Joseph Parampathu

Prison Labor: Capitalism Without Markets

Understanding the Economics of Totalitarian Institutions

Background and Statement of the Problem

Parsing out markets and capitalism

Markets without capitalism and capitalism without markets

How do markets affect capitalism or modify it?

To what extent is capitalism influential on the economics of prison labor?

Political ecologies and philosophies of prison labor

Prison labor’s acceptance by the general public

Prison labor compensation and reproductive work

Analyzing the production of prison industries and their role in the capitalist economy

How do prison labor managers decide which items to produce?

How are prison labor contracts awarded?

Labor and industry forces and their effects on prison labor

The future of prison labor: where is it going from here?

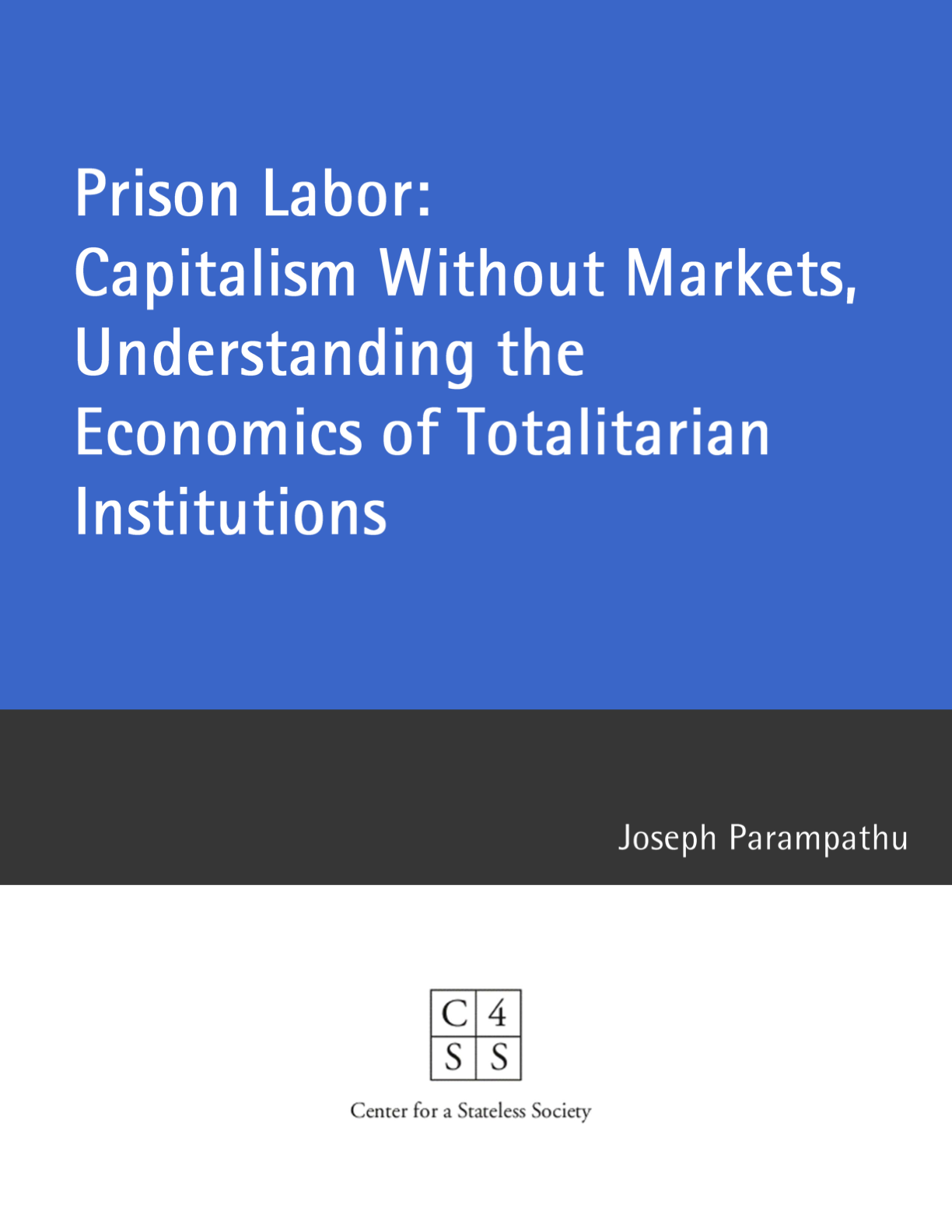

Figure 1: FPI Annual Financial Reports

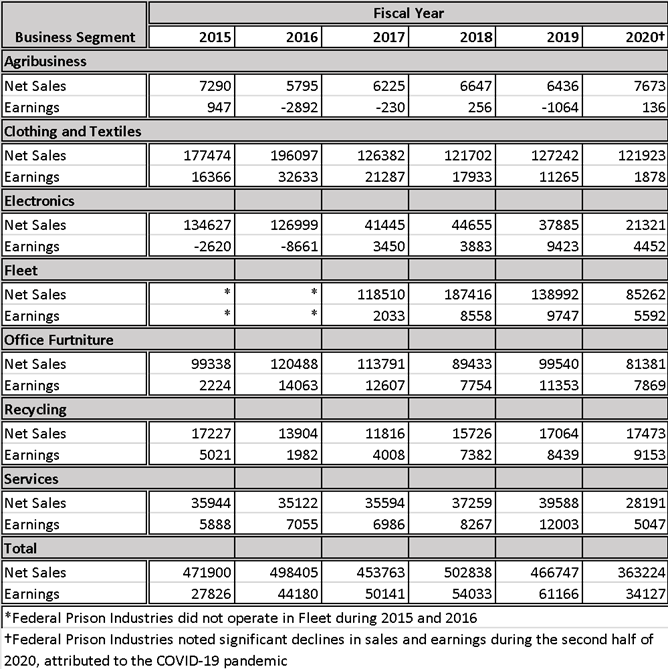

Figure 2: Analysis of Estimated Value of Prison Labor

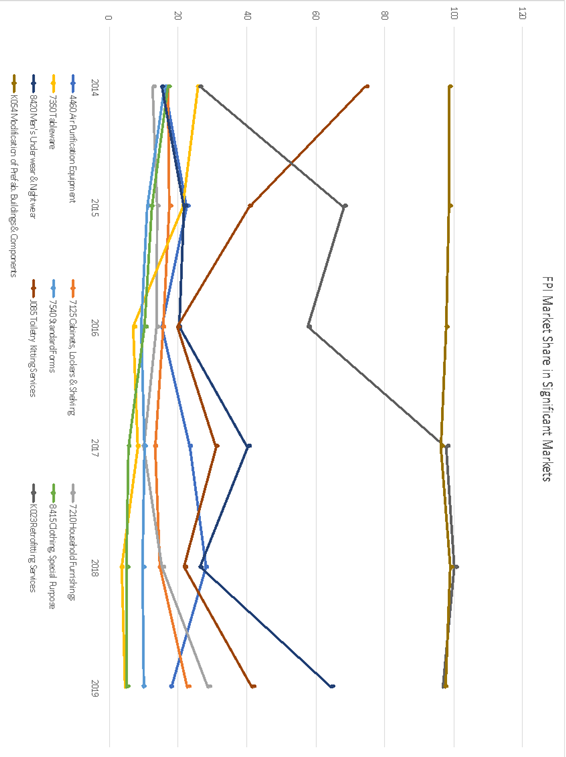

Figure 3: Chart of FPI Market Share in Significant Industries , ,

Figure 4: Line Graph of FPI Market Share in Significant Industries

Abstract

Prison labor remains a paradox in many ways. Simultaneously sparsely studied or recorded, and ubiquitous; derided by labor unions and free workers as unfair competition and lauded by businesses as the only way to insource labor at the globalized price point; rehabilitating prisoners through the virtue of work, while punishing them through that same work— prisons are in many ways the ultimate reflection of capitalism with the veneer of smiling faces removed. Prisoners work not to avoid starving or to have a place to sleep, but because it is a requirement of their existence. In the United States, all federal inmates must work, and those who refuse face severe penalties including being charged exorbitant sums to reimburse the government for the pleasure of being incarcerated. Prison labor remains anomalous to labor under traditional market forces, but exists within, and remains largely dominated by, the larger economies and politics that govern its existence. The prison is the final destination for the person-become-commodity that is the poor laborer. Those unable to afford the offramps to a prison sentence end up serving time and, once there, the institution of the prison attempts to keep them as an employee for life.

