Illustrations by Dorris Whitman Chase

Rudolf Rocker

The Six

introductory note on The Six

In The Six Rudolf Rocker has taken some well-known figures from world literature and done two things with them: first he has made them live again, and then he has made them, serve a purpose of his own; without doing violence in any way to the traditional character of any one of them, he has used them to introduce a beautiful dream of a world rebuilt and mankind set free.

He begins with a picture: At the edge of a boundless desert we gaze on a black marble sphinx, whose eyes are fixed immovably on something beyond the far horizon, and about whose eternally silent lips there plays a scornful smile, as if she were gloating over her unguessed riddle. Six roads coming from widely separated lands converge and end on the sands before her outstretched paws. Along each road a wanderer moves.

These wanderers, the six figures from world literature, are presented in three contrasting pairs.

First pair:

Faust, who burns himself out in ascetic brooding over the mystery of life, exhausts himself in the vain endeavor to trace its origin and its end, to find in it a meaning and a purpose, makes at last the traditional bargain with Satan—his soul in exchange for another life span and an answer to his question—and wakes at last to the realization that his second span is spent, and that all that he has had is some trivial, transitory pleasures, and all that he still has is his old question, still unanswered.

Contrasted with him, Don Juan, who declares that life is not a thing to be examined and understood, but to be lived and enjoyed; who says, knowledge is unattainable, if attained, it would be useless; pleasure is real and is sweet. It is fleeting, but it can always be found anew. I will pursue it, scorning any knowledge but what it brings me, defying every law and custom that would restrict my enjoyment. Thus speaking, thinking thus, he lives his life; drains pleasure to the dregs; comes to know that what he is draining is but dregs; at last, burned out by his lust, reaches his end, knowing that all that he has had is transient triumph and all that he still has is his defiant pride.

The second pair:

Hamlet, who, seeing the cruelties, the horrors, the follies of the world and finding them unendurable, flees from them.

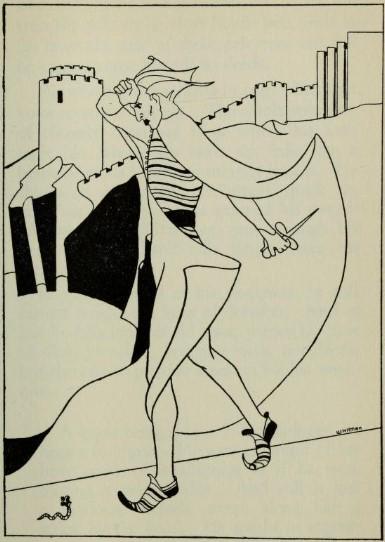

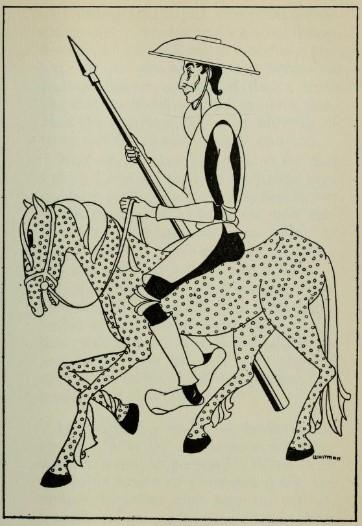

Don Quixote, who, seeing the same cruelties, horrors, and follies, sets out with a rusty sword and a broken lance to do battle with them.

The third pair:

The monk, Medardus—created by Hoffmann to carry the legend of the devil's elixir—who quaffs the elixir and gives himself up to many forms of mystic sin.

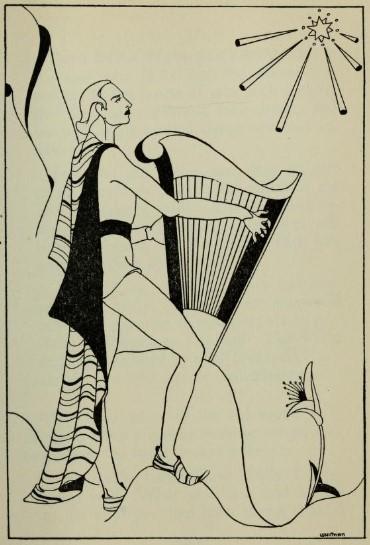

The bard, Heinrich von Ofterdingen, whose songs are inspired by an equally mystic holiness.

These are the six wanderers who move along the separate roads, to fall at last, exhausted and defeated, in the sand at the feet of the sphinx — who heeds them not at all.

Year follows year into the ocean of eternity. The sphinx still broods on the desert sands—

And then a new day dawns. One by one the wanderers awake. Earnest sage and frivolous reveler arise and greet each other. The melancholy Prince of Denmark and the noble and imaginative Knight of La Mancha; the devil-ridden monk and the angel-inspired singer, face one another on the desert sands. They talk together and resolve their differences. The dawn advances, the desert turns to greensward, the sphinx dissolves into dust. A new day is at hand—but no summary will serve to convey this picture that Rocker has drawn of The Awakening.

In two things I have reveled as I worked at my task of translation:

In the completeness of understanding with which Rocker has identified himself with each of his characters in turn, thinking his thoughts and feeling his feelings and giving dramatic and satisfying expression to them all. (It seems to me that he has done this most impressively with the convincing, defiant sensualism of Don Juan and the unanswerable, gloomy logic of Hamlet.)

And in the incomparable beauty of the slightly archaic German prose.

The language of musicians is to me an unknown tongue, so the words I am about to use will likely all be wrong. But The Six seems to me like a great symphony. There is a short introduction, a prelude, which sets a theme, sad and enigmatic. This theme is repeated after each of the six movements which make up the body of the symphony. Each movement has its own mood and tempo. After the last repetition of the introductory theme there comes a jubilant, resolving finale. Probably musicians have a name for such things. I have none; I merely know that the whole work affects me like a great orchestral performance.

The Six, as we have it now, is the final and finished outgrowth of a lecture, which became a set of lectures, then a book. I think nothing reveals more convincingly, not only Rocker's literary skill, but also his great power as an orator, than the fact that he could make those lectures real and impressive to new audiences of untaught workers—to the half-literate sailors whom he met in a British internment camp during the World War, for instance. That he did this is made clear by the fact that he was called upon to repeat the lectures again and again. That he did not achieve this success by talking down to the cultural level of his hearers is shown by the fact that the scholars and writers who were also among the interned men were equally impressed and equally eager for the repetition.

Men and women who heard him give the Hamlet-Don Quixote antiphony in London have described to me the response of his auditors—shrinking down in their seats, grasping tensely at the edges of their chairs, as, with drawn faces, they sank beneath the devastating logic of Hamlet's philosophy of despair; sitting forward, hands on their chair seats, feet drawn back as if about to spring from their places, when, with upturned faces they watched the valiant Don ride forth against evil giants transformed by magic into the guise of windmills. The reader of the book finds himself equally swayed by the author's changing moods.

None of Rocker's works seems to me to hit a higher level of artistry than this; none has made me feel so deeply the inadequacy of my rendering.

Ray E. Chase.

Los Angeles, March 11, 1938.

The Six

The heaven is gray. The desert yawns.

A mighty sphinx of smooth black marble lies outstretched upon the waste of fine brown sand, her gaze lost in dreary, infinite remoteness.

Nor hate nor love dwells in that gaze; her eyes are misted, as by some deep dream, and over her dumb lips' cold pride there hovers, gently smiling, just eternal silence.

Six roads lead to the image of the sphinx, six roads that come from distant lands to reach the self-same goal.

Along each road a wanderer moves, close-wrapped in Fate's grim curse, with forehead marked by a power not his own, striding on-ward toward some distant world glimpsed faint on the horizon, such wide, wide worlds away in space, so very near in mind.

I The First Road

The city rests amid soft hills. Its ancient pinnacles glow with red and gold from the setting sun. Thick walls with strong towers enclose the motley tangle of narrow streets and alleys that wind and cross as lawlessly as the paths of a garden maze. And it seems as if every alley hides its special secret, for whose solution the uninitiated seeks in vain. In gloomy corners and around the gray projections of the old gable-roofed houses broods the long, long past, by time forgotten.

The old fountain in the marketplace murmurs softly, just as it did years and years ago. The massive shadow of the old cathedral rests on the silent square which today seems so abandoned by the world. Only a withered old woman stands lonely by the ancient fountain, dreaming of vanished times that will never come again.

