Michael Duckett

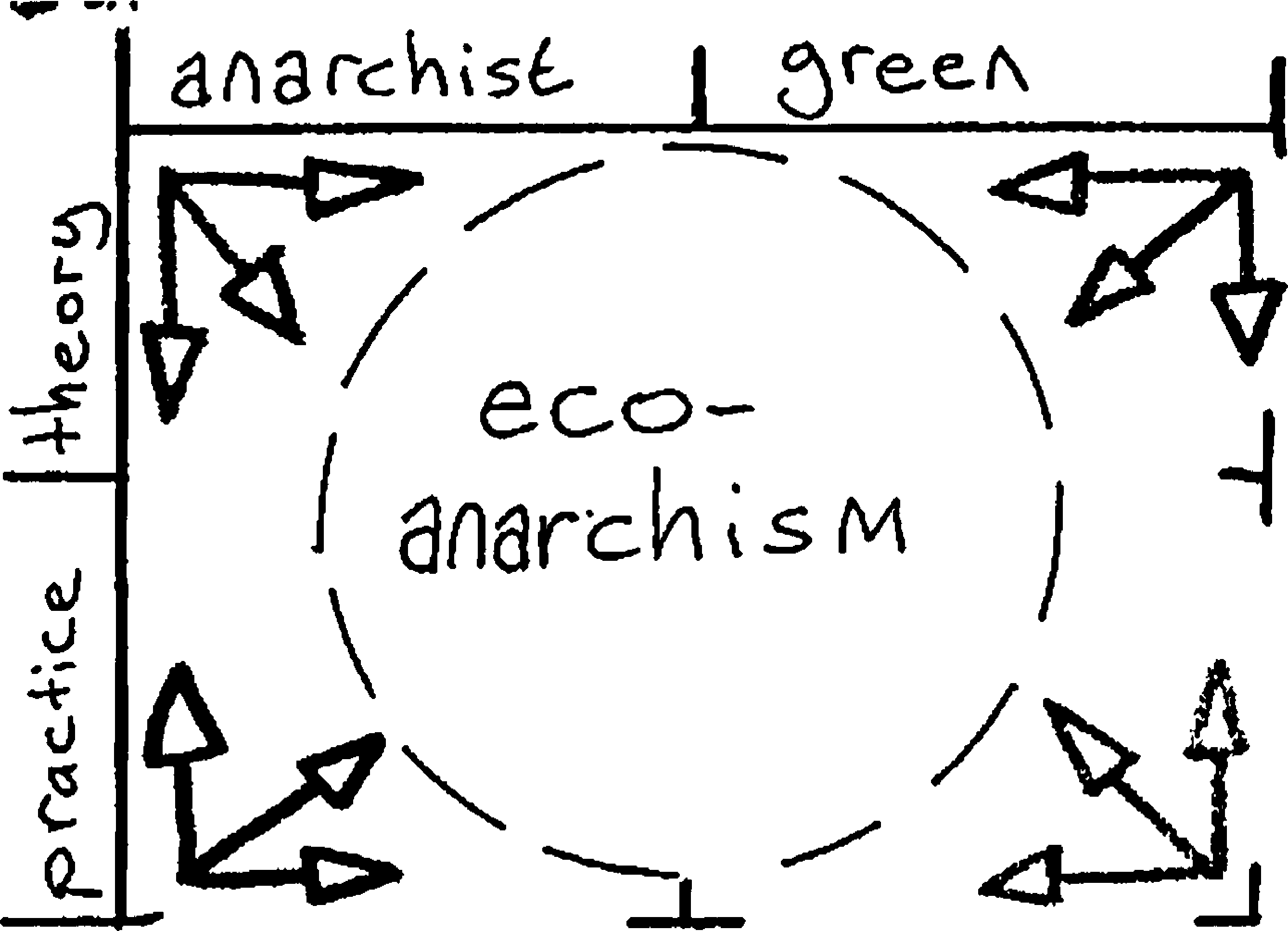

Ecological Direct Action and the Nature of Anarchism

Explorations from 1992 to 2005

1.2 The Project: Anarchism in Environmental Direct Action

2.2.1 Against Authority — Against Definition

2.3.3 Orthodoxy and ‘Second Wave’ Anarchism

2.4 Anarchist Theory: Conclusion

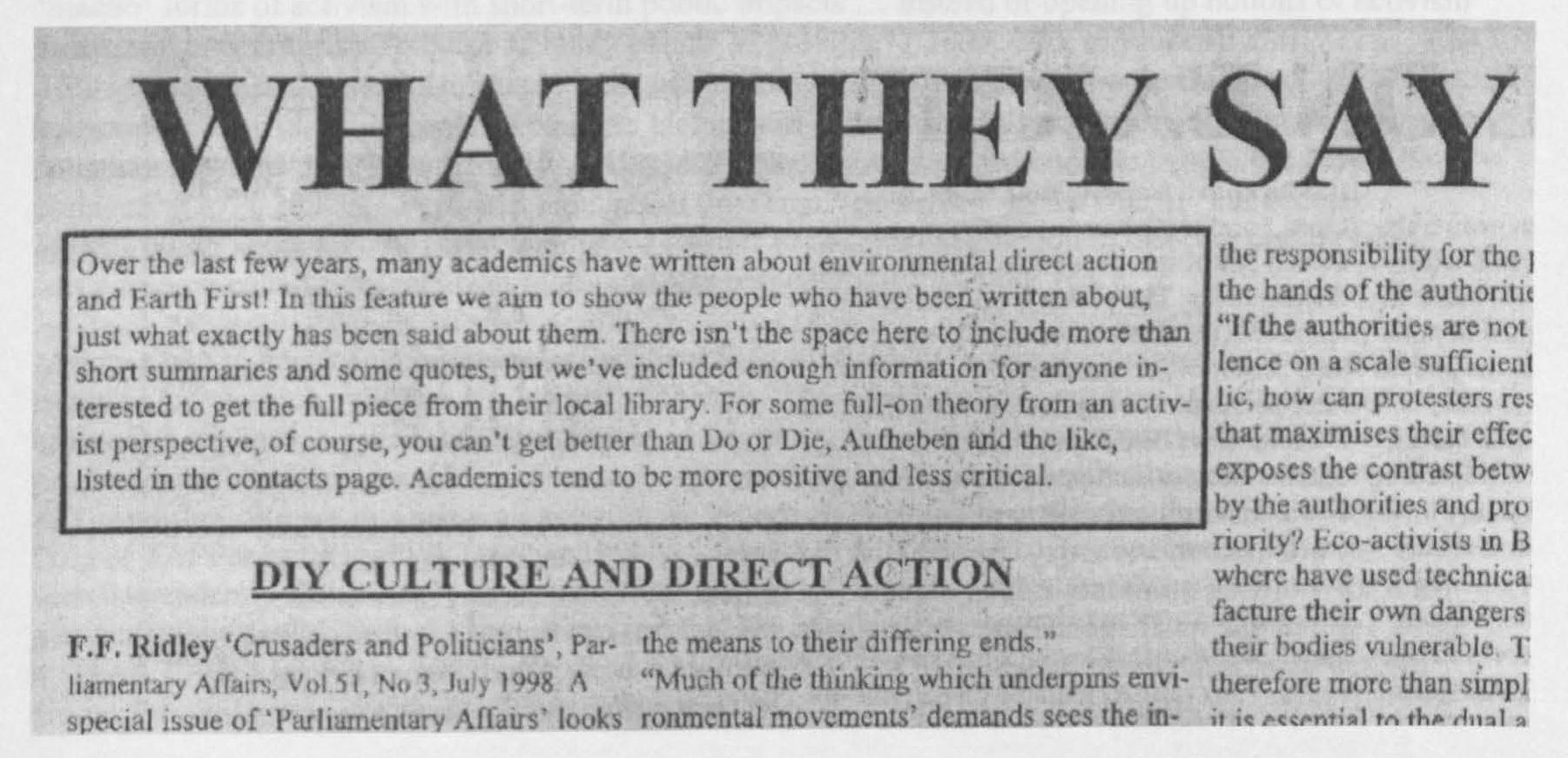

3.2 Anarchist Perspectives on Research and Theory

3.2.2 Critiques of Dominant Epistemology and Theory

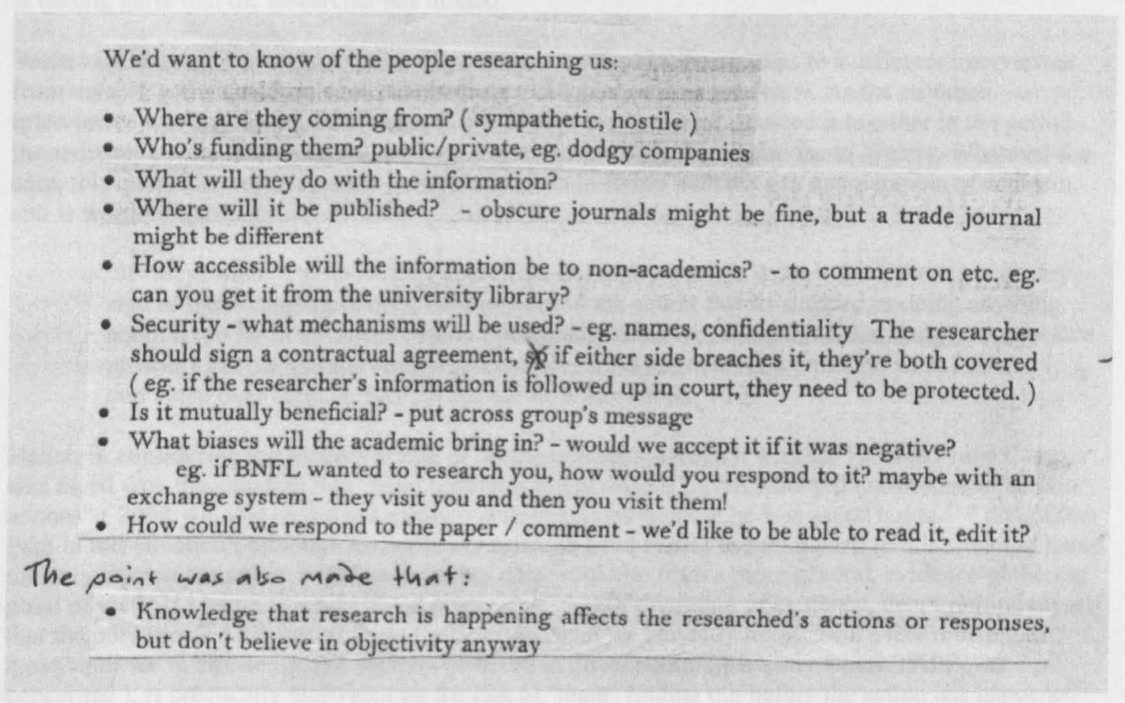

3.2.3 Political Approaches to Research

3.2.4 A Personal Approach to Research

3.3.1 Anarchism and the Academy

3.3.2 My Relationship to the Academy

3.3.3 My Relationship to Activism

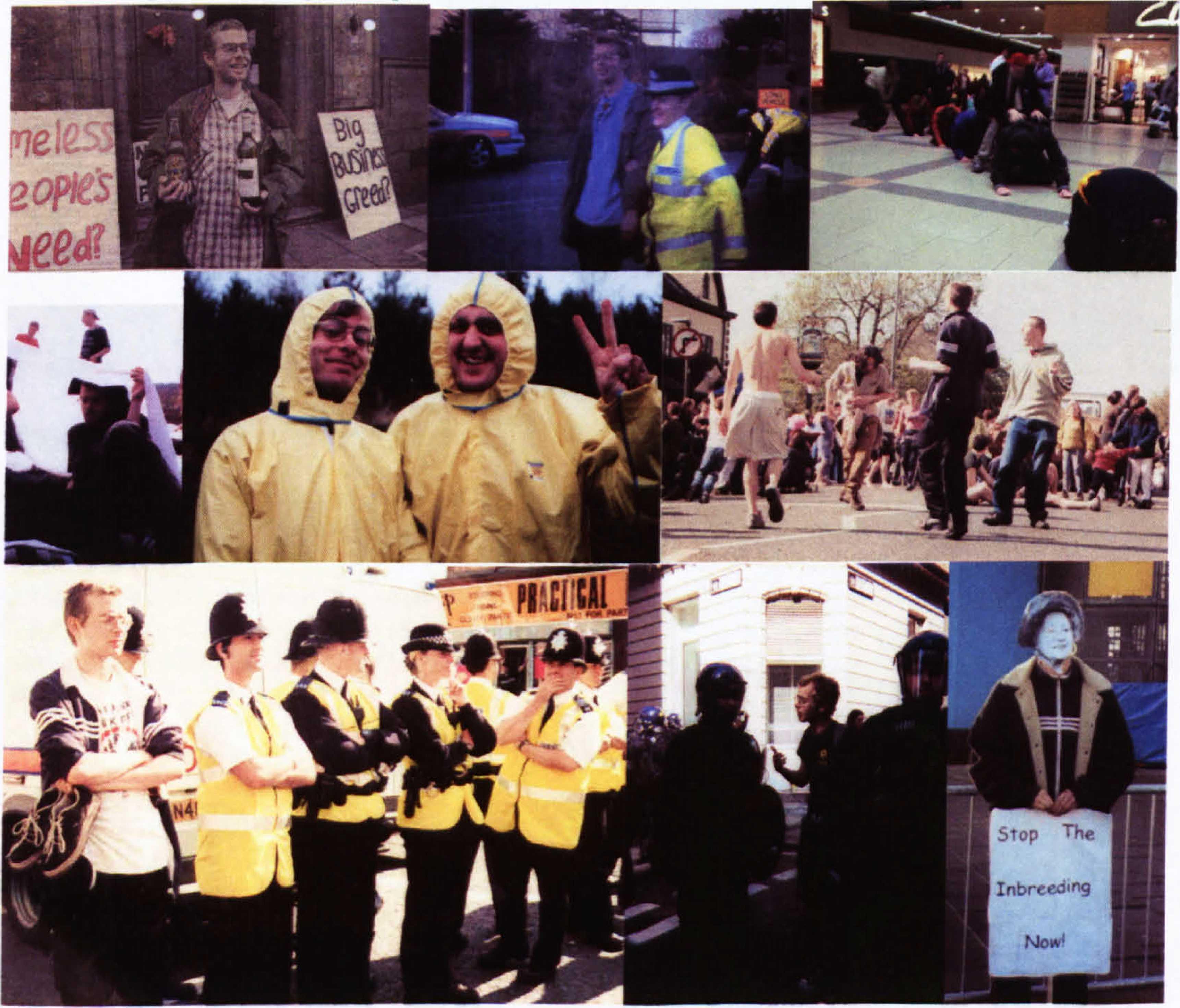

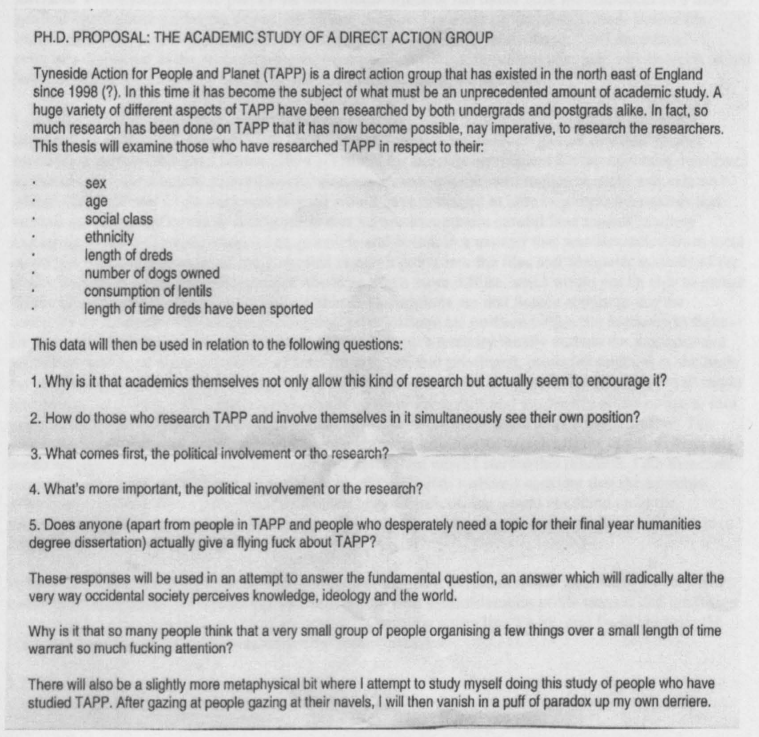

3.4 Tyneside Action for People and Planet

3.4.4 Experiencing Insider Ethnography

3.4.5 Usefulness & Reciprocation

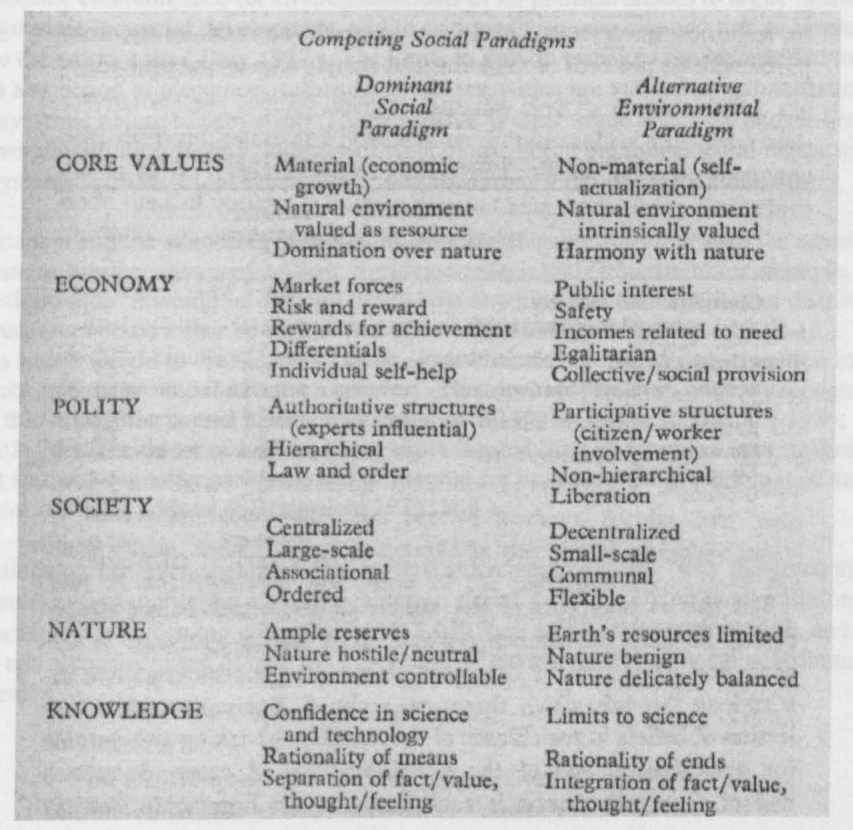

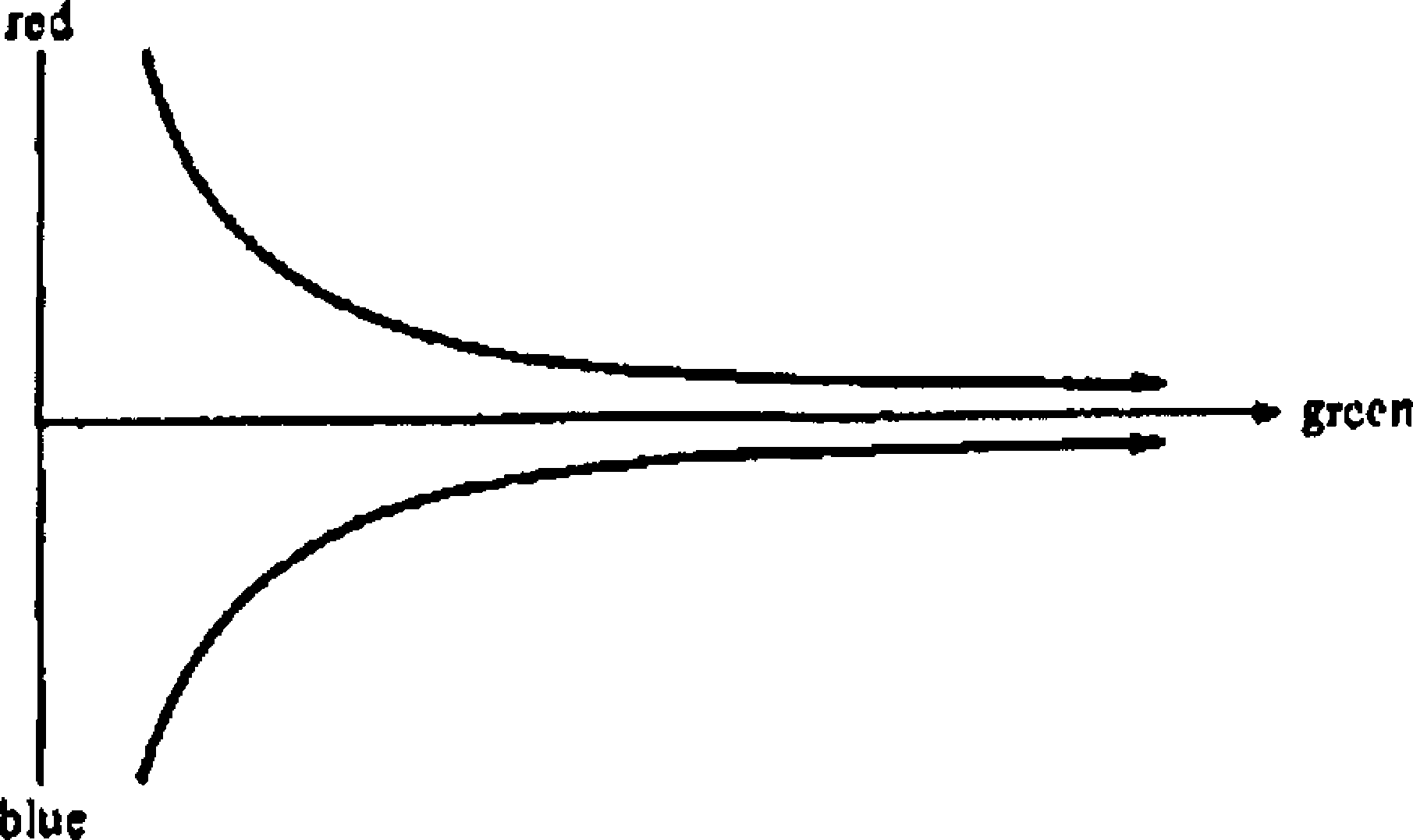

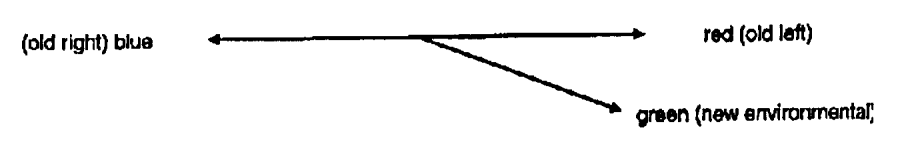

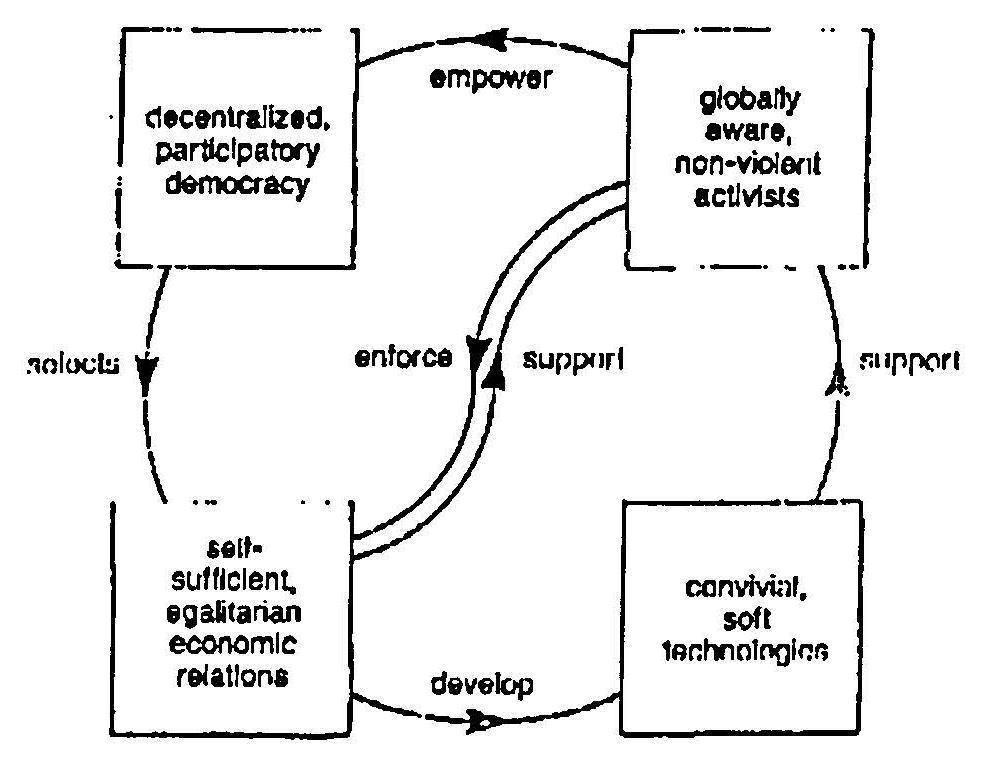

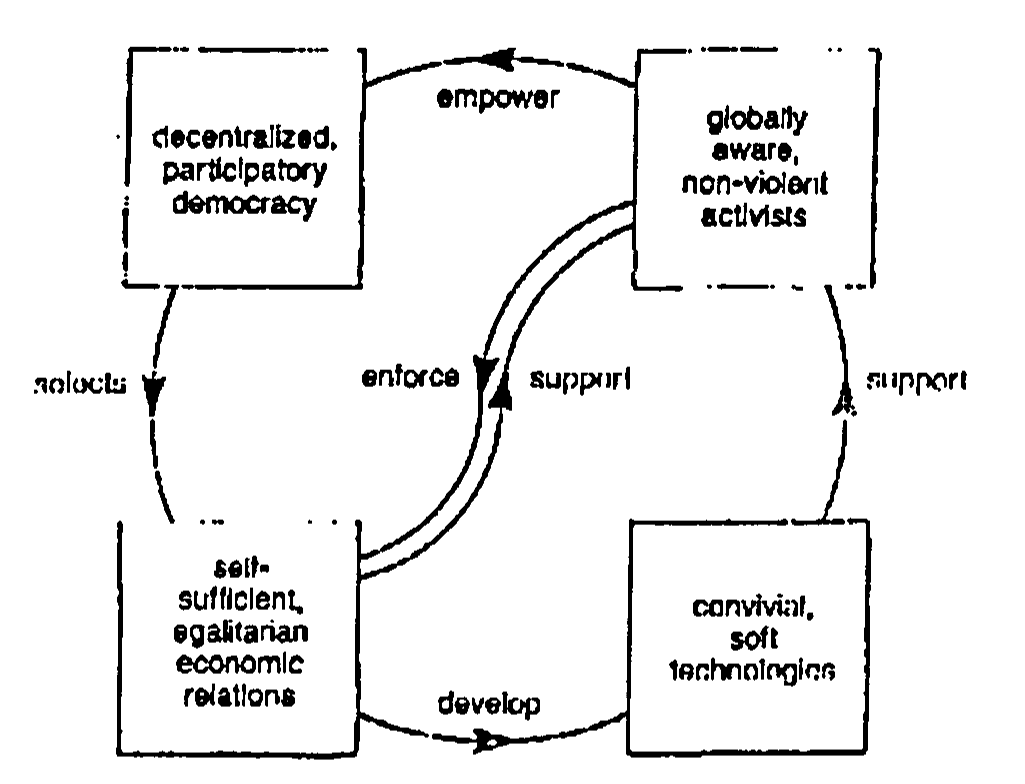

4.2 The Nature of Green Radicalism

4.2.1 Radical Environmentalisms

4.2.2 Environmentalism through Practice

4.2.3 The Environmental Problematic

4.2.4 Green Ideas and Political Traditions

4.3 Anarchist Guides to Action

4.3.1 Eco-anarchist critique of capitalism

4.3.2 Eco-anarchist critique of the state

4.3.3 Inadequate Green Strategies

4.4 Green Radicalism: Conclusion

5. Activist Anarchism: the case of Earth First!

5.2.1 An Institutionalised Environmental Movement

5.3.3 Earth Firstl’s Arrival in the UK Environmental Movement

5.3.5 Strategy, Protest Repertoires and Issue Range

5.3.6 Anticonsumerism and Positive Action

5.3.8 EF! Organisation and Identity

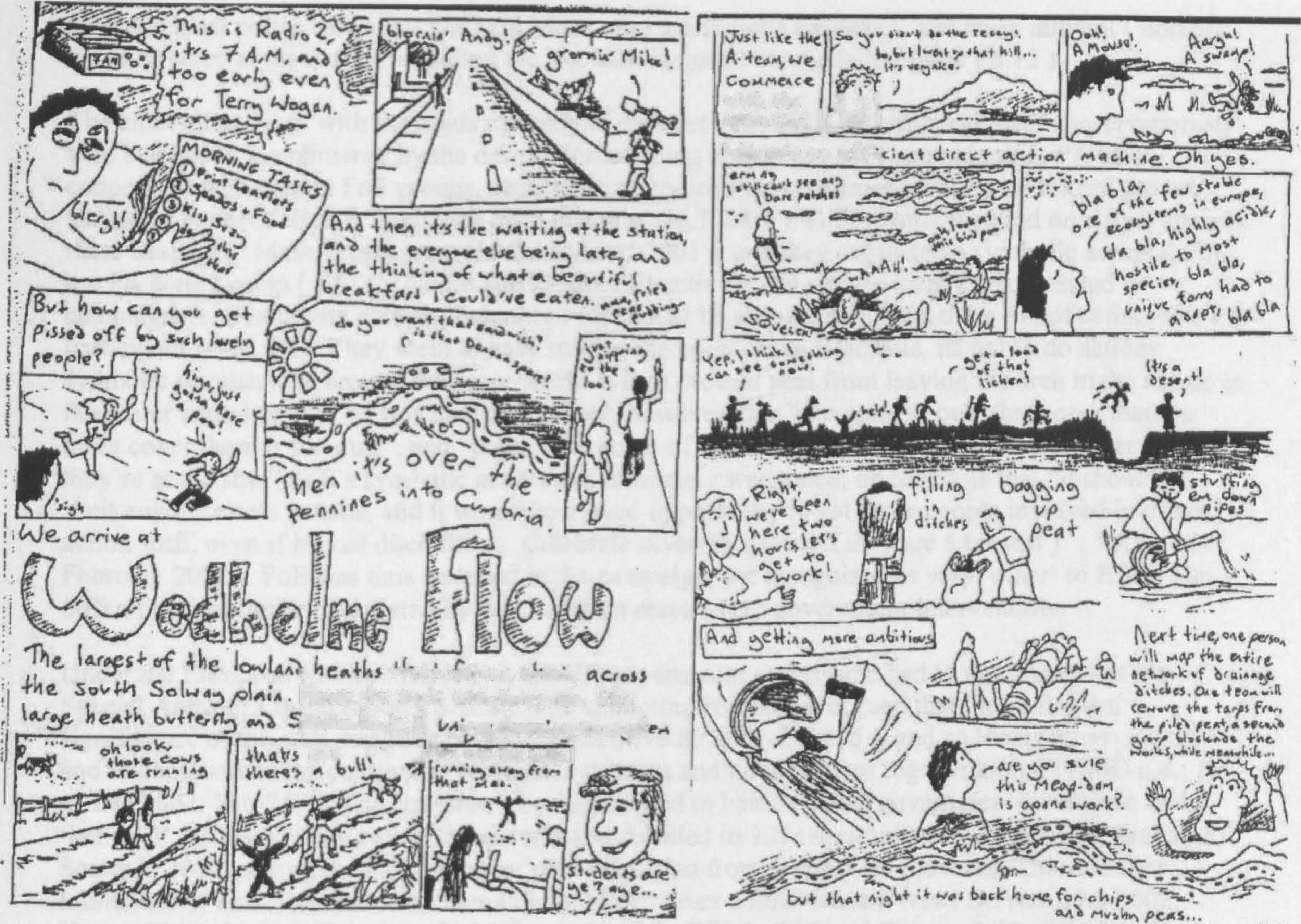

6. Conflictual Strategies of Action: Violence, GM Crops, and Peat

6.2 Defining Anarchist Direct Action

6.3 Violence and Direct Action

6.3.3 Anarchist Perspectives on Violence

6.3.4 Civil Disobedience Discourse

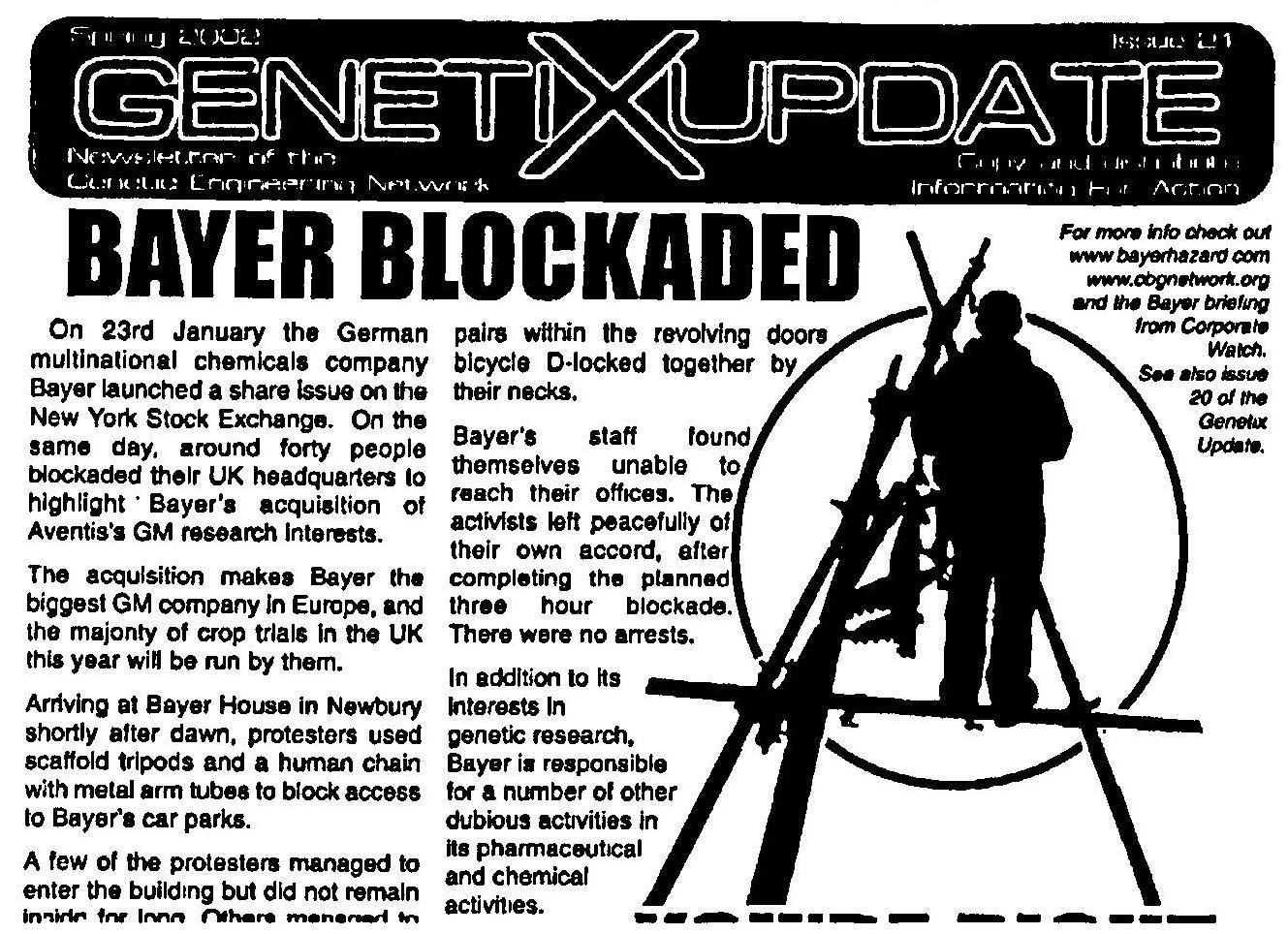

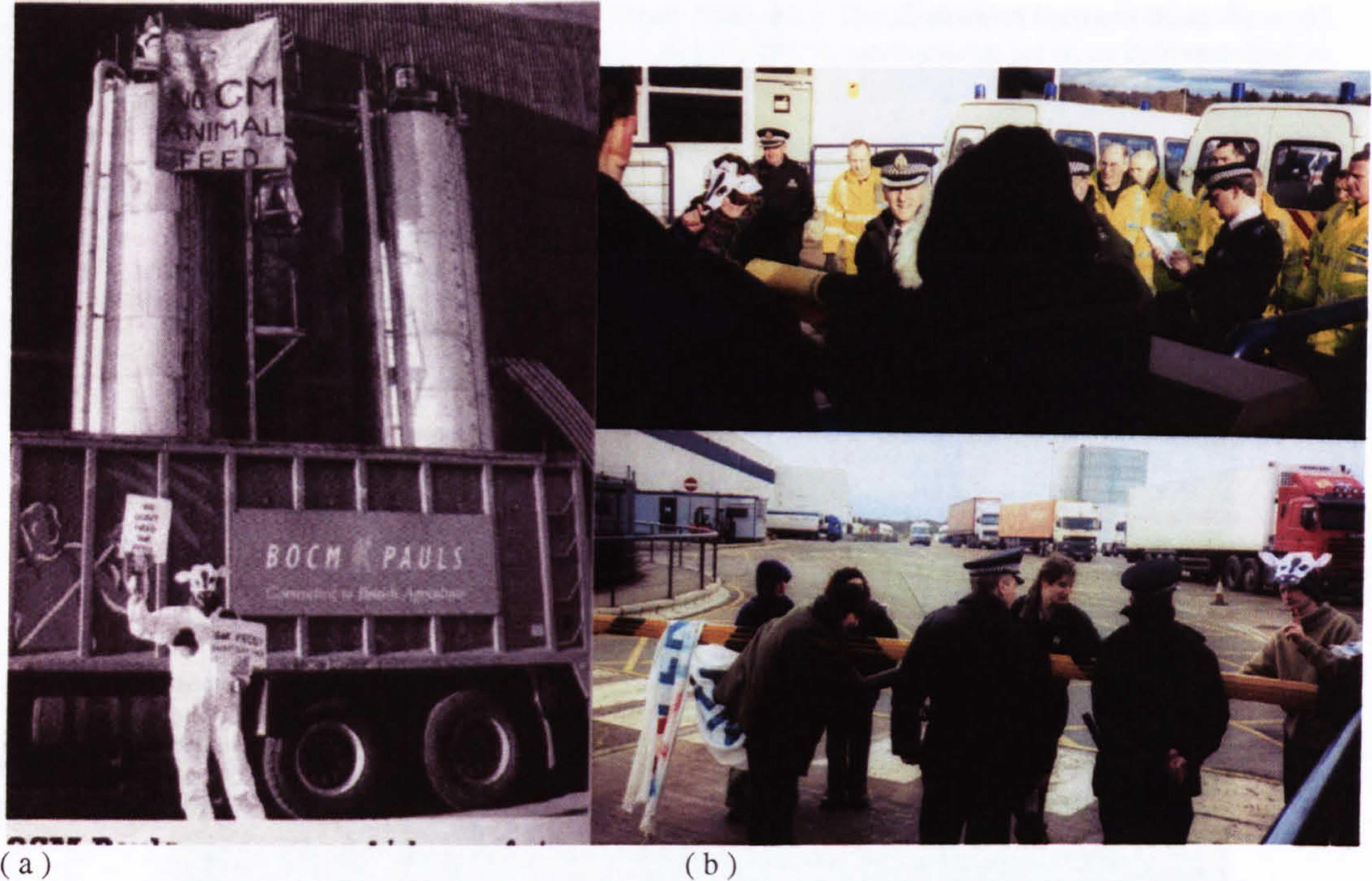

6.4.3 Forms of Anti-GM Direct Action

6.4.4 Genetics Snowball and the Covert-Overt Debate Genetics Snowball and the Covert-Overt Debate

6.4.5 Anti-GM Direct Action: Conclusion

6.5.3 Anarchism and the Earth Liberation Front

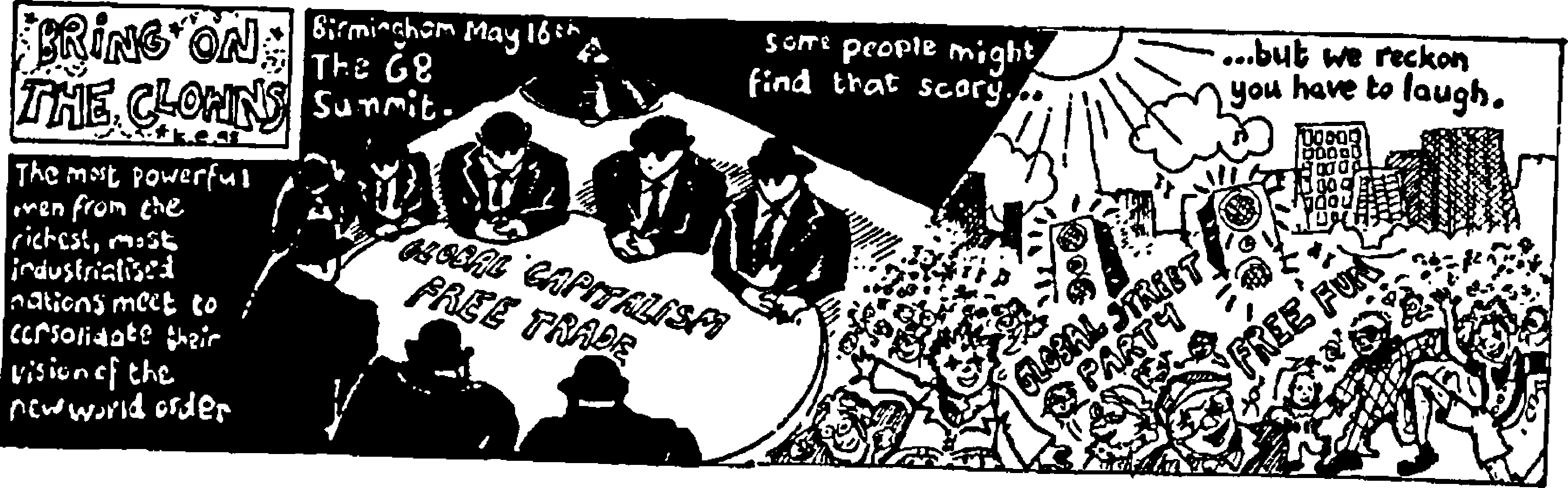

7. Reclaim the Streets and the Limits of Activist Anarchism

7.2 Reclaim the Streets in London

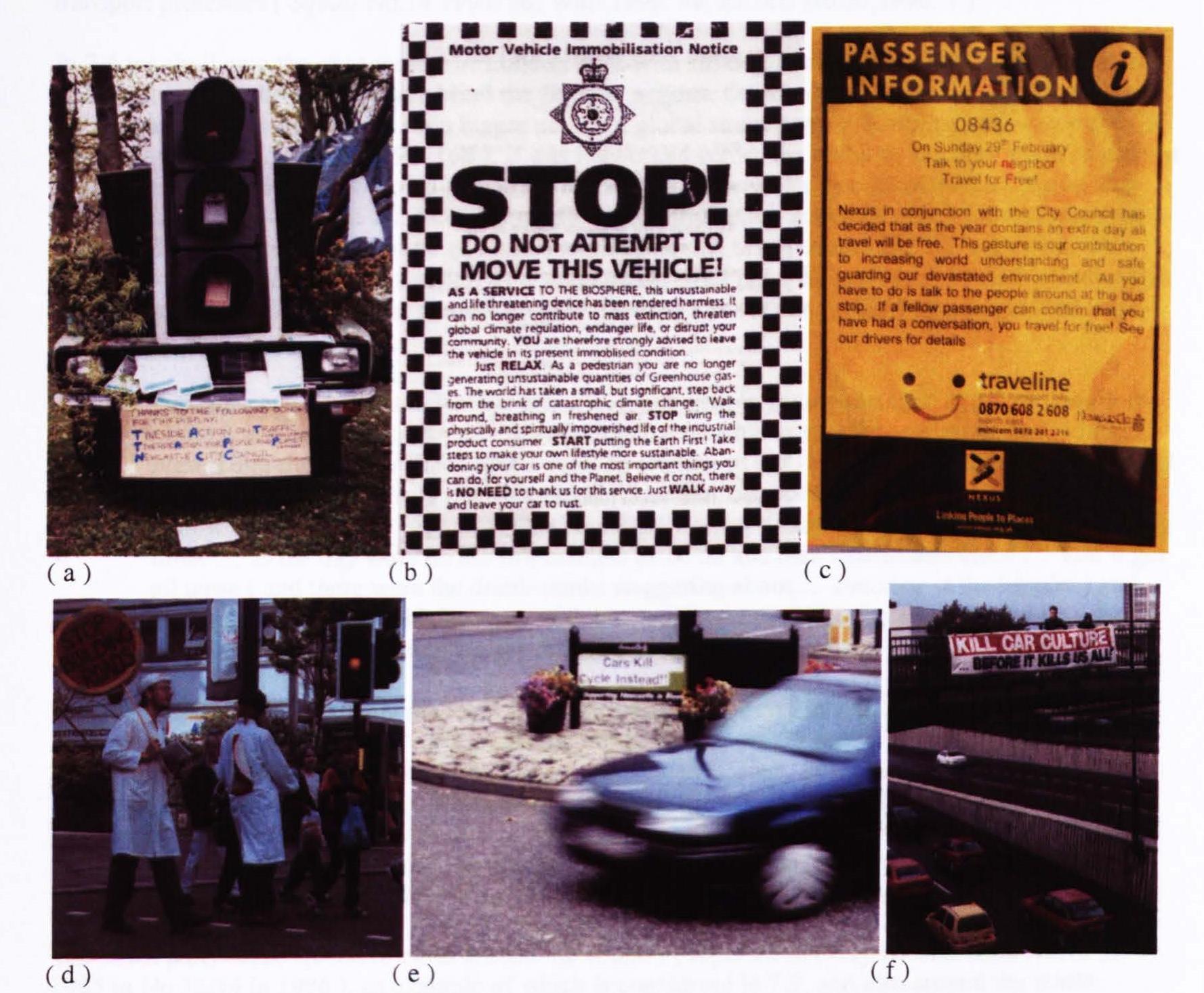

