Ole Martin Moen, Aleksander Sørlie

The Ethics of Relationship Anarchy

2022

2. Where Mainstream Relationship Norms Are too Restrictive

3. Where Mainstream Relationship Norms Are too Permissive

1. Introduction

When people talk about anarchism, what they have in mind is typically political anarchism, that is, the view that there should be no state. As the philosopher and anarchism scholar David Miller observes, however, anarchism itself is a more general view, namely the view that there should be no rulers. Miller writes that “although the state is the most distinctive object of anarchist attack, it is by no means the only object. Any institution which, like the state, appears to anarchists coercive, punitive, exploitative or destructive is condemned in the same way”—including, for example, religious institutions, schools, or economic systems (Miller 1984: 8). In this sense, one can be an anarchist about different things. Relationship anarchy is anarchism about personal relationships.

Several thinkers in the anarchist tradition have held views on personal relationships (e.g., Godwin 1793; Bakunin 1866; Goldman 1910). In what follows, however, our focus is not on the general issue of anarchist views on relationships, but on the ideas of the contemporary movement of self-identifying relationship anarchists.

The ideas of relationship anarchy in this sense—hereafter RA—have been developed in queer and countercultural communities over the last two decades. Rather than focusing primarily on mechanisms of political power, RA theorists have been concerned with understanding and challenging the power dynamics at play in close personal relationships. Andie Nordgren, the movement’s central, founding theorist, describes RA as a radical commitment “to avoid defining relationships by attempts to exercise power over each other” (Nordgren 2018).

Our aim is to give a concise presentation and defense of RA. We will approach RA as a theory in applied ethics—in particular, as a theory in sexual ethics and relationship ethics—and relate it to ongoing debates in these areas. We, the authors, are both queer men with a background in countercultures where RA is widely practiced and discussed. One of us is an activist working on trans- and sex workers’ rights (Sørlie), the other is a philosophy professor (Moen). Although we make several claims about the scope, content, and justification of RA, we do not claim to speak with any special authority on the issue. Moreover, many of the points that we make here, while not attributable to a specific source, are not original to us, but are the result of several years of fruitful discussion with others in the RA community.

We start by considering the cases where, from an RA perspective, current mainstream relationship norms are too restrictive. Then we turn to the cases where current norms are too permissive. Our views on what counts as “mainstream” relationship norms are, no doubt, influenced by the fact that we are writing from a Scandinavian perspective.

We then proceed to consider the relationship between RA and polyamory. We argue that RA is compatible with some, but not all, forms of polyamorous practice. We also argue that, from an RA perspective, the increasingly popular term “consensual non-monogamy” is a misleading term that should be avoided. In the conclusion, we explain how RA, as a position in applied ethics, can be justified within consequentialist, deontological, and virtue ethical frameworks alike.

We have restricted our scope, in what follows, to chosen relationships between adults. Thus, we are not dealing with, for example, kinship relationships into which one is born, nor relationships between adults and minors. Although many issues and arguments deserve to be explored in greater depth than we can do here, we hope, nevertheless, to be able to convey the main nature and thrust of RA.

2. Where Mainstream Relationship Norms Are too Restrictive

Over the last century, relationship norms (i.e., prescriptions for how interpersonal relationships ought to be conducted) have become increasingly permissive. In the Western world and beyond, homosexual relationships, interracial relationships, pre-marital sex, and divorce are now widely accepted. Nevertheless, in the RA movement’s founding text, “A short instructional manifesto for relationship anarchy,” Nordgren (2006) writes that there is still “a very powerful normative system in play that dictates what real love is, and how people should [conduct their relationships]. Many will question you and the validity of your relationships when you don’t follow these norms.”

What are these norms, and in what ways are they unduly restrictive?

To approach the RA position, we can start by observing that, from very early in life, we learn that personal relationships fall into distinct categories. A person might be, for example, a “friend,” “date,” “romantic partner,” or “spouse.” If it is unclear which category a particular relationship belongs to, we are often keen on trying to get the issue settled. This is understandable, since very often, relationship categories do not just serve a descriptive purpose; they are also regarded as normative for what the relationships should involve and how they should develop over time.

Let us consider some examples. In the case of friendships, it is commonly accepted that several people may, at the same time, be one’s friend. In the case of a romantic relationship, however, one should not have more than one at the time.

In the case of friendships, it is commonly accepted that these may grow stronger or weaker over time and that this does not need to cause an abrupt end to the friendship. By contrast, romantic relationships are commonly expected to develop along a one-way trajectory. This trajectory has been described by the writer Amy Gahran (2017) as “the relationship escalator”: it is the assumption that a date, or series of dates, should (if successful) escalate to a romantic relationship; a romantic relationship should (if successful) escalate to moving in together; and moving in together should (if successful) escalate to marrying and working to make a nuclear family. Although it typically is seen as okay to wait for some time at a certain step before going further, one must be moving forward; otherwise, the relationship is not developing the way it must if it is to be regarded as successful. Moreover, one may not de-escalate any such relationship without thereby ending it completely. In cases where such a relationship has ended, the other person becomes one’s “ex.” In that case, it becomes suspect to continue to be emotionally and/or physically involved with that person.

Now, it is understandable that relationships of a given kind will tend to develop along a certain trajectory. In a variety of circumstances, following such a trajectory may be entirely sensible. The problem, from an RA perspective, arises when a particular trajectory is regarded as prescriptive for how every relationship in a given category should develop. This is problematic because we humans are not just identical tokens of the general type “human.” Rather, we are particular persons with particular needs, wants, plans, habits, strengths, bodies, personalities. No two persons are exactly alike and no two social situations are exactly alike. So, as Nordgren observes, “every relationship is unique” (Nordgren 2006).

Consequently, according to Nordgren, we should not treat the people in our lives as tokens of various types of relationships. We should strive to be attentive to the people that we care about as the unique human beings that they, in fact, are. Based on the particular facts that pertain to each given relationship, including the values, needs, and aspirations of those involved, we should “design [our] own commitments with the people around [us]” (2006).

