Black Rose Anarchist Federation

Turning the Tide

An Anarchist Program for Popular Power

Social Revolution & Libertarian Socialism

Conjunctural Analysis: Navigating a World of Constant Crisis

Institutional and Electoral Dead Ends

A Climate Crisis that the System Can’t Solve

Climate Crisis-Driven Mass Migration

General Introduction

This is the political program of our organization, Black Rose Anarchist Federation / Federación Anarquista Rosa Negra (BRRN). The writings it contains are the result of nearly two years of collective analysis, discussion, and debate. The content of the program is divided into three parts: sections that detail our understanding of the social, political, and economic structures of domination that give shape to our society; a description of the world we are fighting to bring into existence; and sections that outline the strategic and tactical means by which we intend to achieve our aims.

Our world is convulsed by an incredibly complex set of interlocking crises both new and old: war, rising nationalism, nativism and white supremacy, patriarchal backlash, economic instability, hyperexploitation, and more. At least one of these crises, climate change, represents an impending existential threat to the future of humanity. In order to combat these issues, to attack and abolish the system of domination from which they originate and, most importantly, to assist in advancing a revolutionary social transformation, we believe that an organization like ours must have a shared analysis, a unified set of objectives, and a decisive plan of action.

We agree with Errico Malatesta who asserted in 1890 that “the foundation stone and chief bond of an anarchist organization should be the program understood and embraced by all.” [1] We share this conviction not only because the program is a tool to facilitate greater political and theoretical coherence but also because it serves as a shared roadmap that aligns our day-to-day activity with a broader strategy for revolutionary transformation.

As a revolutionary anarchist organization, we believe a program is essential. We hope that ours will encourage and advance the capacities of the anarchist movement in the United States. Like much of the revolutionary left in our country, the anarchist movement suffered enormously from state repression over the last hundred years, causing it to become isolated and leaving it disconnected from many of the ongoing fights waged by the dominated classes. Although some mass movements in the early twenty-first century embraced anarchist ideas, the connection between everyday social struggle and the anarchist movement is still weak. Our organization was founded ten years ago with the intention of not only strengthening that connection, but organizing and concentrating anarchist intervention in social conflicts. Much like the Anarchist Federation of Rio de Janeiro’s (FARJ) stated aim to “recover the social vector of anarchism” in their own national context, we in Black Rose / Rosa Negra have labored to foster the anarchist principles of class independence, self-management, militancy, direct democracy, and direct action, among others, within social movements in the United States.[2] This program is an affirmation and deepening of that commitment.

We do not view our program as above reproach, however. We embrace it as a living document that reflects our ongoing collective work. Its contents are subject to change in response to the dynamic nature of the world we inhabit, and the experience we gain in social struggles.

In building our program we have drawn upon a wide range of resources both historical and contemporary. Our greatest asset in this process has been the advice and collaborative support we have enjoyed from our international sibling organizations. In particular, insights provided through discussion with current and former organizations within the Brazilian Anarchist Coordination (CAB) and our study of their 2017 article For a Theory of Strategy were instrumental to shaping our approach. [3]

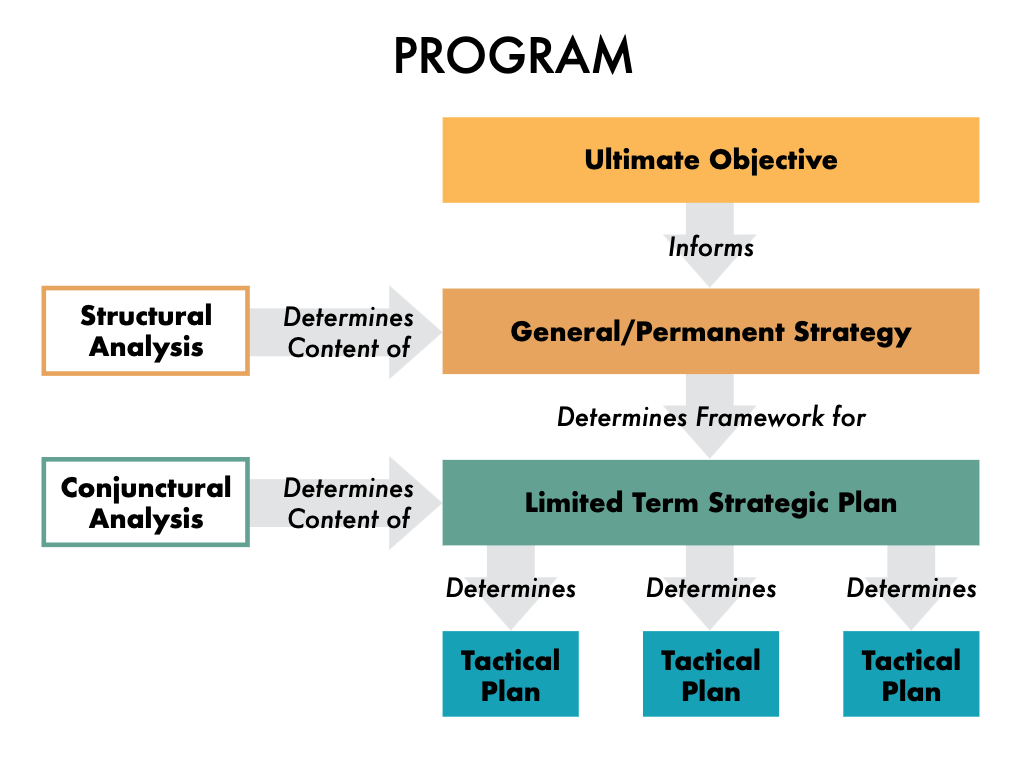

This guidance allowed us to produce a cohesive document in which sections build upon and inform each other. For example, our general strategy directly corresponds to our ultimate objective and our analysis of the structures of domination that define our world; our limited-term strategy is directly informed by our analysis of the current conjuncture, and so on. While each section can stand independently, together they form a comprehensive whole.

The road ahead is full of difficulties and there are no guarantees. We are committed to the struggle towards social revolution and building a libertarian socialist society. To achieve these aims we must understand the terrain we stand on and have a decisive strategy to navigate it. This is what our program provides.

Build popular power!

For libertarian socialism!

Black Rose Anarchist Federation / Federación Anarquista Rosa Negra

May 1, 2023

Structural Analysis

Introduction

Our world is divided between the few who dominate and the many who are dominated. This deep-seated division is the product of the core structures that define our society: capitalism, the state, heteropatriarchy, imperialism, settler colonialism, and white supremacy. Although we will analyze these structures individually, we see each as mutually reinforcing expressions of a broader system of domination. These structures have changed over time, but their fundamental features have remained resilient.

To understand the nature and resilience of these structures, we first have to look at how we understand power. Many anarchists, past and present, see power as synonymous with the state, as equivalent to exploitation and domination, as something that needs to be destroyed. Instead, we understand power as a relationship, shaped by the ongoing struggle between social forces in society, particularly between the dominant and dominated classes.[4],[5] The balance of power between these conflicting classes varies by time and place depending on which side has the capacity to achieve its goals despite resistance from opposing forces.

We should also clarify how we define “class,” which is key to our understanding of power, and which differs from narrower Marxist conceptions. Like power, we see class as a relationship. In this sense, class is defined in relation to ownership or control not only of the means of production (e.g. machinery, land, housing), which we share with Marxism, but also of the means of coercion (e.g. police, military, prisons) and administration (e.g. governmental bodies that create and administer the laws). [6],[7] Those who own or control the means of production, coercion, and administration are part of the dominant classes (e.g. capitalists, political officials, military leadership, police, judges, governors), placing them in a structural position to exploit, oppress, and dominate those who do not, who are part of the dominated classes (e.g. waged, unwaged and precarious workers, the unemployed, and the incarcerated).

