William Gillis

How and why Jason Godesky is so wrong his ancestors are wrong

You wake up. The morning light streams through your bedroom curtains. It reaches your eyes, but you don’t really see it. Instead you stumble down a hallway and into the shower; hands automatically reaching for knobs. Breakfast is a chore. The kitchen is a fog of blunt interrelating abstractions. Get the cereal, get the bowl, get the spoon. When you arrive at the bus stop your eyes have accumulated to the light but the world still seems an overwhelming jumble compressed to a point. The watch on your arm ticks out seconds as your gaze plays duck-duck-goose with the blocky cars coming into view over the horizon. Part of your mind makes simple calculations regarding work or school, the social networks and the behavioral patterns. You grasp pieces of data you’ve isolated and then build structures out of them. Always step on the black tiles, eat the green M&Ms first, which TV shows to watch in what order, pick up your clothing at the drycleaners this afternoon, trade one friendship for another, call your mother this week, shave some time off the ride home by taking a new route. As these structures form in your mind the world around you seems distant and chaotic. You reduce and simplify, reduce and simplify, into items and parts. Tree, anthill, cracking sidewalk, fence, lawn. Simple structures to tame the teeming chaos around you. But the image feels fuzzy, the structures in your mind too sharp, and you feel abstracted, separated, withdrawn. A creaking zombie in the morning rush hour, hunkered down into yourself. Suddenly

Contact.

You turn a corner on the inside of your head and your mind rushes outwards. The warm stream of sunlight that’s pouring into your eyes stops crashing up against a barrier and connects. Infinite causal lines of photons bounce at odd angles off blades of grass, hanging dew and rusted metal… and connect you to them all. The wind wisps against the hairs on your arm carrying the ripples and eddies of the wind patterns. The sound of tree branches interplaying with turbulence from the highway, updrafts from the river, convection from the oceans, and the Earth’s Coriolis force. You don’t give any of it names of course–you’ve stopped thinking in terms of something as simplistic as language–the structures and routines you had been cranking through fall away like chains and crutches. The stimuli crashing around you has been transformed into touch. Suddenly freed of your awkward internal machinery you can finally reach out. The desire comes to dance, to explore, to stroke the surface of a tree, to climb the fence and howl into the wind, to examine the colors of rusty paint flaking off the bus sign, to play, to imagine, to build, to roll in the leaves with a stranger, to hug a friend, to leap onto the back bumper of a passing car and ride it down the traffic surf, to love, to turn up the music playing on a radio and delight in the seething social interplay it carries, to heal, to paint, to travel, to skip, to jump on Wikipedia and learn about new knitting trends in Taiwan, to cloud-gaze, to run as far as you can, to do what has never been done before. The bus comes. Machinery beckons. Shattered but not entirely broken frameworks begin to reform in your mind. You have the option of wanting to get to work on time. You have the option of paying attention to your stomach’s growls. The quickest route to food is on the way to work. You choose the easiest road. You get on the bus.

There is a reality behind the fluidity and rigidity of your thoughts. Thought processes that are repeated over and over again cause the neurons along these connections to lock themselves into place. They become circuits and filter out everything that doesn’t drive them. These extended structures interact with one another in amazing ways to form cultural traditions and social hierarchies. Governments and ideologies. Like all other processes they are technologies, structures that we use to deal with the world. But more specifically they are structures that have largely solidified into their lowest energy state. All the showy expressions of social psychosis that we know and love (power, greed, etc) are ultimately the result of laziness. Personal disengagement and surrender to the easiest path. The easiest pathways.

And insofar as we embrace this abstinence from thought we begin to behave like predictable machines. Nations follow set patterns that are easily analyzable. Cultures, religions, mobs, slaves, kings. The more rigidly they are framed in their social ecosystems the simpler and more consistently they act.

The same is true with their physical environments. In fact material structures and realities often play a crucial role in determining the behavior and composition of social structures. The inverse, of course, is also true. Just as a regional drought can drive a band of nomads to unthinkable brutality or deaf ears restrict the social interactions possible an old man, so to will a kingdom clear a forest to eradicate opportunities for secession or an expanding corporation lay steel and asphalt lines across migration routes.

But nevertheless there are moments in our conflicted lives when we break through. In which we glimpse life beyond the simplifications and abstractions that alienate and domesticate us. Moments that drag out into expressions of originality, creativity and compassion. Such moments, such states of being, cannot be imposed and are thus their effects are rarely seen in the grandiose interplay of macroscopic causal structures. Vast mechanisms of negative feedback have developed sustaining the largest structures and would suppress the uncontrollable chaos of our empathy and creativity. Those of our shared psychoses that have survived and flourished have done so by adapting techniques for marginalizing and stifling the wildness of our consciousness, of our conscience. For its spontaneity and fluidity threatens to wash their brittle corpses away. These structures are social and psychological. But their strongest support stems from rigidities currently innate to our interaction with the physical world.

This is where we begin.

When I started putting together the 15 Anti-Primitivist Theses[1]—now frequently referred to as “post-primitivist” by several friends—I adamantly refused to break them into separate cases or arguments. Although individually they do mirror certain perennial objections (“what about science!” “small societies suck!” “we’ll invent new solutions!” “what about the liberating joy of spamming metafilter!”), the point was to show how they weave together as a whole critique. Or at least to root them in a deeper understanding of the systems primitivism seeks to address. And, of course, that’s what this is all about.

Although the primitivist movement provides outrageous strawmen in abundance there was a reason I chose to target my first thesis at something as innocuous as the premises and constructs of Biology rather than say, the whole killing 6.5 Billion people thing. You see, although I was inspired by Jason Godesky’s Thirty Theses[2], I didn’t want to chain my critique of primitivism to a breakdown of his specific fallacies. Primitivism is a big umbrella and, as I said, the point was to address trends, tendencies and mistakes endemic across the entire discourse. That said, I knew I’d have to address his framework specifically. So I allowed myself a conceit. I chose the first thesis to subtly annihilate the foundation of his framework with almost exasperating specificity so I would then be free to spend the rest of the theses building off a more deeply rooted systems analysis that was not couched in arbitrary taxonomy.

Biology’s discourse has been historically reliant on creating simple, rigid abstractions of hugely dynamic realities. Labels. Parts. This is a bone. This is a heart. This is a dog, this is a cat. We do this because it’s useful, because it’s a very functional way of dealing with the world. In fact the human mind is built to do such things. This is, after all, how civilization got started. How language and symbolic logic got started. It’s a shortcut in the processes of evolution. Instead of depending on our hardwired senses to jolt our hand back each time it strays into the flame, we actively form an internal impression of “flame” from trends in our sensations. Instead of actually going through physical trial and error we are able to construct models in our minds and then use them as practice to guide our actions. (The social conveyance of such abstract structures became language.) It’s a great way to cheat at evolution. We don’t need to slowly develop a gene that provides us with an instinctive behavioral process of converting carbon and oxygen into carbon dioxide for heat during the cold winters. We teach one another the abstract structures. The processes behind gathering firewood and lighting the kindling.

And they’re very useful. Very pragmatic in securing the survival and propagation of certain informational structures. But not very good at conveying the underlying realities of our world.

Biology has always been very wrapped up in the perspectives and interests of our social constructs, of our memetic context. And thus, although it sought to create a framework with which to understand the world around us, it did so from the top down. It created its abstractions, its structures, first and then divided them up into finer parts. Of course, in many ways this process has been responsive to the realities of what it was studying, but its overarching abstract structures and broad analyses inherit a disturbing legacy of detachment from underlying realities. As do those fields inspired and launched in conjunction with—and thanks to—Biology’s discourse on human machinery. …That is to say Social “Science.”

