Young Women’s Empowerment Project

Girls Do What They Have to Do to Survive: Illuminating Methods Used by Girls in the Sex Trade and Street Economy to Fight Back and Heal

A Participatory Action Research Study of Resilience and Resistance

About Young Women’s Empowerment Project

What are the Sex Trade and Street Economies?

This story is important to tell

Impact of the research on the peer researchers and participants

The Research Design and Implementation

Who participated in the analysis?

Findings: Institutional Violence

Breaking Isolation/Creating Community

Tips for building sisterhood in the hood

Things to do with an opiate/heroin overdose using Naloxone

What you need to know about the real lives of girls in the sex trade and street economy:

Research Team

Jazeera Iman: Research Development Coordinator

Naima Paz: Research Intern and cover design

Dominique McKinney: Social Justice Coordinator

Daphnie W: Administrative Support and Graphs

Outreach Workers (2007-2009): Stephany, Precious, Skitlz, Danielle, Amber, Isa, Veronica Bianca, Daphne, Naima, Dominique, Jazeera and Jacque

Girls in Charge—our weekly leadership group of nearly 60 different girls participated in this project between 2007-2009.

The research report was written by Jazeera Iman, Catlin Fullwood, Naima Paz, Daphne W and Shira Hassan

Art work by Young Women’s Empowerment Project Membership

Acknowledgements

Young Women’s Empowerment Project would like to thank Cricket Island Foundation for teaching us how to do Participatory Evaluation Research and for introducing us to Catlin Fullwood. Simply put, without Catlin we would not be who we are as researchers.

YWEP would also like to thank the Crossroads Fund for helping us fund this project.

There are many allies who helped push us in our learning process and supported us along the way: Andrea Ritchie, Cara Page, Adrienne Marie Brown, INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence, Isa Villaflor, Claudine O’Leary, Amber Kutka, Laura Janine Mintz, Ilana Weaver, Xandra Ibarra, Kim Sabo, Johonna R. McCants and Teresa Dulce.

Young Women’s Empowerment Project is especially grateful to our funders: Third Wave Foundation, Cricket Island Foundation, Chicago Foundation for Women, Chicago Community Trust, Polk Brothers Foundation, AIDS Foundation of Chicago, Crossroads Fund, Comer Foundation, The Funding Exchange, Astrea Lesbian Foundation for Justice, Peace Development Fund and Michael Reese Health Trust.

2009 YWEP Leadership

Dominique McKinney, Social Justice Coordinator

Jazeera Iman, Research Development Coordinator

Cindy Ibarra, Communications Coordinator

Shira Hassan, Co Director

Naima Paz, Research Intern

Stephany C, Outreach Intern

Precious M, Girls in Charge Intern

Daphne W, Communications Intern

YWEP Board

Laura Janine Mintz, Natalie D. Smith, Tanuja Jagernauth, Lara S. Brooks, Teresa Dulce, Xandra Ibarra and Adrienne Marie Brown

Dedication

This research is dedicated to all girls, including transgender girls, and young women, including trans women who do what they have to do to survive every day. The world may call us victims—but we know differently—we know we are our own heroines. This work is personal to us—it is about our lives.

“If you have come to help me you are wasting your time. But if you recognize that your liberation and mine are bound up together, then let us walk together.”

—Lila Watson

Youth Activist Summary

This research is for US. It’s for YOU and for all girls, including transgender girls, and young women, including trans women involved in the sex trade and street economy.

This research study was created by girls, collected by girls, and analyzed by girls.

We did this because this is OUR LIVES. Who knows us better than us?

We did this to prove that we care—that we are capable of resisting violence in a multitude of ways. We take care of ourselves and heal in whatever way feels best for us—whether society approves of it or not.

This research study honors all of the ways we fight back (resistance) and our healing (resilience) methods.

We proved that we do face violence but we are not purely victims. We are survivors. We can take care of ourselves and we know what we need.

This research is a response to all of those researchers, doctors, government officials, social workers, therapists, journalists, foster care workers and every other adult who said we were too messed up or that we needed to be saved from ourselves.

The next time someone tells you that you don’t know what’s best for you, look towards our tool kit for inspiration. We wrote the tool kit with the intent of giving you ideas about how girls have survived this life—not to tell you what to do.

We did this. We did the research. And now we are sharing it with you so that you know that girls do what they have to do to survive.

About Young Women’s Empowerment Project

The Young Women’s Empowerment Project was founded by a collective of radical feminists and harm reductionists. In 1998, as a group of young women and girls with lived experience in the sex trade and street economy and our allies, we began doing activism and talking through what we believed about the root causes of the sex trade. We wanted to create an activist organization (not a social service) that would give girls a chance to learn the leadership skills necessary to change the conversation and play an active role in the dialogue about our lives.

Our goal is to build a movement amongst girls, including transgender girls, and young women, including trans women who trade sex for money, are trafficked or pimped and who are actively or formerly involved in the street economy. We are activists, artists, mothers, teachers, and visionaries—our vision for social justice is a world where we can be all of these things, all the time.

Over the last three years, Young Women’s Empowerment Project has reached over 2,000 girls involved in the sex trade through our peer to peer outreach and an additional 105 through our syringe exchange. We have also done presentations, workshops, and offered assistance to nearly 3,000 adults working with youth involved in the sex trade. We have been focusing on building our internal leadership so that young people who begin as members can move up our leadership ladder and become a part of our executive team as Co Directors.

Calling All Street Youth

Reproductive Justice Speak Out for All Street Youth in Chicago!

Come speak your mind about sexual violence, dealing with doctors & sex, hormones, birth control & more!

When: Friday April 18th 2008

Time: 6pm to 8pm

Who: For & By All Street Youth

*This means if you identify as being youth under 25, are homeless, drug-user, queer, couch surfing, disabled, LGBTQAA(TSI), feminist, activist, artist, punk rocker, raver, clubber, rioter, exotic dancer, militant fighter, trader, writer, slam poet, dreamer, racer, tagger, juggalo, juggalette, vagabond, guitarist, lyricist, rapper, YOC—Youth of Color, GOC—Girls of Color, GWC—Girls with Children, freestyler, button-maker, anarchists, or just plain surviving thru the day-2-day hustle n flow of our struggle… This Can B Ur day 2 SpeakOut!!!

Where: UIC Latino Cultural Center

Lecture Center B2

Enter Through 750 S. Halsted

***we will have signs posted up with arrows pointing you in the right direction cause once you enter 750 S. Halsted, the Student Center East building, you have to go through this building to get to the Latino Cultural Center (LCC) which is basically one lecture center down to your right

It is our duty to fight for our people

It is our duty to win.

We must love each other & protect each other

We have nothing to lose but our chains.

—Assata Shakur

Co sponsored by: The Broadway Youth Center, Street Level Youth Media, Young Women’s Action Team, Chicago Abortion Fund, Chicago Women’s Health Center, [?] & UnSilenced Woman Press, Radio [?], Illinois Caucus for Adolescent Health, Latinas Organizing for Reproductive Equality, Empowered Fe Fes, MrSA[?], Feminists United, UIC Gender and Women’s Studies, Chicago Girls Coalition, Women and Girls Collective Action Network & Third Wave Foundation.

What are the Sex Trade and Street Economies?

To us, the sex trade is an umbrella term that describes any way that we can exchange our sex or sexuality for money, gifts, drugs, or survival needs.

Sometimes, this can be by choice but we can also be forced into the sex trade by someone else. There are many ways that girls can be involved in the sex trade and we believe that our experiences, though all uniquely different, are united by the way we experience the intersections of misogyny, racism, classism, transphobia and homophobia.

YWEP defines the sex trade as any form of being sexual (or the idea of being sexual) in exchange for money, gifts, safety, drugs, hormones or survival needs like housing, food, clothes, or immigration and documentation—whether we get to keep the money/goods/service or someone else profits from these acts. The girls that we know have a wide range of experiences in the sex trade. Some of us have been forced to participate, some of us have chosen to participate in the sex trade, some of us have had both kinds of experiences. Others feel that the question of choice is irrelevant or more complicated than choice/no choice.

