No Border Zine Netherlands

Information and Inspiration for Solidarity Networks to Fight the Netherlands’ Bureaucrashit & Build Autonomous Support Against the Dutch Border System

October 2024

The need for an anti-racist solidarity

How things work, and how they impact life

What does it mean to “have a Dublin”?

The process of a Dublin deportation

Responses to the transfer decision

New Asylum and Migration Pact (April 2024)

New Dutch government migration plans (September 2024)

The RVT (Rest and Preparation Period)

The general asylum procedure (Track 4)

The “second/detailed interview”

LGBTQIA+ applicants: homonationalism at its finest

Living without the right documents

Isn’t squatting dangerous, risky???

Isn’t squatting intense/stressful/dirty?

Safety and privacy for squatters*

COA withdrawing parts of salaries

Illegalized work and tips to navigate it

Physical and mental healthcare

Huisarts / General Practitioner

How can emergency care look like for people without documents?

Paying for prescribed medication

Existing solidarity organization

Useful Medical Care organizations

INTRODUCTION

Why This Zine?

This zine is being created collaboratively from July to October 2024 by people with and without the “right documents”, who are trying to live in the (so-called) Netherlands. We want to document the experience of immigrants going through the asylum procedure, to create momentum for more organizing as accomplices* and smash the border system together.

The bureaucratic process to be “legalized” is made deliberately complex by the Dutch State and the EU to discourage people from applying and to fuck them over — we believe that by informing ourselves, we can fight back. Reading the stories of comrades who are going through this hell is educational and necessary if we want to stand by their side throughout the struggle; however, this zine obviously does not account for the whole range of existing experiences. The initial ambition was to cover all the types of situations relating to documentation in a border State (through work, through family reunification... and also what happens when living illegalized). However, this zine ends up mainly focusing on the asylum procedure because there is so much bureaucrashit to cover around this. Still, some of what is in here is more broadly applicable to people without the officially-designated “right” documents — see it as a start to encourage more and more information to be shared and networks to be built in solidarity with all illegalized people!

We tried to make it as accurate and up-to-date as possible, also integrating the new rules of the European Pact on Migration and Asylum of Spring 2024, and the Dutch government plans to restrict asylum and migration presented in September 2024. But be aware that things change fast and information might have evolved by the time this zine is in your hands, especially with the fascist PVV government. The website RefugeeHelp or the Amsterdam City Rights App are good resources for up-to-date information in many languages!

You will find a glossary of key terms (marked with an asterisk*) and a list of sources we used.

Some questions you can expect to get answers on:

-

What are the bureaucratic steps that deliberately make it hard for people with the so-called “wrong” documents to build themselves a home and community in the Netherlands?

-

Why do I keep hearing about Dublin? Should I go visit? (spoiler: no)

-

How can we build solidarity networks that reject racist and white savior practices?

-

What stands behind the sketchy acronyms Eurodac, IND, COA...?

-

Where is there need and space for autonomous support?

The Words We Use

There are many different words to refer to the situation of the comrades at stake here. They all come with different implicit meaning, from totally dehumanizing to politically ambiguous, used daily by the media and liberals to conservative politicians.

Some like to reclaim the word “migrant”, or its derivative “immigrant” which affirms the aim to settle. Others use “undocumented people” (although people sometimes manage to keep their documents, just not the right ones that the country recognizes), “illegalized”, “unauthorized”, or “exiled people”... We decided to use different ones interchangeably in this zine, because there is no perfect term. It is a political choice however to avoid using the official terms such as “asylum seeker”, “citizen” to address or refer to someone, because they all reinforce nation-state frameworks. If you think some words really don’t belong in our anarchist lexicon, please let us know!

The way we put words together is political. We have rephrased the zine many times, taking in comments and revisions. The main goal has been to avoid creating a form of “othering” (us versus them) in the writing that replicates symbolic borders, carrying an assumption bias on who is writer/reader. But also, to use “plain language”, meaning clear and concise, getting rid of inaccessible academic and pretentious words that reinforce hierarchies.

Combining both was sometimes hard, notably because of the role of pronouns — they simplify reading, but they carry a lot of meaning. On the one hand, this zine is written by a diverse range of people, so when you read “we/us”, it is meant as an all-encompassing term for anyone who shares the same affinity to dismantle borders. On the other hand, this zine is written for people who want to be accomplices* and allies* to the ones going through the border system. Overall, we tried to use less “you” or “they”, which can create a binary between the “supporter” and the “supported”. The main intended audience of this zine remains people without the direct lived experience of migration or exile.

For example the section on anti-racism is especially relevant for white and documented people. And in fact it was mainly written by white documented people. While we acknowledge this means it might lack the first-hand experience of the racist border regime that we are denouncing in the first place, we also think it’s important that people in positions of privilege talk to each other and share their experiences of learning to be allies/accomplices. Yet, if you are yourself “illegalized”, a lot of information in here is relevant to have first-hand, for yourself or to share around.

This zine is a collective writing process, as non-hierarchical as possible (which is hard knowing all the hierarchies coming with knowledge, language and writing skills). If you have any kind of information to add, suggestions, critiques, please send to noborderzinenl@proton.me — we hope to release updated versions forever and ever, join us!

Glossary (Alphabetic order)

Accomplice : a person who helps another one commit a crime. “When we fight back or forward, together, becoming complicit in a struggle towards liberation, we are accomplices. Abolishing allyship can occur through the criminalization of support and solidarity” (from the zine Accomplices not Allies by Indigenous Action).

Ally: mainstream term for someone who helps and supports other people who are part of a group that is treated badly or unfairly, although they are not themselves a member of this group. Can be “white young middle class allies”, paid activists, non-profits, or “downwardly-mobile anarchists or students” (from the zine Accomplices not Allies by Indigenous Action).

AZC (Asylum Reception Center): housing facility for Asylum Seekers in specific procedure, refugees waiting for other housing options

BIPOC: Black, Indigenous and People of Color. Can be synonym to non-white, and racialized people.

Border externalisation: EU countries evade their asylum rights duties by avoiding that applicants ever reach their national land. They shift the migration control to countries on the route to Europe, for example by funding the so-called Libyan Coast Guards.

To be “called-out/in”: calling attention to problematic, harmful, and oppressive behaviors in order to change it. Calling out happens more publicly, sometimes as a spectacle (in a community or on social media for example), while calling in is done privately when people have capacity for it.

COA (Central Agency for the Reception of Asylum Seekers): the organisation responsible for the reception and supervision of asylum seekers. The COA is supposed to provide asylum seekers with housing and basic services from the moment they apply for asylum until they have a residence permit and have found accommodation in a municipality.

Dublin: the Regulation that determines which country is responsible for someone’s asylum claim, i.e. the first one they reach in the European Union — see dedicated part.

DT&V (Repatriation and Departure Service): professional repatriation organisation responsible for implementing the Netherlands’ repatriation policy aka deportation patrol.

IND (Immigration and Naturalisation Service): responsible for implementing the admission policy in the Netherlands. This implies that the IND invariably assesses all applications of immigrants who want to stay in the Netherlands or who want to become Dutch citizens. The IND transfers files of foreign nationals to the DT&V if they are not granted a residence permit in the Netherlands or if they are no longer entitled to stay in the Netherlands.

KSU (KraakSpreekUur): Squatting Assistant Hour, during which squatters can answer all questions and help in trying to open a squat. Check radfar.squat.net to find one in your area!

Mutual Aid: a form of resistance to capitalist competition and invidualization, through one-on-one or collective support systems = emotional or material voluntary exchanges

Pushback: a variety of criminal measures aimed at forcing refugees and migrants (including minors, accompanied or on their own) out of their territory while preventing access to legal and procedural frameworks. In doing so, States circumvent laws concerning international protection, detention, deportation and the use of force.

Squatting: occupation of empty buildings that landlords otherwise use to make money out of people’s right to housing — see dedicated part.