The dominated classes are not a monolith. While we are united by our lack of ownership or control over the means of production, coercion, and administration, we often experience or understand this shared status in different ways due to a number of factors: from how we are racialized and gendered, to our citizenship status. The dominated classes represent the vast majority of the population in all its diversity, but those of us at the sharpest edges of the system—Black, Indigenous, LGBTQ people, undocumented immigrants, and incarcerated people, etc.—are disproportionately represented in its ranks.

Class is inseparable from other forms of domination. The same structures and relationships that define class, for example, also shape racialized and gendered domination, and vice versa. Race, class, gender, sexuality, ability, among other social categories, are mutually constructed elements that define the system of domination.

This system is deeply embedded. It is reinforced by mainstream culture, internal divisions within the dominated classes, and a complex mix of consent, coercion, and co-optation. But its relative stability depends on the intensity of class struggle and the power that either side is able to wield, keeping in mind: a) power is a fact of life, present in all social relationships and at all levels of society, from the institutional to the interpersonal; b) power is not inherently good or bad, but contingent on how it is mobilized and toward what end; and c) power can be changed, but not eliminated—our task is to shift the balance of power in favor of the dominated classes.

This document is BRRN’s structural analysis. With it, we hope to expose the root causes of the many social, political, economic, and ecological challenges that shape the balance of power and the terrain of class struggle. Understanding how and why the following structures operate is a critical step toward dismantling the system of domination and laying the foundation for a free, socialist society.

Capitalism

From its origins in Western Europe in the eighteenth century, capitalism has spread unevenly around the globe, leaving inequality, poverty, and ecological devastation in its wake.

At its core, capitalism is a social, political, and economic system defined by private ownership or control of the means of production and reproduction (e.g. factories, apartment buildings, and land), waged and unwaged labor, and production and exchange for profit. These factors give shape to a brutal class society—protected and promoted by the state—that benefits the few at the expense of the vast majority of the population and the planet.

In capitalist societies, the bulk of the means of production are owned or controlled by a small fraction of the population—the capitalist class. Through direct control of society’s essential resources and sources of wealth, the capitalist class occupies a structural position that enables it to wield enormous power over our lives, from deciding whether we get hired or fired to how much we pay for rent, food, clothing, and healthcare, not to mention the fact that these things are bought and sold in the first place.

Those who do not own or control the means of production—the working class—make up the vast majority of the population. Lacking ownership or control over the means of production, we are forced to sell our labor, our bodies, our time and our minds in exchange for a wage (or depend on others who do) in order to gain access to the resources we need to survive. By putting our brains and brawn to work for the capitalist class, we create value, we create wealth. Under capitalism, the capitalist class steals and hoards vast shares of this value and leaves the people who create it with little to nothing. We build houses, care for patients, teach, cook food, clean, deliver packages, and more. But the price tag on all these goods and services is well beyond what we are paid in wages. The difference between the value we create and the wages we are paid is how capitalists make their profits—that is, by exploiting our labor. Wages represent a small portion of the value that we create and are often barely enough to cover basic necessities. In this way, capitalism is rooted in a social relationship between the many that must work for a wage—along with the unemployed and those who are too sick or elderly to work—and the few that employ and direct our labor. It is a relationship that is reproduced at every level of society by workers, managers, and bosses, within the workplace and beyond.

Wage labor is a key component of capitalism, but our ability to get up and go to work is made possible by countless hours of mostly unwaged labor. This includes all labor that goes into making and remaking people—childbirth, cooking, cleaning, healthcare, child rearing and elder care, education, and more—also known as reproductive labor, which is overwhelmingly performed by, and expected of, women. Some aspects of reproductive labor have been commodified, converted into services that can be bought and sold, but it remains largely unpaid, undervalued, invisibilized, and subordinated to the process of making profit, which requires reproducing obedient workers and citizens. In capitalist societies, the division of reproductive labor has always been racialized. For instance, Black women, as slaves, provided the domestic labor to run plantation homes, provided similar labor after emancipation, and currently account for a large segment of the home healthcare occupation.

In the process of making and remaking a class that can only survive through selling its labor, capitalism has also locked others out of the workforce altogether. Many people, who are disproportionately Black, non-Black Latine, and Indigenous, are held in near permanent unemployment or swallowed up by the prison system. Alongside the regular economy, a gray economy of marginalized workers exists, where various drugs and other products are bought and sold outside the formal marketplace. This area of the economy is frequently subjected to state scrutiny and violence. Whole towns of the US exist with generations of permanently unemployed workers, discarded by capitalism’s thirst for profit and domination.

The hierarchies of domination in our capitalist society emerged from and were shaped by prior systems of domination. Capitalism emerged as a fundamentally patriarchal institution with a male ruling class because it grew out of the patriarchal systems of domination in feudal Europe. Over the years, the dominant class’s drive for profits have led them to shape and reshape the system of patriarchy. For example, during the antebellum period, when capitalism thrived on the extreme exploitation of chattel slavery, Black women were stereotyped as being tough and immune to pain, in comparison to fragile upper class white women, so plantation owners could force them to labor in the fields as well as in the home. In this way, capitalism depends on systems of oppression to prop up its ruling class, and those systems of oppression need the power of the capitalist ruling class in order to survive.

The driving force behind capitalism is the profit motive. Capitalists invest money to produce goods and services that can then be sold to make more money. This process of capital accumulation lies at the heart of how and why capitalism operates. In their insatiable hunger for profit, capitalists are pitted against one another through the market—the labor market, financial market, and the market for goods and services—where commodities are bought and sold in exchange for money. To gain ground in this ruthless competition, capitalists seek ways to cut the cost of production, which can include replacing workers with machines, relocating production to places where workers can be paid less, bypassing costly safety upgrades at the worksite, and ignoring environmental regulations, among other measures. More money is also made by turning ever more aspects of our lives into commodities that can be bought and sold, from the water we drink to the education system.

The malignant seeds of this process were planted by waves of settler colonialism during which land, labor, and resources were stolen from Indigenous communities for incorporation into the global system of capitalist production. If this process continues unchallenged, it will irreparably devastate the life-sustaining capacity of the biosphere. This means that capitalism is unsustainable by its very nature and will continue to devastate our ecosystem if it is allowed to. Today nearly every corner of the earth has been turned into a node in the global network of investment, extraction, production, and commodity exchange, with widespread pollution, deforestation, record heat waves, and a global mass extinction event as its byproducts. The climate catastrophe that faces us is not caused by supposedly timeless, unchanging characteristics like greed or human nature, and much less so by our individual consumption patterns. Instead, it is caused by a system existentially driven to continuously expand throughout and plunder the Earth. In the pursuit of maximizing short-term profits, capitalism devalues and destroys ecological diversity, long-term planning for survival, and life itself.

Throughout its history, capitalism has coexisted with various types of states—from monarchies to social democracies—but in all its forms, the state’s primary function has been to ensure that the right conditions are in place for capitalism to thrive. The state functions as a general manager of capitalism, passing laws that protect and preserve private property, sending the police or military to break up strikes and mass protests, regulating capital flows, incentivizing some businesses over others, and facilitating the capitalist class’ pursuit of profit.