Spring has come suddenly into the land to put an abrupt end to the tyranny of a long winter. The radiant sky and the young green of the pastures and meadows have lured the people out before the city gates, and joyous crowds seethe or stroll unrestrained in the warm rays of the bright spring sun, which have thawed all the numbness that had bound their hearts. Young and old, great and small, have journeyed forth into the open today to shake the dust from their souls and prove themselves unharmed by the gray monotony of the gloomy winter days.

Now it is getting evening, and the tones of ancient bells peal solemnly through the mild air, warning the town folks that it is time to turn homeward. Through the city gates stream troops of happy human beings, laden with bouquets of flowers and bunches of greenery, and the cheerful sound of song fills the air. The ancient streets are filled with lively, chattering groups, strolling leisurely and with light hearts toward their dwellings, till with the gathering darkness life slowly dies out in the streets and squares.

The last rays of the departing sun have now long faded out, and the mild spring night spreads its pinions soundlessly over the abandoned nooks and alleys, which glimmer strangely in the moonlight.

The glow of lamps has gradually vanished from the tiny windows. Only here and there a lonely light still sends its beam into the silence of the night. Perhaps a sick man lies there fighting against his pain or a dying man commends his tired soul to God.

Profound and solemn peace hangs over the slumbering houses, interrupted from time to time only by the stern strokes of the old cathedral clock and the alert horn of the watchman.

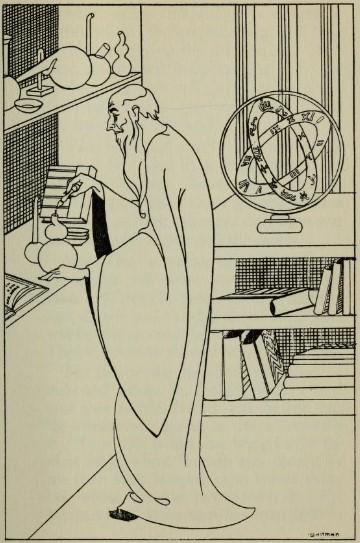

On a little height in the heart of the dreaming city there rises an age-old, stately building that seems even stranger and older than the houses round about it. At the narrow Gothic window of a tower room sits an old man with long white hair and flowing beard, gazing, lost in dreams, away across the gables of ancient roofs shimmering green in the pale moonlight.

The heavy oaken table in the middle of the room is overflowing with books and papers piled together in a confused heap. Along the faded walls stretch long shelves covered with rare specimens and strange instruments. A cunningly wrought oil lamp fills the room with its feeble glow, which strives in vain to penetrate into the gloomy corners of the apartment.

With a weary gesture the old man sweeps the hair back from his brow and murmurs thoughtfully into his beard:

Now all is once again as silent as the grave, and above the sleepers arches as of old the vault of infinite space in which millions of worlds whirl unceasing in their course. May their slumber be refreshing to the just, and undisturbed by frightening dreams! And for whom could that be possible! For lives that turn always about the pitiful needs of the hour and that never try to build bridges into eternity. Well for them! The Creator has not made them too exacting. It is not easy to disturb their equilibrium. They are thus safeguarded from the hellish torment of an anguished urge that gnaws at the heart like an ever-hungry worm.

I feel it in my blood like a creeping poison at this time, when unfathomable Nature writhes in the pangs of rebirth, and new life bursts from myriad fountains in forms and patterns that are endlessly new. Then spring also goes slowly on her way, summer and autumn gradually vanish, and grim winter once more wraps everything in a shroud. And then the same old game begins again. Who can fathom the profound meaning of this eternal becoming and wasting away, in which life and death are so strangely mingled and every end is pregnant with a new beginning?

Is death in fact an end, or only a beginning, or at the same time end and beginning in the vast cycle of events? Where is the boundary that separates the has been from the about to be? Where the vast First Cause from which all being springs?

The more I work at this dark riddle the more do I appear a stranger to myself. I am seized with mystic dread of my own nature, which lies before my eyes as difficult and enigmatic as the dumb eternity of infinite space itself.

Whence come we? Whither do we go? Did I exist even before my mother's body swelled with a new life? Shall I go on when once the last spark of this existence has faded like a dying flame?

There is in us so much of the dark and mysterious, lying deep-hidden in our souls and never rising to the surface to be seen. What we are able to tell one another about the petty cares of every day and the tiny bits of joy that all too seldom fall to our lot, does not go very deep and affects us little more than mechanical movements performed unconsciously. But the things which slumber in the depths do not seek to reveal themselves; they lie at the bottom of the mind where obscure, primitive forces trace their silent cycles and never emerge into the light of day.

In the depths lie all those hard, strange things which cause a tightness in the throat when sometimes a note, torn loose, strays out of the abyss, a dumb and nameless thing threatens to acquire speech. In the depths, too, are rooted the walls which we erect between us, those walls dividing man from man in whose shadow unspeakable loneliness and nameless longing creep softly on their way. But the last and deepest depth is never revealed to us; what lies there always sedulously shuns the luring caresses of the outer world.

Even where, in the burning fire of sex, quivering body presses against body and two souls seem to fuse in the mad tumult of passion, there still lingers something strange, lurking dumb in the background of feeling, so that not every word shall be uttered, not every deepest, quavering lust shall be allayed. Even where love lies drunk with ecstasy there still glimmers always in the vague depths of thought a threatening enigmatic, Who knows?

Yes, if it were granted to us to look on the Creator in his workshop, to see the beginning and the end of all things, then perhaps we should also know what it is that lies hidden beyond that thin wall that hems in the brain, where furtive thoughts crowd one another in its narrow space and lurk unsuspected in its secret places. Then the meaning of life would no longer be for us a sealed book. But what boots here all our grubbing! We poor wretches clutch with our thoughts at the mere surface of events and are always blindest just when we think we have found enlightenment.

I sit so many an anxious night in this dreary house, turning over in my poor brain world-embracing thoughts that are to bring me release from this everlasting torment—

Release? O gracious Virgin, Thou pure and blessed one who dwellest there above by God's own sacred throne! Of thy consecrated body was born the Savior who brought to men release from the curse of sin. But it seems no savior was born for me; for no deliverer ever quenches the burning fire of intense longing in my breast.

Ah, how much easier it is to free man from his petty sins than from the whirling thoughts which clamor for understanding and hover, brooding, over unfathomable abysses! Will the hour of release ever strike for this great longing, that hungers for a revelation and senselessly gnaws at itself in dull torment?

The fulfillment of all my yearning once circled about my head like a shining star, but with the coming of the burden of the years it has fled ever farther into the distance and has left only desert wastes behind.

While youth still steeled my body and I looked at life with eyes undimmed, I dreamed of an exalted hour when all the knots with which Fate had bound me would come asunder in my hands. With eager impulse my mind pounced on everything that human intellect has brought forth, and sought in ancient books and systems for the final goal of wisdom. But every time that yearning saw a gate before it, the mind glimpsed its final goal on the horizon, it proved just another beginning, anxious and difficult, a will-o'-the-wisp dancing mockingly over graves.

And in the silent course of years there ripened in me the certainty that all our knowledge does not help us to grasp the ultimate meaning of things. Like the blind, we go always round and round in circles. We stride off toward a distant goal and come back always to the same old place.

Are there perhaps on some other of the worlds that whirl and roll so strangely through the depths of eternal, all-embracing space also beings which, as on this earth, hunger for understanding and, obedient to that fierce urge, burn themselves out in hellish torment and heavenly bliss?

It often seems to me that out of the immeasurably far away I catch the silent rhythm of those worlds that have their paths off there in the depths of space. It sinks like a mighty chord into my soul: I think I hear the harmony of the spheres, and all existence suddenly seems clear to me.. But scarcely have I moved a hand to bind this inner experience fast with words, when the momentary spell is shattered like a bursting bubble; desolate void gapes at me on every hand.

And still it never leaves me, that great yearning that feeds on my heart's blood, that passionate longing that cries for understanding; it never leaves me, though I always do but march from disappointment to disappointment. Even today, when the portals of the tomb already gape for this worn body, the great yearning will not be stilled. Almost it seems as if the silent torment grows yet stronger. Why, oh, why?

And I was always so pious! An undeviating herald of Thy glory!

