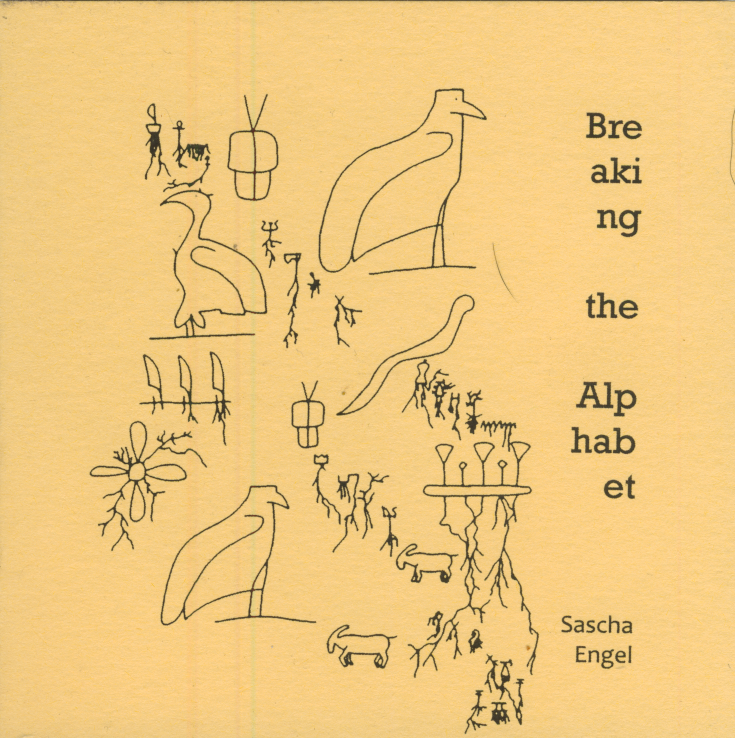

Sascha Engel

Breaking the alphabet

1. Writing the planetary trap

At the heart of civilization’s discontents is writing: authoritarian iteration. Inscribing itself into the continuous unfolding of the world, writing severs connections and solidifies the axioms of identity, solidity, and temporality.

The repetitive reification of authoritarian iteration is at the heart of the “monstrously wrong turn...from a place of enchantment, understanding and wholeness” to “the ruin of civilization that ruins the rest” of all land and creatures, and that now even grabs other planets. [1] That it is at the heart of the many facets of the catastrophe is plain to see. Writing creates and solidifies social formations everywhere. Social through and through, both the surface and the supposedly neutral, supposedly biological core of gendered and racial identities are based on authoritarian iteration. They build on iterated gestures, whether these manifest as behavioral expectations or in the supposedly natural iteration of ostensibly biological characteristics. Invoking now the one, now the other, authoritarian iteration further creates and solidifies divisions of labor, deadening flesh and spirit by forcing them to iterate the same roles and gestures over and over.

Writing creates and solidifies compartmentalizations in our heads and boundaries on the land. Each living entity we encounter is subject to “some sort of coding-process” “interposed between received signals and symbolic representation”; each gesture we make is governed by “the outward-directed activity of the elements organizing the internal matching-response.”[2] Thus written civilization is technical civilization, written by iteration, operated through iteration, and consisting exclusively of iteration. [3]

What we commonly call ‘a tree’ is, at first, a living complexity, a constellation of branches and wind, sun and leaves, soil and roots; a joyful assembly of living adhesion and dead wood, in constant continuous unfolding together with mycelia, worms, birds, and ourselves. Yet authoritarian iteration decrees its sameness, iterating tree after tree after tree in perfect congruity as ‘lumber’ or ‘nature reserve’ or, more perniciously, as ostensibly value-neutral classification in difference and comparison to shrubs or bushes. And so the world comes to be full of identical trees, paving the way for ‘conservancy’ and ‘forest management’, rather than remaining a wonder of living complex constellations.

The same happens with those mothers, daughters, fathers, and sons out to pasture, those constellations of gentle wisdom quietly grazing or playfully jumping, or lovingly giving sustenance. They too become iterated ‘cattle’, and the whole misery of their cramped and brutalized half-lives in cages, bereft of warmth or rest, and killed without mercy, stems from the authoritarian imposition that cow equals cow equals cow and hog equals hog equals hog, each a mere iteration. Only by virtue of this can they be further dissembled, at first analytically and then materially, as each terrified individual is dragged into a “mass transition from life to death,” the mechanization of killing resulting in mere rows of identical iterations, “each animal hanging head downwards at the same regular interval” in the abattoir. [4] It stems, in other words, from writing: replacing each living constellation with an iterated, solidified, reified abstraction.

The Earth as a whole, too, radiates the imposition of iterated authoritarianism, of writing and overwriting all living constellations until they can be delivered to the abattoirs of industrial civilization. All of it is so much ‘soil’, so much ‘arable land’ and ‘real estate’. Nor has civilization ever been capable of looking at it otherwise. From the time of the Romans, these Euro-Americans of Antiquity, iterated authoritarianism has ordered us “to fix the boundaries and to cause boundary-marks to be set up,” and to remain subject “to the conditions on which...boundaries were to be fixed.” [5] The land and its creatures are property and nothing more. My relation to them is one of ownership – or exclusion – and nothing more.

It may thus seem that every living constellation and “the whole earth bears witness to the glory of man” and that, “in war and peace, arena and slaughterhouse, from the slow death of the elephant overpowered by primitive human hordes with the aid of the first planning to the perfected exploitation of the animal world today, the unreasoning creature has always suffered at the hands of reason.” [6] Yet this ‘glory of man’ and ‘reason’ and their boundary-marks, too, which are cut into land and creature, are also cut into my flesh. I, too, iterate the triumph of authoritarian iteration. My flesh creaks when the alarm forces my muscles to iterate the morning routine, my eyes are sore from iterating contraction and expansion at the behest of screen and contact lens, my gestures are domesticated under the weight of fake individuality. From jobs and bank accounts, through identity papers and advertising profiles, to iterating the authoritarianism of personhood in schools, hospitals, barracks and prisons, playing my roles for capital and state, I, too, am merely written: am merely a human producer/consumer.

Indeed, iteration even inscribes itself into the shapes of letters, turning them from joyful splotches – shapes and drawings dreamt of before school starts disciplining and punishing – into iterations of rules and enforcements. When I write, my muscle memory is forced into the tired forms of standardized letters, drawing the same legible shapes and forcing the same uniform expressions each time. Handwriting is word processing. Typing this, too, I merely implement iterated muscle memory, disciplined by the word processor. And were I to swipe these sentences on my phone, autocorrect would keep it all under its watchful gaze.

And yet, there is something bare-faced, something vulnerable about the frantic efforts by which literacy is enforced from ever younger ages. Every letter reinforces the abstract rule of iterated authoritarianism on letters and their writers’ muscles, just as every written word in turn drives the final nail into the coffin of undomesticated perception. And yet there is something frantic about the enforcement of schooling, something different from the casual cruelty of every other authoritarian imposition. Literacy is more hectically reinforced and its supposed loss more frantically opposed than many other axes of civilization’s tyranny. Is this perhaps because letters contain more than it seems?

Perhaps learning how to write letters is most openly and nakedly the point where iteration itself is at stake. Perhaps it points to the essential and primary movement from joyful exuberance to monotonously iterative drudgery. “The repetitive nature of patterns,” with which children start to learn how to draw letters, “emphasizes the rhythmic movement which we aim for when writing.” [7] This tames the childrens’ muscles, helping to “maintain consistency of size” of letters as well as “consistency of slant” in holding the pen, and serves to “keep letters on the line.” [8] To be sure, the teacher should start out to “encourage children to have fun with making patterns” on a “wide variety of materials” at first. [9] Yet the goal remains to “control the small muscles of the body,” engendering “motor control” as well as “perceptual skills.” [10]

And what if the children don’t learn how to write, or – like Marx – develop their own idiosyncratic handwriting? What if they were to rebel and invent their own keyboard strokes and phone keyboard swipes? Horrified panic. At the time of writing this, the National Guard is in schools in multiple American states to offset a teacher shortage – real enough, by the way, due to woeful underpayment and casual neglect of a raging pandemic... Likewise, the lingo of anyone under 20 is under constant suspicion of bringing forth the imminent end of civilization. (If only it did!)

Nor is this a new panic. As early as 1986, Theodore Roszak’s otherwise avowedly ‘Neo-Luddite’ treatise worried that literacy is “an indispensable but now endangered faculty of the mind,” counseling that democracy (whatever that may be) cannot be maintained unless libraries “surround the computer with a greater culture that disciplines its excesses.” [11] As though it is more discipline that is needed...

By the same token, calls for a return to cursive writing, or statements bemoaning lost arts of handwriting, or invitations towards mindfulness through calligraphy are symptoms of a panic barely contained beneath the slick surface of their neoliberal purveyors. They, too, present more discipline as a response to a perceived lack of it. Cursive writing and calligraphy, in their own ways, are just as standardized as printed letters are. Appeals to them are inherently conservative – whether explicitly or not. Yet they indicate an obsession of our societies with literacy. Why the widespread bemoaning of an apparently outdated skill? Why the crocodile tears over waning literacy? Is there perhaps more at stake? Do the defenders of civilization perhaps feel, on some level unknown even to themselves, that what lays bare here is far more than just another axis of domestication – that iteration itself is at stake in the minuscule letters formed by childrens’ unsteady hands?

2. Lettered domestication

As even defenders of civilization feel, albeit unknown to themselves, writing in the conventional sense, by hand, as cursive or calligraphy, or typing or swiping letters, is the archetypal example of authoritarian iteration. Yet the letters are themselves subject to it, just as the humans drawing them are. The same gestures that grasp animals, plants, planets and stars grasp humans and letters. Yet by doing this, they uncover the basic axis of iteration at work in civilization. Is this axis necessarily there? And if it is, is its iteration necessarily authoritarian? Can there be ways to write without iterating authoritarianism?

Within this civilization, where violence is at once planetary in its reach and granular in its complexity, extending from the deepest nooks of our bodies to the furthest reaches of Moon and Mars, it is easy to conclude that iteration is necessarily authoritarian. When John Austin inaugurated the philosophical consideration of speech acts, his account of them included two elements right from the start. Every speech act, such as the ‘I do’ at a wedding, the ‘I name you...’ at a ship’s christening, the ‘I hereby...’ of a will or a deposition, or for that matter the execution of a deed or a criminal, arrest or conviction, is first a formal iteration of certain words, and second an iteration which only functions in a given context. Both the statement and the context are thereby reified. The ‘I do’, uttered in the wrong context, is an ironic allusion or a blatant joke. Conversely, if bride one says ‘I do’ and bride two responds with ‘what’s for dinner’, context alone won’t save the ritual. Both must be iterated.

Right off the bat, therefore, Austin distinguishes statements that work from statements that do not: if context or speech are off the mark, the speech act fails. Every speech act therefore contains its own policing principle and yardstick. And what’s more, each such speech act is the yardstick for the reality it creates. Is the contract valid or void? We know because it conforms to the iterated notion of a contract, or not. Is the marriage proper or a sham? We know because it conforms to the iterated notion of a marriage, or not. Does the ship have a name or not? Well, check the hull: are the letter legible, do they iterate the ones you know? Or if not, can you use your phone to translate them into ones you know?

Contractual society is full of these speech acts, each with their own yardsticks. Anyone who thinks about this will be able to multiply the list of such speech acts indefinitely. With each, a part of contractual society is created and maintained by iterating the speech act and its circumstances. To understand the full extent of the reign of iteration, however, we need to go beyond Austin’s anemic analysis. The mechanism of iteration is particularly obvious in contracts and marriages. But it is at work in the heart of every statement, not just those that create contracts or marriages. Trees, cattle, humans, letters, too, are created in this exact way, each using their own yardstick of reified signage in reified contexts.

Just as the brides completing the wedding are no longer living constellations but contractual signatories once they are overwritten by the context of marriage, so the trees and cows are no longer living constellations but units of lumber and cattle once they are overwritten by the context of seemingly objective statements. There is no difference between being the subject of a speech act and the object of a descriptive sentence. In both cases, speech and context are severed from the continuous unfolding of the world and are instead reified as so many instantiations of the context and speech act which they iterate. The statement that this tree is the same as this tree is the same as this tree doesn’t describe trees, it creates them. Likewise, the statement that this human has rights, same as this one and this one, or conversely that they do not, doesn’t describe humans, it creates them.

