Tobias Higbie

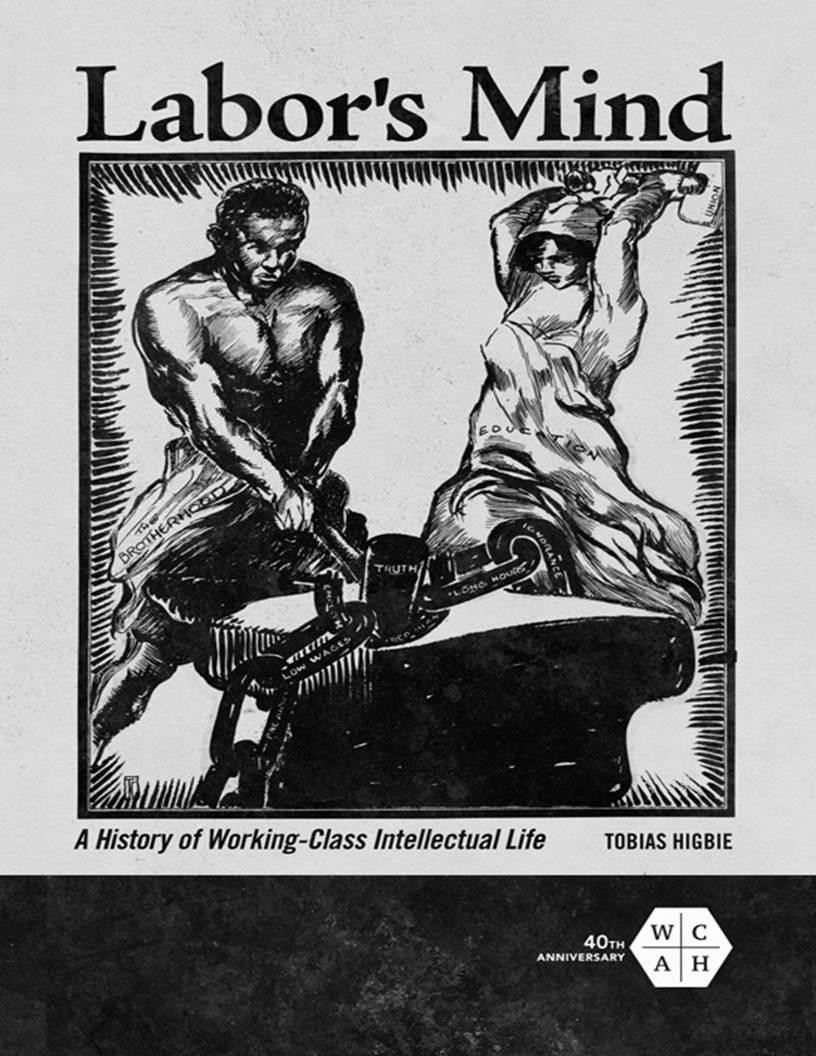

Labor’s Mind

A History of Working-Class Intellectual Life

Part 1: Reading the Marks of Capital

1. “A little avenue to self-mastery”

2. “All sorts of wild, impassioned talk”

Speech, Space, and Labor’s Contentious Networks

Interpreting the End of Free Speech

3. “To see and hear things that have always been there”

Reform, Radicalism, and Workers’ Education

“There is no one road to freedom”

In the Shadow of the University

“There isn’t one working class”

Part 2: Imagining Critical Consciousness

4. Brain Workers in the House of Labor

Life Stories “in regulation style”

Individuality in Collective Terms

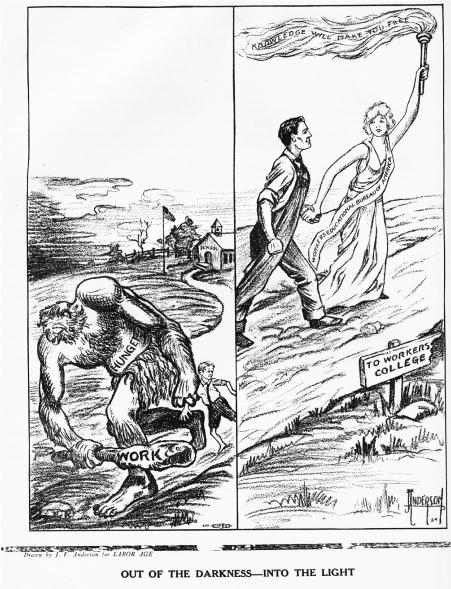

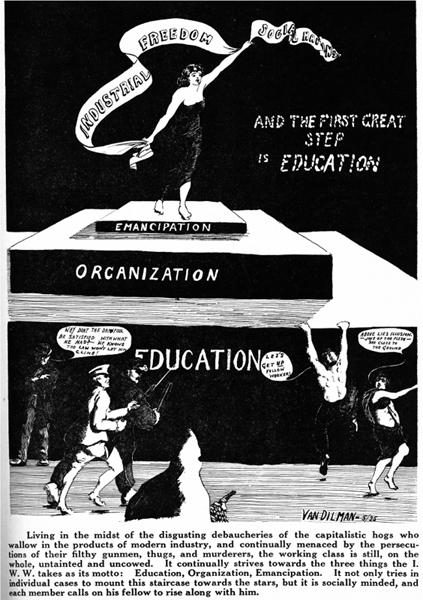

5. Icons of Ignorance and Enlightenment

Social Reproduction and Critical Consciousness

For my children

There are many roads to freedom

Acknowledgments

The city of Chicago is responsible, in many ways, for this book. Early in my career, I had the great fortune to work at the Newberry Library, where the papers of the Dill Pickle Club, Jack Conroy, and the Charles H. Kerr Publishing Company sparked my curiosity about the city’s working-class public sphere—as did the dramatic street protests around the time of the second Gulf War. The result was an exhibition, Outspoken: Chicago’s Free Speech Tradition, co-curated with Peter Alter of the Chicago Historical Society and assisted by Jennifer Koslow (now at Florida State University) and Ginger Shulick Porcella (now at the Tucson Museum of Contemporary Art). Over the years, others at the Newberry have continued to support the project in various ways, especially Jim Grossman (now at the American Historical Association), Paul Gehle, Martha Briggs, Doug Knox, and Liesl Olsen. The late Franklin Rosemont, radical historian, collector, and publisher, deserves credit for keeping this history of Chicago bohemia alive, maintaining the Kerr Publishing Company, and preserving a rich collection of radical pamphlets and ephemera.

My own engagement with the contemporary labor movement has been another touchstone for this project. The decade-long campaign to win collective bargaining rights for graduate employees at the University of Illinois was my first introduction to social movement education and the beginning of an ongoing conversation about practical democracy among comrades who are now old friends. Later I worked at the University of Illinois Labor Education Program, where I encountered remarkable worker-students in the United Steelworkers of America summer institutes, the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers apprenticeship school, and in other settings. I especially want to thank my Illinois colleagues Joe Berry, Helena Worthen, Ed Hertenstein, and Bob Bruno. Stories I heard from two veterans of the labor movement didn’t make it into the book, but on reflection they inspired much of my research. The late Les Orear, longtime champion of the Illinois Labor History Society, recounted his experiences as a student at the University of Wisconsin, and as an organizer of packinghouse workers during the Great Depression. Ed Sadlowski, former head of the United Steelworkers in Chicago, told me about his youthful love of story magazines and about a worker in the U.S. Steel plant who introduced him to the work of James T. Farrell. Observing firsthand the vibrant program of the UCLA Labor Center and the Institute for Research on Labor and Employment has been another inspiration for this project, and I especially want to thank Kent Wong, Gaspar Rivera Salgado, Janna Shadduck-Hernandez, and Victor Narro for the amazing work they do to keep alive the best traditions of the labor movement.

No scholarly work leaps fully formed from the head of its author. We share drafts and comments and encourage and redirect one another. This is especially so with long-germinating projects like this one. Years after I moved away from Chicago, I was honored to spend a year back at the Newberry as the Lloyd Lewis Fellow in American History. The outstanding collections enriched my story, and I benefited from the support of outstanding librarians and a community of scholars with their noses to the grindstone. The participants in the Newberry’s Labor History Seminar provided critical encouragement, especially Leon Fink, Erik Gellman, James Schmidt, Rosemary Feurer, Elliott Gorn, and many others. Among my class of fellows, I especially want to thank Cristina Stanciu, Cathleen Cahill, and Mary Campbell for their detailed comments. Beyond the Newberry, many others read, commented, and urged me to “finish the damn thing,” including Elizabeth Faue, Scott Nelson, Kathryn Oberdeck, Cindy Hahamovitch, Nelson Lichtenstein, Adam Nelson, John Rudolph, Tony Michels, Caroline Merithew, Tim Lacy, Steve Meyer, Ron Schatz, and Emily LaBarbera Twarog. My colleagues in Los Angeles, including John Laslett, Jan Reiff, Karen Brodkin, Jennifer Luff, Kelly Lytle-Hernandez, Vinay Lal, Ellen DuBois, Nile Green, Michael Meranze, and Ruth Milkman have provided invaluable support and feedback on this project. Finally, I want to thank Jim and Jenny Barrett for their support, friendship, and good humor for over twenty-five years. Jim’s accessible scholarship and his dedication to his students continue to inspire me. I also want to thank two anonymous readers from the University of Illinois Press for invaluable feedback drafts of the manuscript.