Fields and discourses like Anthropology or Economics may utilize processes of engagement superficially similar to the processes of trial and error seen in Physics or Chemistry, but their approaches can differ wildly. Instead of starting with the roots, Biology and Social Science make their inferences between the interplay of preexisting macroscopic abstractions. In fact some go as far to declare that those abstractions they work with have an absolute reality unto themselves that supersedes their roots!! In such a perspective there are platonic ideals that magically spring into existence alongside certain macroscopic structures making a “bowl” for instance, “more than the sum of its parts.” As we’ve seen, epistemologically this can be a very useful trick, but ontologically it’s crap. Just because we can’t calculate the interrelations of every particle that comprises the simplification of “bowl,” doesn’t mean our shortcut has a reality unto itself. Or that our assumptions regarding the behavior said “bowl” are anything more than simplified abstractions.

Of course cereal bowls are rather rigid structures and behave rather simply, but hurricanes, brains and biospheres are not. Realities eclipsed by our simplified models can end up having massive effects. We all know that a small microscopic perturbation can radically alter a non-linear system’s macroscopic trends.

When addressing something like Primitivism the vastness of the subject material requires us to think about ways that systems evolve in overall behavior. Because we can’t even begin to address the infinite structural details at hand we have to make very wide inferences regarding the nature of things and how such natures influence the way they behave. —But this should ideally be done without depending on the structures of “discrete” sub-systems we inherited from top-down taxonomies. Otherwise our analysis will not only inherit the limitations of our original functional abstractions but then exacerbate them when broadly applied.

In the primitivist discourse we grasp around with terms like “technology” and “civilization” —and for good reason, the topic at hand requires such broad generalizations for us to deal with it. But when our generalizations depend on sketchy or hazy “common sense” abstractions we often find ourselves holding a can of worms. This is familiar to anyone who has ever dealt with primitivism. What constitutes Technology? What constitutes Civilization? Small differences in definition continue to spawn a thousand debates. Everyone has their own slightly different answer—usually depending largely upon their own linguistic experiences and accumulated feelings. Feelings are important, they’re vital to this whole rigmarole. We don’t know “Civilization” is bad. What we really have is a feeling that something is terribly wrong with our world. And we see connections, relationships, patterns and trends all around us that would strongly direct our instinctive allergic reaction towards certain agglomerate macroscopic abstractions we’ve created in our brains. “Civilization.”

We feel out the oppression, the machinery, the alienation all around us, we simplify and smush our feelings into preexisting conceptual structures we have, and then we go looking for the details. But the details, the specific structures and interactions are infinite. They’re almost impossible to tie down completely. So we do the best we can. Certainly a whole lot of folks spend a lot of time obsessing over the mechanisms behind stuff like peak oil and global warming these days. And, indeed, some of the inner workings of our rotten oppressive structures can be fleshed out rather easily. It’s relatively easy to create rough models of how we’re being oppressed. But a lot gets skimmed over in the process. And although it provides a better picture of the problem, it rarely gives us any information regarding the best answer.

Jason Godesky has a pretty good idea of how we’re getting screwed, and he has a good intuition regarding those structures’ probable future. But when it comes time for him to make broad inferences as to the nature of things he fails spectacularly. Which is why his answer to the woes of our civilization is ugly, blunt and militantly incompetent at best.

See, Godesky is something of a genius when it comes to collecting historical connections and patterns in human behavior. And because most of the specific inferences he pulls from them are true—and the few that are incomplete are still largely true—it provides him an extraordinary analytical structure.

Again, most of the specific arguments he presents closely follow the realities of our world: Our development of agriculture has, by its very nature, been a difficult, dangerous and unhealthy process. It has resulted from, paralleled, and facilitated the development of brittle sociological hierarchies. As well as an unrelenting swarm of exponentially compounding and extending cultural structures. The aggregate system of all of these structures in many ways depends critically upon its own exponential propagation and is thus primed for catastrophic collapse.

This much is undeniable. Unfortunately Godesky goes beyond simply recognizing these practical realities and instead makes broad, unwieldy jumps in his attempt to weld them into an overarching understanding of human nature. He clings to macroscopic abstractions that, while functionally useful in their original common sense context are ultimately inapplicable to anything deeper. He builds a framework out of the patterns he correctly identifies and the abstractions he misapplies and then uses this framework to drive his hidden personal idealism. (That is to say “realism”: An assertion that we are and should be causal machines with no real agency to make the world a better place, ultimately governed and programmed by the input of our surroundings according to the exact framework he has ‘discovered.’ Ultimately incapable of choice in anything of importance.)

But beyond being morally repulsive in the extreme and utterly irreconcilable with anarchism much less anarchy, his framework denies nuances to our given systems, overlooks critical realities behind the creation and “progression” of technologies, ignores the root conditions that prompt the development of civilization and overt subjugation, comically misinterprets the social and ethical ramifications of limited human neural processing capacity, simply fails to comprehend the nature and realities of the universe beyond Earth, and is generally incoherent.

I wish I could say he makes one central mistake, but his willful ideology and subconscious alienation from humanity is endemic throughout, littering the 30 Theses with separate subtle disasters. Nevertheless there is a singular catastrophe that has remained a particularly glaring error in Godesky’s work since the day he published his first Thesis—one that as previously mentioned—I passingly attacked with my first Thesis on the taxonomy (and historical fascism) rife in Biology. This catastrophe is his direct and shocking dependence upon two macroscopic abstractions he would universalize as fundamentals regarding the underlying nature of systems: “Complexity” and “Diversity.”

Unfortunately these interrelated abstractions depend critically upon top-down taxonomy and are easily shown meaningless. Godesky has laid his foundations in quicksand.

Diversity, most obviously depends directly on taxonomy. You can’t begin to determine how “diverse” a set of abstractions is without first imposing a set of labels on them. You have to impose a taxonomy before you can measure diversity. Green box. Red box. Red box. Red box. Hesperotettix viridis pratensis. Hesperotettix speciosus. Melanoplus confusus. Melanoplus differentialis.

Is the abstraction of object A different than the abstraction of object B? How much so?

Even if you try something as ridiculously blunt as say counting the ‘convergent’ nucleotides between DNA-ish strands in our biosphere’s semi-distinct water sacks, you’re still left with a ridiculous metric.

Of course, in everyday use our references to “diversity” is perfectly legit. Useful. Vital. But such taxonomies are social constructs. They’re about functional use in relation to us. They are not grounded in nature. Is object A objectively different than object B? Of course they are. Everything is equally different, equally “diverse.”

Ultimately the universe is just as diverse today as it was 13 billion years ago. The only difference between the positional information of particles today and 13 billion years ago is that we’re closer to the positional structures around today and—being more immediately familiar with them—have more names for them. Energy may have granulated in the big bang and particles may have reduced into less and less energetic molecular structures and collections. But such granulation into what we’re used to dealing with today doesn’t change the fact that such asymmetries in distribution were already there. Just more closely concentrated. By any objective metric, whatever absolute “diversity” there might be in the universes’ matter has remained a constant since the beginning. And the same is true in our biosphere. The only measuring sticks we might apply to it are going to be centered around us, our pragmatic needs, and our present moment in time. So “diversity” really isn’t useful or even relevant when applied as a broad abstraction regarding the core realties surrounding our civilization.

