Nestor Makhno

Under the Blows of the Counterrevolution: April-June 1918

Title page of original (1936) edition

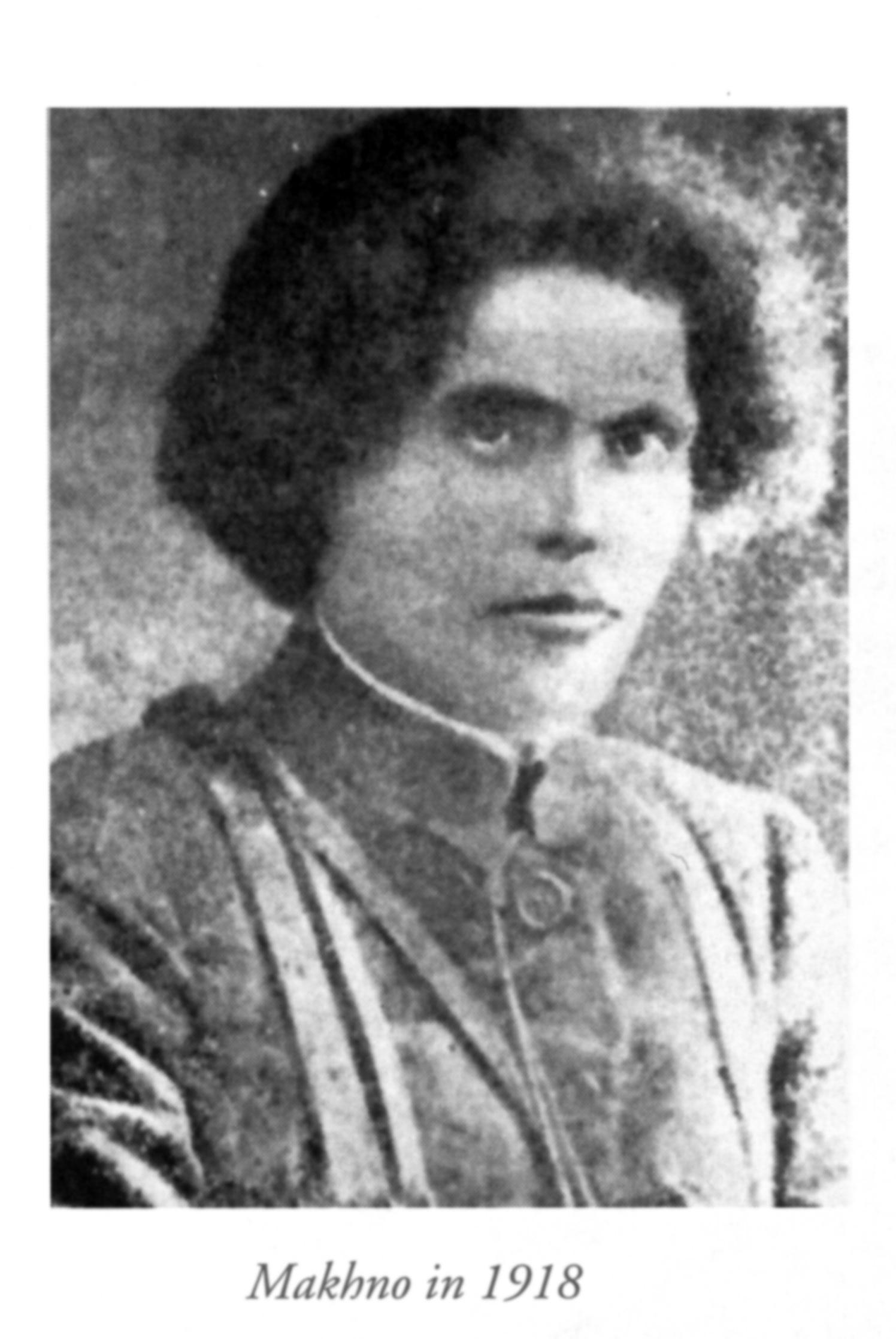

Portrait from original (1936) edition

Chapter 2: The Disarming of Maria Nikiforova’s Detachment.

Chapter 4: The Flight of the Agricultural Communes and My Search for Them.

Chapter 6: En Route With the Echelon of the Red Artillery Base.

Chapter 8: Meeting With People From “Revolutionary” Circles.

Chapter 9: Meeting With the Communards, Moving Them to Olshansk Khutor, and Saying Farewell

Chapter 10: Saratov: Local and Refugee Anarchists and My Avoidance of Certain Comrades.

Chapter 12: En Route From Astrakhan to Moscow.

Chapter 13: Moscow: My Meetings With Anarchists, Left Srs and Bolsheviks.

Chapter 14: Conference of Anarchists in Moscow at the Hotel Florencia.

Chapter 15: The All-russian Congress of Textile Trade Unions

Chapter 16: In the Peasant Section of the Vtsik of Soviets.

Chapter 17: The Kremlin, Sverdlov, and My Conversation With Him.

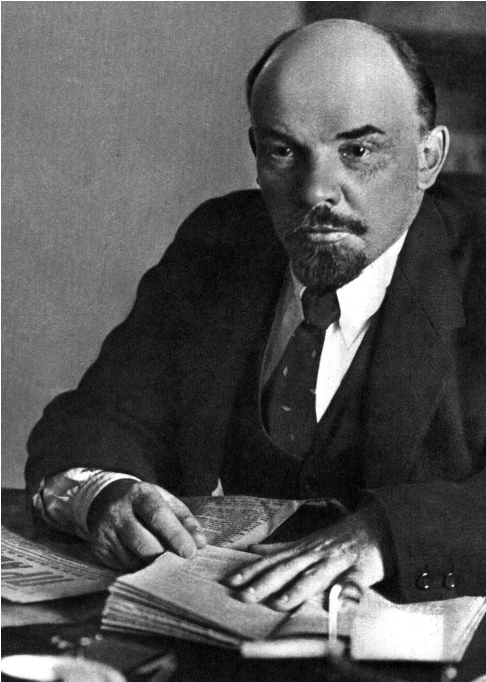

Chapter 18: My Meeting and Conversation With Lenin

Chapter 19: Meetings With New People and Gloomy Impressions. Preparations to Depart for Ukraine.

Chapter 20: En Route to Ukraine.

Notes to Chapters 8, 9, 12, and Some Others

From the Memoirs of Aleksei Chubenko

Translator’s Introduction

The Ukrainian Anarchist Nestor Makhno (1888–1934) intended to publish his memoirs of the Russian Revolution and Civil War in ten volumes but poverty and illness restricted him to finishing just three manuscripts of which only one was published during his lifetime. Under the Blows of the Counterrevolution, the second volume of Makhno’s memoirs, was issued posthumously in 1936. The book covers a scant ten weeks in the spring and early summer of 1918. It has interested historians mainly because of Makhno’s interviews with Lenin and Sverdlov (Chapters 17–18) but also includes eye-witness information about important but little known events of the Civil War and sheds light on the formation of Makhno’s views about the Russian Revolution which were to guide his actions over the next three years.

