Reinhard Müller

In Search of Freedom and Self-Determination

A Tour Through the Anarchist Movements in Graz, Austria, 1918–1938

The Graz “Federation of Libertarian Socialists” (B.h.S.)

Bund der Kriegsdienstgegner, Graz Branch of War Resisters International

The Bartošek/Bartoschek Brothers

The End of the Federation of Libertarian Socialists (B.h.S.): The Sterilization Trial

Reorientation and Reorganizations Attempts

The Underground Groups of Steflitsch and Leeb: “Bread and Freedom” and “Light”

What is Anarchism?

Few ideas are so permanently faced by prejudices as Anarchism. Even today, political circles and a remarkable part of the mass media spread the image of chaotic, bomb throwing Anarchists. Members of every political, religious, and many social movements have used violent means, including Anarchism. But as the English philosopher Bertrand Russel said in 1918, “[if Anarchists] use bombs, it is as Governments use bombs, for purposes of war: but for every bomb manufactured by an Anarchist, many millions are manufactured by Governments, and for every man killed by Anarchist violence, many millions are killed by the violence of States.”[1]

It is no secret that Anarchists, particularly at the end of the 19th century, carried out assassinations, and that Anarchists during the Spanish Civil War resorted to using means of violence in the fight against fascism. But Anarchists have also brought to life radical nonviolent movements, that even deny themselves the right of self-defense.

In the same vein there is a second misunderstanding to clear up. Anarchism is often understood as an ideological system, or at least a unified, enshrined world view. In fact it deals with a diversity of social, economic and philosophical imaginations unified by only one thing: the goal of Anarchy. “In place of the dominance of people over people steps in the self-organization of autonomous personalities, who have fully realized their human potentials.”[2] The way to a society without a state, without parties, without mandatory associations, without Churches, without institutionalized law has, from an Anarchist perspective, many different paths. There should, in fact, be a co-existence of socially and economically differently organized societies. The points of unity: no dominance of people over other people, federativism and decentralization, self-organization and voluntary agreement, harmony between human and nature. With this in mind one should really talk about “Anarchisms” or “anarchistic movements,” and this diversity plays out fully in the example of the City of Graz.

“Prehistory”[3]

The so-called modern Anarchism was, in Austria, a child of the Labor Movement. In the late 1880s Anarchists fought hard alongside Social Democrats, radical Marxists, and Social Revolutionaries. The end of this brotherhood, problematic from the start, came in May 1887 when the Master Tailor Johann Rismann (Grabe/Grabendorf, Austria-Hungary, later Slovenia, 1864 – Graz 1936) initiated the group “Autonomists,” the first autonomous anarchist group in Austria. This was the basis of the Austria-wide anarchist movement the “Independent Socialists” starting in 1892, with centers in Vienna, Graz, Linz, and Klagenfurt.[4] One member from 1893 was the then-bakers assistant Vinzenz Muchitsch (Lenart v Slovenskih goricah/St. Leonhard in Windischbüheln, Austria-Hungary, 1873 – Mitterlaßnitz [zu Nestelbach bei Graz], Austria, 1942]. Muchitsch shifted to a Social Democrat following an 1896 prison sentence and later became the mayor of Graz. December 1893 in Graz witnessed the sensational High Treason trial against Johann Rismann, the bakers assistant August Krčal (Polná/Polna, Austria-Hungary, later Czech Republic, 1860 – Graz, Austria 1894)[5] and the typesetter Ferdinant Barth (Peggau, Austria 1862 – Vienna, Austria 1913). The defendants were let free but the trial led to the end of the “Independent Socialists” in Graz.

But before that, two important institutions had been founded that over the following decades would be central homes of the Graz anarchists. The first was the “First Styrian Workers-Bakery” (Erste steiermärkische Arbeiter-Bäckerei, reg. Gen. m. b. H.) in Eggenberg Nr. 82 (today Graz, Eggenberger Allee 30, relocated in 1903 to Eckertstraße 55). It was founded on November 27, 1892 by the then chairman of the anarchist-influenced “Union of Styrian Bakery Workers” (Gewerkschaft der Bäckerarbeiter Steiermarks). More importantly was the “Worker Education and Aid Society” (Arbeiter-Bildungs- und Unterstützungs-Verein) founded later, on July 19, 1893. Within this frame, the journal “Freedom. Socialist Organ” (Die Freheit. Socialistisches Organ) was also founded on April 5, 1894. Soon afterwards it was prohibited by the authorities, and the editor, the trained assistant-clerk Samuel David Friedländer (Krnov/Jägerndorf, Austria-Hungary, today Czech Republic, 1865 – Death Camp Treblinka, 1942) was sentenced in 1894 to nine months of hard time, and in 1895 was deported from the district of Graz. The small remaining group of “Independent Socialists” made one last attempt with the newspaper “The Free Socialist. Party-less Organ for the mental and economic freedom of the Proletariat” (Der Freie Socialist. Parteiloses Organ für geistige und wirtschaftlische Befreiung des Proletariats). Four issues were made between January and March 1902, all of which were confiscated by the authorities.

While the “Independent Socialists” had lost nearly all influence over the Grazer Labor Movement, a new tendency of anarchist movements gained meaning: a combination of traditional anarchist and so-called life-reform (lebensreform) ideas. A notable representative of this current was Franz Prisching (Hart, Austria-Hungary, today Austria, 1864 – Hart bei Graz, Austria, 1919),[6] whose birth house stood within the present municipal area of Graz, by the parking lot of the apartments on Waltendorfer Hauptstraße 104. In 1897 the day laborer joined the “Independent Socialists.” He had taught himself to read and write later in life and only finished a masons-education at 31. Together with Mathias Trabi, he published a single number of two different journals in 1900 in Graz: in February “New Freedom. International Organ of Anarchists of the German Tongue”[7] (Neue Freiheit. Internationales Organ der Anarchisten deutscher Zunge” and in March “The Free Thought. Organ for the Spreading of Liberal Ideas” (Der freie Gedanke. Organ zur Verbreitung freiheitlicher Ideen). Both were undated and without indication of publishing location. Increasingly distancing himself from the Labor Movement, Prisching developed a thoroughly unique form of nonviolent, christian-antichurch, self- and life-reforming Anarchism. At the center of his worldview stood the biblical command: “thou shalt not kill.” According to Prisching, it should be further developed into “I will not kill.” Prisching, who is often only seen as a follower of the nonviolent Anarchism of Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910), did not assign or subordinate himself to any anarchist movement. He himself did not want to be a “Tolstoyist.” but rather a “Selfist.” And as such he he sought to live out life-reforming ideas in his everyday life like vegetarianism and temperance, animal protection, land reform and settlement movements, and in particular nonviolence. He published many brochures and fliers. On August 8 1903 came the only issue of the journal “The Radical” (Der Radikale), and finally from September 1903 to February 1914 the largely self-produced monthly “The Just Michael” (Der g´rode Michl, Der gerada Michel, trans. Note that this was a parody of “Der detusche Michel,” a German-nationalist personification of the British John Bull at the time), which carried the subtitle “Partyless Monthly” (Parteilose Monatschrift) and from 1904 “Partyless Monthly for All-Around Reform” (Parteilose Monatsschrift für allseitige Reform). Prisching, who lived in Graz until November 1909, had a friend and comrade-in-arms: the lifeguard Franz Sekanek (Bzenec/Bisenz, Austria-Hungary today Czech Republic, 1871, Graz, Austria, 1947). The life-reformer Sekanek, who followed a christian Anarchism in the tradition of Tolstoy, was first a tenant and later proprietor of the Natural Sanitorium for Sunlight-, Air-, Water-, and Diet-cures “Bath Gesundbrunn” (Naturheilanstalt für Sonnenlicht-, Luft-, Wasser- und Diätkuren „Bad Gesundbrunn“) in Graz, Wiener Straße 182. Although, or perhaps because he enlarged the development with a new guesthouse in 1910, the Nature Sanitorium was foreclosed on in 1912.

