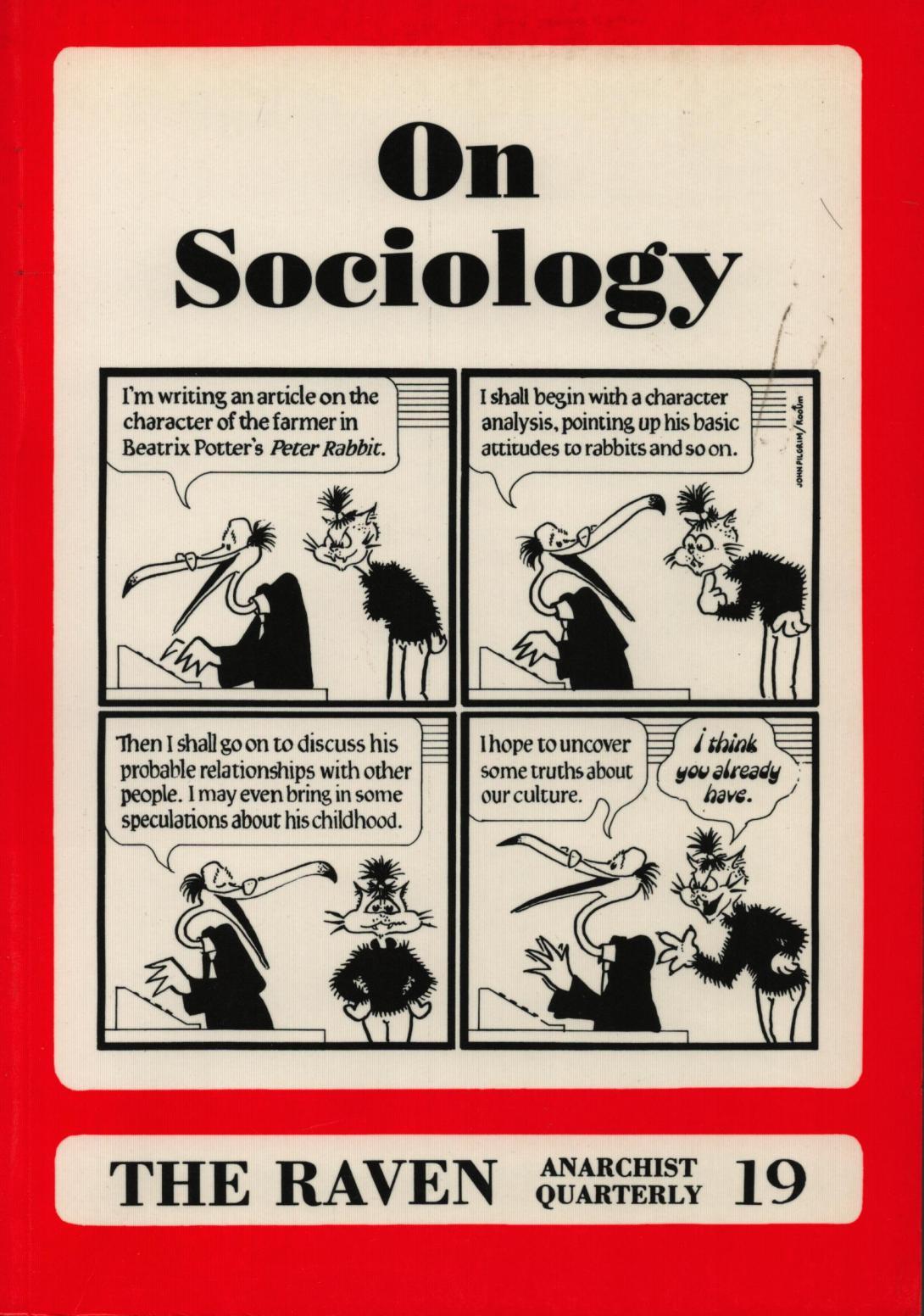

Cover artwork by Donald Rooum.

Various Authors

The Raven: Anarchist Quarterly 19

On Sociology

C.W. Mills

The Vision of Sociology

John Ebbrell

Structure and Change: the Central Sociological Problem

Professor Sprott

Human Groups and Morality: An Anarchist View?

David J. Lee

Unreason and Uncertainty in the Practice of Sociology

Confessions of a GP sociologist

1. Being objective and being certain

2. Established facts or objective evidence?

Individualism and sociological theory

Robert Nisbet

Social Authority and Political Power

John Pilgrim

Change or Acceptance: human nature and the sociological perspective

Colin Ward

Martin Buber - Sociologist

Robert Nisbet

Radical and Sociological Pluralism

Ronald Fletcher

Comte for the World Today

Robert S. Lynd

Why is Sociology?

Angus Calder

Samuel Smiles: The Unexpurgated Version

Harold Barclay

Communication 1

John Pilgrim

Anarchists and Sociology

Peter Berger, in his entertaining introductory book Invitation to Sociology,[1] noted that there were few jokes about sociologists and one at a party would have to get his or her attention the hard way just like everyone else. That was in 1962. Today the partying sociologist defensively describes himself as a geographer, an anthropologist, or even as an economist, in order to avoid ritual abuse about Marxist revolutionaries and jokes about demonstrators as 'sociology students doing their practicals'. The headlines of 1968, and the television success of Malcolm Bradbury's The History Man, seem to have fixed a stereotype from which few, even anarchists, are immune. "That mild and cautious discipline, sociology, has" in the words of Ian Carter, "acquired a kind of diabolism". [2]

Writers for The Sun, for The Daily Express and similar inheritors of the old fascist cry 'Down with intelligence', pursuing their perennial quest for hate figures, love this caricature. It is rather more surprising to find it among anarchists, not only because of some clear correspondence between the founders of sociology and the early anarchist thinkers, but because many who are now among sociology's leading academics published some of their early work in Colin Ward's Anarchy. If sociology was simply 'Marxist crap' or 'support for a conservative status quo' then one might reasonably ask why Anarchy published Stan Cohen, Laurie Taylor, David Downes et al in the first place.

Well partly it was that the parallels between anarchist and sociological thinking were continuing. There was, though, a further reason. Colin Ward was concerned with 'practical anarchism', with action in society, and sociological insights and findings are valuable to anyone so concerned. They are, or should be, particularly of interest when anarchist and sociological diagnoses still upset people right across the political spectrum who have a vested interest in keeping things as they are. That the scientific discipline so often supports the ideology should be a matter we should celebrate, rather than reacting like a bunch of Tory backbenchers faced with the necessity of reconsidering received ideas.

One polemic that arrived during the preparation for this issue contained ten assumptions about sociology, seven wrong and three debatable. Interested readers can find similar assumptions on the following page under the heading 'What they say about sociology'. This generalised hostility is, on the face of it, odd. No one condemns history as a discipline because Norman Stone is a fan of Margaret Thatcher, or because Eric Hobsbawm is a Marxist. It is taken for granted that their ideological positions will affect what facts they select as important and on that basis we may or may not choose to avoid their books, but we do not condemn the pursuit of history.

Sociology with its emphasis on testable knowledge of the associational facts of human life, its tendency to upset received ideas, its concentration on an historically informed analysis of the present, is more vulnerable. The Greek colonels banned it as Marxist, Stalin condemned it as 'bourgeois ideology', Margaret Thatcher found the questions it asked to be too revealing for her comfort. When we find this unlovely group (not to mention Norman Tebbitt) united in their condemnation of an area it is worth asking why. What have they to gain? Or to fear?