The capitalists’ efforts to increase control over work and to expand the power of the state has led to the creation of layers of managers and elite professionals in corporations and the institutions of the state. Management is a tool of repression and policing in the workplace, speeding up our work and keeping the interests of the owners as the driving force on the job. Elite professionals who dominate social institutions are the agents of ruling class hegemony. The subordination of the working class to capitalists and bureaucrats denies us control over our lives and subordinates life to the meaningless drive for profit.

Not everyone is conscious of their class position in capitalism. People often have contradictory ideas about themselves, their work, and their class, leading individuals to misunderstand their position within the class system. Dominant class ideas that justify capitalism, like the American myth that almost everyone is middle class or that anyone who works hard enough can be successful, are deeply embedded in society. Workers are sold these myths through school curriculums, social media hashtags, and in countless television shows. Capitalism creates its own ideology, and in the US it has been so successful at eliminating any alternative thinking that many people accept capitalist ideas about class as common sense instead of being aware of their own class position and interests. At the same time, the experience of collective struggle can create ideas that break from dominant-class thinking. Class consciousness does not happen automatically. It develops through struggle and ideological battle.

Imperialism

Imperialism is a system in which the state and dominant classes of some countries use their superior economic and military power to dominate and exploit the people and resources of other countries. The imperialist powers drain wealth from less powerful countries through debt, corporate investment, unequal trade relations, and military intervention.

While colonialism—the direct and total rule of one nation by another—has been eroded by popular struggle over the last century, imperialist domination and exploitation remains. The US, for example, maintains a colonial relationship to Puerto Rico, Guam, Samoa, and the Virgin Islands. For the most part however, instead of direct foreign rule, it is a nation’s own domestic dominant classes who manage imperialist exploitation on behalf of foreign imperialist states and the global economy. While there is an appearance of independence and self-rule, in reality the same relations of power remain.

Imperialism is an inherent feature of global capitalism and competing states. The international capitalist system generates competition between states, which struggle over territory and geopolitical positioning, to jockey for influence and control. Similarly, in the system of global capitalism, members of each country’s capitalist class pressure their home states to secure exclusive or semi-exclusive access to new markets and resources.

Based on their economic and military capacities, countries can be roughly categorized as core, semi-peripheral, or peripheral.[8] Within each of these categories exist further stratifications, with particular nation-states occupying either more dominant or more subordinate positions in relation to others in the same category. As well, it is important to note that the positions of and relationships between nation states are incredibly complex and not entirely static.

Core countries are exceedingly wealthy, highly industrialized, and militarily powerful, allowing them to secure access to the cheap labor, raw materials, export markets, and the goods of semi-peripheral and peripheral countries. The United States, Canada, much of Western and Northern Europe, Australia and New Zealand, and Japan, sit at the core of these global systems.

Countries on the periphery lack thoroughly industrialized economies and states with powerful militaries. These peripheral countries are targeted for exploitative access to cheap labor and resources mainly by countries at the core, and to a lesser degree, countries on the semi-periphery. The majority of countries on the African continent, in the Middle East, Southeast Asia, Eastern Europe, and in Central and South America are on the periphery.

Finally, semi-peripheral countries occupy a middle strata between the core and periphery. The semi-peripheral countries possess partially industrialized economies and relatively strong states with military capabilities. While still subject to the imperial domination of core countries, semi-peripheral countries are able to exert their own influence on peripheral countries through smaller-scale investment, access to export markets, and a degree of military power. In some cases, dominant core countries enlist states of the semi-periphery to act on their behalf as regional managers or enforcers. Countries like India, Russia, Iran, Turkey, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, South Africa, and Israel are considered semi-peripheral. While China is still typically understood to be on the semi-periphery, its rapid military and economic growth has allowed for it to project broad influence across the globe. As such, we may consider it an emerging core country.

Each country’s geopolitical position emerged not by happenstance, but by historical processes and circumstances. For example, Western Europe’s colonial domination in, exploitation of, and extraction from Africa and the Americas facilitated the former states’ growth as contemporary economic and political powerhouses at the expense of the latter. These same processes of domination and extraction also gave rise to ideological justifications predicated on the pseudo-science of race. According to this line of reasoning, Africans, Indigenous Peoples of the Americas, those on the Indian subcontinent, and others were not only deserving of the domination and exploitation they endured, but were in fact ‘beneficiaries’ of the ‘civilizing’ project that colonial powers had undertaken. It was in this crucible that modern conceptions of race and white supremacy were formed.

The United States has been the most dominant global imperialist power since World War II. US state functionaries maintain and reproduce empire through hundreds of military bases around the world, military alliances like NATO, financial bodies like the IMF and World Bank, direct military intervention and occupation, the world’s largest military budget, and covert operations to keep the global capitalist system running smoothly. The US also uses soft power to maintain its empire, like internationally distributed Hollywood films and other forms of mass entertainment, development aid, and liberal nonprofit institutions.

The systems of global capitalism and interstate competition benefit core countries, but they do so unevenly. While the working class in core imperialist countries are granted some access to benefits from the wealth extracted via dominated peripheral countries, these benefits pale in comparison to what the real beneficiaries—the capitalist class—reap. Moreover, these interconnected systems, through processes like globalization, also work to destabilize the lives of workers in core countries, as the capitalist class relocates jobs to peripheral and semi-peripheral countries in search of cheaper labor and higher profit margins.

Nationalism is one of the key ideological mechanisms that prevents dominated classes around the world from recognizing their shared position within the structure of global capitalism. Instead of identifying as members of the global dominated classes, we are taught to ignore social contradictions and instead identify with our home nation-state. This is typically achieved through the construction of a national founding myth that is consistently reinforced with symbols, songs, and rituals. Some revolutionary and popular progressive forces in colonized countries have used alternative nationalisms to mobilize the dominated classes against imperialist control. While many of these struggles successfully eliminated direct colonial exploitation, most simply replaced foreign rulers with local rulers who reconstructed their nation-states and, through global market pressure and for direct gain, integrated into the systems of global capitalism and interstate competition.

Some have argued that the world can easily be broken into two blocs: a broadly imperialist camp and a broadly anti-imperialist camp. We reject this notion on the grounds that national interests—directed as they are by a country’s dominant classes—even if they contradict those of dominant imperialist countries, do not automatically constitute an anti-imperialist program. In fact, some semi-peripheral and peripheral countries simultaneously oppose the dominance of core countries while undertaking extreme measures to suppress or eradicate popular movements at home. A genuine anti-imperialism is internationalist at its core and must side with the global dominated classes, not with the states that rule over them.

The State

The modern state as we know it codeveloped with capitalism in Western Europe and has spread unevenly to nearly every part of the world. Since its inception, the state has taken on a range of forms, from liberal democracies to military dictatorships. Regardless of its size or shape, the state is a bureaucratic-military organization made up of all the lawmaking and law enforcing institutions within a given territory—where power is concentrated in the hands of a minority ruling over and above the majority.

All states are marked by the dubious distinction of having a monopoly on violence within their borders and claim the ‘legitimate’ use of force outside of them. Through its police, courts, jails, and prisons, the state maintains social stability at home, protecting and preserving the system of domination in the interest of the dominant classes. To secure its interests abroad—whether that entails access to raw materials or cheap labor for certain segments of the capitalist class or geopolitical positioning—the state has the authority to mobilize the military in addition to other violent means.

