Morris Brodie

Volunteers for Anarchy

The International Group of the Durruti Column in the Spanish Civil War

Abstract

This article explores the twin phenomena of anti-fascism and transnational war volunteering through a case study of the International Group of the Durruti Column in the Spanish Civil War. This anarchist-led unit comprised approximately 368 volunteers with a variety of political views from at least 25 different countries. The article examines the relationship between these foreign volunteers and their Spanish hosts (both anarchist and non-anarchist), through, firstly, the militarization of the militias in the winter of 1936, and, secondly, the group’s role in the May Days of 1937 and its aftermath. These episodes show the often hostile attitude of Spaniards to foreigners within Spain and challenge the characterization of the conflict as distinctively internationalist. The lives of these volunteers also highlight the continuity of anti-fascism between the interwar and wartime period, with Spain acting as an ‘anti-fascist melting pot’ where volunteers of different backgrounds and political leanings came together in a common cause. This commitment, however, was not unconditional, and was frequently challenged due to circumstances within Spain. Through studying these transnational fighters, we have a more comprehensive understanding of the complex nature of twentieth century anti-fascism.

Volunteers for Anarchy: The International Group of the Durruti Column in the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War is famous partly for those who came to Spain to fight fascism beyond their own countries. Approximately 35,000 volunteers travelled to Spain to defend the Republic from 1936 to 1939, the vast majority of these serving in the International Brigades organized by the Communist International (Comintern). A significant number, however, fought in formations under the control of the Spanish anarchist Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (National Confederation of Labour, CNT) and Federación Anarquista Ibérica (Iberian Anarchist Federation, FAI). Although there were similarities between service in both detachments, there were also important differences, over discipline, militarization, and the wider political focus of the struggle. Contrary to the plethora of studies focusing on the brigadistas, international volunteers in anarchist units have been neglected by historians. Those few that have studied them have tended to take either an individual (focusing on anarchist volunteers more well-known for other endeavours such as Simone Weil or Carl Einstein) or country-specific approach that, whilst valuable, ignores the transnational and internationalist character of these units.[1] Anti-fascism in the 1930s was not only an international, but transnational phenomenon. Emphasizing the role of different national groups within international units risks reinforcing the very national boundaries these volunteers sought to challenge. It also shares parallels with more explicitly nationalist histories of war volunteering.[2]

This article seeks to address this by focusing on one of the most significant foreign anarchist units: the International Group (Grupo Internacional) of the Durruti Column (later the International Company of the Popular Army’s 26th (Durruti) Division).[3] Through a case study of this unit, comprising approximately 368 milicianos (militia members) from at least 25 different countries, it traces the experience of foreign anarchist volunteers in Spain. The International Group was, as one contemporary publication noted, a ‘living International,’ comprising anti-fascists from around the world.[4] Examining its workings highlights the variety of problems facing foreigners in Spain during the civil war and how they sought to overcome them. It helps us to understand the conflicts within the Spanish Republican camp, the complex nature of international anti-fascism during the interwar period and the wider phenomenon of transnational war volunteering more generally.

After an overview of the place of international anarchist volunteers in the wider historiography of the war, I will examine the background of the volunteers, including their nationality, class, gender and political affiliation. The next two sections contribute to the scholarship on foreign war volunteers by investigating the relationship between the International Group and its Spanish hosts, through, firstly, the militarization of the militias in the winter of 1936, and, secondly, the group’s role in the May Days of 1937 and its aftermath. This includes volunteers’ later service in the International Brigades, an important comparison throughout. These episodes show the often hostile attitude of Spaniards to foreigners within Spain and challenge the romantic, almost mythical, picture of foreign service in Spain often presented in both veterans’ and scholars’ accounts.[5] The final section of the article deals with volunteers’ trajectories after defeat, emphasizing the continuity between interwar and wartime anti-fascism, whilst acknowledging that transnational solidarity had its limits.

According to Mae N. Ngai, transnational history ‘follows the movement or reach of people, ideas, and/or things across national (or other defined) borders.’[6] Transnational history is not simply a comparative study spanning two or more countries; it recognizes the interconnections between them, and how these shape developments in all the countries under consideration. There has been a ‘transnational turn’ in both anti-fascist and anarchist studies in recent years, much of which focuses on the 1930s and 1940s. Recent work by Michael Seidman and upcoming projects by Helen Graham and Robert Gildea indicate a new appreciation of the transnational nature of interwar anti-fascism. Indeed, Hugo García maintains that it ‘appears in many respects to be the ideal type of a transnational movement.’[7] The Spanish Civil War in particular lends itself to transnational study, given the international context of the conflict and its reputation as a testing ground for the Second World War. Jorge Marco, for example, has recently examined the effect of transnational soldiers on the military tactics of both the Spanish Republican and Allied armies, and Lisa A. Kirschenbaum has produced a pioneering history of transnational communism during the civil war period through the eyes of the Comintern. There is a need, however, to disentangle the history of anti-fascism from that of the communist movement.[8]

Anarchism, in view of its hostility to established organizations and emphasis on individual freedom, fluidity and personal networks, seems ideally suited to study through a transnational lens. Constance Bantman and Bert Altena even suggest that ‘transnationalism seems to be a natural characteristic of anarchist movements.’[9] It is surprising, then, that there has been comparatively little scholarly work on the transnational nature of anarchism during the Spanish Civil War, with most studies on anarchism during the period focusing on the CNT and FAI.[10] Although Enrico Acciai has examined Italian anti-fascist volunteers in the Ascaso Column during the conflict, international anarchist milicianos more generally have escaped such attention. The recent publication of the memoirs of Antoine Gimenez (pseudonym of Bruno Salvadori, an Italian volunteer who fought with the International Group during the war)—complete with extensive historical notes—is a possible sign that this may be changing.[11]

As I have argued elsewhere, the Spanish Civil War had a profound effect on the international anarchist movement. The apparently spontaneous factory and land collectivisations seen across significant portions of Republican territory, combined with the construction of anti-hierarchical revolutionary militias to combat fascism, inspired comrades across the world and injected life into an otherwise moribund movement. Many international anarchists set up new groups and newspapers in their own countries devoted to raising solidarity for those in Spain. Others made the trip across the Atlantic or over the Pyrenees to work for the CNT-FAI in Barcelona and other cities, document the social revolution that was sweeping through areas of Aragón and Catalonia or to join the militias at the front.[12] Their influence on the CNT-FAI has been emphasized in recent works by James A. Baer and Martha A. Ackelsberg, who examine the flow of both activists and ideas between Spain and Latin America in the period before and during the civil war. Their military contribution is more difficult to assess, however. Unlike the International Brigades, whose introduction during the Battle of Madrid has achieved legendary status and is often credited (rightly or wrongly) with ‘saving’ the capital, international anarchist milicianos do not have a ‘defining battle’ as such, and their service was much more fragmented than that of the brigadistas.[13]

Calculating the number of foreign anarchists who fought in Spain remains challenging. The Comandancia Militar de Milicias (Militia Military Command) did not maintain lists of anarchist militias operating in Aragón and the Levant (the main area of operations), and anarchists were less meticulous in their record-keeping than their communist counterparts. One article appearing in the Italian-American anarchist newspaper Il Martello in February 1938 claimed that 2000 foreign anarchists had served on the Aragón front since the war’s beginning. Historian Dieter Nelles argues that between 1000 and 1500 foreign anarchists came to Catalonia in the first weeks after July 1936, and Augustin Souchy, who worked for the CNT-FAI Foreign Language Division during the conflict, estimates a figure of 3000 in total.[14] Most anarchists who did not join the International Brigades fought in international groups attached to CNT and FAI militias. The CNT, with between 500,000 and a million members in 1936, was the most powerful anarchist organization in the world at the time. The more radical FAI, with a pre-war peak membership of 5500 in 1933, also had a reputation for ideological firmness and militancy. There were international groups in the Ascaso Column, the Ortiz Column, and smaller units like the Batallón de la Muerte (Battalion of Death) and Muerte es Maestro (Death is Master) militia.[15]

Anarchist columns varied in organization, but the primary unit was the agrupación (action group). These were composed of centurias (usually five centurias to an agrupación), themselves containing approximately 100 milicianos, as well as a medical team and a machine gun section. Centurias were split once more into grupos (groups) comprising between 10 and 25 fighters. These grupos elected delegates to the centuria, which in turn sent representatives to the agrupaciones, who then liaised with the column’s war committee. The nomenclature of the anarchist militias reflects the hostility to which anarchists regarded military units historically. This contrasted with units controlled by Marxists, which were largely modelled on the Red Army.[16]

The International Group of the Durruti Column is perhaps the most famous of the foreign anarchist militia units. According to anarchist historian Abel Paz, around 400 fighters served in the group at some point, while David Berry believes that the group reached a maximum of 240 members. My own research has uncovered 368 individuals from 25 countries. I have excluded those internacionales known to have served with the column but not explicitly with the International Group. I have omitted, for example, the Italian-American Carl Marzani, who was a member of the Durruti Column but not the International Group (indeed, he—incorrectly—identifies himself as the ‘only non-Spaniard’ in the column), as well as some militants mentioned by Berry.[17] The main sources for volunteers are the records of the CNT and FAI held at the International Institute of Social History (IISH) in Amsterdam, the records of the Comintern within the Russian State Archive of Social and Political History (RGASPI), as well as newspapers and the memoirs, diaries and letters of participants.[18] Allowing for gaps in record keeping, particularly during the months before the militarization of the anarchist militias in early 1937 (discussed below), Paz’s estimate for numbers seems sensible.