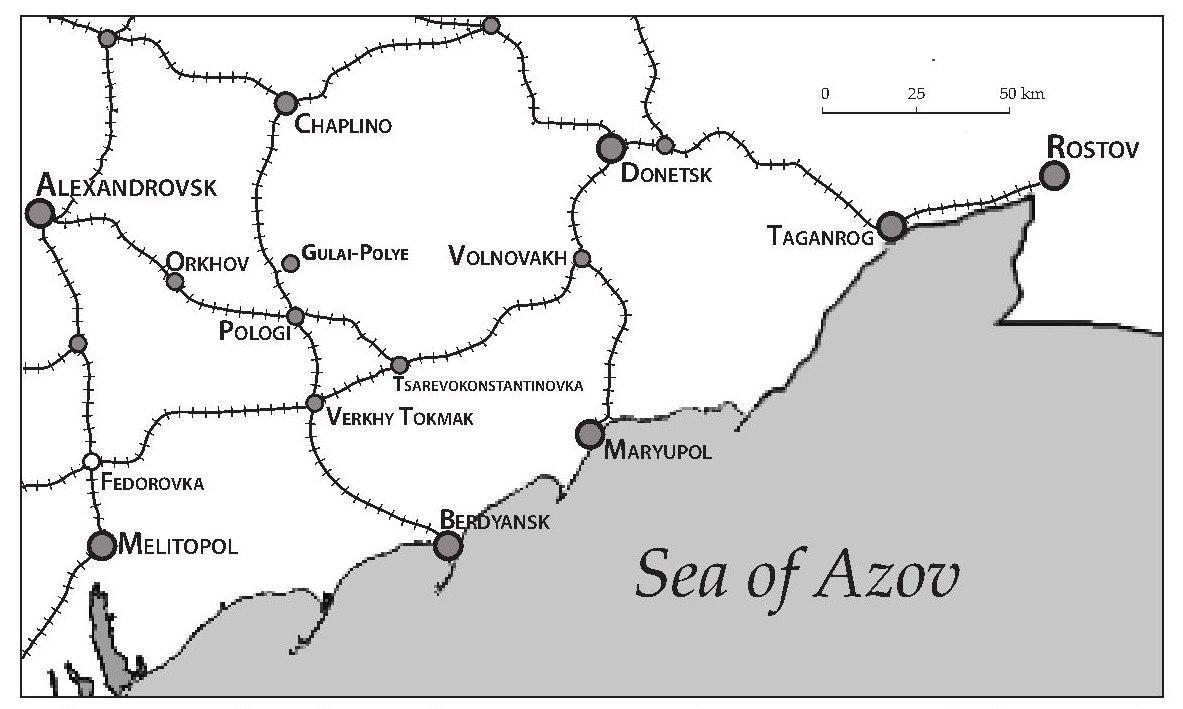

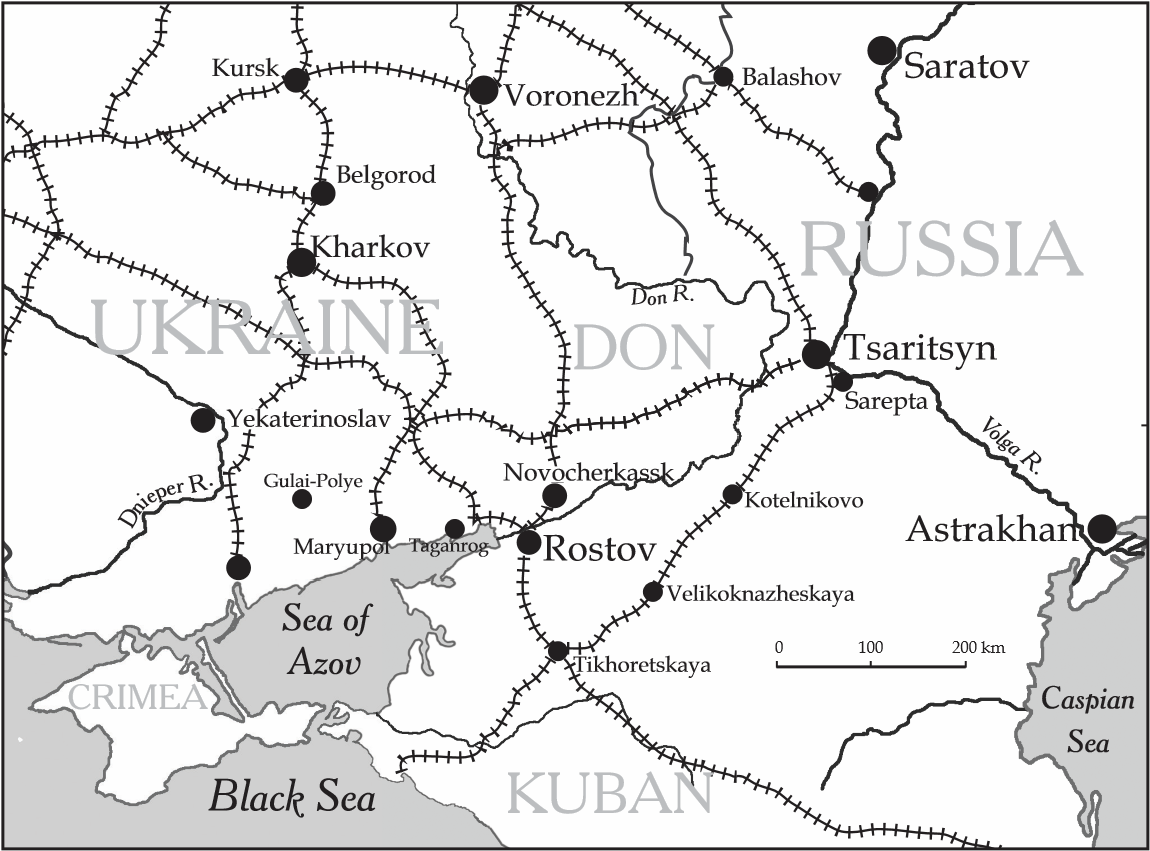

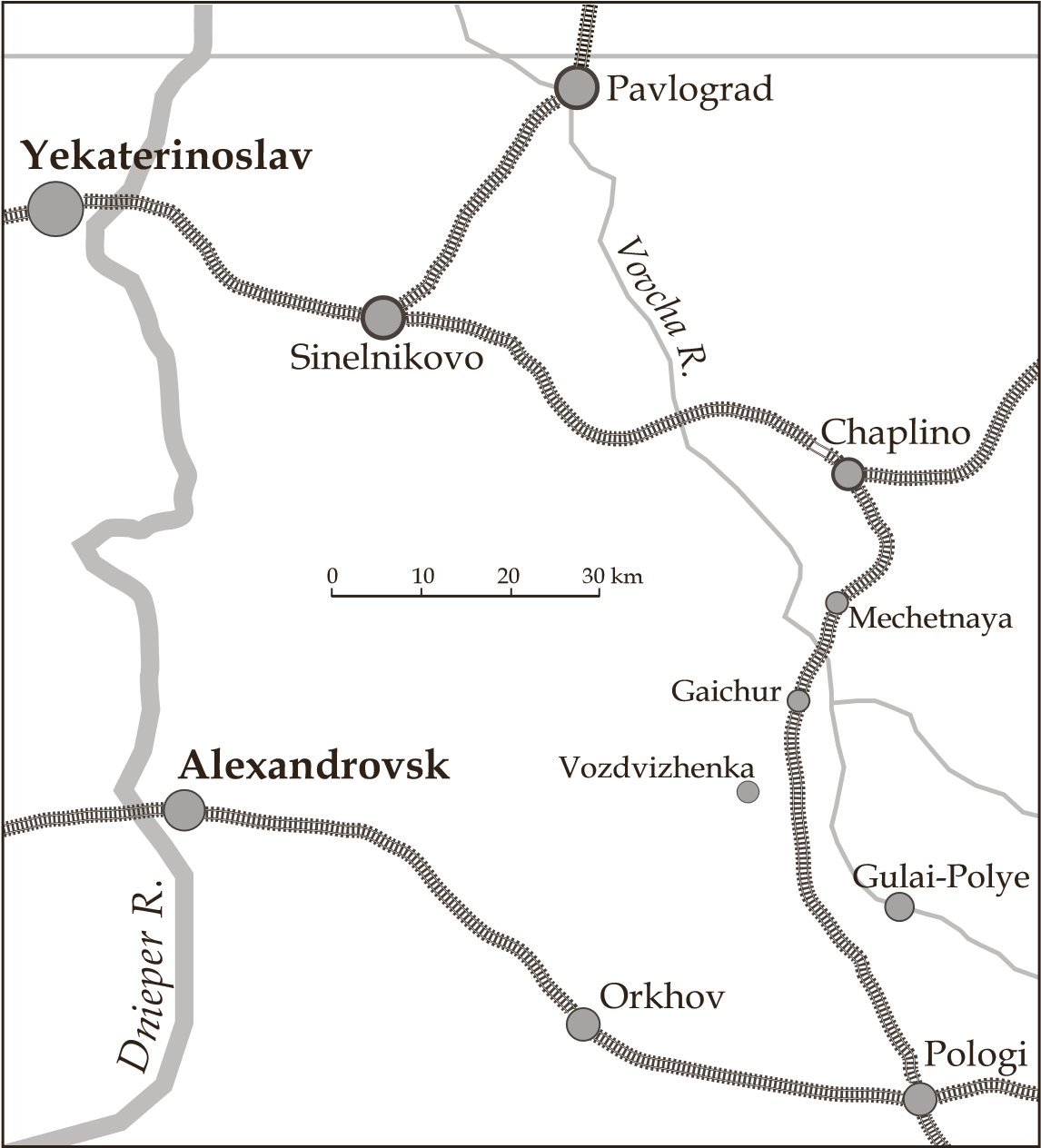

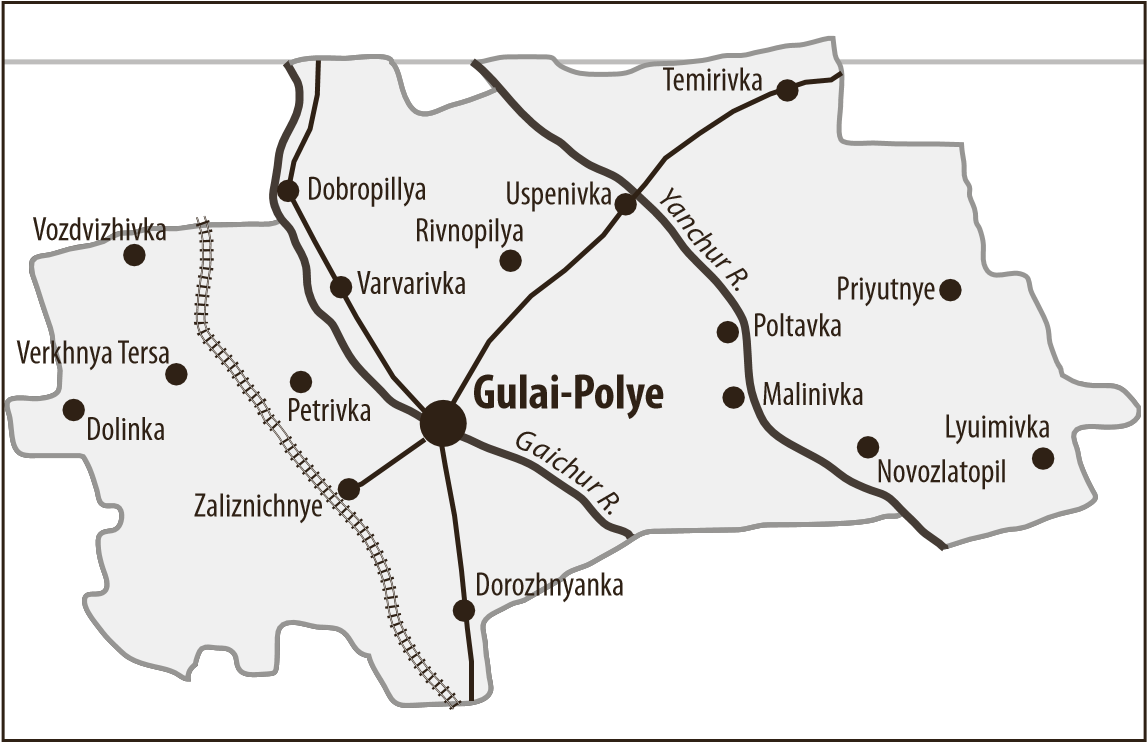

Volume II describes Makhno’s travels through a Russia which was in the opening stages of the protracted Civil War which followed the Bolshevik seizure of power in October 1917. In Volume I Makhno described the revolutionary process in his home village and raion (county) of Gulai-Polye.[1] This process came to an end in April 1918 when a fifth column in the village staged a nationalist coup shortly before an invading German force occupied the region. Makhno and his comrades were forced to join the stream of refugees moving east in advance of the relentless counterrevolutionary wave.

The German invasion was a consequence of the Treaty of BrestLitovsk, which casts a shadow over the events of Volume II. There were actually two Brest-Litovsk treaties, which officially brought an end to World War I on the Eastern Front. The first, signed between the Ukrainian nationalist Central Rada and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Turkey) on February 9 1918, allowed German and Austro-Hungarian troops to occupy Ukraine and requisition its food supplies and natural resources. (Makhno never forgave the nationalists for this alliance.) The second, signed between the Russian Soviet Republic and the Central Powers on March 3 1918, ended hostilities between Russia and Germany and obligated the revolutionary government in Moscow to withdraw its troops from Ukraine where they had been carrying on a successful war against the Central Rada.

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk provided a “breathing space” (Lenin’s term)[2] for the Bolsheviks to consolidate their power. This involved, among other things, settling accounts with their erstwhile allies, the Anarchists. On the night of April 12–13 1918, the headquarters of the Anarchist Black Guard on Malaya Dmitrovka Street in Moscow was attacked by the Soviet secret police (the Cheka) and soldiers. This was a pitched battle in which both sides used artillery. Fighting also took place at some of the other two dozen buildings in the city occupied by Anarchist organizations. The night ended with complete victory for the government forces: about 40 Anarchists were killed or wounded and about a dozen Chekists and soldiers. Around 500 Anarchists were arrested, although most were soon released.[3]

Similar actions took place in other centres controlled by the Bolsheviks. In fact the Bolsheviks allocated significant forces to suppressing the Anarchists, diverting them from the struggle with their right-wing opponents. Soviet propaganda depicted this campaign as a police action against banditry and other criminal activities rather than elimination of a rival political group. In fact the head of the Cheka, Dzerzhinsky, emphasized, “It is not our intention or desire to carry on a struggle with ideological Anarchists.”[4] Nevertheless the largest Anarchist newspapers were shut down and Anarchist activity was limited by the authorities to low-key educational work. There was never to be a public “Trial of the Anarchists” in the Soviet Union as there were to be trials of other major political tendencies. Indeed, some form of legal Anarchist activity was to continue as late as 1937.