The US state, created through the violent displacement and genocide of Indigenous peoples across North America, is a settler-colonial state. This fact has fundamentally shaped the US state’s trajectory from its birth to the present.

But the capacity of the state to exercise violence is, at least in part, dependent on its ability to maintain a sense of legitimacy in the eyes of its subjects. A purely repressive state is unsustainable. The state’s coercive role is therefore complemented and concealed by both consent and co-optation. Through the education system, political parties, mass media and other ideological mechanisms, the state seeks to foster a national consensus in which the exploited and oppressed accept the state, along with the system of domination as a whole, as common sense, as natural. By internalizing the logic of authority, we fuel the reproduction of relations of domination on a daily basis. The legitimacy of the state is also sustained by providing essential services, such as education and healthcare, which are typically a reflection of class struggle, but give the appearance of state benevolence. In this way, the credibility of the state is kept intact by cultivating an image of neutrality in the class struggle. The state is often skilled at absorbing and co-opting challenges to its authority, adopting popular slogans from social movements (e.g. “Si se puede!,” the 1 percent vs the 99 percent, Black Lives Matter), channeling mass discontent into the reformist realm of electoral politics, and hiring movement leaders to “change things from the inside,” among other tactics

The ability of the state to carry out these and other functions relies on the health of the economy, from which it takes in revenue through taxation. One of the core functions of the state is therefore to develop, protect, and promote the capitalist system. Toward this end, the state uses its police and legal system to protect private property and suppress class conflict, provides tax incentives for corporations, negotiates international trade deals with other states, promotes capitalist ideology through its schools, and so on. Given that capitalists tend to act in ways that prioritize their short-term interests at the expense of workers, other capitalists, the environment, and the economy more broadly, the state intervenes to manage the long-term interest of capitalism as a whole. Today, the state itself is one of the largest actors in the economy. As a pillar of capitalist society, the state is the shield and shepherd of the exploitative relationship between labor and capital, with the capacity for coercion looming in the background, placing it firmly in the camp of the capitalist class at the expense of the majority of the population.

But the state is not simply an instrument of the capitalist class. Although capitalists, particularly through multinational corporations, exert enormous influence over the state relative to other actors, the state retains a degree of autonomy. Political elites, for example, often make decisions in their own interest or occasionally in response to pressures from below that are not always in line with the competing interests of capital.

While the state expresses the interests of those controlling it, that does not mean that the dominant classes are always unified. As various figures and groupings take the reins of the state, they can use it to develop and transform some sectors of the economy over others and use the state as a vehicle to align and compete with other state actors. Struggles within the dominant classes, and the need for perpetual reformist co-optation to contain threats from below, make the state a shifting and contested site of power.

The state also plays a fundamental role in institutionalizing and enforcing systems of domination. Over time, the state has been central to shaping and reshaping social hierarchies, often in response to new conditions and popular movements that render tactics of control obsolete. In terms of white supremacy, this can be seen historically through the constitutional protection of slavery; the role of the US Army, courts, and congress in advancing settler colonialism; and the legalization of Jim Crow. While popular struggles damaged or eliminated many of these pillars of white supremacy, the state developed new forms to maintain racial domination, such as the ongoing militarization of the border, mass incarceration, police brutality, and imperial aggression abroad—all of which disproportionately affect people of color. As for its mutually reinforcing relationship with heteropatriarchy, for much of US history the state systematically denied basic political and economic rights to women, it has both extended and attacked access to abortion, prohibited and granted marriage equality, imposed nonsodomy laws and denied protections to trans workers and students, sided overwhelmingly with rapists in court, while the most powerful state institutions—the military, the police, congress, and the presidency—feature straight white men overwhelmingly at the top of the chain of command.

The state is ultimately an institution of minority class rule reproduced as a social relationship throughout society, where relations of domination thrive in our homes, workplaces, schools, and every other core institution in our lives.

Because it is a pillar of the system of domination, the state is not a neutral instrument that can be wielded for good or bad depending on who is at the helm. There is no hope for a free, socialist society through the capture of the state or through the creation of new states—whether by ballot or bullet—regardless of the insignia or color on the flag.

White Supremacy

White supremacy is a system of racial domination that emerged from the process of rationalizing, institutionalizing, and protecting the extractive and exploitative practices of European colonialism in the 15th and 16th centuries. The concept of “race” itself is a product of this process. It developed both as a mechanism of social control and as part of an effort to “scientifically” categorize people into a social hierarchy, attributing certain essential characteristics, traits, and behaviors to each category based on physical appearance. While these categories continue to shape our social, political, and economic life, they have no basis in biology. In other words, race is a biological fiction. Born out of a colonial context marked by the enslavement of Africans and Indigenous genocide, race and racial categories have evolved over time. But, regardless of time and place, race has been the glue of a cross-class alliance, binding the dominant classes to a segment of the dominated classes through shared identity—particularly a “white” identity—as a way to suppress class conflict.

This cross-class alliance can be traced back to the origins of race and white supremacy in the United States. In the late 1600s, elites in the British colony of Virginia invented and institutionalized the so-called white race in response to real and perceived threats to the settler-colonial order. Fearing the potential power of indentured servants—the majority of the population—uniting with free and enslaved Africans against the ruling minority of wealthy planters, colonial elites initiated a divide-and-conquer strategy. Through a series of laws and other measures, colonial elites created a range of exclusive rights and benefits for poor Europeans that were denied to Africans and Indigenous peoples. Out of this process, the social, political, and economic distinctions between “white” and nonwhite people took form, with continuities and changes over time.

While “white” people were placed in a dominant position, whiteness is not a stable category. Whiteness in particular, and the entire concept of race more generally, is socially constructed rather than based on biology. This means that whether someone gets classified as white is not defined by the quantity of their melanin or some genetic marker, but instead by complex social arrangements. This is made clear by tracing changes in who is included or excluded from these categories over time. For example, the large numbers of Irish immigrants who arrived in the US throughout the nineteenth century were not, at the time, considered white. Nativist Anglo-Americans closely guarded their white identity and the benefits it afforded them via the exploitation and domination of racialized “others.”

Over time, Irish, Italian, and other European immigrant workers were included in the cross-class alliance. Given its social and material benefits, these groups actively sought inclusion in the category of whiteness. For white elites, expanding the definition of whiteness served to head off or destabilize any possibility of multiracial solidarity among workers against the common forces of domination and exploitation that they faced in the fields and factories of a growing capitalist economy.

While the boundaries of whiteness have expanded or contracted depending on historical circumstances, membership in the cross-class alliance has always come with a wide range of benefits. The overall sense of superiority and entitlement among those within the dominant group has been nurtured by the fact that, relative to working-class people of color, those considered “white” have had lower unemployment rates, more wealth, better access to quality healthcare, housing and schools, lower incarceration rates, and safer neighborhoods. Though these benefits are not accessible to all “white” people equally, the elite few have tried to tether the interests of the “white race’s” working-class majority to a racial capitalist project at the expense of class solidarity from below. This can be seen in the past and present—in the defense of slavery, Indigenous genocide, and Jim Crow; in the recurring nativist assaults on immigrants; and in support for US imperialism. Meanwhile, the few at the top of the cross-class alliance, who own and control nearly every major institution in our society, continue to reap the benefits of a divided working class.

The shape of race and white supremacy at home has always been fueled by imperial conquest abroad. Beginning with the colonization of North America to the more recent invasions and occupations of the Middle East, US imperialism has always been rooted in the construction of a foreign “other,” labeling mostly nonwhite peoples and nations as both inferior and a threat to the empire. The consequences of this “othering” can be seen in the boarding schools for Indigenous peoples, the mass internment of Japanese citizens during World War II, and the racial profiling and attacks against Arabs, South Asians, and anyone perceived to be Muslim in the US during the so-called “war on terror.”

