New York Post Left

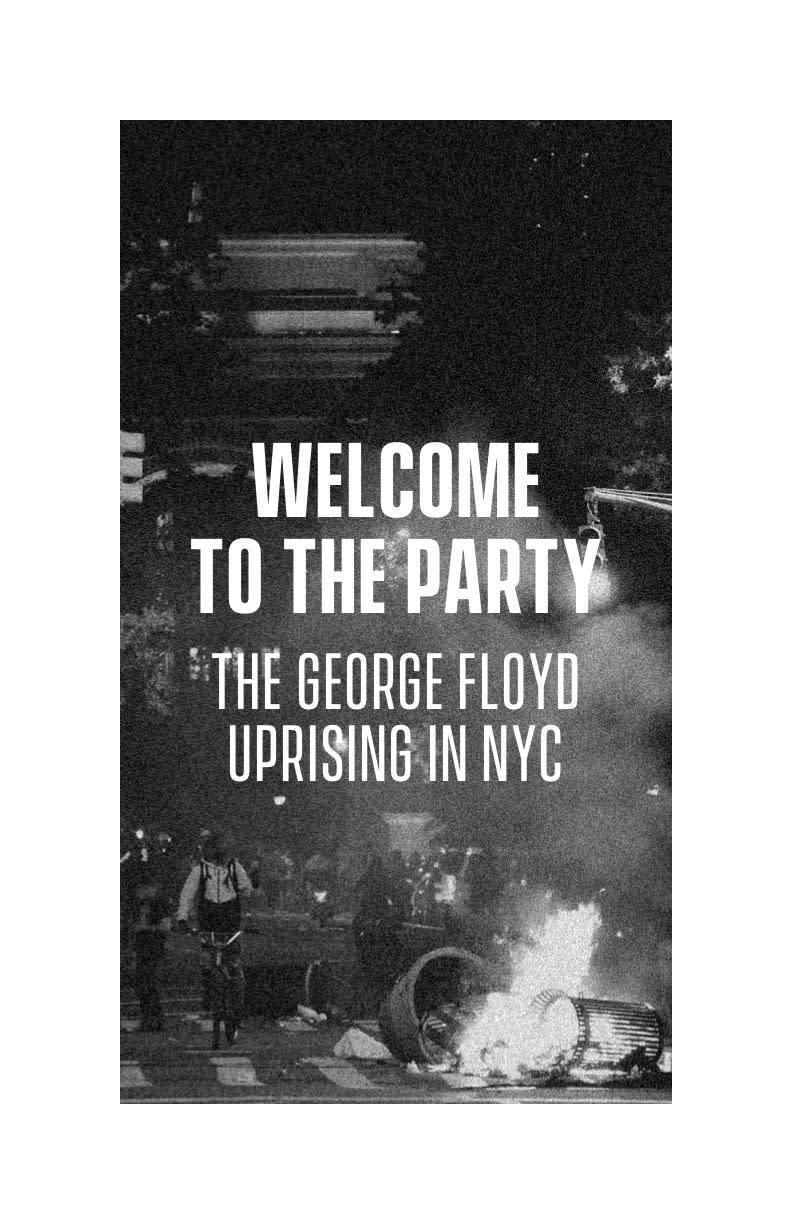

Welcome to the Party

The George Floyd Uprising in NYC

Since early march, New York has been in qranatine Paralysis. Over 20 thousand have died in New York City alone, many working-class brown and black people, and hundreds of thousands more lost their livelihoods.This shocking new reality left many wondering if the pandemic would be the final nail in the coffin for a city where for decades, the economy has so brutally triumphed over people. But then, in an instant, we all marched outdoors together, inspired by images of the first days of revolt in Minneapolis, its fearless crowds looting a Target and setting fire to the 3rd Precinct. Some of us were essential workers, forced to risk exposure to the virus to make ends meet. Some of us chose to face those risks for the sake of mutual aid projects. Others had been isolated inside for months. All knew breaking “shelter in place” orders to gather in a crowd potentially spelled disaster for a city already the worst hit by the epidemic. Time will tell if our foresight was lacking, but with infections declining, it seemed worth the risk.