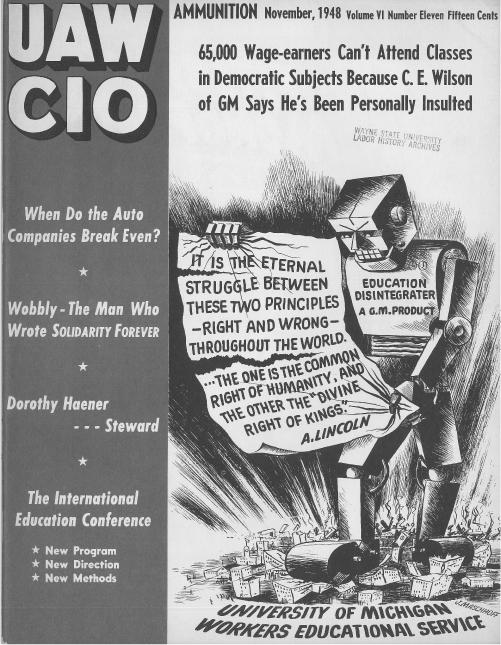

This project has been generously supported by a number of institutions, including the Newberry Library, the University of Illinois Institute for Labor and Industrial Relations, the Iowa State Historical Society, the University of California Labor and Employment Research Fund, the UCLA Institute for Research on Labor and Employment, UCLA History Department, UCLA Academic Senate, and UCLA Center for Digital Humanities. I also want to thank the many archives I visited and their dedicated staff members, including the Walter P. Reuther Library at Wayne State University; the Southern California Library; the Tamiment Library; the Wisconsin State Historical Society; the Labor Archives and Research Center at San Francisco State University; and university archives at the University of Wisconsin, the University of Illinois, the University of Michigan, and the University of California at Berkeley and Los Angeles. Without the long-term investment in these publicly accessible collections, no work of history would be possible. Portions of chapters 1 and 2 originally appeared as “Unschooled but Not Uneducated: Print, Public Speaking, and the Networks of Informal Working-Class Education, 1900–1940,” in Adam R. Nelson and John L. Rudolph, eds., Education and the Culture of Print in Modern America (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2010). Readers of the journal Labor will recognize chapter 5 as a revised version of “Why Do Robots Rebel? The Labor History of a Cultural Icon,” Labor: Studies in Working Class History of the Americas 10 (Spring 2013). I thank the editors and publishers of these pieces for their permission to build on my earlier works. I also want to thank the small army of editors and library and production staff that helped assemble the final product. At the Newberry, John Powell helped me with images. At the University of Illinois Press, James Engelhardt, Laurie Matheson, and the production staff helped me get over the finish line. Pauline Lewis from UCLA provided invaluable research and editing support for the final product.

When a project is so long in development, births, deaths, and everything in between are the unseen companions of an author’s words. My parents, Peter and Frances Higbie, both passed away in the years this book germinated, as did my mother-in-law, Sharon Gaffney. We miss them every day. My children were born near the beginning of this project and now are beginning their run as teenagers. They would like me to write something of interest to them now, preferably fiction. We will see about that. Through it all, my lifelong companion, Loretta Gaffney, has cheered me on to the finish line. Together, we are spanning time.

Introduction

In the depths of the Great Depression, a youthful Ralph Ellison had an un-expected encounter with intelligence and high culture that stuck with him for decades. The recent college graduate and future novelist was supporting his bud-ding literary career on the staff of the New York Writers Project and dabbling in progressive politics. Canvassing Harlem tenement buildings with a petition for some long-forgotten cause, Ellison knocked on each apartment door asking for signatures. As he stood at the door of a basement apartment, he heard the voices of men arguing in accents he thought marked them as unschooled African American migrants from the rural South. Behind the door, “a mystery was unfolding,” Ellison remembered, “a mystery so incongruous, outrageous, and surreal that it struck me as a threat to my sense of rational order.” The men, cursing and shouting, “were locked in verbal combat over which of two celebrated Metropolitan Opera divas was the superior soprano!”[1]

Gathering his courage, Ellison knocked and then entered a scene fit for a proletarian novel. “In a small, rank-smelling, lamp-lit room, four huge black men sat sprawled around a circular dining-room table, looking toward me with undisguised hostility,” he wrote. “The sooty-chimneyed lamp glowed in the center of the bare oak table, casting its yellow light upon four water tumblers and a half-empty pint of whiskey.” Leaning against the fireplace were four huge shovels, indicating that the men relaxing at the table had spent their day in one of the nation’s worst-paid occupations. One of the men stood and confronted Ellison with words that might have been on the lips of any working person whose home was suddenly breached by a representative of a higher class: “What the hell can we do for you?”

Ellison introduced himself and presented his petition. The men dismissed it as pointless but signed anyway as a token of support for their young visitor, a fellow black man who had graduated from college and aspired to a career as a writer. Still baffled by what he had heard, Ellison finally asked, “Where on earth did you gentlemen learn so much about grand opera?” After a round of laughter one man answered, “Hell, son, we learned it down at the Met, that’s where. … Strip us fellows down and give us some costumes and we make about the finest damn bunch of Egyptians you ever seen. Hell, we been down there wearing leopard skins and carrying spears or waving things like palm leafs and ostrich-tail fans for years!”

The laughter that followed dissolved the tension lingering between Ellison and the men, but the social distance remained palpable. In the historical record of industrial America, working people appear predominantly as statistics, frequently as victims, and sometimes as heroes. But working people, especially African American laborers, very rarely appear as aficionados of high culture. Even after forty years, the event was vivid in Ellison’s imagination and freighted with meaning. He called it a “hilarious American joke that centered on the incongruities of race, economic status, and culture.” The artist, Ellison concluded, must perform with the knowledge that even among these supposedly low audiences, there were those capable of critical understanding. Despite their regional dialect and low station, the coal heavers were not simple rural folk: backward relics out of place in modern New York. Ellison concluded they were “products of both past and present; were both coal heavers and Met extras; were both workingmen and opera buffs.”[2] They were fully human and fully modern.

The surprise and sense of cultural dislocation Ralph Ellison felt in that basement apartment reflected the pervasive assumption that workers and intellectuals were not only very different types of people, but also unbridgeable social categories. The champions of proletarian revolution asserted this truism as often as college professors and capitalist newspaper editors. The school of hard knocks was the eternal rival to every university and college. Ironically then, stories of encounters between surprised intellectuals and working people who somehow knew more than was expected of them were common in American letters. The elite New York writer Hutchins Hapgood went to turn-of-the-century Chicago to look for a “human document” of the city’s industrial conditions to match those depicted in his study of New York’s Jewish Lower East Side, The Spirit of the Ghetto, and in his portrait of a criminal life, The Autobiography of a Thief. Instead, he found the immigrant labor leader Anton Johannsen, who engaged him in a conversation about Tolstoy, thereby demonstrating his “intellectual vigor, his free, anarchistic habit of mind, and the rough, sweet health of his personality.”[3] The two men became friends, and Hapgood was drawn into Johannsen’s social scene to a degree he had avoided in his previous ethnographic excursions. “A thousand times,” Hapgood wrote of his time among Johannsen and his proletarian friends, “I felt myself to be in the midst of a kind of renaissance of labor.”[4]

University of Wisconsin economist Don Lescohier traveled the length of the Great Plains during the summer harvest seasons of 1919, 1920, and 1921, documenting the lives of farmworkers. In one migrant camp he met his intellectual match in the person of an unschooled Irish immigrant named Doyle, who was, Lescohier wrote in his field notes, “one of the brainiest and thoroughly read” workers he had ever met. “I drew him, or rather he drew me, into an economic discussion. This hobo, this bum, this chap who had never been inside of a school … knew the classical economists well and quoted readily from Ricardo and Adam Smith.” Doyle identified himself as both a Bolshevik and member of the militant Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and impressed Lescohier with his thorough knowledge of current events. He couldn’t agree with Doyle’s radical politics, but Lescohier respected his intellect and his commitment to social justice. “The ‘Red’ is on a higher social level than the unorganized hobo,” he concluded.[5]

Another economist, Broadus Mitchell of Johns Hopkins University, might have expected to meet intelligent wage earners when he agreed to teach at the Summer School for Women Workers at Bryn Mawr College in the early 1920s. He and the school’s organizer, Hilda Smith, were surprised, however, when students—young women from recently unionized industries—went on strike to demand the African American housecleaning staff be given better living conditions. Among those students may have been Rose Pesotta, who attended the school in 1922. A Ukrainian immigrant, garment worker, and anarchist, she would go on to a long career in the labor movement. Mitchell later said of Pesotta, “Talk with her a few minutes as casually as you may, and strength is poured into you, as when a depleted battery is connected to a generator.”[6] Although the gender conventions of the 1940s dictated that Mitchell emphasize Pesotta’s emotional intelligence, she knew her Tolstoy as well as or better than many of her male counterparts in the labor movement.

I had my own encounter of this kind in a classroom full of steelworkers back in the summer of 2005. A newly hired assistant professor, I was teaching a class of rank-and-file leaders from steel mills and tire factories in Illinois. While leading my class through an infamous passage of Frederick Taylor’s 1911 book, The Principles of Scientific Management, I had one of those “aha” moments, a sudden cognitive dissonance that bumped my thinking onto a new, more productive track. Taylor, a factory manager turned management consultant, detailed how he reorganized the work of moving heavy iron “pigs,” or ingots, at an iron foundry. His first task was to choose a worker who was eager and compliant, an immigrant laborer he identified only as “Schmidt.” Taylor then micromanaged Schmidt’s every motion and emotion. He told Schmidt when to work, how to work, and when to rest. Evidently, Schmidt thought Taylor’s orders were bizarre, but he considered himself a “first class worker” and did what he was told. By following Taylor’s careful plan, Schmidt was able to move forty-seven tons of iron in a day instead of the mere twelve and a half tons he had moved daily before Taylor’s intervention. As a reward for this improved efficiency, Taylor increased Schmidt’s pay from $1.15 to $1.85 per day.