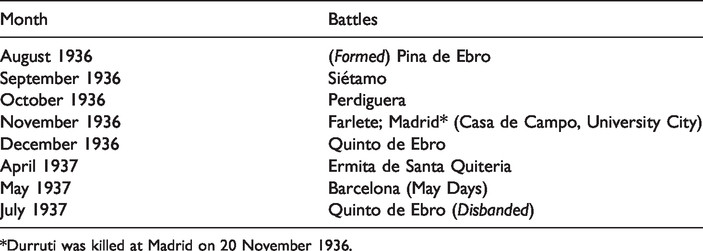

The International Group was initially formed on the Aragón front at the end of July 1936 from an assortment of approximately 30 volunteers. According to Berry, it was the brainchild of French anarchists François Charles Carpentier and Charles Ridel (AKA Louis Mercier Vega). Born in Reims in 1904, Carpentier had been a corporal during the First World War and joined the Saint-Denis group of the Union Anarchiste (Anarchist Union, UA) in 1927. Ridel, in addition to being a UA member, had attended the CNT congress in Zaragoza in May 1936, and as a result knew Buenaventura Durruti (the column’s commander) personally. The pair left Paris in late July bound for Spain, eventually joining up with the column at Fraga in Huesca province. They became the representatives of the International Group, in addition to French anarchist Fernand Fortin, Emile Cottin (the French anarchist famous for the attempted assassination of Georges Clemenceau in 1919) and an unidentified ‘Carles.’ The internationals were known as gorros negros (black bonnets), named after their unofficial uniform of a black beret. This gave greater camouflage for night attacks, in which the International Group often participated (see Table 1).[19]

The first delegate (de facto leader) of the group was the Frenchman Louis Berthomieu, who had been an artillery captain during the First World War. Other volunteers selected for leadership roles leaders in the group also had previous military experience, including the Italian Pietro (Pablo) Vagliasindi, the Germans Christian Lamotte and Carl Einstein and Frenchman Alexis Cardeur. This, coupled with the fact that Berthomieu said he ‘knew nothing’ about political matters, suggests that military experience, rather than ideological consistency, was the overriding factor in electing leaders within the group.[20] This contradicts the assertion of Charles Esdaile that militia leaders ‘owed their position to nothing other than their posts in some party or trade-union hierarchy.’[21]

According to Paz, the International Group was split into five sections, each containing around 50 milicianos. In practice, though, there were two rough groupings: a German-speaking and a French-speaking section. Other nationalities were scattered across the group, with multilingual volunteers acting as translators. French and German were the primary languages used, but, according to the German anarchist exile newspaper Die Soziale Revolution, ‘at least half a dozen different mother tongues were spoken,’ highlighting the improvisational—and transnational—character of the group.[22] Few of the early foreign volunteers spoke Spanish (Berthomieu was an exception—another possible reason for his election to a leadership position). Nevertheless, like in the International Brigades, there were shared Spanish phrases among anarchist volunteers, which they used when travelling through villages: ¡Viva la Confederación! (Long live the Confederation!—the CNT) and ¡Viva la revolución social! (Long live the social revolution!). These explicitly revolutionary slogans, as opposed to the defensive slogan of ¡No pasaran! (They shall not pass!) favoured in the brigades, are a notable sign of the anarchist unit’s commitment to the radical interpretation of the war, the repercussions of which are discussed below.[23]

The French-speaking section, which included Italians and Belgians, was known as the Sebastién Faure centuria, after the French anarchist of the same name. This unit was on occasion seconded to the Ortiz Column, which explains why it is listed distinctly in some of the CNT files. The German-speaking section also contained Swiss and Swedish volunteers. Some accounts assert that this was known as the Erich Mühsam centuria, but I could find no contemporary evidence of this, and it may be being confused with a machine gun section of the same name in the Ascaso Column. The remnants of this group transferred to the Durruti Column in November 1936. Similarly, Kenyon Zimmer has dismissed claims by historians that there was a Sacco and Vanzetti centuria composed of Americans affiliated with the column.[24]

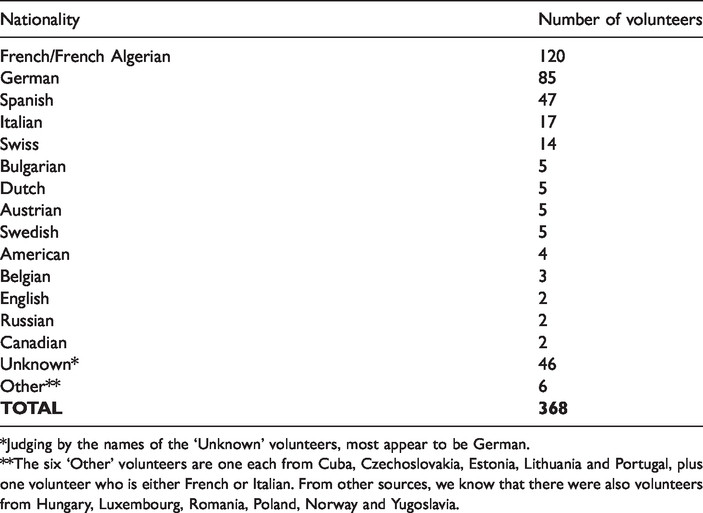

As Table 2 shows, the largest numbers of volunteers came from France and Germany, followed by Spain, Italy and Switzerland. France supplied more volunteers than any other country during the civil war (around 9,000 fought in the International Brigades), so the high number of French anarchists is not surprising, especially considering the proximity of France to Spain and relative strength of the French movement. International volunteers for the militias were often processed by the French anarchist movement, either in Paris or through the Section Française (French Section) located in the border town of Puigcerdà.[25] Germans were over-represented in the International Group in terms of the strength of the German anarchist movement. This was partly because Spain was the primary exile destination for German anarchists, with many settling in Barcelona before 1936 due to the Spanish Republic’s liberal asylum policy and employment laws. These exiles formed the Gruppe Deutsche Anarcho-Syndikalisten im Ausland (Group of German Anarcho-Syndicalists in Exile, DAS) in 1934, which would play an important role in the civil war in Barcelona. In addition, as discussed below, a significant proportion of Germans within the column were members or former members of the Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands (Communist Party of Germany, KPD).[26]

The large number of Spaniards suggests a certain looseness in the definition of the International Group and mirrors the large numbers of native fighters in the International Brigades during the closing stages of the conflict. Details on these volunteers are slight (partly because they are often referenced by their nicknames in survivors’ accounts), but it seems likely that Spanish milicianos were transferred from other sections of the column to bulk up numbers at certain periods. Some, certainly, were with the International Group from early on. As Berry notes, they could also be exiles who followed their new-found comrades into the International Group once they returned home.[27] Italian anarchist volunteers in Spain were more numerous than most other nationalities, but a large proportion of these fought with the Italian Section of the Ascaso Column, hence the disproportionately low number in the Durruti Column.[28] Four Swiss volunteers came to Spain to participate in the People’s Olympiad in Barcelona, the left-wing alternative to the Nazi Olympics in Berlin, joining the militia after this was cancelled.[29] The impressive array of nationalities within the International Group highlights the durability of the anarchist movement despite external pressures during the interwar period. The diversity of volunteers also shows that political solidarity was not limited by national political boundaries.

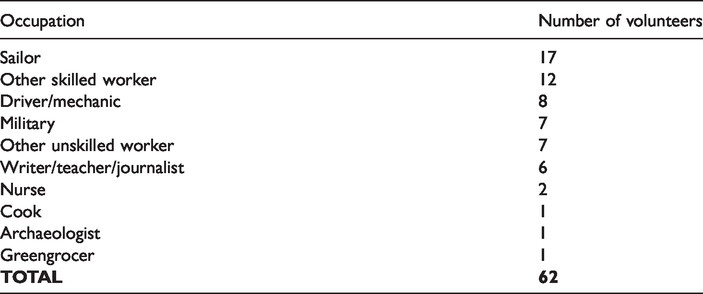

Occupations are known for 62 volunteers, with sailor being the most common occupation (see Table 3). The maritime industry also made up a large number of volunteers for the International Brigades; 500–600 American sailors and longshoremen (the largest single occupational grouping among Americans) served in Spain.[30] Eleven German volunteers in the International Group were members of the International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF) or the International Union of Seamen and Harbour Workers (ISH). Swedish anarcho-syndicalist miliciano Nils Lätt claimed that as ‘a sailor and an Esperantist’ he frequently encountered Spanish comrades and was ‘completely captured by their enthusiasm.’ This was an important factor in his decision to join the International Group.[31] Sailors were also able to jump ship whilst docked in Spain in order to join the militias; this was the case for at least two volunteers: Jewish-American Ed Scheddin and German Franz Wiese.[32]

Another notable grouping is those attached to the military. Three of these were members of the French Foreign Legion. Willi Schroth, who eventually joined the 13th International Brigade, was described by his Comintern superiors as ‘an undisciplined comrade’ and ‘politically highly unreliable, a real foreign legion-type.’[33] Schroth might fit the category of ‘mercenary’ sometimes used to denigrate the pro-Republican cause. Gimenez admitted that ‘many among us had unsettled matters with the police for things unrelated to social struggle,’ but most volunteers appear to have been workers of some category.[34] Skilled workers were the second most common category, followed by drivers or mechanics. Other trade unions represented include the French Confédération Générale du Travail (CGT) and Confédération Générale du Travail-Syndicaliste Révolutionnaire (General Confederation of Revolutionary Trade Unions, CGTSR), the CNT, the Sveriges Arbetares Centralorganisation (Central Organization of the Workers of Sweden, SAC) and the anarcho-syndicalist Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and Freie Arbeiter Union Deutschlands (Free Workers’ Union of Germany, FAUD).[35]

