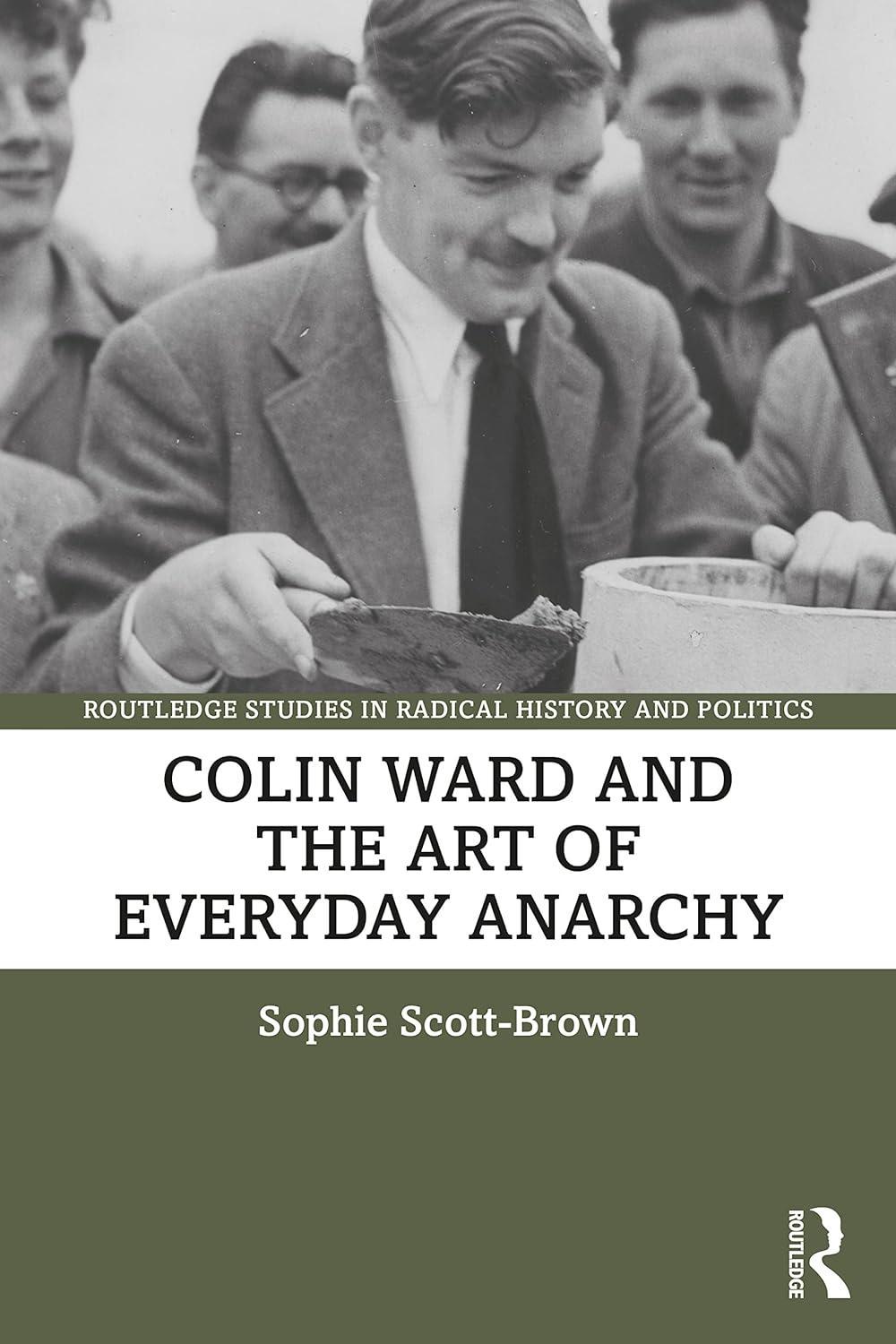

Sophie Scott-Brown

Colin Ward and the Art of Everyday Anarchy

Wanstead, Childhood, and Youth

3. The Freedom Press Anarchists 1936–1945

Italian Anarchism and Spain and the World

The Parish Pump and the Village Fete

Anarchy: A Journal of Anarchist Ideas

8. A Journal of Anarchist Ideas

Garnett, Godwin, and Wandsworth Tech

Afterword: the Everyday Anarchist

International Institute of Social History

Colin Ward and the Art of Everyday Anarchy is the first full account of Ward’s life and work. Drawing on unseen archival sources, as well as oral interviews, it excavates the worlds and words of his anarchist thought, illuminating his methods and charting the legacies of his enduring influence.

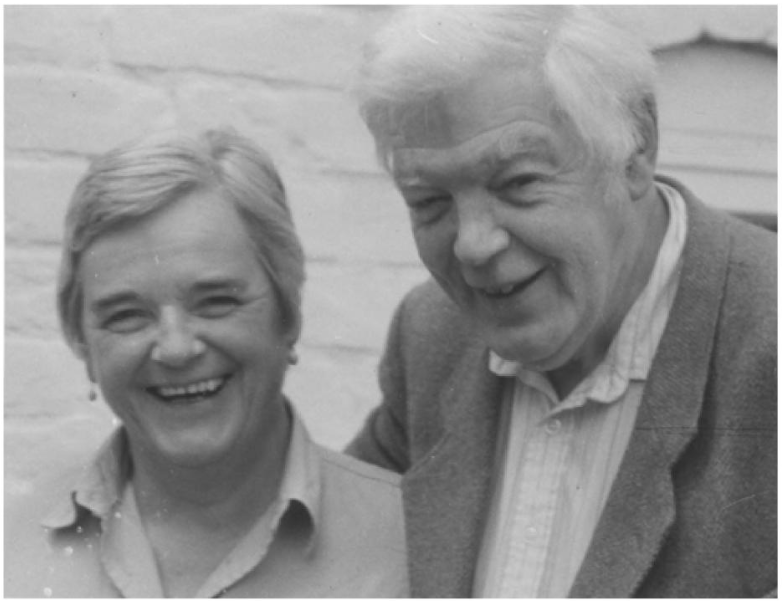

Colin Ward (1924—2010) was the most prominent British writer on anarchism in the 20th century. As a radical journalist, later author, he applied his distinctive anarchist principles to all aspects of community life including the built environment, education, and public policy. His thought was subtle, universal in aspiration, international in implication, but, at the same time, deeply rooted in the local and the everyday. Underlying the breadth of his interests was one simple principle: freedom was always a social activity.

This book will be of interest to students, scholars, and general readers with an interest in anarchism, social movements, and the history of radical ideas in contemporary Britain.

Sophie Scott-Brown is a Lecturer in the Humanities at the University of East Anglia, UK.

This book is for my parents, Lesley (teacher) and Steven (planner), and partner Matt (anarchist). With love.