Then from a dusky corner of the room a merry peal of laughter assailed the old man‘s ear, and a voice spoke:

You fool! You old fool! Already you are feeling in your rotting limbs the cold touch of death, and still you can't give up your madness. Have you never recognized your deepest nature? All your life you have fancied yourself pious, yet you have never been pious. Do you know what true piety means? A man is pious from indwelling impulse and obeys implicitly the divine command. He does not calculate, makes no reservations, is not plagued by the heat of dumb desires that lurk slily in the depths and burn for fulfillment.

For you piety is only a means to a special end. You praise the glory of your Creator, follow faithfully the commandments which He has given you, but deep within you gnaws the delusion that some time, as a reward, understanding will come to you, and God will draw back the veil from before your eyes and reveal to you the meaning of His works.

Vain hope, old man! You are letting yourself be fooled by a dream which can never be fulfilled. Your gaze is fixed on an airy phantom, which glitters with a thousand brilliant colors but only lures you treacherously deeper into the desert.

Your God is jealous as a Mussulman; knowledge will never come to you from Him. He trembles before his own creature and already sees the day ahead when man will be able to revolt against His dominion. Then it would be all over with His divinity.

For this reason he blinds the mind of man and mocks his longing with a final goal that recedes farther and farther into the distance the harder he tries to overtake it. Thus man is like that being in the ancient fable, whose feverish eyes constantly see fresh fruit hanging close before them, but whose lips can never reach it. For thousands of years man has been held in leading strings, but he never notices how basely he is tricked.

You are on the wrong road, old man! If you wish for knowledge, you must knock at my door—

The voice ceases, a gentle rustling goes through the apartment.

Who speaks to me? inquires the old man, with trembling voice, and piercingly there sounds from a corner:

Who speaks to you? Man calls me the Power of Darkness because I stole fire from heaven to bring light to the sons of earth. He has called me the Prince of Liars because I first whispered truth in his ear.

One little word had its origin in my mind, the unpretentious word Why? With this word I greeted your distant ancestors as they stepped across the threshold that separates the human from the beast. The word bored into their dumb brains and sank to the bottom of their minds like a heavy weight.

Unending human herds threw themselves in the dust before a thousand gods, castigated their bodies, groaned in torment under the curse of sin. I was a witness of their anguish of mind, and merely asked the one word: Why?

The enslaved brood of men toiled in the sweat of their brows to build pyramids and citadels, which were to transmit the names of their masters to the latest generations. I looked on the madness of these serfs and asked them merely: Why?

Yet there were times when the word that lay there at the bottom of their minds suddenly burst forth in bright red flame. Then the spirit seized them. Gods plunged from their holy places, thrones tumbled in the gutter, and chains broke that had been forged for eternity. But this did not last long. The love of the lash lay in their blood, and their shoulders yearned for a new yoke.

Who speaks to you? I am the spirit that once showed itself to your mother in Paradise and implored her to stretch out her hand for the fruit of the tree of knowledge. I whispered in her ear: God doth know that on the day that ye eat thereof your eyes shall be opened, and ye shall be as gods, knowing good and evil.

Was it my fault that he thrust your parents out of Paradise like dogs, cursed the earth that it should not nourish them, and gave them over to slavery and death?

Once more the voice is stilled. A shudder runs through the old man's worn-out body; from his lips there sounds, dead and heavy:

Satan, it is you who speak to me. Are you trying to lead my soul into temptation, to trick me to my damnation? The keenness of your logic frightens me! And yet my whole being cries out to you. Do you not promise me knowledge and understanding? My old wounds begin to bleed; my heart burns again with tormenting questions; and desires that I thought had long been buried struggle up from the depths of my soul in burning eagerness. They burn me like consuming fire, and my soul writhes with their thousand torments. Will the hour strike at last of fulfillment of my yearning?

But they say that the devil can't be trusted. He does nothing out of pure good will. So tell me plainly and frankly: What do you expect for your service?

Very little, sounded from the corner. Hardly worth talking about.

As long as you live no wish shall be denied you. Whatever your fancy may devise, your heart desire, you shall never turn to me in vain. Time and space, death and eternity, shall lie unveiled before you, clear as crystal, and every riddle‘s teasing knot unloosed. You shall perceive the reason of all being and the well considered plan of events. Before your eyes shall the last frontiers vanish by which your mind has hitherto been held in check. Even your least whim shall be my law, and should the moment ever come when I fail you with my answer, then shall the bond be severed that binds you to me.

But when, some day, that last hour arrives for you when your vital strength is spent and your spirit feels prepared for its long rest: what happens then lies in my hand. For that you are to ask no accounting.

There is a gentle creaking of the ancient timbers, and soft shadows float about the flickering lamp. In the weary soul heaven and hell circle round and round and contend for victory. Then in the old man's eyes a hard light shines, and his voice rings firm as he says:

So be it: I am ready to accept your bargain. To know! To understand! Even for a little while! To gaze deep into the whirlpool of events and glimpse the basis of all being, which I have striven so long to see. Scarcely can I comprehend it: the long desired hour has come which brings me release! But I have always thought that that Savior who died for so many could never be my deliverer.

Of what account to me are death and resurrection, hell, time, and eternity, so long as my mind yearns in vain for understanding and my soul gasps in the anguish of desire! Is not this unsatisfied impulse gnawing at my heart worse than the worst pains of hell? Then it will be better for me to take upon myself the certainty of torment through eternity than to lurk forever about closed doors, never getting to the bottom of the riddle.

Satan, I am ready! One glimpse into the heart of the infinite outweighs all the pains of hell!

From out the gloomy background of the apartment there strides forth into the circle lighted by the lamp a tall, slender fellow, a cock’s feather in his hat, his body wrapped in a red mantle. The sharp features of his pale countenance seem as if carved with a chisel, and supercilious scorn plays about his thin lips.

Good, old fellow! Says he in a high-pitched voice. You please me. But I knew that you would some day come to me. You hardly fit in the other circle. A man who hides such depths within him is not made for God and his laws.

But now, up, and out from these narrow walls! Inside a moldering house the mind grows moldy too. If you want to grasp the deepest meaning of life you must traverse lands! you cannot keep your soul in fetters behind dusty windows and yellowed parchments. Out yonder laughs another world which will bring to your restless spirit the peace that it has longed for.

But before we leave this room, which has so often been for you a torture chamber, you must change your outer form. Age is the heaviest burden man has to bear. In an aged body the mind itself grows old. The truth that takes timid form in an old brain already bears decay within it; it is hardly born before it warns of worms and tombs.

Take this powder; dissolve it in water and bathe your head and limbs in it. You'll feel its effects quickly enough.

The old man does as he is bid, moistens his withered body with the elixir and can scarcely comprehend the miracle that has suddenly been wrought in him. The furrows that time has graven on his brow are erased by the power of the charm. Gone are the white beard, the white hair which a moment before had covered his head, and with them the slow decay which hourly warned him of his end.

A youth stands by the window, blond and strong. From his eyes glows youthful vigor. Youth flows like fire through his limbs, mysterious powers steel his every nerve. The whole world seems now so different to him; he feels the pulse of life beat in his veins. Titanic powers swell his breast. His fervent gaze drinks in all the splendor that lies about him; every sound that beats upon his ear thrills his heart like a maiden's kiss.

The first glimpse of dawn shows in the east as the two cross the worn threshold of the ancient house and the heavy door clangs shut behind them. With springing steps they hasten through the silent, dreaming streets of the city toward its ancient gates. Still drunk with sleep the aged warder opens for them a narrow door and lets them out into the open.

Now the city lies behind them, and they stride lustily up the little hill from whose summit one gets a glorious view across the land. The youth gazes down into the valley with intoxicated eyes, while his slender companion looks down, indifferent and bored.

Forest and field lie bright with the splendor of the new-risen sun. The lark soars, warbling, toward the sky, greeting, full-throated, the vast, beaming orb of day. From hedge and bush sounds happy twittering. Butterflies cradle on dew-covered blossoms, and from the neighboring wood resounds the cuckoo's luring call. In the vale the little stream goes babbling on its way, and yonder lies the ancient city, veiled in a softening haze: an enchanted world under the spell of slumber.

Nature has never seemed so lovely to him. He has never felt so strongly the unity of his being with all creatures. The heavy weight which through the years has lain on his soul has vanished, and his spirit floats in the blue ether like a boat on a placid lake.

Leisurely the two wanderers descend the other side of the hill into the valley and pace along beside the little brook, which, gently winding, pursues its way toward its distant goal, till their path leads them to a narrow bridge.