At least 12 volunteers were women, including the French writer and pacifist Simone Weil. Weil had a comparatively brief spell in Spain, after injuring herself by stepping in a pot of boiling oil on the Ebro front. She had initially wanted to cross into enemy territory in order to locate the whereabouts of Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista (Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification, POUM) general secretary Joaquín Maurín, but this was vetoed by the party leadership.[36] As Lisa Margaret Lines argues, the milicianas (female militia members) were ‘a manifestation of the new gender roles and opportunities created by the civil war and social revolution.’[37] They came to symbolize the vitality of the Republican struggle, but, despite the striking images printed in foreign newspapers, they still tended to perform gendered roles within the militia. While on expedition in August 1936, Berthomieu instructed Weil to stay inside a captured farmhouse and cook. Four women were joined by their partners and three acted as nurses or served in the kitchen. Women were also frequently the object of (often unwanted) male miliciano attention, and many of the group’s leaders sought to discourage them from joining the militia. They did still fight, however, and in fact the majority of milicianas in the International Group died in battle. Gimenez recounts in his memoirs the horrific detail that two of them—Augusta Marx and Georgette Kokoczinski—were disembowelled before being killed, but this is difficult to verify. Only one, the Austrian Leopoldine Kokes, survived long enough to be expelled from the column following the order removing women from the front line in early 1937.[38] The fact that women were only active at the front for a few months is indicative of how short-lived these changes in gender roles were. It is also suggestive of the emphasis that both sides in the conflict placed on the ‘mobilizing myth’ of masculinity under arms, although, as James Matthews notes, the Republicans rejected some of the ‘ultra-masculine’ tendencies of the Nationalists.[39]

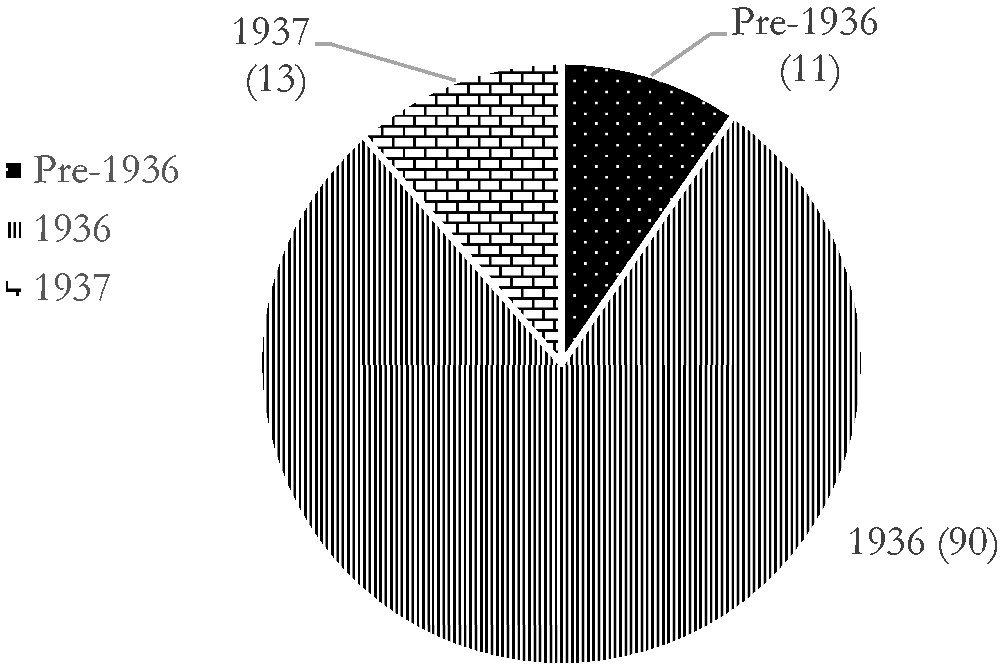

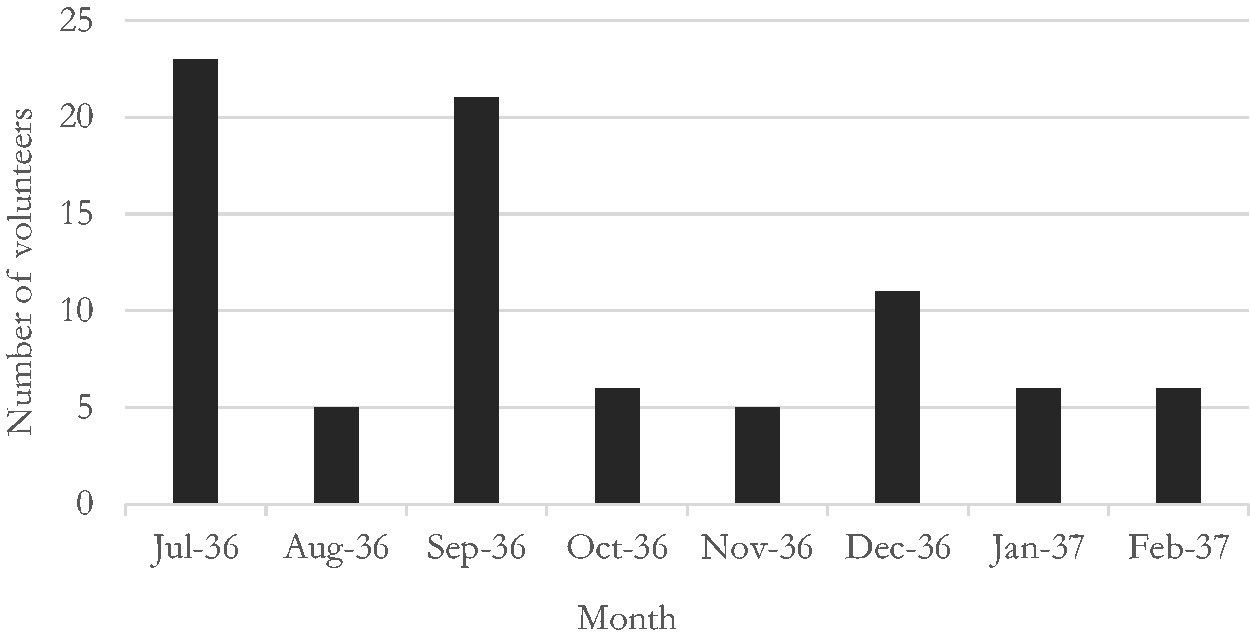

A rough sample of 114 volunteers suggests that most arrived in Spain in 1936, with at least 11 already living in the country before then (Figure 1). A more detailed sample of 83 volunteers indicates that, for those who travelled to Spain after the war’s outbreak, the summer of 1936 was the most popular period for arrival, with numbers tailing off towards the start of 1937 (Figure 2). This is unsurprising, since volunteers arriving from 1937 tended to join the International Brigades, which first fought at Madrid in November 1936. The early months of the war were also the period when the prestige of the Spanish anarchists was arguably highest, so it seems logical that service in a CNT-FAI militia would have been more popular then. The Durruti Column had a reputation among foreigners as a ‘tough outfit,’ and Durruti was well-known in anarchist circles as a seasoned militant.[40]

Later volunteers were discouraged from joining the militias or anarchist-dominated units; indeed, a government decree in June 1937 banned foreigners from service outside the International Brigades. It should also be noted that the recruiting networks of the anarchist movement were far less centralized and sophisticated than those of the Comintern, and anarchists were not actively encouraged to travel. The CNT-FAI was more concerned with arms than recruits, preferring comrades to agitate for an end to non-intervention than come to Spain.[41] In many ways, the informal nature of recruitment to the International Group echoes the experience of other early volunteers who joined the non-anarchist formations that later became incorporated into the International Brigades, once the Comintern gained Stalin’s blessing for more widespread mobilization. When the brigades became more institutionalized, enlistment procedures became more rigorous.[42]

Also like the International Brigades, there was a pluralism of political views within the International Group, with communists (both orthodox and anti-Stalinist), socialists, anarchists and largely apolitical volunteers—even self-professed pacifists—fighting alongside one another. Many had already agitated or been imprisoned for their stance opposing fascism in their own countries. According to Lätt, many of the German volunteers had been sent to concentration camps by the Nazis, or ‘hunted like animals from one “democratic” country to another.’[43] There were at least 33 current or former Communist Party members in the International Group (from parties in Germany, Belgium, Switzerland, France, Estonia and the US), although the actual number is probably higher. Graf and Nelles suggest that as many as 40 per cent of German volunteers were members of the KPD. One group of 18 German volunteers had initially joined the Thälmann Centuria (affiliated to the communist-led Karl Marx Column) but left after Hans Beimler of the KPD replaced their elected political commissar, Kurt Lehmann, with one of Beimler’s own choosing. Lehmann, who had been expelled from the KPD for leading a breakaway group of ITF sailors in Antwerp (for which the party labelled him a ‘Trotskyist’ and ‘Gestapo agent’) then led a similar breakaway group to join the Durruti Column at the end of October 1936.[44]

The Communist Party were critical of the ‘revolutionary proclivities’ (to borrow E.H. Carr’s phrase) of the anarchists, preferring to wage a conventional war to defeat fascism first as opposed to the more widespread social struggle favoured by the CNT-FAI and the POUM. Communist policy thus consisted of rebuilding the Republican state apparatus that had crumbled in the chaotic first weeks following the military rebellion. For this reason, Anglo-Italian anarchist Vernon Richards later described the communists as the ‘spearhead of the counter-revolution in Spain.’[45] A fractious relationship with the party was not uncommon among the International Group; at least six volunteers had either left or been expelled from the party. Two Russian volunteers had fought against the Bolsheviks during the Russian Civil War; one on the side of the Whites, another alongside the Ukrainian anarchist Nestor Makhno. Two German volunteers, Heinrich Eichmann and Georg Gernsheimer, allegedly transferred from the International Brigades after being forcibly released from a communist prison by an FAI commando.[46]

Four volunteers had joined the Socialist Party, one was a member of the Sozialistische Arbeiterpartei Deutschlands (Socialist Workers’ Party of Germany, SAPD), whilst several others allied with the POUM. Political debate within the group was permitted, even encouraged, up to a point. Edi Gmür, a Swiss volunteer, claimed that: ‘Nearly every day there are discussions and arguments between the anarchists and us three communists.’[47] The political delegate of the group, Rudolf ‘Michel’ Michaelis, was particularly eager to propagandize within the group, prompting several Marxist volunteers to join other units in February 1937 after constantly clashing with him over political matters.[48] Despite these quarrels, the relatively high proportion of non-anarchist volunteers within an ostensibly anarchist unit suggests that the sectarian nature of the militias has been overstated somewhat.[49] Anti-fascist unity was far from absolute, as discussed below, but political differences in this anarchist unit, at least, were largely put to one side when the fighting commenced.

