Peaceful Revolutionary

Andor The Anarchist

Star Wars’ Radical Anarchists & Rebels

May 4, 2024

The Star Wars — Vietnam connection

The Origins Of Nemik’s Manifesto

Absolute Power, The Book Of Sith

Star Wars Radical Origins

The Star Wars — Vietnam connection

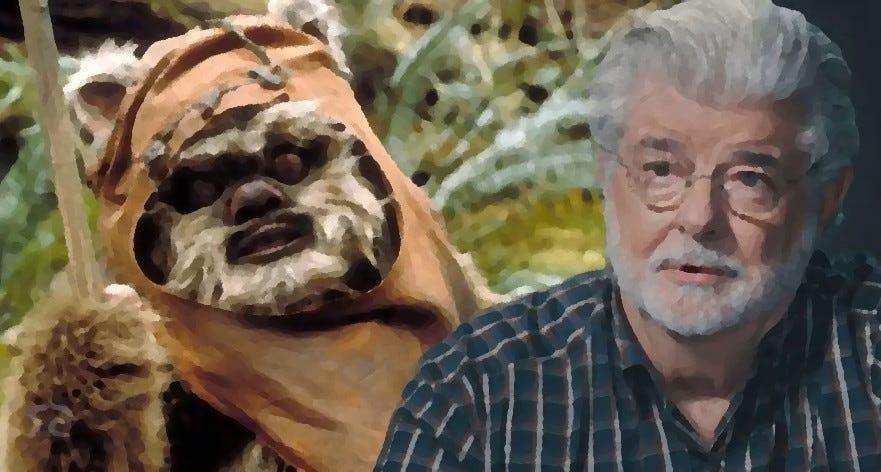

Not so long ago in our little corner of the galaxy not so far away, a film director named George Lucas wrote a screenplay titled Star Wars and changed movie history forever. It spawned sequels, prequel, side-quels and became the one of the most successful franchises of all time.[1]

But this wasn’t just a simple story of a whiny moisture farmer who got caught up in a galactic rebellion against an evil empire ran by his deadbeat dad[2], it was an allegory for the Vietnam war, with Nixon leading the bad guys, and Luke on the side of the Viet Cong.[3] It used the imagery associated with the Nazis to represent the Empire’s soldiers, and based the rebellion’s noble Jedi order on ancient Chivalric knights.

The connection between Star Wars and the Vietnam war may sound far-fetched, but we have a very reliable source for it.[4] In 2005, Lucas articulated that Star Wars ‘was truly about the Vietnam War, and that was the era when Richard Nixon was seeking re-election for a second term, which prompted me to ponder historically about the process of democracies transitioning into dictatorships. Because democracies aren’t forcibly overthrown; they are willingly relinquished.’[5] And just in case someone suspects this was a later reinterpretation there is support for this view in the 1973 draft for the film, where Lucas explicitly referenced an autonomous planet likened to North Vietnam, and portrayed the Empire as ‘America 10 years from now.’[6]

Star Wars Rogue One

Star Wars in all of it’s manifestations has been about rebellion against an empire (even when it featured cuddly Ewoks). In the first of the Star Wars trilogy[7] the rebellion has got their hands on some plans to the evil empire’s combo mega-weapon and shopping mall: the Death Star.[8]

They are told that getting hold of these plans came at a great human cost, but the full story of their sacrifice came a few decades later in the form of the film, Rogue One, which revealed the previously unsung and uncredited heroes and told tragic their tale.[9]

With this new prologue in the Star Wars canon we are introduced to Rebel Alliance intelligence officer Cassian Jeron Andor, who, along with Jyn Erso, the daughter of the DeathStar designer, obtained the legendary plans that would one day free the tyranny of the empire (for a little while anyway, until they built another Deathstar).

However, the CEO of Disney downplayed any comparisons between the film and the Make-America-Great-Again crowd, telling the Hollywood Reporter that this film about freedom fighters bringing down fascism wasn’t ‘in any way, a political film. There are no political statements in it, at all.’[10] This was a message the co-writer, Chris Weitz, didn’t seem to get when he tweeted that ‘the Empire is a white supremacist (human) organisation.’ a tweet he was made to delete shortly afterwards.[11]

Maybe it’s me, but opposing state approved oppression does seems to me to be a political act. Perhaps not necessarily a party-political act, maybe not even an act necessarily grounded in a complex ideology. But the idea that people should be free and not silently compliantly submit to state oppression is an idealogical belief, and one often tied closely to someone’s political views.

Andor The Series

As for the character of Andor, however, we aren’t given much of an insight into his political views or how Andor became part of the rebellion in Rogue One. Yet he proved to be such an interesting character[12] that the movie making gods of the Star Wars extended universe decided to tell his tale in a serialised television form, and this is where we find a more jaded (and selfish) Cassian unexpectedly acting as mercenary for the rebellion, and follow his journey each week on Disney Plus to him becoming a fully committed (and ultimately self-sacrificing) rebel.

This tale is told by the talented Tony Gilroy, who had previously been hired by Lucas to rewrite portions of Rogue One, and returned as the show-runner of Andor, with help from his brother Dan.[13] Tony was previously best known for his remake of the Bourne trilogy[14] and was a best director academy winner for his film Michael Clayton. His brother Dan, also Academy nominated for his Nightcrawler screenplay. Dan’s twin brother, John, also did the editing on three of the episodes of Andor.[15]

Although many of their past screenplays deal with different political issues, it seems they usually shy away from sharing their personal political views in interviews.[16] This does not mean however that they are averse to admitting — like George Lucas before them — that they were inspired by particular political figures.

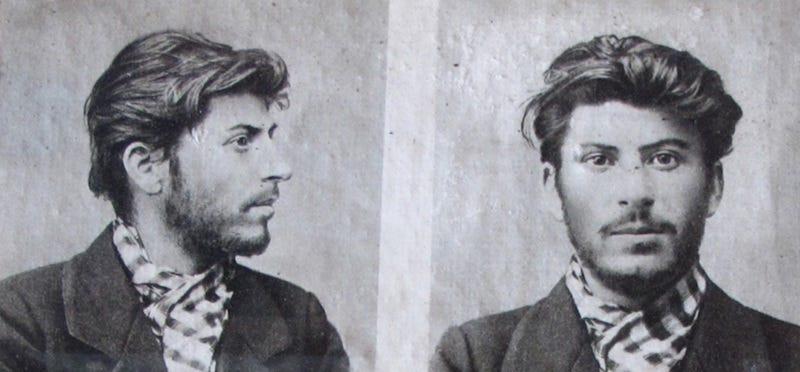

Young Stalin

Cassian Andor begins his television show, set five years before the events of the film, as a smuggler and reluctant hired mercenary for the rebellion. There is no shortage of historical and fictional rebels that the writer of the series could have based the character on, but Tony revealed that he had a particular controversial character in mind, when he found inspiration in the book ‘Young Stalin’ by Simon Sebag Montefiore:[17]

‘The opening chapter is [like] this incredible movie sequence where Stalin is part of staging a major bank robbery in a Georgian town in 1907. It involves 15 people and hookers and teamsters and all these things. Stalin was Lenin’s financier. He was a thief. And the reason Lenin loved him so much was he kept bringing the money. They needed money. This shit all costs money. People gotta eat, they gotta get guns.’[18]

However, there are fundamental differences between the direction Stalin’s life took and the one Andor takes. Stalin ultimately believed that the evil empire he fought against should be replaced with another empire he was the head of, but Andor never sought such a role or power over others at all.

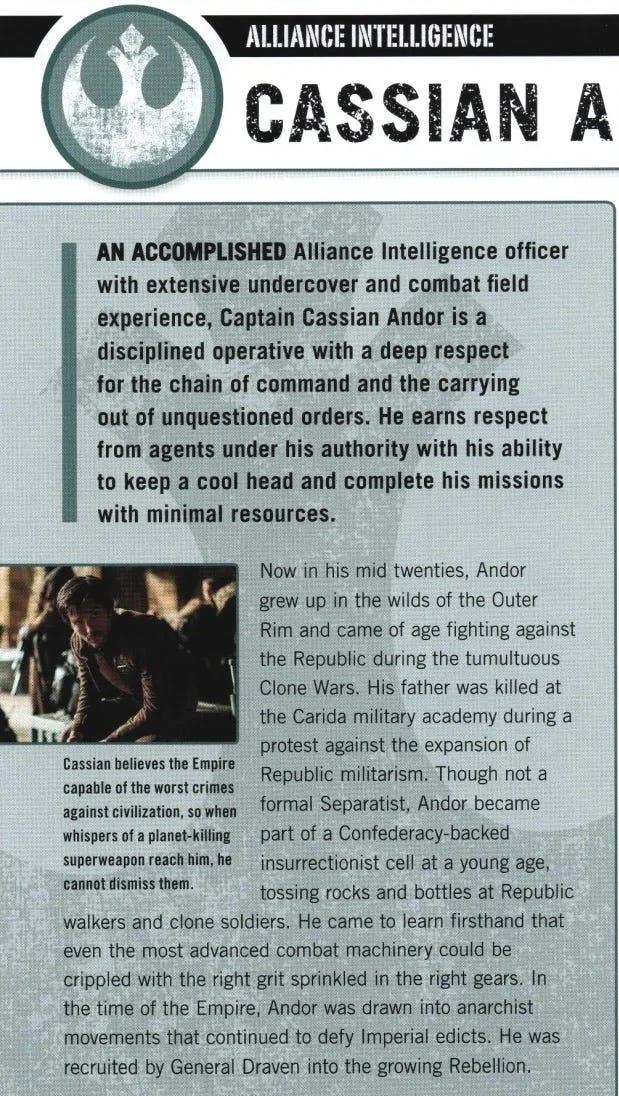

So that precludes Andor from being a Marxist-Leninist like Stalin was. If we want to find out what political ideology Andor did adhere too we have no better place to look than the official, Star Wars Rogue One Visual Dictionary:

‘Now in his mid twenties, Andor grew up in the wilds of the Outer Rim and came of age fighting against the Republic during the tumultuous Clone Wars. His father was killed at the Carida military academy during a protest against the expansion of Republic militarism. Though not a formal Separatist, Andor became part of a Confederacy-backed insurrectionist cell at a young age, tossing rocks and bottles at Republic walkers and clone soldiers. He came to learn firsthand that even the most advanced combat machinery could be crippled with the right grit sprinkled in the right gears. In the time of the Empire, Andor was drawn into anarchist movements that continued to defy Imperial edicts.’[19]

Andor The Anarchist

Andor is an insurrectionary Anarchist! The Anarchists in Star Wars were part of stateless coalition of rebel dissidents. Some rebels aligned with governments and represented particular sectors of the galaxy, but others, Anarchists such as Andor, rejected the concept of hierarchy and states altogether, just as modern Earthly Anarchists do. The word Anarchist literally meaning ‘anti-hierarchy’.