Acknowledgements

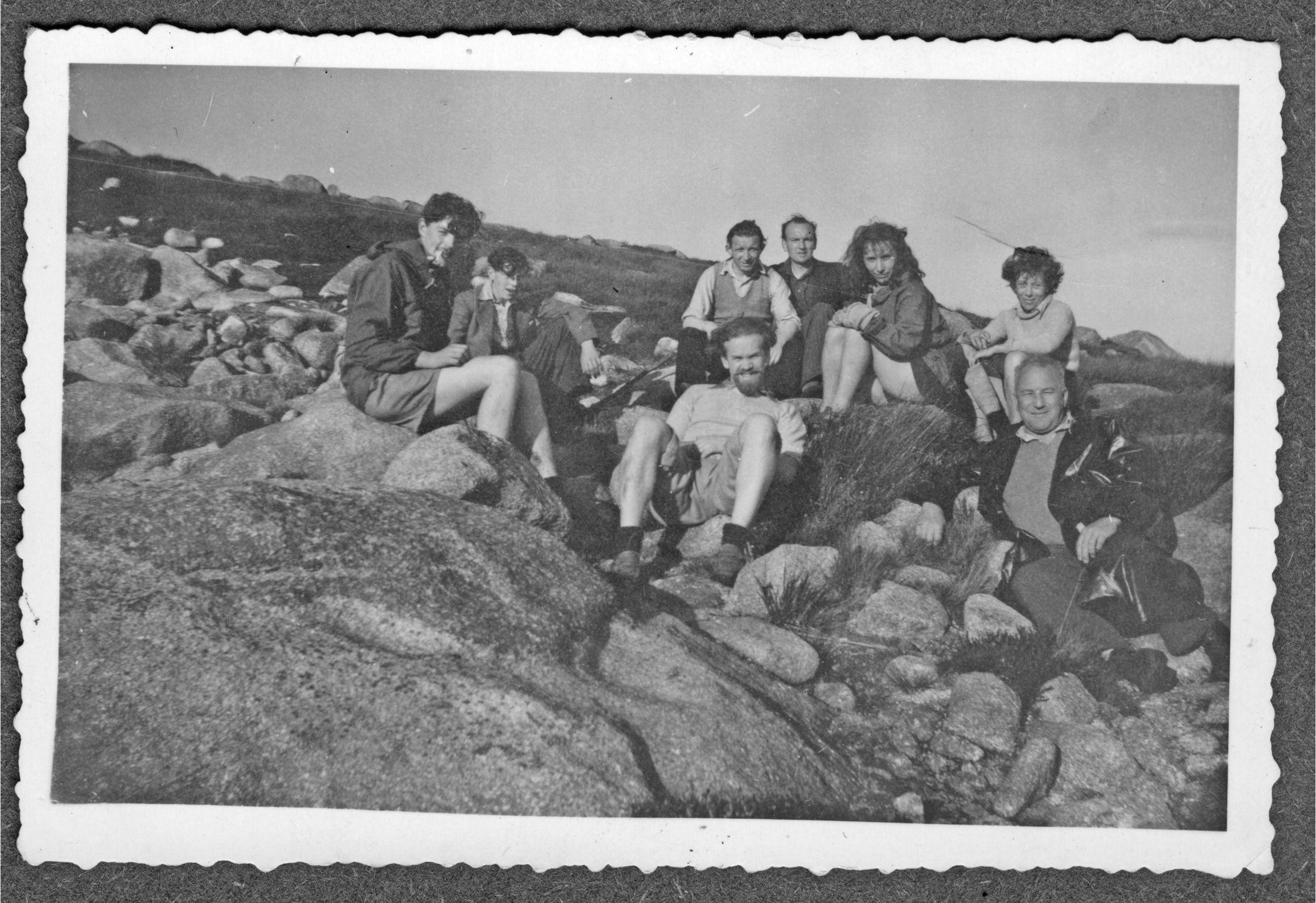

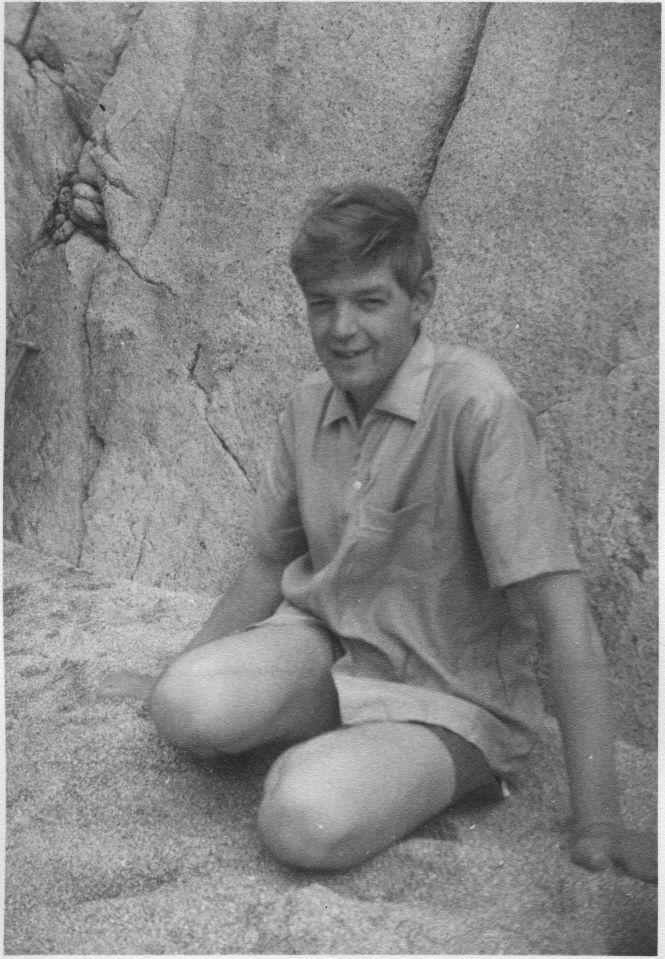

I would like to express my warmest thanks to Harriet and Ben Ward for their kindness, help, and patience. I am extremely grateful to Harriet for permission to quote from Colin Ward’s writing and to use photographs from the family’s private collection. I would also like to acknowledge Eileen Adams, David Downes, David Goodway, Ken Worpole, George West, Dennis Hardy, David Crouch, Anthony Fyson, Jonathan Croall, and Richard Mabey for their generosity in sharing memories of Colin, and to Soledad Perez Martinez for discussing her research with me.

I am grateful to the Town and Country Planning Association (TCPA), Freedom Press, and Lib.Com for making important archival materials free and accessible online. I am especially obliged to the TCPA and Resurgence for granting permission to quote from their publications. Thanks also to the staff at the International Institute of Social History for their efficient assistance. Special thanks to Emily English for her excellent research assistance skills and to Matt Higgins and Katherine Mager for their help in preparing the images.

Thank you to David Goodway, whose idea this all was in the first place, and to John Roberts, Thomas Linehan, Craig Fowlie, Daniel Andrew, and Hannah Rich, the Routledge editorial team, for their enthusiastic support from the outset. Thanks also to Peter Wilkin, Stuart White, and Geoff Hinchliffe who read or commented on aspects of the project at different times. A special note of appreciation to Carole and Michael Harris for their (timely) help with London geography.

Abbreviations

Archival Collections

| CWP | Colin Ward Papers, International Institute of Social History |

| TGP | Tony Gibson Papers, International Institute of Social History |

| VRP | Vernon Richards Papers, International Institute of Social History |

Institutions/Organisations/Associations

| FP/G | Freedom Press/Group |

| GAG | Glasgow Anarchist Group |

| LAG | London Anarchist Group |

| LSE | London School of Economics |

| PM | Peace Movement |

| TCPA | Town and Country Planning Association |

| C/USC | Council (of)/Urban Studies Centres |

Magazines, Journals, Periodicals

| A | Anarchy |

| AJ | Architect’s Journal |

| BEE | Bulletin of Environmental Education |

| NS | New Society |

| NSS | New Statesman and Society |

| SW | Spain and the World |

| TPCJ | Town and Country Planning Journal |

| WC | War Commentary |

Introduction

For Colin Ward, anarchy was ordinary, everywhere, and always in action. It happened on city streets, allotments, and around kitchen tables, in village halls, town squares, and pub snugs. It went about its business quietly, beneath and beyond official notice. Anarchists were anyone. Sensible, modest, and resourceful people without a bomb between them. They built houses, grew food, and ran workshops. When a thing needed doing, they banded together but parted their ways when done.

Beneath this calm, orderly facade lay startling claims. Schooling is organised mass ignorance. Centralised welfare is coercion by stealth. Ramshackle shanty towns contain more human dignity than the palatial creations of feted architects. For all that these ran counter to accepted ideas of social progress, in Ward’s hands they seemed intuitive, like remembering something already known and just briefly forgot. Any reader of sound judgement and good character was hard pushed to object. And yet this was anarchism, the ideology defined, surely, by disorder and destruction. What had this to do with ‘common sense’?

This book explores Ward and his everyday anarchism. Focusing on his role as a propagandist, a communicator of anarchist ideas, it examines how he crafted a ‘vernacular’ anarchism and transformed the impossible dream into a daily routine.

Talking Colin Ward

Ward was born in 1924, in Wanstead, Greater London. An unwilling schoolboy at Ilford County High School (ICHS), he left formal education at 15, becoming first an assistant building surveyor, later an architect’s assistant for Sidney Caulfield, the last living member of the Arts and Crafts generation. Conscripted in 1942, he was posted to Scotland, where he encountered the Glaswegian anarchists, began contributing to War Commentary (WC), the newspaper of the Freedom Press (FP), and stood as a witness for the prosecution in the FP trial (April 1944). From there, his relationship with the FP group flourished, and on demobilisation, he became an FP editor and writer for Freedom (the title War Commentary was abandoned after 1945), most notably through his column ‘People and Ideas’, at the same time as pursuing a parallel career in architecture.

In 1961, Ward launched Anarchy: A Journal of Anarchist Ideas, a monthly journal which, while remaining under FP’s umbrella, pursued a distinctive political project, exploring anarchism across the fields of education, housing, work, and crime. Through Anarchy, thinkers such as Murray Bookchin (writing as Lewis Herber) and Paul Goodman became more widely known amongst a British radical readership. After a decade at the editorial helm, in 1971 he moved on, taking up a post as Education Officer for the Town and Country Planning Association (TCPA) sparking another creative period in environmental education, during which time he began to write and publish book-length works, alongside articles. From 1979, Ward, now living in rural Suffolk, settled into life as a self-employed author, generating an extraordinary output of more than 30 collaborative and sole-authored books until his death in 2010.