With the Anarchists subdued, the Bolsheviks were now free to move against the Left SRs, their other main threat from the revolutionary left. Makhno ran into many Left SRs on his journey and on the whole portrays them in a sympathetic light. They were close to the peasantry and seemed to be adopting positions similar to those of the Anarchists. But, as Makhno hints, their party was soon to succumb to the Bolshevik hammer, the main blow coming in the first week of July 1918.

The revolutionary government in Moscow had set up a Ukrainian People’s Republic which in principle was not subject to the treaty signed by the Bolsheviks (their coalition partners, the Left SRs, generally refused to recognize the treaty). The puppet government of this Soviet Republic tried to offer resistance to the invading German-Austro-Hungarian force and its nationalist allies (variously estimated at between 200,000 and 600,000 troops) but the forces at its disposal (15,000 to 30,000 in detachments of varying quality) were pitifully inadequate. Armaments were not a problem for the revolutionaries as Soviet Russia optimistically shipped 70,000 rifles and 1,800 machine guns to Ukraine. Armoured cars and trains were also available. The Gulai-Polye Anarchists were presented with 3,000 rifles, six cannons, and 11 railway wagons of ammunition although they only had about 500 partisans in the field.[5] It is perhaps a measure of the weakness of the Soviet rulers of Ukraine that they had to depend on Anarchists to do some of the heaviest fighting. The revolutionary forces found themselves engaged in a proxy war being controlled by the cynical Bolshevik leaders in the Kremlin who realized there was no hope of saving Ukraine but wanted to slow down the invaders so valuable resources could be evacuated to Russia. This mini-war ended in early May 1918 after a mere 70 days of hostilities with the complete occupation of Ukraine by Germany and Austria-Hungary.

As he set out on his journey as a political refugee, Makhno was still a person of only local significance and not the national or even world-historical figure he later became. [If the latter description seems excessive, consider that he succeeded in doing what had never when done before – to construct an entirely new social system based on Anarcho-communist principles in a region with a population of millions – at least for a time.]

Travelling east to the Volga basin, Makhno found himself in the midst of a “civil war within the civil war,” which included such dramatic events as the trial of Nikiforova, the sack of Rostov, the disarming of revolutionary detachments, Petrenko’s “siege” of Tsaritsyn, and street battles in Saratov. These episodes disappeared almost entirely from the Soviet historiography of the Civil War but students of Soviet history will recognize them as precursors of similar events in the Spanish Civil War and World War II.

Makhno was continually running into fellow victims of the tsarist prison system, some of whom he had known in Butyrki Prison in Moscow. He had natural allies in such people even though they might belong to rival political groups. (His friend Petr Arshinov once shared a cell with the future Bolshevik satrap Sergo Ordzhonikidze, a connection which he was able to exploit for a valuable favour.) Makhno also had papers proving he had been the chair of a revolutionary organ in his home town, documents which allowed him to be treated as one of the revolutionary elite in Russia. He had access to free meals, rooms, train tickets, and government jobs. Conveniently, his papers did not mention he was an Anarchist.

When Makhno finally reached Moscow, he encountered some of the most brilliant personalities in the history of Anarchism, including Aleksandr Borovoi, Petr Arshinov, Lev Chorny, Yuda Grossman-Roshchin, Aleksandr Shapiro, Wroclaw Machajski, and the founder of Anarcho-communism himself, Petr Kropotkin. Makhno judged the Anarchists he met by their willingness to go to the countryside and take up organizing work among the peasants, and found most of them wanting. In fact he became so disgusted with what he perceived to be the laziness of the urban Anarchists that one might speculate that he may have abandoned Anarchism by the time he returned to Ukraine in July 1918. But anyone who has spent time in the Anarchist movement will understand his state of mind – frustration with Anarchists but not with Anarchism.

Makhno managed to set up meetings with Sverdlov and Lenin by accident while tramping around the Kremlin trying to arrange living quarters. In his quest to avoid spending the night on a park bench he ended up dealing with the heads of state! His detailed account of his interviews with the Bolshevik leaders has been questioned by some historians because it takes the form of direct quotations although no transcript or indeed any kind of official record of the meetings exists.[6] Nevertheless Makhno’s account is convincing, especially since he came away with a grudging respect for Lenin. In fact the endless biographies and chronologies of Lenin’s life do not mention interviews with dozens of persons regarded as politically unreliable. It is noteworthy there is a record of his meeting with a dedicated Bolshevik working in Ukraine, E. B. Bosh, on June 26 1918 during which Lenin asked pointed questions about the attitude of the peasantry towards Soviet power.[7]

Lenin had another visitor around that time, the Ukrainian Bolshevik partisan leader Aleksandr Parkhomenko (1886–1921) who was later transformed into a Soviet hero of the Civil War, sort of a Communist version of Nestor Makhno himself. Parkhomenko had commanded a detachment which fought against the GermanAustro-Hungarian invasion of Ukraine and then, like Makhno, he fell back to Tsaritsyn where he was put to work in the Cheka. After Stalin arrived in Tsaritsyn in June 1918, he recognized Parkhomenko’s talent and dispatched him to the Kremlin to have an inspirational talk with Lenin, strikingly similar to Makhno’s interview. Parkhomenko went on to hold military commands in the Red Army in Ukraine, winning two prestigious “Order of the Red Banner” awards. According to the Soviet legend, he was killed in battle fighting heroically against the Makhnovists in January 1921. Parkhomenko’s life was the subject of several novels (including a reader for junior high school students) and a major motion picture (“Aleksandr Parkhomenko”) released in 1942. Many towns, streets, and factories in the Soviet Union were named after him and his face appeared on a postage stamp as recently as 1986.

Parkhomenko’s real story, retrieved from the Soviet archives, is somewhat different. Commanding a detachment noted for its lack of discipline and antisemitism, he and his entire staff were captured by the Makhnovists without putting up any resistance and he was executed as a war criminal for burning villages and killing defenseless civilians. The Makhnovists would also have remembered his murder of the Anarchist Maksuta in May 1919 during negotiations, in an incident strikingly similar to the killing of Petrenko described in Chapters 8–9 of the present volume. In pleading for his life, Parkhomenko invoked the name of his younger brother, an Anarchist commander in the Makhnovist Insurgent Army. This younger brother, unmentioned in the Soviet legend, was killed in battle two months later fighting the Red Army. There was also an older brother, a Bolshevik official who arranged exchanges of munitions for grain with the Makhnovists and had a high opinion of their efficiency. The full story of the Parkhomenkos, a poor peasant family torn apart by the Civil War, and their relations with Nestor Makhno, has yet to be told.[8]

Makhno’s discussion with Lenin allows an understanding of his differences with the Bolsheviks but also explains why he was repeatedly able to form alliances with them – alliances which were inherently unstable. Their enemies were the same (capitalists, landowners) and they pursued the same goals (soviets, communism) but the latter terms were understood differently by Anarchists and Bolsheviks. The Bolshevik slogan “all power to the soviets” was interpreted by the peasantry in a literal sense, Makhno told Lenin, and therein lay the tragedy of the Revolution in Ukraine.

But what are we to make of Makhno’s meeting with Kropotkin? The Anarchist sage had long been his spiritual mentor but the substance of their interview is almost entirely lacking in Makhno’s account (Chapter 14). The authors of various literary biographies of Makhno have been compelled to embellish this encounter with details for which no documentary evidence exists.[9] Within the future Makhnovist movement this meeting acquired a cultural significance as if Kropotkin had bestowed a blessing on Makhno. It must be noted that Kropotkin had virtually retired from active political life in 1918, partly due to infirmity and partly because he was no longer in tune with the movement he had done so much to inspire. Although invited to the many Anarchist conferences which took place in those days, he never attended any. Nevertheless Volin reported Kropotkin “took a keen interest in the Makhnovist movement and said that if he were young he would go work in the Makhnovist region.”[10] And according to Arshinov, in June 1919 Kropotkin said, “Tell Comrade Makhno from me to take care of himself, for there are not many people like him in Russia.”[11] This endorsement must also be regarded as apocryphal, since Arshinov was busy in Ukraine at the time.

At the risk of being intrusive, the Makhno’s text has been supplemented with numerous footnotes. These attempt to explain the complex events happening around him (with “fronts against the Revolution” popping up all over the place) and provide information about the identifiable people he met. In preparing his memoirs, Makhno had very limited means of verifying factual information and for the most part had to rely on his memory, which his wife Galina Kuzmenko described as “excellent.”[12] Since Makhno never finished his memoirs, he was unable to complete a number of sub-plots involving people such as Nikiforova, Polonsky, Voroshilov, and Zatonsky who kept re-appearing in his life (often with increasingly dire consequences). The footnotes try to fill this void by describing the outcome of his relations with these persons.

This edition of Under the Blows of the Counterrevolution includes the preface and endnotes by the editor of the original Russian edition, Vsevolod Volin (1882–1945). Volin was not the ideal collaborator for Makhno for the two men did not get along. Their differences were both personal and ideological. Makhno grew up in a remote village under conditions of extreme poverty and was largely self-educated. Volin was raised in a middle-class, urban household where both parents were physicians and he and his brother, a future literary critic, were tutored in French and German. Volin lived abroad for many years before the 1917 revolution while Makhno was languishing in tsarist prisons. Volin had occupied an important position in the Makhnovist movement for several months in 1919 but that experience later became a source of friction between the two men as Makhno was convinced Volin had betrayed the cause after being captured by the Bolsheviks in December 1919. In exile both men ended up in Paris where they developed different theoretical positions: Volin expounded “United Anarchism,” a synthesis of the three main currents of Anarchism (Anarcho-communism, Anarcho-syndicalism, and Anarcho-individualism); while the Anarcho-communists Makhno and Arshinov set forth the so-called “Platform,” a program which posited a degree of organization unpalatable to many Anarchists.

