopted by Taiwan’s indigenous people and incorporated into their own culture. Rather than indigenous people becoming Western style Christians, Christianity in indigenous societies has become localized and trans-culturated. As Taiwan was taken over by the Han Chinese from 1945 onwards, indigenous people who converted to Christianity began to use it to differentiate themselves from the Han Chinese, and applying it as an additional social buffer to resist assimilation into Chinese culture. Professor Xiè Shì Zhōng (謝世忠), an anthropologist at National Taiwan University, writes “That is, Christianity stands as a symbol of power introduced from Western civilization that indigenous peoples appropriated in order to cope with the continuous impact of Han-Chinese civilization”.[6]

This appropriation of Christianity by indigenous people in Taiwan to strengthen their own identity and culture, stands in contrast to the typical historical pattern of Christianity as an exogenous religious force imposed on local cultures which it deforms and erodes.

Origin of modern Smangus

The modern history of Smangus Qalang, called Sīmǎ kù sī (司馬庫斯部落) in Chinese, begins in the 1970s. In this next section I will be relying partly on the brief summary of Smangus’ development written by journalist Angela Lu Fulton, in an article for the World Magazine, published in May 2019. Most of the information will come from other sources I will cite directly, such as the book “Smangus”, written by Lahuy Icyeh, director of the Education and Culture Department of Smangus’ Tribal Council, and various academic works. This section is quite lengthy, but it’s important because it explains the motivation behind eventual Smangus’ adoption of anarchism.

There are several different Tayal tribal lineages and dialects. The people of Smangus belong to the Tayal Mrqwang lineage, and speak the Squliq dialect. For decades their mountain village, 1500 metres above sea level, was without electricity, a phone services, or a main access road. Even now it is one of Taiwan’s most remote indigenous settlements. The village’s economy consisted almost entirely of traditional mushroom farming, using techniques introduced by the Japanese colonizers. Aided by US financial investment, Taiwan was one of the top mushroom producers in the world at this time, ensuring the village a modest but stable income.[7]

This started to change in 1979, when the village finally received an electricity service. However, modernization came at a price. Like many other indigenous communities at the time, as it became more connected with the outside world, Smangus found more of its young people leaving the village to seek higher education and better employment opportunities elsewhere, typically in the small towns and cities at the foot of the mountains. During this time the global mushroom price fell, as Korea and China competed for position in the market.[8]

When its mushroom industry lost value and its income fell, Smangus was severely depopulated by families moving out of the village, to the point that only eight families remained. At this point a new revenue source was clearly needed, and the villagers started to consider participating in Taiwan’s robust eco-tourism industry, which was becoming particular popular among indigenous communities.[9]

It may seem surprising, but eco-tourism was a new idea for the tribe. Contrary to popular belief, Taiwan’s indigenous people do not always live harmoniously with their environment. In fact exploitation and unsustainable land and harvesting practices are not uncommon. Even in Smangus, the villagers had become accustomed to treating their environment with some degree of disregard. In an article in the Taiwanese newspaper Taipei Times, published on 8 November 2004, just after the formation of Smangus as an anarchist community, local resident Tqbil Icyan mentioned that his father “had killed or captured 20-odd bears before he died”. It should be note that such exploitative behavior is contrary to the Atayal people’s traditional gaga, the tribal mores and ethical principles which govern individual behavior, in particular such activities as hunting. Tqbil Icyan added that he interpreted his father’s death from a fall in the mountains as a punishment for his exploitative hunting of the bears, saying “We believe those bears killed by my father avenged their death”.[10]

In the same article, Taiwanese writer Wu Chih-ching spoke of the casual way villagers killed local wildlife during his visit to Smangus in 1989, saying “When I first visited Smangus 15 years ago, Atayal people shot birds to treat me”. He went on to say “I told them if they want to attract more visitors to this remote village, they had to protect wild animals”.[11] Tension remains between government attempts to preserve endangered species, and indigenous determination to continue traditional hunting practices. In the last couple of centuries, animals such as the Formosan deer and Formosan clouded leopard were hunted to the brink of extinction by indigenous people, and some of these animals are still hunted today by local tribes.[12]

