Erica Lagalisse

Occult Features of Anarchism

First Premises: The Theology of Politics

A Heretical Account of the Radical Enlightenment

The Revolutionary Brotherhoods

Theosophy, the Dialectic, and Other Esoterica of 19th Century Socialism

Abstract

By exploring the hidden correspondences between classical anarchism, Renaissance magic and occult philosophy, this chapter advances the critical study of Left-political attachment to the ‘secular’, wherein Western anarchist and socialist cosmologies have been mystified. By historicizing Western anarchism and ‘the revolution’, it highlights the development of Left theory and praxis within clandestine masculine ‘public’ spheres of the radical Enlightenment, and how this genesis proceeds to inflect anarchist understandings of the ‘political’. Inspired by ethnographic research among contemporary anarchist social movements in the Americas, this essay questions anarchist ‘atheism’ insofar as it has posed practical challenges for current anarchist-indigenous coalition politics. Moreover, in its treatment of ‘secret societies’ this essay has pedagogical utility for today’s political activists as well as scholars of anarchism. Where popular fear of ‘secret societies’ is widespread, charting the construction of the secret society in European history has practical political importance. By attending to this history, we also witness the co-evolution of modern masculinity and secularized social movements as a textured historical process, and observe the privatization of both gender and religion in the praxes of radical counterculture, which develops in complex dialectic with the “privatization” of gender and religion by the modern nation-state.

Introduction

Let us explore the hidden correspondences between classical anarchism, Renaissance magic and occult philosophy, and other hidden features of anarchism besides. Let us historicize Western anarchism, whose genesis within clandestine masculine ‘public’ spheres of the radical Enlightenment continues to inflect anarchist understandings of the ‘political’ even today. As I have related in my previous work concerning the exclusion of indigenous women and their concerns from anarchist public spheres, anarchist “atheism” can pose practical problems for current anarchist-indigenous coalition politics: our concern is beyond academic.[1] By illustrating the cosmology of classical anarchism I hope to complicate present-day anarchist attachments to “secular” analyses, in which anarchist theology is simply displaced and mystified. By attending to the same story, we witness the co-evolution of modern masculinity and secularized social movements as a textured historical process. We observe the privatization of both gender and religion in the praxes of radical counter-culture, which develop in complex dialectic with the “privatization” of gender and religion by the modern nation-state (as above, so below).

Given its topic, this essay also necessarily engages with the history of “secret societies”, wherein I have crafted my treatment to have pedagogical utility for today’s political activists, as well as scholars of anarchism. Popular discussion of “secret societies” is currently widespread in the English-speaking world (and beyond), such that charting the construction of the secret society – both real and imagined – in European history arguably has practical political import, beyond being required for the particular academic task at hand.

It is therefore explicit that I come to the historical work at hand methodologically as an anthropologist, and for the purposes of practical intervention within social movements and politics today. It is from being a participant (2000–2005), and later ethnographer (2005–2015), within contemporary anarchist social movements myself that I consider it important to unpack the history of “anarchism”. While charting instances of “anarchy” throughout time and space is a valid political project, there is also much to be gained by charting the emergence of “anarchism” as a distinct “ism” – and to do so does not necessarily detract from the aforementioned project, but rather keeps us honest as we proceed.[2]

I thus purposefully engage the past from the perspective of the present, tacking back and forth between diverse times and places to unearth bits and pieces of buried anarchist history based on an ethnographic imagination, using both secondary and primary sources. The interdisciplinary activity necessarily involved in such a project means that diverse specialists will be inspired, hopefully, to add some qualification, and thus lend their own knowledge and methodological strengths to the problem. Strangely, or perhaps not so strangely, the particular metaphysics of modern anarchism and its relation to social and historical context has not so far received the attention it deserves. This is no doubt partially due to the bias of many anarchists against religion, and the bias of many scholars against anarchism, but is perhaps also because the topic requires delving into the relationship between anarchism, occult philosophy and “secret societies” – all charged topics, even independently.

First Premises: The Theology of Politics

Carl Schmitt’s general point that modern politics embodies secularized theological concepts is of basic relevance here. Schmitt also remarks, while pursuing his particular question regarding sovereignty, that every political idea “takes a position on the ‘nature’ of man”, presupposing that “he is either ‘by nature good’ or ‘by nature evil’”, and that to “committed atheistic anarchists, man is decisively good”.[3] This essay will dovetail with Schmitt’s summary remark in only some ways; for our purposes a more nuanced discussion of the transcendence vs. immanence of divinity in the history of ideas within Western philosophy is crucial. I am inclined to point to Marshall Sahlins’ work on The Native Anthropology of Western Cosmology.[4] Sahlins suggests that the theological preoccupations underlying European political theory and science can be traced back at least as far as St. Augustine, and the quarrel among Pagan, Platonic, and Gnostic positions with that of the emerging Church authorities regarding the transcendence versus immanence of divinity, i.e. whether nature and humanity, whether together or separately, are wholly, partially, or latently divine, or are merely borne from the divine.

Cast in Sahlins’ light, the persistent dualist conundrum in Western politics and social theory appears as a spiraling repetition of this same theological concern: There is Lust, which is not of God; there is Matter, distinct from Spirit; there is Desire, as opposed to Reason. Those who suggest some coercive force stops (or must stop) us from pursuing our “animal” desires follow the logic of a transcendent divinity. Since we are by nature so evil and base, God – or something else “out there” conceptually derived from Him – must keep us in line. For St. Augustine it was the State of Rome, for Hobbes any Sovereign will do (his “self- interest” clearly evolving from Augustine’s “desire”). The “ individual” vs. “society” polarity evident in most social theory is only another manifestation of the same – here God becomes “society” (rather than “the State”). One could go further and point out, for example, that in Durkheim’s work the transcendent force appears as the “social fact” – from a mass of pre-social individuals and desires emerges “society” which then serves to restrain these desires. Furthermore, note that in methodological individualism desire creates and governs society, whereas in cultural determinism desire creates the society that then governs desire, but it is always the same terms in play. In short, the transcendent God of theological dualism can be found just beneath the surface of every argument for centralized authority, including most canonical social theory (which anarchists, we may note, tend to recognize as “authoritarian”).

What if we approached modern “anti-authoritarianism” with the same lens? I propose that a particular theological thread likewise runs through it. The same cultural baggage in tow, developing in dialectic with its opposite, modern anti-authoritarianism grapples with the same theological dilemma, yet attempts to resolve it differently by rearranging the terms and with recourse to various pagan traditions and syncretic Christian hereticism itself. In other words, whereas many have located “anarchist” elements in Christian millenarianism and non-Western traditions, I wish to draw attention to the latter as elements of “anarchism” itself. Modern anarchism has never been purely atheist except in name, and rather develops based on overlapping syncretic pagan cosmologies that behold the immanence of the divine. In fact, utopian socialism, anarchism and Marxism each rely (in ways both similar and different, which I will tease out below) on a specific syncretic cosmology that is incipient in the Middle Ages, changing and crystallizing in the Renaissance, and gradually given a scientific make-over throughout the Enlightenment up to the 20th century. Just as the secularization of the modern state privatizes religion but continues to embody a particular theology in its structure and ideology, the social movements that resist this dominant power structure go through a similar process of secularization in parallel, wherein gender and religion are displaced from “politics”.

A Heretical Account of the Radical Enlightenment

Standard histories of modern anarchism often locate its precursors in the heretic movements (e.g. Anabaptists, Ranters and Diggers) that articulated combined critiques of Church authorities, the enclosures of private property and forced labour during the feudal period and early capitalist order.[5] These movements often called for communal ownership in Christian idiom, e.g. by elevating “grace” over “works”, yet the form and content of these heretical social movements was different than the Christian millenarian movements that preceded them.[6] Millenarian movements were spurred on by a charismatic individual or momentous event, whereas the heretical movements had defined organizational structures and programmes for change, leading at least one historian to call them the “first proletarian international”.[7] What happened to effect the shift? And what does it mean that anarchist historians easily recognize such movements as “anarchist” when they are located safely in the past – as “precursors” – yet as soon as modern anarchism proper is articulated, religious levelling movements are seen as backward, if not heretical to anarchism itself?

