Zoë Dodd & Alexander McClelland

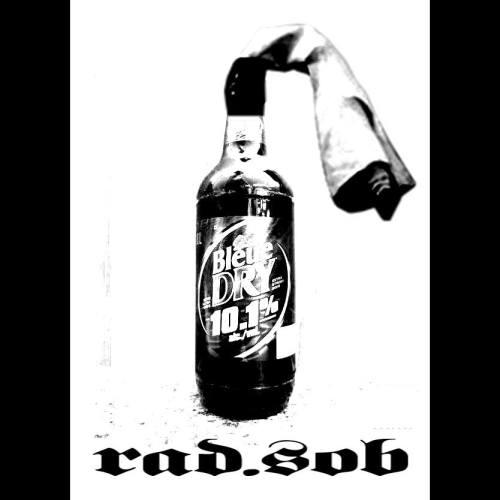

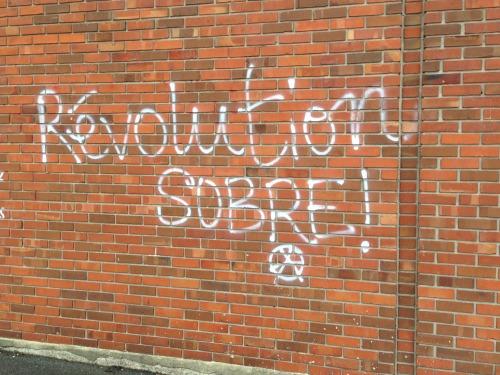

The revolution will not be sober

The problem with notions of “radical sobriety” & “intoxication culture”

What is “radical sobriety” and “intoxication culture”?

Concerns with the discourse of “radical sobriety and “intoxication culture”

Identity politics and the “sober addict”

As radicals and writers working on issues of criminalization and drug liberation, we believe that altering the relationships we have with our minds and bodies through substance use is a form of resistance and emancipation. For us, drug liberation is the emancipation of drugs deemed illegal and the people who use them from the control of the state and social structures. In our experience, drug use can facilitate authentic, compassionate, and emotionally bonded social relationships that are not possible otherwise. Drug use can be therapeutic and provide autonomy outside of the pathologizing system of western medicine for coping with trauma and difficult life experiences. Within an economic system that relies on our bodies as a tool of production under a capitalist rationality, getting high can be a tactic for survival, a therapeutic practice, and an active refusal to engage with capitalism.

Maximizing our own pleasure by getting high can be a political imperative when we live in a society that is organized around viewing our bodies and minds as a form of capital. Under a capitalist logic, pleasure as an end unto itself is often viewed as dangerous, selfish, problematic, and destructive. But for thousands of years people have been using all kinds of drugs and substances to alter their relationships with their minds, bodies, with each other, and with their physical environments. Drugs were (and still are) used for ceremonial purposes to expand people’s relationship to land, expand worldviews, and as forms of healing medicine. Drugs have been widely used for years within communities of self-proclaimed queers, dykes, fags, gender radicals, freaks, skids, and punks to fuck with the ways in which society understands how we are supposed to act and be in the world. It is via practices of colonization, the introduction of capitalism, liberal legal frameworks, and the proliferation of western medicine that certain kinds of drug use have been arbitrarily pathologized and highly regulated, producing moralistic notions of illicit drugs, “addiction”, and the “addict”.

Because of our experience as drug users, radicals and writers, as well as our historical and political understanding of drug use, we have been increasingly concerned about the emergence of “radical sobriety” and “intoxication culture” discussions among a range of anarchists and queer activists that have been proliferating online, at conferences, and in social spaces. These discussions are marked by the convergence of certain forms of anarchism, queer identity politics, and addiction recovery language. All wrapped up, this comes to produce a political logic that we believe is disconnected from history, from drug user rights movements, and could result in a form of politics that is potentially damaging to people who use drugs. With our analysis, we want to make it clear that we understand that these issues are deeply personal for some people, and we do not wish to undermine any one person’s experience with substance use and their own autonomy, but rather, we seek to analyze how notions of “radical sobriety” and “intoxication culture” are taken up as a cultural and political project. For clarity, when we reference drugs and substances in this article, we are talking about a wide range of natural and synthetic drugs, including alcohol, which people use for a range of differing reasons.