Regardless of what people think about choice, what we know is that real girls are really trading sex for money. Right now. At YWEP we seek to build community among girls who have been forced and/or trafficked, who trade sex for survival, who choose to participate in the sex trade on their own terms, and every reality in between. We never use the word “prostitute” because we are concerned with the entire range of the sex trade (not just the illegal part) and because this word is a label that dehumanizes us and make us into “those other girls.” Likewise, we don’t use the term “sex worker” because it doesn’t include the experience of girls who have been forced into the sex trade and who don’t relate to the term “work” to describe their experiences.

The street economy is any way that girls make cash money without paying taxes or having to show identification. Sometimes this means the sex trade. But other times it means braiding hair, babysitting, selling CDs/DVDs, drugs or other skills like sewing and laundry.

We say street economies because there is more than one kind of economy playing out on our street at any given time. These economies are complicated and a part of the lives of the membership and outreach contacts of Young Women’s Empowerment Project.

Social justice for girls and young women in the sex trade means having the power to make all of the decisions about our own bodies and lives without policing, punishment, or violence. Our community is often represented as a “problem” that needs to be solved or we are portrayed as victims that need to be saved by someone else. We recognize that girls have knowledge and expertise in matters relating to our own lives that no one else will have. We are not the problem—we are the solution.

Young Women’s Empowerment Project is like a political organization in that we try really hard to create unity and power among girls and help them to navigate hostile systems and life crises. We provide training to providers about what girls need and how girls should be treated when trying to access systems and services. When leaving isn’t an option or what a girl might want, YWEP is here to encourage and facilitate safety planning, harm reduction ideas, and offer support and resources. Unlike programs that focus on exiting the sex trade—which usually exclude girls who aren’t ready, able, or wanting to exit—YWEP meets girls where they are and helps them make the next steps they choose. Empowerment means that girls are in charge of their decisions and have power over what they want to do—even if that means something different than what adults think is safe or appropriate. YWEP believes that the more often girls are in charge of the choices in their lives—whether that choice is about food, sleep, relationships, housing or the sex trade—the more power they take in their lives as a whole. We celebrate every decision girls make and honor all of our choices.

Who are we?

Young Women’s Empowerment Project is made up of girls, including transgender girls, and young women, including trans women ages 12-23 who have current or past experience with any part of the sex trade and street economies. We are 99% girls and women of color. Most of us are African American, Latina and Mixed Race. About 70% of our constituency also identifies as Lesbian, Gay or Bisexual. Transgender girls represent approximately 20% of our constituency. We are led by our membership through weekly leadership meetings where girls make important decisions about our programming. We have nearly 60 members across Chicago. Of these 60 members, about 15-20 of us regularly participate in weekly meetings at YWEP. Our leadership is made up of our membership and is responsible for the daily running of our organization.

Many of us are undocumented, have been incarcerated/detained, and/or are current or former drug users. At any given point, roughly 85% of our membership and leadership are homeless or precariously housed. We estimate that nearly 25% of us have completed high school or gotten our GEDs. Another 5% of us have taken college classes or gone to trade schools. During 2009, the number of our girls accessing our syringe exchange tripled. We now have 85 girls per month receiving clean works (including hormone needles) from our outreach workers.

Our Guiding Principles

Self Care: Self care means taking care of your body, mind and spirit whenever and however you can. It means checking in with yourself in a regular way to see how you are doing with your job, your relationships, your health and your overall well being. We know what is best for our bodies and how to take care of ourselves. We practice self care at YWEP by providing food, as well as clothes at the clothing exchange, practicing aromatherapy, and encouraging ourselves as well as others to take “self care time” (time away from YWEP work to take care of our needs).

Empowerment Model: We believe that girls are experts in their own lives. We value youth leadership and work to create it as much as possible in our space. We don’t tell girls what to do, we don’t give advice, and adults don’t take control of youth-led projects. We create as many opportunities as possible for girls to be in leadership positions and adults DO NOT do all of the important work and DO NOT make all of the important decisions. Being empowered means that girls are active in the decisions they make about their lives. We believe that a girl is capable of being a leader as soon as she comes into our project. A girl can come to YWEP and immediately take leadership, no matter where she is at in her life. One of the immediate ways a girl can take leadership is in GIC (Girls in Charge), our weekly leadership group where girls learn political education, work on projects to benefit YWEP, and make decisions that directly impact how YWEP is run.

Harm Reduction: Harm reduction means any positive change. We do not force anyone to stop participating in any risky behavior. Instead, we work with them to come up with options that work for them to stay safer when engaging in that risky behavior. We apply this to the sex trade, but also to any other high risk behavior as well. Harm reduction means practical options, no judgment, and we respect choices that girls make.

Popular Education: is a way of talking about ideas that helps to get people thinking critically about things so that they can act together as a community to address inequalities and injustices. At YWEP we strive to expand our knowledge about each other and about the stories of social justice movements. For example, our stories about our experiences in foster care might sound like someone else’s story too. When we share our stories, we can find common ground to begin to work together to resist and fight back.

Social Justice: At YWEP we bring social justice into our work by acknowledging and supporting resistance. We encourage girls to look closely at the way things like racism, classism, sexism, transphobia and homophobia play out and affect girls involved in the sex trade and street economy. We understand that the sex trade is not about one person, but about a system of things that all work together to oppress women, people of color, lesbian and transgender people, and others too.

Our Work

Young Women’s Empowerment Project is a member based social justice project for girls and young women ages 12-23 who have current or past experience in the sex trade and street economy. Our mission is to offer safe, respectful, free-of-judgment spaces for girls impacted by the sex trade and street economy to recognize their hopes, dreams, and desires.

The goal of our work is to build a movement of girls with life history in the sex trade and street economy. To do this, we consciously engage in political education and leadership development as holistic themes for our work.

Young women at YWEP run our programs. In addition to running and supporting our office three days per week, YWEP also conducts three weekly meetings for outreach, Girls in Charge, and social justice teams. YWEP staff and members also provide popular education workshops all over the country.

Girls in Charge: Girls in Charge is the leadership group that makes all of the major decisions at YWEP. Girls receive stipends to make leadership decisions about our project, learn political education, and create materials valuable to the project and other young women impacted by the sex trade (such as guides, fliers, trainings, etc.). GIC created zines about drug harm reduction and sex trade harm reduction, as well as a training that teaches social workers about how to positively interact with youth in the sex trade. GIC also completed a political education training course, where girls learned about systems of power and oppression and the ways that this affects young women of color in the sex trade.

Outreach work: Girls at our project go through a 48-hour training over 8 weeks to learn how to reach out to and support other girls in the sex trade. Girls learn about sex trade safety and harm reduction, female reproductive health, reproductive justice, drugs and drug harm reduction, legal rights. We also learn more outreach skills, such as active listening, supportiveness, and practicing good boundaries. Upon completion of this training, girls reach out to girls and young women in the sex trade. Outreach workers attend a weekly outreach worker group. Outreach Group is a place for girls to discuss any issues that came up during the outreach session, as well as trade information and support each other. Our outreach workers reach 500 girls per year and an additional 85 or more through our syringe exchange each month.

Popular education trainings: Popular education is more than making sure that everyone participates in workshops. Activists for decades have been using 12 popular education practice to work together as educators and learners to open up problems and ask critical questions like: Who benefits, why is it this way and what can be done to change the systems that affect us? Our workshops on the sex trade with girls offer practical information on myths and realities of the sex trade. We are engaged in a process with young people across the city to question why the sex trade exists, why girls are involved, and what can be done about it.

Our skill building workshops offer training to girls inside our project to improve their knowledge and ability to take on leadership. We also offer workshops to organizations and collaboratives that want to improve their ability to work with girls and young women impacted by the sex trade.

Social Justice and Transformative Justice: At YWEP we value the rebellion of girls impacted by the system. We offer education and support to girls so that they can begin to unpack what social justice means to women and girls involved in the sex trade. To some girls, this might mean working for rights, to other girls this might mean working to abolish the sex trade, and to other girls it might mean both.

One way that we incorporate social justice into our daily work is by working to build community. We do this by helping girls find connections with each other, by looking closely at how we might play out sexism (like by calling girls “ho’s”) and by creating a respectful, free of judgment space where girls can get information about how to change the world.