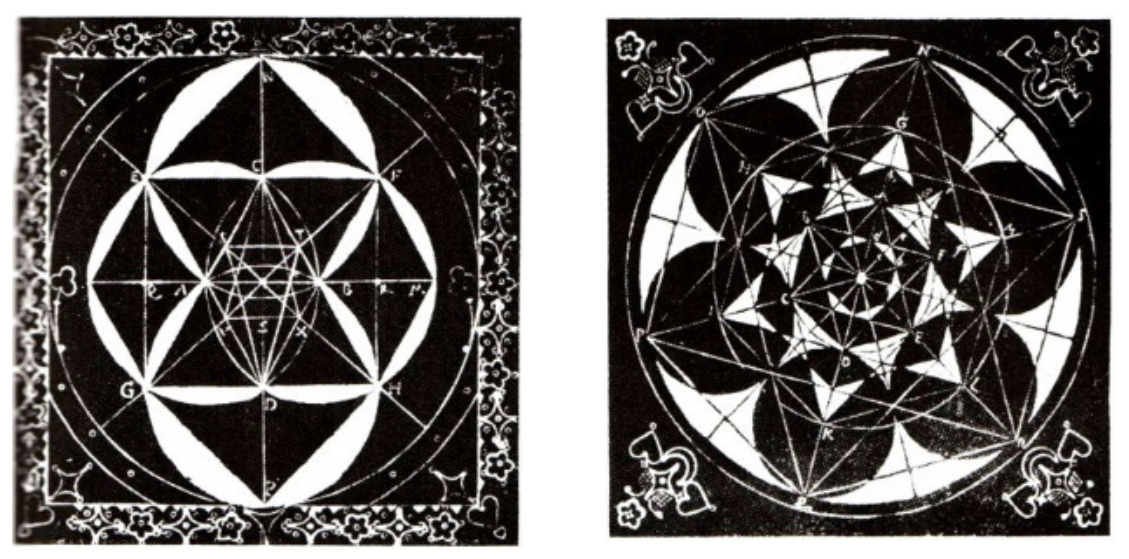

The shift from the spontaneous millenarian movement to the organized heretic one had much to do with their incorporation of non-Christian ideas and mystical doctrines that began circulating in Europe during the Crusades. Platonic philosophy, Pythagorean geometry, Islamic mathematics such as Algebra, Jewish mystical texts and Hermetic treatises were all “rediscovered” via Muslim Spain and translated into Latin during this time. It is well known that the creative recomposition of this ensemble inaugurated the Renaissance and later the “Enlightenment” on the level of high culture, but how the composite led to new levelling projects from below has received less attention. The Hermetica in particular is probably the least recognized fount of the modern Left, and yet an important thread running through it.[8] The Hermetic tradition beholds a unified universe of which man is a microcosm (“As above, so below”), and wherein cosmic time beholds a pulsation of emanation and return. The Hermetic cosmos is hierarchically arranged in symmetrical diachronic and synchronic bifurcations (dyads) and trifurcations (triads), but a web of hidden “correspondences” and forces – alternately “energy” or “light” – cut across and unify all levels; in duration everything remains internally related – “All is One!” Significantly, humanity participates in the regeneration of cosmic unity – our coming to consciousness of this divine role is a crucial step therein. God and creation thus become one and the same, with the inevitable slip that our creative power – including intellectual power – is divine. The initiate must first purge himself of false knowledge in order to be able to receive the true doctrine; at any given moment only some are ready. Hermes himself explains that he “keeps the meaning of his words concealed” from those who are not.[9]

The Hermetica has proved adaptable to a variety of projects. Its neat metaphysical geometry, which arrived alongside algebra and the Pythagorean theorem, helped form a composite that lent itself to a massive investment in mathematical forms and understanding. Mathematics became the hidden architecture of the cosmos, the most permanent and basic truth, and revelation of these secrets certainly did permit an ability to build and create in ways never before imagined — providing both cathedrals and calculus, for example. A variety of mystical doctrines proliferated from the interaction of this composite with pre-existing natural philosophy, alchemy being only the most famous. Hermetic logic can also be discerned in a variety of other eclectic doctrines that developed throughout this period, such as Joachimism, Eckhartean mysticism, Paracelcism, the mathematics of John Dee, the arts of Ramon Lull, Rosicrucianism, vitalism (followed by spiritualism, mesmerism and more) all of which behold secret cosmic “correspondences” and sacred geometry, and in turn inspired the “scientific revolution” of the Enlightenment.[10] To offer just one example, calculus was but the caput mortuum of Newton’s search for the Philosopher’s Stone (if not the Stone itself), his theory of aether “hermetic cosmogony in the language of science”.[11] The conceptual vocabulary of his physics (e.g. “attraction”, “repulsion”) was adopted from the Hermeticist Böhme via famous alchemist Henry More.[12] The “disenchantment tale” of the Enlightenment is just that – a tale. The persecution of “magic” and “witches” among the poor during this period is rather best understood as a disciplinary measure directed specifically at the peasantry – and at women especially – insomuch as it served to enforce the logic of private property, wage work, and the transformation of women into producers of labour. As Sylvia Federici explains, fears around a declining population (work force) and the reproductive autonomy of lower-class women (practicing birth control) was what distinguished the witch from the Renaissance magician, who demonologists consistently passed over.[13] Indeed the alleged devilish activities of the “baby-killing” witch were often plagiarized from the High Magical repertoire.

The Hermetica was also fundamental to the emergence of new social movements against systemic power, specifically Freemasonry and the revolutionary brotherhoods that proliferated during the 18th and 19th centuries. Unlike the millenarian and heretic movements before them, these social movements consisted of literate radicals more so than peasants, and were decisively masculine public spheres. Women’s power within the peasant and heretic movements was ambiguous and never unchallenged, but women were actively involved, partially because renovated and syncretic Christian cosmologies granted them new footholds, and partially because women had the most to lose in the privatization of the commons.[14] Freemasonry, on the other hand, is what social movements look like after the witch hunts: Just as Alchemists played at the creation of life while arresting feminine control over biological creation, speculative Masonry emerges in which elite males worship the “Grand Architect” upon the ashes of artisans’ guilds while real builders were starving. By the establishment of the Grand Lodge in London in 1717, the trade secrets of operative masons had become the spiritual secrets of speculative ones, lodge membership now thoroughly replaced by literate men lured by the ceremony, ritual, and a secret magical history supposedly dating back to the time of King Solomon and the Grand Architect of his temple, Hiram Abiff – Freemasonry itself has always involved a fantastic pastiche of Hermetic and Kabbalistic lore.[15]

One Hermetic aspect of the Masonic cosmology that is key for our discussion, and discussed further below, is the notion that man and society tend toward perfection. The work of Spinoza (1632–77) was also, together and separately, an inspiration in this regard. In his ‘Theological Political Treatise’ (1670), Spinoza arguably provides the founding text of modern liberalism by effectively conflating the ‘chosen people’ and the chosen ‘state’ or ‘society’, and by relativizing the gift of prophecy as an imaginative (vs rational) capacity of men and women of all traditions (‘gentiles’).[16] The imports of Spinoza’s complete oeuvre, across time and audience, are of course diverse (and contested), yet it is clear that with the Treatise he equipped contemporary European radicals with a dynamic philosophy that unified, divinised and animated the universe as well as honoured a deterministic vision of man and nature, thus providing a new religious vision and a renovated foundation for social resistance at once, which contemporaries named “pantheism”.[17] This word, apparently first used by John Toland (1670–1722), was taken up during the period in question to refer to a metaphysics that reemphasized the vitalistic, spirit-in-matter qualities of nature, and tended to deify the material order in the process.[18] This new faith in scientific progress encouraged the conception of temporal institutions both as permanent, and as vehicles for enacting fantasies of progress: A new heaven on earth would be manifest through the works of men themselves.

The Traité des Trois Imposteurs that Masons circulated clandestinely during the 18th century refers to Moses, Jesus and Mohammed as the three “Imposters” in question, yet the coterie who printed it included Toland, who in his Pantheisticon (1720) elaborated a new ritual that claimed to combine the traditions of Druids and ancient Egyptians and included the following call-and-response: “Keep off the prophane People/ The Coast is clear, the Doors are shut, all’s safe/ All things in the world are one, And one in All in all things/ What’s all in All Things is God, Eternal and Immense/ Let us sing a Hymn Upon the Nature of the Universe.” Masons imagined themselves simultaneously the creators of a new egalitarian social order and protagonists of cosmic regeneration, all articulated in the language of sacred architecture. Their society was anti-clerical, yet espoused a pantheism that infused their social levelling project with sacred purpose. Theirs was a pyramidal initiatic society of rising degrees and reserved secrets, but one in which all men met “upon the level”.[19]

The Masonic levelling project was not altogether radical. It is true that Masonic lodges were frequented by elite men who instrumentalised them to further consolidate their power, and that the Masonic project was one of limited reforms, one to which Jews, women, servants and manual labourers were denied entry.[20] It is also true that the Masonic ideal of merit as the only fair distinction allowed room to critique the tension between formal ideals and actual practice, and that Masonic lodges were the first formal public association in 18th century Britain to take up the cause of the “workers’ question” – albeit on a purely philanthropic level – by founding hospices, schools and assistance centres for proletarian workers.[21] In pre–revolutionary France, lodges first began accepting small artisans then proletarian workers as well, lowering fees and abolishing the literacy requirement for entrance to this end. By 1789 there were between 20,000 and 50,000 members in over 600 lodges, and it was no longer possible for participants to reasonably claim they were manifesting an egalitarian social order by merely gathering to discuss literature, science, and the cultivation of Masonic wisdom.[22]