Anarchists also had a major part in the early days of the 1905 Russian revolution, as they had a common enemy in the form of the Tsar, and were often part of the Soviet councils, until Stalin disbanded the co-operative system and opposed the Anarchists.[20]

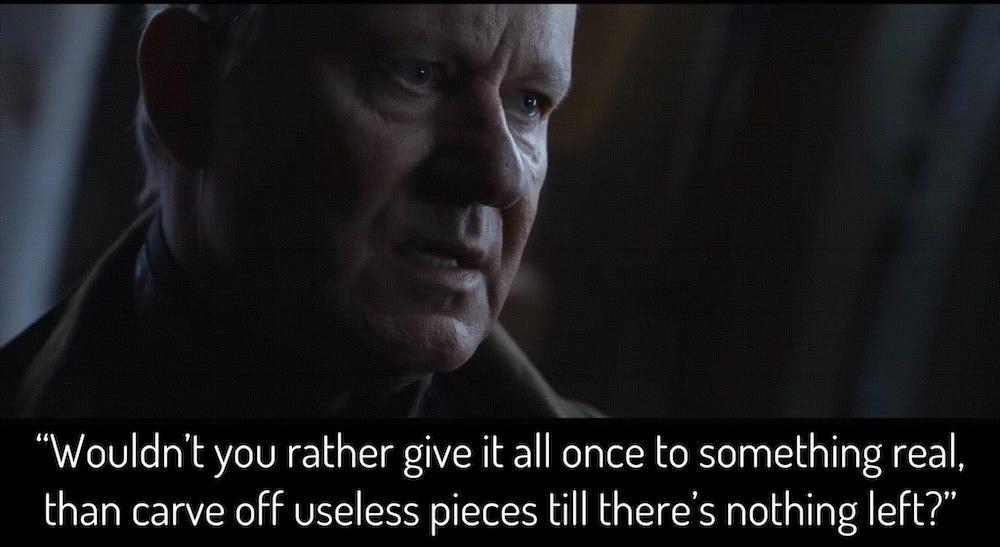

However, Andor almost didn’t get involved in the rebellion at all. Seeing the cost it had exacted on his family already he wasn’t eager to suffer as they had. Yet Luthen Rael, leader of the rebel spy network sees Andor’s potential and when recruiting him challenges him to commit to the cause, ‘Wouldn’t you rather give it all at once to something real than carve off useless pieces till there’s nothing left?’[21]

He isn’t entirely convinced at this point, but as his relationship with the empire and rebellion becomes more personal so do his views and involvement, until he becomes fully committed to the rebels aims himself.

Cassian Andor is played by Diego Luna in both the film and television series, and unlike some of the writers hasn’t shied away from admitting to the political nature of the show’s themes, insisting there wouldn’t be a series at all without them, and that the themes are still relevant to us now: ‘We’re telling the story of the awakening of a revolution. There’s no way not to be political. If you wanted to avoid it, there wouldn’t be a show. Clearly, the show talks about oppression. The show talks about the context needed for a revolution to be born. That is always going to resonate because the need for change is constant for humanity.... For me, this story is saying a lot of what worries me and what I care about.’[22]

But how does a smuggler become an Anarchist? What influenced him to go from avoiding conflict to confronting and facing it? Was there anything in particular that inspired his beliefs and actions? This question is answered — at least in part — through the influence of a young freedom fighter by the name of Karis Nemik.

In the next article I will look into Karis Nemik’s influence on Andor and why (I believe) he taught an Anarchist view of politics and revolution, and later who his character may have been inspired by.

In the last article, we explored how Star Wars was originally inspired by the pro-Communist Viet-Cong’s fight against the Capitalist American Empire, and how its prequel Rogue One, featured a major Anarchist character, Cassian Jeron Andor.

Andor’s Political Inspiration

Karis Nemik’s Ideals

In the last article, we explored how Star Wars was originally inspired by the pro-Communist Viet-Cong’s fight against the Capitalist American Empire, and how its prequel Rogue One, featured a major Anarchist character, Cassian Jeron Andor.[23]

From the first to the third episodes of the Andor streaming series, Cassian is avoiding both the Empire and the Rebellion. He doesn’t want the trouble that comes with the former or the idealism (and subsequent trouble) that comes with the latter. Although his adoptive mother has a more radical involvement in their community, he stays away from such distractions. His friend maintains contact with the Rebellion, but Cassian is happy to be kept out of it until he needs their help – and they also need his.

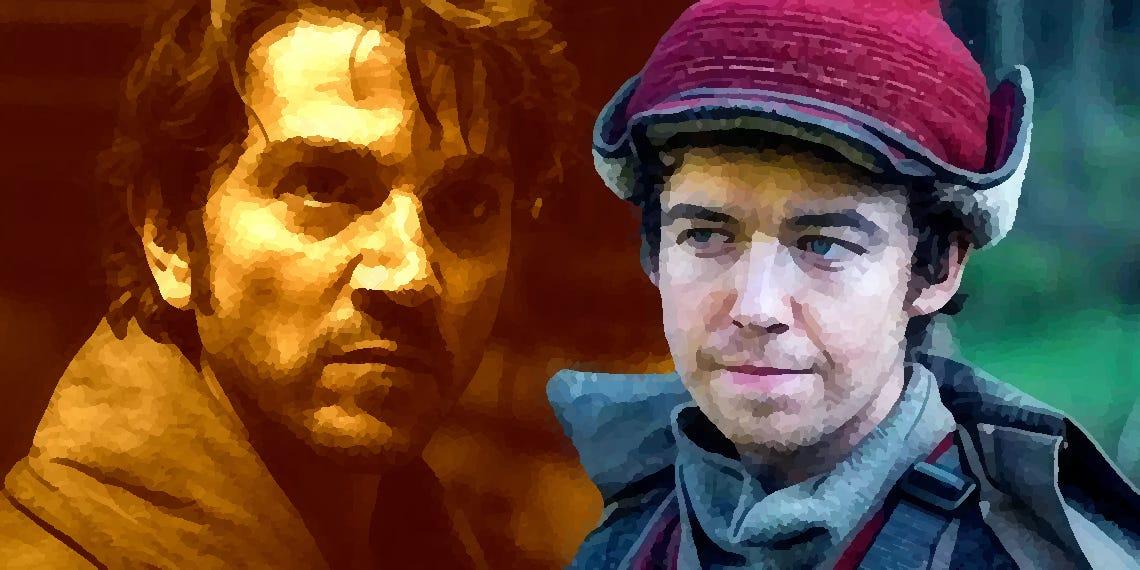

This is how Cassian finds himself as a paid mercenary, on the planet of Aldhani as part of a robbery intended to deal an economic blow to the Empire.[24] It is here, in the fourth episode, named for the planet on which it takes place, where he meets young idealist Karis Nemik, portrayed by Alex Lawther.

Lawther, who plays Karis, like his Star Wars character, is not shy about sharing his own ideals. In 2023, he joined more than 1,000 artists in the British film industry in signing an open letter demanding a permanent ceasefire in Gaza, and has also been involved in climate activism with Extinction Rebellion.[25]

Aldhani

We first see Nemik asleep, while he is supposed to be on watch, his rifle resting on his lap. A blaster is brought to his face by his fellow insurgent, Arvel Skeen, to awaken him and remind him of how easily he could have been taken by surprise by an enemy. He apologises for his lapse of concentration, and picks up the binoculars through which he was supposed to be keeping a watchful eye, and for the first time sees Cassian in the distance with his team leader, Vel Sartha, but at this point he has no idea who this stranger is.

The next time we see Nemik he is being introduced to Cassian (under the moniker of Clem), who Nemik welcomes wholeheartedly: ‘Good to have you, Clem. We’ll take all the help we can get.’[26]

The rest of the team, however, are more reticent than him, and not all of them are convinced by Cassian’s convictions, as we discover when they get a moment to discuss his unexpected arrival in private:

Gorn: ‘How do you know him?’

Vel: ‘He comes highly recommended.’

Skeen: ‘So you don’t know him.’

Vel: ‘I know that we need him. That’s all I’ll say. Anything else is a violation of security.’

Gorn: ‘No, he’s got brass. You… You can feel it. And we can use a hand, but this late in the game?’

Vel: ‘As opposed to when?’

Skeen: ‘You trust him with our lives?’

Vel: ‘That’s my call to make.’

Nemik: ‘He’s committed. I’m feeling that. I want to.’

Skeen: ‘Feel what?’

Nemik: ‘His belief in the cause. When it comes down to it, that’s all I need to know.’

Nemik seems to be making quite an assumption at this point, but he knows that the odds are already against them completing the mission, that it could cost them their lives, and that another hand could help give them a greater chance of success and make the difference. I think this scene also shows that Nemik isn’t interested in Clem (Cassian) meeting some specific ideological purity test, but believes that people are more likely to be trustworthy if you treat them respectfully and place trust in them. After all, Cassian is being expected to trust them too and they’ll have to trust him to succeed in their plans.

Nemik isn’t looking for Cassian to have any party affiliation, or for him to make any ideological oaths, meet any loyalty tests, or to undergo any inductions or initiation rituals. It’s all too late in the plans for any of that anyway. The ‘belief in the cause’ he is interested in is just that the Empire is evil, that they have to be fought against because they are trying to control others, to rule them through fear and violence, and that they should be stopped.