Third-country national: the official EU term for a person who is not a citizen of an EU Member State or Associated State).

Tokenism: the practice of making only a symbolic effort to include members of minority groups in your struggle (for example, a collective that only has one black member might tokenize them to prove they are doing the anti-racist work).

White Savior Complex: a colonialist idea that assumes that BIPOC need white people to save them, that without white intervention; instruction, and guidance, racialized folks will be left helpless, and that without whiteness, BIPOC, who are seen and treated as inferior to people with white privilege, will not survive (Layla F Saad).

White Fragility: a state in which even a minimum amount of racial stress becomes intolerable, triggering a range of defensive moves = when a white person can’t handle accountability to a problematic behaviour (Robin di Angelo).

Brick by brick, wall by wall

Fortress Europe Has to Fall

We write this zine from an anarchist anti-border perspective. We believe that the border system, in its physical and immaterial forms, is inherently wrong, evil and dehumanizing — everyone should have freedom of movement, no matter whether they own the right piece of paper or not. The violence of the border materializes in many different ways, not only through the physical ones such as a barbed wire wall. All legal and bureaucratic systems in place in The Netherlands can be just as violent and traumatic as the armed pushbacks* ocurring across Europe. As you will understand through our legal overview, the bureaucratic process is extremely long and complicated, with the explicit aim to discourage people from settling in Europe.

European legal frameworks are promoted using key words such as solidarity and logos showing people held up by hands, in what could be considered a caring way. However, the solidarity at stake there is between the various nation states, not between the people, and the caring hand quickly becomes a snatching claw for people deemed “illegal”. This is not solidarity with asylum seekers but solidarity in the fight against their presence. It feeds into a rhetoric of alienation, well known in the mainstream, depicting migrants as violent or as burdens for European societies.

In response to this anti-migration propaganda, we must reclaim what solidarity with people on the move really means!

The need for an anti-racist solidarity

If you are reading this zine, it hopefully means you are motivated to create or join solidarity networks with comrades who are disproportionately impacted by the border system. This is great, but we want you to remember that it is essential to always be aware, critical and keep each other in check with the invasive authority and hierarchies that can come with this “supporting” position. Both the reasons why and the ways in which you engage in these relationships have to be questioned to avoid directly reproducing racism and colonialism.

This section is mainly dedicated to white people with the “right” documents. But many reflections on “allyship*” also apply if you have are in a beneficial class, language, social capital position, or another privilege compared to people on the move you come in contact with.

Confronting your whiteness

If you are a white person who wants to offer your support, it is critical to confront your own whiteness and the way you reproduce it, as well as then power position that comes with it. You must be aware of the authority dynamics which exist through the simple fact of you being white, meaning owning white privilege*, in order to change them. First, get out of the color-blind “I am not racist” mindset/ ideology. If you assert that you don’t make any differences in how you treat your comrades based on their race (understood as a historical and social construct, not a biological reality which it is obviously not!), country of origin, situation in the legal system, etc. then a first step is to recognize that you unconsciously do. Only by becoming conscious of the fact that your passivity maintains the white supremacist status quo, will you be able to move forward with anti-racism. If you don’t see all discriminations and inequalities, it is only because you benefit from them.

One piece of advice is to accept to constantly question your own intentions and your behaviors. It is a long process to deconstruct your internalized racism, and you are never really done with it (you will remain white and the State will remain racist — until we burn it too). Sometimes you really want to do the right thing, which can be a bit paralyzing and make you want to stay passive instead of accepting to be called out or called in* for something you did wrong. But that’s (white fragility*, and) not how we will get anywhere! It’s ok to make mistakes, if you are able to account for them and change. That doesn’t mean that solidarity with racialized people on the move should be a playground for your anti-racist education though; be aware that your words and actions can indeed do harm. Although the process is intensive and never-ending, it is also rewarding, and engaging in it will allow you to find power through feeling enabled to live and connect with people in a different way. You will be able to explore together what it means to build friendships and comradeship bridging those differences, may they be racial, cultural, linguistic... This comes with the struggle against the objectification of the people you meet, aiming to establish horizontal human relationships that respect the different subjectivities.

Some terms you could research online (or in Me and White Supremacy, a book we recommend by Layla F. Saad) to engage with your whiteness: White Fragility*/Policing/Silence/Superiority/Exceptionalism/Saviorism*/Centering/Apathy, Color Blindness, Anti-Blackness, Cultural Appropriation, Optical Allyship, Tokenism*, Called out/in*.

Burn the borders in your head

It is also necessary to question your internalized beliefs about the naturalness or inevitableness of borders. Although you were born in a State system relying on borders to police economy via people, goods and services circulation, and have lived your life accordingly, borders are white men’s creation and serve a hideous purpose: discriminate and make people feel inferior to the natives.

Concerning the “right” papers issue, you have to realize the privilege of being born with “European citizenship” if that applies to you. Being able to travel freely within the EU, having access to reduced costs in European educational institutions, and the ability to work legally (without being subjected to extensive bureaucratic procedures), to name only a few. The experience of time and space as EU paper holders is immensely different to one of people not having access to it. If you moved yourself within the EU, consider, for example, why you could be referred to as an “expat,” (if you are white and/or middle-upper class), while your friends are “migrants” or “refugees” (because they come from the Global South for example).

Mutual aid*, not charity

It is important to root ourselves in our local communities. Learning the faces, stories and needs of the people around us will help build resilient networks of support. This is true for all people, even nationals of the neighborhoods you want your movement to be rooted in. By creating interfaces for people to meet and greet each other, share food, thoughts, emotions etc, we can erect bridges and strategic alliances.

White Saviorism* is the belief that people with white privilege, who see themselves as superior in capability and intelligence, have an obligation to “save” racialized people from their supposed inferiority and helplessness. The “White Savior Industrial Complex” (Teju Cole) describes white people going abroad to Africa, Asia or Latin America as volunteers and missionaries in “rescuing” development missions. But white saviorism applies just as much locally through support people who have migrated to the Netherlands. From having the internalized racist imperialist idea that people’s home countries are less than Europe, to deciding how they should live their life here, white saviorism shows up in white people “with good intentions” who yet perpetuate white supremacy.

Usually, it is linked to performative, fake allyship, or the “ally industrial complex”, in which “allies” use their support of marginalized people to make themselves feel and look better, or even build an activist career. To avoid doing so, reflect on the relationship of dependency to the people you support, how you talk about your actions around you (does it make you feel “cool”?), which tasks do you concretely engage in (do you want to feel seen?), or the role of guilt and shame in your motivations... then you can think of being an accomplice* instead of an ally*! (read more in: Accomplices not Allies: Abolishing the Ally Industrial Complex).

We should share information and resources as much as possible to ensure that our friends risking harassment, detention and ultimately deportation are aware of their evolving condition. But it is most important to recenter the discussion around their needs rather than what we believe their needs are. If we want people to be free, let us dismantle the borders we hold in our minds. Even if “undocumented” under the laws of these countries, people have agency and can use it, stop believing you know better and ask instead HOW you can help!

So lend an ear, lend a hand, be humble and ready for action!

Some extra resources on anti-racism and allyship (if you can’t access them yourself, email us):

-

Me and White Supremacy by Layla F. Saad (workbook)

-

White Innocence by Gloria Wekker, specific to the Dutch Context (book)

-

Accomplices not Allies: Abolishing the Ally Industrial Complex on indigenousaction.org (zine)

-

The NGO sector: the trojan horse of capitalism by Crn Blok on theanarchistlibrary.org (zine)

-

White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo (book)

How things work, and how they impact life

This part of the zine explain how the asylum process should work in the Netherlands. There are already resources online available for undocumented people to help them navigate state bureaucracy (RefugeeHelp by Vluchtelingenwerk, Amsterdam City Rights App, w2eu.info, Migreat, Here to support, Fairwork.nu...). During the writing we noticed that the government websites are really not trustworthy (how surprising!): they explain briefly how things ought to go, but they are not accurate on the reality of it, especially the timeframes. These websites are more reliable.