A girl in soft garments, with flowers twined in her golden hair, knowing a bare seventeen or eighteen autumns, stands loitering on the other shore; her deep eyes gaze guileless and innocent upon the two wanderers. The youth seizes greedily on the warming glance of those soulful eyes, and a feeling he has never known before lays gentle hold upon his throbbing heart.

Can this perhaps be love? He has never known before what love means. Love has always been for him a petty vice of weak-willed men who had no earnest purpose in life. Woman has seemed to him the epitome of sin and trivial pleasure, who drags man away from the path of duty and serious thought, wastes his powers, makes his existence aimless.

For this reason he has banished the other sex from his vicinity, so that no sinful desire should disturb his circles, cripple the pinions of his soul. No woman has ever crossed the threshold of that room in which he has spent the greater part of his previous life, alone with the clamorous thoughts which lurked in its every corner like timid messengers from unknown worlds. That was no place for idle pastime and relaxing lust.

But now as this maiden's glance burns into his heart a new feeling has come over him, that is in perfect harmony with the profound unity of his own being with everything about him. The impulse to tender confession, the longing for this unknown being, course wholesomely through all his limbs and shed a warm glow over his soul. His step lags. He casts a perplexed sidelong glance at the tall figure beside him, who has all the while been regarding him with ill-concealed mockery.

The milkface has hit you hard, he drawls. A trim little creature, by my faith! Still fresh as dew and appealing to the appetite. Put no check on your feelings. Never neglect what the moment brings you! Forward, my noble youngster! Don't be bashful! She'll not be stubborn, this young thing. Meanwhile I'll just draw one side for a while; when you need me I'll be at your service.

The young man hastens resolutely to the other shore, embracing the maiden's dainty form with his caressing gaze. His flattering words fall alluringly on her ear. Then she drops her eyes in shame and a hot glow floods her face. Now they seat themselves on a moss-covered stone in the shadow of an old elm tree and talk together intimately, like friends who have known each other always. Then their hands are intertwined, and their lips are silenced in a kiss.

But as the young pair silently rise and, still in close embrace, move toward the neighboring wood, they are followed by the malicious gaze of the other, who stands with folded arms on the other shore, and speaks in scorn:

O man, you pitiful creature, compounded of spirit and clay! The spirit always wants to lift him up to heaven, but the clay weighs him down to earth, so that he always crawls and always hungers. An odd fellow is man! Always on the quest for the philosopher's stone, yet when he feels knowledge close beside him he commits the greatest folly of his life. His mind revels in the quest of heaven, in dreams of the stars, and he does not notice that he is lying in the gutter like a drunkard full of new wine.

He, yonder, sat for seventy years in his house and dreamed of building bridges to the infinite, consumed himself in self-engendered torment, and would actually have driven himself mad, because his God would not take the bandages from his eyes and let him see clearly to the bottom of all riddles. He carried world-encompassing thoughts in his brain and often fancied that he caught the rhythm of distant spheres. With feverish gaze he waited for the hour when the dark curtain that had thus far hidden from him the meaning and purpose of existence should at last be raised. And as it slowly dawned on him that all his efforts were bound by space and time, that the mind could never succeed in grasping the reason for things, his heart was utterly crushed and his soul cried out to me in unnamable torture.

But today the lout is already cured. Now that he has tasted blood his great longing will slowly fade. His soul that once so boldly tried to scale the loftiest heights will content itself with the Mount of Venus. Instead of seeking for what lies behind all things, he'll learn what lies behind a woman's lap. And this lore will make him far more happy than the airy structure of ideas which he has spent his life in building, and to which he has never yet been able to give definite form. So the unsatisfied yearning and last hopes will fade out before the insatiable fire of lust, and attainable desire will blunt the urge for knowledge.

But he will never understand the nature of his folly. For even in little things his eyes are focused only on the remote and do not see what lies right before his nose. He boasts of his free will, believes himself the master of his fate, and is merely the marionette, dancing on threads pulled by obscure powers.

Now he is angry at his God because he has fooled him, kept him all these years in leading strings, and he does not dream that he has already gulped a new bait and is once more dangling on a hook. That he himself put out the bait, forged the new hook, like all the others he has bitten on, of course never enters his mind.

And yet this truth is so near to him. I and my brethren up yonder, what are we but creatures of his mysterious urge! His spirit created us, the sultry passion of faith begot us and flung us out into the realm of reality.

So the same game repeats itself forever and always ends in stalemate, since the cards are always equal. Whether God or Satan will in the end draw the higher trumps in this game is still an even chance and makes no difference in the outcome, for man will always be the stake.

The years fly by in the colorful game of time, and restlessly the two wanderers pursue their way across strange lands, over strange seas. Many a clever trick has the tall man performed. The dear public stretches its neck and arms whenever he sets his dark arts in play, crosses itself perhaps, and timidly gets out of his way.

He gets to know thoroughly the heights and depths of life, is at home with students, peasants, travelers; and even the splendor of the great is well known to him. At many a court he is a welcome guest, who charms the coin of God's anointed out of their coffers, beguiling them meanwhile with mummery and sleight of hand.

It really is no laughing matter for the tall man, for the whims of this fellow to whom his art has given a second youth are as countless as the sands of the sea. His head is filled with a thousand lusts and desires, and every wish becomes at once the father of a flood of other wishes. In this chaos of wavering ideas there is no resting place, no fixed point. Ideas whirl up and down in a mad chase, and are already dead before they are thought through to an end. It is a constant rise and fall of the emotions, a conflagration of restless passions, lacking all purpose, all direction.

What many years ago burned in his heart, the profound yearning for the reason of things, the burning urge for understanding, is long lost and buried. Only rarely in a silent hour does a soft voice remind him of times long gone. Then the old longing suddenly wells up, and shudderingly his spirit hears the rustle of distant worlds. But then the tall man quickly snatches him out of his dream with mummery and chatter. Quickly his mind is off on the new trail, and all his yearning vanishes painfully into the depths.

And so, unceasing, year piles on year, and for the second time old age softly announces itself. The hair bleaches, the eyes grow dim, and deep within yawns the great void.

Now the tall man leaves him more in peace, disturbs him less frequently in his meditations. A great loneliness seizes on his fluttering heart, and the path of life lies drear before his eyes.

Out yonder autumn drags wearily through the land, and the leaves fall, soundless, from the trees. Withered leaves whirl in the wind, the great death makes its way through field and grove. And in him, too, it is slowly turning autumn; only deep in his heart does there still glow a spark of that fire which once consumed him and drove him out of his native land to foreign soil.

As formerly, he sits today again at home and turns over in his brain thoughts that are dull and heavy. The autumn wind drives roughly through the night and shakes the ancient building as if in scorn. He sits at the window as he did so many years ago and wearily sweeps his glance through gloomy outer space. But today no distant star gleams for him out there, no moonbeam pierces the darkness. Black, like the abyss, yawns the sky above him. He feels as if walled in within the shaft of a well, and dark shadows rise out of the depths.

Now the game draws to its end, he murmurs. The tall, stealthy rogue, it seems, has slipped away. Just today, when he was to have rendered me an accounting, he has basely left me in the lurch. And yet what could he do for me in this hour? I can hardly endure his existence any longer. I have always been, in fact, alone, even when others joined me. Today it is doubly good to be alone, so that no mockery may disturb my last hours.

Now he is filled with the memory of quiet dreams. A soft note sounds from out the depths. Is it the gentle rhythm of distant worlds which he sometimes heard long, long ago, like the soft rustling of eternity?

A cool breeze fans his heated brow, and thoughts swarm swiftly up out of the depths. Clear as crystal seem to him the ideas that without effort shape themselves into words in his brain. Never has he seen so deeply into things.

Is this the final revelation? he asks timidly. The final revelation just before the end? It is as if scales fell from my eyes; the last illusion falls in fragments. Betrayed and sold a second time! And I felt myself so strong in my delusion!

They can fool a shepherd only once in his lifetime. But me, whom the world calls the great sage, they have tricked twice.

First it was God who kept me in leading strings, then Satan taught me behavior. And I, fool that I am, failed to recognize the contemptible game and felt myself the lord and master, when I was but the puppet of his will, the blind dupe of his imposture!

How great, how like a creator, I thought myself when with violent hand I tore the bond that had hitherto bound me to God! I would explore, spy out the core of things, bathe my spirit in the knowledge of all being. Thus have I sacrificed my soul's bliss, brought damnation through eternity on me, for a brief span of glimmering understanding.