The first solidarity demonstration, held Thursday night in Union Square, was contained with the same policing techniques that had been effective in tamping down the momentum of the disruptive Black Lives Matter marches in 2015. A demonstration the next night was called for the Barclays Center in downtown Brooklyn. Police surrounded the square, pepper-spraying the crowd and making seemingly arbitrary arrests. Barricades were built on a nearby avenue and a police car was set on fire, while others marched to reconvene at a nearby Fort Green Park.

From there a young multiracial group of protesters attempted to storm the 88th Precinct, followed by hours of street fighting in which the crowd hurled bottles and bricks and damaged every police vehicle in sight, eventually setting a van on fire – acts of resistance virtually unheard of in NYC.The police fought back with baton and pepper-spray charges, ultimately repelling the crowd from the doors of the precinct, but not before their desperate message rang out through the city: they were losing control.

The next day mass marches in every borough generated images of their violent desperation. In broad daylight, and in front of media, police responded to the ongoing vandalism of their vehicles by pepper-spraying, penning, and shoving protesters. In at least one incident, they drove a car into dozens to break a road blockade. These tactics were designed to disperse, divide, or at least paralyze the march, but people fought back and kept marching over the Manhattan bridge to lower Manhattan. As night fell, the crowd built barricades and clashed with the police as it marched on SOHO, the downtown neighborhood lined with luxury boutique stores, looting street-wear brands and burning police vehicles along the way. As was the case in much of the country that night, the spell of police control had been broken. No amount of force seemed capable of stopping the joyous crowds smashing their way into luxury shops and distributing the clothes, shoes, phones, jewelry, liquor, and skateboards amongst the march and to passers by.

On Sunday night, the police attempted to block a large march in Brooklyn from crossing the Manhattan Bridge at dusk, but fearing the optics of a confrontation against an orderly crowd, they let them through. Once in Manhattan, similar tactics as the night before were repeated, only this time the city had taken care to clear the streets of trash cans and other potential projectiles. A segment of the crowd stayed to stand-off against lines of riot cops in Chinatown, while others marched freely through Soho to Union Square for hours, taking and doing what they pleased while defending each other and loudly chanting the slogans: No Justice no Peace, Fuck the Police, Fuck 12, George Floyd, and NYPD Suck My Dick.

Outside the Strand Bookstore, flaming barricades and volleys of bricks and bottles held back a small detachment of riot cops while hundreds danced in the street and shared looted bottles of whiskey. With the police spread thin by stand-offs, hundreds of mostly black youth, organized in crews and dressed in all black began quietly making their way downtown. Over the course of that night, the luxury stores of Soho were systematically looted.The cycle of rioting, dispersing, and reconvening until early in the morning. A key question that emerged in the course of these nights was what to make of the looting from an autonomous anti-capitalist perspective. Often it followed patterns familiar to us from the descriptions of Minneapolis or even the Watts riots in 1965: everything taken was freely shared among those present in a festive atmosphere, the looters were seemingly intent on calling into question the value of a given commodity, and the world that upholds that value. In the moment, they seemed as interested in the novelty of the what they were doing as much as they were in getting something for themselves. These looters emerged from a hybrid group of “peaceful protesters” and rioters who would kneel with police one minute and run down an avenue smashing windows and starting trash fires the next.

It became clear on Sunday and Monday that the police were not seriously confronting the looters, having been repelled by “airmail” from disorderly groups and even shot-at or run-over by vehicles leaving and coming into Manhattan to loot. Often organized in crews, these hundreds or thousands spanned from Soho to the Upper East Side, with groups emerging in the Bronx and Queens as well, to methodically clean out shops, carrying away as much as they possibly could, either for themselves and their friends or resale. Images spreading in the news and on social media of organized looters and the scale of destruction they left in their wake seemed to lend itself to the notion that there were “professional looters” opportunistically using the protests as a cover.

