Urban Scout

Rewild Or Die

Revolution and Renaissance at the End of Civilization

2008, 2016

Catastrophe: burning vs. tilling

Soil aeration: sticks vs. steel

Selective harvesting: strength vs. weakness

“Primitive” Skills vs. Rewilding

“Primitive” Living vs. Rewilding

Eating a wild diet reduces population growth factors and deforestation

Eating a wild diet decreases waste products

Eating a wild diet probably reduces carbon emissions (buzzword of the year!)

Eating a wild diet increases your health?

Eating a wild diet makes you…wild!

Your diet will not stop civilization

Final Fantasy 2 (American Release)

The field guide, web information

Community-building skill-shares

Dedication

I dedicate this book to all the living and dead, all the forgotten things…

…And to all the people trying desperately to remember.

Acknowledgments

I would first and foremost like to acknowledge the largest influences on my thoughts and work: Daniel Quinn, Tom Brown Jr., Derrick Jensen, Martín Prechtel, Joseph Campbell, Toby Hemenway, Jean Liedloff, M. Kat Anderson, Nancy Turner, Jason Godesky, and Willem Larsen. Without their words I would not understand the workings of civilization or walk the path of rewilding. I will forever live in debt to them.

Secondly I want to thank my friends Lisa Wells, Nicholas Often, Brandon Rubesh, Jeff Packard, and Nancy and Matt Fitzgerald (may they rest in peace). Without their collective support I wouldn’t have become myself and certainly wouldn’t have made it through my teenage years. I will forever live in debt to them.

Thirdly I want to thank my family for supporting me and understanding me. I could not do what I do without their unconditional support and love. I will forever live in debt to them.

Fourth, I want to send my thanks to the Earth, the water, the fungi and plants, the insects and animals, the trees, the birds, the wind, the clouds, the sun, moon, and stars for talking to me even when I stopped listening. I will forever live in debt to them.

Lastly I want to thank my muse. The invisible force(s?) that makes me do what I do and whispers ideas in my ear. To the real Urban Scout, I send my biggest thanks. I will forever live in debt to you.

Special thanks to George Steel, who spent hours nagging me to put Rewild or Die back out into the world, and who dedicated hours of formatting to make it look more professional. Huge thanks to Mindy Fitch, who copy-edited this second edition.

Foreword

Hi and welcome to the second edition of Rewild or Die, Urban Scout’s anti-civilization manifesto!

At some point I gave up on this project and began a complete rewrite, but I’m not sure if I’ll ever finish that, as I abandoned the Urban Scout project in favor of my nonprofit Rewild Portland, which now consumes the majority of my time and energy. I was also a bit embarrassed about the quality of Rewild or Die, in that it was full of typos (granted it is also written in an experimental version of English). But still. I was nervous that my affiliation as Urban Scout (a bridge-burning asshole, critic, and blogger) would affect my ability to build relationships that would help Rewild Portland grow. I don’t agree with everything Urban Scout said or did; in fact I’m not really even that into his voice anymore. BUT, two words: George Steel. My friend George Steel just wouldn’t allow me to kill Rewild or Die. He demanded that I keep it up. I told him that if I were to put it back up, it would need to be seriously copy edited and slightly edited for content. He said he could do the typeface, but I needed an editor. I’m a broke environmental educator working three jobs and don’t have the money to pay a professional copy editor. Luckily I met Mindy Fitch, a professional copy editor, and was able to convince her to edit my book. Without those two, I would have let this project continue to fade away.

It’s strange reflecting back on the totality and various iterations of my Urban Scout project. It’s been years since I donned a loincloth and took to the streets to light bowdrill fires, years since I wrote an angry, caffeine-enraged blog. Urban Scout is gone for now. So what happened? Where did he go? Longtime readers often ask me this question. In brief I say that Urban Scout was a moniker, a muse, and I’ve moved on. But this feels unsatisfactory to me, so I’ll go into more detail.

Urban Scout started out as a fictional character created by me and a friend. He was the protagonist in a short film we made during the summer of 2003. He became more of an alter ego and muse for me in late 2004 as the film wrapped up, and from there he turned into a blog and persona. My blog was originally titled The Adventures of Urban Scout. I wrote that Urban Scout was “part fact/part fiction, part man/part myth.” I said that I tried “to use the comedic irony and novelty of our situation as a clever disguise to cloak and spread a truly sustainable worldview, for a time beyond our own.” The blog and online persona were very active from about 2006 to 2009. By 2011 I wasn’t writing much anymore, and my Rewild or Die book tour in the spring of that year was sort of a swan song for Urban Scout. From time to time I hear his voice in my head, and it feels like I have to hold him back. It’s not really me, but it’s something deeper that speaks through me from a far-off place. That’s all I can really say about that.

Looking back now is weird. I had to get my own identity back, learn to interpret what Urban Scout says and filter it through my own head rather than just give him the reins. I’m able to take what he says and feels and translate it into something more broadly “appealing.” However, that’s not particularly my goal. My goal since 2000 has been to actively create a rewilding community in Portland, Oregon, through Rewild Portland. Urban Scout has helped me clarify my own purpose and understand the power of the muse. I’m too sensitive, though. Urban Scout doesn’t give a darn what people think, really. But since we share the same body, or rather because I let him use my body and mind as a vehicle, I get blamed for his assholery. My heart just can’t take it anymore. I’m a nice person and I want people to like me. I had to shut him up because his spirit is one of “truth speaking,” and generally people don’t want to hear the truth, especially when it comes from an angry-sounding dude. Now that I don’t give my muse total creative control (so to speak), I feel much happier, and I’ve made a lot more headway in creating the kind of life I want to live.

I look back at the Urban Scout years with fondness, but as I read these chapters I realize I’ll never really be happy with Rewild or Die, in part because I do not feel as though I wrote it. It is Urban Scout’s book. My new book on the same topic, if I manage to finish it, will be vastly different from his. I am tentatively calling it Rewild and Live.

Peter Michael Bauer, October 2015

A Quick Preface

I didn’t write this book to change people’s minds about civilization, or to stand as “the word” of rewilding, or to prove to the civilized that a horticulturalist or hunter-gatherer way of life works better for people and the planet than the devastating effects of agricultural civilization (okay, maybe a little). Many other books exist on those topics, full of wide-ranging archaeological, historical, ecological, and anthropological evidence (see my bibliography!). With this book, I intend to clarify the meaning behind this cultural renaissance we call rewilding. I do this through sharing my experiences and thoughts on rewilding in an attempt to shed light on elements of rewilding that some may not have seen.

The thoughts in this book reflect my current level of experience and collection of evidence as of 2008. My thoughts on these topics will most likely change over time with new experiences and different pieces of evidence. Honestly, I don’t agree all that much with some of the things I’ve written here. But I feel getting the ideas into the world outweighs any hesitations for publishing this work. I could write a whole Literacy vs. Rewilding chapter about how the written word, like the verb to be (see “English vs. Rewilding”), plays god by not allowing things to change the way they did in oral cultures. But maybe I’ll save that for another book.

Blah, blah, blah. That said, I have gleaned a lot of information and had countless experiences with rewilding in my life. Though I don’t claim expertise, I will stake my claim for the experience I do have! This book works as a tally of my experiences and accumulated thoughts on rewilding. Love it or leave it.

Rewilding: An Introduction

Rewild, verb: to return to a more natural or wild state; the process of undoing domestication

The first time I saw the word rewilding, it grabbed me immediately. I knew that at long last I had a word to describe what I do. For a decade I had used many words attempting to describe my lifestyle: wilderness survivalist, primitivist, anti-civilizationist, tracker, naturalist, permaculturalist, environmentalist, green anarchist, anarcho-primitivist… The list went on and on. Nothing quite fit until I found rewilding.