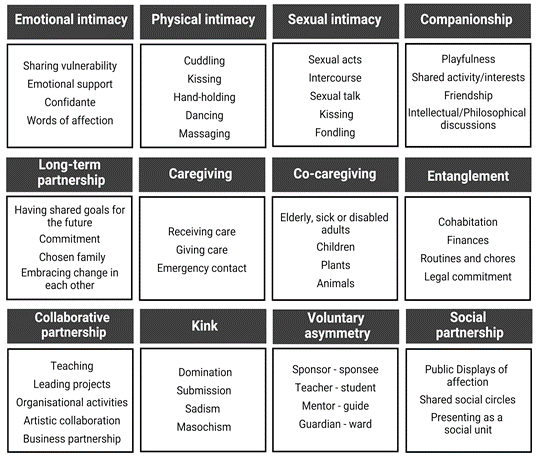

What might “designing our commitments” in this sense involve? Consider the following Relationship Anarchist Smorgasbord (Fig 1), which sketches some of the central areas of relationship involvement as well as indicting some of the “design” options within each area:

In some relationships, a conventional cluster of facets, and a conventional developmental trajectory, will be a good choice for the parties involved (given their values, circumstances, needs, and so on). In some cases, however, it might be preferable to have—for example—a long-term partnership that involves cohabitation, co-caregiving, financial entanglement, and emotional intimacy, but within which one or more partners pursues physical and sexual intimacy in other relationships (as in some forms of polyamory). In other cases, it might be most suitable to have a romantic relationship that spans over several decades without cohabiting. For two neighbors it might be rewarding to meet to cuddle, benefitting from the associated oxytocin release, even if there is no desire for escalating the frequency of such encounters or to stress about dinner invitations.

To the extent that we restrict ourselves to the standard “package deals,” we lose out on relationship goods that can be gained due to facts about a relationship that, although not generally common for relationships that fall under this category, nevertheless pertain in this particular relationship.

Escalation norms are restrictive. If A ought to lead to B, and B ought to lead to C, then people who would like to do A and B together, and who would both benefit from doing so, will be discouraged from doing so in case one of them (or perhaps both) is reluctant to commit to be moving toward C.

It is perfectly understandable that some combinations of facets are much more common than others. Which facets a given relationship should include, however, depends on the particular values, needs, and circumstances of the parties to that relationship, not on the broader relationship category under which the relationship is subsumed. RA, we might therefore say, rejects category-based relationship norms.

Relationship anarchists also reject relationship norms rooted in categories such as gender and sexual orientation. To illustrate what this might mean, let’s say that Charles, a man, is sexually attracted almost exclusively to women, and that his interest in developing a romantic relationship is directed toward women only. According to the mainstream taxonomy of sexual orientations, Charles would be considered “straight.”

Let’s say that Charles is also, however, sexually drawn toward a narrow range of men or non-binary people too—possibly limited to an interest in some specific form of sexual interaction. One person within this narrow range is a man named Robin and, as it turns out, Robin is likewise sexually drawn toward Charles. According to RA, the fact that Charles is socially categorized as “straight” and/or that Robin belongs to a category most of whose members Charles is not attracted to, is not, by itself, relevant for what Charles should do in relation to Robin (e.g., in pursuing a sexual interaction). Charles, moreover, should not need to worry that, in case he and Robin do share a sexual encounter, he undergoes a category change from “straight” to “bi” or “gay,” which in turn binds him to different norms for how he should act in the future.

If categories function to limit persons’ willingness to try out potentially valuable forms of intimacy (thinking, for example, “a straight man can’t do that!”), such categories are unduly restricting. It is regrettable if we let stigma related to being perceived as a member of the “gay” or “bi” categories to stand in the way of mutually rewarding sexual relations. It is also regrettable if such stigma stands in the way of emotional and physical (yet non-sexual) intimacy between, for example, two straight men.

Although it can be highly rewarding to pursue relationships that diverge from the commonplace norms regarding the relationship’s content and development, doing so comes with a heightened need to be explicit about one’s boundaries, preferences, plans, and expectations. The further one diverges from the well-trodden paths, the less one can take for granted. Nordgren writes that:

radical relationships must have conversation and communication at the heart — not as a state of emergency only brought out to solve ‘problems.’ Communicate in a context of trust. We are so used to people never really saying what they think and feel — that we have to read between the lines and extrapolate to find what they really mean. (Nordgren 2006)

Importantly, RA does not commit anyone to pursue radical relationships. It is in fully line with RA to decide to have just one sexual and romantic partner, and to make a long-term commitment to sharing responsibility for raising one or more children with this partner only. Nordgren writes:

Life would not have much structure or meaning without joining together with other people to achieve things — constructing a life together, raising children, owning a house or growing together through thick and thin. Such endeavors usually need lots of trust and commitment between people to work. Relationship anarchy is not about never committing to anything — it’s about designing your own commitments with the people around you. (Nordgren 2006)

3. Where Mainstream Relationship Norms Are too Permissive

In the previous section, we considered a number of mainstream relationship norms that, from an RA perspective, are too restrictive. Are there also, however, mainstream relationship norms that are too permissive?

According to Nordgren, it is a fundamental concern of RA that people should “avoid defining relationships by attempts to exercise power over each other” (Nordgren 2018). This makes it necessary not only to identify and counteract the ways in which others have undue power over oneself, but also to identify and counteract the ways in which oneself has undue power over others. This, moreover, places restrictions on how we may proceed in relation to the people around us.

Most crucially, it makes it necessary, before one extends an invitation to someone to do something sexual or otherwise intimate together, to ensure that the person is genuinely free to either accept or reject the invitation.