The characteristic features of his anarchism are generally agreed upon: pacifist, gradualist, and, above all, practical. In politics he championed decentralisation, federation, and localism; in society, mutual aid and voluntarism; in economics, human need. He called for workers’ control in industry, citizens’ control in planning, dwellers’ control in housing, and students’ control in education. For some, he represented the shift from 19th-century classical anarchism to the so-called ‘new anarchism’[1] which, with its increased concern for culture and identity, practice, and prefiguration, became a dominant strand in the 1960s counterculture. ‘New anarchism’, with its stress on methods, functioned more as an adjective for describing an ‘ethics of practice’ than as a proper noun for a formal movement.[2] As Stuart White observed, adopting such a flexible stance allowed Ward to reconcile the social and individualist strands of the movement and bring anarchism further into mainstream consciousness.[3]

Others, by contrast, saw ‘new anarchism’ as only the latest incarnation of a pre-existing ‘pacifist-spiritualist’ tradition, rather than a specifically mid-century phenomenon, which had always stressed non-violent forms of direct action and individual transformation.[4] From the perspective of more ardently inclined revolutionaries, this amounted to reformism, a critique repeatedly levelled at Ward by several of his contemporaries.[5] For these critics, working within and through existing social structures (or retreating from them altogether) only deferred permanent transformation indefinitely. Tactics for perpetual resistance or selfimprovement did not amount to a systematic revolutionary strategy. Further, Ward’s affectionate case studies of grassroots populism downplayed the problematic dimensions of voluntary association in hierarchical societies (vigilante groups, for example, are voluntary), nor did they indicate how isolated examples might stimulate more comprehensive change.[6]

Ward’s relationship to the 1960s counterculture was also not straightforward. Although certainly conversant with it, he could not, as Goodman in America, be considered its forefather. There were significant differences between his invocations of ‘everyday life’ as a sphere of meaningful political action and the ‘personal politics’ of, for example, feminist activists. Where he laid much stock in invoking ‘common sense’, the latter sought to challenge, and disrupt, the very notion of it. He was equally distant from the cultural critique advanced through later youth-orientated movements: punk, the rave scene, or the militant components of the green movement.[7] His favourite characters, allotmenteers, art teachers, or housing co-operativists, may have been on the fringes of society but they were not social outsiders; if anything they were quite the reverse.

Taking this point further, in the wake of so-called post-anarchism,[8] with its evermore refined cultural sensitivities, Ward and other thinkers of his generation retained a relatively unproblematic view of the universal human subject. Although accepting conflict as an inevitable, even creative, part of an authentic democracy, and embracing liberation in all its guises on principle, the specific barriers to full participation encountered by many social cohorts — such as women, ethnic minorities, or the LGBTQ+ community — were never examined in close detail. His could-be anarchists were generally white, English, lower- middle-class men (and occasionally their wives). He accepted this, perhaps too easily; ‘anarchists are products of their times’, he told an interviewer when asked about the attitudes towards women in the anarchist movement of his youth.[9] Of course, this was true, and, in his case, the awareness of the present and concern to write anarchism into it was what made him so interesting; nevertheless, it meant certain limits.

Locating Ward’s Anarchism

Ward identified as a social anarchist which, situated at the intersection of liberalism and socialism, considers social equality as the necessary pre-condition for individual liberty. Unlike other attempted syntheses, such as social democracy, or even strains of libertarian socialism, which still entertain some role for governance, anarchists are distinguished by maintaining that only through the complete abolition of all permanent authoritative structures could such a reconciliation be either logically or practically possible.

Ward identified most with Pyotr Peter Kropotkin (1842—1921),[10] describing his work as an ‘updating footnote’ to the Russian’s main ideas.[11] As Kropotkin co-founded Freedom in 1886, it was inevitable that generations of its editors took him for their major influence. In essence, Kropotkin’s anarchism took humans to be fundamentally social beings whose individuality was most enriched through the highest development of their capacity for voluntary association. Throughout history, however, this was perpetually thwarted by an opposing political or authoritarian tendency (the state) which, given its characteristic excess of power, was always the stronger. Only with the destruction of all divisive political and economic structures could the social instinct realise its fullest expression. For Kropotkin, the optimum social model for achieving this end was communism.[12]

Beyond this, it gets harder to specify. There were several possible ‘Kropotkins’ one could update dependent on inclination: the revolutionary-strategist,[13] the natural(ist)-philosopher,[14] or the observer-activist.[15] Ward favoured the third and took bits from the others to taste, supplementing this with nuggets gleaned from other classical anarchist thinkers. He found Pierre Joseph Proudhon’s ideas of limited property ownership, small-scale enterprise, and gradualist transformation more prudent for his times than revolutionary communism.[16] William Godwin’s attitude of unconditional respect for children’s individuality[17] meant more to him than any radical school or curricula design (especially when leavened by the penetrating compassion of Mary Wollstonecraft).[18]

In other respects, Ward belonged as much to an English radical tradition as to a strictly ‘Anarchist’ one, especially if the former is viewed as a political style rather than a defined ideology. He relished outspoken independence, those maverick individuals who stubbornly followed their conscience when it swam against the tide. Amongst those singled out with affection were architect William Richard Lethaby who transformed art and design education, Ebenezer Howard of the Garden City Movement, Patrick Geddes the champion of regional planning, AS Neill of Summerhill school, Dora Russell of Beacon Hill,[19] George Orwell, of course, and alongside him, the more obscure novelist and journalist Edward Hyams.[20]

Certainly, he considered himself in this light, describing to a bemused editor how he was the ‘archetype of the English Radical with no academic or theoretical background, who, in a maddening unsystematic way will draw what is useful to me from every possible source’.[21] That said, the Englishness of this tradition was never an especially conscious concern for him. Whilst localism was important for inspiring commitment, grounding ideals in context, and channelling action into a ‘human scale’ framework, he was not patriotic in the manner of Orwell. Nor did he consider the dissenting spirit a unique national product but found it with equal vigour across European thinkers, in architects Giancarlo di Carlo and Walter Segal, philosophers Martin Buber and Isaiah Berlin,[22] and, from North America, in Mark Twain and Goodman.

Another formative but complex influence on him was the British Labour movement, especially the ‘ethical socialist’ strand of it.[23] Labour was the family politics with both parents Party members. During the interwar years, Labour exercised considerable influence in the Barking and Dagenham area (where his father worked for most of his life) by emphasising a local, ‘domestic’ agenda: social welfare, education, housing.[24] Following the war, as a Freedom writer he was naturally critical of Parliamentary Labour and the welfare state but remained consistently sympathetic to figures like GDH Cole.[25] He had respect for the ethos of the early Fabian society, in particular their commitment to detailed research and gradual change through cultural permeation,[26] and considered this legacy continued by the ‘new social investigators’ (including Richard Titmuss, Peter Townsend, Michael Young, John Vaizey, and Barbara Wootton).[27] Late in life he confessed he remained ‘very much a Labour man at heart’.[28] In this sense, anarchism, far from displacing the Labour values of his youth (equality and social justice) only substantiated them more fully.

Kropotkin, however, remained the most consistent focal point for his thought perhaps because, across the Russian’s voluminous writings, all the various threads of his interests came together. But in resuming his ideas, Ward revised them. Naturally, the Russian was a man of his time and drew on the dominant theories and rhetorical habits appropriate to them. His credibility as an intellectual, and appeal as an activist, would have been undermined if he had not. As with many of the influential intellectuals of the age, he was of a synthesising mindset, convinced of accumulative progress through reason aided by the flourishing of science.[29] He could also take the possibility of total social revolution as entirely plausible, even inevitable.

By the turn of the century, that confidence had fractured as the impact of Darwin in the natural sciences, Nietzsche in philosophy, and Freud in psychology was fully absorbed. Amongst the anarchists, many now felt Kropotkin relied too heavily on science, even conflating the scientific ‘is’ with the ethical ‘ought’.[30] Errico Malatesta argued that while scientific knowledge could be useful it was neither moral nor stable. It could ‘prove’ the contrary as much as the case.[31] The notion that a single revolution could, let alone would, destroy the state also looked naive. German philosopher Gustav Landauer addressed the problem by recasting the state as ‘a certain way of people relating to one another’ which could be destroyed through acting differently.[32] This shift acknowledged more fully the role of both individual and collective psychology in the production of power, something which had been, if not absent, underplayed in Kropotkin’s system, especially with regards to the former. His individuals were often ‘figures in a landscape’, producing food, building houses, and carrying out scientific research with relatively few existential musings.

Writing in the early 19th century, British anarchist Herbert Read deepened his interest in anarchism’s psychological dimensions.[33] Anarchism conceived as a form of intimate human self-knowledge, related to one’s own experience and applied to one’s own fields of interest, meant that the urgency of violent revolution, along with the complex webs of factions, federations, and organisations attendant upon it, diminished in importance compared to the more private work of individual mind change. Not all welcomed this move sensing bourgeois elitism and the gateway to an increasingly depoliticised ‘lifestyle anarchism’. Nevertheless, such an expansion was crucial for cultivating a wider audience for anarchist ideas.

For Ward, coming of political age later still, during the Second World War and the post-war, Cold War decades, revolution, as a single cataclysmic event, looked both unlikely and undesirable. Nor did the socialist movement appear to be the prime vehicle through which revolution would be realised. This was a period of dramatic social transformation during which Britain experienced the collapse of empire and withering of its imperial power, the consolidation of the welfare state, the rise of America as a global power, and the uncertainties of the

Cold War. Austerity was followed by an ‘age of affluence’, fuelled by unprecedented rates of consumption, huge technological advances in industrial production, transport, and mass media, the decline in manufacturing, and growth of service industry informing and informed by the expansion of education and higher education, generating an enlarged student body and a swelling stratum of ‘professional’ jobs.

Politically, the left seemed weary and directionless. Following the Khrushchev revelations and invasion of Hungary in 1956, the great Soviet experiment was, for many, discredited. In the British Labour Party, the aspirations of social democracy dwindled into welfarism and bureaucracy.[34] By 1960, American sociologist Daniel Bell declared ‘the end of ideology’ and the effective triumph of liberal capitalism. Resistance, he predicted, would become ever more piecemeal, impermanent, and parochial.[35] As Jimmy Porter notoriously wailed, there seemed no more brave causes left, a lament reflected in the rise of the cultural anti-hero (like Porter) whose attempts at trying to get on, or just by, left little room for aspiring to anything noble.[36] With faith in formal politics, in all its guises, at such low ebb, it seemed, an open invitation, to ‘re-discover’ anarchist traditions.