No other word I’ve found encompasses the act of abandoning civilization

and its roots in domestication like rewild. It also struck me because,

as a verb, it implies an action, a process, rather than an end point. An

obvious premise sits in this word: giving something back its wildness.

Wildness means a lot of different things to a lot of different people.

But let’s go with dictionary.com’s definition:

Wild, adjective:

Living in a state of nature; not tamed or domesticated: a wild animal: wild geese

Growing or produced without cultivation or the care of humans, as plants, flowers, fruit, or honey: wild cherries

Uncultivated, uninhabited, or waste: wild country

Uncivilized or barbarous: wild tribes

Combine that with:

Re: a prefix, occurring originally in loanwords from Latin, used with the meaning “again” or “again and again” to indicate repetition, or with the meaning “back” or “backward” to indicate withdrawal or backward motion: regenerate; refurbish; retype; retrace; revert

Considering these definitions, particularly the first entry for wild (“living in a state of nature”), it makes sense to define rewilding as a return to a more natural state.

Why do definitions matter? People must have a shared reality in order to work together in that reality. I once got into the most insane argument with a man who refused to share reality with me, claiming that “nothing is real” and “there is no such thing as facts.” These arguments looked more like philosophical masturbation than practical thinking that would lead to taking actions to create a sustainable planet. While I agreed in the philosophical sense with him, it didn’t help anyone to make choices about their actions, and to make those actions in the real world. While I don’t believe in the concept of “facts,” I do believe that we can agree on shared observations of reality. We can observe that agriculture destroys the soil. If we can’t share that reality, we can’t work together to change our subsistence strategy to one that builds soil. Similarly, if we can’t share a reality of what it means to rewild, the word might as well mean nothing at all. The more clearly we define an idea, the easier time we will have using it for practical purposes.

In a sense, I will claim ownership of the term rewilding, in that my life’s work centers around caretaking the idea of what it means to return to a wild, undomesticated life. That, to me, means a hunter-gatherer lifestyle in its wholeness. I don’t think of rewilding as some new buzzword or some small scene of people or a just wildlife conservation tactic. I see it as a complex lens through which I view the world. This lens helps me to make decisions about how to live my life.

Now, some contention may lie in that I strongly advocate against running away to the wilderness (which most people assume rewilding implies). While I strongly advocate against it, I still see it as part of rewilding. Because my focus lies in fostering as much rewilding as possible, running away to the wilderness doesn’t effect much change or create the hunter-gatherer lifestyle in its wholeness. It doesn’t mean it doesn’t have its own merit: it certainly does! I also advocate for creating “rewilding havens,” land where people can work together to rewild. This differs from running away into the wilderness because people still have an interface with civilization to draw out its members, rather than shunning all of it and living as a hermit (which I believe also has its own merit).

When it comes down to it, though, I don’t see one “right” way to rewild. Everyone has their own limits and passions. I will continue to do what I can to build a cultural momentum of rewilding, using the fullest extent and articulation of the practical, shared definition. This shared definition gives us a clear shared goal to work toward.

The more I talk with people and read and write about rewilding, the more I find that the above definition appears oversimplified for an average member of civilization. Most people have preconceived notions of the words wild, natural, and domesticated that stem from civilization’s mythology, which means the definitions serve the purpose of convincing people to believe in civilization. This means that when an average person reads or hears the above definition they will not understand what rewilding actually means to someone who has redefined those concepts (outside of civilization’s propaganda). Therefore, the definition can obscure more than it reveals unless we simultaneously redefine several other concepts.

Now you see why I get a headache trying to explain rewilding in a couple of paragraphs. The definition begs a more complex analysis. For example, what does a wild state actually look like (compared to what our civilized mythology tells us)? How do we define natural and unnatural? How do we define domestic? What causes domestication to begin with? Why would we want to rewild? Why would you want to undo domestication? What stands in the way of undoing domestication? How do we surpass these obstacles that prevent us from rewilding? Without fully understanding the answers to these questions, the term rewilding looks to most civilized people I’ve encountered like it simply means “getting back to nature” or “primitive living.”

Rewilding refers to the action of participating in the social and economic renaissance of humans who use the preexisting social and economic models of our hunter-gatherer-gardener ancestors to recreate the sustainable relationship that humans had with their ecosystems and relatives for millions of years before the recent advent of agriculture, empire, and civilization. This critique emerged from modern ecological and anthropological studies that show how civilization, agriculture, and empire inherently destroy the landbase on which we depend for our survival. Rather than trying to fix a model built on unstable ground, rewilding creates a new culture using an ancient recipe.

Rewilders recognize that as long as empire exists, it will force people into domestication and prevent rewilding from taking place. In order for rewilding to occur, empire must not exist. This reveals one of the complexities of rewilding in comparison with, say, the idea of “simple living” or “getting back to nature.” The collapse and removal of empire stands as a pivotal topic in rewilding.

In order to accomplish rewilding, rewilders practice a multitude of skills such as innovative team building, storytelling, martial arts, and ancient hand crafts like brain-tanning deer skins into buckskins and making tools from stone, bone, and wood. Because rewilders see rewilding as part of a transition culture, they do not shun the use of modern technologies such as computers, guns, and cars, knowing that those technologies rely on an unsustainable industrial economy and will not last through the end of empire.

In order to create a holistic culture empathetic to the land and our other-than-human neighbors, rewilders emphasize storytelling and sensory exercises that provide experiences in animism. Animism, which lies at the heart of rewilding, refers to a way of seeing and experiencing the world and its other-than-human members as beings who demand respect and not inanimate objects put here for humans to exploit.

Creating and maintaining wild or feral cultures marks the goal of rewilding. Rewilding does not denote an end point but rather a continuing cultural process of learning how to relate to the land, people, and other-than-humans in a sustainable way. Even wild or feral cultures practice the art of rewilding.

After all this time, I’ve finally come up with a (rather mechanistic) definition that I think will at least explain a lot more to the average person, and perhaps pique their interest and let them see rewilding through a more complex lens than the previous definition:

Rewild, verb: to foster and maintain a sustainable way of life through hunter-gatherer-gardener social and economic systems, including but not limited to the encouragement of social, physical, spiritual, mental, and environmental biodiversity and the prevention and undoing of social, physical, spiritual, mental, and environmental domestication and enslavement

Domestication vs. Rewilding

How do we define wild? We now know that “wild” hunter-gatherer cultures greatly manipulated their environments. Where do we draw the line between wild and domestic? Rewilding means undoing domestication. If we wish to understand what that fully entails, we must examine the words wild, natural, unnatural, and domestic as we have come to know them in the context of civilization.

Domestic comes from the Latin domesticus, meaning “belonging to the household.” Domesticates belong to the household. We could interpret this in many ways, depending on our own personal perception of “the household.” If we perceive the whole world as a house that we all (humans and other-than-humans) belong to, I see no problem with the term domestic. Culturally, however, we know that civilization does not define the word in those terms, but in terms of belonging to the house of humans. After all, the word has an uncle, dominion, which god told us in Genesis we hold over all things natural. Dominion comes from the Latin dominionem, “ownership.” Let’s not forget dominion’s nephew, domination, which means “to rule or have dominion over.” Or, if we think back to the terms of a “house,” it means “lord, master of the house.” Domestic refers to all forms of creation that we (civilization) master over.

The term master, as opposed to collaborator, demonstrates the basic differences between wild and domestic relationships: control. The difference between a wild and free, commensal symbiotic relationship and a domestic, parasitic one involves the commitment to control or the will to have power over rather than share power with.