From January 1913 Sakanek tried to shape the dietary and vegetarian guest and rest-home “Hofjägergut” in Semriach, Windhof 70 into a Tolstoy-Colony. This failed by October of the same year. In 1917 he called to life in St. Peter bei Graz (today part of Graz) the “Tolstoy Society for the Foundation of a Colony.” The society made possible the foundation of the rest-house “Pension Sonnenland” in Attendorfbarg (today part of Hitzendorf), which connected with the “Tolstoy-Settlement Community New Earth” in 1926. Facing financial troubles, Sekanek had to sell this Tolstoy-Settlement in 1930 and moved to Vienna. There he worked as a masseuse, until he returned to Graz during the Second World War.[8]

On August 20, 1910 the “Free Political Society “Peoples Will”” (Freie Politische Verein “Volkswille”) was founded in Graz, and from April 15 1911 to July 15 1914 it published the newspaper “The Peoples Will. Organ of the Styrian Free Socialists.” (Der Volkswille. Organ der freien Sozialisten Steiermarks.) Originally a “Free Socialist” organization, Anarchists took over the group in July 1912 with their spokesperson, the electrician Johann Hermentin (Lassing [zu Gösting an der Ybbs], Austria-Hungary, today Austria 1887 – Vienna, Austria, 1965) and used the newspaper to forward a combination of communist Anarchism and the then relatively new Anarcho-Syndicalism. Additionally there formed the informal group “Federative Masons” (Föderalistische Maurer) around the Masons Assistant Gustav Kern (St. Veit am Vogau [zu St. Veit in der Südsteiermark], Austria-Hungary, today Austria, 1883 – Graz, Austria, 1945), who would later be important for the Graz anarchist movements. There was also a loose group of “Syndicalist Bookprinters of Graz” (Syndikalisischer Buchdrucker von Graz). Certainly it would be an exaggeration to speak of an “Anarchist Movement” in Graz. Nothing clarifies this more than the fact that police in 1912 tallied only a bit more than 50 anarchists in the entire province of Styria.[9]

“The Storms Call” 1919

In Austria, in particular in Vienna, the end of the war brought an outbreak of a wide spectrum of anarchist groups, in particular communist- and individualist- as well as anarcho-syndicalist groups. The situation in Graz was fundamentally different. Franz Sekanek had already left Graz, Franz Prisching fell victim to Pox in 1919, and many of the old guard of the “Independent Socialists” had died. Members of the former “Peoples Will” tried to form a new anarchist movement in Graz. In connection with this, the recently relocated Südbahn-Chief Inspector Nikolaus Nicolits (Vienna, Austria-Hungary, 1872 — ? ) published the newspaper “The Storm’s Call. Socialist Organ for Politics, Intellectual and Cultural Progress, Peoples Economy, and Art” (Der Sturmruf. Sozialistisches Organ für Politik, geistigen und kulturellen Fortschritt, Volkswirtschaft und Kunst) on January 15, 1919. He had been an avid anarchist and free-thought activist in Innsbruck since 1904, and since 1913 in Maribor/Marburg an der Drau (today Slovenia). The paper only lasted a single issue. Due to the Graz Revolt on February 22, 1919, in which 15 demonstrators were killed, Nicholits moved to Vienna following a temporary arrest. He was active there, sometimes as “Nicolits-Hoffman,” in particularly in the “Austrian Occult Grand Lodge” (Österreichischen okkultiscischen Großloge). Meanwhile, the “Free Political Association “People’s Will” became the second mainstay of the newly founded “Federation of Libertarian Socialists” (Bundes herrschaftsloser Sozialisten, B.h.S).

The Graz “Federation of Libertarian Socialists” (B.h.S.)[10]

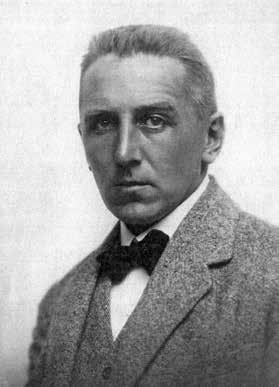

Rudolf Großman (Vienna, Austria 1884 – on the ship „Guiné,“ 1942), better known by his nom de guerre “Pierre Ramus,” stepped into the Graz anarchist vacuum after the First World War.[11]

He had returned to Austria in 1907 after decades in the USA and in England in order to bring a widespread anarchist movement to life. In the course of this he held his first lecture in Graz in August 1908, where the gifted speaker and publicist soon won several followers. In 1918 they joined Pierre Ramus´ “Federation of Libertarian Socialist” (Bund herrschaftsloser Sozialisten, hereafter B.h.S.). Starting from the three “Giant Figures of Human Genius,” Peter Kropotkin (1842–1921), Leo Tolstoy, and Eugen Heinrich Schmitt (1851–1916), Ramus built a thoroughly original form of Anarchism. He extended Anarchism to “the worldview, the understanding, the ethical value-judgements and the social tendencies in people,” elevating it from a mere social teaching to a comprehensive worldview.[12] Its central ethical axiom would be “the principle of individual freedom in social community.”[13] While for him the individual freedom would be secured by the abolition of state and government within society, he saw the “social community” ensured by the introduction of a Communism of informal association without any monopoly. According to Ramus, Anarchy was:

“a free community, within which a federatively run needs-based economy ensures each individual their material needs for existence. Within this free community, there is only the work of the individual regulated by voluntary participation and joint-agreements, such as through the forming of Field-, Occupational-, and Shop-Organizations. Any authoritarian-monopolistic and privileged means of exchange, namely money, is to be abolished as unproductive and harmful; the exchange of products takes place on the basis of mutual needs of all, through the establishment of a needs-based economy.”[14]

Gasthaus “Zum grünen Baum” (“By the Green Tree,”) Mariahilferstraße 56.[15] The prominence of the Graz Groups is also demonstrated by the hosting of the first Austria-wide Congress of the B.h.S. on March 25 and 26, 1922 in Graz, at the Gasthaus “Zu den 3 Hacken,” Schulgasse 13. Delegates from Vienna, Upper- and Lower-Austria, Salzburg, and Styria and 102 guests took part.

The members of the B.h.S. only wanted to present a Social Revolution as a nonviolent change of society, thus the idea of education became the fundamental principle, and written and spoken propaganda the most important forms of action. In this vein they organized Popular Science lectures, but also teaching events like stenography, music, and dance lessons. At the center of educational efforts in Graz stood the retired (since April 1912) high school teacher and former Freiland-follower Dr. phil. Ignaz Fischer (Graz 1861 – Graz 193?), who also published under the pseudonyms “Glüo Fischer” and “Klio.”[16]