The Revolutionary Brotherhoods

Here we arrive at the question of “conspiratorial” revolutionary brotherhoods that has been exploited in paranoid intrigue.[23] On one hand, due to the utopian rhetoric developed in the Masonic “public” sphere, some members became directly involved in revolutionary activities, both in France before the Revolution, as well as throughout Europe in the years immediately following. On the other hand, it is true that many revolutionaries who were not necessarily Masons made use of the lodges’ existing infrastructure and social networks to further their cause. Yet others simply adopted Masonic iconography and organizational style, which had accrued a measure of symbolic power and legitimacy, in developing their own revolutionary associations. It is not possible in retrospect to distinguish entirely between these phenomena, the salient point being that the revolutionary brotherhoods that proliferated at the turn of the 19th century derived much of their power from their association with perennial secrets and magical power, and that this imaginary and their related style of social organization were fundamental to the development of what we come to recognize as modern revolutionism.[24]

Adam Weishaupt (1748–1830), a young Bavarian professor who founded the Illuminati in 1776, was one of few convinced egalitarians of his day. His revolutionary agenda involved the complete dismantling of the State, Church and institution of private property, all justified by a revamped Christian millenarianism affected by readings of J. J. Rousseau and the Eleusinian mysteries, and organizationally inspired by the secret association of the Pythagoreans.[25] According to Weishaupt, our true “fall from grace” was our submission to the rule of government:

“Let us take Liberty and Equality as the great aim of [Christ’s] doctrines and Morality as the way to attain it, and everything in the New Testament will be comprehensible... Man is fallen from the condition of Liberty and Equality, the STATE OF PRE NATURE. He is under subordination and civil bondage, arising from the vices of man. This is the FALL, and ORIGINAL SIN. The KINGDOM OF GRACE is that restoration which may be brought about by Illumination.”[26]

Yet “Do you really believe it would be useful”, he asked, “as long as countless barriers still remain, to preach to men a purified religion, a superior philosophy, and the art of self-government?”, “[s]hould not all these organizational vices and social ills be corrected gradually and quietly before we may hope to bring about this golden age, and wouldn’t it be better, in the meanwhile, to propagate the truth by way of secret societies? Do we not find traces of the same secret doctrine in the most ancient schools of wisdom?”[27] For Weishaupt, only the “immanent revolution of the human spirit” (die bevorstehende Revolution des menschlichen Geistes), driven by a “widely propagated universal Enlightenment” (verbreitete allgemeine Aufklärung) will break the chains of tyranny, yet repressive political conditions required a discreet Enlightened revolutionary elite in the meantime.[28]

Weishaupt had joined a Masonic lodge in 1774 but had left shortly after, not satisfied with the level of critique he found therein. A year after founding his more radical group however, the members together decided in 1777 to join lodges once more in order to find new recruits, and the strategy worked. The Illuminati grew from Weishaupt and five students in 1776 to fifty-four members in five Bavarian cities by 1779, and eventually extended to Italy, Lyon and Strasbourg to include figures such as Goethe, Schiller, Mozart and Herder. The pyramid structure of the network, modelled on Masonic form, was organized into three grades (the Minervale, Minervale Illuminato, and inner circle of Areopagites) and became both an agency for the transmission of commonplace Enlightenment ideas and attitudes and a “quasi-religious sect” at once, in which men met to contemplate the utopian regeneration of society.[29] Its growth was short-lived however. In 1783, a Minervale Illuminato left the order discontented and shared its radical ideas with his employer, a duchess of the Bavarian royal family. Ensuing suspicions that the Illuminati were connected with an Austrian plot to annex the Electorate (and perhaps worse) alarmed the government, and a repressive campaign began. By the end of the 18th century, stories vilifying the Illuminati and the Freemasons – who were all “under its control” – were in full force. Fearing the death penalty, members went into hiding or exile.[30]

The turn of the century saw a proliferation of other revolutionary societies across Europe that mimicked the forms of Freemasonry and the Illuminati, including the Charbonnerie and Carbonari, the Mazzinians and le Monde, all constituting an international network of revolutionary movements that had certain ideological, if not organizational, solidity. The politics of Babeuf (1760–1797), who was imprisoned in the aftermath of the French Revolution as the prime agent of the “The Conspiracy of Equals” (and anticipated Proudhon’s argument that “Property is Theft” by forty-three years) as well as the politics of Phillipe Buonarotti (1761–1837), who founded the Sublime Perfect Masters in 1809, likewise bear a family resemblance.[31] It did make certain practical sense to organize in a clandestine fashion, as proposed by both Babeuf and Buonarotti (beyond Weishaupt) at the turn of the century, as following the French Revolution the feudal dynasties of Russia, Austria, Prussia, Italy and Spain, with powerful allies in all other European countries and the Catholic church, had formed their own international organization, pledging themselves to forcible action within states in which absolute sovereigns felt threatened by, in the words of Tsar Nicholas, “revolutionary inroads”.[32] These conservative governmental powers formalized themselves as the “Holy Alliance” at the Congress of Vienna in 1814, and proceeded to cooperate in international publication bans, surveillance and repression of militants. This posed serious practical problems. To suggest the prevailing political mood, consider the Fraternal Democrats’ reply to the Brussels Democrats (then led by Karl Marx) in 1846: “[Marx] will tell you with what enthusiasm we welcomed his appearance and the reading of your address... We recommend the formation of a democratic congress of all nations, and we are happy to hear that you have publicly made the same proposal. The conspiracy of kings must be answered with the conspiracy of the peoples...”. [33]

In other words, the pyramidal structure of all the revolutionary organizations, in which each level of the pyramid would know only its immediate superiors, clearly had a practical function insomuch as it protected revolutionaries from repression in this era of increasingly consolidated state power and surveillance. The resemblances were not necessarily due to ex-Illuminati members starting up new groups, but rather partially due to the fearful accounts thereof propagated by governments at the time, which had the ironic effect of inspiring others to try the strategy.[34] The specific organization and ritualization of all this revolutionary activity clearly had other functions as well: the Brotherhoods affirmed and unified the aspirations of illuminated men whose purpose it was to steer mankind toward achieving perfection on (this) earth. Bakunin, 32nd degree Mason himself, appeared to feel the same calling when he founded his own secret “International Brotherhood” in Florence in 1864 that mirrored Weishaupt’s vision almost exactly one hundred years later.[35] The main difference between the two was that Bakunin’s Brotherhood was meant to infiltrate the First International and wrest it from the authoritarian socialists’ control, as opposed to infiltrate Masonic lodges in order to wrest them from Liberals’ control. This is far from the only way in which Masonry and the International Workingman’s Association (IWA) coincide.

Illuminism in the IWA

By the mid-19th century many members of Masonic society had come to feel the proletarian struggle coincided with their greater cause, and the use of Masonic organizations as a cover for revolutionary activity was now a long tradition, as was the tendency to use Masonic rites, customs, and icons to emblematically symbolize the values of equality, solidarity, fraternity, and work.[36] Pierre–Joseph Proudhon, a Mason who lived to see the formation of the IWA, wrote that “The Masonic God is neither Substance, Cause, Soul, Monad, Creator, Father, Logos, Love, Paraclete, Redeemer... God is the personification of universal equilibrium”.[37] In Proudhon’s day, the British lodges were admitting increasing numbers of proletarian members – particularly skilled and literate workers – and had come to support the workers’ struggle to the extent that the first preparatory meeting of the IWA on August 5, 1862, attended by Karl Marx among others, was held in the Free Masons Tavern.[38] Many of those in attendance were “socialist Freemasons”, a phrase applied at the time to the members of the small lodges founded in 1850 and 1858 in London by exiled French republicans, and which involved many members of diverse national backgrounds – the “Memphite” lodges, named after the sacred Egyptian burial ground. The immediate objectives of the Memphite programme were twofold: The struggle against ignorance through education, and helping the proletarians in their struggle for emancipation by way of Proudhonian mutual aid associations. Louis Blanc was among the members of the Memphite lodges (the Loge des Philadelphes in particular) along with at least seven other official founders of the IWA. In Geneva also, the local wing of the IWA was often called the Temple Unique and met in the Masonic lodge of the same name.[39] Many present at the time observed that the incipient IWA’s organizing power was so weak that if it were not for the organizing efforts of socialist Freemasons, the official founding meeting of the IWA on September 28th 1864 would never have come to pass.[40]