We will combine legal information with testimonies from comrades who have moved, or are still moving, through this bureaucratic hell. However, the information might be outdated when this zine gets in your hands. As you’ve probably heard, the fascist government in the Netherlands and the EU are hardening all migration legislations to very worrying levels. So most of what you read here, which is already horrific, is probably worse by now. We invite you to check these online resources for updated information, and we’ll do our best to publish an updated version soon.

There are also many many other procedures to get “legalized” in the Netherlands. Unfortunately, we will not cover them as thoroughly in this zine, for the sake of space. But if you have interested in knowing more, email us and we will try to provide you some informations :)

Seeking Asylum

Who Can Seek Asylum?

Arriving in a European Country from a country they fled, one can seek asylum. This is based on the Geneva Refugee Convention of 1951: on the principle of “non-refoulement” which asserts that refugees should not be returned to a country where they face serious threats to their life or freedom, a person can flee “for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion” (UNHCR). As soon as a person has declared an intent to “claim asylum” (verbally or in writing), they are supposedly entitled to protection from that State, and thusly, should not be returned, deported, or pushed back.

Each Member State must refer to the EU guidelines when organizing the asylum procedure. However, over the years, illegal practices at the border, or in the streets, have been endangering this basic principle, as well as their own legal interpretations of the Geneva conventions stipulations. Pushbacks* along the route, border externalisation*, racial profiling, deplorable living conditions in detention centres, denial of access to legal support and translation, etc: both at the level of the EU and the Dutch nation, the “rights of asylum seekers”, supposedly part of Europe’s core values, are challenged daily.

In the Netherlands, the IND* (Immigration and Naturalisation Service, Immigratie en Naturalisatie Dienst) should make an initial decision within 6 months of the application, however, the IND has extended the official decision period by 9 months, to a total of 15 months (this goes for for applications between September 2022 and Janurary 2025, and we expect it to last longer). In reality, the whole procedure can take years with all the extensions and appeals. If the response is positive, the IND grants an Asylum Residence Permit in the Netherlands for 5 years that can be renewed but also withdrawn for various reasons. With the most recent government plans as of october 2024, this renewal is partiularly at risk!

The Netherlands has its own list of “safe countries of origin” and “asylum seekers from these countries are almost never eligible for protection” according to the Dutch government. The list contains countries where (according to the Dutch government), the following practices do not generally occur:

-

Persecution on the grounds of, for instance, race or religion;

-

Torture;

-

Inhumane treatment.

Ghana, Brazil, India, Morocco, Mongolia, Senegal and Tunisia are some of the countries on this list (check the government website for full list). However, some specific groups are exempted from the list, such as LGBTQI+ persons. In general, applicants from the so-called safe countries of origins are only given one chance to convince the IND that the country labelled as safe is unsafe for them. Instead of two interviews (the registration interview and the detailed one), one is only entitled to one interview. If the IND is convinced, it puts one in the general asylum procedure (AA) which grants a second (detailed) interview.

Dublin

What does it mean to “have a Dublin”?

Today, most people in the asylum process will tell you about their “Dublin” — maybe you’ve asked yourself what the hype is about Ireland’s capital city. When you hear “I have a Dublin in Italy”, or “I have to hide 9 months because of my Dublin”, it is referring to the Dublin III Regulation. Since 2013, it determines which EU member state is responsible for processing somebody’s asylum application: it should be the first “safe” country that someone arrived to in Europe. This responsibility lasts 18 months (details of why are explained below). Often, it goes to the first European country that an asylum seeker reaches, but not the country where they had hoped to settle. When travelling through the Mediterranean route, people often are “dublined” in Italy or Greece; or in Bulgaria, for example, when moving through the Balkans. Some have Dublin in the country were they managed to get a visa for, others where they first were caught as “illegal” and forced to identify themselves on their route.

For holders of a visa in the Schengen (EU) area who want to seek asylum in another European country, there is a 185 days period (around 6 months) after the expiry of the visa before applying to avoid being dublined. For instance, if a Spanish visa holder comes to the Netherlands in December, and their Spanish visa expires on February 1st, they must wait until the end of August before going to register. With the new Migration Pact, it will be extended to 18 months.

The Dublin procedure

Through checking documents (e.g. passport for visa) and the Eurodac database* (see next section), the police (AVIM) and/or Koninklijke Marechaussee (KMar) can find out if someone has been registered by another Dublin country before the Netherlands. Then, a long procedure starts:

-

The IND will hold a “Dublin interview” to ask questions about the migration route (not at all about the reasons to ask for asylum). If they decide that another country is responsible for the asylum request, the IND sends an intention letter of transfer. Currently, there are 10 weeks of waiting before the interview with the IND for the Dublin procedure.

-

The assigned lawyer can first respond in a letter to IND against this decision. If it is still negative, which is often the case, they can also officially appeal the decision.

-

IND sends the other European country a “takeover or take back request”. There are different deadlines for different situations:

-

If someone is found in the Eurodac database, the Netherlands must contact the Dublin country within 2 months after the Eurodac database has been consulted.

-

If someone does not appear in the Eurodac database, but there are supposedly other reasons for a Dublin transfer, then the application must be sent within 2 months after the asylum application has been made.

The time limit that the Dublin country has to respond depends on whether the person had already requested asylum in that Dublin country or not:

-

If the person had not requested asylum, the Dublin country has 2 months to respond

-

If the person had requested asylum then the Dublin country has 1 month to respond if there is no proof via Eurodac, and 2 weeks if there is proof via Eurodac.

If the Dublin country doesn’t respond within the maximum period, they apply “no answer is a positive answer” : no response is considered an acceptance of the request. This can lead to someone being transferred/deported to a European country which will then try to deport them to their home country without considering their case.

If the Dublin country declines the take-back request, The Netherlands must start processing the asylum application.

The process of a Dublin deportation

The IND asks the DT&V* (Repatriation and Departure Service, Dienst Terugkeer en Vertrek) to organize a “return trip”, aka an intra-European deportation.

DT&V has 6 months from the date of acceptance of the Dublin claim, to proceed to this deportation, after which the transfer order expires. In practice, they take the person in their room at the camp, or wait for them when they come to the weekly sign-in at the camp (see “IND procedure” section).

This back-and-forth can take months, leaving people in a never-ending limbo. Also, the Dublin system can force people to go back to countries where their asylum claim has already been denied. Just because their fingerprints are found in Eurodac, or they find a document linking them to that country, The Netherlands makes the political choice to get rid of them.

Responses to the transfer decision

1.

If the Dublin country agrees to the “transfer”, the person can appeal. But these procedures are very difficult to win. The grounds that can be used to appeal a Dublin deportation are:

-

Familial: legal presence in the Netherlands of family members with residence permits, who are seeking asylum or who are protected (for example, if your Dublin country is Spain, but you managed to reach Germany and you are a minor with family members who already live in Germany, the appeal might be processed successfully)

-

Medical: health problems, pregnancy

-

Legal: having experienced ill treatment while in the Dublin country, and evidence of well-founded fears that there are systemic flaws in the Dublin country’s asylum and reception policy

The latter is super frustrating and evil, because of course the reception and asylum policies have systemic flaws, but the starting point is always the “interstate trust principle” (EU nation-states have each others back). It’s hard to convince the court or the higher court that the situation is so bad that authorities agree that there are systemic flaws in the view of a system that is steeped in excluding, discriminating and humiliating people. Also, with Dublin “transfer” deportations (unlike deportations to somebody’s origin country, which can happen if their asylum claim is rejected in the Netherlands), the court is not obliged to have a hearing, which means that many people will never be given the chance to defend themselves.