Studies of foreign war volunteering (including those in Spain) have focused overwhelmingly on the motivations of the volunteers and the nature of their military service. The relationship between the host state and their transnational fighters has been less well documented, but this can act as a ‘unique litmus test to assess the rhetoric of national causes.’[50] The Spanish Civil War was (and is) often presented as a distinctively internationalist conflict, yet even those on the left who were supposedly hostile to manifestations of nationalism frequently defined the war in explicitly nationalist terms. In a speech to a rally in Madrid in August 1936, for example, leading anarchist Federica Montseny attacked the Nationalists as anti-Spanish, ‘because if they were patriots, they would not have let loose on Spain the regulares [Indigenous Regular Forces] and the Moors to impose the civilisation of the Fascists, not as a Christian civilisation, but as a Moorish civilisation.’[51] The International Group provides insights into how Spaniards, both anarchist and non-anarchist, viewed foreign fighters in Spain. The first of these insights can be gleaned through the internacionales’ views on militarization and, more importantly, the response of their Spanish commanders to them.

The militias were unique among modern armies in their theoretical rejection of military discipline. Instead, they followed what they called ‘revolutionary discipline.’ Rather than simply giving an order, a commander had to convince the troops of the necessity of a certain action. If they disagreed, a vote was often taken, and if the motion failed, the order was revoked. Milicianos also recalled unpopular or incompetent delegates. As Michele Haapamaki notes, the militias were ‘a means for the left to accept a warrior role in Spain without simultaneously accepting the baggage of an outdated military ideal discredited, in their minds, by the Great War.’[52] The inclusion of women at the front was a further challenge to traditional patriarchal military practice, albeit an ultimately fleeting one. The militias were thus an uneasy attempt to juggle between ideological purity and military necessity. Simone Weil witnessed the system first-hand the night before an expedition across the Ebro River in August 1936. Berthomieu asked the International Group for their opinions on the following day’s battle plan: ‘Complete silence. He insists that we say what we think. Another silence. Then [Charles] Ridel: “Well, we all agree.” And that’s all.’[53] Clearly, not all decisions were hotly debated within the group.

Even so, this haphazard structure horrified traditionalists, and historians tend to view the militia system with extreme scepticism.[54] As Ángel Viñas notes, the Republic’s primary benefactors, the Soviets, were also uncomfortable with providing military hardware to units seemingly beyond the authority of either the central or regional Catalan governments.[55] The Republican high command’s preferred solution to this problem was to bring the militias under the control of the central government—as opposed to the various workers’ parties and unions—and introduce military hierarchy and discipline. The militarization drive began in September and October 1936 with a series of decrees by Prime Minister Francisco Largo Caballero that established, firstly, a unified command and, eventually, the incorporation of the militias into the regular army. This drive continued until the last of the militia units succumbed to the new regime, the final one being the anarchist Columna de Hierro (Iron Column) in March 1937.[56]

Like the wider anarchist movement, volunteers in the International Group devoted much time to debating the merits and drawbacks of militarization. For its defenders, the militia system maintained the revolutionary integrity of the war. Art critic Carl Einstein, speaking on Radio CNT-FAI to eulogize Durruti in November 1936, said that the column was ‘neither military nor bureaucratically organised,’ but had ‘grown organically from the syndicalist movement.’[57] As it liberated territory from the Nationalists, the column encouraged (or forced, depending on your point of view) peasants to collectivize their land, striking a blow not only against the military but the capitalist enemy. Caciques (large landowners), clergy and Francoist sympathizers were shot, land registers burned, tools placed under common ownership and, in many places such as Pina de Ebro, money abolished. Julián Casanova describes this process as ‘the radical elimination of the symbols of power, be they military, political, economic, cultural or ecclesiastical.’[58] For Einstein, then, the militias were no less than ‘the exponents of the class-struggle.’[59] Artillery colonel Ricardo Jiménez de Beraza, the military adviser to the Durruti Column, argued that ‘Militarily, it’s chaos, but it’s a chaos that works. Don’t disturb it!’[60]

Other volunteers were less convinced. Weil gave an assessment of the arrangement in her diary: ‘Organisation: elected delegates. Without competence. Without authority…Peasants complain…that the sentries fall asleep.’[61] Two milicianos were executed on the orders of the chairman of the column’s war committee, the Argentine Lucio Ruano, for retreating and abandoning their weapons during a battle in December 1936.[62] After a meeting on militarization later that month, the Swiss volunteer Edi Gmür wrote in his diary that he ‘had difficulty grasping that they could be arguing about something so urgently needed.’[63] German volunteer Arthur Galanty criticized the ‘absolute incompetence and irresponsibility of the headquarters, the missing of officers that are capable to lead the company, the lack of arms and the inadequate instruction of the people’ manifested in the militias.[64]

Even those in favour of militarization, however, had reservations. According to a letter sent from the German grouping (affiliated to the DAS), many anarchists were unhappy with the top-down nature of militarization, without any dialogue between the troops and those creating the new military code. In their own suggestions, the DAS viewed the symbolic gesture of saluting to officers as their number one priority. This was hugely controversial to anarchists and seen as an acceptance of authoritarian, regressive structures. In addition, the DAS emphasized freedom of the press and freedom of discussion as important guarantees in any new military code.[65] This was less of a symbolic issue than saluting, but reflected a worry among anarchists that by losing control of their militias they could find themselves subject to repression, as well as emphasising the role of the militias as a vehicle for political education.

The reaction of some Spanish anarchists to the concerns of their international comrades was unhelpful. The International Group, in accordance with previous agreements, had the right to appoint a delegate to represent them after militarization was complete. The new general delegate of the column, José Manzana, however, informed the internacionales that general headquarters no longer recognized their delegate. The group then published a manifesto on 10 January 1937 calling for autonomy for delegates to act on matters directly concerning them and requested accreditation to take the manifesto to the regional committee of the CNT in Barcelona. Manzana denied the request, replying ‘Barcelona, soy yo’ (‘I am Barcelona’). He then banned any more meetings on the subject and informed the group that they could either submit to the new regime or be discharged. Consequently, 49 (mainly French) milicianos left the front. Following the acceptance of militarization in January 1937, the International Group became known as the International Company of the 26th (Durruti) Division.[66]

This episode highlights the often ambivalent attitude of the Spanish movement to international anarchists within Spain. Helmut Rüdiger, who served as assistant secretary of the International Workingmen’s Association (IWMA) for Spanish affairs during the war, characterized the CNT (affiliated to the IWMA) as a ‘national socialist movement’ that had only the ‘terminology of the common program’ of the international anarchist movement.[67] Certainly, some Spanish anarchists were unimpressed by the International Group’s requests for a level of independence from wider (national) structures, regardless of their contribution to the anti-fascist cause. Transnational units were ultimately subservient to the Spanish organization (the CNT) under whose banner they fought. This was also true of the International Brigades, even if some volunteers claimed that as foreigners they were not under the jurisdiction of the Spanish Republican Army.[68] Manzana’s reaction is even more surprising when we consider that in his own correspondence to CNT headquarters, he identified the tactless imposition of militarization as the primary reason behind a drop in morale within the column.[69] He was clearly aware of the adverse effects of the issue on Spanish anarchists but seems ambivalent to these same concerns when voiced by foreigners. Ultimately, the process of militarization was one of centralization, but it was also one of nationalization—one which sought (among other things) to ‘dilute’ the importance of foreign volunteers.[70]

The simmering tensions between the different wings (broadly speaking, statist and anti-statist) of the anti-fascist camp, of which militarization was a key part, came to a head in the infamous ‘May Days’ of 1937. During this outburst of fratricidal conflict, anarchists and their allies fought against supporters of the Republican government (including the communists) throughout Catalonia. The International Group was on leave in Barcelona when the fighting began on the 3rd of May and became embroiled in subsequent events. One volunteer, Francisco Ferrer (using the pseudonym Jean Ferrand), the grandson of the famous anarchist educator of the same name, was murdered on the street for refusing to relinquish his rifle. Camillo Berneri, who had organized the Sezione Italiana of the Ascaso Column, was assassinated (most likely by communists) alongside his comrade Francesco Barbieri, causing widespread shock among the international anarchist community. After a week of fighting and repeated appeals from the leadership of both sides to cease hostilities, 218 people lay dead, with hundreds more injured.[71]