Godesky has this wonderful passage central to his very first thesis that I feel like I really shouldn’t quote because it’d just be plain mean, but it gives me the giggles every time I read it and I’m not above sharing:

“From a single, undifferentiated point of energy, the universe unfolded into hundreds of elements, millions of compounds, swirling galaxies and complexity beyond human comprehension. The universe has not simply become more complex; that is simply a side-effect of its drive towards greater diversity.

So, too, with evolution. We often speak of evolution couched in terms of progress and increasing complexity. There is, however, a baseline of simplicity. From there, diversity moves in all directions. If evolution inspired complexity, then all life would be multi-celled organisms of far greater complexity than us. Instead, most organisms are one-celled, simple bacteria–yet, staggeringly diverse. As organisms become more complex, they become less common. The graph is not a line moving upwards–it is a point expanding in all directions save one, where it is confined to a baseline of simplicity. From our perspective, we can mistake it for “progress” towards some complex goal, but this is an illusion. Evolution is about diversity.

Physics and biology speak in unison on this point; if there are gods, then the one thing they have always, consistently created is diversity. No two galaxies quite alike; no two stars in those galaxies quite alike; no two worlds orbiting those stars quite alike; no two species on those worlds quite alike; no two individuals in those species quite alike; no two cells in those individuals quite alike; no two molecules in those cells quite alike; no two atoms in those molecules quite alike. That is the pre-eminent truth of our world. That is the one bit of divine will that cannot be argued, because it is not mediated by any human author. It is all around us, etched in every living thing, every atom of our universe. The primacy of diversity is undeniable.”

Our taxonomies of our world get more diverse throughout history as it gets closer to us?! Woah! No way, man!

My immature sarcasm aside, this painfully ignorant passage is a harbinger of worse things to come because he fuses it with a utilitarian interpretation of “ethics” to begin his journey with the assertion that diversity is a moral good. With his moral system thus grounded in something deeply arbitrary and entirely subject to the social constructs of our current civilization, Godesky goes on to make a bunch of proclamations regarding the ideal nature, place, framework and role for humans in the world. These are generally broad, clunky generalizations with horrid implications, but they’re nowhere near as bad as his second major conceit: “complexity.”

Now, traditionally “complex” systems are recognized as such by the presence of two things: a high degree of non-linear movement & a huge number of component “parts.” (One of those concepts is entirely subjective and dependent on arbitrary constructs while the other is actually indicative of an objective underlying reality. Guess which.)

Complexity theory is an outgrowth or alternate face of chaos theory. It’s usually invoked when one is studying the interrelating substrata that make up a pre-established abstraction. The ant hill. The hurricane. Although such abstractions appear to behave rather simply and cohesively “on the whole,” when it comes time to extend our taxonomies a little deeper we tend to find the behavior of such component “parts” incredibly complicated. And yet the overall shape of our abstraction still maintains some functionality in our minds even when the root reality is one of constant turbulent change. Thus the system is said to be “complex” or display “complexity.” This is a very useful abstraction among the more social “sciences” because it allows one to borrow insights and make metaphorical inferences between systems we would normally think of as very different. For instance market strategists might compare a firm’s organizational strategies with the interrelating behavior seen in plants to gage its adaptability.

Complexity is really just a bundle of tools used to analyze the interaction of information structures. Not in the sense of imposed-from-above taxonomies, but in the sense of aggregate positional structures. If you have a collection of interrelating particles moving about and interacting which low-energy associations are going to persist. Evolution and Darwinian survival. How will they react to certain conditions? And what similarities will we find between structures that have survived and propagated? The adaptive, changing patterns that emerge out of non-linear systems are actually pretty easy to understand and predict. It’s just positional information swirling around in feedback loops. When you’re looking at things from the ground up, complex systems make perfect sense. The universe is just randomly distributed particles spinning down into their lowest energy state in relation to one another. This gives rise to stars as dust collapses together and various molecular structures as atoms find ways to snuggle closer. Organic muck settles into little whirlwinds of extended chemical reactions. Etc, etc. Soon we’re trading Pokemon cards and making little online ecosystems of metahumored webcomics.

Now, one of the metaphorical realities in complexity’s toolbox is a thing called Diminishing Returns. It’s a concept historically rooted in economics, but the distinction is of course irrelevant. If a structure is dependent on a rigid process of interaction with external realities there will come a point where those external realities cease facilitating that process as well as they had previously. That’s just a universal basic reality.

Foxes multiply until the rabbit supply stops being conducive to making more foxes. Each bushel of seed a farmer buys to plant generates a directly proportional increase of crops until he’s completely covered his land. This usually isn’t a catastrophic problem. But if the foxes are horny buggers and keep buggering each other and competing viciously for rabbits even as they starve to death then there ain’t gonna be all too many foxes left come spring. If the farmer’s a dolt and keeps spending all the cash he’s got on seeds then not only will he fail to recoup his expenditures, but any sudden turn of events could lose him the farm.

This, quite obviously, has a fair bit of relevance with respect to our civilization.

The problem is Godesky wants to declare that increases in “complexity” itself are subject to diminishing returns. In other words, making a system more and more complex requires more and more energy… until one reaches the point where making the smallest increase in the system’s “degree of complexity” requires a near-infinite amount of energy.

He’s not the first to speak of increases in a system’s “complexity”, but note that his use is singular amid all the other social “scientists” who’ve strayed into such language because he wants to derive a fundamental, universal, core principle from it.

Of course, on the surface, Godesky’s thesis suffices a cursory comparison to the realities of our civilization. The more “complex” an industry’s process, the more obviously awkward, clunky, and likely to fail it tends to be. Right? But his implied definition flounders under deeper scrutiny. Who’s to say that the processes of turning trees into toothpicks is less “complex” than the processes of an aborigine’s hunt?! Certainly we give more names and express more symbolic logic relating to toothpick manufacturing, but it seems unrealistic to state that the vast network of interrelations between the hunter and her environment is less “complex.”

So what exactly does Godesky mean by “more complex”?

Complex systems are rarely compared to one another with such measurement in mind. Complexity is usually an analytical tool, not a metric. To say that a system is “complex” is just to say that it fits the general conditions we built Complexity Theory to study.

But obviously that isn’t what Godesky’s getting at. In order for Diminishing Returns to apply he needs an objectively definable vector of development that can be progressively hindered as it is arbitrarily increased. As mentioned there are two main markers which we typically use to identify complex systems: non-linearity and a great many parts.

Godesky treats non-linearity as a binary—either a system has it or it doesn’t—whereas he appears to use the number of parts, components and other abstract conceptual subdivisions, to mark the resulting degree “complexity.”

But of course, if such socially expressed taxonomy is the basis of “part-hood,” it’s easy to see how we might sidestep Godesky’s declaration of diminishing returns. Just arbitrarily increase the amount of names and component processes we break something down into! It's easy to see that any established conceptual system can be made more and more “complex” on an arbitrary whim with no cost whatsoever. To give an everyday example, consider the indie-rock snob who consciously creates more and more vast systems of taxonomic compartmentalization in a given subject at little or no inherent cost. Given a finite amount of music the snob can arbitrarily increase the number component parts and interrelations by which he mentally or socially addresses such.

One needs only take a existing macroscopic abstraction and then break it down into progressively smaller interrelating components. Consider every word in the English language, now split those words in two in your brain. (Perhaps make version A more emphatic than version B.) Do it again. Do it again. You can do such infinitely at no cost whatsoever. I can, for example, assign the numbers between 1 and 10 in front of each word to indicate emphasis or degree… or 1 and 1000, to 10^6 decimal places, or whatever. No sweat. No energy whatsoever.