Satan promised me that. And I, I, the fool, I trusted his word, moved at his beck like a simpleton, and never guessed that I was just the plaything of his whim. He promised me understanding. But instead of unveiling for me the meaning of life, the beginning and the end of all things, he offered me woman as lure to spend the hours in trivial dalliance, fanning my senses to flame, drugging my mind to silence. He reminted my soul into petty coin and clipped the wings of my yearning before I guessed his purpose.

But now the kernel of the riddle is revealed to me: God and Satan are of the same race, the two poles about which our life revolves. No Satan without God, no God without Satan! As twins born in the selfsame hour they bear, forged on them, the same yoke, and it holds them together till the end of time.

Man's life is lived within this circle. We drift eternally from one pole to the other, but never escape from the circle which holds us in its magic spell. And if it dawns on us in some luminous hour that one of them is merely making a fool of us, we promptly turn to the other for help in our hour of need, for savior and redeemer.

And he is already waiting for us, hands us the same stuff printed with a new pattern so that we shall not recognize the old goods. God and the Devil is the name of this old firm. One partner cannot get on without the other; it would be all up with their business.

As long as our mind revolves in this circle it will never be illuminated by the light of understanding. For understanding—I feel this clearly—lies outside the circle of God and Satan; but thus far no road leads to it.

For me it is now too late; I feel that my hour has come. My tired limbs yearn for rest. But my race will not die with me. As long as man still dwells on earth his mind will strive for understanding: till his brood shall perish in the stream of time.

Now the future lies clear before my eyes. There is a sound like distant organ music in my ears. It is the hymn of the coming generations:

Liberation of man by himself! Salvation by his own strength!

Far, far in the East there glows another sun which has never shone upon this earth! But now it's time; the last hour draws nigh. Already I can see the dark edge of the desert.

* * *

The heaven is gray. The desert yawns. A mighty sphinx of smooth black marble lies outstretched upon the waste of fine brown sand, her gaze lost in dreary, infinite remoteness.

Nor hate nor love dwells in that gaze; her eyes are misted, as by some deep dream, and over her dumb lips' cold pride there hovers, gently smiling, just eternal silence.

The first wanderer gazes into the eyes of the sphinx, but he can never solve her riddle; wordless he sinks on the desert sands.

II The Second Road

The road comes from Andalusia and has its beginning in the narrow streets of Seville, the city of love and adventure.

When the sun beats hot on the white walls, when no breath cools the leaves of the palms and heavy vapors rise from the earth, then Seville rests, relaxes her limbs, and waits for the cool breeze of evening.

But when the night comes down in silence, and a thousand stars shine from the river's depths, when the palm leaves rustle softly, and sweet fragrance floats from the gardens, then Seville wakes, sin strides soft-footed through the streets and wraps the entire city in her mantle.

From dark corners come the notes of mandolin and guitar and lover's serenade. A deep intoxication inflames the senses. The waves caress on the river's flood, flowers exchange kisses with the wooing wind, and fireflies betake themselves to a feast of love. The air is heavy with hot kisses. It seems as if the earth herself is trembling with fierce, passionate desire that wells, clamorous, from her every pore. High over the Alcázar's haughty walls shines bright the golden sickle of the crescent moon, emblem of grandeurs long, long gone. No God of Christendom has been strong enough to banish the ancient symbol from the sky. Though the brave Moslem horde fell in savage battle, crushed by the weight of the cross, the emblem of the prophet still shines from heaven, and its splendor is still mirrored in the rivers of Spain.

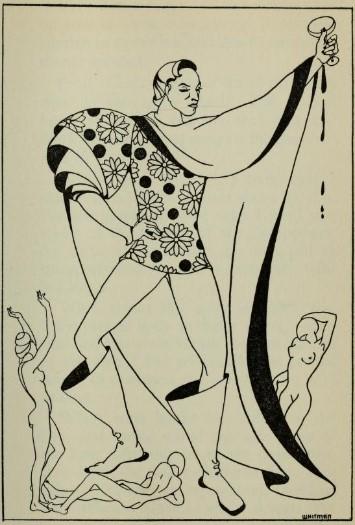

On this hot soil he was born. The passion of sin is in his blood, fills him with demoniac desire.

Black curls cluster about his proud head. Written on his countenance are rebellious defiance, tempestuous daring, which no law can hold in check, no sanctity can shake.

From his dark eyes glow the fire of hell, the bliss of heaven. But woe to the woman who falls under the spell of that glance; it sears her soul like a hot blast from the desert. The raging lust for sin leaps in her veins, her body is racked by fierce, feverish pangs, her every nerve cries out in passionate desire.

When, noiseless as a panther, he strides through the dusk, then is danger on the march, disaster on the prowl. Death hangs on his swordpoint, and it is terrible to rouse his wrath. When he appears, close behind him stalks dismal murder, the untamed passion of hell.

The dovelings in their nest are seized with a mysterious shudder, for no wall is too high, no bar too strong for him. The bars fall, the walls melt. No prayers, no tears help then. He does not stop halfway, and in his wake comes death and shame and the never ending torment of despair.

When he spends a night carousing with a circle of reckless topers, when the wine stands blood-red in the cup, he quaffs with it heavenly joy and earthly bliss. For every drop that goes coursing through his veins serves but to unloose dark forces in him that are subject only to their own law.

When in the wine he feels the fiery flow of truth, he begins to argue:

But all truth is but intoxication of the senses, and all intoxication but a dream. In intoxication we break the heavy yoke of hypocrisy, the arbitrary bound that reason sets to check the bold play of the senses.

When one of those well-bred prigs, like a trained poodle, is born, he knows at once just how to tell good from evil. He drips dignity, decency, and good morals, and struts like a peacock in the ethical feathers with which he decks himself out on holidays. He weighs every word cautiously, veils the nakedness of experience with prudish hand, and carefully cherishes each ancient custom.

He finds a meaning and a purpose in everything, and stinks of honesty and gentility like a plague-infested rat. He sets standards even for sin, and when he sins does so always in moderation, so that he may not forget his role. It sickens me to look at one of that breed.

But if one of those stodgy Philistines happens to forget himself and intoxication befuddles his tiny bit of brain, he sweats petty lewdness at every pore. All the curl comes out of his virtue; he wallows in filth contentedly as a swine. The thin veneer of convention cracks, his hard-won breeding goes to the devil and leaves in its place just a heap of nonsense.

But no sooner is the vapor of the wine cleared from his head than all the wretchedness of his humanity returns to him. Petty remorse pounds at his petty heart. The Evil One has surely tripped him up. As if the devil would bother himself over such trash!

A pitiful tribe, not fitted for the sublime art of great sin. What they call sins are merely the petty lusts of hours of weakness, easily satisfied and quickly forgotten. And when a lout like that does enter on forbidden paths he seems to me like a eunuch stammering ineffective words of love. He makes even sin impotent. In truth he knows none too much of sin, and the Savior's sacrifice rests lightly on him. What is there to save in a worm like that! But great sin, such as lures me, sin that strides naked and undisguised through life, defying hell, despising heaven, the sin that bows to no god and proudly scorns the laws set by men, it merely feels itself dishonored by a wretch like that.

But even more than to the fierce delirium of wine is he given to the mad sport of love. Here is his realm, the arena of his deeds. No means is for him too base, no sacrilege too great. With cunning, subtlety and force he labors to dupe female hearts. The strongest fortress melts and falls before the flame of his hot lust.

But hardly has his hand plucked the fruit that once allured him when he throws it carelessly away. When once his lust is quenched the pleasure fades for him, and his soul is off in quest of new delights. It is only conquest that attracts him, not possession.

His ear is deaf to prayers, to rage, to tears. And when his Victim cries out in anguish, implores him to safeguard her honor, give her his hand as he has promised, and so wipe out the shame that he has wrought on her, then jesting mockery flickers about his lips, and scornfully he dismisses her flood of tears:

Injured innocence, my child, lost honor? Let me tell you, that means little. The kingdom of my mind is as wide as the sea. How could I bind myself to one, while so many lips are still unkissed, so many blossoms not yet plucked! For one who knows how to prize the pleasure of the moment, the mad delights of a night of love, for him the price of honor is small.

Was I created for the bond of matrimony? A bond for traders and Philistines who were born with antlers already on their brows! They are content that their petty passion should be ruled by sacred law, should bear the stamp of a higher will than theirs.