The central reason for this has recently been well put by philosopher Quill Kukla (2018), who observes that to invite a person to do something is (virtually) never just to share neutral information with that person. There usually is a want, on the part of the person who asks, for this thing (e.g., potential sexual interaction) to be done, or at least to be explored; otherwise, the person would not be asking. In many situations, however, asymmetrical power (e.g., dependency) relationships between people are such that the person who receives the invitation might have reason to worry about the social, economic, or career-related costs of declining the request. This is one reason why, in hierarchical relationships in which the parties have (e.g., institutionally reinforced) asymmetrical power or authority over one other, sexual invitations should almost always be avoided. To tell someone that they don’t need to fear unfavorable consequences if they decline might, in some circumstances, be sufficient, but if they are dependent on your future goodwill, and they don’t know you well enough to be confident that there would indeed not be any risk involved in saying no, you should—from an RA perspective—refrain from even asking.

It has, in recent years, become more widely recognized that having to be constantly prepared to handle invitations, including flirting, is burdensome, and that we therefore need neutral spaces—in professional environments in particular—where people can be free from having to worry about receiving requests that they must find a safe and appropriate way to respond to (see Kukla and Herbert 2018).

The issue of extending invitations, however, is not the main issue that we will address in this section. Instead, we will consider monogamy.

It is perfectly compatible with RA for anyone to choose to act monogamously, that is, to have only one sexual and romantic partner. No one is under an obligation to be sexually and/or romantically involved with anyone with whom they do not want to be sexually and/or romantically involved. What we are considering, in what follows, is therefore not the practice of acting monogamously, but the practice of requiring that one’s partner act monogamously.

How should we think of this requirement from an RA perspective? First, it is compatible with—indeed, it is encouraged by—RA to negotiate the scope and content of one’s relationships. Moreover, while some issues related to scope and content might be up for reconsideration or compromise, it is also compatible with RA to have strict requirements about the nature of a relationship one is willing to enter into, or to continue. If one values highly to have a romantic partner who is also one’s domestic partner and wants a partner who shares one’s excitement about domestic pleasures, it can be perfectly fine not to be willing to invest in a relationship with a partner who will be away most afternoons and evenings. Although requiring that one’s partner is at home all afternoons and evenings of the week would be excessive—according to mainstream norms and RA norms alike—to require that one’s partner, during a normal week, is at home for most of the afternoons or evenings can be a reasonable precondition for being willing to invest in the relationship.

Notice, however, that monogamy requirements are requirements concerning neither the scope nor the content of the relationship between oneself and one’s partner; monogamy requirements are requirements about what one’s partner may do in their relationships to others during the time (of whatever frequency or duration) that they are not together with oneself. Within the sexual and/or romantic domain, this is an exclusivity requirement; a requirement to be granted monopoly privilege over engagement with the other sexuality.

Exclusivity requirements are widely regarded as acceptable in romantic relationships. Notice, however, that such requirements look very strange in the context of friendships. Let’s say that two friends, Jack and Jane, both love reading and often get together to discuss literature. Then Jack says to Jane that he thinks discussing literature is “their thing,” and that he will remain friends with her only on the condition that she does not discuss literature with anyone else—and, indeed, that this rule applies even on days when Jack is out of town, when he is busy doing other things, or when he just doesn’t feel like hanging out with Jane. In this case, it seems clear that Jack’s requirements are not okay; they are controlling and restricting beyond what is acceptable.

Importantly, Jack would not be able to justify this requirement by appealing to the claim that, in fact, Jane only wishes to discuss literature with him. The reason this justification does not work is that insofar as this really is the case, the requirement is redundant. The requirement is relevant, and kicks into action, only insofar as Jane might in fact want to discuss literature with someone else; the requirement serves the purpose of discouraging her from doing so.

But if exclusivity requirements are not okay in the case of friendships, why are they okay in the case of romantic relationships? If there is a difference here, this would require a justification. Let us consider some possible justifications.

The Appeal to Risk of Pregnancy

One argument for the permissibility of having a sexual exclusivity (monogamy) requirement in romantic relationships appeals to the risk of pregnancy, which adds a layer of seriousness to romantic and/or sexual relationships (in that they may result in offspring for whom would have a significant obligation of care). The argument holds that this risk justifies exclusivity requirements within this domain. It has been suggested to us, on several occasions, that although RA norms might be sensible in queer communities, where sex is usually disconnected from reproduction and parental responsibilities, these norms cannot be generalized to the straight majority population.

First, many queer RA theorists—including the movement’s founder and one of the authors of this article—are parents. So it is not quite right to suggest that concerns about potential parenting responsibilities are not an issue within the queer community. Second, insofar as such potential responsibilities are a concern, it should be remembered that many forms of sexual intimacy carry no risk at all of pregnancy; indeed, there is only one form that does so among many hundreds that do not: inadequately protected vaginal-penile intercourse between two fertile individuals. Third, since the 1960s, the contraceptive pill and the right to abortion have made sex in straight relationships centered more around sexual pleasure than around reproduction, and job opportunities for women and the right to divorce have reduced dependency and pushed straight relationships in the direction of more equality of power between the parties. Over the course of relatively few decades, therefore, straight relationships have come to function under conditions that are much closer to those under which queer relationships have functioned all along.

A conservative approach to social norms, according to which we should give weight to norms that, over time, have proven viable given a set of preconditions, suggests that we are now in a position to give increased weight to queer relationship norms, since they have proved themselves viable under the relevant conditions (conditions which increasingly apply to straight relationships in mainstream culture). While straight relationship norms have evolved, over millennia, to be adaptive in patriarchal societies where there is a close connection between sex and reproduction, queer relationship norms have evolved mainly in modern societies, without this connection. Moreover, they have proven able to generate close and supportive social environments that, over the last two decades, have even proven to be robust in facing all kinds of rapid changes, such as the widespread adoption of digital technologies.