For Nemik this isn’t a hobby, it isn’t party politics, it doesn’t wait upon officials to convene conferences and bring up topics for discussion. He isn’t going to wait to go through legally approved channels for making complaints, and he isn’t putting his faith in waiting for elections to pick political representatives. He knows that such tactics are irrelevant to the Empire, except to show them who to silence.

Cassian has no love for the empire either, as he has been just as hurt by it. He may not be fully committed to the cause as yet, but he and the rebels have overlapping goals even at this point. He has tried to avoid conflict with the Empire to avoid the problems and dangers that come with that, but has still come up against them, and is now on the run from them. At this point Nemik seems to see the potential of Cassian before Cassian does, that he can be an important part of the cause to oppose and defeat the Empire, even if Cassian has yet to realise this.

Later, at a meeting to plan the heist we see that Nemik has made a detailed model of the base they’ll be infiltrating, which they hope will undermine the Empire’s finances and bolster those of the Rebellion, harkening back to the bank robbery Stalin made in 1907 to support the Russian revolution. Although he apologises that his model is ‘obviously it’s not to scale’, and that the ‘rain gets into’ the fragile pieces it is made from.[27] The group runs through the plans together, and it is revealed that they rely on an astronomical anomaly that happens every three years, known locally as the Mak-ani bray Dhani (The Eye of Aldhani), which Nemik describes with some enthusiasm:

‘It’s not really a meteor shower. It’s a recurrent band of crystalized, noctilucent micro densities. Billions of crystals. Very heavy but small and unstable. As the planet passes through the belt, they swarm the atmosphere, heat up, and explode. From the ground, it’s a thing of beauty. In the sky, it’s chaos. We’ve calculated an escape trajectory that gets us out just before the Eye closes. This happens in three days’ time.’

Although Nemik pays special attention to the details, to the scientific side of the phenomena, he also expresses a recognition of its beauty, the wonderful spectacle which will allow them to escape with their stolen cargo if all goes to plan. A plan which Vel gives Cassian one last chance to bail out of: ‘Now, you’ve got a lot to learn and very little time to do it, so what we need to know is, are you in all the way?’ To which he commits with, Let’s get to it.’

The Axe Forgets

In the next episode, ‘The Axe Forgets’ the team is making the last few preparations for their heist.[28] The rebels believe that they have a right to do what they are doing, not just because of the effect it will have on weakening the Empire, but because they believe they are taking back what the Empire has stolen. However, the Empire wouldn’t see it that way.

The Empire makes and enforces the laws in this and on other worlds they ‘colonised’, so they consider that the millions of credits they have taken in resources from the worlds they have colonised are rightfully their property. Of course the inhabitants who have been invaded and conquered don’t see it that way. When a government takes power and steals money or goods it is called taxes (or if they take land it is called Eminent Domain), when an army does it they call it Commandeering or the Spoils of War. Both are seen as legitimate and legal, but when revolutionary rebels do it it is called Expropriation, and is seen as theft.

The question is what entitles a state or corporation (or person for that matter) to have more than they need and what do they intend to use it for? In the case of these payroll credits, the Empire intends to use them to pay its Storm Troopers. Even though Storm Troopers are largely clones at this point, created for the purpose of fighting the Empire’s wars, they do receive pay, time off, and even occasionally retire if they live long enough. An army may run on its stomachs, but it seems that if they have some extra spending money then they are better motivated to do their jobs, even if that is being programmed to kill anyone who stands in the Empire’s way.

So taking that pay away is likely to cause some unhappy less cooperative Storm Troopers, or — if they still get paid from other funds — take money away that was intended for buying the weapons the Empire might have used against the Rebels, who now could buy similar weapons to defeat the Empire with (albeit probably made by the same weapons companies).

However, to carry out this plan will take a great deal of commitment and skill from the small Rebel team. Whereas the team are worried about Cassian’s dedication, Cassian isn’t certain about whether Nemik is strong enough, which he expresses to Arvel Skeen when they have a moment to talk at the rebel camp:

Cassian: ‘It always breaks at the weakest point’

Skeen: ‘Oh, you’re worried about the kids. Nemik’s a surprise. He’s green, but he’s all in. He’s a true believer. Nothing but the cause for him.’

Nemik’s Beliefs

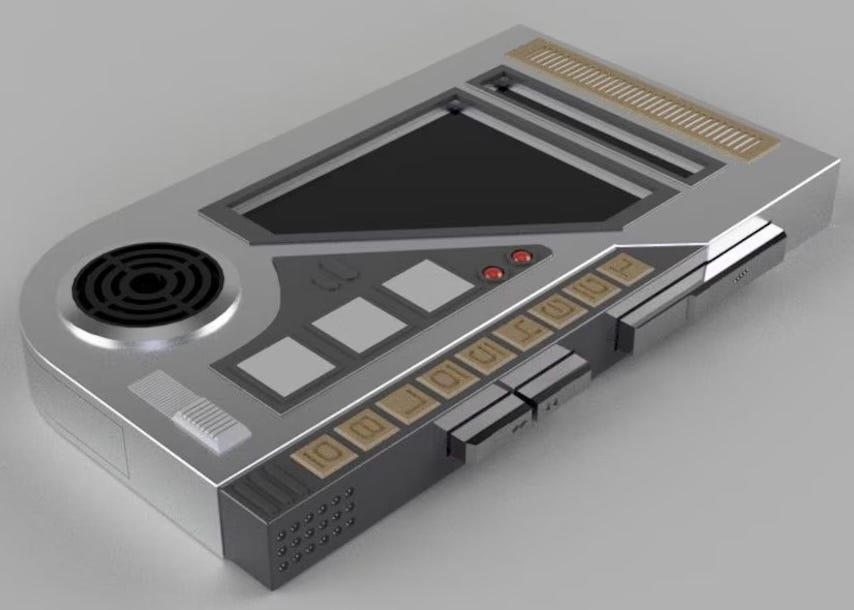

Initially, Nemik is characterised as a true believer in the cause, wholly dedicated to opposing the Empire. However, his belief extends beyond mere ideology; it encompasses a pragmatic understanding of the tools necessary for liberation. As we learn when Cassian comes up to Nemik while he is repairing a navigational tool for him to use:[29]

‘That’s an old one. Old and true. And sturdy. One of the best navigational tools ever built. Can’t be jammed or intercepted. Something breaks, you can fix it yourself. Hard to learn. Yes, but once you’ve mastered it, you’re free.’

Nemik’s emphasis on self-reliance, as demonstrated by his navigational tool, underscores the Anarchist principles of autonomy, decommodification and decentralisation.[30] It is reminiscent of recent court battles in America over the ‘Right To Repair’ the technology you own, against the wishes of corporations who want to force you to use their service programmes or let your old equipment become obsolete by design.[31]

Nemik laments that they have ‘grown reliant on Imperial tech, and we’ve made ourselves vulnerable.’ Just as black feminist and rights activist, Audre Lorde, recognised, that when it came to revolutionary change ‘the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house’. Nemik also speaks of ‘a growing list of things we’ve known and forgotten,’ This is because the Empire’s only free information is its state controlled propaganda.

The Empire’s Imperial Board of Culture categorised artistic works into three tiers based on their perceived alignment with Imperial values:

-

Banned works were considered overtly anti-Imperial and strictly prohibited.

-

Scarlet works were deemed neutral, neither promoting nor disparaging the Empire.

-

Pro-Imperial creations were actively endorsed and disseminated to the public.

Furthermore, the Empire only permitted the production, consumption, and distribution of ‘pure’ artistic expressions (holovids or books) created solely by Humans without any assistance from nonhuman entities.[32]

Then there was deliberate misinformation the Empire used to divert or discourage anyone who might think of rebelling, these were what Nemik called the ‘things they’ve pushed us to forget. Things like freedom.’ However, Skeen thinks Nemik too idealistic, adding that, ‘Nemik sees oppression everywhere.’

Nemik sees oppression everywhere because it is everywhere. The system is oppressive, oppression is woven into its very fabric as is the case with any top-down hierarchical system. It is a coat everyone must wear, whether it fits or not, even if it constricts some and ‘drowns’ others. Someone less concerned with freedom, less impacted by its injustices might adapt to it, even feel comfortable in it, as it inconveniences them less. But Nemik doesn’t just think about and care about himself, he acts out of concern and sympathy for others too.

This longing for fairness and justice is what drives Nemik, not just in action, but to share his thoughts and feelings, as Skeen reveals, ‘He’s writin’ a manifesto. Did he tell you? Apparently, the only thing keepin’ us from liberty is a few more ideas.’

Skeen laughs at this idea. To him it is a joke, like the one in Thor: Ragnarok where the insurgent Korg says he didn’t succeed in his revolution because he ran out of pamphlets. But there are times words — in the form of leaflets or manifestos — can defeat empires. One need only look at the influence of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, Marx’s Communist Manifesto, Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid, or Darwin’s Origin Of The Species, that started revolutions political and scientific that changed the world.[33]

But Nemik carries on despite Skeen’s mocking: ‘It’s so confusing, isn’t it? So much going wrong, so much to say, and all of it happening so quickly. The pace of repression outstrips our ability to understand it. And that is the real trick of the Imperial thought machine. It’s easier to hide behind atrocities than a single incident.’

Yet through this fog of war he sees clarity: ‘But they have a fight on their hands, don’t they? Our elemental rights are such a simple thing to hold, they will have to shake the galaxy hard to loosen our grip.’ In saying this he foretells what the Empire’s reaction will be, and why it will ultimately lose.

Andor Revealed

Although Cassian starts off as Clem, when he joins the team, hiding his role as a paid mercenary, Skeen catches him out and he admits why he really joined them. When this is brought before the team, the rebel Storm Trooper Taramyn Barcona questions Vel Sartha about this, and she tells him that Luthen Rael insisted that she include ‘Clem’ or he would call off the mission. Cassian says that he is only willing to take the risk with the mission because of the money. But he also has his own reasons to hate the empire and to strike a blow against it, even if he doesn’t subscribe to any particular political ideology.