A war of words erupted between Makhno and Volin in the Anarchist press. Volin described Makhno as “paranoid” and “malicious”[13] while Makhno called Volin a “scoundrel” and “liar.”[14] Makhno was able to mount an able defense to Volin’s attacks during his lifetime, but after his death Volin had the field to himself and did much damage to Makhno’s reputation with accusations of drunkenness and debauchery.[15] Volin’s assertion in his preface that his relations with Makhno had “improved somewhat” before the latter’s death must be taken with a grain of salt since in Makhno’s last published article, an obituary for Nicolai Rogdaev, he went out of his way to express his contempt for Volin.[16] In fairness to Volin it must be said there is no evidence he tampered with Makhno’s text in any way and his reservations about Makhno’s views are confined to his preface and endnotes. A substantial extract from Volume II was published by Makhno in the emigré journal Rassvyet [Dawn] in 1932 and a comparison with Volin’s 1936 edition shows negligible differences.[17]

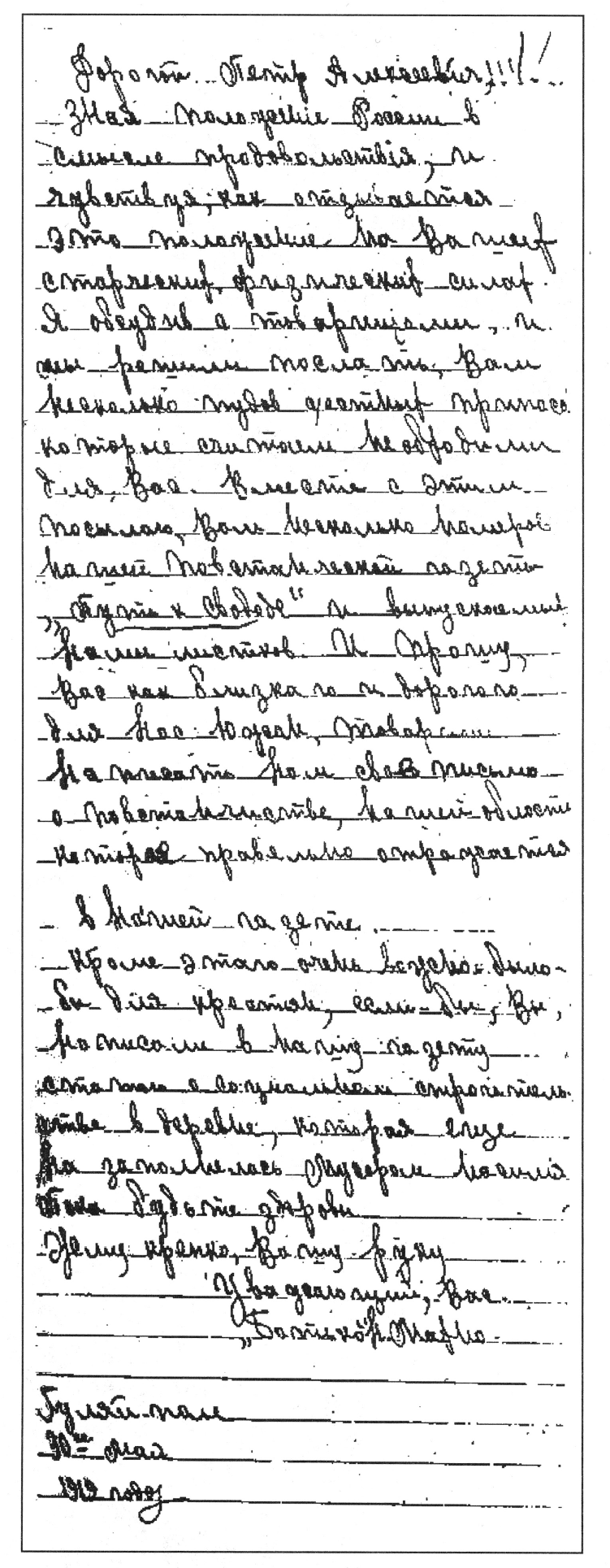

Makhno wrote his memoirs in the faint hope they would reach interested readers in Ukraine and Russia. In fact this only became possible in the 1990’s. In the Soviet Union his writings were not available even to professional historians. Of the other books published in the West about his movement, Petr Arshinov’s История махновского движения [History of the Makhnovist Movement] and Paul Avrich’s The Russian Anarchists were available in one copy each in special collections (restricted access) in Moscow and Leningrad respectively, while Alexandre Skirda’s Makhno: le cosaque de l’Anarchie was totally unavailable. In his preface to Volume 1, Makhno expressed the wish that his memoirs could be available in Ukrainian, but although they have been published in Kiev more than once since the demise of the Soviet Union, this has not happened.

I would like to thank Laure Akai, Nick Driedger, Will Firth, Nestor McNab, and Sean Boomer for encouragement in publishing this volume, with a special thanks to Gail Silvius for editorial assistance. I’m also indebted to the website www.makhno.ru and its many contributors who are dedicated to finding and preserving accurate information about the Makhnovshchina.

Malcolm Archibald

July, 2009

Edmonton, Alberta

Preface

I very much regret that a personal conflict with Nestor Makhno prevented me from editing the first volume of his memoirs, which was published still during the author’s lifetime. The absence of an experienced editor had a detrimental effect on this first book. And since its content was not of exceptional interest, it is not surprising that this first part of Makhno’s notes gave rise to a certain disappointment.

Not long before the death of N. Makhno, my personal relations with him improved somewhat. I considered proposing to him that I edit, with his participation, the rest of his memoirs. His death prevented me from following through on this intention.

After Makhno’s death comrades who were interested in publishing the continuation of his notes entrusted the job of editing them to me. I was also to provide an explanatory preface and some notes to the text, where necessary. (These notes the reader will find at the end of the book.)

I consider it necessary first of all to mention that my editorial task boiled down exclusively to imparting to Makhno’s notes a minimally literary form. I not only did not make any changes in the text which could remotely effect the meaning; but more than that, as much as this was possible I preserved untouched the style of the original – distinctive and in places quite colourful. The corrections introduced into the text had the exclusive function of making the book readable. For the uninitiated reader I must add that N. Makhno possessed only a grade school education, and had not mastered literary writing in the slightest degree (which, however, as already noted, did not prevent him from having his own characteristic “style”). In places, especially where he embarks on extensive theoretical discussions, his manuscript becomes syntactically illiterate. He fares much better in his vivid descriptions of events. The pages devoted to narrating such events could be left virtually untouched.

With respect to its actual content, Book II of the memoirs is more interesting than the first. Makhno’s observations during his travels through the whole of Russia in the summer of 1918, his meetings and conversations, his reflections, dismay, disillusionment and, finally, his decision to devote himself whole-heartedly to organizing peasant revolt in Ukraine for the struggle of a new, stateless social system – all this is extremely significant, indeed brilliant. Makhno’s stay in Moscow and his conversations with Lenin and Kropotkin are described in a lively fashion. The reader distinctly sees the gradual development of Makhno’s basic ideas. As we approach the end of the book, we have a excellent understanding of the author’s psychology. Before us stands the clear image of a person devoted to his personal ideal. The end of the book is suffused with great emotional tension.

The present, second volume of Makhno’s memoirs takes us up to July 1918. The author stops at the threshold, so to speak, of the huge peasant insurrection of which he became the chief motivator and organizer after July. The next, third volume (The Ukrainian Revolution), which takes us to the end of 1918, is still more interesting and important. He gives a complete picture of the first, preparatory stages of the Makhnovist movement (Makhnovshchina). It will be published immediately after the 2nd volume.

Unfortunately, Makhno’s notes for the third volume break off abruptly. Illness and death prevented him from carrying through the work to the end. The loss was irreparable since there was no one better to tell the story of the movement.

The three books written by him provide, however, a sufficient understanding of, first, the personal role and psychology of Makhno and, second, the least known period of the Makhnovshchina: about its first steps and first successes. Beginning with 1919 the history of the movement is better known. First and foremost, there is the book by P. Arshinov, The History of the Makhnovist Movement, published in 1923 and continuing the story, beginning with 1919. Then there are still living some participants of the events of 1919–1921 who are able to describe them in detail. Finally, there exist, undoubtedly, numerous documents, although at the present time they are dispersed in private hands.

I do not find it necessary, nor possible, in a brief preface to give a critical evaluation of the Makhnovshchina or the views of N. Makhno. The reader will find some remarks about the opinions expressed by Makhno in the present work set forth in notes to the corresponding chapters at the end of the book. I propose in the near future to publish a small work giving a critical sketch of the movement and drawing lessons from it which will be of interest both for Anarchists and for anyone interested in grassroots movements.

V. M. Volin

July 1936

Paris

Chapter I: The Retreat.

In April 1918 I was summoned to Yegorov’s headquarters[18] – the headquarters of the Red Guard forces. But the staff was no longer in the place I had been told to go: it had fallen back under the pressure of the German-Austrian forces and where it was now set up was still unknown. During the time I was travelling along the railroads, a great upheaval took place in Gulai-Polye. It was occupied by enemies of the Revolution – German and AustroHungarian expeditionary units and their fellow travelers, the detachments of the Ukrainian Central Rada.

The Red Army and Red Guard detachments fled. After them followed other revolutionary formations. Inhabitants also fled from their homes to the gleeful satisfaction of the enemy.

The shocking news about the occupation of Gulai-Polye reached me at the station of Tsarevokonstantinovka. And I saw the revolutionary forces running away myself. It was painful to watch this flight. I felt a great heaviness on my heart which deprived me of the possibility of clearly imagining what must have transpired in Gulai-Polye during my two-day absence. I was so shaken and paralyzed by everything that had happened I was in no condition to cope with this overwhelming burden with my own physical powers. Right there in the station I collapsed, laid my head on the knees of one of the Red Guards, and mindlessly cried out:

“No, no, I’ll never forget the treacherous role of the nationalists! It’s shameful for a revolutionary Anarchist to nurture thoughts of revenge, but I’m obsessed with such thoughts and they will influence my subsequent revolutionary activity…”

The Red Army soldiers told me about this later. They also said I began to weep and fell asleep in a railway carriage on the knees of the same Red Guard. But I have no memory of this.[19]

It seems to me I didn’t sleep but only felt extreme anxiety. This feeling was painful but I could still walk and speak. I recall that I couldn’t figure out where I was… Only when I exited from the carriage did I realize I was still at Tsarevokonstantinovka station. I excused myself to the Red Guards surrounding me and headed for the station building.

On the way I ran into several comrades and my brother Savva Makhno,[20] who had escaped from Gulai-Polye. This meeting made me ecstatic. I peppered them with questions about the circumstances under which Gulai-Polye was surrendered, and about what kind of losses had been suffered by the detachment of Anarchists and the other revolutionary organizations.

But the comrades, noticing that I was not in a healthy state, refrained from answering in detail, limiting themselves to brief reports, such as: “Gulai-Polye was surrendered, but not everyone was killed,” etc.

This infuriated me, but there was nothing to be done. I couldn’t force them to tell me the details, since I knew all the troop trains were taking off and we needed to find a place in one of them. I mentioned this to my brother, and he found us a place.

In another five or ten minutes we were seated in one of the Red Guard carriages and discussed in depth the state of the Revolution in Ukraine. Of course this discussion had to include the fate of Gulai-Polye and its vast raion where we had grown up, where we had developed our ideas, and where we had undertaken the colossal task of putting them into practice through revolutionary action.

Yes, we talked about Gulai-Polye. We thought about its occupation by the enemy and the errors we made in organizing free revolutionary battalions to oppose the Counterrevolution which was now borne on the bayonets of the formidable GermanAustrian Army and the militarily weak but vicious detachments of their bootlickers – the Ukrainian Central Rada.