Nevertheless, we concede that in many relationships—especially those that involve parental responsibilities—it is legitimate to require of one’s partner that they do not engage in sexual activities that expose them to the risk of having to take on parental responsibilities that are incompatible with their current responsibilities. But it should be noted that this type of requirement is not specific to the taking on of parental responsibilities. It is equally justified in the case of taking on financial, professional, and other caretaking responsibilities that are incompatible with meeting existing obligations.

In this context, we will also briefly comment on the risks of contracting sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Many forms of sexual intimacy that carry no risk of pregnancy nevertheless carry risks of contracting an STI. It is not contrary to RA, moreover, to want to be vigilant in taking measures to avoid infections; for some, for example, persons with immunodeficiency, to be vigilant in this respect can indeed be a vital necessity. However, insofar as one’s motivating concern is vigilance in lowering risks of infection, there is reason to think that this concern should be equally weighty for all (similarly serious) risks of infection—including the risks of infection associated with having a partner who has a high-social-contact job, for example, as a cashier, preschool teacher, or nurse. A concern about one’s own health does not, by itself, warrant an excessive concern with infections that might be contracted due specifically to one’s partner’s sexual intimacy with others. Moreover, this would not be a reason to object to one’s partner engaging in sexual intimacy that carries virtually no risks of contracting STIs (e.g., many forms of kink, rubber fetishism, and sex centered on the use of sex toys), or to sexual intimacy that carries moderate risks as long as one waits until test results return before one has unprotected sex with one’s partner. For these reasons, appeals to STI risks cannot justify monogamy requirements as they are commonly understood.

The Appeal to the Right to Set One’s Own Terms

Another argument for the permissibility of monogamy requirements is that one has a right to set any criterion that one wants for being willing to enter or continue a romantic relationship. In considering this argument, it is important to distinguish clearly between what should be allowed to do, legally, and what it is ethically acceptable to do. If the argument is meant as a claim about what one should be allowed to do, legally, it is not an argument against RA. Anyone should be free to leave a relationship for any reason, without fear of criminal prosecution.

It does not follow from this, however, that any reason for leaving a relationship is equally ethically acceptable. First of all, if it were ethically acceptable to set whatever criterion one wishes as a precondition for continuing a relationship, then, presumably, this should also apply to friendships. As we saw in the case of Jack and Jane above, however, it seems that Jack’s stated precondition for continuing his relationship with Jane was not acceptable; on the contrary, it was objectionable due to being invasive and controlling.

This is also the case, intuitively, for many preconditions for continuing a romantic relationship. Consider a situation where a man ends his relationship with his wife because she gets promoted at work and thereby starts to earn a higher salary than he does, something which, in his view, improperly skews the power and prestige in the relationship. This would not be ethically acceptable. Presumably, it would hardly have been more acceptable if he had told her about this criterion earlier on, that is, when the relationship was just beginning, thus discouraging her from advancing in her career. Or, as an alternative, imagine that a woman tells her husband that she will end their relationship unless he gives her the option of listening in to all of his phone calls with his friends and family. To place such a requirement on one’s partner would be to engage in isolating and controlling behavior, and constitute psychological abuse.

Here it might be said, in response, that the spouse in either example should simply say no and reject the requirement. We agree that, ideally, this is what they should do. Yet at the same time, we have to acknowledge that an individual might well be in a situation where it could be very costly for them to “refuse” the conditions that are being placed on them as a basis for a relationship continuing. Even if we keep potential physical threats aside, one might be financially, socially, or psychologically dependent on one’s partner in such a way that it is too risky for one to do anything else than to accept the abuse.

It seems clear that when two persons in an intimate relationship are doing something together, the agreement of both parties is necessary for what is going on to be morally acceptable. It does not thereby follow, however, that the agreement of both parties is sufficient for moral acceptability.

A crucial tool for preventing abusive behavior in power-asymmetrical relationships is to limit the scope of what is up for negotiation (see Waltzer 1983). This is something that, in the case of work contracts, is widely accepted. Although some libertarians might disagree, most of us believe that there should be clear limits to what can be included in work contracts, and also, clear limits to when and how they might be renegotiated. The reason is that, without this, we open ourselves up for extremely exploitative behaviors. Imagine, for example, that an employee is currently in a life-crisis situation where the sudden loss of employment would be devastating to them and their family, and where their employer learns this and uses the opportunity to make extreme demands in the work contract. Even in more ordinary cases, most of us would object to work contracts that, for example, dictate who one is allowed to be with when one is not at work.

While power asymmetries in the relationship between employer and employee can be stark, we must acknowledge that many people face even starker power asymmetries at home than they do at work. By this, we mean that they would have less to fear, all things considered, if they did something that displeased their employer than if they did something that displeased their domestic partner. While one might be dependent on one’s salary, there are often other possible employers, and there are limits to how far into one’s private life one’s employer can reach. For this reason, analogously, we need limits in domestic relationships about what is regarded as socially accepted to bargain about. In other words, there must be spheres in which, despite current power asymmetries or power asymmetries that might come to develop over time, one’s choices and behavior cannot be controlled by the person who has more power.

Advocates of RA would say that there are many spheres of a partner’s life that it is unacceptable to demand control over. A key example of such a sphere is what one’s partner does in their relationship with other people when one is not around. Recall, moreover, that the claim here is one regarding moral acceptability—by contrast, in the case of employer-employee relationships, the common view is that the restrictions on what spheres should be up for negotiation should be legally or politically enforced.

To bring the analogy back to friendship, we can ask: Does the foregoing analysis mean that it is wrong to assess friends on the grounds of what they do when they’re not with you? Here is a reason for thinking otherwise. All of a person’s actions reflect on them, whether you happen to be directly observing them or not. If one gets to know that a friend, say, harasses people and advocates for racist views online, that is a good reason for ending the friendship. If you are vegan, and this is important for you as an ethical issue, a partner gorging in meat when they are not with you could also be grounds for complaint. Actions that are wrongful no matter with whom they are done, would also be wrong if done only with the two of you together. But that cannot justify monogamy requirements. Presumably, you hold that sexual intimacy between consenting adults is morally permissible, certainly when engaged with yourself. But if you think an action is morally permissible when done with you, you think that action is morally permissible. Monogamy requirements, therefore, cannot be justified by appeal to this line of reasoning.