The late Ronald Fletcher, in defence of sociology against those who wanted it limited in universities and banned in schools, pointed to part of the answer:

Sociology is needed as a sound basis for any well considered social and political reform. Now, as always from its inception, sociology seeks knowledge and understanding for the making of a better society: in which the promised benefits of ingenuity and inventiveness can be secured while the threats of [human] evil and tendencies toward dehumanisation can be avoided. Sociology is for understanding - and for use; an intellectual effort towards knowledge - for living; it is here that its essential educational value lies.[3]

Twenty six years ago, writing in Anarchy, I quoted O. R. McGregor to the effect that those who want change must be sociate, as well as numerate and literate. I was much attacked at the time for trying to hand the conduct of our lives over to experts, by those who, possessing 'The Truth' did not want to bother with evidence or argument. The record and legacy of Margaret Thatcher's regime are a sufficient refutation of that attitude. It is no coincidence that sociology is recovering popularity as the appalling effects of the smothering of evidence and the faking of figures during her 'reign' become obvious.

Raven 19 looks at the sociological enterprise and points to a few of the many parallels with anarchist thinking. Errico Malatesta, a man as suspicious of scientific priesthoods as of political leaders, can sum up. What he says about science in general could equally well apply to the social sciences, and isn't a bad maxim for anarchists in general.

To the will to believe, which cannot be other than the desire to invalidate one's own reason, I oppose the will to know, which leaves the immense field of research and discovery open to us ... I admit only that which can be proved in a way which satisfies my reason - and I admit it only provisionally, relatively, always in the expectation of new truths which are more true than those so far discovered. No faith then in the religious sense of that word.[4]

A Note on Contributors

Harold Barclay was until recently Professor of Anthropology at the University of Alberta. he has written a number of times for Freedom and The Raven and is the author of People Without Government and Culture: The Human Way, both of which are stocked by Freedom Bookshop.

Angus Calder is Reader in Cultural Studies at the Open University in Scotland. The author of Revolutionary Empire (Dutton) and The People's War (Cape), his paper on Samuel Smiles was specially prepared for this issue of The Raven.

Michael Duane is the former headmaster of Risinghill Comprehensive and lecturer in Adult Education. Now retired, he is a regular contributor to Freedom and The Raven, and is the author of Work, Language and Education in the Industrial State (Freedom Press).

John Ebbrell is a former sociologist "who gave up in despair with the onset of post-modernism". He is currently engaged in writing a book on Bakunin's sociology.

Ronald Fletcher, who died while this issue was in preparation formerly held Chairs of Sociology at York, Reading and Essex. A specialist in the development and history of sociology, his previously unpublished paper on Comte's relevance to the modern world was sent to us just before his death.

David J. Lee of Essex University is co-author (with Howard Newby) of The Problem of Sociology (Hutchinson), still the best available introduction to the discipline. His feature essay on the need for a science of society and the perils of untempered relativism was specially written for this issue of The Raven. We are particularly grateful to him for giving so much time, so freely, to this particular project.

C. Wright Mills, former Professor of Sociology at Columbia and guru of revolting '60s students, remains a controversial figure. However, The Sociological Imagination is still one of the landmarks of sociology, while The Marxists remains compulsory reading for anyone interested in finding a critical path through that particular intellectual maze. His projected book on the anarchist tradition had not reached any written form before his early death and attempts by his colleagues, while interesting, did not reach the critical standards he had set.

Robert Nisbet, Professor of History and Sociology, is a writer whose anti-state bias has often led to his being classed as a political conservative. Those who do so must have been surprised at his Social Philosophers, with its 60-odd page celebration of anarchism and its relevance for the modern world. His Sociological Tradition is a fascinating discussion of the basic ideas of sociology which has a number of interesting things to say about anarchism. Both books are highly recommended.

John Pilgrim is a former lecturer in sociology who has contributed over the years to Anarchy, Freedom, Peace News and The Guardian. He wrote a pioneering essay on the political implications of science fiction and is one of the few sociologists to have had a record in the Top Ten.

Laurie Taylor holds the Chair of Sociology at York and writes regularly for New Statesman & Society. he was a co-ordinator of the National Deviancy Symposium and, like most of its members, wrote for Anarchy. We would like to thank him for allowing us to reproduce his memoir of Ron Fletcher and modern sociology which first appeared in New Statesman & Society.

Nicolas Walter is a journalist who has contributed to the anarchist press for more than thirty years, and wrote the pamphlet About Anarchist (1969). He has also been active in the peace movement and the humanist movement, and he has run the Rationalist Press Association for eighteen years. His most recent books are the first complete edition of Alexander Berkman's classic The BolsheVik Myth (1989) and an authoritative account of Blasphemy Ancient and Modern (1990).

Colin Ward is the author of some twenty books about anarchism and related subjects, a columnist for New Statesman & Society, and was editor for ten years of that remarkably influential Freedom Press publication Anarchy. UnChaired, unDoctored, indeed unMastered and unBachelored, he is an example to us all.

What they say about sociology

"The intervention of sociology in modern affairs tends to propagate a form of anarchism... based on observational research." (Alex Comfort, Authority and Delinquency)

"How sociology justifies injustice" (headline in Freedom)

"Sociology's essential concepts and implicit perspectives place it close to philosophical conservatism." (R.H. Nisbet, The Sociological Tradition)

"Non-subjects like sociology" (Times leader)

"The political philosophy most consistent with sociology [is] anarchism." (Professor Stanley Cohen, Visions of Social Control)

"The social sciences seek to con people into an acceptance of the world as it is." (Brian Bamford, Freedom)

"Marxist crap" (Tony Gibson, Freedom)

"Sociology is divided between those who are intimately related to computers and those who study the theories of dead Germans." (Peter Berger, 1976)

"Sociology, Social Work, Socialism... it's all the same thing isn't it?" (Tory councillor reported in The Guardian)

"Sociology is spending $50,000 to find the way to a whore house." (American equivalent to above Tory councillor, quoted by R.K. Merton in Social Theory and Social Structure)

"Sociology is about demystification... it is therefore also subversive." (Bob Mullen, Sociologists on Sociology)

"Sociology is a bibliography in search of a discipline. " (Anon, quoted in Lee and Newby, The Problem of Sociology)

"Sociology is a unitary science whose field is the study of the forms of association and their interconnections within social systems as wholes." (Ronald Fletcher)

"Sociology as a unified discipline is fast disintegrating and perhaps that's a good thing - allowing new interdisciplinary things to emerge. There's an anarchist sentiment for you." (Stuart Hall, Professor of Sociology Open University)

C.W. Mills

The Vision of Sociology

The sociological imagination enables us to grasp history and biography and the relations between the two within society. That is its task and its promise. To recognise this task and this promise is the mark of the classic social analyst. It is characteristic of Herbert Spencer - turgid, polysyllabic, comprehensive; of E.A. Ross - graceful, muckraking, upright; of Auguste Comte and Emile Durkheim; of the intricate and subtle Karl Mannheim. It is the quality of all that is intellectually excellent in Karl Marx; it is the clue to Thorstein Veblen's brilliant and ironic insight, to Joseph Schumpeter's manysided constructions of reality; it is the basis of the psychological sweep of W.E.H. Lecky no less than of the profundity and clarity of Max Weber. And it is the signal of what is best in contemporary studies of man and society.

No social study that does not come back to the problems of biography, of history and of their intersections within a society, has completed its intellectual journey. Whatever the specific problems of the classic social analysts, however limited or however broad the features of social reality they have examined, those who have been imaginatively aware of the promise of their work have consistently asked three sorts of questions:

-

What is the structure of this particular society as a whole? What are its essential components, and how are they related to one another? How does it differ from other varieties of social order? Within it, what is the meaning of any particular feature for its continuance and for its change?

-

Where does this society stand in human history? What are the mechanics by which it is changing? What is its place within and its meaning for the development of humanity as a whole? How does any particular feature we are examining affect, and how is it affected by, the historical period in which it moves? And this period - what are its essential features? How does it differ from other periods? What are its characteristic ways of history-making?

-

What varieties of men and women now prevail in this society and in this period? And what varieties are coming to prevail? In what ways are they selected and formed, liberated and repressed, made sensitive and blunted? What kinds of 'human nature' are revealed in the conduct and character we observe in this society in this period? And what is the meaning for 'human nature' of each and every feature of the society we are examining?