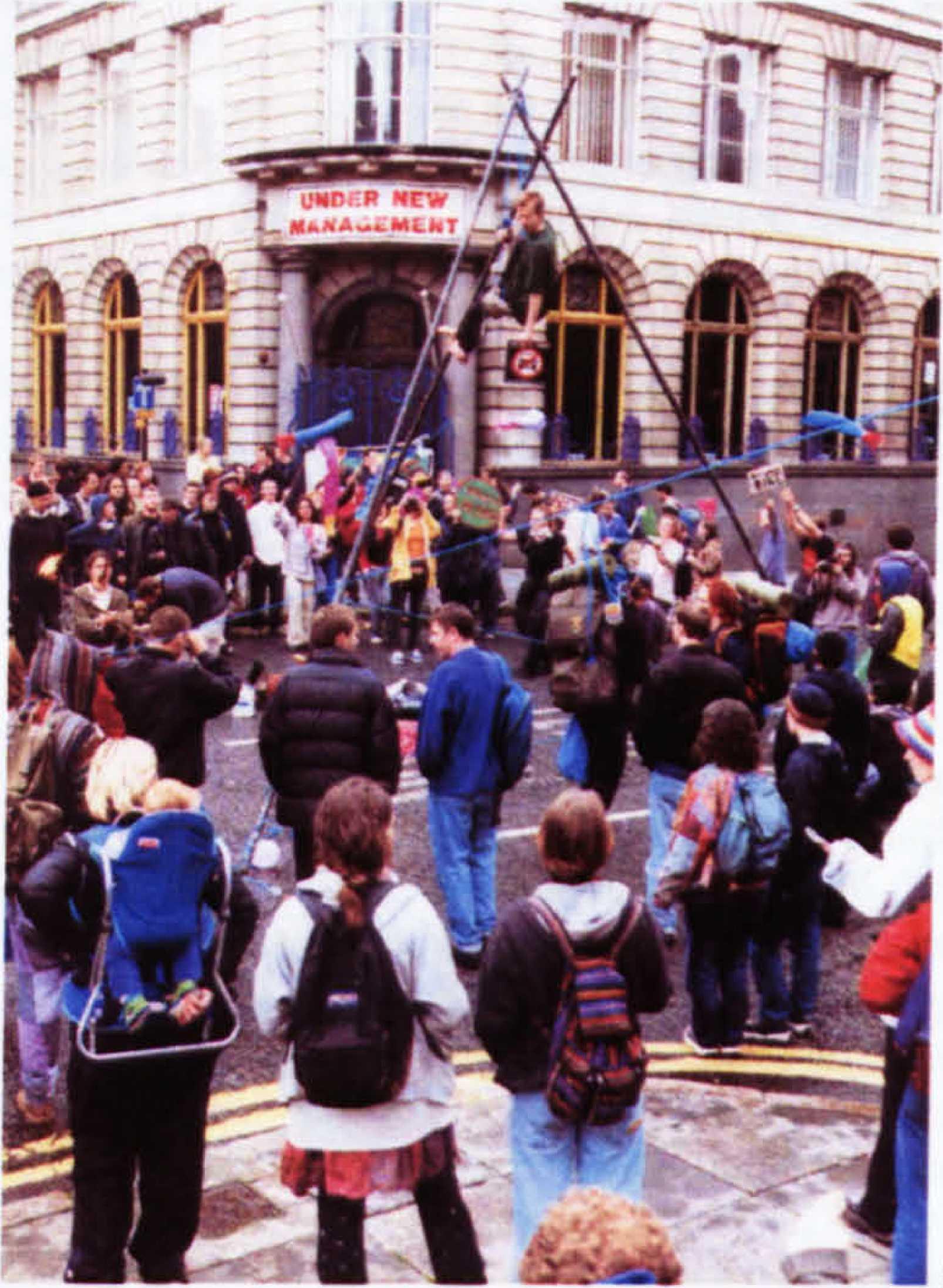

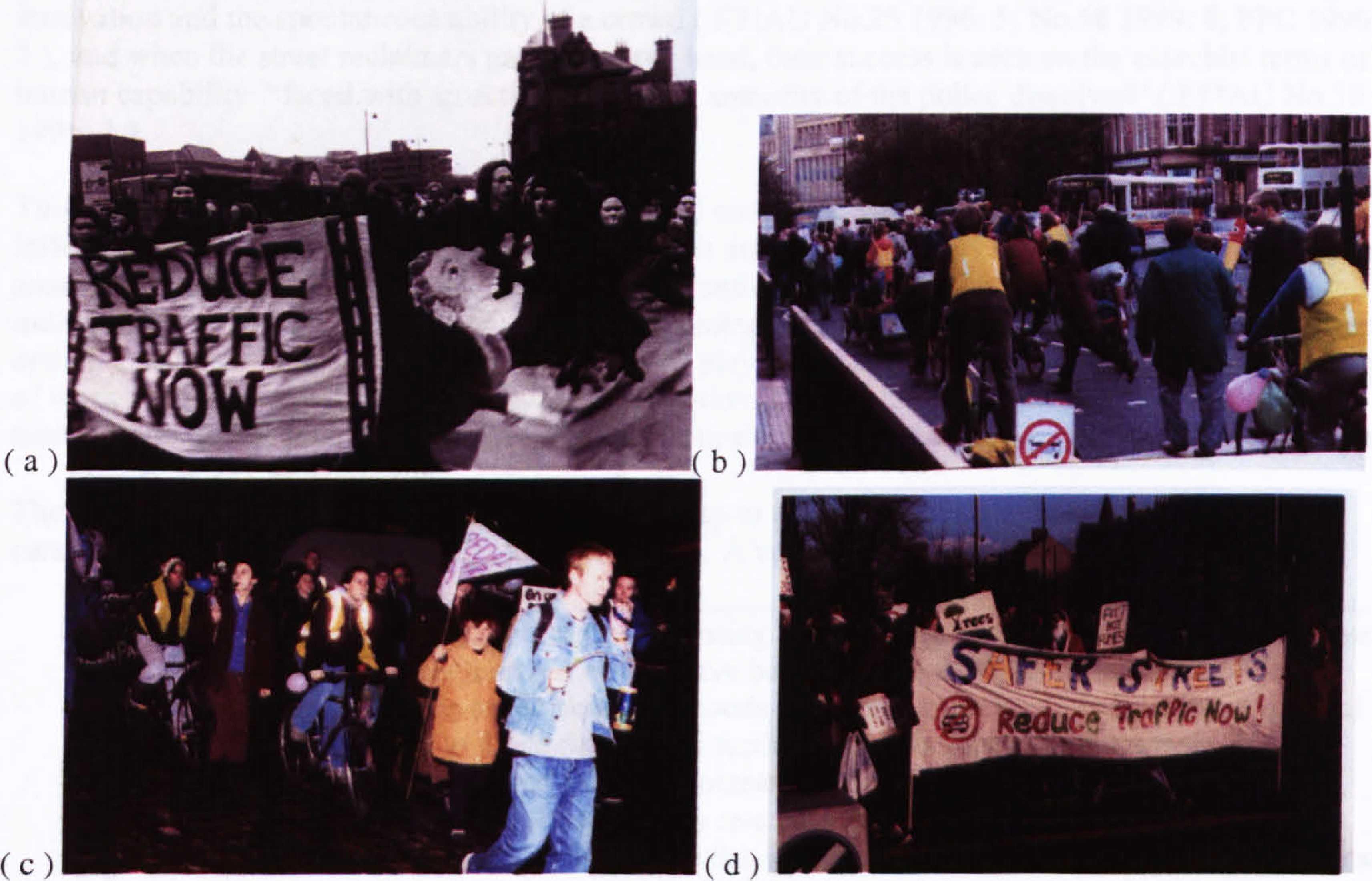

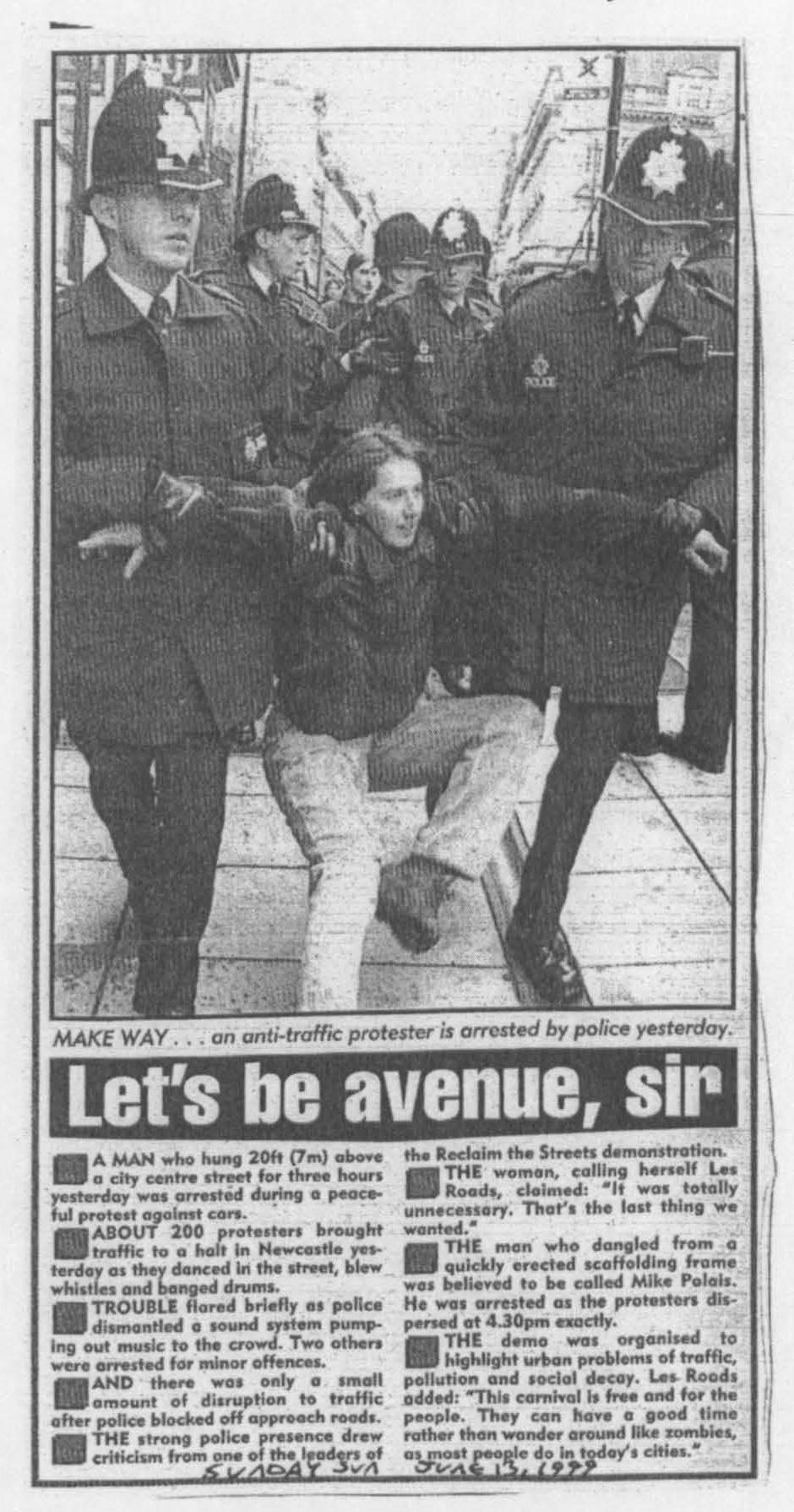

7.3 Reclaim the Streets in Newcastle

7.4 Anarchist Dimensions of RTS

7.6 Reclaim the Streets: Conclusion

Appendix: TAPP: how we talked about what we did...

The ‘Do — it — Yourself’ ethos

Abstract

In this thesis I study the radical environmental movement, of which I am part, by combining the analysis of texts and the textual record of discussions with my own extensive participant observation. More specifically, I look at the direct action undertaken by radical eco-activists and examine the relationship between this and the anarchist tradition.

My research demonstrates, first, that anarchism is alive and well, albeit in a somewhat modified form from the ‘classical anarchism’ of the 19th and early 20th centuries. In researching today’s direct activists, therefore, I have also been examining the nature of anarchism itself. I show that anarchism is to be found most strongly in the dialogue that takes place between activists on the ground, engaged in practical struggles. It is from here, in the strategic debates, self-produced pamphlets, and open-ended discussions of radical environmentalists focussed on practical and immediate issues, that I draw much of my data and ideas.

In pursuing this project, I present an understanding of anarchism as a pluralistic and dynamic discourse in which there is no single, correct line on each issue. Instead, the vigour of anarchism is revealed through the dissent and reflexive debate of its practitioners. This understanding of anarchism, while contrary to a static project of ideological mapping or comprehensive summary of a tradition, may be in keeping with both contemporary theory, and also the anarchist tradition itself. To pursue this understanding of anarchism, I elaborate an ‘anarchist methodology of research’ which is both collective and subjective, ethically-bounded and reflexive. This draws on the experience of politically engaged researchers who have sought to draw lines of consistency between their ideals and the practice of research.

The various forms of ecological direct action manifested in the UK between 1992 and 2005 provide the main source material for this thesis. I survey the practice and proclamations of anti-roads protesters, Earth First!, GM crop-trashers, peat saboteurs, Reclaim the Streets and others, particularly my own local group, ‘Tyneside Action for People and Planet’. Also considered are the explicitly anarchist organisations of the UK, and the direct action wings of related social movements. Comparison with these non-ecological movements serves to highlight influences, alternatives and criticisms across the cultures of anarchistic direct action, and contributes to the overall diversity of the anarchism studied.