The Appeal to Jealousy

Philosopher Roger Scruton (1989/2001) defends monogamy rules by appealing to jealousy. Jealousy, he writes, makes a man “prey to horrible thoughts and fantasies which he cannot shake off” and it “shatters the world of the lover, by destroying the myth of his uniqueness” (164). Scruton suggests that “the power of jealousy is one of the most important facts to be taken account of in the derivation of sexual morality” (167), including in the defense of monogamy rules.

One problem with this argument is that monogamy rules do not remove jealousy. Jealousy is, after all, rampant in relationships that are governed by monogamy norms. From our perspective, it seems clear that monogamy norms perpetuate jealousy, the reason for which is that they increase the extent to which people must compete. Given the monogamy norm that only one person can be your partner’s intimate partner, then others with whom your partner might be interested in being intimate are indeed a threat, since in that case, they will have to replace you. There is no room, given monogamy, for your partner to have an intimate relationship with the other party now and then while still being your intimate and, say, domestic partner. Philosopher Harry Chalmers writes, regarding both romantic and other forms of jealousy, that “the kind of context in which jealousy most readily stews is that of a refusal to share.” He suggests, moreover, that “rather than confronting the underlying needs or problems that jealousy indicates, monogamy is instead simply a way of avoiding behaviors that trigger jealous feelings” (Chalmers 2019: 236–237).

In considering how jealousy should be dealt with in the case of adults, relationship anarchists have suggested that it is useful to see this in connection with how we deal with jealousy in the case of children. Children will often be jealous and possessive, both about things and about other people. They might demand that no one plays with their toys, even when they themselves are not around to use them, and siblings might be jealous about other siblings’ parental attention. In “A Green Anarchist Project on Freedom and Love,” Mae Bee writes:

The infant often reacts to a new sibling at its mother’s body with extreme jealousy, intense feelings of rivalry and anger, and ultimately ownership. As adults we watch with sympathy but not horror. We do not expect the mother to put the newcomer away or keep her love for the new one out of the older child’s eyeshot. We expect instead that the mother will reassure the first child she still loves and cares for it as well as assuring the child she loves and cares for the new baby also. (Bee 2004)

It is noteworthy that we place higher requirements on children for dealing with jealousy than for adults. This point is also touched on by Chalmers, who writes that “partners should confront their jealous feelings head-on. They should take responsibility for their feelings, seek to overcome their insecurities, work to free themselves from the fears and false assumptions that give rise to the problem in the first place. They should, in short, take the path of greater maturity” (Chalmers 2019: 236).

This does not, however, imply that we should simply disregard jealousy in adults; it really is an emotion that hurts. The way to handle that emotion, moreover, is not to use one’s power to dictate the lives and relationships of others. It is also important to emphasize that although jealousy might feel instinctive and unavoidable when it occurs, how we understand, conceptualize, and handle this emotion when it occurs is socially contingent. One possible way of handling the emotion is to actively cultivate what is called compersion; the taking of joy in one’s partner’s joy, including when their joy is derived from sexually intimate behavior with others (see Sousa 2017; Brunning 2020).

As an illustration of social contingency, it is worth pointing out that in Swedish—the language in which the RA manifesto was first written—the word for jealousy is svartsjuka, which literally translates as “black illness.” To be jealous, then, is identified as an unhealthy response.

We also want to point out that insofar as the aim of averting a partner’s jealous feelings is a weighty consideration that justly restricts one’s relationship to other people, this should presumably also restrict one from interacting with other people in ways that might raise suspicion. To protect his wife from feelings of jealousy, a man then has normative reasons to avoid forming close, yet non-sexual, friendships with women, and to make sure not to be in situations that could give rise to suspicion if spotted by friends and acquaintances of his wife.

This illustrates how monogamy requirements, especially if justified by appeal to jealousy, can be highly invasive and restrictive. It should be no surprise that many straight men lack close and emotionally supportive relationships if, due to homophobia, they must restrict their emotional closeness with other men, and due to monogamy norms, they must restrict their emotional closeness with women.

The Appeal to Sexual Intimacy

Philosopher Kyle York defends monogamy by arguing that people “make more effort sexually with each other and/or feel more relaxed and confident knowing they are not being compared to others” (York 2020: 551), and that this, in turn, enhances sexual intimacy.

It might well be that, for some, acting monogamously enhances sexual intimacy, and in that case, they could have a good reason to act monogamously. The only thing RA objects to, in this respect, is imposing a requirement that the other also acts monogamously, with an explicit or implicit threat of ending the relationship if they fail to comply. In response, it might be said that it also matters for sexual intimacy in a relationship that one’s partner does not, as it were, “use up” their desire for sex by engaging sexually with other people. Here the RA rejoinder is a bit more complex. On the one hand, it is not wrong to place a high value on regular and good-quality sexual intimacy with a partner, and to be much less interested in continuing a relationship if one’s partner has very little sexual interest “leftover” when they are at home. In that case, however, the issue is still what one is doing together with one’s partner. It might be that the partner, in order to meet what one values in the relationship, would decide to have fewer, or even no, sexual encounters with others. There is no way around the fact that time and energy are limited resources (even though love is not!). To be concerned with the content of one’s relationship to one’s partner—which, in turn, may well be influenced by how one’s partner chooses to spend time with others—is unobjectionable.

