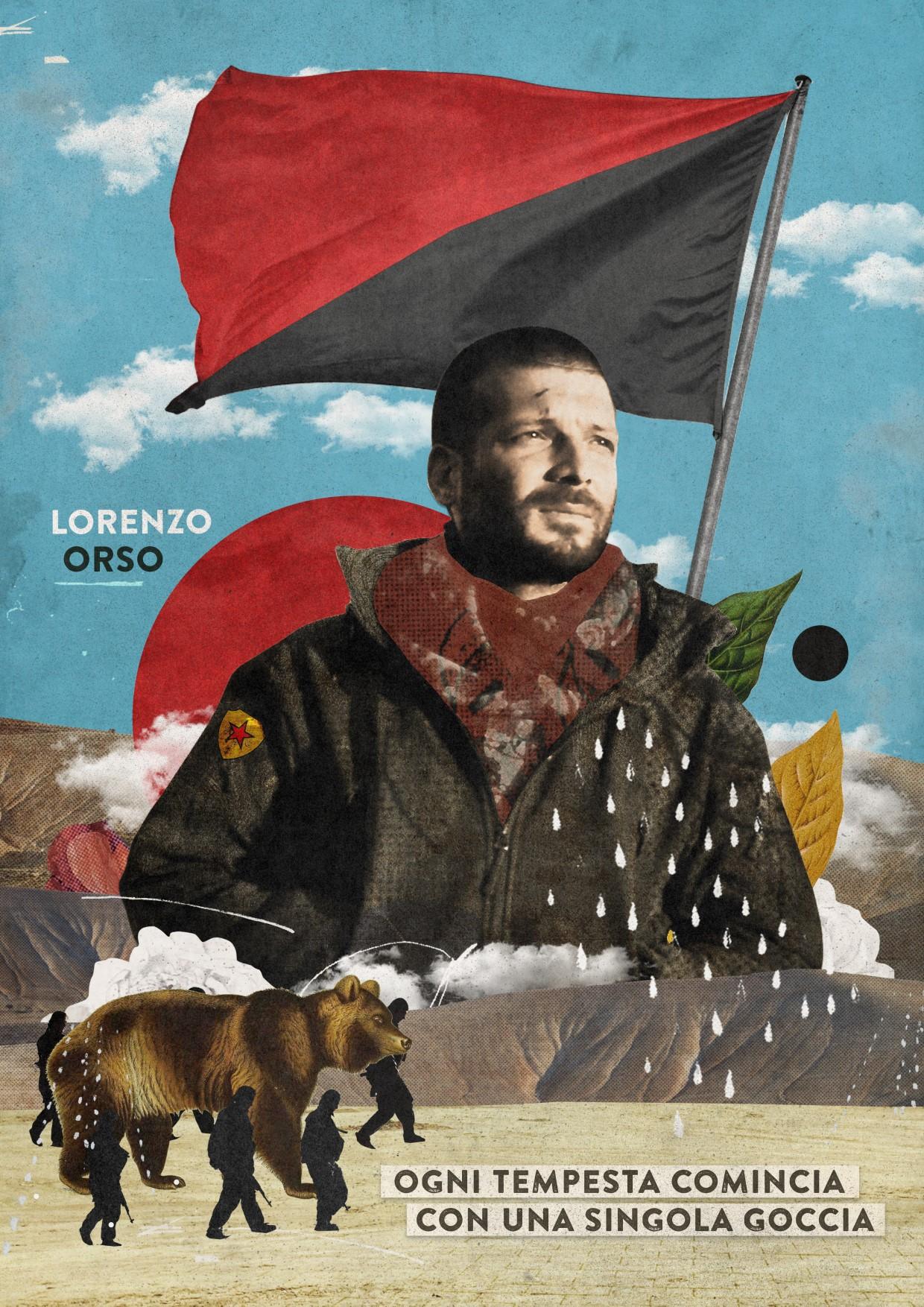

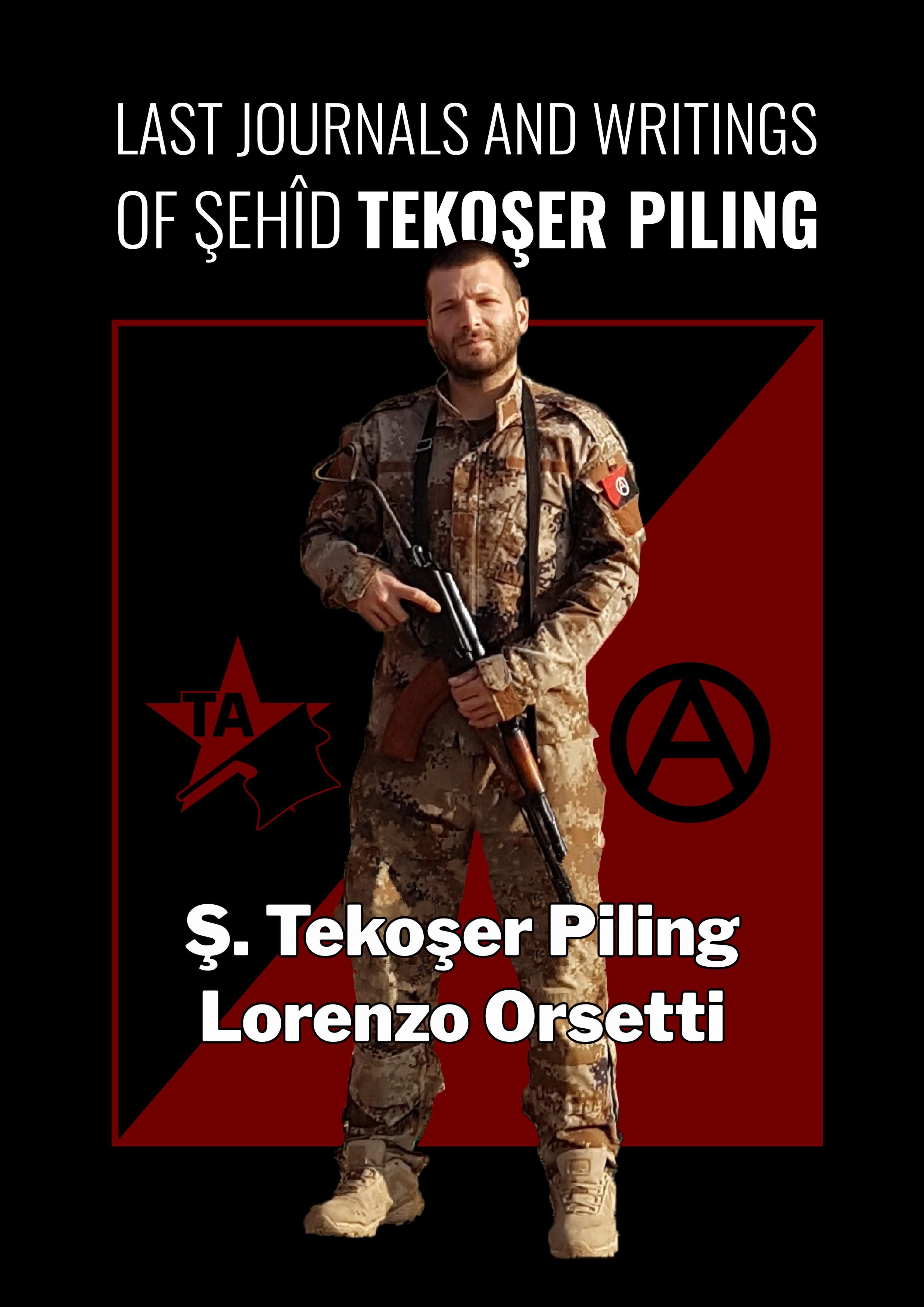

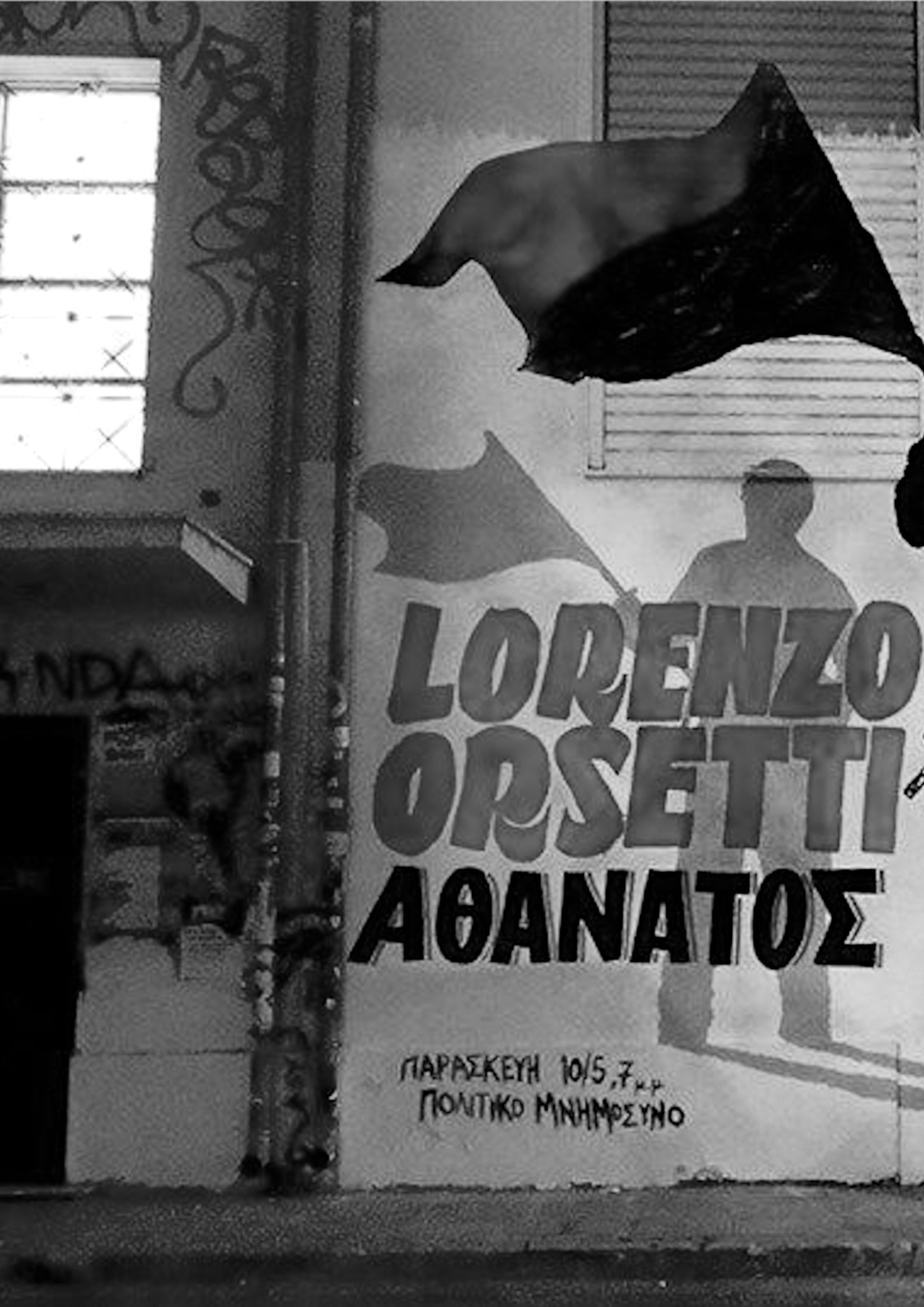

Ş. Tekoşer Piling

Lorenzo Orsetti

Last Journals and Writings of Şehîd Tekoşer Piling

Preface

in Baghouz Fawqani, in Deir Ezzor region.

He was a great friend to all of us and an incredibly brave soldier.

From Afrin to Deir Ezzor, he was always the last to leave.

We all carry the legacy of struggle from past times.

Realizing our connection to our history and to fallen comrades

gives us strength in present day.

Şehîd Tekoşer will always remind us of the fallen comrades,

the beauty of struggle and the price of the defense of freedom.

With our grief, we celebrate Lorenzo’s life and our common fight.

Our comrades who have fallen guide us always in the struggle.

It is our memory of them that illuminates our path.

In the darkest hour, when all looks grim,

we think of you, fallen comrades,

and it keeps our spirits high,

giving us strength to carry on.