What is “radical sobriety” and “intoxication culture”?

In a politicized context, the concept of “radical sobriety” has come to be a way that some people are engaging with the language of addiction recovery in a range of activist communities. According to the Facebook page for the group Radical Sobriety Montreal, “it’s a grassroots response to the reality of widespread addiction in our communities and our lives”, and “believing that the personal is political, we try to engage with our addictions within the framework of radical political analysis”. As noted on the blog post Radical Sobriety: Situating the Discussion, these groups understand that “sobriety is central to morality”, and this approach to understanding abstinence from substance use is aimed at addressing “inebriation as a root of social problems, especially in a drug culture”. Within a radical sobriety framework, drugs are produced by a capitalist system and are being used as a tool of oppression against a range of communities. Soberness is understood as being closer to our natural human state prior to the emergence of oppressive forms of social organization. Here drugs are understood as producing false experiences, and authenticity in social and political relationships must be brought about through being sober. People from these groups address drug use as providing “an artificially altered state of mind” which produces “numbness to sensations and feelings”.

This politicized recovery framework uses the language of 12-step programs such as Alcoholics and Narcotics Anonymous, which ask members to claim a “ sober addict” identity. But, radical sobriety groups take this further, understanding the “addict” as a static political identity category and mobilize “safer space” language to claim accessibility entitlement to a range of spaces to accommodate their soberness. Claiming the identity of the “ sober addict” for “radical sobriety” people is a political practice to mobilize resistance against “intoxication culture”. Within “radical sobriety” groups, countering the pervasiveness of “intoxication culture” is a political project, as this negative “culture” is understood as oppressing communities and undermining the political aims of the radical left. For these people, “intoxication culture” is understood as a “tool of colonization”, and as driven by patriarchal and heteronormative rape culture. This culture is understood to dominate and promotes drinking and forms of drug use in a range of everyday activities and social spaces, such as at sporting events and dance parties.

In the context of “radical sobriety” discussions, sobriety is, as noted in the presentation Sobriety as Accessibility: Interrogating Intoxication Culture, “considered as a form of accessibility and resistance”. As further explained on the blog post Intoxication Culture is a Bore: “If you believe in accessibility, inclusivity and justice then it is your responsibility as a normative drinker to make space for people who can’t and don’t drink”. The result of claiming addiction as an accessibility issue is that people who are not self-described “addicts”, and whom use substances, are constructed as having a form of privilege that those who are not “addicted” do not have access. The language of accessibility and privilege are mobilized to call claims for safe spaces for the “radically sober”.

Using a monolithic notion of “culture”, this approach also sees “intoxication culture” as producing the “addict”. To reclaim the notion of the “sober addict”, “radical sobriety“ groups use the language of disability rights scholars and activists who understand disability as being produced socially and not as an individual issue. This approach has been very productive for many important and powerful disability rights groups and other accessibility rights groups in focusing attention away from individual and people’s different bodies and abilities, to rather address the barriers in society that produce understandings of ability and disability, and accessibility and inaccessibility. Within a accessibility framework, the political project comes to be organized around calls for social change to enable new ways of accommodating a range of abilities and to enable forms of accessibility, such as making spaces wheelchair accessible or making events pay-what-you-can.

In some of their discussions, “radical sobriety” people also have a somewhat nuanced understanding of the social complexities around substance use, as that was originally developed by people working in harm reduction and drug user rights movements. For example, “radical sobriety” groups will sometimes state that addiction is exacerbated by social issues such as lack of housing and poverty, they critique how western medicine understands the individualization of addiction, they talk about the differential effects of the drug hierarchy based on class, race and gender, and they talk about how people who use drugs are considered disposable in society.

But despite possibly good intentions, the problem is that more broadly these “radical sobriety” discussions could cause damage to people who use drugs, including people who use drugs in radical organizing spaces. The problem is that this new discourse is ahistorical and could be furthering moralistic and stigmatizing attitudes and practices. The problem is that there are major flaws in the arguments of “radical sobriety”, which fail to address key political targets and forms of analysis. Thus, instead of uncritically accepting the ideas that it is proposing, we find ourselves with the imperative to interrogate “radical sobriety”.