Acknowledgements

My parents, Tim Gray, Laura, Suzy, assorted Palais people, friends and TAPPers for their support, as well as everyone else who’s asked ‘have you not finished it yet?’ And of course to that small minority of people who continue to put their bodies on the line, refuse to accept passivity and despair, and make good our connection to the earth. I am privileged to have met a lot of wonderful people involved in grassroots politics and EDA. Ross McGuigan, June Wolff and Joe Scurfield are just three of those that have inspired and given me hope. RIP.

Acronyms

| ACF | Anarchist Communist Federation (until 1999) |

| AF | Anarchist Federation (formerly Anarchist Communist Federation) |

| ALF | Animal Liberation Front |

| CD | Civil Disobedience |

| CJA | Criminal Justice Act |

| CJB | Criminal Justice Bill |

| CND | Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament |

| CNT | Spanish Anarcho-Syndicalist Union |

| CPRE | Campaign for the Protection of Rural England |

| CW | Class War |

| DA | Direct Action, magazine of the Solidarity Federation |

| DAN | Direct Action Network |

| DANE | Disabled Action North East |

| DD | Discussion Document |

| DIY | Do It Yourself |

| DOT | Department of Transport |

| DSEI | Defence Systems Equipment International (arms fair) |

| DTEF! | Dead Trees Earth First! (Publishing Collective) |

| EDA | Ecological Direct Action |

| EF! | Earth First! |

| EF!A | Earth First! Action |

| EF1SG | Earth First! Summer Gathering (UK) |

| EF1US | Earth First! USA |

| EFIJ | Earth First! Journal (USA) |

| ELF | Earth Liberation Front |

| ENGO | Environmental Non-Governmental Organisation |

| EZLN | Zapatista Army of National Liberation |

| FoE | Friends of the Earth |

| GA | Green Anarchist, UK anarchist magazine |

| GAy | Green Anarchy, US anarchist magazine |

| GE | Genetic Engineering / Genetically Engineered |

| GEN | Genetic Engineering Network |

| GM | Genetically Modified |

| GMO | Genetically Modified Organism |

| GS | Genetix Snowball, accountable direct action campaign against GM crops |

| GVGS | Gathering Visions, Gathering Strength, activist conference |

| HLS | Huntingdon Life Sciences, animal experimentation centre |