Now Nemik, despite his initial faith in Clem (Cassian), is no longer entirely sure of his intentions, asking ‘I’d like to hear what Clem believes, or is it Andor?’ To which Cassian replies, ‘I know what I’m against. Everything else will have to wait.’

This doesn’t discourage Nemik who tells him, ‘You’re my ideal reader. Haven’t titled [the manifesto] yet. I’ve been waiting. It’s a work in progress, and I know that there’s a great deal left to say.’

He returns to the navigational tool as a symbol of what he believes, ‘I mean, look. Right here. Fresh inspiration. Two seemingly random objects, and yet this charts an astral path, this maps the trail of political consciousness. Both systems based on truth, both navigating toward clear and achievable outcomes.’

Nemik believes there is clarity to be found amid the chaos the Empire produces, that their power, while sometimes seeming overwhelming, can be overcome if people can become conscious of their power and how to use it.

Despite their differences, Nemik remains steadfast in his commitment to the cause, guiding Cassian through the intricacies of resistance. At a site overlooking the Empire’s base they continue their conversation, with Nemik confident the Empire will, ‘soon see, surprise from above is never as shocking as one from below.’

This is an insurrectionary action — they represent the rebellion against the empire, but not in any official capacity. The Empire are the officials they are fighting against. They are the terrorists or freedom fighters depending on which side you are on. This is an act of individuals working together as a small team to strike a substantial blow to the otherwise seemingly unstoppable Empire.

However, Nemik doesn’t hide his disappointment though, when Cassian later admits ‘I’m being paid to be here’, asking him, ‘it’s really only the money?’

To which Cassian replies, ‘To take a risk like this? Come on.’ To this Taramyn accuses him of being afraid, and he retorts, ‘Of course I’m afraid. But there’s a difference between fear and losing your nerve.’

Cassian does keep his nerve, and despite reservations, the rebels proceed, driven by a combination of ideals and necessity, and Cassian comes to ponder Nemik’s words — especially his manifesto — a great deal more through the events that follow.

These episodes featuring Nemik were written by Dan Gilroy, brother of Tony Gilroy. Dan Gilroy also wrote the Academy award nominated screenplay for Nightcrawler, which could be considered a cautionary tale about the risks posed by capitalism, especially where the media and truth are concerned.

In the next article, we’ll witness the culmination of Nemik’s beliefs and their impact on Cassian’s journey. Through Nemik’s words and actions, we’ll gain further insight into the enduring struggle for freedom in the face of tyranny.

Nemik’s Anarchist Manifesto

Nemik’s Anarchism

In the sixth episode of the Andor television series the time for the heist of the Empire base which the Rebel team has been planning has finally come, as the ‘The Eye’ of Aldhani phenomenon they hope to use as cover for their escape is only hours away.[34]

We return to see Cassian Andor sitting outside in the early morning, Karis Nemik brings him a drink, as he couldn’t sleep either. But Nemik is worried that he won’t be at his best when the time comes, to which Cassian assures him that he will do well enough during the mission when the adrenaline rush kicks in. But this doesn’t fully comfort Nemik:

‘I’m struggling to understand why my faith doesn’t calm me. I believe in something. Why am I so unsettled? I mean you have nothing, you sleep like a stone. I write when I can’t sleep. Wrote about you last night. Not you specifically, not “Clem.” Although I’m assuming that’s not your real name, anyway. “The Role of Mercenaries in the Galactic Struggle for Freedom.” My conclusion is simple. Weapons are tools. Those that use them are, by extension, functional assets that we must use to our best advantage. The Empire has no moral boundaries, why should we not take hold of every chance we can? Let them see how an insurgency adapts.’

In saying this, after he has discovered that Cassian (Clem) was hired to help them, he is finding a way to incorporate Cassian (and mercenaries like him who might not have the same ideals) into the revolution, to still see him as an asset, a tool, and a weapon that can be used against the empire, even if their intentions are not the same.

Insurgencies exist when there are no other channels left for the oppressed to fight for their freedom, they work outside of political processes, and do not ask politely for their rights back (this having already proved to be fruitless). To the officials of conquering empires insurgents are terrorists, to the people affected by the empire’s rule they are freedom fighters. They use guerilla warfare, because they are unable to match the empire’s firepower directly, and hope to use ambush, sabotage, and raids to wear down and outlast their enemies.[35] The need for such tactics in that fight is something Cassian agrees with Nemik on, but not without some reservations:

Cassian: Well, you’re half right. The Empire doesn’t play by the rules.

Nemik: And how am I wrong?

Cassian: They don’t care enough to learn. They don’t have to. You mean nothing to them.

Nemik: Perhaps they’ll think differently tomorrow.

Cassian: Be careful what you wish for.

Nemik: So you think it’s hopeless, do you? Freedom? Independence? Justice? We should just submit and be thankful? Just take what we’re given?

Cassian (glaring at Nemik): Do I look thankful to you?

Cassian isn’t convinced by the ultimate success of Nemik’s ideals, but he is more than aware of the cost of the Empire’s beliefs being enforced on the galaxy, as it has come at great personal cost to him and his friends and family.

When it comes to the actual heist not everything goes exactly to plan. The Rebels including Andor, Sartha, and Kaz ambush the Imperial base led by Commandant Beehaz, taking his family hostage to force him to unlock the vault containing the sector’s payroll. After a tense standoff use explosives to access the vault’s cylinders containing the payroll. They load the cylinders onto a freighter amid a firefight where several were killed, including Gorn and Taramyn Barcona. During the ensuing escape through the launch tunnel pursued by TIE fighters, and Nemik was crushed by shifting payroll cylinders and seriously injured, leaving him unable to feel his legs. Despite this, Andor pilots the freighter into the comet-filled sky using instructions from the seriously injured Nemik, escaping the fighters, and successfully fleeing with the payroll.

As part of their contingency plan they had a doctor ready for such an emergency, but despite his best efforts Nemik succumb’s to his injuries. Cassian shows up to discover Nemik dead, and tells Vel Sartha that he has killed Skeen, who was trying to leave with the money, although she isn’t convinced by his story. Before Cassian leaves with his cut, Vel hands him Nemik’s Manifesto, ‘He said to give this to you.’ But Cassian tries to decline it, taking after Vel says, ‘He insisted’, and Cassian heads off with it.

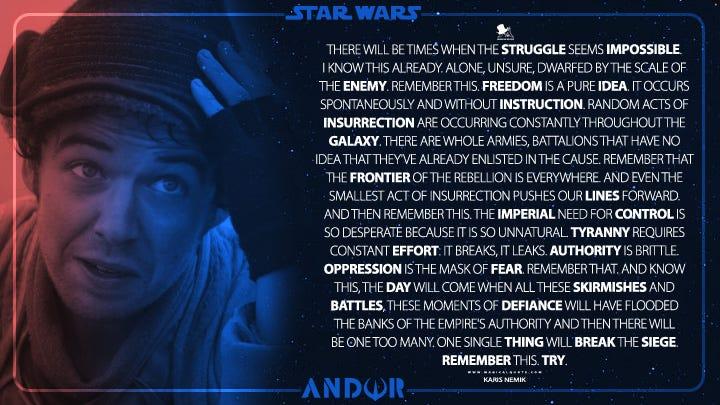

Nemik’s Manifesto

Cassian eventually sought refuge on the planet Niamos, storing Nemik’s manifesto in a box hidden in a hotel room. However, he was soon arrested by the Empire over a minor confrontation and imprisoned. After escaping, Andor returned (in the episode, ‘Daughter Of Ferris’) to Niamos to retrieve the box from the hotel room, where someone else was sleeping. As he checked the box, he opened the manifesto, which began playing Nemik’s recorded content briefly before he closed it to avoid disturbing the sleeper.

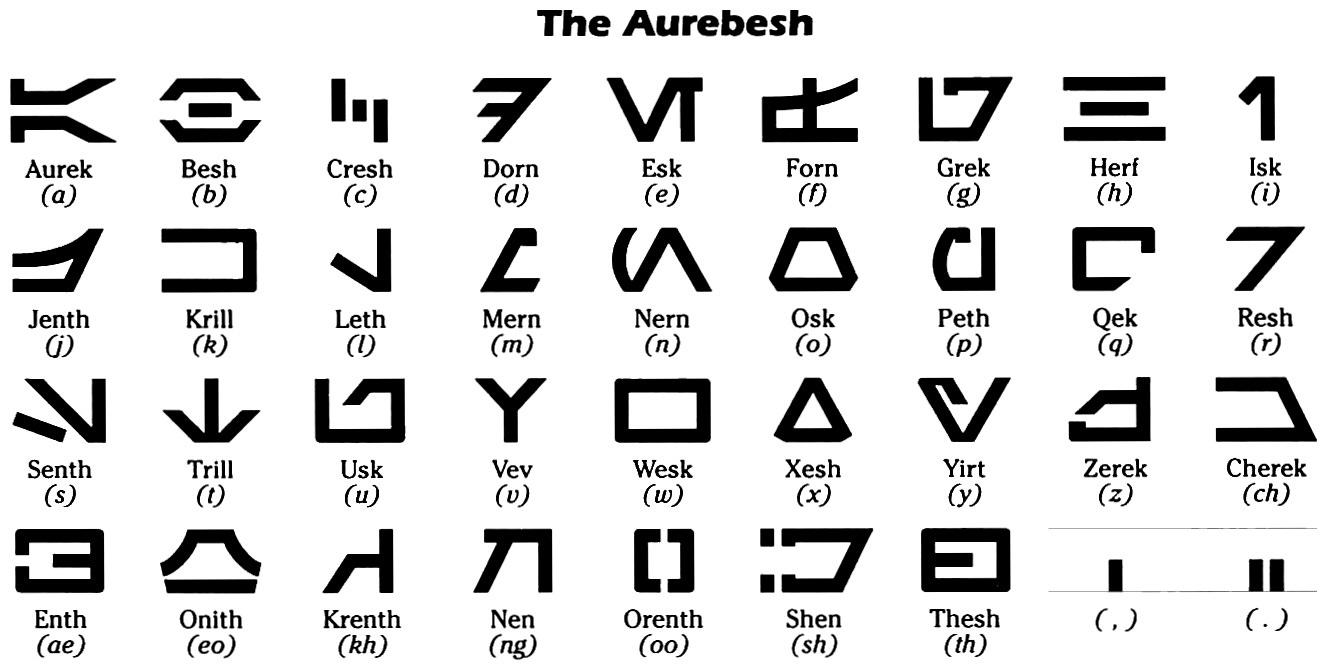

We briefly see the text written upon the datapad too, written in Aurebesh, the 34 letter alphabet of the ‘Galactic Basic’ language which most of the human characters in the Star Wars galaxy speak (rather than the English we hear, although we never get to hear it).[36] However, it is not until the last episode, ‘Rix Road’, that we get to hear a complete passage from it.[37]

We hear Nemik’s words in his voice, reciting the opening of his Manifesto. While we see images of Andor’s friend Bix Caleen in a cell between interrogations, Luthen Rael by himself in the offset of a storm.