If the court puts a stop to Dublin deportation to a particular country, the Secretary of State will always appeal to have it overturned there. Very occasionally, the higher court rules that deportation to a certain other EU country is no longer allowed. Currently this applies to Greece, Hungary, Italy.

If you start an appeal against your Dublin transfer, you can only legally await the decision in the Netherlands if you also start another procedure, called preliminary injunction (vovo, verzoek om een voorlopige voorziening). Some lawyers don’t bother mentioning this to their clients. If the preliminary injunction is granted, the 6 months transfer period starts running again, from the date of the decision on the appeal, so the person can stay in the NL in the meantime. But, in the case of a dismissed preliminary injunction, the appeal has not been granted a suspensive effect, so the original transfer period applies.

In order to reach the Netherlands and apply for asylum, I applied for a Hungarian student visa, they called it a Residence permit (D visa) application, where you get a D-type visa on your passport, then you are supposed to go to Hungary and there change the visa to a student residence permit. To make sure I reach the Netherlands as the first safe country, I took a KLM flight out of Istanbul, miraculously the Turkish authorities believed my story that I was going to Hungary to study. During the transit in Schipol Airport in Amsterdam and at the end of the tube connecting the plane to the terminal stood two Royal Marechaussee officers whom I approached and declared that I want to apply for asylum. I spent my first night in the airport transit lounge because I arrived late at night and the IND office was closed. The next morning I was approached by two IND officers, who took me to the office and told me that because Hungary issued me a visa, it meant that I automatically will go through the Dublin procedure. I argued that I had not stepped a foot in Hungary, but even then their reply was “your asylum application will be handled in Budapest”. After that I was taken to a holding facility next to the airport, and only after two days and during an interview with the Vluchtelingenwerk, I was told that after further consideration and due to the fact that the IND thinks I will not be treated fairly by Hungarian authorities (given their past human rights violations against refugee) my Dublin status will be overlooked and I my asylum request will be lodged in the Netherlands. Those two days felt like hell, and the first time I was told I will be sent Hungary where my asylum will be processed, I was in such a shock and all I wanted is to cry because what future will I have in a country that openly hates refugees (except Ukrainians it seems), and worse is racist against Muslims. — Yousef, a citizen of Yemen.

2.

Another alternative is to “wait out” the Dublin period. In IND terms, someone is considered “on the run”, if they refuse their deportation. In practice, it means hiding from the authorities who come to the camp to deport you. This adds 12 months — and soon with the new law 3 years — to the appeal process. Meaning that, for 3 years, one has to live this illegalized life.

If someone is caught during this waiting period, they will probably be placed in a detention center to keep them under surveillance while their deportation is planned by the DT&V. They can also place people in detention as soon as the transfer order is given, if they suspect that the applicant intends not to submit to the transfer decision.

The hardest part about this is that Dublined people are not even in procedure, but just stuck in what feels like an open-air prison, their presence considered illegal in the Netherlands until their waiting time is over. They are left to their own devices, regardless of whether the reasons they came to Europe fit into the Geneva Convention or not. People with Dublin and/or from “safe countries” don’t have access to shelter or housing because they do not have “prospects” for their procedure. Some may get exceptions based on their vulnerability, but this process is painfully slow and bureaucratic. Activists and human rights organizations have been critical of the Dublin Regulation since its inception. The New Asylum and Migration Pact of April 2024 will solidify these time frames, proving that Dublin remains a pillar of the contemporary European Fortress border system.

There are, however, many “creative alternatives” to hide at the right moment without the IND considering you as “being in hiding”. This is where the solidarity networks are very necessary, proving and using the cracks of the border system.

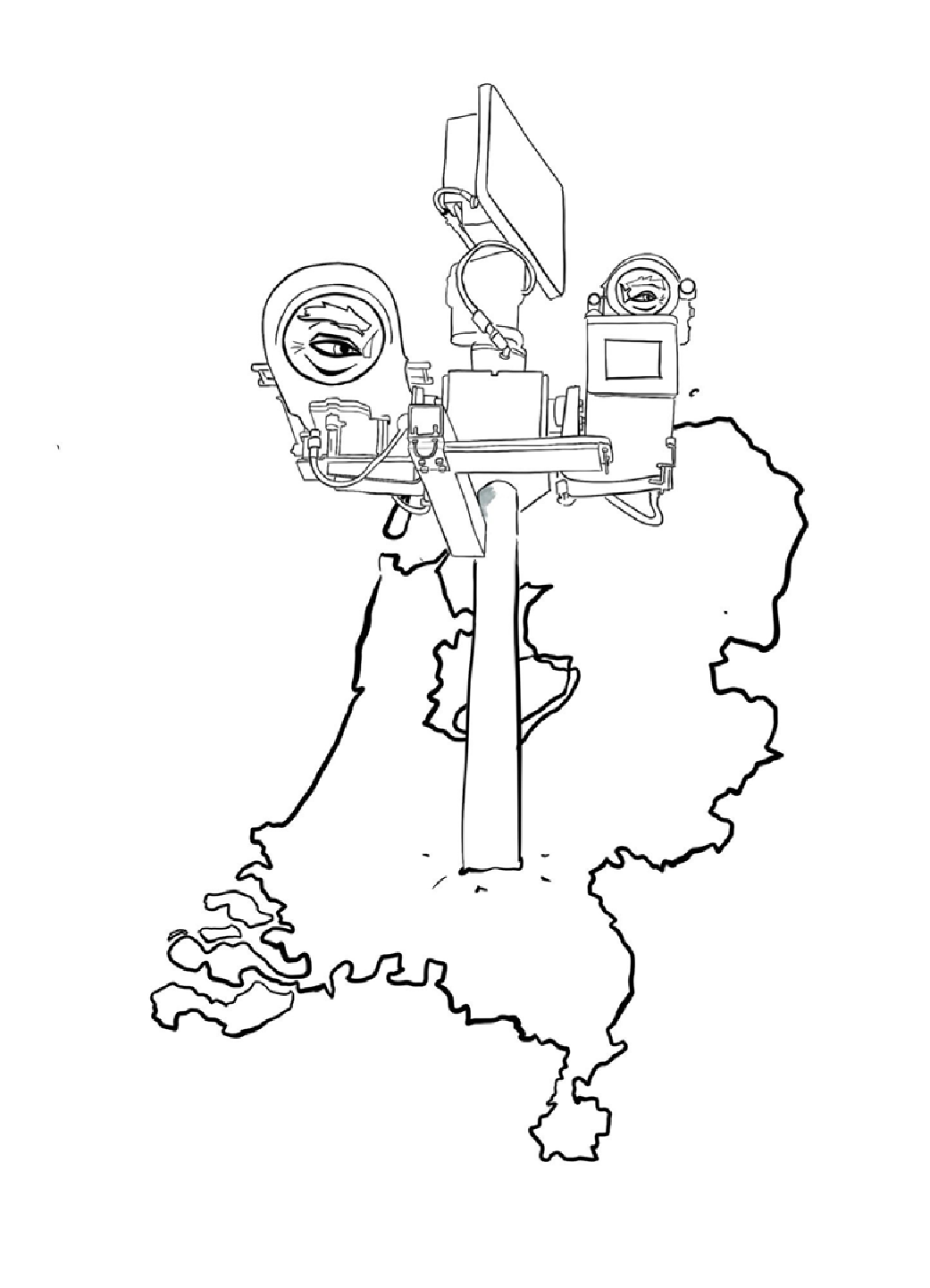

Eurodac

Eurodac* is a massive database aimed at storing personal data of people on the move in a “common” way which all EU member states can access, since 2003 — to enforce Dublin. Previously, it only applied to people over 14, but it got extended in April 2024 to children as young as 6 years old. Eurodac stores information through fingerprint data, and has started using a variety of biometric data, including facial recognition.