While Taiwan’s Wildlife Conservation Act of 2016 states “Wildlife may be hunted or killed for traditional cultural or ritual hunting, killing or utilization needs of Taiwan aborigines”, it lays down specific conditions under which this can take place, conditions which indigenous hunters can be prone to disregard.[13] However, there are still indigenous hunters who predominantly use traditional methods of hunting such as snares and bows and arrows, and follow strictly their tribe’s restrictions on hunting behavior.

The year 1991 was a pivotal moment in Smangus’ history. Village leader Icyeh Sulung had a dream in which he believed God said he would send many people to the village, to restore its fortunes.[14] Interpreting this as divine confirmation that Smangus was to restart its economy on the basis of eco-tourism, Icyeh investigated the area’s potential, and discovered a nearby grove of giant cypress trees. Over the next couple of years, Smangus revived its economy by marketing itself to tourists as an exotic isolated mountain village with unique environmental assets.[15]

At this early stage, Smangus’ tourism promotion capitalized extensively on its indigenous identity, promoting the village as an exotic and otherworldly location, untouched by modernization and offering an experience with ancient primitivism. Somewhat ironically, the villagers made extensive use of historical stereotypes of indigenous people in their advertising. A paper on tourism development in impoverished communities by Dr Benxiang Zeng, notes that at this time leaders in Smangus deliberately marketed the village to tourists with terms such as “dark tribe”, “Xanadu”, “last pure land”, “primitive” and “misty mountain”. Whether this should be described as cynical or simply practical, is a matter of personal opinion.[16]

This strategy proved enormously financially successful, but came at a social cost. After a main access road was finally built in 1995, Smangus found itself overrun by tourist traffic beyond the capacity of its infrastructure.[17] In a book on biodiversity conservation in China and Taiwan, Dr Gerald Beath and Dr Lěng Zé Gāng note that during the Chinese New Year holiday in 1997, “1200 tourists in 500 vehicles entered Smangus”. Beath and Lěng describe the tourist’s impact as overwhelmingly negative, saying they “carved initials on the cypress trees, invaded village plots and homes, and left piles of garbage”.[18]

In addition to tourist management challenges, internal conflicts also arose. Dr Benxiang Zeng notes that opportunities to participate in the tourist economy were unevenly spread throughout the village. Families with more land were able to provide more services, and thus secure a greater share of income, while villagers with fewer assets to convert into tourist attractions, were financially disadvantaged. Competition for tourist dollars caused inter-personal tensions.[19] Zeng also describes how the attraction of tourist income led some households to “develop extra activities in the forest and/or to build more lodgings, many of which were unlawful, improperly designed/planned, and less safe”.[20]

As Smangus became a well known tourist attraction, it also became a tempting prize for developers looking for their next opportunity for the exploitation and capitalization of rural land. Despite being offered huge cash incentives, village leader Icyeh Sulung refused to sell any of the land, insisting that it had been given to the tribe by God, and was the rightful inheritance of the following generations. Organized crime gangs also attempted to obtain land, by attempting both bribes and threats, but were also rebuffed strongly.[21]

Although Smangus was enjoying financial security, its prosperity was unevenly distributed throughout the village, it was vulnerable to external pressure, and it was suffering from internal tensions. At this point, village elders took the initiative to propose a radical restructuring of the entire community.

Smangus adopts Christian anarchism

By the late 1990s, tribal leader Icyeh Sulung had already been suggesting the idea that Smangus’ economic assets be redistributed to a cooperative organization, and owned collectively by all the villagers. This proposal gradually gathered sufficient momentum to prompt action at the turn of the millennium.[22]

However, Iceyh’s motivation was not simply economic. He was convinced that the disharmony in Smangus had a deeper cause, both ethical and spiritual. The village’s sudden access to wealth had incited materialistic desire, and the unequal distribution of that wealth had engendered envy, jealousy, and division. As a Christian, Iceyh would have recalled to mind various relevant passages from the New Testament, such as 1 Timothy 6:10, which reads thus.