The persistence of white supremacy is propped up by both the state and capitalism. Through the labor market, capitalists have disproportionately relegated working-class people of color—particularly Black people—to the lowest paying jobs with the least amount of benefits and security, leaving many chronically underemployed and subject to rampant state violence and incarceration. To prop up racialized class oppression, US politicians and state administrators have constructed the largest and most elaborate carceral system in human history, serving to permanently warehouse more people per capita than any other nation-state. As well, nativist and white supremacist ideology and forces militarize internal and external borders against the specter of immigrants, while simultaneously enabling the economy to thrive on their hyperexploitation.

While white supremacy endures, today’s dominant classes are increasingly diverse. The racial and gender composition of the dominant classes reflect decades of struggle against white supremacy. Despite this representation, the majority of people remain trapped in a highly racialized class system, as evidenced by racial income stratification, prison demographics, and other markers of an ongoing white supremacist reality. These facts should caution us from relying on any reductive analysis that focuses wholly on identity or wholly on class as the locus of domination. Instead, we assert that race, class, and other forms of domination in the United States are intrinsically connected with each other, affecting different groups of people differently depending on time and place.

Heteropatriarchy

Heteropatriachy is a system in which gender and sexuality are shaped by structures, relationships, and ideologies of domination in ways that place men in general, and straight cisgender men in particular, in a position to exploit, oppress, and dominate women and LGBTQ people.

From birth onward, gender socialization occurs in our homes, schools, workplaces, and every other social institution we interact with throughout our lives. These institutions inscribe heteronormative beliefs, values, norms, practices, and expectations around sex and gender. This includes dominant understandings of what it means to be a “man,” “woman,” “straight,” or “gay,” as well as narrow definitions of what is considered “masculine” and “feminine.” These and other categories related to sex, gender, and sexuality are not natural, timeless, objective facts. Both gender and sexuality are socially constructed. They are defined differently depending on time, place, context, and social struggle, and can have life-affirming or life-threatening connotations or consequences depending on the circumstances.

The social structure of heteropatriarchy situates heterosexual cis men in a position of dominance. Under heteropatriarchy, heterosexuality is viewed as the normative sexual orientation, the man-woman-child structure is understood as the standard family form, and male and female are seen as two mutually exclusive, binary, and unchanging genders that are determined at birth by physical “sex” characteristics.

Heteropatriarchy has a symbiotic relationship with other forms of domination. As part of the legacy of slavery and settler colonialism, for example, white men continue to dominate the highest paying occupations in the US, while Black and Indigenous women are overrepresented in low-wage jobs with little if any benefits. The state and capital have played a central role in creating and sustaining this racialized and gendered segregation of the labor market to maintain a cheap source of labor. In relation to the coercive function of the state, Queer and trans people, particularly those of color, are disproportionately policed, arrested, and imprisoned. Meanwhile, imperial ventures, such as the US invasion and occupation of Afghanistan, are often justified by political elites on the grounds of “liberating” women in the service of empire building

One of the pillars of heteropatriarchy is the gendered division of socially reproductive labor. In capitalist societies, men are more often encouraged to do “productive” manual and intellectual labor. Women, on the other hand, are pushed to serve the needs of social reproduction, the process of making, caring for, and socializing the working class to develop its willingness, capacity, and disposition to continue selling its labor for a wage. Within heterosexual households, women still do the large majority of unwaged housework, usually working a “double shift” where they go to work to generate profit for capitalists and then go home to cook, clean, and take care of children, the elderly, and even their spouses—all of which is needed for workers to be able to go back to work the next day and for the next generation to enter the ranks of the working class. In the workforce, women are often tracked into positions of care and service to others—including teaching, healthcare, and other service occupations, which are overall less valued and less secure than traditionally male occupations. Social reproductive labor is not only essential for facilitating waged labor, but is also a key part of the process of instilling the gender norms and roles that underpin heteropatriarchy.

Heteropatriarchy expresses its clearest and most brutal form through the rampant violence inflicted upon women and LGBTQ people. Gender violence comes in various forms, from intimate partner violence at home, to sexual harassment at work, to femicide in the streets and rape as a weapon of war in combat zones. Gender violence is enabled by hierarchical power relationships. In our workplaces, families, schools, and other social institutions, cis men overwhelmingly occupy the position of boss, landlord, policemen, prison guard, and others with the structural power to prey on those who depend on them for work, housing, safety, and other necessities. Cultural norms, managers of capitalist enterprises, and the state’s alleged justice system protect and perpetuate the cis men who perpetrate this violence, using shame, rejection, disbelief, and other insidious tactics to ignore and silence the victims and survivors of gender violence. In times of crisis or in reaction to advances in feminist struggle, gender violence is often amplified, weaponized by men who fear that their masculinity and dominance is being threatened. However, gender violence is not exclusively carried out by cis men. People of various gender identities use violence and other forms of domination to enforce the norms and roles proscribed by heteropatriarchy. Ultimately, gender violence is an extension of the broader violence inherent to the system of domination.

Heteropatriarchy is also profoundly harmful to men. Throughout their life, men are socialized to suppress their emotions and defer support in order to appear strong—behaviors that contribute to higher rates of depression, drug abuse, violence, and suicide. Boys and men are under constant pressure to uphold narrow notions of manhood and masculinity. Homophobia and misogyny are regularly weaponized to keep boys and men in line. They are told: “man up,” “don’t be a bitch,” “no homo,” or that “men don’t cry.” While these norms and behaviors are either unattainable or undesirable, men who are perceived to be defying them, especially gay and trans men, are often subject to violence. Though heteropatriarchy provides benefits to men by placing them in a dominant position within the social structure, it ultimately prevents them from realizing their full potential as human beings.

The shape of heteropatriarchy is not fixed. The dominant classes today, while still overwhelmingly composed of heterosexual cis men, are increasingly made up of women and queer people. Through the advance of liberal assimilationist politics and identity-based struggles, the hard social borders of heteropatriarchy have become more porous. Some sections of oppressed groups have become members or junior partners of the dominant classes. This fact requires us to deepen our analysis beyond liberal identity politics, while also continuing to recognize the particular social positions that women and queer people occupy.

Although the dominant classes play a crucial role in maintaining the basic structures of heteropatriarchy, they are reproduced and reinforced on a daily basis by all of us who have grown up surrounded by this inescapable, poisonous, and dominant ideology. Thus sexism, transphobia, and homophobia are things that are very much present within working-class organizations and within our own political organizations. They threaten to undermine working-class power if they are not consistently recognized and challenged.

Settler Colonialism

The United States was built on the genocide of Indigenous peoples. Beginning in the late fifteenth century, European royal houses sought to enrich themselves by funding and encouraging traders, soldiers, and missionaries to violently clear the Indigenous populations of what we now know of as the Americas, take and occupy the land, and construct permanent settler societies on Indigenous territories.

This ongoing process of settler colonialism differs from other forms of colonialism, which are predicated primarily on the extraction of raw materials and the exploitation of Indigenous populations in the interest of direct material gain or market expansion. Under classic forms of colonialism, these activities are carried out by an impermanent population circulating between the metropole (the home country) and the colony. In settler colonialism, these functions still play an important role, but are subordinated to the more fundamental project of introducing a permanent population whose aim is to uproot the lifeways of Indigenous peoples so as to replace them with new social, political, juridical, economic, and religious structures. Ultimately, the settler colony aims to supplant existing Indigenous populations through a combination of genocidal elimination and assimilation.