(Better yet, I can even—if we’re feeling particularly anal—mess with basic verb/noun grammar and other structural details in my language step by step until it becomes such a non-linear system that it perfectly connects with the fluid realities around us without sharp informational degradation.)

You see, taxonomies are subject to Zeno’s Paradox. They can, to use Godesky’s definition, be made arbitrarily ‘complex.’ Consisting of an arbitrary degree of component relations. We can even dissolve our abstract simplifications and see the world for what it is. Feeling out an infinite number of direct interrelations from an infinite number of what might be construed as “fundamental parts” with our mind. The hunter feeling the wind rustle through the trees.

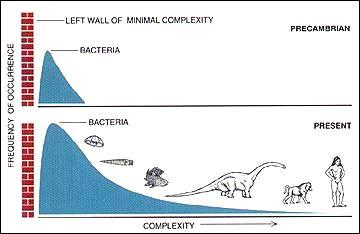

There’s this wonderful graph Godesky cites, displaying the “complexity” of species and its “frequency of occurrence” in history. Now, ignoring the fact that dividing our biosphere up into discrete “creatures” is an imposed social construct with no real grounding—especially as it moves towards the prokaryote world—there is an underlying reality he’s getting at. Namely that a dynamic ecosystem will support many more small rigidities than large, extended ones. But the graph contains a particularly loopy error. One that perfectly exemplifies how arbitrary his metric would be. It places the dinosaur at a lower degree of complexity than the monkey! The reason for this irrationality is simple: our taxonomies are centered around ourselves. We have more names for the inner workings, parts and processes of systems closer to our own experience.

If the monkey seems more complex than the dinosaur, it’s because it possesses neurological (and thus behavioral) structures that we place greater taxonomic importance on. Not only does the monkey raise its young according to inherited and socially transmitted informational structures, it builds “discrete tools” that we can easily label. It’s life mirrors our own and so we have a greater number of everyday “components” at hand to apply to our abstractions regarding its life. But we could easily change things up and apply the same number of parts to the dinosaur. In fact, given the greater amount of interrelating particles and structures comprising it, we could easily consider the dinosaur “more complex” than the tiny monkey.

Similarly, coral has more genes—arranged in more complicated inter-relations—than the homo sapiens baseline, and furthermore constitute far greater net biomass. Yet they are relegated to the back of the graph mainly because we don’t give a shit about coral. It’s all one relatively simple, amorphous blob to us. Yet a specialist would make the case that coral is incredibly “complex,” a property that—very much to the contrary of Godesky’s thesis—has aided it in triumphing and flourishing across the Earth’s oceans in greater complex aggregates.

Extending further from our everyday vantage point we might turn our attention to the stars themselves. Rather resilient patterns of negative feedback manage to sustain a system comprised of billions of particles interrelating in a very non-linear fashion. And, in their death, they furnish the later creation of later children. So obviously there’s no relevant upward limit on the possible “complexity” of material systems.

Of course, the real distinction we instinctively cling to is that the monkey and the human inherit and transmit neurological/behavioral information socially. And while the dinosaur’s environment and society will likewise result in the building of neurological structures, the monkey’s survival is more critically dependent upon the integrity of these socially maintained information structures. (The dinosaur’s survival, by nature of its biomass, is, however, dependent on a greater expanse of structures. Same with the star and the coral, although the structures they depend on are considerably less rigid.)

You see, the issue at hand that Godesky hazily grasps at with his use of “complexity” is the overextension of rigid structures. Particularly, rigid structures that are compounded upon one another.

Rigidity is critical. What makes diminishing returns applicable in the instances of horny foxes or simpleton farmers is the rigidity of the systems at hand. The horniness. The stupidity. Both the foxes and the farmer are relatively locked in to a certain set formula of behavior. The informational processes they represent within their environments are rigid. They don’t change, they don’t adapt, they don’t integrate or interrelate. And thus, their internal structures, their set programming—though it starts them off pretty smoothly in their initial environmental conditions—begins to flounder drastically as those conditions are changed relative to them.

The concepts I’m using—rigidity and fluidity—are very broad, but unlike Godesky’s talk of “diversity” or “complexity” they are well rooted and portray a more nuanced picture.

Fluidity (often referred to as Dynamicism) is a critical concept in the Fifteen Anti-Primitivist Theses. And it’s a wonderful gage in systems analysis because relative changes in position between particles (per unit time) is a real metric. You can tell a lot about a system’s behavior from the way it's composed. Brittleness, malleability, plasticity, adaptivity, extension, overly-dependent rigidities, spontaneous collapse over the chaotic edge… These concepts represent objective realities that we can analyze.

You see, non-linearity isn’t a binary. Everything is non-linear. But there are different degrees of relative non-linear interaction. Things can be strongly bound locally into relative immobility. Or they can play out their interactions in relative interrelating motion.

More fluid—more non-linear—systems exhibit a certain stability and evolutionary advantage over the linearly extended constructs forcibly built out of them. We live in a very dynamic, fluid world and systems that are built with far less capacity for fluid interrelation than the environment around them tend to face nasty problems. We suddenly slap concrete over the Earth’s surface and expect to get away with it. We build little cages with our minds and shop around for larger shackles. Make no bones about it, our intricate gridwork of chains is doomed. Godesky is right to urge urge others to adapt and start splashing around rather than cling to a dying leviathan.

So okay, yeah, his conceptual approach is a wee bit sloppy in language, but does this more rooted and nuanced approach really alter any of his basic conclusions?

Oh, hell yes.

Let’s first take a look at the act of invention. Of ingenuity.

Now obviously our industrial civilization labors pretty harshly under the same handicap of the simpleton farmer and the horny foxes. We’re pretty ingrained in our established structures and methods. A billion tons of steel automobile frames would seem to make that pretty clear.

Adaptation is costly to rigidity; the system doesn’t like to change. It wants to preserve itself as it is. In that sense our civilization is actually inherently resistive to invention, to imagination and ingenuity. Sure it needs small amounts of development in very tightly directed vectors in order to keep the processes of its exponential expansion from faltering. But to do that it needs control over the minds, it needs to resist creativity. And to contain and direct that which is left. Because left to herself the inventor/artist/scientist would frolic in fields, she would create and dissolve the structures around her in ways uncheckable. An element of potentially catastrophic effect upon that which seeks to remain only to remain. Her desire for touch, for contact, for truth is ultimately corrosive to the chains, the walls and lies of such mechanism.

Because to touch is to invent new channels of sensation. The dissolution of previous constructs. To adapt, to re-form around realities, the system must first be made more fluid. Though the creator may build and shape new structures, the driving force behind her creation is the desire for contact, and so the structures she creates have no value in themselves for her. And she will not inherently sustain them. Thus her creativity is a threat to the maintenance of structure.

The problem with our civilization is that it impedes dynamic thought and action. In other words, the problem with our civilization is that it isn’t inventive enough.

Now Godesky would love to assert that creation is a laborious structural process. That it requires energy invested in a mechanism of development. In short, that the creative process is a quantifiable machine subject to simple deterministic economic rules. That it takes far more energy to make “advanced” developments than initial ones. The prototypical situation would be learning English and then making more and more “complex” constructs out of it. You have to put together all the base structural elements before crafting the larger structures out of them.

In our brief dialog the example Godesky gives is Einstein’s Relativity. The idea is that in order to understand the realities of Einstein’s theories one must first build Newtonian constructs in one’s brain and before that certain shared basic linguistic constructs..