Nor does it matter whether this iteration is effected through the agitated muscles of speech, moving air, or the agitated muscles of hands and arms, moving ink or cursors. Both are “linear, successive, substitutive,” and neither can be “open to its whole object simultaneously.” [12] Speech, too, is writing: authoritarian iteration.

Nor could we fall silent and retreat into an inner sanctum somehow untainted by iterated contexts and speech acts. Reducing the world to a mirage created by demons and retreating into gnostic revelation, or else projecting utopian ways out of civilization through revolutionary collective action: both fall prey to writing in equal measure. To be sure, regarding speech as even more so letters as derivative forms of thought, and ascribing to the latter the power of escaping domestication is a foundational gesture of so-called classical anarchist thought. This looks forward to “no war, no crimes, no administration of justice as it is called, and no government” just as soon as “Mind will be active and eager” to “see the progressive advancement of virtue and good.” [13] Yet what are ‘virtue and good’ other than the iteration of pious authority, “a system of principles defining what constitutes right and wrong behavior” from an imaginary vantage point which “always stands outside and above the living individual”? [14] Which is to say: the vantage point of an authoritarian imposition writing our thoughts in so many blueprints, just as it writes our speech, writes our gestures, and writes the whole world. Thought, too, like speech, is no refuge. It, too, is domesticated, is iterated – is written.

3. Authoritarian iteration

Nonetheless, the frenzy about schooling and literacy, about handwriting, letter swiping, calligraphy, means something. Envisioning the iterations of reified context and speech acts in the innermost crevices of our thoughts and the outermost minuscule capillaries of society also entails envisioning the seeds of resistance which are nonetheless growing everywhere. Nor are these seeds an unpleasant but undeniable empirical fact getting in the way of a unified theory. Rather, it is writing itself – empirical, everyday writing in the conventional sense, from the flickering signifiers on our phones’ screens to the most elaborate calligraphy – that provides the starting point for iteration’s – and civilization’s – undoing.

In everyday writing, iteration becomes explicit, allowing us to distinguish between its authoritarianism and the unfolding of the world which it overwrites. That is, everyday writing exposes that iteration is necessary for the imposition of reified contexts and speech acts, and thus shows us axes for working against this imposition. Everyday writing demonstrates that writing a ‘tree’ into the world, just as writing the word ‘tree’ into the world, need not leave a permanent wound. From the vantage point of Austin’s anemic analysis, which in this point iterates the no-way-out attitude of civilization, it seems that authoritarianism within iteration is unbreakable. Yet they can in fact be subverted.

To get there, we must take one more trip to the heart of authoritarian iteration. How do I come to codify a tree as a tree, a cow as a cow, a human as a human? How, too, do I come to write the tree as a not-shrub, or the cow as cattle, or the human as a person? Observing ourselves, we conclude – and this is how it’s usually been concluded – that such an act of reification stems from the iterated association of the word with the thing. Thus what is typically described as ‘recognition’ is, as we’ve seen, a prescriptive act rather than a descriptive one. The ink marks forming the letters t-r-e-e, and the sound waves forming the word ‘tree’, write the tree into the world.

How do I come to make this association? When I encounter a constellation of surfaces and colors, sounds and smells that I have never encountered before, I encounter it as a gap within a continuity of things whose names, places, and functions I know. The new constellation startles me because I already live in a continuity of discrete things rather than a continuum: in a civilized world filled with discrete things that has discrete names, proper places, and orderly functions. The new constellation is thus at first an unknown intrusion, something literally out of order, something – potentially – feral. It is a reminder that the world unfolds continuously despite civilization’s best efforts.

And these best efforts kick in right away. This new constellation is immediately defined by its being ‘out of order’, and is thus negatively constituted as a discrete entity again, as it is the only section of my world without an iterated definition. Without delay, the murmur of domestication closes in over it. It asks – I ask – what this might be? What is its name, what are its characteristics? What functions does it serve? What profit can be made through it? How does it relate to my struggle to survive? In other words, I ask of what type it is a token: what letters and what speech does it repeat? Writing it as a discrete thing into the world, I ensure that it is a known entity, something iterating something else.

Thus iteration assimilates the constellation and writes it as a repetition identical to something that existed before, or broken down into units of something that existed before.

And yet, here lies the peculiar weakness of an authoritarianism that requires iteration. Repeating a name in conjunction with the object, or repeating the shapes of letters with it, is just that: repetition. How does this mere repetition come to overwrite the constellation and write the discrete object? Where does its authority come from? When I encounter a new object: whom do I ask what it is? When I have to perform a speech act for the first time: how do I know if I am doing it right? If all speech is “names and appellations and their connexion”, how do I know I connect the right dots in the right way? [15]

Indeed: how do I know the ‘names and appellations’ are correct? Anyone who learns a foreign language will know how difficult it is to even pronounce words correctly, just as anyone who is dyslexic knows the struggle contained in mere spelling. Both know how much iteration – practice that, as one might say, makes perfect – goes into learning pronunciation and spelling. But: ‘correct’ by whose standards? How do I know how the word ‘tree’ is pronounced or the letters t-r-e-e spelled? How do I know what part of the continuous unfolding of the world it belongs to – how it is not a shrub or a bush? How do I know how it relates to you and me and what function it serves?

At the heart of it all, there is nothing at all natural about the peculiar way in which air agitated by “divers motions of the tongue, palette, lips and other organs of speech” comes to form the sound ‘tree’, and how this in turn marks an object. [16] Nor is it at all natural how the shapes of pen strokes or keyboard strokes come to form the letters t-r-e-e, and how these in turn mark an object. All three – sound, ink marks, living constellation – are mere sensual impressions, unrelated elements within the general tapestry of the world. They might follow each other or they might not: “in sense, to one and the same thing perceived, sometimes one thing, sometimes another succeedeth,” and thus “in the imagining of anything, there is no certainty what shall imagine next.” [17] The mind wanders. Besides, I hear the word ‘the’ as often when I’m around so-called trees as I hear the word ‘tree’. Why should the sound ‘tree’ stand for the thing, and not the sound ‘the’? Why should the tree be a thing at all? Again, why do I know what is right and what is wrong?

I know these things because they are inscribed – disciplined and punished – into my flesh, my memory, my brain tissue. The train of my thoughts is disciplined and punished into associating the letter shapes t-r-e-e, the sound ‘tree’, and the discrete piece of reality they supposedly describe, and really inscribe. “For the impression made by such things as we desire or fear, is strong and permanent, or if it cease for a time, of quick return.” [18] If I call a tree a dog publicly, I will be ridiculed and eventually committed. That is, I will be corrected: my mind’s wandering is henceforth forbidden from venturing too far beyond the association of ‘tree’, t-r-e-e, and what is now an object. If I mispronounce or misspell a word, I will likewise be corrected: adjusted into the proper association by friends, family, bosses, or autocorrect. If I write a wrong word into a form, I will be fired, relegated, deported. If I say ‘what’s for dinner’ in the decisive moment of a wedding, I better not be one of the brides. “And because the end, by the greatness of our impression, comes often to mind, in case our thoughts begin to wander, they are quickly again reduced into the way.” [19]

Authoritarian iteration is thus everywhere contained in the operations of thought, speech, and letters. But it also has to be contained in these operations each time, or it vanishes. Discipline and punishment are themselves nothing but distinct impressions. Their seal of approval and disapproval on everyday speech acts and their contexts must, in turn, be iterated. Of course this does not mean that the connection between t-r-e-e, the sound ‘tree’, and the carved-out piece of reality is created out of thin air every time I encounter something new. Words do outlive me. But for me, and for each of us, they do literally come out thin air. Nothing about them is natural, except that they are constantly iterated alongside the punishment of deviating from them.

This is where the hysteria regarding schooling comes from. The imposition of reified objects, just as that of contracts and boundary markers, upon the world, requires constant repetition of speech act, context, discipline, and punishment. When parents, schools, hospitals, barracks, and prisons teach us to impose letters and signs, they teach us to also read rooms and landscapes, which is to say to impose them, and to obey the laws of legibility and intelligibility in all of our social interactions. They teach us, in other words, to iterate their domestication throughout the world. Teaching children how to write in the conventional sense teaches them how to approach the world as one filled with discrete entities iterating themselves and each other.

When I first encounter something I don’t know, I ask an authority – human or otherwise – for its name and use. Yet any pretense that such authority could be benign or even neutral within industrial civilization would be disingenuous, as I do so because I would otherwise be ridiculed, relegated, corrected, evaluated, abused, ostracized, deported. ‘Authority’, whether parental, scientific, or otherwise, is authoritarian imposition, because I resort to appeals to authority within civilization to use the right words at the right time, to pronounce them correctly and spell them correctly. “When a man upon the hearing of any speech” – or the reading of any letters – “hath those thoughts which the words of that speech, and their connexion, were ordained and constituted to signify, then he is said to understand it.” [20] The Father does not create words nor worlds, but He teaches them as though He did, and thus iterates them, each time for all time.

4. Deixis

The cops in my head are a literal grammar police, for everything works through the iteration of authoritarian imposition: correct pen strokes, autocorrect, correct sounds, correct gestures, correct manners. And in iterating my own domestication, I become a conduit of authoritarian imposition. By saying ‘I do’, I create a marriage. By saying, ‘cattle’, I create cattle. By saying ‘this is a tree’, I create a tree. This A is this A is this A just as this tree is this tree is this tree, and just as this human is this human is this human. Yet the reason these chains work is not their isolated iteration itself but the iteration of fear of authoritarian punishment which accompanies it. A tree is a tree is a tree because textbooks and schools tell me it is. This A is like that A because the form I fill in require them to be. This human is that human is that human because their passports require them to be.

Thus writing in the conventional sense contains potential vistas of resistance. Once we start thinking about trees and humans in terms of As and Bs and Cs, we see that iteration is the mechanism of authoritarian domestication, but not its origin. This is why civilization is terrified of anything regarding literacy. The letters of everyday writing in the conventional sense, archetypes of authoritarian iteration and yet themselves subject to it, provide a starting point out of civilization. Here is an angle to abandon the trite iterations of old-fashioned activism and instead “to make moves on a chessboard that no one else is playing on.” [21] This requires us – but also allows us – to learn from those who lived in a world where iteration was not iteration of discipline and punishment; those who inhabited the “vivid, healed, being-present state” we are aiming towards. [22]

James V. Morgan describes the usage of stone tools among those who did inhabit just such a state. Finding “anthropogenically modified chunks of rock” strewn across landscapes in what is now overwritten by ‘the United States’, Morgan will pick one up and

knock flakes off and make my own flakes and points...I’ll basically keep going on the work that someone stopped several thousand years ago, and I’ll just pick back up where they left off. And that’s phenomenal, you’re just holding this stone that-- who knows how many thousands of years ago someone was knocking flakes off of it...At first I thought, I don’t want to mess with these because they’re artefacts, but there’s so much of this stuff everywhere it doesn’t really matter. It’s kind of this anarchist principle. One of the things you realize when you’re out here is these people were recycling stone after stone after stone, undoubtedly...It’s used for a little while, tossed, maybe someone 300-400 years later picked it up again and decided to make a tool out of it or do a little re-touch and get it sharp and good again-- they’ll toss it again. You don’t even know for how many thousands of years these individual tools have been recycled and used by these different bands of hunters and different cultures. These landscapes, certain areas are covered with so many stone tools-- I’m not even joking. I’m talking about hundreds of thousands of stone tools littering the landscape...You can fully see the mentality when you find these stone tools laying on the ground that it’s no attachment to technology. Totally immediate return in this regard...There’s no need to carry this thing around because the task is done, and you know you’re going to find more stone as you continue to move across the land. So why carry this stuff around? It’s completely antithetical to this whole civilized, domesticated security paranoia and obsession with shopping and having all these things. [23]

It is antithetical, that is, to writing – to iterated authoritarianism. To the inhabitants of the landscapes Morgan roams, stone tools were not iterated chunks of discrete reality, but freely circulated in and out of the continuous unfolding of the world. They never became standardized, iterating gestures to processes accompanied by fear of punishment, nor ‘output’, iterating individual flakes to standardized templates.

Nor were these tools discarded in the same way that we discard the identical plastic implements littering our oceans and blood streams. The stones were discarded to be picked up again. Part of the land’s continuous unfolding while on the ground, they became part of their carriers’ continuous unfolding before resuming their position in the land. Thus, stones, humans, and land formed roaming constellations within a continuous world. That is, stones, humans, and land formed continuously renewed and renewing forms of deixis.