Our errors resulted from the fact that when we formed the free battalions[21] we signed up anyone who wished to join without doing any background checks. This led to the presence in the ranks of the free battalions of supporters of the Ukrainian Central Rada and its criminal, counterrevolutionary alliance with the German and Austrian governments. I have to admit that personally I didn’t find this mistake terribly serious. A greater evil in my mind was the error committed by the Revkom on the one hand and by our Group on the other – the error which permitted five or six scoundrels to act in favour of the German-Austrian-Hungarian command and the Ukrainian Central Rada in the matter of surrendering GulaiPolye without a fight and then carrying out reprisals against many of the toilers. This error was the hasty and strategically unwise dispatch of the Anarcho-communist detachment from Gulai-Polye to the Front. Although this move could be justified morally and tactically in relation to the remaining detachments, the Anarchocommunist detachment should have been retained in Gulai-Polye under the direct control of the Revkom and the Secretariat of the GAK until such time as other armed revolutionary units had arrived. Only when it was time for all the armed forces to advance to the Front was it necessary to release the Anarchist detachment, placing it in the vanguard. In reality, eye-witnesses of the events transpiring in Gulai-Polye in my absence told me the arrests of the members of the Revkom, the Soviet, and the Executive of the GAK were engineered by five people, using phony documents in some cases,[22] as well as the armed strength of the Jewish regiment which was irresolute and inclined to go with the flow. If the Anarchist detachment had been present in Gulai-Polye at that time (even if I wasn’t there myself), the conspirators would never have been able to shuffle the order of garrison duty so they could make use of the Jewish regiment for their scheme. The commander of the Jewish regiment, not himself Jewish, had a tendency when under stress to side with the stronger party.[23] He, along with the conspirators themselves and his submissive regiment, carried out an attack on the Revkom and arrested its members. Then he set the regiment to hunting down individual members of the Soviet, peasant elders, and Anarcho-communist workers...

If the Anarcho-communist detachment had been in GulaiPolye instead of at the Front fighting the Expeditionary Army and the troops of the Central Rada, it would not have allowed enemy agents to organize an armed attack on the Revkom and wreck its efforts to set up a Front against the Counterrevolution. Unfortunately, a worst-case scenario occurred. I recall addressing my comrades as follows:

“In Gulai-Polye and the whole of its raion we can now expect from the peasants and workers something extremely undesirable from a revolutionary perspective – a despicable hatred for Jews in general. Both intentional and unintentional enemies of the Revolution could make use of this hatred. We have gone to great pains to convince the non-Jewish toilers that the Jewish toilers are their brothers and must be involved in the business of social reconstruction on an equal basis. But now we find ourselves facing the possibility of Jewish pogroms. We need to think about this also, and think seriously…”

“You’re right,” my friends replied, “the peasants and workers are feeling a strong hatred for the Jews right now, but it’s not our fault… The Jews in Gulai-Polye were never isolated from the social life of the non-Jewish population. And it was only the actions of the Jewish Regiment on April 15–16 that incited the non-Jewish population to hatred towards the Jews. At the time we left Gulai-Polye we didn’t notice any manifestation of antisemitic sentiment… But what can we do? We are powerless to deal with this now. Our forces have taken to the underground, in significant measure because of the actions of the Jewish Regiment…”

“Here’s the crux of the matter,” I persisted, “with the triumph of the Counterrevolution and thanks to the irresponsible actions of the Jewish youths, the spirit of antisemitism is in the air over Gulai-Polye. And it is our firm obligation not to allow this spirit to settle in Gulai-Polye. Gulai-Polye is the heart of our nascent struggle against the Counterrevolution. We must get back there, no matter what it costs us as a group of revolutionary Anarchists. Once we get back there, it will be our firm obligation to avert that evil which is finding a home in the hearts of the peasants and workers because of the actions of the Jewish Regiment… And we can avert it by explaining to the toilers in a timely fashion who the guilty party was in bringing about the arrests… If we don’t take appropriate measures to deal with this problem, then, mark my words friends, the Jewish working population will be wiped out…”

“You’re quite right,” replied my friends, “but what happened wasn’t our fault… We don’t dispute the fact we need to give this matter serious thought and make it our business to fight against all this… But it will have to wait till we get back to Gulai-Polye. In the meantime we must consider where we should set up a temporary meeting place so we can gather together all of our comrades who will be passing through the Red Front and searching for you…”

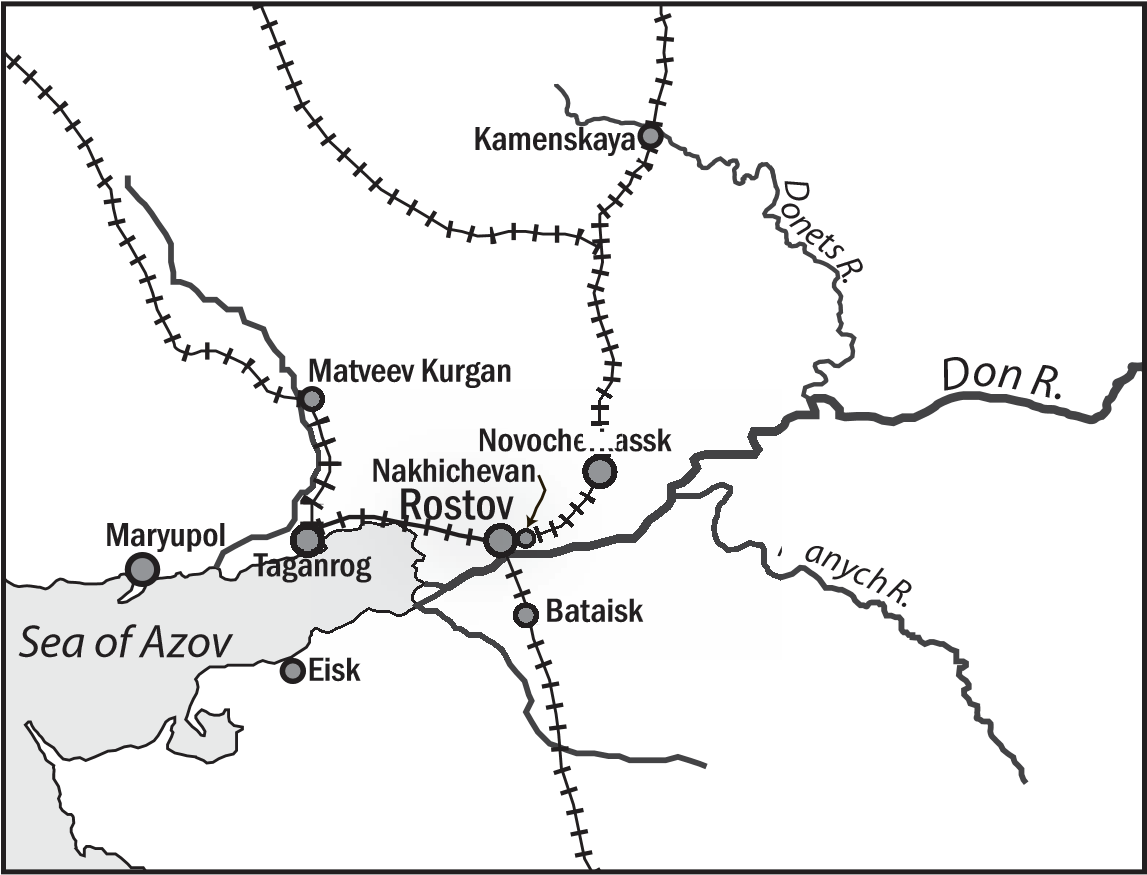

We decided to set up shop for a spell in Taganrog, the current location of the Ukrainian Bolshevik — Left SR government. The officials of this government had fled there from the various cities of southern Ukraine. Most of the Red Guard detachments were retreating there as well. In Taganrog some of these fugitive units were issued itineraries for subsequent deployment; others were subject to arrests, forcible disarmament, and court martial.

So we would spend a couple of weeks in Taganrog. During this time the rest of our comrades would show up. We would hold a conference to decide the following question: by what means and in what kind of order would we begin to return to our own raion to undertake underground work against the triumphant Counterrevolution?

In the meantime, while we were discussing this matter, the echelons of Petrenko’s detachment were ordered to depart from the railway junction of Tsarevokonstantinovka and move towards Taganrog, where the Red Guard command was assembling its forces with the intention of offering sustained resistance to the Germans and the Central Rada.

The trains started up… It was painful for us to depart from the region where we had done so much work among the population. However it couldn’t be helped. We would have to separate from our home territory for a time not only physically, but also spiritually. Our absence would give us an opportunity to rethink our convictions but at the same time we entertained the great hope that the triumph of the Counterrevolution was built on sand, that in a few months the Ukrainian revolutionary working population, disoriented at the moment by, on the one hand, the Bolshevik Treaty of Brest-Litovsk; and, on the other hand, by the vile, provocative politics of the Ukrainian Central Rada (lackeys of Germany and Austria-Hungary), would recover its wits and grasp the pernicious role of these destroyers of its destiny and the Revolution. The labouring population needed to organize itself independently this time at the grass roots level and overthrow the executioners without taking orders from provocateurs from the camp of the socialist-nationalists…[24]

I knew the state of mind of the village toilers. I knew how they had prepared for their unsuccessful battle against the onslaught of the German-Austro-Hungarian junkers and the bands of the Ukrainian Central Rada. I knew and I believed this state of mind was intrinsic to the toilers and wouldn’t change just because their organization had sustained heavy blows right off the bat. I deeply nourished the hope this organization could be rebuilt on a more solid basis, more self-assured in its tactics and with a firmer spirit. I and my friends – Savva Makhno, Stepan Shepel, and Vanya Kh. (who were sent to me from Gulai-Polye to warn me not to attempt to return illegally under any circumstances) all took part in a lively review of the recent past.

We decided to gather our comrades together in Taganrog and jointly work out a plan for our return to Gulai-Polye and its raion to carry out underground work. Certainly we recognized the peril which threatened the life of each of us not just in Gulai-Polye but on the way back. But we were aware that in order to overthrow the German-Ukrainian Counterrevolution we couldn’t count on help from the Russian Bolsheviks with their “proletarian revolutionary government” and their organized military force because of their loyalty to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. The downfall of the Counterrevolution could be accomplished only by means of plans based on the firm revolutionary consciousness of the toiling masses, in fact plans designed by the toilers themselves. And we wouldn’t let anything stop us from getting back to our own territory, into the ranks of these toilers.

But, I repeat, before us was the preliminary task of assembling all the comrades who were retreating before the Counterrevolution by various routes and jointly working out and approving plans for our return home and for the underground work we intended to carry on there.

With this goal my brother Savva Makhno travelled from Taganrog to the zone of the military-revolutionary Front, 70 versts from the city, to search out comrades and direct them to Taganrog.