- Tekoşîna Anarşîst

Afrin notes

Badina, February 2018

We’re back on the road.

The cold of winter is waning and the hills are adorned with flowers. Yellow and purple stripes meander through the rows of olive trees, giving the province of Afrin a fairytale appearance. The sky is clear and I am serene: whatever awaits me I am ready.

The village where we are is about ten kilometers from the front, the population is still in their homes, and in our home we will be more or less a dozen. Now, despite the large number of civilians, and despite the fact that we were there just passing through, the Turks will not have the slightest problem making mortars rain all night. The next day we helped out the survivors to collect their belongings and leave. Some will go far from Afrin, others to a more distant village. Many are elderly; they find themselves having to leave their homes where they have spent their entire lives, their livestock, their small piece of land. Some people cry. We stand there, waiting for instructions.

The drones are always watching us, we change houses very often and we move when there is a change between them. In front of us, at the foot of two large hills, lies the town of Badina. The front advanced five kilometers into the night, and the FSA conquered a group of houses just above the city. There is fire fighting here; machine guns and mortars don’t stop for any single moment. When it gets dark the hill shines, and in that blaze of lights and explosions it is hard even to fall asleep. They go on hour after hour, day after day. I tell my commander that I want to go there, “me too!” he replies laughing. He will come back after a few hours with his face disappointed, says that the area is under another command and that there is nothing to do. He will have to stay in the village, to organize the rest of the friends, while me and another comrades will go on reconnaissance.

We climb one of the two mountains above Badina, we are in enemy territory and caution is needed. A thick fog completely envelops us, I can’t say if it’s good or bad, we don’t see anything at all. Luckily for us there don’t seem to be any traces of soldiers in the area, so we decide to take a risk and reach the most advanced peak. We find a point that is perfect to stay for a little time: the city is two hundred meters below us, there are large boulders to cover us, and a cave carved into the rock offers us a natural shelter from the gaze of drones.

In Badina, meanwhile, we continue to fight. Not an hour goes by without some firefight, and the intensity increases from time to time. In the morning a couple of fighter jets unload about ten airstrikes on the city, in the day the heavy artillery destroys some house, at night the helicopter hits the town with shots, and so on…

My partner and me are incredulous: how do they survive so much firepower? Every time we look at each other like, “Come on, there’s no way, we go, they’re dead by force”, and now, after a few minutes, the fire response of the comrades always comes back to be heard. What an incredible resistance! They go on like this for two weeks, without faltering.

We climb and come down from the mountain almost every day, sometimes for supplies, sometimes because those who come alongside us do not know the way. A team is usually made up of five to six people, but at that time there were only three of us. I was resting in the small cave when cries interrupted my sleep “Allah akbar, Allah akbar!”. After twenty days of bombing, the Jihadists of the FSA are entering the city. They are firing into the air, some bullets are passing by. They are mostly in the center of the city, but it would be enough for them to advance a hundred meters towards the houses below to cut the road completely. For me and my international partner we should stay, wait for them to come out, and shoot, but the team leader who is with us thinks differently, he is very young, and does not feel like taking risks. I try to discuss it but it’s all useless, so, reluctantly, we decide to leave while the road is still open. Probably if we had fired we would have died, but the remorse for not having done so will torment us for several days. It certainly won’t torment the young team leader: he will die that same evening, killed by a drone bomb. Death has a strange sense of irony. Together with him another of our comrades will die, of them not even the pieces will be found, their bodies will disappear in a thousand shatters. With drones you never know: you are under some bare olive tree, with your breath in your throat, trying not to make the slightest movement, you just ask yourself “have it seen me or not?” You stay there, motionless, and with every missile they pull at you, think “okay, this is for me”. What else can you do?

Let’s go back to the village. One of the jihadists in Badina found the cell phone of one of our dead comrades and called my commander to make fun of him. He replied that with the planes and drones of Turkey “everyone is brave” and that they would fight like men – if they were. He is right. It would take more people like him in this world, and those who have known him know that it is a great loss. However, to die fighting remains a great death and I am somehow happy for him.

We are tired, dirty, and the team that has to exchange us arrived late. In war there is always a lot of confusion, it’s normal, but our commander thinks it’s more appropriate to keep us in defense of the city, so, as soon as the other team arrives, we go back to Afrin. As we get there, the first mortar shots begin to fall on the roofs of the houses. The planes fly low because their roar terrifies the population. They do it well. The city is almost surrounded, 2 kilometers to cut it off completely. “If the YPG retreats, we retreat. Otherwise we stay here, if someone has to leave – do it now.” Some leave, I do not blame them. I tell him I’m staying, but with death in my heart, there’s little we can do now, and being killed at this point seems almost a certainty. It’s not the style of the YPG to retreat, I prepare for the worst.

When the next day comes the news that we are leaving I’m genuinely relieved. An agreement must be reached to keep the only road open and evacuate civilians to the Syrian border. I’m glad that the general command chose not to sacrifice more people, with the city emptied of civilians we know very well how it would have gone: we would not have fired a shot, they would have simply razed the city to the ground. There is no dishonor, only regret, disappointment, anger. To see such a beautiful region delivered into the hands of these beasts! And it is the indifference, inaction of the world in the face of all this that is the real scandal. That a NATO member nation like Turkey has armed and supported gangs of jihadists in total indifference should make us think.

At the next Bataclan, at the next Rambla, at the next stop, I will not shed a tear.

Deir Ezzor notes

Hajin, November 2018

The front line was located about fifteen kilometers from Hajin. Our noqte (point), like the others, was surrounded by barricades of earth (called “satir”) on each side, and in the middle there was a small building with just three rooms. The next noqte on our left was about 500 meters away, and was more or less as large as our own one. The one at our right, around 200 meters away, was smaller. There was a new line of trenches under construction too far from our position, therefore impossible for us to defend it. A unit of Assyrians occupied the base on the left, while on the right there was a small group of local Haseke forces part of our group. In our point there was a unit of snipers (but badly equipped, since most of them lacked a scope for their rifle), one unit of sabotage (also without any kind of mines or explosives), and one unit of heavy weapons ( 1–2 humvee, 1–2 Dshke mounted on the back of pickups). These teams were not stationary, part of their members came and went, and, in total, we were hardly ever more than fifteen. We discussed with the commander to let us at least have a person with a thermal scope, which, however, given the thick fog that enveloped us at night, couldn’t do much.