Land theft is necessary for the establishment of a settler-colonial society. Recognizing the moral contradiction present in violently dispossessing people from their land, European and US settlers relied on a number of justifications to reach their intended ends. These included the familiar practice of casting Indigenous peoples as racially or culturally inferior, but also weaponizing the legal-political notion of terra nullius, which viewed “empty” lands as free to those who would put them to “legitimate use.” Settlers carved these lands into discrete parcels to be owned solely by individuals or groups of individuals, thereby introducing a regime of private property.

It was precisely this rapacious drive to acquire ever more territory that sparked the revolt of settler colonists in North America against the British Crown. After securing its independence, the newly sovereign United States acted to remove all previous restrictions on internal territorial expansion. The rapid westward advance that followed the war placed major demands on the fledgling federal government, requiring it to quickly expand its military and policing capabilities. It’s in these dual crucibles—the war of independence and the rapid expansion of territories—that an early version of the modern US settler-colonial state would be forged.

The nineteenth century saw the United States continue to expand its territory through annexations, wars, and transactions with other nation-states. Throughout this period the federal government and vigilante settlers alike sought to liquidate Indigenous populations using a variety of means. Violent incursions into Indigenous territories remained a key method, but new practices also emerged. The dual introductions of the Indian Removal Act and the Indian Appropriations Act resulted in a systematization of forced removal and the creation of the modern reservation system. The latter part of the century also saw a ratcheting up of efforts to fully assimilate Indigenous peoples into settler society by stripping them of their relationships to land, language, spirituality, cultural practices, and one another. Among other measures, this involved the creation of hundreds of private and state-funded “boarding schools” into which Indigenous children were enrolled after having been separated from their families and communities. These schools aimed, according to one of their chief architects, to “kill the Indian...and save the man.” The practices of state-backed coerced assimilation continued well into the twentieth century, during which the federal government produced new and more complex schemes aimed at fully dissolving the identity and culture of Indigenous peoples.

While Indigenous peoples have struggled mightily to retain their lifeways and very existence, from the Powhatan Uprising of 1622 to more recent struggles around the Dakota Access Pipeline, settler-colonial domination continues to this day. In our moment, as in moments of the past, it manifests in ongoing conflicts over Indigenous lands, waterways, treaties, and autonomy; denigration, misrepresentation, and the near absence of Indigenous people in popular media; state attempts to withhold recognition of certain Indigenous tribes and their rights; and the systematic degradation of life for those living in the reservation system through the denial and mismanagement of state resources.

Ultimate Objective

Introduction

So far, we have analyzed the general structures, relationships, and mechanisms of domination that give shape to the society in which we live. Now we will establish our prescription for uprooting these structures—social revolution—and describe in broad terms the form of social organization that we are struggling to bring into existence—libertarian socialism.

Social Revolution & Libertarian Socialism

The urgent need for a radical transformation of the world we live in is obvious to anyone who examines it with clear eyes. From pandemics and ecological devastation to endless war and rampant social, political, and economic inequality—the weight of overlapping crises is impossible to ignore. These conditions are the products of a deeply entrenched system of domination, a complex system with many faces: capitalism, the state, white supremacy, settler colonialism, heteropatriarchy, and imperialism.

This system will not be petitioned, voted, lobbied, or peacefully swept out of existence. The dominating classes, its primary beneficiaries, seek to ensure its stability, expansion, and reproduction. They have used and will continue to use all means at their disposal, including violence, to defend their interests. As such, no dramatic reorganization of society will be permitted to advance so long as those who benefit from the current social order stand in the way. A violent confrontation between the dominating and dominated classes must take place in order to destroy the system of domination and clear the way for a new world. That is, we need a social revolution.

Unlike a political revolution, which seeks to capture state power and transform society from the top down, a social revolution involves completely transforming society from the bottom up. This wholesale transformation entails both destruction and creation. When the organized forces of exploited and oppressed people overcome the forces of reaction in a violent rupture with the status quo, this is the destructive dimension of social revolution—the collective uprooting of all the social, political, and economic structures as well as the relationships and mechanisms of domination that maintain them.

In particular, social revolution includes the immediate abolition of the state, with all its lawmaking and law-enforcing institutions (the police, courts, military, prisons, government, etc.); the expropriation of all wealth hoarded by the capitalist class; the abolition of private property; a radical change in cultural norms and values; and ultimately the elimination of social classes and all forms of domination, from white supremacy and colonialism to patriarchy and transphobia.

The transformation of the old world of capitalist domination to the new world of libertarian socialism will feature a period of fast-paced revolutionary rupture where masses of people move into action and break the chains that have held us in stasis. However, common romantic notions of revolutionary upheaval aside, history teaches us that this will not be a single, neatly contained event following an easily predictable sequence.

Still, a revolutionary rupture will be qualitatively different from the limited open conflict—riots, strikes, and uprisings—that are continuously produced by the fundamental antagonisms at the heart of our society. These small explosions in class struggle are extremely valuable for their ability to expose structures of domination and exploitation, to help us develop our strategy and tactics, and to sometimes produce short-term gains. However, without patient preparation, organization, and a well-devised strategy, these conflicts tend to generate only limited and uneven outcomes, falling short of a total break with the status quo.

A true revolutionary rupture becomes viable when the dominated classes have built up the capacity for force necessary to destroy the total system of domination. The accumulation of this capacity for force—what we call popular power—hinges on a long-term process of building and uniting independent social movements from below, together with anarchist political organizations, into a broad front aimed at upending current social relations.

In the chaotic midst of a revolutionary rupture, there are likely to be various political parties and organizations that attempt to co-opt the struggle under the guise of acting “on behalf of” the masses. For this reason, anarchists must have a strong presence within the social movements leading the struggle, both to spread our values, principles, and practices, and to prevent opportunist and reformist forces from manipulating a revolution to their own narrow ends.

Though the specific events of a future revolutionary rupture are impossible to predict, we can say with great certainty that the dominating classes will not hesitate to violently suppress any revolutionary movement that poses an existential threat to the system of domination. To defend the social revolution, popular self-defense groups will need to be formed. These must be democratically organized and accountable to, controlled by, and drawn from federated mass organizations such as worker’s councils and community assemblies.

Examples of these types of defensive formations can be seen in revolutionary situations throughout history: the radicalized National Guard sections that defended the Paris Commune, the Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine, the worker militias of the Spanish CNT-FAI, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, the People’s and Women’s Defense Units of Rojava, and so on. While the defense of our struggle will necessitate violence, any application of force must seek to end systems and manifestations of domination, not reproduce them with a different set of rulers.

While we’ve established the general means by which we intend to uproot the whole system of domination, this alone is not sufficient. As Italian anarchist Errico Malatesta once noted, “in order to abolish the ‘gendarme’ and all the harmful social institutions, we must know what to put in their place, not in a more or less distant future but immediately, the very day we start demolishing.” Thus, in parallel with the destruction of the old order, we must build a new one in its place.

In place of the current system of domination, we believe that a system of libertarian socialism is needed to allow human society to reach its fullest potential and to ensure a sustainable future for our planet.