Whether the point of interest is a great power state or a minor literary mood, a family, a prison, a creed - these are the kinds of questions the best social analysts have asked. They are the intellectual pivots of classic studies of man in society - and they are the questions inevitably raised by any mind possessing the sociological imagination. For that imagination is the capacity to shift from one perspective to another - from the political to the psychological; from examination of a single family to comparative assessment of the national budgets of the world; from the theological school to the military establishment; from considerations of an oil industry to studies of contemporary poetry. It is the capacity to range from the most impersonal and remote transformations to the most intimate features of the human self - and to see the relations between the two. Back of its use there is always the urge to know the social and historical meaning of the individual in the society and in the period in which he has his quality and his being (our italics).

That, in brief, is why it is by means of the sociological imagination that men now hope to grasp what is going on in the world, and to understand what is happening in themselves as minute points of the intersections of biography and history within society. In large part, contemporary man's self-conscious view of himself as at least an outsider, if not a permanent stranger, rests upon an absorbed realisation of social relativity and of the transformative power of history. The sociological imagination is the most fruitful form of this self-consciousness. By its use men whose mentalities have swept only a series of limited orbits often come to feel as if suddenly awakened in a house with which they had only supposed themselves to be familiar. Correctly or incorrectly, they often come to feel that they can now provide themselves with adequate summations, cohesive assessments, comprehensive orientations. Older decisions that once appeared sound, now seem to them products of a mind unaccountably dense. Their capacity for astonishment is made lively again. They acquire a new way of thinking, they experience a transvaluation of values: in a word, by their reflection and by their sensibility, they realise the cultural meaning of the social sciences.

From C. Wright Mills The Sociological Imagination, Oxford University Press, 1959

John Ebbrell

Structure and Change:

the Central Sociological Problem

"Man makes his own history" wrote Marx, "but he does not make it out of wholecloth, he makes it out of the material at hand." In this phrase Marx encapsulated the tension between structure and agency that is common to sociology, to the many varieties of Marxism, and to anarchism. The view that human conduct is almost totally shaped by common norms, that action follows and is determined by institutional patterns, was dominant at the very time that Rosa Parkes, tired and fed up, decided she would not give up her seat to a white person, and sparked off the Montgomery bus boycott. The "oversocialised conception of man" Dennis Wrong called it[5] and presumably people like Talcott Parsons would have regarded Rosa Parkes' action as an unfortunate departure from pattern maintenance.[6] Certainly it was a rare enough victory for an individual agent within a social structure that did indeed do much to enforce the powerlessness of the American Black.

The founding fathers of sociology, Comte, Marx, Weber and Durkheim, developed the now commonplace view that men were held and sustained within the confines of their social environment. Like Kropotkin and Bakunin they saw that the pattern of people's lives had their causal explanation in the structure of society. Once outrageous, this view had become received wisdom by the '50s and perhaps was given its most extreme formulation by Andrew Hacker when he wrote:

There is no point in discussing power unless one explores the sources of that power. This needs to be stressed because there is strong reason to believe that the institutional structure determines the behaviour of the men who hold positions in it. Put it another way, it does not really matter who the office holders are as individuals; anyone placed in such an omce would have much the same outlook and display much the same behaviour.[7]

This is part of a discussion of America's corporate elite but does contain within it the germ of the anarchist idea that no man is good enough to be trusted with power over any other man. Structure is seen as the main determinant of behaviour and is defined, as the pattern of roles, behaviours and patterns that exist independently of a given individual or group. It must include history because, as Peter Berger has noted: "our lives are not only dominated by the inanities of our contemporaries but by those of people long since dead"[8] The past therefore is part of the social structure. It is one of the constraints with which the individual has to deal and affects his expectations of the present. We don't individually create the society around us any more than we create the rules and conventions governing the language we use.

This determinist view was not just a sociological convention of the 1950s, it was also an anarchist, or at least a Bakuninist convention of 100 years before. "Socialism is based on determinism" he wrote, "whatever is called human vice and virtue is absolutely the product of the combined action of nature and society. Nature creates faculties and dispositions which are called natural, and the organisation of society develops them, or on the other hand halts or falsifies their development. All individuals ... are at every moment of their lives what nature and society have made of them."[9] In other words for Bakunin, as for the founding fathers of sociology, the individual is the product of society. Bakunin characteristically goes further than even the most determinist of sociologists describing the individual as "absolutely and inevitably determined" in another extract.

This rather depressing view was received wisdom in the early 1960s and appeared to give the impression that individual initiative in social change was all but impossible. Sociology at this time was double damned. On the one hand Tory councillors, Daily Telegraph readers and suchlike regarded it as radical because it challenged their conventional wisdom. The refutation of beliefs that the 1944 Education Act had created equality of opportunity, or that poverty had been abolished, created just as much adverse reaction among those unwilling to question their assumptions as earlier suggestions that delinquent behaviour or 'crime' was a cultural product and not a function of original sin. Although Marxism was marginal to sociology at this point the discipline has a 'left wing' reputation among the lay public simply because it tended to show that 'what everybody knew' was, in fact, often wrong.

At the same time the study of sociology tended to have a conservatising effect because it seemed that active attempts at social change were a waste of time. "The enemy of revolution is the necessity to modify cultural patterns as a whole" Comfort had argued and the result, as he warned, could tend "a sort of sociological Fabianism". So Parsonians on the one hand, with their Durkheimian emphasis on social order through pattern maintenance, through to Marxists who took the view that 'no social order ever disappears before all the productive forces for which there is room have been developed' all seemed to be minimising the role of human agency in human affairs. From Marx right across the political spectrum to Talcott Parsons a consensus developed which saw people as mindless infinitely manipulable products of social structures.

Bakunin though, like Marx faced with a similar problem, had written himself a part in the social drama having pointed to the determinism inherent in man as a product of society and he did acknowledge that the relationship was interactive but saw this as "a case of society acting upon itself by means of the individuals comprising it".[10] Here again Bakunin belongs with the founders of sociology. To see people as totally determined is to ignore the ambiguity that lay at the heart of Marx between people as products of society and as makers of history. It is to ignore the Weberian idea of social action and the element of choice within it. Bakunin, Marx, Weber and Freud all felt "that the determinisms to which they pointed could, if grasped, be used as the means by which men could liberate themselves from social constraint. Theirs was a sociology of choice as well as of constraint and order."[11]

The problem lay in the fact that, as Dahrendorf had shown, homo sociologicus was itself a construct resulting from the human capacity for reflexive thinking. Thus because people do things for reasons it is argued that they are capable of choosing and pressing for different institutions. The emphasis should be that people achieve change rather than it being something they suffer willy nilly. This is a stance with which many anarchists will sympathise, indeed it is a part of Malatesta's criticism of Kropotkin, that he was a determinist whose position came close to denying free will. "Science stops where inevitability ends and freedom begins"[12] is good polemic but, like the post-functionalist voluntarism in sociology, really begs the question. While it brings an element of self direction back into human affairs it tends to ignore, or at least play down, the extent to which the concepts and thoughts of the agents are themselves a product of history and socialisation.

A Case History: The East End

A look at racism in the East End of London is illuminating here. Immigration was a fact of life and the East End 'the point of arrival' for Flemings, Hugenots, Irish, Jews and Pakistanis, none of whom was particularly welcomed ... and ... whose arrival occasioned considerable acrimony".[13] The Hugenots seemed to have been more welcomed than most and assimilation appears to have been rapid, but not so rapid as to avoid 'direct action' by journeyman weavers against wealthier masters in the eighteenth century. These riots, annual events for some years, seem to have been class rather than ethnically based but continued a tradition of conflict (started with riots against Flemings and Italians) from which the area has rarely been free to this day.