RA also rejects the premise that one can reasonably demand to have one’s sexual needs satisfied by one partner alone. Although it is understandable why such a premise would be accepted by many given the prevalence of monogamy norms, from an RA perspective, this is as unreasonable as demanding that all of one’s other needs be met by one’s partner alone, and not through, say, friendships with others. Such a demand in the realm of sexual satisfaction can have very negative effects for monogamous relationships within which there is a significant asymmetry in libido between the partners, or where one partner (due, e.g., to anxiety, depression, a somatic condition, medications) loses their libido completely for an extended amount of time. In that case, monogamy norms leave open only two solutions short of ending the relationship: either the party without libido must have sex that they do not want, or the other party must restrict their sex life to masturbation, and thus remain celibate even if they value sexual intimacy highly. Here monogamy norms constitute a threat to good sexual intimacy.

Another way in which monogamy is a threat to sexual intimacy is that it discourages the parties from communicating honestly with each other about the kinds of sexual intimacy that they want. To illustrate this, let’s say that one of the parties in a monogamous relationship is interested in doing something in the realm of kink (see Garcia, this volume). Should they tell their partner? One possibility is that their partner has a compatible kinky interest, and in that case, telling them would be likely to have a good outcome. There is also, however, the very real possibility that their partner does not have a compatible kinky interest.

Recall Kukla’s warning: to let someone know that one is interested in doing something is not to share neutral information, but rather is to say that one desires that it happens. In the context of a monogamous relationship, to share an interest in a kink is, whether one intends it or not, to communicate that either we do this together or you make the choice that my desire for this type of sexual intimacy will remain unfulfilled. This puts the other in a difficult situation. Insofar as one does not want to put one’s partner in such a difficult situation, one is discouraged from honest communication. Notice, moreover, that in case you have told your partner about your kink, and they do this type of kinky activity with you once in a while, it is very difficult to know whether they also like it or if they do it in order to keep you satisfied. They are most likely keenly aware of the fact that you would be much happier if they also liked it than if they did it just went along with it in order to satisfy you. They might predict, correctly, that learning the latter would make you feel miserable. Insofar as they want you to be satisfied, they are discouraged from honest communication, and indeed, have an incentive to pretend that they like it and to fake their sexual responses.

In a relationship that is not governed by monogamy norms, one puts very little or no burden on one’s partner by telling them about one’s sexual interests, since in case it is not a match, one can pursue that sexual interest with others. For the same reason, they can also be much more open in their sexual communication in return.

The Appeal to Stability

Another argument is that monogamy is needed for the sake of stability. York writes that, while this might not need to be the case with sexual encounters that do not involve much emotional intimacy, “what starts as a casual sexual relationship can easily become something more significant, so exclusivity agreements may be needed as a safeguard” (York 2020: 542). Moreover, York maintains, monogamy can help one trust that one’s partner will not be “trading up” if the opportunity arises (i.e., finding that they prefer to be with someone else, and so choosing to leave one in favor of the other person), which makes “our life together … contingent upon the fact that I don’t find someone who’s a better fit for me” (York 2020: 547).

Although this argument is presented, by York, as an argument in favor of monogamy norms, it is unclear to us how it can be an argument in favor of contemporary monogamy norms, which allow for the possibility of ending a relationship and starting a new one. If anything, York’s argument is an argument against accepting and/or allowing divorce. Notice, also, that monogamy norms greatly increase the extent to which other people pose a threat to an existing relationship. Given monogamy norms, one’s partner can only have one sexual and/or romantic partner. This implies that any intimate pursuit, affair, or infatuation that one’s partner might have with another is made into a threat. It’s them or it’s you, and if it’s them, you lose the relationship to your partner in its entirety.

Since we know that infatuations abound, monogamy norms, rather than making relationships stable, make relationships fragile. This fragility, moreover, affects not just the parties in the relationship but also affects children. Children growing up in strictly monogamous nuclear families have a primary support environment that is at a high risk of being shattered if either parent is sexually intimate, even once, with someone besides the other partner.

On the needless frailty of monogamous relationships, philosopher Bertrand Russell held views that make it tempting, retrospectively, to consider Russell a relationship anarchist. Russell writes that extra-marital sex is misjudged “by conventional morals, which assume, in monogamous countries, that attraction to one person cannot co-exist with a serious affection for another. Everybody knows that this is untrue, yet every-body is liable, under the influence of jealousy, to fall back upon this untrue theory, and make mountains out of molehills.” Sex outside of marriage, Russell continues uncompromisingly, “ought to form no barrier whatever to subsequent happiness, and in fact, it does not, where the husband and wife do not consider it necessary to indulge in melodramatic orgies of jealousy” (Russell 1929: 231).

An interesting term in this context, which highlights the fragility created by monogamy norms, is “homewrecker.” The term is used to refer to a person who is sexually intimate with someone who is already in an established relationship. Used this way, however, the term is arguably misplaced, because to be sexually intimate with a consenting adult is not, by itself, enough to wreck a home. Instead, the more directly relevant referent of the term “homewrecker” is the person who—upon discovering that their partner has been intimate with someone other than oneself—responds by wrecking the home.

That being said, we concede that insofar as the term “homewrecker” assigns moral responsibility for the home being wrecked, the referent could rightfully be a person who has required that their relationship should be monogamous, yet fails to live up to their own requirement. In that case, however, they are responsible for the relationship ending in virtue of being hypocritical and manipulative, not in virtue of being intimate with someone other than their partner.

4. Relationship Anarchy vs. Polyamory

So much for our discussion of monogamy. What about polyamory, that is, the practice of engaging in emotionally and/or sexually intimate relationships with more than one person simultaneously? RA stands firmly on the side of defenders of polyamory in challenging the premise that a romantic relationship must, or should, be mutually exclusive to two persons. From an RA perspective, although such twosomeness might be suitable for some, there is no reason to hold this as a norm to which anyone, much less everyone, should strive to comply. There is also reason to be critical of the form that such twosomeness tends to take today, namely within the context, or contributing to the creation, of a nuclear family.