Eurodac is thus a major part of the surveillance system that Europe seeks to generalize, disrespecting common rights to privacy through forced personal data collection. The registration of fingerprints can be a traumatic moment, as the police resorts to physical violence to force people’s submission. Some people on the move turn to extreme methods to avoid this violation, such as cutting or burning their fingertips.

This Europe-wide monitoring looks like a testrun on “illegal humans” — who have less means to rebel — for a surveillance system intended for the general population. It is also contributing to “crimmigration”, the merging of immigration and crime control that we have observed in the past years, as the private data starts to be openly shared with law enforcement. Just like fences spread like the plague on national borders, digital biometric data travels as freely as a white EU expat.

Some of the private organisations that operate Eurodac, like Thales, are also involved in border fortification and weapons export (see Inspiration section ;)).

New Asylum and Migration Pact (April 2024)

In April 2024, after many years of secretive negotiations by a selected few in ad hoc commissions, a new Migration and Asylum Pact was voted in at EU level, a combo of 5 super technical regulations totaling thousands of pages only specialists can understand, directly applicable to national orders (so no need for Member states parliaments to sanction it!). Each member state must have drawn up a National Implementation Plan by December 12, 2024. Some of them went ahead and pushed forward some legislations, like Belgium who voted a law in May 2024 organizing for the deployment of Frontex agents in international harbors, railway stations and airports throughout the country...

The “Pact” introduces a variety of fucked up policies:

-

“Accelerated” border procedures will take place at borders without or with very limited legal safeguards like translators and legal aid, supposedly to speed up processing. The procedure will now depend on statistics of previous acceptance rates, without consideration for subjective danger. For example, if you are a trans person subject to discrimination in Morocco, of which the acceptance rate for asylum in the Netherlands in 2023 was 5%, the specificity of your situation won’t being taken into account.

-

It also targets people who enter “irregularly”, which is super fucked up considering there are no regular routes to claim asylum in the EU for most people from most countries.

-

Mandatory “screening” and more detention will be used, on external borders and even offshore, which means people will be detained without any judicial or legal process. Furthermore, the Pact creates so-called “hotspots” on EU territory that are fictitiously deemed not to be on EU soil, as to bring down safeguards standards for the unfortunate people trapped there. Detention conditions are horrible, and without legal protections there’s no guarantee of how long somebody can be detained for, although the Pact refers to a 7-day-to-6-months turnaroud.

-

The “safe third country” principle will be extended to make externalisation* deals easier, when EU countries pay substantial amounts of money to non-EU countries to control their borders and stop movements way before people even reach EU territory. Because some deals are phrased as “development grants”, like the EU Trust Fund for Africa, which make access to funds conditional on migration controls, there are EU arms, troops, walls, and pushbacks as far as Sub-Saharan Africa. Expanding this principle makes it easier to deport people, and makes it easier to pay countries like Libya, Morocco, Tunisia, and Turkey (the main recipients) to detain people before they reach the EU.

-

Restricting “secondary movement” will also become legal, meaning States can restrict movement of people on the move to specific areas — separating families, communities, support systems, and often trapping people in isolated places without work or education opportunities.

-

The “crisis and force majeure” regulation introduced now means that States can exempt themselves from human rights in cases of “crisis” (such as what they call “instrumentalisation”). But these terms are deliberately vague, and although the EU has been disregarding the rights of people on the move for years, now this pact makes it legal when they decide it’s a “crisis”.

-

Cherry-on-the-rotten-cake: the Solidarity Mechanism. States will now be able to use others’ capabilities to help them handling their own flow of people on the move, by making it an option to subcontract some pieces of the chain, for example where one member state does not have enough prison cells to detain “asylum seekers”.

All in all, this freaking Pact (with the devil?) brings EU territory from the status of fortress to the near-apartheid level :

-

It is a way to legalize and institutionalize all criminal practices and laws Member States have implemented so far;

-

It will enhance collaboration between Member States to get rid faster and more efficiently of those people governments do not consider as unwanted human beings.

-

It is draining other human rights protection conventions from most of their substance, just like the UN convention on the law of the Sea, which makes it unconditionally mandatory for any vessel at sea to de-route to help boats in distress.

-

It is providing for a massive increase in Frontex funding (the EU Agency originally created to avoid the mass drama of boat people dying at sea while trying to reach EU soil, but now commissioned to keep migrants at bay): Frontex is now the top-funded agency of the EU constellation as well as the only one to benefit from a 10.000-agent workforce, weapons, detection and mass-surveillance equipment of both people on the move and their supporters.

-

It is spreading the net of mass-surveillance of both through the interconnexion of EURODAC* and national migrants and crime databases.

-

It is making life even harder (if possible at all) for those unwanted to live in the EU

-

...And we still can’t grasp the extent of its ramifications in our struggle, for as of yet the texts have not been released and the bits and pieces that leaked to the public are so technical-worded only experts can see beyond its reassuring and neutral wording...

New Dutch government migration plans (September 2024)

But that’s not all to come! In September 2024, the new Dutch PVV government specified their plans to bring in drastic new anti-immigration measures, set to be some of the strictest in the European Union. “We are taking measures to make the Netherlands as unattractive as possible for asylum seekers,” said Marjolein Faber, the minister of Asylum and Immigration. Yet, in 2023, the Netherlands only received 3% of all EU new asylum applications (about 40 000 people).

The government will even ask for an opt-out, that is an exemption on EU asylum and migration policies, meaning they aim to be even stricter than what we listed in the previous section. As often with fascists, they announce big measures that are not even constitutional, meaning not all of it will be applied (the EU already said an opt-out is probably not possible). However, we can’t know for now, and some of it will definitely pass and have horrible consequences for immigrants. Especially because they want to declare an asylum crisis, through the emergency law (like they would do in case of war), that means they can take measures without any democratic checks (no need to be approved first by a majority of the Senate and the House of Representatives). This is all veryyyyy worrying.

Some of the announced measures:

-

There will be a moratorium, meaning a suspension on new asylum applications (WTF?? This is probably even against the Geneva Convention)

-

The rule that asylum seekers automatically receive a permanent residence permit after 5 years is abolished. Asylum seekers who have been in the Netherlands for 5 years or more may still be required to return to their country of origin when it is deemed safe — again, WTF??

-

Reception facilities will be downgraded in number and quality of facilities, and have stricter rules (although they already had budget cuts and are already prison-like, ending the Dutch Distribution Act will have worse consequences).

-

Individuals without the right to would be forcibly deported (already the case, but making it worse)

-

Recognised refugees may only bring family members to the country if they have held their residence status for at least 2 years, have adequate housing, and a “stable and sufficient income”. There will also be a limitation on family reunification for adult children.

Conclusion: we need an anti-fascist front to organise, and fast!

The IND procedure

As just said, the IND procedure will be affected by laws coming in the next few months. But we will explain a little how it goes as of September 2024. This section will be quite long and detailed, but the information is very important to know what the reality of requesting asylum is like.

Registration

When they arrive in the Netherlands by land, asylum seekers have to register with the IND at the application center in Ter Apel (3 hours by train from Amsterdam). This is the main processing centre in the Netherlands, centralizing all requests. However, people who have to apply for asylum at the Airport, often because they are not allowed to enter the Netherlands, are sent to a closed reception centre Schiphol Judicial Complex (JCS); it is not officially a prison, but it looks like one.

Applicants are detained there throughout their asylum “Border Procedure”.

From experience [at JCS], you are allowed to go out in the yard for one hour only per day. You are not allowed to leave your room/cell from 9pm until 8am. Doors locked and the guards make sure you are in the room. Finally you can only roam in your jail wing. No electronics allowed. and if you want a shaving blade you have to give you reception ID, take the blade, shave, return it and then take back your reception ID.

1. At Ter Apel, applicants will have to be identified and registered first or second day they arrive: sharing basic information, depending on what documents one brings and whether one is from a so-called “safe country”.