In the subsequent roundup, international anarchists became the target of the Republican authorities. In June 1937, a contingent of 50 police officers twice raided the Casa International de Voluntarios, the headquarters of foreign anarchist volunteers in Barcelona. Martin Gudell of the CNT-FAI Foreign Language Division believed that the officers were searching for weapons, but did not find any.[72] Several foreign volunteers were arrested for their activities during the May Days; indeed, what is striking about the International Group is how many of them were subsequently arrested by Republican authorities: at least 31 volunteers (over 8 per cent). They included FAUD member Helmut Kirschey, who the Comintern accused of shooting communists during the fighting and described as a ‘counter-revolutionary element ready for all political crimes.’[73] Swiss socialist Jacop Aeppli was arrested in July 1937 and subsequently ‘disappeared’—his wife was told in December that he had died in an ‘unknown manner.’[74] Also in July 1937, the International Group (which by now had been reorganized as the IWMA Battalion) refused to mount an attack on Quinto without adequate air or artillery support, as did four Spanish battalions. Headquarters (‘beside themselves with anger,’ according to Gmür) then made the decision to disband the IWMA Battalion, marking the end of (semi)independent foreign anarchist participation in the war.[75]

Following the collapse of the International Group and the decree outlawing foreign service in Spanish units, many volunteers transferred to the International Brigades. At least one International Group member, Rudolf Michaelis, obtained Spanish citizenship so that he could continue to serve in an anarchist unit.[76] Some volunteers found the change relatively seamless: Emanuel Fischer, a KPD member since 1931, appears to have been unaware of the anarchist nature of the Durruti Column when he joined in August 1936. He later transferred to the International Brigades, where he was promoted to sergeant.[77] Another volunteer, Norbert Rauschenberger, joined the brigades in August 1937 and eventually became lieutenant and company commander.[78] The fact that so many International Group volunteers later joined the brigades suggests that many rank-and-file militants made little distinction between the anti-fascism of the Comintern-led unit and the ‘revolutionary’ anti-fascism of the militias. Indeed, around half of the anarchists who came to Spain from the United States, Britain and Ireland during the course of the war served in the brigades, many without prior service in anarchist units.[79] This fluidity in self-identification did not mean, however, that they received the same treatment from their superiors as other volunteers. Military setbacks within the brigades were frequently seen as a result of political failings: a report for the 15th Brigade complained that military questions were not given ‘political answers,’ and senior Comintern agents viewed a lack of political consciousness as a key reason for the Republican reversal at Brunete in July 1937.[80] Military reliability went hand in hand with political orthodoxy.

As a result of this perception (combined with the fact that they had not been previously ‘vetted’ through official channels), anarchist volunteers were kept under close watch by the brigade authorities, with several imprisoned for indiscipline, political subversion, even treason. Oskar Heinz was sentenced to two and a half months in prison for causing ‘dissent’ and making anarchist propaganda within the brigades. Johann Schwarz was sent to a punishment battalion for indiscipline and allegedly recruiting deserters. Some of the assertions in the Comintern files verge on the fantastic. Fritz Vogt, for example, was arrested on suspicion of counter-revolutionary activities because he often ate in restaurants with those under police surveillance. Five volunteers were accused of being Gestapo agents, with scant evidence. Some Comintern agents assumed that any connection with the POUM meant collusion with German intelligence; this was the reason for poumista Hermann Gierth’s arrest after joining the brigades in 1937.[81] Paul Preston argues that the internationalist nature of the POUM—which supposedly made them more susceptible to infiltration by foreign agents—placed them under suspicion from the authorities. Yet at the same time we must acknowledge, as Tom Buchanan does, that for many in the Communist Party, anti-Trotskyism was a key part of their anti-fascism, with all the ugly consequences this entailed.[82] Foreign anarchists similarly fell under the suspicion of heterodoxy, and although many volunteers were able to remain inconspicuous, others were less lucky.

The mass arrests and resultant disarming of the rearguard after May 1937 was, as James Yeoman notes, the final act in the ‘reassertion of “social order” over “revolutionary order” in Republican Spain.’[83] The existence of both the revolutionary militias and the land and factory collectivisations of earlier in the war (enabled in many places by those same militias) were anathema to those wishing to fight a conventional military conflict. The targeting of foreign anarchists shows how, like their Spanish comrades, they too were viewed as ‘uncontrollable’ by the Republican government. In this case, the dividing lines between rival factions of the anti-fascist camp also cut across national lines.

Post-conflict trajectories of foreign volunteers have been of ‘secondary concern’ in many studies of transnational fighters.[84] This is unfortunate, since it isolates the experience of war volunteering from the wider societal context in which the volunteers found themselves. This can tell us more about how states deal with demobilized transnational fighters, but also the potentially radicalizing and/or demoralizing impact of foreign military service. In general, the story of the International Group volunteers at the war’s end is a sombre one. The attitude of states both democratic and authoritarian towards combatants from Spain ranged from suspicion to outright hostility. This was largely irrespective of their political background; even the Soviet Union effectively abandoned its communist cadres after 1939.[85] Foreign volunteers in Spain (particularly exiles) were what Nir Arielli calls ‘substitute-conflict volunteers, who see service in a conflict abroad as a precursor to fighting the regime in their home state.’ This meant that—to other states—they were potentially troublesome, and the intricacies of Republican war policy mattered little.[86]

Like thousands of other Spanish refugees and foreigners, International Group volunteers who survived the end of the war were often held in concentration camps in southern France or North Africa. Somewhat remarkably, seven German volunteers ended up in the same camp in Gurs in 1940.[87] At least 20 volunteers spent time in the camps, including the only Portuguese volunteer, Julio Mescareuhas (described by the authorities as a ‘bitter enemy’ of the Communist Party).[88] Most of them were held in southern France, but one, Alfred Berger, was captured by the Nationalists and taken to the infamous San Pedro de Cardeña prisoner of war camp.[89] Carl Einstein’s story is perhaps the most tragic. Having been imprisoned briefly in the south of France for his role as a civil war combatant, he came to Paris, but after the start of the Second World War he was interned as an enemy alien in a camp near Bordeaux. He managed to escape, but following the fall of France, he was now subject to persecution as a Jew. He fled to the south again, but, having given up all hope of escaping across the Pyrenees, he drowned himself in a river flowing through the village of Lestelle-Bétharram.[90]

Following the defeat of the Republican cause, several volunteers’ anti-fascist pasts came back to haunt them. Former KPD member Helmuth Bruhns was handed over to the Gestapo by the Vichy Regime in 1941 and sentenced to 15 years imprisonment. Kurt Lehmann, who before 1936 had helped to smuggle Jews from Germany to Britain and the US, soon found himself under intense scrutiny. Having returned to Belgium with his brother Werner (also an International Group member) in 1937, the pair were arrested and expelled from the country in 1938. After several more arrests in France and an unsuccessful attempt to enter Britain, the brothers were delivered to the Nazis. Werner’s arteries were cut and he bled to death (it is unclear whether this was a suicide or an execution), whilst Kurt survived Gestapo torture and was sent to various prisons in Germany before being liberated by the US Army on his way to Dachau concentration camp. He became disillusioned with postwar West Germany and declared that it was ‘not worth fighting for these people’ towards the end of his life.[91]

Other volunteers were able to continue their fight against fascism. Belgian communist Mathieu Corman joined the French Resistance, launching sabotage operations in southern France until his capture whilst in Barcelona in 1942. He was later released and returned to Belgium. French communist Aimé Turrel, after supporting his party’s endorsement of the Nazi-Soviet Pact, also eventually joined the French Resistance.[92] Fritz Benner enrolled in the Norwegian Resistance and was arrested for espionage by the Swedish authorities in April 1940, alongside fellow International Group volunteers Hans Vesper and Karl Löshaus. Olov Jansson worked with the Swedish Resistance, co-founding the Swedish-Norwegian Press Bureau in Stockholm alongside SAPD member and future Chancellor of West Germany Willy Brandt (who had also spent time in Spain). Jansson later moved to Britain and became a journalist with the BBC.[93] French Algerian volunteer Saïl Mohamed, who at one point led the International Group before being wounded, produced counterfeit papers for Algerian workers during the German occupation of France, and after 1945 agitated against French colonialism through the UA and its successor, the Fédération Anarchiste.[94] It is clear, then, that for these volunteers their experience in Spain did not dampen their enthusiasm for the cause. There was a continuity between interwar and wartime anti-fascism; it may be more useful for many volunteers, even, to characterize the entire period from 1933 to 1945 as one of transnational anti-fascist resistance.[95]

As a military unit, the International Group of the Durruti Column was relatively insignificant. It survived less than a year (under six months as part of an ‘unmilitarized’ column), and probably contained no more than a hundred individuals at any given time. Service was short; few volunteers served from its inception in August 1936 all the way through until its dissolution in July 1937. Nevertheless, the group is a microcosm of anti-fascist activity during the interwar period. It was a moment of activism for many volunteers, but this activism extended both before and after the Spanish Civil War. Most German volunteers had a history of anti-Nazism well before Spain, and others continued their activism well into the Second World War and beyond. The decision to come to Spain, in most cases, was not exceptional, but a logical extension of a wider political commitment. As the co-founder of the International Group Charles Ridel later wrote:

To many of the revolutionaries who rushed to a Spain in flames and in battle, it was not an aspiration but the ultimate sacrifice relished as a gauntlet thrown down to a complicated world that made no sense, as the tragic outworking of a society wherein human dignity is trampled underfoot day in and day out.[96]

This fight crossed and re-crossed national boundaries, showing that anti-fascism in the 1930s was not only an international, but transnational phenomenon. The fluidity of national borders encapsulated in the group is mirrored by a diversity of political views, from anarchists, communists and socialists to generic anti-fascists. In a sense, then, the Spanish Civil War acted as an ‘anti-fascist melting pot,’ where anti-fascists of different stripes came together. For many volunteers, this experience reinforced their own anti-fascist identity, whilst for others Spain was the peak of their anti-fascist commitment.[97]