As it happens this is a particularly delicious example because it beautifully showcases the vast multitude of ways his perspective is wrong.

1. Einstein’s framework ultimately replaced rather than built on top of Newton’s. The historical progression is irrelevant. What Einstein was really doing was dissolving Newton’s framework and reassembling a new one. Einstein broke things down to get at the roots and then built details up again to more closely encapsulate them. We find it particularly useful to teach students along the lines of historical progression because our language on the subject was built according to that sequence, but the actual ideas, the actual concepts we’re trying to get those students to understand are not more a complex, more finely detailed, new layer of cards built on top of Newton’s house. But a completely different structure.

2. Einstein’s advances were much bigger than Newton’s. Newton spent his entire life detailing out structural frameworks and invested a HUGE amount of energy in it, which gradually worked out into a bunch of little advances. Einstein invested a relatively inconsequential amount of energy—but was willing and able to shrug off existing structures and think more fluidly—and thus he made a bunch of greater advances for less energy… centuries after Newton. Einstein, to both the perennial enthusiasm and annoyance of physicists, thought outside the box.

3. There’s no inherent reason Einstein’s conceptual breakthrough had to come after Newton’s structural work. The biggest thing Einstein had going for him that Newton didn’t was a shit tonne more data. More points of contact with the world. The popularity of Natural Philosophy had allowed centuries of experimentation to take place. Which Einstein pulled from rather heavily. (Needless to say I’m simplifying a bunch of stuff rather drastically but we’d extract the same basic realities if we were to turn our attention to a more appropriate example like Maxwell and the whole progression of electromagnetics.) Newton had a relatively small base of experimentation to pull from, Einstein’s world had seen centuries of mischievous fiddlers and explorers in strong communication with one another. A different society may have reached Einstein’s understanding differently and completely skipped Newton’s structures.

4. Language is just an arbitrary crutch. A stick we use to poke at inherent realities and showcase them to one another. It can be interchanged fluidly. You can, for instance, perfectly reproduce a fully functional, fully predictive, Physics based in a radically different “mathematics” that doesn’t use numbers. There’s no limitation to the weird ways one can grasp at and touch reality. The fluid of possible structures one can press around the world. You can have more than one, you can have an infinite number of systems fluidly describing the same thing. And, the more fluid they are, the less you face diminishing returns.

5. You can have Science on a deserted island. With enough points of contact with the world an individual could obtain Einstein’s understandings of the universe without ever utilizing socially transmitted structures. You don’t have to first invest energy in learning English/German/Pascal/whatever to understand as Einstein did. Those linguistic frameworks only serve as mediums to transmit basic waves of perceived relations. They’re useful in sharing impressions of contact. But ultimately not-necessary. And more often than not language gets in the way. The rigid structures utilized by society aren’t necessary or even conducive to ingenuity, but rather hindrances.

Understanding is dependent only on Contact.

In other words, our advanced “complex” concepts are not inherently based in the rigid, extended structures Godesky needs them to be in order for Diminishing Returns to be applicable.

This is also applicable to our “complex” technologies.

Rigidity confines thought and thus introduces diminishing returns because, like a house of cards once you’ve built the base there’s only so much you can build on top without it all crashing down. And you have to work harder and harder. But in a fluid society more is possible, things adapt and no rigid expanse threatens everything with catastrophe.

The problem isn’t everything we’ve developed with our civilization. It’s not even the civilization. The problem is the industry, the rigid massive processes and structures of our global system… not the WiFi routers or rhubarb pies in and of themselves.

In the 15, I pointed a difference between the processes that drive “development” today. A corporate PhD is driven by rigid profit motives and consequently such environments produce shoddy, dangerous, ultimately unstable products at great expense, with little original creation and extreme inefficiency. On the other hand there exists what we might blithely call the Open Source model. The feral thinker whose creativity is a matter of play. Far more efficient material developed far faster. And furthermore when our technologies are a product of such play, they by nature exist in a highly integrated, interrelated state.

Although this is instantly evident in the realm of the internet, software and the like, it’s also deeply applicable to matters of root industry. Things like growing food and even mining metals (or simply effectively maintaining and reusing what we already have) can be done with an almost infinitely greater degree of fluidity. There are plenty of examples to this end. Horticulture as opposed to Agriculture. Villages like Gaviotas and others demonstrate advanced forms of maintained technology. Windmills, Einstein refrigerators, and even planes. The details are as vast and complicated as our current civilization, yet so obviously solvable. African hunter-gatherers perfected iron harvesting and forging processes thousands of years ago. Building computers and other integrated circuitry will always be a complicated endeavor, but much of the rigidity and blunt, oppressive waste of our modern tech industries is a consequence of inefficient hierarchies and proprietary idiocy. There’s plenty of room for them given a revamped industrial ecosystem—and both the anarcho-syndicalists and the market anarchists have plenty of ingenious ideas stored up.

Godesky, very smartly and pragmatically, has long supported some of those technologies. Very few primitivists would dare speak of much less plot out how to build hot showers after the collapse! But nevertheless he defaults on borrowing heavily from the broad, blunt prejudice of Zerzan & Co.™ against anything that smacks of circuitry or advanced technological precepts—in other words the interconnectedness and immediacy provided by transportation and communications technologies. A few select examples to the contrary hardly temper his utterly un-nuanced and instinctive vilification of anything and everything to do with technological progress.

Godesky occasionally claims that progress is a myth, yet it’s a framework he instinctively holds to in a very rigid fashion; attacking and denying anything we’d generally consider “advanced”—by which he usually means “complex.” The latest points on the progressive march of our civilization.

But not all of our civilization has been built on rigidity. Much of what exists, much of the “advanced” world around us today, was created by fluid processes. Creativity abounds in our civilization. We’re still very adaptable and inventive. And a huge portion of our “advanced” world has been formed from the creative desire for contact.

Communication, transportation, and scientific understanding… these are in no way inherently tied to the structures of alienation that our society has developed to regulate and restrict them.

Godesky, like all primitivists, wants to argue that technology has an inherent and inescapable psychological effect, that it increasingly facilitates power structures and psychoses. But this is a misassociation stemming from his use of “complexity” as a metric to identify the more “advanced” forms of technology. Our developments in technology have been centrally motivated by the desire for contact, not an increase in extended rigid structures. Our civilization was built because we like to reach out into the world and touch more and more.

The social hierarchies and psychoses that our civilization has allowed to develop more explicitly are in fact fighting a progressively uphill battle against our increasingly fluid technologies. You see they—the hierarchies—are subject to diminishing returns. As technologies allow us to interrelate more and more freely—as they make society more and more non-linear—it becomes progressively harder and harder for the brittle power structures we know and hate to maintain their footing.

You see, in a certain sense, our Civilization has finally begun to seriously abolish the conditions that first prompted its development.

That is to say, we’re developing technologies that can finally start seriously satiating the desires that were responsible for this whole civilization mess in the first place. At least to the degree where we are no longer born inherently alienated from any part of humanity. Where we can stop pushing “others” off over the horizon and instead recognize our common humanity. Where we can stop reducing people into things.

Yes, our social structures expend exponentially increasing amounts of energy to compensate for the removal of our physical barriers by creating mental ones. By putting cops in people’s heads. But at the end of the day the thing keeping the Xanzou school girl trading text-messages about shopping rather than sexual revolution is just in her head.

And that’s a big deal.