The unsavory nature of prison labor as an economic force has relegated prison labor to only the most dangerous and unwanted jobs in existence, for wages far below market value, and insulated from any claims to benefits, time-off, or workplace safety protocols. Politically, the prison labor industry in the United States has found its niche in attempting to return outsourced jobs to the domestic market, in effect, moving the colonies of American empire right into its own backyard. Without the economic differential power of sweatshop wages in low-income countries, prison wages become only marginally better than no wages, particularly when factoring in the many deductions that prisons apply for court fees, supervision costs, and even disciplinary functions. While these economic factors play a defining role in determining the realities of prison labor, they exist within a larger philosophy of prison life that is, ultimately, capitalistic. Even where the economics of prison labor bears literal resemblance to market demands, prison labor remains a necessary component of the philosophy of capital’s primacy over the labor pool. Insulated from the market, the totalitarian prison becomes the end-stage of capitalism; with contradictions uninhibited by class conflict and protected from the bargaining power of labor, prison work is the harbinger of what “free” work becomes as the capitalist fantasy continues.

Background and Statement of the Problem

What is prison labor?

In the case Vanskike v. Peters, the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals examined the issue of whether a prisoner, Vanskike, could sue the Illinois Department of Corrections for payment under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) for labor he was forced to perform on behalf of the prison where he was held. In coming to its conclusion, the Court felt it necessary to examine the “economic reality” of the relationship between Vanskike and the prison. It found that while, like an employer, the prison did hold hiring and firing power, supervisory control over his schedule and working conditions, and determined his pay, these factors were incidental to the totality of control that prisons have over prisoners. His relation to the prison was primarily as its captive, not as its workforce. While employers of free laborers have obligations to their employees under the FLSA as a consequence of the employment contracts they make and the control these contracts assign employers over employees, the Court determined that Vanskike’s relationship to the prison was entirely different. Vanskike had not contracted with the prison to provide his labor to it. On the contrary, he was compelled to work for the prison in service of meeting their regulatory burden to “equip such persons with marketable skills, promote habits of work and responsibility and contribute to the expense of the employment program and the committed person’s cost of incarceration.”[1] In fact, the Court reasoned, the Thirteenth Amendment enumerated an exclusion for prison labor that implied prison labor was in fact “involuntary servitude, not employment.”[2] The Court continued that, because a prisoner’s standard of living was guaranteed by their prison-employer, their standard of living was not tied to their ability to pay and thus a substandard wage, or no wage at all, could be justifiable. Before concluding however, the Court further considered that prison labor at below minimum wage represented an unfair advantage to prison industries in a market regulated by FLSA standards for wages. The Court concluded that this issue carried to its logical conclusion would require all prisoners to be provided similar wages and labor standards as free labor, but that this issue had been significantly mitigated by legislation which specifically prescribed restrictions on prison labor’s economic role.[3]

But if prison labor is involuntary servitude, as opposed to employment, is it still work? Surely, Mr. Vanskike considered the cleaning, kitchen work, and knit shop work he did to be work, even if it had been involuntary. He expended labor energy and was less able to labor for his leisure or to exchange his labor with others within the prison. Though the court was prescient to note the prison’s control over him was total and that they could have denied him all other opportunities to profit from non-sanctioned (or even all voluntary) efforts, the work that Mr. Vanskike did is without a doubt economically necessary work. The prison could not have functioned properly without janitorial services or kitchen work, and if that work were not performed by prisoners, then the prison would have needed to search for that labor elsewhere. The economic dimension of prison labor exhibits market tendencies but exists within the larger framework of the total institution of the prison-prisoner relationship.

Of course, the Seventh Circuit Court in examining Mr. Vanskike’s petition came close to bridging a much more fundamental question. What would have happened if the Court determined that prisoners were required to receive consideration for the work they perform in prisons? If the FLSA were applied to the prison labor pool, then that prison labor would have entered the market on relatively equal footing with free labor. Distinctions of market/non-market are fully encapsulated by questions of where the boundaries between regulated/unregulated, paid/unpaid, legitimate/illegitimate lie. The Court’s decision to mark prison labor as outside the market is what ensures that it is non-market work. Yet, the Court itself acknowledged that the labor within prisons is regulated. It acknowledged that this labor is governed by the legislature’s decision-making regarding the economic effects of prison labor on the larger economy when prison-made goods enter the market. Further, it admitted that the prison’s choice to force Mr. Vanskike to perform prison work was a choice not to employ a free laborer to perform that same work (employment that would have been required to meet FLSA standards).

Prisons claim that prison labor performs a rehabilitative function, providing prisoners with job skills that would otherwise deteriorate in idleness and allowing for a productive diversion from the boredom of the prison environment. While these may all be functions of prison labor, the economic function that prison labor plays within the prison environment is equally fundamental. As the Illinois legislature noted, prison labor exists, in part, to offset the costs of incarceration.[4] Even these other prison functions (such as management, rehabilitation, diversion, etc.) bear an economic component: when the prison instructs a prisoner to work, it takes up their time which otherwise would require programming such as classes, training, or care.

While prisons may be relegated to a regulatory gray area, this graying of the market/non-market boundary may be more common than otherwise presumed. Whether the economics of law act as a market encapsulating all market/non-market distinctions, or the legal framework acts as the final delineator between markets and non-markets may be a matter of perspective. Examining these gray areas of employment law, Professor Noah Zatz considered this “paid non-market work” and its constant push and pull from laborers and employers to classify the work as within or outside “the economy” as central to questions of employment law in this space.[5]

Labor within and on behalf of prisons, such as the janitorial and kitchen work which prisoners perform to contribute to the continued functioning of the prison, represents only a portion of all prison labor. Prisons additionally operate programs where they provide prison labor to certain private industries, often for a fee. These arrangements allow free employers to substitute their own laborers for prison laborers which they lease from the prison.[6] Generally, prisons also provide the supervisory and line management roles in these work assignments, as well as performing any other administrative personnel functions that employers would have to cover for free laborers. Federal Prison Industries (operated under the trade name Unicor) is the government corporation which controls federal prison labor in the United States (each state also runs its own state version as well). Prison Industries offers attractive options for private factories to move within the walls of government prisons. With facilities often created or supported by the prison itself, private companies can take advantage of the same total control that typifies the prison labor environment. Prison Industries boasts on its website about the fact that it is completely “self-sustaining” in that it does not result in budget deficits which burden the taxpayer and sells itself as an attractive program for “reshoring” labor from developing markets back to the United States by recreating sweatshops in the “developed” world.[7] In this accounting, the costs of imprisonment are considered sunk costs, irrelevant to prison industries which rely on them to operate.

The courts have held that prisoners are not employees but perform prison work as a penological condition of their sentence. But just because prison work is punishment, and not a voluntary employment contract with an employer-prison, is work performed within the prison not due consideration? If it is not, why have prisons bothered to provide wages at all, even those far below prevailing rates for similar free labor? When prison legislators argue that prison labor helps offset the cost burden of incarceration and prevents the levying of large debts on prisoners to pay for their own imprisonment, are they simply misapplying market characteristics to non-market work or are they correctly perceiving prison labor’s functions within a larger ecosystem of grayed markets? When Federal Prison Industries boasts the ability to bring jobs and manufacturing back to the United States, provide captive labor pools to potential employers, and to reduce the burden on state agencies to pay for supplies, is this simply a marketing gimmick or is it properly placing prison labor as another tool in the economy of state power competition and an effect of larger global economic forces?