Unlike most of those who fought with the International Brigades, milicianos in the International Group witnessed first-hand the debates over militarization, women at the front and arguably the most controversial episode of the civil war: the May Days and subsequent repression. The difference in views over militarization between members of the group is an antidote to the idea that all rank-and-file anarchists were hostile to the process, even if many were unhappy with its execution. The reaction of the CNT to the International Group’s concerns also helps us to gauge the overall treatment of non-Spaniards by Spaniards during the civil war period, and questions the characterization of the conflict as distinctively internationalist. Militarization was a centralizing, but also a nationalizing (and masculinizing) process, something which became more explicit when non-Spaniards were banned from serving in Spanish units. The heightened repression of foreigners after the May Days was, similarly, a political attempt by state forces to counter the revolutionary internationalism of anarchist volunteers. It would be facile to assert that Spaniards did not appreciate the efforts of these international milicianos. There was, nevertheless, an underlying tension between Spaniards and non-Spaniards throughout the course of the war, symptomatic of a tendency of the former to characterize the war in national terms.[98]

Although differences between foreign service in the Durruti Column and the International Brigades have been highlighted, we should also recognize their similarities. Initial mobilizations shared several features, although these diverged as the Comintern took greater control over recruitment. Many volunteers fought in both formations, and at the war’s end, many faced similar perils. Like foreign volunteers in other conflicts, they may have become caught up in political intrigues during the war, but there was a shared commitment to the cause regardless of the tensions caused by differing ideological viewpoints.[99] Equally, though, this shared commitment had its limits: for many anarchists, militarization marked the end of their foreign service, whilst for others, being ordered to fight under unacceptable combat conditions at Quinto was the final straw. The International Brigades had problems maintaining morale too, particularly after bloody reverses like at Jarama in February 1937.[100] The propensity to characterize the Spanish Civil War as a romantic conflict—symbolic of a transnational commitment to defeat fascism during a period of profound societal uncertainty—can seem irresistible, but service for foreign volunteers was significantly less rosy than is frequently depicted. Internationalist anti-fascist rhetoric was often curtailed by nationalist practice. Through studying these transnational fighters, we have a more comprehensive understanding of the complex nature of twentieth century anti-fascism.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Fern Towers for her comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript and the Belfast Anarchist Bookfair for hosting a talk based on the paper in 2019.

Biographical Note

Morris Brodie is a historian at Queen’s University Belfast. He achieved a BA in History and Politics (First Class Honours) from the University of Strathclyde in 2013 before completing his MSc in History (with Distinction) at the University of Glasgow in 2014. He received his PhD at Queen’s in 2018. He specialises in the history of international anarchism during the interwar period and has published his research in several journals, including Radical Americas, Anarchist Studies and the Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth. His first book, Transatlantic Anarchism during the Spanish Civil War and Revolution, 1936–1939: Fury Over Spain, is available now as part of Routledge’s Studies in Modern European History series. He is currently researching Spanish anarchist exiles in Britain after the civil war.

[1] For the International Brigades, see R. Baxell, British Volunteers in the Spanish Civil War: The British Battalion in the International Brigades, 1936–1939 (London 2004); A. Castells, Las brigadas internacionales en la guerra de España (Barcelona 1974); P. N. Carroll, The Odyssey of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade: Americans in the Spanish Civil War (Stanford, CA 1994); M. Jackson, Fallen Sparrows: The International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War (Philadelphia, PA 1994); B. Mugnai, Foreign Volunteers and International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War (1936–39) (Zanica 2019); R. D. Richardson, Comintern Army: The International Brigades and the Spanish Civil War (Lexington, KN 1982). For foreign anarchists, see D. Berry, ‘French Anarchists in Spain, 1936–1939,’ French History, 3, 4 (December 1989), 427–65; D. Nelles, ‘Deutsche Anarchosyndikalisten und Freiwillige in anarchistischen Milizen im Spanischen Bürgerkrieg,’ Internationale Wissenshaftlich Korrespondenz zur Geschichte der deutschen Arbeiterbewegung, 4 (1997), 500–19; A. Graf and D. Nelles, ‘Widerstand und Exil deutscher Anarchisten und Anarchosyndikalisten (1933–1945),’ in R. Berner (ed.), Die unsichtbare Front: Bericht über die illegale Arbeit in Deutschland (1937) (Berlin and Cologne 1997), 50–152; K. Zimmer, ‘The Other Volunteers: American Anarchists and the Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939,’ Journal for the Study of Radicalism, 10, 2 (Fall 2016), 19–51; T. R. Nevin, Simone Weil: Portrait of a Self-Exiled Jew (Chapel Hill, NC 1991); S. Zeidler, Form as Revolt: Carl Einstein and the Ground of Modern Art (Ithaca, NY 2015).

[2] N. Arielli and B. Collins, ‘Introduction: Transnational Military Service since the Eighteenth Century,’ in N. Arielli and B. Collins (eds), Transnational Soldiers: Foreign Military Enlistment in the Modern Era (Basingstoke 2013), 5.

[3] For simplicity’s sake I refer to the company as the ‘International Group’ throughout.

[4] Anonymous, ‘Die Internationale Gruppe,’ Die Soziale Revolution (1 January 1937).

[5] See N. Arielli, ‘Foreign Fighters and War Volunteers: Between Myth and Reality,’ European Review of History, 27, 1–2 (March 2020), 54–64.

[6] M. N. Ngae, ‘Promises and Perils of Transnational History,’ Perspectives on History, 50, 9 (December 2012). Available online at: https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/december-2012/the-future-of-the-discipline/promises-and-perils-of-transnational-history (accessed 17 June 2015).

[7] H. García, ‘Transnational History: A New Paradigm for Anti-Fascist Studies,’ Contemporary European History, 25, 4 (November 2016), 566. See M. Seidman, Transatlantic Antifascisms: From the Spanish Civil War to the End of World War II (Cambridge 2017); H. Graham, Lives at the limit: Dealing with Defeat in the Dark Twentieth Century (provisional title, in preparation as of 2020). The Leverhulme Trust-funded international research network entitled ‘Transnational Resistance, 1936–1948’ is headed by Gildea and comprises academics from seven institutions across Europe. See also K. Braskén, N. Copsey and J. A. Lundin (eds), Anti-fascism in the Nordic Countries: New Perspectives, Comparisons and Transnational Connections (London 2019).

[8] J. Marco, ‘Transnational Soldiers and Guerrilla Warfare from the Spanish Civil War to the Second World War,’ War in History, 27, 3 (July 2020), 387–407; L. A. Kirschenbaum, International Communism and the Spanish Civil War: Solidarity and Suspicion (Cambridge 2015). See also N. Arielli and E. Acciai, ‘Trajectories of Transnational Antifascist Volunteers from the Spanish Civil War to the Second World War,’ War in History, 27, 3 (July 2020), 341–5 and the remainder of this special issue. On the prevalence of communists in the anti-fascist narrative, see H. García, M. Yusta, X. Tabet and C. Clímaco, ‘Beyond Revisionism: Rethinking Antifascism in the Twenty-First Century,’ in H. García, M. Yusta, X. Tabet and C. Clímaco (eds), Rethinking Antifascism: History, Memory and Politics, 1922 to the Present (New York 2016), 3–5; N. Copsey and A. Olechnowicz (eds), Varieties of Anti-Fascism: Britain in the Interwar Period (Basingstoke 2010), particularly the preface.

[9] C. Bantman and B. Altena, ‘Introduction: Problematizing Scales of Analysis in Network-Based Social Movements,’ in C. Bantman and B. Altena (eds), Reassessing the Transnational Turn: Scales of Analysis in Anarchist and Syndicalist Studies (New York 2015), 7.

[10] See, for example, J. Casanova, Anarchism, the Republic and Civil War in Spain: 1931–1939 (London 2005) and De la calle al frente: El anarcosindicalismo en España (1931–1939) (Barcelona 2010); C. Ealham, Class, Culture and Conflict in Barcelona, 1898–1937 (London 2005); D. Evans, Revolution and the State: Anarchism in the Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939 (London 2018); F. Godicheau, La Guerre d’Espagne: République et revolution en Catalogne (1936–1939) (Paris 2004); D. Marín Silvestre, Ministros anarquistas. La CNT en el gobierno de la 11a República (1936–1939) (Barcelona 2005); J. Peirats, La CNT en la revolución española, 3 Vols (Toulouse 1951–3).

[11] E. Acciai, Antifascismo, volontariato e guerra civile in Spagna. La Sezione Italiana della Colonna Ascaso (Milan 2016); The Giménologues (eds), The Sons of Night: Antoine Gimenez’s Memories of the War in Spain (Edinburgh 2019).

[12] See M. Brodie, ‘Crying in the Wilderness? The British Anarchist Movement during the Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939,’ Anarchist Studies, 27, 2 (Autumn 2019), 21–40. Further information can be found in C. Dolan, An Anarchist’s Story: The Life of Ethel MacDonald (Edinburgh 2009); M. Feu, Fighting Fascist Spain: Worker Protest from the Printing Press (Urbana, IL 2019); D. Porter, Vision on Fire: Emma Goldman on the Spanish Revolution (Edinburgh 2006).

[13] J. A. Baer, Anarchist Immigrants in Spain and Argentina (Urbana, IL 2015); M. A. Ackelsberg, ‘It Takes More than a Village!: Transnational Travels of Spanish Anarchism in Argentina and Cuba,’ International Journal of Iberian Studies, 29, 3 (September 2016), 205–23; F. Borkenau, The Spanish Cockpit (London 1937), 273; P. Preston, The Spanish Civil War: Reaction, Revolution and Revenge (London 2006), 170–1.