In The Culture of Make Believe, Derrick Jensen defines natural and unnatural in this way:

Any ritual, artifact, process, action is natural to the degree that it reinforces our understanding of our embeddedness in the natural world, and any ritual, artifact, process, action is unnatural to the degree that it does not.

If every living creature has a connection to those it consumes and those who consume it, the genetics of both will affect both. Domestication removes all variables concerning the life and genetic changes of an organism. When we do not allow other animals to eat plants (through fences, “pest” control, etc.), we remove a variable of genetic strength. When we breed animals and plants for genetic traits based on living in an entirely human-manipulated environment, we remove the variables of dynamic environments and they lose genetic strength in the real world. Over time this makes them dependent on human culture (specifically agriculture, factory farming, and civilization). It also feels like a lot of work for the controller (constant weeding, tilling, fertilizing, genetic engineering). Domestication ignores our embeddedness in the natural world and seeks to control it. Using the above definition of natural and unnatural, we can refer to the process of domestication as unnatural.

Controller or controlled, both species breed weakness into their genes, and in our case culture. Put a civilized human in the “wild” (which to domestic peoples means “anywhere outside our control”), and they will have a very difficult time meeting their most basic needs. We have become so dependent on domesticated species that we have physically and culturally domesticated ourselves.

A natural relationship breeds mutually beneficial relationships that build strength in a given and changing environment with variables outside of human control. As greater environments change through shifts in climate and other environmental factors, these relationships maintain a fluctuating baseline. Civilized people believe that in nature you must “eat others or find yourself eaten.” Yet the reality of nature suggests that you must caretake the things you eat, or you will die. If five species eat salmon, all five of those species must caretake the salmon. If one species caretakes wheat (and prevents anyone else from eating it), the web of support breaks and both wheat and wheat eater become weak. With many life forms tending each other, if one species chain breaks, the other species will not feel as stressed, since many others tend to them.

Rewilding means returning to a more natural or wild state and reversing domestication. It means increasing our commensal symbiotic relationships with humans, and more importantly with other-than-humans. This doesn’t mean we just “let things grow.” Commensal symbiotic relationships do not mean “hands off!” It means learning to tend the lives of those we eat, so that they keep on living and so do we.

Agriculture vs. Rewilding

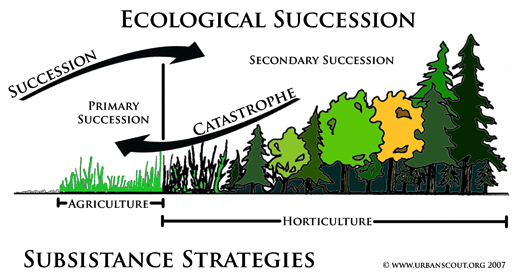

In order to understand the destructive nature of agriculture, you must understand the phases of ecological succession. Ecological succession refers to the phases of growth from barren rock to a climax forest. The loss of biodiversity that creates a blank slate generally occurs through a disturbance such as fire, flood, or volcanic eruption.

Primary succession refers to the earliest phase of ecological succession, characterized by the growth of pioneer plants such as fungi, grasses, and annual wildflowers. These plants love sun, barren rock and/or disturbed soil, and serve to create quality, life-giving soil that makes secondary succession possible. Secondary succession refers to the later phases of ecological succession, marked by the growth of larger perennials such as shrubs and trees, which need established soil. These phases work towards creating the final stage of succession, a stable ecosystem, referred to as a climax forest.

Agriculture refers to a process of cultivation that simulates natural catastrophe (such as burning, flooding, tilling) to inspire annual pioneer plants, specifically grasses like corn, wheat, and rice. From its foundation, agriculture causes a loss of biodiversity. Agricultural subsistence means keeping the land in a fixed state of primary succession. Agriculturalists have a fondness for monocropping. Monocropping sets up the perfect environment for insects who love to eat that particular plant. Slowly but surely, tilling to create continuous primary succession exposes the soil to wind and rain until it erodes away entirely—so much so that in order to grow crops, fields require the importation of mineral resources known as fertilizer.

Ecological succession shows us that plant growth naturally progresses to climax forests. Agriculture works against, rather than with, this natural progression. Trying to stop insect populations when you have provided them the perfect habitat requires a lot of work. Making fertilizers that you would not need if you followed the flow of succession requires a lot of work. Not only does this form of subsistence destroy the environment, it also requires a massive amount of labor (which characteristically comes in the form of a slave class).

Agriculture creates an extreme vulnerability to crop failure from large insect infestations, disease, and climate change. This inevitably leads to famine. If you put all your eggs in the agriculture basket, you die. In order to combat this, agriculturalists invented food storage, aka the granary. Initially this looks great—a little more work on their part, but in the end they don’t starve to death during crop failures. Unfortunately, food surplus affects the population growth of a species inspiring it to grow.

Any animal population with a surplus of food grows to match that surplus, humans included. A population cannot grow without an increase in food availability, usually through an increase in “efficiency” in food production. Therefore a population explosion implies more food production. Full-time agriculturalists with a food surplus create a positive feedback loop of growing more food to feed an ever-expanding population. Eventually the soil beneath them degrades and washes away, and they cease practicing agriculture, as we have seen with many civilizations; or as in the case of our civilization, they expand into neighboring forests and keep growing.

Civilization, a way of life characterized by the growth of cities, works as an ecological phenomenon occurring when agricultural peoples reach a certain population density due to their food-surplus-induced population growth positive feedback loop. Though not a catastrophe in the “natural” sense, as in fires, floods, volcanic eruptions, and comets, in ecological terms you can literally call civilization a catastrophe. Perhaps “cultural catastrophe” would serve as the best description.

It feels worth noting that many First Nations peoples and other indigenous peoples around the world heavily cultivated the lands they lived with in a manner very different from agriculture. These methods have many names, but I prefer the term horticulture.

Horticulture refers to cultivation by means of secondary succession: perennial shrubs and trees, aka forests. This still involves burning, selective harvesting, crop rotation, pruning, transplanting, minor tilling, and weeding. These methods can also lead to population growth, but they do not lead to overall loss of biodiversity and soil as agriculture does. This also does not mean to say that horticulturalists never used agricultural practices, but that agricultural foods never formed a staple of their diet.

Many people have a difficult time understanding the differences between horticulture and agriculture. This may occur because some agricultural strategies cross over into horticultural strategies. Linguistically the term agriculture comes from the Latin agri (field) and cultura (cultivation). Horticulture combines hortus (garden) and cultura. Cultivating a field versus cultivating a garden. We can see the implications of agriculture’s monocropping primary succession plant obsession in its very name. We can also understand the implications of horticulture’s diversity of plants and smaller-scale style through its name.

We can distinguish between the two by observing the results of how the strategy affects the land. Does it create more biodiversity or less? Does it strengthen the biological community or weaken it? It seems like a good idea to create a list of horticultural and agricultural strategies and reveal how and why you can use them to create more life, or misuse them to create less.

Agriculture uses strategies of cultivation such as transplanting, seeding, tilling, burning, pruning, fertilizing, selective harvesting, crop rotation, and so on. But the main difference between agriculture and horticulture involves agriculture’s focus on using these tools to create one habitat: meadow or field. Horticulture uses the same strategies of cultivation to promote ecological succession and diversity of landscapes. Let’s go through and find out for ourselves.

Catastrophe: burning vs. tilling

When I hear the word tilling, the classic image of a farmer and his plow pops into my head. I can see the deep trenches the plow has cut into the land in pretty rows. I can smell the sweetness of the upturned earth. Tilling works as an artificial catastrophe. Burning also works as a catastrophe. Frequent small-scale burns return nutrients to the soil without killing the roots of desired species. Burning also eliminates succession and prevents large-scale fires from occurring.