Ethnically based trouble reappeared With the Irish and in this respect it is worth noting Frank Parkin's observation that in all known instances where racial, religious, linguistic or even sex characteristics have been used for exclusion purposes the group in question will have been "at some time defined as inferior by the state".[14] In other words, a structure of statutes and laws (and concomitant attitudes) dating back to the fifteenth century created a background for closure against the Irish while the increasing poverty of Ireland and increasing wealth of England made sure they kept coming. Structural factors then created both hostility and necessity.

The Jews, though, who arrived in large numbers at the end of the nineteenth century, not only had a pre-existing history of exclusion and re-admission to contend with (i.e. they had previously defined as an alien group whose desirability varied according to circumstances) but they arrived at a time when anti-alien feeling was on the boil. Then, as now, there was bad unemployment and a severe housing shortage. "Harried and hustled all over Europe" Chaim Bermant notes, "they arrived in a situation where the Jews had been scapegoated for everything from cholera to the Ripper murders and were greeted with less than enthusiasm by the organised working class". "We wish you hadn't come" Ben Tillet is reported as saying, while wealthier and established Jews feared for their precarious status and allowed this fear to overcome their sense of ethnic identity to the point of supporting the egregious Arnold White, Evans-Gordon and their xenophobic campaigns.

The situation was ripe for scapegoating and groups like the British Brothers League, supported by a lobby of Tory MPs (then as now with a natural predilection for this sort of activity) used multioccupancy, homelessness, high rents, sweating, real or assumed undercutting and other structural problems resulting from free market capitalism to mount a campaign against 'destitute aliens'. What followed was classic group closure with aristocrats, trade union leaders and Tory lobby running a mass local campaign that put the Aliens Restriction Act on the statute book. It also appeared to convince large sections of the indigenous population that group closure (the restriction of access to resources and opportunities to a limited circle of eligibles, and usually entailing the singling out of certain social or physical attributes as a basis for that exclusion) was a suitable response to structural problems caused by the free market economy. Of course, the very passing of the Aliens Act does illustrate that structure can be an enabling as well as a constraining force.

The Act was also an interference with the free market economy as a result of anti-Jewish agitation in the East End. It could be considered as having a class basis in that Jews were thought to be sympathetic to socialism and anarchism, and unionised Jewish workers had supported the 1899 Dock Strike. The latter appears to have had some effect in lessening xenophobia and it could be said that here there was a choice of class identity over ethnic identity - in other words that agency was more important than structure. Against this it could be argued that structural features of a capitalist economy were creating consciousness of a common class position.

In truth reactions were mixed. Jews and trade unionists, not to mention Jewish MPs, vacillated between class and ethnicity. The passing of the Aliens Act can be seen on the one hand as an example of agency bringing about social change in the face of a structure bent on maintaining a 'free labour market', or as a result of a structure which included a tradition of scapegoating and hostility going back at least four hundred years and arguably to the thirteenth century expulsions. The structural context for East End Jews included the English traditions of anti-semitism and general xenophobia. Charles Dilke may have pointed to inherent evils in the structure of capitalism being the real problem. The Royal Commission on the Aliens Question may have dismissed all the accusations against the aliens, but these agencies were operating against the weight of structural factors plus the other agencies exacerbating racial conflict who were part of the structure for the new arrivals.

The primary structures were as follows:

-

Problems resulting from the economic structure like the need for a reserve army, the necessity to compete with machinery, and the benefits for some employers of exacerbating ethnic conflict to inhibit solidarity.

-

Geographical concentration at the point of arrival of 'perfect strangers' without religious, linguistic or colonial links to mitigate hostility.

-

A long-standing tradition of xenophobia in England generally and of violent expression of this in the East End.

-

A repressed and exploited native population fearing the wors ening of their already appalling condition.

-

Lack of adequate countervailing power to combat xenophobic agents and structures and make common cause with immigrants.

-

The ambivalent attitude of unions, both rank-and-file and leaders.

-

An emerging class consciousness and internationalism.

In summary, then, the xenophobic agencies were operating with massive support from structural factors. Agents making for ethnic harmony could find little structural support, for international class solidarity, insofar as it existed, was itself suspect to the point of being seditious. Which returns us to the centre of the debate about structure and agency and illustrates the relative nature of the concepts. For the immigrant the merging class culture of the East End was part of the structure, perhaps-one of the few welcome parts of the structure, that he encountered. For the Member of Parliament who regarded all unions as, to coin a phrase, 'the enemy within' that very consciousness was an undesirable agent of change.

The history of the East End demonstrates that the free-will/ determinist argument is in the end simplistic. 'Ihe determinists are correct in that primary socialisation sets out language patterns, much of our basic behaviour and to some extent the way we think. For example, a culture where they say 'I took the child for a walk' will have a different attitude to authority to another where the construction has to be 'I went with the child for a walk'. This, though, is not determinism but structuration. Behaviour patterns are strongly indicated but they can be rejected or modified. The key to the relationship between the individual human agent and the determining effect of social structure is history, as Marx, Weber and Bakunin clearly saw. It has been best expressed for the modern reader by Philip Abrams who significantly was both historian and sociologist:

The two-sidedness of society, the fact that social action is both something we choose to do and something we have to do, is inseparably bound up with the further fact that whatever reality society has is an historical reality, a reality in time. When we refer to the two-sidedness of society we are referring to the ways in which, in time, actions become institutions and institutions are in turn changed by action. Taking and selling prisoners becomes the institution of slavery. Offering one's services to a soldier in return for protection becomes feudalism. Organising the control of a large labour force on the basis of standardised rules becomes bureaucracy. And slavery, feudalism and bureaucracy become the fixed external settings in which struggles for prosperity or survival or freedom are then pursued. By substituting cash payments for labour services the lord and peasant jointly embark on the dismantling of the feudal order their great grandparents had constructed.[15]

Professor Sprott

Human Groups and Morality:

An Anarchist View?

This point about groups having standards and spontaneously generating them in the course of the interacting which is the basis of their existence at all, is important from another point of view. Because members of groups conceive of the standards of their groups as outside them individually, because they can be put into words and communicated to a stranger or to a new member, and because they can be a matter of reflection and discussion, one easily gets the idea that they really do come somehow or other from the outside. The individual may have intentions of his own which conflict with the standards of his group and he feels 'coerced'. The standards may, indeed, arouse such reverence that their origin is attributed to some supernatural being. This ... does not happen in smaller groups ... but it does happen in the larger ones of which we are all members. When group standards are thought of as something apart from the interacting of the group members we tend to think of them as somehow 'imposed' upon them. This gives rise to the notion that man is naturally unsocial, and that lawgivers or moralists must come along and rescue him from his nasty brutish ways. This is nonsense. The generation of, and acceptance of standards which regulate conduct and preclude randomness is ... a pre-requisite of social intercourse. It is not imposed from outside upon it. (Our italics)

Human Groups, Penguin, 1969

David J. Lee

Unreason and Uncertainty in the Practice of Sociology

When I crossed the frontier I thought:

More than my house I need the truth

But I need my house too. And since then

Truth for me has been like a house and a car

And they took them

Bertold Brecht

I am grateful to The Raven for giving me this opportunity to comment on some aspects of the current state of sociology in Britain. For one thing, sociologists always jump at a chance to explain themselves and their discipline. My main concern, however, is with the curious situation which has developed over the last decade or so. These have been the years of the 'conviction politician', advocating and implementing so-called 'free market' or neo-liberal doctrines which I and most of my colleagues in the sociology profession view as fundamentally unsound. Most of us, too, believe that the application of these doctrines to the problems of contemporary Britain has been extremely misguided and we find ourselves contesting many of the empirical claims made by those in charge. The politicians, in their turn, curl the lip derisively whenever a television interviewer mentions the very word 'sociology' to them. For them, sociologists epitomise, along with education specialists, the 'loony left punditry' which they love to deride, claiming, as Norman Tebbit once put it, that 'the chap in the pub with common sense' knows better.