| ICFL | International Centre for Life |

| IMF | International Monetary Fund |

| IWW | International Workers of the World, Anarcho-Syndicalist Union |

| JI8 | June 18th, Carnival Against Capitalism, London and around the world |

| JSA | Job Seekers Allowance |

| MEF! | Manchester Earth First! |

| N30 | November 30th 1999, International day of action against the WTO summit |

| NALFO | North American Liberation Front Office |

| NSM | New Social Movement |

| NUS | National Union of Students |

| NVDA | Non Violent Direct Action |

| OPM | Free Papua Movement |

| PA! | Peat Alert! |

| PGA | People’s Global Action |

| RA! | Road Alert! |

| RBE | Radical British Environmentalism, 1998 activist-academic conference |

| RMT | Rational Motivations Theory |

| RSPB | Royal Society for the Protection of Birds |

| RTS | Reclaim the Streets |

| SDEF | South Downs Earth First!, UK group |

| SHAC | Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty |

| SM | Social Movement |

| SMO | Social Movement Organisation |

| SolFed | Solidarity Federation |

| SWP | Socialist Worker Party, UK’s largest Leninist-Trotskyist party |

| TAPP | Tyneside Action for People and Planet |

| TGAL | Think Globally, Act Locally, activist newsletter |

| TLIO | The Land is Ours |

| TMEF | Toxic Mutants Earth First! |

| TP | Trident Ploughshares (formerly Trident Ploughshares 2000) |

| TP2000 | Trident Ploughshares 2000 |

| U | Update (UK) |

| WCEF | Working Class Earth First! |

| WT | Wildlife Trusts |

| WTO | World Trade Organisation |

| Other acronyms are titles of texts listed in the bibliography. |

1. Introduction

1.1 Introduction

In this introductory chapter I state the aims and central themes of my project of research into environmental direct action and its relationship to anarchism. I consider the reasons why I got interested in the topic, and the approaches I have taken to it. I situate my own project in relation to seven flawed approaches to combining environmentalism and anarchism. I then introduce the methodology I use, and I ground it in an anarchist ethics, which I introduce in terms of my approach to anarchist theory itself. I present my understanding of anarchism as not a fixed, static system, but a diverse, dynamic flux of arguments, ethics and practice that is constantly re-constituted through debate. I then provide an outline of chapters before moving into Chapter 2, Anarchist Theory, which provides the theoretical background for the thesis.