Soil aeration: sticks vs. steel

Gophers and moles dig holes and aerate the soil. Foragers use digging sticks to forage roots, tubers, and rhizomes. This breaks up the earth, making it easier for the roots to grow, and aerates the soil. The plow, on the other hand, goes too deep and destroys the mycorrhizal network of fungi that distributes nutrients to plants. It also aerates the soil, but it goes too deep and causes the soil to dry too much, which leads to soil loss and erosion.

Irrigation: sticks vs. stone

Beavers build small-scale dams with sticks that create flood plains, wetlands, and marshes that provide habitat for aquatic life. Humans too have replicated this on a small scale. Civilization builds insanely large dams of stone that destroy the river’s life by draining too much water and drying it out.

Seeding

Any squirrel will tell you, if you want to ensure that you have more to eat year after year, plant a few more seeds than you’ll dig up to eat during the winter.

Transplanting

Transplanting looks the same as seeding to me. Do you consider a seed a plant? What about seeds that germinate into plants and then grow through rhizome? Some willow trees can lose a branch, only to have that branch drift downstream and grow into a whole new plant! Wait, would you consider it new if it came from a preexisting tree? Do they share the same soul? Have I gone too deep for a chapter about horticulture and agriculture?

Fertilizing: poop vs. petrol

Shit. We all do it. Poop turns into fertilizer. Controlled burns also work as fertilizer by quickly breaking down dead wood and making their nutrients bio-available. Agriculturalists just import nutrients from other areas, and in the case of oil, from under the ground.

Pesticides

Foragers and horticulturalists also used burning to keep down insect populations. Civilization uses toxic chemicals that poison not only bugs but also the soil, the water, the birds, and our own bodies.

Pruning and coppicing

Beaver pruning stimulates willows, cottonwood, and aspen to regrow bushier the next spring. Black bears break branches. Hunter-gatherers prune trees too, to encourage larger yields and materials for making tools like baskets.

Monocropping

Horticulturalists don’t use this technique, which exists uniquely to agriculturalists. Probably the larger symptom of control and domestication. No weeds in my field!

Selective harvesting: strength vs. weakness

Every animal uses this technique. Wolves thin out the sick and weak deer. Sometimes you take the weak so the strong survive. Sometimes you eat the strong so your poop will fertilize the seed. Selective harvesting shows us that systems evolve to work in cooperation. If we look closely we can see the outcome of our decisions. Domestication also works as a form of selective harvesting, only rather than strengthening the plant or animal, it weakens it. I go more into this aspect in “Domestication vs. Rewilding.”

Seasonal rotation

Aside from building strength through selective harvesting, seasonal rotation of lands and food sources, and even yearly rotations, allow an area to restore itself from the temporary impacts of the harvest.

Many people also make the assumption that those who practice horticulture long enough eventually begin to practice agriculture. I’d like to suggest that this perceived continuum from foraging to agriculture does not exist. I’d like to suggest that a continuum between foragers and horticultural peoples exists, but agriculture appears as a completely different beast. It works in opposition to the fundamental restorative principles that shape the continuum between foraging and horticulture. Although it uses mostly intensified horticultural practices, it disregards the most basic ecological principles.

Foragers, hunter-gatherers, and horticulturalists used (and in some places, continue to use) the aforementioned methods to build soil and create varying habitats of succession, creating more ecotones and increasing biodiversity. If a continuum existed, we would see a decrease in biodiversity in each new phase of the continuum: hunter-gatherers would decrease biodiversity more than foragers, and horticulturalists would decrease biodiversity more than hunter-gatherers. Because we don’t see this, we can guess that agriculture exists outside of that subsistence continuum as a completely different beast.

Many people use the term agriculture too loosely. Expressions like sustainable agriculture make no sense when you take into account the origin of the word agriculture. Sustainable agriculture looks like an oxymoron. We need to differentiate between agriculture (the field or monocrop) and horticulture (the garden of forest succession) if we want to live sustainably.

This doesn’t mean that everything labeled “horticulture” falls under a sustainable practice. On the contrary, most fruit-bearing trees these days come in the form of clones—one plant spliced onto the rootstock of a similar plant and pruned to encourage the graft, a perfect clone of the original. Generally these plants have no fertility on their own, which means they rely completely on their human caretakers. I can’t think of a worse fate nor a better example of domestication.

To take the next step, we must translate this knowledge into practical use. The question presses: How can we change our subsistence strategies from agriculturing supermarkets to horticulturing-hunting-gathering villages? How can we go from stupid-civilized-urban-dweller to hotshot-rewilding-horticultural-hunter-gatherer?

Keep reading.

At the core of rewilding lies the dismantling and abandonment of agricultural subsistence, a catastrophic practice to which we all act as slaves. We must create a new way of life using such ancient techniques as horticulture and its modern cousin, permaculture, as a transition to or to supplement a hunter-gatherer lifestyle.

Generalization vs. Rewilding

We know that humans who lived here for millions of years did so in a sustainable fashion. We know that civilization has caused one of the largest mass extinctions in only a few thousand. We know that the thousands of cultures that did not practice agriculture and create civilizations lived in a sustainable way. We know that a lot of those cultures had cultural contamination by contact with civilization by the time anthropologists wrote about them. Fortunately, enough writing on less-touched cultures exists so that we can estimate how much civilization contaminated an indigenous culture before anthropologists wrote about them. For example, when someone argues that rape and spousal abuse existed in indigenous cultures, we can often link that behavior to post-contact with civilization. I don’t mean to say that all hunter-gatherers had a perfect life. Assuredly not. Humans, after all, belong to the animal kingdom, and environmental pressures can cause any number of conflicts.

Respecting indigenous traditions and mindful of cultural appropriation, I approach these cultures from a systems perspective, without fixating on their particular dogmas or ceremonies. I generalize because I speak of the overwhelming similarities in their respective systems approaches to participating with the land and each other. I generalize because the evidence says I can. Any exception usually reflects some form of contamination by civilization (as in the example of rape) or a cultural difference (like group sex, circumcision, warfare) that has nothing to do with the principles behind rewilding, only working as a straw man to keep the fundamental unsustainability of civilization from coming to light. If you have trouble understanding this, please read some modern anthropology.

This all means to say that when I talk about horticulturalists, hunter-gatherers, indigenous peoples, primitive peoples, native cultures, wild peoples, or animist cultures, I generally mean those cultures that lived for millions of years in a sustainable way and had little to no contamination from civilized culture. When I use words like agriculture, agriculturalists, civilizationists, civilized, domestic, or domesticated, I refer to the current culture that does not live in a sustainable or desirable way.

Appropriation vs. Rewilding

A few (always white) people have attacked me as a cultural appropriator. If I learned a Lakota song, recorded it, and sold it to others, you could call me a cultural appropriator. If I make a fire using a bow-drill, that doesn’t count as appropriation, because it represents a piece of technology widely distributed around the world and carries no dogmatic cultural practice with it. I don’t benefit financially from the sale of particular indigenous traditional cultural practices. You won’t see me sell a line of traditional Chanupa pipes.

If I made a traditional Northwest Coast mask, in that particular artistic style, that would look like cultural appropriation. But I will talk about how the Northwest Coast cultures encourage biodiversity through their perception of, and practices with, the land. I will talk about how we can restore this relationship in our own way using the same practices. You cannot call that appropriation.

Many indigenous authors and teachers have explained that no one owns these skills. Now, that doesn’t mean I practice particular, long-standing traditions of a particular indigenous people (such as the potlatch), but that I study their systems, and the systems of my own ancestors, and create my own using the same principles.