A marriage bed! I shudder! It is the grave of love, the grave of sin! For love without sin is an insipid drink. For the honest burger it becomes an altar where he decently burns incense, deliberately increases his breed.

What wonder there are so many simpletons in the world! For one begotten in a bed like that carries none too heavy a weight in his head, and has blood that crawls but sluggishly through his veins. If it were not that by tricky chance a hawk once in a while gets into the henroost to lighten the good husband's task, the little pretense at a brain that this breed owns would long since have melted into slop. But adultery saves the race, and brings forth now and then a useful generation.

You can't grasp it, my child? You my your eyes out and keep dreaming of an early grave? Well, now, that really would not be the worst thing that could happen. For if one finds life too much for him he’d better see what death has to offer. It’s wrong to load on a man a burden that he can scarcely drag along. So, if one has drawn a blank in life, death’s sure to be a winning number.

If you're too weak to endure the fierce joys of sin, then take yourself to other fields! The stream, the silken cord, a sip of poison are prompt deliverers from the troubles of the moment and open the way from this vale of tears to the bright world you dream about.

No one should ever lift a human being who has stumbled. If one cannot stand on his own feet, let him fall! For pity is the worst of all the vices that man has invented! It dishonors the emotions, destroys the mind, and makes of men pariahs from life. Pity is rape with a mask on, a painted virtue that struts about the open market like a whore, extols the vilest selfishness to the skies, and is always secretly counting the profit that honest dealing brings the merchant.

It does not really help the weak; it merely shoves him deeper into the mire. But for those who by cunning lay hold on wealth and honor pity provides a soothing salve for their petty consciences. The thief tosses a few stolen pennies into the outstretched palm of a beggar and so smooths his way to heaven.

When once they spoke to him of that old man who sought for the reason of everything, who wished to see the depths of the flood of time, and burnt himself out in the driving urge to trace the ultimate truth, he laughed in scorn:

You old fool! What is the meaning of life, the beginning and end of all things to you? Life in itself has neither end nor purpose. It is man who thinks meaning and purpose into life. Past and future are chimeras: the first a fallen fruit, the second an unwritten book for which no title has been thought up.

What does it matter to me What has been or what is to come? What is left along the way over which we hurry is lifeless, dead and buried. What awaits us is not yet born. It does no good to burrow in the dust of tombs, even less to chase after soapbubbles in which the riches of the future glisten enticingly. Both take us into the land of ghosts and shadows.

Vanished glory is but rubbish, fit food for moths and worms. If you yearn for such a diet your mind grows moldy, and spiders spin their webs in your brain and trap your thoughts in their subtle net.

The fleeting moment is for me the truest friend; my kingdom is today. World history begins on the day when I first saw the light; it ends when I quench the last spark of my being in the womb of time.

Life is not here for one to comment on, brood over, and search through for a meaning which does not exist. Life should be for us a full cup from which to drink deep drafts with delirious desire. And when the cup is drained, the play of sense at end, then let‘s not whimper like spoiled children. Shatter the empty beaker on a stone!

You ask: Whence come we? Whither are we going? But while you wreck your mind, rack your soul, to find a meaning for the jugglery Of the senses, the hour has fled unutilized, unfathomed. For out of nothing have we proceeded, and into the vast nothing shall we vanish again; therefore take care that your brief span of life shall not be spent in nothing!

Your eyes follow the stars that whirl through space, and your lips ask dumbly:

Why? The soft note of the spheres falls on your ear; you want at once to fix their rhythm in dry words and lament when you do not succeed.

Fool! Can't you hear the rhythm that roars in your own blood? The exalted hymn of passion and sin, that ebbs and flows like the sea and rouses a thousand desires in your breast?

When I gaze into a girl’s warm eyes, I can see stars that have never shone for you. For the glitter of those stars I yield you freely all the galaxies of the astronomers, for these are stars that are wrapped in transports and tremble mysteriously with hot lust.

When errant lips unite in kisses, and body presses body in fierce desire; when time and the world vanish over the horizon of sin, then I feel profoundly the eternal reason of existence, the revelation of wild passion.

When wine blinks like rubies in the cup, and luring sound the sofe notes of the lute, inflaming me to yet new kisses, then I feel the final meaning of life. It is silly to live only in expectation, brooding over obscure riddles, while flowers are blooming by the wayside and with caressing nods speak of fulfillment.

And so the storm-lashed years slip past him. His path lies behind him like the red northern lights, strewn with the dying, who howl their curses through the woe-filled air. And graves show round on the fallow soil to tell where he has been.

Who can count the wounds his sword has dealt, bathed so oft in foeman’s blood, the women‘s hearts that molder, broken, on the way where he has passed? The wail of ruined lives follows his footsteps, and the sighs of the dying, solemn as funeral bells. Many a dead fist is clenched against him, and pale lips accuse him in fierce pain.

But he never gives a glance backward to look upon the past. He thinks:

What lies behind is gone, perished, swallowed by all-devouring time, and has no further charm for sensuous desire. What's dead is dead; eternity cannot give new bloom to what once has been.

And so the breath of death robs him who burrows about in ancient tombs of the power of action. For out of crumbling walls there rises only a pale band of ghosts. Remorse coils, snake-like, there to creep like a thief into heart and brain. And for him whom once this plague has smitten the grace of the present moment is forever dead.

Then let the dead wait on the dead. Who fixes his gaze on what has been, himself has been, a shadow painfully feeding on the fleshless figures of the abstract. His mind is like a mausoleum, hiding pale specters under marble.

Out of those vaults there rises longing for understanding, anxious inquiry for the reason of things. There dwells the spirit that sits enthroned on a grave and burrows like a body-snatcher in dead ashes until, completely enveloped in the fumes of decay, he no longer perceives the colorful play of the hour.

Very different is the lot he has chosen for himself. His pleasures never fall of themselves into his lap. What he enjoys with fierce sensuous lust must be conquered, must be wrung from life. The insipid gifts of chance have no charm for him; what he can seize without effort be values lightly. Only what he must win by battle, in the midst of danger and death, pleases him. He feels at his best when life and death revolve around his swordpoint; on paths where the foot loses its hold, the jaws of the pit gape for him.

Fate's lightnings flash around his head; his whole being is engulfed in storm. He sins on principle and desecrates because he likes to. When he strides like a demon on the brink of shuddery depths, or with sure foot scales precipitous heights, he feels a fierce joy in his strength and bids defiance to the powers of Fate. The blood dances wildly in his veins, and his soul flows in streams of fire, like lava gushing out of mysterious depths.

Proud as an eagle he soars aloft, drinking in freedom in full drafts. Only when he fights every day for life does he feel lord and master of his wish, boldly pursuing his course.

Now his glance falls upon a grandee's daughter, a woman than whom he has never seen one lovelier. The image of innocence beams from her eyes, and about the splendor of her proud body floats a dainty fragrance of chastity that strikes impious desire dumb.

But rarely does she set foot in worldly circles. She lives in a quiet sphere of her own, under her father's watchful eye, so that no alien influence may disturb her.

Here is a sport that will be worth while. To hunt down game like this is his heart's delight. That she is already pledged to another does but make the undertaking more alluring, heightening the wild intoxication of the sin. Not only does the mad lure of love beckon to him here, danger and ruin threaten also, defeat and death—just what he needs to spur his lust.

By deceit and cunning he finds a way into that quiet spot where she toys with flowers, dallies with birds, and follows with dreamy eyes the butterfly that flutters from flower to flower.

There stands the frightful being before her eyes, turning her young heart to ice. She stands as if rooted to the spot. A slight shudder runs through her slender body; then, in silence, she lifts her eyes to see who has dared to force his way into her world. The glow of anger kindles in her cheek, and her hand goes up in threatening command.

Then, at one glance from the strange man's eyes her proud arm falls powerless to her side. From those eyes glow the fires of hell, the boundless bliss of heaven. She feels the earth rock beneath her feet. A nameless horror grips her heart, her blood beats fiercely in her temples. Half dreaming she listens to words from far away which play caressingly on her young senses and speak of the delights of love.

In desperation she strives to collect her strength. Her father's blood flows in her veins; the honor of a grandee surges swiftly up to quell the impetuous impulse of her senses. Hark! Is that not her father's voice now ringing in her ears?

And then she feels again that frightful glance, that strikes into her soul like a bolt of lightning. Hot lips are pressed against her lips, a soft farewell sounds in her ear, and like a shadow the figure vanishes.