Of course Godesky doesn’t believe that we’re capable of fighting that battle. He doesn’t believe we’re capable of the free will it would take to just turn off our cell phones whenever we feel like walking the beach in silence. He doesn’t believe we’re capable of the free will it would take to willingly throw off our global hierarchies… even if we were given the physical means. Although he might grant that we have some free will on small inconsequential matters, he absolutely cannot admit we might have free will on a large-scale societal level. Because that would trash his mechanistic portrayal of humanity.

And, yeah, okay, it’s true, on the whole we tend to act very mechanistically (ignoring some uppity outliers). But there’s something very interesting that he never covers in his mechanistic portrayal of humanity and the gears of our civilization: Why did Civilization get started in the first place?

What prompted it?

In everything else he claims we have no real freedom. But in this small matter he seems to grant us agency. Civilization was just this bad idea that we had. A misstep. The single, solitary act of free will that ever had large-scale effects. A poorly conceived project that is scheduled to finally fall apart. We’ll just shake off its nasty effects and get back to the frolicking.

I don’t buy it.

The launch of our Civilization, the very birth of the hated Leviathan itself—of Pharaohs, slaves, farms and giant blocks of Pyramid—was just as much the inevitable result of mechanistic forces acting on humanity as anything else.

Our creation of civilization was a consequence of our physical limitations.

We desire contact with the world and with one another. Our species evolved in its ecosystem with certain innate limitations, certain rigidities. With our creativeness we sought to increase our fluidity, and thus our interrelation, our contact. But we did this individually. We failed to universalize our empathy. We ignored the golden rule and failed to see others as ourself. We progressively saw people as things and used them as things to fulfill our desire for contact with the world. Thus one individual wouldn’t value or take into account another individual’s desire for contact and, in increasing his own capacity for contact, would decrease theirs.

The pharaoh can travel many places, see many things, handle many things and shape them in ways his body alone never could. But to accomplish this he has to reduce people into his technologies, his things. Reduced to relatively rigid processes, their creativity is reduced. And thus, though the pharaoh’s personal whims can now build mountains, the net creativity at work in the world is reduced. The pharaoh initially moves plenty in relation to others, but the others don’t move at all, thus the system increases in rigidity and quickly the Pharaoh’s own movement is reigned in by the surrounding behemoth.

Our mistake, our failure to realize the golden rule of empathy, of solidarity in liberty, is not an isolated mistake. It is not a single mistake made by some distant ancestors, but a continuous mistake that is made again and again. Stronger in some places and weaker in others. It predates the “start” of our civilization. That “beginning” was simply the first real opportunity it had to compound in new ways. (An unusually facilitative climate had finally lined up with an invention that made use of it.)

Godesky claims that freeing ourselves from this mistake is impossible. A matter of idealism. An abhorrent and ridiculous fool’s errand. To be rejected out of hand. We can’t make the world a better place! Come on! We can’t accomplish anything in this world, we can only hope to survive it in some degree of comfort! He stealthily but implicitly claims that freeing ourselves from such psychosis—such constructed alienation—is so fundamentally beyond us as to not even warrant consideration. That there will always be a significant fraction of our society preying on the weak and pursuing power with whatever strength they are given. That such evil is just an inherent part of humanity. That, at heart, we’re just not very good. And we don’t have—and can never have—the agency, the free will, to better ourselves.

This is, Godesky asserts, the core of what it means to be “human.” Limitation. To dare to challenge it is to attack the greatest of all gods, the greatest of all idols: our fundamental identity. (As assigned to us by Godesky and his interpretation of Biology.)

But we are also unquestionably curious, inquisitive and exploratory creatures. His framework begs the question, then do we really have the free will to overcome our curiosity? Our relentless drive for contact?

Fact of the matter is, we will continue building technology no matter what, continue exploring and reaching out. And—without the material capacity to continue fluidly building our tech, without the capacity to touch beyond our shallow immediacies—we will continue to make the mistake. The mistake that has plagued and almost defined our Civilization. The mistake of power and control. We might not be able to go as far with it. But we will endlessly return. And the memory of past heights will press us everywhere. The knowledge of our basic, root industries and processes will remain and persist in perpetuity. With these globalized seeds left by our Civilization we will work harder and harder to enslave one another.

We will always seek contact and—so long as folks continue to make the mistake—we will perpetually rebuild the horrors of our civilization. A particularly violent collapse may limit the degree to which these horrors can be rebuilt, but that will just permanently trap us at that maximum. With no hope of overcoming it and changing the motivating realities.

Social realities are inseparable from material realities. If you remove our physical capability for a greater degree of interrelation. If you reduce the possibilities for non-linear interaction. If you reduce the material fluidity. It will have results. It will drastically reduce the fluidity of our society. It will ingrain social rigidities.

A permanent—Derrik Jensen style—collapse would hinder the application of our creativity and restrict possibilities of contact. But it would leave the motivating forces behind the horrors of our “Civilization” intact. Eventually regrowing the blunt hierarchies and empires of near-history up to precisely their highest capacity given what’s left of our biosphere. (And though advanced metallurgy may become impossible, agriculture simply won’t disappear.)

We will never be able or even capable of returning to innocence. The core of our Civilization will persist. In fact it will flourish. Stripped of the complexities, of the non-linear interrelation, of the fluidities that so plague it today. The beast will return, it will evolve. Finally able to capitalize on its successes. No, it won’t grow to such dramatic heights as we are used to—and an end to the Holocene certainly wouldn’t help—but what remains will be far more intractable. Less room for ingenuity, less capability for physical developments.

In a certain sense, the horrors of Civilization will always be the inevitable result of any primitive society. The social structures that survive. The psychoses that best dig into our souls.

But for now, at least, there’s hope. Technological progress breaks down such social rigidity just as it breaks down material rigidity. And our modern world isn’t really characterized by the centralization of our power structures, but rather the increasing opportunities of non-linear contact.

Of course Godesky, keen to disregard electron microscopes and cellphones, harps on about how technology doesn’t provide real contact, just “mediated” contact.

What. The. Crap.

Let’s pause for a moment and dwell on this.

All of our contact is mediated. All of it.

Godesky’s distinction is ludicrous and non-existent. Nerve bundles in my head mediate my contact with the cup I’m holding. Air mediates the sound of my voice. Photons mediate contact between the stars and my eye which, in turn, my optic nerve mediates further. So the fuck would it matter if there’s suddenly a curved piece of glass along the way? The fuck does it matter if the Hubble telescope and a bunch of circuits and radio signals is involved along the way? Using a telescope gives me stronger, more direct contact than traditional eye processes.

Everything is mediated. What matters is how well a given avenue is able to mediate your contact. Cellphones filter out nuances of language, but they allow us to contact over great distances.

The feral hunter is aware of the world around her, feels contact mediated back to her along a million vectors.

Her cellphone rings. Her sister in Quebec is watching the most amazing Aurora Borealis and wants to share some small measure of the experience. Click. The picture is shared.

The problems arise when we ignore and close ourselves off from each other and the world around us.

The hunter zones out chatting on her cellphone, alienating herself from the rustling forest around her. She can even do it playing in the dirt. …Becoming so engrossed by the patterns in the stack of twigs she’s built that her play begins to transform into addiction. She her mind solidifies, she fails to engage, to actively integrate with the world around her.

Any number of processes or cognitive structures can slam rigid bars around our mind. Our civilization aggravates this by forcing participation in such structures upon us. The world around us is fenced in. We are not given the freedom to opt-out. To turn off the cellphone and chase kites down the beach. Because of this, processes like the cellphone—unto itself nothing more than a tool allowing the extension of possible contact—are slowly and forcibly made our only avenues of contact.