The essence of deixis is an individual, fleeting, non-iterated gesture, such as the index finger pointing at a part of the world, or a hand or the entire arm, a leg or bodily posture, or a tilt of the head. Non-human deixis, too, constitutes similar non-iteration, as in the individual way a swallow’s flight indicates the presence of land while at sea, when a thousand sand dunes indicate the direction of the wind in a thousand different ways, or when a dog’s particular mode of restlessness indicates the imminence of an earthquake. Such gestures are almost purely deictic: individual and non-iterative. Still somewhat deictic, yet already slightly iterative, are elementary incisions into the continuous unfolding of the world, such as rock piles and twigs marking trails, branches growing as the wind directs, or deictic word sounds such as “here”, “now”, and “this” or “that”. Further along the route towards iteration still are spatial and temporal deictic predicates, such as “here”, “now”, “over there”, “back then”.

Deixis is thus not entirely distinct from iteration but its opposite pole on a sliding scale. It inhabits iteration, just as iteration inhabits deixis. Pointing initially suffices, but soon crystallizes to “there”. “There” subsequently morphs into “up the trail”, which then solidifies by specifying how far up the trail (“by the third rock pile”). Eventually, the third rock pile up the trail comes to be measured in its distance from the starting point, and as the trail becomes a road, deixis serves to implement iteration. Addresses (“Rock Pile Road #141a”) and satellite coordinates (“53° 12’ 10.02’’ North, -1° 4’ 12.48’’ West”) still require some degree of deixis as they are implemented in daily life, but here deixis entirely serves at the behest of iteration.

Likewise, a swallow’s flight becomes “now”, “now” becomes “during this moon”, which becomes “the tenth moon of the year”, which becomes “Thursday, May 21st, 4 a.m. EST.” As deixis is increasingly overwritten by iteration, civilization closes in. Domesticated space and domesticated time are its primary axes. Yet even when this development is completed, bodily deixis must still be overwritten by iteration each time abstract space and time are implemented in lived spaces and rhythms “by threats of sanctions, by a continual putting-to-the-test of the emotions.” [24]

Iteration therefore never fully loses its deictic element. It must always remain rooted in the lived everyday world which it overwrites, and must always consist in the ceaseless quest to keep overwriting it. Even if “here” is abstracted to “53° 12’ 10.02’’ North, -1° 4’ 12.48’’ West” and “now” is abstracted to “746870400 Unix time”, operating on the basis of such values must still depend on rendering them into bodily placements, bodily gestures, bodily presence. It thus remains susceptible to being overwritten by them in turn: “The violence of equality-mongering reproduces the contradiction it eliminates.” [25]

This is where we can learn from Morgan’s account of stone tools to unlearn how to iterate and thus to learn how to adjust our letters until they, too, become non-iterative and deictic, and thus ephemeral and continuous: until deixis is reinscribed into them and into all writing.

Stone tools are deictic in two main ways. First, they are ephemeral, but not invasively so. To be sure, they are picked up and extricated from the land. Yet they are then minimally altered, transported a minimal distance – and returned after minimal use, to the unfolding of the land. Theirs is not an invasive ephemerality like that of single-use plastics. The latter are authoritarian iteration through and through. Abstracted not just from the unfolding of the land, but from any semblance of the continuous unfolding of the world, plastics emerge from lab-based iterations of workflows creating and arranging iterated molecules.

The emergence of plastic is thus a polar opposite to the emergence of stone tools midway between rocks and grains of sand, each of which seems as identical to the macrovision of human eyes as microplastics might. Yet the latter are not just overwritten by a casual gaze, but have never been anything other than original iteration. They are nothing but iteration and have never been anything but iteration. Grains of sand, like rocks and stone tools, look identical at first, but their unique signatures can be uncovered with a closer look or feel. Plastic does not have such qualities to uncover. Rather, it completes the trajectory of mining and metallurgy, increasingly violent cuts into the unfolding of the world, leaving increasingly large scars while removing itself increasingly from the land from which it came.

Stone tools are picked up from the surface or harvested in minimally obtrusive ways. Mining and smelting cut into the world from the off, leaving ever larger marks. And plastics, finally, are fully divorced from it. Littered, they leave discrete incisions in the unfolding of the world which are never absorbed back into deixis but remain eternal iteration. Plastic is ephemeral for us only, but not for the world, leaving millions of years of garbage patches in the oceans and millions of tons of microplastics in our lungs. Stone tools, by contrast, return to the continuous unfolding of the land when discarded. They emerge from it and return to it each time they are picked up.

Moreover, they are inherently continuous and remain so. A field of stones, at a beach perhaps or by a river, is a continuous unfolding of motions, where stones separate from rocks, tumble about forming temporary formations, and separate again. Each time they change shape, morphing each other to change sizes and shapes. Theirs is a doubly continuous unfolding: they remain continuous with the rocks from which they came and the sand into which they morph, and they remain in continuous motion with, through, and against each other.

Thus when hunter-gatherers picked up their stones to shape them, they performed the same gestures that the stones perform with, through, and against each other. Shaping stone tools retains the stones’ continuous path from rocks to sand. Discarding a shaped stone thus merely restores it to its place within continuous unfolding. To be sure, the stone is temporarily separated from its place within the land. A part of the land’s continuous unfolding has thus been rendered discrete, just as the index finger does when pointing, and just as boundary stones and satellite coordinates do. Yet the stone merely unfolds as it would have, and returns to its continuous place. The index finger points but leaves the land intact. The boundary marker invades the land. The satellite coordinate erases it.

Stone tool and index finger are deictic: leaving the land’s unfolding, they temporarily separate what they return. The boundary marker is halfway between deixis and iteration, transforming the land by invading it, yet leaving it still somewhat intact. There is an interplay here between iteration overwriting deixis and deixis overwriting iteration. The words on this page or screen, like the satellite coordinates and maps drawn from them, implement iteration only, invoking the world merely to make it a case of their own discrete unfolding.

Reinscribing deixis into writing engenders a reversal of the movement from stone tool and index finger through the boundary marker to the satellite coordinate and map. This is not to say that there can be a full roll-back. An element of iteration remains within speech and even in thought, and even more so in this writing; it remains, too, in the pointing index finger and the stone tool. Yet by the very token that there can be no pure point beyond the reach of iteration, there can also be no pure point beyond the reach of deixis.

Because entity is not immediate, because it is only through the concept, we should begin with the concept, not with the mere datum. The concept's own concept has become a problem. No less than its irrationalist counterpart, intuition, that concept as such has archaic features which cut across the rational ones – relics of static thinking and of a static cognitive ideal amidst a consciousness that has become dynamic. [26]

By learning to unfold our letters the way that stone tools unfold, we can inscribe deixis into the heart of iteration, activating its potential to critique and, to a significant extent, overcome itself.

For stone tools are not just continuous with the unfolding of the world: of rock, sand, and river. By being non-invasively ephemeral, they remain part of the continuous unfolding not just of the land but also of the muscles shaping them. These gestures never fully solidify to iteration, as each retains its personality and that of the stone tool, iterated as minimally as the alteration of the stone is. The hand and its associated muscles thus remain as feral as the stone does: “For all the complicated tasks to which this organic tool may rise, to one thing it is poorly suited: automatization. In its very way of performing movement, the hand is ill-fitted to work with mathematical precision and without pause.” [27]

Forced to iterate key strokes and swipe patterns, or to write letters in print, cursive, and calligraphy, the body and the hand are tamed and domesticated. Not just content with the hand, this domestication also affects the arm and posture, too. Any left-handed child ‘rectified’ can attest to this. As can the deaf, whose arms’ movements are standardized into sign language gestures, and those whose motor skills are affected, whose vocal tracts are tamed into the pattern recognition of speech synthesis software. Everywhere, domestication activates and subjugates the flesh and renders it useful. Everywhere, gestures dotting the Is and crossing the Ts are the same iterated gestures that write animal and human carcasses: discrete death in a world that has forgotten it depends on continuous unfolding.

Just as satellite coordinates require their implementation within the continuous world, however, so the body remains in play as iteration unfolds through it. The body’s gesture retain deixis in the heart of the empire of iteration attempting to render them obsolete. A machine’s gestures are nothing but iteration. But the body retains the pain and frustration of deixis overwritten and subjugated. Letters written by hand or speech recognition retain the suffering of subjugated muscles which letters predicted and autocorrected on the phone have already forgotten. The latter, like single-use plastics, litters the world with authoritarian iteration. But the former retains the memory of experience of deixis: of untamed muscles. The body therefore at once implements iteration and the pathway towards deixis: to its continuous unfolding within the continuous unfolding of the world.

5. Anti-Alphabet

Direct attacks in speech and thought project false utopias. Neither silent meditation, ostensibly opposed to the hectic pace of machinic life, nor the fullness of speech or chant in demonstration or parliament can return deixis against iteration. Both remain as ritualistic and formalistic as the “acronyms, boring claims, unreadable communiques” of ritualized old-timey anarchism, which is to say, both remain iterated. [28] Only the body and a change in how it acts can roll back the rule of authoritarian iteration.

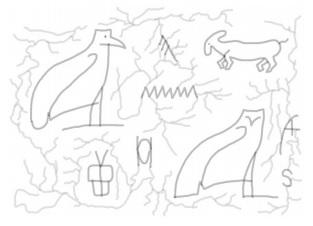

Key to achieving this is the reinscription of deixis into the letters at the heart of civilization. Rather than the single-use plastic iterations on this page, our letters must become deictic constellations: each letter unique and ephemeral like one of the stone tools described by James Morgan, each emerging from the continuous unfolding of the world and returning back to it. With this, their readability changes, too, from words to constellations. Ultimately, our letters will thus move from discrete gestures writing discrete entities into the world to continuous constellations implementing their own dissolution.

We will need to proceed with caution. Letters which dissolve themselves must remain readable, too, not just for the purposes of socially necessary communication – whatever this residual may look like – but also to the extent that they must themselves actively gesture towards their own dissolution. Asemic writing, abandoning readability altogether in favor of the pure graphic presence of traces on paper or screen, thus goes too far. Most of its instances negate the notion of readable text altogether. Yet in doing so, they end up affirming the discrete existence of iterated letters as the irreducible platform from which their endeavor derives its meaning. Likewise, the purely graphic art of typewritten or computer-generated asemic writing negates written communication only to iterate the page, the grid, or again the discrete presence of text. [29] Theirs are valuable explorations and critiques, and we will be wise not to forget about them as we chart our own path. Yet our own path we must take.

What is needed is rather the dissolving force contained in archaic logograms and syllabograms. Invoking these, and ancient writing systems in general, is not a conservative statement. The first and primary purpose of writing in the conventional sense, in archaic Mesopotamia and archaic Egypt, has been authoritarian iteration: the recording of boundary markers and collection of tax records in service of emerging states and centralized entities. [30] Nor, for the same reason that we cannot use asemic writing by itself to develop letters which dissolve themselves, can we here simply reverse Hegel’s dictum that writing in the contemporary Latin alphabet is superior to its predecessors. Archaic alphabets by themselves are not somehow more primitive (in the positive sense!) alternatives. As pure negation, this stance would simply iterate discrete texts in the Latin alphabet, affirming them as a negative foil.