Having taught this text to undergraduate students several times, I was prepared for my students to identify with Taylor’s drive for efficiency and to accept Schmidt’s lot uncritically. Perhaps they would object to Taylor’s insulting treatment of Schmidt or possibly understand that Schmidt’s pride and desire to be considered a “first class worker” made him particularly suitable for Taylor’s experiment. I assumed it would take me some time to bring the students to an understanding of the economic inequalities at the heart of Taylor’s relationship with Schmidt. Instead, a steelworker in the back row raised his hand and explained with surprising precision that Taylor had extracted a productivity gain of over 250 percent in return for a pay increase of about 60 percent. While I stood mute, the other students nodded in agreement and the rest of my lesson plan went out the window. I listened in as the conversation turned to their own negotiations with foremen on the shop floor and with managers at the bargaining table. It was a humbling lesson for a new professor: my students knew much more than I had assumed. In their own way, they were echoing the coal heaver’s reproachful question to Ralph Ellison: “What the hell can we do for you?” I began to wonder how often—and with what results—similar interactions had taken place in the past. What I found changed the way I think about the history of industrial society. It also changed how I think about myself as a scholar and a worker in the knowledge factory.

Like a broken record, American intellectuals have been discovering the wisdom of working people for more than a century. This leitmotif of our industrial culture does some interesting work, marking separate spheres of mind as unbridgeable, but somehow beside the point. Intellectuals and workers are two very different types, we are reminded, but the homespun intelligence of the unschooled works to balance the cultural asymmetry. The two sides can go their separate ways in peace. Labor’s Mind flips this script, finding the imagined divide between workers and intellectuals both tragically real and frequently crossed. At the center of the story are working people with little formal schooling who deployed ideas with vigor and creativity. In this social history of reading, writing, and teaching we can glimpse the conditions that make democratic intellectual life possible, and why those conditions have been so difficult to obtain.

When Ellison encountered his operatic coal heavers, American society was on the cusp of a new way of thinking about literacy, education, and the intellectual capacities of working people. At the turn of the twentieth century, almost nine in ten Americans could read and write, according to the U.S. Census. Of course, literacy was not spread evenly across the nation. Literacy rates among foreign-born workers in the early twentieth century ranged from a low of 48 percent among Portuguese to a high of 99 percent among Swedes. Ninety-six percent of Irish immigrants could read. In 1900 just a little over half of the black population could read and write—the legacy of slavery, segregated schooling, and poverty. By World War II, however, nearly 90 percent of African Americans were literate. These changes reflect a dramatic expansion of public schooling between 1900 and 1940, including a twelvefold increase in high school attendance. Even so, at the start of World War II nearly 60 percent of Americans age twenty-five years or older had an eighth-grade education or less. This percentage was even greater among foreign-born whites and African Americans of this age, with roughly 80 percent of those populations having eight years or less of formal schooling. Only 14 percent of the working-age population had completed four years of high school. For working people who came of age between 1900 and 1940, higher education was a rare privilege indeed. It was typical for working-class kids to leave school by age fifteen, and even as high school attendance rates climbed steadily in the 1920s and 1930s, many of these students mixed school and work as family finances dictated. Higher education lay just beyond the realm of possibility for many smart, ambitious working people, who today would attend college without a second thought.[7]

Massive government investment in education after World War II reversed these figures within three decades. By 1970 more than half of Americans twenty-five and older had finished high school, and another 20 percent had at least some college experience. The portion with an eighth-grade education or less was under one-third. In the course of one lifetime, formal secondary education became a normal experience for young people in the United States. By the turn of the twenty-first century, the United States had become a country of brain workers—at least by the standards of the previous century. Fewer than one in ten Americans age twenty-five or older had no high school experience in 2000. More than 80 percent had completed four years of high school, and more than half had some college experience.[8] Radically transforming the relationship between class and formal knowledge, the expansion of public education democratized many aspects of American culture and enabled new forms of capitalism. As a professor in a public university founded in 1919, I owe my livelihood to this historic transformation.

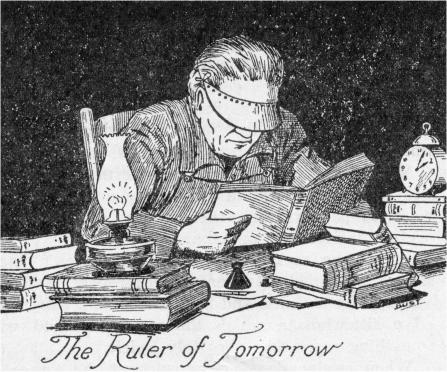

In a curious twist of history, the celebration of practical experience and the reach of book learning increased in tandem over the course of the early twentieth century. Some of the best-known figures in American history lacked formal schooling. Honest Abe Lincoln, rail splitter and future U.S. president, famously educated himself by reading by firelight after long days of physical labor on his frontier farm. The abolitionist Frederick Douglass, first introduced to reading by the wife of his slave master, secretly honed his skills before fleeing the South. The steel magnate Andrew Carnegie went to work in a mill at the age of thirteen, long before he endowed thousands of local public libraries. Even Henry Ford and Thomas Edison had only the bare minimum of formal education before they launched their legendary careers. Like these famous businessmen, prominent leaders of the labor movement were proudly self-educated. Terence V. Powderly, leader of the largest labor organization of the 1880s, the Knights of Labor, was the eleventh of twelve children born into a poor Irish Catholic family in 1849. He went to work at age thirteen after a few years of unmemorable schooling in the basement of a church. Samuel Gompers, the long-serving leader of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) from 1882 until his death in 1924, went to work at age ten with only a few years of formal education.[9]

For every life lifted into fame, thousands more carried on striving in relative anonymity. Iconic stories of self-improvement encouraged them, but a nagging question faced those who failed to live up to the promise of American meritocracy. Were those who failed simply not smart enough? One individual’s failure to live up to the American story of the self-made man was tragic but personal; however, an entire class or race failing to advance posed different questions. Progressives pointed to vast disparities of wealth as the cause of America’s troubles and celebrated the contributions of immigrants to a “Trans-National America,” as the writer Randolph Bourne did in 1916. Less charitable voices were louder and often more popular. A 1922 best seller by a Harvard-trained historian, for instance, insisted that immigrant workers were racially “unadaptable, inferior, and degenerate elements” who would eventually drag “civilized society” down to their own level.[10] No less a champion of the common man than Henry Ford thought much the same of his factory workers, whether immigrant or not. “Many want to earn a living without thinking,” he wrote in 1926, “and for these men a task which demands no brains is a boon.” In a similar vein, Frederick Taylor summarized the method of so-called scientific management as a process of so minutely specifying work tasks that “it would be possible to train an intelligent gorilla” to be more efficient than women and men.[11]

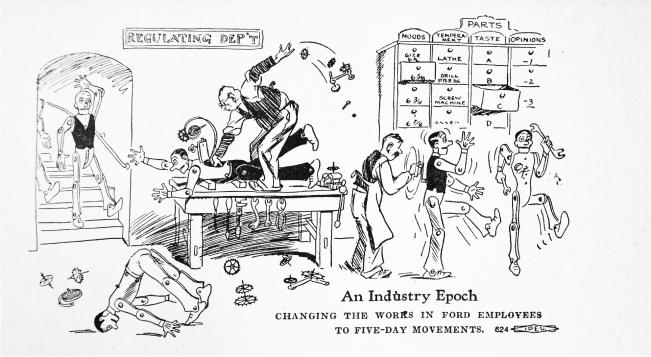

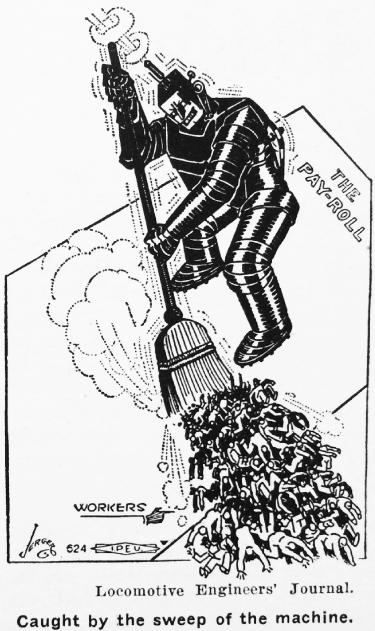

Managers and conservative ideologues were not alone in believing that factory work made people less than fully human. Working-class characters in literature and film often found themselves subsumed, or consumed, by the machinery of production. As Upton Sinclair said of the working-class antihero of his 1937 novel, The Flivver King: A Story of Ford-America, “So Abner Shutt became a cog in a machine which had been conceived in the brain of Henry Ford … and this was something which suited Abner perfectly. His powers of thinking were limited, and those he possessed had never been trained.”[12] In the film Modern Times (1936), Charlie Chaplin’s Little Tramp character is driven to distraction by the repetitive tasks of the assembly line and dragged into the gears of the factory. Unlike so many real-life workers who lost life and limb to industrial accidents, the machine spits Chaplin out physically whole but mentally deranged. The insubordination and uncontrolled libido that manifest after his trip inside the machine drew laughs in part because it lampooned common assumptions about mass production workers. Horace Kallen, a defender of immigrant culture and confidant of progressive labor leaders, blamed the assembly line for the “strange psychoses of industrial society, the crazes, tempers, [and] unrests which its critics dwell on and assign to decay.” The reason was a kind of human mechanization. “The machine-tender is integrated with the machine,” Kallen wrote in 1925. “His operations are part and parcel of the automatized activities of the machine process.”[13] With such words written by an ally of the labor movement, it is hardly surprising that many in the middle and upper classes doubted working people’s fitness for citizenship in a modern society. White or black, immigrant or native born, if the assembly line turned workers into virtual machines, or working people could be replaced with “intelligent gorillas,” then they would remain permanent outsiders to the body politic.