We believe that social justice and empowerment go hand and hand. Empowered girls who are active in their own lives are making social change just by being in charge of their choices and destiny.

Transformative justice is a model that acknowledges that state systems and social services can and often do create harm in the lives of girls. Transformative Justice supports community-based efforts for social justice beyond the government or other state-sponsored institutions. This means that we do not work on making new laws or policies because we don’t believe that the law can bring fast and positive change to ALL girls in our community. Instead of following models for social change that talk about us without including us, we seek to create a movement for social justice that recognizes and honors our talents as leaders and innovators with us at the forefront.

At YWEP we work together to come up with our own alternatives to shelters, housing, violence and support that do not continue to mire us in the system but instead make change that we can sustain and sustains us.

Our Research

YWEP began our first experience with Participatory Evaluation Research in 2006. With a grant through the Cricket Island Foundation’s Capacity Building Initiative, we met Catlin Fullwood, an activist, researcher, and trainer. Catlin taught us a research method in which all members of the community could be involved in the development, data collection, and analysis of the research.

Our 2006 research project had three learning questions. We wanted to find out (1) what effect harm reduction was having on our outreach contacts. We also wanted to find out (2) who our allies were and weren’t as a harm reduction-based, youth-led social justice project. Lastly, (3) we wanted to learn more about how girls respond to other girls in positions of leadership. For this research project, we did a literature review, several focus groups with YWEP leadership and membership, and we collected over 300 surveys from our outreach contacts across Chicago and Illinois.

2006 Research Findings

Finding 1: As a result of our study, we realized that sometimes girls don’t believe that people like us can be leaders. This is when we began to look closer at how internalized racism, sexism and colonialism play a role in our organization and in our lives. This led us to work more on developing our solidarity with each other. Through retreats, team building exercises, sister healing circles and developing an internal analysis, we worked—and continue to work—to achieve our goal of building solidarity and leadership as a whole with our youth membership.

Finding 2: One key component we learned through our research was the effect of harm reduction in the lives of our girls. We learned that girls who have been with us for a year or more, whether that be through outreach, or through more direct involvement in the project or YWEP activities, incorporated harm reduction in all aspects of their lives. Not only did these young women apply the principles of harm reduction to the sex trade and staying safe, they applied it to many other aspects of their lives, from safer drug use to eating habits.

Finding 3: We figured out that our allies were people who recognized our abilities to be leaders no matter what our present or past involvement in the sex trade may be. We also realized that our allies were people or organizations who believed in our ability to achieve empowerment and who were willing to work outside of mainstream systems to support us in our goals. We discovered that, for YWEP, being an ally means recognizing that girls work hard every day to live the life they have.

During the 2006 research study, YWEP saw girls and young women in the sex trade and street economy making positive changes in their lives, fighting back against multiple harms, and finding innovative ways to bounce back and/or heal. While we saw violence happening, we also saw that girls were surviving every day and getting stronger and smarter all the time. The 2006 findings prompted us to take a closer look at how girls were resisting and bouncing back from violence. We became determined to find studies done on/about girls involved in the sex trade that purely focused on our survival. We discovered a gap in the research. Every study we found showed us as powerless.

Why we started this research

We do not deny the fact that girls in the sex trade face violence. We decided that we would do this research to show that we are not just objects that violence happens to—but that we are active participants in fighting back and bouncing back. We wanted to move away from the one-dimensional view of girls in the sex trade as only victims to look at all aspects of the situation: violence, our response to the violence, how we fight back and heal on a daily basis. We want to build our community by figuring out how we can and do fight back collectively and the role of resilience in keeping girls strong enough to resist.

We want to show that girls in the sex trade face harm from both individuals and institutions. Nearly all the research we could find about girls in the sex trade only looks at individual violence. Many people seem to think that more institutions or social service systems is the solution. YWEP agrees that institutions can be helpful at times, but we also wanted to show the reality that we face: every day girls are denied access to systems due to participation in the sex trade, being drug users, being lesbian, gay or transgender or being undocumented. We know institutions and social services can and do cause harm in our lives. We present this research to show that the systems that claim to help girls are also causing harm. We want to show that girls in the sex trade are fighting back and healing on their own—within their communities and without relying upon systems.

We also wanted to show how girls in the sex trade fight back against the institutional violence they experience so we could share what working. With the data we collected, we discovered that girls face as much institutional violence (like from police or DCFS) as they do individual violence (like from parents, pimps, or boyfriends).

We wanted to show how girls bounce back and heal from individual and institutional violence. We wanted this information so that we can collectively build a social justice campaign to respond to broad systemic harm.

From this, YWEP’s first youth developed, led, and analyzed research project was born.

The Learning Questions

A learning question is a question that helps us learn and explore more about a specific topic. A learning question can’t be answered purely by data collectionists also about the process and analysis of the entire research project. Learning questions are never just quantitative. They always must be qualitative as well.

YWEP met for three months in weekly research meetings to discuss what topics we wanted to include in our research. We thought about what impacted us and our constituency. We thought about what the goals of this research would be and how we wanted it to impact us. We knew that research was a powerful tool and we wanted to use it bring us together and build community. This is why we decided to use the research to shape our social justice campaign.

We looked at all the existing research we could find about girls in the sex trade and didn’t feel our truth represented. We spoke to YWEP outreach workers and Girls in Charge Members and noticed themes about how we were fighting back and healing. We brainstormed all of these topics and themes and we color coded all the patterns until we had a visual representation.

To develop the learning questions further we brainstormed all possible questions we could ask. Some questions we asked were “How do girls work the system,” “how do girls heal from daily violence” and “how can girls support each other.” We narrowed the questions down slowly.

From this collective process the following learning questions were decided:

-

What kinds of institutional and individual violence are girls in the sex trade experiencing?

-

How are they resistant to this violence?

-

How are they resilient to this violence?

-

How can we unite and fight back?

We agreed on these questions because we wanted to bring out how girls in the sex trade take care of themselves without relying on systems—without someone else deciding what is best for us.

We also chose these questions as a way of uniting our community. This research is kind of a “toolkit” that shows how girls rely on each other as opposed to systems. This is about more than just studies or findings. This is about girls uniting. Our data shows girls ideas about how to be resistant and resilient—how to continue taking care of themselves and community and how to add new methods to their self care.

This story is important to tell

Resilience and resistance-focused research shows girls that we can and do fight back. It shows girls in the sex trade from an empowering perspective. We want to show that we are capable of helping ourselves without relying on the systems that sometimes harm and oppress us.

We want to honor all of the traditional and non-traditional ways girls are taking care of themselves and healing from violence. We are survivors. We find our own unique and individual ways to fight back, whether violent or non-violent. We resist. We also heal. We find ways to take care of ourselves in order to continue our struggle, whether those ways are traditional or non-traditional.

This research is unique because it does not just focus on individual violence in our community. It is also unique because it is the only study that we know of that was developed and conducted by girls ages 12-23 in the sex trade and street economy. We are able to tell our story from the inside.

Preparing for the Research

Getting ourselves ready to do this project was a big deal. We started meeting to talk about the research ideas about 6 months before we started collecting the data. We tried at least three versions of all the tools we used (the tools are attached at the back of the report) because we would try them out on each other first. If someone was uncomfortable or didn’t like any part of the tool we would start again until we were all on the same page.

Early in the data collection process we realized that the research was going to be super deep and sometimes a bit sad and overwhelming. The girls who were in charge of collecting and coding the data had to read lots of different stories that were both painful and uplifting. We decided to always check in with each other as we were reviewing the data, to do sister circles and healing circles, to take breaks while we were working with it, to use sage and aromatherapy to help us stay clear and honor every story we read. We observed that we were using resilience methods even while we were doing the research.

Why qualitative research?

Qualitative data describes quality, the properties of something, or how something is. If we are talking about fruit, some qualitative information would be: the apple is green. It has a small rotten spot near the stem.

Quantitative data often describes how many or how much. Quantitative information about fruit would be: there are two apples and one orange on the table.