On the ground, this distinction felt much less clear cut: some of the methodical looting was social, done in fairly dense crowds, and maintained an air of festival. Throughout the weekend one could see scenes of people tossing out boxes of iPhones to anyone passing by, distributing twenties from a smashed register, leaving jewelry on the sidewalk, or crews fighting one another for turf, electronics, or designer clothes. While it is tempting to divide the looters into “political” vs. “opportunist,” without intimate knowledge of the origins and dynamics of these crews we are left unable to make strong conclusions. Despite the clear communal images, by Tuesday the “protester” vs. “looter” distinction had really taken hold in the media. Just as as the narrative of “community” vs “outside agitators” had succeeded in creating conspiratorial hysteria throughout the nationwide rebellion, de Blasio and NYPD forwarded a narrative of orderly vs. disorderly, peaceful vs. riotious, good vs. bad, with a distinction as clear as night and day: the curfew. The police would be hands-off in daylight, the bulk of their forces two blocks away from the marches. At night they would come out swinging and making arbitrary arrests, with the Manhattan DA promising to keep suspected rioters in prison indefinitely. Few were willing to publicly support the “bad protesters” or attack the professional activists who asserted themselves from nowhere as “movement leaders” to justify violence against anyone willing to continue the hard-fought momentum of the weekend’s street fights. With an 8pm curfew and doubling of police forces on Tuesday night, the peaceful protesters and would-be rioters were forced to collide back into one another. Now unable to take territory on their own, well-masked crews of black youth could be seen dotting the sides of marches in Manhattan, waiting for their moment to continue looting. As the night went on, they would break off from the larger marches along with their accomplices for a smaller-scale roving riot that often re-targeted the same shops as previous nights. But each night they found themselves more isolated.

An announced militant action Thursday in the South Bronx, framed as the next in a sequence of “FTP” protests against MTA police, was kettled and almost entirely arrested the minute curfew began. The NYPD was no longer allowing marches to cross the bridges, and snatching bikes from protesters created an aura of fear. Although still massive, popular, and willing to break curfew, the weight of the movement tilted heavily towards the “good protesters,” bathed in the sunlight of the mayor’s praise. By Friday, one week since the first clashes, the “bad protesters” largely stopped coming out.

The hundreds of black proletarian youth and their accomplices who swarmed through lower Manhattan or Midtown each night provided the struggle with its dynamic spark to the soundtrack of Pop Smoke. They had no interest in formulating demands aside from “suck my dick.” Rather than being stuck in clashes with the police, their goal became to evade them through the shopping districts that have become most alienated to life in NYC. Decades of leftist street slogans like “diversity of tactics,” “be water,” “an injury to one is an injury to all” came organically. The constant return to downtown Manhattan showed a certain strategic deliberateness. Few were willing to defend the luxury stores in that black hole of alienation, and only the politicians fretted about keeping up appearances that Manhattan is a luxury gated-community for an increasingly terrified bourgeois bohomenian elite. Despite speculation that the NYPD have some sort of blackmail gun to de Blasio’s back, this is the real reason he tolerates their brutality – they are the army defending the world of the rich. But now that world is dying; from factors both objective and subjective.

By Saturday, June 6, it was clear the riots would not return. Nonetheless, New York has maintained daily mass marches and rallies distributed across the five boroughs in almost every neighborhood, with almost every kind of activity (meditation, bike marches, street parties). The sound of fireworks could be heard throughout the city every single night. In many working-class neighborhoods, a different pyrotechnic display can be seen every couple blocks. A recent New York Times investigation confirmed what anyone could have guessed: the city’s proletarians are celebrating the riots and having survived the epidemic, and self-consciously exhibiting their defiance.

While energy has remained high, it also seems to lack a direction. The movement’s sharpest edges have been dulled by police violence and “progressive” ideological capture by the neoliberal city government, and so far unable to develop new tactics to stay dynamic, the movement has found itself in something of an impasse. Whether this holding pattern will be disrupted by unexpected turbulence, or whether a gentle landing awaits us is yet to be seen. Are we to keep attempting to subjectively push it forever, or must we wait for the next atrocity? Between these options it seems possible for revolutionaries to find a new rhythm and way of relating to the still-vibrant mass movement, even if it no longer seems to hold an immediate insurrectionary potential. At the same time, revolutionaries need to be durably organized to sustain their capacity through the valley to prepare for the next peak – which we will know from the smoke rising from a precinct.