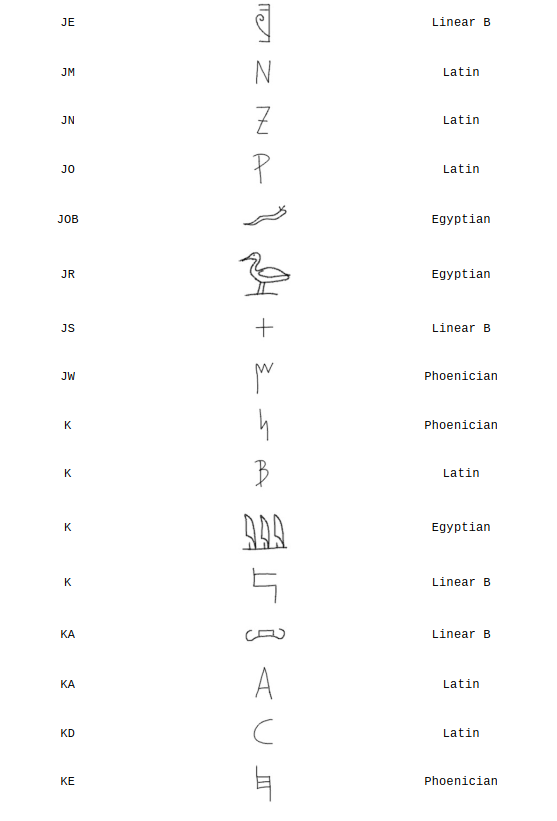

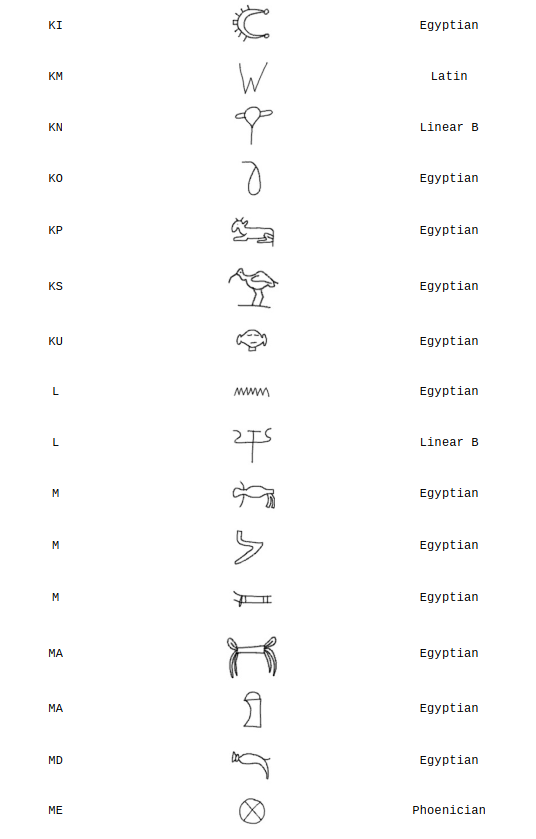

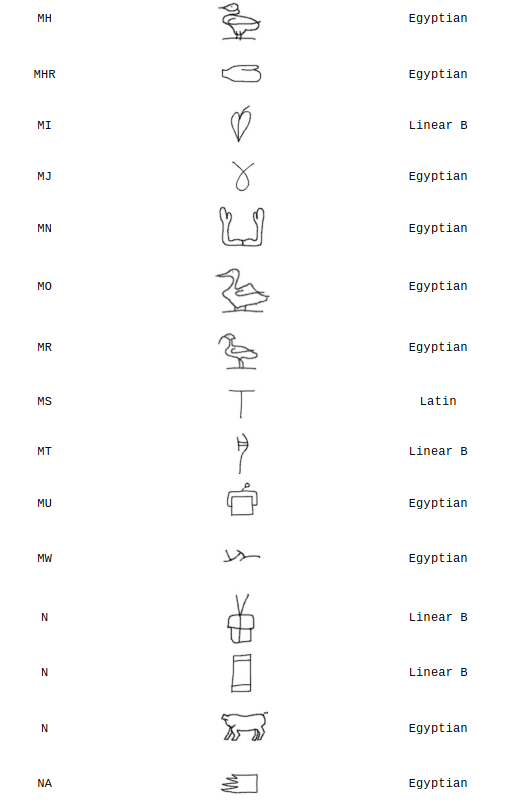

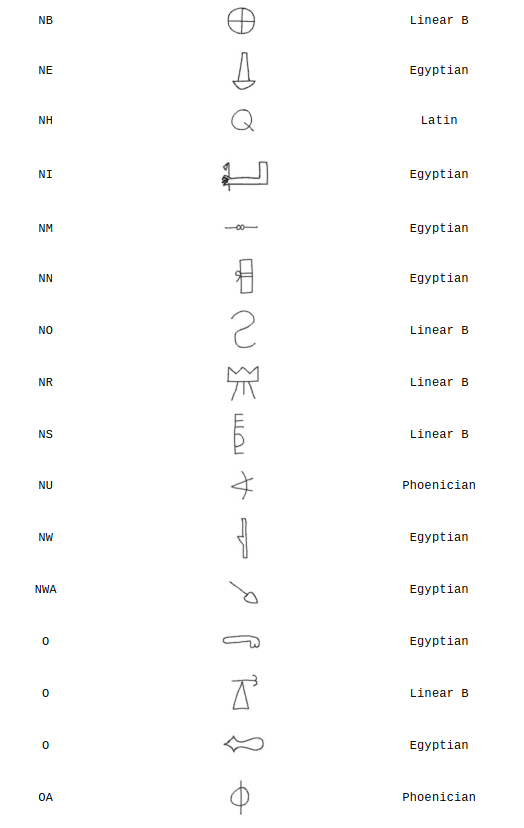

Invoking ancient Phoenician, Mycenaean Linear B, and Egyptian Hieroglyphs, therefore, does not iterate these as such, but uses them – each in a different vector – to inscribe deixis into the Latin alphabet. We retain the latter, but combine it with the other three in specific ways to pave the way for deixis within writing.

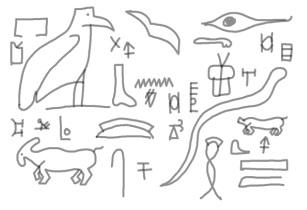

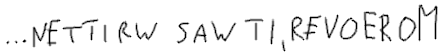

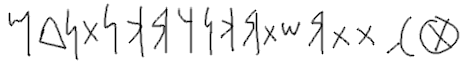

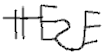

With ancient Phoenician, a good amount of the heavy lifting can already be achieved. The ancient Phoenician alphabet, as it was used in the ninth century BC, was a consonantic script, that is, it did not have letters for vowels. It was also written continuously, that is, it did not separate either words or sentences. Moreover, it was written from the right to the left, much as present-day Hebrew and Arabic texts are. Almost trivially by comparison with these three characteristics, it also used letters that looked different to the ones we use. Thus the previous sentence (“Moreover...”), in ancient Phoenician, looks as follows:

In the present context the differing sets of letters, as well as writing from the right to the left, are perhaps trivial enough. They might be useful as a reminder that there are already scripts other than the Latin alphabet used by modern English: Cyrillic, Hebrew, Arabis, Japanese, Korean, Mandarin, not to mention native scripts on the verge of extinction.

Far more consequential for our purposes, however, are the absences of vowels on the one hand, word and sentence markers on the other. For it is by means of these two that discrete units of meaning emerge, that is, that discrete entities are carved into the continuous unfolding of the world in supposedly neutral ‘reference’. Consider again the above sentence

We might turn this into a right-to-left notation, which is still conventional enough:

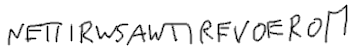

Even removing the boundary-markers as such – commas, empty spaces, dots; in other texts perhaps slashes, colons, etc – does not present insurmountable difficulties in a reader hell-bent on maintaining the words as they are:

This script is reminiscent of the oldest extant examples of archaic Latin writing, dating to the sixth century BC. [31] Transposing this further, into the archaic Greek script which first used written vowels in Europe, takes us two centuries further back and makes it considerably more difficult for our hell-bent reader:

Yet only when we go yet another century back, to ancient Phoenician letters without vowels, do we get a substantial intervention into our sentence, rendering it more readable than asemic script, but only just:

What is removed here are the discrete units by which the world is carved up, that is, the conventional function of writing. The letters no longer form discernible syllables, discrete words or morphemes, and ultimately sentences. Thus they begin their pathway towards deixis.

Liberating the letter from its servitude to discrete syllables and words, the invocation of ancient Phoenician destabilizes the ability of sentences to carve out discrete parts of reality and to reify them. Above all, it destabilizes the seemingly innocuous gesture of ‘reference’, whereby the authoritarian iteration of a name, a denomination, a genus or species, overwrites the living constellation to which it supposedly – and supposedly neutrally – refers. The letters t-r-e-e can work in tandem with the sound ‘tree’ because they are themselves discrete. If the former come to be embedded into a continuous series of letters without vowels, their connection with their sound is just as much severed as their connection with their supposed referent. Were the words “The letters t-r-e-e can work in tandem” rewritten in ancient Phoenician, the result would be:

Without iterated relation to sound or referent, the letters are thus destabilized to the point where they revert to being independent phenomena in their own right: “what we indicate is by speech, but the things that exist and that are are not speech...So it is not the things that are that we indicate to other people, but rather speech, which is different from the things that exist.” [32] Yet as such, this would only revert our letters towards an asemic or perhaps deconstructive form of written text. To break the spells of industrial civilization, further destabilization is necessary.

Here, the syllabograms of Mycenaean Linear B come into play. Linear B takes us some six or seven hundred years further back than ancient Phoenician. It emerged on Crete in the form of the still incompletely deciphered Linear A in the 19th century BC. But the form we will focus on here was used as Linear B between the 15th and late 13th centuries BC both in Crete and mainland Greece. As with the Phoenician, however, Linear B is not here invoked as such or for antiquarian reasons. After all, even more than Phoenician, which had at least some non-state uses, it appears that Linear B was never used for anything other than making lists of goods moving into or out of the Mycenaean palaces. [33]

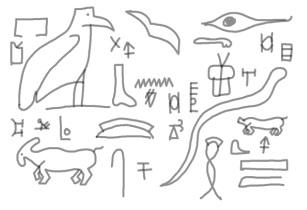

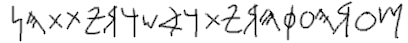

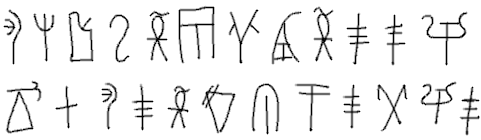

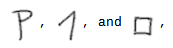

It is not on its own, therefore, but in tandem with the Phoenician and Latin scripts that Linear B is used here. This means discarding Linear B’s ideograms, which directly indicate goods traded across palaces, thus directly and unambiguously performing the carving gesture of supposed referentiality. What is left are some eighty syllabograms which have thus far been deciphered, written from left to right. Thus the above sentence (“Moreover, is was written...”) reads as follows when transposed into Linear B: [34]

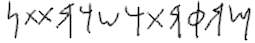

Re-transposed into modern English spelling, it becomes plain what we mean by syllabograms, for each Linear B letter stands not for one letter (though there are some exceptions – namely, the vowels A, E, I, O, and U) but for a syllable. Some of these are adjusted, too, to match the ancient alphabet. Thus the above reads:

mo-re-o-we-ri-wa-sa-wi-ri-te-te-ne

wo-ro-mo-te-ri-ki-ti-to-te-je-ne-te

Here again, the words and syllables dissolve as they did with Phoenician, but now under a different line of attack. Unlike the Phoenician, which removes the vowels and generates a continuum of – in themselves discrete – consonants, Linear B plays with the written boundaries of English words, now upholding, now adjusting, now removing them. Thus it further weakens the ties between letters, sound, and supposed entities, which Phoenician had attacked.

Moreover, Linear B introduces a kind of deixis into the writing itself which Phoenician could only gesture towards because its letters, despite their somewhat unique looks, are still too close to those of the Latin script which we use. With the Linear B syllabograms, any trace of a conventionally readable script vanishes. Yet the syllabograms also retain a readability in principle, like Phoenician and unlike their asemic counterparts. Intervening into the iterated Latin texts of today, Linear B syllabograms thus reinforce that all letters – including those of the Phoenician or Latin alphabets – are just shapes and marks on a surface. Seen as phenomena of their own, Linear B syllabograms thus recede into the continuous unfolding of the world, as they themselves unfold as pure shapes in addition to remaining readable.

Presence as pure shapes is thus a possibility inscribed into the heart of the Latin script. Linear B syllabograms thus continue to open up the vista first engendered from the intervention of Phoenician letters. Theirs is a gesture towards a type of letter which can be like the stone tools Morgan describes: ephemerally readable, they emerge from the continuous unfolding of the world as so many shapes and marks, and are able to recede back into it in the same way.

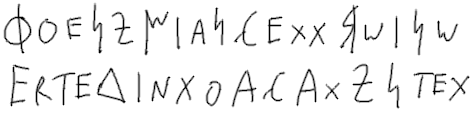

Phoenician letters, inserted into a Latin text, destabilize its vowels, its syllables and its words, until it becomes incapable of iterating reference:

Further inserting Linear B syllabograms, in turn, threatens the very quality of letters as letters, leaving them to be read merely ephemerally after a continuous emergence and inviting their being-discarded back into the continuous unfolding of the world:

Thus far, however, the discarding of letters is merely abstract, as abstract as Linear B syllabograms are. What is needed to make such receding a movement inherent to the letters themselves, thus allowing the critique of the concept from within itself, is an injection of concrete, living constellations into the script itself. This step is taken by invoking Egyptian Hieroglyphs.