‘There will be times when the struggle seems impossible. I know this already. Alone, unsure, dwarfed by the scale of the enemy.

Remember this. Freedom is a pure idea. It occurs spontaneously and without instruction. Random acts of insurrection are occurring constantly throughout the galaxy. There are whole armies, battalions that have no idea that they’ve already enlisted in the cause.’

Then we see Cassian listening to the manifesto on Nemik’s device, having returned to his home planet for the funeral of his mother, Maarva Carassi Andor.

‘Remember that the frontier of the Rebellion is everywhere. And even the smallest act of insurrection pushes our lines forward.

And then remember this: the Imperial need for control is so desperate because it is so unnatural. Tyranny requires constant effort. It breaks, it leaks. Authority is brittle. Oppression is the mask of fear.

Remember that. And know this, the day will come when all these skirmishes and battles, these moments of defiance, will have flooded the banks of the Empire’s authority and then there will be one too many. One single thing will break the siege.

Remember this. Try.’

Nemik’s Manifesto’s title is, ‘The Trail of Political Consciousness’, and what we have heard is just the opening to it.[38] We know it has a section on, ‘the role of mercenaries in the galactic struggle for freedom’ inspired by Cassian, but we can imagine it speaks a great deal about the ideals and methods of the insurgency, in a way intended to inspire others to rebel and instruct them in ways to do so.

The words, ‘Political Consciousness’ used in the title have been associated with Socialist movements since the mid-19th century, with the first using the phrase being, Anarchist Mikhail Bakunin, in his critique of Karl Marx titled, ‘Marxism, Freedom and the State’, written in 1867. But it is five years later before he gives a fuller explanation of the term, when he uses it to specifically speak of Anarchist ideals:

‘Now to discuss the question whether by means of propaganda it is possible to make a people politically conscious for the first time, we must specify what political consciousness is for the masses of the people. I emphasise for the masses of the people. For we know very well that for the privileged classes, political consciousness is nothing but the right of conquest, guaranteed and codified, of the exploiter of the labour of the masses and the right to govern them so as to assure this exploitation. But for the masses, who have been enslaved, governed, and exploited, of what does political consciousness consist? It can be assured by only one thing — the goddess of revolt. This mother of all liberty, the tradition of revolt, is the indispensable historical condition for the realisation of any and all freedoms.

We see then that this phrase political consciousness, throughout the course of historical development, possesses two absolutely different meanings corresponding to two opposing viewpoints. From the viewpoint of the privileged classes, political consciousness means conquest, enslavement, and the indispensable mechanism for this exploitation of the masses: the coextensive organisation of the State. From the viewpoint of the masses, it means the destruction of the State. It means, accordingly, two things that are diametrically and inevitably opposed.’[39]

To put it simply, for the oppressed masses, true ‘political consciousness’ means realising the need to revolt and destroy the state apparatus that enables their exploitation by the ruling classes. For the masses, the ‘tradition of revolt’ against oppression is the essential historical condition for achieving any real freedom and ‘political consciousness’ in the liberating sense.

This fits in perfectly with the preface to Nemik’s Manifesto, wherein he speaks of freedom as something that is naturally occurring ‘spontaneously and without instruction’ in its unsullied ‘pure idea’ form. That when freedom is curtailed ‘acts of insurrection’ occur randomly, even among those who ‘have no idea’ they are already taking part ‘in the cause.’ This is because the yearning for freedom is universal, as is the desire to rebel against whatever restricts it. Insurrections are armed rebellions, not just protests, but include the possibility of meeting the Empire’s violence with violence returned in defence of the freedom of the conquered.

Returning to the Manifesto’s preface second half, Nemik observes that

‘The Imperial need for control is so desperate because it is so unnatural. Tyranny requires constant effort. It breaks, it leaks. Authority is brittle. Oppression is the mask of fear. Remember that.’

Having control over others is unnatural. Some will argue over whether the desire to rule over others is natural, but that’s not what Nemik is concerned with, it is when some achieve that desire and do rule over others, thus depriving them of their freedom. That kind of control is unnatural because no one is born able to control anyone else. Even the newborn son of a king needs a regent or a council of nobles to carry out the systems of power that have already been established by force and maintained by ‘fear’. Empires may justify oppression as necessary inconveniences for the protection of its citizens, but it is always primarily for the protection of the privileges of those that rule. Being an Emperor and ruling the Empire isn’t genetically determined. It requires ‘constant effort’ and is ‘brittle’ and liable to ‘break’. But it often needs a little help to be eliminated completely. As Nemik confidently predicts:

‘And know this, the day will come when all these skirmishes and battles, these moments of defiance, will have flooded the banks of the Empire’s authority and then there will be one too many. One single thing will break the siege. Remember this. Try.’

The authority he speaks about here is not expertise. It is not an authority given and maintained by consent. No-one has enough expertise to rule over another, and no one could consent to give up their right to freedom. The Empire is authoritarian, it is a totalitarian dictatorship, and the centralisation of its power structure is a weak point that acts and ‘moments of defiance’ can culminate to overthrow.

Unlike Yoda who said ‘there is no try’, Nemik says ‘try’, because he is not speaking to Jedi, he is speaking to the ordinary oppressed people suffering under the Empire’s control. To the Jedi the Force is a matter of will, it influences reality primarily through the exercise of the mind. But, although, rebellion may start in the mind, if it is limited to that it will not change anything. Real change takes changing minds, but also usually takes physical force to overthrow the structures of power.

Unlike the other episodes which featured Nemik, this one was written by the showrunner, Tony Gilroy, who presumably was the author of this Manifesto too. He later expressed how it was one of the things he was most proud of in the show:

‘One of our happiest, proudest things in the show is when Diego is listening back to [Nemik’s] manifesto. He opens Nemik’s manifesto that night before the funeral. And Nemik is, in the manifesto, saying, ‘We’re going to win because oppression is unnatural, and freedom is a natural [thing].’ And he has a whole big speech about how acts of rebellion are springing up all across the galaxy. All the people that are out there trying to make a rebellion, and they’re all atomized and spread apart. And so the show is really about watching this thing coalesce, and in the end we will coalesce into Yavin [Prime, where Rogue One takes place]. The consequences of that are good and bad for the people who’ve contributed the most to making it happen.’[40]

The Manifesto’s Future

As for the future of the Manifesto in an interview Tony Gilroy says the manifesto will likely make an appearance in season two:

‘But yeah, once the manifesto was in play, it’d be pretty hard to give it up. That’s the gift that keeps on giving. We may not be done with it yet. It’s material.’[41]

Some have speculated that Cassian continued to carry the Manifesto on him up until his end in Rogue One, speculating that it is the book-like object on his jacket in this image:

Whether it is the Manifesto or not in this picture, its words played a pivotal part in setting Cassian on his journey, and the sentiments it shares, echoing the words of similar idealists and revolutionaries, will continue to resonate as long as there is injustice and the desire for freedom.

The Origins Of Nemik’s Manifesto

Nemik’s Manifesto Origins

Tony Gillroy’s Manifesto

Initially, Tony Gilroy had no intention of creating a prequel to the movie ‘Rogue One,’ which he co-wrote. However, by 2018, Lucasfilm began developing a TV series that would explore the life of Cassian Andor before the events of the film.

Although Gilroy was not involved in this project, the studio sent him the script. Despite professing a lack of interest in the job, Gilroy wrote ‘a long forensic manifesto’ for Lucasfilm, outlining why the proposed approach wouldn’t work and suggesting an alternative idea that he considered ‘radical’ and ‘out there.’ This idea eventually became the basis for the series Andor.

As the showrunner, Gilroy uses Cassian’s story to meticulously depict the intertwined lives of ordinary people caught up in the formation of the Rebel Alliance, drawing parallels to the intricate storytelling style of Charles Dickens.

To quote an interview with Gilroy, he ‘wanted to do it about real people. … there’s a billion, billion, billion other beings in the galaxy. There’s plumbers and cosmeticians. Journalists! What are their lives like? The revolution is affecting them just as much as anybody else. Why not use the Star Wars canon as a host organism for absolutely realistic, passionate, dramatic storytelling?’ And this emphasis gave us the story of Karis Nemik and his manifesto.[42]

Absolute Power, The Book Of Sith

In direct contrast and conflict with Nemik’s Manifesto, is the manifesto written by Emperor Palpatine (Darth Sidious), known as ‘Absolute Power’ which is included in ‘The Book Of Sith’, about his personal philosophy and and political and violent means that marked his rise to power and established the Empire.[43]

The Empire would argue for a different kind of freedom, the kind that is obtained and maintained through power over others. They seek 1) Peace through war against worlds that resist being conquered, 2) Freedom (through incarceration of those who may upset the current order), 3) Justice (through immediate punishment of any hint of opposition), and 4) Security (through the protection of the elite). It is typified by the Sith Code: ‘Through strength, I gain power. Through power, I gain victory. Through victory, my chains are broken. The Force shall free me.’[44]

On Earth this is similar to the philosophy of Ayn Rand’s Objectivism, which she described as ‘the concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive achievement as his noblest activity, and [selfish] reason as his only absolute.’[45] To her selfishness is the only reasonable motivation and conquering others (such as Native Americans) was a virtue, as she believed the strong, smart and wealthy had priority over the rest of the population.