It is unlikely we will have very long to wait, even if the four Minneapolis police officers are not acquitted.The situation in America, and New York especially, is particularly combustible. With the massive rates of unemployment brought on by the pandemic, and tens of thousands actively on rent strike, there are already millions who feel they have little left to lose. What will happen this summer if there isn’t a new stimulus package and people begin to lose their unemployment boost?

It is no coincidence that this uprising took place at the tail-end of mandated social distancing as an epochal economic crisis takes shape, and the only solution of the neoliberal order is to discipline restless “essential” workers by pauperizing an underclass into a desperate reserve-army of labor. The refusal of politicians to cancel rent, end mass incarceration, or stop prosecuting crimes of poverty are a clear sign of this strategy of reifying the hierarchies that turn the working-class against itself: citizens against immigrants, white workers against black workers, and black workers against the black underclass. At the heart of the movement for black lives, lurking beneath its most lauded petty bourgeois reformist figureheads, is a profound recognition of the superficial nature of these antagonisms.

Like the initial revolts that spread from Ferguson, this rebellion was at a scale and intensity unseen in the US since the sixties and is evidence that we are in a cycle of escalating struggles, each picking up where the last one left off. The occupation of university campuses in 2009 inspired Occupy in 2011. In 2014 the killings of Trayvon Martin, Mike Brown, and Eric Garner inspired weeks of marches and blockades across the country. But aside from the antifascist mobilizations of 2017 and brief occupations outside ICE facilities, the Trump era had been relatively quiet until late 2019. But, when struggles against authoritarian neoliberalism spread throughout the globe, from Sudan to Chile and from Haiti to Hong Kong, such rebellions inspired New York’s FTP marches against the rising cost, decling quality, and racialized policing of the subways. These marches helped cohere a layer of militants oriented towards, and now experienced in, direct action. But even as those FTP marches got progressively more intense, they never broke out of the activist demographic. This latest wave was the first to not only involve a much wider cross section of the city, but bring to the fore a faction that both understands that black lives will never matter so long as we live under a society defined by white supremacy and capitalism, and was willing to joyfully and fearlessly subvert it night after night.

For now we may be entering a phase of stabilization, in which liberals will redouble their commitment to outlandish conspiracy theories and empty reforms, it is important to support the bravery of the insurgents. In order to do so, certain types of rhetoric should be overcome:

-

The dichotomy of “good” and “bad” protesters. Although they are imagined opposites, one provided the bark of mass movement, while the other offered the bite of direct action. They are strongest when they exist together in the streets. If either side is to be critiqued, it is those elements that seek to tear the unity apart for the sake of their careers

-

Conspiratorial thinking. The idea of singular groups of bad actors, weather they be a global satanic pedophile elite, outside agitators, police infiltrators, or “bad apples” of any variety chokes the expansion of solidarity needed to for the movement to continue building power. The sides are most clear in the moments of frontal confrontation: rebels on one side, police and property on the other.

-

Abolition as the end goal. The abolition of the bourgeois institutions of police, prisons, and borders are certainly revolutionary goals, but they can only be achieved by a social revolution that abolishes class society, the economy, and the bourgeois State. The implications of looting can be defended as a coherent gesture of this core mission: the expropriation of the wealth of society and the world alienated from us. The “bad protesters” hate the police and say so, but only burn police cars or destroy precincts at their convenience. The logic of attacking police and looting shops is not some illusion that the quantity of cops or commodities will be diminished, but that the struggle against them is moving towards a situation where they are irrelevant.

-

Leadership. By acknowledging that black proletarian youth acted as a vanguard in this movement, we do not mean to say one should seek any young black leader and follow them, nor that the black and brown proletariat are the only class fraction with revolutionary potential. In each wave of struggle, different layers of the class serve this vanguard function, pushing the moment to its limits through bravery, recognition of their own interests, and self-organizing. Historically, though, black proletarians tend to provide the detonation for much wider social unrest. Rebels not from this background will be stronger comrades in future struggles, whatever form they take, by developing their own confidence, goals, and organizations. As much as possible, however, revolutionaries should try to make and keep contact with those George Floyd insurgents who trashed Manhattan for three nights straight while resisting a cross-class alliance with professional activists.