Like Linear B, and to a lesser extent the Phoenician and Latin scripts, the Hieroglyphic script of ancient Egypt was invented to serve “the need for ever more complex information processing” as “the increasing centralization of political and economic authority required sophisticated forms of administration – notably record-keeping and the invention of writing.” [35] In this, Hieroglyphs are no different to the cuneiform of Mesopotamia, or indeed any other form of writing including our own. Throughout early Egyptian history, Hieroglyphs served to iterate the authoritarianism of the Egyptian king all over Egypt and, as evidence of early human sacrifices attests, into the afterlife as well. [36] Yet unlike Linear B and, to a significant extent, unlike cuneiform, Egyptian Hieroglyphs retain something of their origin, which can serve us as a powerful tool against iteration.

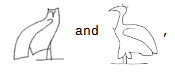

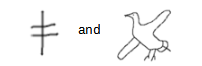

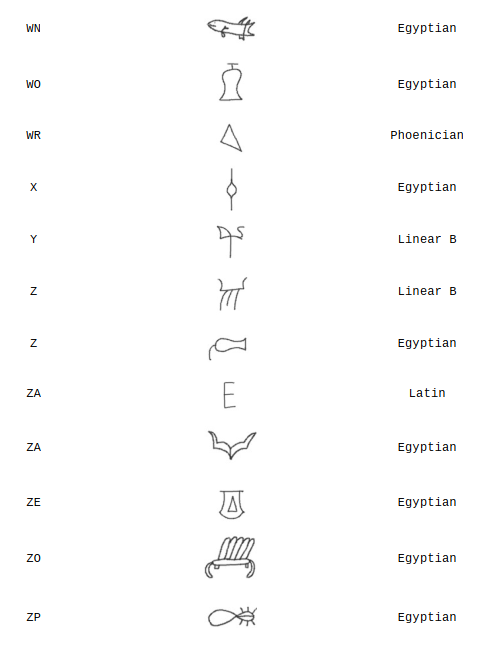

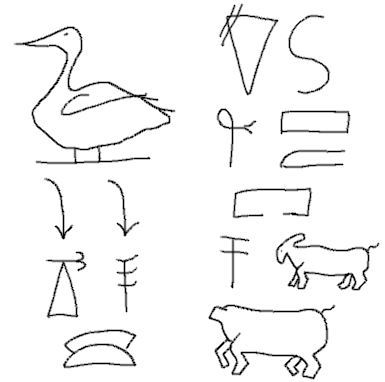

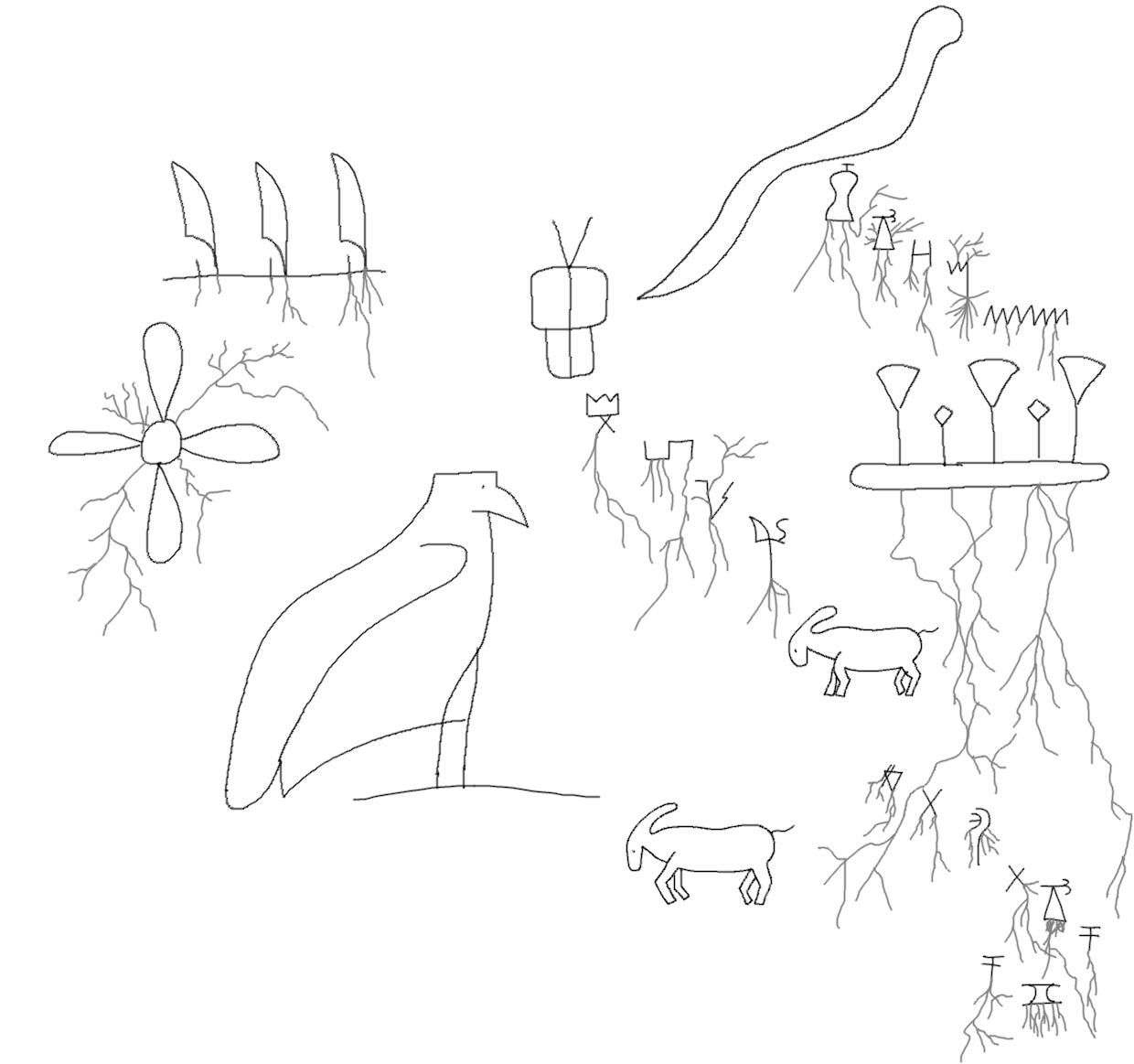

To be sure, when the Egyptian scribe drew owls and birds

these were intended as iterations of an “m” and “nh”, respectively. Facilitating this iteration is why the Egyptians actually invented two scripts rather than one, with the everyday script (the Hieratic script) being much closer in its look to the present-day Arabic script than to Hieroglyphs.

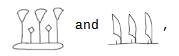

Yet invoking high Hieroglyphs here injects that script’s origins. Just as satellite coordinates require bodies to implement their rule over the land, thus inviting these bodies to resist, and just as iterated authoritarianism in general requires a body to implement its supposedly neutral gestures of reference, thus inviting the entities carved out to resist, so the animals and plants of the Hieroglyphic script, designed to implement the king’s rule over nature, are nonetheless invocations of just those subjugated animals and plants, conjuring their – and thus allowing our – resistance. Pre-dynastic king names Scorpion and Crocodile, for example, retain the names of their animals on their serekhs (name tags), inviting polysemy. [37] The animals are never far from Egyptian Hieroglyphs, nor are the plants. Again when the ancient Egyptian drew

these would be iterations of “sa” and “sm”, respectively. Yet the plants invoked here, however abstract, haunt the script on the page.

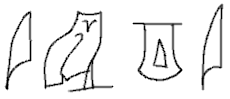

This means that Hieroglyphs introduce, first, a more direct axis of resistance into the script itself. From their vantage point, Linear B syllabograms and even Phoenician and Latin letters, their iterative characteristics destabilized in their interplay up to this point, come alive. Thus a set of Linear B syllabograms encountered in a text, such as

may well recombine to form living things, such as a twig and a feather, thus gesturing beyond the page towards living constellations

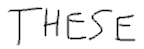

Likewise, Latin letters such as

may well recombine in various ways, dissolving themselves to reemerge as quasi-Hieroglyphs