Although the nuclear family might work for some, it is important to keep in mind—so as to get a balanced view on what is truly traditional and what is a modern experiment—that the nuclear family became the dominant social unit only around the time of the industrial revolution, that is, 150–200 years ago. Throughout the vast majority of the human past, most of us have lived in larger households and on farms, and before that in tribes, where child-rearing was an activity in which a larger number of adults took part (for an overview, see Brooks 2020).

The nuclear family is a risky enterprise. In addition to the risks caused by monogamy norms, which we considered in the previous section, the nuclear family—even apart from monogamy norms—creates significant risks. It is risky to distribute virtually all of the parenting of a child on two adults, especially if both have to work full-time jobs, which is often necessary to finance a separate household for two adults and their children. The nuclear family is also vulnerable to the risk of being reduced to a household in which one adult alone must be able to take care of most or all of the primary parenting responsibilities. As Luke Brunning points out, a household with multiple adults

is more resistant to external shocks, such as illness, breakups, changes in income, and the general mutability inherent in all relationships; both in terms of its form, because one has multiple partners for support, and in terms of its content, as emotional work helps one confront change. (Brunning 2018)

The nuclear family also comes with a significant downside in old age, namely that when one party dies, the remaining party is often left in isolation.

Although relationship anarchists therefore have reasons to be supportive of polyamory, RA is not compatible with all polyamorous practices. One of these, like the monogamous exclusivity requirements as we have already discussed, is polyamorous exclusivity requirements. Indeed, it was in opposition to this practice in the polyamory community that RA was developed in the first place. Nordgren writes:

Polyamory seemed, at least to us [in the early 2000s], the very key which could open the cage door – but we soon found that this movement similarly caged loved in, only finding room for more than two people inside. The rules sometimes seemed even stricter within the polyamorous relationships, where love was somehow both special and dangerous. Those who entered the cage willingly would both be subject to control by the other(s), as well as be forced to exercise control over the other(s) behaviour. Our anarchist principles would tolerate no such cage, or wish to put any other person, especially those for whom we felt love, into such a cage. (Nordgren 2018: 75)

One polyamory practice which is opposed by RA is so-called “polyfidelity,” a common definition of which is: “a group of people who are romantically or sexually involved with one another, but whose agreements do not permit them to seek additional partners, at least without the approval and consent of everyone in the group” (Veaux and Rickert 2014: 457).

Although every member of a polycule (as it is often called) should be free to limit their sexual intimacy to the other members of the polycule, it is not compatible with RA that some require that others do so, for the same reasons that RA is opposed to such requirements in the case of monogamous relationships. RA activist Mae Bee has introduced the useful term “rule relationships” to refer to relationships, whether mono or poly, where people make rules about the content of relationships of which they are not themselves part (Bee 2004). Relationship anarchists reject all rule relationships. Mae Bee writes that “in a free society we will not be asking for the consent of one person to sleep with another anymore than we would ask a father for the ‘right’ to marry his daughter” (Bee 2004).

“Relationship anarchy isn’t a catch-all,” writes another RA activist, going by the name of Unquiet Pirate. Rather, they write, RA is

a specific philosophy of intimacy. An important aspect of that philosophy – one I think poly or ‘post-poly’ folks tend to find discomfiting or simply ignore – is that Relationship Anarchy rejects all arguments for policing the behavior of one’s intimate partners [and all] participation in policing the rules/agreements/contracts of other peoples’ relationships. … As a relationship anarchist, I very well might steal your partner, because I believe the idea partners can be ‘stolen’ is not only nonsense, but oppressive nonsense. (Unquiet Pirate 2015)

For similar reasons, RA is also critical of the practice in some poly communities to rank relationships as “primary” or “secondary” relationships. Nordgren writes: “Don’t rank and compare people and relationships – cherish the individual and your connection to them. One person in your life does not need to be named primary for the relationship to be real. Each relationship is independent” (Nordgren 2006). The crux is that although you might clearly cohabit with one partner, but not with another, and might spend more time with one partner than with another, each relationship is unique. Even though it is necessary to prioritize, RA is not compatible with making a cross-situation and cross-purpose hierarchy of people with whom one is intimately involved.

Finally, we want to suggest that relationship anarchists should be critical of the increasingly common practice, among defenders of polyamory, of describing their practice as “consensual non-monogamy” (e.g., Brunning 2018). The point of this description is that everyone in the relationship consents to the other(s) having additional sexual partners. While this may sound agreeable in the abstract, notice how the term “consensual” is used.

In most discussions about consent in sexual relations, we are interested in the consent of the parties that are having sex. In the phrase “consensual non-monogamy,” however, the “consensual” does not refer to the consent of the people having sex (if it did, the phrase would be distinguishing between rape and non-rape). “Consensual” refers, instead, to a third party’s consent. And yet, although this third party is not the one from whom consent is needed, the phrase makes it seem that way. Even those who favor polyfidelity should be in favor of keeping separate the notions of consent from those engaging in sex and so-called “consent” to such sex given by a third party, and they should oppose a practice that renders such a morally crucial distinction in any way ambiguous. Yet that is what happens to the consensual/non-consensual distinction when it is not clear whether the use of the term refers to the consent of the people having sex or to the “consent” of a third party.

5. Conclusion

RA urges us to customize our relationships: We should reject default package-deals and category-based relationship norms, and instead search for ways to realize to the fullest the potential of each unique relationship. At the same time, RA calls for us to refrain from customizing the relationships of others: We should give the people we care about breathing space to make their own decisions, and not threaten to withdraw love and support unless they let us make rules for their relationships to others.

RA makes normative claims, that is, claims about what it is acceptable, and what it is not acceptable, to do. RA is certainly not the view that anything goes. That would be relationship nihilism. Moreover, RA is also not the view that anything as long as the parties have given their consent. That would be relationship libertarianism.

From where does RA get its normative force? As we indicated above, RA can be justified within many different normative frameworks.