This position of prison labor as both inside and outside of wage labor is analogous to the feminist critique of unpaid and paid domestic labor. Where it is paid, it is paid little and treated with little respect, and especially where it is unpaid, it acts as a drain on the ability of women to take part in other labor, for personal benefit or for exchange. Dalla Costa conceptualized this differential power of social and work determinants as the basis of wage slavery.[8] As housework is devalued, the undervalued work remains a requirement for the functioning world, and the workers who do housework are impoverished by taking part in it.[9] Similarly, prison labor, even when it accomplishes necessary productive goals and produces equal goods or services, is devalued by its position as unpaid (or low-paid) labor. The prison laborers’ work is devalued, and their position in the bargaining relation is artificially depressed. This private expropriation of labor becomes a means not just for extracting resources, but for reducing social relations to the means by which they service capital.[10] Prisoners lose access to labor that otherwise would be able to support their social networks in their communities, or themselves, and instead must subordinate their relations to the needs of capital. If their work is not valued by the prison labor economy, then their labor power cannot be transferred to their family or community, and likely the additional strain of their position will act as a net drain on that part of their network that remains outside of prison.

In impoverishing prison laborers, the prison industry enacts a sort of primitive accumulation whereby it robs labor power from people and uses them as a raw resource input into its final goods and services. Instead of this labor power being available to prisoners for personal benefit or exchange, their labor power is expropriated, or “extruded,” such that prison laborers are exploited to a point beneath subsistence.[11] This labor power becomes privatized as solely the property of the state, and is dispensed into the market or removed as needed. These needs change with the tides of the larger economy as well as the goals of the state power. States attempt to control markets as the mechanism by which capital accumulates, and prison labor remains a key component of this market regulation and manipulation.

What are markets?

A definition of the term “market” remains elusive. While the term is used to mean both a place in which exchanges occur, such as “the marketplace of ideas” or to “bring goods to market,” these terms become more difficult to pin down when we attempt to define what is not the market or what is outside the market. One line of reasoning argues that the market entails all things and nothing exists outside the market. If the market is where we exchange things or ideas, then the only things that are outside the market would be those which are unexchangeable or immutable. But to define the market in this way assumes a sort of inherency which is unacceptable to the question at hand. When we determine what lays outside the market we are constrained by the abilities of privatization and the existing technology. While it may have been at one point inconceivable that bands of airwaves or access to a person’s unused personal vehicle or home could be sold on the market, now that the technology exists to do so, these things regularly enter the market domain. Likewise, we might expect that things which are currently not fully commodified, such as clean air or air pollution, might in time become part of the market domain, if the tendency towards privatization reaches those spaces. Even where states attempt to fully delimit market boundaries, areas of illegitimate exchange exist at the peripheries. Both where regulation has not yet caught pace with trend or technology, and where widespread use remains elusive, gray markets can thrive even over long-term periods involving complex actors and relationships.[12]

Karl Polanyi, in response to the early work of Ludwig von Mises and Fredrich Hayek described the relationship of markets to states using the term “embeddedness.” [13] Polanyi understood market liberalism to represent an ideological force on the global stage that worked to disembed markets from states, and allow markets to perform the work of equalizing inefficiencies through competition—what might be colloquially referred to as “unfettered capitalism.” While Polanyi did not disagree that markets were an efficient means of allocating prices to scarce resources, he felt that such a proposition was unlikely to be effective as long as states continued to maintain spheres of influence. Polanyi examined the way in which the institution of an international gold standard for currency exchange significantly advanced the goals of market liberals but also produced profound effects on the daily lives of ordinary people, resulting in a strong backlash which led to growing economic protectionism and empire building amongst the newer world powers, culminating in the rise of fascism and the world wars.

Polanyi argued that disembedding the market from the state was difficult because the costs to the interests of people living within those states was too great for them to bear, and to successfully achieve this end would require a complete annihilation of existing social bonds and a complete commodification of society. Polanyi argued that instead of allowing global liberalizing forces to inflict this change upon them, people of these nations tended to react strongly and even violently to maintain economic stability, even for the cost of inefficient markets. Polanyi’s work remains an important basis for many of the environmental questions regarding property rights, norms, and responsibilities as they affect divisions of nature today and helps provide a framework for conceptualizing prison labor’s position within market systems.

Thus, in defining markets we should be aware of the ways in which social and governmental norms affect the realities of what exists within the market domain and what it is that constitutes markets. When we consider “intellectual property” within the current space of digital rights management technology, we may find that property claims which in the past were difficult to enforce are now an inescapable reality with rights-holders able to control access and reproduction throughout the life of digital products. Further, understanding that these norms are both reflections of and formative on current thinking, we can be aware that changes in these norms can just as well lead to a movement of these same property claims to “outside” the market if they are no longer deemed to be properly property claims.

In exploring the realm of prison labor we confront these same difficulties of what is and is not reality, and wherein cause and effect truly lie. When the state determines that prison laborers are not required to be compensated because their labor is part of the rehabilitative process of prison life, or the punitive functions of criminal justice, or even that the transformative power of work is a means of training and self-improvement, are those exchanges outside the market and therefore irreducible to monetary value? Is it impossible for a person to receive both monetary and non-monetary benefits from their labor? A cursory review of the realities of labor, and particularly labor which is paid below market rates, shows that people commonly work for reasons that are not purely financial, and yet still take financial considerations in making these decisions. When someone chooses to perform work for their spouse or their family, or to provide their labor as part of a religious obligation, or to perform mandatory government service, they can in many ways be said to be receiving non-monetary benefits (even if the benefit is simply avoiding state sanction), and further we see that free labor is often coercive, even when it provides some monetary benefit to the laborer.

Is prison labor within the market because it is used to create goods which are then sold on the market and indistinguishable from other goods? When prison labor remains wholly a self-contained affair, with prisoners performing the maintenance, cleaning, and cooking of prisons, is this labor outside the market even though the only alternative for the prison would be to acquire these same services from free laborers, presumably at the prevailing wage? While prisoners are under the complete control of the state, they remain able to, and often do, moderate their level of resistance, the enthusiasm of their work, and their own productivity. Federal Prison Industries claims to be an industrialist’s utopia, free from the bargaining power of laborers, but prison work stoppages, strikes, and individual acts of resistance remain the norm in the prison environment.[14]

Examining prison labor as it exists, we see markets today playing an important role in moderating prison labor while also seeing prison labor (moderated by the many levers of government repression required for its existence) itself performing a function that moderates the market. Following Polanyi’s work, the market remains thoroughly embedded within the “non-market,” and the state’s actions in moderating prison labor performs both a role in controlling the power of markets to regulate prices of labor and goods, and remains largely affected by and even controlled by similar tracks of the economics of labor and goods outside of the prison’s sphere of influence. Prison labor remains simply another locus of interaction between the market and the state where we see a graying of the openly-regulated market and the unregulated market.

Unlike in pre-industrial markets, wherein exchange occurred mostly as a form of reciprocity, capitalist exchange requires a dehumanizing of the individual. Pre-capitalist markets, while they contained an exchange element, were social interactions as much as financial ones.[15] While these social interactions may have acknowledged differences in status or class between individuals, as well as the relative scarcity and need of goods, the purpose of the exchange was largely to strengthen relationships, even when the purpose of the interaction was intentionally harmful.[16] On the other hand, capitalist exchange treats all actors as objects to be exploited for gains in exchange value. Even in an employment relationship, neither the capitalist nor the worker is humanized by the exchange of wages and labor. While the tendency of capital to accumulate may insulate many capitalists from economic annihilation, the capitalist who finds himself in poverty lacks the status that the nobleman in poverty could never have lost.[17] The forces of creative destruction in capitalist societies treat impoverished former capitalists with the same ruthlessness afforded any other actor. Without the value of bringing goods to market, the former price-setter becomes the price-taker and is forced into the final position of selling their own labor and, in effect, themselves.