[14] M. Alpert, ‘The Popular Army of the Spanish Republic, 1936–39,’ in W. H. Bowen and J. E. Alvarez (eds), A Military History of Modern Spain: From the Napoleonic Era to the International War on Terror (Westport, CT 2007), 97–8; M. White, ‘Wobblies in the Spanish Civil War,’ Anarcho-Syndicalist Review, 42/3 (Winter 2006), 42; Anonymous, ‘Un vecchio milite della colonna Ascaso,’ Il Martello (21 February 1938); D. Nelles, The Foreign Legion of the Revolution: German Anarcho-syndicalist and Volunteers in Anarchist Militias during the Spanish Civil War (2008), available online at: https://libcom.org/library/the-foreign-legion-revolution (accessed 24 January 2020); A. Souchy, Nacht über Spanien: Anarcho-Syndikalisten in Revolution und Bürgerkrieg 1936–1939 (Grafenau 1986), 181. It should be noted that anarchist sources were inclined to inflate their own numbers: Casanova, Anarchism, the Republic and Civil War in Spain, 109.

[15] P. Broué and É. Temime, The Revolution and the Civil War in Spain (London 1970), 67; J. Peirats, The CNT in the Spanish Revolution, Vol. 1 (Hastings 2001), 97; S. Christie, We, the Anarchists! A Study of the Iberian Anarchist Federation (FAI), 1927–1937 (Hastings 2000), 78; A. Paz, Durruti in the Spanish Revolution (Oakland, CA 2006), 759; ‘Salvo Conducto’ for Sylvan Oziol, 10 February 1937 (Archivo General de la Guerra Civil Española, Salamanca, Político-Social Madrid, Carpeta 321, Legajo 2954); B. Belcher, Shipwreck on Middleton Reef: The Story of a Tasman survivor (Auckland 1979), 18; J. Albrighton, ‘Spain Diaries,’ 5 October 1936 (Marx Memorial Library, London, Spanish Collection, Box 50, File Al/12).

[16] J. Mira, Los Guerrilleros Confederales: Un hombre: Durruti (Barcelona 1938), 102–3; Paz, Durruti in the Spanish Revolution, 473; Richardson, Comintern Army, 22. For more on the militias, see G. Berger, Les milícies antifeixistes de Catalunya. Voluntaris per la llibertat (Vic 2018); R. Brusco, Les milícies antifeixistes i l’exèrcit popular a Catalunya (Lérida 2003); E. Romero García, El ejemplo de la columna Durruti: De milicianos libertarios a soldados del ejército popular de la República (Bilbao 2017).

[17] Paz, Durruti in the Spanish Revolution, 486; Berry, ‘French Anarchists in Spain,’ 445; C. Marzani, The Education of a Reluctant Radical, Book 3: Spain, Munich, and Dying Empires (New York 1994), 20.

[18] In particular: List of comrades in International Group of Durruti Column, n.d. (IISH, Archivo de la Propaganda Exterior CNT-FAI (FAIPE), 1C.3b); ‘Ermittelungen ueber die von der Gruppe DAS controlierten Kameraden in der Miliz,’ 20 January 1937 (IISH, FAIPE, 1B.2); ‘Liste del Miliciens Français,’ n.d. (IISH, FAIPE, 20.3c). Memoirs and first-hand accounts include: The Giménologues, The Sons of Night; E. Gmür, Spanish Diary: A Swiss ‘Miliciano’s’ War Diary of the Aragón Front and Barcelona’s ‘May Days,’ trans. Paul Sharkey (Hastings 2015); N. Lätt, Som Milisman och Kollektivbonde i Spanien (Stockholm 1938); Mira, Los Guerrilleros Confederales; P. and C. Thalmann, Combats pour la liberté (Quimperlé 1997); S. Weil, Le Journal d’Espagne de Simone Weil [Bonnes Feuilles], 18 August 1936 [2018], available online at: https://lundi.am/Le-journal-d-Espagne-de-Simone-Weil-Bonnes-feuilles (accessed 24 January 2020). I have also incorporated studies that mention individual volunteers but which do little to assess the International Group in its broader context.

[19] Berry, ‘French Anarchists in Spain,’ 445–6, 461–2; Anonymous, ‘Die Internationale Gruppe,’ Die Soziale Revolution (1 January 1937); Paz, Durruti in the Spanish Revolution, 488; The Giménologues, The Sons of Night, 69. Foreign milicianos were frequently used as shock troops, which often led to heavy casualties (the Battle of Perdiguera in October 1936 was particularly bloody). This has parallels with the International Brigades, which suffered higher casualty rates than both local troops and foreigners serving under Franco (and, indeed, Allied losses in both World Wars): N. Arielli, From Byron to bin Laden: A History of Foreign War Volunteers (Cambridge, MA 2017), 157.

[20] Paz, Durruti in the Spanish Revolution, 486–8; The Giménologues, The Sons of Night, 107; D. Nelles, Widerstand und internationale Solidarität: Die Internationale Transportarbeiter-Föderation (ITF) im Widerstand gegen den Nationalsozialismus (Essen 2001), 196; Zeidler, Form as Revolt, 6–7; Gmür, Spanish Diary, 2 March 1937.

[21] C. J. Esdaile, The Spanish Civil War: A Military History (London 2019), 103. Indeed, there is some evidence to suggest that Lamotte was in fact a communist spy, although seemingly not a very good one. According to his Comintern file, he was sent to the column on the orders of the German Communist Party but was subsequently reassigned to the 27th (formerly Karl Marx) Division in 1937. Although brave and disciplined, he had a drinking problem, and his membership was not transferred to the Spanish Communist Party. In hindsight, the election of Cardeur also seems ill-judged; in July 1937, he was imprisoned for siphoning money from the column’s payroll: Lists with characteristics, biographies of German volunteers (K–Q), 14 February 1940 (RGASPI 545/6/352/59); Gmür, Spanish Diary, 2 March, 15–16 July 1937.

[22] Paz, Durruti in the Spanish Revolution, 473, 486–8; Weil, Le Journal d’Espagne de Simone Weil, 18 August 1936; Anonymous, ‘Die Internationale Gruppe,’ Die Soziale Revolution (1 January 1937); The Giménologues, The Sons of Night, 51. French was also the lingua franca of many early volunteers who joined the International Brigades: J. Marco and M. Thomas, ‘“Mucho malo for fascisti’: Languages and Transnational Soldiers in the Spanish Civil War,’ War & Society, 38, 2 (May 2019), 143.

[23] 23 The Giménologues, The Sons of Night, 51; Lätt, Som Milisman och Kollektivbonde i Spanien, 13; Marco and Thomas, ‘Mucho malo for fascisti,’ 158–60.

[24] Berry, ‘French Anarchists in Spain,’ 433; The Giménologues, The Sons of Night, 238, 336; ‘Liste del Miliciens Français,’ n.d. (IISH, FAIPE, 20.3c); Lätt, Som Milisman och Kollektivbonde i Spanien, 8; A. Beevor, The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936–1939 (London 2006), 141; Anonymous, ‘Die Internationale Gruppe,’ Die Soziale Revolution (1 January 1937); Zimmer, ‘The Other Volunteers,’ 30, 47.

[25] R. Skoutelsky, L’Espoir guidait leurs pas: Les volontaires français dans les Brigades internationales, 1936–1939 (Paris 1998), 330; Nelles, Widerstand und internationale Solidarität, 197. Although much smaller in number than that of Spain, the French anarchist movement was probably the second most powerful in Europe at the time. Alexandre Skirda calls France the ‘homeland of anarchy’ and Paris was a popular location for anarchist exiles escaping repression in other countries such as the Soviet Union: A. Skirda, Facing the Enemy: A History of Anarchist Organization from Proudhon to May 1968 (Edinburgh 2002), 144, 118–22. See also D. Berry, A History of the French Anarchist Movement, 1917–1945 (Westport, CT 2002).

[26] J. McLellan, Antifascism and Memory in East Germany: Remembering the International Brigades 1945–1989 (Oxford 2004), 18–9; Nelles, The Foreign Legion of the Revolution. The German anarchist movement had been relatively influential in the early twentieth century, with several anarchists involved in the short-lived Bavarian Soviet Republic in 1919. The FAUD had a membership of 150,000 at its peak but was suppressed following the Nazi seizure of power in 1933. After this, most German anarchists were either arrested, went underground or fled the country: see G. Kuhn (ed.), All Power to the Councils! A Documentary History of the German Revolution of 1918–1919 (Oakland, CA 2012), 167–263; H. M. Bock, ‘Anarchosyndicalism in the German Labour Movement: A Rediscovered Minority Tradition,’ in M. van der Linden and W. Thorpe (eds), Revolutionary Syndicalism: An International Perspective (Aldershot 1990), 59–80; A. Graf, Anarchisten gegen Hitler: Anarchisten, Anarcho-Syndikalisten, Rätekommunisten in Widerstand und Exil (Berlin 2001).

[27] A. Searle, ‘The German Military Contribution to the Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939,’ in G. Johnson (ed.), The International Context of the Spanish Civil War (Newcastle-upon-Tyne 2009), 136–7; Jackson, Fallen Sparrows, 105; The Giménologues, The Sons of Night, 96–9; Berry, ‘French Anarchists in Spain,’ 432.

[28] The Sezione Italiana was formed on the initiative of socialist anti-fascist Carlo Rosselli and the anarchist Camillo Berneri, who also published the journal Guerra di Classe: R. Alexander, The Anarchists in the Spanish Civil War, Vol. 2 (London 1999), 1135–6; The Giménologues, The Sons of Night, 236–7; E. Acciai, ‘L’esperienza della Rivista «Spain and the World». La guerra civile spagnola, l’antifascismo europeo e l’anarchismo,’ in C. De Maria (ed.), Maria Luisa Berneri e l’anarchismo ingles (Reggio Emilia 2013), 76.

[29] The Giménologues, The Sons of Night, 11–2, 387. See also P. Huber and N. Ulmi, Les Combatants suisses en Espagne républicaine, 1936–1939 (Lausanne 2001).