The Problem of Sociology

The purpose of a special issue like this is to be as informative as possible and so, with apologies to those who already know or think they know, I shall begin by explaining what sociology is about. It is often vaguely identified as the study or science of 'society' - a fairly useless definition. Margaret Thatcher would, I imagine, be surprised to hear that as a sociologist myself, I have absolutely no quarrel with her famous assertion that "There is no such thing as society..."[16] The everyday word 'society' partly describes, partly obscures a set of very familiar experiences we all have and which become more and more puzzling the more we think about them.

The type of experiences I have in mind include the ones we often refer to as being under 'social pressure'. Very diverse examples can be given. We come under social pressure the minute we are born, even beforehand. Social pressure makes us toilet trained, speak, say, English rather than French, answer to a particular name, think of ourselves as male or female, adopt agnosticism, Anglicanism, Islam... and so on. Not all the pressures are immediately obvious ones like parents, families, friends, etc. Some of the most important influences in any upbringing come in fact from dead people. Not just the ones who write books but the ones who through countless actions built a particular way of life: created, say, the Great British Breakfast and 'good manners', or fought for the vote, free education and health provision.

We are often tempted to think of society as a 'thing' because, of course, it so often does seem to have a life of its own. For example, I was brought up fearing the pantheon of gods called 'Times'. My parents married during the Depression. I grew up during the Second World War and after. Would 'Times' be good now the war was over or would they be bad again? 'Times' resembled the weather. Politicians forecasted them rather badly but they couldn't be controlled. On the whole, though, 'Times' did get better while I was young and we had optimism and the Welfare State. Recently 'Times' have been behaving very oddly. A set of regimes which seemed immovable collapsed. Nearer at home the 'welfare consensus' I grew up with collapsed too and people began to talk about Bad Times again. Without the certainties and optimism of my youth I feel changed inside my head. This feeling, however, must be ten times worse for this years graduates who have studied hard in the expectation of a good job and every vacancy heavily oversubscribed. Obviously there is no such thing as society, but there is also no such thing as the self-contained person either - a point Margaret Thatcher was less ready to admit.

Sociology, then, has the extremely difficult task of identifying and explaining 'the forces exerted by people over each other and over themselves' (Elias, 1970), how these forces grow out of individual actions but at the same time constitute the conditions by which individual actions are shaped. Apart from 'society' there isn't a single word to describe all that, though personally, I am very happy to use a term coined by Emil Durkheim, arguably the founder of sociology as an academic discipline, who spoke of the 'collective consciousness'.[17] That makes our work an extension of social psychology where, instead of being concerned with the individual mind, with basic processes of memory, cognition and learning, and so on, we are on a different level of analysis, studying the myriad ways and forms through which minds affect each other.

However, I'm afraid many of my colleagues will already begin to feel they want to get off my bus. Part of the difficulty of introducing the discipline convincingly is that it does not offer a unified cumulative body of theory and research like some others do. Rather like psychology, it is still divided into a number of research traditions or schools of thought'. 'Collective consciousness' is a term some sociologists don't like at all. Indeed, to join the discipline is like trying to join in a rowdy argument already in progress. One can describe fairly precisely what the argument is about but the chances of hearing one voice at a time or predicting how it will be resolved are fairly slim. Indeed the noise seems to be getting worse because the older traditions have split or cross-red with others. New ones are still being invented. This gives plenty of opportunities to charlatans and also to various critics and enemies who want to make the whole thing look like a waste of time. Below, I want to warn about these voices. Sociology isn't a waste of time and we should ask why its critics, especially in politics, are so anxious to do it down.

The main internal argument in sociology, sometimes referred to as the Structure/Action debate, takes for granted that the relative orderliness of society arises unplanned out of the countless actions of individuals but that also the relationship is at the same time a two way one: no person is an island. Given that so-called human 'nature' is not the same everywhere, a point which many non-sociologists find hard to take, the problem is to explain how the two processes fit together. There is a bewildering variety of answers, but in practice, the disunity is a stimulus rather than an obstacle if one spends one's time researching substantive issues - education, say, or race relations, or the family. It would no doubt make my article more readable than it is going to be, in fact, if I spent time describing this work. However, there is a very good book by Gordon Marshall recently published which does the job much better than I could. Anyone who wants to know what research sociologists get up to will probably find it a more user-friendly introduction than the average A-level text (Marshall, 1990). Marshall's point is that sociology has had a much better track record of prediction and analysis over the years than its detractors say.

What I think deserves attention here, not merely because it is fundamental but also because it is topical, is the question of the relationship between sociology and what one writer recently has called 'the curse of common sense'. Common sense told us that the earth was flat, that iron ships could not float and that people could not fly (J. Eatwell Observer, 26 April 1992, p.28). It is the fount of unimaginativeness and it is very British to have common sense. Sociology, I am pleased to say, is rarely common sense but in that case what sort of sense (if any) is it? I apologise if, in answering the question, the discussion gets a little abstruse in places. Despite that, I am going to be talking about something desperately relevant to us all. We are back to Mr Tebbit and the chap in the pub.

Is sociology 'scientific'?

Anyone unfamiliar with the condition of sociology might have expected sociologists to defend themselves from the Chingford Skinhead by claiming that they practice a rational, even scientific academic discipline whose methods and findings, compared with the fumblings of 'common sense', constitute a more dependable form of knowledge which should be correspondingly respected. After all, we respect astronomers' assertions that the earth goes round the sun and not vice versa, despite what the chap in the medieval tavern thought. But no, the claim that sociology should be a science are, in fact, routinely questioned in the discipline itself.

In Britain this internal critique of sociology takes both a philosophical and a political form. The sociological community has, of course, always included a large and diverse group who are skeptical on philosophical grounds about the scientific pretentions of the subject, both here and elsewhere. They tend to share the so-called 'relativist' conviction that objectivity in social research is impossible and that its findings cannot be free of subjective meanings and values. They also argue that the accumulation of factual evidence to arbitrate between different subjective perspectives is out of the question. Far from being scientific 'facts', the findings of empirical sociology merely constitute an extra account or 'story', which is no more or no less a form of knowledge than the 'lay' accounts given by the subjects of the enquiry (including, of course, the chap in the pub). In any case, there are many alternative 'stories' within sociology itself: the failure to accumulate a unified body of theory belies any remaining scientific pretensions sociology may have.

These claims seem to be borne out by the political critique recently mounted by a few members of the profession who have rocked their colleagues with their sudden enthusiasm for free market politics and types of social theory. As they see it, the indifference or hostility of most sociologists to 'neo-liberalism' is not the result of rational conviction at all but the product of an unexamined left-wing consensus in sociology. Even the best British sociological work manifests a bias against capitalism in general and business in particular (Holton and Turner, 1989; Marsland, 1987; Saunders, 1989, 1990). If these writers are to be believed, the attitude of sociologists to politics shapes what they think they 'know', whereas in a social science the reverse should be true: knowledge ought to shape political preferences.

Recently, the political and philosophical attacks have begun to converge, despite their apparent differences in origin. Philosophical 'relativism' in sociology always carried a political message: that accepted truth about society emerges out of clashes of interest and struggles for power, rather than from debate and rational conviction. In the late sixties it acquired a certain radical 'chic' as a stick with which to beat the conservatism of the Anglo-American sociological establishment, some members of which had been caught dressing up Cold War conclusions as value neutral social science and Cold War activities as value neutral research (see for example the collection of essays edited by Colfax and Roach, 1971). So by the time the New Right 'enlightenment' was under way, the weapons by which it attacked sociology were already forged and could be turned against their inventors. In Britain, this moment was symbolised for many of us when Keith Joseph, hitting sociology in a tender spot, demanded that the Social Science Research Council drop the word 'science' from its title. Simultaneously, within the discipline, a new generation of so-called 'post modernist' sociologists began to declare a plague on all houses. Post-modernists claim that the transitoriness and uncertainty of modern life have made it impossible to have any fixed rules about what is rational or what knowledge is. In the words of a recent account, they believe that "The quest for truth is always the establishment of power" (Turner, 1990, p.5). Meanwhile, precisely this maxim was being practiced in British political life as the Government suppressed, massaged or manufactured official statistics on the economy, on education training, unemployment, poverty and so on.