or fusing to form shapes hitherto unwritten

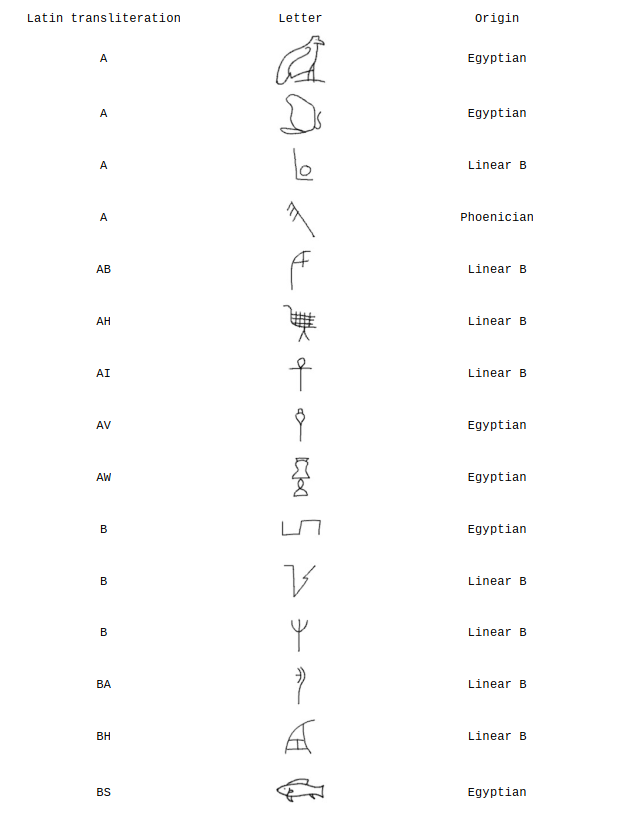

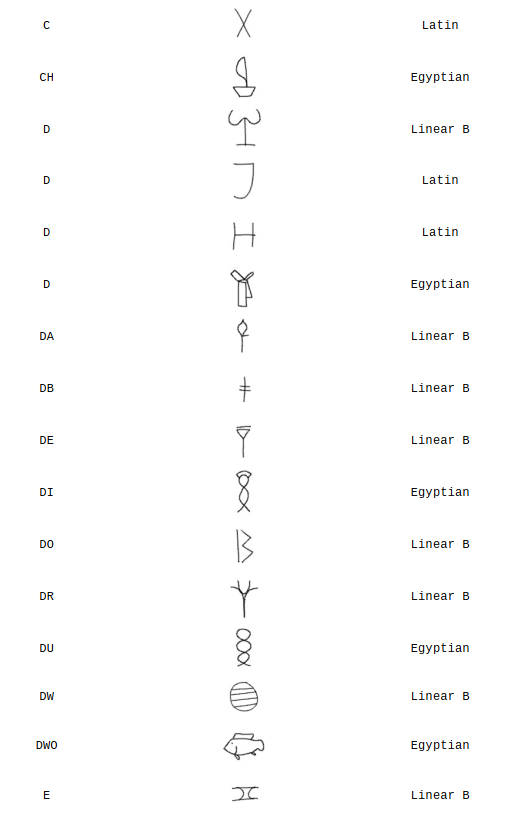

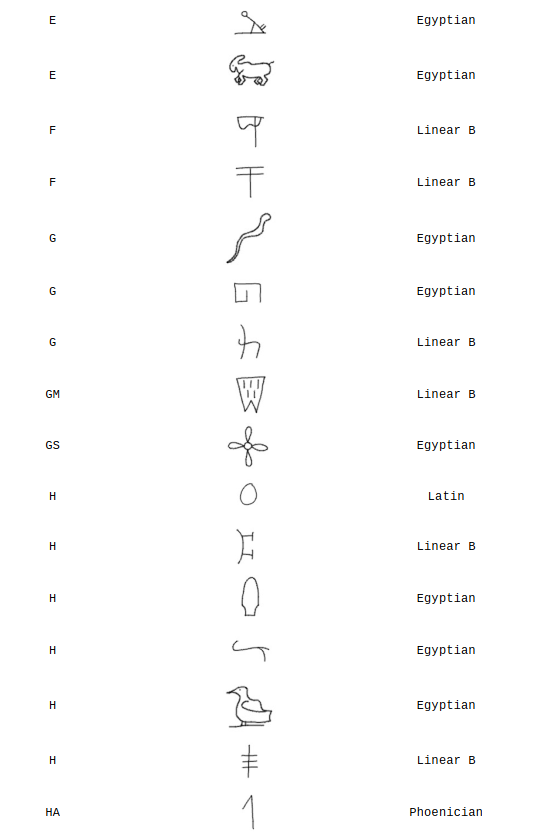

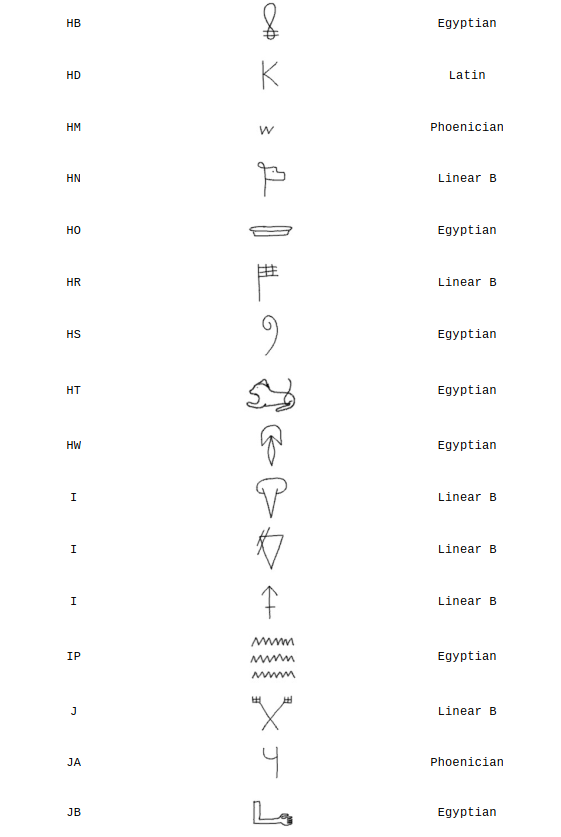

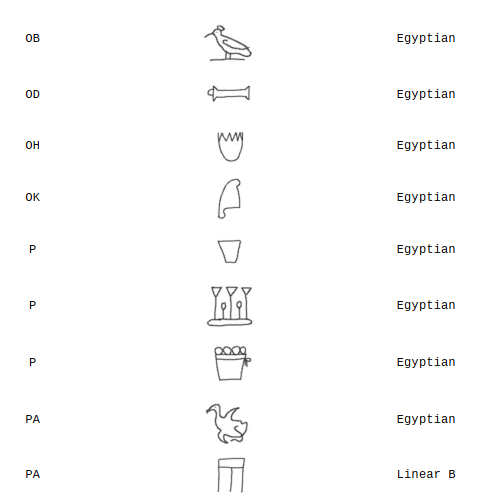

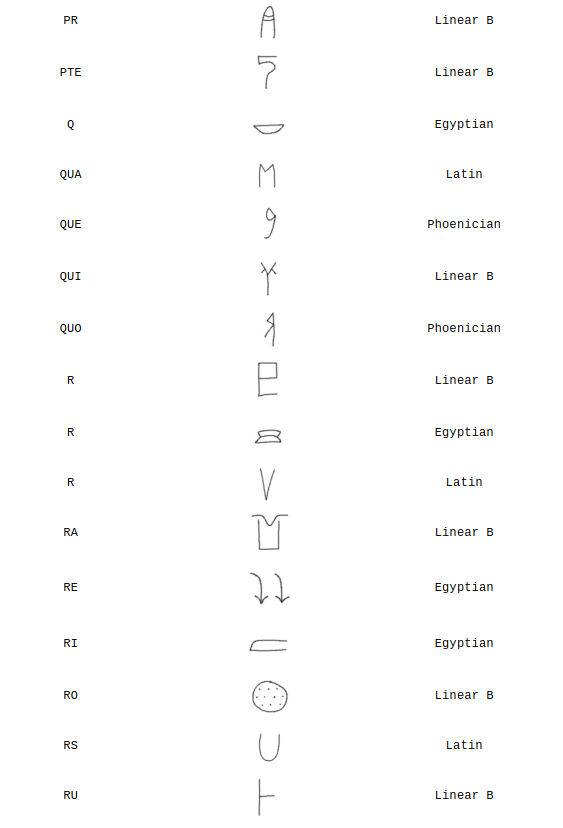

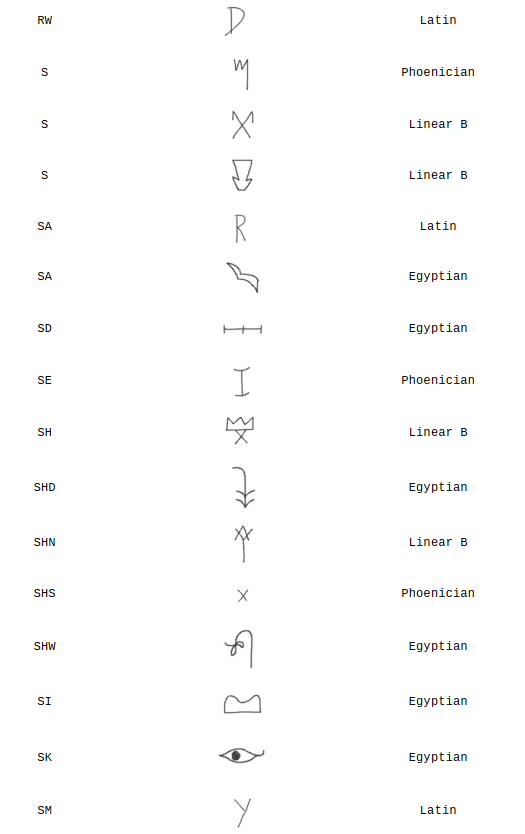

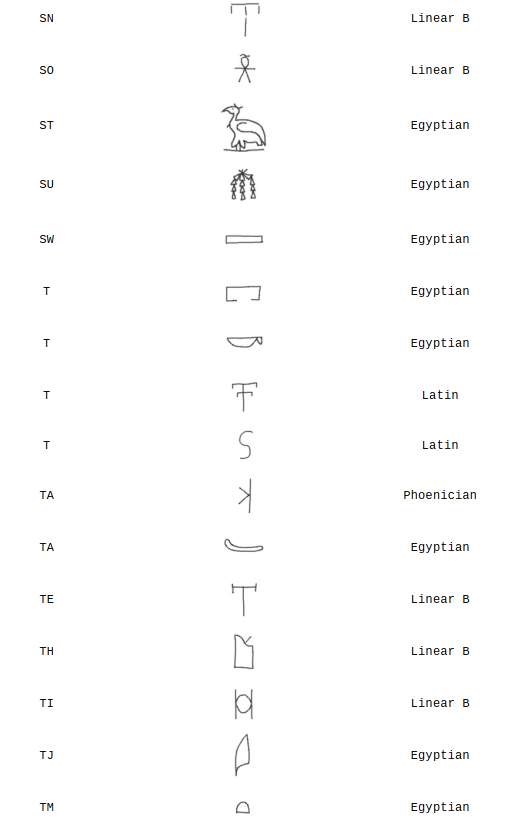

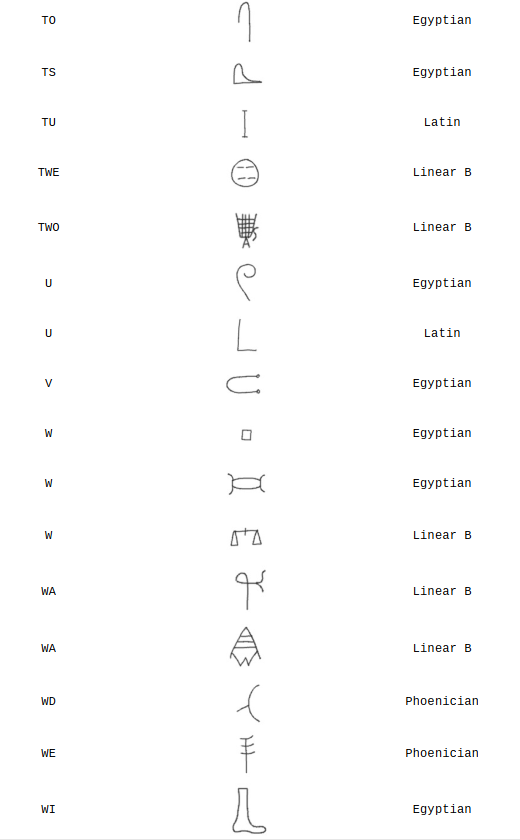

We must go beyond this, however. Integrating the four scripts results in an explosive combination. Beyond the destabilization of word units in Phoenician and syllables in Linear B, beyond the destabilization of letter-shapes and reference in Linear B and Hieroglyphs, beyond the immediately conjured animal and plant resistance in Hieroglyphs, combining all four also introduces additional levels of polysemy. For instance, we now have three values for “a” – Latin, Linear B, and Hieroglyphic – alongside two each for “pa”, “wa”, and “sa” – Linear B and Hieroglyphic. Likewise, Linear B alone introduces separate values for “twe” and “two” in addition to the individual spelling of their letters.