For example, my friend Brian and I led a sweat lodge at a summer camp. That does not count as cultural appropriation because we didn’t use any particular native culture songs or themes. Cultures from around the world use sweat lodges. You sit in a little room with hot rocks in the middle and pour water on them. We also call it a steam bath. The basic principle here involves sweating out toxins to cleanse yourself. Now if you dress it with Lakota songs, and have no Lakota ancestry, that works as appropriation. If you make up your own songs or sing the songs of your own culture (I like Cat Stevens’ If You Want to Sing Out), you have started to rewild.

This subject evokes a lot of emotion in many parties. Cultural appropriation has really destroyed and further disrespected indigenous cultures affected by civilization. Rewilding does not mean appropriating native cultures. It means helping them thrive again, as we help ourselves to do the same. We all have native ancestry if we trace back far enough. Rewilding means respectfully learning from our hunter-gatherer ancestors as well as from those alive today, honoring their long-standing traditions so that we can reestablish a sustainable relationship with the land that benefits all generations of life to come.

Civilization vs. Rewilding

You might assume that writing a chapter called “Civilization vs. Rewilding” would come easy since civilization means the exact opposite of rewilding. Then I got to thinking: most people don’t know what civilization means.

American Heritage Dictionary defines civilization thusly:

An advanced state of intellectual, cultural, and material development in human society, marked by progress in the arts and sciences, the extensive use of record-keeping, including writing, and the appearance of complex political and social institutions

The type of culture and society developed by a particular nation or region or in a particular epoch: Mayan civilization; the civilization of ancient Rome

The act or process of civilizing or reaching a civilized state

Cultural or intellectual refinement; good taste

Modern society with its conveniences: returned to civilization after camping in the mountains

These definitions reek of a culture with a superiority complex. I love how the line “the appearance of complex political and social institutions” sounds like a glossed-over way of saying slavery. In order to fully grasp what civilization means, let’s go on a little definition journey. The first path we take will lead us to redefine many of the words commonly found among mythologists and anthropologists. As we explore these concepts, they will become tools, not static objects. Take this definition of a hammer:

A hand tool that has a handle with a perpendicularly attached head of metal or other heavy rigid material, and is used for striking or pounding

Notice how the definition describes what makes a hammer: a handle with a perpendicularly attached head of metal or other heavy rigid material. Notice also that this definition includes the use of a hammer: striking or pounding. This shows us an example of a dynamic definition. Most of the words I use do not include usage in their definitions. The more we begin to perceive them as tools for rewilding, the greater the need to include their purpose or use, within their definition. So that we can communicate on the same page, we’ll start by redefining and refining definitions of words in the vocabulary of those-who-rewild.

Okay, this may sound strange, but let’s start with art. How do we define this word? American Heritage Dictionary gives me this definition:

Human effort to imitate, supplement, alter, or counteract the work of nature

a. The conscious production or arrangement of sounds, colors, forms, movements, or other elements in a manner that affects the sense of beauty, specifically the production of the beautiful in a graphic or plastic medium

The study of these activities

The product of these activities; human works of beauty considered as a group

These definitions describe art physically but leave us with no understanding of why. Why do humans produce conscious arrangement of sounds, colors, forms, movements? Why do humans make stuff? Something as seemingly instinctual as art must have a purpose. Humans have a complex language and live as storytellers; art gives us a way of telling a story. Whether we use one image or a thousand, a piece of art contains a story. So the purpose of making art works to tell a story. Maybe we don’t see this in the dictionary because it serves a subconscious function? Regardless, this leads to another question: why do we tell stories?

Story, noun:

An account or recital of an event or a series of events, either true or fictitious, as:

An account or report regarding the facts of an event or group of events: The witness changed her story under questioning

An anecdote: came back from the trip with some good stories

A lie: told us a story about the dog eating the cookies

a. A usually fictional prose or verse narrative intended to interest or amuse the hearer or reader; a tale

A short story

The plot of a narrative or dramatic work

A news article or broadcast

Something viewed as or providing material for a literary or journalistic treatment: “He was colorful, he was charismatic, he was controversial, he was a good story” (Terry Ann Knopf)

The background information regarding something: What’s the story on these unpaid bills?

Romantic legend or tradition: a hero known to us in story

Yeah, yeah. But why? We use a hammer for striking or pounding. What do we use story for? Why do we tell stories? I have asked many groups this question and have heard answers like, “So someone won’t make the same mistakes,” “So we can learn from the past.” These don’t satisfy me. Maybe we should look at where storytelling came from. The word myth has many connotations, mainly bad ones. Some people hear the word and equate it to a lie. Others conjure images of ancient Greek or Roman gods. When I use the word myth I mean something very different. In order to understand civilization and its functions, we need to give myth and how we perceive it a makeover. Let’s take a look at the definition:

a. A traditional, typically ancient story dealing with supernatural beings, ancestors, or heroes that serves as a fundamental type in the worldview of a people, as by explaining aspects of the natural world or delineating the psychology, customs, or ideals of society: the myth of Eros and Psyche; a creation myth

Such stories considered as a group: the realm of myth

A popular belief or story that has become associated with a person, institution, or occurrence, especially one considered to illustrate a cultural ideal: a star whose fame turned her into a myth; the pioneer myth of suburbia

A fiction or half-truth, especially one that forms part of an ideology

A fictitious story, person, or thing: “German artillery superiority on the Western Front was a myth” (Leon Wolff)

Did you notice they made no mention of what people use myths for? I did. Three definitions above say that a myth means a story. Three include ideology. Let’s redefine a myth as a story that holds a culture’s ideology. So then, what purpose do we have in telling a story that holds a cultural ideology? In The Power of Myth, Joseph Campbell said,

The ancient myths were designed to harmonize the mind and the body. The mind can ramble off in strange ways and want things that the body does not want. The myths and rites were a means of putting the mind in accord with the body, and the way of life in accord with the way nature dictates.

If ancient myths mean to put the human way of life in accord with the way nature dictates, how do we know “the way nature dictates?” If that shows us the purpose of the ancient myths, what of the purpose of current myths? Do we have a general purpose of mythology that spans both ancient and current?

Culture:

The totality of socially transmitted behavior patterns, arts, beliefs, institutions, and all other products of human work and thought

These patterns, traits, and products considered as the expression of a particular period, class, community, or population: Edwardian culture; Japanese culture; the culture of poverty

These patterns, traits, and products considered with respect to a particular category, such as a field, subject, or mode of expression: religious culture in the Middle Ages; musical culture; oral culture

The predominating attitudes and behavior that characterize the functioning of a group or organization

Again, no description of the purpose or use or function of culture. To learn the purpose of an opposable thumb, you would study the physical evolution of the human. Similarly, to understand the purpose of culture you must study the social evolution of humans. In the preface to Iron John, Robert Bly writes:

The knowledge of how to build a nest in a bare tree, how to fly to the wintering place, how to perform the mating dance—all of this information is stored in the reservoirs of the bird’s instinctual brain. But human beings, sensing how much flexibility they might need in meeting new situations, decided to store this sort of knowledge outside the instinctual system; they stored it in stories.

If you have ever gone out animal tracking you’ll find it easy to see how the human brain developed. The brain takes in information from the senses, links it together, and forms a story. Say you come across a set of footprints on the ground. You can consider a million things when reading it. Who made it? When? Where did they plan to go? Consider the terrain. A track in the sand ages completely differently from one in mud, clay, snow, debris, or grass. Once you have considered the terrain, you must think about weather. Has it felt sunny? Rainy? Windy? All these factors age the track in different ways, and of course, each terrain acts differently too. Each animal’s track ages differently depending on weather and terrain. How can you tell that seven days and three hours ago a hungry fox traveled east in a hunting-style trot? And what other information will this tell you about the local environment? Does the fox hunt here often? If so, what does that tell you about the environment?