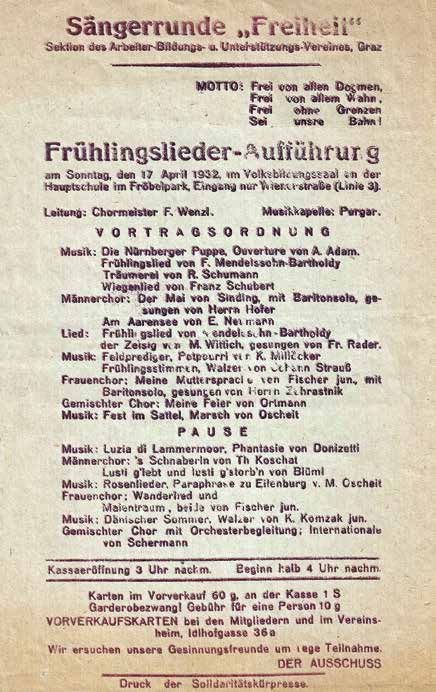

Particularly popular was the Esperanto course, held regularly since October 1922. The initiator of this was the Orchardist Josef Eder (Wetzelsdorf [zu Jagerberg], Austria-Hungary, today Austria 1895 – Graz, Austria 1993), who was also the Austrian contact person for “Tutmondo Ligo de Esperantistoj Senstatanoj” (World League of Non-State Esperantists). In 1928 the Esperanto-Circle “Lumen!” was founded. This was one of the many groupings within the Worker Education and Aid Society, which were seen as Sections. Other groupings included the Women’s Group in May 1922 and the youth-group Francisco Ferrer-League (Francisco Ferrer-Bund) which was already quite active in December 1922. The binding, and without a doubt most active grouping was the Free Singer- and Quartet-music Circle. Founded at the start of 1921, it quickly became inactive before being revived in November and later re-founded as the Singer’s Circle “Freedom”” (Sängerrunde ‚Freiheit‘) for the May 18, 1924, 30th anniversary of the Workers Education and Aid Society.[17]

“Because the song brings emotions into the breast of young and old alike, the mind becomes freer! This is the best moment to win it to our human ideals.”[18] The choir leader was the working musician Josef Ströbl, who also composed the motto of the choir: “Free from all dogmas, free from all delusions / Free with no limits is our path” (Frei von allen Dogmen, fre von allem Wahn / Frei ohne Grenzen sei unsre Bahn). This Singer’s Circle, which had its own orchestra, also had a Women’s choir starting May 1925 and soon afterwards a Children’s choir. It could soon be found at every ceremony of the B.h.S., every commemoration, and even at every funeral of a Graz comrade.

Notably, a Theater Group was recruited primarily from the members of the Singers Circle. It performed, for instance on, May 17 and November 12, 1930 the piece “Buchbinder Schwalbe” (“Bookbinder Schwalbe”) by libretto and writer Robert Bodanzky (1876–1923), himself a member of the B.h.S.[19]

A second cultural center was the 500 volume library of the “Workers Education and Aid Society,” which was first housed in the Society’s hall and later in its own home. Next to anarchist and socialist classics could be found above all popular scientific works. The successful creation of a Reading Circle in May 1926 not only activated the open-twice-weekly Library, but also prepared the agitational activities of several Graz Anarchists. Another step towards propagandized independence came in October 1926, when the gray eminence of the Graz anarchists, the master tailor Mathias Pestiček (Spodnja Velka [zu Šentilj] /Unterwölling, Austria-Hungary, today Czech Republic 1864 – Graz 1943), bought a printing machine together with four comrades: the so called “Kürpresse”. Because they initially only had five type cases, they could only print small works like flyers. But already by January 1928 they were planning a new edition of the August Krčals 1893 broschure. Instead, a speech from Pierre Ramus was the “Kürpresse B.h.S. Verlags” first and only brochure of the series “Free Society Library” (Bibliothek “Freie Gesellschaft”).[20] At the same time they published the first and also last number of the journal “Free Society. Anarcho-Communist Monthly” (Freie Gesellschaft. Anarcho-Kommunistische Monatsschrift,) which sought to fight “against war and militarism; against capital and wage slavery; for a free life on a free Earth.”[21] The beginning of 1927 witnessed a decisive step forward when the Graz Anarchists collectively purchased a garden with a barn as a “free-communist acquisition.” It was renovated by their own efforts and opened on April 5 as the home of the B.h.S. in Graz. There was finally a reliable space. They no longer had to rely on the energy-draining fights with Social Democrats and Communists for locations. The first public speaking courses began on October 18, 1927 under the leadership of Locomotive Heater Heinrich Eckhardt (Linz, Austria-Hungary, 1900 – Graz, 1933) at this new home on Idlhofgasse 36a. Anarchists would be trained as effective public agitators. At public gatherings, the speakers bill was usually carried by the Mason’s assistant Gustav Kern, the cutler Josef Kriegler (Bad Radkersburg/Radkersburg, Austria-Hungary, today Austria, 1876 – Graz, Austria, 1939), the master baker Karl Labritz (natural born Gimpl, Graz, 1889 – Graz 1983), and the locksmith Max Selenko (Graz 1900 – Graz 1984).

Bund der Kriegsdienstgegner, Graz Branch of War Resisters International

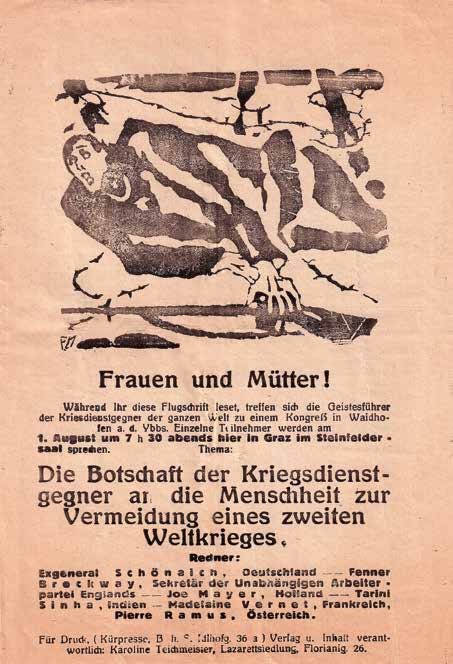

The Graz B.h.S. joined with the “League of War Service Resisters” (Bund der Kriegsdienstgegner), a local organization of “War Resisters International” founded in March 1923. Founder and chair was Othmar (1899–1919: Edler von) Zawodsky (Kuřim/Gurein, Austria-Hungary, today Czech Republic, 1884 – around 1944). Son of a Lieutenant Field Marshall, Zadowsky initially followed the military path but gave up as a lieutenant in the artillery. He studied law in 1904 in Graz. After earning a Doctorate of Law he did a practicum at the Graz Regional Court, and later at the Regional Court of Appeals. He was called up at the beginning of the First World War and commissioned as a First Lieutenant in November 1914. After his war experiences and time as a prisoner of war in Italy in 1918 and 1919, he became an engaged pacifist. He studied chemistry at the University of Graz, where he earned a P.h.D. Afterwards he worked as a chemist at the Physical-Chemistry Laboratory of the Institute of Chemistry the University of Graz. From December 1925 until being banned in 1939 he was an attorney in Graz based at Gartengasse 26. He was followed as the chair of the League of War Service Resistors in 1928 by Alois Zahrastnik (Graz, 1897 – Graz, 1969), Mastor Decorator at Idlhofgasse 36. The Federation published three editions of a newsletter (Mitteilungen des Bundes der Kriegsdienstgegner, Zweig Graz der Kriegsdienstgegner-Internationale) between February 15, 1925 and January 1, 1926. Othmar Zadowsky signed for them. Together with the B.h.S., the Federation organized a gathering in the Steinfelder Hall on July 30, 1923 under the motto “War: Never Again” (Nie wieder Krieg).

Afterwards, anti-war demonstrations were held regularly at the Thalerhof Cemetery of the Murdered POWs, War Resisters, and Deserters on the anniversary of the beginning of the World War. On the side of the Graz B.h.S. an important role was played by the industrial educator Emilie Salzmann (Split/Spalato, Austria-Hungary, today Croatia, 1885 – Vienna, around 1960), better known by her nom de guerre “Emilie Suttner.”

The League of War Service Resistors also maintained close associations with the April 1922 Local-Group Graz of the International Women’s League for Peace and Freedom in Austria (Ortsgruppe Graz der Internationalen Frauenliga für Frieden und Freiheit in Oesterreich), which was only officially dissolved in September, 1936. Furthermore, there were contacts with the also informally-organized Graz group of the “International Association for Self-Disarmament” (Internationalen Verbands für Selbstabrüstung), started in February 1924.