2. The following day, the fingerprints are taken by the IND and police, that will decide what type of procedure one can go into. Since June 2021, when the Aliens Decree on the Regular Procedure (“Track 4”) entered into force, the immigration officer asks the applicant for reasons of their departure. The answer to this question can significantly impact the applicant’s asylum procedure, even though it takes place without a lawyer and without the necessity of informing the applicant of the consequences of their statement.

3. Then, one has to wait for the “registration/application interview” also called the “first interview”. Applicants were waiting in reception centres around the country, without knowing when they would be invited for the IND registration interview (the “first interview”). Widespread reporting throughout Dutch newspapers and news publications show that conditions in Ter Apel are atrocious, all things considered. They do not get enough funds to house all applicants, leading to “bed shortages,” where people have to sleep outside. Food shortages have also been reported.

Everyone who comes to Ter Apel will take this first interview. Due to a high number of cases and the fact that IND is continually understaffed, the waiting time can be up to 4 months. The lower one’s chances to get asylum, the faster one gets the interview (Dublin or “safe country”) — so they can deport people faster.

Indeed, if their Eurodac file based on their identification show they have a Dublin claim somewhere, or the interview provides evidence of such, this is when a deportation order will be issued (see dedicated part).

When I was moved to the other side of the camp, I was put with a cis-guy in the same room (I am non-binary and I am not okay at all with sharing a room with a cis-guy). I have a sleep disorder and when I wake up to voices with me in the room I freak out. I tried to complain to COA about the situation, but the guy at the info desk told me to get a letter from a psychologist stating my condition and leave for the meantime or else I would get the security called for me if I refused to leave. I then went to the other employee to make a complaint about the first employee. The second employee told me to go to the reception and do it there. I did and was told that I can only file a complaint at the info desk. In short, COA refused to handle both my complaint about the roommate and the bully at the info desk. I also asked multiple times afterwards to move to a single room; although there were plenty, COA employees kept insisting that there were no available single rooms. — a queer non-binary comrade from Morocco

The RVT (Rest and Preparation Period)

Applicants meet with their lawyers for the first time and discuss answers given in the registration interview.

After the first interview with the IND, they officially say you have to wait for about 6 days for your “second interview”, the one when the official asylum claims are reviewed. Currently, the average is 48 weeks = 11 months !! of waiting for the second interview with the IND. It can also take a long time before seeing a lawyer for the first time.

It is primarily designed to “provide the asylum seeker some time to rest”. But these things are also happening:

-

Investigation of documents conducted by the KMar.

-

Medical examination by an independent medical agency (MediFirst) which provides medical advice on whether one is physically and psychologically capable to be interviewed by the IND.

-

Counselling by the Dutch Council for Refugees (VluchtelingenWerk Nederland).

-

Appointment of a lawyer and substantive preparation for the asylum procedure.

The RVT is not available to asylum seekers following the Dublin procedure (Track 1) and those coming from a so-called safe country of origin or who receive protection in another EU Member State (Track 2)

The general asylum procedure (Track 4)

The general procedure for asylum applications starts after the initial registration (first interview) and the RVT. After many months (average of a year) they send a letter for the second interview.

Then starts either:

-

Regular AA-procedure (Algemene Asielprocedure), which (officially) lasts 6 days, or AA+ 9 days.

-

Extended VA-procedure (Verlengde Asielprocedure), which officially lasts several months, because the case is deemed specific

The AA procedure consists of 1 or 2 days of interview (the “second one”), backand-forth with the lawyer and the IND, until there is a final positive or negative decision. It actually can take weeks or months, especially if one had the audacity to be sick and miss an appointment (= bureaucrashit). If the decision is negative one first receives an intention (voornemen), and the lawyer will answer with a viewpoint (zienswijze). The deadlines are all very short.

The “second/detailed interview”

The interview moment can be very intense, from uncomfortable questions related to one’s intimate identity to recalling all kinds of traumas. The IND really focuses on consistency and credibility, and uses excuses of someone’s story details not being accurate to deny them asylum, while inconsistencies can relate to traumatic facts that happened a long time ago. There is a right to see the transcript and change it with the help of the lawyer before it is reviewed for the decision.

The detailed interview can happen over the course of two days, and it takes a long time (can be 7 hours!). There can also be, as in other moments of the process, issues related to translation.

It can be useful to talk with others who have gone through it, to get an idea of what to expect.

The decision

If the decision is positive, it grants an asylum residence permit for 5 years. After 5 years, one can apply for a permanent residence permit or become a Dutch citizen — but now, the new laws ought to change this.

If it is negative, the applicant is urged to go back to their country of origin and risks being put in detention and deported by DT&V. Obviously, for a lot of people this is not an option. This means one will stay illegalized in the Netherlands, and that’s why solidarity networks are so important.

There is possibility to appeal, and also to reapply. We won’t go into details, but you can reach out if you want to know more, or check online.

Accommodation

The COA* (Central Agency for the Reception of Asylum Seekers) is responsible for the accommodation and guidance of applicants. They manage (non-exhaustive list):

-

The COL (Central Reception Center) of Ter Apel or Budel, during the registration period

-

The POL (Process Reception Centre), during the RVT and the AA procedure

-

The AZC (Asylum Reception Center)*, during the VA procedure and after. The AZC are often situated in isolated areas which makes it difficult for applicants to reach areas where life goes on “normally”, like shops, city centres etc. However, some of them (eg. Rijswijk) are closer to facilities than others, and one can request for a transfer of camp. It’s also for people who got asylum or those who have health issues that delays their deportation.

-

Emergency Center: actually many people are housed in precarious centers because there aren’t enough spots in the regular one (this is a political choice). It can be in sport and event halls, boats, cruise ships, pavilions, hotels, former schools former office buildings and in former COVID-19 test locations... Many of these locations house more than 500 people.

There is also the HTL (Enforcement and Supervision Location), for “troublesome” people. And the VBL (freedom-restricting centre), the detention center if one is waiting to be deported. And also many more actually.

All these locations are sometimes just referred to as “the camp”. We didn’t have capacity to describe it more for you in this first version of the zine — but mostly they are shit, they resembles prisons in their physical form and their rules (curfew, bad food, restriction of freedom, constant control...).

Some people leave especially the queer and the trans, to live with friends or family because there is still a lot of phobia from their fellow roommates in the camps, but they then still have to sign in at the AZC they are allocated every week. This means that they have to do a lot of public transport and pay a lot weekly which is equivalent to almost what they receive as their weekly allowance received from them, just to sign a paper proving they are still around.

— a queer non-binary comrade from Morocco

The weekly sign-ins are officially a way to make sure the person doesn’t leave the country while on procedure. In practice, they force people to travel very far just to sign a little piece of paper — it’s a disciplinary, controlling measure.

Financial support

Every week COA gives an amount of money that consists of food money and/or living allowance on a case basis (camp, family size...). If the asylum procedure has not officially started yet, they only give the food money, which depends case to case: if the camp provides food one is not entitled to food allowance, no matter how terrible the food can be (and it really is). Once the procedure has started, they sometimes add a small living allowance.

The money is credited on a “Youresafe” card (pay in store, withdraw cash, pay online). If eligible, one only gets this money once you leave Ter Apel or Budel.

Working

People in the asylum procedure are supposed to get a BSN (citizen service number) after 6 months. In order to get the BSN one needs to register in the BRP (Personal Records Database, this is with an address in a municipality). COA should provide with the information on how to do this. As you can expect now, the BRP registration time is currently longer than normal. People who already got their resident permit still receive priority for registration in the BRP, while others are put on a waiting list. In some cases it is possible to be registered with priority through an urgent process. For example, people who need a BSN for medical reasons and people without a residence permit with a work permit (TWV) and whose identity has been established by the IND.

Many people are however not even entitled to a BSN: Dublin claimants, asylum seekers from a safe country of origin, asylum seekers already entitled to protection in another EU member state, asylum seekers whose identity has not been established, i.e. when authorities have proved unable to positively assert their identity, most of the times in the absence of official documents issued by the country of origin.