Taylor’s condescending assessment of workers’ mental capacities notwithstanding, the first decades of the twentieth century witnessed a worldwide fascination with the question “What’s on the worker’s mind?” Like the book of that title by management consultant Whiting Williams, much of this interest stemmed from the actions of workers, especially the wave of mass strikes by immigrant factory workers that rose to a crescendo between 1916 and 1922. American observers were mystified by seemingly spontaneous and leaderless strikes of textile and garment workers in the East, meatpackers and steelworkers in the Midwest, and even among the transients who took seasonal railroad, timber, and agricultural jobs in the farflung West. Europe experienced its own version of this strike wave, culminating in the mass desertion of the Russian army that brought the downfall of the tsar in 1917. The Czech playwright Karel Čapek memorialized the phenomenon in his 1920 play, R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots), imagining workers as a class of automatons who rise up and slaughter their human masters.[14]

This was also an era in which so-called brain work proliferated as bureaucracies in business, education, government, and civil society generated a greater demand for those who could write, figure, and manage flows of information and people. Understanding and managing working-class rebellion became the full-time job of a growing class of researchers, journalists, and organizers. In a variety of ways that seem muddled and contradictory with the wisdom of history, these brain workers struggled to reconcile the era’s Tayloristic cultural logic with ample evidence that working-class people had minds of their own. One influential line of interpretation asserted that radical intellectuals were the guiding hand behind the proletarian upsurge. How else to explain the spectacle of untutored laborers quoting Marx and Engels? This was not far from Lenin’s assertion that workers were not, on the whole, ready for communism and would need to be led by the vanguard party. Both perspectives accepted Taylor’s basic framework: modern efficiency demanded a clear divide between brain work and hand work. Mainstream progressives in the United States rejected these extremes but also understood working-class and immigrant lifeways to be bordering on pathological. Education would lift workers up and discipline their minds in ways that would support democratic participation. Theirs was a modified Taylorism in which workers became raw material passing through a process planned and directed by elites. A smaller group of progressives and radicals, who appear frequently in this book, aimed to cultivate the capacity of working people to develop their own minds and organize their own educational, industrial, and political agendas.

The relationship between this latter group of activists and the working class at large was a subject of contentious debate reflecting different views about the authenticity of working-class radicalism. Commentary on the labor movement, whether scholarly or popular, frequently aimed to distinguish organic expressions of working-class sentiment from those derived from some external influence. Selig Perlman, a former revolutionary who fled Russia and became a professor at the University of Wisconsin, had little patience for radical intellectuals who hoped to steer workers to the left. They were, he wrote, typically unable “to withstand an onrush of overpowering social mysticism” because they imagined the working class as “a ‘mass’ driven by a ‘force’ toward a glorious ‘ultimate social goal.’” In contrast, Perlman celebrated trade unionists associated with the AFL as the “organic groups” among the workers. Their defining intellectual feature was their practicality: they always “keep in sight the concrete individual, with his very tangible individual interests and aspirations,” even as they “enforce, upon their individual members, collectively framed rules” in the form of trade standards.[15]

Despite Perlman’s dismissive opinion of the radical left, they, too, identified a split between “organic” working-class thought and that of formally trained intellectuals and sought to ground their work in the particular grievances of individual workers. Radicals often found evidence of class sentiment in the most mundane of workers’ experiences and sought to cultivate it. As a manual for “worker correspondents” to the radical press put it, the average worker “is not inarticulate because of lack of words, but because he has been taught by capitalism to look upon the thousand and one tyrannies, inconveniences and hardships inflicted on the workers as of little importance.” These everyday indignities—workplace accidents, layoffs, abusive foremen—mattered to individual workers because they structured life’s possibilities. Worker correspondents would write about these grievances and connect them to a broader pattern. While this advice came from the communist editor William Dunne, himself the child of immigrant workers, who was forced to drop out of college for financial reasons, the sentiment was shared by many labor partisans across the ideological spectrum. Along with the Marxist left, religious leaders known as labor priests, immigrant journalists, and even progressive settlement house workers shared to some degree the desire to cultivate working-class voices. They sought out and developed “organic intellectuals,” to use a phrase that was not known at the time.[16]

In the following chapters, I explore the social world of working-class reading and learning alongside debates in text and image over workers’ intellectual capacities. Part I probes a set of paradoxes at the heart of working-class intellectual life in the United States during the early twentieth century. First, although limited in their access to formal schooling beyond the eighth grade, the vast majority of urban working people could read, write, and count. In fact, one could hardly navigate daily life in American cities without basic literacy, much less thrive in the modernizing economy. Noisy and cluttered streets were awash in words and numbers: addresses, price tags, paychecks, discarded newspapers, and advertisements. Decoding this stream of information was key to finding a job and a place to live, noticing whether you had been short-changed by a merchant or employer, avoiding violence at the hands of a rival community, or momentarily escaping everyday boredom through the pages of a novel. Useful and necessary for survival in the industrial city, reading also opened for working-class readers social worlds beyond the everyday. The excitement generated by encountering these new worlds drove many working people on to more reading and more questions. By the early twentieth century, the curious could find what they were looking for in well-stocked public libraries, programs of public lectures, and in the pages of newspapers written in many languages.

I refer to this process as “self-education” and to the participants as “self-taught,” but it is important to use these terms with some caution. Although most of their learning took place outside of traditional schools, the so-called self-taught were not solitary hermits.[17] They were deeply entwined in networks of other learners, communities, organizational cultures, and markets for books, newspapers, and pamphlets. Text—and the ideas it transmitted—created, strengthened, and in some cases splintered communities. The drive of coal miners, garment workers, and housemaids toward self-education signaled both their desire for the intellectual fruits of modernity and the great economic and cultural changes that would be required to fulfill those desires. Pamphlets, newspapers, study groups, and street speakers amplified and circulated a vast and contentious dialogue about inequality to audiences that were fragmented by race, sex, skill, nationality, and location. The ethical traditions of progressive Christianity and Judaism motivated and shaped the ideas of many who were active in popular education; however, questions of inequality here on earth were paramount.[18] Many others rejected religious traditions in favor of various forms of radicalism. Struggling trade unions, radical political groups, advocates of equality for immigrants, women, and African Americans—the labor movement broadly defined—were key components of this working-class public sphere.