1.2 The Project: Anarchism in Environmental Direct Action

In this thesis I am treating environmental direct action (EDA) as an anarchist phenomenon. I maintain that it belongs in the anarchist tradition and can be best understood according to anarchist terms. This

challenges positions both within the anarchist camp, and within standard studies of environmental protest and green radicalism. My thesis refutes those anarchists who consider anarchism to be an outgrowth from and intimately tied to class-struggle, and those who consider the only ‘real’ anarchism to be that of the explicit anarchist organisations. It also refutes those who consider ‘traditional’ anarchism to be outdated, and no longer connected to the ‘post-anarchist’ or new ‘pro-anarchy’ expressions (POO 1998:2). I also argue against interpretations of environmental protest that view it in state-centric terms as ‘lobbying by other means’ — an expression of civil society and NGOs — and those who dismiss green radicalism as a merely single-issue or ‘bourgeons’ radicalism.

It is my view that anarchism can be found in the dialogue of activists talking and acting together. I am therefore challenging the tendency to conflate anarchism with a ‘canon’ of recognised thinkers and texts, and anarchist history with a history of the ‘official’ anarchist movements. I also oppose those who seek to construct a static ‘system’ of anarchist thought, and those who exclude insufficiently orthodox, ‘coherent’ or explicit actors from the anarchist fold. My approach stands as the opposite to those who would discount every ‘hybrid’ or ‘woolly’ anarchist perspective, and build walls around the accepted anarchist positions. To me, there is no pure anarchism, only a living anarchism: one that is grounded in real situations and practices, and which can be heard, seen and felt in actual life. I apply a dialogic perspective that maintains it is the meaning produced between actors, between positions, and done so in the real world as applied to practice, that constitutes the strength and substance of anarchism today. I will state more of my view of the existence and theoretical basis of anarchism in section 1.5, and explore it at more length in Chapter 2.

I undertook this thesis project as an environmental activist interested in exploring and interrogating the ideas and practices that, at the end of the twentieth century, I was getting ever more involved in. My background values therefore already included ecological ethics (low- or anti-consumerism, conservation activities, a ‘holism’ that seeks congruity between personal and political practices, a prioritisation of ‘free’ nature over notions of economic ‘progress’ or ‘mankind knows best’) and proclivities for autonomous, self-directed action (including an occasionally romantic identification with past heretic, anarchist and alternative movements). I had read and absorbed much of the basic ‘lessons’ of anarchism, but my practical experience came more from environmental protest and lifestyle or co-operative ventures than the ‘traditional’ class-struggle anarchist movement These background factors undoubtedly influenced my reading of anarchism, and my reading of EDA.

As an interpretative theory, I believe anarchism can hold its own against its rivals today, and provide a framework through which the political events of the world can be viewed. It is from this assumption that I began this research, because in a personal sense I consider myself to be an anarchist. My sensibility, my ethical principles and my critical view of the world are all informed by my reading of anarchist theory. In a certain sense therefore I consider anarchist political theory to be ‘true’. So while I did not deliberately undertake this research in order to prove the validity of anarchism, it has naturally resulted in such a consideration. This is not to say that I consider anarchist perspectives (any more than anarchists themselves) are automatically correct in every sense. Rather it means that I concur with the general thrust and direction of anarchist inquiry, and I share in many of the underlying values that inform it. I consider that this background ‘feel’ for anarchism does not blunt the critical eye, but rather informs it and guides it to the salient places of stress, contradiction and innovation.

1.3 Literature Review

I have integrated my literature review throughout the chapters of this thesis, so my consideration of other writers’ views is contained within the chapters for which they are relevant. However, in order to show how my thesis is positioned within the literature, I will now present two brief surveys. First, I present a somewhat abstract and stereotyped outline of seven alternative approaches that have been brought to bear on the relationship between anarchism and environmentalism. I do this in order to highlight the flaws and limitations of these (necessarily simplified) approaches, and to position my own approach against them. This is followed by a survey of those contemporary researchers who have studied subjects in a manner most similar to my own approach. My aim in these two surveys is to clarify my approach in relation to what it is not, and what it shares similarities with.

Assessments of the connections and affinities between anarchism and environmentalism tend to shallowness, abstraction or tangentiality. It is not that there is a dearth of such assessments — both celebration and critical analysis — but to those of us engaged and experienced in both anarchist and environmental practice, they often fail to ring ‘true’. I will here criticise seven generic attempts to join the two, beginning with the two forms closest to my own perspective.

(1) Attempts to link anarchism and environmentalism that have been advanced by anarchist writers such as Bookchin (1971), Woodcock (1974), Purchase (1994) and the ACF (cl991), have tended to abstraction, reductionist readings, and uncriticality. They speak of ‘anarchism’ in an overgeneralised and oversimplified way, as if it can be captured within a neat, static characterisation, and they apply it to an equally simplified, indeed bowdlerised version of ‘ecological thought’. They tend to rely upon a few quotes and examples from a very limited selection of green texts, and a highly selective reading of ‘ecology’ which is scientifically suspect and, in its theoretical ungroundedness, fails to add to our appreciation of the actual, real complementarities between the two discourses. I challenge these readings by characterising and operationalising an anarchism and green thought/practice that is defined by a diverse, context-specific and contested interplay of positions, and also by drawing for my sources from a broader and intrinsically diverse range of green, anarchist and activist voices, the context of which I take pains to include.

(2) One might think the above deficits might be remedied from studies coming from within the academy — particularly from theorists sympathetic to the values and intentions of anarchist/green practitioners. It is true that such studies often confirm the potential anarchism of green activists and serve to deepen our understanding of certain aspects of activist practice. Yet they rarely go beyond a recognition of ‘these greens are anarchist’: they treat this as a conclusion instead of a hypothesis to be demonstrated (O’Riordan 1981; Hay 1988; Pepper 1993; Eckersley 1992; Dobson 1995). In my thesis I seek to establish this affinity early on and then utilise the case studies to draw out ‘what happens next’: what exactly the recognition of green anarchism might mean, in what ways it is expressed, what consequences it might have for activist strategy and impact, and for our understanding of anarchism itself. I also seek to demonstrate and contextualise specific perspectives and sites of anarchism, constructing a bridge to take specific arguments (more in-depth than generalised abstractions) into

new contexts — specifically EDA — to see how and whether they apply, and what can be learnt from the attempt. This is an anarchism of real arguments; an anarchism of ethical context and practical application. It is not an empty rhetorical position hypothesised between other (Marxist or liberal) green positions, nor an essentialised label that ignores actual practice and discourse.

(3) Those who seek to ‘build’ a picture of green thought (Goldsmith et al, 1972; Porritt 1986; Naess 1991; Hayward 1994; Dobson 1995) have earnestly struggled to apply the right words, the right values and the right political perspectives to their project Many of these values and perspectives are either drawn from anarchism or coincidentally restate anarchist themes, yet the conscious recognition and consequent nuancing of these themes tends to be lacking, and so the anarchism remains archaic, static or incomplete (not joined together), and the anarchist perspectives are prone to recontextualisation within a non-anarchist, ahistorical and even mystical theorisation. The structures of green thought thus presented are abstracted from practice, rarefied and generalist like the anarchist models in (1), above. The political repertoires linked to them, furthermore, have failed to address or accept the anarchist view in its depth: this means they either remain outside my orbit in their electoralist or capitalist liberalism, or they again take the need for anarchist repertoires as conclusion, instead of starting point.[1] I discuss anarchist and green strategies further in sections 4.3.3 and 4.3.4.

(4) Others addressing the same topic of green radicalism, having perceived this lack of criticality and historical awareness, have unfortunately tended to utilise not anarchist but Marxist perspectives and lessons to fill the gap, to draw upon for critique, and to provide advice (Pepper 1993; Martell 1994; Luke 1997; Red-Green Study Group 1995). The Marxist heritage (productivist, anthropocentric, economistic) has proved highly unsuitable for this role, and the strategic lessons it provides are woefully inappropriate (Bookchin 1971; Atkinson 1991; Eckersley 1992; Marshall 1992b; Carter 1999). Anarchism, in taking the question of social relationships and power structures as central, can give us much more insight into the possibilities and problems of grassroots environmental practice.

(5) Uber-critical eco-anarchists, seeking to avoid any and all problematic or ‘impure’ examples from the anarchist past, have sadly resorted to the simplest but crudest solution: jettison the lot (Anarchy: A Journal of Desire Armed} Green Anarchy} Black 1997; Jarach 2004). Thus the primitivist school, for example, presents us with a confusing and frustrating mixture in which thorough critical analysis and healthy anarchist attitudes are framed within an unnaturally bounded and codified ‘ism’ (Moore 1997; Watson 1998; BGN 2002). I have found the tendency to precious separation from and hostility to, other anarchist and libertarian green currents particularly frustrating in that much genuine and profound theorising is taking place amongst primitivist or anti-civilisation circles. I discuss the primitivist stream further in section 2.3.3

(6) Others, anarchists of different schools or eco-activists seeking to build their radicalism anew, have also tended to reify and render static their own position/tradition and that of their opponents (Bradford 1989; Bookchin & Foreman 1991; Bookchin 1995a; Clark [J] 1998; Bonanno c2000). In the worst examples, this has resulted in the absurd position of a reductionist, false anarchism being pitted against a reductionist, false eco-radicalism. If nothing else, these examples provide proof that partisan, engaged analysis is not automatically superior to the academic form. Even within UK activist discussions, textual expressions tend to follow the mistakes of this tendency, solidifying and simplifying particular versions of anarchism or ‘correct’ green practice — which are in reality only possible expressions at one particular time — in order to pit them against even more simplified readings of opponents’ views (EEV 1997; GA 2000).

(7) Militant environmental practitioners, who have produced their anarchism spontaneously and intuitively, have failed to appreciate the diversity and roundedness of historical anarchist lessons. Thus US EF! which, in the early nineties, presented the most inspirational, energetic and influential practice for UK EDA, and which developed intuitively anarchist organisational and political practices with remarkable success, allowed stereotype and prejudice to inform its view of anarchism instead of taking a more ‘generous’ approach: and drawing the best from the tradition (which I seek to do). Practical implications of this were seen in its early years when US EF! allowed racist and severely authoritarian statements to go uncombatted, not least because it had avoided applying anarchist ethics out of a distinctly American fear of revolutionary leftism. Within the UK grassroots EDA milieu, the tradition of anarchism and radical revolts has more readily been embraced, albeit often in a self-consciously

non-industrial version (in the US, the situation has now also shifted in this direction), but misunderstandings and simplifications are still widespread.

It is because of the flaws in the above approaches that I consider eco-anarchism to require another assessment, and I have adapted my own approach to seek to remedy these flaws, or at least to avoid repeating them. With this in mind, I feel compelled to note that, in this very survey, I have demonstrated a similar over-generalisation, over-simplification, and general ‘over-doing’ of the certainty of my critical assessment It is intended only to clarify the perceived errors that have informed my own approach. I do not wish to suggest that I am somehow above and beyond the above readings, and I do not reject the commentators and texts cited above. Rather I use characterisations and critical tenets presented by them to inform my own work, seeking to take the best and the most useful elements, and re-apply them in a dialogue with activist debate.

Having identified the flaws and limitations in the above approaches, I wish now to look at those individual researchers who have conducted research in a manner which, when viewed together, I would suggest might constitute an appropriate anarchist approach to research, and to theory, and with which I wish to affiliate my own project. I will draw upon their insights at relevant points in the thesis, but my intention in these next few paragraphs is to distinguish their approaches, and topics of concern, from my own.

It is a critical realist (Wall 1997: 9–10) who has produced the most in-depth analysis of nineties EDA (Wall 1999a), but in Chapter 3 I distinguish my approach from that of critical realists — including those with some sympathies for anarchism, such as Wall and Cox (1998). Wall’s work, while crucially valuable as a historical document of the processes by which Earth First! and the anti-roads movement developed (an achievement which I do not seek to repeat here), has an artificially narrow field of vision when viewed in anarchist terms. I consider it damning of the broader approach of social movement analysis that, as Goaman states, Wall fails to capture the “ethos, spirit and impulse that underpins people’s involvement in Earth First!”. His deployment of a “Theoretical approach deeply lodged in conventional sociological concepts ... tends to ‘suffocate’ his account of living movements with irrelevant intellectual baggage” (Goaman 2002:15). The same could be said of many academic accounts. Plows records that Wall “employs the ‘standard toolbox’ of social movement theories to explain and contextualise direct action mobilisations” (2002b), and Goaman criticises that this means that “Earth First! ideas, with their profound ethos of libertarianism and the rejection of scientific reason and instrumentalism, are reduced to a set of instrumental scientific processes — diagnosis, prognosis and a calling to action” (2002: 16). As Plows indicates, however, Wall is by no means the worst offender (Plows 2002b), and similar condemnations have been made of overly formal and instrumental SM research — of Jordan by Welsh (1997: 77–79); of Lent by Plows (Social Movements List 1998); of Melucci by Heller (2000:9); and of Gathering Force by Do or Die (1998: 139–144). Such SM approaches show a tendency both for a “theoretical overextension of concepts” and an “empricial overextension... the tendency to make broad statements about movement dynamics” (Jasper 1999:41). These critiques, expressive of an anarchist perspective, have all informed my own approach.

Karen Goaman’s own thesis focussed on the situationist current within anarchism. She places more emphasis on ideas than on action (2002:58), and views texts as the primary location of anarchist ideas and identity (2002:1–5), arguing that “It is the critical ideas and their dissemination through texts that form common links between persons who participate in oppositional currents” (Goaman 2002: 13). While I recognise, celebrate and benefit from the texts which, Goaman accurately notes, are commonly produced even for “activist oriented interventions” (2002: 58), I position these within a broader context of activism, communal endeavour and experience which cannot be completely captured within the text. I share Goaman’s view that Wall’s study “would have greatly benefited from... an exploration of key texts, ideas, attitudes and affinities that would have been afforded by periodicals such as Do or Die and even the activist-oriented newsletter Action Update” (2002: 59), but unlike Goaman, I do not prioritise certain ‘influential’ periodicals within anarchist circles. Instead I seek to utilise a diverse range of the most articulate or ‘telling’ of the ephemeral pamphlets, ‘discussion documents’ and gathering debates which arise from the milieus and concerns of EDA: this allows a reading of anarchism that contains more nuance and difference. I would also suggest that a problem with Goaman’s project is that it focuses on the individuals involved in producing texts and zines, as if an understanding of their (self-declared) biographies explains the ideas. It is, furthermore, dangerous to pin anarchism on a few selected individuals (although she emphasises she has only used names already in the public domain (2002:255)), both in terms of their personal safety, and in terms of the ongoing vitality of the movement.