With a BSN applicants are eligible for work but there is another threshold imposed: the employer needs to request a work permit (TWV, tewerkstellingsvergunning) with the UWV. This makes it even more difficult to find work, many employers don’t want to go through this hassle.

Deportation

If there is a negative decision on the asylum application, or for any other reason one’s has no right to stay in the Netherlands (such as a visa expiration), the IND will first give an obligation to “voluntarily” leave the Netherlands, which can be a period of anything between 0 and 28 days. If after this period has expired one has not left the Netherlands, the procedure to arrange the deportation may begin. If one is staying in an AZC, DT&V will request information from the COA and may try to take the person from the AZC (usually at night) to pre-deportation detention. After the “voluntary” return period has ended and the person has not left, leaving the AZC will make it more difficult for DT&V to find them. The DT&V will arrange travel documents (called a laissez-passer) from the person’s embassy.

After a period in pre-deportation detention, the DT&V informs of the deportation flight details. For a Dublin deportation this must be at least 48 hours in advance. It is helpful that as many people as possible are aware of these details. On the day of the deportation, when the person will be taken to the airport by DT&V, and two officers will go on the flight with them. Before this, one may be assessed by a doctor on whether they are fit to fly.

How people have resisted their own deportations in the past:

-

Being assessed as unfit to fly

-

Encouraging other passengers to stand up after the plane doors closed, so the pilot cannot take off

-

Mobilising communities (schools, mosques etc) to fight to stay

-

Disrupt the flight by refusing to remain seated

How accomplices have resisted deportations:

-

Go onto flights and disrupt it (wait till doors are closed and refuse to sit)

-

Organise action campaigns targeting decision makers

-

Take disruptive action to stop flights taking off (for example Standstead 16)

-

Disrupt critical points in the deportation process, be they procedural (such as meetings between DT&V and embassies) or physical (such as transport to airport).

LGBTQIA+ applicants: homonationalism at its finest

The theory and quotes of this part are mostly based on the thesis Categorization of LGBTI Refugees: Dutch Application Procedure as a Reflection of the Risk Society by Toby Zwama (2021).

SOGI (Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity) is ground for granting asylum if the IND recognizes that the applicant a) truly belongs to this category b) is in danger for it in their home country. Nowadays, over 80% of rejection cases happen due to failure to recognize the queer person for who they claim to be.

It is a good example of Dutch homonationalism (western queerness being incorporated into nationalist politics), in which the IND (and hence the Dutch nation-state) is identified as neutral, innocent and tolerant while the asylum seeker’s culture of origin is deemed traditionalist and backward, but also their subjective position not credible. Basically, to prove for a), the IND’s initial belief is that what the asylum seeker says is not true — instead, they are lying about their identity to get access to the EU’s gatekept (colonial) resources. And to prove themselves, they have to show that their queerness is compatible with a stereotypical Western definition. To be best believed, one’s life story should fit into the normal queer journey that seems to be based on the experience of some white middle-class gay man. It boils down to a narrative of 1) self-awareness, with a tipping-point, a queer epiphany at a young age, 2) a struggle, internal and external against a society that considers them as deviants 3) a one-time coming-out moment. If you are queer or know queer people around you, you can realise that this does not even fit for most of white European queers, since each experience is unique. Yet, it is expected to apply to people coming from very different cultural environments, and they must be able to express it in western terms. Otherwise, it means that they are lying about their identity and don’t deserve to stay in this very tolerant country: they are not the good gays that can contribute to the liberal nation-state.

On top of this linear life-story, applicants must label themselves within IND’s five possible categories for identification: lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or intersex. They also have to know about the “queer scene” of their home-country as well as the Dutch one, otherwise it is deemed supsicious. They must as well be very specific about their sexual intimacy, which has to fit homo/lesbophobic and sexist stereotypes: gay men as very sexually active, while lesbian sex is never real enough (they are just very good women friends...).

Obviously, luck also plays a role: the IND officers do not all have the same level of knowledge about queerness, the same empathy, or the same approach. But there are many examples to show that they mostly just suck.

Such as, these IND rejection letters specially curated for you:

-

The classic “suffering queer stereotype” — “The statements of the person concerned that he had no difficulty accepting his homosexuality and that he only liked it, render insufficient insight into how he experienced his orientation and feelings.” (about Arthur, Asia, 2016)

-

The “why are you not a flamboyant hypersexual gay man now that we let you be free?” — “It is taken into consideration that the person concerned has had only one contact in his life with a man that was also sexual. Now that the person concerned has been in the Netherlands for five and a half years, it can be expected that he has given expression to his stated orientation more extensively and that he would have gone in pursuit of his identity, especially now that homosexuality in the Netherlands is accepted more than in Afghanistan and the person concerned could have moved more freely in this respect. The person concerned has failed to do this.” — (about Walt, Afghanistan)

-

The “gay species always seeks for each others” — “It is also surprising that the person concerned states that he has lived as a homosexual in [country of origin] for many years but that he does not know of the existence of LGBT organisations in his country of origin.” (about Anthony, Africa, 2016)

During the eight months here with the COA I have suffered a lot because of the lack of cooperation and not taking into consideration that I am a trans man. I get into a lot of trouble with people when they know my identity in any way. I haven’t seen a trans doctor yet and I haven’t been able to change my name on the papers... I’m just waiting — I don’t feel safe in the camp and I always live far from it. I don’t feel stable. I suffer from having to go back weekly for fingerprinting and I don’t have enough money to pay the train every time.

— a trans comrade in the asylum procedure

We very highly recommend the zine “You’ve applied for asylum, now what? (A guide for queer and trans asylum seekers) to get a deeper understanding of what it’s like and how to support.

Email noborderzinenl@proton.me to get the pdf!

Or link: cryptpad.fr

Living without the right documents

Housing

Finding housing in the Netherlands is famously difficult, both economically and bureaucratically. Here we list a few options to access or share housing. If you are in the procedure and are living in a camp, you can move somewhere else at the condition that you regularly show up for stamping, as a proof that you haven’t left the country. The frequency at which you need to stamp vary according to the camp and the organization that manages it: some camps require you to show up in person weekly or biweekly, some allow you to do a verification via phone... we recommend checking the specifics.

It is possible to live somewhere else and stamp even while being in Ter Apel, if the process is taking a longer time than usual. In this case, it is required to go stamping more frequently, which can be quite complicated considering the bad and expensive transport connections to Ter Apel. It might be worth it to get a monthly train subscription for that purpose, which costs around 200 euros and allows you to use all trains (but only trains, no buses or metros) outside of peak hours.

In Amsterdam, Maya Angelou Opvang provides shelter/refuge for (all!) women. They have a program in place for undocumented people, which offers shelter and a living. Be aware, if you go there as undocumented, they work with the Municipality of Amsterdam, and will start the program with you to find a solution to your documentlessness. That means that there’s a chance that the program fails for it’s back at square one. Their contact is ongedocumenteerden@amsterdam.nl.

Squatting

Here you arrive at the section about squatting*! Yay! Be aware: the comrades who write this have an especially idealistic, anarchist conception of squatting, after living together in a beautiful squat for the best part of a year. We will try to be impartial ;)

We believe that squatting can be a great option for people who want, or need, to move out of their camp but don’t have the money or correct documents to find official housing. Squatting, or kraken in Dutch, is the occupation of buildings that have been left empty by their owners, for the purpose of housing or social and political spaces. In the Netherlands, many squats are used for both purposes: people living there, but also since they are political in nature some tend to host assemblies and events in the social spaces (one allocated part of the squat that is not for living). The political nature of squats means they are, for the most part, dedicated to alternative ways of co-habitation, as well as anti-racism, queer and trans friendly, and anti-hierarchy in all its forms.

Squat-FAQ

Isn’t squatting dangerous, risky???