1 Timothy 6 (New English Translation):

9 Those who long to be rich, however, stumble into temptation and a trap and many senseless and harmful desires that plunge people into ruin and destruction.

10 For the love of money is the root of all evils.

A number of other villagers agreed with Iceyh. A paper by Drs Goang-Jih Horng and Chun-Chiang Lin, examining the intersection of culture and eco-tourism at Smangus, comments on the village’s situation at this time, writing “From the residents’ points of view, the problems of the tourism management were actually religious problems”, adding that they saw their local church as the key to resolving their internal conflict.[23]

But this response was not a matter of simply exhorting people to Christian charity, or making pious speeches about the importance of spiritual virtues. Iceyh decided that the village should go beyond the idea of just starting a cooperative business, and restructure the entire community of Smangus, taking inspiration from the socio-economic organization of the original first century Christians. In her article on Smangus, journalist Angela Lu Fulton cites village elder Yuraw Icyang, who “remembers all-night meetings where they discussed creating a communal system based on the early church in Acts 2”.[24]

That’s talking about a passage in the Bible. The book of Acts is the fifth book in the New Testament, and the end of the second chapter contains a description of the earliest Christian community. Acts chapter two verses 44–45, read thus.

Acts 2 (New English Translation):

44 All who believed were together and held everything in common,

45 and they began selling their property and possessions and distributing the proceeds to everyone, as anyone had need.

This is an explicit description of a Christian collectivist community, with common ownership of property, and egalitarian provision for the needs of all its members. Citing this passage in her article “Anarchy: Foundations in Faith”, professor Lisa Kemmerer says “The Book of Acts portrays early Christian communities as communal, like the ideal anarchist communities described by Berkman, Proudhon, and Chomsky”.[25] In his work “Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism”, published in 2008, Dr Peter Marshall likewise cites Acts 2, commenting “There are solid grounds for believing that the first Christian believers practiced a form of communism and usufruct. The account in Acts is explicit”.[26]

Another New Testament passage in the same book, Acts 4:32, repeats this description of the earliest Christian community.

Acts 4 (New English Translation):

32 The group of those who believed were of one heart and mind, and no one said that any of his possessions was his own, but everything was held in common.

In his book “All Things in Common: The Economic Practices of the Early Christians”, published in 2017, Roman Montero says “what Luke seems to imply by writing “and no one claimed private ownership of any possessions” in Acts 4:32 is that this was taken literally”, adding “the Christians really did treat property as though it really was common and no one claimed ownership over their own property”.[27] Montero goes on to describe this as “a community that looks exactly like “communism” in the classical Marxist sense of the word – where all property is owned collectively – without actually having collective property”.[28]

There are at least 1,500 different cooperative businesses in Taiwan, in fields such as finance and banking, consumption, public utilities, and agriculture, so the residents of Smangus had plenty of local examples of successful coops which they could have imitated. However, their inspiration was not secular, but explicitly Christian. They sought a solution which would re-integrate their community on the basis of their shared religious and spiritual beliefs, and consequently turned to a successful historical model which was representative of their faith and true to their Scriptures. The extent to which their organizational structure is best described as anarchism, as opposed to communalism, mutualism, collectivism, or something else, is certainly a matter for discussion, and will be covered in the second article in this series. For now, let’s continue with the narrative of their decision and how it was implemented.