In the meantime I made contact with some members of the Federation of Taganrog Anarchists as well as with other friends and also got caught up in an affair which caused a sensation in Taganrog at the time involving the commander of one of the Anarchist detachments, Maria Nikiforova.

Chapter 2: The Disarming of Maria Nikiforova’s Detachment.

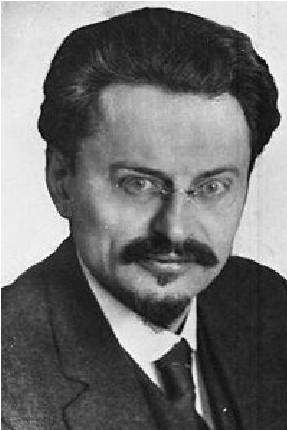

All the Bolshevik Red Guard detachments which survived the blows of the German — Austro-Hungarian expeditionary armies sought more or less prolonged respites in the deep rear, at a respectable distance from Front. Many Anarchist detachments acted the same way. In this was evident that spirit of negligence and irresponsibleness which had quietly infected many – oh, how many! – of the revolutionaries as a result either of the betrayal of the Revolution in the Brest-Litovsk Treaty (a betrayal in which both the Russian Bolsheviks and the Ukrainian socialists were guilty), or on account of other causes which I don’t consider necessary to mention in the present chapter. But there was a noticeable lack of discipline in the ranks of the revolutionaries who were struggling to defend the Revolution against the Counterrevolution. As a result of this situation of low morale, I found myself in the presence of many detachments which were no where near the Front, including the Anarchist or, more accurately, anarchic detachment of Maria Nikiforova.[25] The Bolshevik-Left SR government, like any other government, couldn’t tolerate a detachment of this stripe and proceeded to find fault with its withdrawal to the rear. Of course the Bolshevik-Left SR authorities intended to exploit the revolutionary Anarchists in the struggle against the Counterrevolution so these intransigent revolutionaries would become cannon fodder on the military fronts. But here suddenly the authorities were confronted with a detachment under the command of a woman Anarchist joining the Bolshevik detachments in the rear. The authorities’ plans had been disrupted and they set about restoring order. The timing was propitious for dirty deeds – this was the time when Lenin and Trotsky had gone completely berserk – destroying the Anarchist organizations in Moscow and launching a campaign against the Anarchists in other cities and in the countryside. The Left Socialist-Revolutionaries in power raised no objection to this. That’s why the Ukrainian Bolshevik — Left SR authorities hastened to clamp down on the Anarchist Nikiforova’s detachment which arrived in Taganrog along with Red Guard detachments.

The Ukrainian government ordered a detachment under the command of the Bolshevik Kaskin (which had just fled from the Front) to arrest Maria Nikiforova and disarm her detachment. Kaskin’s soldiers arrested Maria Nikiforova before my very eyes in the building of the UTsIK of Soviets.[26] As they were conducting her out of the building in the presence of the prominent Bolshevik Zatonsky,[27] Maria Nikiforova demanded an explanation from him: why was she being arrested? Zatonsky prevaricated: “I don’t know.” Nikiforova called him a lying hypocrite. So Nikiforova was arrested and her detachment disarmed.

However Nikiforova’s detachment didn’t fold and allow itself to be absorbed into the Bolshevik Kaskin’s detachment. Instead her troops insisted on knowing what the authorities had done with Nikiforova and why they had been disarmed.

Joining them in this demand were all the detachments retreating from Ukraine into Taganrog and the local Taganrog Anarchists. The Taganrog committee of the Party of Left SocialistRevolutionaries also supported the Anarchists and the troops of Nikiforova’s detachment.

In short order I signed a telegram on behalf of myself and Maria Nikiforova to the commander-in-chief of the Ukrainian Red Front, Antonov-Ovseyenko,[28] requesting his opinion about the detachment of the Anarchist Nikiforova and asking him to order her release, the re-arming of her detachment, and the assignment of her detachment to a definite sector of the Front following its outfitting with weapons and equipment.

The commander-in-chief Antonov-Ovseyenko dispatched a response to the authorities installed in Taganrog, with a copy to us in care of the Federation of Anarchists. The telegram bore the practical tone of an experienced commander:

“The detachment of the Anarchist Maria Nikiforova, as well as Comrade Nikiforova herself, are well known to me. Instead of concerning yourselves with disarming such military units, I would advise you to concern yourselves with creating them.” (signature)

At the same time there were many other telegrams protesting the authorities’ action or simply expressing support for Nikiforova and her detachment. These came from the Front from Bolshevik, Left SR, and Anarchist detachments and their commanders which had distinguished themselves in battle.

The Yekaterinoslav (Bryansk) Anarchist armoured train[29] under the command of the Anarchist Garin arrived in Taganrog in order to register its own revolutionary protest against the highhanded, backstabbing authorities.

All this had not been initiated by those who ordered the arrest of Maria Nikiforova and the disarming of her detachment, nor by those who carried out this order. Rather the affair was instigated by the central authorities, safely in the rear, who put together false evidence against Maria Nikiforova and her detachment, evidence which supposedly implicated her in the pillaging of Yelisavetgrad which she had occupied in March 1918, driving out the Ukrainian nationalists. In this way they concocted a criminal case.

Here’s the straight goods: the Bolsheviks are experts at fabricating lies and carrying out mean acts against others. They exaggerated the evidence against Maria Nikiforova and her detachment and made a case out of it.

Maria Nikiforova was tried before a military court during the last week of April. The judges’ bench was occupied by two Left SRs from their Taganrog federation, two Bolshevik-Communists from their local Party branch, and one Bolshevik-Communist from the central Bolshevik-Left SR government of Ukraine.

The proceedings were carried on with open doors and bore the character of a court of revolutionary honour. Here I must note that the Left SRs behaved fairly towards the accused Nikiforova and were hostile towards the agents of the government accusing her.

The central authorities recruited witnesses from the refugees present in the city to testify against Nikiforova, striving with a mixture of truth and lies to pin a criminal conviction on her which would allow them to execute her. But the tribunal was genuinely revolutionary and impartial, and most of its members were politically and juridically independent and not influenced by the provocations of the government’s hired agents.

Testifying before the court were many of the spectators attending the trial, which gave to the investigation of this matter almost the character of a forum at which anyone present could speak freely.

I remember the trial as if it had happened today: Comrade Garin, one of those who had known Nikiforova and her detachment at the Front, spoke up. In a fiery speech he told the judges and all those citizens present that in his opinion “if Comrade Nikiforova now submits to the court, it is only because she sees that most of the judges are real revolutionaries and believes that she will emerge from here with her detachment restored and rearmed so they can go fight against the Counterrevolution. If she did not have faith in the court and predicted that it would follow the exhortations of the government and its provocateurs, I would know about this and I declare here and now in the name of the crew of the armoured train that we would liberate her by force...”

This declaration by Garin ruffled the revolutionary judges. Nevertheless they replied to him that the court had been set up on the basis of complete independence from the government and would carry the matter through to its logical conclusion. If Maria Nikiforova was found guilty, she would receive her just punishment from those who had arrested her. If the evidence against her was proven false, the court would exert itself to make sure Nikiforova recovered her weapons and equipment and she would be free to leave Taganrog for the Front or wherever she wished to go...

As a result of the inquiry, the court decided there were no grounds to convict Nikiforova for the pillaging of Yelisavetgrad. The court decreed she be released immediately and that the weapons and equipment seized by Kaskin’s detachment be returned to her detachment without delay. She was granted the option of putting together an echelon and departing for the Front, which is what she and her detachment wanted to do anyway.

The next day Nikiforova already turned up at the Federation of Taganrog Anarchists. We issued a leaflet, signed by a council of Anarchists, which exposed the falsification of the case against Nikiforova by the central Ukrainian Bolshevik government and Commander Kaskin, and accused them of having an odious and hypocritical attitude towards the Revolution itself. This leaflet was written by me personally and was not endorsed by some of the comrades because of its scathing attack on Kaskin.

Then, while Nikiforova’s detachment was being re-fitted, Nikiforova and I and one other comrade from the Taganrog Federation arranged a serious of mass meetings, sponsored by the Federation. These meetings were held in the Taganrog tanning and metallurgical factories, in the city centre, in the Apollo theatre, and in other parts of the city. The theme of these meetings was: “The defense of the Revolution against the Expeditionary Counterrevolutionaries – the German- Austro-Hungarian armies and the Ukrainian Central Rada; and in the rear – against the reactionary government which is strong in the rear but feeble at the Front.” Everywhere, on our signs and at the meetings, I presented myself as “Skromny” (my prison nickname).[30] Our position at many of the meetings drew support from the Taganrog Left SRs. The meetings were an enormous success.

I recall at one of the meetings (at the tannery) the Bolshevik big shots Bubnov[31] and Kaskin showed up. They ended up stamping their feet in frustration when the thousands of workers present wouldn’t let them finish their speeches, shouting: “We’ve heard enough from you. Now give Comrade Skromny the floor – he will answer you!...” When I responded to Bubnov (Nikiforova answered Kaskin), the masses of workers whistled at Bubnov and Kaskin, yelling:

“Comrade Skromny, run them off the platform.”

After our speeches at the Taganrog meetings, Nikiforova[32] was busy with the preparations of her detachment to advance to the Front.

I was busy preparing for the conference of Gulai-Polye comrades, who were already beginning to arrive, one by one.

Chapter 3: Our Conference.

As soon my brother Savva reached the appointed sector of the Red Front, he met Comrades Aleksei Marchenko,[33] Isidor Luty[34] (also known as Petya), Boris Veretelnik,[35] S. Karetnik,[36] and many others. He directed all of them to a certain address in Taganrog while he remained for some time at the Front. When all the comrades we could find had assembled in Taganrog, we set a date for our conference in the building of the Federation of Taganrog Anarchists. The conference took place at the end of April 1918. I opened the proceedings with an invitation to all the comrades present to express their opinions on where we had gone amiss in organizing the free battalions. I also wanted to know if anyone had noticed advance signs that agents of the Ukrainian Central Rada and the German headquarters were preparing to arrest the Revkom, the members of the Soviet, and members of the GAK in general.

A wholescale exchange of opinions led us to the unanimous conclusion which I had already drawn in discussions with some of the comrades while still in Tsarevokonstantinovka, namely that if the Revkom had not sent the GAK’s detachment to the Front, but held it back until the day of departure of the other military units, then the conspiracy would have had no chance of success, even in my absence from Gulai-Polye. The Jewish Regiment would not have been called up out of order to replace the other regiment which came off duty early. And generally, the Jewish Regiment, despite its habitual tendency to accommodate itself to anyone and everything, would never have decided to take action against the Revkom on behalf of the Germans and the Ukrainian Central Rada if it had known there were other armed units stationed in the centre of Gulai-Polye. But the conspirators convinced it that there were no other units in the centre of Gulai-Polye, and that they could start the process which would then be finished by the German regiments and the detachments of the Central Rada which were advancing triumphantly and were already closing on the village.