Within a consequentialist framework, RA would be justified, ultimately, by appealing to its capacity to bring about greater well-being than traditional models: for example, by rejecting category-based norms as applied to specific relationships within which adherence to those norms would not, in fact, be best for the particular people involved; and more generally, by promoting goods such as fun, intimacy, variety, and freedom, and by counteracting abusive dynamics, jealousy, and families being broken apart for no good reason.

On a consequentialist view, however, the principles of RA wouldn’t be absolute principles; they would be, in keeping with all consequentialist theories, means rather than ends in themselves. Thus, for example, a consequentialist RA perspective would hold that there are strong reasons for general social disapproval of monogamy requirements because these requirements are harmful in most cases. However, such a perspective would not rule out the possibility that there could be cases where such requirements would not cause (net) harm; for example, due to a lasting power-symmetry between the partners and a mutual propensity toward monogamy. In such cases, though, the consequentialist relationship anarchist could argue that monogamy requirements cause no harm because they make virtually no difference—and then they are also not needed.

What about a deontological ethical framework as a normative basis for RA? Here, the principles of RA would be worth upholding not merely as means. Deontological theories hold that certain kinds of actions and ways of respecting others are good in and of themselves, irrespective of the consequences in particular cases. Attaching RA to current discussions within deontology, RA seems to be compatible with David Velleman’s suggestion that we should value others as “self-existent ends,” a central aspect of which is that we should “value them as they already are” and to approach them with “reverence, an attitude that stands back in appreciation of the rational creature [they are], without inclining toward any particular results to be produced” (Velleman 1999: 358). Thus, for example, we should respect our partners’ autonomy, and support what is conducive to their flourishing—even if this involves sexual intimacy with others—without trying to control them as a way of getting certain “benefits” for ourselves in return.

Finally, within a virtue ethics framework, the normative force of RA would be justified, ultimately, by how the actions recommended by RA manifest various virtues such as integrity, honesty, courage, and tolerance, while helping us guard against such vices as cowardice, envy, and possessiveness.

RA, being a normative theory, places certain requirements on us. We should oppose anti-queer attitudes and object when, for example, jealousy is held up as a sign of true love, and say that it is more often a sign of entitlement and possessiveness. We should make it clear to our partner(s), if only unilaterally, that they can rest assured that we will not end the relationship simply because they are intimate with others.

We should also, as relationship anarchists, make sure to pass on healthy RA values to the next generation. We should encourage our children to see their peers as unique individuals; and to dare to ask, invite, and suggest ways a relationship might go, while at the same time taking care to reassure others that it is perfectly fine to say “no.” We should also help foster in children the ability to set boundaries for what others may be allowed to decide. A child should have the confidence, if someone at school says that they can be their friend—but only on the condition that they drop another friend—to answer firmly that while they appreciate the invitation to get to know them better, their existing friendship with the other child is not up for bargaining.

References

Bakunin, Mikhail (1866). “Revolutionary Catechism” in Bakunin on Anarchy. Trans. and ed. by Sam Dolgoff. New York: Vintage Books, 1971.

Bee, Mae (2004). “A Green Anarchist Project for Love and Freedom.” https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/mae-bee-a-green-anarchist-project-on-freedom-and-love (accessed: 2021.08.02)

Brooks, David (2020). “The Nuclear Family Was a Mistake,” The Atlantic, March 2020 Issue. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/03/the-nuclear-family-was-a-mistake/605536/

Brunning, Luke (2018). “The Distinctiveness of Polyamory,” Journal of Applied Philosophy 35 (3): 513–531

——— (2020). “Compersion: An Alternative to Jealousy?” Journal of the American Philosophical Association 6(2): 225–245.

Chalmers, Harry (2019). “Is Monogamy Morally Permissible?” Journal of Value Inquiry 53: 225–241.

Gahran, Amy (2017). Stepping Off the Relationship Escalator: Uncommon Love and Live. Boulder, CO: Off the Escalator Enterprises LLC.

Godwin, William (1793). Enquiry Concerning Political Justice and its Influence on Morals and Happiness. London: G. G. & J. Robinson.

Goldman, Emma (1910). Anarchism and Other Essays. New York: Mother Earth Publishing.

Kukla, Quill (2018). “That’s What She Said: The Language of Sexual Negotiation.” Ethics 129: 70–97.

Kukla, Q. R., and C. Herbert (2018). “Moral Ecologies and the Harms of Sexual Violation.” Philosophical Topics 46(2): 247–268.

Miller, David (1984). Anarchism. London: J. M. Dent.

Nordgren, Andie (2006). “A Short Instructional Manifesto for Relationship Anarchy.” https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/andie-nordgren-the-short-instructional-manifesto-for-relationship-anarchy (accessed: 2021.09.02)

——— (2018). “The Road to Relationship Anarchy.” Melk #6.

Russell, Bertrand (1929). Marriage and Morals. New York: Liveright publishing.

Scruton, Roger (1986/2001). Sexual Desire: A Philosophical Investigation. London: Phoenix Press.

Sousa, Ronald de (2017). “Love, Jealousy, and Compersion.” The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of Love. Christopher Grau and Aaron Smuts (eds). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Unquiet Pirate (2015). “Relationship Anarchy is Not Post-Polyamory” https://unquietpirate.wordpress.com/2015/11/03/relationship-anarchy-is-not-post-polyamory/ (accessed: 2021.08.30)

Veaux, Franklin and Eve Rickert (2014). More Than Two: A Practical Guide to Polyamory. Portland, OR: Thorntree Press.

Velleman, David (1999). “Love as a Moral Emotion.” Ethics 109: 338–374.

Waltzer, Michael (1983). The Spheres of Justice. New York: Basic Books.

York, Kyle (2020). “Why Monogamy is Morally Permissible: A Defense of Some Common Justifications for Monogamy.” The Journal of Value Inquiry 54: 539–552.