Mick Smith’s approach is a little further removed from my own study of direct action, focussing on ethics and the theoretical formalisation of ethics, but I wish to cite him here as an inspiring example of how to take the anarchist approach and use it to engage with and refuse the assumptions of dry theory (1995; 2001a; 1997). His prioritisation of context, experience and personal intuition against abtract theoretical expressions has informed my understanding of environmentalism. Where Smith writes my intended argument in the language and concerns of ethics, Jeff Ferrell writes it in terms of space, spontaneity and experience (Ferrell 2001). Situating himself as a full participant of the marginal street cultures of his topic, he views the margins of the city — the margins of power — as “locations of radical openness and possibility” (Soja quoted in Ferrell 2001:241). But while I share an empathy with Ferrell’s approach and would ally myself with many of his insights, Ferrell’s work is an inspiring celebration not a critical analysis, concerned with an evocation of the anarchist practices of marginal elements in society who practically contest the policing of space. Despite the crossovers, therefore, his project is distinct from mine both in its theoretical concerns, and also in its subject matter (not least for being a study of the US, not the UK).

David Heller’s (2000) examination of peace movement direct action, including Faslane Peace Camp and Trident Ploughshares, includes considerations of the links between action and ideology; the symbolic power of material practices; and the concrete effects of symbolism. His study has taken on board many of the anarchist lessons for social movement analysis. The differences from my own project lie in his subject matter- peace movement direct action not environmental direct action — and his anthropological concerns, in which the rich detail of experience takes the place of a closer and more conscious theoretical engagement with the anarchist tradition. But I consider Heller an exemplary anarchist researcher, and he is very useful for many of the concepts he uses, such as intersubjectivity, non-protest forms of resistance, and practical (and contested) forms of power-with, and other positive forms of (anarchist) power, such as the expression of communal solidarity through song and selforganisation (2000: 145) (see section 2.2.5). It is not that he has invented these concepts, which are quite widespread in EDA, but he gives them a practical academic application and convincingly contextualises them in real settings.

Alex Plows has produced a plethora of articles and papers that celebrate and examine various forms of EDA. These began with articles speaking from her subject position as Alex Donga the road-protester (Do or Die 1995: 88–89; Plows 1995; 1997), and developed according to an ever-greater immersion in the language of SM theory (2002a; Wall, Doherty & Plows 2002). She is perhaps the researcher who I have referenced most frequently and been inspired by most regularly, although the shift toward ever- greater technicality in utilising SM theories at first appeared, to me, to erode much of the power in her earlier work. As with the case of Wall, I found that the dry language created a distance from the ground-level of EDA, and that the frameworks were often more concerned with their own theoretical and disciplinary disagreements than an engagement with the dialogue and practice on the ground: it was in reaction to this, and similar SM-framed approaches to EDA that I immersed myself deeper in an anarchist and not an SM approach. However, more recent papers Plows has undertaken with Doherty and Wall have succeeded in re-transcribing SM language onto what I view as anarchist concerns and anarchist arguments, particularly through the application of Welsh’s (2000) concept of ‘capacity building’ to EDA, and by supporting the anarchist (not liberal) conceptualisation of direct action which I consider in section 6.2.1 (Doherty, Plows & Wall 2003).

Jonathan Purkis is another of the researchers whose research into EF!’s practice has positively informed my own work. Purkis has focussed particularly on the holistic and micro-political aspects of EF! practice, providing a corrective to studies that view direct action solely in terms of moments of conflict In Chapter 5 I draw upon some of his insights, particularly with regard to the radicality or revolutionary quality of EF!. Purkis’ subject matter differs from mine practically, in that he focussed on EF!ers in a different part of the country, and at a period that was at some remove from the bulk of my own fieldwork (2001). He also pursued a sociological line of inquiry which, while similarly grounded in anarchist tenets, was expressive of a discipline and language to which I have had relatively little engagement I consider some of his, and other writers’ analysis of the social ecology — deep ecology variations in EDA to be ‘done’, accepted, and requiring no further academic explanation. Indeed the pursuit of this and similar academic investigations into green ideology (such as ‘post-materialism’ or green consumerism) has enabled me to choose my own area of concern much more finely.

Purkis is identified with those academically-situated anarchists committed to a pluralistic and activistsupporting anarchism (Welsh & Purkis 2003: 12; cf Chesters 2003b), many of whom have written in the journal Anarchist Studies, Another of these, Graeme Chesters, presents another exemplary example of a partisan activist-academic (he is also a member of the Notes from Nowhere collective), for example by contributing his academic authority to the defence and public understanding of Reclaim the Streets (2000a; 2000c). Chesters has engaged more with the anticapitalist movement than EDA, and he has proved more concerned with the application of innovative theories to activist practice, such as Melucci’s work on collective identity (1998), or the resonance between complexity theory and antiglobalisation networking (2005). I have not found the neologistic or zeitgeisty terms that excite other theorists (Jordan (2002) is another example) to have had such a marked appeal or connection to my research, however. I have remained more firmly grounded (earthed) in the interplay between the fields of environmentalism and the terms of the anarchist tradition. It is my combination of academic analysis and investigation with a commitment to the interplay of anarchism and environmentalism that makes my work distinct

1.4 Methodology

Chapter 3 is the chapter in which I introduce my methodological approach, and consider the links between my experience, anarchist theory, and their relationship to various ‘progressive’ theoretical approaches to research. I introduce anarchist perspectives on knowledge (and thus on academic activity), and ally this with elements of the feminist epistemological challenge. I demonstrate the sophistication of anarchism’s traditional hostility to top-down, ‘neutral’ perspectives, using the critique of law as example. I find myself unable to usefully apply a purist and ‘more revolutionary than thou’ critique, however, and so I use feminist research tools instead, to chart a path of least-oppressive, least- hierarchical and least-compromised practice. Amongst the qualities cited by feminist researchers, I take the validation of experience over abstract theory to justify my use of practical experience to augment and ground my analysis.

I argue that feminist tools of research, typified by notions of ‘partisanship’; the inclusion of the voices of the researched; and their participation in the research process, are characterised by an anarchist ethic. I distinguish my use of such notions from previous feminist frameworks, however, in that EDA activists are not suppressed subjects requiring kid gloves, but active, dynamic and able agents quite capable of critical assessments and interventions themselves. I also distinguish my approach from the radical aspirations of critical theory and what I consider to be over-simplified leftist urges to ‘unify thought and practice’. Instead, I embrace reflexivity to support a more open-ended, incomplete dialogue with my research subjects.

I apply anarchist analyses to academia, to my own research and also to the notion of activism itself. This serves to situate my position within the research process, and to prioritise my relationship to the activist group ‘TAPP’. Here I ground my ethical considerations by considering how my involvement in the group affected my intellectual development and perspectives; how TAPP’s experience of research throws up aspects of the activist critique of research (such as the irrelevance, the apoliticism, the power relationship, the exploitation of subjects). I conclude with a consideration of how even the ‘best’ research strategies (which I group according to the themes of ‘limits’ and security; the dilemmas of the insider researcher; usefulness; and dialogue) remain problematic to a full anarchist ethics.

Ultimately I gave much less attention to fieldwork, ethnographic research and interviews than I had originally considered, but shifted my primary source of ‘data’ onto publicly available (or at least ‘nonprivate’) expressions, such as gathering debates, ‘discussion documents’, press releases and reports. I then used my extensive insider research and ‘observant participation’ to quietly inform my thesis, and sought to find a liveable, non-disruptive and non-distorting methodology of research. I had to accept an imperfect match, therefore, between the academic urge to record, collate and analyse; and my own life.

1.5 Anarchism in this Thesis

In this section I shall state my approach to anarchism, clarify what is not my approach, and consider how we may recognise anarchism. I must insert a disclaimer, however (the first of many): this is my particular reading of anarchism, and I claim no greater ‘authority’ for it than that For me, the recognition of anarchism comes from the recognition of arguments, not of boundaries: there is no tight definition surrounding what is legitimate and what is not legitimate anarchist practice. Rather there is an identifiable and coherent corpus of ethics, argument and strategy that can be applied — to different degrees — to many different situations.

I view anarchism as a mutually supportive matrix of sentiment, critique and practice. Its hallmarks are (1) an opposition to authority and social domination in all their guises; (2) an ideal of social freedom: an optimism by which the inequities of currently existing society can be critically judged; (3) a drive to act freely, to rebel, to refuse to either passively accept exploitation and domination, or to take part in power games; (4) a faith in the capability of one’s fellow human beings, to agree and to work things out better when there are no interfering state structures; (5) a view of power as corrosive, and a corresponding injunction to develop ways of working that counteract build-ups of power or the exercise of power over others. There are certain outgrowths of these central tenets (which I look at in turn in Chapter 2), including an opposition to liberal institutions such as parliament; anti-capitalism; and direct action, but such particular doctrines are not definitive in themselves: they are merely conclusions drawn. I consider anarchism to have a compatibility — though not a fixed equivalence — with radical environmentalism. Fundamentally, I consider it to be plural and dynamic, capable of embracing many contested and conflictual positions, and I consider also that anarchism can be revealed through practice as much as it can be through text In the following paragraphs I will explain how I have approached anarchism as dialogical and plural discourse, evidenced in texts and practice, debate and application.

A key component of my interrogation of the relationship between anarchism and environmental direct action is the belief that anarchism can be found in the dialogue of activists talking and acting together. I argue that this is the same essential anarchism as was formerly expressed in the ‘classical’ anarchist movements — not identical, but akin at its core. Rather than write a monolithic ‘grand narrative’ of anarchism — fixing it for good; speaking of it in a static way; ‘synthesising’ it into a model -1 deal with anarchism according to what I consider to be its own values — fluidity, collective criticality, an ‘ethic’ underlying discourse and practice. This approach stands opposed to the idea that anarchism essentially consists of certain fixed tenets which can then, like a rulebook, be systematically and identically applied to every case. In the next chapter I do detail key tenets of anarchism (anti-authority; freedom; rebellion; human nature; and power, cited above), but I emphasise the variety of interpretations and combinations that can be assembled out of these. A focus on tenets serves as a way-in to understanding anarchism, not as a conclusion or end-point

The way I have attempted to present an understanding of dialogic and pluralistic anarchism is by presenting and sourcing my argument on the debates of activists. I therefore present opposed voices from newsletters, activist reports, photocopied and re-distributed pamphlets, discussions at gatherings, email discussions, and ‘discussion documents’. These are ephemeral texts rarely covered in the ‘above ground’ literature, ie. they are rarely repeated in their ‘original’ form outside the campaigns and activist circles they come from, despite the fact that they strikingly and consistently reproduce central anarchist concerns, arguments and understandings. The discussions and the activist intelligence and ethos communicated in these circles is distinct from how anarchists (or anarchist ‘interpreters’) tend to ‘present’ anarchism to the outside/public world. Yet these discussions — even though they might be narrowly strategic and tactical; exaggerated and overblown; or rooted to obscure points or miniscule sites of struggle — are precisely where anarchism may be found revealed. I strive to present these debates ‘in context’, so far as possible, because decontextualised they become meaningless. The above points do not mean that I relegate anarchist texts or anarchist history to irrelevance, however. Rather, 1 consciously re-apply perspectives from these sources, and I emphasise how traditional anarchist arguments are re-articulated from within EDA.

EDA also shows many conscious links with anarchist history, and I consider these of inestimable importance. If EDA is to have relevance for future anarchism it needs to keep this interaction/continuity going — to take part in the historical thread of hope, generosity and anger that is the anarchist tradition. I am reintegrating EDA into the anarchist frame, and not in an abstract irrelevant way but through the actual, expressed, recognised and restated demonstrations. I use historical anarchism as a critical judge for EDA practice and attitudes, identify the contrasts in context, and assess what remains linked. This may be seen as a reconstruction of anarchism. Because -1 argue — anarchism is being constructed/reconstructed all the time, that process by which the construction/reconstruction is demonstrated is the anarchist tradition.

Instead of talking about anarchism in the abstract, I take voices from different contexts and see how they fit Much of the editing of these is obviously ‘pre-chosen’ by myself -1 have chosen those which I think fit, support, add depth to, or bring up an interesting clash. I believe they tell a truer, closer story of anarchism than an overarching or a uniform framework — to allow the voices available to guide my structure and argument I celebrate this diversity and draw out the shared, in-common lessons it has for our understanding of anarchism.

There are many positions on anarchism that I distance myself from: I will here list three of the most simple of these. First, I refute those eco-anarchists who say ‘ecology is anarchist’, as if that clears up the matter once and for all. True the two streams appear very sympathetic, and there is enough common ground to allow activists to perform eco-anarchism, but it is worthless (false) to speak of it in the abstract.

Second, instead of high theory — whether critical or ‘postmodern’ -1 focus on actual practising ecoanarchists. This indicates that I refuse to conflate anarchism with trendy contemporary theorisations, but rather keep anarchism’s priority — from which position some themes and tools of postmodern theory may then be used (but within an anarchist framework).

I do not (as some class-strugglists do) say anarchism is only the movement — that anarchist practice equates to the explicit anarchist movement only — and that anarchism emerged, as if spontaneously, from the movement But nor do I exclude those classical/historical/class struggle voices as inherently dead or irrelevant (as some ‘post-left’ anarchists do). Instead I utilise statements from these sources to critically engage with EDA and other anarchist positions. They are a vital part of the whole — legitimate voices within anarchist debate (which, in my view, is close to synonymous with anarchism per se).

I do not think that all anarchisms are equal (ie. that all viewpoints on anarchism are fine). Rather some arguments are superior in some contexts; more impressively coherent; avoid contradictions and pitfalls of other arguments; relate more closely to (what I view as) central anarchist themes and values; and some practices and organisational methods have proved more successful in some contexts (those which have related best to ‘working class’ needs do gain extra merit here). There is a tendency for all sides to overblow their positions — and all of these exaggerations can be pricked as I endeavour to do.

Everything can be criticised (and super-criticality is another of the avowed characteristics of anarchism), but some arguments are more valid than others -1 plump for these as I go. However, this never means the argument is ‘done, finished’ — the other voices in the argument are not invalid if they also reflect anarchist themes and feelings, and intuitive arguments of the anarchist ethos. When one position or tendency appears the weaker, it may, under another light or in another context, appear the stronger, and it can (and does) modify and strengthen its position in the light of the opposition and criticism it faces. I do not suggest there is a developmental ‘progress’ in anarchism — on the contrary, the earlier arguments are often the stronger (and frustratingly, often the weaker arguments have demonstrated most appeal and applicability).

To judge whether an argument or practice is anarchist, certain criteria do apply (see for example Bowen & Purkis (2005:7)). The study of the anarchist conception of direct action as the most useful handle/portal to anarchism is especially useful here, as it contains the ethical tenets of means-ends congruity, self-valorisation, direct not indirect, social not political or bureaucratic, collective and capable of being extended by both existing and other actors. A checklist should include the questions: is anyone being repressed/manipulated? Was the organisation free/ spontaneous/ bottom-up? Are there ulterior motives? Does the practice extend the practice and possibilities of freedom or does it close them down for others? These are themes that I explore in Chapters 5,6 and 7, where I examine the contemporary expressions of eco-activism in terms of the anarchist conceptualisation of direct action as the best guide for assessing the EDA of the case studies.