To get to the root of what it means to live as humans, we must look at this question: what happened here? This question separates us from other animals. We have the ability to question and tell stories in a way other animals don’t. Other animals tell each other stories too, though. A wolf out on a scout mission finds something interesting. It rubs its body onto the scent and travels back to the pack where they greet it and smell it. The wolf has carried this story in the form of a scent. The scent can only tell the wolves what lies there, but it cannot give them any more insight into the ecology or awareness beyond their senses. This shows us where humans function differently. We evolved to ask, “What happened here?” We can carry the story beyond the moment. The second part of tracking requires the ability to communicate the story to others in order to lead us to shelter, water, fire, and food. The better the storyteller, the better the chance of survival. Tracking works as the art of questioning and the telling of the story. Like the hammer, storytelling functions as a survival tool.

Human culture formed by two simultaneous evolutionary transformations. The formation of a social organization reveals the first transformation. Animals evolve into social organizations because cooperation proves advantageous for the group of cooperators as a whole. Therefore the purpose of culture becomes obvious: ease of survival. Robert Bly hinted at the second process: the externalization of instinctual survival into stories or myths. So you could say that language, art, storytelling, and myths all function as a means of survival. But wait. Because every culture differs and varies in survival ideology, myth would not function as a means for human survival as a species but for a specific culture. This means that a myth works as a story that holds a specific culture’s ideology for the purpose of survival. These ideologies serve as blueprints for a culture, coming to life through mythological enactment or ritual.

Ritual:

a. The prescribed order of a religious ceremony

The body of ceremonies or rites used in a place of worship

a. The prescribed form of conducting a formal secular ceremony: the ritual of an inauguration

The body of ceremonies used by a fraternal organization

A book of rites or ceremonial forms

Rituals:

A ceremonial act or a series of such acts

The performance of such acts

a. A detailed method of procedure faithfully or regularly followed: My household chores have become a morning ritual

A state or condition characterized by the presence of established procedure or routine: “Prison was a ritual reenacted daily, year in, year out. Prisoners came and went; generations came and went; and yet the ritual endured” (William H. Hallahan)

Because myths hold a “detailed method” of survival, we find ourselves instinctually programmed to “faithfully or regularly” follow them. When humans make choices, they enact the mythology of their culture. This means that every choice we make works as a ritual, and that ritual, again, serves as a function of survival. This brings up a discussion of free will and whether such a thing really exists. If all our choices come conditioned by a mythology, we make no choices without external influence. I watched a movie about fast cars. I made the unconscious choice to drive fast. I had enough awareness to consciously realize this and choose to slow down because of another mythology called Johnny Law. Both choices I made came from mythology: the story of fun (driving fast) and the story of consequence (getting a ticket).

Culture means more than just “the totality of socially transmitted behavior patterns.” It refers to a working system of two parts: mythology and ritual. Kept alive by transmitting its survival ideologies through mythology. This transmission leads to ritual enactment. Cyclical ideals and actions.

My definitions thus far:

Mythology: A story that holds cultural ideology for the purpose of survival

Ritual: Choices made for the purpose of survival

Culture: Socially organized humans enacting an ideology for the purpose of survival

But now we have a problem. To define a myth as story that contains survival ideology would mean to ignore that all stories contain fragments of a culture’s survival ideology. All stories would appear as myths. Since all art works as a form of telling a story, and considering that all human interaction means telling stories, you could define a myth as “human communication.” But this dilutes the definition quite a bit now. How about that word meme?

Meme: A unit of cultural information, such as a cultural practice or idea, that we transmit verbally or by repeated action from one mind to another

I hate this word. Many people do. It works as an analogy to gene but does not mimic the genetic process in any other way. Many people argue this and spend their waking hours taking it to the extreme trying to match it perfectly. But mostly I hate how dry it feels, how scientific it sounds. Not to mention the way it avoids delineating action from idea. I hate the word meme and don’t use it. I just wanted to let you know that people have used these other words, myth and ritual, to describe memes for a long, long time, and meme appears useless, just a cool analogy to gene. But for all you memetic freaks out there, this just shows another way of looking at it. Let’s break down the definition of meme: a unit of cultural information, such as a cultural practice or idea (ideologies or worldview), that we transmit verbally (story) or by repeated action (ritual) from one mind to another.

So where do myths come from? How do we form them? In The Power of Myth, Joseph Campbell and Bill Moyers discuss how myths come from people responding to their environment. Because myths form a detailed method of survival, I think we can take this one step further and say that myths (or memes) come from a culture’s relationship to the environment. The way a culture interacts with its environment. It makes sense to say that ancient survival ideologies evolved to work in accord with “the way nature dictates,” or we wouldn’t stand here today.

In Never Cry Wolf, Farley Mowat discovered a connection between the wolves’ hunting style and the health of the deer population. He found that wolves only hunt the sick or weak members of a herd. This promotes healthy genetics for the deer herds, which in turn benefits the wolves by providing a constant food supply. They give back to the deer by the method in which they kill them. The better an animal can fit into its environment, the more success it will have, as will the health of the entire ecosystem. Author Derrick Jensen calls this “survival of the fit.” Joseph Campbell called it “the way nature dictates.” Farley Mowat (and later Daniel Quinn) called it “The Law of Life.”

In other animals we call this behavior instinct. The instinctual knowledge of “how human culture fits into the environment” describes what we originally exported into story. Humans mythologized this relationship and understanding into a worldwide religion known as animism. Anthropologists of our culture studying indigenous cultures throughout the world coined the term. It appeared as though every indigenous culture they came across in their studies believed the following:

Animism:

The belief in the existence of individual spirits that inhabit natural objects and phenomena

The belief in the existence of spiritual beings that are separable or separate from bodies

The hypothesis holding that an immaterial force animates the universe

Coined hundreds of years ago by pretentious, culture-eating anthropologists, no doubt this definition appears very superficial. It lacks an understanding of the relationship to the environment that created the belief system to begin with. It lacks purpose and function. Animism serves cultures by giving them instructions for living in accord with their environments.

Looking at this definition of culture, we can see an inherent weakness. If the story becomes damaged and loses sight of “the way nature dictates,” the culture and land suffer. How does civilization’s story differ from animism? How does civilization relate to the environment, in contrast to hunter-gatherers?

Let’s look again at how good ol’ American Heritage defines it:

Civilization:

An advanced state of intellectual, cultural, and material development in human society, marked by progress in the arts and sciences, the extensive use of record-keeping, including writing, and the appearance of complex political and social institutions

The type of culture and society developed by a particular nation or region or in a particular epoch: Mayan civilization; the civilization of ancient Rome

The act or process of civilizing or reaching a civilized state

Cultural or intellectual refinement; good taste

Modern society with its conveniences: returned to civilization after camping in the mountains

Of course, conquerors write history. “An advanced state of intellectual…blah, blah, blah.” No one ever looks at what makes all this backslapping and high-fiving possible: the devouring of the world. The conquerors spend so much time thinking so highly of themselves they have little time to notice how they fuck up ecosystems. Civilization does not listen to “the way nature dictates” at all. In fact, in order to support these “advanced” systems, they not only ignore nature but actually foster a hatred of the natural world. If we look at all previous civilizations, we know that full-time agriculture gave rise to their runaway population growth, and ultimately their death as the soil eroded beneath them. I define civilization thusly:

A catastrophe created when a human culture practices full-time agriculture, causing their populations to spiral into a cycle of exponential growth, social hierarchy, soil depletion, and genocidal expansion that leads to an eventual collapse of ecosystems, biological diversity, and culture

Indigenous peoples did (and still do) not live in a culture of civilization because they did not practice full-time agriculture, nor grow to live in such density that they required imported, agriculturally produced grains from a distant country. I hate it so much when I say, “Native peoples didn’t have a civilization,” and a civilized drone says, “Yes they did! Your comment sounds so racist! They did too have a civilization, it just looked different from ours!” I have to calmly say, “Eh hem. You have no fucking idea what civilization means. They had complex cultures, sure. Sustainable, beautiful cultures that worked better than civilization.” I call these cultures. And yes, they had art and music and language and fashion and everything civilization tries to claim a monopoly on. But they didn’t build cities.