Ward did not think that modern anarchism was condemned to permanent resistance alone, nor that it was necessary to abandon revolutionary sentiments altogether, only to reframe them.[37] Writing of the relationship between classical anarchism and its contemporary form in the late 1950s, he said of the latter ‘it rejects perfectionism, utopian fantasy, conspiratorial romanticism, revolutionary optimism; it draws from the classical anarchists their most valid, not their most questionable, ideas’.[38] Taking his own advice, he accentuated the more gradualist aspects of Kropotkin, turning the so-called ‘problems’ of the age into potential opportunities. Ideological fragmentation was not disastrous if it could lead in the direction of political decentralisation. The middle classes, swollen through education and the growing ‘semi-professions’, were not your traditional ‘workers’, granted, but a receptive audience on topics such as practical education and autonomous social organisation.[39]

In conversation with his times, he recast anarchism from a historical romance (or modern tragedy), into a late-modern picaresque: no matter how great the knocks and small the gains, anarchistic tendencies invariably bounced up again somewhere else. Stripped of any comforting sense of destiny, it was more important than ever to stress anarchism as a continuous presence and existing tendency, already rooted in the most fundamental, and familiar, structures of everyday life. The figure of the revolutionary had also to be repackaged for the mood of the times. Passionate feats of heroism were out, small acts of common decency, undertaken in sincerity, were in. His social histories of self-help and his own public persona as an anarchist ‘everyman’ all helped naturalise this.

Where he substantiated, he also refined. As Malatesta had objected, Kropotkin’s application of the natural sciences to the social could be a blunt instrument. To address this, Ward engaged closely with developments in sociology, a discipline with which he felt a natural affinity. His take up, however, was cautious, closer to the quasi-literary tradition of British social writing than anything more formally theoretical.[40] In a letter to The University Libertarian (December 1955), he commented:

I do not believe that the social sciences are objective like the physical sciences. I think they find what they are looking for and I would like them to look in the direction of freedom, autonomy, free association and spontaneity.[41]

His interest in the social sciences was partly strategic. In the post-war decades, sociology flourished in the universities and was the intellectual langue de jour.[42] Connecting it to anarchist ideas helped towards the goal of ‘putting anarchism back into the intellectual bloodstream’,[43] forging a bridge with a new generation of social thinkers[44] and inviting them to connect their ideas with anarchist ones.

To stress Ward’s work as a continuation of Kropotkin’s key ideas is not to detract from his intellectual creativity but to understand it as renovation, rather than innovation. He was fond of this metaphor and the virtues it implied — thrift, attention, and resourcefulness — all essential qualities for the aspiring activist engaged in a gradual, organic (r) evolution.[45]

Anarchist in Action

The discussion above sets out a framework for Ward’s anarchism but does not address his specific intellectual role. He considered himself a propagandist and was prepared to defend that role.[46] In the Talking Anarchy conversation with David Goodway, when described as one of the 20th century’s great anarchist thinkers, he replied firmly: ‘I am not a great thinker. I simply apply a few basic anarchist ideas to the ordinary situations of life’.[47] In another interview with Tony Gibson, a fellow anarchist and psychologist (1992), he stated ‘now one thing I’m not is original and this simply reflects that [people] haven’t been exposed to an anarchist point of view before’.[48]

As with his deferral to Kropotkin, his insistence on the role of propagandist has been dismissed as modesty, but for him, radical propaganda through independent journalism was a distinctive craft which he took seriously, gave considerable thought to,[49] and served an unofficial apprenticeship in. For the post-war FP group, it was Malatesta who most informed their approach to propaganda.[50] ‘Our task’, the Italian wrote in 1931,

is that of ‘pushing’ the people to demand and to seize all the freedom they can and to make themselves responsible for providing their own needs without waiting for orders from any kind of authority. Our task is that of [...] provoking by propaganda and action, all kinds of individual and collective initiatives.[51]

Ward absorbed these principles through his friendship with Richards and via the FP group’s working culture. It was, however, Alexander Herzen (1812— 1870), the 19th-century Russian writer, who provided his personal model of an ideal propagandist.[52] Conversely, for a propagandist, Ward considered Herzen’s refusal to urge people to take up a cause, no matter how noble, to be his greatest strength.[53] Instead, he had offered alternative ideas as ‘gifts’, rather than prescriptions, through his writing: ‘[Herzen] considered that simply to spread enlightenment is, in the long run, more important and more truly revolutionary’.[54] He later named Herzen as his main political influence, reinforcing his view of politics and political communication as inextricable.[55]

Emphasising propaganda shifts the framework for understanding and judging Ward as a thinker. His goal was not to develop a theory but to spread ideas among a wide general audience. So central was this objective that, even when disagreeing with the ideas, or approaches, of fellow anarchists, he could still commend them for their contribution to the circulation of ideas. ‘As a propagandist myself’, he once said, ‘I value other propagandists by their effectiveness in winning uncommitted people to an anarchist standpoint’.[56] He refused to join the chorus of public critique around Richards, who could be notoriously difficult, crediting him for ‘making sure propaganda by the printed word actually happened’.[57] He also expressed admiration for George Woodcock, Herbert Read, Murray Bookchin, and Noam Chomsky for their cultivation of a large general audience: ‘unlike the rest of us, they have broken through the sound barrier that limits other anarchists to a small minority audience. They have succeeded in battling through to a large minority audience’.[58]

Woodcock was especially significant during his first years as an anarchist writer in the 1940s, providing an early example of applying anarchist ideas to contemporary culture and social issues through his pamphlets on land, the railway and housing, his articles on regionalism and his attempts towards a regular cultural column. After Woodcock’s departure in early 1949, Ward gradually assumed this role within the group through his column series ‘People and Ideas’.

For all this, however, Ward was something of a propaganda connoisseur. Whilst alert to the power of the spectacle, good propaganda, he believed, had the ability to live beyond the event, to generate and sustain future activity. In Cotters and Squatters (2002), for example, he distinguished between squatting as ‘a political demonstration’, intended to make a statement, and squatting as ‘a personal solution to a housing problem’ which tried to be inconspicuous, longing for stability and respectability.[59] Theoretical revolutionaries, he supposed, may resent those adopting temporary personal solutions as conservatives but the practical revolutionary respectfully understood those desires. Similarly, in a lecture on ‘The Green Personality’, he commended the youthful road protestors of the 1990s on their iconic tree-top villages but observed that this was unlikely to resonate with how most people wished to live their daily lives in the long term.[60]

As such, this concern with reaching a popular ‘non-committed’ audience placed a layer of strategic subtlety over his work. As a self-confessed ‘empirical softie’,[61] he was open to trade-offs with the popular mood that the more austere of his fellow anarchists would not have been. This, then, may help to contextualise points at which his ‘theoretical’ stance and ‘practical’ writings seemed inconsistent, such as on possible roles of or for the state in creating housing co- operatives.[62] Rather than judge his work in terms of its theoretical coherence, it yields more to consider each piece in context, linked together by recurrent core principles. Moreover, as theoretical exegesis was not his primary goal it is unhelpful to assess him on that basis. Better questions concern the efforts he made to reach his wider audience and his relative success in doing so. Even so, while this may provide a richer context for understanding Ward as an individual, what can a case study of a propagandist, even a skilful one, tell us about the intellectual development of modern British anarchism?

Propaganda, the use of symbols to promote or induce action, is one of the rhetorical arts.[63] For most of modern Western intellectual history, rhetoric has been viewed in a secondary, even oppositional position to the analytical rigour of philosophy or science. In recent years, this view has been challenged,[64] aided by the ‘recovery’ of a humanist tradition which held it to be a form of philosophical inquiry in action.[65] This tradition, recognising the role of language and aesthetics in mediating experience, considers meaning-making to be a social activity. For the propagandist, preoccupied with the public in a way the theorist is not, this idea resonates. To be effective, they must connect with their audience’s existing concerns and desires directly. For any political group, success depends on the capacity to spread ideas, but for anarchists, who place spontaneous popular movement at the heart of their philosophy, the stakes are higher still. Voluntary direct action does not just realise anarchism, it defines it. For anarchists, then, persuasion is paramount.

Given this, it is unsurprising that concern with and for the composition, conduct, and consequences of propaganda is an outstanding feature of anarchism, not least through its (in) famous (and, arguably, misunderstood) preoccupation with the propaganda of the deed.[66] But the situation becomes more complicated still if, like Ward, you believe anarchism to be an open-ended outlook rather than a finite outcome. Now you are no longer just explaining a doctrine or prescribing a set of actions that will lead to an anarcho-communist society. You are attempting to implant and consolidate a whole habit of thinking.

Ward’s work, then, was not a simplistic transmission of anarchist ideas dressed up a la mode. By deliberately connecting those ideas to areas of contemporary common experience, he not only made them palatable and interesting but also possible. These were the places where anarchistic qualities could already be discerned, however faintly, and where they could, therefore, be best cultivated. In so far as these connections generated action and new forms of lived experience, they also, in turn, fed back and altered anarchist ideas, making propaganda as much a method of revision as a tool of promotion.