But as we see in Star Wars A New Hope, and ultimately in Return Of The Jedi, the power of the Sith was not unassailable and their victory was ultimately illusory, because of others following the principles Nemik spoke about in his Manifesto. After pondering over the Manifesto, Cassian attends his adoptive mother Maarva’s funeral procession on Ferrix, which turns into an uprising against the Empire when she delivers a recorded message urging rebellion. Chaos ensues as protesters clash with Imperial forces, leading to Cassian freeing his friend Caleen from prison, escaping with others off-world, and being recruited by Rael after confronting him to take him in or kill him. We will have to wait until the next season to discover more about his ideological journey, but he has begun to act on the ideals Nemik believed were already in him and which will lead to him being instrumental in the Empire’s defeat.

A Karis Nemik / Nestor Mahkno Connection?

We learnt in our previous article that Cassian — at least at the point he is part of the rebel heist — was inspired by a young Stalin, but some have speculated that Nemik may have been inspired by a real life revolutionary too.

Nestor Ivanovich Makhno, was an Anarchist, and the commander of the Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine during the Ukrainian War of Independence. He helped establish a mass movement by the Ukrainian peasantry to establish anarchist communism in the country between 1918 and 1921. Although his forces once fought alongside the Bolshevik Red Army, once Lenin’s ambitions included taking over free Ukraine the two sides fell out and fought, until Russia ultimately prevailed, and Makhno escaped to Paris, where he continued to speak out until his death from tuberculosis at the age of 45.[46]

One of the reasons for comparing Karis Nemik and Nestor Makhno is that their names share the same letter in the same order: Karis NE-MIK contains the letters N, E, M, and K found in NEstor MaKhno.

Another more tenuous reason is that Nestor and Nemik both wear very unique hats. Makhno wore a distinctive Papakha or Kalpak hat. However, Nemik’s red hat is similar to a Budenovka, a military hat from the Russian Civil War following the Russian Revolution. Although that hat wasn’t peaked nor originally red, the hat was painted red by some of the Moscow Troops in 1917. This hat was later replaced in Russia by the Ushanka, which could be seen as a combination of the two styles.

But it is in the teachings of Makhno and Nemik that we find the most similarities. Mahkno wrote his own Manifesto, The Anarchist Communist Manifesto in the 1920s, and explained and defended his beliefs in many writings that were later compiled into books.[47]

Among the similar themes between the two men are:

-

Both express strong anti-authoritarian and anti-oppression views, railing against tyranny and the subjugation of the common people by the powerful.

-

Both call for rebellion, revolution and the complete destruction of state power and authority as the path to liberation.

-

Both have a bedrock belief in individual freedom and the right to self-determination, free from coercion.

-

Both employ rousing, defiant language calling the ‘oppressed’ masses to rise up in revolt. For example, Nemik says ‘To rebellion!’, while Makhno declares ‘Rebel!’

They share the same core beliefs, rhetorical styles and revolutionary spirit in their respective struggles against tyranny and for human liberation. They share a conviction that true freedom and equality for the people can only be achieved through the destruction of dictatorial power structures.

However, there are differences in their positions: Makhno developed a much more comprehensive anarchist vision for the reorganisation of society on the basis of free soviets (communes), workers’ self-management, and voluntary federation. In the few excerpts we have, Nemik’s critique appears less developed and more abstract by comparison, but of course we don’t know what else was said in Nemik’s Manifesto.

Overall though, in their opposition to all forms of oppression, their faith in the revolutionary potential of the downtrodden masses, and their emphasis on individual freedom, there are common threads running through the perspectives of both men. Their words reflect some of the key and enduring concerns of the anarchist tradition.

Yet, for all the Anarchist concepts and phrases Nemik uses, he never explicitly says he is an Anarchist, and unlike Andor no-one else calls him that either, but there is another character in the Rogue One movie and Andor show who is an Anarchist and is inspired by another historical figure, and I will cover him in the next article.

Saw Gerrera

Saw Gerrera, The Anarchist

Although Cassian Andor is called an Anarchist in the ‘Rogue One Visual Guide’, only one character has actually been called that on screen, and that is the rebel Saw Gerrera. Gerrara is a resistance fighter who will stop at almost nothing to make the galaxy free again, even if sometimes his methods come at a high human cost. He appeared previously in the movie Rogue One, but was originally introduced as a character in the animated series The Clone Wars.[48] Returning to live action drama in the eighth episode of Andor, ‘Narkina 5’.[49]

In this episode revolutionary leader Luthen Rael, has come to see Gerera on the pirate planet of Segra Milo. We learn that Gerrera may have also been in the Aldhani Heist that Cassian was involved in (although he refuses to confirm this or deny it). Yet he expresses he is reluctant to help with Luthen’s plans, as he is unwilling to be a mercenary or risk his men for someone else. Something, which makes Luthen question Gerrera’s commitment:

Gerrera: ‘What are you, Luthen? I’ve never really known. What are you?’

Luthen: ‘I’m a coward. I’m a man who’s terrified the Empire’s power will grow beyond the point where we can do anything to stop it. I’m the one who says, “We’ll die with nothing if we don’t put aside our petty differences.”’

Gerrera: ‘Petty? I am the only one with clarity of purpose.’

Luthen: ‘Well anarchy is a seductive concept. A bit of a luxury I’d argue to a man who is hiding in cold caves, and begging for spare parts.’

Gerrera doesn’t correct Luthen we he is called an Anarchist. He doesn’t want a state or rulers. The Anarchy Luthen is speaking of here isn’t chaos, although the word anarchy has come to be associated with disorder and mayhem. Chaos isn’t a concept by itself, it is the lack of one. Chaos has no seductive principles, because it has no principles at all. Whereas Anarchy is a political philosophy

Anarchy is the situation when hierarchy doesn’t exist, where there is no nation state or other kind of ruler, not even elected ones. Anarchism is the belief that individuals and society are better off being able to make their own decisions about themselves without hierarchy, that hierarchy is not only unnecessary for organising and meeting people’s needs, but that people ruling over and having power over others (the state) is fundamentally wrong, as are any special societal privileges (due to age, class, gender, wealth, race, or religion), that any such hierarchies are dangerous because they require violent force (police and prison) to maintain, and that anyone living under a hierarchical system (including capitalism) is oppressed to some extent and not entirely free.[50]

But Gerrera didn’t begin life as an Anarchist. He was born on the jungle planet Onderon during the last years of the Galactic Republic, and greatly respected the monarch, King Ramsis Dendup. But when the benevolent king was overthrown and another installed in his place, Gerrera lost faith not just in the concept of the monarchy, but ultimately in rulers altogether.

Saw rebelled against the puppet ruler over his planet and the forces that had installed him who were spreading their power throughout the galaxy, and became the de facto leader of the Onderon rebels during the Clone Wars. Yoda promised Gerrera help in his fight, and — although they could not be seen to publicly be siding with Gerrera — Anakin Skywalker, Ahsoka Tano, and Obi-Wan Kenobi aided his troops with training and other support, and ultimately joined him in the battle.[51]

Here it is worth pointing out that Anarchism isn’t necessarily against the concept of leaders like Gerera, if by leaders you mean someone who by experience and skill can safely show the way forward, and can rally and inspire others with their enthusiasm for the cause. It is only when such people claim the right to make decisions for others, or expect special treatment that this strays into the territory of hierarchy. Early humans (and some tribal ones that have existed to the present day) have had honorary chiefs who have been respected for their wisdom, but don’t have any special wealth or power. Likewise some pirates followed a captain in the moment of battle, but were free to collectively decide to replace him when safe on shore.[52]

After the Republic became the Galactic Empire, Saw Gerrera’s militia was labelled as rebels. Seeing the Empire as a threat to everything they had fought for, Gerrera and his militia started resisting the Imperial powers, and — despite some losses and setbacks — he rallied his partisans:

‘These have been hard years. We’ve lost comrades, friends, family...to the Empire. Dark times. And yet the fire still burns. Hope still burns. The Jedi are not yet lost. We are not yet lost. Kashyyyk is not yet lost! For the cause!’[53]

Rogue One

Which brings us to the events leading up to ‘Rogue One’: After her mother was killed and her father Galen was taken to work on the Death Star, Gerrera sought to protect a young Jyn Erso, rescuing her and bringing her to his outpost on the planet Wrea. As Jyn grew older and Saw became increasingly paranoid over time, he feared she would eventually be recognized as the daughter of an Imperial collaborator and exploited to be used as leverage against her father Galen. He was constantly worried about others finding out who Jyn really was, so when she turned sixteen, he abandoned her in a bunker with only a knife and blaster, telling her to wait until morning before he disappeared. He justified this decision to himself and later to Jyn by saying she was already one of his best soldiers and could survive on her own. But to Jyn, at the time it felt like a betrayal that left her disillusioned with Saw and the rebellion itself.

It was not long after this that the meeting with Luthen Rael we began with took place. But over a month later, Gerrera changed his mind and met with Rael again, agreeing to join in the attack on the Spellhaus power station, which is crucial to supplying energy to Imperial facilities.[54] However, he insisted on providing air support only, without taking tactical orders from Anto Kreegyr, who was leading the attack. With the attack just a day away, Rael said it was too late, the situation had changed as the Imperial Security Bureau had learned about the plan and would be waiting for the rebels at Spellhaus. However, Luthen did not want the Empire to know they had an Imperial spy, and was prepared to let Kreegyr’s men continue the attack and die to keep the secret. Luthen left the decision about whether to warn Kreegyr up to Gerrera, but advised that in doing so they’d lose valuable intel, and Gerrera ended up going along with Luthen’s plan, agreeing that it is, ‘For the greater good.’:

‘Call it what you will.’

‘Let’s call it…war.’