The first ten days passed with relative tranquility, but around seven o’clock in the morning on the 21st we saw the enemy’s armored cars moving towards the right side of our base. There were two, both with turrets, and one a large vehicle which was reinforced with heavy metal plates on each side. They took the next base very easily; inside there were only six people: two were killed, one was taken prisoner and the remaining three managed to escape from the back of the noqte and continued a weak, but stoic, resistance.

The vehicles continued to move along the north side; moving forward and backward, making brief stops, in an attempt to make us waste ammunition. They exploited our trenches the position of the other noqte. From time to time they unloaded their fighters sporadicly, always sheltered by the numerous satirs. We tried to hit the car at 200 m with bisfing, and in a couple of cases we go very close; one of our anti-tank rockets exploded right near the back of the armored bus, but without serious consequences.

During the battle we killed several. We saw them carrying the bodies and loading them into the truck. At some point they seem to withdraw; in a fit of joy and exaltation some of our forces overrode the satir. Big mistake. One of the two vehicles appeared from behind a dune; opened fire, and hit one of ours. Everyone ran back, looking for shelter in the barricade, but a comrade of heavy weapons tried to drag the wounded away. We urged him to come back, but to no avail. Shortly thereafter he was hit in the face.

Ammunition began to run low, and the clash showed no sign of ending. Many of us remained with only one charger. The commander looked for someone to get on the humvee to go and retrieve the bodies. Without even thinking about it, I volunteer, and jumped up next to the driver. The vehicle makes a wide circle, the bullets break on the already cracked glass. As soon as we reach the two bodies we get out and drag them to the trunk. They continued to shoot at us, but within thirty seconds we are headed back. We brought the bodies into the nokta of the Assyrians, which at that moment was less affected by the attack. There I have the opportunity to take a few ammunition and a couple of rockets to bring back to my comrades.

When we come back, they are surprised to see me: a rocket had hit one of our humvee shortly after we had left, and they thought me dead. After another hour of clashes Daesh forces withdrew, this time for real.

We had to insist, but in the end we were brought a couple of boxes of ammunition. Many people rushed to it, and within two minutes it was already gone. Firat complains (rightly) to the commander, so, within an hour, another load is brought. The base is crowded with people, fresh forces, which we needed. But after going to the tent to clean our weapons and returning all the reinforcements had left.

We are even less than before, about fifteen, and we discover that we will have to spend the night like this. We are all sure of an impending attack, the first is usually a test, and bad weather is perfect for a second offensive. They’ll come back, maybe at night maybe in the morning, but they’ll come back.

We spent the night in a state of alert, we were awake until dawn. We only had time to rest a couple of hours before we heard the first shots. The sound came from far away: they were attacking several other noqtes across the front. Like the day before the armored vehicles took shelter behind our trenches, but this time there were many more, at least six or seven. They kept themselves at a distance and did not unload their fighters. After a while their vehicles went back about a kilometer and a half where the long stripe of dunes ends. From that position they began to shoot several rockets. They are not bisfing or not missiles, but they fall anyway within our perimeter with an absurd precision for such a distance. The Dshke is the only weapon we had that was capable of answering, but not very effectively, and it was already running low on ammunition. They did not have the same problem: 4–5 motorbikes were relaying back and forth to supply them. This carried on for more than an hour. We tried to call an airstrike, but the comrade who should provide the coordinates had some problems, and when the plane finally arrives (very late) its missiles explode only a few hundred meters from us.

However, the armored vehicles were no longer grouped at the end of the satir, they were turning back and getting pretty close to us.

Contrary to the day before our bisfing were all fired too early, and they all missed the targets. As if that was not enough, a projectile hit the Dshke, blowing it into pieces. At this point many of our fighters began to fear the worst: we no longer had bisfing, the Dhske was gone, and there was no more ammunition. An armored car loaded with Daesh fighters was incredibly close (sheltered behind one of our satirs, about fifty meters from us), while two others were approaching our sides in a sort of pincer movement, attempting to encircle us. Several of our men left their positions and ran towards the humvee that was covering the back exit. They screaming that we have to go. Our team was still in positions, but we were really very few. The commander of the heavy weapons unit understood that in these conditions there was very little to do, he spoke on the radio, and then ordered a withdrawal. Just in time, we managed to jump into the back of the pickups that were already leaving. Daesh chased us, firing projectiles and bisfing that only missed us by a hair. We passed other cars, from other points, that were also withdrawing like us. Daesh attacked strongly across all the front line, and the few that remained fighting until the end were killed or taken prisoners.

Daesh would release a propaganda video two days later, in which the severed heads of several comrades are displayed in a row as trophies.

We went back to the oil refinery where we had spent the first night. We met the front commander and told him our version of the events. He proved to be sympathetic and understanding, after listening to us he dismisses us, advising us to get some rest.

That same evening a car, carrying two Daesh captured in nearby clashes, arrived. One is Tunisian, the other Uzbek; they called us because one of them speaks English, and had a bad wound on his back. They didn’t say much, they played fools, so, after arguing with them for half an hour and applying a bandage, we let the friends take them away. We spent the night there, with the Heseke group. The next morning we saw several vehicles returning to base after the clashes of last night. The front line has been blown up, we were told. We take arms and ammunition and we arrange ourselves along the immense perimeter. It is not long before the coalition troops arrive. They have everything: about twenty armored vehicles, helicopters, and war planes. After a few hours the commander called for us, to explain that everything is under control, that we are being sent back, and that another tabur will take the place of the Heseke forces. We wanted to stay, but we did not insist.

On the way back, I can’t help but think of all the comrades who lost their lives without the coalition lifting a finger, while the massive deployment of forces to defend the pipeline clearly suggested that there was certainly no shortage of forces in that area. Moreover, all the rumors that Daesh was done now seem to me more absurd than ever. Daesh is still strong, especially in Hajin; they have great logistics and experienced people; Not destroying them now that there would be a way is, in my opinion, a useless and great risk.

Sitting in the back of the pickup, these and a thousand other thoughts are thrashing through my head, before the biting wind of the night overwhelms them with its frost. The villages through which we pass, though in our own area, are full of our enemies; You can tell by their contemptuous looks as the caravan passes. Once those sounds, those colors have passed, only the enveloping darkness of the desert remains, nothing else, to escort us home.