Lahuy Icyeh records that “In 2001, a total of 16 couples from eight families formed a joint management group”, and that by 2003, “most of the tribe’s members were participating in the collective management group”.[29] Providing more detail, Dr Benxiang Zeng writes that “in 2001, a communal operation system emerged”, during which time “The community established the Association for Development of Atayal Smangus and Kalan [sic, for Qalang]”.[30]

Writing for Taiwan Panorama magazine, journalist Oscar Chung says that in 2001 the villagers “began cooperatively supplying food and beverage services to tourist visitors, sharing the income among everyone involved”, noting that in the next year “this concept was extended to accommodation”.[31] The transformation of Smangus into a Christian anarchist community was further advanced in late 2003, during which time Lahuy Icyeh writes that nine tribal representatives traveled to a kibbutz in Israel, to study an active model of collectivism. Lahuy says “After returning home, they continued to hold intense discussions over how to collectivize {the village’s} privately held land”.[32]

On 14 September 2003, further discussions were held on the topic of land ownership, and representatives of various households signed up to an agreement on land and property collectivization.[33] Discussions of how to implement the new land ownership system continued to 5 January 2004, at which point a new organization was formed, named Tnunan, the Tayal name for weaving.[34] By this time, Lahuy writes, seven village members had originally joined, but later withdrawn. At this point there were now 48 salaried individuals in the collective, and its organization was becoming increasingly well developed.[35]

The next article in this series will describe in detail how the Smangus community was organized, how it operates currently, to what extent it can be described as anarchist, and its current and future challenges.

[1] Shzr Ee Tan, Beyond “Innocence”: Amis Aboriginal Song in Taiwan as an Ecosystem (Routledge, 2017), 107.

[2] “Koxinga treated the Dutch missionaries, schoolmasters and their native converts with peculiar severity. There is a dispute among scholars over the reason why Koxinga implemented such harsh and repressive measures against the Christians.”, Ann Heylen, “Missionary Linguistics on Taiwan: Dutch Language Policy and Early Formosan Literacy (1624–1662),” in Missionary Approaches and Linguistics in Mainland China and Taiwan, ed. Wei Ying Gu (Leuven University Press, 2001), 238.

[3] “Early Christianization took a back seat to the taking of Taiwan by Koxinga in 1662, and later, the Qing.”, Shzr Ee Tan, Beyond “Innocence”: Amis Aboriginal Song in Taiwan as an Ecosystem (Routledge, 2017), 107.

[4] “Christianity was placed under strict surveillance by the Japanese (1895–1945).”, Shzr Ee Tan, Beyond “Innocence”: Amis Aboriginal Song in Taiwan as an Ecosystem (Routledge, 2017), 107.

[5] “After 1945, a larger wave of Christian resurgence took place with the migration of Christians from China to Taiwan as a result of expulsion by the Communist party. During this decade there was a surge in evangelical activity, especially in the despatching of missions from Switzerland, Italy, North America and China. After the 1950s, entire aboriginal villages took up the faith following the strategic conversions of village leaders.”, Shzr Ee Tan, Beyond “Innocence”: Amis Aboriginal Song in Taiwan as an Ecosystem (Routledge, 2017), 107.

[6] “That is, Christianity stands as a symbol of power introduced from Western civilization that indigenous peoples appropriated in order to cope with the continuous impact of Han-Chinese civilization.”, Shih Chung Hsieh, “Tourism, Formulation of Cultural Tradition, and Ethnicity: A Study of the Daiyan Identity of the Wulai Atayal,” in Cultural Change In Postwar Taiwan, ed. Stevan Harrell (Routledge, 2019), 194–195.

[7] “Lacking electricity, phone lines, or a road, the Smangus tribespeople during the 1970s lived a simple agrarian life growing mushrooms, millet, and sweet potatoes.”, Angela Lu Fulton, “Sharing Spaces in ‘God’s Tribe,’” World Magazine, 9 May 2019, https://world.wng.org/2019/05/sharing_spaces_in_god_s_tribe.

[8] “Annual exports of canned mushrooms peaked in 1978 at US$120 million, before Chinese and South Korean growers ate into Taiwan’s share of the global market.”, Steven Crook and Katy Hui-wen Hung, “Fungus Among Us: The History of Mushrooms in Taiwan,” The News Lens International Edition, 29 January 2017, https://international.thenewslens.com/article/60211.