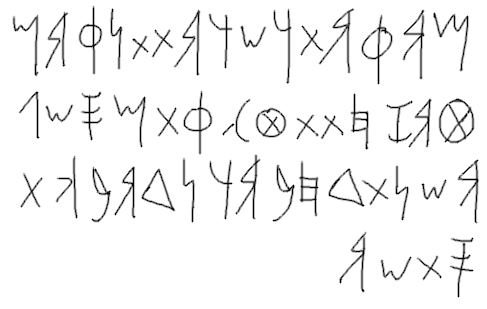

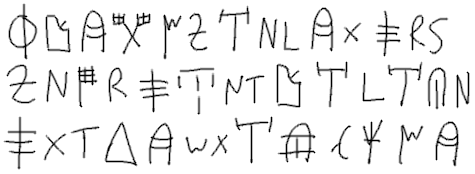

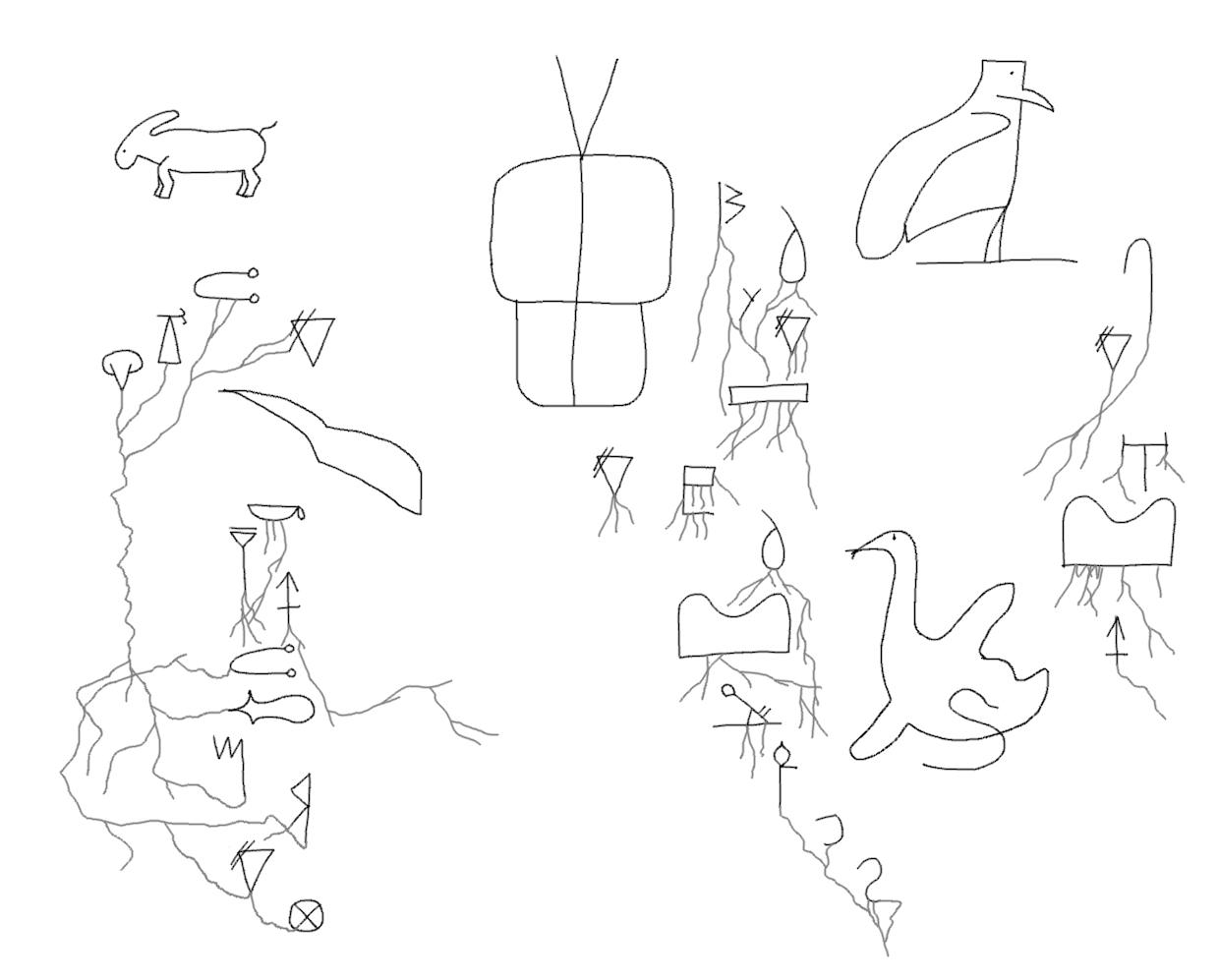

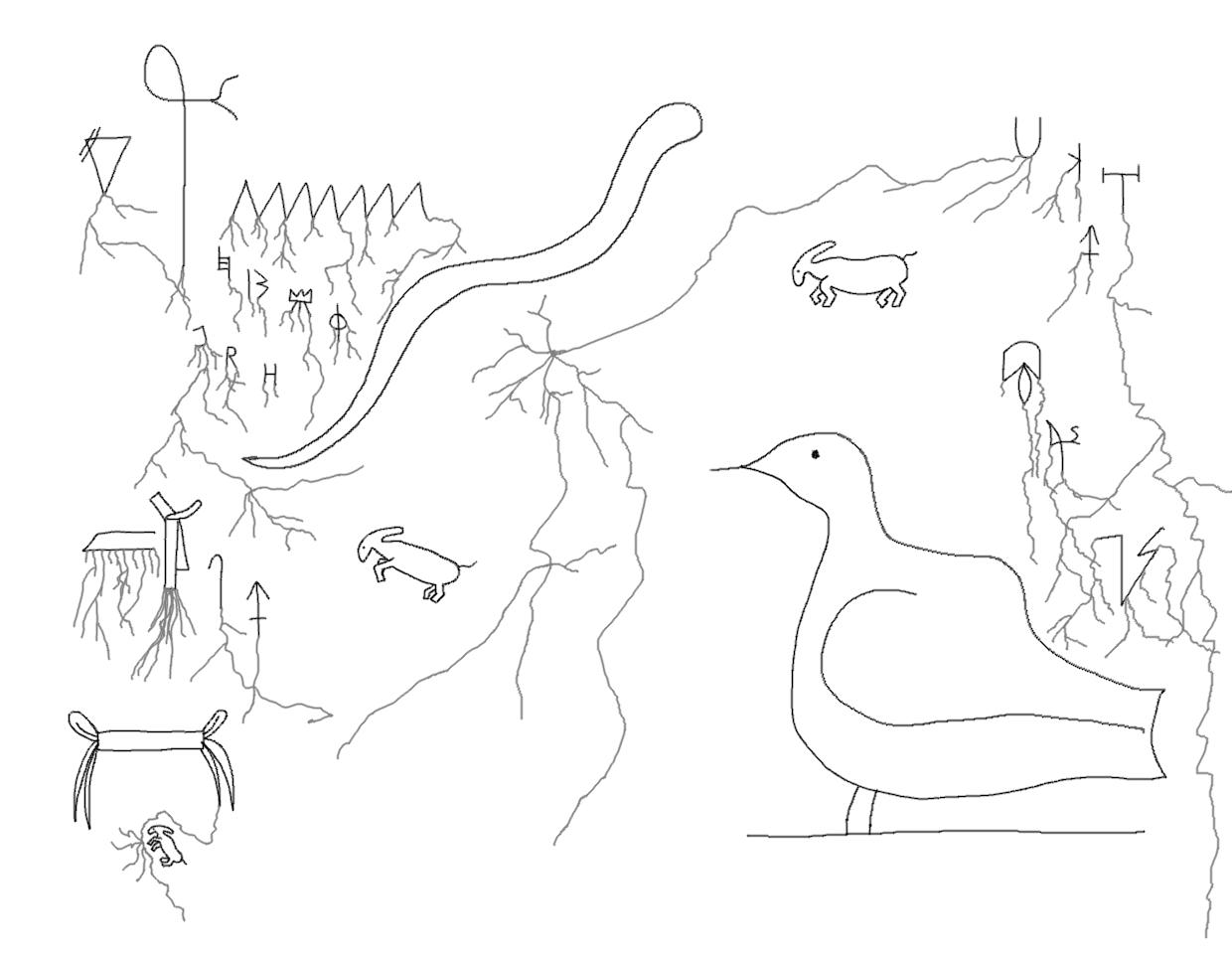

Up to this point, however, we too have followed the rules of iteration – albeit iteration of long-defunct authoritarianisms. Amid these long-defunct authoritarian iterations, there are potentials for a deictic writing: for an Anti-Alphabet whose letters dissolve themselves and return to the continuous unfolding of the world like stone tools do. Yet to break the final spell we face here, that of our “foolish, tyrannical, and dead grandfathers,” [38] and to stop iterating their trade and tax records, we must now activate these potentials. We do this in three ways. First, we liberate the letter-values; second, we liberate the animals in our script; third, we transform the remainder into plants.

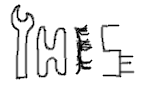

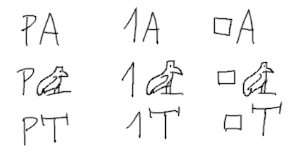

The liberation of letter-values has already begun in the redundant characteristics of the combined four alphabets. If a “p” can be written as

the connection between the letters or patterns and their values are already weakened. The same applies to the syllable “pa”, which can now be written in eleven different ways – twice as syllables:

and nine times as combinations of various “p” and “a”:

and so forth. So why not complete the principle of capriciousness – if not arbitrariness – which is so obviously inherent in the letters and their values? Why not take a page from the illegalist playbook and treat the alphabets, once combines, as so many cyphers? Why not blow up the combined alphabets and reassign values as the pieces fall back to the ground? Doing so results in a total of 218 letters, distributed, for the purposes of this book, as follows:

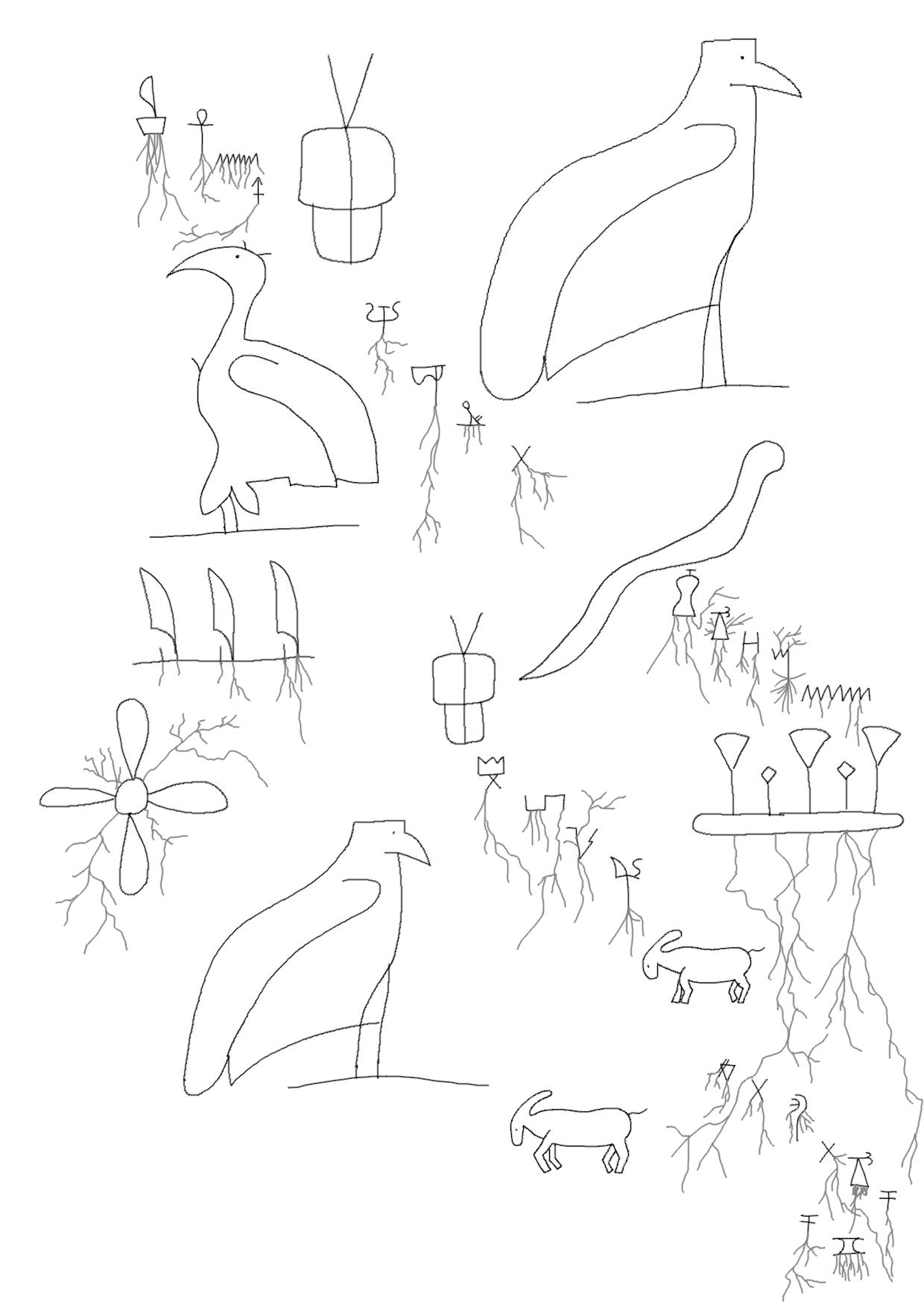

The second step which follows this distribution is the liberation of the animals in our script. These are obvious in the case of the Hieroglyphics appropriated here; birds (“st”, “ph”), mammals (“e”), serpents (“g”), fish (“wn”). Linear B contributes, for example, an insect (“n”). To liberate them, we can appropriate an Egyptian technique.

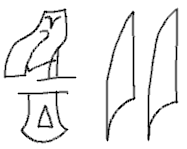

The placement of each individual letter in an Egyptian inscription differs from the text visible here in three principal ways. First, letters are written in columns from top to bottom, not in rows from left to right, as in the Latin script, or right to left, as in ancient Phoenician. Secondly, these columns are arranged around the contours of artworks, arranged following the lines of the bodies in these artworks. And thirdly, individual Hieroglyphs are arranged not in a linear fashion, but according to aesthetic fit. [39] Thus an ancient Egyptian might write the word “image” no in a linear way, as the Latin script would

but would arrange the letters more artfully in a square

The arrangement of letters thus still follows a general top-left/bottom-right direction, but graphic concerns rather than the convenience of pure iteration forms the organizational principle.