How did he do this? To quote him directly, he worked from (italics my own) ‘the common foundation of common experience and common knowledge’,[67] which was shrewd in that, as Kenneth Burke observed, ‘the ideal act of propaganda consists in imaginatively identifying your cause with values that are unques- tioned’.[68] In effect, Ward ‘reframed’ anarchism, opening it up to a new, uninitiated, audience. Firstly, he exchanged outdated metaphors inherited from classical anarchist culture — such as ‘the workers’ (meaning an industrial working class), or the Spanish collectives — with more accessible ones such as holiday camps, allotments, community health centres, adventure playgrounds. Secondly, he assembled a collection of choice quotes (he freely admitted that he ‘thought in slogans’ himself[69]) which compressed complex ideas into handy mnemonics which expressed ‘valid and valuable’ generalisations.[70] Finally, he identified and described sustainable methods for converting symbolic imagery and general principles into practice. Starting a community garden, for example, was much more feasible for most people than bringing down a government. One was also more likely to pursue community gardening long term.

Methods and Sources

This book takes a biographical approach to examine how Ward fashioned his vernacular anarchism. As noted above, successful propagandists are astute cultural readers, integrating their ideas with the wider conditions of their times to stimulate readers to action. Charting the changing patterns and forms of propaganda can reveal much about the evolution of a political group’s thought but why, then, distil this into a single life story? Biography offers an intimacy that a broader cultural history cannot. It magnifies the situational logic which forms through the interplay of an individual’s lived experiences and the ‘local’ factors which they encounter. It is, then, intellectual micro-history, attentive to the improvisational nature of thinking which is especially important when considering a process of culture change up close.

That said, the focus here remains on the life as it informed the work, which means that it selects and explores those contexts taken to be most germane to Ward’s political development and practice. Naturally, this includes tracing his political ‘education’, his unfolding relationships with fellow anarchists, especially the FP group, and with other political groups or individuals, but, while these areas comprise his most conscious political activities, they are not enough. This study also includes a wider view of those areas that were equally vital but indirectly so: his family, in childhood and adulthood; his work life in architecture, education, and self-employment; his ‘non-political’ friendships. It was these spaces, it will be argued, which enabled him to innovate with anarchism.

Given the attention on propaganda, alongside close contextualisation, this book also draws on critical rhetorical analysis to excavate the techniques Ward deployed in generating his ‘new’ anarchist imagery. As he was first and foremost a writer, these mostly concern his texts and include identifying his recurrent metaphors, narrative strategies, and intertextual references through which he forged wider cultural connections. When approaching his self-presentation, how he styled himself as a public figure (typically in terms of a written ‘narrative self’, although, in later life, this was extended into a media personality through public lectures, radio broadcasts, and television appearances), I take inspiration from Erving Goffman’s juxtaposition between frontstage as conscious public performance (high stakes, desiring to influence) and backstage as private life, relatively unobserved (low stakes, no one needing to be convinced).[71] Contrasting his public and private selves demonstrates the degree of deliberation employed in crafting the outward image.

This last point has special importance when considering the existing autobiographical sources on his life. Ward refused a request for his life story, explaining that,

I have read plenty of such books and have seen how the first few chapters are the most absorbing, after which they tend to trail off into a catalogue of names, jobs and encounters. This in itself is a depressing thought. How can it be that for many people everything after childhood is an anti-climax. And I’m mindful too of Orwell’s sharp comment that an autobiography that is not a history of failures is a pack of lies.[72]

This seems an odd comment given the rich tradition of radical autobiography.[73] Ward himself greatly admired Alexander Herzen’s My Past and Other Thoughts and wrote an introduction for a Folio edition of it ([1870] 1983), as he did for the Kropotkin’s Memoirs of a Revolutionist ([1899] 1978) and Rudolf Rocker’s The London Years ([1938] 2005). Moreover, given his view of anarchism as work in progress, presenting a ‘history of failures’ was potentially instructive. As Australian anarchist George Molnar joked, ‘freedom has always had a hard road to tread, as the biography of any anarchist will amply prove’.[74] Still, he was resistant.

While a single-authored account of his life did not appear, there are several important semi-autobiographical sources. These include Influences (1991), his personal scrapbooks which date from 1941 to 2006, and three interview conversations, one with David Goodway published as Talking Anarchy, first published in 2003, another, unpublished, by Tony Gibson, a fellow FP Anarchist, conducted in 1991, and a film, ‘Colin Ward in Conversation with Roger Deakin’ by Mike Dibb, filmed in 2003. Then there are the anecdotes scattered across his regular columns including Town and Country Planning (‘People and Ideas’, resumed from Freedom, from 1979), New Society (‘Personal View’ from 1979), and later New Statesman and Society (‘Fringe Benefits’ from 1988).

Influences was a collection of essays discussing his favourite writers. The book is hard to categorise which makes it interesting and revealing. It was too personal to be anarchist literary criticism in the manner of Woodcock’s The Writer and Politics (1948), but too impersonal to be a memoir. It most resembled a propagandist’s commonplace book, a repository for the quotes and passages he built his arguments from. In it, he arranged this reading matter according to the themes — education, politics, society, economics, planning, and architecture — he found they most spoke to. Given his life as a journalist, in which role he continually filleted reading matter to reassemble elsewhere, such a collage of fractured texts, was a fitting intellectual self-portrait.

This idea of life-as-anthology resonated well with his anarchist understanding of the social self. As he described it:

if you want to see the way a writers’ mind works there is nothing more illuminating than the multitudinous sources with which he works [...] We all live on what we borrow from others, from the past, from the enormous accumulation of printed words which comes our way in a lifetime. There is a continuous process of selection, rejection and assimilation. What is interesting, what is really us, so to speak, is what we assimilate.[75]

Seeing him through his sources and scraps provides fruitful insight into his mind and methods.

Nevertheless, both Influences and the scrapbooks are light on empirical details. The TA conversation with Goodway is more generous in this respect and, for this reason, is the best known and used source for Ward’s life. In addition, it also reveals the lengths he went to maintain that control over his public persona. The interview was not conducted face to face but, at his suggestion, by correspondence. This had the benefit of retaining a dialogic quality while permitting him the time to consider and compose his answers. He did this with care, often rephrasing or even adding his own questions.[76] Where there was a gain in depth of detail, there was also a loss in spontaneity; writing allowed him to reflect, control, and self-edit as he went.

In the preface to the second edition, Goodway confessed that his (deliberate) efforts to generate any dramatic tension had been steadfastly thwarted.[77] For example, despite professing an interest in the sociology of group dynamics, when asked about the inner workings of the FPG group or on the wider anarchist culture of the time, Ward’s replies were sparse, even defensive. Picking up on a slight suggestion on friction between factions, Goodway asked: ‘that’s an interesting remark! Who stayed aloof?’ The reply was gentle but dismissive, ‘I think it is inevitable rather than interesting’.[78]

This refusal to be drawn into indiscretion on controversial characters or situations was just one of several points at which he actively deflected Goodway’s questions. In conversation, this is a confronting strategy, amounting to a refusal to validate his interviewer’s opinion. Here again:

Colin, you are such a generous person, always unwilling to be critical of fellow anarchists. Yet you imply that there are ‘things’ which ‘divide’ you from Murray [Bookchin]. Is it simply a matter of higher theory, of style and changing opinions?

The opening compliment was a statement, not part of the question, and not intended to form part of the response, but Ward deliberately picked up on it:

It isn’t that I am kind or generous. It is simply that I take seriously the business of being an anarchist propagandist [...] nothing makes us more ridiculous in the eyes of the world outside than the internal factional disputes that some anarchists enjoy pursuing.[79]

He offered no further comment on Bookchin.

The Tony Gibson interview, recorded face to face a decade earlier, was more spontaneous but again he was given the chance to comment and amend the transcript (he made few changes). Gibson was older than he, a psychologist, and had been associated with the FP group for a long time. He could ask detailed, targeted questions about the FP group’s more intimate history, and probe at places Ward may have preferred to omit. But, in focusing primarily on FP, the interview contained few details about Ward’s life outside of the movement, such as his work or family.

As noted earlier, the anecdotes, characteristic of his later column writing, offer another source of self-writing. Although these do contain more intimate details of his daily life, they also fulfilled a political function. He used his ‘self’ as a cypher for his favoured anarchist stock character, the hapless ‘everyman’, bewildered at the absurdity of the world but also deeply sensible. This figure was intended to assure his readers of their own deep sensibility. The domesticity of the columns’ settings (in railway stations, on day trips, in his home village), and the apparent triviality of the stories (a stolen bike, buying a magazine from a newsagent), were intended to reinforce his arguments for anarchism as an everyday practice. It is reasonable to expect, then, that their truth content was stylised.

To discern more clearly the omissions and to thicken the contexts in which he worked, I have drawn on archival holdings in Institute for International Social History. Alongside Ward’s papers are housed those of Vernon Richards and FP associate Tony Gibson who conducted a series of oral interviews with members of the FP circle in the early 1990s. In addition, I have used Home Office papers held at the National Archives detailing the events surrounding the Freedom Press trial, the Town and Country Planning Association Archives (in reference to his position as an education officer and the Bulletin of Environmental Education which he edited), British Library oral recordings of British architects, and oral transcripts of an interview conducted with surviving members of the Glasgow Anarchists.