A libertarian socialist society is one that has eliminated the state, social classes, and the need for markets and money. Though we cannot predict its every facet, we expect a libertarian socialist society to include:

-

Collective democratic ownership of the land, machinery, and tools used to produce everything society requires to sustain and reproduce itself. This would replace the current regime of private property.

-

An economy where the production, consumption, and distribution of goods and services are rooted in ecological sustainability and on the principle “from each according to ability, to each according to need.”

-

Self-management of workplaces and communities, where we would have a say over the decisions that affect our lives in proportion to the degree that we are affected. Workplace and community assemblies would be linked together from the bottom up through a system of federations on the local, regional, and continental levels, replacing the top-down governing structures of the state with direct democracy.

-

Collective economic planning to replace the cut-throat competition of wasteful, profit-driven markets with a directly democratic and cooperative system of producer and consumer councils that will decide what goods and services to produce, how to produce them, how much of them to produce, and how to distribute them.

-

Global solidarity and cooperation between regional federations to replace the system of imperial domination, nationalism, and interstate competition that currently governs the globe

-

Sexual and gender liberation, where complete freedom of expression in gender and sexuality, along with an equitable distribution of social reproductive labor, become the norms replacing the current system of heteropatriarchy.

-

Liberation for Black people and all people of color through the abolition of white supremacy, so that race can no longer be used as a tool to create social hierarchies.

-

Decolonization, including the recovery of all indigenous territory and resources to ensure their full cultural, spiritual, and material well-being and the reconstitution of Indigenous communities, practices, languages, and knowledge systems.

-

A system for the redress of social conflict and harm that is rooted in restoration, transformation, and need rather than punitive ‘justice’ and incarceration.

With the elimination of many jobs that contribute nothing useful to society (like marketing, banking, large layers of management, etc.), the automation of many other tasks by putting technology at the service of human need rather than profit, the stability of guaranteed socialized housing instead of precarity enforced by landlords, and a reduction in stress from no longer having to contend with the daily pressures of rigid gender roles and racism, life in a libertarian socialist society will feel incredibly different from our current experience. We will have more control over our lives, more free time to pursue our passions, the freedom to perform labor that benefits our community, and the liberty to individually express ourselves in ways that we might not even know are possible now.

It is impossible to know the specifics of how, if, or when the dominated classes will bring libertarian socialism into being—whether it will be created in one area and spread, emerge unevenly across a network of regions, or through a large-scale collapse of the established order. The creation of a libertarian socialist society is a necessity given the crises we face, but it is not inevitable. The likelihood of its success and survival is tied to the combined strength and determination of militant mass social movements and anarchist political organizations committed to achieving this objective through worldwide social revolution.

General Strategy

To guide us through the highs and lows of struggle along the path toward our ultimate objective—social revolution and libertarian socialism—we need a compass to keep us aligned with our North Star. In other words, we need a general strategy, a durable revolutionary orientation aimed at both dismantling the system of domination and laying the groundwork for a new society.

In broad terms, strategy is the means that we adopt to achieve our ends. It can be framed in short-term, medium-term, and long-term plans. To put our strategy into practice, we need to develop a set of tactics—concrete steps that create a coherent link between our means and ends.

Whereas short-term strategy is defined by current conditions within a particular location and period of time, general strategy is not limited by time and place. Instead, it is informed by a structural analysis of society, the future society we aim to build, and how we plan to get from the old world to the new. General strategy is the overarching framework that guides our political organization and its militants. It is the bridge between the short and long term, the glue that binds our means and ends.

According to the Federação Anarquista do Rio de Janeiro (FARJ) in Brazil, “it is essential that the specific anarchist organization works with a strategy”[9] to ensure that its militants are “rowing the boat in the same direction.”[10] A general strategy, developed through collective discussion and decision-making, allows the organization to mobilize its limited resources in a common, cohesive direction to enhance its effectiveness.

Adopting a general strategy also limits the confusion, conflict, and inefficiency that crops up when individuals or groups within the organization operate at cross-purposes. As the FARJ notes, “it is not possible to work in an organization in which each militant or group does what they think best, or simply that which they like to do, believing themselves to be contributing to a common whole.”[11]

For these reasons, a general strategy is necessary.

Our general strategy is rooted in the anarchist tradition of building popular power, which can be traced back to the Federación Anarquista Uruguaya (FAU) and the historic social and political struggles of the 1960s and 1970s in South America. The FAU’s articulation of a specifically anarchist strategy for building popular power, crystallized in the call for creating “a strong people,” has inspired sister organizations in and outside the Southern Cone.[12] At the heart this strategy lies the leading role of social movements , which can be understood as “an association of people and/or of entities that have common interests in the defense or promotion of determined objectives....These movements can be in the most different places in society and have the most different banners of struggle that show the needs of those around the movement, a common cause.”[13]

Throughout its history, the United States has seen a wide range of inspiring social movements carrying various “banners of struggle,” from the movement for abolition to the labor, tenants, farmer’s, feminist, LGBTQ, indigenous, student, immigrant rights, Chicano/a, environmental, anti-war, Civil Rights, and Black Power movements. It is through these movements that we have seen some of the most dramatic changes in our society, from the dismantling of Jim Crow segregation to the end of child labor.

Our general strategy stems from the recognition that only social movements have the potential for revolutionary transformation, for sowing the seeds of a new society. We can see glimpses of this revolutionary potential in the past and present internationally: in the self-governing territories of the Korean People’s Association in Manchuria during the late 1920s and early 1930s, in the thousands of socialized fields and factories of Spain during the Spanish Revolution, in the liberated territory of Morales and elsewhere during the Mexican Revolution, in the mass movements of Uruguay in the 1960s and 1970s, in the soviets and communes of Ukraine and Russia during the initial years of the Russian Revolution, and in the liberatory struggle in Rojava today.

But the revolutionary potential of social movements is not a given. Many, if not most, movements are drawn toward reformism, seeking to change the “excesses” of the system of domination, not the system itself. These movements, or at least the leadership shaping their direction, see reforms as ends in themselves.

Movement organizations oriented toward reformism tend to reflect many of the values, beliefs, and practices of the system, including but not limited to: hierarchical management structures with top-down models of decision-making and a thick bureaucracy, an emphasis on electing and collaborating with reform politicians to carry out change through the state on the movement’s behalf, and promoting individualism and competition by boosting the public profile and salaries of movement leaders.

The tactics and strategies of reformist politics often mirror the needs and interests of the social forces at its core, including union bureaucrats, non-profit executive directors, and progressive politicians. For these forces, the organization itself—the union, nonprofit, or political party—is the source of their livelihood and way of life, from their generally generous salaries to their social and political networks. Therefore they are unlikely to pursue tactics or strategies that may put the organization in jeopardy, such as illegal strikes or other forms of mass disruption that could elicit repression from the state. Instead, reformist currents within movements are more likely to promote change through official channels. Lobbying, advocacy, election campaigns, symbolic demonstrations, and press conferences are some of the typical tools of reformism.

Although we reject reformism, struggling for reforms is essential—when they are won from below instead of granted from on high by landlords, bosses, or politicians. Winning reforms through independent collective action, for better living and working conditions, builds our capacity, solidarity, initiative, and will to fight. The struggle for reforms is critical for building popular power.