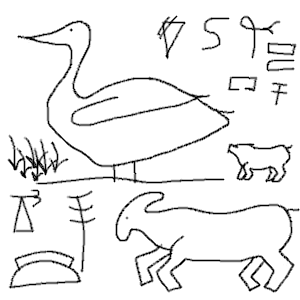

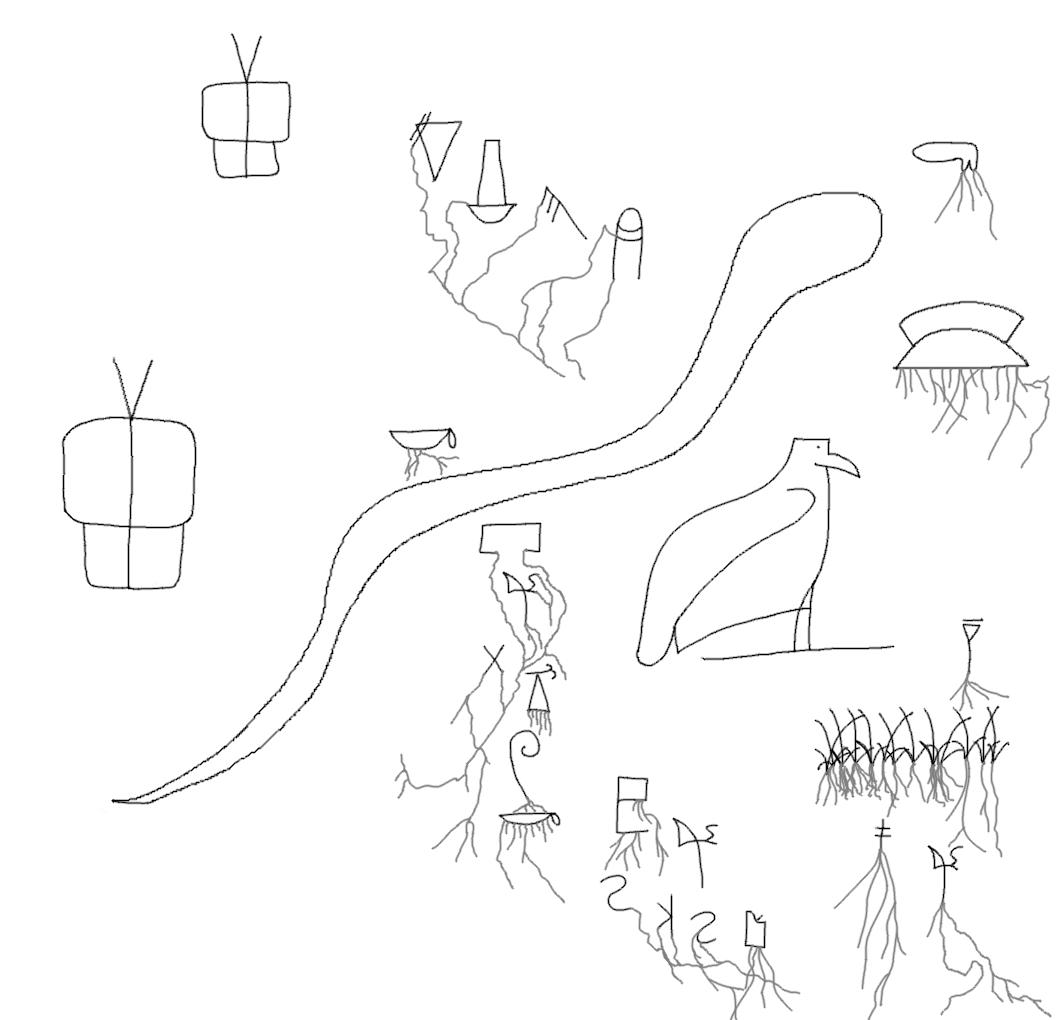

As we appropriate this principle, we can write our long-standing example sentence (“Moreover, it was written...”) in our new script. First, we arrange it the way an ancient Egyptian might have:

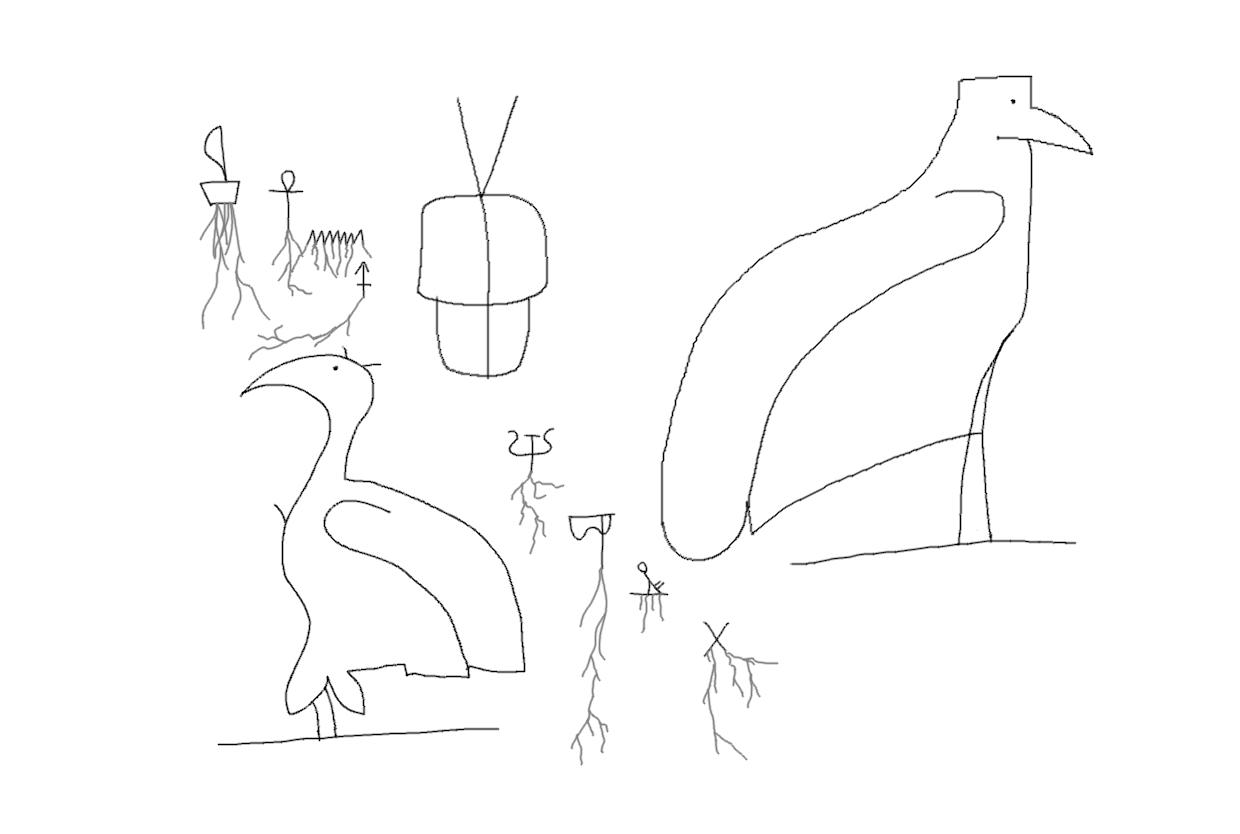

Were this an iteration of ancient Egyptian writing, it might develop further to arrange itself around the body of a high-ranking official, perhaps the king himself, or a scene of battle or hunting. Instead, we now place the animals front and center to liberate them, changing their size, their placement, their relation to one another, and their bodies’ shapes, gestures, and movements – until they become a living constellation:

Thus, the script arranges any letters other than those of the animals around them, giving them immediately visible pride of place. By thus implementing the critique of their letter-values, the animals in our script become ephemeral, emerging as discrete entities only to immediately dissolve back into their living constellation, engaging one another and nudging, asking, cajoling the reader to read in such a way that the living world is immediately manifest through them. No two animals in this script are alike, each injecting deixis into the page and gesturing towards the living beings which it conjures.

Moreover: the way in which they are unlike one another creates constellations on the page or the screen. Each animal’s deixis thus not only points to this animal or this species off the page, but points to the ever-unfolding continuum of animals and species off the page. Thus the page, too, recedes back into the continuous unfolding of the world, and does so by itself, simply because the script and its animals do.

The animal-letters of the script thus become their own dissolution, receding back into the unfolding of the world. Just as they, therefore, are like the stone tools Morgan describes, ephemerally emerging from the world’s continuous unfolding to roam freely on and off page and screen, so my act of drawing them allows my hand and arm to roam free, to arrange and give life to constellations, to experiment and liberate myself from iteration. Likewise if I can’t use hand and arm but use speech recognition or eye movement recognition tools, the animals resulting from deictic letters, and their constellations, remain alive as I give them life, and they in turn gesture beyond themselves to their brethren off the page or screen – each of which is as individual as they are. And all of this emerges without ever losing the option of conventionally reading letter-values and thus without ever impairing socially necessary communication!

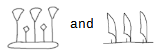

Yet it is still not sufficient to liberate the animals only. If the unfolding of the world is to be implemented via the page, rather than vice versa, a final step must liberate the smaller, but no less important, lives of the plants too. Their continuous unfolding is, above all, an unfolding of roots, branches, undergrowth. Once conceived in these terms, the remaining letters too can be left to grow wild and feral across page and screen and beyond, not just the ones that are ostensibly and obviously plants. Thus, not only the letters

can morph to become undergrowth, but all of them, including the Phoenician and Latin letters. Each of them, after all, is so open to growing roots and branches:

Every letter that is not an animal thus becomes a plant. Growing roots, branches, leaves, each gains a personality, gesturing towards a little yet important life off the page or screen. Growing into one another, surrounding the animals, each letter contributes to a deictic constellation, a living ephemerality emerging from the continuous unfolding of the world and receding back into it. Iteration evaporates as readability is retained just sufficiently for a conventional reading always superseded and threatened by the animal-and-plant characteristics of the letters.

Picked up like stone tools, the animal-letters remain roaming freely amid the growth of the plant-letters surrounding them. Each animal-letter teaches us the joy of the moment experienced by the animals around the page or screen. Each plant-letter in turn teaches us “that there is an enhancement of life when one is still, whether through long cold periods when our mobility is limited or simply during a succession of moments while watching vegetation return in abundance during warmer periods.” [40]

Combined by the gestures of our hands, throats, or eyes, the letters form constellations, each page uniquely, continuously unfolding deixis, continuously gesturing to a healed world. And I, too, am now no longer iterating but giving life to animal-letters and plant-letters in constellations uniquely flowing from my arm and hand onto page and screen, affirming my own uniqueness alongside that of each animal and plant, and alongside yours.

[1] John Zerzan, Future Primitive Revisited (Port Townsend: Feral House, 2012), 23.

[2] Donald MacKay, “The Epistemological Problem for Automata,” in John McCarthy and Claude Shannon (eds), Automata Studies (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1956), 236-237.

[3] Jacques Ellul, The Technological Society (New York: Vintage Books, 1964), 128.

[4] Siegfried Giedion, Mechanization Takes Command (New York: W.W. Norton, 1969), 246.

[5] E.H. Warmington (ed), Remains of Old Latin, vol. IV: Archaic Inscriptions (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2016), 263.

[6] Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, Dialectic of Enlightenment (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2002), 204.

[7] Primary Language Curriculum Support Material for Teachers (Dublin: National Council for Curriculum and Assessment, 2021), 4.

[8] Ibid, 5.

[9] Ibid, 7.

[10] Ibid, 11.

[11] Theodore Roszak, The Cult of Information (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), 196 and 199, respectively.

[12] John Zerzan, Running on Emptiness (Port Townsend: Feral House, 2002), 2.

[13] William Godwin, An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 458.

[14] Feral Faun, “The Cops in our heads: Some Thoughts on Anarchy and Morality,” via Anarchist Library.

[15] Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (Ware: Wordsworth Editions, 2014), 26.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid, 21.

[18] Ibid, 22.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid, 33.

[21] Aragorn!, “Nihilism & Strategy,” in Uncivilized: The Best of Green Anarchy (Green Anarchy Press, 2012), 275.

[22] Zerzan, Future Primitive Revisited, 120.

[23] “Hunting for stone with James V. Morgan,” in Oak Journal, no. 3 (2021), 74.

[24] Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space (Malden: Blackwell, 1991), 235.

[25] Theodor Adorno, E.B. Ashton (tr), Negative Dialectics (New York: Continuum, 2007), 143.

[26] Adorno, Negative Dialectics, 153.

[27] Giedion, Mechanization, 46.

[28] Massimo Passamani, “Letter on Specialization”, in Wolfi Landstreicher (tr.), Canenero (Berkeley: Ardent Press, 2014), 121.

[29] See, for example, Imogen Reid’s Text(ile) (Malmo: Timglaset, 2021), and Rachel Smith’s read(writ)ing words (Oswestry: Penteract, 2020).

[30] Kathryn A. Bard, “The Emergence of the Egyptian State,” in Ian Shaw (ed.), The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 64.

[31] Warmington, Remains of Old Latin, 196.

[32] Gorgias D26b, at 84 (Andre Laks and Glenn Most (eds), Early Greek Philosophy, Vol. VIII (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016), 241). That letters do not have an independent existence, but only serve as parts of syllables and words, is one of the oldest truths among those who think about questions of language. Touched on by Gorgias and some other Presocratic thinkers, it is first made explicit in Plato’s Kratylos and Aristotle’s Rhetoric.

[33] Michael Ventris and John Chadwick, Documents in Mycenaean Greek (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1973), 42.

[34] After Ibid, 23.

[35] Toby Wilkinson, Early Dynastic Egypt (London: Routledge, 1999), 46.

[36] Ibid, 227.

[37] Ibid, 57.

[38] Lysander Spooner, No Treason no. 6: The Constitution of No Authority (1867), ch. 1.

[39] Hieratic script, by contrast, is written in lines from left to right; another reason why we rely here on high Hieroglyphs, despite their questionable tax collection lineage.

[40] Army of the 12 Monkeys, “Diary of a Female Stone-Age Hunter-Gatherer,” in Uncivilized, 376.