The (free/new) Republicans

The first issue of the newspaper “The Republican. Party-Organ of the Free Republicans of German-Austria” (Der Republikaner. Partei-Organ der Freien Republikaner Deutschösterreichs) was released on January 26, 1919, and shortly afterwards renamed to simply “The Free Republican” (Der freie Republikaner).[22] It was published and financed by Franz Vasold (Liezen, Austria-Hungary, Today Austria 1870 – Murau, Austria, 1955), a merchant and innkeeper who had been a candidate for the Christian Social party in the 1909 provincial elections. Since 1919 he was a member and financial supporter of the B.h.S. along with his wife, Anna Maria Vasold, born von Lehotzky (Murau, Austria-Hungary, today Austria, 1878 – Murau, Austria, 1957). It was Vasold who brought in another member of the B.h.S., the worker and trained shoemaker Adalbert Hirmke (Leoben, Austria-Hungary, today Austria, 1900 – Vienna, Austria, 1981), who later moved to Vienna and founded a well known Grave Speaker’s School. On October 1, 1924 he was made the manager of the newspaper. Vasold had to liquidate it on May 30, 1925 due to financial improprieties, and Hirmke was sentenced to eight months in prison in August 1926 due to embezzlement. After this scandal, the erstwhile editor Franz Scheucher, (Mühlthal, Austria-Hungary, now part of Leoben, Austria 1883 – Graz 1958) took over the paper. The journalist and writer, who also went by the pseudonym “Klaus Haim,” was the central personality of “The Republican.” Since 1925 it was published under the title “The New Republican. Weekly for Domestic Culture and Peoples Enlightenment” (Der neue Republikaner. Wochenschrift für Innenkultur und Volksaufklärung). It defined itself as “independent, radically free, free-socialist, and without party loyalties.” It changed the subtitle several times, and from 1929 understood itself as “Austria’s non-party battle-sheet for all working peoples.” The edition from December 26, 1931 showed even more connections to anarchism, and was officially published by the “Cultural Working Group,” to which Herbert Müller-Guttenbrunn had belonged until 1926. The paper was also temporarily published in Vienna, from the writer and anarchist Rudolf Geist (Úvaly [zu Valtice] /Garschönthal, Austria-Hungary, today Czech Republic, 1900 – Vienna, Austria 1957). This stemmed from a July 1928 attempt by the working group of “The Republican” to build a platform for Socialists, Communists, Anarcho-Communists, Anarchists, and Syndicalists, but after its failure Geist sent the paper back. Neither the paper nor the organization can be seen as primarily anarchist. This melting pot of anticapitalists and politically homeless Socialists and Communists simply offered Anarchists a temporary domain for propaganda. For this, the not particularly sociable editor Franz Scheucher was at least partly responsible. He earned credit for work in Life Reform in Styria, but was overall a political novice.

Herbert Müller-Guttenbrunn

Austrias most original anarchist, the trained lawyer and writer Herber Müller-Guttenbrunn (Vienna, Austria-Hungary, today Austria, 1887- Klosterneuburg, Austria, 1945), lived in Graz between 1923 and 1929. He also used the pseudonym “Herbert Luckhaup”.[23]

In 1923 he purchased land in Thonheben (now part of Semriach) near Graz, and ran an organic, animalless farm. The farm also had a bakery, a mill, and a sawmill. Here, the “amateur anarchist” (as he characterized himself) tried to realize his goal of economic autonomy through agricultural self-sufficiency. He also published one of the most interesting and intelligent anarchist organs in Austria: “The Fog Horn” (Das Nebelhorn). This largely self-published journal had the goal: “The murder of idiocy, that is to say Authority, which is identical.”[24] His opposition to authority also extended to real or imagined authorities within the Anarchist movement, particularly Pierre Ramus, who he derided using the pen name “Peter Zapfel.” He accused Ramus of an antipathy:

“confined not only to the bourgeois papers, but also the domain of the Austrian libertarian movement, where our ‘Fog Horn’ has long suspected that the anarchist rulers of the revolutionary printed word hold to an Anarchism which is so exaggerated that it doesn’t think of submitting to the rule of business.”[25]

Herbert Müller-Guttenbrunn relocated to Klosterneuburg in September, 1929, where he continued not only his agricultural project but also his attacks on Pierre Ramus. On April 10, 1945 he was mistaken for a National Socialist by Russian soldiers and shot.[26]

One of the Herbert Müller-Guttenbrunns few coworkers was Johannes Wohlfahrt (Graz. 1900 – Graz. 1975), whose anarchistic “Proletarian Cycle” of twelve woodblock carvings was appeared in “The Fog Horn” in 1929.[27] But in Autumn 1929, shortly after Herbert Müller-Guttenbrunn left Graz, Johannes Wohlfart moved to Germany.

In this context there are also two notable artists, who at least for a time belonged to the B.h.S. The painter, graphic designer, sculptor, and writer Carl Josef Habiger (Vienna, Austria-Hungary, today Austria, 1886 – Graz, 1959), better known by his art name “Michael Zwoelfboth” as well as “Johann Zwoelfboth”,[28] illustrated many anarchist publications, as well as publications of the B.h.S. Habiger, who moved to Graz during the First World War, founded and led the “Workers Course for Peoples Graphics” (Arbeiterkurs für Volksgraphik) in October 1922. Later he became connected with the Social Democrats and gained local attention, primarily as a Bohemien. The other was the university gardener Alexander Stern (Weidlig (now Klosterneuburg), Austria-Hungary, today Austria, 1894 – Graz. Austria, 1970), who was later known as a photographer and inventor. He was close with the Graz B.h.S. and worked on “The Republican.” His anti-war work “The Crucified” (Die Gekreuzigten) was first performed on August 1, 1927 in Graz under the direction of Karl Drews (Trieste/Triest, Austria-Hungary, today Italy – Vienna, Nazi Germany, 1942), and published by the B.h.S. “Knowledge and Liberation.”[29] This pioneer of the political photo-montage also later shifted towards Social Democracy.

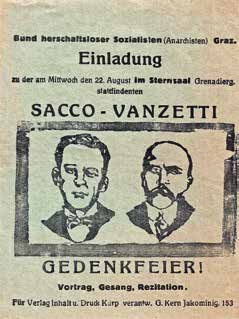

The Bartošek/Bartoschek Brothers

The Bartošek Brothers, sons of a senior tax official who moved from Moravia in 1920, were a sworn community within the Graz B.h.S. They soon brought the club “Free Thinkers” (Freie Denker), founded by Anarchists on May 2, 1909, into the domain of their “Bartošek Brothers Working Group,” conceived as an anarchist counterpart to the social-democrat dominated “Freethought Clubs.” In the wake of the general upswing in the anarchist movement following the judicial murder of Sacco and Vanzetti, the group even put out a short-lived paper.[30]