Concerns with the discourse of “radical sobriety and “intoxication culture”

For decades, groups of people who use drugs have been organizing in collectives to address a range of vital issues impacting their lives, such as working to change damaging criminal laws, barriers to healthcare, and to alter the negative social perception of active drugs users. These groups work with an ethic of “nothing about us, without us” and they have radically transformed policies and approaches, such as initiating harm reduction as a widespread non-judgmental approach to support drug users to realize their own health and claim agency over their lives. Based on this movement, other radicals working on issues related to drugs have an imperative to engage with and understand work of drug user organizers (outside of one’s personal drug history and personal needs to be high or remain sober).

Despite coming from the individual perspective of past drug use, the discourse of the “radically sober” fails to account for (and completely negates) the experiences of active drug users and the decades of experience of drug user organizers. For example, for many years, movements of people who drugs, including the International Network of People Who Use Drug (INPUD), the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (VANDU), L’Association Québécoise pour la promotion de la santé des personnes utilisatrices de drogues (AQPSUD), and the Toronto Drug Users Union (TDUU) have critiqued notions of addiction and have called for an end to the use of the term “addict”. Drug user movements actively call for a shift away from conceptualizing drug use in terms of “addiction”, as this approach has been used to pathologize, medicalize and criminalize drug users. These groups have highlighted that the language of “addiction” does not allow the space for real discussion of the myriad experiences of substance use in people’s lives. This results in a view that understands all drug use as a problem that needs any number of forms of expertise to correct through recovery programs, drug courts, criminal sanctions, and medical rehabilitation.

When engaging with movements of people who use drugs, perspectives on the concept of “addiction” and the political objectives that are needed to achieve emancipation are vastly different than those who engage in “radical sobriety”. In the view of many proponents of recovery, such as people involved in “radical sobriety”, people who are understood to become “addicts” are the product of a dominant culture that promotes popularized forms of drug use. In their view, substance use keeps various marginalized populations oppressed, and emancipation is thus achieved through being sober. But this understanding is divorced from the history of colonization, liberal legal frameworks and medicalization. As many active drug users know, drug use is not inherently connected to “addiction” or problematic use, for example, 80–90% of people who use drugs do not have a problem with their substance use. Ideas about “addiction” being based in science are flawed and has been disproven (read the work of Carl Hart and get back to us) Drug use only became understood as something that is “wrong” when specific frameworks of morality were developed and imposed onto groups of people who used drugs.

Notions of “addiction” and the “addict” have been constructed over time by white, wealthy moral authorities such as religious groups, medical experts, psychologists, politicians, police and criminal justice systems. Mobilizing negative, pathologizing ideas of “addiction” and the “addict” has been part of the projects of colonization and other forms of social control of poor people and people of colour. This kind of pathologizing people has led to the to rise of forms of treatment detention and forced treatment. It is the fear of the “addict” which people use so as to continue to scapegoat and attack. The idea of the highly racialized, classed and gendered “addict” has the ability and power to strip people of all of their other identities and becomes the only focus for understanding the individual. This logic is what forces people on welfare to be drug tested, children to be removed from their homes, and people locked up for what they put in their bodies (despite no harm to anyone else). With this understanding, the “tool of colonization” is not substance use, but rather an oppressive system of laws and institutions organized around controlling and incapacitating groups of people deemed different, specifically those who do not fit within a moral and capitalist logic.

Drug users rights organizations understand that we need liberation from oppressive structures, which act to classify, control, and criminalize people who use drugs. Here it is not about focusing on an individuals right to sobriety, but rather on the end to the war on drugs through the repeal of criminal laws, rejection of western medical categories, and the reform of notions of recovery.

Through continuing to mobilize notions of “addiction” and “addict”, as well as not engaging with or accounting for the legacy of activism by drug user rights movements, so-called radicals in the “radical sobriety” movement could be unwittingly promoting the aims of the ongoing colonial project and furthering a pathologizing logic which results in criminalizing people who use drugs and denying them agency over their lives. These are major concerns for those working in activist communities, especially for those who are working to address issues of damaging laws, prisons, mass incarceration, criminalization, health-care access, and forms of social marginalization that are driven by pathologizing attitudes towards people who use drugs.