Communist and anarchist symbolism, such as the red star and the circle-A, date back to this period and also have Masonic origin. The star, which hosts an endless charge of esoteric meanings in both the Hermetic and Pythagorean traditions, had been adopted in the 18th century (some say 17th) by Freemasons to symbolize the Second Degree of membership in their association – that of Comrade (Compañero and Camarade in my sources). Among socialists, it was first used by members of the Memphite lodges and then the IWA. Regarding the Circle–A, early versions like the 19th century logo of the Spanish locale of the IWA are clearly composed of the compass, level and plumbline of Masonic iconography, the only innovation being that the compass and level are arranged to form the letter A inside of a circle.[41]

Over time these symbols have developed a new complement of meanings – many 21st century anarchists don’t even know that the star used by communists, anarchists and Zapatistas alike is the pagan pentagram, and are not reminded of the mathematical perfection of cosmogony when they behold it, just as they do not necessarily realize there is a genealogical link between the (neo)pagan Mayday celebration and today’s anarchist Mayday marches.[42] In the 19th century, however, these symbolic associations were well known by those involved, and their adoption reflected how much they resonated with mystical and historical weight. Even Bakunin, while he rejected the personal God of his Russian orthodox childhood, put forward a pantheistic revolutionism. In a letter to his sister (1836) he wrote, “Let religion become the basis and reality of your life and your actions, but let it be the pure and single–minded religion of divine reason and divine love... [I]f religion and an inner life appear in us, then we become conscious of our strength, for we feel that God is within us, that same God who creates a new world, a world of absolute freedom and absolute love... that is our aim”.[43]

Throughout the 19th century the only people involved in the revolutionary scene who were consistently annoyed by this sort of mysticism were Marx and Engels. Proudhon’s ramblings about God as Universal Equilibrium were the sort of thing Marx and Engels objected to and contrasted with their own brand of “scientific socialism” – “the French reject philosophy and perpetuate religion by dragging it over with themselves into the projected new state of society”.[44] Bakunin and Marx differed on this point and a number of others, the most famous being the role of the State. Whereas Marx considered a state dictatorship of the proletariat to be a necessary moment in his historical dialectic, Bakunin espoused the notion of a secret revolutionary organization that would “help the people towards self–determination, without the least interference from any sort of domination, even if it be temporary or transitional”.[45] Bakunin also wrote that he saw our “only salvation in a revolutionary anarchy directed by a secret collective force”: “We must direct the people as invisible pilots, not by means of any visible power, but rather through a dictatorship without ostentation, without titles, without official right, which in not having the appearance of power will therefore be more powerful.”[46]

The “dictatorial power” of this secret organization only represents a paradox if we do not recognize the long tradition, and larger cosmology, within which Bakunin is working. Revolution may be “immanent” in the people, but the guidance of illuminated men working in the “occult” was necessary to guide them in the right direction. Members of his International Brotherhood were to act “as lightening rods to electrify them with the current of revolution” precisely to ensure “that this movement and this organization should never be able to constitute any authorities”.[47]

Theosophy, the Dialectic, and Other Esoterica of 19th Century Socialism

Beyond Bakunin himself, Robert Owen (1771–1858), Charles Fourier (1772–1837) and Saint–Simon (1760–1825) are also often cited as forefathers in standard histories of anarchism.[48] The Owenites were distinctly anticlerical, attacking all forms of “religion”, but Owen himself was a spiritualist in admiration of Emmanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772), who taught the arrival of an “internal millennium”. The first Owenite communes in America were based largely on Swedenborg’s teachings.[49] Charles Fourier, for his part, based his political project on what he called the Law of Passional Attraction – a series of correspondences in nature that maintain harmony in the universe and could be applied to human society.[50] Saint-Simonians aimed at reforming existing institutions, but Fourierists and Owenites rejected the existing system altogether. Rather than a mere “changing of the guard”, they advocated the creation of new forms of independent organization within the existing system; hence their “precursor” status to anarchism, perennially defined by the notion of building a new world within the shell of the old, whether via “networks”, communes or syndicates, and primarily defined by its rejection of state power.

Darwin’s treatise on evolution also lent itself to theories of social change that dovetailed with revolutionary thought – a distinction between evolution and revolution in 19th century utopian socialism would be rather forced. The insight that the natural world was characterized by evolving beings blended easily with the concept of cosmic regeneration – adaptive “process” became “progress”, a tendency toward perfection. Indeed many extended the idea from plants and animals to human society, the most famous version of such a move being “Social Darwinism”, traceable to Herbert Spencer who was the actual author of the phrase “survival of the fittest”.[51] Here Darwin is recuperated within the transcendentalist tradition to lend weight to the Hobbesian conception of the state of nature – the “war of each against all” convenient to capitalist ideology. Anarchist natural philosophers of the 19th century read Darwin differently. Piotr Kropotkin posited “Mutual Aid” as a prime “Factor of Evolution” (1914), which we ourselves can manifest as we lead civilization toward egalitarian harmony.[52] It is also worth noting that Kropotkin’s key contribution to anarchist theory was heavily influenced by Mechnikov, who was in turn inspired by a long stint in revolutionary Japan, and who had written of the world being divided into three spheres – inorganic, biological and sociological, each governed by its own set of laws but with enough correspondences between them that human society could be read as a continuously evolving expression of a unified whole.[53]

The theosophy of Helena Pavlova Blavatsky (1831–1891), which intrigued many anarchists, involves a teleology of divine evolution represented by successive “root races” and whose finality was cosmic union.[54] Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910), a Theosophist and anarchist himself, also admired Fedorov (1828–1903) who wrote that the common task of humanity was to use science to resurrect its dead fathers from particles scattered in cosmic dust.[55] Chulkov, Berdyaev and Ivanov, contemporaries of both Fedorov and Tolstoy during the Russian occult revival, all posited a “mystical anarchism” that equated political revolution with realignment in the cosmic sphere.[56] In England, union organizer and early feminist Annie Besant, who organized women match-makers and fought to open the Masonic lodges to women, was convinced she was the reincarnation of Giordano Bruno, and it was Theosophy that inspired her to fight for Home Rule in India, as well as how she met Jawaharlal Nehru, himself a member of the Theosophical Society.[57] Just as socialists were attracted to the occult, spiritualists and mediums of all kinds, who were disproportionately women, were led by their spiritual views to engage the “social question”.[58]

Further examples from the anarchist diaspora include the story of Greek utopian socialist Plotino Rhodakanaty, often credited as being the first European “proselytizer” of anarchism to arrive in Mexico, whose first task upon arrival was to draft pamphlets titled Neopanteísmo (1864) while working with Julio Chávez Lopez to foment uprisings in the Chalco valley, after which he founded the Escuela del Rayo y del Socialismo, (which translates, somewhat ungracefully, as ‘School of Socialism and Lightening’ [and/or] ‘the Ray’ [‘of Light’]).[59] Rhodakanaty later went on to form La Social, a 62-branch network of agitators in contact with the IWA, who formed Falansterios Societarios in indigenous communities.[60] Fifty years later, the politics of Ricardo Flores Magón (1874–1922) were immortalized in his newspaper titled Regeneración, while his comrades called each other “co–religionaries”.[61] Further south, Augusto César Sandino of Nicaragua (who later became the icon of the ‘Sandinista’ revolution in the 1970s and 1980s), was enthralled by the Magnetic-SpiritualSchool, Theosophy, and Zoroastrian, Hindu and Kabbalist lore, fusing all these ideas together with communist ones in such a way that he was refused entry to the Third International as a consequence – they had heard rumours that he flew a seven-striped rainbow flag alongside the red and black.[62] I could go on, but do not have the space to treat so many complex stories of diverse colonial encounters with the attention to specificity they deserve. I merely present these few suggestive examples to remind us that the cross-pollinations of diverse cosmologies underlying modern revolutionism does not necessarily stop, and perhaps find only their latest expression, in present-day anarchists’ selective fascination with indigenous cultures and cosmologies.[63]

Not every anarchist was a theosophist or enamoured with the occult. Emma Goldman, for example, wrote an entirely scathing account of Krishnamurti’s arrival in America as the supposed Theosophical avatar.[64] However, the fact that Goldman’s Mother Earth and a variety of other anarchist periodicals bothered to criticize Theosophy at all should tell us something – nothing is forbidden unless enough people are doing it in the first place. Even the sceptics often grudgingly recognized that they were kindred spirits. As anarchist C. L. James wrote in 1902: “However ill we may think of [Swedenborgian] dogmas, their influence is not to be despised. They have insured, for one thing, a wide diffusion of tendencies ripe for Anarchistic use. Scratch a Spiritualist, and you will find an anarchist.”[65] Indeed it was none other than the president of the American Association of Spiritualists that published the first English translation of The communist Manifesto in 1872.[66]