We thus seem to have a disturbing choice. Either British sociology must indeed be corrupt and/or incapable of objective judgement, as the various dissidents inside it imply; or else the convictions and actions of those politicians and academics who disparage the 'rational knowledge' claims of current sociological expertise are themselves demonstrably irrational and dangerous.

Confessions of a GP sociologist

Despite all this I want to defend the unfashionable idea that sociology should be, indeed substantially is, a rational, objective and empirical activity, to which the term science can legitimately be applied. And I want especially to highlight the consequences of rejecting such a project for the discipline. My theme really does have considerable practical significance for what kind of politics and society we will have in future. The developments within and without sociology which I have described suggest to me an alarming, possibly growing undercurrent of Unreason, which touches more than the internal troubles of the British sociology profession. Of course, people will quite properly go on arguing about the precise philosophical grounds on which sociological method rests. But to throw out the very idea of a scientific sociology is to provide an entry for ignorance and extremism.

In saying this I do not write as a professional philosopher of social theory but as what I sometimes call a 'GP sociologist'. Much of my career has been spent in the front line where sociology meets the lay world: researching empirical matters relating to employment and education; teaching introductory sociology to a heterogeneous bunch of undergraduate and adult students; and as co-author of an introductory textbook that has apparently reached a fairly wide readership (Lee and Newby, 1983). All of these 'lay' groups - research contacts, new students, new readers - very reasonably share the same difficulty. They want to be told exactly why they ought to take sociology seriously.

The days have long since gone when in reply we could simply blind them with philosophy or admit, with proud embarrassment, that sociologists themselves do not take it seriously, ho, ho, ho. As the post-Thatcher generation becomes adult, the doctrines one used merely to read about in the library have become the ground rules and assumptions of everyday life, especially in Essex. In their first sociology seminar more and more new students tell me that life is a struggle for the survival of the fittest and competition is always benign in its effects. Capitalism has brought technical progress and universal affluence so class doesn't exist any more. If people are poor or unemployed it is their own fault. The Welfare State made people lazy and trade unions were responsible for our current economic woes. Above all, private enterprise always gives the most efficient service. Taxes spent on the Health Service will simply go to immigrants. These statements are treated as self-evident 'common sense'. If I think otherwise it is because I am tiresomely left wing not because sociology is or will ever be 'scientific'.

To justify the challenge which sociology offers to a whole range of such taken for granted ideas is a difficult task in part because I myself do not think that current sociological research and teaching is as rigorous or as free from suppressed prejudices of both the right and left, as it might be. However, we do not conclude from the beastly behaviour of certain footballers that football itself is a game without rules. Similarly doing 'sociology' is not necessarily the same as 'what sociologists do'. It is up to my colleagues to defend for themselves each individual piece of work they carry out. My main concern here is to suggest that the general scientific aspirations of sociological method are possible and desirable.

We are, of course, too easily seduced by a particular view of scientific knowledge - the so-called 'positivist' conception - which identifies science with certainty (Keat and Urry, 1982, Ch. 1). To possess this certainty, it is said, knowledge must take the form of an agreed body of theory expressed as objective general laws; these laws, in turn, must have been established through the detached observation of 'facts'. I am certainly not renewing the case for some new kind of positivism here, for the positivist picture of how science actually works is no longer recognisable even in a discipline like physics. Although natural science has given rise to the modern technological outlook, in which knowledge is judged by whether it 'works', even much of that is speculative and uncertain and we are coming to understand the tragic uncertainty of a technology that appears to 'work' in the short term at the price of destroying the future. Fundamental science itself however, is constantly making yesterday's certainties into today's uncertainties and the more we know about ourselves and our relation to nature the more we become aware of what we do not, indeed can never know. As far as the social world is concerned, certainty is what is offered by dogma and blind faith, not by reason or science. In so far as people accept any of the latter without question, their beliefs may not, in the end, be wrong but they are certainly irrational. Scientific knowledge, then, cannot be equated with certainty.

To associate 'science' with universal 'laws' and incontrovertible facts is also extremely misleading as well as limiting, for by no means all of the 'proper' sciences exhibit these features. The controversies in medical research over the causes of heart disease, which are more like empirical sociology than experimental physics are a case in point. Yet medical research is generally considered to be' scientific. Some sciences, too, such as astronomy or geology deal with unique phenomena that have to be studied in terms of their particular history. Indeed, historical studies rather than physics offers a better paradigm for the scientific aspirations of the sociologist. (I am prepared to argue, though historians might shudder, that sociology is a branch of history).

Contrary to positivist doctrine, then, I believe that whatever advantages scientific procedures possess actually depend on the systematic use of *un*certainty. Once this is recognised, the supposed objections to scientific sociology become arguments in its favour.

1. Being objective and being certain

Can there really be objectivity in the study of social relationships? As I have myself already argued, society is not an observable object but a psychic complex of subjective interests, viewpoints, perspectives and meanings. From this, relativists infer that scientific detachment is impossible in sociology. After all, sociologists themselves are part of society and have their own beliefs and values which motivate their research and contaminate their findings.

The implications of this need thinking about. If it were strictly the case that the subjective behaviour and experiences of others could not be studied objectively, it would be very difficult to see how, even on a mundane level, we could understand' each other and co-operate or communicate at all. Everyone would be locked into a private subjective world from which there would be no escape and it would be impossible for me to understand what any one else was doing. Human life would be solitary not essentially social as it in fact is.

In any case one should not talk about 'subjective' meanings without examining the nature of 'subjectivity' a little further. There is actually no such thing as wholly subjective thought and action because we all use concepts and language which we have learned from others. Without them one could not even monitor one's own behaviour, still less 'think'. What is more, the very possibility of having a perspective of one's own which can be described as different from that of others presupposes concepts and meanings which act as a common or shared reference point for comparing different outlooks. Thus, as Durkheim observed, a concept is not my concept but collective and impersonal. In that sense a concept is not subjective but objective. In the end, too, it must reflect some of the reality of life around us and with the aid of reason it is often possible to work out some aspects of what that reality is like. Beyond the private ideas of the individual, then "there is a world of absolute ideas according to which he (sic) must shape his own..." (Durkheim, 1976, 437).

I think we can go further than that, though. Arguably, the most basic of the concepts we learn from society are the notions of error and falsehood, which is, to quote Durkheim again, "the first intuition of the realm of the truth" (ibid). Personal and daily life revolves around the possibility of independent truth on one hand and mistakes and lies on the other. I am not of course claiming that in practice we always find it either easy or possible to reach 'the truth'; still less that there is some kind of incontrovertible or 'absolute' Truth. On the contrary, the pages of philosophical debate about positivism have convinced most people that progress in knowledge consists of eliminating false beliefs rather than in 'proving' particular statements to be immutably certain and true. Proof in that sense is never possible. Truth is not, in fact, an object or a content of a belief at all but an attribute of how we have arrived at it. It makes perfectly good, objective sense to distinguish what Brecht, in a memorable phrase called 'telling the truth as we find it', from lies, propaganda, sales talk, what we read in the Sun and so on. The distinction of the false from the true in this sense, is essential for routine dealings with others and for a host of practical decisions. The chap in the pub needs the truth every time he buys a round and is given change. He also expects the 'account' to be consistent and logical and suspects the barman's motives or sanity if it is not. Why should sociology be different? We do not have to suspend everyday notions of truth and logic simply because what we are checking is a page of unemployment statistics rather than the bill for some drinks.