Our data is more qualitative because for us the “how and the why” is more important than the “how many.” We are looking to show something that can not be measured in numbers. Our research is complex, and could not be reduced to counting how many times a girl was resistant. We need to know how the girl was resistant. How else could we share ideas and empowerment? It is impossible to talk about how we heal with numbers. It is impossible to share how we avoid violence with quantitative data. Our research is more than just numbers or data. It is our personal stories about ourselves, our lives.

Data collection methods

We had four data collection methods:

-

Because our outreach workers reach 500 girls per year, we added four questions to the outreach worker booklet because we wanted to reach girls that did not come to YWEP’s offices. Since this was an ethnographic observation tool, meaning that the outreach worker was writing about what her contact was experiencing, we felt that this was a good space for questions about violence. In our experience, we found that girls had difficulty talking or writing about violence they experienced. This was an opportunity to explore the kinds of violence girls were experiencing without having them actually have to write about it themselves.

-

Our popular education workshops involve hundreds of girls every year. Girls talk about violence young women in the sex trade experience in our popular education workshops. This was another way to reach a different set of girls. We looked back at the 2007 workshop notes from participants who wrote down anything having to do with violence, resilience, or resistance. We also added a question to the 2008 workshops about violence. We did not ask anyone to talk about their own individual experiences with violence, we asked about violence girls in the sex trade experience collectively. We also asked how girls in the sex trade collectively fight back against violence. Girls wrote the answers to these questions down anonymously on large poster paper. Later, we collected their answers and coded them.

-

We created “Girls Fight Back” journals, a purely resilience and resistance focused fill-in-the-blank style zine for girls to write about ways that they fought back and healed. We wanted this data collection tool to focus on resistance and resilience because the girls would be filling it out themselves and talking about individual violence experiences can be triggering. We also wanted to make sure that we were getting information about resilience and resistance not pertaining to violence. The “Girls Fight Back” journal could be used as a healing and empowering tool. We heard many times from girls who filled it out that they never thought about what they did before they used the zine. Many girls filled the zines out multiple times because they found the process of writing in them healing. Outreach workers, Girls In Charge members and outreach contacts all filed out this journal.

-

The last data collection method we used was focus groups. We did two focus groups in Outreach Group and two in Girls in Charge. The focus groups allowed us to explore more deeply what was talked about in the Girls Fight Back Journal and Outreach Booklets. It also allowed girls to talk about ideas that were not put on paper. The latter of the two focus groups looked at how we could collectively unite when practicing resilience or resistance. It also looked at themes that came up in the data we had already collected. This served to give us ideas for possible social justice campaigns. Focus groups were not open to the public, but were especially for our outreach workers and members only.

Impact of the research on the peer researchers and participants

Working so closely with other people’s truths and experiences has really proven how important the community that YWEP is creating helps with the survival and healing of our constituency. Working so closely together during the research development, data collection, and analysis gave peer researchers an opportunity to shape the research into something they really cared about. It shows that we can and will have a voice when the subject matter is our lives. It was empowering to do research on a topic close to us, as well as to have the results be accurate to our truths.

Participants got to take part in a research study in an empowering and positive way. They got to talk about how they fought back. This research was our collective work. Many issues that girls were facing were being talked about in YWEP, but breaking down common issues through research was extremely important so we could get a clearer view of the issues. We could see that some issues affected all of us, and some issues affected just some of us. The process of doing the research ourselves was also important because we knew that we were going to get the story right. In the past, researchers have come in to YWEP and asked us for information about our lives. We would share the same stories over and over and we would still be shocked when we read their reports. No matter what we said to the researchers, their reports always said the same thing: we were victims who needed police and social workers to save us.

Doing research ourselves helped us to say “No” to outside researchers. From this process we came to consensus that we will not work with any other researchers unless they share our values as allies.

Doing this research was empowering because it shows that girls in the sex trade do care about our lives. It promotes a sense of community. We care about fighting back. We care about helping each other and we have each other’s back.

The Research Design and Implementation

YWEP decided to have one main person be the contact person for all questions and thoughts about the research. Jazeera Iman made sure that Research Groups were meeting regularly and stayed in contact with our professional research consultant, Catlin Fullwood. She was also responsible for making sure that all of our data methods were being carried out as we stated in our plan and that the data was kept confidential. Jazeera also co-led us through our development, implementation and analysis of the research. Our research intern, Naima Paz, assisted with focus group co-facilitation, did our typing, culling and coding and also attended and supported all our research meetings. Daphnie, our communications intern, helped with typing and created graphs. She also helped coordinate the research releases.

We began implementing the data collection tools in January 2008 and stopped in February 2009.

Before we even began collecting new data we looked at the data we already had from our 2007 popular education workshops. Each year, YWEP does workshops with girls in group homes, drop-ins, shelters and foster care settings. We also do workshops at conferences and meetings. YWEP has careful records of the questions asked and discussed during our workshops because the participants always write their answers down on big flipchart paper. We were able to go through our notes and identify what girls were saying about violence and resilience and resistance without being prompted. This was very helpful because we were able to see the thoughts girls were having about these subjects. We used this information as the starting off point for our focus groups.

We asked questions about the violence girls are facing. We also asked ways that girls in the sex trade are resistant or resilient. The flipchart paper asking about violence always had many answers. However, the question asking about resistance always had very few answers. We realized this was because girls were doing things to take care of themselves that they didn’t identify as resilience or resistance. This is why we started using the words “fight back” and “heal” because those words made more sense to our constituency. We had many conversations outside of focus groups about the different things girls do to take care of themselves. The researchers kept an open mind so that we could track all the ways girls were fighting back and healing.

We started off with focus groups to get people thinking about things. Then we added the questions to the outreach booklet. Next we started collecting the “Girls Fight Back” Journal. We ended our data collection with a final round of focus groups to make sure that everyone had a final chance to add something.

Because the research process was so long, girls came in and out of the process. A core group of researchers came every Thursday at 3pm for the research meeting. We regularly had 3-4 participants in the meeting and sometimes we had as many as 10 girls coming to our research meetings.

Phase 1—Focus Groups

The first focus group was conducted by Jazeera Iman. We developed the focus group questions during our research meeting together. We then offered stipends to our weekly membership group to participate in the discussion. All of the focus group members were between the ages of 14-21. Of the ten girls, six were African American while the remaining four were Latina. This focus group was 45 minutes long. We talked about ways girls were experiencing institutional and individual violence in our communities.

The second focus group was during Outreach Group. This focus group was also facilitated by Jazeera Iman. A total of eight outreach workers attended this group. Of the eight outreach workers five were African American and two were Latina.

This group asked the outreach workers to observe the violence their outreach contacts were experiencing and also asked questions about how girls were bouncing back and fighting back against that violence.

Outreach Questions Added

Once we completed the two focus groups, we added four questions to our outreach booklet (our outreach booklet is attached at the back of this book). We created the questions during our weekly research meeting and with the outreach workers too. The four questions we asked were:

-

Is your contact experiencing one-on-one violence “Individual Violence” like being beat up, raped, girl on girl violence or fighting, gang violence, or hate crimes? For example your contact got beat up by a white person and she is a girl of color, or a girl got beat up by guys (or girls) for being in the sex trade. These are just a few examples, but there are many more. Please describe in detail:

-

Is your contact experiencing violence from an authority or establishment? This doesn’t necessarily mean physical violence. It can be emotional (mental) sexual, verbal, financial, or anything else. This can mean racial or gender discrimination by a school or clinic, or social service facility, lack of resources or care from DCFS, clinics, rehab or any other establishment. These are a few examples; we need you to find more.

-

How has your contact been resilient to violence? (Bounced back or healed from the violence like through meditation, therapy, journaling, talking to other girls, medicinal drug use, self harm, or any other way imaginable a girl can help herself feel better.)

-

How has she been resistant to violence? (Fighting back—this doesn’t necessarily mean physically fighting back. It can mean any way of resisting violence, like always making sure to walk in a group when coming home late at night, leaving her pimp, trading sex for money with people you know are safe, or meeting with other girls to learn legal rights when dealing with the police.) Please be as detailed as possible, and make sure to specify if it is resistance or resilience.

Each week, our outreach workers answered these questions about their outreach contacts and gave the answers to our researchers. We collected this information between March 2008 and February 2009. All of the information was kept in a folder and every week during our research meeting we would look at the new typed data and talk about how we could code the answers we were getting.