For example it speaks great volumes about the state of our social, cultural and economic constructs that the lives of homeless families on the streets of our great cities increasingly revolve around and are enslaved by their possession of a cellphone! Can’t get a job unless you have a number. Can’t get into the shelter. Can’t get a bowl to eat. Hover over it, waiting for master to ring the bell. Rather pay the bill than pay for food. All our interactions have to be controlled, directed, restricted and limited until we have no more capacity to act or express anything beyond the bounds of the established system’s structure.

The sociological constructs of our Civilization survive and flourish by cutting off our contact. By denying us communication. We have blogs and live twitter accounts, yet social norms and systematic antibodies of irony and metatext still widely rein us in from utilizing the connection they promise.

But those chains, through they collaborate across the expanse this prison we call society are ultimately grounded in our personal abdications. Fear. Our embrace of the machine into our hearts, rather than the embrace of our hearts into the machine. And such paralyzing fear can be overcome.

We can open up and embrace the world around us. Instead of choking our hearts behind rigid networks of concrete highways what if we reached out and washed away the imposing bypasses and overdrives for something deeper? An open, mass society where we might more freely fulfill our desire for contact, for touch.

Godesky—in a last ditch effort—claims that we simply don’t have the neurological capacity to handle such a fluid and richly textured world. In fact, he argues that increased non-linear interconnection is bad for us. (I shit you not.)

He begins innocently enough by pulling out an old hazy social science theory called “Dunbar’s Limit” which shakily inferred that homo sapiens were fundamentally incapable of forming and sustaining more than 150 relationships with people. Family, friends, associates, rivals… whathaveyou. Even in the modern world most peoples’ relationships boil down to pretty much what we had back in our tribal days. We keep track of a hundred or so relationships and those people keep track of about a hundred or so of their own relationships… until we all lead back to a maniacally cackling Kevin Bacon. While these little nets of relationships used to be closed up in tight bundles of people who only really knew each other, today we each have our own partially overlapping nets.

Now, this is more or less true. Of course it’s worth pointing out that the “evidence” behind Dunbar’s Limit is simply social trends and has no direct basis in neurology. So the 150 number is more or less bullshit. But, hey, no one’s denying that the human brain has a limited carrying capacity. We can’t each simultaneously maintain personal relationships with all 6.5 billion people on Earth. There’s no way I’m going to fucking remember that some random yob in Manhattan likes Fruit Loops for breakfast, hates his Nephew, is fascinated by Indonesian Jazz, saw his sister raped as a child, has to get the last word in every conversation, takes pride in his automotive expertise, has never been kissed and constantly fears he’s going to die alone.

The structures of our relationships are characterized by a lot of information—a good portion of it more subtle and not so blithely quantifiable—but nevertheless information. And at the end of the day Godesky is right; the human brain has a limited storage capacity.

But so what? After all, Mr. Unloved Fruit-Loops-Eater can start a blog or put his life online and that the internet can store away all that for me until the moment I need to “remember” it. Trading bicycle micro-insurance information outside of El Paso. The bent wheel I accidentally gave him (absentmindedly coasting down the bike path at an awkward angle as I chased a flock of birds flying in tandem above me and re-reading an instant message just sent to me by a lover in Boise) is going to make him late to his Indonesian Jazz festival and his Nephew made such a big deal about his choice to take a vacation… Finding a shop and getting it repaired would be quite an inconvenience for him, so I just wrench off my good wheel and give it to him. It’s a shoddy fit but it’ll get him to the festival on time.

All this is possible because an increase of fluid technologies offers an increase of fluid contact. Structures of association dissolved and reformed instantaneously. We’re already at the point where we Google people before meeting them. The myths of privacy evaporating as every social interconnection is more closely interwoven. And it works because with the increase in connectivity has come an increase of passive memory and analytical power. Something as boisterous and wild as the human mind should not be slave to rigid structures: Screw memorizing a shopping list… write it on a sheet of paper! No, we can’t keep track of the entire fucking world, but why should we? A truly fluid, dynamic, organic world will keep track of itself.

But of course Godesky’s invocation of Dunbar’s Limit is extraordinarily broad. He declares that mass society will be fundamentally flawed because we cannot each sustain 6.5 billion relationships and thus: we cannot function as a globalized society because people beyond our 150 are “unreal” to us, so we exploit them.

This is a big step. Essentially he’s asserting that the informational structure of our relationships with others is the essential component of their moral reality to us.

Other people are just information structures to us. Our brains can only retain so many information structures. We can’t really deal with the existence of people beyond our 150. The people beyond our immediate tribe are just phantoms, blurs, stereotypes and empty impressions. So we don’t really consider them in our moral calculus. Thus everyone screws over everyone else.

On the face of it, this argument makes quite a bit of sense.

The CEO will go out of his way to protect and pamper those people he’s built a relationship with. He’ll check the chemical concentrations in his family’s water supply, advise his friends to buy organic food and move his father to a place with less smog. But when a report rolls across his desk saying the company’s policy of dumping toxins will result in 2,000 cases of cancer this year, it doesn’t really mean anything to him. We watch roadside bombs explode in surround sound on the nightly news and don’t give a damn. Nobody we know is serving. The structures of our immediate social environment are safe from turmoil.

When our sister is mugged in an alleyway that’s an assault on the social structures that we’ve built around ourselves. Her identity and relationship to us changes in ever-so-slight ways. Her emotional state directly affects the way she relates to us. For a brief while she’s less likely to keep up the normal level of positive feedback with our personal social, cultural and memetic structures. Which means less good times at the pub cheerfully complaining about mum, and more grouchiness or neediness. So when we first hear that she got mugged we immediately register an annoyance and mutual outrage at the assault on the common structures of our lives. But when we’re waiting for the bus and someone mentions they got mugged the other day the response is far less visceral. Fuck if we’re ever going to see this aggrieved person ever again.

We don’t care about the stranger, after all.

Now listen closely cuz here it comes:

But we do.

The Good Samaritan is not some minor side biological function hardwired into us that only sporadically emerges to help us beat game theory. It stems from the core of who we are. The basic human state is one of empathy and compassion. At our greatest heights, when we are at our most human, we don’t make such rigid distinctions. Wild and free, we are not subject to the cold structures of arbitrary identity, and plenty of people, even in the alienating chains of our society, are able recognize the self-worth of strangers, unfettered and unrestrained by crude caricature. The “relationships” covered by Dunbar’s Limit are at the very least utterly irrelevant to moral action.

In fact, while we might have the neurological capability to completely understand the full context of maybe one other person, any larger number, much less a whole fucking tribe, is inherently preposterous. The impressions we maintain of our associates are ultimately going to be abstractions. Now to Godesky they're abstractions that have passed a certain magical degree of detail that he’d consider them “good” abstractions, but there’s no denying that they’re still structures. Rigid constructs.

To be clear: In order to utilize Dumbar’s Limit the way he wants to Godesky has to implicitly assert that we are nothing more than the structure of our ‘relationships.’ That the whole of our moral reality is our identity. A set of structured information and our ethical behavior, our empathy, our recognition of common humanity is solely a consequence of holding those structures in one’s head.

If this seems particularly wrong to you, that’s because it is.

The CEO may dole out his acts of “compassion” according to some structural framework, but real human empathy would seem to transcend such selfish constructs. Sure, when your sister is mugged part of your reaction is partially framed by structural ties the two of you have. You may despise the robber for imposing on your shared social frameworks and constructs. But you also empathize with her. Ignoring the baggage of your different identities, of the different structures around each of you, a part of you instinctively sees yourself in her shoes. The same as you might for anyone else.