Hajin, November 2018

We arrive at the pipeline when the daylight is already fading out. The local commander recognizes me at immediately. He is friendly as always, and once the handshakes and ritual greetings are over he gives us a brief summary of the situation. Things are much better than last time: we are very close to Hajin, just outside the outskirts of the city, the defenses are solid, and the various points were built much more properly. We are arranged in a sort of “Z”, with two lines that envelop the city and one that covers the side. We are recommended to not enter for any reason into the old base; in the short time that daesh has taken possession of it, there are weapons and ammunition left well exposed to attract us.

After a couple of hours two cars arrive to pick us up. We go up quickly, without even the time for the greetings, but once on the road the comrade to the driver’s side turns around and says to me: “I am Marwan, Marwan the Crazy”, “I am Tekoşer, and I’m crazy too” I say to him. We laugh. He has a nice face, but he also looks like a tough guy. He fought in Kobane, and he doesn’t seem at all tired of this life. I immediately understand his type; I’ve already seen many other fighters like him: tireless people, capable of withstanding days without sleep, insensitive to heat, cold, fear. We drive for a long time, much longer than last time. When we get there, they invite us to drink tea inside a Defender (big armored van with a turret). The çay is good, and the commander seems like a nice guy. He tells us that two nights ago daesh attacked that position, but without success, losing four men, two motorcycles, and several weapons. He also takes care to show us all the coordinates of the place on a tablet, once finished, tells us that for that night we are not on guard, and that we can go to rest in a tent that has been prepared specifically for us.

With the first lights of dawn we have breakfast and look around a bit better. You can immediately see that the camp is newly built, in fact the presence of waste, mice, and excrement, is significantly reduced. The war can be a very dirty place to be. I head to the highest point, in a large barrier of send bags that with other comrades we will call “the ship” because of its unique shape. Once reached, I am dismayed: Hajin is so close that it seems like a mirage! I’m just stoked to observe the town for a few moments, when a comrade from behind approaches, interrupting my amazement. His name is Aras, and he is the team leader of the group that presides over “the ship”. They are all Arabs, and no one knows Kurdish, but I still don’t know how, in a basic of mimicked gestures and non-existent words we manage to understand each other anyway. Obviously a glass of çay with plenty of sugar is a must in these situations.

The days fly by, and, apart from the endless night watch sessions, and the typical tedium of the front, it’s not so bad. One side of our front is advancing rapidly in the city. We ask to be able to do the same, but the general command tells us to wait. One evening from the next point see movement in the dunes, certainly the enemy reconnaissance, and the comrades decide to ambush them.

Al Susah, January 2019

“They’ve already left.”

“What the hell?!”

“Yes, yes, about an hour ago”

An anxiety grimace is immediately painted on the faces of my companions. “We’re screwed.”

“But nooo, you’ll see that there is a way”, I answer.

Heseke’s battalion has already left the base, and there are four cats left in the square. I recognize Marwan “the Crazy” walking with the commander. They walk in a way we have named the “walk picture”: it’s the very common practice of taking each other by the arm and, with the back slightly curved, always go up and down the same path. It was invented many years ago in prison; once again it is the mere necessity to keep the tradition. I see that they notice me, so I’m going to say goodbye to them.

“No problem! We have a Defender (armored truck) that is to repair and tomorrow it should reach the rest of the group. Until then you are my guests.”

Well, usually “tomorrow” is never actually tomorrow in Rojava, but I’m fine with it anyway; I’ve had some health problems lately, and a couple of days of rest, heat, and good food (in the Heseke base you can eat really well because many people requires to bring civil cooks from the city to cook) can’t hurt me. After almost three days we finally leave, and once we reach the usual pipeline, we change car. The ramshackle logistic van continues along the impassable road, jolting us at every hole. The stereo pumps out the sharp and incredibly repetitive sounds typical of Arabic music. We proceed in a straight line, without the slightest hint of a curve, until the road also disappears, and nothing remains; only the pale yellow of the desert sand, which clashes with a crystal clear sky. I recognize some of the bases from which they have already passed, and then, finally, the silhouette on the horizon of the city of Hajin. It’s a bit strange to cross it like that, without any problem. There was a lot of fighting for it, and many comrades lost their lives in this effort. The city is reduced to a heap of rubble; the holes in the road made before seem nothing compared to the craters of about fifteen meters left by the airstrikes. I had already been to Raqqa immediately after the liberation, I’m already used to seeing some kind of destruction, but here we are just at another level. It’s like being inside “Guernica”, Picasso’s painting. Or in a game of “Tetris” ended badly. Some civilians in the suburbs, heedless of the unexploded mines, are already beginning to return to what remains of their homes, but the bulk of the city is closed by the Asayish checkpoints. We arrive in an abandoned hotel, where there is a sort of general command. The battle for control of Al Susah has already begun. They tell us that they will wait the night before sending another wave. Some comrades of heavy weapons regiment insist that we stay with them, but heavy weapons require a certain distance to work, and preferring the front line we are forced to refuse.