We can imagine how much this annoyed Marx. But Marx’s anticipation of a Communist millennium after the overthrow of capitalism, brought about by a mixture of willful effort and inbuilt cosmic fate, isn’t actually that different from the idea of the unfolding New Age. The major difference, and the one that prompted Marx and Engels’ to distinguish their utopian vision as “scientific” compared to the others, was their notion of the dialectic, which preserved the form, if not content, of the Hegelian one.[67]

Hegel’s dialectic cast history as a dynamic manifestation of the Idea, the unfolding of consciousness itself, in which everything is but a mode and attribute of a single universal substance.[68] Meanwhile Hegel’s Logic (1812) features an obsession with emanation and return by way of neat geometrical constructions of all kinds, while in his Phenomenology of Spirit (1807), the Idea issues in nature, which issues in Spirit, which returns to Idea in the form of Absolute Spirit.[69] Marx breaks with Hegel in conceiving consciousness as inextricable from material social processes, rather than as a first premise, however the material and the ideal remain indissoluable, his logic is dialectical, and the eschatology of his historical dialectic can be traced back to Joachim de Fiore as much as Hegel’s can. While one of the main defining attributes of anarchism is its anti-Marxism, many Hermetic features of Marxist thought remain preserved (as abstract content) as well as transcended within anarchism’s concrete form.[70]

The fact that Marx builds on Hegel who builds on the Hermetica does not necessarily mean they are wrong; it simply means that a vast amount of “rational” social theory relies on archetypes and geometries of thought stemming from a specific, historically situated cosmology – as does the notion of “rationality” itself.[71]

Socialism and occultism developed in complementary (as well as dialectical) fashion during the 19th century, yet the cosmological grounding of 19th century anarchists’ politics is generally downplayed, or treated as epiphenomenal, in retrospect: Just as Newton’s Alchemy is largely ignored in mainstream histories of the establishment, so Fourier’s Law of Passional Attraction is rewritten in mainstream histories of the Left as a vision of “a harmonious society based on the free play of passions”.[72] It was only when Marxist “scientific socialism” became hegemonic during the 20th century that the theological understandings of modern revolutionism were buried from consciousness among the popular and academic Left.[73] During this past century, whenever occult philosophy has been dealt with in its own right, it has generally been cast as “comforting” in anxiety-provoking periods of social change, or, in certain Marxian style, as a product of capitalist alienation. In Adorno’s Theses against Occultism (in which he makes ample use of Hegel, somewhat ironically), occultism is both a ‘primitive’ holdover and a consequence of ‘commodity fetishism’ at once, in a typical circular (and colonialist) argument that suggests the occult worldview is wrong because it is animistic and vice versa – a “regression to magical thinking”.[74] E. P. Thompson, for his part, characterized the working class as “oscillating” between the “poles” of religious revivalism and radical politics.[75] Over and over, occult philosophy is portrayed as either inducing apathy among the masses or as the territory of elite reactionaries who stir them to hatred, rather than having any connection to socialism, communism, or anarchism. The symbiosis of Blavatsky’s Theosophy with eugenics, and the association of occult narratives and iconography with the rise of fascism, for example, are often pointed out, and of course the connections are there.[76] The ideas offered within occult philosophy do not necessarily lead to revolutionary politics, but they do not necessarily lead away from them either. When regarding the relationship of “magic” to anti-systemic movements, perhaps any deterministic formula is bound to fail. When approached by privileged persons with a lust for power, “magic” can serve to justify and advance elite aspirations. But without the influx of so much material charged as “ancient magical wisdom” that helped triangulate popular religion, modern materialism and social discontent in new ways, we may never have seen the rise of “anarchism” as we know it. Even this quick glance at the history of revolutionism problematizes any simplistic dichotomy of New Age spirituality as reactionary (in both the senses of conservative and right-wing), vs. a materialist worldview as progressive (in both senses of forward-looking and leftist). Rather, secularized and “scientized” religion appears inherent to modern anti-systemic critique and collective action – the West’s attempt to save itself from its impoverished materialism through an enchantment “newly reconfigured”.[77] The world did not have to be “disenchanted” before modern anti-authoritarianism could occur, it had to be re-enchanted: A rejection of material exploitation, “materialist values” and materialist philosophy appear as three sides of the same coin.

To Conclude (and to Begin Anew...)

As I explained at the outset, I began this project partly in order to clarify how the “atheism” professed by those working in the Western anarchist tradition intersects with colonialism, as well as embodies a serious misunderstanding of the history of anarchism itself. In my previous ethnographic work, I had argued that maintaining a neat dichotomy between “spirituality” and “radical politics” only makes sense within a colonialist rubric wherein the religious Other becomes the constitutive limit of the “rational West”. The subsequent reception of my work by both academics and anarchists has beheld a certain pattern: Many anarchist activists and scholars agree that we should indeed be more “respectful” of “indigenous identity”. This, even though I had taken care to emphasize that the operative problem goes beyond a failure to be sufficiently polite in the presence of difference. Beyond being “disrespectful”, insisting on a disenchanted universe delimits the radical imaginary in general. To refrain from telling the non-atheist activist they are wrong (while continuing to think they are), simply because he or she is a person of colour, is really very different than self-critically deconstructing one’s colonial mentality that treats the religious as Other in the first place.[78]

Keeping this question in mind, I wonder what the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in Europe would have looked like if militants regarded culture as property the way many anarchists and indigenous people do today. Certainly the “occult” history of anarchism that I present above could be analysed in terms of Orientalism, and of course the cross-cultural dialogues among heretics during the Crusades happened in the context of complex power relations.[79] At this time, however, it was not yet clear who would emerge as the dominant party. Is Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid “culturally appropriated” because he was inspired by Japanese revolutionaries? Perhaps insofar as we don’t know about it, in combination with the fact that there is now money to be made off Kropotkin-related-commodities. However, reading a concept like “cultural appropriation” on to the past would falsely assume that the fields of meaning and value at the time can be equated to those inflecting today’s self-making projects: During the Renaissance “difference” did not have the same currency, and people were not ascribed the same identities nor “self-identified” according to the categories in play now. It makes sense that a critique of cultural appropriation emerges in the present-day context, wherein cultural difference is fetishized and certain people may valorise themselves by accessorizing commodified attributes of those they structurally oppress, but we may also lose something in the process of applying the logic of property to culture, and to spirituality in particular.[80] When entire cosmologies are reified as “proper” only to specific preordained identities, we are effectively saying they are false to the extent that they do not apply across the cosmos whatsoever. The sacred is thus rendered as alterity, nothing more than a cultural accoutrement in a marketplace as big as the universe. Appropriating indigenous spiritual forms without the intended content is entirely in line with the logic of capitalist colonialism, but so is marking off and containing everything considered sacred as property (and thus nothing more).[81]

In other words, the fact that anarchists are often unable to recognize the subversive potential of religious sensibilities – whether those of indigenous women or Bakunin himself – is disturbing beyond anarchists’ failure to respect the “difference” or the “identity” of others, and to recuperate such a debate within the parameters of “identity” and attendant proprieties is arguably racist in and of itself. Rather, we must actually consider the synergistic relationship between spirituality, faith and radical political movements, whether in present-day Latin America or 19th century Europe, up to and including the original “New Age movement” itself from whence modern anarchism came.

In so doing, we also appeal to anarchists who do not take a hard atheist stance, yet who feel the need to hide their various spiritual inclinations in officially Left-wing spaces: whereas at the turn of the 20th century it was possible to say “Scratch a Spiritualist, and you will find an Anarchist”, a hundred years later the tables have been turned. Other things haven’t changed that much – a zine an activist acquaintance of mine published in 2013 is titled “Anarchism and Hope” wherein he advises: “Fuck waiting on on someone else or some divine force to change shit. Hope means we can see how to do it ourselves.”[82]

I also suggested in my introduction that the story told here is important to reflect on because while the patriarchal bias of classical anarchist theory and practice is often noted in reference to its genesis in male proletarian workers’ movements, the gendered quality of “anarchism” is arguably more fundamental than that. The masculine public sphere of anarchism reaches back even further, and articulates with an occult cosmology that is older still. As anti-systemic resistance in Europe shifted from the millenarian mode to modern socialism, the biggest difference was not, in fact, that the former was “religious” and the latter wasn’t, but rather that in the latter the paradise of heaven would be manifest on the earth, and through the works of men not God – or indeed, men as God – and that it was the job of a chosen few who had access to “ancient spiritual wisdom” circulating in new secret male orders to inspire them to action. To simply argue now that “real” anarchism is by definition feminist as well insomuch as anarchism is “against all forms of domination” does not engage the ways in which the anarchist revolutionary person was constructed vis-à-vis a variety of exclusions from the outset, especially insomuch as these continue unmediated by a certain unacknowledged “vanguardism”: Revolution may be immanent in the people, but as any 21st century anarchist around can see, fluency in a particular vocabulary, knowing the names of certain historical figures, and being vouched for by someone in the know is all requirement for entry into the anarchist club, as is a commitment to a specific ideological constellation informed by the history of its practice, wherein men’s oppression by the state becomes the prototype for power in general.