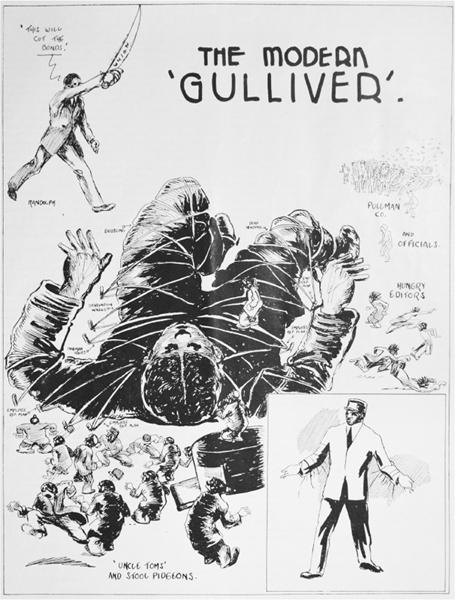

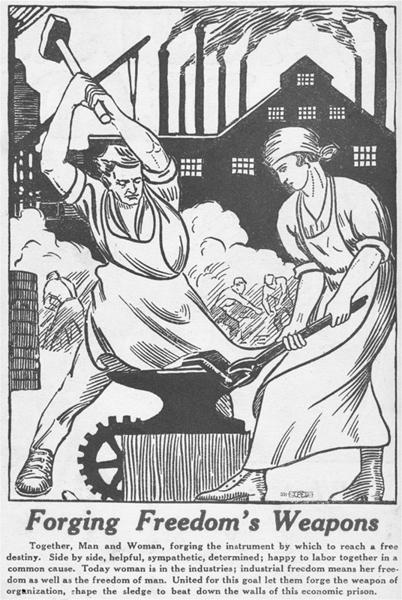

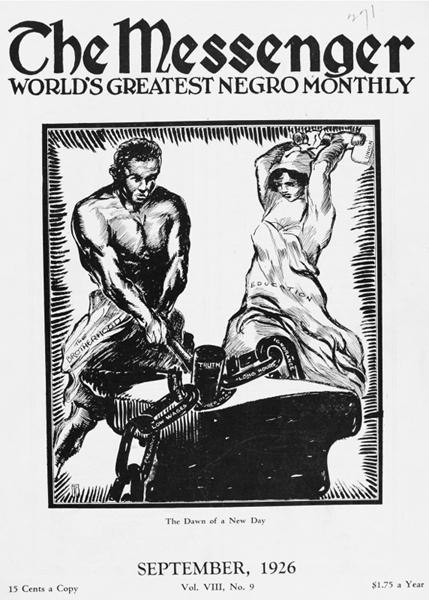

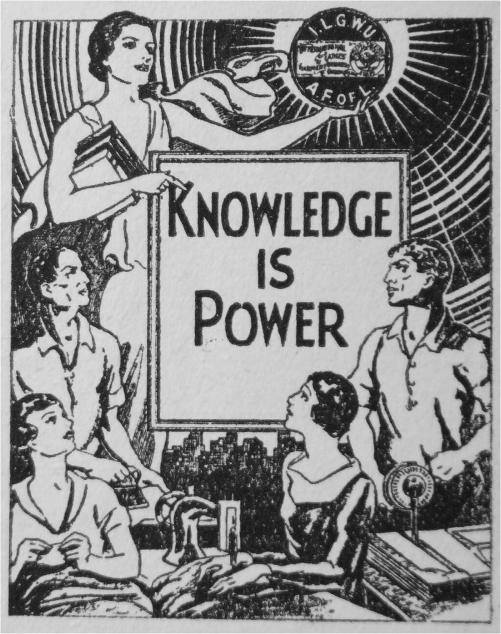

As I sat in libraries and archives, paging through the newspapers, magazines, and books that circulated through workers’ reading groups, union halls, and open forums, I was struck by the pervasive use of drawings, cartoons, and, to a lesser extent, photography. Even crude mimeographed pamphlets often include a cartoon or an illustrated masthead. When you view hundreds of these images, you begin to see patterns, motifs, and echoes suggesting ideas about knowledge, power, and social order. Along with these pictures, texts also create images in our minds, and together these both reflect and structure our expectations about how the world operates and our relationships with others—what the philosopher Charles Taylor identifies as a “social imaginary.”[19] The chapters in part II explore this social imaginary through the politics of movement storytelling and the iconography of workers’ education. Stories and images structured Americans’ expectations about workers and their intellectual horizons. What did intelligence look like, and could people readily imagine working people of all kinds as having intelligence, however they might understand the term? Another key question for labor and radical movements was exactly how individuals became committed to working for fundamental social change. Conversion stories in the labor and radical movements secularized the tradition of inspirational storytelling rooted in American Christianity, but movement storytellers also confronted a changing cultural terrain in the 1920s. Influenced by social science and literary modernism, social movement storytellers between the world wars consistently emphasized lived experience over book learning. In the process, they “modernized” the very concept of working-class experience as the arbiter of authentic understanding and identity.[20]

The educational landscape of the United States has changed radically over the past sixty years as formal education became commonplace, even for those of modest means. The way we talk about intellectuals and ordinary people, however, is much the same as it was in the early twentieth century. For many in the media, the 2016 presidential election ratified the divide between the cool and distant intellectuals and technocrats associated with Hillary Clinton and the ordinary folks who voted on “gut instinct” for the “blue-collar billionaire,” Donald Trump. Drawing on hollowed-out social categories inherited from our industrial past, these assertions barely withstand a gentle encounter with reality. Still, they echo through mass and social media. Today relatively few Americans work in the kinds of industrial settings that were common in the early twentieth century, and an unprecedented proportion of wage earners have college degrees. There are more than twice as many graduate teaching assistants as coal miners working today in the United States. About 2.5 million registered nurses care for sick and injured in hospitals and clinics, while only about 160,000 workers staff the much-diminished automobile assembly lines.[21] Despite these changes, the idea that workers and thinkers are distinct kinds of people with opposing interests remains potent in popular culture and politics. Returning to the moments in the early twentieth century when activists, educators, and artists struggled to balance the competing claims of laboring status and formal education, I hope this book will help readers to understand the past and to embrace more productive ways of thinking about social movements and popular education in the present.

Part 1: Reading the Marks of Capital

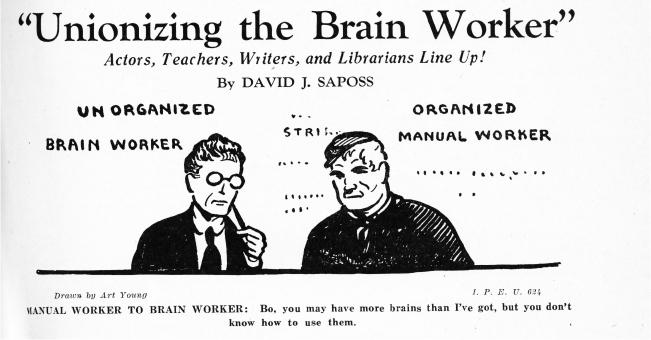

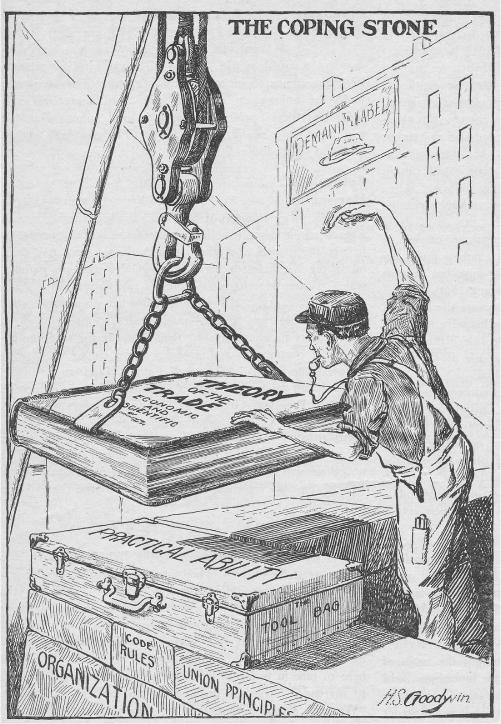

In the closing months of 1922, cartoonist Art Young lampooned the intellectual class with his typically sharp visual wit. The veteran socialist depicted a scrawny, bespectacled “UN ORGANIZED BRAIN WORKER” facing off with a beefy “ORGANIZED MANUAL WORKER.” The word “STRIKE” floated behind them, invoking the unprecedented labor strife of the early 1920s. “Bo, you may have more brains than I’ve got,” the laborer tells the intellectual, but you don’t know how to use them.”

The image carries two key ideas that remain with us today. First, it presents education as the great divide. The campus and the factory are distinct; professors and the people are two opposing camps in modern society. Second, for all of their mental acuity, intellectuals are impractical, ineffective, and weak. Their knowledge has been gathered in isolation and is of little use to ordinary folk. In contrast, laborers have learned their most important lessons in the “school of hard knocks” and possess a clarity of purpose driven by bitter experience. Young’s cartoon was the visual equivalent of a saying attributed to the radical trade unionist Big Bill Haywood: “I don’t know much about Marx’s Capital, but I’ve got the marks of capital all over me.”[22]

An ironic commentary on the presumptions of elite knowledge, Young’s image also asserted the cultural value of working-class masculinity and embodied knowledge. But there was something more. In its time, the cartoon face-off portrayed the very real interactions between college-educated and unschooled intellectuals. In the decades before World War II, exchanges like these were common in the vibrant world of urban open forums, settlement houses, and labor colleges designed to train working-class activists. More than a few American social scientists faced critiques like this from workers they studied and whose lives they translated into academic articles, government reports, and sometimes popular books. Real or imagined, interactions like the one portrayed in Young’s cartoon sparked debates about the comparative value of experience versus book learning, the line between education and propagandizing, and the nature of authentic social movement leadership.

The first three chapters of Labor’s Mind explore the social and institutional contexts in which formally trained intellectuals encountered their working-class counterparts. Chapter 1 interrogates the notion of “self-education” through an ethnography of working-class knowledge gained through experience and reading. Despite the pervasive invocation of the “school of hard knocks” as the origin of practical knowledge, I show how many working people found their way to reading and drew inspiration from the printed word. Most working people in the United States were literate, and after the turn of the twentieth century the market for inexpensive texts blossomed. Political radicals and progressives took advantage of new printing technologies to market magazines and books aimed at self-educating workers and farmers in English and a variety of immigrant languages. The socialist Appeal to Reason and the Little Blue Books from the Haldeman-Julius Publishing Company were just two examples of the profitable strategy of embedding marketing within social movement networks.

Like Art Young’s unorganized brain worker, professors who encountered working-class intellectuals often found them surprisingly well informed, if sometimes dogmatic in their politics. The radical unionist and future Communist Party leader William Z. Foster was mainly self-educated after a few years of primary school. When he lectured the students of labor economist John R. Commons at the University of Wisconsin, however, he gave what the eminent professor considered “the most scholarly account I have heard of the evolution of Communist doctrine.” As historian Timothy Lacy recounts, the Great Books advocate Mortimer Adler led a series of classes at the People’s Institute at New York’s Cooper Union, where he found his working-class students to be receptive to the works of Shakespeare, Descartes, and other classics. Some were “as good as my Columbia groups,” Adler reported, although they were also “intellectually untrained” and “full of prejudices and ‘ideas’.”[23] The line between “intellectual” and “worker” became increasingly blurry in these contexts and ever more in need of policing.