When the night comes, we leave. We are crammed in twelve in a Humvee, and after several hours of waiting (a large bulldozer is cleaning the main road from the IEDs) we are launched into battle. There is no preparation time, you go down and fight immediately. With due caution we take control of the roof of a building. We are about in the center of the city. Between one thing and another it is already dawning. The unmistakable sounds of the war rise all around us; scattered like leopard spots in various districts of Al Susah. A hundred meters away from us I notice two silhouettes. The tallest one wears a long village coat, but they are facing in the same direction as us. It’s an easy shot, but I don’t want to hit any of our people who, maybe because of the cold, put on the first jacket they found. I ask the team leader, who contacts some of his teammates via radio, butwhen we are given the green light they are now very far away. We’re away, I see the bullets smashing into the wall behind them, before they both disappear around a corner. Daesh hasn’t been fighting in uniform for a long time, to try, when possible, to blend in with the civilians. In the meantime, it’s already morning, and we’re moving on a couple of houses. We are squatting behind an armored car, heading for a point a little further on occupied by comrades. It seems a fairly quiet moment, and I decide to take a picture with my mobile phone. One of the inhabitants of the point is standing near the entrance. It will be his last live photo: as I press the shutter button the shot of a sniper is exploded, almost simultaneously, as if it had been my phone that had shot. “Uoooo!”, an exclamation escapes me from my lips, while his body is afflicting the ground without life. The comrade lies down in the trunk of the Humvee, while we proceed on foot to the shelter behind it. This time I am not the one to collect the body of the unfortunate person, because I am intent on making covering fire towards the windows that I consider ideal hiding places. Daesh has formidable snipers and they are very difficult to detect. Once the body has been collected and moved a couple of houses back, we climb on to an elevated floor, in an attempt to understand where the shots are coming from We also have to be careful of the sides, to avoid any encirclement maneuvers, another specialit of Daesh. Suddenly the sound of a missile dropped by an airplane cuts through the air near our position. The building next to ours literally shatters. Huge blocks of reinforced concrete hover gracefully in the sky, making obvious mockery of any notion of gravity. I’m just in time to cover my head with my arms before the rocket hits us. A large stone hits me in the chest, snapping the spring of one of the magazines, which at that moment almost hits me in the face. The magazine at least softens the impact, together with the bulletproof plate that Kawa left me; I wouldn’t have died, but maybe without it I would have cracked some ribs. You can’t see anything anymore; the dust from the explosion reminds you of sand storms. I can only distinguish the silhouettes of my comrades with me.

“Are you all right?” I ask them. “It’s all right,” they say.

The clashes go on for a couple of days. We are located on a building from which you have a good view. We take never ending shifts, at least six hours a day, sometimes nine hours. Most of the enemies are buried under a building, mowed by airstrikes, but several of them have surrendered. The few survivors are retreating to their last remaining village. They burn the ammunition they can’t take with them; we hear it crackle in the night, like popcorn, inside big bonfires lit inside deep holes. Not a day goes by without someone stepping on some mine. For each house we clean we use large handmade bombs, called “fitil”, similar to “Maradona balls” or other Neapolitan barrels, able to clean the rooms of any devices. But sometimes they are not enough, or are finished, and remain ineffective in outdoor environments. In short, it’s not exactly a healthy walk. One afternoon we hear the sound of a small engine. The comrades from the roof next to each other scream and hustle pointing to a point in the sky. It’s a drone from Daesh. Of course, it won’t be up to the Turkish drones, or the coalition, but it’s still useful to reveal a lot of our positions. We start shooting in the air like obsessed people.

“We’ll never catch him,” I think inside me. But instead, when it passes a second time over our heads, a lucky bullet manages to hit it. We start laughing, jumping, and shooting to celebrate. No, we won’t be an army of professionals, but you know what? That’s the beauty: so much euphoria, so much heart, and so much courage, I’m not sure they can be found in the ranks of the regular armies. We spend the last two days pawing along the edges of Al Marashidah, the last country officially controlled by Daesh, but every time the attack seems to start a counter order arrives immediately after. Meanwhile, a new battalion has arrived to take over. I don’t mind: it’s cold, I’m tired, and I haven’t washed for about twenty days; as for Deir ez Zor, I think that I have given my contribution. There are few enemies left in that area, most have already escaped long ago to Idlib, or Afrin, or Turkey. Some have managed to blend in with civilians.

I think about the limits that I had, and how this long road undertaken to Rojava helped me to overcome them; but not how I would have done it at home, raising the bar from time to time, but taking the chase and breaking through all that was there. I’m calm as we return to the base. From the car window, the glow of the sunset ignites the tops of the palm trees, and the sun slowly goes out in the cold waters of the Euphrates River.

Baghoz, March 2019

We leave in a hurry, after all in the academy we have been taught that in a minute and a half we must be ready for anything. I trusted “livemap”, believing that Marashidah was the last city left, but I discover that it is in Baghuz that this story will end. We find ourselves in the usual headquarters, next to the abandoned hotel in the center of Hajin. We eat and drink with the commanders, while they show us the progress made on a tablet. We did not even finish before Marwan enters: “So we’re going” he says to the local commander. I take the opportunity immediately, “can I go with them?” I ask. They exchange a look, then Marwan makes “yes” with his head. “Uao! It was easy this time” I think to myself. Sometimes there is a kind of protective attitude towards the internationals, and often reaching the front lines is a real problem. The operation is fixed for the night of the next day. We go by car, visiting the various points arranged just outside Baghuz. We make more trips, loading and unloading tons of ammunition, distributing them equally to the various groups. On the day of the attack we find ourselves with several other teams, in a large courtyard sheltered between two houses. I look at our comrades: many of them are very young, just fresh from the academy, some Arab boys wearing some masks and strange tufts similar to the “emo” fashion of a few years ago; another one wears a gas mask, and a hatchet pops out from behind his back. There is a certain aesthetic that we all have in common, but each one wears pieces of different uniforms and kefiya of the most varied colors. We look like “the Brancaleone army”: we are beautiful! Being a unit of “hermits” there is not all the order and rigor typical of battalion paintings, but these guys are still going to fight against people ruthless, organized, and often trained in the West, yet none of them shows the slightest sign of fear. The morale is strong: you dance, you sing, and you drink hectoliters of çay. At dusk we all gather together, including Humvee and DShK, in front of a large groove dug by a bulldozer. Beyond that line it is all daesh area. The large armored bulldozer precedes us, our driver follows it, very careful to remain on the tracks since the whole area is mined. For each group of houses we stop and pull “fitil” bombs to clean them from the explosive traps. We’ll throw a hundred of them, maybe more, and almost all of them blow up something (the noise is louder when, besides the fitil, some device explodes). So we move forward for several hours, taking more than half of the city. It’s four o’clock in the morning when daesh go into counterattack. They have targeted the two most isolated houses, surrounding them almost completely. I am about two hundred meters from them, we hear the cries “Allah akbar!” and we see the trails of rockets being fired profusely. Some bullets fly in our direction. At a certain point we see the Humvees starting from those houses at full speed, and we too are ordered to retreat. Most people pile up on the Humvees as best they can, reminding me of the photos of some buses in India full of people, but a small group of us remain without passage, and we have to make it on foot.