―Saw Gerrera and Luthen Rael

Mon Mothma

Gerrera was not one to wait around to get involved when he felt he had a chance to make a strike at the Empire. In ‘Star Wars Rebels’ Season 4, Episodes 3 to 4 (‘In the Name of the Rebellion’) the Rebellion is considering tapping into an Imperial relay to gather crucial information about their plans, and Mon Mothma, the leader of the Rebel Alliance who also features in the Andor series, urges a cautious approach. However, Saw showed up and called them cowards for not doing what it took to win. After Mon Mothma cut him off, Saw planned to destroy the relay himself. Mothma, however, was not impressed with his tactics, even when he achieved his aims and the rebellion benefitted from them:

Gerrera: ‘If you continue to allow this war to be fought on the Empire’s terms, not yours, you are going to lose.’

Mothma: ‘I will not be lectured on military strategy by a man who has proven himself a criminal.’

Gerrera: ‘The Empire considers both of us criminals. At least I act like one.’

Mothma: ‘You target civilians! Kill those who surrender! Break every rule of engagement! If we degrade ourselves to the Empire’s level, what will we become?’

Gerrera: ‘There she is! That’s the leader the Rebellion needs! Where is that fire? That passion when your people need it most? I hope, Senator, after you’ve lost, and the Empire reigns over the galaxy unopposed, you will find some comfort in the knowledge that you fought according to the rules.’[55]

Later, the now bald-headed Gerrera orchestrated a bomb attack on Moff Quarsh Panaka’s residence, successfully killing the Moff, who was said to be one of the Emperor’s most loyal servants. The bombing narrowly missed taking out Princess Leia Organa of Alderaan as well, and further alienating him from some of his rebel allies.[56]

His campaigns against the Empire becoming increasingly brutal, the Alliance High Command censured Gerrera at Mon Mothma’s urging and cut all official ties with the Partisans. By then, Gerrera had lost his right leg, struggling with a basic cybernetic replacement. His lungs were also damaged, confining him to an armoured suit with a breath mask for supplemental oxygen.

‘We are not insurgents. We are partisans. We are a rebellion. I bring battle-hardened fighters. I bring experienced tacticians. I bring pilots, a squadron of them. I bring the means with which to fight back. I am inviting you, both of you, to join me in this.’

―Saw Gerrera to Baze Malbus and Chirrut Îmwe

Propaganda Of The Deed

Most Anarchists do not take such a violent approach. So what kind of Anarchist was Saw Gerrera? We never hear about his hopes beyond the overthrow of the empire, perhaps because he felt that organising that future world would be left to other people during a time of peace he was trying to help make possible. But it seemed Saw Gerrera followed a form of ‘Propaganda Of The Deed’, a strategy where anarchists used dramatic acts of violence and terrorism to inspire further revolt among the masses for their cause, rather than just expressing ideas verbally. Gerera’s bombings were part of this pattern of deploying dramatic violence to spark insurgency against Imperial control aligns with this.

Proponents of insurrectionary anarchism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries embraced Propaganda Of The Deed tactics like bombings, assassinations and arson targeting the state and ruling class. One such revolutionary, Mikhail Bakunin, stated that ‘we must spread our principles, not with words but with deeds, for this is the most popular, the most potent, and the most irresistible form of propaganda.’[57]

These terrorist acts aimed to ignite a ‘spirit of revolt’ by showing the State and elite were not omnipotent, while also provoking escalating repression that could radicalise more people. Between 1881 and 1913 eleven Presidents, Prime Ministers, and Kings were killed. Leading to Anarchists being rounded up and imprisoned, whether there was any suspicion that they were involved or not.[58]

However, such tactics were ultimately abandoned as ineffective and counter-productive. Yet Gerrera never seems to learn this lesson, if it is indeed appropriate for his situation.

Sabrine Wren & Ezra Bridger

In the episode mentioned previously, Ezra Bridger and Sabine Wren — who later appear in the streaming show Ahsoka — are saved by Saw Gerrera during an ambush by Imperial forces. Saw invites them to join him in investigating an Imperial cargo ship. They discover the ship is transporting prisoners and Kyber crystals for the Empire’s superweapons. Tensions rise when Ezra confronts Saw about his violent methods. Ezra argues for maintaining ethical standards, while Saw insists that extreme measures are necessary to win against the Empire. Despite their disagreement, they work together to escape the ship and save the prisoners, but although Gerrera argues he did what he had to in order to accomplish their mission, Ezra is not impressed by his methods:

‘I’m fighting for you and everyone else not to lose what they’ve got. And I won’t apologise for how I do it.’

‘Then you’re no better than the Empire.’

―Saw Gerrera and Ezra Bridger

And Gerrara has been compared with Darth Vader, including by the actor who played Gerrera himself, not just because of breathing difficulties and mask but also for extremeness.[59] Perhaps such evil needed a counterpart on the other side of the political spectrum, to fight dirty against the Empire’s fascism, and it couldn’t find someone more committed than Saw Gerrera.

Forest Whitaker

Gerrera is played by Academy-award winning actor Forest Whitaker. Whitaker is no stranger to playing divisive characters, he won his Best Actor award for his portrayal of Ugandan dictator Idi Amin, in 2006’s The Last King of Scotland, and also portrayed anti-apartheid campaigner Archbishop Desmond Tutu in 2017’s The Forgiven. Outside of acting he has co-founded the International Institute for Peace at Rutgers University, and was inducted as a UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador for Peace and Reconciliation. In 2009 he was given a chieftaincy title in Imo State, Nigeria where his ancestors were from before being sold into slavery.[60]

However, unlike Whitaker, Gerrera is less interested in peace — at least while the Empire still rules. Perhaps some clue to his behaviour is in his name itself. Saw Gerrera’s name is a ‘mnemonic riff’ on the Argentine revolutionary Che Guevara who himself is a controversial figure even on the Left of the political spectrum.[61] Although Guevara was not an Anarchist, like Andor and Gerrera he was an insurrectionist, and insurrectionism itself began as an Anarchist strategy for overthrowing oppressive states, and proved to be an effective strategy in the Cuban revolution, if not always so elsewhere.[62]

In the next article we will return to Gerrera and Luthen Rael, and where Gerrera’s methods ultimately lead him.[63]

Radical Star Wars Conclusions

Saw Gerrera & Luthen Rael

Means Vs Ends

No character in the Star Wars universe ever seems to question the good intentions of Saw Gerrera (at least not on the rebel side). They agree that his end goal of being free from the Empire is a worthy one. Where he becomes a controversial character is in how far he will go – what means he will use – to achieve these ends.

Among the other rebels – whose methods are less extreme – the question is whether Gerrera is a necessary evil, or if he does more harm than good. Something which even some of those whose lives he’s saved wonder about. He is part of the story of so many major characters, but often finds himself out of favour with those fighting to overthrow the Empire like him.

As to why he is so extreme, Forest Whitaker, the actor who plays Gerrera gives us some of his own insight into the character:

‘He understands that the universe could be destroyed and worlds could be destroyed if he doesn’t succeed. And he’s one of the only people who will do everything to make sure the Imperial forces don’t. He’s talking about how you maybe make compromises that may harm people, or may harm the situation, or people may question it, but if you’re doing it for the good, there’s a positive thing about that. But what does it make you become? And how do you change as a person?’[64]

To Anarchists the means of revolutionary acts must be in harmony with the ends. Otherwise those who carry out revolution will become as evil as the evil Empire they hope to overthrow, and the extremes they go to will end up being justified to maintain the power they regain. This was one of the reasons Mikhail Bakunin opposed Marxism, as he accurately foresaw what it would lead to.[65] There must be a moral high ground to stand on and stay, without resorting to the immortality of the oppressors, as Malesta wrote:

‘The end justifies the means. This saying has been much abused; yet it is in fact the universal guide to conduct. It would, however, be better to say: every end needs its means. Since morality must be sought in the aims, the means is determined.’[66]

The how it is achieved is as — if not more — important than what is achieved. This separates Anarchism from Leninism, in which it seems almost any means may be used in order to one day eventually achieve the ideal ends.

Having said this, most Anarchists are not pacifists, and they believe in the right of self-defence, and in what might be called defensive violence. That the unjustly imprisoned have a right to break free of their bars and chains, that those who have been stolen from — whether it is from their pockets, home or wages — have a right to get back what is rightfully theirs, and those who are being deprived of freedom have a right to fight to obtain it.

So the question becomes of how much fire it is appropriate to use against the fire being used against you. At what point do you just spread the flames, or put them out. To Gerrera – who has personally seen more injustice, persecution, cruelty and death than most – almost nothing is too extreme if it is effective in putting out the raging, spreading fire of the Empire.

Luthen Rael

The question of what and who and how you become when you go to such lengths is one that another revolutionary leader, Luthen Rael, also struggled with. He saw Gerrera as a useful tool, but an unpredictable one, a rough hammer to bludgeon with, when that was the only kind that might work. Yet Luthen felt in using such people and encouraging such acts that he was too becoming compromised, and losing the higher ground he sought to stand on

In episode 10 of Andor, Luthen meets with his informant, who expresses his fear and disillusionment with the dangerous double life he is leading. He wants to leave his position as a spy, but Luthen insists that he stay because of the critical intelligence he provides to the Rebellion, revealing the personal sacrifices he has made for the cause:

‘Calm. Kindness. Kinship. Love. I’ve given up all chance at inner peace. I’ve made my mind a sunless space. I share my dreams with ghosts. I wake up every day to an equation I wrote 15 years ago from which there’s only one conclusion, I’m damned for what I do. My anger, my ego, my unwillingness to yield, my eagerness to fight, they’ve set me on a path from which there is no escape. I yearned to be a saviour against injustice without contemplating the cost and by the time I looked down there was no longer any ground beneath my feet. What is my sacrifice? I’m condemned to use the tools of my enemy to defeat them. I burn my decency for someone else’s future. I burn my life to make a sunrise that I know I’ll never see. And the ego that started this fight will never have a mirror or an audience or the light of gratitude.’[67]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-3RCme2zZRY