My reading of anarchism allows large margins — not every voice needs to be consistent with every other, hybrids and contradictory or woolly expressions may all float within the space. So long as they are engaged in dialogue on anarchist terms, share an understanding that reveals key anarchist themes (whatever their particular conclusions), and keep this anarchist argument and dialogue going, I include them. Others — perhaps the majority of explicit anarchists — would disavow such an approach, arguing that only those who are consistently, coherently, tightly anarchist (on their particular readings) deserve to be so called. This is a reasonable position to take, and may be strategically crucial (to keep out misguided, misleading or recuperative tendencies), yet for my academic (non-strategic) reading a broader approach is required.[2]

1.6 Outline of Chapters

The theoretical grounds of the reading of anarchism I presented in section 1.5 are explored and interrogated in Chapter 2, Anarchist Theory. Chapter 2 provides the background and theoretical support for the thesis as a whole, identifying both the key concepts within anarchist ideology (sections 2.2.1 to 2.2.5), and also the nature of anarchism in a broader, more philosophical sense (sections 2.3.1 to 2.3.6). In the first band of sections (those that begin with ‘2.2’) I consider the distinctive anarchist conceptualisations, or key ideological tenets, of anti-authoritarianism; freedom; rebellion; human nature; and power. I consider some of the implications of these tenets for our analysis and understanding of anarchism, and in the sections of the second band (beginning with 2.3), I argue that all these conceptualisations are interrelated in a matrix of mutually supporting — but not tightly systematised and static — values, arguments and attitudes. The theoretical groundwork established in Chapter 2 introduces the approach and values within which this thesis has been conducted. It justifies my attention to the practice, of diverse (non-orthodox) forms of anarchism and affirms a notion of pluralistic anarchism; of anarchism-as-practice; and the ethos and argumentative ‘spirit’ of anarchism. This chapter, therefore, justifies my placing of EDA within anarchism, and introduces the critical tools with which we ‘think about’ anarchism in this thesis. I endeavour in this chapter to move away from conventional or static mappings of ideology, and instead lay out a basis on which a fully dialogic and enacted anarchism of multiple sites and voices may be understood. Instead of practice being deformed to fit the theory, the practice can be shown to demonstrate and explore the meaning of the theory.

Chapter 3, Methodology, provides the first demonstration of my anarchist approach, as I consider how feminist, postmodern, critical realist and other politically-engaged perspectives may be used to develop research that challenges and is less saturated by statist, capitalist and faux-objective norms. I situate myself within my own research and I introduce the local Newcastle group, TAPP, as the context in which much of my activism and research was situated. I emphasise that I could not conduct research which is either ‘pure’ (free from negative impacts, free from negative power dynamics) or ‘transformatory’ of my subjects, but I do argue that my research has remained true to anarchist ethics. Considerations for a libertarian research methodology characterised by anarchist ethics include a sensitivity to the dangers of ‘representation’ and exploitation, and a commitment to genuine dialogue with actors who are not streamlined to fit hypotheses, but are recognised as rational and complex actors.

Chapter 4, Green Radicalism, considers the legitimacy of saying greens are anarchist by reviewing the relations between anarchist thought (and practice) and green thought (and practice). It also introduces the impact of anarchist analysis on practice by detailing the anarchist critique of most green

strategies, and then marking out the strategic thinking of anarchism in terms of ‘revolutionary’ and ‘direct’ action. Environmentalism may be understood and identified through its practice as well as through recognised ‘green texts’, and the thought and practice of anarchism and environmentalism are engaged in a process of dialogue, hybridisation and contestation: it is within this process that grounds are provided for eco-anarchism to exist Environmentalism and anarchism are broadly compatible, and each gains by the application of the insights and ethos of the other (although no final synthesis is possible — they exist in an ongoing process of dialogue). I consider what radicalism is inherent to ecological thinking, and assess the relationship of environmentalism to different traditions: specifically anarchism. In the latter part of the chapter, I then outline the eco-anarchist critiques of capitalism, the state, and all green strategies that fail to systematically oppose those factors. This is followed by a presentation of the anarchist approach to ‘true’ revolutionary action. Here I emphasis the place of freedom at the heart of all legitimate anarchist approaches to change: a point that will follow us through the ensuing chapters.

In Chapter 5, Activist Anarchism: the case of Earth First!, I provide a detailed assessment of an actual example of experiential, ecologically-motivated activism, one that defines itself on anarchist terms and holds its debates according to recognisably anarchist terms. I first consider the dynamics involved in the creation of anarchistic activists and activist organisations such as Earth First! The chief two factors here are the institutionalisation — the co-option, neutralisation, bureaucractisation and state-ification of environmental organisations — and the radicalisation (both alienation and empowerment) of activists engaged in extra-institutional struggle to defend the places they love. I also introduce DIY Culture, as the counter-cultural milieu out of which EF! emerged, and as die clearest example of an informal anarchist movement that was bound by deeds not words, and was therefore able to accommodate difference at its very heart. In the second band of sections I assess Earth First! as the most clearly eco- anarchist organisation in the UK. I characterise the activist anarchism of Earth First! as a compound of many varieties, none overbearing, and I demonstrate that the arguments of many anarchist currents have been practically re-expressed in the EF! network I chart Earth First!s ‘revolutionary’ qualities through a critical examination of notions of ‘success’; I note its strategic rationale and note how it demonstrated traditional dualisms of individualism vs community, red vs green and lifestyle changes vs social objectives, to be irrelevant to an anarchist practice. Finally, I look most fully at Earth First!’s organisation and identity, as expressed through an anarchist process of dialogue and dissensus at the 1999 Winter Moot. Here we may glimpse many traditional and divergent elements of anarchist ideology, and witness how they are accommodated to a contemporaiy ecological context.

Chapter 6, Conflictual Strategies of Action: Violence, GM Crops, and Peat, moves to questions of strategy, violence, and the tensions that arise between some of the divergent strategic frameworks that co-exist within an activist anarchist plurality. I begin by clarifying the definition of anarchist direct action, first by constrasting it to liberal or indirect forms, and second by drawing out some of its positive ethos from the context of anarcho-syndicalism. I then move to look at the issue of violence in direct action, beginning with the polarised and unhelpful ‘fluffy’-’spiky’ opposition that was held in EDA. I gain a more nuanced approach by assessing views of violence in the historical anarchist tradition as expressed, for example, through refutations of the of ‘propaganda of the deed’. Having distinguished anarchism from pacifism, I conduct a dialogue between anarchism and CD discourse, the dominant theoretical influence on the peace movement which has, in turn, had a positive influence on EDA. I then look at sabotage, viewing it as the marker point between liberal and radical environmentalisms, but itself surrounded by issues of violence and noncompatibility with certain other EDA strategies.

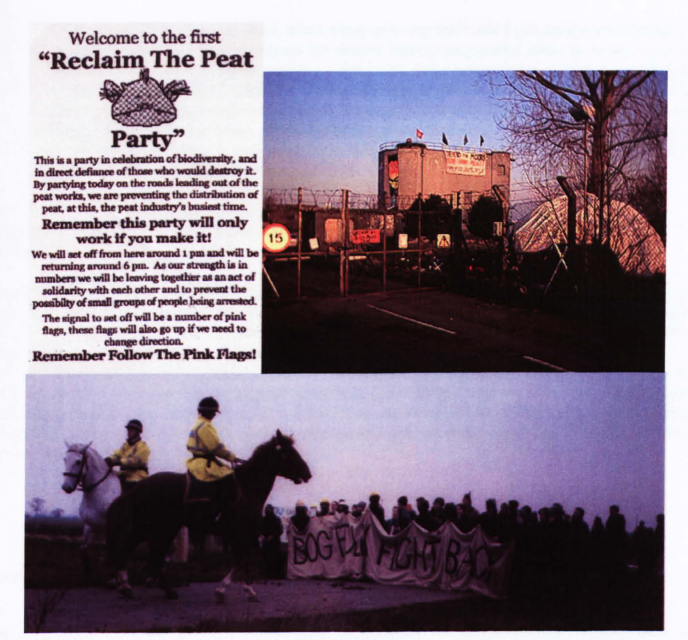

In the second half of the chapter I move to concrete examples of debates concerning strategy, elitism and violence within nineties EDA. First, with Anti-GM direct action, I consider the forms of anti-GM activism that hold most relevance to an anarchist strategy. Centrally, I present the covert-overt debate as a case of dialogue between ideological and strategic positions that, despite their marked opposition, are both able to exist within a broad field of anarchism, sharing and expressing anarchist values even as they contest each other. Secondly, with Peat and the ELF, I consider the place of sabotage in EDA, and evaluate it according to the terms of anarchist ethics and principles. I contrast two organisational forms of ecosabotage, characterising the ELF as ‘representative’ and founded upon a social division, and Peat Alert! as participatory, grounded and fully in keeping with my anarchist assessment of EDA.

Chapter 7, Reclaim the Streets and the Limits of Activist Anarchism, turns to the forms of nineties EDA most celebrated by anarchists, and then most criticised and commented upon by press, politicians, and EDA practitioners. Reclaim the Streets was the site of 1990s EDA that was most celebrated by anarchists, for holding the most promise of a truly confrontational, anti-authoritarian challenge in society. I establish the anarchist basis of the critical mass and street party tactics deployed by RTS in London and then spread around the world (using Newcastle as a provincial example). In addition to drawing out the anarchism contained in the practice, I also look at the anarchism contained in the diverse ideology promoted by RTS, including elaborations such as the revolutionary carnival, the TAZ and the Street Party of Street Parties. I argue that their development into a more abstract, static and repetitive practice of anticapitalism eroded many of the grounds of their success. This demonstrates the tension that still pertains between ideological anarchism and EDA practices, and between the ideals of anarchist organisation and the practicalities of ‘successful’ action. I conclude by utilising the example of Mayday 2000 as the much-heralded conjoining of traditional ideological anarchism and the looser activist anarchism of EDA. I focus mostly on the problems that were perceived to arise on this occasion, and I return to the strengths of earlier EDA to identify reasons what had been lost.

2. Anarchist Theory

2.1 Introduction

This chapter introduces the theory with which — and within which -1 will be working throughout the thesis. This involves (a) grounding the reader in the central tenets of anarchist discourse, (b) evaluating the idea of ‘anarchism’ itself and (c) introducing some of the critical tools of anarchism. The subject of this thesis is not just the counter-cultural activists engaged in environmental defence, but also the body of arguments, values and experience termed anarchism.

The first part of this chapter looks at the distinctive conceptualisations or key tenets held by anarchists, and explores some of the implications for our study of anarchism. 2.2.1, Against Authority, Against Definition, negotiates the initial problems faced when gaining a grasp of anarchism’s identity. I introduce the ‘sources’ of anarchism that I shall be drawing on in this thesis, and use the first principle of anarchism (anti-authority) to sound a note of caution concerning our ability to authoritatively define anarchism. The next four sections establish a further four key tenets and hallmarks of anarchism, namely 2.2.2 Freedom, 2.2.3, Rebellion, 2.2.4, Human Nature and 2.2.5, Power. I present a case for anarchism in which these tenets are interrelated, distinctive and, I argue, both coherent and accurate. The distinctive anarchist perspectives on these issues go a long way to revealing the essence of anarchism. Yet it is not my aim to fix these tenets, but rather to use them to aid the exploration of possibilities later in the thesis. Moving to the nature of anarchism, the next three sections, 2.3.1, Strength in Flexibility, 2.3.2, History and the Idea, and 2.3.3 Orthodoxy and Second Wave Anarchism, identify apparent inconsistencies and problems of a closer definition of what anarchism is. I argue for anarchism’s flexibility — its fundamental simplicity making it capable of great complexity when applied. I also argue for an anarchism that it is practical not purist, and I argue that it manages to be both diverse, yet coherent, and I insist that it should not be simplistically equated with any of its particular historical or doctrinal versions. By understanding these aspects of anarchist ideological ‘structure’, and examining how the construct of ‘anarchism’ relates to reality, we find ourselves more accurately situated within anarchism, and less likely to make mistakes of reductivism, over-literalism, confusing a part for the whole, and so on. Finally, I assess how anarchism is expressed through 2.3.4, Emotion, 2.3.5, Reason, and 2.3.6, Practice. These are the facets of anarchism that are manifested through EDA, and they are also the signs by which we might get to know anarchism.

By working within a broadly anarchist framework, this thesis might run the danger of uncritical self- referentiality. I do note criticisms of anarchism, but when these rest on foundations antithetical to anarchist values, I have generally found they are a case of talking past the ideology, rather than to it This means they can be dismissed by anarchists as either ‘reformist’ or ‘authoritarian’, a position I elaborate in the environmentalist context in Chapter 4. Much more severe and hard-hitting critiques have been launched from within the anarchist camp, however: between the many different camps- within-the-camp. An incessantly critical and questioning attitude is integral to anarchism. Thus anarcho-syndicalists condemn eco-anarchists, class-struggle anarchists critique anarcho-pacifists, individualist anarchists attack anarcho-communists and so on: anarchism is no placid philosophical scene but a cockpit of competing, impassioned and vigorous viewpoints, and it is tested daily on-the-ground. It is this lively and contested terrain that forms the substance of this thesis.

In studying the forms of anarchism deployed by today’s environmental activists, I shall also be noting which elements of ‘classical’ anarchism have been left behind, and which have re-emphasised. In so doing, I will be considering what constitutes the ‘core’ of anarchism — what cannot be left behind without losing the title. I will also be paying strict attention to the manner in which the ‘key tenets’ are adapted to their environment-of-use and how, in so doing, they become modified — sometimes almost completely estranged — from their nineteenth-century or early-twentieth-century meanings. The concept of ‘direct action’ constitutes the main object of study in this regard, but I shall also consider such conceptualisations as sabotage, revolution, organisation, solidarity and anticapitalism. This thesis presents an exploration of the nature of ideological continuity and coherence in the context of almost

wholesale change. This chapter provides a foundation for this process by exploring the central tenets and key aspects of the anarchist doctrine.

2.2 Key Tenets of Anarchism

2.2.1 Against Authority — Against Definition

“Beware of believing anarchism to be a dogma, a doctrine above question or debate, to be venerated by its adepts as is the Koran by devout Moslems, No! the absolute freedom which we demand constantly develops our thinking and raises it towards new horizons ... takes it out of the narrow framework of regulation and codification” (Emile Henry, written before his execution, quoted in Calendar Riots c2002: 8th November).

Defining anarchism is a difficult task: whatever definition I adopt will be given the lie by one or other variety of anarchist. Almost every attempt at definition begins with a disclaimer, such as the following from the first ‘Anarchist Encyclopaedia’: “There is not, and there cannot be, a libertarian Creed or Catechism. That which exists and constitutes what one might call the anarchist doctrine is a cluster of general principles, fundamental conceptions and practical applications” (Faure in Woodcock 1980: 62; cf Bonanno 1998:2). We must limit the ambitions of what is being attempted here. Even the most standard definition of ‘Anarchism’ is only the definition of one type of anarchism.

There are nevertheless certain statements that can be made about anarchism, as the Encyclopaedia goes on to do: the “many varieties of anarchist... all have a common characteristic that separates them from the rest of humankind. This uniting point is the negation of the principle of Authority in social organisations and the hatred of all constraints that originate in institutions founded on this principle” (in Woodcock 1980:62; cf Sylvan 1993:216; Walter 2002: 27; Notes from Nowhere 2003:27; Makhno et al. 1989: General Section). Anti-authoritarianism will be our first point of contact with anarchism.

Anarchy is opposed to authority, as demonstrated by the etymology of the word “‘an-archy’: ‘without government’: the state of a people without any constituted authority” (Malatesta in Woodcock 1980: 62; cf Morland 2004:24). Others may translate the Greek slightly differently, as ‘against authority’, ‘without rule’ or ‘absence of domination’, but the gist at least is clear. Woodcock notes that Faure’s statement in the Encylopaedia (‘Whoever denies authority and fights against it is an anarchist’)

“marks out the area in which anarchism exists...[but] by no means all who deny authority and fight against it can reasonably be called anarchists”. Thus he states that both ‘unthinking revolt’ and ‘philosophical or religious rejection of earthly power’ cannot be called anarchism. In this thesis we will encounter many claims of what does and does not make an anarchist, and it will be clear that I myself am also engaged in various attempts at constructing a border around the term. All such attempts at definition are by their nature problematic and liable to critique, although the family resemblances of the various branches of anarchism are, at least in my view, reasonably clear-cut.