If truth and logic are common sense, however, common sense does not always make use of them. When we check a bill it makes sense to be skeptical about its truth and accuracy. But in many important areas of everyday life, including love, politics and religion, people do not keep up a skeptical rational attitude to their beliefs. Somehow we are very willing to take many things on trust because we think them 'common sense' or want to believe what we are told. Disciplined scientific study, however, entails being skeptical all the time, building systematic uncertainty into the knowledge gathering process, whatever is under investigation. Of course, when sociology asks people to put their cherished beliefs about society and their fellow human beings 'on hold' in this way it cannot expect to be popular. But that is not a good reason for saying that sociology cannot be objective in principle.

2. Established facts or objective evidence?

It can also be argued, however, that objectivity requires 'established facts' if we are to arbitrate between alternative beliefs. In sociology we do not have such facts because, unlike the natural world, the social world cannot be directly observed. The raw material of what sociology studies is not social behaviour itself but its description. These descriptions might be peoples' own accounts of 'what is (or was) going on' or they might be official statistics and other administrative fact-gatherers' accounts. Failing either of these, sociologists produce their own descriptive raw material through their reports on participant observation, through surveys and so on. But there can never be direct observation of the 'facts' of social behaviour itself because all of these materials are interpretations which impose a meaning on what is 'observed'.

The most celebrated discussion of 'social facts' in sociology is Durkheim's Rules of Sociological Method which for years has been pilloried as the manifesto of arch-positivism in sociology. However, Durkheim specifically rejected the fashionable positivism of his time (1964, xl) and arguably, the procedures he commended, though often ambiguous, were a great deal more subtle and fertile than generally acknowledged.[18] Of course, in so far as Durkheim really was talking about observing social facts he was on dangerous ground. An 'established fact' is as impossible as an 'incontrovertible truth'. No science works with facts but with information and evidence of varying quality, which is quite a different matter. Even in natural science we cannot just 'observe the facts': the content of information is relative to the observer's situation and is the product of interpretation. Descartes' famous illustration of this is still one of the best: at certain times of the year the sun looks as if it is bigger than at other times. But Durkheim himself wrote that "observation is suspect until it is confirmed by reason" (Durkheim, quoted in Gane, 1988, p.133-4).

Admittedly, Durkheim's position is full of tensions which still beset us and we should not seek to minimise the difficulties which the scientific interpretation of social facts faces. However, once again, the situation is one with which everyone is already familiar. Descriptions, rather than facts are the raw material on which a great deal of everyday decision taking is successfully based. We are all quite used to the idea that accounts are 'subjectively valid' in the sense that they have a meaning that is valid to the author of the description - as, for example, when the barman, perhaps in all sincerity swears I gave him a fiver, not a tenner; when a man tells his wife he loves her; or when government politicians talk of economic recovery. We do not, however, immediately conclude that all such descriptions are equally complete, still less correct. Correct description implies a rational relationship between the description itself and the evidence (not fact) given by independent experience. Someone can describe to the manager how they saw me give the barman a tenner; the wife can find a letter from the husband's mistress; we can check the politician's use of statistics or find out too late that the party we voted for was wrong about an economic recovery after all.

It is worth reminding ourselves too, that many descriptions that are perfectly valid from the subjective viewpoint of the individual can also be described as incorrect from the subjective viewpoint of the individual. The barman's belief that it is easy to cheat customers may soon result in his getting the sack. The erroneous belief that an economic recovery is under way may nonetheless reinforce political support for economic policies that are guaranteed to ensure that recovery cannot happen. Beliefs that a charismatic leader offers the solution to a nation's problems can lead to the very opposite: enormous suffering and humiliation for its people in total war. In short, there is scope for treachery in many types of social dealings. Surely, then, the fact that sociology's raw material consists of descriptions enhances rather than lessens the case for seeking independent objectively valid evidence?

The point is a commonplace of legal procedure. Indeed, doing empirical sociology is not altogether unlike the way crimes are supposed to be solved. Detectives should be trained to treat all statements and clues, not as 'facts' but as 'evidence': that is equally suspect descriptions which need to be systematically cross checked. Moreover, in order to convict a suspect, the court itself requires certain standards of information and argument in the case brought before it. True, as we well know in Britain, detectives and lawyers often cut corners, make mistakes or become corrupt and as a result an innocent person gets convicted. This does not mean we cannot distinguish the rules of evidence and their use from their absence. On the contrary, the exposure of scandals, the fact that it is possible to talk about an incorrect conviction is sincere testimony to our belief in the importance of these rules. Deliberate perversion of standards of objective justice is both the all-too-prevalent hallmark of authoritarian rule and also the reference point of opposition to it.

The methodological problems of evidence in observing social conditions have long been familiar to historians who are faced with the further diffculty that, as E.P. Thompson puts it "You cannot interview tombstones". Furthermore:

'Data' is not just 'out there to be harvested', it is not a finite quantity but rather an organic and infinite growth. Its quantity and quality will depend very considerably on the simple techniques by which it is collected (Macfarlane, 1978, p.22)

Thus in history too, interpretation and fact are by no means independent. However, this must never be taken to mean that historical enquiry cannot be disciplined by the presence or absence of appropriate evidence. It means that to be gathering evidence is itself to be immersed in a process of rational enquiry - of corroboration or contradiction by alternative sources, internal logical coherence, inherent probability and so on. These in turn are subject to the cut and thrust of rational debate. The alternative debate is the history of smears and whitewash, the 'official history' which denies the atrocities and war crimes, leaving a later generation to its sense of betrayal when it discovers the facts of what really happened in their name. Elsewhere, we argued that: "In the end sociology may, like history, offer few certainties and indeed be little more than constructive speculation", nevertheless, to quote Thompson again, "We must reconstruct what we can". Sociology, warts-and-all is better than no sociology at all if we are to develop a real understanding of the 'human condition' (Lee and Newby, 1982, p.343).

Unfortunately, as T.S. Eliot once put it, "human kind cannot bear very much reality" and trouble comes when people prefer the certainties of blind faith rather than the uncertainty of rational enquiry. It is, therefore, worth considering what it means to reject the possibility of objective evidence and empirical research in sociology. My fear as I write this is that in Britain the discipline (for it still is that) is threatened by a descent into unreason from both within and without. Not all devotees of the current fad for 'so-called' post modernism in sociology are crude relativists but as a movement post modernism is openly hostile to sociological research as I have understood it during most of my career. I have colleagues who are prepared to argue that the modern ideal of rationality has offered a false promise and that consequently standards of rationality themselves are not absolute (cf. Smart, 1992, p.181). The sight of these scholars making use of inferential reasoning to defend such a view might be somewhat comic for their position implies that I can 'win' my side of the debate by shooting them all. But alas, such 'solutions' are found all too frequently in real life to make this a laughing matter. What disturbs me about some of the latest writings are the admiring references to authors with Nazi associations: Nietzsche whom the Nazis adapted for their own seizure of the truth on the route to power and Heidegger, a known collaborator (Rockmore, 1992).

In the present political climate, attacks on the very idea of social science strike me as either irresponsible, dangerous or both. Waves of irrational but uncontested 'evidence' impinge on every household through advertising, television and in the majority of newspapers where distortion and opinion are routinely presented as news. The point is not that people are necessarily brainwashed by this material but that only the most muted protest is or can be raised against it. As a result, what post modernist philosophers seek to prove is becoming taken for granted common sense: that all information is equally prejudiced or 'biased'. At the same time, the availability of evidence about the condition of people is under assault and not even a matter of which the people themselves are generally aware. Libraries and universities which act as public storehouses of evidence have been starved of funds. Information about the activities of the state and its agencies has become, at the hands of those elected to protect it, less rigorous in form and more difficult and more expensive to obtain. Only the flimsiest ministerial acknowledgement of the need for independent standards in the gathering of official data has been given (Guardian, 14.12.1991).

If sociologists and other social scientists do not defend the idea of objective enquiry and impartial evidence, who will? Racist beliefs really do not have the same validity as the sociology of racism. Mrs. Thatcher's claims that everyone, even the lowest paid, had benefitted from her economic miracle did not have the same truth value as the rather different carefully documented conclusions of poverty researchers during the eighties (Townsend, 1991). This clash of claim and counter claim was not just power play and subjective meaning. And frankly, much of the 'common sense' talked in the pub during the eighties has become a curse. It was just plain wrong and as a result people are suffering.