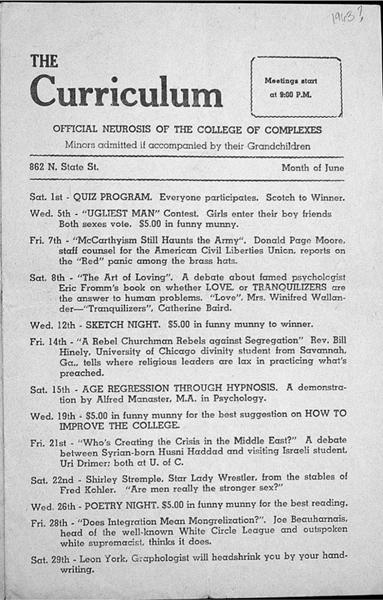

Just as readers were never in isolation, authors’ words rarely stayed on the printed page. On street corners, in public parks, and in lecture halls in most North American cities, speakers repeated and amplified the printed word. Radicals of every stripe joined preachers, transient salesmen, and assorted entertainers in these raucous public venues. If speakers were not always selling revolution, they nevertheless learned to modulate their pitch to appeal to their overwhelmingly working-class audiences. In this way, the concerns, doubts, and ambitions of workers indelibly stamped the urban public sphere. Chapter 2 explores this world of urban open forums, especially those of the Midwestern industrial metropolis of Chicago. Situated at the crossroads of the nation’s vast rail network, Chicago was home to a militant working-class movement eager to hear (and sometime pay for) the words of visiting radicals. Supplementing the outdoor forums, cultural entrepreneurs launched a variety of venues, including the famed Dill Pickle Club, the brainchild of Jack Jones and Ben Reitman. Like other bohemian clubs, the Dill Pickle was an intercultural site that drew audiences with an open appeal to taboo subjects, especially sex and radicalism.

Chapter 3]] moves from the everyday intellectual practices of working-class urbanites and the colorful world of the open forums to an exploration of formal programs of “workers’ education.” Building on experiments in the socialist and women’s reform movements, workers’ education grew rapidly in the early 1920s. After a string of painful defeats for trade unions from 1921 to 1925, workers’ education remained a viable movement practice in part because it took place away from the workplace. Innovative programs, such as those developed at the Brookwood Labor College, seeded a new generation of activists trained and waiting in place as the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) arrived to transform American industries in the late 1930s.

After 1945, universities and unions grew in ways that obscured the pervasive intersections between learning and labor in the prewar years. Postwar universities became sprawling physical plants and bureaucracies as much as they were centers of intellectual encounter. The children of working-class families, who entered higher education in large numbers after the war, did so as students only. University administrators, faculty, and many students assumed that working people would rise out of their class rather than with it. Even if workers were reading, writing, giving speeches, teaching classes, and carrying out research—quintessential scholarly practices—few university-based scholars understood these activities to be legitimately intellectual when done outside of universities. At the same time, the largest industrial unions developed their own education departments that more rigorously aligned curriculum with the institutional goals of their parent unions. This change was not bad in itself; many workers faced with the task of building their new unions clamored for nuts-and-bolts programs. But the change betrayed a fundamental shift in labor’s strategic thinking. The workers’ education movement of the 1920s and 1930s had also taught practical skills such as parliamentary procedure, managing union treasuries, and labor journalism. Earlier efforts, however, had paired practical skills with broader goals and strategies for seeking power. It was commonplace before the 1940s to see the “labor movement” as a variegated social and organizational network. Worker-students learned to organize their own ethnic, gender, and occupational communities, along with their cooperative enterprises and political associations. Once they had organized these primary groups, they could more effectively act in solidarity with other groups of workers. However, the stability and power of the labor movement after 1945 made this coalitional approach seem less necessary. Individual unions could go it alone, and their educational programs tended to follow suit.

1. “A little avenue to self-mastery”

The Social World of Working-Class Readers

Ed Falkowski felt a pang of remorse as he walked to work at a Pennsylvania coal mine in the fall of 1916, two weeks shy of his fifteenth birthday. Months earlier, in a detailed “self-analysis,” the grandson of Polish immigrants had confidently declared himself to be well educated and ready for work. He enjoyed reading books of science, he explained in the neat cursive of a public school student, and “the best novels,” including those of Dumas, Hugo, Tolstoy, Poe, and the Polish author Henryk Sienkiewicz. He knew that work was the more practical and manly path, but he felt his resolve weakening as he parted ways with his former schoolmates and, like his father and grandfather before him, went to work in the local mine. As he wrote in his diary that night, “I felt kind of queer today because I missed school. However, the greatest education a young man can get is that gotten by earning his own living, so I see I am attending the High School of Life, and not that of Shenandoah, Pa. And more—a graduate of the H[igh] S[chool] of Life is much more respected than a graduate of H[igh] S[chool] of Shen[andoah]. I am satisfied as far as that part is concerned.”[24]

Falkowski’s enthusiasm for what he called “industrial education” did not survive its encounter with the monotony and danger of coal-mining work. Reading and fellowship with other readers became a precarious refuge from the darkness—literal and psychological—of his underground labor. He carried books down into the mine to read on his breaks and at night struggled through dense volumes with a dictionary close at hand. On days off he hiked into the hills with friends. They spent hours telling jokes, reading aloud from their favorite books, and holding impromptu debates. Over the next few years, Falkowski and his friends launched a chapter of the Young People’s Socialist League, put on plays, and edited a literary journal in their little town. Falkowski nurtured “lofty dreams of literary success,” filling journals with handwritten poems, stories, and essays. The final pages and back covers of each volume were filled with long lists of books he had read, “rescued from the slumbers of second-hand bookstalls, borrowed from public libraries, or paid for with sweaty dollars.”[25] He sent some writing off to Frank Harris, editor of Pearson’s Magazine, who wrote back admonishing him not to romanticize the life of a writer. Chastened by his hero’s words, Falkowski kept most of this writing to himself. “Would these studies open a little avenue to self-mastery?” he worried in a particularly dark journal entry. “Or would the torrential burdens of each succeeding day wash away the effects of the evening’s devotion to my studies?”[26] His plans to finish high school and go to college proved elusive, but ten years after he first went into the mines, his union sponsored him for a two-year term at Brookwood Labor College. There he learned from leading labor intellectuals and forged lifelong friendships with workers from all over the United States. The wide world seemed to spread out before him once more.

The lessons of book learning and everyday life were never as far apart as many would insist. Advances in printing technology, repeated waves of social movement organizing, and the savvy marketing of publishing entrepreneurs combined to place text before the eyes, and minds, of working people. Whether the topic was sports, romance, or revolution, printed texts became the occasion for conversations, and conversations led people to read texts. The cycle of text and talk helped people frame their own experiences. Nevertheless, what Falkowski called the “High School of Life” was jam-packed with lessons for working people. In the streets and on the job they learned about race, gender, and the power of bosses and how each of these discrete factors came together in real-time situations. Coming of age in a society increasingly mediated by commercial images, sounds, and text, many Americans learned that their own experiences could be put to use if they were packaged in just the right ways. When asked how they became conscious of the social and economic world around them, working-class activists often left out the books. As one prominent trade unionist insisted, his radicalism sprang “not from what I read, because I was active in radical circles long before I could read. It came from what I lived.”[27]

The “little avenue to self-mastery” that Falkowski sought in reading was a path that many workingwomen and workingmen took in the years before attending high school or college became commonplace. Like Falkowski, Jack Conroy grew up in a Missouri coal camp. He lost his father to a mining accident, but his mother nurtured literary aspirations while she attended to unending rounds of household chores, and Jack memorized the romantic poetry and stories that were her favorites. He edited a “camp paper” of comic strips and sporting news before going off to work for the railroad and later became a leading figure in regionalist proletarian fiction as the editor of the journal Anvil. Conroy and Falkowski met in radical circles during the 1930s and corresponded for years, sharing memories of their unlikely intellectual histories.[28] Straddling Victorian and modern approaches to knowledge, the self, and the mind, working-class readers were engaged in a process often referred to as “self-cultivation” and “self-culture.” They embraced reading as an effort to capture the “very best” ideas of human society. But their embrace of “civilization” was hardly a ringing endorsement of the culture of their social betters. As the sons and daughters of peasants, farmers, and workers, and as ethnic and racial outsiders, their claims to knowledge challenged the prevailing allocation of brains and brawn.

The High School of Life

In workplaces and homes, on the streets and in the fields, through paid and unpaid labor, working people had to think, craft ideas, and strategize in order to survive. They learned how to work purposefully in order to preserve their strength and to prolong work in order to increase their pay. They learned where to find the least expensive food and clothing, how to sew and mend, how to build their own homes, and how to harvest delicate crops without a bruise. What workers encountered on the streets shaped their perception of the social order and their place in it. As historian David Montgomery wrote, workers’ daily encounters with class distinctions visible in modern urban life convinced many that “workers’ only hope of securing what they wanted in life was through concerted action.” In the best of circumstances they could listen to the wisdom of those who had come before them and offer advice to newcomers. But knowledge did not always bring unity. Working people also learned how to understand, and act upon, divisions of race, ethnicity, and gender.[29]

Industrial managers inflicted the marks of capital with growing sophistication during the early twentieth century, but working people found ways to fight back by drawing on both experience and book learning. Social scientists of the era described a guerilla struggle between workers and their supervisors over the motion of workers’ bodies, the scale and timing of wages, and the question of who would be laid off first as work became slack. Managers had their stopwatches, slide rules, and clipboards. Workers’ knowledge was lodged in their bodies, their memories, and their social networks. The sheet metal worker Ben Reisman, a Jewish immigrant from eastern Poland, recounted one way that skill and experience gave workers a certain amount of leeway if they were wise enough to take it. Reisman noticed that the bosses announced large rush orders to see how quickly workers could fill them. Afterward, they introduced new piece rates based on the rushed pace, which translated into more work for less pay. So when a rush order came, Reisman was sure to “work very slowly, but in such a way that it not draw any attention.” Skillfully pretending to work quickly, he preserved a tolerable pace of work and an adequate income.[30]

Management consultants such as Frederick Taylor and Frank Gilbreth reorganized production to eliminate the power of workers like Ben Reisman, but instead of destroying workers’ ability to subvert the tempo of production, they splintered it into the hands of hundreds of machine operators. And while these supposedly unskilled operators remained largely nonunion until the 1940s, they used their fragmented power to claw back time for themselves, to bump up wages, and sometimes just to poke fun at the system. Researcher Stanley Mathewson, working undercover in a factory during the late 1920s, discovered how an experienced punch-press operator could easily foil management’s efficiency schemes. When the time-study man approached his work station, one operator made “a very slight alteration in the position of his right thumb” that made his machine jam frequently and lowered his output. When the time-study man went away, the operator went back to flawlessly punching out product.[31] Workers in some plants went so far as to taunt their managers over their ability to restrict production with impunity. Mathewson found the poetry of one machine operator tacked to a factory bulletin board:

HARMONY?