Where possible, I have conducted original oral interviews and interviews by correspondence with family, friends, colleagues, and collaborators including Harriet and Ben Ward, George West, David Downes, Dennis Hardy, David Crouch, Ken Worpole, Eileen Adams, Jonathan Croall, Anthony Fyson, David Goodway, and Richard Mabey but, again, it is striking how consistently Ward maintained a reserve, especially on his childhood and young adult years, even with his closest family. He may have believed that the personal was also political, but he also preferred modesty and discretion, ‘private faces in public faces’.[80] Here, then, is a part and partial history of a very ordinary anarchist.

1. The Forward View

Whenever he was asked how he became an anarchist Ward’s usual response was to dash lightly over his first 18 years and arrive at the point of ‘conversion’, in Glasgow, autumn 1943. But epiphanies only feel unexpected; the groundwork that makes them possible has usually been long in the preparation. How was it possible for him to have been ‘won for anarchism’?[81] What values, ideas, and inclinations made him receptive in the first place and what sort of anarchist had been won?

In The Angry Decade (1958), Kenneth Allsop, four years older than Ward, reflected on his generation. They had lived through the General Strike, the Depression, the war and its ‘epilogue of dreary years’, the atomic bomb — in short, they had known ‘a lifetime incessantly crisscrossed by catastrophe’.[82] Perhaps so, but on the other hand, these were also decades of increasing social mobility, of more scholarships for poor children, full employment during the war, emergent industries, and job opportunities, of new consumer goods: cars, washing machines, television. Importantly, this lurching between extremes — hope and tragedy, progress and loss — was not remote; it touched everyone. It was what underpinned Ward’s attraction to anarchism and, ultimately, directed his revision of it.

Wanstead, Childhood, and Youth

It is hard to develop the story of Ward’s early life as little survives in his personal papers from this time, and he rarely spoke about his childhood unless prompted, not even to Harriet (his wife), or his children. Silence can hide trauma, but lack of remark can also mean simply that experiences felt unremarkable. In Ward’s case, unremarkable was important.

His parents, Arnold Ward and Ruby Ward, nee West, were both born into working-class families on the East India Dock Road, London. Ruby’s father was a carpenter and, as with many self-employed tradesmen, reliant on the mercurial fortunes of the building industry. Life could be precarious with the need to seek out work constant, but the family were never desperate. The youngest of three sisters, Ruby was the favourite, and where her sisters were sent to work as soon as possible, she was encouraged to take secretarial training after she finished school. Clerical work offered a respectable means of self and social improvement. With a smart appearance, good diction, and a reasonable standard of written English, she could undertake ‘unskilled’ office work (skilled office work, such as that required for the civil service, required higher levels of education along with additional languages). Those, like Ruby, with an aptitude for the work could pick up shorthand qualifications, taken at evening classes, increasing their chances for higher-paid positions (she later became a shorthand teacher).[83]

Arnold’s father, originally from Ireland, was a ‘general dealer’. Like Ruby, Arnold was the youngest, and favourite, child. On completing the elementary levels at school, he trained to become a pupil-teacher. At 18 he passed the King’s scholarship examination to study at one of the new Local Authority-run teacher training colleges introduced following the 1902 Education Act, a qualification that permitted entry into senior positions, with higher salaries, in the profession. An instinctive, rather than official, pacifist, he bluffed his way to a job in a sausage factory during the First World War (protected, as food production, from conscription), later resuming his studies. In the early 20s, he attended evening classes at the London School of Economics (LSE), eventually gaining a BSc in Economics.[84] Eventually, he rose to a headship at Custom House primary school,[85] Canning Town, but, prior to that, and for most of Ward’s childhood, he taught in a series of schools around Barking and Dagenham.[86]

Since the mid-19th century, this borough had been subject to rapid growth and heavy industrialisation. Consequently, it had a high working-class population. Increasing employment opportunities, combined with proximity to central London and the comparative affordability of land, appealed to social reformers eager to address overcrowding in inner-city slums. Between 1882 and 1892, 7,000 housing development plans across the borough were approved. Following the First World War, London County Council (LCC) embarked on the Becontree estate, the largest ever government housing project, 24,000 houses on 3,000 acres of land encompassing Dagenham, Barking, and Ilford, formerly market gardens with clusters of cottages which were bought up through compulsory acquisition orders. Prospective tenants were interviewed to assure their financial and moral suitability, further reinforced by The Tenants Handbook which set out strict stipulations on standards of cleanliness and conduct.[87]

Arnold taught the children of those families, but his own family lived in neighbouring Wanstead which was considered genteel (from 1924 to 1964 Wanstead’s MP was Winston Churchill). Arnold and Ruby bought 8 Collinwood Gardens, a

three-bedroom semi-detached house with top and bottom bay windows, a front and back garden, on a quiet cul-de-sac of similar-looking houses. These ‘domestic-vernacular’ details marked it out as the handiwork of a ‘speculative builder’, one of the many who generated 50,000 more houses than the government managed during the interwar years, but always with the aspirations, and budgets, of a rising middle class (not an improving working class) in mind.[88]

Arnold and Ruby’s story could be seen as one of meritocratic social mobility: expanding educational opportunity plus individual endeavour. The couple made two moves, first joining a swelling stratum of salaried ‘semi-professions’,[89] teaching and clerical, and then a further ‘ascent’ following Arnold’s degree and promotion to a headship at a state-owned primary school. From another perspective, enhanced material prosperity aside, this was also a process of proletarianisation, a shift away from the self-employment of their parents to the status of employees, albeit, in Arnold’s case a high-status one.

But if his parents accepted the status quo and aspired to advance within it, this had an egalitarian spirit. Both had benefited from educational opportunities themselves and believed the same should be extended to others. Arnold’s school, Custom House Primary, taught children from poor families, children of dockworkers, whose parents would keep them off school for lack of shoes.[90] Over his years as a teacher, then headmaster, he saw first-hand the vicious cycle of poverty and the role schools could play in breaking it. As such, theirs was an active Labour-supporting household. For the Wards, and, initially, their two sons, the Party took the place of any formal religion in providing the main moral outlook for their lives.[91]

During the interwar years, Labour transformed from a relatively marginal political force into the only credible alternative to the Conservatives as a party of governance. In 1924, the year Ward was born, the first Labour government took office. It was short-lived, lasting only 9 months, ousted because of accusations of Bolshevism which, as Matthew Worley points out, was ironic because during this period Parliamentary Labour strove to assert itself within the establishment, pursuing a moderate agenda. For ideological hardliners, like George Lansbury, the sight of Labour MPs donning formal dress, working men taking their place alongside the members of a cultural elite, was incongruous.[92]

The consolidation of respectable credentials, when combined with the Baldwin government’s calamitous handling of the General Strike, returned them to power in 1929. Again, success was fleeting, the internal split over cuts to unemployment benefit prompting another collapse in the summer of 1931. Nevertheless, important ground had been gained. Labour was also beginning to enjoy success at local levels. In 1934, the Labour Party gained control of the LCC, and, led by Herbert Morrison, retained it with an increased majority in 1937. While in office, they launched an offensive on the capital’s slums, increasing expenditure on housing, education, and health. As Naomi Woolf, a Labour councillor for Hammersmith from 1934, recalled: ‘the domestic political thing — that was the basis of the labour party [...] housing and health I think dominated the Labour Party at that time’.[93]

The Party still faced serious obstacles on their road to becoming a parliamentary force. Their organisational and funding structure remained rooted in the staple industries of the 19th century, leaving them poorly equipped to engage with the emerging new industries, such as transport, artificial textiles, chemicals, and electricity,[94] and, therefore, the new forms of work, and workers, these generated. The Party also encompassed a complex ideological blend, where the ends and interests of working people, trade unionists and socialist intellectuals often contradicted, causing division over the proper direction it needed to pursue.

In some ways, however, ideological clarity was less of a priority at this point than gaining and retaining power. There was a widespread sense that practical electoral work, rather than intellectual debate, was the business of the day. What Labour lacked in cars and money, it made up for in volunteers and energetic canvassing. With this came a shift in political culture from the ‘tub thumping’ of the old politics to the more artful means of persistent persuasion at grass-roots levels, a more ‘scientific’ approach, privileging structure and organisation over reliance on charismatic personalities and gifted orators.[95] Arnold and Ruby were two such volunteers, using the family car to ferry prospective voters to the polls on election days. Arnold was probably active beyond this given that the headship of his school was in the gift of the Labour borough council.[96] As such, it might be reasonably supposed that left-leaning newspapers, Party literature, perhaps even discussions on political strategy were commonplace in the household.

But the internal struggles of the Labour Party were just one aspect of a complicated political landscape, not least the rise and spread of fascism across Western Europe. In Britain, Oswald Mosley, a former Labour MP, founded the British Union of Fascists, which, although never more than a minority movement, gave an uncomfortably close taste of menace. Amongst the wider movement, Spain seized the popular imagination as symbolic of the struggle between left and right, but while sympathetic groups and individuals swung into action with collections and campaigns, both the Government’s and the Labour leadership’s responses were considered evasive and inadequate.