“The rank-and-file Jews were really foolish,” said some of my friends, “they were so eager for glory, they sucked up to the high command of the invaders...” The German-Austro-Hungarian command actually thanked them, along with the leaders of this vile counterrevolutionary conspiracy.

Of course this accurate analysis of the role of the Jewish Regiment in the conspiracy caused great mental anguish to those who had fought so hard against antisemitism. They found themselves not only being arrested by the Jews, who were acting hand-in-hand with antisemites in this vile business, but also being “detained” until the arrival in Gulai-Polye of the Germans, Austro-Hungarians, and nationalists – notorious for carrying out pogroms of Ukrainians – in order to hand them over to these executioners. These comrades found it impossible to relieve their mental anguish while they were forced to be inactive. For many at the conference their pain was so great they started weeping. But of course no one dreamed of carrying out pogroms, about taking revenge on Jews for this vile affair of a few of them. Generally speaking, all those who call the Makhnovists pogromists are slanderers. For no one, not even the Jews themselves, ever fought so fiercely and honourably against antisemitism and pogromists in Ukraine, as the Anarcho-Makhnovists. My notes prove this incontrovertible fact.

I noticed the mental anguish and mood of despair which gripped almost all of my friends was causing them to avoid discussing the problems which our conference was supposed to deal with. I myself began to suffer from the same malaise and had to muster all my strength to overcome this overwhelming feeling of depression. Again I put one basic question before the group: should we return to Ukraine, to our own territory? Or should we stay in one of the Russian cities and carry on as we were now, lamenting the past but not going back and trying to rectify matters.

“Let’s go back! Let’s go back! We’ll all go back!...” One after another the suddenly cheerful voices chimed in. A minute earlier these voices had been silent, almost as if the hall were empty.

Then we set ourselves three additional questions, which were decided by us in a positive way. Here are the decisions we arrived at:

-

We would return to our own raion illegally and organize initial groups of from 5 to 10 persons each among the peasants and workers. These would be combat groups, designed to involve the labouring peasantry on a wide scale in the struggle against the German-Austro-Hungarian Expeditionary Army and the Ukrainian Central Rada. In each instance of popular rebellion against these counterrevolutionary conquerors, we would try to be in the thick of things, imparting to them a more focused and resolute character.

-

All of us couldn’t return to our own region at the same time; however, the first comrades to return would have to mark their successful return by organizing merciless individual terror against the commanding officers of the German-Austro-Hungarian armies and detachments of the Ukrainian Central Rada. They would also have to organize collective peasant attacks on all those pomeshchiks who fled from their estates in the days when their lands were divided up and the surplus livestock and machinery removed but had now returned to “their” estates in the wake of the invasion of the Expeditionary Army and its auxiliary Central Rada forces. In planning peasant attacks on the pomeshchiks, priority would be given to eliminating the pomeshchiks themselves as well as the leaders of their punitive detachments which (according to the statements of peasants who have just arrived from that region) had at their disposal a special kind of detachment from the regular German-Austro-Hungarian armies.

The goal of these counterrevolutionary detachments was to oversee the taking back of the land from the peasants, along with livestock and machinery; and the beating, flogging, and shooting of rebels.

The goals of our intended organized peasant attacks on the pomeshchiks and the military units which were based on their estates are as follows: (a) the disarming of the pomeshchiks and their military units; (b) the confiscation of their monetary wealth and the killing of those who had been involved in beating, flogging, and shooting peasants and workers. Their guilt in these evil deeds would have to be established on the basis of the testimony of peasants from those towns and villages where these gentlemen exercised their lynch rule or where they collaborated with the German-Austro-Hungarian command in arbitrary punitive actions.

-

The defense of the Revolution required armaments and equipment. The toilers would have to obtain these from their enemies. We were going home with one thought in mind: to smash the counterrevolutionary Front so we could live in freedom in a new kind of society, or die trying. We, as a group and individually, would strive to organize, in the villages among the toilers, free battalions and auxiliary light combat units to disarm the invading troops and the Rada’s detachments and, in the event of stiff resistance, to simply annihilate them.

These three simple points were drawn up at our Taganrog conference for the struggle with those who arrived uninvited on revolutionary soil, forcibly set up shop, and then punished all those who only dared to stand up for their own right to a free and independent life. It was this program which committed all of us to returning to Gulai-Polye.

As we worked out the details of this program, details which were extraordinarily important in such an unequal struggle, without realizing it I became the motivational force inspiring the comrades around me to move forward towards our intended goal, a goal which would demand self-sacrifice and heavy responsibilities from each of us. Our realization of this caused us to worry. Nevertheless we resolved to exert our maximum effort to reach our goals and in the process to put our toughness to the test.

Thus we would return to Gulai-Polye, to our own raion. We would return in order to raise a revolt of the peasants and to struggle with them and, if necessary, to die in this struggle for the social revolution. We would clear the way for the possible creation of a communist Anarchist society.

But how would we return? In groups or individually?

We left this question to be decided by each individual on their own. The main thing was, that towards the end of June or early in July we would all meet in Gulai-Polye or near there. This would be the time of field work. All the peasants would be in the fields – harvesting crops. In would be easy for us to meet with the peasants and talk to them about what needed to be done. We could learn their opinions, find out their true feelings. Then we could choose the toughest ones, the ones most devoted to the cause of liberty, and form a vanguard from them for the whole of Gulai-Polye and its raion. We knew that Gulai-Polye was the logical place to be the centre of an all-encompassing peasant revolt. We knew that, in spite of the provocational activity of agents of the German command and the Central Rada, the population of Gulai-Polye and its raion had faith in its own revolutionary drive. It was the duty of the Gulai-Polyans to be the first to revolt and to clearly spell out the goals they were striving for in order set in motion the whole toiling population of other raions.

“The three-point program we have worked out,” I said to the comrades, “is to some extent a significant step forward towards setting our goals before the toiling population. These goals can only be achieved through a broad-based insurrection – an insurrection which will require a supreme revolutionary effort demanding the utmost in courage and ruthlessness. But our program is only the first step. In the final analysis we will define these goals together with the toilers of our region as we develop, jointly with them, our direct action against the Counterrevolution...”

Then Comrade Veretelnik raised an issue concerning a member of our group, Lev Schneider, and his vile and treasonous role during the key Gulai-Polye events of April 15–16.

Veretelnik described this role as a betrayal not just in relation to our group, but also in relation to the ideal of Anarchism.

“Lev Schneider,” said Veretelnik, “either lost his mind during those days, or his revolutionary mindset had imperceptibly been replaced by old-fashioned philistinism. Whatever happened, he ended up on what appeared to be the stronger side... But this isn’t the main thing. Lev Schneider joined the enemy not only physically but mentally. He was not only in the ranks of the Jewish bourgeoisie who met the Germans and the Ukrainian Central Rada’s thugs with bread and salt, but he was the first to make a welcoming speech in Ukrainian – a counterrevolutionary speech. Then he led the haidamaks in breaking into the office of our group where he ripped up the portraits of Bakunin, Kropotkin, and Aleksandr Semenyuta[37] and trampled on them. These were people whom, according to his own declarations, he loved... Jointly with the nationalist thugs he destroyed the Group’s library, despite the fact that even in the ranks of the nationalists there were people who gathered up our literature, books, newspapers, and proclamations and took them away to preserve them. Some of these people passed a message to our comrades that this literature would be returned to us at an appropriate time.

“I insist,” declared Veretelnik, becoming quite agitated, “that the members of our Group here at the conference make a definite statement about Schneider’s treason. His role was that of a provocateur, and I believe for that Lev Schneider should die.”

The comrades supported everything Comrade Veretelnik said about Schneider. As to the question about how all of us, or each of us individually, would act upon encountering Schneider, we left that open for the moment. We considered that this question could be decided finally only in Gulai-Polye, and by the group as a whole. But the conference did unanimously agree that the final decision would have to involve the killing of Schneider.

Our conference concluded with the proposal to all the participants to use the next month and a half to familiarize themselves with the peasants and workers of the Don region, to the extent that this was permitted by the military situation and travel conditions. We also decided to visit a number of large cities in central Russia: Moscow, Petrograd, Kronstadt, etc., and make an in-depth survey of what was going on there. We wanted to find out what the Bolshevik — Left SR government was up to and how the toilers were reacting. These were the toilers who had sacrificed themselves and were continuing to sacrifice themselves in the struggle for a new, free society. But to us peasant Anarchists it seemed the foundations of this society were not being put in place by the toilers themselves, but rather they had handed off the job to a new set of rulers…

With this goal, we broke up into groups. Comrade Veretelnik and I decided to visit Moscow, Petrograd, and Kronstadt. My brother Savva with comrades Stepan Shepel and Karetnik decided to go to the Front with the intention of slipping through to Gulai-Polye raion.

Comrades Vanya “Stepanovsky,” P. Krakovsky, Korostelyev, A. Marchenko, Isidor Luty, Kh. Gorelik, and Kolyada[38] also decided to visit Moscow and return from there via Orel and Kursk. They proposed to wait in Kursk until Veretelnik and myself arrived, so we could proceed together to Ukraine across the Front in the direction of Kharkov.

In parting we confirmed our strong desire to return to our Gulai-Polye raion by the end of June or early July for the purpose of liquidating the Counterrevolution which had established itself there.

Chapter 4: The Flight of the Agricultural Communes and My Search for Them.

When Veretelnik and I were leaving Taganrog, I received news that echelons were passing through the city in which there were refugees from the agricultural communes organized in Gulai-Polye raion by our Group. (In Volume I of my memoirs I have already mentioned I was a member of one of these communes and carried on responsible work in it.) Upon receiving this news, I parted with Veretelnik and hastened to find the communard refugees. I wanted to meet my girl friend[39] who, as a member of the commune, was retreating along with everybody else. And I wanted to meet with the communards generally, in order to exchange views with them on our subsequent course of action. I wanted to cheer them up and share with them my candid views of the future based on the plans of our Taganrog conference. I was one of the movers- and-shakers in setting up the communal life style and felt a definite responsibility for its fate. Now my thoughts were only about them. I desperately wanted to overtake them and shower them with hugs and kisses for the brave beginning they had made in solving one of the most basic problems of the revolutionary practice of working people.

Before my departure from Taganrog for Rostov-on-Don I met with the sailor Polonsky,[40] commander of the Gulai-Polye Free Battalion, and his brother. Now our Polonsky declared to me that he wanted neither to rejoin his old party – the Left SRs – or remain in the ranks of the Anarchists. He was going to try to study Bolshevism. If he didn’t find in it the force which could screw the head off the armed Counterrevolution, then he would revert to passive neutrality, since he valued his health, “without which life is impossible in the existing state of things.”