Identity politics and the “sober addict”

We keep seeing more and more claims for accessibility for activist and social spaces for people who claim “radical sobriety” as an identity, and we feel concerned. These claims come in the form of Facebook posts to event organizers asking for events to be made accessible for sober people, workshops at anarchist and radical events, zines and blogs. Identity categories are not inherently natural, and they are not static. They can be fluid, develop over time, and can also be produced through a range of forms of domination. It can be claimed that people making arguments against forms of identity politics are trying to negate the experiences of people who take on certain identities. In our case, we must stress that this could not be further from the truth. We are not against anyone’s personal imperative to stake claim on an identity, and we have also used identity categories to make political claims in our activist work. But, in this context, we do question the outcome of using this kind of politic. The problem is that in some cases identity politics can result in a sole focus on the maintenance of identity formations rather than on broader forms of emancipation.

Within “radical sobriety” the “sober addict” has become a static identity category that then becomes part of a place for one to talk about personal issues of accessibility and other people’s privilege who are using drugs. But as we have stated, mobilizing notions of the “addict” marginalizes people who are active drug users. “Radical sobriety” people position the “sober addict” as emancipated, but also continually oppressed within the “intoxication culture”. The “sober addict” then needs to be accommodated as a rights and social justice issue. Other people’s drug use is a privilege and needs to be checked. This sets up a dualism where accessibility is only articulated in relation to the “radically sober” person, and where accessibility for people who are active drug users is rarely considered. The focus becomes not on talking about liberation from the various forms of marginalization that have created precarity in the lives of people who use drugs, or on the conditions that have produced notions of “addiction”, but rather, the focus is attuned to maintaining the oppressed identity of the “sober addict” who is entitled to forms of accommodation, such as making social spaces or events sober, or to have specific spaces for sober people at events.

A longstanding critique of identity-based strategies is that they have the potential to produce an “essential” experience of identities that can erase other experience in the process. Also, with identity politics, confessions of individual difference and call-outs about privilege can become the political project themselves. For example, the statement “I am ________ and I am a sober addict” actually does nothing to dismantle the systems of oppression surrounding people who use drugs or other forms of power and privilege. Here being “oppressed” holds a certain cultural and social capital for people in particular activist contexts. People thus aspire to be oppressed, where the goal is not an end to oppression, but rather to be as oppressed as possible. This political project can miss a broader critique of history, economy and society, as political targets. This approach to activism has been widely critiqued as promoting neoliberal aims through its endless attention to the individualist liberal notions of human rights.

Also, in this context, the monolithic notion of “intoxication culture” as promoted by “radical sobriety” people poses a problem. There are many cultures for which using forms of drugs are traditional, sacred, and a regular part of people’s daily lives. We need to understand the plurality of cultures. Culture is not homogeneous. Prescribing moral frameworks onto cultures to define if they are good or bad based on how people use drugs within them can employ a racist, classist and colonizing logic. We need to accept that a wide range of people from diverse communities use recreational drugs for a range of reasons. Buying into the notion of the “addict” buys into oppressive models and allows no room and space for people who want to engage in substance use in different ways.

People need a range of spaces to exist in. We are not opposed to sober spaces, and we are not opposed to people creating their own spaces to accommodate what they need. We are not interested in is that kind of dichotomous way of understanding activism. Buying into the moralistic frameworks designed to marginalize and oppress people who actively use drugs will never be a radical act. Anti-drug sentiments have been used historically to exclude active drug users from a range of activist movements. This is why we find the “radical sobriety” discourse so concerning. We are concerned about people who use drugs feeling unwelcome in activist organizing and social spaces. Active drug users are often highly marginalized from activist communities and radical social spaces because they make people feel uncomfortable. We need a more emancipatory framework that can support a range of people’s needs without creating dividing lines and claiming identities that result in othering and marginalization.