I may be forcing an analogy by saying that all of this social and subcultural capital resembles the “opaque system of signs” of 19th century initiatic societies, but the (hidden) correspondence is worth reflecting on.[83] Similarly, unless we narrowly define “vanguard” to mean “political party” per se, the common notion among present-day anarchist activists that Marxists are “vanguardist”, whereas anarchists are not, does not bear scrutiny. Anarchists have always considered themselves purveyors of particular insight, and continue to join social movements and the general fray to steer it all in a more revolutionary direction.[84] My point is not to criticize such a practice, but to suggest that its disavowal and dissimulation within discourses of “solidarity” may be disingenuous.[85] While anarchists today carefully skirt the phrase “consciousness raising” (it sounds too Marxist), their various workshops on “anti-oppression” appear to have precisely such a purpose: Why so much self-deception?[86]

Similarly, it should also be significant that today’s anarchist intellectuals generally do not cite indigenous women scholars such as Audra Simpson when they are mounting their compelling arguments against the State: Theirs are not the code words for belonging.[87] Rather, anarchist activists and scholars who are interested in questions of “sovereignty” often prefer to peruse the work of Giorgio Agamben who, much like Carl Schmitt, brackets gender and race by proceeding as if one can equate “human being” and “male citizen of Rome or France”.[88]

It is not simply sexist reading habits that marginalize indigenous women scholars’ work, but also the fact that their words are less easily recuperated within the European anarchist tradition, which has already decided that religion is bad and whose model of oppressive power is the state. For the indigenous women in Andrea Smith’s ethnography, “sovereignty” is “an active, living process within this knot of human, material, and spiritual relationships bound together by mutual responsibilities and obligations”; Audra Simpson, for her part, points out the “critical language game” involved here: indigenous mobilizations of “sovereignty” are useful to signal “processes and intents to others in ways that are understandable”.[89] These remarks certainly sound different than the definitions of “sovereignty” advanced by Schmitt, described by Agamben, and critiqued by many anarchists, wherein sovereignty is always an (unmarked yet male) fantasy of absolute power via the state apparatus (and the practical project of consolidating this power as much as possible). But then again, why should Agamben or Schmitt be granted sovereign jurisdiction over the (power of) the Word? Indigenous women’s mobilizations of “sovereignty” are not necessarily rhetorical, but even when they are, this where the (performative) magic happens. Following their lead could teach us all something about “sovereignty” that Schmitt, Agamben, and their anarchist readers fail to notice: European “sovereignty” has always involved subsuming women and children as property of male citizens whereas it is male citizens that are subsumed by the sovereign.[90] And furthermore, the male-philosophy slip between (legal) person and human being is also preserved in the anarchist response – “autonomy”.[91] It is surely significant that the anarchist person is imagined as an independent, autonomous, and transcendent (sovereign) being that enters into “mutual aid” with others of its kind, much like the modern person writ large – the state. And that just as the state characterizes itself as benevolent to its citizens, the anarchist considers himself benevolent to the people (women) similarly subsumed in his “autonomy” and without whom he could not survive.

It should not be a surprise that anarchist academics ask me to authorize my texts by citing Carl Schmitt — they do want me to be accepted into the club, and kindly offer me the password. Neither should it be a surprise that reviewers suggest consecrating my work with the latest exegetical ruminations on St. Paul by Simon Critchley, whereas it is possible to get through ten years of doctoral studies regarding “anarchism” and only find out about Rosa Luxemburg afterwards, because of a book that happens to be laying on Barbara Ehrenreich’s kitchen table: Anarchism has always been a gendered and racialized domain authorized by speculative elites as much as real builders.[92] In my view, when it comes to approaching things like “liberty” or “equality”, the work of historian Jonathan Israel is more compelling than that of philosophers such as Agamben or Critchley, in my view, as Israel sets aside abstract propositions and instead works hard to “describe in the contexts of history and culture the actual emergence of these ideas”.[93] Perhaps the anthropologist is bound to favour historians such as Israel, yet by the same token is left wanting if contextual analysis does not comprehend the interesting (and productive) contradiction of ideas like “equality, democracy and individual liberty” actually emerging within new, secretive, status-restrictive, male-only clubs that are often referred to, rather curiously, as the modern “public sphere”. How can so many of us pass over the (synchronic) gendered pairing of the Enlightenment Salon and Freemasonic Temple, or the (diachronic) gendered series of (“magical”) witches and (“rational”) brotherhood ceremonies, and yet claim to properly understand the form or content of the ideas of either? Not with recourse to the logic of ‘history’, whether that of Foucault or Hegel (or the Hermetica itself). It seems all ‘earthly perspectives’ are bound to be incomplete after all — including my own.

Let us now move to briefly discuss the “secret society”. While I originally turned my scholarly attention to the cosmology of anarchism on account of my ethnographic research within anarchist and indigenous social movement collaborations, at a certain point during my research for this project I did consider it my specific responsibility to acquaint myself with the great flourishing of creative works concerning “secret societies” and “the Illuminati” to be found on YouTube throughout the past decade. It is clear that in the political and historical imagination corresponding to the majority of these works — popularly referred to as “conspiracy theories” — the ‘Secret Order of the Illuminati’ is understood to be a truly extraordinary organization that has, among other things, achieved the ends of its historical enemy, the Holy Alliance, or the “conspiracy of kings”.

It has also become clear during the same time period that most self-identified anarchist activists in North America dismiss the unsatisfying teleologies of such “conspiracy theories”, especially those rife with anti-Semitic or otherwise racist narratives.[94] Yet such narratives, increasingly prevalent, are arguably the very reason persons concerned with social justice should be paying attention. Respectable researchers may insist that diverse popular ‘conspiracy theories’ of power are laughably false, yet they apparently contribute to real political effects, such as the growing neo-fascist movements in North America, which are not laughable at all. Indeed given the evident charge and influence of the “conspiracy theory” in North America today — its forms and contents, as well as the powerful rhetorical functions of the (derogatory) discursive category itself, I suggest that anarchists consider engaging, mobilizing and qualifying the popular discontent evident in so-called “conspiracy theory”.[95] Anti-capitalists of all stripes would surely do well to tackle so much curious confusion regarding the Left and the Conspiracy of Kings, so many disturbing racialized political imaginaries, and so many ‘bizarre’ origin stories of capitalism often found within the works marked “conspiracy theory”. We might critically analyse the genre in terms of allegory and archetype, narrative and imagery, voice and public, authorship and audience, for the express purpose of practical intervention. We might even explore, in the process, how both dominant powers and their “conspiracy theorist” critics make use of occult ‘arts of memory’ to compel their publics, and thus how the Hermetic tradition continues to inform both Right and Left in the 21st century, albeit not in the way some “conspiracy theorists” may suspect. The pantheism I have discussed in these pages may indeed equally inspire the fantasies of fascism, the apocalypse of the dialectic, and the anarchist faith in an egalitarian social order. We would be wise to not ignore it, because now, as during the 19th century, as during the Renaissance period with which this essay began, the Hermetica proves ‘adaptable to a variety of projects’, including both pyramid and levelling schemes, as well as pyramid schemes for levelling — As Above, So Below.

References

Adorno, Theodor. 1974. ‘Theses Against Occultism’, TELOS, 19.

Agamben, Giorgio. 1993. The Coming Community (University of Minnesota Press: MN).

———. 1998. Homo Sacer – Sovereign Power and Bare Life (Stanford University Press: Stanford).

Alexander, M. Jacqui. 2005. Pedagogies of Crossing: Meditations on Feminism, Sexual Politics, Memory, and the Sacred (Duke University Press: Durham).

Alfred, Taiaiake. 2005. Wawáse – Indigenous Pathways of Action and Freedom (Broadview Press: Toronto).

Anidjar, Gil 2006. ‘Secularism’, Critical Inquiry, 33: 52–76.

Anzaldúa, Gloria. 1987. Borderlands – La Frontera (Aunt Lute: San Francisco).

Asad, Talal 2003. Formations of the Secular – Christianity, Islam, Modernity (Stanford University Press: California).

Bakunin, Mikhail 1970. ‘God and the State.’ in Paul Avrich (ed.), God and the State – With a New Introduction and Index of Persons (Dover Publications Inc.: NY).

Barclay, Harold. 2010. ‘Anarchist Confrontations with Religion.’ in Nathan Jun and Shane Wahl (ed.), New Perspectives on Anarchism (Lexington: Lanham).

Beiser, Frederick. 2005. Hegel (Routledge: London).