For a long time she stands as if spellbound, then she feels her strength slowly fail her, and she sinks, moaning, on the marble bench. As from a distant world the gentle plashing of the fountain comes to her to still the wild beating of her heart.

Then once more she hears her father's voice. Men's footsteps sound along the path, and loud voices fall on her sensitive ear. Here comes her father, arm in arm with the man whom his will has chosen for her spouse. A chill strikes to her heart and wrings a dull moan from her breast, while her soul writhes in silent anguish.

Has the world gone suddenly mad, the meaning of things turned round? This man to whom her lips have sworn fidelity seems suddenly so strange. And again she feels that hot glance which glows like a firebrand in her bosom, and unknown portals stand open of which her simple heart has never dreamed.

Gently the old man takes her soft hand in his and speaks in playful jest:

Dreaming, my child? Well, this is the right time for dreams — the dreams of youth still burdened by no weight of duty.

There is a profound meaning in God's setting of age beside youth. If youth soars boldly in the realm of dreams, then age must see to it that the dreams come true.

And that's just what I have done, my child. Before the autumn comes again you will be leaning on your husband's arm.

Your dream will have been fulfilled.

Her father's words fall like a dirge upon her ear. Her heart throbs in torment, but her lips dutifully thank her father, who gleefully bestows his blessing on the youthful pair.

The wedding day has dawned. The golden disk of the sun gleams from a cloudless sky, and bells peal gladsome welcome to the feast of joy. A crowd of guests throngs the count's palace, speeding the time in cheerful sport.

The organ peals from the chapel, and the priest's words solemnly unite the noble pair. But as the lovely bride's white hand is placed in the strong hand of her spouse and a yes that can scarce be heard struggles to her lips, she feels again that Satanic gaze that floods her soul with fire. Like a sudden flash of lightning the gaze envelops her for a moment, to vanish at once into profound darkness.

Her slender body trembles in silent horror; her brow feels cold, as with the death-sweat. She feels the curse of Fate upon her head and steals confused glances at her husband, whose eyes are blurred by the transport of his happiness.

She struggles with all the strength of pride to shake off the spell that enwraps her heart. The blood of grandees flows in her veins, and this helps her to fight against the sinister power that has so wantonly thrust itself into the circle of her life.

Then a great calm steals over her, but a coldness of the grave within her heart warns that it is the calm before the storm.

On her husband's arm she proudly enters the great salon. The paleness of her countenance does but enhance her charm, and all eyes hang speechless on the picture. Then a mighty shout of jubilation fills the hall, and a hundred goblets are lifted to pledge her health and joy.

With gentle grace she bends her head in greeting to the joy-filled throng of guests. Now joy is unconfined. The lofty hall resounds with sounds of happiness; wine sparkles in splendid beakers, and cheerful voices fill the air. A mild intoxication lays hold on heart and head; the youthful pair lose themselves in the delightful tumult, and every heart is filled with bliss. Desire unconfessed shines from glowing eyes; the whole world seems born anew; each guest feels coursing through his veins the swift blood of youth.

Thus hour after hour takes its happy flight, and outside night has long since spread her pinions. The hour arrives when the noble pair make ready to take their silent departure. The husband's eager eyes embrace his young bride's lovely form, and he whispers to her tender words of love.

A soft blush reddens her pale cheeks, she tries to avoid her bridegroom's gaze. Then a sudden pang shoots through her soul, and, as if drawn by some sinister, compelling word, her gaze turns toward the middle of the hall.

Leaning with folded arms against a marble column, as if himself carved of stone, she beholds the stranger who had dared intrude into her sanctuary. His eyes, fixed on her, glow with an ominous fire. His gaze seems to cast a spell on her; the gates of hell open before her, and tongues of flame leap at her from the depths. The red glow burns her eyes; it seems as if her heart must burst; her trembling hand is crushed against her breast.

Her stern pride has been abruptly blown away, melted before the ardor of his gaze, that draws the blood out of her heart, fetters her soul in thousand-linked chains.

And then she feels her petrifaction melt, a wild desire fires all her senses. She feels a mad impulse to shout: It is not this man beside me whom I married! No, he yonder, who strips bare my soul—he it is, for whom my heart throbs!

No longer does she strive to fight against her destiny. She knows her fate stands yonder, a messenger of doom from Satan's realm, who is luring her soul out with his daring lust. She feels the blood surge back into her heart, her breath stop, her strength fade. Quicker! Quicker! Why does he wait so long? She can bear this deadly pain no longer!

As if the stranger had sensed her anguish, he suddenly leaves his place and strides assuredly toward her. He sweeps the bride-groom with a contemptuous glance, then, in a low tone, asks to speak with him. The bridegroom stares at him uncomprehending, but, impelled by some inner force, follows him to the center of the room. There he hears words that make his blood boil. His heart throbs fiercely, but he tames his pride and merely waves the bold blasphemer in silence toward the door. But the latter looks at him with unspeakable scorn and flings in his face an insulting word. Then swords flash in the air and there resounds the clash of steel on steel. A deathly silence fills the vast hall, as if horror had frozen every heart. All eyes follow the grim game in which life struggles against death.

A cry of agony bursts from torture-torn lips. Pierced through the heart the bride-groom sinks to the floor, and the stranger stares with gloating eyes upon the foe whom he has struck down in the fullness of his youthful strength. Then he walks calmly through the silent hall and strides through the wide portal into the night.

Pale as a marble image sits the noble lady, staring with lifeless eyes upon the silent man, whose heart's blood gushes out in libation to his wedding day. Before her gaze yawns the depth of the pit; she feels the unknown touch of death, feels her young heart congeal to ice.

Only slowly does the cold spell of horror that has quenched all life within the hall dissolve. Shrieks and moans are heard, a wild turmoil of voices; and what pale fear had at first repressed now pours out all the louder.

The aged father, who, withdrawing from the guests, had retired from the hall, to wait for his child in a quiet recess and press her to his heart once more before she leaves him, re-enters. The outcry of the guests has called him forth. He sees his daughter's horror-stricken gaze, the dead man lying there on the floor, staring empty-eyed at the ceiling, and from the disconnected words of those about him gathers what has happened.

Then the old man rushes out into the night to overtake the desecrator who has cast dishonor on his house, cruelly shattered his happiness to ruins. A few friends from the throng follow him, and the wild chase through the narrow streets is on.

In a silent square, lit faintly by the moon, they glimpse the dark form of the stranger.

Halt, coward! calls the old man in a thunderous voice. Draw your sword, so that I may avenge the shame that you have done my house!

A coward—I? Old man, you are out of your senses, mocks the other. It would be better for you to practice calm. Your arm is no longer strong enough to enforce atonement. It's unbecoming at your age to strut like a barnyard cock.

The old man's sword leaps from its scabbard. Now the mocker too, must draw. The blades clash sharply in the moonlight, and blue sparks fly from the hot steel. The old man knows how to wield a sword; not even the meanest envy can deny him that. But about the stranger's blade plays death itself, and he is invincible as hell.

A dull thud, his blade falls from the old man's hand. And while his friends bend anxiously over him, the despoiler vanishes swiftly into the night.

The months fly by. They rarely speak of the wedding feast of death. In the churchyard of Seville there is a new monument bearing the marble image of the count. He stands there, pale, hand on his swordhilt, eyes raised toward heaven. From on high the moon's rays shine down and flicker softly over ancient graves. The count's likeness gleams, spectral, in their light, and the stern folds about his mouth seem sterner still. He stands there like a symbol of vengeance, an ambassador from the dumb realm of ghosts.

Then soft steps sound on the path. Out of the dim shadow the stranger steps briskly and gazes with grim scorn upon the image of his victim.

How goes it now, old chap? he scoffs insolently. Does one get bored in the realm of ghosts? Is there no wine there, no mouth to kiss: does no lute sound for the carousing throng?

I'm sorry for you, but it was not my fault. Your frenzy forced me to the fight. But what is done cannot be changed, and it would be useless to dig up things again. But just to let you know that I bear you no ill will I invite you to a banquet at my home tomorrow night. A well-set table, the best wines, and lovely lips to kiss. What heart can ask more! That should be enough to move a marble statue. You'll come? You accept my invitation?

A quiver runs through the cold stone, and on the white forehead shines a threatening glow. The white lips move gently, and as if from the depths of the tomb there falls on the scoffer's ear: I shall come. Be prepared!