Inspired by a libertarian socialist horizon, our general strategy calls for building popular power through independent, durable social movements that can not only wrest reforms from the dominant classes but lay the basis for a new society. These movements are characterized by a distinct set of organizational forms and modes of struggle:

-

Organized around shared needs : As opposed to activism, in which individuals engage in cycles of moral outrage, bouncing from one issue to the next without building a social base, we call for movements that struggle around our shared material needs and interests. Organizations grounded in the common needs of exploited and oppressed peoples—such as higher wages, rent control, childcare, cop-free schools, etc.—have more potential for building a broad social base with the capacity to not only improve our living and working conditions, but to become levers of revolutionary change

-

Non-ideological : Instead of building movements aligned with a particular political party or marked by an explicit political ideology—whether it be anarchist, Marxist or social democratic—we call for movements that are mobilized around common material needs and interests. We recognize that mass movements have a variety of ideological currents within them and that attempts to impose a singular political affiliation tends to narrow their social base.

-

Class struggle & independence : In opposition to class collaboration with the forces of domination, we advocate movements that maintain independence from the state, political parties, nonprofits, and other impediments to waging class struggle. This avoids the pitfalls of co-optation, demobilization, and domestication.

-

Direct action: Rather than delegate the resolution of our struggles to others—whether they be politicians, union bureaucrats, or nonprofit staff—we call for mass collective direct action as the most potent mode of struggle for movements. When masses of dominated peoples refuse to work, withhold their rent, or take over and start running social institutions themselves, we bypass intermediaries and take the reins over the problems that we face and the solutions we propose. This develops the self-confidence, skills, and autonomy of the dominated classes.

-

Direct democracy : As opposed to top-down organizations or representative democracy, where decision-making power is concentrated among a handful of people at the top, movements seeking to build popular power practice direct democracy. This ensures meaningful, broad-based participation and democratic control by the rank-and-file, where everyone involved has an equitable say in a collective decision-making process, whether decisions are made through voting, consensus, or modified consensus.

-

Self-management & federalism: Instead of organizations with a rigid chain-of-command and divisions between leaders and led, we advocate self-managed movements, democratically organized and controlled by the rank-and-file, where members have a say over decisions to the extent that they are affected and movements are scaled up and linked together through a bottom-up, federalist structure.

-

Militancy: Rather than limit ourselves to the official channels for change, which are designed to keep us passive and reproduce the system, we need militant movements that place an emphasis on direct action, a willingness to engage in mass civil disobedience, including illegal strikes, sit-ins, occupations, and other disruptive tactics that pose a meaningful threat to business and politics as usual.

-

Solidarity & mutual aid: As opposed to movements that are confined to a particular site of struggle, we need social movements rooted in solidarity and mutual aid. We need to stand with all exploited and oppressed peoples in our common struggle against the entire system of domination. We need to support, defend, love, and protect one another.

-

Internationalism: Instead of limiting our struggles to the country we happen to be living in, we reject nationalism and call for internationalist movements that stand in solidarity with all exploited and oppressed peoples at home and abroad to combat global capitalism, imperialism, and the nation-state.

-

Revolutionary culture : We must oppose the values and practices of the dominant culture—individualism, competition, heteronormativity, racism, etc. Instead, we need to foster a revolutionary culture in our movements and organizations that cultivates cooperation, solidarity, internationalism, anti-racism, feminism, and similar practices, both in the way we structure our organizations and relate to one another as well as through art, education, and other forms of communication.

Many of these elements will likely be missing from the movements we encounter, assuming there are movements to be found in the first place. However, whether we get involved in existing struggles or build new ones from the ground up, our role as anarchist revolutionaries, as a political organization, is to practice, propose, and defend these elements through active participation in the daily struggles of the dominated classes. The more these characteristics are present in social movements, the more we are advancing the strategy of building popular power.

This brings us to the question of dual organization, a pillar of our general strategy. Since its origins in the late 19th century, anarchism has always had a dual organization current, which advocates the need for two separate but symbiotic types of organization as key ingredients for revolutionary transformation—one social/mass (social movements and mass organizations) and the other political (anarchist political organizations).

The theory and practice of dual organization—associated primarily with political organizations in the mold of platformism[14] and especifismo[15]—not only highlight the need for both social and political organization, but also the unique role played by each, and the relationship between the two.

As part of our general strategy, anarchist militants must build, strengthen, and participate in both types of organizations. Let us explore some of the core characteristics of each.

Mass organizations bring together particular actors of the dominated classes—workers, tenants, students, immigrants, indigenous peoples, etc.—on the basis of defending or improving their immediate conditions. As we have described above, these organizations exist in many forms, from labor unions in the workplace to indigenous organizations in defense of their lands. Since mass organizations strive to unite as many people as possible to address their material needs, they tend to emphasize reforms, not revolution. As the Zabalaza Anarchist Communist Front in South Africa explains: “(t)he mass organisation does not require a complete vision of the broader class struggle, only a practical capacity and a desire to fight capital. In non-revolutionary times it is concerned with the immediate day-to-day struggles and concerns of the working class, and is not necessarily revolutionary.”[16]

Bringing together large numbers of people based on common needs, not ideology, mass organizations can hold a wide range of perspectives among their members. These perspectives can sometimes overlap or be in conflict, contradiction, or competition with one another. Participants in mass organizations can include those who support the Democratic or Republican Party, conspiracy theorists, people without a clearly defined political identity, various strands of Marxists, misogynists, religious reactionaries, liberals, and everything in between. The ideological diversity among the rank-and-file of mass organizations means we must engage in the “battle of ideas.”

Anarchists must be prepared to intervene among the different forces at play within mass organizations, winning as many people over to our ideas and methods as possible. To intervene most effectively, however, we need to be organized politically.

Unlike mass organizations, which are generally open to all those who share certain needs, anarchist political organizations are composed of an “active minority” of revolutionaries who share a common ideology, set of principles, and program. Political organizations demand a higher degree of theoretical and practical unity from their members and play a distinct role in the course of struggle.

The most critical role of an anarchist political organization is sustained activity within social movements. Militants are expected to commit to organizing within one of several “sectors” where social movements are grounded. Sectors are specific sites of struggle where the battle between contending classes tends to take concrete form, such as workplaces, schools, and neighborhoods. According to Chilean anarchist José Antonio Gutierrez, class conflict within these sectors is expressed through particular “actors of struggle”—workers, students, tenants, incarcerated, etc.—who are defined by:

-

Problems that affect them immediately and their immediate interests, including police brutality, unsafe working conditions, dilapidated housing, incarceration, and more.

-

Traditions of struggle and organization sprouted from this set of problems and interests , such as labor unions, tenant unions, indigenous organizations, immigrant rights organizations, among others.

-

A common place or activity in society, including workplaces, neighborhoods, schools, prisons, reservations and more.[17]

Sectors are not understood in isolation. Each one is shaped by and also shapes the system of domination. They are all interconnected. Our ability to pay rent, for example, is tied to how much we are paid at work, which is often related to our level of formal education, but also questions of race, gender, nationality, and sexuality. Historically, social movements are at their strongest when they are able to weave together and mobilize multiple sectors. The Civil Rights and Black Power movements of the 1960s and 1970s are a case in point. These movements included mass organizations in workplaces, schools, neighborhoods, and prisons as part of a broad-based struggle. Thus, our task is not simply to build power in one sector alone but to find ways to unite multiple sectors into a mass movement from below against the system of domination.

We identify which sectors to commit to as a political organization not based on personal preference but on a collective analysis of current conditions, an assessment of which sites of struggle have the most potential for building popular power, and our capacity as a political organization.

Through long-term engagement, relationship-building, and principled organizing, anarchist militants can not only participate in mass organizations within these sectors but influence their everyday practice and orientation in an anarchist direction—a process known as social insertion.