I am working with the feeling

That the company is stealing

Fifty pennies from my pocket every day;

But for every single pennie

They will lose ten times as many

By the speed that I’m producing, I dare say.

For it makes me so disgusted

That my speed shall be adjusted

So that nevermore my brow will drip with sweat;

When they’re in an awful hurry

Someone else can worry

Till an increase in my wages do I get.[32]

Just getting a job could be an education in American gender and racial conventions as well as in the value of putting on the right public front to employers and coworkers. Hiring agents in Northern industrial cities, for instance, associated different types of clothing with various lines of laboring work. Newcomers soon learned that they needed a different outfit to be hired out as a railroad worker, a teamster, a lumberjack, or a factory worker. One Russian immigrant learned that American bosses thought she was a Bolshevik because she wore a leather jacket and no makeup. Unable to find a job, she ditched the jacket and “dressed myself in the latest fashion, with lipstick in addition, although it was so hard to use at first that I blushed, felt foolish, and thought myself vulgar. But I got a job.”[33] Beyond the factory gates, working people derived “lessons” from all manner of experiences. Stjepan Mesaros recalled that even as a boy of twelve with only a fifth-grade education, he began to understand something of the changes taking place in rural Croatia in the early twentieth century. Although his own village retained traditional communal property rights, a nearby wealthy landowner controlled more than two thousand acres, had the most modern farm machinery, and sold his crops on the export market. In the same years, but on the other side of the world, the young hobo Robert Saunders of Kansas City liked to ride boxcars with the doors open despite being derided as a “scenery bum” by his fellow hoboes. It was the beginning of a lifelong passion for natural science that he would develop through correspondence courses and reading.[34]

The wisdom of experience was a tool but could also be a weapon and a burden. Working people might withhold their knowledge from other workers (newcomers and outsiders especially) out of prejudice, to gain advantage, or just to enjoy a little schadenfreude. Hazing was common, done for both amusement and assessment. As Floyd Dell wrote in his autobiographical novel, Moon-Calf, it was the foreman’s job to evaluate a new worker’s productivity. Workers had different standards. They wanted to know whether a new worker was one of them or “so odd as to be set utterly apart, laughed at behind his back, made the victim of hostile contempt, or, what is worse, shunned and ostracized.”[35] Dell passed muster with his coworkers in part because he was another white man. But for those who were “set utterly apart,” by virtue of race, gender, or some other status, the knowledge and hostility of coworkers could be put to devastating effect. White workers routinely leveraged their social ties to factory supervisors and union leaders, for instance, to secure good jobs for themselves and to relegate African Americans and new immigrants to the lowest paying and most unpleasant tasks.

The defeats and injustices that were the daily lessons in what Falkowski called the High School of Life could turn working people toward collective action. But workers also learned to keep quiet: to go along and get along, to abandon their dreams as unrealistic, to bow their heads before their social betters, and to stay in their place. Chicagoan Rosella Burke had hoped to finish high school and rise above her working-class roots, but the Great Depression intervened, forcing her to quit school and find a job. “I began to feel chilly inside when I thought of the future,” she wrote in a labor college essay. “I knew that once a worker, always a worker.”[36] The St. Louis union leader Ernest Calloway said he “grew up hating white people” after witnessing the lynching of a friend in West Virginia. The vision and smell of the crime scene stuck with him like a toxin, limiting his effectiveness as an organizer, he came to believe. “Later I found hatred a waste of time,” Calloway concluded. “What you have to deal with are institutions, laws, customs. I have spent 50 years working hatred out of my system.”[37]

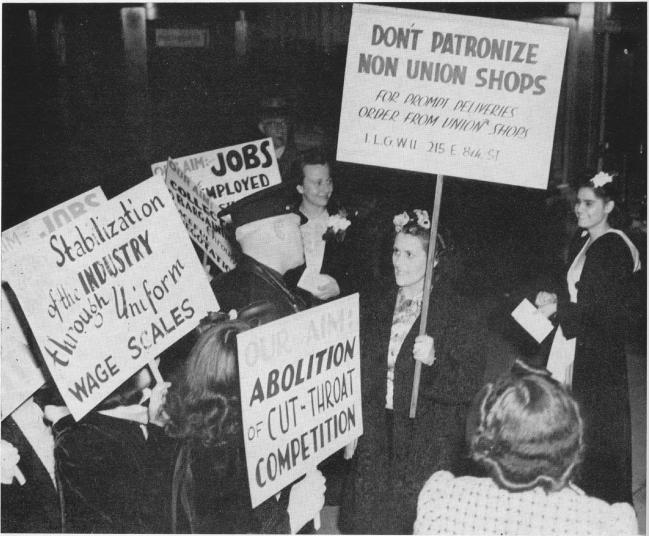

“My gateway to the world”

Most who claimed to be “self-educated” had some formal schooling, however intermittent or incomplete. They chose the label as a badge of honor in the context of a labor movement that increasingly included formally educated intellectuals.[38] Some of the self-educated grew up on farms and began working as young children. Lewis Evans, leader of the Tobacco Workers International Union, said he “went to work at a tender age” and after eighteen months of formal schooling had “many years in [the] school of hard knocks, with midnight oil, poor light, good books, and a dictionary.” For a few, self-education was a statement of dissatisfaction with the conservative curriculum of public schools. Roy Woods, an electrical worker and local workers’ education activist from St. Paul, Minnesota, attended a Baptist College, a technical school, and the St. Paul Labor College but considered himself “self-educated in economics and sociology.” Among those who identified as “self-educated” were prominent radicals like the German-born Anton Johannsen, a leader of Chicago’s woodworkers, and the Russian-born Pauline Newman, a gifted organizer and leader of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU). Others were well-known conservatives, like the trade union leader John P. Frey, who first went to work at age nine and then “received a little schooling until [the] age of 12.”[39]

Whatever amount of schooling they acquired, the self-educated struggled to master text and put it to use. They worked into the night, accompanied by dictionaries and notebooks. They listened to lectures conveying or arguing with the ideas in books, and they talked and talked about ideas until they annoyed their friends and family members. This cycle of text and talk helped to create a public sphere that circulated and amplified ideas about social order and politics. Popular reading, like the American working class generally, was fragmented by race, ethnicity, gender, and ideology. This was true for the topics different workers chose to read as well as the spaces where they did their reading. But the pervasive culture of reading among ordinary people, and the practices and institutions that developed around texts and conversations about texts, created potential for commonality. Through their mutual fascination with ideas, readers might recognize one another across otherwise unbridgeable social divides.

Research on working-class reading patterns in the early twentieth century found mass-circulation magazines and daily newspapers to be the most common reading fare, along with popular adventure and romance novels. Workers read fewer books than middle-class Americans, but they were interested in many of the same topics. For instance, the 1931 American Library Association study What People Want to Read About found that workers, farmers, housewives, and teachers all considered topics like “the next war,” “self-improvement and happy living,” and “laws and legislation” to be the most interesting for reading.[40] Among Milwaukee vocational students, a slim majority of the over three thousand surveyed in 1932 were active users of the public library, usually reading one or two books a month. Milwaukee’s young workingmen, like others in the United States, read adventure novels, among them The Call of the Wild, Treasure Island, Tom Sawyer, and All Quiet on the Western Front. Milwaukee’s young women favored their own form of romance and drama, including Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, Little Women, and Anne of Green Gables.[41] Although educators hoped to stimulate book reading (which they called “serious reading”), magazines and newspapers were more popular. The sensational literature of True Story and similar story magazines was popular among women and men, as well as Popular Mechanics for young men and Ladies Home Journal for young women.[42]

Contemporary observers were eager to draw conclusions about what particular texts did to working people and to get the right kinds of books before workers’ eyes. But reading had unpredictable results. One labor college student wrote to her former teachers that reading about personal hygiene and physical education helped her avoid ill health, and as a result she was more active in her literary club, and was “appointed editor of our club paper and in that way [I] try to inspire and encourage the value of choosing good books.” As Jonathan Rose argues in his study of British autodidacts, escapist literature had its own logic for those trapped in unpleasant neighborhoods and work routines. Working-class memoirists in the United States often noted a similar dynamic. Jewish garment worker Abraham Bisno taught himself to read with inexpensive Yiddish romance stories and newspapers, which, as he recalled in his memoir, “opened my eyes to new worlds.” Similarly, as a boy growing up in segregated Mississippi, Richard Wright was transported by the novels of Zane Grey and other popular writers. According to Wright, the stories “enlarged my knowledge of the world more than anything I had encountered so far. To me, with my roundhouse, saloon-door, and river-levee background, they were revolutionary, my gateway to the world.”[43] Radicals sometimes decried American workers’ weak understanding of Marxist theory, but the socialist author Floyd Dell thought there was “as much truth in the soap-box phrase, ‘Labor is the source of all value,’ as in the maddening mathematics of Marx.” It was Walt Whitman, Dell argued, who wrote the “Socialist’s Bible” in his Leaves of Grass.[44]