Girls Fight Back Journal

After we had been collecting data from our outreach workers for six months, we began distributing and collecting the Girls Fight Back Journal. This journal is a fill in the blank style zine that we made together during our research meeting. Before we implemented the Journal, we tested it in one of our weekly membership meetings. We had to make several versions of the Girls Fight Back Journal before we felt satisfied that the tool was respectful, empowering and asked the right questions.

We handed out the Girls Fight Back Journal to all of our membership, outreach workers and any young woman who came to our space. Our outreach workers filled them out themselves and also had their outreach contacts fill them out. We also had a few Journals come back to us by way of service providers in the Chicago Area who had received copies of the Journal from outreach workers. We collected 107 Girls Fight Back Journals between August 2008 and February 2009. We typed the responses up and reviewed the data each week to see if we could find themes in what we were seeing. We talked about our observations each week in our research meeting too.

Phase II—Focus Groups

The goals of both of these focus groups were to ask questions about what we were seeing in the written data from the Girls Fight Back Journal and the outreach booklet. We also wanted to ask bigger picture questions about how we could unite girls to fight back together against the violence we are experiencing.

Our first focus group had 14 girls and took place during our weekly membership meeting. Of the fourteen girls who attended, nine were African American, two were Latina and three were Mixed Race.

The group was an hour and a half. First we talked about the resilience and resistance methods girls were using to respond to individual violence. Next we talked about the resilience and resistance methods girls were using to confront institutional violence.

In the final phase of the focus group, girls discussed how the current resilience and resistance methods they were using could be applied to our social justice campaign. We also looked closely at the topics girls were identifying as potential targets of our campaign based on the information we were getting about institutional violence.

Who Participated

We had three groups of respondents

-

Girls who were a part of YWEP who come to our offices regularly

-

Girls who are outreach contacts who may or may not come to the space

-

Girls who got a “Girls Fight Back” Journal from a YWEP member or a service provider who was giving them out. We chose to reach these three groups because we wanted to hear from as many girls as possible.

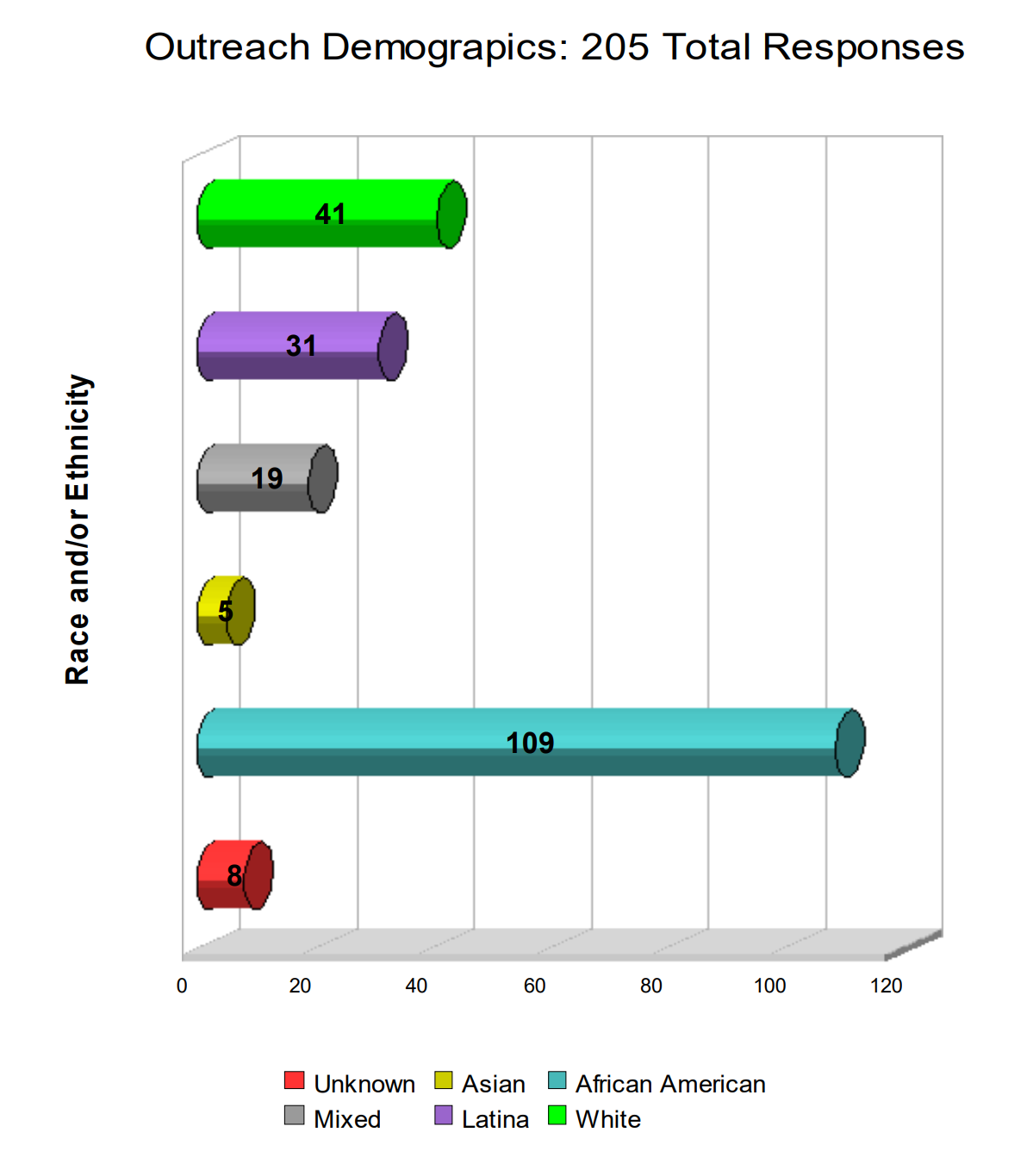

These graphs show exactly who responded to our questions from our outreach booklet and from our Girls Fight Back Journal. YWEP chose to allow girls to respond multiple times in both our outreach and Girls Fight Back Journal. Therefore we don’t know the exact number of girls we spoke with (although we know we spoke with over 120 girls).

This demographic information is based on the number of total responses and is a combined number for both our Outreach and the Girls Fight Back Journal.

Other demographic data we collected showed that 18 responses were from transgender girls, while 44 responses were from pregnant girls with another 52 responses coming from girls who said they were mothers. Finally, 54 responses were from homeless girls.