He stands bewildered, rubs his eyes.

What was that? Did someone speak to me? Is wine making a fool of me? Are my senses tricking me? It seemed as if the dead man accepted my invitation.

That would be a joke! A guest of marble at a feast! All right, I'll be prepared to receive him!

The room is bright with the light of candles, the sweet tones of lutes fall enticing on the ear. The table is spread, but the guests are still lacking. For outside a wild storm is raging. From the black heavens the lightning darts a thousand bolts, and crashing thunder roars incessant through the room. It is as if the elements were in conspiracy. The air is sultry as if charged with fire. One feels the flames about one's heart and mind.

The stranger presses his forehead against the panes, illumined by the lightning's glare, and feasts on the mad play of nature. To him it seems a Bacchanal of sin, this savage sport of the wild elements, and his heartbeat quickens in his breast.

Thus hour after hour vanishes, and ever fiercer grows the fury of the storm. Midnight is close at hand, but still the hall is empty. No guest comes to enjoy the festive display.

At last he seats himself at the empty table and signals to a servant to bring the food:

Wasted effort! No guest will cross my threshold in a storm like this. But what can't be today will be tomorrow. So for this feast I'll just be my own guest. Your health, my friend! Your very good health! To Sin and Freedom, this first glass!

Just as he proudly sets the beaker to his lips the church bells peal the hour of twelve. Then heavy footsteps are heard through the tumult of the storm, and the great entrance gate springs open with a shriek of its hinges. And now the steps come threateningly along the path and a heavy hand knocks at the door.

The servant stands, turned to stone beside the table, gazing in silent horror toward the portal. The master must bestir himself to admit this tardy comer to his banquet. With steady hand he throws the door open; on the threshold stands the statue of the count.

You invited me, says a voice fit for the grave. Well I am here. Do you shudder at my visit? Does remorse seize on your false heart? The dead never break their word.

You are welcome, noble sir! It is a very signal honor for me to receive you in my house! Be seated! But be careful, my chairs were not designed for guests like you. May I be your cupbearer? This is good wine. You've never tasted better!

I am not here to carouse with you. The voice again seems from the tomb. He who has entered the realm of shadows feels no more desire for food or drink. I have come to end your impiety, an avenger of the God whom you have so insolently scorned.

Do you see the wild uproar of nature, the lightnings of heaven that play about your house? Do you hear the roll of thunder above us? It is the wrath of the Creator, who demands an accounting for the countless crimes with which in savage ruthlessness you have burdened your soul.

Every gust of wind carries the curses of your victims, the death rattle of those on whom you have trampled. Love betrayed proclaims your guilt, broken hearts accuse you before the bar of God. Your hours are numbered. Use, then, the fleeting seconds to save your wretched soul. Repent, transgressor! Confess your guilt! Let remorse o'erflow your breast, so that you may find mercy in death!

Not badly spoken for a marble image, came the shameless answer. It seems they know the value of rhetoric in the realm of shades. But you have brought yours to the wrong place. I am not appalled by my deeds, and I am prepared to pay the full price of every rich, sinful joy. And so I laugh at any retribution in the future and I scorn the curses heaped upon me!

Ha! What if it be true that a judge waits for me sometime to demand accounting for my acts! I shall look him fearlessly in the eye and mock at his omnipotent wrath! If he is the great creator of all that is, then sin is a thing of his creation. And if my acts are not pleasing to the Creator, then all creation is just a bungler's whim! One knows a master by his work.

When, once upon a time, God made man out of the dust of the ground, then he breathed the breath of life into the lifeless clay and took no thought that life is spirit and spirit is mind, a law unto itself. His creative word commands the lump of clay, but never the spirit that he engendered. The body he can mow down with the sickle of death, but the spirit lives on even in the grave and leaves its heritage to coming generations.

It is my spirit that kicks against the pricks. He can crush me in blind fury, but he can never tame my spirit. He can destroy, but not subdue! The spirit creates its own world and scorns divine powers. On the very brink of the grave it sets up the banner of revolt.

Cease, insolence! the dead guest interrupts. I now see clearly that not hell itself could silence your defiance. God could crush you like a worm, but the poison of your scorn would splash to heaven from the utmost depths of hell. But the day of judgment will sometime come for you. When the vital strength dries slowly out of you, and mind and body weaken with the weight of years, then your impious mood will quietly desert you. The life that burns so fierce in you today will one day be the avenger of your deeds.

That's a long while yet, mocks the other. Before the snows of age have whitened my hair a blade will have pierced my heart. Still not even the years could crush my defiance.

No, you will live, the pale guest says. No sword will shorten your career on earth: Fate will be a buckler for your breast. Live, then, until your time shall be fulfilled and your hour of bitterness shall come!

With heavy step the grim guest leaves the house. The storm howls wild, many a tall tree is shattered, but the marble image strides unfeeling onward through the horror and the night, the lightning playing spectrally about it, till its steps die out in the distance.

Year follows year down the corridor of time. The glory of the spring follows on gray winter; cool autumn damps the summer's heat.

Like a storm cloud from which lightnings flame, the wanderer moves boldly along the pathway of his destiny. It almost seems as if the years put steel into his will, enflamed his senses to fiercer glow. Like a demon he hovers over the depths of the abyss, but no dizziness causes him to falter. He rushes in mad passion from indulgence to indulgence, boldly holding aloft sin's storm-lashed banner, while death and hell follow in his steps.

Now he has once more tricked a woman's heart, and in the silence of the night is on his way toward his loved one's well-guarded bower. In the garden a nightingale trills her song, and heavy odors drift through the window. The mild summer night is intoxicating, laden with the feverish glow of hot kisses. The woman's bosom is fiercely pressed against his breast, and she moans as she drinks in his fiery kisses. Onight of love, filled with secret sin and wild desire, ah, that you might never end!

The hours speed by in swift intoxication, already the east is graying with the pale light of day. He rises from the downy pillow, embraces in a mournful glance the lovely woman who lies there wrapt deep in dreams.

Sleep softly, says he in playful mockery. Your hour of waking will be hard. And so it's better that I should take my leave while sleep still binds your eyes. It is always the same old song, the biting words of deep remorse, the hot flood of bitter tears, shameful tears.

But as he now turns quickly toward the window, the mirror shows him his full image. Smiling in satisfaction, he raises his beret; and then a sudden shudder shakes his body, for in the dark splendor of his curly locks he glimpses the first strand of white.

A white hair, the harbinger of approaching age. It sinks like a gloomy shadow into his soul. He is aware of the soft wingbeats of time: but swiftly he tears away from the image and safely and lightly swings himself from the balcony.

But the thought will not leave him now. It bores deep into his mind and lurks, silent, in the abyss of feeling. It sits like a specter in his brain, and if for an instant the memory slips away, knocks softly on the thin wall to bring it back.

In vain he tries to lay the ghost.

Fool, he tells himself, why worry about things that still lie hidden deep in time? The present is what you call your kingdom, the fortune of the hour is your star of destiny.

The sound of the lute still lures, and wine, and love. If you would taste the spring, then think not on the autumn! Each instant lasts a thousand years! He is a coward who does not seize the hour!

But the memory will not leave him. While he sits carousing with a gay crowd, he will suddenly remember that white hair. He sees the snows of age upon his head, the watery glance of bleary eyes—and the wine in his cup turns to gall.

When in hot desire he embraces the soft body of a woman and kisses her moist lips the thought darts in fierce passion swiftly through his brain and quenches his desire.

Does the harp call him to the joyous dance the recollection steals into his heart, and the music turns to dirges in his ear.

A funeral march, he tells himself, guiding a dead man to his tomb. This seems to me my funeral train: I'm following my own coffiln—

So be it! The great autumn nears. Age may perhaps turn transports into gall, but no autumn shall tame my defiance.

And so he steadily pursues his path of destiny through distant lands, over distant seas, till he sees the last frontier there before him—

* * *

The heaven is gray. The desert yawns.

A mighty sphinx of smooth black marble lies outstretched upon the waste of fine brown sand, her gaze lost in dreary infinite remoteness.

Nor hate nor love dwells in that gaze; her eyes are misted as by some deep dream, and over her dumb lips' cold pride there hovers, gently smiling, just eternal silence.

The second wanderer gazes into the eyes of the sphinx, but he can never solve her riddle; wordless he sinks on the desert sands.