Alongside the struggle against the institutional church and religion, the Bartošek Brothers were active in another: the vasectomy, the reversible sterilization of men. The oldest of the five sons, „Hans“ Johann Bartošek (Ghijasa de Sus, now Comuna Alțâna, Austria-Hungary, today Romania, 1897 – Graz 1970) studied medicine and was an assistant of Prof. Dr. Hermann Schmerz (Brno/Brünn, Austria-Hungary, today Czech Republic, 1881 – Graz, Nazi Germany, 1941), who had performed the first vasectomies in Graz. After his boss was criminally convicted in 1929, Johann Bartošek, who also published under the pseudonym “Prometheus,” continued carrying out operations in secret. After his vasectomies were publicized, he fled to Spain in September 1932, which is why he was not a part of the below-discussed Graz Vasectomy Trial. He returned to Graz later, where he opened a private medical practice. His brother, Klemens Bartošek (Radlje ob Dravi/Mahrenberg, Austria-Hungary, today Slovenia, 1904 – Graz, Austria, 1960), who later went by “Klements Bartoschek,” also studied medicine became a junior doctor at the Graz State Hospital. He took part in the secret vasectomies and was charged in the Graz Vasectomy Trial, but was acquitted. The driving force was Norbert Bartošek (Radlje ob Dravi/Mahrenberg 1902– Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1959), who occasionally passed himself off falsely as a doctor. He was supposed to be tried in the Graz Vasektomy Trial, but had fled to Spain in 1932. In Madrid, he was taken from the Administration Office of the paper of the anarcho-syndicalist “Confederación Nacional del Trabajo” (National Confederation of Workers, CNT) and temporarily detained in December, 1933. He then went to France, where he performed vasectomies first for several months in Lyon, then in Bordeaux. When this was broken up, he fled to Brussels in April, 1935, where he went by the name “Norbert Bartozek.” He was, however, extradited to France in December, where he was sentenced to three years prison and ten years residency-ban as the lead surgeon in the famous trial of the “Sterilization of Bordeaux.” The sentence was reduced to a year on July 1, 1936. After his release, he settled in La Faut-sur-Mer, where he continued to perform operations underground.[31] In May, 1938 he fled to Geneva, Switzerland, but in 1940 moved to Paris where he was arrested in 1941. During these years he began to dabble in Astrology. When he returned to Graz after the Second World War, he published a number of astrological works once again under the name “Norbert Bartoschek.”[32] At the beginning of the 1950s he emigrated to Argentina, where he operated an import business with South American goods, but went bankrupt during the coup against Perónism in 1955.

The End of the Federation of Libertarian Socialists (B.h.S.): The Sterilization Trial

Differences emerged openly between the Graz Anarchists of the B.h.S. and their spokesperson Pierre Ramus in 1931. An ever-growing group accused Ramus of fostering a cult of personality, and challenged his continuing claims to leadership within the B.h.S. The conflict escalated when Ramus, who had long supported a variety of birth control methods, began using the B.h.S. for wide propaganda campaign promoting the vasectomy.[33] He proposed that he receive compensation of 175–200 schillings per propaganda engagement. For the Graz anarchists, this sum was much to high. They stipulated only 75 Schillings for B.h.S. members and 80 for others. Even the requests of his important Graz comrade Gustav Kern “not to be so stubborn,” and his warnings that “monstrous misunderstandings will be caused by this mischief” were ignored by Ramus.[34] On August 28, 1932, during this critical atmosphere for the anarchist movement, police entered the Haus Griesplatz 23 and discovered what even the social democratic press scandalized as a “Secret Clinic for the Sterilization of Men.”[35]

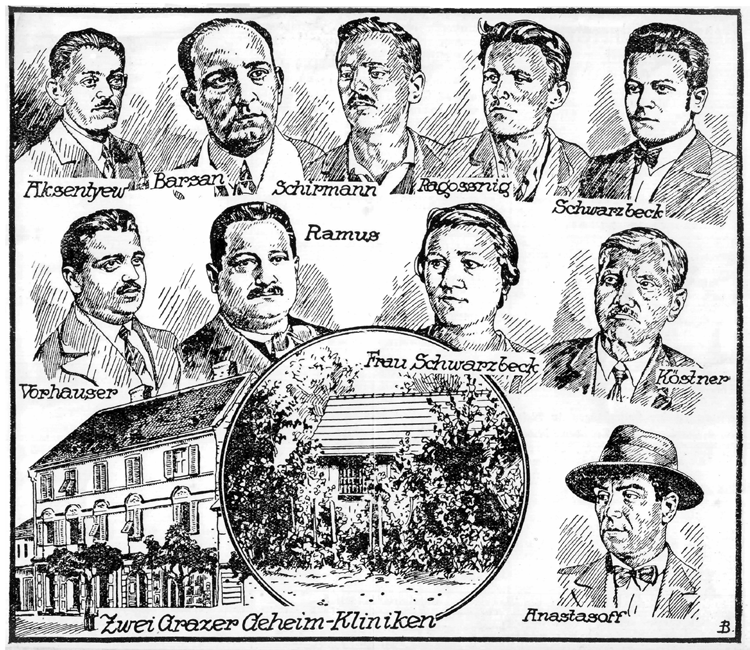

It was soon revealed that under the name of the “Graz Chess Club,” a network of B.h.S. vasectomy clinics had been organized in apartments in Vienna, Wiener Neustadt, Linz, as well as the organizational center of Graz. While the main organizer, the Graz masons apprentice Johann Vorhauser (Graz 1902 – Graz 1976), and his important Graz colleagues Johann and Norbert Bartošek and the technician Hubert Schwarzbeck (Maribor/Marburg 1906 – Graz 1989), managed to flee to Spain, there were countless police searches and arrests around the city, including of Pierre Ramus. After almost a years preparation, the so-called “Sterilization Trial” took place from June 6–30, 1933 in front of the Aldermans Senate of the Provincial Court of Graz. 21 people were charged primarily with “grevious bodily harm” (schweren körperlichen Beschädigung). To general surprise, all defendants were acquitted on July 4, because the defendants were found to have lacked the intent to cause serious injury.

The First State Prosecutor immediately launched an appeal, which led to a new handling of the case on May 7 and 8, 1934, this time in the Supreme Court in Vienna, at which only five of the defendants had to appear. This time, Pierre Ramus was sentenced to fourteen months of hard time, strengthened by a fasting and a hard labor day every month. Another defendant was placed on strict arrest for two months, and the rest to hard time between two and ten months, for a total of eight years and two months of jail sentences. The justification for the sentencing stated: “The defendants could not prove that anyone can do what their body what they want, because the individual cannot freely damage their bodily integrity when there is a public interest.”[36] This was the final nail in the coffin of the B.h.S. The Graz 1933 party celebrating the acquittals in the First Vasectomy Trial couldnt hide this, and neither could the last public function of the Graz Anarchists: the June 4–5, 1933 festival celebrating the 40th anniversary of the “Workers Education and Aid Society.”

Reorientation and Reorganizations Attempts

The Graz B.h.S. was still the premier anarchist movement in the Syrian capitol. But the group of unquestioning followers of Pierre Ramus became ever smaller, while those who criticized his personality cult and leadership grew all the larger. Within that came another, timelier conflict- and discussion-point: Ramus’ fundamental rejection of violence. A clarification of this question within the B.h.S. could at least no longer take place in public. Between the coup of the Christian Socials in March 1933 via the dissolution of Parliament and the bloody defeat of the Social Democratic uprising-attempt in February 1934, a “Ständesstaat” (State of Estates, the Austrofascist Corporate State) dictatorship had established itself in Austria. On May 20, 1934, the decades-long public discussion platform of the Graz Anarchists, the “Workers Education and Aid Society,” at the time having 500 members according to the police, was banned. The remaining activists fought over “the legacy of the imprisoned Ramus,” as the laborer Josef Teichmeister (Judenburg, Austria-Hungary, later Austria, 1902 – Graz, 1993) later characterized things.[37] On the one hand, there was the question of whether or not to continue performing vasectomies. Primarily, though, discussions centered around whether to try continue on the path of public propaganda (Bird Faction, Fraktion der Vögel), or whether they should immediately prepare for underground work (Fish Faction, Fraktion der Fische).