Marginalised political forces, including the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB), but also other independents including anarchists like art critic Herbert Read, now came to the fore, attracting support for their more decisive stances. This was the background against which Ward, then 13, was taken by his parents, to the 1938 May Day rally in Hyde Park where he saw Emma Goldman speak about the anarchist cause in Spain. From the perspective of his parents, this was less a sign of radicalisation than of their sustained commitment to a notion of democracy. From his perspective, this was important exposure, not necessarily, at this stage, to the nuances of different ideologies, but to a general set of values worth fighting for, not least individual freedom. Less directly, it also planted the idea that politics was not confined to parliamentary activity (and often more sincere outside of that framework) and that ordinary people could have a stake and play their part.

Political activism did not dominate family life. There were other, more pleasurable activities such as concerts at Queen’s Hall in Langham Place where the BBC orchestra played popular classics, regular visits to grandparents still living in East London, seaside holidays in Southend and Clacton. Later, he and elder brother Harvey took long summer cycle rides in the Essex countryside where he encountered, first-hand, the plotlanders he would later champion. Cycling by these examples of ‘domestic bricolage’, the makeshift homes and productive gardens, far removed from the uniformity and constraints of suburban life, the association with freedom was intuitive.[97] Especially when the alternative was a dull classroom.

He found school a dismal affair. Aged 10, he passed a scholarship examination, the forerunner of the 11-plus, to attend Ilford County High School (ICHS), a selective, all-boys grammar, part of a new wave of school building at the turn of the century to prepare children from the aspirant middle (or upper-working) classes for modern careers in industry, administration, and commerce. Ward, however, gained more from his rejection of formal education than his receipt of it. What was he rejecting? Lessons learnt by rote and tested by examinations. Uniforms, structured days, rules, and events, all the training needed to go on into professional jobs. Corporal punishment was used, ICHS was no exception there, but it was not especially rife. He had no tales of Dickensian cruelty to tell of it. He was just bored.

He was never openly rebellious, he just stared out of the window during his lessons, failed to distinguish himself, and left at 15.[98] This seems young to contemporary eyes but in 1939 his grammar school education qualified him for administrative work (as his mother had done some years before). His early jobs on leaving school included being an assistant to a builder illegally erecting Anderson shelters in people’s gardens, and then a construction administrator for West Ham Council. Although formal academic study had not excited strenuous effort from him, it was at this time he conceived a passion for printing and typography, even acquiring his own small treadle-operated printing press, a clam model which one person could operate.

If all this furnishes a fuller social picture of his youth, it offers little by way of an emotional one. Ward was not generally given to personal divulgence but did later recall Arnold as a good-humoured man who rarely lost his temper. Ruby was sharper, ‘more punitive and moralistic’ but hardly tyrannical.[99] Overall Ward’s upbringing might be called comfortable, if a little restrained, middleclass but not ostentatious, socially conscientious but not radical, based on the belief that government should ensure fair chances which individuals should seize for themselves. Naturally, education was valued — both parents had been the beneficiaries of it — as the means of self and social improvement. Ward re-negotiated these values. He would spend a lifetime criticising the social ‘goods’, state education and parliamentary process, that his parents had taken for granted. But he, no less than they, retained respect for respectability and an appreciation for the everyday desires, comforts, and pleasures that many people cherished.[100]

London: Sidney Caulfield

On leaving school, he had hoped first to find a job in printing but when this was not forthcoming, he ‘drifted’ towards construction and administration.[101] Aged 17, Ward became an assistant at Sidney Caulfield’s small architectural practice on Emperor’s Gate, Gloucester Road, London. Caulfield was one of few living links back to William Morris and the Arts and Craft movement. Starting as the pupil of gothic revivalist architect John Loughborough Pearson, he had later moved to study with architect William Richard Lethaby, the first director of the Central School of Art and Crafts, the movement’s educational vision, opened by the LCC in 1896, where he also met artist Eric Gill.[102]

In 1912, Caulfield joined the first wave of architects working on Hampstead Garden Suburb, Henrietta Barnett’s vision of a permanent, socially mixed settlement in which the classes lived together for their mutual improvement. The idea that the healthy community could be created through intelligent design drew directly on the Arts and Craft principle of life as art. Raymond Unwin, the project’s chief planner and former secretary of Morris’ Socialist League, applied this in practice through low-density housing, sensitive to the local environment with gardens to encourage wholesome hobbies and ample spacing to promote social mixing. Caulfield contributed houses on the Meadway, Southway, and Bigwood roads.[103]

By 1941, however, the practice had dwindled to repairs on bomb-damaged factories but his enthusiasm for his old mentor remained undiminished and he would press Lethaby’s Architecture upon his young assistants, urging that here was all they needed to know about their craft.[104] At first, Ward had not been interested in reading it,[105] nor did he much care for his employer’s upper-class, often condescending bearing.[106] In this, Caulfield was not unique; despite moves towards professionalisation, architecture remained a class-ridden occupation. The gentleman architect still expected deference and exercised absolute authority in the building process. If uncomfortable to behold, Caulfield’s autocratic approach had unexpected benefits; it meant a holistic education for his assistant. Ward was sent with messages to contractors, returning with their (often exasperated) replies about the practical realities of working around shortages in materials, labour, and encountering other unforeseen problems, all of which fuelled his understanding of building as an activity with wider social and economic ramifications. Another task, manual plan-tracing, taught him the details and technicalities of the construction process.

Beyond the job, this was also a period of personal and political expansion. Through necessity, Caulfield had divided his London house into flats with his office at the top, living quarters at the bottom and tenants in-between. Mrs Caulfield, who Ward remembered as a more sympathetic character of wider interests than her husband, sat on Refugee Aid committees and through her connections brought in Miron Grindea, a Jewish-Romanian intellectual and literary journalist who fled Paris for England just before the outbreak of war. Grindea was joined by his wife Carola, a celebrated pianist, and daughter Nadia to live in one of the apartments.

Steeped in European artistic culture, Grindea soon took over the editorship of ADAM (Art, Drama, Architecture, and Music), a small journal whose densely packed pages covered a bewilderingly eclectic range of international cultural riches, all compiled according to their editor’s taste from the little flat in Emperor’s Gate. Caulfield, who viewed his tenant as a ‘comic figure’, would not deal with him personally. Ward would be sent down with notes for Grindea who would reply and, from time to time, press a free ADAM into the messenger’s hands. In this way, he encountered a bibliography more extensive and international than many a university reading list.[107]

Although Ward was never one of Grindea’s long-suffering assistants, charged with a relentless battery of tasks (from proofreading, wheedling authors for articles, and above all coping with the editor’s unpredictable temper), ADAM provided a glimpse at the business of independent journalism, not least in the figure Grindea himself, the very embodiment of the autonomous editor. His editorials gave full rein to his idiosyncrasies, combining a montage of styles in astonishing feats of free association. Free to suit himself, he would switch from scholarly erudition to the silliest gossip, from aesthetic appreciation to social critique exactly as it suited him to do so.[108]

Alongside reading ADAM, Ward now began frequenting the Socialist Book Centre on the Essex Road, run by Jon Kimche, and, through here, first came across Freedom Press publications[109] although, given his Labour background it was The Tribune, of which Kimche was the de-facto editor,[110] that interested him more at this time. Once the mouthpiece of the then moribund Socialist League, the paper had morphed into the house-journal for those on the harder left of the Party, including many who would become the chief architects of the Welfare State, the arguments for which were rehearsed in its columns. In autumn 1941, alongside sustained critiques of Churchillian domestic and foreign policy, Ward would also have read an especially optimistic set of articles on modern science and socialism and, following Stalin’s alliance with the Allies, the virtues of planned economy in the Soviet Union.

The idea of progress as a matter of scientifically informed design was naturally attractive to all those working in architecture, like Ward, but perhaps especially to an emerging cohort of students keen to distinguish themselves from the old gentleman amateurs through their professionalism. This helped prompt a ‘rediscovery’ of urban thinkers like Patrick Geddes.[111] A botanist by early training, Geddes saw societies as organic entities gradually evolving over time. Reasoning that development aligned with this natural growth would yield more efficient results, he famously proposed the regional survey as the optimum tool for gaining the necessary local knowledge.[112]

In the years immediately following his death in 1932, interest in Geddes waned (due in part to the scattered nature of his oeuvre) until, six years later, American historian Lewis Mumford recovered his reputation in The Culture of Cities (1938). In Britain, The Culture of Cities was enthusiastically reviewed by WH Holford, then professor of planning at the University of Liverpool in Town Planning Review[113] while Patrick Abercrombie, in his 1938 address to the Geographical Association, of which he was the chair, could state that the importance of Geddes’ biological triad — folk-work-place — to planning education should be taken for granted.[114]

With the likes of Geddes back in favour amongst some of their teachers and restored to course reading lists, a generation of young architects emerged convinced of architecture’s social role, eager for change and frustrated by lingering conservatism in the profession. Some sought inspiration from older British modernists (Max Fry and Wells Coates) and other luminaries like Walter Gropius at Bauhaus, but above all from Le Corbusier, the Swiss-French architect who sought, through design and planning, the total transformation of social life. If these elders remained exciting, the students did not wish merely to replicate them. Taking modernism as a technique rather than an aesthetic, they determined that it should not petrify into a single style.