As the privatization of commons removed subsistence from the reach of the non-working poor, exchange markets became the sole place for these people to make a living, through the sale of their labor to capitalism. In this new economy, the buying and selling of humans took on a renewed character as they formed a primary resource necessary for the production of exchange profits.[18] It is within this form of exchange-driven market, or capitalist market, that the forms of prison labor must be examined in its current light. The prison labor pool remains a raw resource within the prison industry economy, as well as a means to control the supply of labor within the larger free economy (through increased incarceration), and a means to control the flow of available work (and thus wages) to free laborers.

Parsing out markets and capitalism

Markets without capitalism and capitalism without markets

Some use the terms market and capitalism interchangeably, or at least without much regard to any distinction between the two terms. Working towards a precise definition of the delineations between markets and capitalism or at least a picture of where these terms are considered to overlap or not is essential to determining the extent of market influence on and by prison labor systems. Both markets and capitalism play interrelated and powerful roles in interactions between people and goods that can have a defining effect on the way that people operate in the world. Within capitalist systems, as people engage with commodities, money, capital, or labor through the process of selling or buying them on the market, the market plays a “mystifying” role in determining their ability to relate to these as symbolic commodities or as real objects of value.[19] In this way people become alienated from the experience of production and find it more difficult to affect the processes that lead to this same alienation—they are transformed into the consumer, one who only purchases commodities but does not sell them (or appears to forget their role as a seller). This experience is felt on an individual basis by all actors in the market, even those who collude to work together as trusts or corporations, when they engage with the larger market.[20] While naturally each person is expected to be an uninformed trader on the market (one who is not properly able to appraise the market value of a particular commodity), financial capitalism defines efficient markets as those which perform the function of correcting discrepancies between actual prices and proper market prices by quickening the pace by which informed traders can profit from uninformed traders.[21],[22]

As far as entities or systems can be said to interfere with the proper pricing of commodities to prices, we would say that they are interfering with the efficiency of markets. In this way, it is possible that capitalism interferes with market efficiency in particular markets. This role can be seen most starkly in the way that capitalism can reify the bounds of sanctioned markets and non-sanctioned markets, thereby artificially increasing the prices of certain marketable commodities and artificially lowering the prices of others.[23] Polanyi defined labor as one such “fictitious commodity” for which markets can only exist when the commodity market is created by capitalism.[24] In the sense that capitalist production concentrates the aims of economic forces into the production of commodities for sale on the market, as opposed to for personal use, capitalism works to serve the market.[25] Even within this narrow sense, however, capitalism distorts markets to ensure that they are those markets which subsequently work to serve the ends of capital. That is, as long as markets work to enshrine the primacy of capital, those markets will be preserved and bolstered by capitalism, while markets which threaten this primacy are weakened or suppressed. Within the capitalist market, fictitious commodities can be treated as commodities for the purposes of market exchange, even if the production of these commodities no longer reflects any relation of the reality which that commodity represents to personal consumption. Within the total state of the prison system, the capitalist market demands the extraction of the fictitious labor-commodity, even when that commodity bears no relation to the needs of those within prison walls. For the capitalist market to exist and be profitable, it must suppress the diversion of that labor-commodity to other means such as prisoner action or personal exchanges of favors. This labor-commodity is then sold into the “outside” market through its transformation into the real commodities which are produced in prison factories or through the exchange for service contracts with outside agencies and subsequent trade on the open market.

In attempting to describe and delineate capitalism, Fernand Braudel described the control, monopolistic and oligopolistic, of capitalists over capital and the flows of legitimated exchange as the defining characteristic of capitalism, and one that is not just divorced from the need for market systems, but which purposefully suppresses market systems to ensure its primacy.[26] For capitalists, and for capitalism, markets remain a threat to the ideology of capital. Where prices are able to self-regulate through open exchange between like parties, and ownership claims are subject to competing interests, rent-seeking capital has little power. When we examine the world as it is today, we see a world that contains both capitalism and markets, oftentimes both existing in tandem and in opposition, both intertwined and segregated from each other.

How do markets affect capitalism or modify it?

Where markets and capitalism coexist, and particularly in the areas where they interact closely, their interactions cause fundamental changes to the organization of capital and markets. Within capitalist systems dominated by private property ownership, and in which the power of capital performs a rent-seeking function, skewing prices in favor of further capital accumulation, markets work some counter-capitalist effects upon the larger system. When capital defines that which is within it, it also defines that which is outside of it. As capital measures labor or goods that are used in the production of further goods for commerce, these goods are valued within capitalism. Thus, work done by a domestic worker in the home for exchange is productive labor, by the metrics of capital, while the same work done by an uncompensated family member is not. Those things which are not valued remain outside of capitalism, even when they might represent a market, in the sense that they remain governed by exchange decisions. Thus, when people exchange goods within a de-legitimated process, such as the illegal transfers of labor or goods between inmates, that labor or good may remain within the market, subject to exchange pricing, and yet remain outside of capitalism—both unmeasured and invisible. From the perspective of capital it is valueless and therefore non-existent. Further, things may remain within capitalism but fall outside the market when competing claims to title result in an effective freeze on market potential. The item remains untradeable and unusable, removed from the market in the service of legitimating capital’s ownership scheme.

Insofar as market forces enable the flow of goods to achieve pricing equilibriums, they work as a limiting factor on the influence of capitalism. Where market access remains a prevailing factor in the flow of goods and services, capitalism is less able to leverage inequalities in financing or knowledge to distort market values. Further, the flow of goods and services towards market equilibrium exerts a cost on the manipulation of markets that asserts power over this flow away from capitalism. While liberal theorists have held this democratizing effect of the market to be superior to any distortionary effect of capitalism on prices over broad spans of time in the overall economy, others have acknowledged how maintaining the regulatory effect of markets requires, in many cases, access to commons or other non-capitalistic functions such as sharing and informal exchanges, which capitalist norms actively devalue.[27]

Markets without capitalism

Markets operating without capitalism provide a medium for the exchange of goods and services without including the ownership schemes and socialization of losses that typifies a capital-serving economy. In its most basic sense, these markets exist in the pockets of freedom where capitalism has not yet found ways to intrude. Among the unbanked, in areas where police and government enforcers are absent or rare, and within intimate social settings such as family groupings or cohabitants, various forms of exchange thrive without the encroachment of capital interests.

Comparing a capitalist market to an anti-capitalist market, we see the ways in which capitalism engenders the subject’s own self-policing of capitalist norms as well as the ways in which a person can resist these same forces.[28], [29] For market anarchists, markets without capitalism provide opportunities for class conflict to operate through the market to achieve egalitarian ends. Some market anarchists and left libertarians hold that the state’s existence, and its work with and on behalf of capitalist interests, provides the overall result of empowering capital at the expense of the proletariat. As a whole, the government’s net actions towards the proletariat are negative, and it works to use the proletariat’s labor power to indirectly enrich capital through the off-loading of infrastructure, social, and environmental costs onto the public.[30]

In non-capitalist markets, where ownership is not enforced through the state’s monopoly on violence, but rather one’s personal force and the societal forces of communal acceptance to those claims, ownership follows more closely to possession rather than title.[31] While non-capitalist market actors perform controlling functions through their social interaction and self-policing, which has the potential to re-formulate pseudo-capitalist relations, these pockets of state failure in policing provide significant opportunities for market systems to grow unencumbered by capital.[32]

In describing the aspirational market, the one that does not currently exist, but which market anarchists attempt to create, some have used the term “freed” markets to mean those markets which allow for exchange but do not necessarily support capitalist relations (which they argue will fall apart without that missing state support).[33] From a normative standpoint, these theorists argue that markets which provide competitive spaces for labor and underprivileged groups are encumbered by state forces, while moneyed interests enjoy protected monopolies, and that markets ought to be “freed” from these burdens. In the absence of the monopolistic power enforced by the state, such as through property paradigms, rent-rewarding, and socialized costs to capital, these theorists argue that capital will be weakened by this competition and a more democratic economy will result. Thus, Charles Johnson has described this freed market as “the space of maximal consensually sustained social experimentation.”[34] Though the prison environment is quite removed from these spaces of consensual experimentation, even within the confines of the totalitarian prison, pockets of freedom still allow prisoners to experiment with each other in spontaneous and creative ways.