We run in the most complete darkness, with all the heavy equipment, with the hissing of bullets passing on our heads, trying to stay on the tracks of the bulldozer because everything around is mined. In short, it’s not really the best. I look at the boy next to me who is pounding with his ammunition backpack, weighing several dozen kilos, and I am happy for him who has several years less than me. We all gather a few houses further afield. We have very few blankets, so we sleep stacked on top of each other because of the cold. In the meantime, daesh has withdrawn, and we have to go and recover the bodies of fallen comrades. The first one we load without any problems, the second one is in a more advanced position, and while we are hoisting it on the back they begin to shoot at us. A rocket is fired at us. The driver starts the engine; I am in the trunk and my leg is stuck between the two bodies. Slipping, I lose a shoe, and it is while I search in that tangle that I notice a cloud of steam coming out from the mouth of one of the two. “Hey, this guy’s still breathing!” I say to his comrade next to me. He’s alive, but he’s beyond here. I doubt he’ll make it. They leave us at the house and go straight to the field hospital. We win back several buildings. Our group stops in those two from which we had been driven out in the night. We are on the roof, when at a certain point bullets start to rain on us. I look through the holes in the wall we made to protect ourselves, but I can’t tell where we’re being shot from. I ask my partner next to me, but he says a word in Kurdish that I don’t know; I ask again, and he makes a gesture with his hands as if to say “inclined”. Then I understand: there is a large silo, and looking better I see there are holes holes equal to ours. Let’s focus the fire there. We also pull two bisfings (RPG) and fire them. The shots coming from the silos stop. In the house next door we found the entrance to a tunnel, which explains how the night before they had managed to arrive so suddenly. In a few days we take almost the whole city. Only a very small strip of houses remains, trapped between us and the Euphrates. To separate us from this neighborhood there is only a grassy expanse, without buildings, about a kilometer long. Our Kalashnikovs are useless in that distance, but we have several BKC (PK machine gun) and a Karnas

(Dragunov SVD). The airstrikes can not hit that area, because of the certain presence of several civilians (even the battalion on the other side of the front released some Yazidi prisoners from 2014). Daesh no longer has the strength to counterattack; they try a few tricks, at night, but always only a couple of people in motion, probably to mine the road. We repel them every time. Their snipers shoot us often, fortunately with poor results. One afternoon we are on the roof and Marwan is firing a few shots with Dragunov, when we see one of their vans. Suddenly I remember that in one of their armories we found an SKS: it’s an old Soviet rifle, it shoots the same ammunition as the Kalashnikov, but it reaches us up to 1000–1200 meters. I run to get it, and load it with a handful of ammunition that I have in my pocket, while I dive up the stairs. We both fire a dozen shots, aiming for the cockpit. I don’t know if we break down the vehicle, or we hurt the driver, or we just frighten him, but we get close to him because we see him get off and run away fast, leaving the truck there. Marwan laughs on the radio, and two comrades are standing next to me; I am always there with my eyes pointed, when suddenly the wall shatters. The boy next to me screams “They hit me! They hit me!”. I look at the hole in the wall. “BAM!” another hole, this time on my left. They must not have liked the trick of the van, because they are shooting at us with a Zagros. The Zagros is a large caliber rifle, it is self-produced by recycling the barrels of the DShK machine guns, and fires the same ammunition (bullets about ten centimeters long to be clear), and has the bad habit (or good depending on if you’re pulling the trigger instead of being the target) of passing the walls as if nothing was wrong. I grab the Dragunov and we run towards the stairs. The boy continues to scream and loses a lot of blood. The stairs are half collapsed, and to be able to go down you have to crawl in a triangular slot. Me and an Arab comrade remain last; he is a big man with a thick black beard, he wears a curved silver dagger in the middle of the magazines, he wears pieces of enemy uniform and if I didn’t know for sure that he is with us he could appear a bit disturbing; but he has the eyes of a good man and he has always been kind to me and the other comrades. He has just slipped his legs into the slit, when he searches his pocket and points to a point behind me. “BAM!” meanwhile the Zagros shoots again. I look at what he’s lost, and notice an external cell phone battery in the middle of the roof. As I turn around to look at it, my brain in a millisecond elaborates the most sensible answer possible: “But I will be shot!”. Good, a sign that it still works, but inexplicably transmits to my body something else, a sort of “…and whatever”. So I run with my head down to get his battery, cursing all the saints that come to mind at that moment. When I hand it over to him, he thanks me warmly. The good man dressed as daesh has found his smile again. We run to the ground floor, where the boy continues to scream. It’s not serious, he probably has a shrapnel in his arm, but his bones and arteries are intact. We treat him and have him taken away by a Humvee.

Meanwhile, the days pass in the point. We would like to move forward, with the few houses left we could finish the job in one or two days, but the orders always held us back. To pass the time we clean up all the buildings in the area. We find everything, especially drones and explosive belts. Comrade Şamî gets it into his head to blow them up, so he collects as much as possible and presses them all together. He makes them explode next to the big silo, hoping to knock it down, but the reinforced concrete stood, even without one of the pillars it rests on. Şamî is still happy, until he notices something on our way back that will change his mood irreparably. It’s the lifeless body of a child, or what’s left of it. The legs and one arm were blown, only the chest remained, a small burned hand, and the skull, open like the shell of an egg. The corpse had a pink jacket with purple stars; it looked like a broken doll. I had already seen the corpses of women and children in Afrin, who died under Turkish bombardments, and the comrades I knew that have now fallen I can no longer even count them; of course, I do not remain insensitive to death, but it no longer has the same effect on me as it did in the past. Şamî, on the other hand, is angry, almost crying, he doesn’t say a word for the whole trip back. “If it wasn’t just a little girl”, he repeats from time to time with his voice full of pain. In fact she was not to blame, her only misfortune was being born into the wrong family. The two cars which were burned were both full of explosives, a sign that her father, or whoever was traveling with her, was certainly of the Islamic state. After all, daesh’s struggle has always been a family affair: women join the intelligence,they blow themselves up, and they too get stained with the worst crimes; their children, though very young, drive car bombs and lay mines where they can; the youngest children are very often taken on suicide missions. No one is excluded, and the border between victim and executioner is weak and not always clear.

Meanwhile, other teams have come to take over. In the village just outside Hajin, children chase our cars. I throw from the window all the snacks and bottles of water we have; in exchange we receive big smiles and screams of joy. But the biggest surprise is yet to come: it has rained a lot these days, and when we reached the desert I found it hard to recognize. A very thin layer of grass covers the whole of it, drawing a green expanse that is lost on the horizon. My eyes are filled with that brightly coloured ocean. I look at it absorbed, incredulous, as if I were in the presence of a miracle.