Civilization continues because its cultural blueprints (mythos) and infrastructure (ritual propagation of dams, tanks, buildings, soldiers, consumers, etc.) go unchallenged, even in the face of collapse. It exists in the ethereal realm of mythology and manifests itself in the physical through monocropped fields, concrete buildings, bulldozers, and million-men armies. Rewilding presents us with a challenge to civilized mythology, providing us with a new set of cultural blueprints based on the ancient, sustainable ones, and in full recognition of civilization’s inherent unsustainability.

Empire vs. Rewilding

A power system sits in place that keeps the rich richer and the poor poorer. This power system lies outside most people’s perception because we grow up in it, never knowing anything different, never seeing it articulated, but understanding it down to our bones. It feels as natural to us as drinking a glass of water. This power structure keeps us as slaves, forced to continue building civilization. Without empire, civilization could not, would not, exist.

For a long time now I’ve focused myself more with the sustainable living aspect of rewilding and not so much with the social structures. But with all the green technology talk I’ve begun to worry. Even though ecologically it could never happen, let’s pretend for a moment that civilization became sustainable. Sure, that might feel great environmentally, but what would that really mean for us socially?

Before the rise of cities that gave us the term civilization, empire and slavery existed. In fact, I would say that cities and civilization would not have come about without empire (rich elite with an army fueled by grain production) forcing people (slaves) to build them. What does empire mean, really, but a hierarchical social structure of masters with an army to force other humans into slavery? When people advocate for a “sustainable civilization,” they don’t realize that means they simultaneously advocate for the continuation of slavery.

A slave means someone forced into labor under the threat of death, torture, or some other form of abusive violence. It probably started kind of like this: a sedentary agricultural community had a population explosion. Something happened here. They went to their neighbors and said something like, “Give us 10% of your food or we will kill you.” Several thousand years went by, and now we have taxes, rent, food bills, water bills, health insurance bills, electricity bills, gas bills, etc. All of which everyone pays for without question: “Well, of course you have to pay taxes!” We take in our slavery as we take in the air. Once a system like this gets going it becomes very hard to stop. If you say no, they have the power to kill you and steal your land. With an ever-growing population from grain-based agriculture, they will quickly fill your land with their ever-growing population of farmer slaves. If you say yes, you get assimilated and enslaved. If you run, you will have conflict with your neighbors, and if the expansion continues it will eventually reach you anyway.

Growing up as an American, I received a flawed, inborn understanding of how the rest of the world works. I grew up here, with electricity twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. I grew up with television, telephones, and sports cars. I grew up with McDonalds, the Gap, Hot Topic, and so forth. With democracy, free speech, freedom of religion. My point: although we live as wage slaves and slaves to this culture, we live in the richest country in the world. Slaves…with a lot of money. Money in this instance translates to “rights.” We have a lot of “rights” in America because we can afford to buy them from our masters (temporarily of course). This gives most Americans the illusion of the power of personal change through making the change in their own lives. They have the luxury (and delusion) of “buying green.” They have the luxury of time and money to invest in their home permaculture gardens. Who else in the world has time or money or access to educational resources to do that? Maybe a few other first world countries, but not the majority of enslaved peoples.

I find it funny when I hear people say that our problems occur because people don’t take personal responsibility. Blame the person, not the culture, not the system of wealth management and the armies that enforce it. Since climate change threatens us all, does that mean that a slave-child sewing soccer balls in Taiwan has a personal responsibility to stop climate change? Do you think the slaves in the third world have a personal responsibility to stop climate change? Do you honestly think they have the power? Where they can’t even afford to buy “rights”? Do you honestly think us more privileged Americans do?

Of course, when most people I know speak of personal responsibility, their words carry an unspoken premise that means they don’t try to stop corporations from creating fucked-up products and forcing people to buy them, but instead figure out ways in which they can learn to live without the fucked-up products or buy expensive “green” products. This ignores the entire system of how empire exerts its power. I have the wealth to buy organic vegetables and free-range meats. Although I pay rent, I have enough time and money to plant a garden and build a humanure composting system. But what about your average American wage slaver with two jobs and a family to feed? They shop at Walmart because they can’t afford anything else. The majority of people around the world cannot afford personal change, and those in power do not allow it anyway. Sure, they still have a responsibility to stop corporations and those in power from killing the land, because they live on this planet. But the idea of personal change making a difference comes from privileged people with money.

Since personal change requires money, it can’t work because the masses can’t afford it. It also takes accountability away from corporations and the military, police, and legal systems that protect them. Since those with money and power don’t want to lose that money and power, they have no interest in changing this system.

The overwhelming majority of hunter-gatherers had egalitarian cultures. Sometimes they had hierarchical cultures, but without slavery—sometimes with what anthropologists have labeled as slavery, but not quite the same. Regardless, they had, and still have today where they have not experienced genocide, nonhierarchical social structures based on cooperation rather than competition.

In the wild, competition among plants and animals happens rarely, and usually only during times of scarcity. Within agricultural communities, we see wealth funneled away from the majority towards the few rich people. If you have to give 10% or more of your own food supply, 10% you had to toil in the soil for, your own food becomes scarce. If you destroy the soil using agriculture and ruin your landbase, of course you’ll have scarce resources. This fear of constant scarcity leads to intense competition. If people have lived on earth for more than three million years (as the archeological record shows), we can assume that they have lived in a cooperative system for the most part, and that those who didn’t, didn’t stand the test of time. Even though civilizations seem to outcompete hunter-gatherers during their peak, they don’t last in the long run.

A rather large emphasis sits on creating nonhierarchical social models in rewilding. As long as empire exists, civilization will persist because those who sit atop the pyramid will continue to enslave us. Because agriculture lies at the heart of civilization’s destructiveness, and because empire only becomes possible through grain-fueled population growth, empire will never stop using agriculture. Even if everyone went “green,” empire would not, could not, stop destroying the soil. When people advocate for a sustainable civilization (which cannot exist), they generally don’t realize that means they simultaneously advocate for the continuation of empire, of slavery. This happens because they haven’t ever articulated what civilization actually means, nor how civilizations function ecologically or socially. It seems safe to assume that if someone talks about sustainability without talking about dismantling civilization and rewilding, they haven’t made this articulation either.

We cannot rewild as long as empire exists. Those in power will continue destroying the world whether we help them or not, and they will continue to do so backed by million-men armies (and soon robot armies—seriously, youtube that shit), nuclear weapons, and a brain-washed slave class. The end of empire will happen whether or not we encourage its end. When the oil runs out, when the soil turns to salt, we will see the end of empire. Unfortunately we will also see the end of countless species, including possibly our own. We must do what we can to dismantle empire if we wish to rewild, if we wish to save some semblance of life here on this planet.