Capitalism without markets

If market anarchists are in favor of a system of markets without capitalism, the opposite of their desired system may be termed “capitalism without markets.” As it is used here this term may mean systems wherein capital maintains a dominant position and controls the flow of value, but where competitive forces that might check the power of capital have been wholly removed through monopolies on force. We might describe this scenario as similar to totalitarian states where private interests still maintain control of both the government and the flow of value, but wherein many aspects such as labor, property disputes, etc. are concentrated in central seats of power. Even in these totalitarian systems, in the real world, we tend to see pockets of market forces arising, not just in markets for goods and labor, but in markets for subversive ideas, social relations, and resistance organizing as well.

Prisons resemble this type of totalitarian capitalism without markets and, similar to totalitarian states, even in prisons some subversive markets do exist with prisoners illicitly trading labor, social debts, ideas, and knowledge between themselves. The diversity of resistance is a testament to the lengths to which these totalitarian regimes will go to maintain control. From the perspective of capital as a control mechanism, and capitalism as a system through which all things are placed in the service of capital, capital and capitalism are self-reinforcing. Capitalism provides the means of using capital control to further empower capital, transforming ownership of past wealth into increased future wealth. Then, capital is further used to beat down anti-capitalist forces and strengthen the control mechanism as a function of the capitalist system. For capitalism as a system, the market may be seen as a hindrance, allowing free agents to transact in ways that act counter to capitalist interests. Within this view of capitalism, we can envision certain forms of capitalism arising which have succeeded in removing market power from the system.

This work presents the prison profit center as a place in which the market has been sharply removed or controlled by capitalist forces, to create a pocket in which capitalism can be said to exist without markets. For prisoners within the prison labor regime, there is no ability to refuse work, to choose between more than one employer, or to prioritize the spending of earnings as one sees fit. Within prisoners’ ability to spend the portions of their earnings not garnished for court fees, victim restitution, or prison fees, prisoners are severely constrained in that there remains only a smattering of sanctioned vendors. The captive is both the prison workforce and also the prison’s captive market.[35] The prisoner’s family becomes a source of wealth extraction for the prison and its various contracted services. The prisoner’s free time becomes a resource to be mined and sold to their own families by the minute or second.[36]

In this sense, the prison can be seen as a source by which capitalism engages in primary accumulation, looking to social interactions, leisure time, and other behaviors which are normally not sources of exchange, as a means of profit. The prison forces families apart, increases the costs of providing labor value to members outside the prison, and increases the costs of receiving goods from outside the prison. Then, it uses this increased cost as a means to extract wealth from prisoners and their families. The prison creates the dilemma and then forces its prisoners to pay to have those dilemmas resolved. By impoverishing these people, the prison accumulates primary wealth and degrades the lives of prisoners.

Even as prisons act as totalitarian institutions insulated from market forces, they still operate within a state that responds to market forces, and are affected by policy which is often a reaction to the same market forces. As economic downturns lend themselves to increased incarceration as a means of hiding surplus labor forces and ameliorating middle class fears about potential loss in class privilege, prisons end up swelling with the bodies of the underclass. When prisons rack up high costs and are unable to provide rehabilitation or even space for prisoners, policy forces end up working to reduce prison populations as a means of protecting the overall prison system even through decarceration.[37] This survival mechanism to contain the costs of the totalitarian pockets of prison regimes acts as a market force preventing the unbridled growth of these institutions. These forces may point to the ways in which prisons are not wholly outside market forces, and how totalitarian institutions may be affected by market forces, including those forces within the spaces of social experimentation that work against prisons and prison labor regimes.

To what extent is capitalism influential on the economics of prison labor?

From the very beginning of American experiments with prison labor, economics played a driving role both in the formation of prison labor practices and in the philosophies behind those who run prisons as profit centers. The Pennsylvania system first subjected inmates to a period of complete isolation, with no comrades, no diversions, and no interaction. After this period, the inmate was slowly introduced to work (within their cell, alone) to which they tended to take immediately as a boon compared to the total idleness of their previous state. This contrasted with the New York system of isolated sleeping quarters with a day of congregate factory work. In the end, the economy of the combined factory system won out as prison wardens vied to prove they each had the most productive prison factory, with little concern for reforming prisoners into enthusiastic workers.[38] While prison labor decisions were driven by economic factors, prisons themselves remained largely focused on maintaining control over prisoners, with labor production itself remaining far from the prime goal. As work introduces codependency into the prison-prisoner relationship, however, the prisoner’s bargaining power relative to the prison increases.

While even free employment relationships rarely involve exchanges between parties with equal bargaining power, laborers do maintain a certain level of control over labor purchasers. Likewise, the movement to make prisons profit locations requires a subsequent shift in power in favor of prisoners. As prisoners begin to work, their work becomes a clearly necessary function of the prison’s output, both when the labor performed is solely within the prison and when it is used to create goods that will be sold in the open market. Without the prison laborer, the prison factory or prison field does not produce, and in failing to compel prisoners to perform this work, prison administrators are considered failures both in the secondary goal of prison production and in the primary function of maintaining control over prisoners. Even when prisoners receive no wage, the prison-as-profit-center comes to require prisoner work to function, and becomes dependent on the compliant prisoner for its own operation.

The need to maintain the tenuous relationship of control between prisoner and prison administrators, as well as their shifting bargaining powers within the economic reality of an exchange relationship such as prison work, requires prison guards and supervisors to engage with prisoners through informal means of accommodation as a means of moderating their own dependency on prisoner cooperation.[39] This shifting locus of power between the institution and its captive labor-commodity is central to the economics of prison labor and its management. Further, as the wages paid to prison laborers remain largely under the control of the prison industry itself through required remittances, penalties, and prison banking institutions, the prison laborer also represents a form of consumer-commodity, where the prison laborer can be compelled to spend their wages back into the prison industry’s pockets. Even in this form, as a captive consumer, the prisoners’ position can provide an additional source of power over the prison regime, which requires prisoner cooperation if it is to operate at a reasonable cost.

Within modern capitalism, financial innovation tends towards attempts to privatize the ownership of services and information which either previously existed in the public domain or were provided as a public service by a government entity. This allows for the extraction of profits through increasingly socializing the costs of production and empowering rent-seeking by cleaving otherwise public resources from the public.[40] The financialization of management leads to policies which further the relationship of capital to production, with a constant push towards more capital accumulation and increased wealth extraction from the same (often limited) resource pool. Prison labor, as an institution, sequesters the labor-power which would otherwise be available to the prison population for use in their own ventures for self-improvement, family support, or collective action. By privatizing this resource and claiming it as the property of the prison industry (at a cost passed-through to the public by governments), prison labor performs the dual function of weakening its labor class (prisoners) and appropriating that labor-power for private capital. While varying schemes have provided for that private capital to remain within government control, these funds are then funneled back into the continued effort to extract labor-power from later prisoners. By taking on capitalist functions such as profit-production, government entities take on capitalist form. This function of capitalism as extracting power from labor is not simply a byproduct of financial capital, but a necessary prerequisite of maintaining the dominance and primacy of capital.[41] This primacy of capital to dominate markets is the defining characteristic of modern capitalism as a mode of control and production.