Within the revolutionary socialist tradition, anarchism distinguished itself by declaring “the viewpoint that the war against capitalism must be at the same time a war against all institutions of political power”, such as parliament (Rocker C1938:17; cf Kropotkin 2001:49). This division was most clearly displayed in history by the “famous, definitive and prognostic” split in 1872 between Marx and Bakunin in the International (Ruins 2003:2; 1871 Sonvillier Anarchist Congress, quoted in Woodcock 1986:229), when the anarchists rejected the proto-state being formed within the international revolutionary organisation. In Bakunin’s terms, “The smallest and most inoffensive State is still criminal in its dreams” (Bakunin quoted in Camus 1951:126; cf Bakunin 1980: 143), and anarchists consistently argue that an instrument of oppression cannot be used for the liberation of the oppressed. For this reason, anarchists rejected revolutionary strategies aimed at ‘capturing the state’ and insisted instead that “Freedom can only be created by freedom, that is, by a universal popular rebellion and the free organisation of the working masses from below upwards” (Bakunin 1981:42–3; cf Goldman 1980:154).

I do not wish to examine traditional anarchist history in any depth, however. In line with the assessment of Woodcock that I shall consider in section 2.3.2,1 feel that anarchy is best understood as an ideal, which provokes and inspires many different manifestations according to different historical circumstances. None of these is ‘pure’ anarchy — a correct model for all descendants to copy — but an attempt to realise unbounded freedom within a specific context The historical situation, the technology and culture, the needs and desires of the people of the time and the challenges they face all play a part in the form of anarchism which they develop (Welsh & Purkis 2003:5). As Purkis & Bowen put it, “Anarchy has many masks which are all important and this diversity cannot be united under one banner” (1997:1). In exploring specific contemporary examples of anarchism in this thesis, and offering insights that affect our understanding of anarchism as a whole, my intention is to enlarge and diversify our understanding of anarchism, and not to attempt an everlasting or definitive analysis. There are, however, five recurring tenets of anarchism that may be used to help identify it. We have here introduced the first, anti-authority, and I will now turn to the second, freedom.

2.2.2 Freedom

“to look for my happiness in the happiness of others, for my own worth in the worth of all those around me, to be free in the freedom of others — that is my whole faith, the aspiration of my whole life” (Bakunin 1990b: xv-xvi; cf Kropotkin 1987:222).

The one substantive principle we have thus far is that anarchists are opposed to authority. The converse of this is that they are in favour of a type of freedom in which there is no authority. John Henry Mackay sums up what this ideal signifies in a couplet:

“I am an Anarchist! Where I will

Not rule, and also ruled I will not be!” (quoted in Goldman 1969:47).

Thus anarchist freedom is not the same as individual license, which can be oppressive and exploitative (Ritter 1980: 24). The libertine or ‘negative’ liberty of individualism may reach its apotheosis in both antisocial egotism, and in neo-liberal, unregulated capitalism. Both of these are antithetical to anarchism (Chan 2004: 119; TCA 7(1) 2005: 31; Zerzan 1991: 5).[3] For anarchism to make any sense, one’s individual liberty must be matched by a social freedom, in which no-one is denied their own liberty by, for example, lack of resources and opportunities: “freedom to become what one is”, in Read’s terms (1949:161; cf Berlin 1967:141; MacCallum 1972). Carter extends this anarchist conceptualisation of freedom into the green sphere, where he argues “the freedom to act so as to compromise ecological integrity is, in the long run, freedom-inhibiting” (1999:302; cf Wieck 1973:95). We shall see this argument deployed particularly in the case of cars (section 7.4), but also underlying much green activism.

Representing the viewpoint of social anarchism, Bakunin argues that our individual freedom is given us by society, and that “this liberty... far from finding itself checked by the freedom of others, is, on the contrary confirmed by it” (quoted in Bookchin 1995a: 74; cf ACF c 1991:42; Woodcock 1992: 82[4]).

Such is the hope of social anarchists, summed up by Malatesta when he states that their ideal is “complete liberty with complete solidarity” (in Woodcock 1980: 64; cf Malatesta 1974:27; Walter 2002:29; Ritter 1980:3; Hill 1973:35). Such is the noblest ideal of anarchism, and it emerges in all

kinds of ways throughout anarchist theory and practice. In 4.3.4 we will underline the place of freedom within the anarchist method of revolution.

I am only touching here upon an issue that is of the highest importance to some anarchist individualists, who part company with social anarchists on precisely these grounds of individual liberty (Miller 1984: 14; cf Carroll 1974:47; Caudwell 1977:72). To my own project, however, this issue has proved largely irrelevant, which perhaps demonstrates how far within the realm of social anarchism (not individualism) the eco-activists of my study are. The reason for this could be that the very impulse to and practice of activism is an embodiment of individual social responsibility. Zinn sums this up with the idea that, “To the extent that we feel free, we feel responsible” (1997:632).

Brown explains how the anarchist understanding of freedom moves one into an opposition to state power and domination:

“Anarchists understand that freedom is grounded in the refusal of the individual to exercise power over others coupled with the opposition of the individual to restrictions by any external authority. Thus, anarclu’sts challenge any form of organisation or relationship which fosters the exercise of power and domination. For instance, anarchists oppose the state because the act of governing depends upon the exercise of power, whether it be of monarchs over their subjects or, as in the case of a democracy, of the majority over the minority” (1996:150; cf Brown 1989: 8–9).

We will examine the anarchist view of power in 2.2.5, but let us for now recognise that the anarchist hostility to government lies not in a grasping desire for personal power, but is based on an ethical desire for social freedom. If there are self-proclaimed anarchists who act solely for their own gain, then they have little relation to anarchism as a political theory.

2.2.3 Rebellion

“As man seeks justice in equality, so society seeks order in anarchy” (Proudhon in Woodcock 1980:10).

The key belief held by anarchists is that government is at best useless, and more commonly the source of society’s ills and suffering. The converse of this belief is that people without government are able to create a just society that caters to everyone’s needs (Bookchin 1989a: 174; Barclay 1986). Thus Harper states that “Anarchy is pretty simple when you get down to it — people are at their very best when they are living free of authority, co-operating and deciding things among themselves rather than being ordered around” (1987: vii).

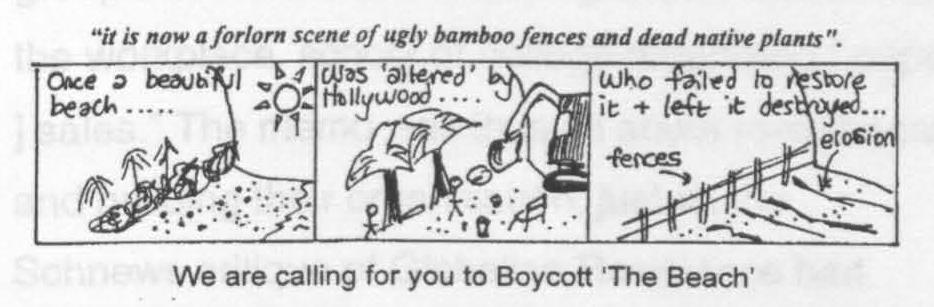

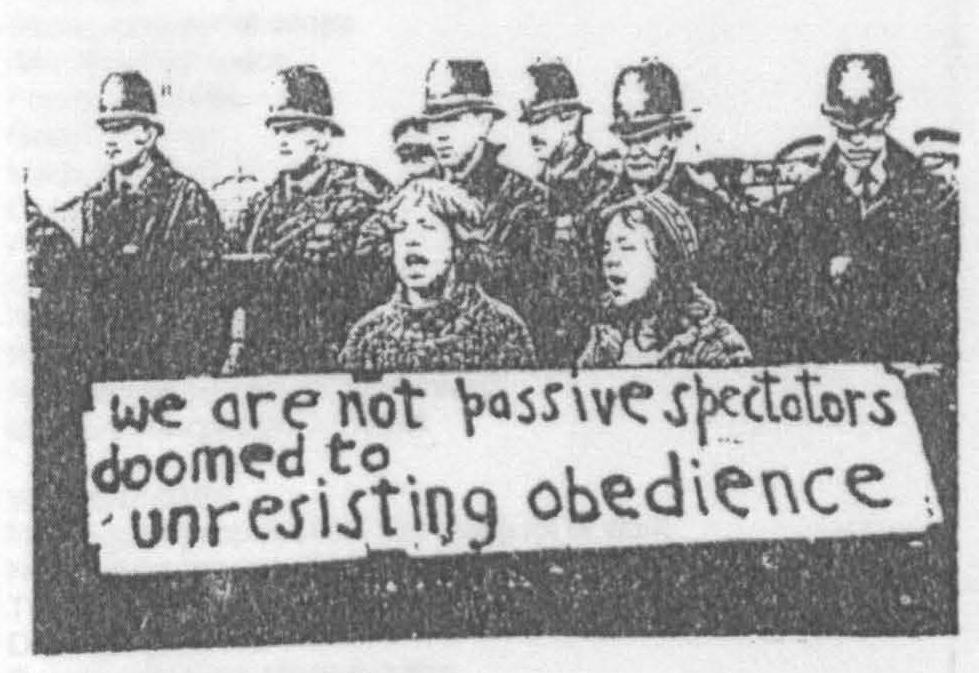

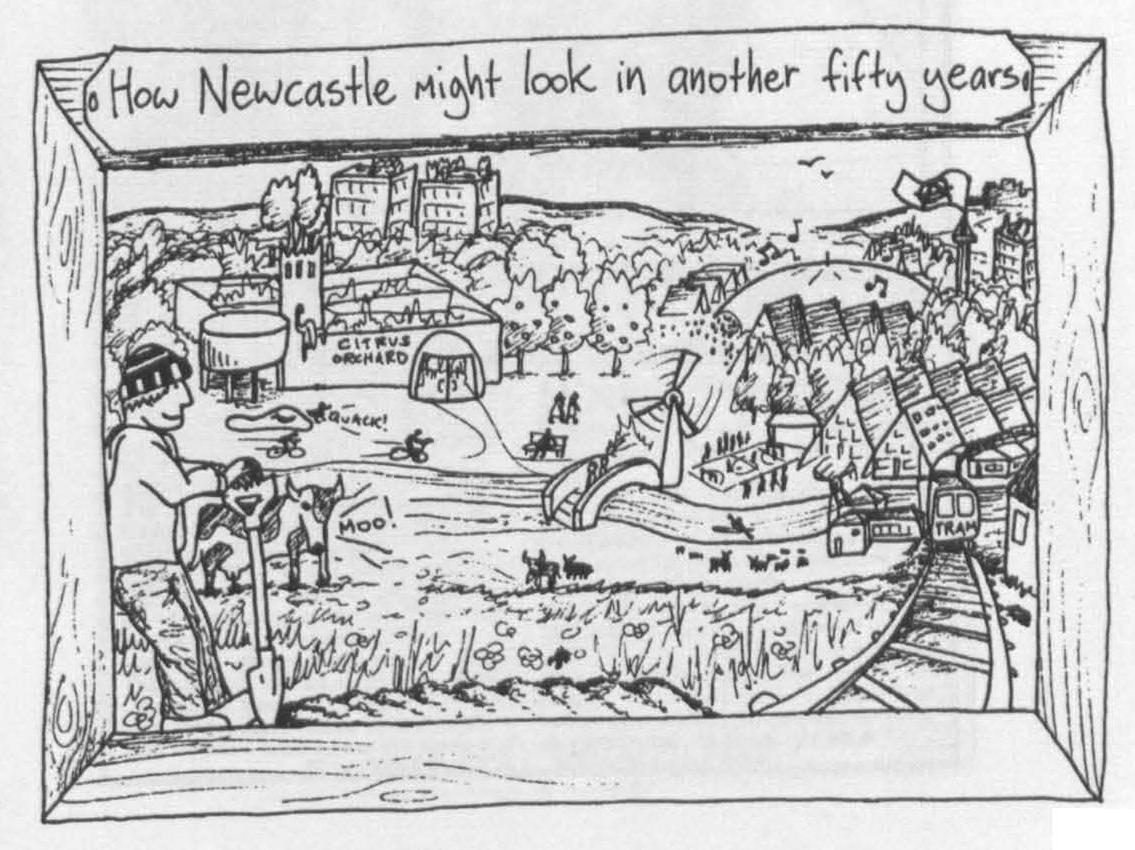

This is where the symbol of anarchy, the circled A illustrated in Figure 2.1, acquires one of its interpretations: ‘Anarchy is Order’[5]. This is a counter-intuitive statement when anarchy is so universally associated with chaos and rebellion. But within a society warped by authority and law, anarchists champion spontaneous expressions of revolt and creativity: “Anarchists are forced to become what politicians describe them as: ‘agents of disorder’“ (Meltzer 2000; cf Jasper 1999: 359). In a world so upside-down that following normal, everyday life means conniving in oppression and exploitation, the expression of a ‘natural’ or ethical order may well take the form of protest or resistance. As Wilde phrased it: “Disobedience, in the eyes of anyone who has read history, is man’s original virtue. It is through disobedience that progress has been made, through disobedience and through rebellion” (in Woodcock 1980: 72; cf Chumbawamba in Schnews 1999; Heller 1999 [C]: 108–109). A demonstration that this theme is still current is demonstrated in Figure 2.2.

Here we are provided with a justification for focussing on direct action and protest, because this is the place where, according to anarchist theory, the right life of society takes place. In Chapters 4 and 7, however, we will see that protest — and even direct action — is not a sufficient ingredient for anarchism. Values from elsewhere in anarchism may therefore be brought to bear on the practice of activism, and are used to critique it. I clarify this point in my characterisation of ‘anarchism through practice’ in 2.3.6.

While the actual proclivities of anarchists may often be for rebellion and spontaneous creativity, the ultimate goal of a free society is defined by order and peace. With this end in view, Kropotkin in the 1910 Encyclopaedia Britannica gives perhaps the most authoritative definition of anarchism[6]:

“a principle or theory of life and conduct under which society is conceived without government — harmony in such a society being obtained, not by submission to law, or by obedience to any authority, but by free agreements concluded between the various groups, territorial and professional, freely constituted for the sake of production and consumption, as also for the satisfaction of the infinite variety of needs and aspirations of a civilised being” (1910: 914).

We may note that this is an organisational definition: perspectives on organisation occupy a central place within anarchist political theory, and we will encounter the issue of both theoretical and practical organisation in every chapter of this thesis. What ; wish to make clear here is that, notwithstanding the many peaceful and constructive attempts to build anarchist structures and cultures in the here and now, anarchism more than any other ideology is one of contestation, opposition and active resistance. As an ideological support for the kind of protests and actions covered in this thesis, from sit-down protests to inner-city street-fighting, anarchism is unsurpassed.

2.2.4 Human Nature

Anarchists are commonly accused of having an over-optimistic view of human nature (Adams 1993: 172–3; Heywood 1994:28). This is because they have argued that, left to its own devices, humanity would naturally choose a non-exploitative society based on natural solidarity: “This does not mean that anarchists think that all human beings are naturally good, or identical, or perfectible, or any romantic nonsense of that kind. It means that anarchists think that almost all human beings are sociable, and similar, and capable of living their own lives and helping each other” (Walter 2002:28; cf Woodcock 1980:18; Heller [C] 1999:85–88[7]).

Carter states that the supposedly over-optimistic account in anarchism is “an over-simplification” and “a perennial half-truth that deserves to be critically examined” (1971:11–16; cf Miller 1984:76–7). Instead, “Anarchists are proprietors of a double-barrelled conception of human nature”, in which “Egoism is balanced by sociability” (Morland 1997a: 12–13). Humans are neither intrinsically good nor bad, but they have the potential for both. As Proudhon writes:

“Authority and liberty are as old as the human race; they are bom with us, and live on in each of us. Let us note but one thing, which few readers would notice otherwise: these principles form a couple, so to speak, whose two terms, though indissolubly linked together, are nevertheless irreducible one to the other, and remain, despite all our efforts, perpetually at odds” (quoted in Purkis & Bowen 1997: 6; cf Marshall 1989:45; Walter 2002:53).

Even Kropotkin (generally considered the most optimistic of the classical anarchists) balances his identification of innate solidarity with an equally natural tendency to ‘self-assertion’ that can lend itself to authoritarianism (2001:110; Miller 1984:73).