[30] J. Byrne, ‘From Brooklyn to Belchite: New Yorkers in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade,’ in P. N. Carroll and J. D. Fernandez (eds), Facing Fascism: New York and the Spanish Civil War (New York 2007), 75.

[31] Lätt, Som Milisman och Kollektivbonde i Spanien, 3–7.

[32] Notebook of Volunteers, 1936–1937 (IISH, FAIPE, 15A.2); Carroll, The Odyssey of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, 61; Nelles, Widerstand und internationale Solidarität, 196–7.

[33] Lists with characteristics, biographies of German volunteers (R–S), 28 February 1940 (RGASPI 545/6/353/99).

[34] The Giménologues, The Sons of Night, 135. For example: Anonymous, ‘Britons Lured to Red Front,’ Daily Mail (18 February 1937). See Kirschenbaum, International Communism and the Spanish Civil War, 106.

[35] The CGTSR was a split from the reformist CGT and had a membership of around 4,000 during the late 1930s. Its organ, Le Combat Syndicaliste, had approximately 5,300 subscribers: Berry, ‘French Anarchists in Spain,’ 428–34; W. Thorpe, Anarchosyndicalism in Inter-war France: The Vision of Pierre Besnard (2011), available online at: https://libcom.org/library/anarchosyndicalism-inter-war-france-vision-pierre-besnard-%E2%80%93-wayne-thorpe (accessed 24 January 2020). For the SAC and IWW, see L. K. Persson, ‘Revolutionary Syndicalism in Sweden before the Second World War,’ in van der Linden and Thorpe, Revolutionary Syndicalism, 81–99; P. Cole, D. Struthers and K. Zimmer (eds), Wobblies of the World: A Global History of the IWW (London 2017).

[36] J. Cabaud, Simone Weil: A Fellowship in Love (London 1964), 139; Nevin, Simone Weil, 104.

[37] L. M. Lines, Milicianas: Women in Combat in the Spanish Civil War (Lanham, MD 2012), 43. See also M. Nash, ‘“Milicianas” and Homefront Heroines: Images of Women in Revolutionary Spain (1936–1939),’ History of European Ideas, 11 (1990), 235–44; A. Martínez Rus, Milicianas. Mujeres republicanas combatientes (Madrid 2018).

[38] Weil, Le journal d’Espagne de Simone Weil, 18 August 1936; R. Lugshitz, Spanienkämpferinnen: Ausländische Frauen im Spanischen Bürgerkrieg, 1936–1939 (Vienna 2012), 40–1; Lines, Milicianas, 81, 137; P. Sharkey, ‘Anarchist Lives: Georgette Kokoczinski (la mimosa),’ Bulletin of the Kate Sharpley Library, 73 (February 2013), 6; The Giménologues, The Sons of Night, 85–6, 94, 97, 239–41, 304–11.

[39] J. Matthews, Reluctant Warriors: Republican Popular Army and Nationalist Army Conscripts in the Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939 (Oxford 2012), 94.

[40] Richardson, Comintern Army, 48–9; Marzani, The Education of a Reluctant Radical, 16; Berry, ‘French Anarchists in Spain,’ 432. See Paz, Durruti in the Spanish Revolution, first part. The closing of the French frontier in February 1937 also undoubtedly played a role.

[41] R. D. Richardson, ‘Foreign Fighters in Spanish Militias: The Spanish Civil War 1936–1939,’ Military Affairs, 40, 1 (February 1976), 10; A. Prudhommeaux (Barcelona) to G. Aldred (Glasgow), 14 September 1936 (Mitchell Library, Glasgow, Guy Aldred Collection, 107); P. Avrich, Anarchist Voices: An Oral History of Anarchism in America (Oakland, CA 2005), 458; Nelles, Widerstand und internationale Solidarität, 197.

[42] D. Kowalsky, ‘The Soviet Union and the International Brigades, 1936–1939,’ Journal of Slavic Military Studies, 19, 4 (December 2006), 687–8; D. Malet, ‘Workers of the World, Unite! Communist Foreign Fighters, 1917–91,’ European Review of History, 27, 1–2 (March 2020), 38–9.

[43] Lätt, Som Milisman och Kollektivbonde i Spanien, 8.

[44] Graf and Nelles, ‘Widerstand und Exil,’ 122; Nelles, Widerstand und internationale Solidarität, 158, 196.

[45] E. H. Carr, The Comintern and the Spanish Civil War (London 1984), 33; V. Richards, Lessons of the Spanish Revolution (London 1972), 112. A detailed analysis of the tension between defenders and opponents of this process can be found in J. Antoni Pozo, Poder legal y poder real en la Cataluña revolucionaria de 1936 (Seville 2012). For a critique of the ‘war versus revolution’ paradigm, see Preston, The Spanish Civil War, 237–9.

[46] The Giménologues, The Sons of Night, 79, 146–7, 355–6; P. von zur Mühlen, Spanien war ihre Hoffnung: Die deutsche Linke im spanischen Bürgerkrieg, 1936 bis 1939 (Bonn 1983), excerpts available at: https://www.anarchismus.at/texte-zur-spanischen-revolution-1936/spanienkaempfer-innen/7722-patrik-von-zur-muehlen-deutsche-anarchosyndikalisten-in-spanien (accessed 24 January 2020); Gmür, Spanish Diary, 26 December 1936.

[47] Gmür, Spanish Diary, 18 January 1937.

[48] Von zur Mühlen, Spanien war ihre Hoffnung; Thalmann, Combats pour la liberté, 141–3.

[49] Matthews, Reluctant Warriors, 21–2.

[50] N. Arielli and D. Rodogno, ‘Transnational Encounters: Hosting and Remembering Twentieth-Century Foreign War Volunteers—Introduction,’ Journal of Modern European History, 14, 3 (August 2016), 319. See also S. O’Connor and G. Piketty, ‘Introduction—Foreign Fighters and Multinational Armies: From Civil Conflicts to Coalition Wars, 1848–2015,’ European Review of History, 27, 1–2 (March 2020), 1–11.

[51] Anonymous, ‘Federica Montseny habla en Madrid ante el micrófono de Unión Radio,’ Solidaridad Obrera (2 September 1936). See also X. M. Núñez and J. M. Faraldo, ‘The First Great Patriotic War: Spanish Communists and Nationalism, 1936–1939,’ Nationalities Papers, 37, 4 (July 2009), 401–24; M. Baxmeyer, ‘“Mother Spain, We Love You!” Nationalism and Racism in Anarchist Literature during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939),’ in Bantman and Altena, Reassessing the Transnational Turn, 193–209.

[52] Alexander, The Anarchists in the Spanish Civil War, Vol. 2, 255; M. Haapamaki, ‘Writers in Arms and the Just War: The Spanish Civil War, Literary Activism, and Leftist Masculinity,’ Left History, 10, 2 (Fall 2005), 39–40.

[53] Weil, Le Journal d’Espagne de Simone Weil, 18 August 1936.

[54] Michael Alpert claims that the consequences of the ‘militia epoch’ were ‘indiscipline,’ ‘disorganization’ and ‘political infighting,’ while R. Dan Richardson argues that whilst the militias were useful when defending stationary positions in a village or town, out on the field, most battles consisted of ‘sporadic tenacious defense by the militia, an outflanking movement by the Nationalists, and panic and retreat by the militia’: Alpert, ‘The Popular Army of the Spanish Republic,’ 97; Richardson, ‘Foreign fighters in Spanish militias,’ 8. See also Matthews, Reluctant Warriors, 19–23, although he notes that the militias fared better when offered natural cover.

[55] Á. Viñas, El escudo de la República. El oro de España, la apuesta soviética y los hechos de mayo de 1937 (Barcelona 2010), 174.

[56] M. Alpert, The Republican Army in the Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939 (Cambridge 2013), 66–8; A. Paz, The Story of the Iron Column: Militant Anarchism in the Spanish Civil War (Oakland, CA 2011), 177.

[57] CNT-FAI, Buenaventura Durruti (Barcelona 1936), 25–6. Einstein must surely be the only person to have given eulogies to both Durruti and Rosa Luxemburg (at her funeral): Zeidler, Form as Revolt, 3.

[58] Casanova, Anarchism, the Republic and Civil War in Spain, 107. See also V. Alba, Los colectivizadores (Barcelona 2001); W. L. Bernecker, Colectividades y Revolución Social: El anarquismo en la guerra civil española, 1936–1939 (Barcelona 1982); F. Borkenau, The Spanish Cockpit: An Eye-Witness Account of the Political and Economic Conflicts of the Spanish Civil War (Ann Arbor, MI 1963), 98, 103; S. Dolgoff (ed.), The Anarchist Collectives: Workers’ Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939 (Montréal 1974); S. Juliá Díaz, ‘Víctimas del terror y de la represión,’ in E. Fuentes Quintana and F. Comín (eds), Economía y economistas españoles durante la Guerra Civil, Vol. 2 (Madrid 2008), 385–410; F. Mintz, Anarchism and Workers’ Self-Management in Revolutionary Spain (Oakland, CA 2013); P. Preston, The Spanish Holocaust: Inquisition and Extermination in Twentieth-Century Spain (London 2012), 242–50; M. Seidman, ‘Agrarian Collectives during the Spanish Revolution and Civil War,’ European History Quarterly, 30, 2 (April 2000), 209–35.

[59] CNT-FAI, Buenaventura Durruti, 25–6.

[60] Paz, Durruti in the Spanish Revolution, 470.

[61] Weil, Le Journal d’Espagne de Simone Weil, 16 August 1936.

[62] The Giménologues, The Sons of Night, 52–4.

[63] Gmür, Spanish Diary, 31 December 1936.