In fact, a small group of former members of the B.h.S. continued performing vasectomies from around February, 1935 in Graz and in Andritz and Wetzelsdorf, today part of the city. But this didn’t last long, and on October 8, 1935 a mixed court convicted all five accused Anarchists. As the surgeon, Cornel Bârsan (Brașov/Brassó, Austria-Hungary, today Romania 1899 – ?) was sentenced to a year imprisonment and subsequent expulsion from the province. As his assistant, the locksmiths assistant Franz Schebesta (Graz, 1899 – Kapfenberg, Austria, 1963) was sentenced to four months hard time. For providing apartments and other assistance, the already named locksmith Max Slenko was sentenced to two months imprisonment, the former train official and then laborer Johann Jaindl (Oberandritz, now Graz, 1902 – Graz 1950) to six weeks, and the paper machine operator Stefan Pansy (St. Vinzenz, now Lavamünd, Austria- Hungary, today Austria, 1898 – Graz 1953) to two weeks strict arrest.

Amidst the trials and tribulations of state repression and personal frustrations, Sunday excursions to the Graz surroundings had been an important institution for Graz anarchists since the 1920s. Popular destinations included Hochlantsch and Hohe Rannach in the Graz hills, Plankenwarth (now St. Oswald bei Plankenwarth) and Thalerhof (now Kalsdorf bei Graz).

Not only did they help ensure cohesion during the period of illegality, they also enabled discussion away from police ears. These excursions were the launching pad for the two best known illegal anarchist groups in Austria during the Ständesstaat.

The Underground Groups of Steflitsch and Leeb: “Bread and Freedom” and “Light”[38]

When the so-called Spanish Civil War began in July 1936, it served as a beacon for the Graz Anarchists. But neither impulse nor information came from Johann Vorhauser, or Norbert or Johann Bartošek, who had fled to Spain due to the Vasectomy Trials. Nor did it come from Hubert Schwarzbeck, who fought as a major in the Republican Army, nor from the radiography assistant Goldy Parin-Matthèy (Graz 1911 – Zürich, Switzerland 1997), who had been with the International Brigades under the nom de guerre “Liselot” since June 1937 and who supported the Spanish anarcho-syndicalist movement.[39] It was primarily Anarchists from Bulgaria, mostly doctors and technical students who had fled to Graz from a dictatorship in their own homeland, that awoke the interests of the Graz Anarchists to the events in Spain.

A notable role was played by the technician, editor, and writer Panajot Velikov Čivikov (Ruse, Bulgaria 1904 – Ruse, Bulgaria 1998), who is today counted among the most important Bulgarian anarchists. After his escape, he regularly found shelter in the house of the former B.h.S. activist, the landlady Mitzi Zahrastnik, born Maria Dorner (Graz, Austria-Hungary, 1899 – Graz, Austria, 1992), and her recently divorced husband and chair of the Graz “League of War Service Resistors,” Alois Zahrastnik. It was here that Panajot Čivikov met his later wife, “Sophie” Sofia Paunovič (Graz 1905 – Ruse, Bulgaria 1989) and her sister “Grete” Margaretha Paunovič (Graz 1910 – Graz 1998),[40] who had both been teachers and nursers in Spain and who joined the Graz anarchist scene after their return. Čivikov succeeded in initiating two underground groups of former B.h.S. members, which he provided information about the struggle of Anarchists and Anarcho-Syndicalists in Spain. They first coalesced around the Mason- and Laquerware Assistant “Steffl” Josef Steflitsch (Maribor/Marburg 1907 – ?). The hard core was made up his partner, the cook “Fini” Josefa Schwab (Pongratzen, now Großradl, 1908 – Graz 1980), the installation apprentice Franz Schwab (Graz 1920 – died around 1943), the Bulgarian medicine student Dimitrij Keremedžiev (Jambol, Bulgaria, 1912 – Prag, Czechoslovakia, 1976), and the Bulgarian technical student “Hari” Charalampij Dimitrov-Charalampiev (Kjustendil, Bulgaria, 1915 – ?). The then-jobless bakers assistant Maximilian Koller (Marktl, now Straden, Austria-Hungary, today Austria, 1918 – ?) served as liaison to the other group. The second group organized itself around the Leeb sisters: “Otti” Ottilie Leeb (Graz, 1909 – Graz, 1982) who would be blinded after the Second World War and would be married as Binder, and the trained tailor and then-laborer “Mitzi” Maria Leeb (Graz, 1910 – Graz, 1993), later married as Rader. Other members of the group included the trained locksmith and then-chauffer of the city government Alois Rader (Graz, 1897 — ?), Maria Raders partner, the locksmith’s assistant “Sepp” Josef Teichmeister (Judenburg, 1902 – Graz, 1993) as well as the previously discussed landlady Maria Theresia Zahrastnik. Active in the sphere of both groups was the cleaner “Anny” Anna Schwab (born Piskar, Aalfang, now Amaliendorf-Aalfang, Austria-Hungary, today Austria, 1898 – Graz, 1976), mother of the above-mentioned Franz Schwab. Both groups existed within a large field of sympathizers, primarily former members of the B.h.S.

After the Steflitsch group illegally printed four fliers about the events in Spain from March to July 1937, they began mimeographing an underground newspaper, usually with a circulation of 100–150. It was the only Anarchist periodical in Austria during the Ständesstaat dictatorship. “Notices from the Austrian Anarcho-Communist Union(s) F. A. Oe.” (Mitteilungen der anarcho-kommunistische[n] Vereinigung Öesterreichs F. A. Oe.) in August 1937 was followed in September by “Bread and Freedom. Organ of the Anarchist Federation of the German Language-area” (Brot und Freiheit. Organ der anarchistischen Föderation Deutscher Sprachkreis) and a third volume of the same title in October. The Leeb Group put out two issues of the mimeographed journal “Light” (“Licht”) in September and October, 1937. This journal was delivered at night by briefcase and also spread around public squares. It dealt almost exclusively with the struggle of the Anarchists and Anarcho-Syndicalists in Spain. Only rarely was the situation in Austria referenced, and only once was there a call for the building of Anarchist groups to bring about a social revolution in Austria. On November 22, 1937, following a neighbors denunciation, nine people were arrested. A number of house searches and further arrests took place in Graz and Leoben through December 7. While the “Bread and Freedom” group around Josef Steflitsch was almost totally uncovered, the “Light” group around Ottilie and Maria Leeb survived. The trial happened on February 2, 1938, in so-called accelerated proceedings in front of the Provincial and Circuit Court and with the public excluded. The seven were accused of seeking a “violent change in the form of government and the carrying out of Indignities and a Civil War.” This is certainly a notable bit of cynicism, as the ruling political system had itself come to power through a putsch and a civil war. The defense of the accused was handled by Othmar Zawodsky, likely his last act as an attorney before his looming ban by the Nazis. Josef Steflitsch was sentenced to two years hard time with quarterly labor, with his partner Josefa Kapelari also receiving two years and, as a Yugoslavian citizen, deportation. The laborer “Pierre” Peter Fabian (Pyhrn, now Liezen, Austria-Hungary, now Austria 1904 – Leoben, Austria 1940), the baker’s assistant Augustin Dobay (Trofaiach 1885 – Knittelfeld 1967), and Maximillian Koller all received a years prison. Only the two Bulgarian students Dimitrij Keremedžiev and Charalampij Dimitrov-Charalampiev were let off due to lack of evidence, but they were then deported from Austria. A few weeks after the trial, the Ständesstaat Dictatorship was destroyed by the National Socialists. The planned legal proceedings against the young Franz Schwab, also due to high treason, did not take place. The imprisoned Graz Anarchists were amnestied as political prisoners after three months in March, 1938. But this was no release to freedom, but rather to a social and political prison of a better and more terribly organized fascism.