Benz, Ernst. 1989. The Theology of Electricity (Pickwick Publications: Allison Park).

Beringer, Yasha 2013. 200 Years of Royal Arch Freemasonry in England, 1813–2013 (Lewis Masonic: London).

Blanquel, Eduardo. 1964. ‘El anarco-magonismo’, Historia Mexicana, 13: 394–427.

Blavatsky, H. P.. 1966. ‘An Abridgement of the Secret Doctrine.’ in Elizabeth Preston and Christmas Humphreys (ed.) (The Theosophical Publishing House: Illinois).

Bose, Atindranath. 1967. A History of Anarchism (World Press: Calcutta).

Braunthal, Julius. 1967. History of the International, Vol. 1 – 1864–1914 (Frederick A. Praeger: NY ).

Buck-Morss, Susan. 2000. ‘Hegel and Haiti’, Critical Inquiry, Vol 26: pp. 821–65.

Buisine, Andrée. 1995. ‘Annie Besant, socialiste et mystique’, Politica Hermetica, 9.

Burke, Peter. 1978. Popular Culture in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge).

Cappelletti, Angel. 1990. ‘Prólogo y cronologia – Anarquismo Latinoamericano.’ in Carlos and Angel Cappelletti Rama (ed.), El Anarquismo en America Latina (Biblioteca Ayacucho: Caracas).

Cesaire, Aimé 2000 [1955]. Discourse on Colonialism (Monthly Review Press: NY).

Chadwick, Owen. 1975. The Secularization of the European Mind in the Nineteenth Century (the Gifford lectures in the University of Edinburgh for 1973–4) (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge).

Christoyannopoulos, Alexandre and Lara Apps. 2019. ‘Anarchism and Religion.’ in Carl Levy and Matthew Adams (ed.), The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism (Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke).

Cohn, Norman. 1970. The Pursuit of the Millennium: Revolutionary Millenarians and Mystical Anarchists of the Middle Ages (Oxford University Press: Oxford).

———. 1966. Warrant for Genocide: The Myth of the Jewish World-Conspiracy and the Protocols of the Elders of Zion (New York: Harper & Row)

Copenhaver, Brian. 1992. Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation with Notes and Introduction (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge).

———. 2015. The Book of Magic – From Antiquity to Enlightenment (Penguin: NY).

Critchley, Simon 2012. The Faith of the Faithless (Verso: NY).

Cutler, Robert M. 1985. Mikhail Bakunin – From out of the Dustbin – Bakunin’s Basic Writings, 1869–71 (Ardis: Michigan).

Darwin, Charles. 1964 (1859). On the Origin of Species (A Facsimile of the First Edition) (Harvard University Press: Cambridge).

Doyle, W. 1967. The Parlementaires of Bordeaux at the end of the Eighteenth Century 1775–1790 (Oxford D. Phil, thesis: Oxford).

Dubreuil, J. P. 1838. Histoire des Franc-Maçons (H.I.G. François: Bruxelles).

Dufart, P. (libraire) 1812. Histoire de la Fondation du Grand Orient de France. (L’imprimerie de Nouzou, rue de Clery, No. 9: Paris).

Durkheim, Emile. 2008 [1912]. The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (George Allen & Unwin Ltd: London).

Eckhardt, Wolfgang 2016. The First Socialist Schism: Bakunin vs. Marx in the International Working Men’s Association (PM Press CA).

Edelman, Nicole. 1995. ‘Somnabulisme, médiumnité et socialisme’, Politica Hermetica, 9.

Edwards, L.S. and Elizabeth Fraser. 1969. Selected Writings of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (Macmillan and Co. Ltd.: London).

Eisenstein, Elizabeth L. 1959. The First Professional Revolutionist: Filippo Michele Buonarroti (1761–1837) (Harvard University Press: Cambridge).

Eliade, Mircea. 1974 [1949]. The Myth of the Eternal Return – or, Cosmos and History (Princeton University Press: Princeton).

Engels, Friedrich. 1975. ‘Progress of Social Reform on the Continent.’ in Robert Tucker (ed.), Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels – Collected Works, vol. 3 (International Publishers: NY).

Evans, Kate. 2015. Red Rosa – A Graphic Biography of Rosa Luxemburg (Verso: NY).

Federici, Sylvia 2004. Caliban and the Witch – Women, The Body and Primitive Accumulation (Autonomedia: NY).

Fried, Albert and Ronald Sanders. 1964. Socialist Thought – A Documentary History (Anchor Books: NY).

Gabay, Alfred J. 2005. The Covert Enlightenment – Eighteenth Century Counterculture and its Aftermath (Swedenborg Foundation Publishers: West Chester).

Gay, Peter 1966. The Enlightenment: An Interpretation (Knopf: New York).

Goodrick-Clarke, Nicolas. 1992. The Occult Roots of Nazism: Secret Aryan Cults and Their Influence on Nazi Ideology: The Ariosophists of Austria and Germany, 1890–1935 (New York University Press: NY).

Graeber, David. 2002. ‘The New Anarchists’, New Left Review, 13, January/February: 61–74.

———. 2015. ‘Radical alterity is just another way of saying ‘reality’: A reply to Eduardo Viveiros de Castro’, Hau – Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 5.

Hart, John. 1978. Anarchism and the Mexican Working Class, 1860–1931 (UT Press: Austin).

Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich. 1977 (1807). Phenomenology of Spirit (Clarendon Press: Oxford).

———. 2010 (1812). The Science of Logic (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge).

Hill, Christopher. 1975. The World Turned Upside Down – Radical Ideas During the English Revolution (Penguin: Harmondsworth).

Hobsbawm, E. J. 1959. Primitive Rebels – Studies in Archaic Forms of Social Movement in the 19th and 20th Centuries (Norton: NY).

Hodges, Donald. 1992. Sandino’s Communism – Spiritual Politics for the Twenty-First Century (UT Press: Austin).

Illades, Carlos. 2002. Rhodakanaty y la formación del pensamiento socialista en México (Rubi: Anthropos).

Israel, Jonathan. 2001. Radical Enlightenment (Oxford University Press: Oxford).

———. 2010. A Revolution of Mind – Radical Enlightenment and the Intellectual Origins of Modern Democracy (Princeton University Press: Princeton).

Jacob, Margaret. 1981. The Radical Enlightenment – Pantheists, Freemasons and Republicans (George Allen and Unwin: London).

———. 1988. ‘Freemasonry and the Utopian Impulse.’ in R.H. Popkin (ed.), Millenarianism and Messianism in English Literature and Thought (E.J. Brill: NY).

———. 2006. Strangers Nowhere in the World – The Rise of Cosmopolitanism in Early Modern Europe (University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia).

James, C.L.. 1902. Origin of Anarchism (A. Isaak: Chicago).

Johnson, K. and K. E. Ferguson. 2019. ‘Anarchism and Indigeneity.’ in M. S. Adams C. Levy (ed.), The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism (Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke).

Konishi, Sho. 2013. Anarchist Modernity: Cooperatism and Japanese-Russian Intellectual Relations in Modern Japan (Cambridge: Harvard University Press,).

———. 2007. ‘Reopening the “Opening of Japan”: A Russian-Japanese Revolutionary Encounter and the Vision of Anarchist Progress’, American Historical Review, 112: 101–30.

Kropotkin, Piotr. 1955 [1914]. Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution (Extending Horizons Books: Boston).

Lagalisse, Erica. 2018. Occult Features of Anarchism – With Attention to the Conspiracy of Kings and the Conspiracy of the Peoples (Oakland: PM Press)

———. 2016. “Good Politics”: Property, Intersectionality, and the Making of the Anarchist Self, PhD dissertation, Department of Anthropology, McGill University, Montreal.

———. 2015. “Anarchism and Conspiracy Theories in North America, or: The Conspiracy Theory as Antidote to Foucault” American Anthropological Association (AAA) Annual Meeting. Denver, CO. December.

———. 2011. ‘“Marginalizing Magdalena”: Intersections of Gender and the Secular in Anarchoindigenist Solidarity Activism’, Signs – Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 36.

———. 2011. ‘Participación e influencias anarquistas en el movimiento “Occupy Wall Street” ‘, Periodico del CNT (Confederación Nacional del Trabajo), nº 383, noviembre.

Lakoff, Aaron. 2013. Anarchism and Hope (Howl! arts collective [zine]: Montréal).

Lambert, Malcolm. 1992 (1977). Medieval Heresy (Basil Blackwell: Oxford).

Laqueur, Thomas. 2006. ‘Why the Margins Matter: Occultism and the Making of Modernity’, Modern Intellectual History, 3: 111–35.

Lauzeray, Christian. 1988. L’Égypte ancienne et la Franc-Maçonnerie (Éditeur Guy Trédaniel Paris).