3. Lack of unified theory

There is one remaining major objection to the idea of sociology as science, an objection which seems to be rather different from those discussed so far. As I indicated, the discipline is replete with theories and concepts reflecting the ongoing influence of rival 'schools' of sociological thought. This is largely because its history is one of attempting to come to terms with the entirely novel political problems posed by the so-called 'twin revolutions' of modernisation: industrial capitalism in economic life and secularisation and democracy in political life (Giddens, 1971, Introduction). So far-reaching were these problems that the range of new ideologies which evolved in response were obliged to speculate beyond the normative questions of modern politics to the substantive issues of the nature of the social bond itself. The result was the assortment of rival sociologies still found today. Theoretical sectarianism is thus the result of profound differences in political values. The continuing failure wholly to detach sociological theory from its political origins means to many observers that the explanatory project of scientific sociology has failed, not least because it means that there is no body of unified and cumulative theory as in a 'proper' science.

I have a lot of sympathy with this criticism as far as it goes because as Mullins has pointed out recently, a great deal of so-called 'sociological theory' today is not theory at all but a mish-mash of political ideology, intellectual history, critiques, philosophy and taxonomy - especially in Britain (Mullins, 1990). People achieve spectacular careers as sociologists simply on the basis of writing abstract books about other people's abstract books and never, say, having to knock on a door with a questionnaire. 'Theory' has inevitably become a sub-specialism too and the two typically seem to proceed independently. Among other things this sets a bad example to students, who are further encouraged to think that 'anything goes' in sociological analysis. As I see it, the only theory worth considering in sociology is theory developed out of dealing rigorously with an empirical problem and there is rather too little of that at the moment.

Nevertheless, aspiring to develop a wholly unified body of grounded theory in the manner of some of the natural sciences can lean too far in the opposite direction and once more measure the claims of scientific sociology against an inappropriately positivist model of what science is all about. The disunity of theoretical explanations in sociology is in fact another example of what appears to be a weakness but is really a strength. The current overweight of ideology and philosophical critique, is certainly regrettable but controversy between rival theoretical traditions is in itself beneficial because it throws a critical light on the conclusions which individual investigators draw from their findings and it helps to clarify the proper concerns of the discipline.

Furthermore, we cannot assume, like the natural sciences, that what holds in one part of the social world will also hold in another. Of course society is a tissue of incompatible meanings and points of view and this is the only general account that can be given of it. Sociological explanations thus depend on the ability to enter into alternative perceptions which differ from our own. So the object of theory in sociology is not the construction of a body of unified propositions but, on the contrary, to add to the diversity of perspectives available to the discipline to interpret the complexities of the social world. This is not just a question of 'inventing' but the genuine revelation of significant new classes of information. The latest major and long overdue addition to the list of individual sociologies, namely feminist sociology, illustrates this creative aspect of theoretical heterodoxy perfectly. The invisibility of women and of gender differences, even in the sociological research of twenty years ago now seems truly staggering. With the growth of gender research whole new areas of historical and contemporary knowledge have developed. Precisely because they typically have been germinated by some political struggle, then, both old and new schools of theory represents a new 'discovery' in so far as each reveals a new 'meaning' out of all the separate meanings which constitute the social world as it is.

There are two constant dangers, however, in the close link between politics and a social science. The first is that one particular brand of theory will claim a privileged route to the truth. For truth in sociology can only emerge if it remains more than the sum of its various 'isms'. The second danger is that the certainties of some external political outlook will acquire enough power to suppress independent scholarship altogether. Though always around, both of these dangers seemed less remote fifteen years ago than they do now.

Individualism and sociological theory

A huge social experiment has been imposed on British society since 1979 and the neo-liberal 'conviction politicians' who have masterminded it see themselves as having won an intellectual as well as a political argument thereby discrediting a whole range of 'experts' and progressive cognoscenti - among whom sociologists figure prominently. In this section I want to show that this supposed 'achievement' rests on the very objections to a science of society that I have been contesting here. It uses them to deflect social science criticism away from the anti-rational and anti-human elements in the 'free market' panacea.

To accuse free-market liberals of anti-humanism and anti-rationalism may seem rather strange. Liberalism is usually thought of as the arch-champion of freedom and rationalism in the conduct of business and social affairs. In practice, however, even sympathetic critics consider its rationalism to be strictly limited (cf. Barry, 1987, pp.29-31). It's leading philosopher, David Hume, argued that reason can only be the 'slave of passion'. It's conception of reason is thus little more than what Hume's famous friend, Adam Smith, called 'prudence', or enlightened self-interest, the distinguishing 'virtue' of the man of business. Moreover, liberals have always been opposed, admittedly not without some justification, to "the man of system [who] ... seems to imagine that he can arrange the different members of a great society with as much ease as he can arrange the pieces on a chess board ... " (Smith, 1910, emphasis added).

The anti-humanism implicit in classic liberal doctrines is the result of a paradox, namely that considerable authoritarianism is needed to remove political and institutional resistances and establish a supposedly 'unplanned' market order. Once such an order has been established, moreover, people have to accept the impersonal and often capricious rule of what Smith called the 'hidden hand' of the market. The justification given is that an unplanned order will lead to the benefit of society at large even if particular individuals suffer, say, bankruptcy, unemployment, loss of amenity or whatever. Is this any different morally from Stalin sacrificing peoples' lives to 'historical inevitability'?

What is most interesting of all about modern neo-liberal thought, though, is the way it has embraced arguments of the kind criticised in previous sections of this article. This is partly due to a quirk of intellectual history. The ideas of Smith and Hume were a major influence on the neo-classical economics of the so-called Austrian School. The School combined these, however, with certain antipositivist tendencies in Continental philosophy which laid great stress on the limitations and subjectivity of knowledge. The mix of these two tendencies are especially evident in the highly influential work of F.A. Hayek. Though mostly published in the nineteen forties and fifties, Hayek's writings have in turn had an acknowledged impact on the think tanks of the British New Right, on Keith Joseph and Margaret Thatcher, on so-called 'anarcho-capitalists' and on self-styled neo-liberals within the sociology profession itself. Of course, other writers have been extremely influential in this context too, but it would be quite inappropriate, at this stage of my paper, to provide a thoroughgoing sociological critique of all such work and the intellectual and political programme based on it. A few observations about Hayek will, I think, serve to reveal the central point I wish to make.

Hayek was reluctant even to use the term 'social sciences' except with the disinfectant of inverted commas (e.g. 1948, 57). He was especially critical of what he calls 'scientism' which is analogous to what I have referred to as 'positivism', i.e. the slavish imitation of the generalising natural sciences in social theory and research. Now, some of the targets of Hayek's anti-scientism seem to me entirely justified and his description of them as an 'abuse of reason' completely correct. I share his objection to many forms of behaviourist psychology and his hostility to the early positivism of Auguste Comte. Comte, by the way, coined the word sociology but unlike the author of a companion article in this volume, I think Hayek is wrong to think Comte's spirit still lurks around modern sociology. I have no quarrel, however, with Hayek's distrust of the idea of 'social engineering', whether it is carried out by sociologists, other social scientists, or the revolutionary vanguard of the proletariat. Most readers of this journal, I imagine feel the same.

Clearly, then, Hayek was not against the use of reason or science as such. He merely resented their application to social affairs. After all, he had dogmas of his own which he presents as self-evident. So in fighting 'scientism' in the social sciences he unnecessarily restricted their scope and their potential role in policy formation. At the same time he made his own social theory inaccessible to rational or empirical challenge. The result was an extremely seductive and dangerous set of writings that resurrect all those contradictions in nineteenth century liberal thought against which classical sociology successfully struggled.