But several members of the two underground groups would go on to be forces behind the revival of the anarchist movement in Graz after the Second World War: in particular Ottlie Leeb-Binder, Maria Leeb-Rader, and Josef Teichmeister, with the 1947–1949 journal “The Free Generation” as well as “Neue Generation” (Die Freie Generation and Neue Generation), and Anna Schwab, who had married Knödl and published pacifist poems.[41] Another member of the former B.h.S., the locksmith and lathe operator Ferdinand Groß (Vienna, 1908 – Graz, 1998), who spend 1939–1945 in a concentration camp, propagated an anarchism in the tradition of Pierre Ramus. Among others, he published a pamphlet series “Information on the Independent Partyless Antimilitarists and Pacifists” (Informationen der unabhängigen parteilosen Antimilitaristen und Pazifisten) from 1959 to 1962, “Information on the Libertarian Socialists and Antimilitarists” from 1964 to 1968, “Information on the Libertarian Socialists – Anarchists” in 1974, and from 1975 to 1997 the quarterly “Liberation. Organ of Libertarian Socialism for Social and Intellectual New-culture in the sense of Peace, Nonviolence and Invididual Self-Determination; for Free People and those who want to be.”[42]

Even these reorganization attempts after the Second World War show the meaning of the Styrian capitol for Anarchism in Austria. Graz was not only the birth-city of the first true Austrian Anarchist movement in 1887. Between the World Wars it was, in relation to its population, the center of the anarchist movements in Austria. From the labor-movement derived socialist anarchism of Johann Rismann and August Krčal, to the Life Reforming anarchism of Franz Prisching, to the christian anarchism of Franz Sekanek, to the radical nonviolent anarchism of the “Federation of Libertarian Socialists,” to the culture-critical anarchism of Herbert Müller-Guttenbrunn, just to name a few, Graz is a wonderful example of the diversity of anarchist ideas, movements, and personalities.

[1] Bertrand RUSSELL: Wege zur Freiheit. Sozialismus, Anarchismus, Syndikalismus (= edition suhrkamp, 447), Frankfurt am Main 1971, 41. In English as Bertrand Russell, Proposed Roads to Freedom: Socialism, Anarchism, and Syndicalism, 1918.

[2] Peter LÖSCHE: Anarchismus (= Erträge der Forschung, 66), Darmstadt 1977, 18. Zu einer anarchistischen Perspektive see also Horst STOWASSER: Anarchie! Idee – Geschichte – Perspektive, Hamburg 2007.

[3] See Reinhard MÜLLER: Der aufrechte Gang am Rande der Geschichte. Anarchisten in der Steiermark zwischen 1918 und 1934, in: R[obert] HINTEREGGER, K[arl] MÜLLER, E[duard] STAUDINGER (Hgg.): Auf dem Weg in die Freiheit (= Anstöße zu einer steirischen Zeitgeschichte), Graz 1984, 163–195, vor allem 164–167.

[4] See Reinhard MÜLLER: Manifest der Unabhängigen Socialisten (1892). Das erste anarchistische Manifest in Österreich (= Edition Wilde Mischung, 22), Wien 2002.

[5] The subject of this high-treason trial was the self-published broshure, the first Anarchist book-publication in Austria and, until today, the most important representation of the Austrian worker’s movement from an Anarchist perspective. See August KRČAL: Zur Geschichte der Arbeiter-Bewegung Oesterreichs. 1867–1892. Eine kritische Darlegung, Graz 1893.

[6] See Reinhard MÜLLER: Franz Prisching 1864–1919. G’roder Michl, Pazifist und Selberaner, Nettersheim/Hart bei Graz 2006.

[7] Translator’s Note: It was a common practice for some German-speaking Anarchists in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and elsewhere to refer to their broader community as “German Speaking” or “German Tongue” Anarchists rather than simply “German Anarchists” as a means of highlighting a sense of transcending national borders while declaring a difference from the dominant culture’s German Nationalism.

[8] In 1946 Franz Sekanek founded and led the “God’s World Federation of Deed-Christians for Social Renewal on the Lines of Tolstoy” („Weltbund Gottes der Tatchristen für gesellschaftliche Erneuerung im Sinne Tolstoi“); See his programmatic, anonymously published works: Was wollen die Tatchristen? Graz [1946], Die Bergpredigt, Graz [1946].

[9] See [POLIZEIDIREKTION WIEN] : Sozialdemokratische und anarchistische Bewegung im Jahre 1912, Wien 1913, 63.

[10] See MÜLLER: Der aufrechte Gang, 167–182 und 184–186.

[11] He died in exile on the trip from the Protectorate of French Morocco (today Morocco) to Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llaye, Mexico. For Pierre Ramus see Gerfried BRANDSTETTER: Rudolf Großmann („Pierre Ramus“). Ein österreichischer Anarchist (1882–1942), in: Gerhard BOTZ, Hans HAUTMANN, Helmut KONRAD, Josef WEIDENHOLZER (Hgg.): Bewegung und Klasse. Studien zur österreichischen Arbeitergeschichte. 10 Jahre Ludwig Boltzmann Institut für Geschichte der Arbeiterbewegung, Wien/München/Zürich 1978, 89–118; Gerda FELLAY, Reinhard MÜLLER (Hgg.): Hommage à la non-violance. Ein grosser freiheitlicher Erzieher: Pierre Ramus (1882–1942) (= La Collection „Les nouveaux humanistes“/Die Reihe „Die Neuen Humanisten“, 4), Lausanne 2000, und die Website der Wiener „Pierre Ramus Gesellschaft“: www.ramus.at / (abgerufen am 15.5.2018) as well as the digitized Pierre Ramus Papers at the Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis, Amsterdam, available online under: hdl.handle.net/10622/ARCH01162.

[12] See [Pierre RAMUS (d. i. Rudolf Großmann)] : Was ist und will der Bund herrschaftsloser Sozialisten? Die auf der Bundestagung am 25. und 26. März 1922 angenommenen Leitsätze und Richtlinien unserer Anschauung und Betätigung, Wien/Klosterneuburg [1922], 17. Vgl. auch Beatrix MÜLLER-KAMPEL, Reinhard MÜLLER: Anarchistische Katholizismuskritik zu Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts. Franz Prisching, Pierre Ramus, Herbert Müller-Guttenbrunn, in: Carsten JAKOBI, Bernhard SPIES, Andrea JÄGER (Hgg.): Religionskritik in Literatur und Philosophie nach der Aufklärung (= Massenphänomene, 2), Halle (Saale) 2007, 107–120.

[13] See RAMUS: Was ist und will der B. h. S., 5.

[14] Ibid. 6–7.

[15] Translator’s Note: An Austrian “Gasthaus” is an old-style of inn or tavern, usually serving food and alcohol as well as having rooms for rent.

[16] See Ign[az] FISCHER: Das erste Jahr der natürlichen Schule. Eine Studie als praktischer Beitrag zu Ewald Haufe’s natürlicher Erziehung (= Stein’s Handbücher für Lehrer, 25), Potsdam 1907; und Glüo FISCHER: Aus meiner Weltanschauung. Einleitung zu dem „Werdeschauwirk“. „Natürliche Erziehung“ im Sinne Dr. Ewald Haufes (= Bücherreihe: Die natürliche Erziehung, 1), Brünn [1930].

[17] A part of the Note Inventory is in the collection of Reinhard Müller, Graz.

[18] G[ustav] K[ERN] : Freie Sänger, in: Erkenntnis und Befreiung, 6, 2, Wien 13. Jänner 1924, 4

[19] See Buchbinder Schwalbe. Komödie in drei Akten, in: Robert Bodanzky <Danton>: Revolutionäre Dichtungen und politische Essays, Wien/Klosterneuburg 1925, 169–247.

[20] See Pierre RAMUS: Die Menschheitskrise und ihre Ueberwindung durch den Anarchismus. Auszügliche Wiedergabe eines Vortrages von Pierre Ramus, gehalten am 15. Mai 1926 in Graz (= Bibliothek „Freie Gesellschaft“, 1), Graz 1929.

[21] [Oskar LEUTNER] : Die Gesellschaftskrise und unsere Aufgaben dagegen, in: Freie Gesellschaft. Anarcho-Kommunistische Monatsschrift, 1, 1, Graz April 1929, 3.