Le Forestier, René. 1974 (1914). Les Illuminés de Bavière et la Franc-Maçonnerie Allemande (Slatkine Megariotis Reprints (Reprint of the 1914 Paris edition): Genève).

Lea, Henry Charles. 1922. A History of the Inquisition of the Middle Ages (Macmillan: London).

Lehning, Arthur. 1970. From Buonarroti to Bakunin – Studies in International Socialism (Brill: Leiden).

———. 1973. Mikhail Bakunin – Selected Writings (University of Michigan Press: Cape).

Levy, Carl. 2011. “Anarchism and cosmopolitanism.” Journal of Political Ideologies 16 (3):265–278.

———. 2010. ‘Social Histories of Anarchism’, Journal for the Study of Radicalism, 4: 1–44.

———. 2004. ‘Anarchism, Internationalism and Nationalism in Europe, 1860–1939’, Australian Journal of Politics and History, 50: 330–42.

Levy, R.S. 1995. A Lie and a Libel: The History of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. (University of Nebraska Press: NB).

Linebaugh, Peter, and Marcus Buford Rediker. 2000. The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic (Beacon Press: Boston).

Lomnitz, Claudio. 2014. The Return of Comrade Ricardo Flores Magón (Zone Books: New York).

Magee, Glenn Alexander. 2001. Hegel and the Hermetic Tradition (Cornell University Press: Ithaca and London).

Manuel, Frank E. and Fritzie P. Manuel. 1979. Utopian Thought in the Western World (Harvard University Press: Cambridge).

Marsden, Victor E. (ed). 2006. The Protocols of the Elders of Zion (Filiquarian Publishing LLC).

Marshall, Peter. 1993. Demanding the Impossible – A History of Anarchism (Fontana Press: London).

Marx, Karl. 1990 [1876]. Capital Vol. 1 (Penguin: London).

———. [1932] 1978. ‘The German Ideology.’ in Robert Tucker (ed.), The Marx-Engels Reader (W. W. Norton & Company: NY).

Mehring, Franz 1936. Karl Marx: The Story of His Life ( Fitzgerald: London).

Mulsow, Martin. 2003. ‘“Adam Weishaupt as Philosoph”.’ in W. Müller-Seidel and W. Reidel (ed.), Die Weimarer Klassik und ihre Geheimbünde (Würzburg).

Moya, José. 2004. “The positive side of stereotypes: Jewish anarchists in early twentieth-century Buenos Aires.” Jewish History 18 (1): pp. 19–48.

Nettlau, Max. 1979 (1929). La anarquía a través de los tiempos (Editorial Antalbe: Barcelona).

Pernicone, Nunzio. 1993. Italian Anarchism, 1864–1892 (Princeton University Press: New Jersey).

Preston, William. 1855. The Universal Masonic Library, Vol. III – Preston’s Illustrations of Masonry (W. Leonard & Co., American Masonic Agency: NY).

Raine, Kathleen. 1970. William Blake (World of Art) (Thames and Hudson: London).

Reidel, W. 2003. ‘Aufklärung und Macht. Schiller, Abel und die Illuminaten.’ in W. Müller-Seidel and W. Reidel (ed.), Die Weimarer Klassik und ihre Geheimbünde (Würzburg).

Roberts, J. M. 1972. The Mythology of the Secret Societies (Secker and Warburg: London).

Robison, John. 1798. Proofs of a conspiracy against all the religions and governments of Europe, carried on in the secret meetings of Freemasons, Illuminati, and reading societies (W. Watson and Son: Dublin).

Rose, R.B. 1978. Gracchus Babeuf – The First Revolutionary Communist (Stanford University Press: Stanford).

Rosenthal, Bernice Glatzer. 1997. ‘Introduction.’ in Bernice Glatzer Rosenthal (ed.), The Occult in Russian and Soviet Culture (Cornell University Press: Ithaca and London).

———. 1997. ‘Political Implications of the Early Twentieth-CenturyOccult Revival.’ in Bernice Glatzer Rosenthal (ed.), The Occult in Russian and Soviet Culture (Cornell University Press: Ithaca and London).

Rublack, Ulinka. 2015. The Astronomer and the Witch – Johan Kepler’s Fight for his Mother (Oxford University Press: Oxford).

Sahlins, Marshall. 1996. ‘The Sadness of Sweetness: The Native Anthropology of Western Cosmology’, Current Anthropology, 37: 395–428.

Said, Edward. 1978. Orientalism (Vintage: NY).

Saña, Heleno. 1970. El anarquismo, de Proudhon a Cohn-Bendit (Indice: [Madrid]).

Schmitt, Carl. 1985 [1922]. Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty (Chicago University Press: Chicago).

Scott, Joan. 2009. “Sexularism.” In RSCAS Distinguished Lectures. Florence, Italy.

Simpson, Audra. 2014. Mohawk Interruptus – Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States (Duke University Press: Durham and London).

Skeggs, Beverley. 2004. Class, Self, Culture (Routledge: London).

Smith, Andrea. 2005. Conquest – Sexual Violence and American Indian Genocide (South End Press: Cambridge).

———. 2008. North Americans and the Christian Right: The Gendered Politics of Unlikely Alliances (Duke University Press: Durham and London).

Spencer, Herbert 1864. Principles of Biology (William and Norgate: London).

Spinoza, Benedictus de. 1963. The Cartesian principles and Thoughts on metaphysics (Bobbs-Merrill: Indianapolis).

———. 2000. Ethics. (Oxford University Press: NY).

———. 2007. Theological-Political Treatise (Cambridge University Press: NY).

Szajkowski, Zosa. 1947. “The Jewish Saint-Simonians and Socialist Antisemites in France.” Jewish Social Studies 9 (1):33–60.

Tambiah, Stanley. 1990. Magic, Science, Religion and the Scope of Rationality (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge).

Thomas, Keith. 1982. Religion and the Decline of Magic: Studies in Popular Beliefs in Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century England (Penguin: New York).

Thompson, E.P. 1963. The Making of the English Working Class (Vintage: NY).

Todd, Zoe. 2016. ‘An Indigenous Feminist’s Take On The Ontological Turn: ‘Ontology’ Is Just Another Word For Colonialism’, Journal of Historical Sociology, 29.

Tolstoy, L. 2001. ‘The Kingdom of God is Within You: Christianity Not as a Mystical Doctrine but as a New Understanding of Life.’ in, The Kingdom of God and Peace Essays (Rupa: New Delhi).

Torres Parés, Javier 1990. La Revolución sin Frontera: el Partido Liberal Mexicano y las relaciones entre el movimiento obrero de México y de los Estados Unidos, 1900–1923 (Ediciones Hispánicas).

Trejo, Ruben. 2005. Magonismo: utopia y revolucion, 1910 – 1913 (Cultura Libre: Mexico, D.F.).

Tsing, Anna 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World – On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton University Press: NJ).

Unknown. 1744. La Franc-Maçonne ou révélation des mystères des franc-maçons (Brussels).

Valín Fernández, Alberto. 2008. Masonería y revolución – Del mito literario a la realidad historica (Santa Cruz de Tenerife: Ediciones Idea).

———. 2005. ‘De masones y revolucionarios: una reflexión en torno e este encuentro’, Anuario Brigantino, 28: 173–98.

van der Veer, Peter. 2001. Imperial Encounters – Religion and Modernity in India and Britain (Princeton University Press: Princeton).

Van Dülman, Richard. 1975. Der Geheimbund der Illuminaten (Stuttgart).

Veysey. 1973. The Communal Experience – Anarchist and Mystical Counter-Cultures in America (Harper and Row: New York and London).

Vondung, Klaus. 1992. ‘Millenarianism, Hermeticism, and the Search for a Universal Science.’ in Stephen McKnight (ed.), Science, Pseudoscience, and Utopianism in Early Modern Thought (University of Missouri Press: Columbia).

Webb, James. 1976. The Occult Establishment (Open Court Publishing Company: Illinois).

Webster, Nesta Helen. 1936. Secret Societies and Subversive Movements (Boswell: London).

Westcott, Dr. William Wynn 1912. A Catalogue Raisonné of works on the Occult Sciences, Vol III – Freemasonry, A Catalogue of Lodge Histories (England), with a Preface (F.L. Gardner: London).

Westfall, Richard S. 1972. ‘Newton and the Hermetic Tradition.’ in Allen G. Debus (ed.), Science, Medicine and Society in the Renaissance (Science History Publications: New York).

Woodcock, George. 1962. Anarchism – A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements (The World Publishing Company: Cleveland).

Yates, Frances. 1964. Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition (University of Chicago Press: Chicago).

———. 1966. The Art of Memory (Routledge: London).

———. 2002 [1972]. The Rosicrucian Enlightenment (Routledge: London).