[9] In the Smangus village, which received electricity in 1979, 20 families decided to leave after the price of mushrooms fell. Only eight families, including Yuraw’s, stayed behind. They continued their agrarian lifestyle but began to hear of another revenue source for aboriginal tribes: tourism. Angela Lu Fulton, “Sharing Spaces in ‘God’s Tribe,’” World Magazine, 9 May 2019, https://world.wng.org/2019/05/sharing_spaces_in_god_s_tribe.

[10] “My father had killed or captured 20-odd bears before he died,” says 23-year-old Tqbil Icyan of his father Icyan. While he died 20 years ago after a fall from a transport cable linking two mountains, the tribe believes the bears had their revenge. “We believe those bears killed by my father avenged their death,” Tqbil says. The Atayal today see greater benefits from sparing the wildlife and tracking down tourist dollars instead. “‘Smangus Is God’s Tribe’ — Taipei Times,” 8 November 2004, https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/feat/archives/2004/11/08/2003210239.

[11] “When I first visited Smangus 15 years ago, Atayal people shot birds to treat me,” says writer Wu Chih-ching. “I told them if they want to attract more visitors to this remote village, they had to protect wild animals,” adds Wu, who has advised on improvements to the villages. The Atayal followed his advice but the transformation to eco-tourism was not without problems. “‘Smangus Is God’s Tribe’ — Taipei Times,” 8 November 2004, https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/feat/archives/2004/11/08/2003210239.

[12] “In other words, although not hunting for self-consumption or cultural rituals, with excellent hunting techniques, the indigenous people threatened the wild animal population out of economic gain.”, Liao Amanda, “The Balance Between Taiwanese Indigenous People’s Hunting Rights and Wildlife Conservation | 關懷生命協會,” trans. Yi-Hsin Liu, 11 January 2019, http://www.lca.org.tw/ennews/7027.

[13] “Wildlife may be hunted or killed for traditional cultural or ritual hunting, killing or utilization needs of Taiwan aborigines, regardless of Article 17, Paragraph 1; Article 18, Paragraph 1; and Article 19, Paragraph 1. Hunting, killing or utilizing wildlife in the condition listed above shall be approved by authorities. The application process, hunting method, hunted species, bag limit, hunting season, location, and other regulations shall be announced by the NPA and the national aborigine authority.”, Taiwan Wildlife Conservation Act of 2016 | Article 21–1, https://law.moj.gov.tw/ENG/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?pcode=M0120001#:~:text=Taiwan%20aborigines%2C%20in%20violation%20of,less%20than%20NT%241%2C000%20and.

[14] “Just after falling asleep that night, half-awake and half-asleep, {tribal leader} Icyeh heard a voice speaking to him in Atyal. The voice was very clear: “The future of Smangus will be as lively as Baling. There will be so many people that the land itself will shake”.”, Lahuy Icyeh (拉互依.倚岕), 司馬庫斯SMANGUS (中文.泰雅語版) (中華民國政府出版品, 2011), 58; translated from original Chinese text to English.

[15] “Icyeh sent villagers to search for tourist attractions on their land, and they found a grove of ancient, 115-foot-tall cypress trees 3 miles from the village. By 1993, the Smangus were inviting media to write about the isolated tribe and its giant trees, and soon tourists started coming up the mountain on foot.”, Angela Lu Fulton, “Sharing Spaces in ‘God’s Tribe,’” World Magazine, 9 May 2019, https://world.wng.org/2019/05/sharing_spaces_in_god_s_tribe.

[16] “Taking up leadership, local elites led Smangus starting to market local natural resources as tourist attractions. Some “branding” keywords including “dark tribe,” “Xanadu,” “last pure land,” “primitive,” and “misty mountain” had been identified and advertised (Huang 2014).”, Benxiang Zeng, “How Can Social Enterprises Contribute to Sustainable Pro-Poor Tourism Development?,” Chinese Journal of Population Resources and Environment 16.2 (2018): 6.