[22] Translator’s Note: After the collapse of the Habsburg Austro-Hungarian Empire following the First World War, German-speaking social democratic, german nationalist, and catholic conservative parties united to form the “Republic of German-Austria,” in part recognizing their mutual ambitions to join with the neighboring German (Weimar) Republic. “German” was later dropped from the name.

[23] See Herbert MÜLLER-GUTTENBRUNN: Alphabet des anarchistischen Amateurs. Hg. von Beatrix MÜLLER-KAMPEL (= Batterien, 78), Berlin 2007; Beatrix MÜLLER-KAMPEL, Reinhard MÜLLER: Müller-Guttenbrunn, Herbert, in: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon, 32. Bd., Nordhausen 2011, 983–990.

[24] [Herbert MÜLLER-GUTTENBRUNN] : Das Nebelhorn, in: Das Nebelhorn, 1, 1, Graz 1. Jänner 1929, 3.

[25] [Herbert MÜLLER-GUTTENBRUNN] : Der schweigsame „Anarchist“, in: Das Nebelhorn, 1, 22, Graz 15. November 1927, 16.

[26] The only other publication of the publisher “The Fog Horn” (Das Nebelhorn) was a collection of poems by his lover during his Graz days under the pseudonym “Freya BAUMGART”: Amo, ergo sum! Wien 1930.

[27] See Johannes WOHLFART: Ein Mensch und ein Jahr, in: Das Nebelhorn, 4, 57, Graz 1. Mai 1929, 8–10. Noch in Graz entstand Johannes WOHLFART: Proletarierleben. 12 Holzschnitte, Pfullingen bei Württemberg [1930]. Vgl. auch Reinhard MÜLLER: Die Episode mit dem anarchistischen Amateur – Johannes Wohlfart und Herbert Müller-Guttenbrunn, in: Günther HOLLER-SCHUSTER (Hg.): Johannes Wohlfart. Kühle Moderne unter Einfluss starker Hitze, Graz 2008, 22–34.

[28] See ZWOELFBOTH: Schwert gegen Seele (= Das Neue Gedicht, [1] ), Wien 1918 [recte 1917], und ders.: Sechs Zeichnungen für Sichere und Satte (Postkarten für Kriegsgewinner und andere Begeisterte!), Wien [1919], Mappe mit sechs Grafiken als Postkarten. Er verwendete mit seiner Ehefrau Maria auch das Pseudonym „Maria Karlund“.

[29] See Alex[ander] STERN: Die Gekreuzigten. Revue in 6 Bildern aus den Tagen österreichischer Schlachtfeste, Wien/Klosterneuburg [1928]. Vgl. Günter EISENHUT: Alexander Stern, in: Günter EISENHUT, Peter WEIBEL (Hgg.): Moderne in dunkler Zeit. Widerstand, Verfolgung und Exil steirischer Künstlerinnen und Künstler 1933–1948, Graz 2001, 432–447.

[30] Freie Denker. Organ der freigeistigen Bewegung (Graz), 1. Jg. (August – September 1927), 2 Nummern. Alongside the below-named brother’s also worked the official Oskar (Carl) Bartošek (Murau 1906 – Graz 1975). Two Anarchist immigrants from Italy to the USA, the shoemaker and night watchman Fernando “Nicola Sacco” (1891–1927) and the fish handler Bartolomeo Vanzetti (1888–1927), were found guilty on charges of Robber-Murdery in 1921 in a controversial trial. After many rejected appeals they were executed on August 23, 1927 in Charlestown, Massachussets despite worldwide protests. In 1977, 50 years after their executions, they were posthumously rehabilitated by the Governor of Massachussets.

[31] Here he published one of the most important Anarchist publications on vasectomy; see Norbert BARTOSEK: La Stérilisation Sexuelle. Son importance Eugénique, Médicale, Sociale. Avant-propos de Hem Day [d. i. Marcel Camille Dieu], Bruxelles [1936].

[32] See. Norbert BARTOSCHEK: Die astrologische Praxis. Lehrgang der modernen astrologischen Wissenschaft, 3 Bände, Graz 1946–1947; Nostradamus und seine berühmten Prophezeiungen. Das Leben und Werk des astrologischen Sehers von Salon mit einem Ausblick auf 1947, Graz 1946; Atombombe droht? Graz 1947 (also in Esperanto: Ĉu Atom-bombo minacas? Graz 1947); Astrologische Ephemeriden. 1881–1914, Graz 1947; Astrologische Ephemeriden. 1915–1950, Graz 1947; Ihr Schicksal 1947, Graz 1947; Ihr Schicksal 1948, Graz [1947] ; Die Runengeomantik. Das Ur-Orakel der Menschheit, Innsbruck 1948; Astrologische Ephemeriden. 1951–1970, Innsbruck [1949] (also Memmingen/Bayern [1950] ).

[33] See. [Pierre RAMUS (d. i. Rudolf Großmann)] : Vasektomie, das Zaubermittel der Verjüngung! – Wie verhütet man ungewollte Empfängnis und Schwangerschaft? – Ein tatsächlicher Ratgeber für Alle! Stockholm [1931].

[34] Vgl. Gustav KERN: Briefe an Pierre Ramus. Graz, am 5. Dezember 1931 und am 18. Oktober 1931, here quoting from the indictment, 37 und 33, Akt des Landesgerichtes für Strafsachen Graz im StLA, l5 Vr-2842/1932.

[35] [ANONYM] : Körperverstümmelungen am laufenden Band durch verbummelte bulgarische Studenten, in: Arbeiterwille, 43, 243, Graz 3. September 1932, 3.

[36] Urteil, im Österreichischen Staatsarchiv, Akt des Obersten Gerichtshofes in Wien, 5 Os-1070/1933.

[37] Interview by Reinhard Müller with Josef Teichmeister, Graz, on May 6, 1983

[38] See Reinhard MÜLLER: „Wer pessimistisch in die Zukunft blickt, offenbart seinen schwachen Willen.“ Anarchistischer Kampf während des Austrofaschismus. Graz 1937 (= Institut für Anarchismusforschung, 4), Wien 2016.

[39] See [Reinhard MÜLLER] : Goldy Parin-Matthèy, geborene Elisabeth Charlotte Matthèy-Guenet, verheiratete Parin (Graz 1911 – Zürich 1997), in: ders.: Anarchistinnen aus Österreich. Kalender 2017 der Anarchistischen Bibliothek u. Archiv Wien, Wien [2016], Monat Juni. The wall calendar also had biographies with pictures of other Graz Anarchists: Maria Schwarzbeck, born Wolf (Graz 1905 – Graz 1941), March; Mitzi Zahrastnik, born Maria Dorner (Graz 1899 – Graz 1992), May; Grete Zahrastnik, born Paunovič (Graz 1910 – Graz 1998), July; Otti Binder, born Ottilie Leeb (Graz 1909 – Graz 1982), August; Mitzi Rader, born Maria Leeb (Graz 1910 – Graz 1993), November.

[40] For the later-famous photographer and her role in the resistance against National Socialism see Günter EISENHUT: Grete Zahrastnik (Paunovic), in: Günter EISENHUT, Peter WEIBEL (Hgg.): Moderne in dunkler Zeit. Widerstand, Verfolgung und Exil steirischer Künstlerinnen und Künstler 1933–1948, Graz 2001, 544–549.

[41] A few volumes with partially unpublished texts can be found in the estate of Ferdinand Groß in possession of Reinhard Müller, Graz.

[42] See Reinhard MÜLLER: Ferdinand Groß (Wien 1908 – Graz 1998). Aus dem Leben eines österreichischen Anarchisten und Antimilitaristen, in: friedolins befreiung, 2, Graz Juni 1998, 4–15.