Of course, squatting, living outside of and against the usual housing system, is not completely without risk. However, we want to reassure you that in most cases, living in a squat does not put you in danger!!! The illegal part of occupying empty buildings is at the very beginning, with “breaking and entering”. Once squatters have started to live in the building and announced themselves to the neighborhood and to the cops, they have the right to stay, until a legal court case orders their eviction. Unless that is the case, cops cannot enter the building without a search warrant.

Of course however, if squatters lose the court case, the house can be evicted. The entire legal process usually takes enough time for people to organize alternative housing arrangements for people, who can be either hosted by non-squatting comrades or in other squats until a new solution is found. If the idea sounds very stressful, you might consider checking out more long-standing squats, talking to the people who’ve been there for a while and trying to assess what is the relationship with the owner.

Isn’t squatting intense/stressful/dirty?

If you’ve heard about squatting, it might be that you have encountered the general stereotype that it is a chaotic living condition. As in all cases of living with other people, squatting can be difficult for those who have a low tolerance for mess or dirt. But living in a squat is not necessarily more chaotic than other housing options. The general material and social atmosphere depends on the people who inhabit the squat and the intentions they have for their living space. Depending on your needs and desires, you can try to understand a bit about the character of the squats you approach by either visiting the social events, or generally speaking to people. In addition, squatting is a collaborative living project, which means that the people who live in the house have a say in the way that things work, so the atmosphere is always changing and open to change.

How can I get involved?

Well, luckily we have KSUs — KraakSpreekUur — squatting assistance hours. Here, you can meet comrades who can tell you more about the squatting scene in your city and help you get involved. You can check out the website radar.squat.net to find out when they are!

Safety and privacy for squatters*

Due to the “illegal” nature of squatting, many people living in squats prefer to keep their identities and activities private to prevent surveillance by the government. This is also true with respect to undocumented people, some of whom may be laying low to avoid deportation. When you are in this environment, keep in mind the privacy concerns of your comrades. Avoid taking pictures or videos in the house which may expose the people who live there, and be careful about the information you give out to those outside the community. Even outside of the squats, it is a good idea to learn about digital security and privacy to avoid incriminating anyone with or without the “right” documents.

Work

People who are in the asylum process have the legal right to find ways to subsist. Most people who first arrive to the country are not allowed to work right away, but can apply for a work permit after 6 months in the process.

In some cases, the one in real legal risk is the employer that hires the undocumented person. However, some employers use the vulnerable legal status of the employee to manipulate them and force them to work under very bad conditions, knowing they will not be able to fight for better conditions for risk of exposing themselves.

Fairwork.nu is an organization that helps with that.

Exploitation of undocumented people is rarely addressed by the Dutch government — from 2011 to 2017, 1300 cases were reported but only 25 convicted. One inspector stated that most officers “don’t want to know too much because you’ll have to do something about it”, and that “a lot of restaurants will close. We will have dirty houses because no one cleans them anymore”. Capitalism benefits and exploits a “deportable labour force”, who they can pay cheap wages and offer no garantee of rights. It is then extremely difficult to unionise, and making a complaint risks your residence status in that country.

COA withdrawing parts of salaries

When working while living in certain camps, part of one’s salary (about 70%) needs to be given to the administration to allegedly sustain your expenses for using the room at the camp. This is the case even when one doesn’t spend time at the camp but just show up weekly for signing. This is not only outrageous but also practically very annoying, so it is good to know and inform oneself about when considering work options.

Illegalized work and tips to navigate it

In order to circumvent the problem of salary withdrawal, or in general the many legal/bureaucratic obstacles to working while being undocumented or in procedure in the Netherlands, it is possible to work without contract. Obviously this is illegal and not easy, creating a specific set of vulnerabilities and obstacles. It makes the employer, as well as the networks that control the undocumented labor force much more powerful than the workers.

Solidarity tip:

If you are working with a contract and know that some of your colleagues might be working without one, consider checking in with them — without being a cop! Working shifts usually include also times of (sometimes very quick) rest or chatting with colleagues. It’s important that we use these moments to establish solidarities with one another, getting to know each other and see how we feel in the workplace. This is the basis of workplace organizing, breaking our isolation! However, it’s very important to keep in mind that sharing information and thoughts about the workplace and working condition might not be comfortable for everyone, especially when there are concrete risks to it. So please don’t push people to share and keep the white saviorism at bay: do not take any action/share any information without checking in with people first!

Studying

There are different programs for people in the asylum seeking procedure to go to university, such as InclUUsion (Utrecht University and Leiden University) or WURth-while (Wageningen University).

This section is fully written by someone sharing their first-hand experience, as an InclUUsion student.

The first place I lived in was an emergency shelter in Enschede, a former military plane hangar turned shelter. When I was accepted to the InclUUsion program I went to the COA and asked to be transferred closer to Utrecht so I can attend the course, there answer was NO “If we transfer you then other people will apply for different courses and we will end up being a transfer service company not an agency that shelters asylum seekers” — those were the words more or less from the COA employee. I then went to the Vluchtelingenwerk, which only visited the shelter twice a week and did not have a permanent office. After complaining about the situation and telling the employee “do they want us to just eat, sleep and slowly die” he took it upon himself to help me, this was an individual effort. He emailed the COA, that is when the manager of the COA came to me saying “Ahh you should have not escalated the situation, if only you talked to me we could have found a solution together” in the most innocent way. It was then when they finally approved covering my transportation, noting that only came in the second week of my course, the first week I paid from the 30 euros they use to give us weekly. I had to cut one meal for 3 weeks to save the money for that trip. Now the main problem was when I got transferred after three months. Even though I was already taking a course and had shown the COA that I was actually going and attending, none of this was taken into account and I was transferred to the AZC in Baexem, a village 15min by bus from Roermond in Limburg. There I again had to fight for transport support from the end of block 4 to the beginning of block 1. The transport support was only approved a week before my course. I would have to go through the same fight in April the next year when I was transferred to Oisterwijk, again not close to Utrecht.

Many InclUUsion students face two major problems. The first is that most people cannot get transport cover, for example travelling to Friesland twice a week. Only a few would be able to secure transport support, and less than that would actually be transferred to AZCs close to Utrecht. The main response they all get “who told you that COA covers transport fees for couses”.

The other issue facing InclUUsion students is the weekly stamp, I was lucky or perhaps a fierce fighter who does not take no for an answer. I know many students who have to miss one class or arrive late to the lecture/seminar because the COA would not give them an exemption from the weekly stamp. It is important to note that an exemption is easily given to the individual if they are working, thus a big part of there salary goes to the COA. But if you want to learn, well then no one cares, because refugees are nothing but human capital made to come and serve the captalist system, I guess modern slavery. I know a student who had to quit the course because the lecturer informed them that attending the lectures was mandatory for the course and the class was conducted in a similar timeframe as the weekly stamp in the AZC. To be fair the lecturer was so pissed off that they offered to write a letter to COA in order to ask them to give the student an exemption, but fairly enough the student was afraid COA would react negativly and make their lives worse than it is in the asylum center and politly rejected the request. There are way more stories out there but unfortunately many asylum seekers and refugees are constantly afraid of speaking up because we are always told that speaking up might affect the procedure of applying to the citizenship in the future. While that might not be true, the narrative is a bit to strong, especially now with the a right wing cabinet in charge.

Physical and mental healthcare

One of my best friends arrived at Ter Apel, a trans woman from a country where being trans is not technically illegal, but systematically socially punished. At detention centres and “refugee housing” (AZC) throughout the country she was beat on (verbally and physically) by staff and other residents, and disrespected + misgendered constantly. Her application for asylum went through, somehow, but the trauma of “immigration” became too much for her. She took her own life three years ago and cited the treatment at detention centres right here in The Netherlands as one of the reasons for her suicide, saying that she would never be able to let the trauma go. I miss you, Liah. — a friend