In taking up the modernist mantle, a small group studying the Association of Architecture School in London launched Focus (1938—1939), a little magazine in keeping with a longer tradition of proselytising architectural periodicals, through which they intended to mark out their own vision. The mood was earnest and urgent. Writing in the first edition, Anthony Cox, future founder of the Architect’s Co-partnership, urged the role of architecture in shaping the social fabric of the whole community (1938). Avoiding fidelity to any one stance, the magazine encompassed a range of modernisms linked by a set of common themes: a concern with materials, technology, and industrial production, the social role of the architect, but above all architecture as a vehicle for social change.

Over four densely packed editions, its columns filled with detailed reports on social projects such as public housing, school building and factories, the last of which were almost entirely ignored by the major periodicals. Materials, from plastic to timber, were assessed for their democratic virtues, and many pages of serious debate were spent on whether the modern architect was to be a prototechnocrat or an advocate between people and industry. Architecture education, they urged, should be conducted via group work and interdisciplinary research. The gentleman architect, instructed in the Beaux-Artes tradition, was to be banished and in his place a new vernacular architecture based on material innovation, responsive to the emergent demands of the new social and economic age. Despite the short print run, Focus gained a readership of 1,500 and had an influence belying the brevity of its duration. [115]

The socialist bent of these ideas was clear and in seeking to establish a firm conceptual basis for their project, Marxism, or the contemporary iterations of it, proved especially attractive, not least for its intellectual satisfactions. Marxist theory synthesised normally discrete areas of life into an all-encompassing framework and offered an analytical language for how everything connected. It was also uncompromising in its commitment to applying science to human progress

(the latter it defined, of course, in its own image). This is not to say that all who drew upon it were Party members or even fellow travellers, but it is to acknowledge its influence across 1930s British intellectual life.[116]

This surge of interest had several roots. In the wake of Labour’s collapse in 1931, there was doubt over whether socialistic measures were possible by existing parliamentary means. The persistence of economic depression throughout the 1930s also convinced many that capitalism was in fatal decline.[117] It also owed much to the CPGB’s Popular Front policy shift (1935) which, by aligning itself with domestic democratic values, did much to seduce a left-leaning liberal intelligentsia towards the cause. Initiatives such as the Left Book Club, brainchild of publishing entrepreneur Victor Gollancz, and, to a less explicit extent, Allen Lane’s Pelican Originals (an imprint of Penguin) put socialist ideas into affordable paperbacks intended for a wide reading public.[118] Titles such as Soviet Communism: A New Civilisation (1937) from the former, or Practical Economics (1937) from the latter, drew unfavourable contrasts between the timidity of British social reforms against the sheer scale and ambition of the great Russian experiment.

For the most part, British Marxism remained an intellectual project, thoroughly filtered through British conditions and experience. Nevertheless, it was a significant thread inspiring a handful of brilliant individuals. In The Social Function of Science (1939), for example, the Cambridge scientist JD Bernal (who was a CPGB member) set out detailed proposals for the application of science at each step of the planning, design and construction process in urban development, assuring his readers that, ‘the totally enclosed, spacious, air conditioned, town is rapidly becoming a practical proposition’.[119] The sheer technicality of these ideas, the promise of social perfection and limitless expansion, seized the imagination of scientists, architects and social reformers alike.[120]

If the Marxians dazzled with their elaborate models, others of a humanist bent, such as the supporters of the Town and Country Planning Association (TCPA), were more circumspect, less certain of the benefits of limitless growth and unchecked technological advance. Whilst welcoming scientific insight, enthusiasm was cautious and careful, generally preferring localised, gradual change that accounted for the whole of human well-being, not just economic productivity. Founded in 1898 by Ebenezer Howard to promote Garden Cities, the TCPA was his response to the pressing problems of land use and social reform at the fin de siecle. Assimilating ideas on land tenure, utopian communities, and organised migration, he proposed to synthesise the best of town and country living in small, self-sustaining cities with fixed populations employed in local industries that generated income for reinvestment back into community life. Following the successful completion of a prototype, Letchworth, momentum waned. Garden suburbs, like Hampstead, had greater success although Howard complained that by not generating independent industry, they missed the main point.[121]

During the interwar years, the Association remained a lonely but persistent voice in the call for Garden Cities until, in 1936, with the appointment of Frederic Osborn as General Secretary, it shrewdly broadened its campaign moving towards a more generalised application of Garden City principles which avoided the expense of founding entirely new settlements. This allowed for greater political traction, and therefore state funding which released them from reliance on private philanthropy. Following the outbreak of war, the Association increased its efforts to influence government policy launching the ‘National Planning Basis’ which called for the creation of a central planning authority, distinct from any existing government department. This authority would be concerned with, amongst other things, the redevelopment of congested urban areas, decentralisation and ensuring the balance of industry throughout the country. Such objectives would be achieved through building new Garden Cities, suburbs, satellite towns, trading estates, or further developing small towns.[122]

Even with their enlarged remit, the TCPA kept faith with its founding principles: sensitive local development, low-density population, balance of residential, rural, and industrial zones, and flourishing community life. This placed it in firm opposition to the high-rise, high-density, ultra-urban, industrial chic enchanting many of architecture’s young turks. Bernal’s ‘totally enclosed, spacious, air conditioned town’ may have been ‘a practical proposition’ but to the TCPA and its membership, it was a horrifying one.

Ward, in forming his ideas on social planning, science, and politics, found two writers important: Lethaby (whose book he finally did get round to reading) and George Orwell. Lethaby, as director of the Central School of Arts and Crafts, had stressed construction and craftsmanship, believing that everyone, architect, carpenter, bricklayer, and furniture maker, should know they were building a house and understand how each component fitted together. He became known for his plain, functional style and stress of rationalism in construction which, he believed, made it more accessible.[123] As he said in an address to the Royal Institute of British Architects annual conference in 1917, ‘train us to practical power, make us great builders and adventurous experimenters, then each of us can supply his own poetry to taste’.[124]

This, along with his preoccupation with materials, interest in new technologies and the construction industry, proved so influential to a generation of modernists emerging at that time that some perceived in him a betrayal of his original Morrisian principles.[125] While he did help shape many of the values of British modernism, he did not share in its rejection of the past. That said, his historical consciousness was not crudely reproductive but reflective: to grasp the character of a place, one had to appreciate its history, the ways in which it embodied and expressed the passage of time and people. Only by understanding this could a truly vernacular architecture emerge.

Although of an older generation, Ward saw a contemporary application for Lethaby’s ideas, not least in the niche found between forward-facing modernism and backwards-looking traditionalism. His was a modest modernism, open but careful in its use of technology, in close step with how real people lived and felt. Lethaby’s character owed much to his route into architecture. Coming from humble origins, he learnt his craft through practice rather than study. His first job as an architect’s clerk had placed him in charge of practical operational questions and liaisons. Like Ward, he had organised schedules of work, fielded concerns, and kept the records. Moving restlessly between the various interested parties, he could never disappear too far into a realm of ideas but had to retain a full factual overview of the process.

Where Lethaby caught Ward’s architectural interests, Orwell spoke to his political ones. He now read Orwell’s journalism extensively, his regular ‘As I Please’ column in The Tribune, and the longer essays which were ‘hard to find anywhere else’ at the time.[126] The late 1930s had been a period of profound personal and political upheaval for Orwell, starting with his ‘epiphany’ in Wigan and culminating with Spain.[127] Although radicalised by these experiences, they left him in a complex relationship to the political left. He was never a Party man (even less so after Spain), nor blindly a ‘movement’ one. From 1940, he wrote extensively on political commitment and English culture, returning constantly to two key ideas. Firstly, that both artistic and political truth stemmed from confronting the world ‘as it really was’. Secondly, that ordinary people, rather than ideologists or intellectuals, by not expecting to impose their will upon the world (and therefore having little to gain from self-deception) tended to do this naturally and sensibly.[128]

Orwell’s other great value to Ward was his writing style. As Crick noted, he was a master of column journalism whose articles became a ‘model for young journalists’ with their ‘mixture of profundity and humour, their range and variety, and for their plain, easy colloquial style’.[129] Orwell considered good style as more than artistically gratifying, it was a political act. ‘All art is propaganda’ he observed in his essay on ‘Charles Dickens’ (1940); even the most apparently trivial of literary ephemera, like ‘Boy’s Weeklies’ (1940), projected ideological messages. Why was it, then, that ‘in England popular imaginative literature is a field that left-wing thought has never begun to enter’?[130] Whether Ward embraced the full Orwellian position (which could be dogmatic on questions of intellectual honesty and national culture[131]) or not at this time, he was drawn to the expression of faith in the ‘common-sense’ of ‘common-people’. This mattered at a time dominated by experts and theories.

Ward did not remain a spectator. On 5 December 1941, he got his first publication with a short letter in The Tribune replying to a previous article ‘Wren’s London Can Be Built’ by Dr TH Hill. Hill was the Deputy Medical Officer for West Ham Council (for whom Ward had worked as a construction clerk) and author of The Health of England (1933), a set of proposals for the reform of public health through a centrally administered voluntary sterilisation programmes for the poor, disabled, and mentally defective as a necessary measure to promote ‘the breeding of genius and creation of an intellectual aristocracy’.