Last letter

Ciao, if you read this message, it is a sign that I am not in this world anymore. Bah, don’t be so sad,

I’m doing well; I have no regrets, I died doing what I thought was the right thing, defending the weak, and being loyal to my ideals of justice, equality, and freedom.

So, in spite of my premature departure, my life has been a success, and I am almost sure that I went with a smile on my lips. I could not have asked for better.

I wish you the very best, and I hope that you too one day (if you have not already done so) decide to give your live for others. Because it is only like this that the world can be changed.

Only by overcoming the individualism and selfishness in each one of us, can the difference be made.

These are difficult times, I know, but don’t fall into resignation, don’t abandon hope; never! Not for one moment.

Even if everything seems lost, and the bad things that afflict humans and the earth seem unbearable, keep on finding strength and inspire it in your comrades.

It is exactly in those darkest moments that your light helps.

And always remember: “Every thunderstorm begins with a single drop.” Make sure to be this drop.

I love you all, and I hope that you treasure these words.

Serkeftin!

Orso,

Tekoser,

Lorenzo

To Save

combined in the gray autumn frost.

Although they were distinct elements,

now they were twisting

dancing in one great opera.

And that work had a name,

was living meat once upon a time.

Of those laughter, of those riots,

only a handful of ashes remained,

to blend in with the tears, the memories.

He was overwhelmed by nothingness,

carrying around the scattered pieces of that party,

irreplaceable fragments,

an essential part of us.

Only this cold, so dense, so persistent,

remained to wear down our souls.

A cemetery,

a black tree dying,

of the moist earth,

and dust; only dust.

Nothing you could really tighten,

nothing that could heat up what little was left.

The sky itself shows silver tears,

and this strong wind seemed to take away all hope:

it was no longer time for life,

there was only autumn,

under this shapeless sky.

The day of the trial

It was an unmistakable evil.

Pure. Distinguished.

He dragged him down from his bed at dawn, tearing away without delay his first suffered lamentations. In recent times he had faced a different pain, much more subtle, tied to his mind; corrupt nightmares were graying his thoughts. But this abuse had a thousand faces and as many nuances: it was the physical pain that visited him this time.

He had a regular rhythm, he followed his beats, he had crept under his skin. Punctual, clean, he gave off discharges similar to punches that crossed him completely, piercing him in several places. He trembled, like a leaf in autumn, and as such, he died.

It was a carrion, dispersed in the desert, and that, unfortunately for him was the lunchtime of the condor. As he was dismembered, slammed, turned around, in that slaughterhouse, his body twisted without finding any way out.

He counted the hours that separated him from the end, an end that he yearned for, an end that could bring him relief. He knew that this torture would soon lead him to the path of the madmen.

He was not able to cry, or pray, he could only cling to that pain. His brain was there, chasing that evil; he had merged with it to generate that hell.

The dentist said he could do nothing about it, his gum was too swollen; he had to wait many days before that wisdom tooth would end up tormenting him. He was safe, or perhaps so he deluded himself.

O.O.

p.s. Stuff yourself with painkillers and as soon as you can take it off.

The great “bho”

He was wandering around the neighborhood like an old ghost can be wandering around a cursed house. He didn’t look good, he didn’t look it at all.

Although some good ideas had come to wake him up that morning, his face ranged from “sad dull” to “repulsive corpse”.

He looked more like a junkie than a writer; he was both, of course, but the first aspect prevailed that day.

He continued to carry that half-popped tobacco to his lips, it was like the fourth time he did it, either he would turn it on as soon as possible or he would continue to do so indefinitely. He turned it on. It was perhaps a mistake because the nausea hit him hard in the mouth of the stomach; a champion’s hook, Cassius Clay wouldn’t have done better. When he reached the atrium, the dog that was carrying with him, began to jump with joy.

-You always want to live like a dog.

It was his weak response.

As he spoke those words he was about to put it back on the stairs.

He got close to it, but he stayed.

The party was over, he knew it well.

Because when it’s daytime, there is no longer any whore who for some money can snatch away a little bit of loneliness, there is nothing more that slips on glittering foils, or that fizzles in some pipe. The glass remains empty, simply, and you remain empty with it. Nothing that can deafen you, nothing that looks like an incurable wound.

The lights go out and this fucking freak closes his doors, you stay there, disintegrated, slammed, and you already hope for another round of merry-go-rounds.

At least as long as it lasts, as long as you hold on, you delude yourself that everything has to go like this.

The mind screams

In that moment, in that life, and that’s when the restlessness got the better of him. It stood above me, crushing me triumphantly.

Under such a monstrosity the hope ended, twisted with his soul, like a fish thrown ashore. That thing, that monster, was digging into my chest; a road was opening up with its claws. I didn’t know it immediately, but that road was destined to become a chasm, like a big mouth that opens wide, that swallows, greases, every rare emotion.

This horrible creature fed on me, on my essence, wandering cannibal inside me, defecating only hatred. To get away from that being seemed impossible to me, I was now corrupted by that evil, it had crept into me, he had me: I was affected even in the bones. It acted by consuming me, by tearing my tissues, that I was irrevocably separating myself from.

The frost of the transition, in its implacable calm, wanted to grab me; Every move he made was aimed at oppressing me, at chaining me to his terror. The pain, the torment, and the pain that I myself felt towards me, they replaced my organs, my heart, my lungs. No angel would have moved a finger to save me from domination. I was alone, alone against the abuses.

Who could have wanted all this? I asked myself. So I looked for my jailer, that crazy sadist who once signed my sentence. When I saw him, when the creator of such despair turned to me,*I was horrified; I felt disgust.

His face changed rapidly, and now it’s taking on a thousand different contours. I saw there again the women I once loved, past lost friends, but on all of them, I saw myself.

His face ended up staring at that image and that image stared into my nightmare. It is in days like these that the mind falters, hovering between getting lost and finding each other, but who has the choice? And above all, is there a choice?

The mind screams,

I will ask my executioner, I will ask my executioner to annihilate it.

We are a spit

in an ocean of adventures.