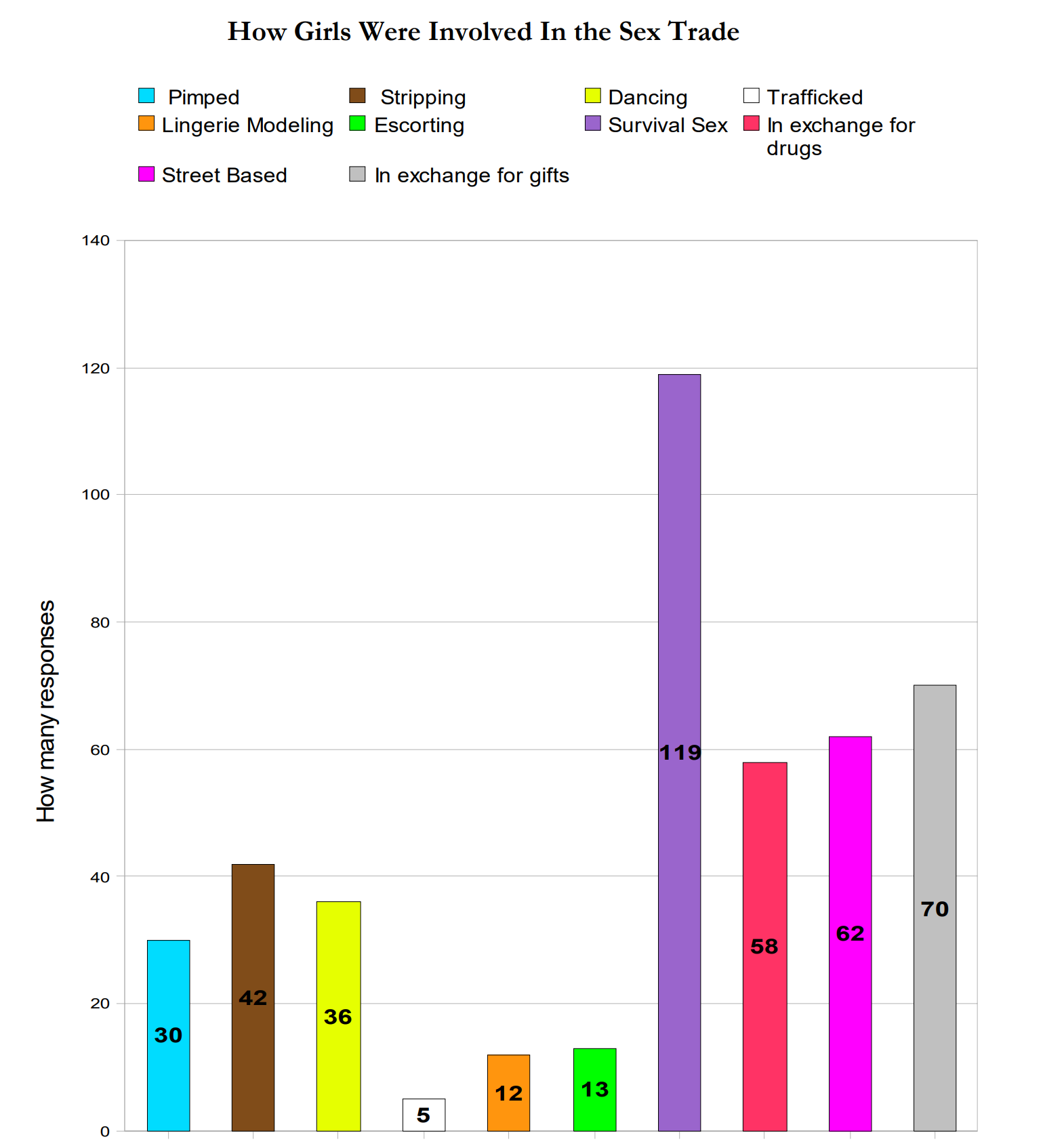

All girls we spoke to were involved in the sex trade and street economy. The chart below shows how girls who responded were involved.

Analysis

We were overwhelmed and amazed by the amount of data we collected.

Once we had all the data together and typed up (which took two months or more!) we asked Catlin Fullwood to meet with us regularly to help us make sense of all the information. Every Thursday we would meet and look at the findings. We made categories so that we could code the data. After the coding, we wrote a narrative for each code. For example, if the code was “harm reduction” we would find all the examples of harm reduction in the data. Next we would write a few paragraphs using the respondent’s words.

After we had written narrative paragraphs for every code we had four meetings that focused entirely on understanding the data. We had nearly 10 people in each meeting. We all read the narratives very carefully. Next we identified themes and categories that we saw coming out of the data. We called these categories a “set of findings.” Once we had a set of findings, we reflected on the information and asked ourselves these questions:

-

What is the most important thing(s) that I learn about girls and resistance and resilience from this set of findings?

-

Did I have an “AhHa” moment while I was reviewing it? If so, what was it?

-

What surprised you about this set of findings?

-

Are there contradictions in this set of findings? If so, what are they and why do you think they exist?

-

What do you want to make sure that young women and others reading about this research will understand about the real lives of young women in the sex trade?

Who participated in the analysis?

Our analysis group consisted of our youth staff, as well as youth membership, interns, outreach workers and girls in charge members. Our adult staff attended some meetings too.

In groups of two, we reviewed our set of findings and answered each question and wrote our answers down. When we came back together to share what we wrote we typed everything up and sat with the data for a few weeks.

After we had all read and re read the answers and reflections we had a debate. We used the data to prove our points and have a discussion about the findings.

Once we completely discussed our findings, debated our thoughts and wrote everything down, we agreed on the findings identified below.

Findings Section: Overview

As a part of the research conducted by YWEP to better understand the ways in which girls in the sex trade “fight back” or resist violence, it was necessary to define all the ways that they experience violence—at the individual and institutional levels. As the researchers recounted the forms of violence experienced by girls—from the data collected in the “fighting back” journals, from the outreach workers’ booklets, and from the focus groups, as well as from the experiences of the researchers themselves—the question of how girls who suffer so much trauma can be resilient enough to resist kept coming up. The phrase “resilience as a stepping stone for resistance” resonated for all.

We realized also that there is a universality to the experience of girls in the sex trade that mirror the experiences of all poor women. As young women of color involved in the sex trade, we are being oppressed on multiple levels. We are female, of color, involved in the sex trade, poor—the limitation of choices and access, mistreatment and neglect by “helping systems,” police surveillance and abuse of power, partner abuse, sexual abuse and exploitation, family violence and economic disenfranchisement. They are also young girls, many of color, so racism and ageism are ever present factors in how they are treated—in addition to being in the sex trade. Girls also identify their sexual orientation and gender identification along a broad spectrum including lesbian and transgender as well as bisexual or heterosexual. Homophobia is an additional factor that defines how the world sees and treats them—in addition to being in the sex trade.

In examining the data sets, we found the threads of violence and trauma throughout. But these girls don’t see themselves or want to be seen as victims. They are survivors of violence and they resist the systems of oppression that define their lives, and use their own methods of resiliency. The more they resist by standing up for themselves with police or service providers—getting to know their rights—the more resilient they become in all aspects of their lives. And the more they engage in self care and harm reduction and building support networks—the more they are able to resist the violence that permeates their lives.

Findings: Individual Violence

The predominant stories of individual violence told by the girls involved boyfriends, johns, pimps, family members, foster care families.

-

There were recurrent themes of sexual abuse in the forms of gang rapes by johns, being raped and trafficked at a young age, being raped and exploited by pimps, and being stalked and raped by johns. These girls identify trauma that has resulted from these experiences of sexual violence.

-

The theme of control and manipulation was related to pimps and boyfriends who would withhold financial resources necessary for the girls and for their children. Threats of having their children taken away were used to control them and keep them in line.

-

Physical violence is a reality in girls’ lives—perpetrated by boyfriends, pimps and johns. Most often it goes unreported for fear of further violence and based on a belief that the police will not believe them and will, in fact, blame them for the violence they experience. The beatings they experience are also a threat to their children, further cutting off access to help.

-

Girls also report violence by other girls—not so much in terms of direct physical violence, but being involved in girl on girl hating that at times leads to isolated fights between girls.

Findings: Institutional Violence

The individual violence that girls experience is enhanced by the institutional violence that they experience from systems and services. The violence included emotional and verbal abuse as well as exclusion from, or mistreatment by, services. Traditional places of safety and protection are not available to them.

-

Girls are denied help from systems such as DCFS, police and the legal system, hospitals, shelters, and drug treatment programs because of their involvement in the sex trade, because they are trans girls or because they are queer, because they are young, because they are homeless, and because they use drugs. “Girls in the sex trade face exclusion and neglect when accessing shelter and other services.”

-

There are particularly a lot of examples of police violence, coercion, and refusal to help. Police often accuse girls in the sex trade of lying or don’t believe them when they turn to the police for help. Many girls said that police sexual misconduct happens frequently while they are being arrested or questioned. One journal respondent wrote “Girls recognize that they need advocates when dealing with these systems, whether it is from their peers, or a trusted adult.” Stories about police abuse outnumbered the stories of abuse by other systems by far. In the words of a youth researcher, “Girls need advocacy when dealing with institutions and public services.”

-

Abuse in foster care is both systemic and personal—as girls reported being physically and emotionally abused by foster parents and being threatened that DCFS will take their children away.

-

Pimps also present an institutional threat because they are organized, and have weapons and bodyguards who watch girls. This sense of omnipotence is part of the psychological abuse that pimps use to keep girls afraid. Whether they are an institutional force or not, they are certainly perceived to be by the girls under their control.

-

We were surprised by the number of girls who are being denied help from various institutions who claimed to be for, and to help, girls in the sex trade. Some examples of institutions denying girls help are police, hospitals, and especially social service agencies.