[17] “Once a government-built road opened in 1995, tourists flooded the village, overwhelming its feeble infrastructure. Most residents had never dealt with tourists before, and the village didn’t have enough toilets or trash cans.”, Angela Lu Fulton, “Sharing Spaces in ‘God’s Tribe,’” World Magazine, 9 May 2019, https://world.wng.org/2019/05/sharing_spaces_in_god_s_tribe.

[18] “In the Chinese New Year celebration of 1997 alone, 1200 tourists in 500 vehicles entered Smangus. They carved initials on the cypress trees, invaded village plots and homes, and left piles of garbage.”, Gerald A. McBeath and Tse-Kang Leng, Governance of Biodiversity Conservation in China and Taiwan (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2006), 2.

[19] “In 2000, in order to meet the continuous influx of tourists, tribal households started to build more B&B facilities. Very soon, the intense competition between businesses led to a benefit conflict within the community (Tang and Tang 2010; Huang 2014). Community members with relatively ample capital resources and better capacity to provide lodging facilities took advantage to benefit more from tourist visitation. This triggered complaints from those in relative disadvantage.”, Benxiang Zeng, “How Can Social Enterprises Contribute to Sustainable Pro-Poor Tourism Development?,” Chinese Journal of Population Resources and Environment 16.2 (2018): 6.

[20] “Moreover, the motivation to attract more tourists to their owned and/or managed facilities encouraged the individual households to develop extra activities in the forest and/or to build more lodgings, many of which were unlawful, improperly designed/planned, and less safe (Tang and Tang 2010).”, Benxiang Zeng, “How Can Social Enterprises Contribute to Sustainable Pro-Poor Tourism Development?,” Chinese Journal of Population Resources and Environment 16.2 (2018): 6.

[21] “Wealthy developers also showed up with suitcases of cash and offered to buy a plot of land for $1.6 million. Icyeh turned them down: “This is the land God gave us to steward, so we need to pass it down to the next generation.” Members of Taiwan’s triads, or mob networks, also tried to buy the land, even threatening to kidnap the tribespeople’s children if they refused to sell.”, Angela Lu Fulton, “Sharing Spaces in ‘God’s Tribe,’” World Magazine, 9 May 2019, https://world.wng.org/2019/05/sharing_spaces_in_god_s_tribe.

[22] “When Icyeh Sulung, who was village chieftain at the time, saw all this, he became worried for the community’s future, and felt there was a need to find a new model that could restore unity. Thus the idea of establishing a “co-op” started to ferment in Smangus in the late 1990s, and at the start of the new millennium, under the leadership of the old tribal chief, members of the community set about putting the system into effect.”, Oscar Chung, “Cooperative Community — The Renaissance of Smangus,” ed. 光華畫報雜誌, trans. Phil Newell, 台灣光華雜誌2018年8月號中英文版: 智慧台灣 Taiwan Panorama 43.8 (2018): 79.

[23] “From the residents’ points of view, the problems of the tourism management were actually religious problems; therefore their resolution was to position the church in the tourism management and embodied the qalang that was only a vague symbol in original.”, Goang-Jih Horng and Chun-Chiang Lin, “Tourism Landscape, Qalang and Nagsal-A Study of the Relationships between Culture and Common-Pool Resource Management at Smangus, Hsin-Chu,” Journal of Geographical Science 37 (2004): 52.

[24] “Yuraw remembers all-night meetings where they discussed creating a communal system based on the early church in Acts 2.”, Angela Lu Fulton, “Sharing Spaces in ‘God’s Tribe,’” World Magazine, 9 May 2019, https://world.wng.org/2019/05/sharing_spaces_in_god_s_tribe.