In prisons, this movement for capital dominance is further regulated by a desire to maintain control over prison populations and to use prisons as a beacon of the control that capital and government maintain over the larger free laboring population as well. Prison labor production is substantially affected by forces in the free economy and in particular by views regarding prison labor as competition against free laborers’ wage demands and an economic advantage in competitive labor markets.[42] As US prison industries have targeted work that had formerly moved to foreign sources of cheaper labor, labor turns from a right not afforded to prisoners (in times of poor economic outlook for free laborers, where the increased labor competition could foreseeably lead to civil unrest) to one of patriotic duty (within the larger function of increasing national productive output). Whether this repatriation of jobs into federal prisons is economically efficient for the global financial system requires further analysis but, as a means of competition between states (particularly ones with large prison populations), prison labor remains important for the economic and political position of states. By ensuring that prisons are not just areas of work, but areas where work is required, states ensure that the base requirements of capitalism are met and that no laborer can escape the grips of capital’s dominance. The existence of prison labor tells the free laborer that capitalist production cannot be escaped, and that capitalism will maintain its grip even where compelling a person to work may not have been sustainable in an efficient market. The underclass of prison laborers becomes the foundation upon which all other labor markets are built; the warning to free laborers: Don’t fall in!

Within this framework of political means for perpetuating economic production, modern capitalism acts as a force to moderate government for economic ends through political control.[43] In this way, government, partially insulated from market economics through its coercive use of state power, is manipulated as another resource mined by capitalists. Just as prison labor represents a labor power appropriated for prison industries, government becomes another resource to be exploited, one which in turn is used as a tool to further its own exploitation, both of the prisoner class and the free laborer. Thus, prison labor performs both economic functions and noneconomic functions. It can be financially important for states attempting to regain footholds in certain industries or planning to expand market share in industries deemed too dangerous or unsavory to fit within the regulated system available to free laborers. When environmental, labor, or safety regulations make it economically infeasible for free laborers to perform these functions, prison laborers can act as a labor pool of last resort—always available and maximally expendable.

Prison labor resides at the outskirts of the legal protections afforded to free laborers, and thus can be exploited by governments to ensure that their own regulations do not get in the way of their economic or strategic goals. This positionality of prison labor in relation to free labor, in a sort of edge-city where regulations on capital are loosened and restrictions on people are tightened to ensure the relatively privileged status of the residents who take on non-prison labor, is an important factor in the economics of prison labor. While it may be simple to think of prison laborers as the lowest rung of paid workers with semi-steady employment, their exploitation works both to enrich the free laborers who enjoy the goods and services produced in prisons (or the lowered cost of government services subsidized by prison work), as well as to impoverish free labor as a collective force by providing a contingent labor force so weak as to be virtually unable to refuse work (and, in fact, to be legally compelled to perform it).[44] For the struggling free worker, the concept of tough-on-crime policies removing labor competition in the free labor pool may even seem a welcome helping hand providing respite from an overly competitive labor market.

Because of the relatively low labor cost associated with prison labor, prison industry production is somewhat insulated from labor cost as a production factor.[45] Major economic factors that influence the distribution and goals of prison industries instead tend to involve decisions regarding in which industries prison labor is permitted to take part and the quality and types of labor output that can be reasonably expected to be derived from prison workers. Prisoners face barriers to accessing sensitive documents such as financial information or personal information and prisoners are generally limited in their ability to use the internet or interact with the public, which limits the industries in which prison labor can feasibly be used. Further, prisoners’ work is constrained by the security environment of the prison and the varying lengths of their sentences. Labor productivity in prison industries appears to be about one fourth that of free labor industries, a factor attributed to the tendency of prisoners to be less suited than free laborers to their jobs, the lack of incentives for prison laborers to expend more than a minimally acceptable level of effort in their work assignments, the incentives for prison administrators to overstaff prison laborer jobs in the hopes of showing full-employment of prisoners, and the increased costs associated with a work environment heavily impacted by security concerns. Prison work is often subject to unpredictable starts and stops to count all prisoners, search the premises, or accommodate changes in prison guard staffing. Prison industries are reluctant to invest capital into machinery which may be vulnerable to sabotage in a prison strike or work stoppage event, and prisons place heavy limitations on the availability of tools to inmates, particularly those in high-security environments.[46]

From the perspective of prisoners, the competing goals of prison industries to both provide prisoners with gainful employment (that can provide them useful, transferable job experience) and to be a robust economic driver that does not compete with free labor, result in some unfortunate consequences.[47] Prison work tends to be focused in industries that are disappearing from the free labor environment (because expanding into those industries does not pose a political burden for prison industries), that are uneconomical under normal regulatory conditions for free labor (such as processing of dangerous or toxic materials), and which are likely labor intensive but capital deprived (because both the labor costs in prison industries and the tendency towards capital expenditures are minimal). Thus, prisoners tend to perform work that is no longer useful for finding employment in the free labor economy and for which the employment prospects are poor or nonexistent.

From the perspective of prison management, prison labor has been conceptualized as a useful means of diverting prisoner attention and energy away from efforts to collectivize or resist control.[48] Within the psychology of imprisonment, the idle prisoner represents a source of constant danger. In fact, in some prisons where official management has turned over control almost entirely to prisoners, prisoners have built up robust internal social governance strategies and engage in meaningful and vibrant work in self-management and productive labor.[49] Prison labor performs the work of social control within certain prison management techniques. This social control aspect performs a further function in turn for the larger “free” economy by revealing to the free worker both the privilege and precarity of their own position. By symbolically showing the free worker that their position is privileged relative to the prison worker, the free worker can be further appeased that their own situation is not so miserable, while simultaneously being pushed to consider the possibility of an alternative working condition that would be comparatively worse and remains ever present.

A model for penal systems as labor institutions presents incarceration as a state adjustment to the unemployment rate. Incarceration allows the state to remove workers which may otherwise be unemployed and shift them into the prison population. Because workers that would be unemployed may be instead hidden within the prison population, there is a causal effect of imprisonment on the unemployment rate, and because incarceration effectively removes the prospect of employment from the incarcerated, even if they would have sought work, there is an “accounting effect” of imprisonment on the unemployment rate.[50] Thus, states may use incarceration as a way to alter or hide unemployment, though one should note that higher incarceration has been linked to long-term increases to unemployment as incarcerated individuals find difficulty in searching for employment after release. Further, because imprisonment tends to be concentrated in those classes most vulnerable to unemployment, the hidden unemployment of people in these classes (namely, the poor, the non-dominant races, or those with lesser job prospects) plays a larger role.[51] States which utilize incarceration in this way can present a rosier picture of equality of opportunity while hiding the inequality behind prison gates. Prison labor, within the context of imprisonment as a labor institution, places the prison worker outside of the labor pool (in that they present no danger to increasing the measured unemployment rate in the immediate term), while compelling them to provide productive output. The prison laborer is the perfect worker from a bureaucratic standpoint because they are not a worker at all, but a factor of production, the raw material of the labor-intensive industries which concentrate in the prison industries.

Prison labor acts to preserve the capitalist “system” by both putting a damper on rising wages and expanding the labor pool to include the vast prison populations, and to preserve the capitalist “order” by ensuring that labor remains not an act of liberatory transcendence, but one of subservience to capital.[52] The maintenance of both the capitalist system and the capitalist order provide a service to capitalism that may not be easily measured through traditional economic measures. The effects of this service may instead be more apparent in the overlap between poverty and crime, the tendency of policing to concentrate in areas of poverty regardless of the prevalence of crime, and the ways in which criminal records increase the precarity of the workforce, particularly in low-wage work.