English vs. Rewilding

Modern English language quite literally comes from no place. No indigenous people spoke or speak it. It works as a conglomeration of languages, a mishmash made for one purpose: trade. If languages provide us with a context with which to perceive the world, then English programs people to see the living world through the lens of exploitation: trees as dollar bills, animals as units of meat, humans as slaves. English tells us from the moment we utter our first word to our last that the world exists for one purpose: commerce.

By now you may have noticed something weird or different about my writing style that you can’t quite put your finger on. I’ll let you in on a little secret. I’ve written this book in E-Prime (or English Prime), a version of the English language that excludes the use of the verb “to be.” You heard me right. I do not use is, was, am, were, be, been, are, or any of their contractions. Stop for a second and write a paragraph or two or three and see if you can write without using “to be.” Pretty hard, huh? Now just think how hard it would feel to write a whole book in it!

E-Prime came about because some very clever scientists realized that B-English (“regular” English, which does not exclude “to be”) creates a false projection of reality. The world constantly changes, and B-English interferes with this change by attempting to fix reality in stone. It seems only natural that a sedentary culture that resists change would eventually evolve a language that projects our perception of control into the natural world. We do it with the plow, and we do it with our words.

While doing who knows what kind of experiments, these nerds discovered that an electron, when measured with one instrument, appears as a wave and when measured with a different instrument appears as a particle. We have a problem here: in Aristotelian B-English, an electron cannot “be” both a particle and a wave, as surely as a table cannot also “be” a chair. He realized that by “be-ing,” we label something as it “is,” fixing it into an unchangeable object.

For example, I cannot simultaneously “be” both stupid and smart. But what happens when Person A observes with a set of instruments (Person A’s senses) that I have intelligence, and Person B observes through a different set of instruments (Person B’s senses) that I say idiotic things? Our linguistic world eats itself, and arguments ensue. “To be” prevents us from experiencing a shared reality—something we need in order to communicate in a sane way. If someone sees something differently from another, our language prevents us from acknowledging the other’s point of view by limiting our perception to fixed states. For example, if I say “Star Wars is a shitty movie,” and my friend says, “Star Wars is not a shitty movie!” We have no shared reality, for in our language, truth lies in only one of our statements, and we can forever argue these truths until one of us writes a book and has more authority than the other. If on the other hand I say, “I hated Star Wars,” I state my opinion as observed through my own senses. I state a more accurate reality by not claiming that Star Wars “is” anything, as it could “be” anything to anyone. Similarly one could say, “I’ve seen Urban Scout act like an idiot before,” while another person could say, “Man, Urban Scout has really made me think. I really appreciate him.” We have two perceptions that do not contradict one another but that came about from different perspectives.

“To be” plays god. It attempts to chisel reality in stone and works as the backbone of the civilized paradigm. Of course it does: its birthplace lies in the land of economic commerce, not a biological community. English works to domesticate the world as much as tilling means to domesticate it. Every element of our culture urges for domestication, for slavery. If language shapes how we perceive the world, nothing stands more fundamental (aside from the practice of agriculture itself) to this process of domestication than our own language.

Some people believe that language marked the beginning of hierarchy and we should walk away from language as well. But where do you draw the line? At vocalization? Birds vocalize. Body language? Every animal uses body language. Every animal has a language. If I run from a bear it will chase me. If I stand my ground and avoid eye contact, I let the bear know I don’t mean harm. The bear will huff and gruff and bluff to test my stance. Eventually the bear will walk away and let me go. This confrontation has a language to it. Peaceful confrontations do as well. Birds use songs, companion calls, and alarms to communicate, to emphasize their body language.

We know that indigenous peoples lived sustainably with beautiful, poetic spoken languages. We also know that no indigenous cultures used the verb “to be.” Knowing that, and understanding what “to be” does to our perception of reality, it makes sense that the first step to rewilding the English language should involve eliminating Aristotle’s mistake. Willem Larsen has taken this concept much further and created “E-Primitive,” a version of E-Prime that stresses verb-based sentences (among many other changes). Most indigenous languages based themselves in verbs rather than nouns. This shows us their focus on a fluid, ever-changing perception of reality. Our noun-based sentence structure shows us another symptom of our fixed-reality language.

E-Prime hardly fixes English (pardon the pun!). But it greatly defangs it. It tears down many of the language’s footholds on control and allows for a more chaotic, changeable paradigm to fall into place. The more I write in E-Prime the more I see how “is” takes control of the world and how fluid English can sound. Of course, I speak B-English and use it in most of my other writings. I also have no illusions that E-Prime could ever stop civilization from destroying the planet. Rather, E-Prime works as a means of reconnecting myself to the wild through language. It merely helps me to see the world through a more dynamic, accurate linguistic paradigm.

Stockpiling vs. Rewilding

Hey there Scout,

I am just wondering that, while you are honing your skills to be able to create new out of the aftermath of civilization while nature is still intact, what are your thoughts about what to gather from this world (i.e. ropes, tarps, rations, guns) to facilitate survival during whatever happens whenever it happens. haha the future is so wonderfully vague but extremely heavy if you have the proper amount of imagination and paranoia! also do you have a place to escape to, do you think this is necessary? a plan on how to get there undetected, other people to join? i am working on all of these problems right now but my energy and focus rise and fall like the sun and that quickly and if its a nice day outside you can guarantee i am not focusing on the warm weather clothing and wool blankets i will need stowed, mostly working on my tan (vitamin d), muscles and ability to become nature as to remain undetectable. but i know there are things that are extremely important that will insure that the people with the right intentions for nature and the universe can prevail and that we should have these at the ready just in case anything happens. its funny because i have gone to some “survival” website with lists about what to have, they will list “at least a half gallon of water per day per individual, which does not provide water for hygiene, so be sure to take breath mints and STRONG DEODORANT” seriously these people are worried about “hygiene” and its the Apocalypse?!?!? i guess if they weren’t intending to survive on MRES, which are sure to putrefy their systems, they wouldn’t smell so foul but come on, if you even wear deodorant right now i am pretty sure you have a special comet with your name on it hurling towards the earth this second.

I don’t know how well to say thanks but keep exploring and sharing,

Jessica

Hey Jessica,

Thanks for your questions! (And I appreciate your sense of humor.) I’m sure you can imagine I get questions like these fairly often. What supplies should I have for the SHTF (shit-hits-the-fan) scenario? Unfortunately most people hate my response…because I’m not really one of the SHTF people…

While you are honing your skills to be able to create new out of the aftermath of civilization while nature is still intact.

I’d like to say first and foremost that I don’t think of myself as honing my skills to have the abilities to create new out of the aftermath of civilization; rather, I work on creating a new world to live in right now because I don’t like this one. I would do this work even if I didn’t think of civilization as collapsing. Which I’d also like to say, started a long time ago. If we see that civilization has already started collapsing, we can start to see that collapse does not happen overnight, but rather like a slow and ugly death.

What will it take for people to fight back against civilization’s destruction of the planet? When the salmon no longer swim upriver to spawn? When the polar bears no longer walk through the snow? I like to think of the SHTF scenario in the same way. How do you define your personal “shit”? When the salmon go, does that represent the shit hitting the fan? When the ice caps melt? etc.

Collapse works as a process, not an event. We can mark its progress by larger events, but the process itself happens rather slowly and painfully, depending on your addictions to civilization. I don’t mean to say that fucked-up events that happen as a result of collapse can’t happen overnight. Obviously tipping points (bigger pieces of “shit”) exist in various systems, like the economy and the environment, and can bring about quick changes.

What are your thoughts about what to gather from this world (i.e. ropes, tarps, rations, guns) to facilitate survival during whatever happens whenever it happens.