[25] “The Book of Acts portrays early Christian communities as communal, like the ideal anarchist communities described by Berkman, Proudhon, and Chomsky:”, Lisa Kemmerer, “Anarchy: Foundations in Faith,” in Contemporary Anarchist Studies: An Introductory Anthology of Anarchy in the Academy, ed. Randall Amster et al. (Routledge, 2009), 206.

[26] “There are solid grounds for believing that the first Christian believers practised a form of communism and usufruct. The account in Acts is explicit:”, Peter Marshall, Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism (PM Press, 2009), 76.

[27] “However, what Luke seems to imply by writing “and no one claimed private ownership of any possessions” in Acts 4:32 is that this was taken literally; the Christians really did treat property as though it really was common and no one claimed ownership over their own property.”, Roman A. Montero, All Things in Common: The Economic Practices of the Early Christians (Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2017), 52.

[28] “In this way, you could have a community that looks exactly like “communism” in the classical Marxist sense of the world – where all property is owned collectively – without actually having collective property.”, Roman A. Montero, All Things in Common: The Economic Practices of the Early Christians (Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2017), 52.

[29] “In 2001, a total of 16 couples from eight families formed a joint management group. The collective management consisted of three projects: restaurants, shops, and villas. By 2003, most of the tribe’s members were participating in the collective management group.”, Lahuy Icyeh (拉互依.倚岕), 司馬庫斯SMANGUS (中文.泰雅語版) (中華民國政府出版品, 2011), 72; translated from original Chinese text to English.

[30] “To address these issues, in 2001, a communal operation system emerged. The community established the Association for Development of Atayal Smangus and Kalan {sic, for Qalang} (as Association thereafter) that incorporated eight businesses (Huang 2014).”, Benxiang Zeng, “How Can Social Enterprises Contribute to Sustainable Pro-Poor Tourism Development?,” Chinese Journal of Population Resources and Environment 16.2 (2018): 6.

[31] “In 2001 they began cooperatively supplying food and beverage services to tourist visitors, sharing the income among everyone involved. The next year, this concept was extended to accommodation.”, Oscar Chung, “Cooperative Community — The Renaissance of Smangus,” ed. 光華畫報雜誌, trans. Phil Newell, 台灣光華雜誌2018年8月號中英文版: 智慧台灣 Taiwan Panorama 43.8 (2018): 79.

[32] “In August of that year {2003} the Taiwan Presbyterian Church, with the assistance of the government, sent nine tribal representatives {of Smangus} (Amay, Yumin, Masay, Silan, Batu, Amin, Yuraw, Loyang, Ikwang) to a kibbutz in Israel. After returning home, they continued to hold intense discussions over how to collectivize {the village’s} privately held land.”, Lahuy Icyeh (拉互依.倚岕), 司馬庫斯SMANGUS (中文.泰雅語版) (中華民國政府出版品, 2011), 72; translated from original Chinese text to English.

[33] “On the evening of September 14, 2003, in response to the “15th discussion meeting on land ownership”, each representative of the participating households went to the blackboard to affix their signatures, expressing the consensus of all participants in the “land ownership” and their willingness to participate.”, Lahuy Icyeh (拉互依.倚岕), 司馬庫斯SMANGUS (中文.泰雅語版) (中華民國政府出版品, 2011), 74; translated from original Chinese text to English.

[34] “The land ownership conference concluded on 5 January, 2004, and after voting on eight possible Atayal names for the organization, the participants settled on the name “Tnunan”, and then spent a lot of time discussing the “meaning and implications of Tnunan”.”, Lahuy Icyeh (拉互依.倚岕), 司馬庫斯SMANGUS (中文.泰雅語版) (中華民國政府出版品, 2011), 74; translated from original Chinese text to English.

[35] “At the same time, {2004} 48 salaried people participated in the event. The “Tribal Convention” and “Tnunan Norms” were established this year. During this process, seven members joined but withdrew.”, Lahuy Icyeh (拉互依.倚岕), 司馬庫斯SMANGUS (中文.泰雅語版) (中華民國政府出版品, 2011), 78; translated from original Chinese text to English.