Was Luthen so different from Gerrera? He made decisions that included sending thirty innocent men to their deaths to maintain the secrecy of one Imperial spy, perhaps calculating that it would allow more lives to be saved later, but coming at a great cost for a possible outcome that might not happen. However, Luthen seems to maintain a better standing with the other rebel leaders, perhaps because he has a respectable side, and he doesn’t get his own hands as dirty. Although his actions and their consequences could be just as risky to himself and others. In answer to this, the showrunner, Tony Gilroy, gives us the insight that:

‘Well, he’s [Luthen’s] a chess player, man. He’s sacrificing a castle to protect his queen. So I don’t think the Kreegyr story is over yet. Luthen is in a very tough spot, and his position over the next five years is only going to get more complicated, because how do you build this network? Earlier on, he says that he’s been building it for 10 or 12 years, but all of a sudden, with Aldhani, they’re going loud. All of a sudden, they’re going to expose themselves. And in a classic political sense, he’s an accelerationist. He believes in the fact that you have to make it hurt really bad in order to bring people to change. Once you make that announcement [via the Aldhani heist], once you do that, you’re no longer in charge of the thing that you’ve put out there. So how do you juggle your paranoia? How do you maintain your secrecy? How do you go big and stay small and tight? How do you expand while expansion makes you more vulnerable?[68]

In the last article we spoke of Mon Mothmas repulsion toward Gerrera and her ultimately cutting him off. Yet, although she was initially hesitant to engage in a violent rebellion, through her interactions with Gerrera and Luthen she eventually came to the decision that active combat was necessary to overthrow the Empire. We do know though what ultimately happens to his character, Saw Gerrera, as shown in the film Rogue One. …

Rogue One

We return to Saw after the arrival of a former Imperial cargo pilot, Bodhi Rook, who defects to the Rebel Alliance and makes his way to Gerrera’s base on Jedha. Bodhi carries a crucial message from Galen Erso, Jyn Erso’s father, intended for the Rebellion. Galen trusts Saw to get the message to the right people. However, Saw, being distrustful, subjects Bodhi to interrogation to verify his story, leaving him incapacitated.

Knowing that Saw Gerrera is volatile, the Rebel Alliance leaders decide to send someone who has a personal connection to him: Jyn Erso, Galen Erso’s daughter, who was once taken in and raised by Saw after her parents were taken by the Empire. Cassian Andor, a Rebel intelligence officer, is tasked with taking her to Gerrera to get this information (and to kill Jyn’s father if he finds him).

Upon reaching Jedha, Jyn and Cassian are captured by Gerrera’s forces. Saw shows Jyn a holographic message from her father, Galen Erso, revealing the hidden flaw he has placed within the Death Star’s design. Jyn laments how he had abandoned her at 16, leaving her disillusioned with his war:

‘The last time I saw you, you gave me a knife and a loaded blaster and told me to wait in a bunker ‘till daylight.’

‘I knew you were safe.’

‘You left me behind.’

‘You were already the best soldier in my cadre.’

‘I was sixteen.’

‘I was protecting you!’

―Jyn Erso and Saw Gerrera[69]

However, as they speak, in an effort to demonstrate the power of the Death Star and eliminate Saw Gerrera’s insurgency, Grand Moff Tarkin decides to test the Death Star’s superlaser on Jedha City.[70] The low-power shot from the Death Star obliterates Jedha City and causes a massive shockwave. Realising the danger, Saw releases Jyn, Cassian, and the other prisoners, urging Jyn to save the Rebellion with her father’s message. But Gerrera refuses to run, staying in the Catacombs as the blast consumes him after removing his breath mask. Up until the end, he retained his belief in the revolution and hoped others would too, that they would see the day it succeeded, even though he didn’t. His final act expressed his commitment to the cause over his own life:

‘Save the Rebellion! Save the dream!’

―Saw Gerrera, to Jyn Erso, as Jedha is ripped apart

Rebels And Dreamers

Although Gerrera dies, his followers who escaped the destruction of Jedha carried on, although they changed the name of their group in tribute to his last words:

‘We call ourselves the Dreamers.’

‘Dreamers? Azen said you were Saw Gerrera’s partisans.’

‘We can’t be him. We’re just following in his footsteps. We’re keeping alive the Dream. Saw was the face, the voice, of our cause.’

―Staven and Iden Versio[71]

Some may wonder whether in the final equation Gerrera did more harm than good, but without his mentorship of Jyn Erso would the Death Star plans have been found, and without those plans would Luke Skywalker have been able to bring down the Empire’s greatest weapon?

Mandelorian showrunner Dave Filoni considered Gerrera, ‘the original rebel. He is the first one in a long line of people that got trained by Jedi to fight for themselves; to save their planets during the Clone Wars. He’s the beginning of what would eventually become the Rebel Alliance.’[72]

Thus this father of Rebel Alliance not only helps Anakin Skywalker, Ahsoka Tano, and Obi-Wan Kenobi, Sabine Wren, Ezra Bridger, but trained Jyn Erso, helped Luthien and Mon Mothma (even when she doesn’t want his help), and prepared the way for those who would come after to see his dream realised such as Luke Skywalker, Han Solo and Princess Leia (despite him almost accidentally killing her as a child).

Conclusion

All of these articles are just my interpretations of the words of a fictional character created by a script writer. In the case of Cassian Andor and Jyn Erso they were writing about rebel martyrs, or in the case of Gerrera and Luthen, revolutionary leaders, or in the case of Karis Nemik an idealist who provides inspiration for revolutionary change.

Gerrera was nothing like Karis Nemik in his personality or skills, or Cassian or Jyn for that matter, but they all shared the same goal: to overthrow the structures of power oppressing the people, which they each accomplished in their own way, even if it ultimately came at the cost of their lives.

However, whatever the intentions of the scriptwriters, words mean something and they come from somewhere. Words carry weight and meaning. They emerge from our cultures and histories, they are loaded with meaning and associations and concepts we’ve attached to them over time. While those connections are sometimes coincidental or misunderstood, words can also deliver intended messages to those attuned to them, to those who listen and understand

I can’t be certain that the message I took from this fictional world were the ones that the writers intended, but I believe my conclusions fit into the context of the characters, their words and their actions, and that these are consistent with a way of looking at the world that rejects hierarchy and prioritises freedom, in a way that is unique to Anarchism. But I leave you to your own interpretation. Either way the stories Andor and Rogue One have given us have been a fascinating and entertaining story.

We don’t know what part Gerrera may play in Andor, Season 2, but Forest Whitaker has confirmed he will be returning to play the part again.[73] It’s my hope that Andor Season 2 will continue to explore these ideas, as well as continue to tell a relatable human story, one which – the way the world is going right now – seems very relevant.

There’s already so much politics in the show to begin with, and we’re trying to tell an adventure story, really. So adding strong alien characters means that all of a sudden, there’s a whole bunch of new issues that we have to deal with that I don’t really understand that well or I just couldn’t think of a way to bake them into what we’re doing. You’ll see more as we go along, … There is a more human-centric side of the story and the politics of it. There’s certainly no aliens working for the Empire, so that kind of tips it one way, automatically.[74]

-

Have I missed anything relevant out over this article series? Anything you would have liked to have seen expanded upon?

-

Would you want to see a similar series about Anarchy / Communism in Star Trek

(Original Series / Next Generation / Strange New Worlds)?

I also wrote a relevant article on the Last Of Us TV show: The Last Of Us’ Utopian Town Of Jackson

[1] Behind Marvel but ahead of Harry Potter & James Bond in terms of viewers. It is also the third longest ongoing sci-fi series (1977), after Doctor Who (1963) & Star Trek (1966).

[2] “No, I am your father.” Empire Strikes Back spoiler.

[3] Not so flatteringly represented by the Ewoks. ‘In the audio commentary for the 2004 re-release of Return of the Jedi, as well as the documentary Empire of Dreams: The Story of the Star Wars Trilogy, Lucas also cited the Viet Cong as being the primary inspiration for the Ewoks, particularly their defeat of the Galactic Empire.’ (https://starwars.fandom.com/wiki/Ewok#Behind_the_scenes)

[4] James Cameron: “In Star Wars the good guys are the rebels, they’re using asymmetric warfare against a highly organized empire, I think we call those guys terrorists today.”

George Lucas: “When I did it they were Vietcong. … That was the whole point.” (James Cameron’s Story of Science Fiction, 2018)

[5] Time magazine, 22 April 2002. Archived here — https://web.archive.org/web/20020423000824/http://www.time.com/time/sampler/article/0,8599,232440,00.html

[6] According to J.W. Rinzler’s ‘Making Star Wars’, a draft screenplay for Star Wars: A New Hope from 1973 identified the Empire as a stand-in for “America 10 years from now”.

[7] In order of release, albeit Episode 4 chronologically.

[8] Yep, the Death Star really had a shopping mall! https://starwars.fandom.com/wiki/Death_Star/Legends

[9] It is the highest non-animated IMDB rated film after the original series.

[10] https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-features/disneys-bob-iger-rogue-one-are-no-political-statements-955047/

[11] Ibid.

[12] Or the others proved to be much less interesting.

[13] https://www.imdb.com/title/tt9253284/ — Tony Gilroy wrote the first three and last two (11–12) episodes, Dan the next three (4–6).

[14] I didn’t know it was a remake, did you? The first adaptation is a 1988 television film starring Richard Chamberlain.

[15] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Clayton

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nightcrawler_(film)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Gilroy_(film_editor)

They are sons of Tony Award winning playwright, Frank Gilroy, who was also a successful writer for television and film, so I guess their writing skills are genetic, or benefitted from their father’s example and training, if not also his contacts.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frank_D._Gilroy

[16] ‘no one sits around thinking about what we should do politically. It just happens instinctively.’ — https://www.indiewire.com/features/general/andor-not-political-disney-plus-tony-gilroy-interview-1234780620/

[17] http://www.simonsebagmontefiore.com/young-stalin/

[18] https://www.rollingstone.com/tv-movies/tv-movie-features/andor-explained-season-1-finale-season-2-preview-1234626573/

[19] ‘Andor’ entry, Star Wars Rogue One Visual Dictionary, 2016.

[20] ‘Anarchism or Socialism?’ Joseph Stalin, 1907.

[21] Episode 4: Aldhani.