Findings: Resistance

Resistance for the purposes of this research has been defined as the means and the methods used by girls to “fight back.” It has many meanings and applications by girls who experience individual and institutional violence. It can mean avoiding violence by taking another way home or educating herself and another girl about her rights in dealing with the police. There are creative ways of engaging in self-protection that are not judged here—from finding good places to hide your stash when being harassed by the police to “getting over” on a system that refuses to help you. All of these acts of resistance are critical and meaningful for these girls. It gives them a feeling of power in a culture that wants to keep them powerless.

Harm Reduction

Harm reduction is one of the primary tenets of YWEP program work. It is not just about harm reduction in terms of drug use or safer sexual practices. It applies to all aspects of girls’ lives and how they negotiate an unsafe world and keep themselves physically, emotionally and spiritually intact. Girls use harm reduction to safety plan and stay safe. Girls talked about practicing it in all areas of their lives, from creating safety plans, to avoiding violence, to safer drug use. A YWEP member looking at the data concluded, “Girls apply harm reduction to their lives broadly to reduce harm in multiple areas.”

Girls also talked about self care as a form of harm reduction. Soothing self care helps girls recharge, and find the strength and energy to continue practicing resilience and resistance in their lives. One girl stated, “They think we don’t take care of us, but girls use baths, showers, aromatherapy, and journal writing as ways to soothe.” When systems completely fail them, girls use harm reduction strategies to get what they need. “Hospitals are discriminating against girls for being in the sex trade and not giving full care.” On the other hand, some girls talk about using harm reduction to make systems work for them. “Girls talk about carefully choosing what information to share and what not to.” We were surprised to find that girls use harm reduction as a transformative justice approach—relying upon each other for the help that the institutions claimed to provide but did not.

Girls talk about safety planning as a way of relying upon each other to keep safe when working in the sex trade. Girls also report that they are learning alternative medicine, and how to take care of their bodies without the aid of medical practitioners. Girls talk about turning to each other for shelter/safe housing instead of relying on institutions.

Girls also use harm reduction with themselves to work on not judging themselves and letting go of self hate. An example of this would be a girl in the sex trade showing herself love by taking a bath at a friend’s and treating herself to a good meal.

Speaking Out/Standing Up

Whether it’s “knowing your rights,” speaking up with authority figures, using the legal system to fight back, or participating in a dyke march, girls in the sex trade take direct action on their own behalf or on behalf of others. Girls resist institutions by insisting on making their case despite the threat of repercussions. As one girl wrote in her Girls Fight Back Journal, “I resisted by fighting the court case and appealing the school’s decision (to expel her), by proving them wrong and not letting them underestimate me.” Girls teach each other their “street law rights,” One girl cautioned that “you can still be arrested for using drugs or having sex with a cop even if the cop consented.” Another girl reported that “he told me he would let me go if I gave him some, but then he still took me down to the station.” Some girls use the system for their benefit, such as putting a restraining order against an abuser, or using the legal/judicial system to press charges against someone. One girl talked about reporting her pimp to the sex trade in order to be free of him. “I called the police and told them I was being forced into the sex trade.”

A lot of girls talk about having to fight against the systems, like DCFS or the legal system. “Laws or not there’s ways around it.” Girls talk about having to fight the cops to prove themselves right. When girls do try to use systems like the police to stop the violence they are experiencing, they are often made to feel like liars or provocateurs. When they are the victims of sexual violence they find themselves having to prove that they were raped. One respondent wrote “I took the police with me to the hospital after they called me a liar, and had doctors look at me so I could prove them wrong.”

Girls also talk about fighting for their rights. One girl’s journal stated, “DCFS tried to keep my daughter from me, and I wouldn’t let them.” And another girl wrote in her journal, “I fought the police system, because I wouldn’t let them send me to jail for murder, when it was in self defense.” Sometimes just the act of speaking up is an act of resistance as one girl told us, “don’t be afraid to use your voice, it’s your strongest weapon.”

Building Critical Awareness

A very important thing that is happening is girls are gaining Critical Awareness. This critical awareness means that girls are realizing that they are not to blame for institutional violence and are looking at the bigger picture, and realizing the need for advocacy when dealing with systems and the role that institutional oppression plays in what they are going through. Girls are practicing critical awareness by examining patterns in their lives, as one YWEP researcher concluded: “Girls are learning that it’s a whole system of oppression, not just their fault that bad happens.”

Developing critical awareness also helps girls find their greatest resources—one another. YWEP researchers defined Breaking Isolation involved “talking to someone you trust.” YWEP researchers concluded that “Thinking about change is an important change in itself.” When they do not allow themselves to be turned against one another, they can build collective power as a group. Girls talked about the importance of having “someone to watch your back” as a protective factor in their lives. As they become increasingly aware of their shared struggles, it becomes less important to be separate because of race or sexual orientation or what aspect of the sex trade you’re involved in. We may be from different backgrounds, but we share a lot of similarities. What is critical is that girls share the violence and challenges that define their lives and that creating solidarity and collective wisdom with other girls is the greatest act of resistance.

Findings: Resilience

Resilience, for the purpose of this study, refers to ways to bounce back or heal whether they be conventional or unconventional. Some forms of resilience are personally soothing like aromatherapy, medicinal drug use, bubble baths, or food. Other forms are about connection—hanging out with girlfriends, reading books about the movement, or educating younger girls about how to protect themselves.

Empowering Self Care

Girls are empowering themselves with self care by educating themselves on other radical women and activists and survivors. Sometimes girls work to become educated on any subject they feel good and empowered about. Girls are doing things to physically stay empowered in their bodies such as yoga, running, dancing for fun and other exercises. Some girls are writing in journals and diaries as a way to take care of themselves. Some girls are using projects such as making their own clothes or singing to feel empowered. Many girls also found it empowering to take care of their children every day. Girls are also working hard to embrace their bodies as they are and reject racist and misogynist media messages.

Soothing Self Care

Many girls are making an attempt to find things that they find soothing to comfort themselves with when dealing with fatigue, anxiety or stress. Girls are using different methods to physically comfort their bodies; some of the ones that are common are baths, meditation, aromatherapy, and using other drugs to help relax and soothe their bodies like weed, drinking and other medicinal drugs.

Some girls are finding it soothing to be around friends or family that feels safe to them, which seems to bring comfort because of a break in isolation and seems to bring normalcy to their lives. Some are also using religion and talking with God. Some are simply giving themselves the chance to zone out and do mindless activities like watching TV and playing video games or listening to music. Girls are also using reading a book as a soothing way to take care of themselves.

Aromatherapy is used very commonly and also in very different forms. Some girls are burning incense, sage and candles and some girls are using the smell of baby wash they like, weed or foods that smell soothing.

Some girls also find cutting or injuring themselves as a soothing form of self care. This led us at YWEP to re name what some people call “self injury or self mutilation.” We now call it “Self Harm Resilience.” We call it this because so many girls who filled out the Girls Fight Back Journal said that using controlled self injury was a practice that they said was an important form of coping. Girls said that they weren’t doing this to hurt, they wrote they were doing it to feel better. Many girls wrote stories of body modification, like giving themselves and their friends tattoos and piercings. Respondents talked about reclaiming their body through body modification. “Body modification can mean body autonomy to girls” according to one journal writer. Other girls wrote about more complicated forms of self harm resilience like breaking bones or making cuts or burns on their skin. Rather than judge this as “bad” or “dangerous,” we decided to use harm reduction as a way to understand this. We respect that girls wrote these stories of self harm resilience in the section of our journal that asked “how do you heal or take care of yourself.”

It’s important to remember that everyone uses Self Harm Resilience for different reasons. For example, Self Harm Resilience was identified as a way for girls to be in control of their own bodies. One girl talked about self harm resilience as being empowering because she was hurting herself as opposed to someone else hurting her. Self Harm Resilience can be a way to prevent or come out of disassociation. Some girls said that it can be a way to deal with being triggered because it draws you back into your body and into the present moment.