Research Question

The research question which this paper attempts to address is: How do totalitarian institutions respond to economic forces and reorient themselves to meet capitalist objectives in a dynamic economic environment. How do prisons exert economic force upon prisoners and use economic coercion to control their populations? How do we conceptualize prisons as part of our larger economic systems? This paper will aim to provide a framework for understanding prison labor as part of the capitalist order, and as a necessary component of maintaining the primacy of capital over labor. The study will analyze the ways in which prisons expropriate labor value from their captive workforce and how this theft is necessary for the functioning of a prison system. The study aims to quantify the value of the prison workforce as a means of showing the power that prisoners may be able to wield over prisons when they successfully withhold their labor, and the possible effects on prisons if required to properly remunerate that labor.

Literature Review

Political ecologies and philosophies of prison labor

Of the eight metrics used by sociologist Charles Logan to measure prison performance, three bear particular importance to prison labor strategies: order, activity, and management.[53] Varying philosophies of prison labor have attempted to meet these goals through work. While these competing philosophies have fallen in and out of fashion amongst scholars, these philosophies have also contended with political forces from outside prison walls which bear considerable power over the administration of large-scale prison policies and decision-making of upper-bureaucrats.

In many ways the science of prison management is preoccupied with minimizing the deleterious effects of imprisonment on a prisoner’s ability to reintegrate into society. While prison administrators tout supposed ties between inmate participation in prison labor programs and lower recidivism, these ties have been called into question.[54] Due to the primacy of security in all matters of prison management, the nature of imprisonment is one in which prisoner needs have little bearing on their actual experience with incarceration. For prison managers, prison labor may be seen as a useful tool for avoiding and mitigating the damaging environment of prison by giving prison workers the opportunity to escape into the dull productivity of the prison factory or shop floor. Correctional officers play the part of production supervisors, and prisoners play the part of workers. To the extent that they receive remuneration for their work, prisoners can feel a sense of relative autonomy with the ability to pay for their own modest indulgences or to send meager amounts to relations on the outside to help maintain the fragile social bonds that imprisonment destroys. While these considerations are subordinate to the practical financial incentives that drive prison industries, the experience of being broken down to the point that this labor can be seen as a respite from the danger or tedium of prison life is an essential role of the prison system in socializing prisoners to the systems of work that are available to them within the capitalist order.[55]

Prison labor for order

While prison labor manages prisoners within prison, it also manipulates workers outside prison walls to maintain order there. Pat Timms, as Vice President of Operations at Escod, a company that moved some of its manufacturing to prison laborers, noted that by marketing the move as a means to keep jobs from going overseas and ensuring that the production sent to the prison was of the least desirable quality (the most labor intensive, and the most subject to wildly shifting consumer demands), Escod was able to convince its free laborers to largely accept the decision.[56] There are similarities between this model of flexible labor pools using prison labor and the flexible prison labor contracting force on which Japan relied in the late nineteenth century.[57]

Prisons use prison labor to maintain order within prison institutions. While prison labor is neither voluntary, nor beneficial for inmates, it may remain a welcome escape from the terrors of prison life deprived of meaningful choices. Within the hierarchy of prison life, the favors of prison guards and management can be doled out through the assignment of sought-after prison work assignments, including those managing other prisoners or which come with increased perks such as access to extra food, facilities, or equipment. For a prisoner who sees the library or prison garden as their only home within an otherwise hellish life, deprivation from these duties may be a significant source of psychological and emotional distress. Further, the competition between inmates for these scarce perks and benefits may cause inter-inmate strife which further results in inmates policing themselves, violently or otherwise, and removing pressure for the prison administration to maintain order.[58] Further, divisions between inmates diverts pressure and inmate energy away from guards and prison administration, reducing the collective ability of inmates to coordinate resistance against prison management. Prison work can be thought of as adding a competitive force between inmates which, when controlled by prison guards and management, can atomize prisoners and pit their interests against one another. In this degraded social state, prisoners may find it difficult to forge collective bonds, and prison management can more easily maintain control over their populations in despair.

Prison labor for activity

Within a prison system packed with prisoners “serving significantly longer sentences, and with virtually no prospects of early release,” prison labor is transformed from an opportunity for prison managers to reduce prison expenditures, to a requirement to ensure that prisoner energies are diverted away from activities that would otherwise threaten control of inmates.[59] A 1955 United Nations report on prison labor found that forced labor was not uncommon amongst prison populations. Most prisoners’ work was a form of punishment, rather than in expectation of economic benefits.[60] Even as prison work expanded to include industrial forms of profitable labor, a primary consideration amongst penal administrators was ensuring the second-class nature of the prison worker to the free laborer.[61]

By directing prisoner energies towards prison work, prisons maintain a monopoly over prisoners’ time and labor power. The labor power that could otherwise be used to strengthen inter-inmate bonds, curry favor, or perform emotional labor to maintain healthy relationships, instead becomes appropriated by the prison for its own productive or reproductive use. The inmate’s time becomes colonized and appropriated by the prison, and then used to further enrich the prison system, which is then further empowered to control the weary (and busy) prisoner.

Prison labor for management

From the perspective of managing the costs of prison, particularly where prisons face ballooning prisoner populations, prison labor for the maintenance and continued operation of prisons is a necessity of their function.[62] Simply put, if prisons were not able to use prisoners for labor, prisons could not afford to exist. While prison industries remain the most controversial uses of prison labor, the vast majority of prisoners work performing the daily activities of the prison such as cooking, cleaning, or maintenance which are necessary for the prison to continue to exist. Without the availability of prison labor, these services would need to be purchased on the open market, at a rate that would make prisons incompatible with a budget conscious system of management.

In response to criticism that Federal Prison Industries (FPI) maintains unfair economic advantages through the mandatory sourcing requirement (requiring federal agencies to generally procure from FPI when possible), FPI has undertaken some significant reforms to its policies. The FPI Board of Directors as of March 2003 requires that FPI approve requests for procurement waivers whenever lower costs can be achieved elsewhere, effectively eliminating mandatory sourcing.[63] Even though prison labor remains necessary for the prison system to function, capitalist forces outside prison walls can have significant effects on the prison labor economy. Because FPI production was seen as a potential threat to certain industries, FPI responded by opening itself up to market competition in the federal procurement system. In this way, we can see that FPI policies are subject to the concerns of market forces, at least inasmuch as they are represented by influential capitalists vying for the federal procurement market. In a similar way, there may exist opportunities for a concerted effort to open prison upkeep duties to free labor on fair footing.

Though one might expect states to more readily accede to the demands of capitalists than to the demands of labor, the effort to remove the mandatory sourcing rule provides noted similarities. Mandatory sourcing attempted to lower overall government cost by utilizing available resources (from FPI production) within the federal government. In the same way, prison upkeep labor aims to take available prisoners and use them as a labor pool to meet prison maintenance needs. Both removing mandatory sourcing and opening prison upkeep to free labor can lead available government resources (production labor and machinery or prisoner labor time) to go unused. While simply opening prison upkeep labor to competition from free labor at market rates would be unlikely to create a level playing field (due to the highly internalized costs of a prison labor force and its subsequently low wage), demands by labor to fully account for the costs of prison labor may result in a fairer competition between outside free labor and prison labor for prison upkeep assignments. Further, free labor may take the same stance as the capitalists in removing mandatory sourcing by claiming that remunerated free labor allows for economic stimulus from prisons to accrue outside of prison walls. For prisoners, demands for full cost accounting may, however, lead them to be charged for those internalized costs (the costs of their own imprisonment).

Whether this would, overall, create a better or worse situation for prison laborers is beyond the scope of this study but may present an important area for future research. It is possible that a full cost accounting which required prisons to hire free labor if that labor were below the “full cost” of an available prison laborer may be a possible avenue for reform. One would be remiss to overlook that while this may fundamentally alter the prison labor economics in such a way as to drastically reduce the prison’s reliance on prison labor, and even to increase the costs of imprisonment so as to lead to subsequent reductions in prison populations, the fundamental relationship between prisons and their prisoners would not necessarily be altered and the capitalist prison regime would remain intact.