Bring to attention any random injustice against an individual and our natural reaction is one of solidarity. We associate with other people. And though we may not be able to personally maintain awareness of every injustice in the world (more on that later), we recognize injustice whenever we have some degree of contact with it. Shine a camera on gunned down Cambodian students and we react viscerally. That’s why altruistic and gift economies work even between strangers. Empathy is our default.

It takes training to break apart and form bars against our common humanity. Rigidities in the form of simplifications, abstract constructs and formalized chains.

You see, such ‘relationships’ are themselves the problem.

No matter how finely detailed, they will still be the context of our lives, not the substance. It is such structures, frameworks and identities that dehumanize us. Binding us together in the chains of alienation. We are rebuilt as a thing. As a set of properties. We become nothing more than the framework of how we are used. A function of our uses. We become the banality of the structure around us. The machine.

It is through such structure that creativity, vitality and empathy are denied.

Mother, daughter, nephew, medicine man, chief…. the further we turn people into things—wholly summarized by the frameworks of their relation to us—the easier it is to use them like things. Until the friend you write off as a jumble of social codes, behavioral patterns, likes and dislikes actually becomes another cog in the cubicle farms.

The only way we can begin to comprehend someone’s existence in any other fashion than as a tool or a thing to be used is to transpose ourself over them. We shed off the structures of our own identity and social position and take what’s left—that which necessarily isn’t and can’t be defined by any information structure—and recognize a mirrored copy of it in them.

You see Solidarity in Liberty isn’t some intangible mythical and unrealistic Mr. Roger’s Neighborhood utopian ideal, it’s the basic fucking principle upon which all social interrelation is first based. It’s the ubiquitous Golden Rule: minus all these tactical details and arbitrary fluff I am you, you are me.

Why the fuck would I want to impede you being you? Your creativity is my creativity, it’s the same fucking thing. It’s creativity! Our vitality and life is collectively independent of our individual contexts. Basic human empathy is universal. We see ourselves in others. We strip away the trappings around us and recognize the same driving force behind their eyes. There is no limit to such action because such action is itself the abolishment of limitations!

You see Godesky’s mistake; while our individual brains are indeed limited in their capacity to hold structures, that doesn’t actually mean anything with regard to our capacity for empathy. We can still spontaneously recognize the moral self-worth of any random set of individuals across we may interrelate with at any moment. (Neither does our supposed inability to hold a completely grainy rendition of large numbers in our minds impede our ability to recognize lots many individuals suffering from an injustice = bad, or to engage in fraction-based tactical approximations in personally addressing injustices.) Ultimately, of course, there’s no reason why we should be held back from self-growth in these areas. I’d love to have incredible calculative powers in my faculties, but it’s not that big of a concern, and it has no bearing whatsoever on my ability to recognize common humanity outside of a arbitrary set of people. In fact, in the short term Dunbar’s Limit might actually help make Mass Society possible. As the non-linear interrelatedness of our society increases, any remaining dominate social structures must necessarily become more and more extended in our lives. A vast extended rigid network of structure feeding upon further structure. Theoretically there could reach a point where the rising fluidness of our material technology would necessitate social structural controls too vast to take root in the human brain. The social power structures would start to dissolve, and the fluid inter-connecting technology remain. (And I claim this point has already arrived.)

In the context of Dunbar’s Limit, “relationships” per se, by nature of their relative insolubility, are the information structures that congeal in the absence of fluid contact. Technological progress increases the fluidity of our interaction with the material world and one another. Which means more possible and more conductive avenues of contact. And increasing avenues of contact mean that the victims of any injustices we might begin to commit are made instantaneously immediate to us.

The trick behind Mass Society’s functionality that we don’t have to hold together all our 150 relationships in perpetuity. Whereas it’s true that our brains have finite computational power to analyze contextual realities, they don’t have to be the same ones. We can recognize the complexities around ourselves and around others as individually necessary. Using the golden rule and thinking through our actions fluidly rather than reducing them to rigid structural processes. Dissolve and reform. Constantly. Organically.

The externalities of our actions are only made “external” when we force our minds into blunt immediate structures. Increasing creativity and increasing contact means that we will be incapable of pushing others off over the horizon and exploiting them. Our pollution is immediately known and the victims—two continents away—aren’t held at bay or forced to take it in silence. They are immediately in front of your face.

Instead of driving the Woolly Mammoths and Giant Sloths to extinction with our new slaughter pits, the macroscopic effects such processes have on the world are instantly apparent on Google Herdtracker.

The next test iteration of our popular Iron-forging kernel is instantly commented on and the bugs documented before going to beta across the planet, thus the CO2 production instability doesn’t result in a drawn out global system crash.

Even if my limited brain fails to comprehend the exploitative or unfair realities of my latest creative endeavor, the market will recognize it. The distribute processing power of humanity will convulse in reaction and the higher degree of communication, the deeper contact between us, will facilitate instantaneous response. Gift economics, post-scarcity economics, agorist economics, mutualist economics… they all recognize this reality. Because all economic systems of free association are based in the dynamics of social credit.

In a fluidly interconnected world whenever we begin to make The Mistake society heals the wound. Empires cannot find footing where the peasants can organize. Individuals cannot abuse or rule over one another when they can always pick up and bike over to the neighbors.

In trading comments Godesky has several times expressed blithely dismissive horror at the concept of a world without public privacy. I mean, if we rape and murder just one person, are we forever doomed to be ostracized?! Our track record always out in the open, where anyone can be warned?! There’s no longer the old fall back of just wandering off to a different tribe and starting all over again where they’re none the wiser?! (What a horror, I know.) This isn’t the space to flesh out all the wonderful ways post-privacy anarchies function. But seriously. Come on. Think about it for a second. Freedom of information means that alongside our sins will be our kindnesses and accomplishments. Our character growth, our dangers and our redemptions. Everyone makes mistakes. Only in a world where the lie of innocence is perpetuated do people throw stones.

Treating people like machines is only possible when people don’t have the machines to connect with one another. And furthermore they only think of turning their fellow man into machine when they have no other avenue to fulfill their desires and needs, no other hope. The dogmas of primitivism would completely and permanently cut many people—and ultimately all of us—off from such hope. After a certain point primitive societies just can’t provide (although, yes, they can sometimes provide the illusion of a band-aid). Think of the transgendered and intersexed. Of the stargazing old woman. The tree climbing young hunter who longs to feel the wind beneath wings. The scientist. The artist. The every fucking woman on the planet who wants to own her body.

Worse the actual collapse itself (if it doesn’t eradicate humanity) threatens to launch an unceasing, inescapable rendition of the middle-ages. You can get rid of advanced metals work wholesale, but you just can’t get rid of agriculture. Though it may shed off a few billion souls in wretched starvation, that shit will hold on. Yes, there will be room for an elite of hunter-gatherers on the periphery, but the majority of humans will forever more live under tyranny. The memories, the tricks of our hierarchies will not fade. But without room for invention to expand into, there will be little to shake it up. (We’re not going to make paradigm-breaking breakthroughs in grass basket weaving.) The Crash will be the forcible denial of hope. It will, more than anything else our Civilization has done, make us not-human.

Our Civilization has seen the preposterous compounding of old human hierarchies, of subjugation and alienation. But such horrors have been paralleled by an unrelenting resistance ever blossoming in scope. The human drive for contact is set in direct opposition to the drive for control. Control is impossible. Both Godesky and I agree on this point. What we disagree on is contact.