Recovery as a form of oppression

“Radical sobriety” discussions are organized around the basic principles of mainstream prohibitionist recovery programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous and other 12-step programs. “Radical sobriety” discussions, while having some critiques of these approaches, also adopt the primary approach of these interventions which understand addiction as a disease that needs to be corrected solely through individual intervention. To believe that “addiction” is a disease is also to believe that “addiction” is a life-long “problem”. A focus on the individual failing of certain people results in a corrective logic that is aimed at fixing or forcing that person to change to better fit into society. This is an idea that we know to be a myth, a myth that obscures how notions of “addiction” and “dependency” come to be constructed. This is a widely popular and very damaging misconception, which continues to fuel prohibitionist policies and the drug war.

A society based on capitalism generates enormous wealth and at the same time breaks down every traditional form of social cohesion, creates dislocation, and social isolation, poverty and also pathologizes notions of “dependency”. The idea of “dependency” is a construct born out of liberal individualism, where every person is an island, and the ideal is the autonomous rational subject. When the reality is that dependency is “normal” or rather is constitutive of what it is to be human. We all depend on others and things, and only exist in relation to others and things.

Defining an individual as the problem, as an “addict” with a disease that has no self-control has allowed communities and governments to get off the hook for taking care of each other. Recovery programs are not designed to help aspects of society change to address forms of oppression and violence, which could drive people to use drugs in ways that they may feel are problematic. Within a capitalist framework, beyond Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous, many recovery programs generate a massive amount of wealth for certain groups of people. But generally, individualized recovery programs are the only models out there. While some of these options provide a sense of community and solidarity for people, the foundation of recovery programs continues to drive a pathologizing logic that needs to be challenged.

Drug use can be a radical act

“Radical sobriety” people have named our experiences while high as “inauthentic”. This naming of others experiences employs a colonizing and paternalistic logic, and the same kind of moralism that leads to criminalization and pathologization. Notions of the “right” way to be and the “wrong” way to be are what drive practices of exclusion targeting people who actively use drugs. Shouldn’t promoting personal autonomy and self-determination be central to our commitment to working to change society for the better? Shouldn’t radicals allow people to claim their own experiences for themselves? Shouldn’t radicals understand that people must be allowed agency over their own bodies; to ingest what they want, when they want? If so, then why engage with systems that prescribe forms of morality over others? Certain kinds of radical political organizers do turn towards forms of morality politics. We have seen this happen to radical movements that moralize bodies — from women’s temperance movements to anti-pornography feminism in the 80’s to sex work abolitionists of today. But morality politics is always a tool of the conservative right, and can never be successfully used by the radical left as these approaches produce the conditions of their own demise. They produce the possibility of cooptation by liberal moderates, and exploitation of their morality by the conservative right — who truly have the authority over cultures of morality, and have the greatest experience in mobilizing morality for their own political gains. Further moralizing forms of drug use will only result in more danger and insecurity in our lives.

There are no doubts that drug control policies have also been mobilized as a tool of oppression. But we must understand these issues are not inherent in the drugs themselves, it is a broader system of oppression which needs to be dismantled and this includes the liberation of drugs (i.e. the removal of laws and forms of morality which result in the social exclusion of people who actively use drugs). We can’t rely on oppressive institutions to define our activist work. We need to build our own ways, through creating circles of care and new forms of harm reduction support for those who need it. We need to create space for people to come together to foster new forms of healing and social connection.

We need to bring pleasure back in to discussion of drug use. We know that our experiences while high are authentic, real and have been powerful. Altering reality can bring beauty, magic, transcendence and new understandings to our daily lives. Radicals of all sorts have used drugs to enable themselves to question how things are organized and to be critical of the world around them. People politically organize in many kinds of spaces including bars, workplaces, parties, and community spaces while intoxicated. Organizing does not happen through one homogeneous experience. Intoxication does not negate the nature of people’s ability to be authentic, to go in the world, be a good organizer, or get shit done.

Thank you to wonderful Eliot Ross Albers, Ian Bradley-Perrin, Nora Butler Burke, Liam Michaud, Zachary Grant and Kate Mason for your thoughtful and invaluable support and feedback during the development of this article.