Girls talk about soothing self care as something that they have control of, and feel good about making the attempt to soothe themselves in big or even small ways. Girls also talked about self care as a form of harm reduction. Soothing self care helps girls recharge, and find the strength and energy to continue practicing resilience and resistance in their lives. After reviewing the data from this section one YWEP researcher noted “They think we don’t take care of ourselves, but girls use baths, showers, aromatherapy, writing as a way to soothe.”

Breaking Isolation/Creating Community

Girls are also reaching out to other girls in the sex trade to break isolation. Girls in the sex trade get peer to peer support, especially around the issues or sexual assault or survivorship.

It is a misconception that all girls in the sex trade dislike each other and do not reach out to each other for support. In this data set, we found many examples of girls in the sex trade reaching out to each other for support, friendship, and safety. Girls identify turning to their peers as a form of self care. Girls talk about turning to each other as a support system, as well as networking with each other for education and self care. One YWEP researcher observed, “She breaks isolation by talking to a girl she trusts.”

However, girls also talk about experiencing girl on girl violence, such as stealing, talking badly about each other, physically fighting, and setting each other up. Although these things seem contradictory, they are both true in a culture fraught with contradictions about protecting children, yet sexually exploiting them. There is more conversation about girls as violent predators, but little about their incredible loyalty and ethic in their efforts to be there for one another.

Surprises in the Data

When we were reviewing the data a few points struck us over and over again. First, we were surprised how many stories we heard from girls, including transgender girls, and young women, including trans women about their violent experiences at non profits and with service providers. This was upsetting because adults and social workers often tell us that seeking services will improve our lives. Yet when we do the systems set up to help us actually can make things worse. This was clear when looking at the foster care system. We heard many stories about how foster care settings would deny girls privileges like bus fare or clothing. This left girls to find their own ways to replace those items. This is a cycle of violence that begins with the institution—not with the girls.

We were also surprised by how often police refused us help, didn’t believe us, or forced us to trade sex to avoid arrest and then arrested us anyway. Health care providers were also identified by girls as being unethical. We heard many stories from girls going to the emergency room or to a doctor and being placed in psychiatric units just because they were in the sex trade, transgender or were thought to be self injuring.

There were times when we were all blown away and stunned into silence while reading the extreme and impressive measures girls took to protect themselves, their children and their community. It is absolutely a myth that girls in the sex trade do not take care of themselves or other girls in their neighborhood. It is also a myth that the violence we experience prevents us from being leaders or making positive changes in our lives. We saw over and over again that girls are excited and inspired about making changes and practicing self care. We have now have proof that unconventional resilience methods are a stepping stone to resistance.

Behaviors that have often been condemned by greater society, such as self harm or drug use, are ways that girls in the sex trade take care of themselves, and therefore, build their resilience and resistant to violence.

Trans Girls

One area of our research that needs improvement for next time is that our methods did not track whether or not the violence transgender girls were experiencing was different or the same as non transgender girls.

We did notice three trends that were specific to trans girls’ experience of violence:

-

Girls had trouble in school often because teachers were transphobic and allowed classmates to harass them and teachers/administration participated in harassment.

-

Non profits that were specifically for the gay and lesbian community were discriminatory against transgender girls who were there to get help or participate in programming.

-

Health care providers and shelters are not doing a good job of working with trans girls. We face stigma, confusion on the part of service providers and violence when trying to find help taking care of our bodies.

As YWEP continues our research, we will be more clear in our questions so that we can be sure to identify the specific experiences of violence transgender girls are experiencing.

Thoughts and Recommendations:

After doing all of this research, we came up with a few recommendations for others to think about.

-

Resilience is a stepping stone to resistance. Meaning, when we take care of ourselves we generate the power to fight back. Our recommendation is that we give girls as many opportunities as possible to take care, that we believe that all girls do want to take care, and that we don’t judge the way girls take care of themselves, their children and their community.

-

Understand that the sex trade is much easier to get into than it is to get out of and that we all have unique and valuable ways of soothing and fighting back.

-

Encourage and respect girls’ right to think for themselves—even if it’s different than what adults think is OK. Empowerment means taking control of our choices—every girl has the power, even if it’s in the smallest ways—to make a decision that can positively affect our lives.

-

If you run a non-profit organization, think about having NO police or security guards on site. Girls involved in the sex trade are targets for unethical law enforcement and will be less likely to confide in your staff if they think you are working with the law. Furthermore, we heard a number of stories of security guards who worked at social services soliciting sex, sexually harassing girls, or being homophobic and transphobic towards girls. These cases do not seem to be specific to certain officers or guards or social services. We believe this problem is happening to girls all over Chicago.

-

Be aware that young women who identify as lesbian or queer may be involved in the sex trade and have sexual contact with men. LGBT programs need comprehensive pregnancy prevention programs, too.

-

Any program that is open to girls needs to be open to transgender girls.

-

Trans girls need information about taking care of their bodies when they can’t get to a doctor or clinic. YWEP is working to develop a tool that we can share with girls in our outreach and also with other service providers so that we can all do self exams on our own terms.

-

Think critically about the law before advocating for a policy. Will the law really help girls trading sex for money right now? Or will it just lead to an increase in police presence? Will removing a law decrease girls’ risk for violence or abuse?

-

Allow girls to seek medical care without an ID, without payment and without risk of being turned over to the police or foster care.

-

Harm Reduction is a philosophy that girls need access to. Learn Harm Reduction. Teach Harm Reduction. Practice Harm Reduction.

YWEP’s Next Steps:

Young Women’s Empowerment Project will be taking steps as a result of this research. Our goal is to launch a social justice campaign that will solidify the movement we have been striving to build in Chicago among girls involved in the sex trade and street economy.

We have five objectives:

1) We will distribute the tool kit we made, describing methods other girls in the sex trade have used to be resilient or resistant that comes directly from these research findings.

2) We want to hold a formal press release for adults and youth, detailing our findings and conclusions. This release will also give people a chance to use the data to figure out how girls in their communities are resilient and resistant to violence and how they can unite.

3) We will launch a social justice campaign based on the research findings. This campaign will be led by the Youth Activist Krew at YWEP and will have the support of our allies across Chicago and the country.

4) We will make more health options available to girls who are a part of YWEP. We want to do this in three ways:

-

We will train our outreach workers to have more knowledge about women’s health and transgender health through developing a relationship with a women’s health clinic that is queer and trans-friendly.

-

We want to invite allies who practice alternative medicine and acupuncture to provide regular information and care so that our constituency can access holistic health care without ID, money or fear of judgment related to the sex trade or drug use.

-

With the help of a health-based resource, we will develop a guide for self exams for cis girls and trans girls. This guide will help girls know their bodies, know how to take care of their bodies and identify when they should go to the doctor if needed.

5) We will address violence and police misconduct, as well as other bad encounters from social service agencies in our community by using the YWEP BAD ENCOUNTER LINE to track violent men, including police. We also hope that this tool will track how girls are fighting back so that we can continue to share resilience and resistance methods with our girls.

Our social justice campaign

We will use this information to pinpoint the violent issues that girls in the sex trade face the most. We will also look at ways that the youth fought back. Our focus groups, as well as in the Girls Fight Back journals, explored possible campaign ideas. Our latest focus group examined which of our campaign ideas was the most possible and the steps we need to take to turn the idea into action. Creating our Social Justice Campaign has had a lot of steps:

-

Our social justice coordinator launched a political education curriculum to train our membership.

-

We formed a new activist group called YAK (youth activist krew) that is meeting every week to work on our building our campaign.

-

We invited folks from Rukus and Detroit Summer to come for a weekend to school us about building a campaign from our research findings.

-

We are hosting a Youth Activist Camp for the YAK members to go more in depth about becoming activists and creating our campaign in January 2010.

We have already completed the first three goals on this list. We have also begun our first action using this research. Our action is to create a Bad Encounters Line. This is a tracking tool that any girl, including transgender girls, and young women, including trans women involved in the sex trade and street economies can use to report a discriminatory experience with any system or individual. For example, girls can report an experience with a dangerous man soliciting sex or report a hospital who is refusing them care. By September 24th, 2009 we will have collected 75 responses from our constituency. These responses will help us become clear about a target for our campaign because we will learn what specific service providers, precincts, wards and neighborhoods are most affected by institutional violence.