Prison labor’s acceptance by the general public

Early theorists in economics and law argued that private governments arose where business maintained a strong corrupting influence over governmental policy.[64] This fear that regulatory agencies may be captured by the businesses they seek to regulate appears prescient in the late capitalism of today with a more pervasive congruence of business and government interests, working together to further capitalist production. In this mutually beneficial role, government and business act in concert to weaken the working masses and further cement control over them. In times of economic distress, where the economic sacrifices required by the capitalist-state of its poorest people threatens to become too great for them to bear, prison labor, while beneficial in the short-term to those capitalists who might profit from the cheap supply of labor during a time of economic upheaval, represents an existential threat to the persistence of capitalism as a mode of production. Thus, to maintain the capitalist status quo, the state necessarily transforms the philosophy of prison labor from one of productive potential (work as a right utilized to meet management objectives of prison efficiency) to one of a danger to be controlled (work as a privilege to be doled out in order of class, with prisoners last or nearly last).

Further, in times when free labor jobs are plentiful, and unemployment remains out of sight for most workers, prison labor presents little threat and is accepted or even encouraged as a duty of the prisoner in contributing to economic growth. In times of economic contraction, when demand for labor in the free economy is low, and unemployment becomes a social constant, if not an inevitability, workers band together, sometimes violently, to oppose prison labor projects.[65]

As imprisonment remains a means of controlling for surplus population in the labor market (a capitalist correction against rising wages, potential inflation, or increased labor power), and a combination of labor unrest (work stoppages in the general free labor economy) and unemployment or reported misery increase, the tensions of capital become more apparent, and this tension is reflected in the legislative decisions to further increase the criminalization of poverty.[66]

While the ebb and flow of prison labor as a labor pool and of prison production as a competing resource depressing commodity prices in the open market represents a visible economic driver to large-scale changes in public perception of prison labor (as a resource to be extracted or as a threat to be constrained as needed), examining changes in administrative decisions regarding which industries attract prison labor production represents a more focused possibility for examining the economic effects on prison labor management decisions. If prison labor managers are informed regarding the industries which they enter and the economic potential of prison labor within the larger economy, and they are empowered and rewarded for making these decisions efficiently, then we would expect to see this decision-making reflected in changes within prison industries’ business choices, as well.

Prison labor compensation and reproductive work

Feminist scholars have studied the ways in which domestic work and other “invisible” work’s removal from the definitional notions of work and labor devalues the reproductive work of facility maintenance, domestic work, and emotional care. Reproductive work is largely unpaid, or low-paid work and is afforded a secondary social value compared to “real work” which occurs in the area of capitalist production. There are noted parallels between this degradation of “women’s work” and the devaluation of prison workers who work in the reproductive work of maintaining prison institutions through forced cleaning, cooking, and building maintenance.

These workers, both domestic laborers and prison maintenance workers, perform duties which are repetitive, time-consuming, and physically draining, for little or no pay. Further, the relation of this pay differential in gendered work forms an important component of the economic power differential between men and women. Likewise, the pay differential between prison factory work and prison maintenance work leads to substantial differences in the perks and benefits of each type of work. For inmates with substantial debts from court assessments or victim’s restitution, prison maintenance work may not be a viable option as these deductions are often assessed prior to the prisoner receiving control of their wages, leaving little for personal use or to send to family living on the outside. To those workers attempting to support a family through their prison work, the burden of supporting the state’s extraction of their surplus value may perform a quite similar function to the extraction of value from women performing domestic labor for their families in an unpaid status, or for other families in a low-paid status. This extra burden helps deepen the impoverishment of prisoners by ensuring that their time in prison will see them at a substantially lower pay scale than their free counterparts.[67]

Prison maintenance workers generally earn far lower wages than prisoners in industry assignments, such as factory production, call-center work, or working for private companies.[68] Competition between prisoners for the scarce wages that are available can further degrade their ability to effect resistance against prison labor regimes. Further, prisons utilize the differential between these pay assignments to maintain order amongst prisoners through administrative policies that allow only inmates meeting certain goals (such as zero write-ups) the option to work in prison industry assignments. Thus, the differential between prison maintenance and prison industry work becomes another locus of control by which the prison can maintain its dominance of the prison population.

Maintenance and upkeep work is said to be reproductive in that it reproduces the conditions that allow productive labor to occur. This work is the way in which people must reproduce themselves through personal upkeep such as maintaining personal nutrition, exercise, hygiene, and shelter, and in the ways in which people reproduce their own fitness for labor, such as transporting themselves to and from work. Thus, by devaluing reproductive labor, capitalist regimes shift these costs into hidden sources and foist them onto workers. The worker or family that is then unable to internally maintain both their own productive labor (servicing capital) and reproductive labor (servicing themselves so that they can service capital effectively), must contract out that reproductive labor and in doing so recreates the capitalist relation in their appropriation of devalued care work from a domestic worker for their own person or household.[69]

Prison maintenance workers’ labor is considered reproductive in that it is necessary to reproduce the conditions that allow for prisons to exist in the first place. Without the cooking, cleaning, and prison maintenance that these workers do, the prison could not meet its most basic goal of housing inmates. Failing to meet that goal, and to maintain a place for prison industry workers to return at the end of the workday to recuperate, the prison factory would be unable to exist. In this way, the reproductive work of the prison maintenance worker is a precondition of the prison industry itself and prisons must maintain this internal labor system before pursuing profitable ventures.

Analyzing the production of prison industries and their role in the capitalist economy

How do prison labor managers decide which items to produce?

With regard to the pricing models used by FPI, even when FPI sold only goods to federal government agencies, its pricing rationale was to not exceed the upper bound of market prices while maintaining its corporate financial well-being.[70] Thus, the push towards economizing prison industry labor can be seen more as an attempt to increase the gross product of the nation and utilize the labor pool of prisoners than to bring in maximum revenue for the state. Despite these pricing decisions, FPI officials reported that they took a more customer-oriented approach to disputes with sourcing agencies and approved waivers when requested and that arbitration was rarely used in practice.[71] Pricing decisions have since moved to the control of senior managers of each product division at FPI who also document how product pricing is set appropriately for the market.[72]

Asatar Bair’s economic analysis of prison labor from a Marxian perspective presents the economic value appropriated by prison wardens and doled out both to industry in the form of contracts for prison work, and to employees such as guards (through perks and benefits provided by prison labor such as laundry, entertainment, or other privileges as an extraction of wealth from slave labor).[73] While prison industries tend to ignore or downplay this economic relation to avoid public concern, some industry players have emphasized their relationship to prison labor as a marketing gimmick.[74] From the perspective of inmates working in prison, when choice is an option, working in prison industry generally provides substantially higher wages than working in prison in-house duties such as cleaning, cooking, or plumbing and electrical work.[75] Further, for the warden, prison commodity production and prison maintenance both provide substantial surplus value to the prison system and become a point of pride regarding the prison’s use of scientific management principles. This use of productivity monitoring in compulsory labor reflects the role played by American slave labor as a crucible of scientific management practices.[76] Because of the low pay relative to value production involved in the prison labor relation, prisons can reap large internal profits from prison commodity production.[77] While these profits are largely retained within the prison system, they remain a useful locus of power for prison wardens, the arbiters of these internal profits.

When prisons retain prison labor outside the prison factory and instead employ it in prison upkeep duties such as cleaning, cooking, plumbing, and electrical work, they substantially lower the costs of prison overhead and ensure that prisons remain a viable industry as a whole. The work of prisoners both builds prisons and keeps them standing, and the threat of prisoners refusing or stopping work remains a substantial threat to the continuing power of prisons.

How are prison labor contracts awarded?