Despite frequent encouragement to read serious books, workers most often read newspapers because they were the most accessible and pervasive form of print in the early twentieth century. On the eve of the First World War there were more than twenty-five hundred daily newspapers in the United States, with a total circulation of more than 28 million.[45] In larger cities, such as New York and Chicago, English-language daily papers competed in part by issuing at different times of the day. Readers cast off their used papers when new editions appeared, creating a great supply of free reading material for the down-and-out, not to mention improvised blankets for those sleeping outdoors. Roughly 90 percent of Milwaukee vocational school students, mainly the children of workers, read newspapers regularly with both men and women who were interested in sports, theater and movies, and crime.[46] In addition to the English-language press, every immigrant group of substantial size had at least one newspaper in its own language. Robert Park’s 1922 study, The Immigrant Press and Its Control, listed more than thirty language groups with at least one newspaper in New York City alone. In Chicago in 1930 there were twenty-five foreign-language daily newspapers publishing in twelve languages, according to historian Jon Bekken. Beyond the mainstream immigrant press, radicals and labor activists produced a wide array of periodicals ranging from the handwritten “Fist Press” of Finns in Canada to the commercially successful Yiddish-language Forverts (Forward).[47] A 1925 directory counted nearly six hundred labor movement periodicals across the United States, including thirty-two socialist papers, twenty-nine communist papers, and fourteen associated with the Industrial Workers of the World.[48]

The simple language of many English-language daily papers that made them accessible to broad audiences also made them a useful resource for immigrants with limited English language skills. Working as a domestic servant in Michigan, sixteen-year-old Swedish immigrant Mary Anderson learned English by listening to her employers’ dinner table conversations and “by reading the morning paper over and over again until finally it occurred to me what the words meant,” according to her memoir. Anderson may have been an unusually intelligent domestic servant; she went on to become a union organizer, a Women’s Trade Union League activist, and the first director of the Women’s Bureau in the U.S. Department of Labor. However, the use of English-language newspapers was common among immigrant workers. For instance, a survey by one New York City Russian-language newspaper found that a quarter of its readers also read English-language papers, many of these readers simply scanning the headlines in English, because “these are easy to understand, and you know all the news.”[49]

Newspapers have a deep connection to the formation of nation-states, helping to constitute a shared public sphere and what Benedict Anderson called the “imagined community” of the nation. Immigrant newspapers had a dual role in this respect, supporting a culture of nationhood among groups of immigrants while also crystallizing links between the immigrant community and its new American surroundings. In his study of Polish newspapers in Chicago, for instance, Jon Bekken notes the long-running dispute between Catholic and radical papers, which each claimed to be the voice of Polish culture and viewed the other as a traitor to the Polish people. This debate, and the circulation numbers it stimulated, reflected a growing Polish American reading public.[50] By reading newspapers that were published in the United States but written in their own languages, immigrants reaffirmed their ethnic communal bonds while contributing to the logic of ethnic pluralism that would become a national ideology in the United States during the mid-twentieth century.[51]

In his study of early twentieth-century New York City, Tony Michels places newspapers at the center of a fervent Jewish radicalism that was distinctly American. Yiddish newspapers reported local and European news and were filled with educational articles on science, health, and politics. The socialist Forverts, with a circulation of more than two hundred thousand in the 1920s, was the anchor for what Michels calls a “socialist newspaper culture” that included popular dances, excursions, and educational programs promoted by, and promoting, the publication.[52] Although Forverts would become one of the most successful left-wing media businesses in the United States, it began as a series of public performances in New York’s Rutgers Square during 1897. Completely lacking funds to publish a physical newspaper, the editors gathered donations by hosting “spoken newspapers.” Prefiguring similar staged news events that would occur during the New Deal more than three decades later, these performances featured news, editorials, poetry, announcements, and even letters to the editor. According to Michels, “Reading a [Yiddish] newspaper was as much a collective endeavor as an individual one.” Many immigrant Jews from Eastern Europe arrived with very limited literacy skills. Few had seen a Yiddish newspaper before arriving in America, and the American papers were written in a local style of Yiddish that was difficult to understand even for some educated readers. As a result, Jewish workers read to each other at home, in public, and in their own self-education societies.[53] The most successful of these, the Arbeter Ring, or Workmen’s Circle, grew to be the largest Jewish workers’ group in the United States by World War I. Originally organized by rank-and-file socialist workers in New York City, the Arbeter Ring combined education, mutual aid, and recreation, inviting all who were in sympathy with “freedom of thought and aspiration, workers’ solidarity, and faithfulness to the interests of their class and its struggle against oppression and exploitation.” With thousands of members and a healthy balance sheet, the Arbeter Ring also contributed to many socialist and union-organizing efforts, as well as to left-wing educational initiatives such as the Rand School of Social Science.[54]

For many African Americans contending with the aftermath of slavery and the rise of Jim Crow, literacy implied liberation and personhood. In the pre–Civil War South, reading was taboo for slaves and punishable with violence. As Frederick Douglass’s master had warned, teaching the enslaved to read “would forever unfit him to be a slave. He would at once become unmanageable, and of no value to his master.”[55] The incomplete work of emancipation and Reconstruction and the advent of the Great Migration stimulated a rich publishing and reading culture among African Americans in both the South and North. As Steven Hahn notes, black Mississippians alone opened nearly 150 newspapers and magazines between 1890 and 1910. In Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, and New York, where African Americans were moving to take jobs in industry, social and literary clubs became sites of discussion about race “uplift,” and their members eagerly consumed the newspapers and magazines that spoke to their community’s most pressing issues. Working-class autodidacts, like the Caribbean-born Hubert Harrison, became regular contributors to African American news outlets as well as important voices on the race question within the American left and Pan-Africanism.[56] Northern newspapers like the Chicago Defender traveled deep into the South bringing news of jobs and the vibrant cultural life of the city, and publications like the NAACP’s Crisis and the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters’ Messenger regularly featured book suggestions for readers.[57] As a black trade unionist in Alabama told sociologist Horace Cayton in the 1930s, “Colored people do more reading. They read these different books as the union gives them.” This observation was also backed by a white union leader who noted that black members complained right away if they didn’t get the copy of the American Federationist. The effect was especially profound for those who took on leadership roles in newly created union locals of the 1930s, Cayton found. They maintained the account books and correspondence and grew increasingly assertive on interracial bargaining and grievance committees.[58]

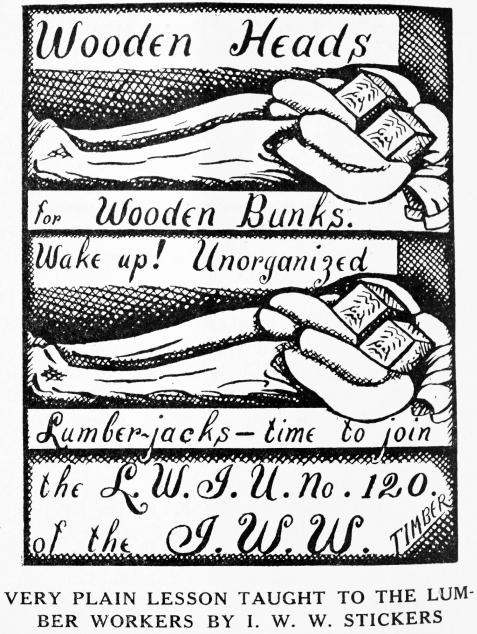

Those American workers who were actively engaged in radical and progressive politics encountered a particularly rich print culture that focused on issues of economic inequality. The Socialist Party, under the leadership of popular trade unionist Eugene V. Debs, was a mass political movement that included moderate reformers (such as those advocating public ownership of water and power) as well as militant industrial unionists and revolutionaries. Trade unionism was also in an upswing during and immediately after the First World War. A booming industrial economy and tentative government support for collective bargaining helped drive union membership above 20 percent of the workforce. Nonconformist and radical ideas circulated freely among precarious workers in North America’s far-flung industries, spurred on particularly by the Industrial Workers of the World, a revolutionary union movement founded in Chicago in 1905. Although the IWW, or the “Wobblies” as its members were known, successfully organized wheat harvesters, oil field workers, miners, lumberjacks, and textile workers in the World War I years, they were as much an educational organization as a union. The two weekly English-language newspapers, as well as a number of foreign-language papers either directly affiliated or politically oriented toward the IWW, were full of reports from rank-and-file organizers, commentary on current events, theoretical debates about unionism, and book reviews. Its growth stymied by employer and government repression, the IWW nevertheless influenced the course of unionism by educating thousands of young workers in a practically oriented Marxism that emphasized the power of workers’ direct action over politics.[59]

The IWW and the Socialist Party had officially parted ways after 1912, but left-wing socialists remained close to the Wobblies, and in many local struggles the two groups worked together. Radical workers also came together in a variety of anarchist, socialist, and reformist organizations, adding to the effervescent nature of radicalism in American cities during the era. The formation of the Workers (Communist) Party in 1919 heralded the fracturing of this precarious coalition into many warring camps, but connections of sentiment and history remained, especially while admiration for the young Soviet Union was strong in left-wing circles. While factionalism divided the left organizationally, it also stimulated the creation of independent educational and propaganda initiatives available to workers interested in self-education. During the early 1930s, the Communist Party’s John Reed Clubs and its network of party-supported schools, bookstores, and publications became important venues for popular education in larger industrial cities. The creative vitality of Communist Party artistic and literary programs has drawn a good deal of scholarly attention, but the Communist Party was rarely the only player on the field. As Michael Denning argues, the Popular Front of the 1930s was the meeting ground of leftists and liberals from a variety of organizational and intellectual positions.[60]