I had a good laugh at this, gave him the 1,000 rubles he requested from the funds of the Revkom, and left for Rostov-on-Don. In Rostov I wandered along the railway tracks for three days searching for my fellow-communards, but in vain. Here I again encountered the commander of the Red Reserve Forces of South Russia, Belenkovich,[41] who had supplied GulaiPolye with weapons (see Volume I of my memoirs). Without any beating about the bush we spoke candidly about the general causes of the swift retreat of the Red Guard forces and, in particular, about the Gulai-Polye events of April 15–16.

Belenkovich was a very direct and frank person, and gave the impression of being a stalwart soldier of the Revolution. However he was a Bolshevik, who not only thought but also acted according to the program of his Centre which was made up of between three and five “head-priests.” This circumstance provoked me to protest, since in my limited experience as a soldier of the Revolution I had already experienced several moments when it was necessary to act not according to central orders, but according to what was demanded by the concrete circumstances. Of course, these actions were not in conflict with the ruling ideas of the Revolution.

Belenkovich told me he had personally ordered that a separate echelon be made available to our communards, so they could make their withdrawal more comfortably. According to him, they had already passed through. “Obviously they have now moved on further, into the heart of the country, but where they have gone it’s hard to say. They might have taken the railway line to the North Caucasus or they may headed towards Lisk and Voronezh.” Belenkovich advised me not to rush after them in the Lisk-Voronezh direction since, according to his words, there were often counterrevolutionary Cossack detachments operating along this line who stopped trains and shot any of the passengers who seemed the least bit suspicious...[42]

Chapter 5: My Meeting With the Rostov-nakhichevan Anarchists and the Refugee Anarchists Arriving in Rostov.

I didn’t know what our Rostov-Nakhichevan[43] comrades were up to in those anxious days. During 1917 and so far in 1918, these comrades had published a serious weekly newspaper – The Anarchist. From this newspaper it was evident that these comrades were exerting an influence on the working people of the city and its environs and were carrying on educational work among the workers and organizing them for military action. At the same time they were trying to mould the Anarchist movement into a tightly-run organization. Now, in the first days of my sojourn in Rostov, I couldn’t find their newspaper and didn’t run into any of the comrades of the Rostov-Nakhichevan group.

Then on the very first day when I abandoned any hope of finding members of the agricultural communes of Gulai-Polye raion and remained in Rostov only with the goal of looking up Anarchists, I came across the evening newspaper Black Banner, a broadsheet with printing on both sides, containing news articles about the situation at the Front of the Revolution versus the Counterrevolution. The articles were incomplete, mostly inaccurate, and in some cases just plain wrong.

The editors of this much talked-about Anarchist rag kept moving their operation from one hotel to another which made it difficult for me personally, as well as many other Anarchists arriving in Rostov from Odessa and other cities of South Ukraine, to track them down and find out what kind of people they were.[44]

I recall that I circulated about the bazaar – flea market with the intention of buying some underwear I could change into after wearing the same underwear for three weeks. At this bazaar I ran into Comrade Grigori Borzenko[45] – a serious comrade who had worked at one time or another in both Odessa and Kharkov. Actually we didn’t know each other before this encounter. But we were introduced by Comrade Riva, one of the members of the Maryupol group of Anarcho-communists. My first question was: “Comrade Borzenko, do you know who is publishing the street paper Black Banner?”

Comrade Borzenko’s reply was curious: “They say this newspaper is being published by three Anarchists of some kind. But to me it seems it is being published by people who want to align themselves with the powers that be: that means they are our enemies.”

I never succeeded in meeting the publishers of this enterprising evening “anarchistic” newspaper. Apparently many of our other comrades had the same experience. They talked about this newspaper and its publishers among themselves; they said that it was published by people who had money in their pockets and wanted to make more money. After reading two or three numbers it was obvious to me that it was published by people who were used to engaging in commerce with goods and with their own consciences. These were the kind of people who travelled through the Front without stopping, who had probably encountered peasants and workers only because in a revolutionary situation it was impossible to avoid them: for the toilers were in the forefront when the Revolution was victorious – and also when it was in its death throes.

But to undertake anything against these pseudo-Anarchists at the time was impossible for two reasons. In the first place, our movement was split into a whole bunch of groups and grouplets which did not even share a common goal, never mind the capability of unified action at the moment of revolution. They accommodated in their ranks anyone who fled from other tendencies in order to avoid responsibility at the revolutionary moment. Under the cover of the Anarchist principle “freedom and equality of opinions are the inalienable right of each person,” they got away with all sorts of stuff, including acting as paid spies for the Bolshevik-Left SR government. Secondly, this was the time when the campaign of Lenin and Trotsky against Anarchism was still going on, and any action on our part against people calling themselves Anarchists was liable to be misconstrued and would play into the hands of the persecuting authorities.

The sad part of this was that the Russian Anarchists, being fragmented and not having behind them a broad-based, organized mass of working people, began to be drawn into the orbit of the Bolshevik-Left SR government without hardly admitting it. The government noted this development with approval and intended to draw certain advantages from the situation, since its most dangerous opponents were the revolutionary Anarchists.

The government gradually began to allow the Anarchist press to start up again; the authorities wanted to find out which Anarchists had to be reckoned with, and which could be safely ignored. It was then noticeable that the idea of collaboration began to appear in our ranks: ugly, jesuitical collaboration. The most sophisticated practitioners in the field of mercenary collaboration ceased to worry about organizing the forces of their own movement; they defected to the Bolsheviks while continuing to call themselves Anarchists. And they often confounded their defection with the principle of “freedom of opinion,” a principle which they had no intention of abandoning – on the contrary, they exerted themselves to entrench it in the Anarchist ranks.

This was a very serious moment both for the Revolution and for Anarchism – a moment which demanded a tremendous effort from the collective intelligence and energy of the Anarchists – from Anarchists who had been educated at the expense of the toilers before they entered the movement. They had learned how to teach and how to speak and write well. And now, alongside the Front where the toiling masses were fighting with weapons in hand, they enlisted in the Bolshevik cultural-educational sections in droves as “consultants”… And the impression was created that for this kind of Anarchist-revolutionary the life of the Anarchist movement was alien, because working in the movement required great sacrifices and involved exposure to great danger. And they were recruited of course not to work, but to advise others how to work. With their grossly incorrect understanding of the tasks of revolutionary Anarchism at the moment of Revolution, they didn’t realize that vipers can appear at the very heart of the Revolution and not just at the fronts against the Counterrevolution. This led to the horrors of political, and sometimes also physical, annihilation of the bearers of the revolutionary ideal. These comrades, sharing our designation and our beliefs (in most cases misapplied), inflicted blow after blow not only on their own fellow-Anarchists, but also on the broad revolutionary toiling masses. It is often the case in revolutions that the toiling masses are more perceptive than those who choose only to act as advisors, without carrying any responsibility and even not spending much time among those whom they are advising. It’s true, some of our proletarian comrades did not understand the tasks of revolutionary Anarchism any better. I’m thinking about those workers who, due to some set of clearly accidental circumstances, also got it into their heads they were so much wiser than their fellow-workers that they should act as advisors without taking on any responsibility for the consequences of their advice. These comrades were oh so proud of their own professionalism. But can we really blame them for all this? No, we shouldn’t. Their conduct resulted from the lack of discipline and disorganization in our movement, which spawned all kinds of negative forces having a ruinous effect on its growth and development.

My sojourn in Rostov-on-Don, my encounters with Anarchists – especially refugees like myself, and also my daily browsing of the speculative newspaper Black Banner, more and more focussed my attention on the negative features which, due to the force of circumstances, were becoming entrenched in our movement and gnawed away at its vital revolutionary organism. Furthermore, I was told that just before Rostov was attacked by the Germans and the White Don Cossacks, the house of the Rostov-Nakhichevan Group was completely trashed by refugees, including those who called themselves Anarchists and had received shelter in it for some weeks. These people had been treated as honoured guests who were political activists deserving of a well-earned rest and they responded by lolling about on the plush furniture and spitting on the floor. In spite of all this, I was full of faith and hope that in the future I would encounter far better situations among nearest and dearest comrades. My faith and hope were strengthened by attending a meeting organized by the local Rostov-Nakhichevan Anarchists in the Rotunda.[46] The ideas expressed by them at this meeting showed me that here we had robust forces. This moment of general recoil of the Revolution forced them to concentrate on planning for underground work. It wasn’t their fault if refugee activists of our movement, searching for a place of rest and finding it in a house of Anarchists, failed to protect it in a moment of panic and in fact collaborated in plundering the furniture and decorations.

With faith and hope in a better future, I, along with between 30 to 35 other comrades from various cities of Ukraine, in the days when the revolutionary city of Rostov-on-Don was being evacuated, made arrangement to travel with a Red artillery base under the command of Comrade Pashechnikov, who was sympathetic to the Anarchists. We awaited departure from Rostov to Tikhoretskaya, from where the artillery base would proceed along the North Caucasus railway line, through Tsaritsyn and Balashov to the Voronezh military zone of the Front.

We were all enrolled as the crew of an echelon, and many of the comrades were assigned guard duties. Being already enrolled, I was still had the opportunity to address the workers of the Rostov plants and factories on three occasions in the name of the GAK. My goal was to counteract the point of view expressed by the speculative “Anarchistic” newspaper Black Banner, and also to explain the role of revolutionary Anarchists in relation both to the Front against the Counterrevolution, and to all those phenomena which were ruining the movement. However the moment for such speeches was inauspicious. Revolutionary Rostov was in the throes of a hurried evacuation. The commander of Rostov okrug, Podtyolkin,[47] had already moved out of his home into a railway car hooked to two engines at full steam. His example was followed by other revolutionary institutions. It goes without saying that the apprehension of the powers that be was transmitted to that portion of the population which supported the Revolution. The people and various organizations which had fled to Rostov now began to flee even further. After them trailed the military and civil authorities of Rostov and its okrug, as well as that sector of the population which actively supported the Revolution.

The evacuation took place in two directions: to the north towards Liski — Voronezh, and to the south on the other side of the Don River at Bataisk where the Red command threw up a front and hoped to hang on as long as possible. A truly nightmarish scenario developed. When the evacuation started, among the population, especially the Cossack part of it (which was wavering between supporting the left-wing Reds or the right-wing Whites), sprang up gangs of robbers which were led by professional thieves who roamed about the country in those days, fishing in troubled waters. Pillaging grew with extraordinary rapidity and on a fantastic scale and it grew under the influence exclusively of the basest passions of thievery and revenge: revenge on those who welcomed the victory of the Counterrevolution and on those who habitually occupied a neutral position...

While observing this phenomenon, so alien to the Revolution, I frequently asked myself: isn’t it possible to put an end to this?

And the answer I found was that at such a moment as the hasty evacuation of the vanguard of the Revolution, it is almost impossible to direct one’s attention to those who, taking advantage of the unlimited right to freedom and not bearing any responsibility for its realization in our practical social life, need to be restrained and shamed. For our social life, in order to concretize real freedom, requires direct and genuine co-operation from all the people who only through their own efforts can develop and defend such freedom for themselves and for their society.